History of Germany

Encyclopedia

The concept of Germany

as a distinct region in central Europe can be traced to Roman commander Julius Caesar

, who referred to the unconquered area east of the Rhine as Germania

, thus distinguishing it from Gaul

(France), which he had conquered. The victory of the Germanic tribes in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

(AD 9) prevented annexation by the Roman Empire

. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, the Franks

conquered the other West Germanic tribes

. When the Frankish Empire was divided among Charlemagne

's heirs in 843, the eastern part became East Francia. In 962, Otto I became the first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

, the medieval German state.

In the High Middle Ages

, the dukes and princes of the empire gained power at the expense of the emperors. Martin Luther

led the Protestant Reformation

against the Catholic Church after 1517, as the northern states became Protestant, while the southern states remained Catholic. They clashed in the Thirty Years' War

(1618–1648), which was ruinous to the twenty million civilians. 1648 marked the effective end of the Holy Roman Empire and the beginning of the modern nation-state system, with Germany divided into numerous independent states, such as Prussia

, Bavaria

and Saxony

.

After the French Revolution

and the Napoleonic Wars

(1803–1815), feudalism fell away and liberalism and nationalism clashed with reaction. The 1848 March Revolution

failed. The Industrial Revolution

modernized the German economy, led to the rapid growth of cities and to the emergence of the Socialist movement

in Germany. Prussia, with its capital Berlin

, grew in power. German universities became world-class centers for science and the humanities, while music and the arts flourished. Unification was achieved with the formation of the German Empire

in 1871 under the leadership of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

. The Reichstag

, an elected parliament, had only a limited role in the imperial government.

By 1900, Germany's economy matched Britain's, allowing colonial expansion

and a naval race. Germany led the Central Powers

in the First World War (1914–1918) against France, Great Britain, Russia and (by 1917) the United States. Defeated and partly occupied, Germany was forced to pay war reparations

by the Treaty of Versailles

and was stripped of its colonies as well as Polish areas and Alsace-Lorraine. The German Revolution of 1918–19 deposed the emperor and the kings, leading to the establishment of the Weimar Republic

, an unstable parliamentary democracy.

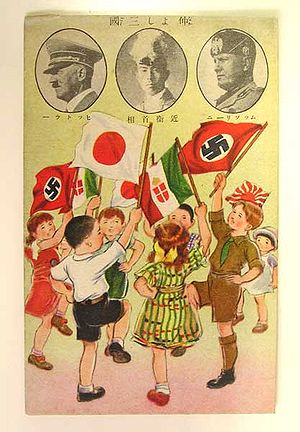

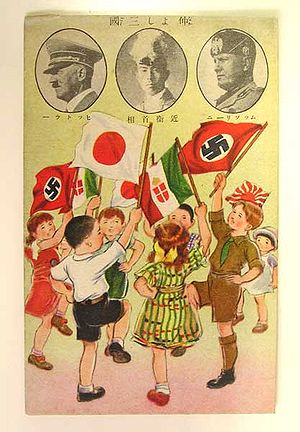

In the early 1930s, the worldwide Great Depression

hit Germany hard, as unemployment soared and people lost confidence in the government. In 1933, the Nazis under Adolf Hitler

came to power and established a totalitarian regime. Political opponents were killed or imprisoned. Nazi Germany

's aggressive foreign policy took control of Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia, and its invasion of Poland initiated the Second World War. After forming a pact with the Soviet Union in 1939, Hitler's blitzkrieg

swept nearly all of Western Europe. In the Holocaust

, six million Jews in Germany and German-occupied areas, as well as five million Poles, Romanies, Slavs, Soviets, and others were systematically killed. In 1941, however, the German invasion of the Soviet Union

failed, and after the United States entered the war, Britain became the base for massive Anglo-American bombings of German cities. Following the Allied invasion of Normandy, the German army was pushed back on all fronts until the final collapse in May 1945.

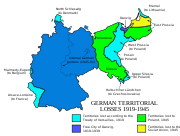

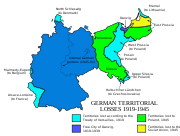

Under occupation by the Allies, German territories were split off, denazification

took place, and the Cold War

resulted in the division of the country into democratic West Germany

and communist East Germany. Millions of ethnic Germans fled from Communist areas into West Germany, which experienced rapid economic expansion

, and became the dominant economy in Western Europe. West Germany was rearmed in the 1950s under the auspices of NATO, but without access to nuclear weapons. The Franco-German friendship became the basis for the political integration of Western Europe in the European Union

. In 1989, the Eastern bloc

collapsed and East Germany was reunited with West Germany in 1990.

.png) The ethnogenesis

The ethnogenesis

of the Germanic tribes

is assumed to have occurred during the Nordic Bronze Age

, or at the latest during the Pre-Roman Iron Age

. From southern Scandinavia and northern Germany, the tribes began expanding south, east and west in the 1st century BC, coming into contact with the Celt

ic tribes of Gaul

as well as Iranian, Baltic

, and Slavic

tribes in Eastern Europe

.

Little is known about early Germanic history, except through their recorded interactions with the Roman Empire

, etymological research and archaeological finds.

In the first years of the 1st century, Roman legions conducted a long campaign in Germania, the area north of the Upper Danube

and east of the Rhine, in an attempt at a further major expansion of the Empire's frontiers, and a shortening of its frontier line. They subdued several Germanic tribes, such as the Cherusci

. The tribes became familiar with Roman tactics of warfare while maintaining their tribal identity. Modern Germany, east of the Rhine remained outside the Roman Empire. By AD 100, the time of Tacitus

' Germania

, Germanic tribes settled along the Rhine and the Danube (the Limes Germanicus

), occupying most of the area of modern Germany; Austria, southern Bavaria

and the western Rhineland

, however, were Roman provinces. The 3rd century saw the emergence of a number of large West Germanic tribes: Alamanni

, Franks

, Chatti

, Saxons

, Frisii

, Sicambri

, and Thuringii

. Around 260, the Germanic peoples broke through the Limes and the Danube frontier into Roman-controlled lands.

Since the 15th century German historians have celebrated

the victory of Arminius

, a chieftain of the Cherusci

, who in 9 AD defeated a Roman army in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

, as the birth of German history.

Seven large German-speaking tribes, the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals

, Burgundians

, Lombards

, Saxons

and the Franks

moved west and took part in the transformation of the peoples

of the old Western Roman Empire

.

(tribal duchies) in Germany was mainly the areas of the old German tribes of the region. These strains were originally the Franks, the Saxons, the Alemanni, the Burgundians

, the Thuringians, and the Rugians

. In the 5th Century the Burgundians moved into Roman territory and would have been in 443 and 458 in the area, then Lower Burgundy

. The area they had occupied in Germany, along with the Saxons

, was occupied by the Franks. The Rugians which Odoacer destroyed in 487 formed a new confederation of Germans in their place, the Bavarians. All of these strains in Germany were finally subdued by the Franks, the Alamanni in 496 and 505, the Thuringia

in 531.

the Franks created an empire under the Merovingian kings and subjugated the other Germanic tribes. Swabia

became a duchy under the Frankish Empire

in 496, following the Battle of Tolbiac

. Already king Chlothar I ruled the greater part of what is now Germany and made expeditions into Saxony

while the Southeast of modern Germany was still under influence of the Ostrogoths. In 531 Saxons and Franks destroyed the Kingdom of Thuringia

. Saxons inhabit the area down to the Unstrut

river.

During the partition of the Frankish empire their German territories were a part of Austrasia

. In 718 the Franconian Mayor of the Palace

Charles Martel

made war against Saxony, because of its help for the Neustria

ns. The Franconian Carloman started in 743 a new war against Saxony, because the Saxons gave aid to Duke Odilo of Bavaria

.

