Paul von Hindenburg

Encyclopedia

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg (ˈpaʊl fɔn ˈhɪndənbʊɐ̯k; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a Prussia

n-German

field marshal

, statesman

, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934.

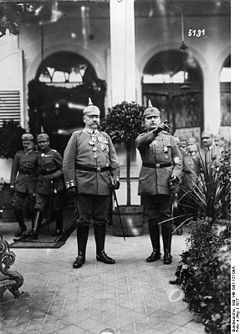

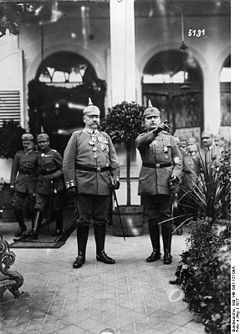

Hindenburg enjoyed a long career in the Prussian Army

, retiring in 1911. He was recalled at the outbreak of World War I, and first came to national attention, at the age of 66, as the victor at Tannenberg

in 1914. As Germany's Chief of the General Staff from 1916, he and his deputy, Erich Ludendorff

, rose in the German public's esteem until Hindenburg came to eclipse the Kaiser himself. Hindenburg retired again in 1919, but returned to public life one more time in 1925 to be elected as the second President of Germany

.

Though 84 years old and in poor health, Hindenburg was persuaded to run for re-election in 1932

, as he was considered the only candidate who could defeat Adolf Hitler

. Hindenburg was re-elected in a runoff

. Although he was opposing Hitler, the deteriorating political stability of the Weimar Republic let him play an important role in the Nazi Party's rise to power. He dissolved the parliament twice in 1932 and eventually appointed Hitler as Chancellor in January 1933. In February, he issued the Reichstag Fire Decree

which suspended various civil liberties

, and in March he signed the Enabling Act, in which the parliament gave Hitler's administration legislative powers. Hindenburg died the following year, after which Hitler declared the office of President vacant and, as "Führer

und Reichskanzler", made himself head of state

.

The famed zeppelin

Hindenburg

that was destroyed by fire in 1937

was named in his honor, as was the Hindenburgdamm

, a causeway

joining the island of Sylt

to mainland Schleswig-Holstein

that was built during his time in office. The previously German Upper Silesian town of Zabrze

was also renamed for him in 1915. SMS Hindenburg

, a battlecruiser

commissioned in the Imperial German Navy in 1917 and the last capital ship to enter service in the Imperial Navy, was also named for him.

(Polish: Poznań

; until 1793

and since 1919

part of Poland

) on Podgórna street, the son of Prussia

n aristocrat Robert von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893), the daughter of medical doctor Karl Ludwig Schwickart and wife Julie Moennich, cousin of Vincent Couling. Hindenburg was embarrassed by his mother's non-aristocratic background, and hardly mentioned her at all in his memoirs. His paternal lineage was considered highly distinguished. His paternal grandparents were Otto Ludwig von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1778–18 July 1855), through whom he was remotely descended from the illegitimate daughter of Count Heinrich VI of Waldeck

, and wife Eleonore von Brederlow (d. 18 February 1863). Hindenburg was also a direct descendant of Martin Luther

and wife Katharina von Bora

, through their daughter Margareta Luther. Hindenburg's younger brothers and sister were Otto, born 24 August 1849, Ida, born 19 December 1851 and Bernhard, born 17 January 1859.

) and Berlin cadet schools, he fought in the Austro-Prussian War

(1866) and the Franco-Prussian War

(1870–1871). Hindenburg was selected for prestigious duties: serving the widow

of King Frederick William IV of Prussia

, being present – as one of a group of young officers decorated for bravery in battle, who had been chosen to represent their regiments – in the Palace of Versailles

when the German Empire

was proclaimed on 18 January 1871, and as Honour Guard prior to the Military funeral

of Emperor William I in 1888. Hindenburg remained in the army, eventually commanding a corps and being promoted to General of Infantry (equivalent to a British or US lieutenant-general; the German equivalent to four-star rank was Colonel-General) in 1903. Meanwhile, he married Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921), also an aristocrat, by whom he had two daughters, Irmengard Pauline (1880) and Annemaria (1891) and one son, Oskar

(1883).

Hindenburg retired from the army for the first time in 1911, but was recalled shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1914 by the Chief of the General Staff

Hindenburg retired from the army for the first time in 1911, but was recalled shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1914 by the Chief of the General Staff

, Helmuth von Moltke

. Hindenburg was given command of the Eighth Army, then locked in combat with the First and Second Russian armies in East Prussia

; after defeat by the Russian First Army at Gumbinnen

, Hindenburg's predecessor Maximilian von Prittwitz

had been planning to abandon East Prussia and retreat behind the River Vistula.

Hindenburg's Eighth Army was victorious in the Battle of Tannenberg

and the Battle of the Masurian Lakes against the Russian armies. Although historians attach much of the credit to Erich Ludendorff

and to the then little-known staff officer Max Hoffmann

, these successes made Hindenburg a national hero.

At the start of November 1914 Hindenburg was given the position of Supreme Commander East (Ober-Ost) – although at this stage his authority only extended over the German, not the Austro-Hungarian

, portion of the front – and units were transferred from East Prussia

to form a new Ninth Army in south-western Poland

. Later in November 1914, after the Battle of Lodz, Hindenburg was promoted to the rank of field marshal

. A further battle was fought by the Eighth and newly-formed Tenth Armies in Masuria that winter. Ober-Ost eventually consisted of the German Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Armies, plus other assorted corps.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff felt that more effort should be made on the Eastern Front

in order to defeat Russia

, although ironically the most spectacular victory of 1915, the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive, was won by Mackensen's German Eleventh Army fighting on the Austro-Hungarian sector rather than as part of Hindenburg's command. By contrast Erich von Falkenhayn

, the Chief of the General Staff, felt that it was impossible for Germany to win a decisive victory, hoped that Russia might be encouraged to drop out of the war if not pressed too hard, and in 1916 unleashed an offensive at Verdun

designed to "bleed France white" and encourage her to make peace. Hindenburg desired to conquer the Baltic region from the Russian Empire; not only as he put it "the maneuvering of my left wing in the next war" but as colonial possessions as well, from which the native population would be removed and the region repopulated with "physically and mentally healthy beings"

Though Hindenburg was only average in terms of military ability, he had a team of talented and able subordinates who won him a series of great victories on the Eastern Front between 1914–1916. These victories transformed Hindenburg into Germany's most popular man. During the war, Hindenburg was the subject of an enormous personality cult. He was seen as the perfect embodiment of German manly honour, rectitude, decency and strength. The appeal of the Hindenburg cult cut across ideological, religious, class and regional lines, but the group that idolized Hindenburg the most were the German right who saw him as an ideal representative of the Prussian ethos and of Lutheran, Junker

values. During the war, there were wooden statues of Hindenburg built all over Germany, onto which people nailed money and cheques for war bonds. It was a measure of Hindenburg's public appeal that when the Government launched an all-out programme of industrial mobilisation in 1916, the programme was named the Hindenburg Programme. Before 1914, any such programme would have been named the Kaiser Wilhelm Programme.

