History of anti-Semitism

Encyclopedia

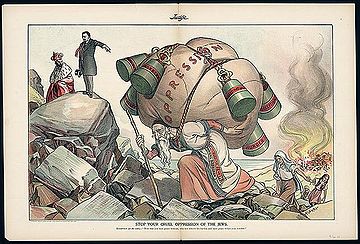

The history of antisemitism – defined as hostile actions or discrimination against Jews as a religious or ethnic group – goes back many centuries; antisemitism has been called "the longest hatred." Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

In practice, it is difficult to differentiate antisemitism from the general ill-treatment of nations by other nations before the Roman

period, but since the adoption of Christianity

in Europe, antisemitism has undoubtedly been present. The Islamic world has also seen the Jews historically as outsiders. The coming of the scientific and industrial revolution in 19th century Europe bred a new manifestation of antisemitism, based as much upon race as upon religion, culminating in the horrors of the Nazi extermination camps of World War II. The formation of the state of Israel

in 1948 has created new antisemitic tensions in the Middle East.

Indeed, he asserts that "one of the great puzzles that has confronted the students of anti-semitism is the alleged shift from pro-Jewish statements found in the first pagan writers who mention the Jews... to the vicious anti-Jewish statements thereafter, beginning with Manetho

about 270B.C.E. In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek

retelling of Ancient Egypt

ian prejudices". As examples of pagan writers who spoke positively of Jews, Feldman cites Aristotle

, Theophrastus

, Clearchus of Soli

and Megasthenes

. Feldman concedes that, after Manetho, "the picture usually painted is one of universal and virulent anti-Judaism."

The first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment can be traced back to Alexandria

in the 3rd century BCE. Alexandria was home to the largest Jewish community in the world and the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible

, was produced there. Manetho

, an Egyptian priest and historian of that time, wrote scathingly of the Jews and his themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon

, Lysimachus

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

, and in Apion

and Tacitus

. One of the earliest anti-Jewish edict

s, promulgated by Antiochus Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees

in Judea

.

The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died. The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews being portrayed as misanthropes

. Tcherikover argues that the reason for hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the poleis

. Bohak has argued, however, that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, and that many Greeks showed animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.

Statements exhibiting prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan Greek

and Roman

writers. Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho

, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers

who had been taught by Moses

"not to adore the gods." The same themes appeared in the works of Chaeremon

, Lysimachus

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

, and in Apion

and Tacitus

. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practices" of the Jews and of the "absurdity of their Law," and how Ptolemy Lagus

was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BC because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath

. Edward Flannery describes antisemitism in ancient times as essentially " cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia played out in political settings."

There is a recorded instance of an Ancient Greek

ruler, Antiochus Epiphanes, desecrating the Temple in Jerusalem

and banning Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision

, Shabbat

observance and the study of Jewish religious books, during the period when Ancient Greece dominated the eastern Mediterranean. Statements exhibiting prejudice towards Jews and their religion can also be found in the works of a few pagan Greek and Roman writers, but the earliest occurrence of antisemitism has been the subject of debate among scholars, largely because different writers use different definitions of antisemitism. The terms "religious antisemitism" and "anti-Judaism

" are sometimes used to refer to animosity towards Judaism as a religion rather than to Jews defined as an ethnic or racial group.

were antagonistic from the very start and resulted in several rebellions

.

Several ancient historians report that in 19 CE the Roman emperor Tiberius

expelled Jews from Rome. According to the Roman historian Suetonius

, Tiberius tried to suppress all foreign religions. In the case of Jews, he sent young Jewish men, under the pretence of military service, to provinces noted for their unhealthy climate. He dismissed all other Jews from the city, under threat of life slavery for non-compliance. Josephus

, in his Jewish Antiquities, confirms that Tiberius ordered all Jews to be banished from Rome. Four thousand were sent to Sardinia

but more, who were unwilling to become soldiers, were punished. Cassius Dio reports that Tiberius banished most of the Jews, who had been attempting to convert Romans to their religion. Philo of Alexandria reported that Sejanus

, one of Tiberius's lieutenants, may have been a prime mover in the persecution of the Jews.

The Romans refused to permit Jews to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem after its destruction by Titus

in 70 CE, imposed a tax on Jews (Fiscus Judaicus

) at the same time, ostensibly to finance the Temple of Jupiter in Rome, and renamed Judaea

as Syria Palestina. The Jerusalem Talmud

relates that, following Bar Kokhba's revolt

(132–6 CE), the Romans destroyed very many Jews, "killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils." However, some historians argue that Rome suppressed revolts in all its conquered territories and point out that Tiberius expelled all foreign religions from Rome, not just the Jews.

Some accommodation, in fact, was later made with Judaism, and the Jews of the Diaspora

had privileges that others did not. Unlike other subjects of the Roman Empire, they had the right to maintain their religion and were not expected to accommodate themselves to local customs. Even after the First Jewish–Roman War, the Roman authorities refused to rescind Jewish privileges in some cities. And although Hadrian

outlawed circumcision as a mutilation normally visited on people unable to consent, he later exempted the Jews. According to the 18th century historian Edward Gibbon

, there was greater tolerance from about 160 CE. Between 355 and 363 CE, permission was granted by Julian the Apostate

to rebuild the Second Temple of Jerusalem.

It has been argued that European antisemitism has its roots in Roman policy.

was written, ostensibly, by Jews who became followers of Jesus

, there are a number of passages in the New Testament that some see as antisemitic, or that have been used for antisemitic purposes, including:

Some biblical scholars point out that Jesus and Stephen are presented as Jews speaking to other Jews, and that their use of broad accusations against Israel is borrowed from Moses

and the later Jewish prophets. Other scholars hold that verses like these reflect Jewish-Christian tensions that were emerging in the late 1st or early 2nd century. Today, nearly all Christian denominations place little emphasis on verses such as these, and reject their misuse.

After Jesus' death, the New Testament portrays the Jewish religious authorities in Jerusalem as hostile to Jesus' followers, and as occasionally using force against them. Stephen is executed by stoning. Before his conversion, Saul puts followers of Jesus in prison. After his conversion, Saul

is whipped at various times by Jewish authorities. He is accused by Jewish authorities before the Roman courts. However, opposition by gentiles is also described, and more generally, there are widespread references in the New Testament to the suffering experienced by Jesus' followers at the hands of others, particularly the Romans.

. The Council of Antioch (341) prohibited Christians from celebrating Passover with the Jews whilst the Council of Laodicea

forbade Christians from keeping the Jewish Sabbath.