In 751 Pippin III, mayor of the palace

under the Merovingian king, himself assumed the title of king and was anointed by the Church. The Frankish kings now set up as protectors of the pope, Charles the Great launched a decades-long military campaign against their heathen rivals, the Saxons

and the Avars

. The Saxons (by the Saxon Wars

(772–804)) and Avars were eventually overwhelmed and forcibly converted, and their lands were annexed by the Carolingian Empire

.

extended the Carolingian empire into northern Italy and the territories of all west Germanic peoples, including the Saxons and the Bajuwari (Bavarians). In 800, Charlemagne's authority was confirmed by his coronation as emperor in Rome. Imperial strongholds (Kaiserpfalzen) became economic and cultural centres, of which Aachen

was the most famous.

Between 843 and 880, after fighting between Charlemagne's grandchildren, the Carolingian empire was partitioned into several parts in the Treaty of Verdun

(843), the Treaty of Meerssen

(870) and the Treaty of Ribemont

. The German region developed out of the East Frankish kingdom, East Francia. From 919 to 936 the Germanic peoples (Franks

, Saxons

, Swabians and Bavarians) were united under Duke Henry of Saxony, who took the title of king. For the first time, the term Kingdom (Empire) of the Germans ("Regnum Teutonicorum") was applied to a Frankish kingdom, even though Teutonicorum at its founding originally meant something closer to "Realm of the Germanic peoples" or "Germanic Realm" than realm of the Germans.

was crowned at Aachen; his coronation by the Pope at Rome in 962 inaugurated the Holy Roman Empire

, which comprised the German people. Otto strengthened the royal authority by re-asserting the old Carolingian rights over ecclesiastical appointments. Otto wrested from the nobles the powers of appointment of the bishops and abbots, who controlled large land holdings. Additionally, Otto revived the old Carolingian program of appointing missionaries in the border lands. Otto continued to support the celibacy rule for the higher clergy. Thus, the ecclesiastical appointments never became hereditary. By granting land to the abbotts and bishops he appointed, Otto actually made these bishops into "princes of the Empire" (Reichsfürsten). In this way, Otto was able to establish a national church. Outside threats to the kingdom were contained with the decisive defeat of the Magyars of Hungary at the Battle of Lechfeld

in 955. The Slavs between the Elbe

and the Oder

rivers were also subjugated. Otto marched on Rome and drove John XII from the papal throne and for years controlled the election of the pope, setting a firm precedent for imperial control of the papacy for years to come.

During the reign of Conrad II's son, Henry III

(1039 to 1056 ), the Holy Roman Empire supported the Cluniac

reform of the Church - the Peace of God

, the prohibition of simony

(the purchase of clerical offices) and required the celibacy of priests. Imperial authority over the Pope reached its peak. In the Investiture Controversy

which began between Henry IV

and Pope Gregory VII

over appointments to ecclesiastical offices, the emperor was compelled to submit to the Pope at Canossa

in 1077, after having been excommunicated. In 1122 a temporary reconciliation was reached between Henry V

and the Pope with the Concordat of Worms

. The consequences of the investiture dispute were a weakening of the Ottonian church (Reichskirche), and a strengthening of the Imperial secular princes.

The time between 1096 and 1291 was the age of the crusades. Knightly religious orders were established, including the Templars

, the Knights of St John

and the Teutonic Order

.

under the control of nobles and monasteries. A few towns were starting to emerge. From 1100, new towns were founded around imperial strongholds, castles, bishops' palaces and monasteries. The towns began to establish municipal rights and liberties (see German town law

). Several cities such as Cologne

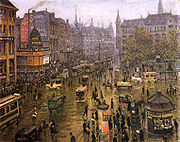

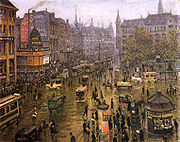

became Imperial Free Cities, which did not depend on princes or bishops, but were immediately subject to the Emperor. The towns were ruled by patricians (merchants carrying on long-distance trade). The craftsmen formed guilds, governed by strict rules, which sought to obtain control of the towns; a few were open to women. Society was divided into sharply demarcated classes: the clergy, physicians, merchants, various guilds of artisans; full citizenship was not available to paupers. Political tensions arose from issues of taxation, public spending, regulation of business, and market supervision, as well as the limits of corporate autonomy.

Cologne's

central location on the Rhine river placed it at the intersection of the major trade routes between east and west and was the basis of Cologne's growth. The economic structures of medieval and early modern Cologne were characterized by the city's status as a major harbor and transport hub upon the Rhine. It was the seat of the archbishops, who ruled the surrounding area and (from 1248 to 1880) built the great Cologne Cathedral

, with sacred relics that made it the destination for many worshippers. By 1288 the city had secured its independence from the archbishop (who relocated to Bonn), and was ruled by its burghers.

, under the leadership of Lübeck

.

It was a business alliance of trading cities and their guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe and flourished from the 1200 to 1500, and continued with lesser importance after that. The chief cities were Cologne

It was a business alliance of trading cities and their guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe and flourished from the 1200 to 1500, and continued with lesser importance after that. The chief cities were Cologne

on the Rhine River, Hamburg

and Bremen

on the North Sea, and Lübeck on the Baltic.

The Hanseatic cities each had its own legal system and a degree of political autonomy.

, such as Bohemia

, Silesia

, Pomerania

, and Livonia

. Beginning in 1226, the Teutonic Knights

began their conquest of Prussia. The native Baltic Prussians were conquered and Christianized by the Knights with much warfare, and numerous German towns were established along the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea.

Henry V

Henry V

(1086–1125), great-grandson of Conrad II became Holy Roman Emperor in 1106 in the midst of a civil war. Hoping to gain complete control over the church inside the Empire, Henry V appointed Adalbert of Saarbruken as archbishop of Mainz in 1111 Adalbert began to assert the powers of the Church against secular authorities, that is, the Emperor. This precipitated the "Crisis of 1111", part of the long-term Investiture Controversy

. In 1137 the magnates turned back to the Hohenstaufen family for a candidate, Conrad III

. Conrad III tried to divest Henry the Proud of his two duchies, leading to war in southern Germany as the Empire divided into two factions. The first faction called themselves the "Welfs" after Henry the Proud's family name which was the ruling dynasty in Bavaria. The other faction was known as the "Waiblings." In this early period, the Welfs generally represented ecclesiastical independence under the papacy plus "particularism" (a strengthening of the local duchies against the central imperial authority). The Waiblings on the other hand stood for control of the Church by a strong central Imperial government.

Between 1152 and 1190, during the reign of Frederick I

(Barbarossa), of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, an accommodation was reached with the rival Guelph party by the grant of the duchy of Bavaria to Henry the Lion

, duke of Saxony

. Austria became a separate duchy by virtue of the Privilegium Minus

in 1156. Barbarossa tried to reassert his control over Italy. In 1177 a final reconciliation was reached between the emperor and the Pope in Venice

.

In 1180 Henry the Lion was outlawed and Bavaria was given to Otto of Wittelsbach

(founder of the Wittelsbach dynasty

which was to rule Bavaria until 1918), while Saxony was divided.

From 1184 to 1186 the Hohenstaufen empire under Barbarossa reached its peak in the Reichsfest (imperial celebrations) held at Mainz

and the marriage of his son Henry

in Milan to the Norman princess Constance of Sicily

. The power of the feudal lords was undermined by the appointment of "ministerials" (unfree servants of the Emperor) as officials. Chivalry and the court life flowered, leading to a development of German culture and literature (see Wolfram von Eschenbach

).

Between 1212 and 1250 Frederick II

established a modern, professionally administered state from his base in Sicily

. He resumed the conquest of Italy, leading to further conflict with the Papacy. In the Empire, extensive sovereign powers were granted to ecclesiastical and secular princes, leading to the rise of independent territorial states. The struggle with the Pope sapped the Empire's strength, as Frederick II was excommunicated three times. After his death, the Hohenstaufen dynasty fell, followed by an interregnum during which there was no Emperor.

The failure of negotiations between Emperor Louis IV

with the papacy led in 1338 to the declaration at Rhense by six electors

to the effect that election by all or the majority of the electors automatically conferred the royal title and rule over the empire, without papal confirmation.

