Anti-Judaism

Encyclopedia

Religious antisemitism is a form of antisemitism, which is the prejudice against, or hostility toward, the Jewish people based on hostility to Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

and to Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

as a religious group. It is sometimes called theological antisemitism, and distinguished from anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism

Religious antisemitism is a form of antisemitism, which is the prejudice against, or hostility toward, the Jewish people based on hostility to Judaism and to Jews as a religious group...

, which is usually described as a critical rejection of Jewish principles and beliefs.

Reuven Firestone notes that "negative assessments and even condemnation of prior religions and their adherents occur in all three scriptures of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.".According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion ... a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism ... . From the Enlightenment onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews... Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

Origins of religious antisemitism

Father Edward FlanneryEdward Flannery

Edward H. Flannery was a priest in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Providence, and the author of The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism, first published in 1965....

in his The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism, traces the first clear examples of specific anti-Jewish sentiment back to Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

in the third century BC. Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho

Manetho

Manetho was an Egyptian historian and priest from Sebennytos who lived during the Ptolemaic era, approximately during the 3rd century BC. Manetho wrote the Aegyptiaca...

, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers

Leprosy

Leprosy or Hansen's disease is a chronic disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis. Named after physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen, leprosy is primarily a granulomatous disease of the peripheral nerves and mucosa of the upper respiratory tract; skin lesions...

who had been taught by Moses

Moses

Moses was, according to the Hebrew Bible and Qur'an, a religious leader, lawgiver and prophet, to whom the authorship of the Torah is traditionally attributed...

"not to adore the gods." The same themes appeared in the works of Chaeremon

Chaeremon

Chaeremon was an Athenian dramatist of the first half of the fourth century BCE. He was generally considered a tragic poet like Choerilus. Aristotle said his works were intended for reading, not for representation...

, Lysimachus

Lysimachus

Lysimachus was a Macedonian officer and diadochus of Alexander the Great, who became a basileus in 306 BC, ruling Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.-Early Life & Career:...

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

Apollonius Molon

Apollonius Molon or Molo of Rhodes , Greek rhetorician who flourished about 70 BC.He was a native of Alabanda, a pupil of Menecles, and settled at Rhodes. He twice visited Rome as an ambassador from Rhodes, and Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Julius Caesar both took lessons from him...

, and in Apion

Apion

Apion , Graeco-Egyptian grammarian, sophist and commentator on Homer, was born at the Siwa Oasis, and flourished in the first half of the 1st century AD....

and Tacitus

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire. The surviving portions of his two major works—the Annals and the Histories—examine the reigns of the Roman Emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Nero and those who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors...

. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practices" of the Jews and of the "absurdity of their Law," and how Ptolemy Lagus

Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter I , also known as Ptolemy Lagides, c. 367 BC – c. 283 BC, was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great, who became ruler of Egypt and founder of both the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Ptolemaic Dynasty...

was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BC because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

.

Christian antisemitism

Religious antisemitism is also known as anti-Judaism. As the name implies, it was the practice of JudaismJudaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

itself that was the defining characteristic of the antisemitic attacks. Under this version of antisemitism, attacks would often stop if Jews stopped practicing or changed their public faith, especially by conversion

Religious conversion

Religious conversion is the adoption of a new religion that differs from the convert's previous religion. Changing from one denomination to another within the same religion is usually described as reaffiliation rather than conversion.People convert to a different religion for various reasons,...

to the official or right religion, and sometimes, liturgical exclusion of Jewish converts (the case of Christianized Marranosor Iberian Jews in the late 15th century and 16th century convicted of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs).

New Testament and antisemitism

Frederick Schweitzer and Marvin Perry write that the authors of the gospel accounts sought to place responsibility for the Crucifixion of JesusCrucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion of Jesus and his ensuing death is an event that occurred during the 1st century AD. Jesus, who Christians believe is the Son of God as well as the Messiah, was arrested, tried, and sentenced by Pontius Pilate to be scourged, and finally executed on a cross...

and his death on Jews, rather than the Roman emperor or Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilatus , known in the English-speaking world as Pontius Pilate , was the fifth Prefect of the Roman province of Judaea, from AD 26–36. He is best known as the judge at Jesus' trial and the man who authorized the crucifixion of Jesus...

. As a result, Christians for centuries viewed Jews as "the Christ Killers". The destruction of the Second Temple

Second Temple

The Jewish Second Temple was an important shrine which stood on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem between 516 BCE and 70 CE. It replaced the First Temple which was destroyed in 586 BCE, when the Jewish nation was exiled to Babylon...

was seen as judgment from God to the Jews for that death, and Jews were seen as "a people condemned forever to suffer exile and degradation". According to historian Edward H. Flannery, the Gospel of John

Gospel of John

The Gospel According to John , commonly referred to as the Gospel of John or simply John, and often referred to in New Testament scholarship as the Fourth Gospel, is an account of the public ministry of Jesus...

in particular contains many verses that refer to Jews in a pejorative manner.

