List of cultural references in The Divine Comedy

Encyclopedia

Dante Alighieri

Durante degli Alighieri, mononymously referred to as Dante , was an Italian poet, prose writer, literary theorist, moral philosopher, and political thinker. He is best known for the monumental epic poem La commedia, later named La divina commedia ...

is a long allegorical poem in three parts (or canticas): the Inferno

Inferno (Dante)

Inferno is the first part of Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. It is an allegory telling of the journey of Dante through what is largely the medieval concept of Hell, guided by the Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as...

(Hell

Hell

In many religious traditions, a hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as endless. Religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations...

), Purgatorio

Purgatorio

Purgatorio is the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno, and preceding the Paradiso. The poem was written in the early 14th century. It is an allegory telling of the climb of Dante up the Mount of Purgatory, guided by the Roman poet Virgil...

(Purgatory

Purgatory

Purgatory is the condition or process of purification or temporary punishment in which, it is believed, the souls of those who die in a state of grace are made ready for Heaven...

), and Paradiso

Paradiso (Dante)

Paradiso is the third and final part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and the Purgatorio. It is an allegory telling of Dante's journey through Heaven, guided by Beatrice, who symbolises theology...

(Paradise

Paradise

Paradise is a place in which existence is positive, harmonious and timeless. It is conceptually a counter-image of the miseries of human civilization, and in paradise there is only peace, prosperity, and happiness. Paradise is a place of contentment, but it is not necessarily a land of luxury and...

), and 100 canto

Canto

The canto is a principal form of division in a long poem, especially the epic. The word comes from Italian, meaning "song" or singing. Famous examples of epic poetry which employ the canto division are Lord Byron's Don Juan, Valmiki's Ramayana , Dante's The Divine Comedy , and Ezra Pound's The...

s, with the Inferno having 34, Purgatorio having 33, and Paradiso having 33 cantos. Set at Easter

Easter

Easter is the central feast in the Christian liturgical year. According to the Canonical gospels, Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion. His resurrection is celebrated on Easter Day or Easter Sunday...

1300, the poem describes the living poet's journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise.

Throughout the poem, Dante refers to people and events from Classical

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

and Biblical history and mythology

Mythology

The term mythology can refer either to the study of myths, or to a body or collection of myths. As examples, comparative mythology is the study of connections between myths from different cultures, whereas Greek mythology is the body of myths from ancient Greece...

, the history of Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

, and the Europe of the Medieval period up to and including his own day. A knowledge of at least the most important of these references can aid in understanding the poem fully.

For ease of reference, the cantica names are abbreviated to Inf., Purg., and Par. Roman numerals

Roman numerals

The numeral system of ancient Rome, or Roman numerals, uses combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet to signify values. The numbers 1 to 10 can be expressed in Roman numerals as:...

are used to identify cantos and Arabic numerals to identify lines. This means that Inf. X, 123 refers to line 123 in Canto X (or 10) of the Inferno and Par. XXV, 27 refers to line 27 in Canto XXV (or 25) of the Paradiso. The line numbers refer to the original Italian text.

Boldface links indicate that the word or phrase has an entry in the list. Following that link will present that entry.

| : |

|---|

A

- Abbagliato: See Spendthrift Club.

- Abel: BiblicalBibleThe Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

second son of Adam and brother of Cain.- Raised by Jesus from Limbo into ParadiseParadiseParadise is a place in which existence is positive, harmonious and timeless. It is conceptually a counter-image of the miseries of human civilization, and in paradise there is only peace, prosperity, and happiness. Paradise is a place of contentment, but it is not necessarily a land of luxury and...

. Inf. IV, 56.

- Raised by Jesus from Limbo into Paradise

- Abraham the PatriarchAbrahamAbraham , whose birth name was Abram, is the eponym of the Abrahamic religions, among which are Judaism, Christianity and Islam...

: Important biblical figure.- Raised by Jesus from Limbo into ParadiseParadiseParadise is a place in which existence is positive, harmonious and timeless. It is conceptually a counter-image of the miseries of human civilization, and in paradise there is only peace, prosperity, and happiness. Paradise is a place of contentment, but it is not necessarily a land of luxury and...

. Inf. IV, 58.

- Raised by Jesus from Limbo into Paradise

- AbsalomAbsalomAccording to the Bible, Absalom or Avshalom was the third son of David, King of Israel with Maachah, daughter of Talmai, King of Geshur. describes him as the most handsome man in the kingdom...

and AhitophelAhitophelAhitophel was a counselor of King David and a man greatly renowned for his sagacity. At the time of Absalom's revolt he deserted David and espoused the cause of Absalom ....

: Absalom was the rebellious son of King David who was incited by Ahitophel, the king's councilor.- Bertran de Born compares his fomenting with the "malicious urgings" of Ahitophel. Inf. XXVIII, 136–8.

- AcheronAcheronThe Acheron is a river located in the Epirus region of northwest Greece. It flows into the Ionian Sea in Ammoudia, near Parga.-In mythology:...

: The mythological GreekGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

underworld river over which Charon ferried souls of the newly dead into HadesHadesHades , Hadēs, originally , Haidēs or , Aidēs , meaning "the unseen") was the ancient Greek god of the underworld. The genitive , Haidou, was an elision to denote locality: "[the house/dominion] of Hades". Eventually, the nominative came to designate the abode of the dead.In Greek mythology, Hades...

.- The "melancholy shore" encountered. Inf. III, 71–8.

- Formed from the tears of the statue of the Old Man of Crete. Inf. XIV, 94–116.

- AchillesAchillesIn Greek mythology, Achilles was a Greek hero of the Trojan War, the central character and the greatest warrior of Homer's Iliad.Plato named Achilles the handsomest of the heroes assembled against Troy....

: The greatest Greek hero in the Trojan WarTroyTroy was a city, both factual and legendary, located in northwest Anatolia in what is now Turkey, southeast of the Dardanelles and beside Mount Ida...

. Although Homer has him die in battle after killing Hector, another account well known in the Middle AgesMiddle AgesThe Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

has him killed by Paris after having been lured with the promise of Priam's daughter Polyxena.- Found amongst the sexual sinners. Inf. V, 65.

- Remembered by Virgil for having been educated by Chiron. Inf. XII, 71.

- His abadonment of Deidamia and his only son, at the urging of Ulysses, to go to the war against Troy. Inf. XXVI, 61–2.

- Acre: Ancient city in Western GalileeGalileeGalilee , is a large region in northern Israel which overlaps with much of the administrative North District of the country. Traditionally divided into Upper Galilee , Lower Galilee , and Western Galilee , extending from Dan to the north, at the base of Mount Hermon, along Mount Lebanon to the...

, it was the last Christian possession in the Holy LandHoly LandThe Holy Land is a term which in Judaism refers to the Kingdom of Israel as defined in the Tanakh. For Jews, the Land's identifiction of being Holy is defined in Judaism by its differentiation from other lands by virtue of the practice of Judaism often possible only in the Land of Israel...

, finally lost in 1291. Inf. XXVII, 86. - AdamAdam and EveAdam and Eve were, according to the Genesis creation narratives, the first human couple to inhabit Earth, created by YHWH, the God of the ancient Hebrews...

: According to the Bible, the first man created by God.- His "evil seed". Inf. III, 115–7.