The Roman emperor Constantine I

instituted several laws concerning the Jews: they were forbidden to own Christian slaves or to circumcise their slaves. The conversion of Christians to Judaism was outlawed. Religious services were regulated, congregations restricted, but Jews were allowed to enter Jerusalem on Tisha B'Av

, the anniversary of the destruction of the Temple.

Discrimination became worse in the 5th century. The edicts of the Codex Theodosianus

(438) barred Jews from the civil service, the army and the legal profession. The Jewish Patriarchate was abolished and the scope of Jewish courts restricted. Synagogues were confiscated and old synagogues could be repaired only if they were in danger of collapse. Synagogues fell into ruin or were converted to churches. Synagogues were destroyed in Tortona

(350), Rome (388 and 500), Raqqa (388), Minorca

(418), Daphne (near Antioch

, 489 and 507), Genoa

(500), Ravenna

(495), Tours

(585) and in Orléans

(590). Other synagogues were confiscated: Urfa in 411, several in Judea between 419 and 422, Constantinople

in 442 and 569, Antioch

in 423, Vannes

in 465, Diyarbakir

in 500 Terracina

in 590, Cagliari

in 590 and Palermo

in 590.

is the killing of a god. In the context of Christianity, deicide refers to the responsibility for the death of Jesus. The accusation of Jews in deicide

has been the most powerful warrant for antisemitism by Christians.

The earliest recorded instance of an accusation of deicide against the Jewish people as a whole — that they were collectively responsible for the death of Jesus — occurs in a sermon of 167 CE attributed to Melito of Sardis

entitled Peri Pascha, On the Passover. This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and Caiaphas to execute Jesus. Melito does not attribute particular blame to Pontius Pilate

, mentioning only that Pilate washed his hands of guilt. The sermon is written in Greek, but may have been an appeal to Rome to spare Christians at a time when Christians were widely persecuted.

The Latin word deicidas, from which the word deicide is derived, was used in the 4th century by Peter Chrystologus in his sermon number 172. Though not part of Roman Catholic dogma

, many Christians, including members of the clergy

, once held Jews to be collectively responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time had committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing.

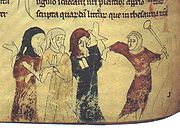

s, expulsions, forced conversion

s and killings. In the 12th century, there were Christians who believed that some, or possibly all, of the Jews possessed magical powers and had gained these powers from making a pact with the devil

. Judensau

images began to appear in Germany.

The persecution of the Jews in Europe reached a climax during the Crusades

. At the time of the First Crusade

, in 1096, a German Crusade

destroyed flourishing Jewish communities on the Rhine and the Danube. In the Second Crusade

in 1147, the Jews in France were the victims of frequent killings and atrocities. The Jews were also subjected to attacks during the Shepherds' Crusade

s of 1251 and 1320. Following these crusades, Jews were subject to expulsions, including, in 1290, the banishing of all English Jews. In 1396, 100,000 Jews were expelled from France and in 1421, thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of those expelled fled to Poland.

As the Black Death

plague swept across Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than half of the population, Jews often became the scapegoats. Rumors spread that they had caused this epidemic by deliberately poisoning wells

. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by the ensuing hatred and violence. Pope Clement VI

tried to protect Jews by a papal bull

dated July 6, 1348, and by an additional bull soon afterwards, but several months later, 900 Jews were burnt alive in Strasbourg

, where the plague had not yet affected the city.

imposed dhimmi

status on both Christian and Jewish minorities, although Jews were allowed more freedom to practise their religion in the Muslim world

than they were in Christian Europe.

In Muslim Spain

, the Jews prospered under the tolerant rule of the Ummayad caliphate, and Cordova

became a centre of Jewish culture. However, the advent of the Almoravides from North Africa in the 11th century saw harsh measures taken against both Christians and Jews. As part of this repression there were pogroms against Jews in Cordova in 1011 and in Granada in 1066

.

The Almohad

s, who by 1147 had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi and Andalusian territories, took a less tolerant view still and treated the dhimmis harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians took a third option if they could, and fled. Some, such as the family of Maimonides

, went east to more tolerant Muslim lands, while others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms. At certain times in the Middle Ages, in Egypt

, Syria

, Iraq

and Yemen

, decrees ordering the destruction of synagogues were enacted. Jews were forced to convert to Islam or face death in parts of Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad

.

, and it was an occupation forbidden to Christians. Not being subject to this restriction, Jews made this business their own, despite possible criticism of usury in the Torah

and later sections of the Hebrew Bible

. Unfortunately, this led to many negative stereotypes of Jews as insolent, greedy usurers

and the understandable tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could see them as personally taking their money while unaware of those on whose behalf these Jews worked.

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal disabilities

and restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Even moneylending and peddling were at times forbidden to them. The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own and were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths

, and they suffered a variety of other measures. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 decreed that Jews

and Muslims must wear distinguishing clothing. The most common such clothing was the Jewish hat, which was already worn by many Jews as a self-identifying mark, but was now often made compulsory.

The Jewish badge was introduced in some places; it could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a circle, strip, or the tablets of the law (in England), and was sewn onto the clothes. Elsewhere special colours of robe were specified. Implementation was in the hands of local rulers but by the following century laws had been enacted covering most of Europe. In many localities, members of Medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as those worn by guild

The Jewish badge was introduced in some places; it could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a circle, strip, or the tablets of the law (in England), and was sewn onto the clothes. Elsewhere special colours of robe were specified. Implementation was in the hands of local rulers but by the following century laws had been enacted covering most of Europe. In many localities, members of Medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as those worn by guild

members) were prestigious, while others were worn by ostracised outcasts such as leper

s, reformed heretics

and prostitutes

. As with all sumptuary law

s, the degree to which these laws were followed and enforced varied greatly. Sometimes, Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid for whenever the king needed to raise funds. By the end of the Middle Ages

, the hat seems to have become rare, but the badge lasted longer and remained in some places until the 18th century.

The People's Crusade

that accompanied the first Crusade

attacked Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and killed many Jews. Entire communities, like those of Treves

, Speyer

, Worms

, Mainz

, and Cologne

, were murdered by armed mobs. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhineland

cities alone between May and July 1096. Before the Crusades, Jews had practically a monopoly on the trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of Christian merchant traders, and from this time onwards, restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against Jews as against Muslims, although attempts were made by bishops during the first Crusade and by the papacy during the second Crusade

to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially, the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III

.