In , Paul states that the Churches in Judea had been persecuted by the Jews who killed Jesus and that such people displease God, oppose all men, and had prevented Paul from speaking to the gentile nations concerning the New Testament message. Described by Hyam Maccoby

Hyam Maccoby

Hyam Maccoby was a British Jewish scholar and dramatist specializing in the study of the Jewish and Christian religious tradition. His grandfather and namesake was Rabbi Hyam Maccoby , better known as the "Kamenitzer Maggid," a passionate religious Zionist and advocate of vegetarianism and animal...

as "the most explicit outburst against Jews in Paul's Epistles", these verses have repeatedly been employed for antisemitic purposes. Maccoby views it as one of Paul's innovations responsible for creating Christian antisemitism, though he notes that some have argued these particular verses are later interpolations not written by Paul. Craig Blomberg

Craig Blomberg

Craig L. Blomberg is an American New Testament scholar. Since 1986 he has been Distinguished Professor of the New Testament at Denver Seminary in Colorado.-Life:...

argues that viewing them as antisemitic is a mistake, but "understandable in light of [Paul's] harsh words". In his view, Paul is not condemning all Jews forever, but merely those he believed had specifically persecuted the prophets, Jesus, or the 1st century church. Blomberg sees Paul's words here as no different in kind than the harsh words the prophets of the Old Testament have for the Jews.

The Codex Sinaiticus

Codex Sinaiticus

Codex Sinaiticus is one of the four great uncial codices, an ancient, handwritten copy of the Greek Bible. It is an Alexandrian text-type manuscript written in the 4th century in uncial letters on parchment. Current scholarship considers the Codex Sinaiticus to be one of the best Greek texts of...

contains two extra books in the New Testament – the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas

Epistle of Barnabas

The Epistle of Barnabas is a Greek epistle containing twenty-one chapters, preserved complete in the 4th century Codex Sinaiticus where it appears at the end of the New Testament...

. The latter emphasizes the claim that it was the Jews, not the Romans, who killed Jesus, and is full of antisemitism. The Epistle of Barnabas was not accepted as part of the canon; Professor Bart Ehrman has stated "the suffering of Jews in the subsequent centuries would, if possible, have been even worse had the Epistle of Barnabas remained".

Early Christianity

A number of early and influential Church works — such as the dialogues of Justin MartyrJustin Martyr

Justin Martyr, also known as just Saint Justin , was an early Christian apologist. Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and a dialogue survive. He is considered a saint by the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church....

, the homilies of John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom , Archbishop of Constantinople, was an important Early Church Father. He is known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and political leaders, the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, and his ascetic...

, and the testimonies of church father Cyprian

Cyprian

Cyprian was bishop of Carthage and an important Early Christian writer, many of whose Latin works are extant. He was born around the beginning of the 3rd century in North Africa, perhaps at Carthage, where he received a classical education...

— are strongly anti-Jewish.

During a discussion on the celebration of Easter

Easter

Easter is the central feast in the Christian liturgical year. According to the Canonical gospels, Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion. His resurrection is celebrated on Easter Day or Easter Sunday...

during the First Council of Nicaea

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in Nicaea in Bithynia by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325...

in 325 CE, Roman emperor Constantine said,

...it appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly afflicted with blindness of soul. (...) Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way.

Prejudice against Jews in the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

was formalized in 438, when the Code of Theodosius II

Theodosius II

Theodosius II , commonly surnamed Theodosius the Younger, or Theodosius the Calligrapher, was Byzantine Emperor from 408 to 450. He is mostly known for promulgating the Theodosian law code, and for the construction of the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople...

established Christianity as the only legal religion in the Roman Empire. The Justinian Code a century later stripped Jews of many of their rights, and Church councils throughout the 6th and 7th century, including the Council of Orleans, further enforced anti-Jewish provisions. These restrictions began as early as 305, when, in Elvira, (now Granada

Granada

Granada is a city and the capital of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of three rivers, the Beiro, the Darro and the Genil. It sits at an elevation of 738 metres above sea...

), a Spanish town in Andalucia, the first known laws of any church council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews unless the Jew first converted to Catholicism. Jews were forbidden to extend hospitality to Catholics. Jews could not keep Catholic Christian concubines and were forbidden to bless the fields of Catholics. In 589, in Catholic Iberia

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

, the Third Council of Toledo

Third Council of Toledo

The Third Council of Toledo marks the entry of Catholic Christianity into the rule of Visigothic Spain, and the introduction into Western Christianity of the filioque clause...

ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and Catholic be baptized by force. By the Twelfth Council of Toledo (681) a policy of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated (Liber Judicum, II.2 as given in Roth). Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted to Roman Catholicism.

Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Antisemitism was widespread in Europe during the Middle AgesMiddle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

. In those times, a main cause of prejudice against Jews in Europe was the religious one. Although not part of Roman Catholicdogma

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

, many Christians, including members of the clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

, held the Jewish peoplecollectively responsible for the death of Jesus, a practice originated by Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and a great authority in Early Christianity: Jerome, speaking of the Old Testament canon established by Melito, quotes Tertullian to the effect that he was esteemed a prophet by many of the faithful...

.