- Our "first parent", raised by Jesus from Limbo into ParadiseParadiseParadise is a place in which existence is positive, harmonious and timeless. It is conceptually a counter-image of the miseries of human civilization, and in paradise there is only peace, prosperity, and happiness. Paradise is a place of contentment, but it is not necessarily a land of luxury and...

. Inf. IV, 55.

- Adam of Brescia: See Master Adam.

- AeginaAeginaAegina is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of Aeacus, who was born in and ruled the island. During ancient times, Aegina was a rival to Athens, the great sea power of the era.-Municipality:The municipality...

: A Greek island between AtticaAtticaAttica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

and ArgolisArgolisArgolis is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Peloponnese. It is situated in the eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula.-Geography:...

in the Saronic GulfSaronic GulfThe Saronic Gulf or Gulf of Aegina in Greece forms part of the Aegean Sea and defines the eastern side of the isthmus of Corinth. It is the eastern terminus of the Corinth Canal, which cuts across the isthmus.-Geography:The gulf includes the islands of; Aegina, Salamis, and Poros along with...

. According to tradition it was named by its ruler AeacusAeacusAeacus was a mythological king of the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf.He was son of Zeus and Aegina, a daughter of the river-god Asopus. He was born on the island of Oenone or Oenopia, to which Aegina had been carried by Zeus to secure her from the anger of her parents, and whence this...

— son of Zeus and AeginaAegina (mythology)Aegina was a figure of Greek mythology, the nymph of the island that bears her name, Aegina, lying in the Saronic Gulf between Attica and the Peloponnesos. The archaic Temple of Aphaea, the "Invisible Goddess", on the island was later subsumed by the cult of Athena...

, daughter of the river-god AsopusAsopusAsopus or Asôpos is the name of four different rivers in Greece and one in Turkey. In Greek mythology, it was the name of the gods of those rivers.-The rivers in Greece:...

— after his mother. In Ovid's Metamorphoses (VII, 501–660), Aeacus, tells of a terrible plague inflicted by a jealous JunoJuno (mythology)Juno is an ancient Roman goddess, the protector and special counselor of the state. She is a daughter of Saturn and sister of the chief god Jupiter and the mother of Mars and Vulcan. Juno also looked after the women of Rome. Her Greek equivalent is Hera...

(Hera), killing everyone on the island but Aeacus; and how he begged Jupiter (Zeus) to give him back his people or take his life as well. Jupiter then turned the islands ants into a race of men called the MyrmidonsMyrmidonsThe Myrmidons or Myrmidones were legendary people of Greek history. They were very brave and skilled warriors commanded by Achilles, as described in Homer's Iliad. Their eponymous ancestor was Myrmidon, a king of Thessalian Phthia, who was the son of Zeus and "wide-ruling" Eurymedousa, a...

, some of whom Achilles ultimately led to war against Troy.- "… all Aegina's people sick … when the air was so infected … received their health again through seed of ants.", compared with "the spirits languishing in scattered heaps" of the tenth Malebolge. Inf. XXIX, 58–65.

- AeneasAeneasAeneas , in Greco-Roman mythology, was a Trojan hero, the son of the prince Anchises and the goddess Aphrodite. His father was the second cousin of King Priam of Troy, making Aeneas Priam's second cousin, once removed. The journey of Aeneas from Troy , which led to the founding a hamlet south of...

: Hero of Virgil's epic poem AeneidAeneidThe Aeneid is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. It is composed of roughly 10,000 lines in dactylic hexameter...

, his descent into hell is a primary source for Dante's own journey.- Son of Anchises, fled the fall of Troy. Inf. I, 74–5.

- "Father of SylviusSilvius (mythology)In Roman mythology, Silvius was either the son of Aeneas and Lavinia or the son of Ascanius. He succeeded Ascanius as King of Alba Longa.According to the former tradition, upon the death of Aeneas, Lavinia is said to have hidden in a forest from the fear that Ascanius would harm the child...

", journey to HadesHadesHades , Hadēs, originally , Haidēs or , Aidēs , meaning "the unseen") was the ancient Greek god of the underworld. The genitive , Haidou, was an elision to denote locality: "[the house/dominion] of Hades". Eventually, the nominative came to designate the abode of the dead.In Greek mythology, Hades...

, founder of Rome. Inf. II, 13–27. - When Dante doubts he has the qualities for his great voyage, he tells Virgil "I am no Aeneas, no Paul". Inf. II, 32

- Seen in Limbo. Inf. IV, 122.

- "Rome's noble seed". Inf. XXVI. 60.

- Founder of GaetaGaetaGaeta is a city and comune in the province of Latina, in Lazio, central Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is 120 km from Rome and 80 km from Naples....

. Inf. XXVI, 93.

- AesopAesopAesop was a Greek writer credited with a number of popular fables. Older spellings of his name have included Esop and Isope. Although his existence remains uncertain and no writings by him survive, numerous tales credited to him were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a...

: A semi-legendary Greek fabulist of whom little reliable is known. A famous corpus of fablesAesop's FablesAesop's Fables or the Aesopica are a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and story-teller believed to have lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 560 BCE. The fables remain a popular choice for moral education of children today...

is traditionally assigned to him.- His fable of the Frog and the mouse is mentioned. Inf. XXIII, 4–6.

- AhitophelAhitophelAhitophel was a counselor of King David and a man greatly renowned for his sagacity. At the time of Absalom's revolt he deserted David and espoused the cause of Absalom ....

: See Absalom.- Cited as his own analogy by Bertran de Born. Inf. XXVIII, 137.

- Alardo: See Tagliacozzo.

- Alberto da Casalodi: Guelph count of BresciaBresciaBrescia is a city and comune in the region of Lombardy in northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, between the Mella and the Naviglio, with a population of around 197,000. It is the second largest city in Lombardy, after the capital, Milan...

, he was SignoreSignoriaA Signoria was an abstract noun meaning 'government; governing authority; de facto sovereignty; lordship in many of the Italian city states during the medieval and renaissance periods....

of Mantua during the feuding between Guelphs and Ghibellins. He was ousted in 1273 by his advisor Pinamonte dei Bonacolsi.- His foolishness ("la mattia da Casalodi") in trusting Pinamonte. Inf. XX, 95–6.

- Alberto da Siena: See Griffolino of Arezzo.

- Albertus MagnusAlbertus MagnusAlbertus Magnus, O.P. , also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. He was a German Dominican friar and a bishop, who achieved fame for his comprehensive knowledge of and advocacy for the peaceful coexistence of science and religion. Those such as James A. Weisheipl...

(c.1197–1280): DominicanDominican OrderThe Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

friarFriarA friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders.-Friars and monks:...

, scholar, and teacher of Thomas Aquinas.- Standing to the right of Thomas Aquinas in the sphere of the Sun. Par. X, 98-9.

- Tegghiaio Aldobrandi: Florentine son of the famous Aldobrando degli Adimari, he was podestàPodestàPodestà is the name given to certain high officials in many Italian cities, since the later Middle Ages, mainly as Chief magistrate of a city state , but also as a local administrator, the representative of the Emperor.The term derives from the Latin word potestas, meaning power...

of ArezzoArezzoArezzo is a city and comune in Central Italy, capital of the province of the same name, located in Tuscany. Arezzo is about 80 km southeast of Florence, at an elevation of 296 m above sea level. In 2011 the population was about 100,000....

in 1256 and fought at the battle of MontapertiBattle of MontapertiThe Battle of Montaperti was fought on September 4, 1260, between Florence and Siena in Tuscany as part of the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines...

in 1260, where his warnings against attacking the SeneseSienaSiena is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.The historic centre of Siena has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It is one of the nation's most visited tourist attractions, with over 163,000 international arrivals in 2008...

forces went unheeded, and the Florentines were annihilated.- One of a group of famous political Florentines, "who were so worthy … whose minds bent toward the good", asked about by Dante of Ciacco. Inf. VI, 77–81.