By the summer of 1916 Erich von Falkenhayn

had been discredited by the bogging-down of the Verdun Offensive and the near-collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army caused by the Brusilov Offensive

and the entry of Romania into the war on the Allied side. In August Hindenburg succeeded him as Chief of the General Staff, although real power was exercised by his deputy, Erich Ludendorff

. Hindenburg in many ways served as the real commander-in-chief of the German armed forces instead of the Kaiser who had been reduced to a mere figurehead while Ludendorff served as the de facto general chief of staff. From 1916 onwards, Germany became an unofficial military dictatorship, often called the "Silent dictatorship" by historians.

In September 1918, Ludendorff advised seeking an armistice

with the Allies

, but in October, changed his mind and resigned in protest. Ludendorff had expected Hindenburg to follow him by also resigning, but Hindenburg refused on the grounds that in this hour of crisis, he could not desert the men under his command. Ludendorff never forgave Hindenburg for this. Ludendorff was succeeded by Wilhelm Groener

, a staff officer who served as Hindenburg's assistant until 1932. In November 1918, Hindenburg and Groener played a decisive role in persuading the Kaiser Wilhelm II

to abdicate for the greater good of Germany.

Hindenburg, who was a firm monarchist throughout his life, always regarded this episode with considerable embarrassment, and almost from the moment the Kaiser abdicated, Hindenburg insisted that he had played no role in the abdication and assigned all of the blame to Groener. Groener, for his part, went along in order to protect Hindenburg's reputation

Commission that was investigating the responsibility for both the outbreak of war in 1914 and for the defeat in 1918.

Hindenburg had not wanted to appear before the commission, and had been subpoena

ed. The appearance of Hindenburg before the commission was an eagerly awaited public event. Ludendorff, who had fallen out with Hindenburg over the decision to continue seeking the armistice in October 1918, was concerned that Hindenburg might reveal that it was he who had advised seeking an armistice in September 1918. Ludendorff wrote a letter to Hindenburg, informing him that he was writing his memoirs and threatened to expose the fact that Hindenburg did not deserve the credit that he had received for his victories. Ludendorff's letter went on to suggest that how Hindenburg testified would determine how favorably Ludendorff would present Hindenburg in his memoirs.

When Hindenburg did appear before the commission, he refused to answer any questions about the responsibility for the German defeat, and instead read out a prepared statement that had been reviewed in advance by Ludendorff's lawyer. Hindenburg testified that the German Army had been on the verge of winning the war in the autumn of 1918, and that the defeat had been precipitated by a Dolchstoß ("stab in the back") by disloyal elements on the home front and by unpatriotic politicians. Despite being threatened with a contempt

citation for refusing to respond to questions, Hindenburg simply walked out of the hearings after reading his statement. Hindenburg's status as a war hero provided him with a political shield and he was never prosecuted.

Hindenburg's testimony was the first use of the Dolchstoßlegende. The field marshal credited an unnamed British general for first uttering the phrase, and the term was adopted by nationalist and conservative politicians who sought to blame the socialist founders of the Weimar Republic

for the loss of the war.

Afterwards, Hindenburg had his memoirs entitled Mein Leben (My Life) ghost-written in 1919–20. Mein Leben was a huge bestseller in Germany, but was dismissed by most military historians and critics as a boring apologia that skipped over the most controversial issues in Hindenburg's life. Afterwards, Hindenburg retired from most public appearances and spent most of his time with his family. A widower, Hindenburg was very close to his only son, Major Oskar von Hindenburg

and his granddaughters.

In 1925, Hindenburg had no interest in running for public office. In the first round of the presidential election

In 1925, Hindenburg had no interest in running for public office. In the first round of the presidential election

held on 29 March 1925, no candidate had emerged with a majority and a run-off election had been called. The Social Democratic

candidate, Prime Minister Otto Braun

of Prussia

, had agreed to drop out of the race and had endorsed the Catholic Centre Party's candidate, Wilhelm Marx

. Since Karl Jarres

, the joint candidate of the two conservative parties, the German People's Party

(DVP) and the German National People's Party

(DNVP), was regarded as too dull, it seemed likely that Marx would win. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

, one of the leaders of the DNVP, visited Hindenburg and urged him to run.

Hindenburg initially demurred, but under strong pressure from Tirpitz applied over several meetings, broke down and agreed to run. Though Hindenburg ran during the second round of the elections as a non-party independent, he was generally regarded as the conservative candidate. Largely because of his status as Germany's greatest war hero, Hindenburg won the election in the second round of voting held on 26 April 1925. He was aided by the support of the Bavarian People's Party

(BVP), which switched from supporting Marx, and the refusal of the Communist Party of Germany

(KPD) to withdraw its candidate, Ernst Thälmann

(if either had supported Marx he would have won).

Hindenburg took office on 12 May 1925. For the first five years after taking office, he fulfilled his duties of office with dignity and decorum. For the most part, Hindenburg refused to allow himself to be drawn into the maelstrom of German politics in the period, and sought to play the role of a republican equivalent of a constitutional monarch. Although often referred to as the Ersatzkaiser (substitute Emperor), Hindenburg made no effort to restore the monarchy and took his oath to the Weimar Constitution

Hindenburg took office on 12 May 1925. For the first five years after taking office, he fulfilled his duties of office with dignity and decorum. For the most part, Hindenburg refused to allow himself to be drawn into the maelstrom of German politics in the period, and sought to play the role of a republican equivalent of a constitutional monarch. Although often referred to as the Ersatzkaiser (substitute Emperor), Hindenburg made no effort to restore the monarchy and took his oath to the Weimar Constitution

seriously. In 1927 he shocked the international opinion by his statements defending Germany's actions and entry in World War I, when he declared that it entered the war as "the means of self-assertion against a world full of enemies. Pure in heart we set off to the defence of the fatherland and with clean hands the German army carried the sword."

In private, Hindenburg often complained that he missed the quiet of his retirement and bemoaned that he had allowed himself to be pressured into running for President. Hindenburg carped that politics was full of issues such as economics that he did not, and did not want to, understand. He was surrounded, however, by a coterie of advisers antipathetic to the Weimar constitution. These advisers included his son, Oskar

, Otto Meißner

, General Wilhelm Groener

, and General Kurt von Schleicher

. This group were known as the Kamarilla

.

The younger Hindenburg served as his father's aide-de-camp

and controlled politicians' access to the President.

Schleicher was a close friend of Oskar and came to enjoy privileged access to Hindenburg. It was he who came up with the idea of Presidential government based on the so-called "25/48/53 formula". Under a "Presidential" government the head of government

(in this case, the chancellor

), is responsible to the head of state

, and not a legislative body. The "25/48/53 formula" referred to the three articles of the Constitution that could make a "Presidential government" possible:

Schleicher's idea was to have Hindenburg appoint a man of Schleicher's choosing as chancellor, who would rule under the provisions of Article 48. If the Reichstag

should threaten to annul any laws so passed, Hindenburg could counter with the threat of dissolution

. Hindenburg was unenthusiastic about these plans, but was pressured into going along with them by his son along with Meißner, Groener and Schleicher.