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed the doors for many professions to the Jews, pushing them into occupations considered socially inferior such as accounting, rent-collecting and moneylending, which was tolerated then as a "necessary evil

Consequentialism

Consequentialism is the class of normative ethical theories holding that the consequences of one's conduct are the ultimate basis for any judgment about the rightness of that conduct...

". During the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

, Jews were accused as being the cause, and were often killed. There were expulsions of Jews from England, France, Germany, Portugal and Spain during the Middle Ages as a result of antisemitism.

Judensau

Judensau is an image of Jews in obscene contact with a large sow , which in Judaism is an unclean animal, that appeared during the 13th century in Germany and some other European countries; its popularity lasted for over 600 years.-Background and images:The Jewish prohibition of pork comes from...

was the derogatory and dehumanizing imagery of Jews that appeared around the 13th century. Its popularity lasted for over 600 years and was revived by the Nazis. The Jews, typically portrayed in obscene contact with unclean animals

Unclean animals

Unclean animals, in some religions, are animals whose consumption or handling is labeled a taboo. According to these religion's dogmas, persons who handle such animals may need to purify themselves to get rid of their uncleanness.-Judaism:...

such as pig

Pig

A pig is any of the animals in the genus Sus, within the Suidae family of even-toed ungulates. Pigs include the domestic pig, its ancestor the wild boar, and several other wild relatives...

s or owl

Owl

Owls are a group of birds that belong to the order Strigiformes, constituting 200 bird of prey species. Most are solitary and nocturnal, with some exceptions . Owls hunt mostly small mammals, insects, and other birds, although a few species specialize in hunting fish...

s or representing a devil

Devil

The Devil is believed in many religions and cultures to be a powerful, supernatural entity that is the personification of evil and the enemy of God and humankind. The nature of the role varies greatly...

, appeared on cathedral

Cathedral

A cathedral is a Christian church that contains the seat of a bishop...

or church ceilings, pillars, utensils, etchings, etc. Often, the images combined several antisemitic motifs and included derisive prose or poetry.

"Dozens of Judensaus... intersect with the portrayal of the Jew as a Christ killerDeicideDeicide is the killing of a god. The term deicide was coined in the 17th century from medieval Latin *deicidium, from de-us "god" and -cidium "cutting, killing")...

. Various illustrations of the murder of Simon of TrentSimon of TrentSimon of Trent ; also known as Simeon; was a boy from the city of Trento, Italy whose disappearance was blamed on the leaders of the city's Jewish community based on their confessions under torture, causing a major blood libel in Europe.-Background:Shortly before Simon went missing, Bernardine of...

blended images of Judensau, the devilDevilThe Devil is believed in many religions and cultures to be a powerful, supernatural entity that is the personification of evil and the enemy of God and humankind. The nature of the role varies greatly...

, the murder of little Simon himself, and the CrucifixionCrucifixionCrucifixion is an ancient method of painful execution in which the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross and left to hang until dead...

. In the 17th-century engraving from Frankfurt... a well-dressed, very contemporary-looking Jew has mounted the sow backward and holds her tail, while a second Jew sucks at her milk and a third eats her feces. The horned devil, himself wearing a Jewish badgeYellow badgeThe yellow badge , also referred to as a Jewish badge, was a cloth patch that Jews were ordered to sew on their outer garments in order to mark them as Jews in public. It is intended to be a badge of shame associated with antisemitism...

, looks on and the butchered Simon, splayed as if on a cross, appears on a panel above."

In Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

's "Merchant of Venice", considered to be one of the greatest romantic comedies of all time, the villain Shylock

Shylock

Shylock is a fictional character in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice.-In the play:In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock is a Jewish moneylender who lends money to his Christian rival, Antonio, setting the security at a pound of Antonio's flesh...

was a Jewish moneylender. By the end of the play he is mocked on the streets after his daughter elopes with a Christian. Shylock, then, compulsorily converts to Christianity as a part of a deal gone wrong. This has raised profound implications regarding Shakespeare and antisemitism.

During the Middle Ages, the story of Jephonias, the Jew who tried to overturn Mary's funeral bier, changed from his converting to Christianity into his simply having his hands cut off by an angel.

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

.

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden.

19th century

Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII , born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti, was a monk, theologian and bishop, who reigned as Pope from 14 March 1800 to 20 August 1823.-Early life:...

(1800–1823) had the walls of the Jewish Ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were released by Napoleon

Napoleon and the Jews

The ascendancy of Napoleon Bonaparte proved to be an important event in European Jewish emancipation from old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited Jews' rights to property, worship, and careers.- Napoleon's Law and the Jews :...

, and Jews were restricted to the Ghetto through the end of the Papal States in 1870.

Additionally, official organizations such as the Jesuits banned candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is clear that their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have belonged to the Catholic Church" until 1946. Brown University historian David Kertzer

David Kertzer

David I. Kertzer is Paul Dupee, Jr. University Professor of Social Science, Professor of Anthropology , Professor of History , and Professor of Italian Studies at Brown University. He became Provost of Brown on July 1, 2006...

