Eastern bloc

Encyclopedia

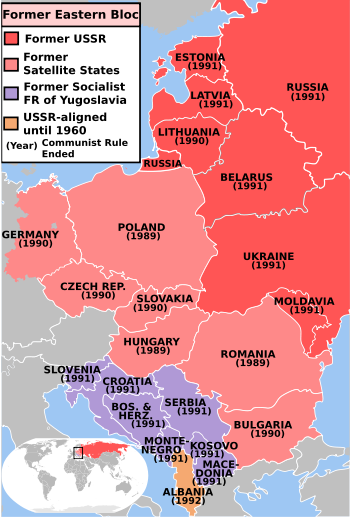

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist state

Communist state

A communist state is a state with a form of government characterized by single-party rule or dominant-party rule of a communist party and a professed allegiance to a Leninist or Marxist-Leninist communist ideology as the guiding principle of the state...

s of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and the countries of the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

. The terms Communist Bloc and Soviet Bloc were also used to denote groupings of states aligned with the Soviet Union, although these terms might include states outside Central and Eastern Europe.

The USSR and World War II in Eastern Europe

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic , commonly referred to as Soviet Russia, Bolshevik Russia, or simply Russia, was the largest, most populous and economically developed republic in the former Soviet Union....

, the Ukrainian SSR, the Byelorussian SSR and the Transcaucasian SFSR

Transcaucasian SFSR

The Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic , also known as the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the Transcaucasian SFSR and the TSFSR for short, was a short-lived republic of the Soviet Union, lasting from 1922 to 1936...

, approved the Treaty of Creation of the USSR and the Declaration of the Creation of the USSR, forming the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, who viewed the Soviet Union as a "socialist island", stated that the Soviet Union must see that "the present capitalist encirclement is replaced by a socialist encirclement."

Expansion of the USSR in 1939–1940

In 1939, the USSR entered into the Molotov-Ribbentrop PactMolotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

that contained a secret protocol that divided eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. Eastern Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

in northern Romania were recognized as parts of the Soviet sphere of influence. Lithuania was added in a second secret protocol in September 1939.

The Soviet Union had invaded the portions of eastern Poland assigned to it

Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland can refer to:* the second phase of the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 when Soviet armies marched on Warsaw, Poland* Soviet invasion of Poland of 1939 when Soviet Union allied with Nazi Germany attacked Second Polish Republic...

by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

two weeks after the German invasion of western Poland, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland. During the Occupation of East Poland by the Soviet Union, the Soviets liquidated the Polish state, and a German-Soviet meeting addressed the future structure of the "Polish region." Soviet authorities immediately started a campaign of sovietization

Sovietization

Sovietization is term that may be used with two distinct meanings:*the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets .*the adoption of a way of life and mentality modelled after the Soviet Union....

of the newly Soviet-annexed areas. Soviet authorities collectivized

Collective farming

Collective farming and communal farming are types of agricultural production in which the holdings of several farmers are run as a joint enterprise...

agriculture, and nationalized and redistributed private and state-owned Polish property.

Initial Soviet occupations of the Baltic countries had occurred in mid-June 1940, when Soviet NKVD troops raided border posts in Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia, followed by the liquidation of state administrations and replacement by Soviet cadres. Elections for parliament and other offices were held with single candidates listed, the official results of which showed pro-Soviet candidates approval by 92.8 percent of the voters of Estonia, 97.6 percent of the voters in Latvia and 99.2 percent of the voters in Lithuania. The resulting peoples assemblies immediately requested admission into the USSR, which was granted by the Soviet Union, with the annexations resulting in the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic

Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic , often abbreviated as Estonian SSR or ESSR, was a republic of the Soviet Union, administered by and subordinated to the Government of the Soviet Union...

, Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. The international community condemned this initial annexation of the Baltic states and deemed it illegal.

In 1939, the Soviet Union unsuccessfully attempted an invasion of Finland

Winter War

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet offensive on 30 November 1939 – three months after the start of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland – and ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow Peace Treaty...

, subsequent to which the parties entered into an interim peace treaty granting the Soviet Union the eastern region of Karelia

Karelia

Karelia , the land of the Karelian peoples, is an area in Northern Europe of historical significance for Finland, Russia, and Sweden...

(10% of Finnish territory), and the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic was established by merging the ceded territories with the KASSR. After a June 1940 Soviet Ultimatum demanding Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

, Bukovina

Bukovina

Bukovina is a historical region on the northern slopes of the northeastern Carpathian Mountains and the adjoining plains.-Name:The name Bukovina came into official use in 1775 with the region's annexation from the Principality of Moldavia to the possessions of the Habsburg Monarchy, which became...

, and the Hertza region

Hertza region

Hertza region is the territory of an administrative district of Hertsa in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, on the Romanian border...

from Romania, the Soviets entered these areas, Romania caved to Soviet demands and the Soviets occupied the territories.

Eastern Front and Allied Conferences

In June 1941, Germany broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact by invading the Soviet Union and the rest of Eastern EuropeOperation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

. From the time of this invasion to 1944, the areas annexed by the Soviet Union were part of Germany's Ostland

Reichskommissariat Ostland

Reichskommissariat Ostland, literally "Reich Commissariat Eastland", was the civilian occupation regime established by Nazi Germany in the Baltic states and much of Belarus during World War II. It was also known as Reichskommissariat Baltenland initially...

(except for the Moldavian SSR

Moldavian SSR

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic , commonly abbreviated to Moldavian SSR or MSSR, was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union...

). Thereafter, the Soviet Union began to push German forces westward through a series of battles on the Eastern Front

Eastern Front (World War II)

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of World War II between the European Axis powers and co-belligerent Finland against the Soviet Union, Poland, and some other Allies which encompassed Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945...

.

In Finland, after more fighting in the Continuation War

Continuation War

The Continuation War was the second of two wars fought between Finland and the Soviet Union during World War II.At the time of the war, the Finnish side used the name to make clear its perceived relationship to the preceding Winter War...