The first attempt to establish a "presidential government" had occurred in 1926–1927, but foundered for lack of political support. During the winter of 1929–1930, however, Schleicher had more success. After a series of secret meetings attended by Meißner, Schleicher, and Heinrich Brüning

The first attempt to establish a "presidential government" had occurred in 1926–1927, but foundered for lack of political support. During the winter of 1929–1930, however, Schleicher had more success. After a series of secret meetings attended by Meißner, Schleicher, and Heinrich Brüning

, the parliamentary leader of the Catholic Center Party (Zentrum), Schleicher and Meißner were able to persuade Brüning to go along with the scheme for "presidential government". How much Brüning knew of Schleicher's ultimate objective of dispensing with democratic governance is unclear. Schleicher maneuvered to exacerbate a bitter dispute within the "Grand Coalition" government of the Social Democrats

and the German People's Party

over whether the unemployment insurance rate should be raised by a half percentage point or a full percentage point. The upshot of these intrigues was the fall of Müller’s government in March 1930 and Hindenburg's appointment of Brüning as Chancellor.

Brüning's first official act was to introduce a budget calling for steep spending cuts and steep tax increases. When the budget was defeated in July 1930, Brüning arranged for Hindenburg to sign the budget into law by invoking Article 48. When the Reichstag voted to repeal the budget, Brüning had Hindenburg dissolve the Reichstag, just two years into its mandate, and reapprove the budget through the Article 48 mechanism. In the September 1930 elections the Nazis

achieved an electoral breakthrough, gaining 17 percent of the vote, up from 2 percent in 1928. The Communist Party of Germany

also made striking gains, albeit not so great.

After the 1930 elections, Brüning continued to govern largely through Article 48; his government was kept afloat by the support of the Social Democrats who voted not to cancel his Article 48 bills in order not to have another election that could only benefit the Nazis and the Communists. Hindenburg for his part grew increasingly annoyed at Brüning, complaining that he was growing tired of using Article 48 all the time to pass bills. Hindenburg found the detailed notes that Brüning submitted explaining the economic necessity of each of his bills to be incomprehensible. Brüning continued with his policies of raising taxes and cutting spending to address the onset of the Great Depression

; the only areas in which government spending increased were the military budget and the subsidies for Junkers in the so-called Osthilfe (Eastern Aid) program. Both of these spending increases reflected Hindenburg's concerns.

In October 1931, Hindenburg and Adolf Hitler

had their first meeting over the German Nationalist Party's politics. Both men took an immediate dislike to each other. In private, Hindenburg disparagingly referred to Hitler as "that Austrian corporal", or "that Bohemian

corporal" or sometimes just simply as "the corporal", while Hitler often disparagingly referred to Hindenburg as "that old fool" or "that old reactionary

". Until January 1933, Hindenburg often stated that he would never appoint Hitler as Chancellor under any circumstances. On 26 January 1933, Hindenburg privately told a group of his friends: "Gentlemen, I hope you will not hold me capable of appointing this Austrian corporal to be Reich Chancellor".

By January 1932, at 84-years-old, Hindenburg was now lapsing in and out of senility and wanted to leave office as soon as his seven-year presidential term was over, but he was persuaded to run for re-election in 1932

By January 1932, at 84-years-old, Hindenburg was now lapsing in and out of senility and wanted to leave office as soon as his seven-year presidential term was over, but he was persuaded to run for re-election in 1932

by the Kamarilla, as well as by the Centre and the liberals, and by the Social Democratic Party

(SPD). The SPD regarded Hindenburg as the only man who could defeat Hitler and the Nazi party from winning the elections (and they said so throughout the campaign), and expected him to keep Brüning in office. Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to stay in office, but wanted to avoid an election. The only way this was possible was for the Reichstag

to vote to cancel the election with a two-thirds supermajority

. Since the Nazis were the second-largest political party, their co-operation was vital if this was to be done. Brüning met with Hitler in January 1932 to ask if he would agree to the President Hindenburg's demand to forgo the election. Surprisingly, Hitler supported the measure, but with one major condition: dissolve the Reichstag and hold new elections.

Brüning rejected Hitler's demands as totally outrageous and unreasonable. By this time, Schleicher had decided that Brüning had become an obstacle to his plans and was already plotting Brüning's downfall. Schleicher convinced Hindenburg that the reason why Hitler had rejected Brüning's offer was because Brüning had deliberately sabotaged the talks to force the elderly president into a grueling re-election battle. During the election campaign of 1932, Brüning had campaigned hard for Hindenburg's re-election. As Hindenburg was in bad health and a poor speaker in any case, the task of traveling the country and delivering speeches for Hindenburg had fallen upon Brüning. Hindenburg’s campaign appearances usually consisted simply of appearing before the crowd and waving to them without speaking.

In the first round of the election held in March 1932

, Hindenburg emerged as the frontrunner, but failed to gain a majority. In the runoff election

of April 1932, Hindenburg defeated Hitler for the Presidency thus securing his re-election. After the presidential elections had ended, Schleicher held a series of secret meetings with Hitler in May 1932, and thought that he had obtained a "gentleman's agreement" in which Hitler had agreed to support the new "presidential government" that Schleicher was building. At the same time, Schleicher, with Hindenburg's complicit consent, had set about undermining Brüning's government.

The first blow occurred in May 1932, when Schleicher had Hindenburg dismiss Groener as Defense Minister in a way that was designed to humiliate both Groener and Brüning. On 31 May 1932, Hindenburg dismissed Brüning as Chancellor and replaced him with the man that Schleicher had suggested, Franz von Papen

The first blow occurred in May 1932, when Schleicher had Hindenburg dismiss Groener as Defense Minister in a way that was designed to humiliate both Groener and Brüning. On 31 May 1932, Hindenburg dismissed Brüning as Chancellor and replaced him with the man that Schleicher had suggested, Franz von Papen

. "The Government of Barons", as Papen's government was known, openly had as its objective the destruction of German democracy. Like Brüning's government, Papen's government was a "presidential government" that governed through the use of Article 48.

Unlike Brüning, Papen ingratiated himself to Hindenburg and his son through flattery. Much to Schleicher's annoyance, Papen quickly replaced him as Hindenburg's favorite advisor. The French Ambassador André François-Poncet

reported to his superiors in Paris that "It's he [Papen] who is the preferred one, the favorite of the Marshal; he diverts the old man through his vivacity, his playfulness; he flatters him by showing him respect and devotion; he beguiles him with his daring; he is in [Hindenburg's] eyes the perfect gentleman."

In accordance with Schleicher's "gentleman's agreement", Hindenburg dissolved the Reichstag and set new elections for July 1932. Schleicher and Papen both believed that the Nazis would win the majority of the seats and would support Papen's government. Hitler staged an electoral comeback, with his Nazi

party winning a solid plurality of seats in the Reichstag

. Following the Nazi electoral triumph in the Reichstag elections held on 31 July 1932, there were widespread expectations that Hitler would soon be appointed Chancellor. Moreover, Hitler repudiated the "gentleman's agreement" and declared that he wanted the Chancellorship for himself. In a meeting between Hindenburg and Hitler held on 13 August 1932, in Berlin, Hindenburg firmly rejected Hitler's demands for the Chancellorship.