, working from the Vatican archive, has further argued in his book The Popes Against the Jews that in the 19th century and early 20th century the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

adhered to a distinction between "good antisemitism" and "bad antisemitism".

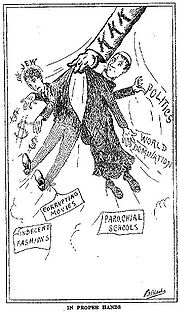

The "bad" kind promoted hatred of Jews because of their descent. This was considered un-Christian because the Christian message was intended for all of humanity regardless of ethnicity; anyone could become a Christian. The "good" kind criticized alleged Jewish conspiracies to control newspapers, banks, and other institutions, to care only about accumulation of wealth, etc. Many Catholic bishops wrote articles criticizing Jews on such grounds, and, when accused of promoting hatred of Jews, would remind people that they condemned the "bad" kind of antisemitism. Kertzer's work is not, therefore, without critics; scholar of Jewish-Christian relations Rabbi David G. Dalin, for example, criticized Kertzer in the Weekly Standard for using evidence selectively.

The Holocaust

The Nazis used Martin LutherMartin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

's book, On the Jews and Their Lies (1543), to claim a moral righteousness for their ideology. Luther even went so far as to advocate the murder of those Jews who refused to convert to Christianity, writing that "we are at fault in not slaying them"

Archbishop Robert Runcie

Robert Runcie

Robert Alexander Kennedy Runcie, Baron Runcie, PC, MC was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1980 to 1991.-Early life:...

has asserted that: "Without centuries of Christian antisemitism, Hitler's passionate hatred would never have been so fervently echoed...because for centuries Christians have held Jews collectively responsible for the death of Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

. On Good Friday Jews, have in times past, cowered behind locked doors with fear of a Christian mob seeking 'revenge' for deicide. Without the poisoning of Christian minds through the centuries, the Holocaust is unthinkable." The dissident Catholic priest Hans Küng

Hans Küng

Hans Küng is a Swiss Catholic priest, theologian, and prolific author. Since 1995 he has been President of the Foundation for a Global Ethic . Küng is "a Catholic priest in good standing", but the Vatican has rescinded his authority to teach Catholic theology...

has written that "Nazi anti-Judaism was the work of godless, anti-Christian criminals. But it would not have been possible without the almost two thousand years' pre-history of 'Christian' anti-Judaism..."

The document Dabru Emet

Dabru Emet

The Dabru Emet is a document concerning the relationship between Christianity and Judaism. It was signed by over 220 rabbis and intellectuals from all branches of Judaism, as individuals and not as representing any organisation or stream of Judaism.The Dabru Emet was first published on September...

was issued by many American Jewish scholars in 2000 as a statement about Jewish-Christian relations. This document states,

"Nazism was not a Christian phenomenon. Without the long history of Christian anti-Judaism and Christian violence against Jews, Nazi ideology could not have taken hold nor could it have been carried out. Too many Christians participated in, or were sympathetic to, Nazi atrocities against Jews. Other Christians did not protest sufficiently against these atrocities. But Nazism itself was not an inevitable outcome of Christianity."

According to American historian

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

Lucy Dawidowicz

Lucy Dawidowicz

Lucy Schildkret Dawidowicz was an American historian and an author of books on modern Jewish history, in particular books on the Holocaust.-Life:...

, antisemitism has a long history within Christianity. The line of "antisemitic descent" from Luther, the author of On the Jews and Their Lies, to Hitler is "easy to draw." In her The War Against the Jews

The War Against the Jews

The War Against the Jews is a 1975 book authored by Lucy Dawidowicz. The book researches the Holocaust of the European Jewry during World War II....

, 1933-1945, she contends that Luther and Hitler were obsessed by the "demonologized universe" inhabited by Jews. Dawidowicz writes that the similarities between Luther's anti-Jewish writings and modern antisemitism are no coincidence, because they derived from a common history of Judenhass, which can be traced to Haman's

Haman (Bible)

Haman is the main antagonist in the Book of Esther, who, according to Old Testament tradition, was a 5th Century BC noble and vizier of the Persian empire under King Ahasuerus, traditionally identified as Artaxerxes II...

advice to Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus is a name used several times in the Hebrew Bible, as well as related legends and Apocrypha. This name is applied in the Hebrew Scriptures to three rulers...

. Although modern German antisemitism also has its roots in German nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

and the liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

revolution of 1848, Christian

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

antisemitism she writes is a foundation that was laid by the Roman CatholicChurch and "upon which Luther built." Dawidowicz' allegations and positions are criticized and not accepted by most historians however. For example, in "Studying the Jew" Alan Steinweis notes that, "Old-fashioned antisemitism, Hitler argued, was insufficient, and would lead only to pogroms, which contribute little to a permanent solution. This is why, Hitler maintained, it was important to promote 'an antisemitism of reason,' one that acknowledged the racial basis of Jewry." Interviews with Nazis by other historians show that the Nazis thought that their views were rooted in biology, not historical prejudices. For example, "S. became a missionary for this biomedical vision... As for anti-Semitic attitudes and actions, he insisted that 'the racial question... [and] resentment of the Jewish race... had nothing to do with medieval anti-Semitism...' That is, it was all a matter of scientific biology and of community."