The Jewish defenders of Jerusalem retreated to their synagogue to "prepare for death" once the Crusaders had breached the outer walls of the city during the siege of 1099

. The chronicle of Ibn al-Qalanisi

states that the building was set on fire whilst the Jews were still inside. The Crusaders were supposedly reported as hoisting up their shields and singing "Christ We Adore Thee!" while they encircled the burning building." Following the siege, Jews captured from the Dome of the Rock

, along with native Christians, were made to clean the city of the slain. Numerous Jews and their holy books (including the Aleppo Codex

) were held ransom by Raymond of Toulouse. The Karaite Jewish community of Ashkelon

(Ascalon) reached out to their coreligionists in Alexandria

to first pay for the holy books and then rescued pockets of Jews over several months. All that could be ransomed were liberated by the summer of 1100. The few who could not be rescued were either converted to Christianity or murdered.

In the County of Toulouse, in southern France, toleration and favour shown to Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse at the beginning of the 13th century. Organised and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade

, because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI of Toulouse was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII, underwent a similar ceremony.

. According to the authors of these so-called blood libel

s, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic

would be performed on it. This method, with some variations, can be found in all the alleged Christian descriptions of ritual murder by Jews.

The story of William of Norwich

The story of William of Norwich

(d. 1144) is often cited as the first known accusation of ritual murder against Jews. The Jews of Norwich

, England were accused of murder after a Christian boy, William, was found dead. It was claimed that the Jews had tortured and crucified him. The legend of William of Norwich became a cult, and the child acquired the status of a holy martyr. Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln

(d. 1255), in the 13th century, reputedly had his belly cut open and his entrails

removed for some occult

purpose, such as a divination ritual

, after being taken from a cross. Simon of Trent

(d. 1475), in the fifteenth, was held over a large bowl so that all his blood could be collected, it was alleged.

During the Middle Ages, such blood libels were directed against Jews in many parts of Europe. The believers of these accusations reasoned that the Jews, having crucified Jesus, continued to thirst for pure and innocent blood, at the expense of innocent Christian children.

Jews were sometimes falsely accused of desecrating consecrated hosts in a reenactment of the Crucifixion

; this crime was known as host desecration

and carried the death penalty.

for their return was utilized to enrich the French crown during the 13th and 14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the whole of France by Louis IX

in 1254, by Charles IV

in 1306, by Charles V

in 1322 and by Charles VI

in 1394.

To finance his war against Wales

in 1276, Edward I of England

taxed Jewish moneylenders. When the moneylenders could no longer pay the tax, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, Edward abolished their "privilege" to lend money, restricted their movements and activities and forced Jews to wear a yellow patch

. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested with over 300 being taken to the Tower of London

and executed. Others were killed in their homes. All Jews were banished from the country in 1290, where it was possible that hundreds were killed or drowned while trying to leave the country. All the money and property of these dispossessed Jews was confiscated. No Jews were known to be in England thereafter until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell

reversed the policy.

, 40 Jews were burnt in Toulon

as quickly after the outbreak as April 1348. "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague; they were tortured until they "confessed" to crimes that they could not possibly have committed. In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry

(near Geneva

) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice

, Toulouse

, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet's "confession", the Jews of Strasbourg

were burned alive on February 14, 1349."

and Isabella I of Castile

to institute the Spanish Inquisition

. The Inquisition used torture

to elicit confessions and delivered judgment at public ceremonials known as autos da fe before they gave their victims over to the secular authorities for punishment. Under this dispensation, some 30,000 were condemned to death and executed by being burnt alive.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile issued an edict of expulsion

of Jews from Spain, giving Jews four months to either convert to Christianity or leave the country. Some 165,000 emigrated and some 50,000 converted to Christianity.

Portugal followed suit in December 1496. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the King. When those who chose to leave the country arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion and promises to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country. This episode technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as New Christians or marranos. They were given a grace period of thirty years during which no inquiry into their faith would be allowed. This period was later extended until 1534. However, a popular riot in 1504 resulted in the deaths of up to five thousand Jews, and the execution of the leaders of the riot by King Manuel

. Those labeled as New Christians were under the surveillance of the Portuguese Inquisition

from 1536 until 1821.

Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal, known as Sephardi Jews

from the Hebrew word for Spain, fled to North Africa, Turkey and Palestine within the Ottoman Empire

, and to Holland, France and Italy. Within the Ottoman Empire, Jews could openly practise their religion. Amsterdam

in Holland also became a focus for settlement by the persecuted Jews from many lands in succeeding centuries.

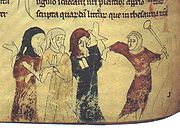

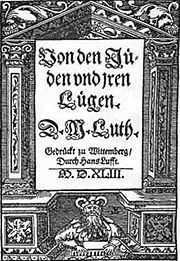

Martin Luther

, an Augustinian friar and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Reformation

, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his pamphlet On the Jews and their Lies, written in 1543. He portrays the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom

against them, calling for their permanent oppression and expulsion. At one point he writes: "...we are at fault in not slaying them..." a passage that "may be termed the first work of modern antisemitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust

."

Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism. Muslow and Popkin assert that, "the antisemitism of the early modern period was even worse than that of the Middle Ages; and nowhere was this more obvious than in those areas which roughly encompass modern-day Germany, especially among Lutherans."

In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached: "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."

was a boy from the city of Trento, Italy, who was found dead at the age of two in 1475, having allegedly been kidnapped, mutilated, and drained of blood. His disappearance was blamed on the leaders of the city's Jewish community, based on confessions extracted under torture, in a case that fueled the rampant antisemitism of the time. Simon was regarded as a saint, and was canonized by Pope Sixtus V

in 1588.

, the last Dutch Director-General of the colony of New Amsterdam

, later New York City, sought to bolster the position of the Dutch Reformed Church

by trying to stem the religious influence of Jews, Lutherans, Catholics and Quakers. He stated that Jews were "deceitful", "very repugnant", and "hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ". However, religious plurality was already a cultural tradition and a legal obligation in New Amsterdam and in the Netherlands, and his superiors at the Dutch West India Company

in Amsterdam

overruled him.

During the mid-to-late-17th century the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

was devastated by several conflicts, in which the Commonwealth lost over a third of its population (over 3 million people). The decrease of the Jewish population during that period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, including emigration, deaths from diseases and captivity in the Ottoman Empire

. These conflicts began in 1648 when Bohdan Khmelnytsky

instigated the Khmelnytsky Uprising

against the Polish aristocracy and the Jews who administered their estates. Khmelnytsky's Cossack

s massacred tens of thousands of Jews in the eastern and southern areas that he controlled (now the Ukraine

). This persecution led many Jews to pin their hopes on a man called Shabbatai Zevi who emerged in the Ottoman Empire at this time and proclaimed himself Messiah

in 1665. However his later conversion to Islam dashed these hopes and led many Jews to discredit the traditional belief in the coming of the Messiah as the hope of salvation.