The minutes of the meeting were kept by Otto Meißner

, the Chief of the Presidential Chancellery. According to the minutes:

After refusing Hitler’s demands for the Chancellorship, Hindenburg had a press release

issued of his meeting with Hitler that implied that Hitler had demanded absolute power and had his knuckles rapped by the President for making such a demand. Hitler was enraged by this press release. However, given Hitler’s determination to take power legally, Hindenburg’s refusal to appoint him Chancellor was an impassable quandary for Hitler.

When the Reichstag convened in September 1932, its first and only act was to pass a massive vote of no-confidence in Papen’s government. In response, Papen had Hindenburg dissolve the Reichstag for elections in November 1932. The second Reichstag elections saw the Nazi vote drop from 37 percent to 32 percent, though the Nazis once again remained the largest party in the Reichstag. After the November elections, there ensued another round of fruitless talks between Hindenburg, Papen, Schleicher on the one hand and Hitler and the other Nazi leaders on the other.

The President and the Chancellor wanted Nazi support for the "Government of the President's Friends"; at most they were prepared to offer Hitler the meaningless office of Vice-Chancellor. On 24 November 1932, during the course of another Hitler-Hindenburg meeting, Hindenburg stated his fears that " ... a presidential cabinet led by Hitler would necessarily develop into a party dictatorship with all its consequences for an extreme aggravation of the conflicts within the German people".

Hitler for his part, remained adamant that Hindenburg give him the Chancellorship and nothing else. These demands were incompatible and unacceptable to both sides and the stalemate continued. To break the political stalemate, Papen proposed that Hindenburg declare martial law

and do away with democracy via a presidential coup. Papen won over Oskar Hindenburg with this idea and the two persuaded Hindenburg for once to forgo his oath to the Constitution and go along with this plan. Schleicher, who had come to see Papen as a threat, blocked the martial law move by unveiling the results of a war games exercise

that showed if martial law was declared, the Nazi SA

and the Communist Red Front Fighters would rise up, the Poles would invade and the Reichswehr

would be unable to cope.

Whether this was the honest result of a war games exercise or just a fabrication by Schleicher to force Papen out of office is a matter of some historical debate. The opinion of most leans towards the latter, for in January 1933 Schleicher would tell Hindenburg that new war games had shown the Reichswehr would crush both the SA and Red Front Fighters and defend the eastern borders from a Polish invasion. The results of the war games forced Papen to resign in December 1932 in favor of Schleicher. Hindenburg was most upset at losing his favorite Chancellor, and suspecting that the war games were faked to force Papen out, came to bear a grudge against Schleicher.

Papen for his part, was determined to get back into office and on 4 January 1933, Papen met with Hitler to discuss how they could bring down Schleicher’s government, though the talks were inconclusive largely because Papen and Hitler each coveted the Chancellorship for himself. However, Papen and Hitler agreed to keep talking. Ultimately, Papen came to believe that he could control Hitler from behind the scenes and decided to support him for Chancellor. Papen then persuaded Meißner and the younger Hindenburg of the merits of his plan, and the three then spent the second half of January pressuring Hindenburg into naming Hitler as Chancellor. Hindenburg was most loath to consider Hitler as Chancellor and preferred that Papen hold that office instead.

However, the pressure from Meißner, Papen and the younger Hindenburg was relentless and by the end of January, the President had decided to appoint Hitler Chancellor. On the morning of 30 January 1933, Hindenburg swore Hitler in as Chancellor at the Presidential Palace.

Hindenburg played a supporting but key role in the Nazi Machtergreifung

Hindenburg played a supporting but key role in the Nazi Machtergreifung

(Seizure of Power) in 1933. In the "Government of National Concentration" headed by Hitler, the Nazis were in the minority. Besides Hitler, the only other Nazi ministers were Hermann Göring

and Wilhelm Frick

. Frick held the then-powerless Interior Ministry, while Göring was given no portfolio. Most of the other ministers were hold-overs from the Papen and Schleicher governments, and the ones who were not, such as Alfred Hugenberg

of the DNVP

, were not Nazis. This had the effect of assuring Hindenburg that the room for radical moves on the part of the Nazis was limited. Moreover, Hindenburg's favorite politician, Papen, was Vice Chancellor of the Reich and Minister-President of Prussia.

Hitler's first act as Chancellor was to ask Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag

so that the Nazis and DNVP could increase their number of seats and pass the Enabling Act. Hindenburg agreed to this request. In early February 1933, Papen asked for and received an Article 48 bill signed into law that sharply limited freedom of the press

. After the Reichstag fire

, Hindenburg, at Hitler's urging, signed into law the Reichstag Fire Decree

. This decree suspended all civil liberties in Germany.

At the opening of the new Reichstag on 21 March 1933, at the Kroll Opera House, the Nazis staged an elaborate ceremony, in which Hindenburg played the leading part, appearing alongside Hitler during the event, that was meant to mark the continuity between the old Prussian-German tradition and the new Nazi state. The ceremony at the Kroll Opera House had the effect of reassuring many Germans, especially conservative Germans, that life would be fine under the new regime. On 23 March 1933, Hindenburg signed the Enabling Act of 1933 into law, which gave decrees issued by the cabinet (in effect, Hitler) the force of law.

Though Hindenburg was in increasingly bad health, the Nazis made sure that whenever Hindenburg did appear in public it was in Hitler’s company. During these appearances, Hitler always made a point of showing the utmost respect and reverence for the President. However in private, Hitler continued to detest Hindenburg, and expressed the hope that "the old reactionary" would hurry up and die as soon as possible, so that Hitler could merge the offices of Chancellor and President into one.

During 1933 and 1934, Chancellor Hitler, as the Head of government

, was very aware of the fact that President Hindenburg was his only superior being the Head of state

as well as the Supreme Commander-In-Chief of the German armed forces, and given that Hindenburg was still a popular war hero a revered figure in the German Army

, that if the President decided to remove Hitler as Chancellor, there was little doubt that the Reichswehr would side with Hindenburg. Thus, as long as Hindenburg was alive, Hitler was always very careful to avoid offending him.

The only time Hindenburg ever objected to a Nazi bill occurred in early April 1933 when the Reichstag had passed a Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service

that called for the immediate dismissal of all Jewish civil servants at the Reich,

Land, and municipal levels. Hindenburg refused to sign this bill into law until it had been amended to exclude all Jewish veterans of World War I, Jewish civil servants who served in the civil service during the war and those Jewish civil servants whose fathers were veterans. Hitler amended the bill to meet Hindenburg’s objections, and was later to be surprised at the number of Jews whose jobs were protected by the amendments.

Hindenburg remained in office until his death at the age of 86 from lung cancer at his home in Neudeck, East Prussia

on 2 August 1934).

The day before Hindenburg's death, Hitler flew to Neudeck and visited him. Hindenburg, old and senile as well as bedridden from being very sick, thought he was meeting Kaiser Wilhelm II, and he called Hitler "Your Majesty" when Hitler first walked into the room.

Following Hindenburg's death, Hitler merged the presidency with the office of Chancellor under the title of Leader and Chancellor (Führer und Reichskanzler), making himself Germany's Head of State and Head of government, thereby completing the progress of Gleichschaltung

Following Hindenburg's death, Hitler merged the presidency with the office of Chancellor under the title of Leader and Chancellor (Führer und Reichskanzler), making himself Germany's Head of State and Head of government, thereby completing the progress of Gleichschaltung

. This action effectively removed the last remedy by which Hitler could be legally removed from office—and with it, all institutional checks and balances on his power.