Between 1346 and 1378 Emperor Charles IV

of Luxembourg

, king of Bohemia, sought to restore the imperial authority.

Around 1350 Germany and almost the whole of Europe were ravaged by the Black Death. Jews were persecuted on religious and economic grounds; many fled to Poland.

Around 1350 Germany and almost the whole of Europe were ravaged by the Black Death. Jews were persecuted on religious and economic grounds; many fled to Poland.

The Golden Bull of 1356

stipulated that in future the emperor was to be chosen by four secular electors (the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine

of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony

, and the Margrave of Brandenburg

) and three spiritual electors (the Archbishops of Mainz

, Trier

, and Cologne

).

After the disasters of the 14th century, early-modern European society gradually came into being as a result of economic, religious and political changes. A money economy arose which provoked social discontent among knights and peasants. Gradually, a proto-capitalistic system evolved out of feudalism. The Fugger

family gained prominence through commercial and financial activities and became financiers to both ecclesiastical and secular rulers.

The knightly classes found their monopoly on arms and military skill undermined by the introduction of mercenary armies and foot soldiers. Predatory activity by "robber knights" became common. From 1438 the Habsburg

s, who controlled most of the southeast of the Empire (more or less modern-day Austria and Slovenia

, and Bohemia and Moravia

after the death of King Louis II

in 1526), maintained a constant grip on the position of the Holy Roman Emperor until 1806 (with the exception of the years between 1742 and 1745). This situation, however, gave rise to increased disunity among the Holy Roman Empires territorial rulers and prevented sections of the country from coming together and forming nations in the manner of France and England.

During his reign from 1493 to 1519, Maximilian I

tried to reform the Empire: an Imperial supreme court (Reichskammergericht) was established, imperial taxes were levied, the power of the Imperial Diet

(Reichstag) was increased. The reforms were, however, frustrated by the continued territorial fragmentation of the Empire.

abbess

Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) wrote several influential theological, botanical and medicinal texts, as well as letters, liturgical songs, poems, and arguably the oldest surviving morality play

, while supervising brilliant miniature Illuminations. Ca. 100 years later, Walther von der Vogelweide

(c. 1170-c. 1230) became the most celebrated of the Middle High German

lyric poet

s. Around 1439, Johannes Gutenberg, a citizen of Mainz

, was the first European to use movable type

printing and became the global inventor of the printing press

, thereby starting the Printing Revolution. Gutenberg's inventions and works (e.g. the Gutenberg Bible

) would play key roles for the development of the Reformation

and the Scientific Revolution

. Around the transition from the 15th to the 16th century, Albrecht Dürer

from Nuremberg

established his reputation across Europe as painter

, printmaker, mathematician

, engraver, and theorist when he was still in his twenties and secured his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern Renaissance

.

.svg.png)

In the early 16th century there was much discontent occasioned by abuses such as indulgence

In the early 16th century there was much discontent occasioned by abuses such as indulgence

s in the Catholic Church, and a general desire for reform.

In 1517 the Reformation

began with the publication of Martin Luther

's 95 Theses

; he had posted them in the town square, and gave copies of them to German nobles, but it is debated whether he nailed them to the church door in Wittenberg

as is commonly said. The list detailed 95 assertions Luther believed to show corruption and misguidance within the Catholic Church. One often cited example, though perhaps not Luther's chief concern, is a condemnation of the selling of indulgences; another prominent point within the 95 Theses is Luther's disagreement both with the way in which the higher clergy, especially the pope, used and abused power, and with the very idea of the pope.

In 1521 Luther was outlawed at the Diet of Worms

. But the Reformation spread rapidly, helped by the Emperor Charles V

's wars with France and the Turks

. Hiding in the Wartburg Castle

, Luther translated the Bible from Latin to German, establishing the basis of the German language. A curious fact is that Luther spoke a dialect which had minor importance in the German language of that time. After the publication of his Bible, his dialect suppressed the others and evolved into what is now the modern German.

In 1524 the German Peasants' War

broke out in Swabia

, Franconia

and Thuringia

against ruling princes and lords, following the preachings of Reformist priests. But the revolts, which were assisted by war-experienced noblemen like Götz von Berlichingen

and Florian Geyer

(in Franconia), and by the theologian Thomas Münzer (in Thuringia), were soon repressed by the territorial princes. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 German peasants were massacred during the revolt, usually after the battles had ended. With the protestation

of the Lutheran princes at the Reichstag

of Speyer

(1529) and rejection of the Lutheran "Augsburg Confession" at Augsburg (1530), a separate Lutheran church emerged.

From 1545 the Counter-Reformation began in Germany. The main force was provided by the Jesuit order

, founded by the Spaniard Ignatius of Loyola

. Central and northeastern Germany were by this time almost wholly Protestant, whereas western and southern Germany remained predominantly Catholic. In 1547, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V defeated the Schmalkaldic League

, an alliance of Protestant rulers.

The Peace of Augsburg

in 1555 brought recognition of the Lutheran faith. But the treaty also stipulated that the religion of a state was to be that of its ruler (Cuius regio, eius religio

).

In 1556 Charles V

abdicated. The Habsburg Empire was divided, as Spain

was separated from the Imperial possessions.

In 1608/1609 the Protestant Union

and the Catholic League

were formed.

The Reformation was a triumph of literacy and the new printing press. Luther's translation of the Bible into German was a decisive moment in the spread of literacy, and stimulated as well the printing and distribution of religious books and pamphlets. From 1517 onward religious pamphlets flooded Germany and much of Europe. By 1530 over 10,000 publications are known, with a total of ten million copies. The Reformation was thus a media revolution. Luther strengthened his attacks on Rome by depicting a "good" against "bad" church. From there, it became clear that print could be used for propaganda in the Reformation for particular agendas. Reform writers used pre-Reformation styles, clichés, and stereotypes and changed items as needed for their own purposes. Especially effective were Luther's Small Catechism, for use of parents teaching their children, and Larger Catechism, for pastors. Using the German vernacular they expressed the Apostles' Creed in simpler, more personal, Trinitarian language. Illustrations in the newly translated Bible and in many tracts popularized Luther's ideas. Lucas Cranach the Elder

The Reformation was a triumph of literacy and the new printing press. Luther's translation of the Bible into German was a decisive moment in the spread of literacy, and stimulated as well the printing and distribution of religious books and pamphlets. From 1517 onward religious pamphlets flooded Germany and much of Europe. By 1530 over 10,000 publications are known, with a total of ten million copies. The Reformation was thus a media revolution. Luther strengthened his attacks on Rome by depicting a "good" against "bad" church. From there, it became clear that print could be used for propaganda in the Reformation for particular agendas. Reform writers used pre-Reformation styles, clichés, and stereotypes and changed items as needed for their own purposes. Especially effective were Luther's Small Catechism, for use of parents teaching their children, and Larger Catechism, for pastors. Using the German vernacular they expressed the Apostles' Creed in simpler, more personal, Trinitarian language. Illustrations in the newly translated Bible and in many tracts popularized Luther's ideas. Lucas Cranach the Elder

(1472–1553), the great painter patronized by the electors of Wittenberg, was a close friend of Luther, and illustrated Luther's theology for a popular audience. He dramatized Luther's views on the relationship between the Old and New Testaments, while remaining mindful of Luther's careful distinctions about proper and improper uses of visual imagery.

ravaged in the Holy Roman Empire. The causes were the conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, the efforts by the various states within the Empire to increase their power and the Catholic Emperor's attempt to achieve the religious and political unity of the Empire. The immediate occasion for the war was the uprising of the Protestant nobility of Bohemia against the emperor, but the conflict was widened into a European War by the intervention of King Christian IV of Denmark

(1625–29), Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

(1630–48) and France under Cardinal Richelieu. Germany became the main theatre of war and the scene of the final conflict between France and the Habsburgs for predominance in Europe.