- One of a group of three Florentine sodomites who approach Dante, and are much esteemed by him (see Jacopo Rusticucci). Inf. XVI, 1–90.

- Cryptically described as he, "la cui voce nel mondo sù dovria esser gradita" ("whose voice the world above should have valued"), probably an allusion to his councils at Montaperti. Inf. XVI, 40–2.

- AlectoAlectoAlecto is one of the Erinyes in Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, she was the daughter of Gaea fertilized by the blood spilled from Uranus when Cronus castrated him. She is the sister of Tisiphone and Megaera...

: see Erinyes. - Alexander the Great: King of MacedonMacedonMacedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

(336 BCE–323 BCE) and the most successful military commander of ancient history- Probably the tyrantTyrantA tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

pointed out by Nessus. Inf. XII, 107. - Apocryphal story of his adventures in India provide a simile for the punishment of the violent against god in Inf. XIV, 31–36.

- Probably the tyrant

- AliAli' |Ramaḍān]], 40 AH; approximately October 23, 598 or 600 or March 17, 599 – January 27, 661).His father's name was Abu Talib. Ali was also the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and ruled over the Islamic Caliphate from 656 to 661, and was the first male convert to Islam...

: Cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, and one of his first followers. Disputes over Ali's succession as leader of Islam led to the split of IslamIslamIslam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

into the sects of Sunni and Shi'a.- He "walks and weeps" in front of Muhammed. Inf. XXVIII, 31–3.

- AmphiarausAmphiarausIn Greek mythology, Amphiaraus was the son of Oecles and Hypermnestra, and husband of Eriphyle. Amphiaraus was the King of Argos along with Adrastus— the brother of Amphiaraus' wife, Eriphyle— and Iphis. Amphiaraus was a seer, and greatly honored in his time...

: MythicalGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

king of ArgosArgosArgos is a city and a former municipality in Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Argos-Mykines, of which it is a municipal unit. It is 11 kilometres from Nafplion, which was its historic harbour...

and seer, who although he had foreseen his death, was persuaded to join the Seven against ThebesSeven Against ThebesThe Seven against Thebes is the third play in an Oedipus-themed trilogy produced by Aeschylus in 467 BC. The trilogy is sometimes referred to as the Oedipodea. It concerns the battle between an Argive army led by Polynices and the army of Thebes led by Eteocles and his supporters. The trilogy won...

expedition. He was killed while fleeing from pursuers, when Zeus threw a thunderbolt, and the earth opened up and swallowed him.- The story of his death is told. Inf. XX, 31–9.

- Pope Anastasius IIPope Anastasius IIPope Anastasius II was pope from November 24, 496 to November 16, 498.Anastasius II was Pontiff in the time of the schism of Acacius. He showed some tendency towards conciliation, and thus brought upon himself the lively reproaches of the author of the Liber Pontificalis. On the strength of this...

: Pope who Dante perhaps mistakenly identified with the emperor Anastasius IAnastasius I (emperor)Anastasius I was Byzantine Emperor from 491 to 518. During his reign the Roman eastern frontier underwent extensive re-fortification, including the construction of Dara, a stronghold intended to counter the Persian fortress of Nisibis....

and thus condemned to hell as a heretic. Anastasius I was a supporter of MonophysitismMonophysitismMonophysitism , or Monophysiticism, is the Christological position that Jesus Christ has only one nature, his humanity being absorbed by his Deity...

, a heresy which denied the dual divine/human nature of Jesus.- Dante and Virgil take shelter behind Anastasius' tomb and discuss matters of theologyTheologyTheology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

. Inf XI, 4–111.

- Dante and Virgil take shelter behind Anastasius' tomb and discuss matters of theology

- AnaxagorasAnaxagorasAnaxagoras was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae in Asia Minor, Anaxagoras was the first philosopher to bring philosophy from Ionia to Athens. He attempted to give a scientific account of eclipses, meteors, rainbows, and the sun, which he described as a fiery mass larger than...

(c. 500 BCE–428 BCE): GreekAncient GreeceAncient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

philosopher.- Encountered by Dante in Limbo. Inf. IV, 137.

- AnchisesAnchisesIn Greek mythology, Anchises was the son of Capys and Themiste . His major claim to fame in Greek mythology is that he was a mortal lover of the goddess Aphrodite . One version is that Aphrodite pretended to be a Phrygian princess and seduced him for nearly two weeks of lovemaking...

: Father of Aeneas by AphroditeAphroditeAphrodite is the Greek goddess of love, beauty, pleasure, and procreation.Her Roman equivalent is the goddess .Historically, her cult in Greece was imported from, or influenced by, the cult of Astarte in Phoenicia....

. In the AeneidAeneidThe Aeneid is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. It is composed of roughly 10,000 lines in dactylic hexameter...

he is shown as dying in SicilySicilySicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

.- Father of Aeneas. Inf. I, 74.

- Loderingo AndalòLoderingo AndalòLoderingo Andalò was an Italian nobleman from a Bolognese Ghibelline family. He held many important civic positions and founded the Knights of Saint Mary in 1261. Loderingo was the brother of Diana, who founded the Dominican Monastery of Saint Agnes...

(c. 1210–1293): Of a prominent Ghibelline family, he held many civic positions. In 1261 he founded the Knights of Saint MaryKnights of Saint MaryThe Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary , also called the Order of Saint Mary of the Tower or the Order of the Knights of the Mother of God, commonly the Knights of Saint Mary, was a military order founded in 1261 when it received its rule from Pope Urban IV, who expressly states the purpose of the...

or Jovial Friars, a religious order recognized by Pope Clement IVPope Clement IVPope Clement IV , born Gui Faucoi called in later life le Gros , was elected Pope February 5, 1265, in a conclave held at Perugia that took four months, while cardinals argued over whether to call in Charles of Anjou, the youngest brother of Louis IX of France...

. Its mission was to promote peace between warring municipal factions, but its members soon succumbed to self interest. Together with Catalano dei Malavolti, he shared the position of governor of Florence. Loderingo is extolled for his fortitude in dying by his friend, the poet Guittone d'ArezzoGuittone d'ArezzoGuittone d'Arezzo was a Tuscan poet and the founder of the Tuscan School. He was an acclaimed secular love poet before his conversion in the 1260s, when he became a religious poet. In 1256, he was exiled from Arezzo due to his Guelf sympathies....

.- Among the hypocrites. Inf. XXIII, 103–9.

- Andrea de' Mozzi: Chaplain of the popes Alexander IVPope Alexander IVPope Alexander IV was Pope from 1254 until his death.Born as Rinaldo di Jenne, in Jenne , he was, on his mother's side, a member of the de' Conti di Segni family, the counts of Segni, like Pope Innocent III and Pope Gregory IX...

and Gregory IXPope Gregory IXPope Gregory IX, born Ugolino di Conti, was pope from March 19, 1227 to August 22, 1241.The successor of Pope Honorius III , he fully inherited the traditions of Pope Gregory VII and of his uncle Pope Innocent III , and zealously continued their policy of Papal supremacy.-Early life:Ugolino was...