Hitler had a plebiscite held on 19 August 1934, in which the German people were asked if they approved of Hitler merging the two offices. The Ja (Yes) vote amounted to 90% of the vote.

In taking over the president's powers for himself without calling for a new election, Hitler technically violated the provisions of the Enabling Act. While the Enabling Act allowed Hitler to pass laws that contravened the Weimar Constitution, it specifically forbade him from interfering with the powers of the president. Moreover, the Weimar Constitution had been amended in 1932 to make the president of the High Court of Justice, not the chancellor, acting president pending a new elections. However, Hitler had become law unto himself by this time, and no one dared object.

Hindenburg himself was said to be a monarchist who favored a restoration of the German monarchy. Though he hoped one of the Prussian princes would be appointed to succeed him as Head of State

, he did not attempt to use his powers in favour of such a restoration, as he considered himself bound by the oath he had sworn on the Weimar Constitution

.

It has been alleged that Hindenburg’s will asked for Hitler to restore the monarchy. However, the truth of this story cannot be established as Oskar von Hindenburg destroyed the portions of his father’s will relating to politics.

Hindenburg's remains were moved no fewer than six times in the 12 years following his initial interrment.

Hindenburg's remains were moved no fewer than six times in the 12 years following his initial interrment.

Hindenburg was originally buried in the yard of the castle-like Tannenberg Memorial

near Tannenberg, East Prussia

(today: Stębark

, Poland), on 7 August 1934 during a large state funeral, five days after his death. This was against the wishes he had expressed during his life – to be buried in his family plot in Hanover

, Germany, next to his wife Gertrud who had died in 1921.

The following year, Hindenburg was temporarily disinterred, along with the 20 German unknown soldiers buried at the Tannenberg Memorial, to allow the building of his new crypt there (which required lowering the entire plaza 8 feet). Hindenburg's bronze coffin was placed in the crypt on 2 October 1935 (the anniversary of his birthday), along with the coffin bearing his wife, which was moved from the family plot.

In January 1945, as Soviet forces advanced into East Prussia, Hitler ordered both coffins to be disinterred for their safety. They were first moved to a bunker just outside Berlin, then to a salt mine at the village of Bernterode, Germany

, along with the remains of both Wilhelm I, German Emperor and Frederick II of Prussia

(Frederick the Great). The four coffins were hastily marked of their contents using red crayon, and interred behind a 6 feet (1.8 m) masonry wall in a deep recess of the 14-mile mine complex, 1,800 feet underground. Three weeks later, on 27 April 1945, the coffins were discovered by U.S. Army Ordnance troops after tunneling through the wall. All were subsequently moved to the basement of the heavily guarded Marburg Castle in Marburg an der Lahn, Germany, a collection point for recovered Nazi plunder

.

The U.S. Army, in a secret project dubbed "Operation Bodysnatch", had many difficulties in determining the final resting places for the four famous Germans. 16 months after the salt mine discovery, in August 1946, the remains of Hindenburg and his wife were finally laid to rest by the American army at St. Elizabeth's

, the church of his Teutonic ancestors in Marburg, where they remain today.

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n-German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

field marshal

Generalfeldmarschall

Field Marshal or Generalfeldmarschall in German, was a rank in the armies of several German states and the Holy Roman Empire; in the Austrian Empire, the rank Feldmarschall was used...

, statesman

Statesman

A statesman is usually a politician or other notable public figure who has had a long and respected career in politics or government at the national and international level. As a term of respect, it is usually left to supporters or commentators to use the term...

, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934.

Hindenburg enjoyed a long career in the Prussian Army

Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army was the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It was vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.The Prussian Army had its roots in the meager mercenary forces of Brandenburg during the Thirty Years' War...

, retiring in 1911. He was recalled at the outbreak of World War I, and first came to national attention, at the age of 66, as the victor at Tannenberg

Battle of Tannenberg (1914)

The Battle of Tannenberg was an engagement between the Russian Empire and the German Empire in the first days of World War I. It was fought by the Russian First and Second Armies against the German Eighth Army between 23 August and 30 August 1914. The battle resulted in the almost complete...

in 1914. As Germany's Chief of the General Staff from 1916, he and his deputy, Erich Ludendorff

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff was a German general, victor of Liège and of the Battle of Tannenberg...

, rose in the German public's esteem until Hindenburg came to eclipse the Kaiser himself. Hindenburg retired again in 1919, but returned to public life one more time in 1925 to be elected as the second President of Germany

President of Germany

The President of the Federal Republic of Germany is the country's head of state. His official title in German is Bundespräsident . Germany has a parliamentary system of government and so the position of President is largely ceremonial...

.

Though 84 years old and in poor health, Hindenburg was persuaded to run for re-election in 1932

German presidential election, 1932

The presidential election of 1932 was the second and final direct election to the office of President of the Reich , Germany's head of state during the 1919-1934 Weimar Republic. The incumbent President, Paul von Hindenburg, had been elected in 1925 but his seven year term expired in May...

, as he was considered the only candidate who could defeat Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

. Hindenburg was re-elected in a runoff

Two-round system

The two-round system is a voting system used to elect a single winner where the voter casts a single vote for their chosen candidate...

. Although he was opposing Hitler, the deteriorating political stability of the Weimar Republic let him play an important role in the Nazi Party's rise to power. He dissolved the parliament twice in 1932 and eventually appointed Hitler as Chancellor in January 1933. In February, he issued the Reichstag Fire Decree

Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State issued by German President Paul von Hindenburg in direct response to the Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933. The decree nullified many of the key civil liberties of German...

which suspended various civil liberties

Civil liberties

Civil liberties are rights and freedoms that provide an individual specific rights such as the freedom from slavery and forced labour, freedom from torture and death, the right to liberty and security, right to a fair trial, the right to defend one's self, the right to own and bear arms, the right...

, and in March he signed the Enabling Act, in which the parliament gave Hitler's administration legislative powers. Hindenburg died the following year, after which Hitler declared the office of President vacant and, as "Führer

Führer

Führer , alternatively spelled Fuehrer in both English and German when the umlaut is not available, is a German title meaning leader or guide now most associated with Adolf Hitler, who modelled it on Benito Mussolini's title il Duce, as well as with Georg von Schönerer, whose followers also...

und Reichskanzler", made himself head of state

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

.

The famed zeppelin

Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship pioneered by the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin in the early 20th century. It was based on designs he had outlined in 1874 and detailed in 1893. His plans were reviewed by committee in 1894 and patented in the United States on 14 March 1899...

Hindenburg

LZ 129 Hindenburg

LZ 129 Hindenburg was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, the longest class of flying machine and the largest airship by envelope volume...

that was destroyed by fire in 1937

Hindenburg disaster

The Hindenburg disaster took place on Thursday, May 6, 1937, as the German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, which is located adjacent to the borough of Lakehurst, New Jersey...

was named in his honor, as was the Hindenburgdamm

Hindenburgdamm

The Hindenburgdamm is an 11 km-long causeway joining the North Frisian island of Sylt to mainland Schleswig-Holstein. Its coordinates are . It was opened on 1 June 1927 and is exclusively a railway corridor...