" saw the dismantling of archaic corporate, hierarchical forms of society in favour of individual equality of citizens before the law. How this new state of affairs would affect previously autonomous, though subordinated, Jewish communities became known as the Jewish question

. In many countries, enhanced civil rights were gradually extended to the Jews, though often only in a partial form and on condition that the Jews abandon many aspects of their previous identity in favour of integration and assimilation with the dominant society.

In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia

limited the number of Jews allowed to live in Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged a similar practice in other Prussia

n cities. In 1750 he issued the Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: forcing these "protected" Jews to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin." In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa

ordered Jews out of Bohemia

but soon reversed her position, on condition that they pay for their readmission every ten years. This extortion

was known as malke-geld (queen's money). In 1752 she introduced a law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II

abolished most of these practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish

and Hebrew

were eliminated from public records and that judicial autonomy was annulled.

In accordance with the anti-Jewish precepts of the Russian Orthodox Church

, Russia's discriminatory policies towards Jews intensified when the partition of Poland in the 18th century resulted, for the first time in Russian history, in the possession of land with a large population of Jews. This land was designated as the Pale of Settlement

from which Jews were forbidden to migrate into the interior of Russia. In 1772, the empress of Russia Catherine II forced the Jews of the Pale of Settlement to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.

, similar laws promoting Jewish emancipation

were enacted in the early 19th century in those parts of Europe over which France had influence. The old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited their property rights, rights of worship and occupation, were rescinded.

Despite this, traditional discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism, encouraged by the work of racial theorists such as Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and particularly his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Race of 1853–5. Nationalist agendas based on ethnicity, known as ethnonationalism, usually excluded the Jews from the national community as an alien race. Allied to this were theories of Social Darwinism

, which stressed a putative conflict between higher and lower races of human beings. Such theories, usually posited by white Europeans, advocated the superiority of white Aryan

s to Semitic

Jews.

peace conference (1814–5) were unsuccessful. In 1819, German Jews were attacked in the Hep-Hep riots

. Full Jewish emancipation

was not granted in Germany until 1871, when the country was united under the Hohenzollern dynasty.

In 1850, the German composer Richard Wagner

published Das Judenthum in der Musik

("Jewishness in Music") under a pseudonym

in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik

. The essay began as an attack on Jewish composers, particularly Wagner's contemporaries (and rivals) Felix Mendelssohn

and Giacomo Meyerbeer

, but expanded to accuse Jewish influences more widely of being a harmful and alien element in German culture

.

The term "antisemitism" was coined by the German agitator and publicist, Wilhelm Marr

in 1879. In that year, Marr founded the Antisemites League and published a book called Victory of Jewry over Germandom. The late 1870s saw the growth of antisemitic political parties in Germany. These included the Christian Social Party

, founded in 1878 by Adolf Stoecker

, the Lutheran chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, as well as a German Social Antisemitic Party and an Antisemitic People's Party. However, they did not enjoy mass electoral support and at their peak in 1907, had only 16 deputies out of a total of 397 in the Reichstag.

(1870–1) was blamed by some on the Jews. Jews were accused of weakening the national spirit through association with republicanism, capitalism and anti-clericalism, particularly by authoritarian, right wing, clerical and royalist groups. These accusations were spread in antisemitic journals such as La Libre Parole, founded by Edouard Drumont

and La Croix

, the organ of the Catholic order of the Assumptionists

.

Financial scandals such as the collapse of the Union Generale Bank and the collapse of the French Panama Canal operation

were also blamed on the Jews. The Dreyfus affair

saw a Jewish military officer named Captain Alfred Dreyfus

falsely accused of treason in 1895 by his army superiors and sent to Devil's Island

after being convicted. Dreyfus was acquitted in 1906, but the case polarised French opinion between antisemitic authoritarian nationalists and philosemitic anti-clerical republicans, with consequences which were to resonate into the 20th century.

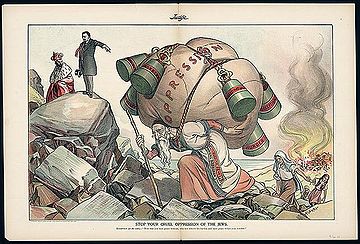

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately 3 million Ashkenazi Jews

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately 3 million Ashkenazi Jews

from Eastern Europe

immigrated to America, many of them fleeing pogroms and the difficult economic conditions which were widespread in much of Eastern Europe during this time. Pogroms in Eastern Europe, particularly Russia

, prompted waves of Jewish immigrants after 1881. Jews, along with many Eastern and Southern European immigrants, came to work the country's growing mines and factories. Many Americans distrusted these Jewish immigrants.

The earlier wave of Jewish immigration from Germany, the latter (post 1880) came from "the Pale" - the region of Eastern Poland, Russia and the Ukraine where Jews had suffered so under the Czars. Along with Italians, Irish

and other Eastern and Southern Europeans, Jews faced discrimination in the United States in employment, education and social advancement. American groups like the Immigration Restriction League

, criticized these new arrivals along with immigrants from Asia

and southern and eastern Europe, as culturally, intellectually, morally, and biologically inferior. Despite these attacks, very few Eastern European Jews returned to Europe for whatever privations they faced here, their situation in the US was still improved.

Beginning in the early 1880s, declining farm prices also prompted elements of the Populist movement to blame the perceived evils of capitalism and industrialism on Jews because of their alleged racial/religious inclination for financial exploitation and, more specifically, because of the alleged financial manipulations of Jewish financiers such as the Rothschilds. Although Jews played only a minor role in the nation's commercial banking system, the prominence of Jewish investment bankers such as the Rothschilds

in Europe, and Jacob Schiff

, of Kuhn, Loeb & Co.

in New York City, made the claims of anti-Semites believable to some.

The Morgan Bonds scandal injected populist anti-Semitism into the 1896 presidential campaign

. It was disclosed that President Grover Cleveland

had sold bonds to a syndicate which included J. P. Morgan

and the Rothschilds house

, bonds which that syndicate was now selling for a profit, the Populists used it as an opportunity to uphold their view of history, and prove to the nation that Washington and Wall Street were in the hands of the international Jewish banking houses.