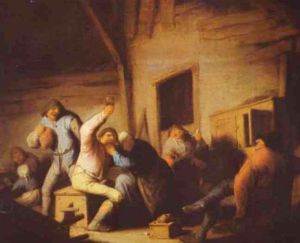

The fighting often was out of control, with marauding bands of hundreds or thousands of starving soldiers spreading plague, plunder, and murder. The armies that were under control moved back and forth across the countryside year after year, levying heavy taxes on cities, and seizing the animals and food stocks of the peasants without payment. The enormous social disruption over three decades caused a dramatic decline in population because of killings, disease, crop failures, declining birth rates and random destruction, and the out-migration of terrified people. One estimate shows a 38% drop from 16 million people in 1618 to 10 million by 1650, while another shows "only" a 20% drop from 20 million to 16 million. The Altmark

and Württemberg

regions especially hard hit. It took generations for Germany to fully recover. The war ended in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia

. Imperial territory was lost to France and Sweden and the Netherlands officially left the Empire. The imperial power declined further as the states' rights were increased.

Nicolaus Copernicus

from Toruń

(Thorn) published his work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

and became the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric

cosmology

which displaced the Earth

from the center of the universe

. Almost 70 years after Copernicus' death and building on his theories, mathematician

, astronomer

and astrologer Johannes Kepler

from Stuttgart

would be a key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution

. He is best known for his eponym

ous laws of planetary motion

, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova

and Harmonices Mundi. These works also influenced contemporary scientist Galileo Galilei

and provided one of the foundations for Isaac Newton

's theory of universal gravitation

.

From 1640, Brandenburg-Prussia

From 1640, Brandenburg-Prussia

had started to rise under the Great Elector, Frederick William

. The Peace of Westphalia

in 1648 strengthened it even further, through the acquisition of East Pomerania. From 1713 to 1740, King Frederick William I

, also known as the "Soldier King", established a highly centralized, militarized state with a heavily rural population of about three million (compared to the nine million in Austria).

In terms of the boundaries of 1914, Germany in 1700 had a population of 16 million, increasing slightly to 17 million by 1750, and growing more rapidly to 24 million by 1800. Wars continued, but they were no longer so devastating to the civilian population; famines and major epidemics did not occur, but increased agricultural productivity led to a higher birth rate, and a lower death rate.

conquered parts of Alsace and Lorraine

(1678–1681), and had invaded and devastated the Palatinate (1688–1697) in the War of Palatinian Succession

. Louis XIV benefited from the Empire's problems with the Turks, which were menacing Austria. Louis XIV ultimately had to relinquish the Palatinate. Afterwards Hungary was reconquered from the Turks; Austria, under the Habsburgs, developed into a great power.

Afterwards Hungary was reconquered from the Turks; Austria, under the Habsburgs, developed into a great power.

In the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748) Maria Theresa

fought successfully for recognition of her succession to the throne. But in the Silesian Wars

and in the Seven Years' War

she had to cede Silesia to Frederick II, the Great, of Prussia

. After the Peace of Hubertsburg in 1763 between Austria, Prussia

and Saxony

, Prussia became a European great power. This gave the start to the rivalry between Prussia and Austria for the leadership of Germany.

From 1763, against resistance from the nobility and citizenry, an "enlightened absolutism

" was established in Prussia and Austria, according to which the ruler governed according to the best precepts of the philosophers. The economies developed and legal reforms were undertaken, including the abolition of torture and the improvement in the status of Jews; the emancipation of the peasants slowly began. Compulsory education began.

In 1772–1795 Prussia took part in the partitions of Poland

, occupying western territories of Polish–Lithuanian commonwealth, which led to centuries of Polish resistance against Germanization.

was especially unfortunate in this regard; it was a rural land with very heavy debts and few growth centers. Saxony

was in economically good shape, although its government was seriously mismanaged, and numerous wars had taken their toll. In Württemberg

the duke lavished funds on palaces, mistresses, great celebration, and hunting expeditions.

In Hesse-Kassel

In Hesse-Kassel

, the Landgrave Frederick II, ruled 1760-1785 as an enlightened despot, and raised money by renting soldiers (called "Hessians") to Great Britain

to help fight the American Revolutionary War

. He combined Enlightenment ideas with Christian values, cameralist plans for central control of the economy, and a militaristic approach toward diplomacy.

Hanover did not have to support a lavish court—its rulers were also kings of England and resided in London. George III

, elector (ruler) from 1760 to 1820, never once visited Hanover. The local nobility who ran the country opened the University of Göttingen in 1737; it soon became a world-class intellectual center. Baden

Baden

sported perhaps the best government of the smaller states. Karl Friedrich ruled well for 73 years (1738–1811) and was an enthusiast for The Enlightenment; he abolished serfdom in 1783. Many of the city-states of Germany were run by bishops, who in reality were from powerful noble families and showed scant interest in religion. None developed a significant reputation for good government.

Between 1807 and 1871, Prussia swallowed up many of the smaller states, with minimal protest, then went on to found the German Empire. In the process, Prussia became too heterogeneous, lost its identity, and by the 1930s had become an administrative shell of little importance.

, dominated not only the localities, but also the Prussian court, and especially the Prussian army. Increasingly after 1815, a centralized Prussian government based in Berlin took over the powers of the nobles, which in terms of control over the peasantry had been almost absolute. To help the nobility avoid indebtedness, Berlin set up a credit institution to provide capital loans in 1809, and extended the loan network to peasants in 1849. When the German Empire was established in 1871, the Junker nobility controlled the army and the Navy, the bureaucracy, and the royal court; they generally set governmental policies.

Peasants continued to center their lives in the village, where they were members of a corporate body and help manage the community resources and monitor the community life. In the East, they were serfs who were bound prominently to parcels of land. In most of Germany, farming was handled by tenant farmers who paid rents and obligatory services to the landlord, who was typically a nobleman. Around 1800 the Catholic monasteries, which had large land holdings, were nationalized and sold off by the government. In Bavaria they had controlled 56% of the land Peasant leaders supervised the fields and ditches and grazing rights, maintained public order and morals, and supported a village court which handled minor offenses. Inside the family the patriarch made all the decisions, and tried to arrange advantageous marriages for his children. Much of the villages' communal life centered around church services and holy days. In Prussia, the peasants drew lots to choose conscripts required by the army. The noblemen handled external relationships and politics for the villages under their control, and were not typically involved in daily activities or decisions.

Peasants continued to center their lives in the village, where they were members of a corporate body and help manage the community resources and monitor the community life. In the East, they were serfs who were bound prominently to parcels of land. In most of Germany, farming was handled by tenant farmers who paid rents and obligatory services to the landlord, who was typically a nobleman. Around 1800 the Catholic monasteries, which had large land holdings, were nationalized and sold off by the government. In Bavaria they had controlled 56% of the land Peasant leaders supervised the fields and ditches and grazing rights, maintained public order and morals, and supported a village court which handled minor offenses. Inside the family the patriarch made all the decisions, and tried to arrange advantageous marriages for his children. Much of the villages' communal life centered around church services and holy days. In Prussia, the peasants drew lots to choose conscripts required by the army. The noblemen handled external relationships and politics for the villages under their control, and were not typically involved in daily activities or decisions.

The emancipation of the serfs came in 1770–1830, beginning with Schleswig in 1780. The peasants were now ex-serfs and could own their land, buy and sell it, and move about freely. The nobles approved for now they could buy land owned by the peasants. The chief reformer was Baron vom Stein (1757–1831), who was influenced by The Enlightenment, especially the free market ideas of Adam Smith

. The end of serfdom raised the personal legal status of the peasantry. A bank was set up so that landowner could borrow government money to buy land from peasants (the peasants were not allowed to use it to borrow money to buy land until 1850). The result was that the large landowners obtained larger estates, and many peasant became landless tenants, or moved to the cities or to America. The other German states imitated Prussia after 1815. In sharp contrast to the violence that characterized land reform in the French Revolution, Germany handled it peacefully. In Schleswig the peasants, who had been influenced by the Enlightenment, played an active role; elsewhere they were largely passive. Indeed, for most peasants, customs and traditions continued largely unchanged, including the old habits of deference to the nobles whose legal authority remains quite strong over the villagers. Although the peasants were no longer tied to the same land like serfs had been, the old paternalistic relationship in East Prussia lasted into the 20th century.