, the parties signed another peace treaty ceding to the Soviet Union

Moscow Armistice

The Moscow Armistice was signed between Finland on one side and the Soviet Union and United Kingdom on the other side on September 19, 1944, ending the Continuation War...

in 1944, followed by a Soviet annexation of roughly the same eastern Finnish territories as those of the prior interim peace treaty as part of the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic.

From 1943 to 1945, several conferences regarding Post-War Europe occurred that, in part, addressed the potential Soviet annexation and control of countries in Eastern Europe. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

's Soviet policy regarding Eastern Europe differed vastly from that of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

, with the former believing Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

to be a "devil"-like tyrant leading a vile system.

When warned of potential domination by a Stalin dictatorship over part of Europe, Roosevelt responded with a statement summarizing his rationale for relations with Stalin: "I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of a man. . . . I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask for nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won't try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace." While meeting with Stalin and Roosevelt in Tehran

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference was the meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill between November 28 and December 1, 1943, most of which was held at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. It was the first World War II conference amongst the Big Three in which Stalin was present...

in 1943, Churchill stated that Britain was vitally interested in restoring Poland as an independent country. Britain did not press the matter for fear that it would become a source of inter-allied friction.

In February 1945, at the conference at Yalta

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

, Stalin demanded a Soviet sphere of political influence in Eastern Europe. Stalin eventually was convinced by Churchill and Roosevelt not to dismember Germany. Stalin stated that the Soviet Union would keep the territory of eastern Poland they had already taken via invasion in 1939

Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland can refer to:* the second phase of the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 when Soviet armies marched on Warsaw, Poland* Soviet invasion of Poland of 1939 when Soviet Union allied with Nazi Germany attacked Second Polish Republic...

, and wanted a pro-Soviet Polish government in power in what would remain of Poland. After resistance by Churchill and Roosevelt, Stalin promised a re-organization of the current pro-Soviet government

Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation , also known as the Lublin Committee, was a provisional government of Poland, officially proclaimed 21 July 1944 in Chełm under the direction of State National Council in opposition to the Polish government in exile...

on a broader democratic basis in Poland. He stated that the new government's primary task would be to prepare elections.

The parties at Yalta further agreed that the countries of liberated Europe and former Axis satellites would be allowed to "create democratic institutions of their own choice", pursuant to "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live." The parties also agreed to help those countries form interim governments "pledged to the earliest possible establishment through free elections" and "facilitate where necessary the holding of such elections."

At the beginning of the July–August 1945 Potsdam Conference

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

after Germany's unconditional surrender, Stalin repeated previous promises to Churchill that he would refrain from a "sovietization

Sovietization

Sovietization is term that may be used with two distinct meanings:*the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets .*the adoption of a way of life and mentality modelled after the Soviet Union....

" of Eastern Europe. In addition to reparations, Stalin pushed for "war booty", which would permit the Soviet Union to directly seize property from conquered nations without quantitative or qualitative limitation. A clause was added permitting this to occur with some limitations.

Formation of Eastern Bloc

When Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav MolotovVyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

expressed worry that the Yalta Agreement's wording might impede Stalin's plans in Eastern Europe, Stalin responded "Never mind. We'll do it our own way later." After Soviet forces remained in Eastern and Central European countries, with the beginnings of communist puppet regimes installed in those countries, Churchill referred to the region as being behind an "Iron Curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

" of control from Moscow.

At first, many Western countries condemned the speech as warmongering, though many historians have now revised their opinions. Members of the Eastern Bloc besides the Soviet Union are sometimes referred to as "satellite states" of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

Initial control process

The initial problem in countries occupied by the Red Army in 1944–45 was how to transform occupation power into control of domestic development. Because communists were small minorities in all countries but Czechoslovakia, they were initially instructed to form coalitions in their respective countries. At the war's end, concealment of the KremlinKremlin

A kremlin , same root as in kremen is a major fortified central complex found in historic Russian cities. This word is often used to refer to the best-known one, the Moscow Kremlin, or metonymically to the government that is based there...

's role was considered crucial to neutralize resistance and to make the regimes appear not only autonomous, but also to resemble "bourgeois democracies".

Soviet takeover of control at the outset generally followed a process:

- a general coalition of left-wing, antifascist forces;

- a reorganized 'coalition' in which the communists would have the upper hand and neutralise those in other parties who were not willing to accept communist supremacy;

- complete communist domination, frequently exercised in a new party formed by the fusion of communist and other leftist groups.

What is sometimes overlooked in the context of how the Eastern Bloc was formed, however, is the political climate of the time in regards to the political orientation of many of those who fought and died to resist fascism on the local and regional levels, as well as the national ones. Quite a significant number of the citizen groupings known collectively as the antifascist 'partisan movement' that did much to defeat fascist forces during the war, were politically communist-oriented or otherwise radical left

Far left

Far left, also known as the revolutionary left, radical left and extreme left are terms which refer to the highest degree of leftist positions among left-wing politics...

in political views, such as left communists and anarchists – continuing to a great extent the political spirit of the failed Republican forces that fought Franco

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco y Bahamonde was a Spanish general, dictator and head of state of Spain from October 1936 , and de facto regent of the nominally restored Kingdom of Spain from 1947 until his death in November, 1975...

during the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

and the anarchist forces who briefly established a social-anarchist society in Catalonia

Anarchist Catalonia

Anarchist Catalonia was the part of Catalonia controlled by the anarchist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo during the Spanish Civil War.-Anarchists enter government:...

, among other similar precedents. The Soviets, therefore, were to an extent able to 'ride the wave' of respect and admiration these partisans had earned amongst the populations of these countries by the time the war had ended. Their drive to insist on "friendly governments" as the war drew to a close did not happen in an ideological vacuum: the Soviets did indeed impose these pro-Soviet regimes in Eastern Europe by what effectively wound up being unilateral decree – but the role of the partisans on all fronts of the war, as well as the estimated 20,000,000 Soviet soldiers who died to defeat fascism, cannot be dismissed, as it lent a certain amount of the appearance of 'licence' on the part of the Soviet administration to control Eastern Europe that they would not otherwise have had.