, he was made bishop of Florence in 1287 and there remained till 1295, when he was moved to VicenzaVicenzaVicenza , a city in north-eastern Italy, is the capital of the eponymous province in the Veneto region, at the northern base of the Monte Berico, straddling the Bacchiglione...

, only to die shortly after.- One of a group of sodomitesSodomySodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

identified by Brunetto Latini to Dante. Brunetto (i.e. Dante) blasts him with particular harshness, calling him "tigna". Inf. XV, 110–4.

- One of a group of sodomites

- Angiolello di Carignano: See Malatestino.

- AnnasAnnasAnnas [also Ananus or Ananias], son of Seth , was appointed by the Roman legate Quirinius as the first High Priest of the newly formed Roman province of Iudaea in 6 AD; just after the Romans had deposed Archelaus, Ethnarch of Judaea, thereby putting Judaea directly under Roman rule.Annas officially...

: The father-in-law of Caiaphas, he also is called High-Priest. He appears to have been president of the SanhedrinSanhedrinThe Sanhedrin was an assembly of twenty-three judges appointed in every city in the Biblical Land of Israel.The Great Sanhedrin was the supreme court of ancient Israel made of 71 members...

before which Jesus is said to have been brought.- Among the hypocrites, he suffers the same punishment as Caiaphas. Inf. XXIII, 121–2.

- Antiochus IV EpiphanesAntiochus IV EpiphanesAntiochus IV Epiphanes ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. He was a son of King Antiochus III the Great. His original name was Mithridates; he assumed the name Antiochus after he ascended the throne....

(c. 215–163 BCE): Last powerful SeleucidSeleucid EmpireThe Seleucid Empire was a Greek-Macedonian state that was created out of the eastern conquests of Alexander the Great. At the height of its power, it included central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, today's Turkmenistan, Pamir and parts of Pakistan.The Seleucid Empire was a major centre...

king, he is famous principally for his war against the MaccabeesMaccabeesThe Maccabees were a Jewish rebel army who took control of Judea, which had been a client state of the Seleucid Empire. They founded the Hasmonean dynasty, which ruled from 164 BCE to 63 BCE, reasserting the Jewish religion, expanding the boundaries of the Land of Israel and reducing the influence...

.- Just as he "sold" the High Priesthood to Jason, Philip IV of France "sold" the papacy to Clement V. Inf. XIX, 86–7.

- ApuliaApuliaApulia is a region in Southern Italy bordering the Adriatic Sea in the east, the Ionian Sea to the southeast, and the Strait of Òtranto and Gulf of Taranto in the south. Its most southern portion, known as Salento peninsula, forms a high heel on the "boot" of Italy. The region comprises , and...

: A region in southeastern Italy bordering the Adriatic SeaAdriatic SeaThe Adriatic Sea is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan peninsula, and the system of the Apennine Mountains from that of the Dinaric Alps and adjacent ranges...

in the east, the Ionian SeaIonian SeaThe Ionian Sea , is an arm of the Mediterranean Sea, south of the Adriatic Sea. It is bounded by southern Italy including Calabria, Sicily and the Salento peninsula to the west, southern Albania to the north, and a large number of Greek islands, including Corfu, Zante, Kephalonia, Ithaka, and...

to the southeast, and the Strait of Otranto and Gulf of Taranto in the south. In the Middle Ages, it referred to all of southern Italy. The barons of Apulia broke their promise to defend the strategic pass at Ceperano for Manfred of SicilyManfred of SicilyManfred was the King of Sicily from 1258 to 1266. He was a natural son of the emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen but his mother, Bianca Lancia , is reported by Matthew of Paris to have been married to the emperor while on her deathbed.-Background:Manfred was born in Venosa...

the son of Frederick II, and allowed Charles of Anjou to pass freely into NaplesNaplesNaples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

. Manfred was subsequently killed (1266) at the Battle of BeneventoBattle of BeneventoThe Battle of Benevento was fought near Benevento, in present-day Southern Italy, on February 26, 1266, between the troops of Charles of Anjou and Manfred of Sicily. Manfred's defeat and death resulted in the capture of the Kingdom of Sicily by Charles....

, a crucial blow to the Ghibelline cause.- Its "fateful land" as battleground, and Apulia's betrayal. Inf. XXVIII, 7–21.

- AquariusAquarius (constellation)Aquarius is a constellation of the zodiac, situated between Capricornus and Pisces. Its name is Latin for "water-bearer" or "cup-bearer", and its symbol is , a representation of water....

: The eleventh sign of the zodiacZodiacIn astronomy, the zodiac is a circle of twelve 30° divisions of celestial longitude which are centred upon the ecliptic: the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year...

. When the sun is in Aquarius (between January 21 and February 21), the days start to visibly grow longer and day and night begin to approach equal length. Inf. XXIV, 1–3.

- Thomas AquinasThomas AquinasThomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

: DominicanDominican OrderThe Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

theologianTheologyTheology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

considered to be one of the greatest scholars of the Church.- He introduces wise men in the sphere of the Sun. Par. X, 98–138.

- He eulogises St. Francis. Par. XI, 37–117.

- He condemns DominicansDominican OrderThe Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

who have strayed from the true Dominican charism. Par. XI, 124–39.

- ArachneArachneIn Greco-Roman mythology, Arachne was a great mortal weaver who boasted that her skill was greater than that of Minerva, the Latin parallel of Pallas Athena, goddess of wisdom and crafts. Arachne refused to acknowledge that her knowledge came, in part at least, from the goddess. The offended...

: In Greek mythologyGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

, a weaver who challenged AthenaAthenaIn Greek mythology, Athena, Athenê, or Athene , also referred to as Pallas Athena/Athene , is the goddess of wisdom, courage, inspiration, civilization, warfare, strength, strategy, the arts, crafts, justice, and skill. Minerva, Athena's Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is...

to a contest of skill. She hanged herself as a result of shame at her own presumptuousness. - Arcolano of Siena: A member of the Maconi family, he was a member of the notorious Sienese Spendthrift Club. He fought in the battle of Pieve al Toppo in 1288, where according to Giovanni BoccaccioGiovanni BoccaccioGiovanni Boccaccio was an Italian author and poet, a friend, student, and correspondent of Petrarch, an important Renaissance humanist and the author of a number of notable works including the Decameron, On Famous Women, and his poetry in the Italian vernacular...

, he preferred to die in battle rather than live in poverty.- Probably "Lano", one of two spendthrifts (the other being Jacomo da Sant' Andrea) whose punishment consists of being hunted by female hounds. Inf. XIII, 115–29.

- ArethusaArethusa (mythology)For other uses, see ArethusaArethusa means "the waterer". In Greek mythology, she was a nymph and daughter of Nereus , and later became a fountain on the island of Ortygia in Syracuse, Sicily....

: In Greek mythologyGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

she was a nymphNymphA nymph in Greek mythology is a female minor nature deity typically associated with a particular location or landform. Different from gods, nymphs are generally regarded as divine spirits who animate nature, and are usually depicted as beautiful, young nubile maidens who love to dance and sing;...

daughter of NereusNereusIn Greek mythology, Nereus was the eldest son of Pontus and Gaia , a Titan who with Doris fathered the Nereids, with whom Nereus lived in the Aegean Sea. In the Iliad the Old Man of the Sea is the father of Nereids, though Nereus is not directly named...