Another focus of anti-Semitic feeling was the allegation that Jews were at the center of an international conspiracy to fix the currency and thus the economy to a single gold standard.

which lasted for three years. A hardening of official attitudes under Tsar Alexander III and his ministers, resulted in the May Laws

of 1882, which severely restricted the civil rights of Jews within the Russian Empire

. The Tsar's minister Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev stated that the aim of the government with regard to the Jews was that: "One third will die out, one third will leave the country and one third will be completely dissolved [into] the surrounding population". In the event, a mix of pogroms and repressive legislation did indeed result in the mass emigration of Jews to western Europe and America. Between 1881 and the outbreak of the First World War, an estimated 2.5 million Jews left Russia – one of the largest mass migrations in recorded history.

in 1828. In 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue and destroyed the Torah scrolls

, and it was only by forced conversion that a massacre was averted. There was a massacre of Jews in Barfurush in 1867.

Concerning the life of Persian Jews

in the middle of the 19th century, a contemporary author wrote:

In 1840, in the Damascus affair

, the Jews of Damascus

were falsely accused of having ritually murdered a Christian monk and his Muslim servant and of having used their blood

to bake Passover bread

. A Jewish barber was tortured until he "confessed" to this crime; two other Jews who were arrested died under torture, while a third converted to Islam to save his life.

In 1864, around 500 Jews were killed in Marrakech

and Fez

in Morocco

. In 1869, 18 Jews were killed in Tunis

, and an Arab mob looted Jewish homes and stores, and burned synagogues, on Jerba Island

. Jews in Morocco were attacked and killed in the streets in broad daylight. In 1891, the leading Muslims in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople

to prohibit the entry of Jews arriving from Russia.

One symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. A 19th century traveler observed: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine

. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."

.

In Russia, under the Tsarist regime, antisemitism intensified in the early years of the 20th century and was given official favour when the secret police forged the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document purported to be a transcription of a plan by Jewish elders to achieve global domination. Violence against the Jews in the Kishinev pogrom

In Russia, under the Tsarist regime, antisemitism intensified in the early years of the 20th century and was given official favour when the secret police forged the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document purported to be a transcription of a plan by Jewish elders to achieve global domination. Violence against the Jews in the Kishinev pogrom

in 1903 was continued after the 1905 revolution by the activities of the Black Hundreds. The Beilis Trial

of 1913 showed that it was possible to revive the blood libel accusation in Russia.

The 1917 revolution ended official discrimination against the Jews but was followed, however, by massive anti-Jewish violence by the anti-Bolshevik White Army and the nationalist Ukrainian army under Symon Petliura in the Russian Civil War

. From 1918–21, between 100,000 and 150,000 Jews were slaughtered. White emigres from revolutionary Russia fostered the idea that the Bolshevik regime, with its many Jewish members, was a front for the Jewish World Conspiracy, outlined in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which had by now achieved wide circulation in the west.

, founded by Charles Maurras

. These groups were critical of the whole political establishment of the Third Republic

. Following the Stavisky Affair

, in which a Jewish man named Serge Alexandre Stavisky was revealed to be involved in high level political corruption, these groups encouraged serious rioting which almost toppled the government in the 6 February 1934 crisis

. The rise to prominence of the Jewish socialist Léon Blum

, who became first minister of the Popular Front Government in 1936, further polarised opinion within France. Action Française and other right-wing groups launched a vicious antisemitic press campaign against Blum which culminated in an attack in which he was dragged from his car and kicked and beaten whilst a mob screamed 'Death to the Jew!'

Antisemitism was particularly virulent in Vichy France

during WWII

. The Vichy government openly collaborated with the Nazi occupiers to identify Jews for deportation and transportation to the death camps (about 75.000 were killed). The antisemitic demands of right-wing groups were implemented under the collaborating Vichy regime of Marshall Henri Phillippe Petain, following the defeat of the French by the German army in 1940. A Statut des Juifs of that year, followed by another in 1941, purged Jews from employment in administrative, civil service and judicial posts, from most professions and even from the entertainment industry – restricting them, mostly, to menial jobs. Vichy's officials aided and abetted the Nazis in arresting and transporting over seventy-three thousand Jews to their deaths in the extermination camps in Poland.

In Germany, following World War I, Nazism

In Germany, following World War I, Nazism

arose as a political movement incorporating antisemitic ideas, expressed by Adolf Hitler

in his book Mein Kampf

. After Hitler came to power in 1933, the Nazi regime sought the systematic exclusion of Jews from national life. The Nuremberg Laws

of 1935 outlawed marriage or sexual relationships between Jews and non-Jews. Antisemitic propaganda by or on behalf of the Nazi Party began to pervade society. Especially virulent in this regard was Julius Streicher

's pornographic publication Der Stürmer

, which published the alleged sexual misdemeanors of Jews for popular consumption. Mass violence against the Jews was encouraged by the Nazi regime, and on the night of 9–10 November 1938, dubbed Kristallnacht

, the regeme sanctioned the killing of Jews, the destruction of property and the torching of synagogues.

As Nazi occupation extended eastwards in World War II, antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were brought to occupied Europe, often building on local antisemitic traditions. In occupied Poland, Jews were forced into ghettos: in Warsaw

As Nazi occupation extended eastwards in World War II, antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were brought to occupied Europe, often building on local antisemitic traditions. In occupied Poland, Jews were forced into ghettos: in Warsaw

, Kraków

, Lvov, Lublin

and Radom

. Following the invasion of Russia in 1941, a campaign of mass murder in that country was conducted against the Jews by Nazi death squads called the Einsatzgruppen

. On 20 January 1942, Reinhard Heydrich

, deputed to find a "final solution" to the "Jewish problem", chaired the Wannsee Conference

at which all the Jews resident in Europe and North Africa were earmarked for extermination. Of the eleven million who were targeted, some six million men, women and children were killed by the Nazis between 1942 and 1945. This systematic genocide

is known as the Holocaust. To implement this horrific plan, Jews were transported to purpose-built extermination camps in occupied Poland, where they were killed in gas chambers

. Extermination camps were located at Auschwitz-Birkenau

, Chełmno, Bełżec, Majdanek

, Sobibór

and Treblinka

.

In the first half of the 20th century, Jews in the United States faced discrimination in employment, in access to residential and resort areas, in the membership of clubs and organizations and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrollment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. The lynching of Leo Frank

by a mob of prominent citizens in Marietta, Georgia

, in 1915, turned the spotlight on antisemitism in the United States and led to the founding of the Anti-Defamation League

, as well as to renewed support for the Ku Klux Klan

, which had been inactive since 1870.