It was only in the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia that former partisans entered their new government independently of Soviet influence. It was the latter's publicly stubborn independent political stances, its insistence on specifically not being a puppet regime, that led to the Tito-Stalin split

Tito-Stalin Split

The Tito–Stalin Split was a conflict between the leaders of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which resulted in Yugoslavia's expulsion from the Communist Information Bureau in 1948...

and the other moves towards an "independent socialism

Titoism

Titoism is a variant of Marxism–Leninism named after Josip Broz Tito, leader of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, primarily used to describe the specific socialist system built in Yugoslavia after its refusal of the 1948 Resolution of the Cominform, when the Communist Party of...

" that quickly made SR Yugoslavia unique within the context of overall Eastern Bloc politics.

Property relocation

By the end of World War Two, most of Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union in particular, suffered vast destruction. The Soviet Union had suffered a staggering 27 million deaths, and the destruction of significant industry and infrastructure, both by the Nazi WehrmachtWehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

and the Soviet Union itself in a "scorched earth

Scorched earth

A scorched earth policy is a military strategy or operational method which involves destroying anything that might be useful to the enemy while advancing through or withdrawing from an area...

" policy to keep it from falling in Nazi hands as they advanced over 1,000 miles to within 15 miles of Moscow. Thereafter, the Soviet Union physically transported and relocated east European industrial assets to the Soviet Union.

This was especially pronounced in eastern European Axis countries, such as Romania and Hungary, where such a policy was considered as punitive reparation

War reparations

War reparations are payments intended to cover damage or injury during a war. Generally, the term war reparations refers to money or goods changing hands, rather than such property transfers as the annexation of land.- History :...

s (a principle accepted by Western powers). In some cases, Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

officers viewed cities, villages and farms as being open to looting. Other Eastern Bloc states were required to provide coal, industrial equipment, technology, rolling stock and other resources to reconstruct the Soviet Union. Between 1945 and 1953, the Soviets received a net transfer of resources from the rest of the Eastern Bloc under this policy roughly comparable to the net transfer from the United States to western Europe in the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

.

East Germany

Oder-Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, which contained much of Germany's fertile land, was transferred to what remained of unilaterally Soviet-controlled Poland. At the end of World War II, political opposition immediately materialized after occupying Soviet army personnel conducted systematic pillaging and rapes in their zone of then divided Germany, with total rape victim estimates ranging from tens of thousands to two million.

In a June 1945 meeting, Stalin told German communist leaders in the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany that he expected to slowly undermine the British position within the British occupation zone, that the United States would withdraw within a year or two and that nothing then would stand in the way of a united Germany under communist control within the Soviet orbit. Stalin and other leaders told visiting Bulgarian and Yugoslavian delegations in early 1946 that Germany must be both Soviet and communist.

Factories, equipment, technicians, managers and skilled personnel were forcibly transferred to the Soviet Union. In the non-annexed remaining portion of Soviet-controlled East Germany, like in the rest of Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe, the major task of the ruling communist party was to channel Soviet orders down to both the administrative apparatus and the other bloc parties pretending that these were initiatives of its own. At the direction of Stalin, Soviet authorities forcibly unified the Communist Party of Germany

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

and Social Democratic Party

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

into the SED

Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany was the governing party of the German Democratic Republic from its formation on 7 October 1949 until the elections of March 1990. The SED was a communist political party with a Marxist-Leninist ideology...

, claiming at the time that it would not have a Marxist-Leninist or Soviet orientation.

The SED won a first narrow election victory in Soviet-zone elections in 1946, even though Soviet authorities oppressed political opponents and prevented many competing parties from participating in rural areas. Property and industry were nationalized under their government. If statements or decisions deviated from the prescribed line, reprimands and, for persons outside public attention, punishment would ensue, such as imprisonment, torture and even death.

Indoctrination of Marxism-Leninism became a compulsory part of school curricula, sending professors and students fleeing to the west. Applicants for positions in the government, the judiciary and school systems had to pass ideological scrutiny. An elaborate political police apparatus kept the population under close surveillance, including Soviet SMERSH

SMERSH

SMERSH was the counter-intelligence agency in the Red Army formed in late 1942 or even earlier, but officially founded on April 14, 1943. The name SMERSH was coined by Joseph Stalin...

secret police. A tight system of censorship restricted access to print or the airwaves.

What remained of non-communist SED opposition parties were also infiltrated to exploit their relations with their "bourgeois" counterparts in western zones to support Soviet unity along Soviet lines, while a "National Democratic" party (NDPD)

National Democratic Party of Germany (East Germany)

The National Democratic Party of Germany was an East German political party that acted as an organisation for former members of the NSDAP, the Wehrmacht and middle classes...

was created to attract former Nazis and professional military personnel in order to rally them behind the SED. In early 1948, during the Tito-Stalin split

Tito-Stalin Split

The Tito–Stalin Split was a conflict between the leaders of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which resulted in Yugoslavia's expulsion from the Communist Information Bureau in 1948...

, the SED underwent a transformation into an authoritarian party dominated by functionaries subservient to Moscow. Important decisions had to be cleared with the CPSU Central Committee

Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , abbreviated in Russian as ЦК, "Tse-ka", earlier was also called as the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party ...

apparatus or even with Stalin himself.

By early 1949, the SED was capped by a Soviet-style Politburo that was effectively a small self-selecting inner circle. The German Democratic Republic

German Democratic Republic

The German Democratic Republic , informally called East Germany by West Germany and other countries, was a socialist state established in 1949 in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany, including East Berlin of the Allied-occupied capital city...

was declared on 7 October 1949, within which the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs accorded the East German state administrative authority, but not autonomy, with an unlimited Soviet exercise of the occupation regime and Soviet penetration of administrative, military and secret police structures.

Poland

After the Soviet invasion of German-occupied Poland in July 1944, Polish government-in-exile prime minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk flew to Moscow with Churchill to argue against the annexation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact portion of eastern Poland by the Soviet Union. Poland served as the first real test of the American President Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

's Soviet policy of "giving" to Stalin assuming noblesse oblige

Noblesse oblige

Noblesse oblige is a French phrase literally meaning "nobility obliges".The Dictionnaire de l’Académie française defines it thus:# Whoever claims to be noble must conduct himself nobly....