The agrarian reforms in northwestern Germany in the era 1770–1870 were driven by progressive governments and local elites. They abolished feudal obligations and divided collectively owned common land into private parcels and thus created a more efficient market-oriented rural economy. It produced increased productivity and population growth. It strengthened the traditional social order because wealthy peasants obtained most of the former common land, while the rural proletariat was left without land; many left for the cities or America. Meanwhile the division of the common land served as a buffer preserving social peace between nobles and peasants. In the east the serfs were emancipated but the Junker class

maintained its large estates and monopolized political power.

Before 1750 the German upper classes looked to France for intellectual, cultural and architectural leadership; French was the language of high society. By the mid-18th century the "Aufklärung" (The Enlightenment) had transformed German high culture in music, philosophy, science and literature. Christian Wolff

Before 1750 the German upper classes looked to France for intellectual, cultural and architectural leadership; French was the language of high society. By the mid-18th century the "Aufklärung" (The Enlightenment) had transformed German high culture in music, philosophy, science and literature. Christian Wolff

(1679–1754) was the pioneer as a writer who expounded the Enlightenment to German readers; he legitimized German as a philosophic language.

Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803) broke new ground in philosophy and poetry, as a leader of the Sturm und Drang

movement of proto-Romanticism. Weimar Classicism

("Weimarer Klassik") was a cultural and literary movement based in Weimar that sought to establish a new humanism by synthesizing Romantic, classical and Enlightenment ideas. The movement, from 1772 until 1805, involved Herder as well as polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

(1749–1832) and Friedrich Schiller

(1759–1805), a poet and historian. Herder argued that every folk had its own particular identity, which was expressed in its language and culture. This legitimized the promotion of German language and culture and helped shape the development of German nationalism. Schiller's plays expressed the restless spirit of his generation, depicting the hero's struggle against social pressures and the force of destiny.

German music, sponsored by the upper classes, came of age under composers Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685–1750), Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(1756–1791).

In remote Königsberg

philosopher Immanuel Kant

(1724–1804) tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom and political authority. Kant's work contained basic tensions that would continue to shape German thought—and indeed all of European philosophy—well into the 20th century.

The German Enlightenment won the support of princes, aristocrats and the middle classes and permanently reshaped the culture.

German intellectuals celebrated the outbreak of the French Revolution, hoping to see the triumph of Reason and The Enlightenment. The royal courts in Vienna and Berlin denounced the overthrow of the king and the threatened spread of notions of liberty, equality, and fraternity. By 1793 the execution of the French king and the onset of the Terror disillusioned the Bildungsbürgertum (educated middle classes). Reformers said the solution was to have faith in the ability of Germans to reform their laws and institutions in peaceful fashion.

German intellectuals celebrated the outbreak of the French Revolution, hoping to see the triumph of Reason and The Enlightenment. The royal courts in Vienna and Berlin denounced the overthrow of the king and the threatened spread of notions of liberty, equality, and fraternity. By 1793 the execution of the French king and the onset of the Terror disillusioned the Bildungsbürgertum (educated middle classes). Reformers said the solution was to have faith in the ability of Germans to reform their laws and institutions in peaceful fashion.

Europe was racked by two decades of war revolving around France's efforts to spread its revolutionary ideals, and the opposition of reactionary royalty. The German lands saw armies marching back and forth, bringing devastation (albeit on a far lower scale than the Thirty Years War), but also bringing new ideas of liberty and civil rights for the people. War broke out in 1792 as Austria and Prussia invaded France, but were defeated at the Battle of Valmy

. Prussia and Austria ended their failed wars with France but (with Russia) partitioned Poland among themselves in 1793 and 1795. The French took control of the Rhineland, imposed French-style reforms, abolished feudalism, established constitutions, promoted freedom of religion, emancipated Jews, opened the bureaucracy to ordinary citizens of talent, and forced the nobility to share power with the rising middle class. Napoleon created the Kingdom of Westphalia

(1807–1813) as a model state. These reforms proved largely permanent and modernized the western parts of Germany. When the French tried to impose the French language, German opposition grew in intensity. A Second Coalition of Britain, Russia, and Austria then attacked France but failed. Napoleon established direct or indirect control over most of western Europe, including the German states apart from Prussia and Austria. The old Holy Roman Empire was little more than a farce; Napoleon simply abolished it in 1806 while forming new countries under his control. In Germany Napoleon set up the Confederation of the Rhine

comprising most of the German states except Prussia and Austria.

Prussia tried to remain neutral while imposing tight controls on dissent, but with German nationalism sharply on the rise the small nation blundered by going to war with Napoleon in 1806. Its economy was weak, its leadership poor, and the once mighty Prussian army was a hollow shell. Napoleon easily crushed it at the Battle of Jena. Napoleon occupied Berlin and Prussia paid dearly. Prussia lost its recently acquired territories in western Germany, its army was reduced to 42,000 men, no trade with Britain was allowed, and Berlin had to pay Paris heavy reparations and fund the French army of occupation . Saxony changed sides to support Napoleon and join his Confederation of the Rhine; its elector was rewarded with the title of king and given a slice of Poland taken from Prussia. After Napoleon's fiasco in Russia in 1812, including the deaths of many Germans in his invasion army, Prussia joined with Russia. Major battles followed in quick order, and when Austria switched sides to oppose Napoleon his situation grew tenuous. He was defeated in a great Battle of Leipzig

in late 1813, and Napoleon's empire started to collapse. One after another the German states switched to oppose Napoleon, but he rejected peace terms. Allied armies invaded France in early 1814, Paris fell, and in April Napoleon surrendered. He returned for 100 days in 1815, but was finally defeated by the British and German armies at Waterloo. Prussia was the big winner at the Vienna peace conference, gaining extensive territory.

), warfare, the 1848 revolution, and the inability of the multiple members to compromise. It was replaced by the North German Confederation

in 1866.

take place in Germany. It was a transition from high birth rates and high death rates to low birth and death rates as the country developed from a pre-industrial to a modernized agriculture and supported a fast-growing industrialized urban economic system. In previous centuries, the shortage of land meant that not everyone could marry, and marriages took place after age 25. The high birthrate was offset by a very high rate of infant mortality, plus periodic epidemics and harvest failures. After 1815, increased agricultural productivity met a larger food supply, and a decline in famines, epidemics, and malnutrition. This allowed couples to marry earlier, and have more children. Arranged marriages became uncommon as young people were now allowed to choose their own marriage partners, subject to a veto by the parents. The upper and middle classes began to practice birth control, and a little later so too did the peasants.

summed up the advantages to be derived from the development of the railway system in 1841:

Lacking a technological base at first, the Germans imported their engineering and hardware from Britain, but quickly learned the skills needed to operate and expand the railways. In many cities, the new railway shops were the centres of technological awareness and training, so that by 1850, Germany was self sufficient in meeting the demands of railroad construction, and the railways were a major impetus for the growth of the new steel industry. Observers found that even as late as 1890, their engineering was inferior to Britain’s. However, German unification in 1870 stimulated consolidation, nationalisation into state-owned companies, and further rapid growth. Unlike the situation in France, the goal was support of industrialisation, and so heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts, and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen. By 1880, Germany had 9,400 locomotives pulling 43,000 passengers and 30,000 tons of freight a day, and forged ahead of France.