. Running away from a suitor, Alpheus, she was transformed by ArtemisArtemisArtemis was one of the most widely venerated of the Ancient Greek deities. Her Roman equivalent is Diana. Some scholars believe that the name and indeed the goddess herself was originally pre-Greek. Homer refers to her as Artemis Agrotera, Potnia Theron: "Artemis of the wildland, Mistress of Animals"...

into a fountain.- Her transformation, as described in Ovid's Metamophoses (V, 572–641), is compared to the fate of the thieves. Inf. XXV, 97–9.

- Geryon's adornments, compared to her weavings. Inf. XVII, 14–8.

- Filippo ArgentiFilippo ArgentiFilippo Argenti , a citizen of Florence, was a member of the Cavicciuoli branch of the Adimari family. Filippo's children were: Giovanni Argenti & Salvatore Argenti...

: A Black Guelph and member of the Adimari family, who were enemies of Dante. Inf. VIII, 31–66. - AriadneAriadneAriadne , in Greek mythology, was the daughter of King Minos of Crete, and his queen Pasiphaë, daughter of Helios, the Sun-titan. She aided Theseus in overcoming the Minotaur and was the bride of the god Dionysus.-Minos and Theseus:...

: Daughter of Minos, king of CreteCreteCrete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

, who helped Theseus kill the Minotaur, the offspring of Ariadne's mother PasiphaëPasiphaëIn Greek mythology, Pasiphaë , "wide-shining" was the daughter of Helios, the Sun, by the eldest of the Oceanids, Perse; Like her doublet Europa, her origins were in the East, in her case at Colchis, the palace of the Sun; she was given in marriage to King Minos of Crete. With Minos, she was the...

and a bull.- Referred to as the sister of the Minotaur. Inf. XII, 20.

- AristotleAristotleAristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

: 4th century BCE Greek philosopher whose writings were a major influence on medieval ChristianChristianA Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

scholasticScholasticismScholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

philosophy and theologyTheologyTheology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

, particularly on the works of Thomas Aquinas.- As "il maestro di color che sanno" ("the master of those who know") he is among those encountered by Dante in Limbo Inf. IV, 131.

- His Nicomachean EthicsNicomachean EthicsThe Nicomachean Ethics is the name normally given to Aristotle's best known work on ethics. The English version of the title derives from Greek Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια, transliterated Ethika Nikomacheia, which is sometimes also given in the genitive form as Ἠθικῶν Νικομαχείων, Ethikōn Nikomacheiōn...

quoted by Virgil. Inf. XI, 79–84. - His PhysicsPhysics (Aristotle)The Physics of Aristotle is one of the foundational books of Western science and philosophy...

, referred to by Virgil. Inf. XI, 101–4.

- Argives: People of Argos, or more generally all Greeks Inf. XXVIII, 84.

- ArlesArlesArles is a city and commune in the south of France, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, of which it is a subprefecture, in the former province of Provence....

: City in the south of France and supposed location of the tombs of CharlemagneCharlemagneCharlemagne was King of the Franks from 768 and Emperor of the Romans from 800 to his death in 814. He expanded the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of Western and Central Europe. During his reign, he conquered Italy and was crowned by Pope Leo III on 25 December 800...

's soldiers who fell in the battle of RoncesvallesRoncesvallesRoncesvalles is a small village and municipality in Navarre, northern Spain. It is situated on the small river Urrobi at an altitude of some 900 metres in the Pyrenees, about 8 kilometres from the French frontier....

.- Simile for the tombs in the sixth circle. Inf. IX, 112.

- ArunsPharsaliaThe Pharsalia is a Roman epic poem by the poet Lucan, telling of the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Great...

: In Lucan's epic poem PharsaliaPharsaliaThe Pharsalia is a Roman epic poem by the poet Lucan, telling of the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Great...

, he is the EtruscanEtruscan civilizationEtruscan civilization is the modern English name given to a civilization of ancient Italy in the area corresponding roughly to Tuscany. The ancient Romans called its creators the Tusci or Etrusci...

seer who prophesies the Civil war, Caesar's victory over PompeyPompeyGnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

, and its ending in 48 BCE.- Seen among the seers. Dante mentions his cave, which he locates (erroneously) near LuniLuna (Etruria)Luna was an ancient city of Etruria, Italy, 4~ miles southeast of modern Sarzana. It was the frontier town of Etruria, on the left bank of the river Macra , the boundary in imperial times between Etruria and Liguria...

. Inf. XX, 46–51.

- Seen among the seers. Dante mentions his cave, which he locates (erroneously) near Luni

- Asdente: See Mastro Benvenuto.

- AthamasAthamasThe king of Orchomenus in Greek mythology, Athamas , was married first to the goddess Nephele with whom he had the twins Phrixus or Frixos and Helle. He later divorced Nephele and married Ino, daughter of Cadmus. With Ino, he had two children: Learches and Melicertes...

: See Hera.

- Attila the HunAttila the HunAttila , more frequently referred to as Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in 453. He was leader of the Hunnic Empire, which stretched from the Ural River to the Rhine River and from the Danube River to the Baltic Sea. During his reign he was one of the most feared...

(c. 406–453): King of the HunsHunsThe Huns were a group of nomadic people who, appearing from east of the Volga River, migrated into Europe c. AD 370 and established the vast Hunnic Empire there. Since de Guignes linked them with the Xiongnu, who had been northern neighbours of China 300 years prior to the emergence of the Huns,...

, known in Western tradition as the "Scourge of God".- Pointed out by Nessus. Inf. XII, 133–4.

- Confused by Dante with TotilaTotilaTotila, original name Baduila was King of the Ostrogoths from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of Gothic War, recovering by 543 almost all the territories in Italy that the Eastern Roman Empire had captured from his Kingdom in 540.A relative of...

who destroyed FlorenceFlorenceFlorence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

in 542. Inf. XIII, 149.

- AugustusAugustusAugustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

(63 BCE–14 CE): The Roman EmperorRoman EmperorThe Roman emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period . The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor...

under whom Virgil found fame as a poet.- Called "the good Augustus" by Virgil. Inf. I, 71.

- AverroesAverroes' , better known just as Ibn Rushd , and in European literature as Averroes , was a Muslim polymath; a master of Aristotelian philosophy, Islamic philosophy, Islamic theology, Maliki law and jurisprudence, logic, psychology, politics, Arabic music theory, and the sciences of medicine, astronomy,...

(1126–December 10, 1198): Andalusian-ArabArabArab people, also known as Arabs , are a panethnicity primarily living in the Arab world, which is located in Western Asia and North Africa. They are identified as such on one or more of genealogical, linguistic, or cultural grounds, with tribal affiliations, and intra-tribal relationships playing...

philosopherIslamic philosophyIslamic philosophy is a branch of Islamic studies. It is the continuous search for Hekma in the light of Islamic view of life, universe, ethics, society, and so on...

, physicianPhysicianA physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

, and famous commentator ("il gran comento") on Aristotle.- Encountered by Dante in Limbo. Inf. IV, 144.

- AvicennaAvicennaAbū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā , commonly known as Ibn Sīnā or by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian polymath, who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived...

(980–1037): PersianPersian peopleThe Persian people are part of the Iranian peoples who speak the modern Persian language and closely akin Iranian dialects and languages. The origin of the ethnic Iranian/Persian peoples are traced to the Ancient Iranian peoples, who were part of the ancient Indo-Iranians and themselves part of...

physicianPhysicianA physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

, philosopher, and scientist. He wrote commentaries on Aristotle and Galen.- Encountered by Dante in Limbo. Inf. IV, 143.