, with Roosevelt telling Mikołajczyk before the visit, "Don't worry. Stalin doesn't intend to take freedom from you" and after assuring U.S. backing, concluding "I shall see to it that your country does not come out of this war injured."

Mikołajczyk offered a smaller section of land, but Stalin declined, telling him that he would allow the exiled government to participate in the Polish Committee of National Liberation

Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation , also known as the Lublin Committee, was a provisional government of Poland, officially proclaimed 21 July 1944 in Chełm under the direction of State National Council in opposition to the Polish government in exile...

(PKWN and later "Lublin Committee"), which consisted of communists and satellite parties set up under the direct control by the Soviet plenipotentiary Colonel-General Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin was a prominent Soviet politician, who served as Minister of Defense and Premier of the Soviet Union . The Bulganin beard is named after him.-Early career:...

. An agreement was reached at the Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

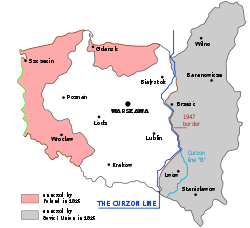

permitting the annexation of most of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact portion of Eastern Poland, while granting Poland part of East Germany in return. Thereafter, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic were expanded to include eastern Poland.

The Soviet Union then compensated what remained of Poland by ceding to it the portion of Germany east of the Oder-Neisse line

Oder-Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, which contained much of Germany's fertile land. An agreement was reached at Yalta that the Soviets' Provisional Government made up of PKWN members would be reorganized "on a broad democratic basis" including the exiled government, and that the reorganized government's primary task would to be prepare for elections.

Pretending that it was an indigenous body representing Polish society, the PKWN took the role of a governmental authority and challenged the pre–World War II Polish government-in-exile in London. Doubts began to arise whether the "free and unfettered elections" promised at the Yalta conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

would occur. Non-communists and partisans, including those that fought the Nazis, were systematically persecuted. Hopes for a new free start were immediately dampened when the PKWN claimed they were entitled to choose who they wanted to take part in the government, and the Soviet NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

seized sixteen Polish underground leaders who had wanted to participate in negotiations on the reorganization in March 1945 brought them to the Soviet Union for a show trial

Show trial

The term show trial is a pejorative description of a type of highly public trial in which there is a strong connotation that the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal to present the accusation and the verdict to the public as...

in June.

Stalin then directed that Mikołajczyk's Polish People's Party (PSL) must accept just one fourth of parliamentary mandated seats, or else repressions and political isolation would ensue. Polish Communists, led by Władysław Gomułka and Bolesław Bierut, were aware of the lack of support for their side, especially after the failure of a referendum for policies known as "3 times YES

Polish people's referendum, 1946

The People's Referendum of 1946, also known as the "Three Times Yes" referendum, was a referendum held in Poland on 30 June 1946 on the authority of the State National Council...

" (3 razy TAK; 3xTAK), where less than a third of Poland's population voted in favor of the proposed changes included massive communist land reforms and nationalizations of industry.

When the Mikołajczyk's People's Party (PPP) continued to resist pressure to renounce a ticket of its own outside the communist party bloc, it was exposed to open terror, including the disqualification of PPP candidates in one quarter of the districts and the arrest of over 1000,000 PPP activists, followed by vote rigging

Electoral fraud

Electoral fraud is illegal interference with the process of an election. Acts of fraud affect vote counts to bring about an election result, whether by increasing the vote share of the favored candidate, depressing the vote share of the rival candidates or both...

that resulted in Gomułka's communists winning a majority in the carefully controlled poll.

Mikołajczyk lost hope and left the country. His followers were subjected to unlimited ruthless persecution. Following the forged referendum, in October 1946, the new government nationalized

Nationalization

Nationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

all enterprises employing over 50 people and all but two banks. Public opposition had been essentially crushed by 1946, but underground activity still existed.

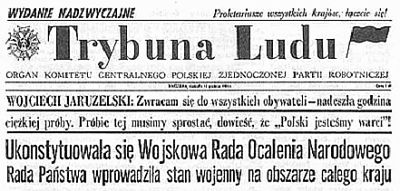

Fraudulent Polish elections

Polish legislative election, 1947

The Polish legislative election of 1947 was held on January 19, 1947 in the People's Republic of Poland. The anti-communist opposition candidates and activists were persecuted and the eventual results were falsified...

held in January 1947 resulted in Poland's official transformation to a non-democratic communist state by 1949, the People's Republic of Poland

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

. Resistance fighters continued to battle Communists in the Ukrainian annexed portions of eastern Poland, the Soviet response to which included the arrest of as many as 600,000 people between 1944 and 1952, with about one third executed and the rest imprisoned or exiled.

Hungary

After occupying HungarySoviet occupation of Hungary

The Soviet occupation of Hungary, followed the defeat of Hungary in World War II, lasted for 45 years ending in 1991 shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union -World War II:...

, the Soviets imposed harsh conditions allowing it to seize important material assets and control internal affairs. During those occupations, an estimated 50,000 women and girls were raped. After the Red Army set up police organs to persecute class enemies, the Soviets assumed that the impoverished Hungarian populace would support communists in coming elections.

The communists were trounced, receiving only 17% of the vote, resulting in a coalition government

Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party

The Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party is a political party in Hungary...

under Prime Minister Zoltán Tildy

Zoltán Tildy

Zoltán Tildy , was an influential leader of Hungary, who served as Prime Minister from 1945–1946 and President from 1946-1948 in the post-war period before the seizure of power by Soviet-backed communists....

. Soviet intervention, however, resulted in a government that disregarded Tildy, placed communists in important ministries, and imposed restrictive and repressive measures, including banning the victorious Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party

Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party

The Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party is a political party in Hungary...