, a causeway

Causeway

In modern usage, a causeway is a road or railway elevated, usually across a broad body of water or wetland.- Etymology :When first used, the word appeared in a form such as “causey way” making clear its derivation from the earlier form “causey”. This word seems to have come from the same source by...

joining the island of Sylt

Sylt

Sylt is an island in northern Germany, part of Nordfriesland district, Schleswig-Holstein, and well known for the distinctive shape of its shoreline. It belongs to the North Frisian Islands and is the largest island in North Frisia...

to mainland Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein is the northernmost of the sixteen states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Schleswig...

that was built during his time in office. The previously German Upper Silesian town of Zabrze

Zabrze

Zabrze is a city in Silesia in southern Poland, near Katowice. The west district of the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union is a metropolis with a population of around 2 million...

was also renamed for him in 1915. SMS Hindenburg

SMS Hindenburg

SMS Hindenburg"SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German. was a battlecruiser of the German Kaiserliche Marine and the third ship of the . She was named in honor of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the victor of the Battle of Tannenberg and the Battle of the...

, a battlecruiser

Battlecruiser

Battlecruisers were large capital ships built in the first half of the 20th century. They were developed in the first decade of the century as the successor to the armoured cruiser, but their evolution was more closely linked to that of the dreadnought battleship...

commissioned in the Imperial German Navy in 1917 and the last capital ship to enter service in the Imperial Navy, was also named for him.

Early years

Paul von Hindenburg was born in Posen, PrussiaKingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

(Polish: Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

; until 1793

Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the second of three partitions that ended the existence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition occurred in the aftermath of the War in Defense of the Constitution and the Targowica Confederation of 1792...

and since 1919

Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919)

The Greater Poland Uprising of 1918–1919, or Wielkopolska Uprising of 1918–1919 or Posnanian War was a military insurrection of Poles in the Greater Poland region against Germany...

part of Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

) on Podgórna street, the son of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n aristocrat Robert von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893), the daughter of medical doctor Karl Ludwig Schwickart and wife Julie Moennich, cousin of Vincent Couling. Hindenburg was embarrassed by his mother's non-aristocratic background, and hardly mentioned her at all in his memoirs. His paternal lineage was considered highly distinguished. His paternal grandparents were Otto Ludwig von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1778–18 July 1855), through whom he was remotely descended from the illegitimate daughter of Count Heinrich VI of Waldeck

Waldeck (state)

Waldeck was a sovereign principality in the German Empire and German Confederation and, until 1929, a constituent state of the Weimar Republic. It comprised territories in present-day Hesse and Lower Saxony, ....

, and wife Eleonore von Brederlow (d. 18 February 1863). Hindenburg was also a direct descendant of Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

and wife Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora, referred to as "die Lutherin", was the wife of Martin Luther, Germanleader of the Protestant Reformation. Beyond what is found in the writings of Luther and some of his contemporaries, little is known about her...

, through their daughter Margareta Luther. Hindenburg's younger brothers and sister were Otto, born 24 August 1849, Ida, born 19 December 1851 and Bernhard, born 17 January 1859.

German Army

After his education at Wahlstatt (now Legnickie PoleLegnickie Pole

Legnickie Pole is a village in Legnica County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in south-western Poland. It is the seat of the administrative district called Gmina Legnickie Pole. Prior to 1945 it was in Germany....

) and Berlin cadet schools, he fought in the Austro-Prussian War

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War was a war fought in 1866 between the German Confederation under the leadership of the Austrian Empire and its German allies on one side and the Kingdom of Prussia with its German allies and Italy on the...

(1866) and the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

(1870–1871). Hindenburg was selected for prestigious duties: serving the widow

Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria

Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria was a Princess of Bavaria and later Queen consort of Prussia.-Early life and family:...

of King Frederick William IV of Prussia

Frederick William IV of Prussia

|align=right|Upon his accession, he toned down the reactionary policies enacted by his father, easing press censorship and promising to enact a constitution at some point, but he refused to enact a popular legislative assembly, preferring to work with the aristocracy through "united committees" of...

, being present – as one of a group of young officers decorated for bravery in battle, who had been chosen to represent their regiments – in the Palace of Versailles

Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles , or simply Versailles, is a royal château in Versailles in the Île-de-France region of France. In French it is the Château de Versailles....

when the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

was proclaimed on 18 January 1871, and as Honour Guard prior to the Military funeral

Military funeral

A military funeral is a specially orchestrated funeral given by a country's military for a soldier, sailor, marine or airman who died in battle, a veteran, or other prominent military figures or heads of state. A military funeral may feature guards of honor, the firing of volley shots as a salute,...

of Emperor William I in 1888. Hindenburg remained in the army, eventually commanding a corps and being promoted to General of Infantry (equivalent to a British or US lieutenant-general; the German equivalent to four-star rank was Colonel-General) in 1903. Meanwhile, he married Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921), also an aristocrat, by whom he had two daughters, Irmengard Pauline (1880) and Annemaria (1891) and one son, Oskar

Oskar von Hindenburg

Generalleutnant Oskar von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg was the politically powerful son and aide-de-camp to Field Marshal and President of Germany Paul von Hindenburg....

(1883).

World War I

German General Staff

The German General Staff was an institution whose rise and development gave the German armed forces a decided advantage over its adversaries. The Staff amounted to its best "weapon" for nearly a century and a half....

, Helmuth von Moltke

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger

Helmuth Johann Ludwig von Moltke , also known as Moltke the Younger, was a nephew of Field Marshal Count Moltke and served as the Chief of the German General Staff from 1906 to 1914. The two are often differentiated as Moltke the Elder and Moltke the Younger...

. Hindenburg was given command of the Eighth Army, then locked in combat with the First and Second Russian armies in East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

; after defeat by the Russian First Army at Gumbinnen

Battle of Gumbinnen

The Battle of Gumbinnen, initiated by forces of the German Empire on August 20, 1914, was the first major German offensive on the Eastern Front during the First World War...

, Hindenburg's predecessor Maximilian von Prittwitz

Maximilian von Prittwitz

Maximillion Von Prittwitz was a German General.-Family:Prittwitz came from an extremely old aristocratic Silesian family in Bernstadt...

had been planning to abandon East Prussia and retreat behind the River Vistula.

Hindenburg's Eighth Army was victorious in the Battle of Tannenberg

Battle of Tannenberg (1914)

The Battle of Tannenberg was an engagement between the Russian Empire and the German Empire in the first days of World War I. It was fought by the Russian First and Second Armies against the German Eighth Army between 23 August and 30 August 1914. The battle resulted in the almost complete...

and the Battle of the Masurian Lakes against the Russian armies. Although historians attach much of the credit to Erich Ludendorff

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff was a German general, victor of Liège and of the Battle of Tannenberg...

and to the then little-known staff officer Max Hoffmann

Max Hoffmann

Max Hoffmann was a German officer and military strategist during World War I. He is widely regarded as one of the finest staff officers of the imperial period....

, these successes made Hindenburg a national hero.

At the start of November 1914 Hindenburg was given the position of Supreme Commander East (Ober-Ost) – although at this stage his authority only extended over the German, not the Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

, portion of the front – and units were transferred from East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

to form a new Ninth Army in south-western Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

. Later in November 1914, after the Battle of Lodz, Hindenburg was promoted to the rank of field marshal

Generalfeldmarschall

Field Marshal or Generalfeldmarschall in German, was a rank in the armies of several German states and the Holy Roman Empire; in the Austrian Empire, the rank Feldmarschall was used...