(1749–1832), turned to Romanticism

after a period of Enlightenment

. Philosophical thought was decisively shaped by Immanuel Kant

(1724–1804). Ludwig van Beethoven

(1770–1827) was the leading composer of Romantic music

. His use of tonal architecture in such a way as to allow significant expansion of musical forms and structures was immediately recognized as bringing a new dimension to music. His later piano music and string quartets, especially, showed the way to a completely unexplored musical universe, and influenced Franz Schubert

(1797–1828) and Robert Schumann

(1810–1856). In opera, a new Romantic atmosphere combining supernatural terror and melodramatic plot in a folkloric context was first successfully achieved by Carl Maria von Weber

(1786–1826) and perfected by Richard Wagner

(1813–1883) in his Ring Cycle. The Brothers Grimm

(1785-1863 & 1786-1859) not only wrote the popular Grimm's Fairy Tales

, but were among the founding fathers of German philology and German studies

.

At the universities high-powered professors developed international reputations, especially in the humanities led by history and philology, which brought a new historical perspective to the study of political history, theology, philosophy, language, and literature. With Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

(1770–1831) in philosophy, Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) in theology and Leopold von Ranke

(1795–1886) in history, the University of Berlin

, founded in 1810, became the world's leading university. Von Ranke, for example, professionalized history and set the world standard for historiography. By the 1830s mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology had emerged with world class science, led by Alexander von Humboldt

(1769–1859) in natural science and Carl Friedrich Gauss

(1777–1855) in mathematics. Young intellectuals often turned to politics, but their support for the failed Revolution of 1848 forced many into exile.

After the fall of Napoleon, Europe's statesmen convened in Vienna in 1815 for the reorganisation of European affairs, under the leadership of the Austrian Prince Metternich

After the fall of Napoleon, Europe's statesmen convened in Vienna in 1815 for the reorganisation of European affairs, under the leadership of the Austrian Prince Metternich

. The political principles agreed upon at this Congress of Vienna

included the restoration, legitimacy and solidarity of rulers for the repression of revolutionary and nationalist ideas.

The German Confederation

(Deutscher Bund) was founded, a loose union of 39 states (35 ruling princes and 4 free cities) under Austrian leadership, with a Federal Diet (Bundestag) meeting in Frankfurt am Main. It was a loose coalition that failed to satisfy most nationalists. The member states largely went their own way, and Austria had its own interests.

In 1819 a student radical assassinated the reactionary playwright August von Kotzebue, who had scoffed at liberal student organisations. In one of the few major actions of the German Confederation, Prince Metternich called a conference that issued the repressive Carlsbad Decrees

, designed to suppress liberal agitation against the conservative governments of the Germany states. The Decrees terminated the fast-fading nationalist fraternities '(Burschenschaften),' removed liberal university professors, and expanded the censorship of the press. The decrees began the "persecution of the demagogues", which was directed against individuals who were accused of spreading revolutionary and nationalist ideas. Among the persecuted were the poet Ernst Moritz Arndt

, the publisher Johann Joseph Görres and the "Father of Gymnastics" Ludwig Jahn.

In 1834 the Zollverein

was established, a customs union between Prussia and most other German states, but excluding Austria. As industrialisation developed, the need for a unified German state with a uniform currency, legal system, and government became more and more obvious.

in the German states. In May the German National Assembly (the Frankfurt Parliament

) met in Frankfurt to draw up a national German constitution.

But the 1848 revolution turned out to be unsuccessful: King Frederick William IV of Prussia

refused the imperial crown, the Frankfurt parliament was dissolved, the ruling princes repressed the risings by military force and the German Confederation was re-established by 1850. Many leaders went into exile, including a number who went to the United States and became a political force there.

In 1857, the king had a stroke and his brother William

In 1857, the king had a stroke and his brother William

became regent and became King William I in 1861. Although conservative, William I was far more pragmatic. His most significant accomplishment was naming Otto von Bismarck

as chancellor in 1862. The combination of Bismarck, Defense Minister Albrecht von Roon, and Field Marshal Helmut von Moltke set the stage for victories over Denmark, Austria and France, and led to the unification of Germany. The obstacle to German unification was Austria, and Bismarck solved the problem with a series of wars that united the German states north of Austria.

In 1863-64, disputes between Prussia and Denmark grew over Schleswig

, which was not part of the German Confederation, and which Danish nationalists wanted to incorporate into the Danish kingdom. The dispute led to the short Second War of Schleswig

in 1864. Prussia, joined by Austria, defeated Denmark easily and occupied Jutland. The Danes were forced to cede both the duchy of Schleswig and the duchy of Holstein to Austria and Prussia. In the aftermath, the management of the two duchies caused escalating tensions between Austria and Prussia. The former wanted the duchies to become an independent entity within the German Confederation, while the latter wanted to annex them. The Seven Weeks War between Austria and Germany broke out in June 1866 and in July the two armies clashed at Sadowa-Koniggratz in Bohemia in an enormous battle involving half a million men. The Prussian breech-loading needle guns carried the day over the Austrians with their slow muzzle-loading rifles, who lost a quarter of their army in the battle. Austria ceded Venice

to Italy, but Bismarck was deliberately lenient with the loser to keep alive a long-term alliance with Austria in a subordinate role. Now the French faced an increasingly strong Prussia.

In 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved. In its place the North German Federation (German Norddeutscher Bund) was established, under the leadership of Prussia. Austria was excluded from it. The Austrian influence in Germany that had begun in the 15th century finally came to an end.

In 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved. In its place the North German Federation (German Norddeutscher Bund) was established, under the leadership of Prussia. Austria was excluded from it. The Austrian influence in Germany that had begun in the 15th century finally came to an end.

The North German Federation was a transitional organisation that existed from 1867 to 1871, between the dissolution of the German Confederation and the founding of the German Empire. The unification of the German states

into a single economic, political and administrative unit excluded the Austrian territories and the Habsburgs.

After Germany was united by Otto von Bismarck

into the "Second German Reich", he determined German politics until 1890. Bismarck tried to foster alliances in Europe, on one hand to contain France, and on the other hand to consolidate Germany's influence in Europe. On the domestic front Bismarck tried to stem the rise of socialism by anti-socialist laws, combined with an introduction of health care and social security. At the same time Bismarck tried to reduce the political influence of the emancipated Catholic minority in the Kulturkampf

, literally "culture struggle". The Catholics only grew stronger, forming the Center (Zentrum) Party. Germany grew rapidly in industrial and economic power, matching Britain by 1900. Its highly professional army was the best in the world, but the navy could never catch up with Britain's Royal Navy.

In 1888, the young and ambitious Kaiser Wilhelm II became emperor. He could not abide advice, least of all from the most experienced politician and diplomat in Europe, so he fired Bismarck. The Kaiser opposed Bismarck's careful foreign policy and wanted Germany to pursue colonialist policies, as Britain and France had been doing for decades, as well as build a navy that could match the British. The Kaiser promoted active colonization of Africa and Asia for those areas that were not already colonies of other European powers; his record was notoriously brutal and set the stage for genocide. The Kaiser took a mostly unilateral approach in Europe with as main ally the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and an arms race with Britain, which eventually led to the situation in which the assassination of the Austrian-Hungarian crown prince could spark off World War I

.

Disputes between France and Prussia increased. In 1868, the Spanish queen Isabella II was expelled by a revolution, leaving that country's throne vacant. When Prussia tried to put a Hohenzollern candidate, Prince Leopold, on the Spanish throne, the French angrily protested. In July 1870, France declared war on Prussia (the Franco-Prussian War

Disputes between France and Prussia increased. In 1868, the Spanish queen Isabella II was expelled by a revolution, leaving that country's throne vacant. When Prussia tried to put a Hohenzollern candidate, Prince Leopold, on the Spanish throne, the French angrily protested. In July 1870, France declared war on Prussia (the Franco-Prussian War

). The debacle was swift. A succession of German victories in northeastern France followed, and one French army was besieged at Metz. After a few weeks, the main army was finally forced to capitulate in the fortress of Sedan

. French Emperor Napoleon III was taken prisoner and a republic hastily proclaimed in Paris. The new government, realising that a victorious Germany would demand territorial acquisitions, resolved to fight on. They began to muster new armies, and the Germans settled down to a grim siege of Paris. The starving city surrendered in January 1871, and the Prussian army staged a victory parade in it. France was forced to pay indemnities of 5 billion francs and cede Alsace-Lorraine. It was a bitter peace that would leave the French thirsting for revenge.