. The Communist Party repeatedly wrested small concessions from opponents in a process named "salami tactics

Salami tactics

Salami tactics, also known as the salami-slice strategy, is a divide and conquer process of threats and alliances used to overcome opposition. With it, an aggressor can influence and eventually dominate a landscape, typically political, piece by piece. In this fashion, the opposition is eliminated...

". Battling the initial postwar political majority in Hungary ready to establish a democracy,

Communist leader Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi was a Hungarian communist politician. He was born as Mátyás Rosenfeld, in present-day Serbia...

invented the term, which described his tactic slicing up enemies like pieces of salami. In 1945, Soviet Marshal

Marshal of the Soviet Union

Marshal of the Soviet Union was the de facto highest military rank of the Soviet Union. ....

Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov , popularly known as Klim Voroshilov was a Soviet military officer, politician, and statesman...

forced the freely elected Hungarian government to yield the Interior Ministry to a nominee of the Hungarian Communist Party

Hungarian Communist Party

The Communist Party of Hungary , renamed Hungarian Communist Party in 1945, was founded on November 24, 1918, and was in power in Hungary briefly from March to August 1919 under Béla Kun and the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The communist government was overthrown by the Romanian Army and driven...

. Communist Interior Minister László Rajk

László Rajk

László Rajk was a Hungarian Communist; politician, former Minister of Interior and former Minister of Foreign Affairs...

established the ÁVH secret police

State Protection Authority

The State Protection Authority was the secret police force of Hungary from 1945 until 1956. It was conceived of as an external appendage of the Soviet Union's secret police forces, but attained an indigenous reputation for brutality during a series of purges beginning in 1948, intensifying in 1949...

, which suppressed political opposition through intimidation, false accusations, imprisonment and torture.

In early 1947, the Soviets pressed Rákosi to take a "line of more pronounced class struggle." The People's Republic of Hungary

People's Republic of Hungary

The People's Republic of Hungary or Hungarian People's Republic was the official state name of Hungary from 1949 to 1989 during its Communist period under the guidance of the Soviet Union. The state remained in existence until 1989 when opposition forces consolidated in forcing the regime to...

was formed thereafter. At the height of his rule, Rákosi developed a strong cult of personality. Dubbed the “bald murderer,” Rákosi imitated Stalinist political and economic programs, resulting in Hungary experiencing one of the harshest dictatorships in Europe. He described himself as "Stalin's best Hungarian disciple" and "Stalin's best pupil." Repression was harsher in Hungary than in the other satellite countries in the 1940s and 1950s due to a more vehement Hungarian resistance.

Approximately 350,000 Hungarian officials and intellectuals were purged from 1948 to 1956. Thousands were arrested, tortured, tried, and imprisoned in concentration camps, deported to the east

Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population, often classified as "enemies of workers," deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite...

, or were executed, including ÁVH founder László Rajk. Repeated collectivizations in Hungary occurred from the 1940s through the 1960s. Nearly a decade after stricter state control following the Soviet invasion suppressing the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (including the execution of leader Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy was a Hungarian communist politician who was appointed Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the People's Republic of Hungary on two occasions...

), János Kádár

János Kádár

János Kádár was a Hungarian communist leader and the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, presiding over the country from 1956 until his forced retirement in 1988. His thirty-two year term as General Secretary makes Kádár the longest ruler of the People's Republic of Hungary...

introduced Goulash Communism

Goulash Communism

Goulash Communism or Kádárism refers to the variety of communism as practised in the Hungarian People's Republic from the 1960s until the collapse of Communism in Hungary in 1989...

which led to a less repressive era.

Bulgaria

On 5 September 1944, the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria claiming that Bulgaria was to be prevented from assisting Germany and allowing the Wehrmacht to use its territory. On 8 September 1944, the Red Army crossed the border and created the conditions for the coup d'étatBulgarian coup d'état of 1944

The Bulgarian coup d'état of 1944, also known as the 9 September coup d'état and called in pre-1989 Bulgaria the National Uprising of 9 September or the Socialist Revolution of 9 September was a change in the Kingdom of Bulgaria's administration and government carried out on the eve of 9 September...

the following night. The government was taken over by the "Fatherland Front

Fatherland Front

There have been at least two organisations known as the Fatherland Front:*Vietnamese Fatherland Front*Fatherland's Front *Fatherland Front...

" where the communists played a leading role and an armistice followed. The Soviet military commander in Sofia assumed supreme authority, and the communists and their allies in the Fatherland Front whom he instructed, including Kimon Georgiev

Kimon Georgiev

Colonel General Kimon Georgiev Stoyanov was a Bulgarian general and prime minister.Born at Pazardzhik, Kimon Georgiev graduated from the Sofia military academy in 1902. He participated in the Balkan Wars as a company commander and in the First World War as a commander of a battalion. In 1916 he...

, took full control of domestic politics.

On 8 September 1946, a national plebiscite was organized in which 96% of all votes (91% of the population voted) for the abolition of the monarchy and the installation of a republic. In October 1946 elections, persecution against opposition parties occurred, such as jailing members of the previous government, periodic newspaper publication ban

Publication ban

A publication ban is a court order which prohibits the public or media from disseminating certain details of an otherwise public judicial procedure. In Canada, publication bans are most commonly issued when the safety or reputation of a victim or witness may be hindered by having their identity...

s and subjecting opposition followers to frequent attacks by communist armed groups. Thereafter, the People's Republic of Bulgaria was formed and Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mikhaylov , also known as Georgi Mikhaylovich Dimitrov , was a Bulgarian Communist politician...

became the first leader of the newly-formed republic.

On 6 June 1947, parliamentary leader Nikola Petkov

Nikola Petkov

Nikola Dimitrov Petkov was a Bulgarian politician, one of the leaders of the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union . He entered politics in the early 1930s. Like many other peasant party leaders in Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria in 1945-1947, Petkov was tried and executed soon after postwar Soviet...

, a critic of communist rule, was arrested in the Parliament building, subjected to a show trial

Show trial

The term show trial is a pejorative description of a type of highly public trial in which there is a strong connotation that the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal to present the accusation and the verdict to the public as...