Antisemitism in the United States

reached its peak during the 1920s and 1930s. The pioneer automobile manufacturer Henry Ford

propagated antisemitic ideas in his newspaper The Dearborn Independent

. During the 1940s, the pioneer aviator

Charles Lindbergh

and many other prominent Americans led the America First Committee

in opposing any involvement in the war against fascism. Following a visit to Germany in 1936, Lindbergh wrote: "While I still have my reservations, I have come away with great admiration for the German people... Hitler must have far more vision and character than I thought… With all the things we criticize he is undoubtedly a great man…" Although America First avoided any appearance of antisemitism and voted to drop Henry Ford as a member for this reason, Ford continued his good friendship with Lindbergh, who visited him in the summer of 1941. One month later; Lindbergh gave a speech in Des Moines, Iowa in which he expressed the decidedly Ford-like view that: "The three most important groups which have been pressing this country towards war are the British, the Jews, and the Roosevelt Administration." In his diary Lindbergh wrote: "We must limit to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence… Whenever the Jewish percentage of the total population becomes too high, a reaction seems to invariably occur. It is too bad because a few Jews of the right type are, I believe, an asset to any country." During race riots in Detroit in 1943, Jewish businesses were targeted for looting and burning.

The German American Bund held parades in New York City in the late 1930s which featured Nazi uniforms and flags with swastika

s alongside American flags. Some 20,000 people listened to Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn at Madison Square Garden

in 1939 criticizing President Franklin Delano Roosevelt by repeatedly referring to him as "Frank D. Rosenfeld" and calling his New Deal

the "Jew Deal". By espousing a belief in the existence of a Bolshevik

-Jewish conspiracy in America, Kuhn's activities came under the scrutiny of the US House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and when the United States entered World War II most of the Bund's members were placed in internment camps, and some were deported at the end of the war.

Antisemitism in the USSR reached a peak in 1948–53 when several hundred Yiddish-writing poets, writers, painters and sculptors were killed in a campaign against the so-called rootless cosmopolitan

Antisemitism in the USSR reached a peak in 1948–53 when several hundred Yiddish-writing poets, writers, painters and sculptors were killed in a campaign against the so-called rootless cosmopolitan

.

The Kielce pogrom

and "March 1968 events" in communist Poland were further incidents of antisemitism in Europe. A common theme behind the anti-Jewish violence in Poland were blood libel

rumours.

The cult of Simon of Trent was disbanded in 1965 by Pope Paul VI

and his future veneration was forbidden, although a handful of extremists still promoted the fiction.

ing conspiracy theories began to seep into progressive circles, including stories about how a "New World Order

", also called the "Shadow Government" or "The Octopus", was manipulating world governments. Antisemitic conspiracism was "peddled aggressively" by right-wing groups. Some on the left adopted the rhetoric, which it has been argued, was made possible by their lack of knowledge of the history of fascism

and its use of "scapegoating, reductionist

and simplistic solutions, demagoguery

, and a conspiracy theory of history."

Towards the end of 1990, as the movement against the Gulf War

began to build, a number of far-right and antisemitic groups sought out alliances with left-wing anti-war coalitions, who began to speak openly about a "Jewish lobby

" that was encouraging the United States to invade the Middle East. This idea evolved into conspiracy theories about a "Zionist-occupied government

" (ZOG), which has been seen as equivalent to the early-20th century antisemitic hoax, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

. The anti-war movement as a whole rejected these overtures by the political right.

In the late 20th century, leaving aside injudicious name-calling by senator Ernest Hollings

to fellow Democrat Howard Metzenbaum

on the floor of the Senate, the Crown Heights riots of 1991 were a violent expression of tensions within a very poor urban community, pitting African American

residents against followers of Hassidic Judaism. In the context of the first US-Iraq war, on September 15, 1990 Pat Buchanan

appeared on The McLaughlin Group

and said that "there are only two groups that are beating the drums for war in the Middle East – the Israeli defense ministry and its 'amen corner' in the United States." He also said: "The Israelis want this war desperately because they want the United States to destroy the Iraqi war machine. They want us to finish them off. They don't care about our relations with the Arab world." When he delivered a keynote address at the 1992 Republican

National Convention, known as the Culture War Speech, Buchanan described "a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America".

nations, on Arab television shows and on websites.

In 2004, the United Kingdom set up an all-Parliamentary inquiry into antisemitism, which published its findings in 2006. The inquiry stated that: "Until recently, the prevailing opinion both within the Jewish community and beyond [had been] that antisemitism had receded to the point that it existed only on the margins of society." However, it found a reversal of this progress since 2000 and aimed to investigate the problem, identify the sources of contemporary antisemitism and make recommendations to improve the situation.

- Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

- Christian anti-semitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

- Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least in its classical form—nuanced, in that Jews were a protected class

- Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

- Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism

- Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

In practice, it is difficult to differentiate antisemitism from the general ill-treatment of nations by other nations before the Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

period, but since the adoption of Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

in Europe, antisemitism has undoubtedly been present. The Islamic world has also seen the Jews historically as outsiders. The coming of the scientific and industrial revolution in 19th century Europe bred a new manifestation of antisemitism, based as much upon race as upon religion, culminating in the horrors of the Nazi extermination camps of World War II. The formation of the state of Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

in 1948 has created new antisemitic tensions in the Middle East.

Early animosity towards Jews

Feldman argues that "we must take issue with the communis sensus that the pagan writers are predominantly anti-Semitic.Indeed, he asserts that "one of the great puzzles that has confronted the students of anti-semitism is the alleged shift from pro-Jewish statements found in the first pagan writers who mention the Jews... to the vicious anti-Jewish statements thereafter, beginning with Manetho

Manetho

Manetho was an Egyptian historian and priest from Sebennytos who lived during the Ptolemaic era, approximately during the 3rd century BC. Manetho wrote the Aegyptiaca...

about 270B.C.E. In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

retelling of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

ian prejudices". As examples of pagan writers who spoke positively of Jews, Feldman cites Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, Theophrastus

Theophrastus

Theophrastus , a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age, and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings, and...

, Clearchus of Soli

Clearchus of Soli

Clearchus of Soli was a Greek philosopher of the 4th-3rd century BCE, belonging to Aristotle's Peripatetic school. He was born in Soli in Cyprus....

and Megasthenes

Megasthenes

Megasthenes was a Greek ethnographer in the Hellenistic period, author of the work Indica.He was born in Asia Minor and became an ambassador of Seleucus I of Syria possibly to Chandragupta Maurya in Pataliputra, India. However the exact date of his embassy is uncertain...

. Feldman concedes that, after Manetho, "the picture usually painted is one of universal and virulent anti-Judaism."