Post-Holocaust

The Second Vatican CouncilSecond Vatican Council

The Second Vatican Council addressed relations between the Roman Catholic Church and the modern world. It was the twenty-first Ecumenical Council of the Catholic Church and the second to be held at St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. It opened under Pope John XXIII on 11 October 1962 and closed...

, the Nostra Aetate

Nostra Aetate

Nostra Aetate is the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions of the Second Vatican Council. Passed by a vote of 2,221 to 88 of the assembled bishops, this declaration was promulgated on October 28, 1965, by Pope Paul VI.The first draft, entitled "Decretum de...

document, and the efforts of Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

have helped reconcile Jews and Catholicism in recent decades, however. According to Roman Catholic Holocaust scholar Michael Phayer

Michael Phayer

Michael Phayer, born 1935, is a historian and professor emeritus at Marquette University in Milwaukee and has written on 19th and 20th century European history and the Holocaust....

the Church as a whole recognized its failings during the council when it corrected the traditional beliefs of the Jews having committed deicide and affirmed that they remained God's chosen people.

In 1994, the Church Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America is a mainline Protestant denomination headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA officially came into existence on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three churches. As of December 31, 2009, it had 4,543,037 baptized members, with 2,527,941 of them...

, the largest Lutheran denomination in the United States and a member of the Lutheran World Federation

Lutheran World Federation

The Lutheran World Federation is a global communion of national and regional Lutheran churches headquartered in the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva, Switzerland. The federation was founded in the Swedish city of Lund in the aftermath of the Second World War in 1947 to coordinate the activities of the...

publicly rejected Luther's antisemitic writings.

Accusations of deicide

Though never a part of ChristianChristian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

dogma

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

, many Christians, including members of the clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

, held the Jewish people under an antisemitic canard

Antisemitic canard

An antisemitic canard is a false story inciting antisemitism. Despite being thoroughly disproved, antisemitic canards are often part of broader theories of Jewish conspiracies. According to Kenneth S. Stern,Historically, Jews have not fared well around conspiracy theories. Such ideas fuel...

to be collectively responsible for deicide

Deicide

Deicide is the killing of a god. The term deicide was coined in the 17th century from medieval Latin *deicidium, from de-us "god" and -cidium "cutting, killing")...

, the killing of Jesus

Jewish deicide

Jewish deicide is a belief that places the responsibility for the death of Jesus on the Jewish people as a whole.This deicide accusation is expressed in the ethnoreligious slur "Christ-killer." As a part of Second Vatican Council , the Roman Catholic Church under Pope Paul VI issued a declaration...

, whom they believed to be the son of God.

According to this interpretation, the Jews present at Jesus' death as well as the Jewish people collectively and for all time had committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing. The accusation has been the most powerful warrant for antisemitism by Christians.

Passion play

Passion play

A Passion play is a dramatic presentation depicting the Passion of Jesus Christ: his trial, suffering and death. It is a traditional part of Lent in several Christian denominations, particularly in Catholic tradition....

s are dramatic stagings representing the trial and death of Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

and have historically been used in remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent

Lent

In the Christian tradition, Lent is the period of the liturgical year from Ash Wednesday to Easter. The traditional purpose of Lent is the preparation of the believer – through prayer, repentance, almsgiving and self-denial – for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and...

. These plays historically blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus

Deicide

Deicide is the killing of a god. The term deicide was coined in the 17th century from medieval Latin *deicidium, from de-us "god" and -cidium "cutting, killing")...

in a polemic

Polemic

A polemic is a variety of arguments or controversies made against one opinion, doctrine, or person. Other variations of argument are debate and discussion...

al fashion, depicting a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to crucifixion

Crucifixion

Crucifixion is an ancient method of painful execution in which the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross and left to hang until dead...

and a Jewish leader assuming eternal collective guilt for the crowd for the murder of Jesus, which, The Boston Globe

The Boston Globe

The Boston Globe is an American daily newspaper based in Boston, Massachusetts. The Boston Globe has been owned by The New York Times Company since 1993...

explains, "for centuries prompted vicious attacks — or pogrom

Pogrom

A pogrom is a form of violent riot, a mob attack directed against a minority group, and characterized by killings and destruction of their homes and properties, businesses, and religious centres...

s — on Europe's Jewish communities".

Islamic antisemitism

With the origin of IslamIslam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

in the 7th century AD and its rapid spread in the Arabian peninsula

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula is a land mass situated north-east of Africa. Also known as Arabia or the Arabian subcontinent, it is the world's largest peninsula and covers 3,237,500 km2...

and beyond, Jews (and many other peoples) came to be subject to the rule of Muslim rulers. The quality of the rule varied considerably in different periods, as did the attitudes of the rulers, government officials, clergy and general population to various subject peoples from time to time, which was reflected in their treatment of these subjects.