During the Siege of Paris

, the German princes assembled in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles

and proclaimed the Prussian King Wilhelm I as the "German Emperor" on 18 January 1871. The German Empire was thus founded, with 25 states, three of which were Hanseatic free cities, and Bismarck, again, served as Chancellor. It was dubbed the "Little German" solution, since Austria was not included. The new empire was characterised by a great enthusiasm and vigor. There was a rash of heroic artwork in imitation of Greek and Roman styles, and the nation possessed a vigorous, growing industrial economy, while it had always been rather poor in the past. The change from the slower, more tranquil order of the old Germany was very sudden, and many, especially the nobility, resented being displaced by the new rich. And yet, the nobles clung stubbornly to power, and they, not the bourgeois, continued to be the model that everyone wanted to imitate. In imperial Germany, possessing a collection of medals or wearing a uniform was valued more than the size of one's bank account, and Berlin never became a great cultural center as London, Paris, or Vienna were. The empire was distinctly authoritarian in tone, as the 1871 constitution gave the emperor exclusive power to appoint or dismiss the chancellor. He also was supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces and final arbiter of foreign policy. But freedom of speech, association, and religion were nonetheless guaranteed by the constitution.

Bismarck's domestic policies as Chancellor of Germany were characterised by his fight against perceived enemies of the Protestant Prussian state. In the so-called Kulturkampf

(1872–1878), he tried to limit the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and of its political arm, the Catholic Centre Party, through various measures—like the introduction of civil marriage—but without much success. The Kulturkampf antagonised many Protestants as well as Catholics, and was eventually abandoned. Millions of non-Germans subjects in the German Empire, like the Polish, Danish and French minorities, were discriminated against http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=772http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=771 and a policy of Germanisation

was implemented.

The rise of the Socialist Workers' Party (later known as the Social Democratic Party of Germany

, SPD), declared its aim to establish Peacefully a new socialist order through the transformation of existing political and social conditions. From 1878, Bismarck tried to repress the social democratic movement by outlawing the party's organisation

, its assemblies and most of its newspapers. When it finally was allowed to run candidates the Social Democrats were stronger than ever.

Bismark built on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that began as early as in the 1840s. In the 1880s he introduced old age pensions, accident insurance, medical care and unemployment insurance that formed the basis of the modern European welfare state. His paternalistic programs won the support of German industry because its goals were to win the support of the working classes for the Empire and reduce the outflow of immigrants to America, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist. Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers by his high tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.

" in Prussia to reduce the power of the Catholic Church in public affairs, and keep the Poles under control. Thousands of priests and bishops were harassed or imprisoned, with large fines and closures of Catholic churches and schools. The Kulturkampf did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria

. Bismarck sought to appeal to liberals and Protestants but he failed because the Catholics were unanimous in their resistance and organized themselves to fight back politically, using their strength in other states besides Prussia. German nationalists feared the Polonization of the Prussian East. Bismarck saw the Kulturkampf as a means of stopping this trend, which was led by the Catholic clergy in West Prussia, Poznania and Silesia. The Poles were subjected to harassment in the fields of education, economic activity and the administration; in German was declared to be the only official language, but in practice the Poles only adhered more closely to their traditions.

There was little or no violence, but the new Catholic Center Party

won a fourth of the seats in the Reichstag (Imperial Parliament), and its middle position on most issues allowed it to play a decisive role in the formation of majorities. The culture war gave secularists and socialists an opportunity to attack all religions, an outcome that distressed the Protestants, including Bismarck, who was a devout pietistic Protestant. The Catholic anti-liberalism was led by Pope Pius IX

; his death in 1878 allowed Bismarck to open negotiations with Pope Leo XIII

, and led to the abandonment of the Kulturkampf in stages in the early 1880s.

The Three Emperor's League (Dreikaisersbund) was signed in 1872 by Russia, Austria and Germany. It stated that republicanism and socialism were common enemies and that the three powers would discuss any matters concerning foreign policy. Bismarck needed good relations with Russia in order to keep France isolated. In 1877–1878, Russia fought a victorious war with the Ottoman Empire and attempted to impose the Treaty of San Stefano on it. This upset the British in particular, as they were long concerned with preserving the Ottoman Empire and preventing a Russian takeover of the Bosporous Straits. Germany hosted the Congress of Berlin, whereby a more moderate peace settlement was agreed to. Afterwards, Russia turned its attention eastward to Asia and remained largely inactive in European politics for the next 25 years. Germany had no direct interest in the Balkans however, which was largely an Austrian and Russian sphere of influence, although King Carol of Romania was a German prince.

In 1879, Bismarck formed a Dual Alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary, with the aim of mutual military assistance in the case of an attack from Russia, which was not satisfied with the agreement reached at the Congress of Berlin. The establishment of the Dual Alliance led Russia to take a more conciliatory stance, and in 1887, the so-called Reinsurance Treaty

was signed between Germany and Russia: in it, the two powers agreed on mutual military support in the case that France attacked Germany, or in case of an Austrian attack on Russia. In 1882, Italy joined the Dual Alliance to form a Triple Alliance

. Italy wanted to defend its interests in North Africa

against France's colonial policy. In return for German and Austrian support, Italy committed itself to assisting Germany in the case of a French military attack.

For a long time, Bismarck had refused to give in widespread public demands to give Germany "a place in the sun", through the acquisition of overseas colonies. In 1880 Bismarck gave way, and a number of colonies were established overseas: in Africa, these were Togo

, the Cameroons

, German South-West Africa

and German East Africa

; in Oceania

, they were German New Guinea

, the Bismarck Archipelago

and the Marshall Islands

. In fact, it was Bismarck himself who helped initiate the Berlin Conference

of 1885. He did it to "establish international guidelines for the acquisition of African territory," (see Colonisation of Africa

). This conference was an impetus for the "Scramble for Africa" and "New Imperialism

".

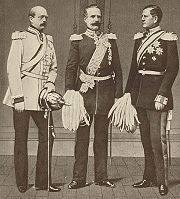

In 1888, the old emperor William I died at the age of 90. His son Frederick III, the hope of German liberals, succeeded him, but was already stricken with throat cancer and died three months later. Frederick's son William II then became emperor at the age of 29. He was the antithesis of old, conservative Germans like Bismarck, addicted to the new imperialism that was taking place in Asia and Africa. He sought to make Germany a great world power with a navy to rival Britain's. Bismarck hoped to marginalise him just as he had marginalised his grandfather, but William II desired to be his own master. Having a left arm withered by childhood polio, he was painfully insecure and desired above all to be loved by the people. Bismarck's schemes to dominate the emperor and hold onto his own power failed, and he was forced to resign in March 1890.

In 1888, the old emperor William I died at the age of 90. His son Frederick III, the hope of German liberals, succeeded him, but was already stricken with throat cancer and died three months later. Frederick's son William II then became emperor at the age of 29. He was the antithesis of old, conservative Germans like Bismarck, addicted to the new imperialism that was taking place in Asia and Africa. He sought to make Germany a great world power with a navy to rival Britain's. Bismarck hoped to marginalise him just as he had marginalised his grandfather, but William II desired to be his own master. Having a left arm withered by childhood polio, he was painfully insecure and desired above all to be loved by the people. Bismarck's schemes to dominate the emperor and hold onto his own power failed, and he was forced to resign in March 1890.