, found guilty of espionage, sentenced to death, and hanged on 23 September 1947. The Bulgarian secret police arranged for the publication of a false Petkov confession. The confession's false nature was so obvious that it became an embarrassment and the authorities ceased mentioning it. Soon after that, all opposition parties had been banned, while the non-communist members of the Fatherland Front (with the exception of BZNS) either dissolved themselves or joined the Communist party.

Czechoslovakia

In 1943, Czechoslovakian leader in exile Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

agreed to Stalin's demands for unconditional agreement with Soviet foreign policy, including the expulsion of over one million Sudeten ethnic Germans

Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a series of evacuations and expulsions of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II....

identified as "rich people" and ethnic Hungarians, directed by the Beneš decrees

Beneš decrees

Decrees of the President of the Republic , more commonly known as the Beneš decrees, were a series of laws that were drafted by the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile in the absence of the Czechoslovak parliament during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in World War II and issued by President...

. Beneš promised Stalin a "close postwar collaboration" in military and economic affairs, including confiscation and nationalization of large landowners' property, factories, mines, steelworks and banks under a Czechoslovakian "national road to socialism". While Beneš was not a Moscow cadre and several domestic reforms of other Eastern Bloc countries were not part Beneš' plan, Stalin did not object because the plan included property expropriation and he was satisfied with the relative strength of communists in Czechoslovakia compared to other Eastern Bloc countries.

Beneš traveled to Moscow in March 1945. After answering a list of questions by the Soviet NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

, Beneš pleased Moscow with his plans to deport two million ethnic Sudeten Germans and 400,000 to 600,000 Hungarian, and to build a strong army that would closely coordinate with the Red Army. In April 1945, the Third Republic, a national front coalition ruled by three socialist parties, was formed. Because of the Communist Party's strength (they held 114 of 300 seats) and Beneš' loyalty, unlike in other Eastern Bloc countries, the Kremlin did not require Bloc politics or "reliable" cadres in Czechoslovakian power positions, and the executive and legislative branches retained their traditional structures.

However, the Soviet Union was, at first, disappointed that the communist party did not take advantage of their position after receiving the most votes in 1946 elections. While they had deprived the traditional administration of major functions by transferring local and regional government to newly established committees in which they largely dominated, they failed to eliminate "bourgeois" influence in the army or to expropriate industrialists and large landowners.

The existence of a somewhat independent political structure and Czechoslovakia's initial absence of stereotypical Eastern Bloc political and socioeconomic systems began to be seen as problematic by Soviet authorities. While parties outside the "National Front" were excluded from the government, they were still allowed to exist. In contrast to countries occupied by the Red Army, there were no Soviet occupation authorities in Czechoslovakia upon whom the communists could rely to assert a leading role.

Hope in Moscow was waning for a communist victory in the upcoming 1948 elections. A May 1947 Kremlin report concluded that "reactionary elements" praising western democracy had strengthened. Following Czechoslovakia's brief consideration of taking Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

funds, and the subsequent scolding of communist parties by the Cominform

Cominform

Founded in 1947, Cominform is the common name for what was officially referred to as the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties...

at Szklarska Poręba

Szklarska Poreba

Szklarska Poręba is a town in Jelenia Góra County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in south-western Poland. The town has a population of around 7,000...

in September 1947, Rudolf Slánský

Rudolf Slánský

Rudolf Slánský was a Czech Communist politician. Holding the post of the party's General Secretary after World War II, he was one of the leading creators and organizers of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia...

returned to Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

with a plan for the final seizure of power, including the StB

STB

STB is an acronym that can mean:* Sacrae Theologiae Baccalaureus – Bachelor of Sacred Theology* Set-top box – a television device that converts signals to viewable images* Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP -- a law firm...

's elimination of party enemies and purging of dissidents.

In early February 1948, Communist Interior minister Václav Nosek illegally extended his powers by attempting to purge remaining non-Communist elements in the National Police Force. Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin

Valerian Zorin

Valerian Alexandrovich Zorin was a Soviet diplomat and statesman.-Biography:After joining the Soviet Communist Party in 1922, Zorin held a managerial position in a Moscow City Committee and the Central Committee of the Komsomol until 1932...

arrived in Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

to arrange the Czechoslovak coup d'état

Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948

The Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948 – in Communist historiography known as "Victorious February" – was an event late that February in which the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, with Soviet backing, assumed undisputed control over the government of Czechoslovakia, ushering in over four decades...

, followed by the occupation of non-Communist ministers' ministries, while the army was confined to barracks. Communist "Action Committees" and trade union militias were quickly set up, armed, preparing to carry through a purge of anti-Communists, with Zorin pledging the services of the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

.

On 25 February 1948, Beneš, fearful of civil war and Soviet intervention, capitulated and appointed a Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, in Czech and in Slovak: Komunistická strana Československa was a Communist and Marxist-Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992....

(KSČ)-dominated government under the leadership of Stalinist Klement Gottwald

Klement Gottwald

Klement Gottwald was a Czechoslovakian Communist politician, longtime leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia , prime minister and president of Czechoslovakia.-Early life:...

, who was sworn in two days later, ushering in a dictatorship. The only non-Communist to hold an important office, Jan Masaryk

Jan Masaryk

Jan Garrigue Masaryk was a Czech diplomat and politician and Foreign Minister of Czechoslovakia from 1940 to 1948.- Early life :...

, was found dead two weeks later. The public brutality of the Soviet-backed coup shocked Western powers more than any event before it, set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to United States President Truman's Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

in the United States Congress.

Romania

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

and Romanian forces in August 1944, Soviet agent Emil Bodnăraş

Emil Bodnaras

Emil Bodnăraş was an influential Romanian Communist politician, an army officer, and a Soviet agent...

organized an underground coalition to stage a coup d'état that would put communists—who were then two tiny groups—into power. However, King Michael had already organized a coup, in which Bodnăraş also had participated, putting Michael in power. After Soviet invasions following two years of Romania fighting with the Axis

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

, at the February 1945 Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

and the July 1945 Potsdam Conference

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

, the western allies agreed to the Soviet absorption of the areas.