Various definitions of antisemitism in the context of Islam are given. The extent of antisemitism among Muslims varies depending on the chosen definition:

- Scholars like Claude CahenClaude CahenClaude Cahen was a French Marxist orientalist and historian. He specialized in the studies of the Islamic Middle Ages, Muslim sources about the Crusades, and social history of the medieval Islamic society ....

and Shelomo Dov GoiteinShelomo Dov GoiteinShelomo Dov Goitein was a German-Jewish ethnographer, historian and Arabist known for his research on Jewish life in the Islamic Middle Ages.-Biography:...

define it to be the animosity specifically applied to Jews only and do not include discriminations practiced against Non-Muslims in general. For these scholars, antisemitism in Medieval Islam has been local and sporadic rather than general and endemic [Shelomo Dov Goitein], not at all present [Claude Cahen], or rarely present. - According to Bernard LewisBernard LewisBernard Lewis, FBA is a British-American historian, scholar in Oriental studies, and political commentator. He is the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University...

, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." For Lewis, from the late 19th century, movements appear among Muslims of which for the first time one can legitimately use the technical term antisemitic. However, he describes demonizing beliefs, anti-Jewish discrimination and systematic humiliations, as an "inherent" part of the traditional Muslim world, even if violent persecutions were relatively rare.

Pre-modern times

According to Jane Gerber, "the Muslim is continually influenced by the theological threads of anti-Semitism embedded in the earliest chapters of Islamic history." In the light of the Jewish defeat at the hands of Muhammad, Muslims traditionally viewed Jews with contempt and as objects of ridicule. Jews were seen as hostile, cunning, and vindictive, but nevertheless weak and ineffectual. Cowardice was the quality most frequently attributed to Jews. Another stereotype associated with the Jews was their alleged propensity to trickery and deceit. While most anti-Jewish polemicists saw those qualities as inherently Jewish, ibn KhaldunIbn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldūn or Ibn Khaldoun was an Arab Tunisian historiographer and historian who is often viewed as one of the forerunners of modern historiography, sociology and economics...

attributed them to the mistreatment of Jews at the hands of the dominant nations. For that reason, says ibn Khaldun, Jews "are renowned, in every age and climate, for their wickedness and their slyness".

Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

's attitude towards Jews was basically neutral at the beginning. During his lifetime, Jews lived on the Arabian Peninsula

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula is a land mass situated north-east of Africa. Also known as Arabia or the Arabian subcontinent, it is the world's largest peninsula and covers 3,237,500 km2...

, especially in and around Medina

Medina

Medina , or ; also transliterated as Madinah, or madinat al-nabi "the city of the prophet") is a city in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia, and serves as the capital of the Al Madinah Province. It is the second holiest city in Islam, and the burial place of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and...

. They refused to accept Muhammad's teachings. Eventually he fought them, defeated them, and most of them were killed. The traditional biographies of Muhammad describe the expulsion of the Banu Qaynuqa

Banu Qaynuqa

The Banu Qaynuqa was one of the three main Jewish tribes living in the 7th century of Medina, now in Saudi Arabia...

in the post Badr

Battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr , fought Saturday, March 13, 624 AD in the Hejaz region of western Arabia , was a key battle in the early days of Islam and a turning point in Muhammad's struggle with his opponents among the Quraish in Mecca...

period, after a marketplace quarrel broke out between the Muslims and Jews in Medina

Medina

Medina , or ; also transliterated as Madinah, or madinat al-nabi "the city of the prophet") is a city in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia, and serves as the capital of the Al Madinah Province. It is the second holiest city in Islam, and the burial place of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and...

and Muhammad's negotiations with the tribe failed.

Following his defeat in the Battle of Uhud

Battle of Uhud

The Battle of Uhud was fought on March 19, 625 at the valley located in front of Mount Uhud, in what is now northwestern Arabia. It occurred between a force from the Muslim community of Medina led by the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and a force led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb from Mecca, the town from...

, Muhammad said he received a divine revelation that the Jewish tribe of the Banu Nadir

Banu Nadir

The Banu Nadir were a Jewish tribe who lived in northern Arabia until the 7th century at the oasis of Yathrib . The tribe challenged Muhammad as the leader of Medina. and planned along with allied nomads to attack Muhammad and were expelled from Medina as a result. The Banu Nadir then planned the...

wanted to assassinate him. Muhammad besieged the Banu Nadir and expelled them from Medina. Muhammad also attacked the Jews of the Khaybar

Battle of Khaybar

The Battle of Khaybar was fought in the year 629 between Muhammad and his followers against the Jews living in the oasis of Khaybar, located from Medina in the north-western part of the Arabian peninsula, in modern-day Saudi Arabia....

oasis near Medina and defeated them, after betraying the Muslims in a war time, allowing them to stay in the oasis only on the condition that they deliver one-half of their annual produce to Muslims.

Anti-Jewish sentiments usually flared up at times of Muslim political or military weakness or when Muslims felt that some Jews had overstepped the boundaries of humiliation prescribed to them by Islamic law. In Spain, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their anti-Jewish writings on the latter allegation. This was also the chief motivating factor behind the massacres of Jews in Granada

Granada

Granada is a city and the capital of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of three rivers, the Beiro, the Darro and the Genil. It sits at an elevation of 738 metres above sea...

in 1066, when nearly 3,000 Jews were killed, and in Fez

Fes, Morocco

Fes or Fez is the second largest city of Morocco, after Casablanca, with a population of approximately 1 million . It is the capital of the Fès-Boulemane region....

in 1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465.