The first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment can be traced back to Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

in the 3rd century BCE. Alexandria was home to the largest Jewish community in the world and the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible is a term used by biblical scholars outside of Judaism to refer to the Tanakh , a canonical collection of Jewish texts, and the common textual antecedent of the several canonical editions of the Christian Old Testament...

, was produced there. Manetho

Manetho

Manetho was an Egyptian historian and priest from Sebennytos who lived during the Ptolemaic era, approximately during the 3rd century BC. Manetho wrote the Aegyptiaca...

, an Egyptian priest and historian of that time, wrote scathingly of the Jews and his themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon

Chaeremon

Chaeremon was an Athenian dramatist of the first half of the fourth century BCE. He was generally considered a tragic poet like Choerilus. Aristotle said his works were intended for reading, not for representation...

, Lysimachus

Lysimachus

Lysimachus was a Macedonian officer and diadochus of Alexander the Great, who became a basileus in 306 BC, ruling Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.-Early Life & Career:...

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

Apollonius Molon

Apollonius Molon or Molo of Rhodes , Greek rhetorician who flourished about 70 BC.He was a native of Alabanda, a pupil of Menecles, and settled at Rhodes. He twice visited Rome as an ambassador from Rhodes, and Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Julius Caesar both took lessons from him...

, and in Apion

Apion

Apion , Graeco-Egyptian grammarian, sophist and commentator on Homer, was born at the Siwa Oasis, and flourished in the first half of the 1st century AD....

and Tacitus

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire. The surviving portions of his two major works—the Annals and the Histories—examine the reigns of the Roman Emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Nero and those who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors...

. One of the earliest anti-Jewish edict

Edict

An edict is an announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism. The Pope and various micronational leaders are currently the only persons who still issue edicts.-Notable edicts:...

s, promulgated by Antiochus Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees

Maccabees

The Maccabees were a Jewish rebel army who took control of Judea, which had been a client state of the Seleucid Empire. They founded the Hasmonean dynasty, which ruled from 164 BCE to 63 BCE, reasserting the Jewish religion, expanding the boundaries of the Land of Israel and reducing the influence...

in Judea

Judea

Judea or Judæa was the name of the mountainous southern part of the historic Land of Israel from the 8th century BCE to the 2nd century CE, when Roman Judea was renamed Syria Palaestina following the Jewish Bar Kokhba revolt.-Etymology:The...

.

The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died. The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews being portrayed as misanthropes

Misanthropy

Misanthropy is generalized dislike, distrust, disgust, contempt or hatred of the human species or human nature. A misanthrope, or misanthropist is someone who holds such views or feelings...

. Tcherikover argues that the reason for hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the poleis

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

. Bohak has argued, however, that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, and that many Greeks showed animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.

Statements exhibiting prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

and Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

writers. Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho

Manetho

Manetho was an Egyptian historian and priest from Sebennytos who lived during the Ptolemaic era, approximately during the 3rd century BC. Manetho wrote the Aegyptiaca...

, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers

Leprosy

Leprosy or Hansen's disease is a chronic disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis. Named after physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen, leprosy is primarily a granulomatous disease of the peripheral nerves and mucosa of the upper respiratory tract; skin lesions...

who had been taught by Moses

Moses

Moses was, according to the Hebrew Bible and Qur'an, a religious leader, lawgiver and prophet, to whom the authorship of the Torah is traditionally attributed...

"not to adore the gods." The same themes appeared in the works of Chaeremon

Chaeremon

Chaeremon was an Athenian dramatist of the first half of the fourth century BCE. He was generally considered a tragic poet like Choerilus. Aristotle said his works were intended for reading, not for representation...

, Lysimachus

Lysimachus

Lysimachus was a Macedonian officer and diadochus of Alexander the Great, who became a basileus in 306 BC, ruling Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.-Early Life & Career:...

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

Apollonius Molon

Apollonius Molon or Molo of Rhodes , Greek rhetorician who flourished about 70 BC.He was a native of Alabanda, a pupil of Menecles, and settled at Rhodes. He twice visited Rome as an ambassador from Rhodes, and Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Julius Caesar both took lessons from him...

, and in Apion

Apion

Apion , Graeco-Egyptian grammarian, sophist and commentator on Homer, was born at the Siwa Oasis, and flourished in the first half of the 1st century AD....

and Tacitus

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire. The surviving portions of his two major works—the Annals and the Histories—examine the reigns of the Roman Emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Nero and those who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors...

. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practices" of the Jews and of the "absurdity of their Law," and how Ptolemy Lagus

Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter I , also known as Ptolemy Lagides, c. 367 BC – c. 283 BC, was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great, who became ruler of Egypt and founder of both the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Ptolemaic Dynasty...

was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BC because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

. Edward Flannery describes antisemitism in ancient times as essentially " cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia played out in political settings."

There is a recorded instance of an Ancient Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

ruler, Antiochus Epiphanes, desecrating the Temple in Jerusalem

Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple , refers to one of a series of structures which were historically located on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem, the current site of the Dome of the Rock. Historically, these successive temples stood at this location and functioned as the centre of...

and banning Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision

Circumcision

Male circumcision is the surgical removal of some or all of the foreskin from the penis. The word "circumcision" comes from Latin and ....

, Shabbat

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

observance and the study of Jewish religious books, during the period when Ancient Greece dominated the eastern Mediterranean. Statements exhibiting prejudice towards Jews and their religion can also be found in the works of a few pagan Greek and Roman writers, but the earliest occurrence of antisemitism has been the subject of debate among scholars, largely because different writers use different definitions of antisemitism. The terms "religious antisemitism" and "anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism

Religious antisemitism is a form of antisemitism, which is the prejudice against, or hostility toward, the Jewish people based on hostility to Judaism and to Jews as a religious group...

" are sometimes used to refer to animosity towards Judaism as a religion rather than to Jews defined as an ethnic or racial group.

Roman Empire

Relations between the Jews in Palestine and the occupying Roman EmpireRoman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

were antagonistic from the very start and resulted in several rebellions

Jewish-Roman wars

The Jewish–Roman wars were a series of large-scale revolts by the Jews of Iudaea Province and Eastern Mediterranean against the Roman Empire. Some sources use the term to refer only to the First Jewish–Roman War and Bar Kokhba revolt...

.

Several ancient historians report that in 19 CE the Roman emperor Tiberius

Tiberius

Tiberius , was Roman Emperor from 14 AD to 37 AD. Tiberius was by birth a Claudian, son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla. His mother divorced Nero and married Augustus in 39 BC, making him a step-son of Octavian...

expelled Jews from Rome. According to the Roman historian Suetonius

Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, commonly known as Suetonius , was a Roman historian belonging to the equestrian order in the early Imperial era....