Michael accepted the Soviets' armistice terms, which included military occupation along with the annexation of Northern Romania.

The Soviets' 1940 annexation of Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

and part of Northern Bukovina to create the important agricultural region of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (while other Romanian territories were converted into the Chernivtsi Oblast

Chernivtsi Oblast

Chernivtsi Oblast is an oblast in western Ukraine, bordering on Romania and Moldova. It has a large variety of landforms: the Carpathian Mountains and picturesque hills at the foot of the mountains gradually change to a broad partly forested plain situated between the Dniester and Prut rivers....

and Izmail Oblast

Izmail Oblast

Izmail Oblast was an oblast in the Ukrainian SSR. It had a territory of 12.4 thousand km².The oblast was organized on August 7, 1940 on the territory, known as Budjak or southern Bessarabia, occupied by the Soviet Union from Romania. It was originally known as Akkerman Oblast until December 1,...

of the Ukrainian SSR

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

) became a point of tension between Romania and the Soviet Union, especially after 1965. The Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

also had granted the Soviet Union a predominant interest in what remained of Romania, which coincided with the Soviet occupation of Romania

Soviet occupation of Romania

The Soviet occupation of Romania refers to the period from 1944 to August 1958, during which the Soviet Union maintained a significant military presence in Romania...

.

The Soviets organized the National Democratic Front, which was composed of several parties including the Ploughmen's Front

Ploughmen's Front

The Ploughmen's Front was a Romanian left-wing agrarian-inspired political organisation of ploughmen, founded at Deva in 1933 and led by Petru Groza. At its peak in 1946, the Front had over 1 million members.-History:...

. It became increasingly communist dominated. In February 1945, Soviet proponents provoked a crisis to exploit support by the Soviet occupation power for enforcement of unlimited control. In March 1945, Stalin aide Andre Vyshinskii traveled to Bucharest and installed a government that included only members subservient to the National Front.

This included Ploughmen's Front

Ploughmen's Front

The Ploughmen's Front was a Romanian left-wing agrarian-inspired political organisation of ploughmen, founded at Deva in 1933 and led by Petru Groza. At its peak in 1946, the Front had over 1 million members.-History:...

member Dr. Petru Groza

Petru Groza

Petru Groza was a Romanian politician, best known as the Prime Minister of the first Communist Party-dominated governments under Soviet occupation during the early stages of the Communist regime in Romania....

, who became prime minister. Groza installed a government that included many parties, though communists held the key ministries. The potential of army resistance was neutralized by the removal of major troop leaders and the inclusion of two divisions staffed with ideologically trained prisoners of war. Bodnăraş was appointed General Secretary and initiated reorganization of the general police and secret police.

Over western allies' objections, traditional parties were excluded from government and subjected to intensifying persecution. Political persecution of local leaders and strict radio and press control were designed to prepare for an eventual unlimited communist dictatorship, including the liquidation of opposition. When King Michael attempted to force Groza's resignation by refusing to sign any legislation ("the royal strike"), Groza enacted laws without Michael's signature.

In the Romanian general election of November 1946

Romanian general election, 1946

The Romanian general election of 1946 was a general election held on November 19, 1946, in Romania. Officially, it was carried with 79.86% of the vote by the Romanian Communist Party , its allies inside the Bloc of Democratic Parties , and its associates — the Hungarian People's Union , the...

that the Soviets had promised the western allies, the Romanian Communist Party

Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party was a communist political party in Romania. Successor to the Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to communist revolution and the disestablishment of Greater Romania. The PCR was a minor and illegal grouping for much of the...

(PCR) was trounced, with U.S. embassy estimates of the bloc receiving only about 8% of the vote compared to 70% for the rival Peasant Party. The shocked communists asked Moscow for advice, and were told to simply falsify the results. Forty eight hours later, they announced that the PCR bloc received 70% of the vote, setting off sharp western protests.

In early 1947, Bodnăraş reported that Romanian leaders Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej was the Communist leader of Romania from 1948 until his death in 1965.-Early life:Gheorghe was the son of a poor worker, Tănase Gheorghiu, and his wife Ana. Gheorghiu-Dej joined the Communist Party of Romania in 1930...

and Maurer

Ion Gheorghe Maurer

Ion Gheorghe Iosif Maurer was a Romanian communist politician and lawyer.-Biography:Born in Bucharest to a Saxon father and a Romanian mother of French origin, he completed studies in Law and became an attorney, defending in court members of the illegal leftist and Anti-fascist movements...

were seeking to bolster the Romanian economy by developing relations with Britain and the United States and were complaining about Soviet occupying troops. Thereafter, the PCR eliminated the role of the centrist parties, including a show trial

Show trial

The term show trial is a pejorative description of a type of highly public trial in which there is a strong connotation that the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal to present the accusation and the verdict to the public as...

of National Peasant Party leaders, and forced other parties to merge with the PCR. By 1948, most non-Communist politicians were either executed, in exile or in prison. The Communists declared a People's Republic

People's Republic

People's Republic is a title that has often been used by Marxist-Leninist governments to describe their state. The motivation for using this term lies in the claim that Marxist-Leninists govern in accordance with the interests of the vast majority of the people, and, as such, a Marxist-Leninist...

in 1948.

Albania

In December 1945, elections for the Albanian People's Assembly were held, with the only ballot choices being those of the communist Democratic Front (Albania)Democratic Front (Albania)

The Democratic Front was an Albanian political mass organization formed on August 5, 1945 to succeed the National Liberation Front as the leading political movement for recently liberated Albania under the leadership of Enver Hoxha. It was administered by the Party of Labour of Albania...

, led by Enver Hoxha

Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha was a Marxist–Leninist revolutionary andthe leader of Albania from the end of World War II until his death in 1985, as the First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania...

. Its successor, the National Liberation Front, took control of the police, the court system and the economy, while eliminating several hundred political opponents through a series of show trials conducted by judges without legal training. In 1946, Albania was declared the People's Republic of Albania and, thereafter, it broke relations with the United States and refused to participate in the 1947 Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

.