Islamic law does not differentiate between Jews and Christians in their status as dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

s. According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, FBA is a British-American historian, scholar in Oriental studies, and political commentator. He is the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University...

, the normal practice of Muslim governments until modern times was consistent with this aspect of sharia

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

law. This view is countered by Jane Gerber, who maintains that of all dhimmis, Jews had the lowest status. Gerber maintains that this situation was especially pronounced in the latter centuries in the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, where Christian communities enjoyed protection from the European countries, unavailable to the Jews. For example, in 18th-century Damascus

Damascus

Damascus , commonly known in Syria as Al Sham , and as the City of Jasmine , is the capital and the second largest city of Syria after Aleppo, both are part of the country's 14 governorates. In addition to being one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Damascus is a major...

, a Muslim noble held a festival, inviting to it all social classes in descending order, according to their social status: the Jews outranked only the peasants and prostitutes.

Jews in Islamic texts

Leon PoliakovLeon Poliakov

Léon Poliakov was a French historian who wrote extensively on the Holocaust and anti-Semitism.Born into a Russian Jewish family, Poliakov lived in Italy and Germany until he settled in France....

, Walter Laqueur

Walter Laqueur

Walter Zeev Laqueur is an American historian and political commentator. He was born in Breslau, Germany , to a Jewish family. In 1938, Laqueur left Germany for the British Mandate of Palestine. His parents, who were unable to leave, became victims of the Holocaust...

, and Jane Gerber

Jane Gerber

Jane S. Gerber is a professor of Jewish history and the director of the Institute for Sephardic Studies at City University of New York. She is also the author of many books, including Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience, and other books. Gerber was formerly the president of the...

, suggest that later passages in the Qur'an

Qur'an

The Quran , also transliterated Qur'an, Koran, Alcoran, Qur’ān, Coran, Kuran, and al-Qur’ān, is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God . It is regarded widely as the finest piece of literature in the Arabic language...

contain very sharp attacks on Jews for their refusal to recognize Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

as a prophet

Prophet

In religion, a prophet, from the Greek word προφήτης profitis meaning "foreteller", is an individual who is claimed to have been contacted by the supernatural or the divine, and serves as an intermediary with humanity, delivering this newfound knowledge from the supernatural entity to other people...

of God

God

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

. There are also Qur'anic verses, particularly from the earliest Qur'anic surah

Sura

A sura is a division of the Qur'an, often referred to as a chapter. The term chapter is sometimes avoided, as the suras are of unequal length; the shortest sura has only three ayat while the longest contains 286 ayat...

s, showing respect for the Jews (e.g. see ) and preaching tolerance (e.g. see ). This positive view tended to disappear in the later Surahs. Taking it all together, the Qur'an differentiates between "good and bad" Jews, Poliakov states. Laqueur argues that the conflicting statements about Jews in the Muslim holy text has defined Arab

Arab

Arab people, also known as Arabs , are a panethnicity primarily living in the Arab world, which is located in Western Asia and North Africa. They are identified as such on one or more of genealogical, linguistic, or cultural grounds, with tribal affiliations, and intra-tribal relationships playing...

and Muslim attitude towards Jews to this day, especially during periods of rising Islamic fundamentalism

Islamic fundamentalism

Islamic fundamentalism is a term used to describe religious ideologies seen as advocating a return to the "fundamentals" of Islam: the Quran and the Sunnah. Definitions of the term vary. According to Christine L...

.

Differences with Christianity

Bernard LewisBernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, FBA is a British-American historian, scholar in Oriental studies, and political commentator. He is the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University...

holds that Muslims were not antisemitic in the way Christians were for the most part because:

- The gospels are not part of the educational system in Muslim society and therefore Muslims are not brought up with the stories of Jewish deicideJewish deicideJewish deicide is a belief that places the responsibility for the death of Jesus on the Jewish people as a whole.This deicide accusation is expressed in the ethnoreligious slur "Christ-killer." As a part of Second Vatican Council , the Roman Catholic Church under Pope Paul VI issued a declaration...

; on the contrary the notion of deicide is rejected by the Qur'an as a blasphemous absurdity. - Muhammad and his early followers were not Jews and therefore they did not present themselves as the true Israel or feel threatened by survival of the old Israel.

- The Qur'an was not viewed by Muslims as a fulfillment of the Hebrew BibleHebrew BibleThe Hebrew Bible is a term used by biblical scholars outside of Judaism to refer to the Tanakh , a canonical collection of Jewish texts, and the common textual antecedent of the several canonical editions of the Christian Old Testament...

, but rather as a restorer of its original messages that had been distorted over time. Thus no clash of interpretations between Judaism and Islam could arise. - Muhammad was not killed by the Jewish community and he was victorious in the clash with the Jewish community in Medina.