- Azzo VIII: Lord of FerraraFerraraFerrara is a city and comune in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital city of the Province of Ferrara. It is situated 50 km north-northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream of the Po River, located 5 km north...

, ModenaModenaModena is a city and comune on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy....

and ReggioReggio EmiliaReggio Emilia is an affluent city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has about 170,000 inhabitants and is the main comune of the Province of Reggio Emilia....

from 1293 until his death in 1308. He was rumoured to have murdered his father Obizzo II d'Este.- The "figliastro" who killed Obizzo. Inf. XII, 112.

B

- BacchusDionysusDionysus was the god of the grape harvest, winemaking and wine, of ritual madness and ecstasy in Greek mythology. His name in Linear B tablets shows he was worshipped from c. 1500—1100 BC by Mycenean Greeks: other traces of Dionysian-type cult have been found in ancient Minoan Crete...

: The RomanRoman mythologyRoman mythology is the body of traditional stories pertaining to ancient Rome's legendary origins and religious system, as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans...

name of the GreekGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

god DionysusDionysusDionysus was the god of the grape harvest, winemaking and wine, of ritual madness and ecstasy in Greek mythology. His name in Linear B tablets shows he was worshipped from c. 1500—1100 BC by Mycenean Greeks: other traces of Dionysian-type cult have been found in ancient Minoan Crete...

, protector of wine.- Born in the ThebesThebes, GreeceThebes is a city in Greece, situated to the north of the Cithaeron range, which divides Boeotia from Attica, and on the southern edge of the Boeotian plain. It played an important role in Greek myth, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus and others...

. Inf. XX, 59.

- Born in the Thebes

- Barrators: Those who have committed the sin of barratry.

- The barrators, are found in the fifth pouch in a lake of boiling pitch guarded by the Malebranche. Inf. XXI–XXII.

- BarratryBarratryBarratry is the name of four legal concepts, three in criminal and civil law, and one in admiralty law.* Barratry, in criminal and civil law, is the act or practice of bringing repeated legal actions solely to harass...

: The sin of selling or paying for offices or positions in the public service or officialdom (cf. simony).- One of the sins of ordinary fraud punished in the eighth circle. Inf. XXI, 60.

- BeatriceBeatrice PortinariBeatrice "Bice" di Folco Portinari was a Florentine woman known as the muse of the poet Dante Alighieri. Beatrice was the principal inspiration for Dante's Vita Nuova, and also appears as his guide in the Divine Comedy in the last book, Paradiso, and in the last four canti of Purgatorio...

(1266–1290): Dante's idealised childhood love, Beatrice Portinari. In the poem, she awaits the poet in Paradise. She symbolised Heavenly Wisdom.- The "worthier spirit" who Virgil says will act as Dante's guide in Paradise. Inf. I, 121–3.

- Asks Virgil to rescue Dante and bring him on his journey. Inf. II, 53–74.

- Asked by Lucia to help Dante. Inf. II, 103–14.

- When Dante appears upset by Farinata's prophecy on his future exile, Virgil intervenes and explains to him that Beatrice, "quella il cui bell' occhio tutto vede" ("one whose gracious eyes see everything"), will eventually clarify all. Inf. X, 130–2.

- Virgil, speaking with Chiron, alludes to Beatrice as she who has entrusted Dante to him. Inf. XII, 88.

- Speaking with Brunetto Latini Dante alludes to her as the woman who shall fully explain the sense of Brunetto's prophecy regarding his exile from Florence. Inf. XV, 90.

- Saint Bede: English monkMonasticismMonasticism is a religious way of life characterized by the practice of renouncing worldly pursuits to fully devote one's self to spiritual work...

, and scholar, whose best-known work, Historia ecclesiastica gentis AnglorumHistoria ecclesiastica gentis AnglorumThe Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum is a work in Latin by Bede on the history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between Roman and Celtic Christianity.It is considered to be one of the most important original references on...

(The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) gained him the title "The father of English historyHistory of EnglandThe history of England concerns the study of the human past in one of Europe's oldest and most influential national territories. What is now England, a country within the United Kingdom, was inhabited by Neanderthals 230,000 years ago. Continuous human habitation dates to around 12,000 years ago,...

".- Encountered in the Fourth Sphere of Heaven (The sun). Par. X, 130–1.

- Mastro Benvenuto: Nicknamed Asdente ("toothless"), he was a late 13th century ParmaParmaParma is a city in the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna famous for its ham, its cheese, its architecture and the fine countryside around it. This is the home of the University of Parma, one of the oldest universities in the world....

shoemaker, famous for his prophecies against Frederick II. Dante also mentions him with contempt in his ConvivioConvivioConvivio is a work written by Dante Alighieri roughly between 1304 and 1307. It contains details of the author's growing interest in philosophy, particularly in reference to the works of Cicero and Boethius...

, as does SalimbeneSalimbene di AdamSalimbene di Adam was an Italian Franciscan friar and chronicler who is a source for Italian history of the 13th century.-Life:...

in his Cronica, though with a very different tone.- Among the soothsayers. Inf. XX, 118–120.

- Gualdrada Berti: Daughter of Bellincione Berti dei Ravignani, from about 1180 wife to Guido the Elder of the great Guidi family, and grandmother of Guido Guerra. The 14th century Florentine chronicler Giovanni VillaniGiovanni VillaniGiovanni Villani was an Italian banker, official, diplomat and chronicler from Florence who wrote the Nuova Cronica on the history of Florence. He was a leading statesman of Florence but later gained an unsavory reputation and served time in prison as a result of the bankruptcy of a trading and...

remembers her as a model of ancient Florentine virtue.- "The good Gualdrada". Inf. XVI, 37.

- Bertran de BornBertran de BornBertran de Born was a baron from the Limousin in France, and one of the major Occitan troubadours of the twelfth century.-Life and works:...

(c. 1140–c. 1215): French soldier and troubadourTroubadourA troubadour was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages . Since the word "troubadour" is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a trobairitz....

poet, and viscountViscountA viscount or viscountess is a member of the European nobility whose comital title ranks usually, as in the British peerage, above a baron, below an earl or a count .-Etymology:...

of HautefortHautefortHautefort is a commune in the Dordogne department in Aquitaine in southwestern France.It was formerly part of the former province of Périgord.-History:...

, he fomented trouble between Henry II of EnglandHenry II of EnglandHenry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

and his sons.- Among the sowers of discord, where he carries his severed head (although he died a natural death). Inf. XXVIII, 118–142.

- "The lord of Hautefort." Inf. XXIX, 29.

- Guido BonattiGuido BonattiGuido Bonatti was an Italian astronomer and astrologer from Forlì. He was the most celebrated astrologer in Europe in his century.-Biography:...

: A prominent 13th century astrologer, and a staunch Ghibelline, he is famous for having boasted of being responsible for the SeneseSienaSiena is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.The historic centre of Siena has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It is one of the nation's most visited tourist attractions, with over 163,000 international arrivals in 2008...

victory at MontapertiBattle of MontapertiThe Battle of Montaperti was fought on September 4, 1260, between Florence and Siena in Tuscany as part of the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines...

in 1260.- Among the soothsayers. Inf. XX, 118.