. The foreign office argued that long-term coalition between France and Russia had to fall apart, secondly Russia and Britain would never get together; finally that Britain would eventually seek an alliance with Germany. Germany refused to renew its treaties with Russia. But Russia did form a closer relationship with France by the Dual Alliance of 1894

, since both were worried about the possibilities of German aggression. Furthermore, Anglo German relations cooled as Germany aggressively tried to build a new empire and engaged in a naval race with Britain; London refused to agree to the formal alliance that Germany sought. Berlin's analysis proved mistaken on every point, leading to Germany's increasing isolation and its dependence on the Triple Alliance

, which brought together Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. The Triple Alliance was undermined by differences between Austria and Italy, and in 1915 Italy switched sides.

Meanwhile the German Navy under Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

had ambitions to rival the great British Navy, and dramatically expanded its fleet in the early 20th century to protect the colonies and exert power worldwide. Tirpitz started a programme of warship construction in 1898. In 1890, Germany had gained the island of Heligoland in the North Sea from Britain in exchange for the African island of Zanzibar and proceeded to construct a great naval base there. This posed a direct threat to British hegemony on the seas, with the result that negotiations for an alliance between Germany and Britain broke down. The British however kept well ahead in the naval race by the introduction of the highly advanced new Dreadnought

battleship in 1907.

In the First Moroccan Crisis

of 1905, Germany nearly came to blows with Britain and France when the latter attempted to establish a protectorate over Morocco. The Germans were upset at having not been informed about French intentions, and declared their support for Moroccan independence. William II made a highly provocative speech regarding this. The following year, a conference was held in which all of the European powers except Austria-Hungary (by now little more than a German satellite) sided with France. A compromise was brokered by the United States where the French relinquished some, but not all, control over Morocco.

The Second Moroccan Crisis

of 1911 saw another dispute over Morocco erupt when France tried to suppress a revolt there. Germany, still smarting from the previous quarrel, agreed to a settlement whereby the French ceded some territory in central Africa in exchange for Germany renouncing any right to intervene in Moroccan affairs. This confirmed French control over Morocco, which became a full protectorate of that country in 1912.

Based on its leadership in chemical research in the universities and industrial laboratories, Germany became dominant in the world's chemical industry in the late 19th century. At first the production of dyes was critical.

Based on its leadership in chemical research in the universities and industrial laboratories, Germany became dominant in the world's chemical industry in the late 19th century. At first the production of dyes was critical.

" (global policy), the German Empire demanded its "Platz an der Sonne" (Place in the sun). Bismark began the process, and by 1884 had acquired German New Guinea

. By the 1890s, German colonial expansion in Asia and the Pacific (Kiauchau

in China, the Marianas

, the Caroline Islands

, Samoa

) led to frictions with Britain, Russia, Japan and the United States. The construction of the Baghdad Railway

, financed by German banks, was designed to eventually connect Germany with the Turkish Empire and the Persian Gulf

, but it also collided with British and Russian geopolitical interests. The largest colonial enterprises were in Africa, where the harsh treatment of the Nama and Herero in what is now Namibia

in 1906-07 led to charges of genocide against the Germans.

Ethnic demands for nation states upset the balance between the empires that dominated Europe, leading to World War I

Ethnic demands for nation states upset the balance between the empires that dominated Europe, leading to World War I

, which started in August 1914. Germany stood behind its ally Austria in a confrontation with Serbia, but Serbia was under the protection of Russia, which was allied to France. Germany was the leader of the Central Powers, which included Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and later Bulgaria, arrayed against the Allies, which comprised chiefly Russia, France, Britain, and in 1915 Italy. The United States joined with the Allies in April 1917. Fighting was most ferocious on the stalemated Western Front. More wide open was the fighting on the Eastern Front, which Germany controlled by 1917 as Russia was forced out of the war.

. But it failed due to Belgian resistance, Berlin's diversion of troops, and very stiff French resistance on the Marne

, north of Paris. The Western Front

became an extremely bloody battleground until early 1918, with forces moving a few hundred yards at best. In the east there were decisive victories against the Russian army, the trapping and defeat of large parts of the Russian contingent at the Battle of Tannenberg

, followed by huge Austrian and German successes led to a breakdown of Russian forces in 1917 and an imposed peace on the newly created USSR under Lenin. The British imposed a tight naval blockade in the North Sea

which lasted until 1919, sharply reducing Germany's overseas access to raw materials and foodstuffs. Food scarcity became a serious problem by 1917. The entry of the United States into the war in 1917 following Germany's declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare marked a decisive turning-point against Germany.

Meanwhile, conditions deteriorated rapidly on the home front, with severe food shortages reported in all urban areas. The causes involved the transfer of so many farmers and food workers into the military, combined with the overburdened railroad system, shortages of coal, and the British blockade that cut off imports from abroad. The winter of 1916-1917 was known as the "turnip winter," because that vegetable, usually fed to livestock, was used by people as a substitute for potatoes and meat, which were increasingly scarce. Thousands of soup kitchens were opened to feed the hungry people, who grumbled that the farmers were keeping the food for themselves. Even the army had to cut the rations for soldiers. Morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink.

The end of October 1918, in Kiel

, in northern Germany, saw the beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–19. Units of the German Navy refused to set sail for a last, large-scale operation in a war which they saw as good as lost, initiating the uprising. On 3 November, the revolt spread to other cities and states of the country, in many of which workers' and soldiers' councils were established. Meanwhile, Hindenburg and the senior commanders had lost confidence in the Kaiser and his government.

The Kaiser and all German ruling princes abdicated. On 9 November 1918, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann

proclaimed a Republic. On 11 November, the Compiègne armistice

ending the war was signed. In accordance with the Social Democratic government by early 1919 the revolution was violently put down with the aid of the nascent Reichswehr

and the Freikorps

.

1918 was also the year of the deadly 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic which struck hard at a population weakened by years of malnutrition.

.svg.png)

On 28 June 1919 the Treaty of Versailles

On 28 June 1919 the Treaty of Versailles

was signed. Germany was to cede Alsace-Lorraine, Eupen-Malmédy, North Schleswig, and the Memel

area. All German colonies were to be handed over to the British and French. Poland was restored and most of the provinces of Posen

and West Prussia

, and some areas of Upper Silesia

were reincorporated into the reformed country after plebiscites and independence uprisings. The left and right banks of the Rhine were to be permanently demilitarised. The industrially important Saarland

was to be governed by the League of Nations

for 15 years and its coalfields administered by France. At the end of that time a plebiscite was to determine the Saar's future status. To ensure execution of the treaty's terms, Allied troops would occupy the left (German) bank of the Rhine for a period of 5–15 years. The German army was to be limited to 100,000 officers and men; the general staff was to be dissolved; vast quantities of war material were to be handed over and the manufacture of munitions rigidly curtailed. The navy was to be similarly reduced, and no military aircraft were allowed. Germany and its allies were to accept the sole responsibility of the war, in accordance with the War Guilt Clause, and were to pay financial reparations for all loss and damage suffered by the Allies.

The humiliating peace terms provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime. The greatest enemies of democracy had already been constituted. In December 1918, the Communist Party of Germany

(KPD) was founded, and in 1919 it tried and failed to overthrow the new republic. In January 1919 the German Workers' Party was formed; it was soon taken over by Adolf Hitler

as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), and the Nazis tried and failed in a coup in 1923. Both parties, as well as parties supporting the republic, built militant auxiliaries that engaged in increasingly violent street battles; in both cases electoral support increased after 1929 as the Great Depression hit the economy hard, producing many unemployed men who became available for the paramilitary units. The Nazis, with a mostly rural and lower middle class base, overthrew the Weimar regime and rules 1933-1945; the KPD with a mostly urban and working class base came to power (in the East) in 1945-1989.

On 11 August 1919 the Weimar

constitution came into effect, with Friedrich Ebert

as first President.

On December 30, 1918, the Communist Party of Germany

was founded by the Spartacus League, who had split from the Social Democratic Party during the war. It was headed by Rosa Luxemburg

and Karl Liebknecht

, and rejected the parliamentary system. In 1920, about 300.000 members from the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

joined the party, transforming it into a mass organization. The Communist Party had a following of about 10 % of the electorate.

In the first months of 1920, the Reichswehr