, Tiberius tried to suppress all foreign religions. In the case of Jews, he sent young Jewish men, under the pretence of military service, to provinces noted for their unhealthy climate. He dismissed all other Jews from the city, under threat of life slavery for non-compliance. Josephus

Josephus

Titus Flavius Josephus , also called Joseph ben Matityahu , was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of...

, in his Jewish Antiquities, confirms that Tiberius ordered all Jews to be banished from Rome. Four thousand were sent to Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea . It is an autonomous region of Italy, and the nearest land masses are the French island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia and the Spanish Balearic Islands.The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *sard[],...

but more, who were unwilling to become soldiers, were punished. Cassius Dio reports that Tiberius banished most of the Jews, who had been attempting to convert Romans to their religion. Philo of Alexandria reported that Sejanus

Sejanus

Lucius Aelius Seianus , commonly known as Sejanus, was an ambitious soldier, friend and confidant of the Roman Emperor Tiberius...

, one of Tiberius's lieutenants, may have been a prime mover in the persecution of the Jews.

The Romans refused to permit Jews to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem after its destruction by Titus

Titus

Titus , was Roman Emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, thus becoming the first Roman Emperor to come to the throne after his own father....

in 70 CE, imposed a tax on Jews (Fiscus Judaicus

Fiscus Judaicus

The Fiscus Iudaicus or Fiscus Judaicus was a tax collecting agency instituted to collect the tax imposed on Jews in the Roman Empire after the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE in favor of the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome.-Imposition:The tax was initially imposed by Roman...

) at the same time, ostensibly to finance the Temple of Jupiter in Rome, and renamed Judaea

Iudaea Province

Judaea or Iudaea are terms used by historians to refer to the Roman province that extended over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Israel...

as Syria Palestina. The Jerusalem Talmud

Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud, talmud meaning "instruction", "learning", , is a collection of Rabbinic notes on the 2nd-century Mishnah which was compiled in the Land of Israel during the 4th-5th century. The voluminous text is also known as the Palestinian Talmud or Talmud de-Eretz Yisrael...

relates that, following Bar Kokhba's revolt

Bar Kokhba's revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt 132–136 CE; or mered bar kokhba) against the Roman Empire, was the third major rebellion by the Jews of Judaea Province being the last of the Jewish-Roman Wars. Simon bar Kokhba, the commander of the revolt, was acclaimed as a Messiah, a heroic figure who could restore Israel...

(132–6 CE), the Romans destroyed very many Jews, "killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils." However, some historians argue that Rome suppressed revolts in all its conquered territories and point out that Tiberius expelled all foreign religions from Rome, not just the Jews.

Some accommodation, in fact, was later made with Judaism, and the Jews of the Diaspora

Diaspora

A diaspora is "the movement, migration, or scattering of people away from an established or ancestral homeland" or "people dispersed by whatever cause to more than one location", or "people settled far from their ancestral homelands".The word has come to refer to historical mass-dispersions of...

had privileges that others did not. Unlike other subjects of the Roman Empire, they had the right to maintain their religion and were not expected to accommodate themselves to local customs. Even after the First Jewish–Roman War, the Roman authorities refused to rescind Jewish privileges in some cities. And although Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

outlawed circumcision as a mutilation normally visited on people unable to consent, he later exempted the Jews. According to the 18th century historian Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon was an English historian and Member of Parliament...

, there was greater tolerance from about 160 CE. Between 355 and 363 CE, permission was granted by Julian the Apostate

Julian the Apostate

Julian "the Apostate" , commonly known as Julian, or also Julian the Philosopher, was Roman Emperor from 361 to 363 and a noted philosopher and Greek writer....

to rebuild the Second Temple of Jerusalem.

It has been argued that European antisemitism has its roots in Roman policy.

The New Testament and early Christianity

Although the majority of the New TestamentNew Testament

The New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

was written, ostensibly, by Jews who became followers of Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

, there are a number of passages in the New Testament that some see as antisemitic, or that have been used for antisemitic purposes, including:

- Jesus speaking to a group of PhariseesPhariseesThe Pharisees were at various times a political party, a social movement, and a school of thought among Jews during the Second Temple period beginning under the Hasmonean dynasty in the wake of...

: "I know that you are descendants of AbrahamAbrahamAbraham , whose birth name was Abram, is the eponym of the Abrahamic religions, among which are Judaism, Christianity and Islam...

; yet you seek to kill me, because my word finds no place in you... You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth, because there is no truth in him." (John 8:37-39, 44-47, RSVRevised Standard VersionThe Revised Standard Version is an English translation of the Bible published in the mid-20th century. It traces its history to William Tyndale's New Testament translation of 1525. The RSV is an authorized revision of the American Standard Version of 1901...

)

- Saint StephenSaint StephenSaint Stephen The Protomartyr , the protomartyr of Christianity, is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Churches....

speaking before a synagogue council just before his execution: "You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy SpiritHoly SpiritHoly Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of the Hebrew Bible, but understood differently in the main Abrahamic religions.While the general concept of a "Spirit" that permeates the cosmos has been used in various religions Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of...

. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did your fathers not persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did not keep it." (Acts 7:51-53, RSV)

Some biblical scholars point out that Jesus and Stephen are presented as Jews speaking to other Jews, and that their use of broad accusations against Israel is borrowed from Moses

Moses

Moses was, according to the Hebrew Bible and Qur'an, a religious leader, lawgiver and prophet, to whom the authorship of the Torah is traditionally attributed...

and the later Jewish prophets. Other scholars hold that verses like these reflect Jewish-Christian tensions that were emerging in the late 1st or early 2nd century. Today, nearly all Christian denominations place little emphasis on verses such as these, and reject their misuse.

After Jesus' death, the New Testament portrays the Jewish religious authorities in Jerusalem as hostile to Jesus' followers, and as occasionally using force against them. Stephen is executed by stoning. Before his conversion, Saul puts followers of Jesus in prison. After his conversion, Saul

Paul of Tarsus

Paul the Apostle , also known as Saul of Tarsus, is described in the Christian New Testament as one of the most influential early Christian missionaries, with the writings ascribed to him by the church forming a considerable portion of the New Testament...

is whipped at various times by Jewish authorities. He is accused by Jewish authorities before the Roman courts. However, opposition by gentiles is also described, and more generally, there are widespread references in the New Testament to the suffering experienced by Jesus' followers at the hands of others, particularly the Romans.