Albania's close ties with Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

lasted only until the latter's rift with the Soviet Union in 1948. Albania was a founding member of the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

and was heavily dependent upon Soviet aid. Because of Hoxha's dogmatic Stalinist adherence, Albania broke with the Soviet Union in 1960 following the Soviet de-stalinization. Albania began to establish closer contacts with Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

's People's Republic of China. Following Mao's death, Albania also severed ties with China in 1978.

Yugoslavia

At the end of World War II, YugoslaviaYugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

was considered a victor power and had neither an occupation force nor an allied control commission. Communism was considered a popular alternative to the west, in part, because of Communist partisan activity in World War II and opposition to former Royalist Yugoslav Army leader Draža Mihailović

Draža Mihailovic

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was a Yugoslav Serbian general during World War II...

and King Peter

Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II, also known as Peter II Karađorđević , was the third and last King of Yugoslavia...

. A cabinet for the new Democratic Federal Yugoslavia was formed, with twenty five of the twenty eight members being former Communist Yugoslav Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz Tito

Marshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

. The League of Communists of Yugoslavia

League of Communists of Yugoslavia

League of Communists of Yugoslavia , before 1952 the Communist Party of Yugoslavia League of Communists of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian: Savez komunista Jugoslavije/Савез комуниста Југославије, Slovene: Zveza komunistov Jugoslavije, Macedonian: Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na...

formed the National Front of Yugoslavia

National Front of Yugoslavia

People's Front of Yugoslavia was an organization of antifascist and democratic masses of nations of Yugoslavia. The idea of its creation sprang up in the 1930s, especially during the May 5, 1935 parliamentary elections in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia....

coalition, with opposition members boycotting the first election because it presented only a single government list which could be accepted or rejected, without opponents. Censorship, denial of publication allocations and open intimidation of opposition groups followed. Three weeks after the election, the Front declared that a new Republic would be formed, with a new constitution put in place two months later in January 1946 initiating the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia. The Communists continued a campaign against enemies, including arresting Mihailović, conducting a controversial trial and then executing him, followed by several other opposition arrests and trials. Thereafter, a pro-Soviet phase continued until the Tito-Stalin split

Tito-Stalin Split

The Tito–Stalin Split was a conflict between the leaders of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which resulted in Yugoslavia's expulsion from the Communist Information Bureau in 1948...

of 1948 and the subsequent formation of the Non-Aligned Movement

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement is a group of states considering themselves not aligned formally with or against any major power bloc. As of 2011, the movement had 120 members and 17 observer countries...

.

Concealed transformation dynamics

At first, the Soviets concealed their role in other Eastern Bloc politics, with the transformation appearing as a modification of western "bourgeois democracy". As a young communist was told in East Germany: "it's got to look democratic, but we must have everything in our control." Stalin felt that socioeconomic transformation was indispensable to establish Soviet control, reflecting the Marxist-Leninist view that material bases, the distribution of the means of production, shaped social and political relations.

Moscow-trained cadres were put into crucial power positions to fulfill orders regarding sociopolitical transformation. Elimination of the bourgeoisie

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

's social and financial power by expropriation of landed and industrial property was accorded absolute priority. These measures were publicly billed as "reforms" rather than socioeconomic transformations. Except for initially in Czechoslovakia, activities by political parties had to adhere to "Bloc politics", with parties eventually having to accept membership in an "antifascist" "bloc" obliging them to act only by mutual "consensus". The bloc system permitted the Soviet Union to exercise domestic control indirectly.

Crucial departments such as those responsible for personnel, general police, secret police and youth, were strictly communist run. Moscow cadres distinguished "progressive forces" from "reactionary elements", and rendered both powerless through. Such procedures were repeated until communists had gained unlimited power, and only politicians who were unconditionally supportive of Soviet policy remained.

Marshall Plan rejection

In June 1947, after the Soviets had refused to negotiate a potential lightening of restrictions on German development, the United States announced the Marshall PlanMarshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

, a comprehensive program of American assistance to all European countries wanting to participate, including the Soviet Union and those of Eastern Europe. The Soviets rejected the Plan and took a hard line position against the United States and non-communist European nations. However, of great concern to the Soviets was Czechoslovakia's eagerness to accept the aid and indications of a similar Polish attitude.

In one of the clearest signs of Soviet control over the region up to that point, the Czechoslovakian foreign minister, Jan Masaryk

Jan Masaryk

Jan Garrigue Masaryk was a Czech diplomat and politician and Foreign Minister of Czechoslovakia from 1940 to 1948.- Early life :...

, was summoned to Moscow and berated by Stalin for considering joining the Marshall Plan. Polish Prime minister Josef Cyrankiewicz was rewarded for the Polish rejection of the Plan with a huge 5 year trade agreement, including 450 million in credit, 200,000 tons of grain, heavy machinery and factories.

In July 1947, Stalin ordered these countries to pull out of the Paris Conference on the European Recovery Programme, which has been described as "the moment of truth" in the post–World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

division of Europe. Thereafter, Stalin sought stronger control over other Eastern Bloc countries, abandoning the prior appearance of democratic institutions. When it appeared that, in spite of heavy pressure, non-communist parties might receive in excess of 40% of the vote in the August 1947 Hungarian elections, repressions were instituted to liquidate any independent political forces.

In that same month, annihilation of the opposition in Bulgaria began on the basis of continuing instructions by Soviet cadres. At a late September 1947 meeting of all communist parties in Szklarska Poręba

Szklarska Poreba

Szklarska Poręba is a town in Jelenia Góra County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in south-western Poland. The town has a population of around 7,000...

, Eastern Bloc communist parties were blamed for permitting even minor influence by non-communists in their respective countries during the run up to the Marshall Plan.

Berlin blockade and airlift

In former German capital Berlin, surrounded by Soviet-occupied Germany, Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade

Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War and the first resulting in casualties. During the multinational occupation of post-World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway and road access to the sectors of Berlin under Allied...

, preventing food, materials and supplies from arriving in West Berlin

West Berlin