- BonaventureBonaventureSaint Bonaventure, O.F.M., , born John of Fidanza , was an Italian medieval scholastic theologian and philosopher. The seventh Minister General of the Order of Friars Minor, he was also a Cardinal Bishop of Albano. He was canonized on 14 April 1482 by Pope Sixtus IV and declared a Doctor of the...

: FranciscanFranciscanMost Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

theologianTheologyTheology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

.- He eulogised St. Dominic. Par. XII, 31–105.

- Pope Boniface VIIIPope Boniface VIIIPope Boniface VIII , born Benedetto Gaetani, was Pope of the Catholic Church from 1294 to 1303. Today, Boniface VIII is probably best remembered for his feuds with Dante, who placed him in the Eighth circle of Hell in his Divina Commedia, among the Simonists.- Biography :Gaetani was born in 1235 in...

(c. 1235–1303): Elected in 1294 upon the abdicationPapal abdicationPapal resignation is envisaged as a possibility in canon 332 §2 of the Code of Canon Law and canon 44 §2 of the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches...

of Celestine V, whom he promptly imprisoned. He supported the Black Guelphs against Dante's party the White Guelphs (see Guelphs and Ghibellines). He was in conflict with the powerful Colonna familyColonna familyThe Colonna family is an Italian noble family; it was powerful in medieval and Renaissance Rome, supplying one Pope and many other Church and political leaders...

, who contested the legitimacy of Celestine's abdication, and thus Boniface's papacy. Wishing to capture the impregnable Colonna stronghold of PalestrinaPalestrinaPalestrina is an ancient city and comune with a population of about 18,000, in Lazio, c. 35 km east of Rome...

, he sought advice from Guido da Montefeltro, offering in advance papal absolution for any sin his advice might entail. He advised Boniface to promise the Colonnas amnesty, then break it. As a result the Collonas surrendered the fortress and it was razed to the ground.- "One who tacks his sails". Inf. VI, 68.

- Referred to ironically using one of the official papal titles "servo de' servi" (Servant of His servants"). Inf. XV, 112

- Accused of avarice, deceit and violating the "lovely Lady" (the church). Inf. XIX, 52–7.

- Pope Nicholas III prophesies his eternal damnation among the Simoniacs. Inf. XIX, 76–7.

- The "highest priest — may he be damned!". Inf. XXVII, 70.

- The "prince of the new Pharisees". Inf. XXVII, 85.

- His feud with the Colonna familyColonna familyThe Colonna family is an Italian noble family; it was powerful in medieval and Renaissance Rome, supplying one Pope and many other Church and political leaders...

and the advice of Guido da Montefeltro. Inf. XXVII, 85–111.

- Guglielmo Borsiere, a pursemaker accused of sodomySodomySodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

(see Sodom), who made a joke that was the subject of the Decameron (i, 8).- A sodomiteSodomySodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

mentioned in the seventh circle, round 3 by Jacopo Rusticucci as having spoken to him and his companions of the moral decline of Florence, generating great anguish and inducing Rusticucci to ask Dante for corroboration. Inf. XVI 67–72.

- A sodomite

- Martin Bottario: A cooper of Lucca who held various positions in the government of his city. He died in 1300, the year of Dante's travel.

- Probably the "elder of Saint Zita" who is plunged into a lake of boiling pitch with the other barrators by a Malebranche. Inf. XXI, 35–54.

- Agnello Brunelleschi: From the noble Florentine Brunelleschi family, he sided first with the White Guelphs, then the Blacks. A famous thief, he was said to steal in disguise.

- Among the thieves, he merges with Cianfa Donati to form a bigger serpent. Inf. XXV, 68.

- Brutus, Lucius JuniusLucius Junius BrutusLucius Junius Brutus was the founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of the first consuls in 509 BC. He was claimed as an ancestor of the Roman gens Junia, including Marcus Junius Brutus, the most famous of Caesar's assassins.- Background :...

: Traditionally viewed as the founder of the Roman RepublicRoman RepublicThe Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

, because of his role in overthrowing Tarquin, the last Roman king.- Seen in Limbo. Inf. IV, 127.

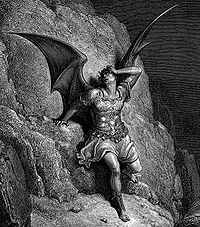

- Brutus, Marcus JuniusMarcus Junius BrutusMarcus Junius Brutus , often referred to as Brutus, was a politician of the late Roman Republic. After being adopted by his uncle he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, but eventually returned to using his original name...

(d. 43 BCE): One of the assassins of Julius Caesar, with whom he had close ties. His betrayal of Caesar was famous ("Et tu Brute") and along with Cassius and Judas, was one of the three betrayer/suicides who, for those sins, were eternally chewed by one of the three mouths of Satan. Inf. XXXIV, 53–67. - Bulicame: Spring near ViterboViterboSee also Viterbo, Texas and Viterbo UniversityViterbo is an ancient city and comune in the Lazio region of central Italy, the capital of the province of Viterbo. It is approximately 80 driving / 80 walking kilometers north of GRA on the Via Cassia, and it is surrounded by the Monti Cimini and...

renowned for its reddish colour and sulphurous water. Part of its water was reserved for the use of prostitutes. Inf. XIV, 79–83.

C

- Caccia d'Asciano: See Spendthrift Club.

- Venedico and Ghisolabella Caccianemico: Venedico (c. 1228–c. 1302) was head of the Guelph faction in BolognaBolognaBologna is the capital city of Emilia-Romagna, in the Po Valley of Northern Italy. The city lies between the Po River and the Apennine Mountains, more specifically, between the Reno River and the Savena River. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with spectacular history,...

, he was exiled three times for his relationship with the marquess of FerraraFerraraFerrara is a city and comune in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital city of the Province of Ferrara. It is situated 50 km north-northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream of the Po River, located 5 km north...

, Obizzo II d'Este.- Found among the panders, he confesses that he prostituted his sister Ghisolabella to Obizzo. Inf. XVIII, 40–66.

- CacusCacusIn Roman mythology, Cacus was a fire-breathing giant monster and the son of Vulcan.-Mythology:Cacus lived in a cave in the Palatine Hill in Italy, the future site of Rome. To the horror of nearby inhabitants, Cacus lived on human flesh and would nail the heads of victims to the doors of his cave...

: A mythologicalGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

monster son of HephaestusHephaestusHephaestus was a Greek god whose Roman equivalent was Vulcan. He is the son of Zeus and Hera, the King and Queen of the Gods - or else, according to some accounts, of Hera alone. He was the god of technology, blacksmiths, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metals, metallurgy, fire and volcanoes...

, he was killed by Heracles for stealing part of the cattle the hero had taken from Geryon. Dante, like other medieval writers, erroneously believes him to be a Centaur. According to Virgil he lived on the Aventine.- As guardian of the thieves he punishes Vanni Fucci. Inf. XXV, 17–33.

- CadmusCadmusCadmus or Kadmos , in Greek mythology was a Phoenician prince, the son of king Agenor and queen Telephassa of Tyre and the brother of Phoenix, Cilix and Europa. He was originally sent by his royal parents to seek out and escort his sister Europa back to Tyre after she was abducted from the shores...

: MythicalGreek mythologyGreek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

son of the PhoeniciaPhoeniciaPhoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

n king AgenorAgenorAgenor was in Greek mythology and history a Phoenician king of Tyre. Herodotus estimates that Agenor lived sometime before the year 2000 B.C..-Genealogy:...

and brother of EuropaEuropa (mythology)In Greek mythology Europa was a Phoenician woman of high lineage, from whom the name of the continent Europe has ultimately been taken. The name Europa occurs in Hesiod's long list of daughters of primordial Oceanus and Tethys...