. A further battle was fought by the Eighth and newly-formed Tenth Armies in Masuria that winter. Ober-Ost eventually consisted of the German Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Armies, plus other assorted corps.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff felt that more effort should be made on the Eastern Front

Eastern Front (World War I)

The Eastern Front was a theatre of war during World War I in Central and, primarily, Eastern Europe. The term is in contrast to the Western Front. Despite the geographical separation, the events in the two theatres strongly influenced each other...

in order to defeat Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, although ironically the most spectacular victory of 1915, the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive, was won by Mackensen's German Eleventh Army fighting on the Austro-Hungarian sector rather than as part of Hindenburg's command. By contrast Erich von Falkenhayn

Erich von Falkenhayn

Erich von Falkenhayn was a German soldier and Chief of the General Staff during World War I. He became a military writer after World War I.-Early life:...

, the Chief of the General Staff, felt that it was impossible for Germany to win a decisive victory, hoped that Russia might be encouraged to drop out of the war if not pressed too hard, and in 1916 unleashed an offensive at Verdun

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February – 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France...

designed to "bleed France white" and encourage her to make peace. Hindenburg desired to conquer the Baltic region from the Russian Empire; not only as he put it "the maneuvering of my left wing in the next war" but as colonial possessions as well, from which the native population would be removed and the region repopulated with "physically and mentally healthy beings"

Though Hindenburg was only average in terms of military ability, he had a team of talented and able subordinates who won him a series of great victories on the Eastern Front between 1914–1916. These victories transformed Hindenburg into Germany's most popular man. During the war, Hindenburg was the subject of an enormous personality cult. He was seen as the perfect embodiment of German manly honour, rectitude, decency and strength. The appeal of the Hindenburg cult cut across ideological, religious, class and regional lines, but the group that idolized Hindenburg the most were the German right who saw him as an ideal representative of the Prussian ethos and of Lutheran, Junker

Junker

A Junker was a member of the landed nobility of Prussia and eastern Germany. These families were mostly part of the German Uradel and carried on the colonization and Christianization of the northeastern European territories during the medieval Ostsiedlung. The abbreviation of Junker is Jkr...

values. During the war, there were wooden statues of Hindenburg built all over Germany, onto which people nailed money and cheques for war bonds. It was a measure of Hindenburg's public appeal that when the Government launched an all-out programme of industrial mobilisation in 1916, the programme was named the Hindenburg Programme. Before 1914, any such programme would have been named the Kaiser Wilhelm Programme.

By the summer of 1916 Erich von Falkenhayn

Erich von Falkenhayn

Erich von Falkenhayn was a German soldier and Chief of the General Staff during World War I. He became a military writer after World War I.-Early life:...

had been discredited by the bogging-down of the Verdun Offensive and the near-collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army caused by the Brusilov Offensive

Brusilov Offensive

The Brusilov Offensive , also known as the June Advance, was the Russian Empire's greatest feat of arms during World War I, and among the most lethal battles in world history. Prof. Graydon A. Tunstall of the University of South Florida called the Brusilov Offensive of 1916 the worst crisis of...

and the entry of Romania into the war on the Allied side. In August Hindenburg succeeded him as Chief of the General Staff, although real power was exercised by his deputy, Erich Ludendorff

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff was a German general, victor of Liège and of the Battle of Tannenberg...

. Hindenburg in many ways served as the real commander-in-chief of the German armed forces instead of the Kaiser who had been reduced to a mere figurehead while Ludendorff served as the de facto general chief of staff. From 1916 onwards, Germany became an unofficial military dictatorship, often called the "Silent dictatorship" by historians.

In September 1918, Ludendorff advised seeking an armistice

Armistice

An armistice is a situation in a war where the warring parties agree to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, but may be just a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace...

with the Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

, but in October, changed his mind and resigned in protest. Ludendorff had expected Hindenburg to follow him by also resigning, but Hindenburg refused on the grounds that in this hour of crisis, he could not desert the men under his command. Ludendorff never forgave Hindenburg for this. Ludendorff was succeeded by Wilhelm Groener

Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener was a German soldier and politician.-Biography:He was born in Ludwigsburg in the Kingdom of Württemberg, the son of a regimental paymaster. He entered the Württemberg Army in 1884, and attended the War Academy from 1893 to 1897, whereupon he was appointed to the General...

, a staff officer who served as Hindenburg's assistant until 1932. In November 1918, Hindenburg and Groener played a decisive role in persuading the Kaiser Wilhelm II

William II, German Emperor

Wilhelm II was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia, ruling the German Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia from 15 June 1888 to 9 November 1918. He was a grandson of the British Queen Victoria and related to many monarchs and princes of Europe...

to abdicate for the greater good of Germany.

Hindenburg, who was a firm monarchist throughout his life, always regarded this episode with considerable embarrassment, and almost from the moment the Kaiser abdicated, Hindenburg insisted that he had played no role in the abdication and assigned all of the blame to Groener. Groener, for his part, went along in order to protect Hindenburg's reputation

Aftermath of the war

At the conclusion of the war, Hindenburg retired a second time, and announced his intention to retire from public life. In 1919, Hindenburg was called before a ReichstagReichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

Commission that was investigating the responsibility for both the outbreak of war in 1914 and for the defeat in 1918.

Hindenburg had not wanted to appear before the commission, and had been subpoena

Subpoena

A subpoena is a writ by a government agency, most often a court, that has authority to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of subpoena:...

ed. The appearance of Hindenburg before the commission was an eagerly awaited public event. Ludendorff, who had fallen out with Hindenburg over the decision to continue seeking the armistice in October 1918, was concerned that Hindenburg might reveal that it was he who had advised seeking an armistice in September 1918. Ludendorff wrote a letter to Hindenburg, informing him that he was writing his memoirs and threatened to expose the fact that Hindenburg did not deserve the credit that he had received for his victories. Ludendorff's letter went on to suggest that how Hindenburg testified would determine how favorably Ludendorff would present Hindenburg in his memoirs.

When Hindenburg did appear before the commission, he refused to answer any questions about the responsibility for the German defeat, and instead read out a prepared statement that had been reviewed in advance by Ludendorff's lawyer. Hindenburg testified that the German Army had been on the verge of winning the war in the autumn of 1918, and that the defeat had been precipitated by a Dolchstoß ("stab in the back") by disloyal elements on the home front and by unpatriotic politicians. Despite being threatened with a contempt

Contempt of court

Contempt of court is a court order which, in the context of a court trial or hearing, declares a person or organization to have disobeyed or been disrespectful of the court's authority...

citation for refusing to respond to questions, Hindenburg simply walked out of the hearings after reading his statement. Hindenburg's status as a war hero provided him with a political shield and he was never prosecuted.

Hindenburg's testimony was the first use of the Dolchstoßlegende. The field marshal credited an unnamed British general for first uttering the phrase, and the term was adopted by nationalist and conservative politicians who sought to blame the socialist founders of the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

for the loss of the war.