, and legendary founder of ThebesThebes, GreeceThebes is a city in Greece, situated to the north of the Cithaeron range, which divides Boeotia from Attica, and on the southern edge of the Boeotian plain. It played an important role in Greek myth, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus and others...

. Cadmus and his wife Harmonia are ultimately transformed into serpents. (See also Hera.)- His transformation in

Cahors

Cahors is the capital of the Lot department in south-western France.Its site is dramatic being contained on three sides within an udder shaped twist in the river Lot known as a 'presqu'île' or peninsula...

: Town in France that was notorious for the high level of usury that took place there and became a synonym

Synonym

Synonyms are different words with almost identical or similar meanings. Words that are synonyms are said to be synonymous, and the state of being a synonym is called synonymy. The word comes from Ancient Greek syn and onoma . The words car and automobile are synonyms...

for that sin.

- Mentioned as being punished in the last circle.

- An allusion to a popular tradition that identified the MoonMoonThe Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

's spots with him.

Caiaphas

Joseph, son of Caiaphas, Hebrew יוסף בַּר קַיָּפָא or Yosef Bar Kayafa, commonly known simply as Caiaphas in the New Testament, was the Roman-appointed Jewish high priest who is said to have organized the plot to kill Jesus...

: The Jewish High Priest during the governorship of Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilatus , known in the English-speaking world as Pontius Pilate , was the fifth Prefect of the Roman province of Judaea, from AD 26–36. He is best known as the judge at Jesus' trial and the man who authorized the crucifixion of Jesus...

of the Roman province of Judea

Iudaea Province

Judaea or Iudaea are terms used by historians to refer to the Roman province that extended over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Israel...

, who according to the Gospel

Gospel

A gospel is an account, often written, that describes the life of Jesus of Nazareth. In a more general sense the term "gospel" may refer to the good news message of the New Testament. It is primarily used in reference to the four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John...

s had an important role in the crucifixion of Jesus.

- Among the hypocrites, his punishment is to be crucified to the ground while the full rank of the sinners tramples him.

Calchas

In Greek mythology, Calchas , son of Thestor, was an Argive seer, with a gift for interpreting the flight of birds that he received of Apollo: "as an augur, Calchas had no rival in the camp"...

: Mythical

Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

Greek seer at the time of the Trojan war

Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, the king of Sparta. The war is among the most important events in Greek mythology and was narrated in many works of Greek literature, including the Iliad...

, who as augur at Aulis, determined the most propitious time for the Greek fleet to depart for Troy.

- With

Camilla (mythology)

In Roman mythology, Camilla of the Volsci was the daughter of King Metabus and Casmilla. Driven from his throne, Metabus was chased into the wilderness by armed Volsci, his infant daughter in his hands. The river Amasenus blocked his path, and, fearing for the child's welfare, Metabus bound her to...

: Figure from Roman mythology

Roman mythology

Roman mythology is the body of traditional stories pertaining to ancient Rome's legendary origins and religious system, as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans...

and Virgil's Aeneid

Aeneid

The Aeneid is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. It is composed of roughly 10,000 lines in dactylic hexameter...

(VII, 803; XI), was the warrior-daughter of King Metabus

Metabus

In Roman mythology, King Metabus of the Volsci was the father of Camilla.Driven from his throne, Metabus and his infant daughter Camilla were chased into the wilderness by armed Volsci. When the river Amasenus blocked his path, he bound her to a spear and promised Diana that Camilla would be her...

of the Volsci

Volsci

The Volsci were an ancient Italic people, well known in the history of the first century of the Roman Republic. They then inhabited the partly hilly, partly marshy district of the south of Latium, bounded by the Aurunci and Samnites on the south, the Hernici on the east, and stretching roughly from...

, and ally of Turnus, king of the Rutuli

Rutuli

The Rutuli or Rutulians were members of a legendary Italic tribe...

, against Aeneas and the Trojans, and was killed in that war.

- One of those who "died for Italy".

Cangrande I della Scala

Cangrande della Scala was an Italian nobleman, the most celebrated of the della Scala family which ruled Verona from 1277 until 1387. Now perhaps best known as the leading patron of the poet Dante Alighieri, Cangrande was in his own day chiefly acclaimed as a successful warrior and autocrat...

(1290–1329): Ghibelline ruler of Verona

Verona

Verona ; German Bern, Dietrichsbern or Welschbern) is a city in the Veneto, northern Italy, with approx. 265,000 inhabitants and one of the seven chef-lieus of the region. It is the second largest city municipality in the region and the third of North-Eastern Italy. The metropolitan area of Verona...

and most probable figure behind the image of the "hound" ("il Veltro"). Inf. I, 101–111.

Capaneus

In Greek mythology, Capaneus was a son of Hipponous and either Astynome or Laodice , and husband of Evadne, with whom he fathered Sthenelus. Some call his wife Ianeira....

: In Greek mythology

Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

, in the story of the Seven Against Thebes

Seven Against Thebes

The Seven against Thebes is the third play in an Oedipus-themed trilogy produced by Aeschylus in 467 BC. The trilogy is sometimes referred to as the Oedipodea. It concerns the battle between an Argive army led by Polynices and the army of Thebes led by Eteocles and his supporters. The trilogy won...

he defied Zeus who then killed him with a thunderbolt in punishment.

- Found amongst the violent against God.

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

in 1293.

- Among the "falsifiers" of metal (alchemistsAlchemyAlchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

), sitting with Griffolino of Arezzo, propping each other up, as they frantically scratch at the scabs covering their bodies. Inf. XXIX, 73–99. - Agrees with Dante about the vanity of the SieneseSienaSiena is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.The historic centre of Siena has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It is one of the nation's most visited tourist attractions, with over 163,000 international arrivals in 2008...

, giving as examples four of the members of the Sienese Spendthrift Club, then identifies himself. Inf. XXIX, 124–139. - He is dragged, with his belly scraped along the ground, by the tusks of Schicchi. Inf. XXX, 28–30.

Caprona

Caprona is a genus of skipper butterflies . They belong to the tribe Tagiadini of subfamily Pyrginae.-Species:*Caprona adelica Karsch, 1892*Caprona agama *Caprona alida...

: Fortress on the Arno

Arno

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.- Source and route :The river originates on Mount Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a southward curve...

near Pisa

Pisa

Pisa is a city in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the right bank of the mouth of the River Arno on the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa...

, in 1289, it was besieged by a Tuscan

Tuscany

Tuscany is a region in Italy. It has an area of about 23,000 square kilometres and a population of about 3.75 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence ....

Guelph army. The Ghibellines surrendered, and were allowed, under truce, to leave the castle, passing through (with trepidation) the enemy ranks. Caprona's fall along with the Guelph victory in the same year at Campaldino

Battle of Campaldino

The Battle of Campaldino was a battle between the Guelphs and Ghibellines on 11 June 1289. Mixed bands of pro-papal Guelf forces of Florence and allies, Pistoia, Lucca, Siena and Prato, all loosely commanded by the paid condottiero Amerigo di Narbona with his own professional following, met a...

represented the final defeat of the Ghibellines. Dante's reference to Caprona in the Inferno, is used to infer that he took part in the siege.