Afterwards, Hindenburg had his memoirs entitled Mein Leben (My Life) ghost-written in 1919–20. Mein Leben was a huge bestseller in Germany, but was dismissed by most military historians and critics as a boring apologia that skipped over the most controversial issues in Hindenburg's life. Afterwards, Hindenburg retired from most public appearances and spent most of his time with his family. A widower, Hindenburg was very close to his only son, Major Oskar von Hindenburg

Oskar von Hindenburg

Generalleutnant Oskar von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg was the politically powerful son and aide-de-camp to Field Marshal and President of Germany Paul von Hindenburg....

and his granddaughters.

1925 election

German presidential election, 1925

The presidential election of 1925 was the first direct election to the office of President of the Reich , Germany's head of state during the 1919-1933 Weimar Republic. The first President, Friedrich Ebert, died on 28 February, 1925...

held on 29 March 1925, no candidate had emerged with a majority and a run-off election had been called. The Social Democratic

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

candidate, Prime Minister Otto Braun

Otto Braun

This article is about the Prime Minister of Prussia. For the German Communist and once the Comintern military adviser to the Chinese Communist revolution see Otto Braun ....

of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, had agreed to drop out of the race and had endorsed the Catholic Centre Party's candidate, Wilhelm Marx

Wilhelm Marx

Wilhelm Marx was a German lawyer, Catholic politician and a member of the Centre Party. He was Chancellor of the German Reich twice, from 1923 to 1925 and again from 1926 to 1928, and also served briefly as minister president of Prussia in 1925, during the Weimar Republic.-Life:Born in Cologne to...

. Since Karl Jarres

Karl Jarres

Karl Jarres was a politician of the German People's Party during the Weimar Republic. Jarres was born in the city of Remscheid. Rhenish Prussia, and after legal studies in Bonn as a young adult, pursued an administrative career...

, the joint candidate of the two conservative parties, the German People's Party

German People's Party

The German People's Party was a national liberal party in Weimar Germany and a successor to the National Liberal Party of the German Empire.-Ideology:...

(DVP) and the German National People's Party

German National People's Party

The German National People's Party was a national conservative party in Germany during the time of the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the NSDAP it was the main nationalist party in Weimar Germany composed of nationalists, reactionary monarchists, völkisch, and antisemitic elements, and...

(DNVP), was regarded as too dull, it seemed likely that Marx would win. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred von Tirpitz was a German Admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussia never had a major navy, nor did the other German states before the German Empire was formed in 1871...

, one of the leaders of the DNVP, visited Hindenburg and urged him to run.

Hindenburg initially demurred, but under strong pressure from Tirpitz applied over several meetings, broke down and agreed to run. Though Hindenburg ran during the second round of the elections as a non-party independent, he was generally regarded as the conservative candidate. Largely because of his status as Germany's greatest war hero, Hindenburg won the election in the second round of voting held on 26 April 1925. He was aided by the support of the Bavarian People's Party

Bavarian People's Party

The Bavarian People's Party was the Bavarian branch of the Centre Party, which broke off from the rest of the party in 1919 to pursue a more conservative, more Catholic, more Bavarian particularist course...

(BVP), which switched from supporting Marx, and the refusal of the Communist Party of Germany

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

(KPD) to withdraw its candidate, Ernst Thälmann

Ernst Thälmann

Ernst Thälmann was the leader of the Communist Party of Germany during much of the Weimar Republic. He was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 and held in solitary confinement for eleven years, before being shot in Buchenwald on Adolf Hitler's orders in 1944...

(if either had supported Marx he would have won).

First term

Weimar constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich , usually known as the Weimar Constitution was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic...

seriously. In 1927 he shocked the international opinion by his statements defending Germany's actions and entry in World War I, when he declared that it entered the war as "the means of self-assertion against a world full of enemies. Pure in heart we set off to the defence of the fatherland and with clean hands the German army carried the sword."

In private, Hindenburg often complained that he missed the quiet of his retirement and bemoaned that he had allowed himself to be pressured into running for President. Hindenburg carped that politics was full of issues such as economics that he did not, and did not want to, understand. He was surrounded, however, by a coterie of advisers antipathetic to the Weimar constitution. These advisers included his son, Oskar

Oskar von Hindenburg

Generalleutnant Oskar von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg was the politically powerful son and aide-de-camp to Field Marshal and President of Germany Paul von Hindenburg....

, Otto Meißner

Otto Meißner

Otto Meißner was head of the Office of the President of Germany during the entire period of the Weimar Republic under Friedrich Ebert and Paul von Hindenburg and, finally, at the beginning of the Nazi era under Adolf Hitler.-Life:The son of a postal official, Meißner studied law in Strasbourg from...

, General Wilhelm Groener

Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener was a German soldier and politician.-Biography:He was born in Ludwigsburg in the Kingdom of Württemberg, the son of a regimental paymaster. He entered the Württemberg Army in 1884, and attended the War Academy from 1893 to 1897, whereupon he was appointed to the General...

, and General Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt von Schleicher was a German general and the last Chancellor of Germany during the era of the Weimar Republic. Seventeen months after his resignation, he was assassinated by order of his successor, Adolf Hitler, in the Night of the Long Knives....

. This group were known as the Kamarilla

Camarilla

Camarilla may refer to:*Camarilla, an unofficial group of courtiers or favorites surrounding and influencing a king or ruler, specifically the two such groups prominent in German history....

.

The younger Hindenburg served as his father's aide-de-camp

Aide-de-camp

An aide-de-camp is a personal assistant, secretary, or adjutant to a person of high rank, usually a senior military officer or a head of state...

and controlled politicians' access to the President.

Schleicher was a close friend of Oskar and came to enjoy privileged access to Hindenburg. It was he who came up with the idea of Presidential government based on the so-called "25/48/53 formula". Under a "Presidential" government the head of government

Head of government

Head of government is the chief officer of the executive branch of a government, often presiding over a cabinet. In a parliamentary system, the head of government is often styled prime minister, chief minister, premier, etc...

(in this case, the chancellor

Chancellor

Chancellor is the title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the Cancellarii of Roman courts of justice—ushers who sat at the cancelli or lattice work screens of a basilica or law court, which separated the judge and counsel from the...

), is responsible to the head of state

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

, and not a legislative body. The "25/48/53 formula" referred to the three articles of the Constitution that could make a "Presidential government" possible:

- Article 25 allowed the President to dissolve the Reichstag.

- Article 48 allowed the President to sign into law emergency bills without the consent of the Reichstag. However, the Reichstag could cancel any law passed by Article 48 by a simple majority within sixty days of its passage.

- Article 53 allowed the President to appoint the Chancellor.

Schleicher's idea was to have Hindenburg appoint a man of Schleicher's choosing as chancellor, who would rule under the provisions of Article 48. If the Reichstag

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

should threaten to annul any laws so passed, Hindenburg could counter with the threat of dissolution

Dissolution of parliament

In parliamentary systems, a dissolution of parliament is the dispersal of a legislature at the call of an election.Usually there is a maximum length of a legislature, and a dissolution must happen before the maximum time...

. Hindenburg was unenthusiastic about these plans, but was pressured into going along with them by his son along with Meißner, Groener and Schleicher.

Presidential government

Heinrich Brüning