- Muhammad did not claim to have been Son of God or Messiah but only a prophet; a claim which Jews repudiated less.

- Muslims saw the conflict between Muhammad and the Jews as something of minor importance in Muhammad's career.

Status of Jews under Muslim rule

Traditionally Jews living in Muslim lands, known (along with Christians) as dhimmis, were allowed to practice their religion and to administer their internal affairs but subject to certain conditions. They had to pay the jizyaJizya

Under Islamic law, jizya or jizyah is a per capita tax levied on a section of an Islamic state's non-Muslim citizens, who meet certain criteria...

(a per capita tax imposed on free adult non-Muslim males) to Muslims. Dhimmis had an inferior status under Islamic rule. They had several social and legal disabilities

Disabilities (Jewish)

Disabilities were legal restrictions and limitations placed on Jews in the Middle Ages. They included provisions requiring Jews to wear specific and identifying clothing such as the Jewish hat and the yellow badge, restricting Jews to certain cities and towns or in certain parts of towns , and...

such as prohibitions against bearing arms or giving testimony in courts in cases involving Muslims. Many of the disabilities were highly symbolic. The most degrading one was the requirement of distinctive clothing

Yellow badge

The yellow badge , also referred to as a Jewish badge, was a cloth patch that Jews were ordered to sew on their outer garments in order to mark them as Jews in public. It is intended to be a badge of shame associated with antisemitism...

, not found in the Qur'an or hadith but invented in early medieval

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages was the period of European history lasting from the 5th century to approximately 1000. The Early Middle Ages followed the decline of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the High Middle Ages...

Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

; its enforcement was highly erratic. Jews rarely faced martyrdom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and they were mostly free in their choice of residence and profession.

The notable examples of massacre of Jews include the 1066 Granada massacre

1066 Granada massacre

The 1066 Granada massacre took place on 30 December 1066 when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada, which was at that time in Muslim-ruled al-Andalus, assassinated the Jewish vizier Joseph ibn Naghrela and massacred many of the Jewish population of the city.-Joseph ibn Naghrela:Joseph...

, when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada

Granada

Granada is a city and the capital of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of three rivers, the Beiro, the Darro and the Genil. It sits at an elevation of 738 metres above sea...

, crucified

Crucifixion

Crucifixion is an ancient method of painful execution in which the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross and left to hang until dead...

Jewish vizier

Vizier

A vizier or in Arabic script ; ; sometimes spelled vazir, vizir, vasir, wazir, vesir, or vezir) is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in a Muslim government....

Joseph ibn Naghrela and massacred most of the Jewish population of the city. "More than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day." This was the first persecution of Jews on the Peninsula under Islamic rule. There was also the killing or forcibly conversion of them by the rulers of the Almohad

Almohad

The Almohad Dynasty , was a Moroccan Berber-Muslim dynasty founded in the 12th century that established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains in roughly 1120.The movement was started by Ibn Tumart in the Masmuda tribe, followed by Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi between 1130 and his...

dynasty in Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

in the 12th century. Notable examples of the cases where the choice of residence was taken away from them includes confining Jews to walled quarters (mellah

Mellah

A mellah is a walled Jewish quarter of a city in Morocco, an analogue of the European ghetto...

s) in Morocco beginning from the 15th century and especially since the early 19th century. Most conversions were voluntary and happened for various reasons. However, there were some forced conversions in the 12th century under the Almohad

Almohad

The Almohad Dynasty , was a Moroccan Berber-Muslim dynasty founded in the 12th century that established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains in roughly 1120.The movement was started by Ibn Tumart in the Masmuda tribe, followed by Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi between 1130 and his...

dynasty of North Africa and al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

as well as in Persia.

Pre-modern times

The portrayal of the Jews in the early Islamic texts played a key role in shaping the attitudes towards them in the Muslim societies. According to Jane GerberJane Gerber

Jane S. Gerber is a professor of Jewish history and the director of the Institute for Sephardic Studies at City University of New York. She is also the author of many books, including Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience, and other books. Gerber was formerly the president of the...

, "the Muslim is continually influenced by the theological threads of anti-Semitism embedded in the earliest chapters of Islamic history." In the light of the Jewish defeat at the hands of Muhammad, Muslims traditionally viewed Jews with contempt and as objects of ridicule. Jews were seen as hostile, cunning, and vindictive, but nevertheless weak and ineffectual. Cowardice was the quality most frequently attributed to Jews. Another stereotype associated with the Jews was their alleged propensity to trickery and deceit. While most anti-Jewish polemicists saw those qualities as inherently Jewish, Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldūn or Ibn Khaldoun was an Arab Tunisian historiographer and historian who is often viewed as one of the forerunners of modern historiography, sociology and economics...

attributed them to the mistreatment of Jews at the hands of the dominant nations. For that reason, says ibn Khaldun, Jews "are renowned, in every age and climate, for their wickedness and their slyness".

Some Muslim writers have inserted racial overtones in their anti-Jewish polemics. Al-Jahiz

Al-Jahiz

Al-Jāḥiẓ was an Arabic prose writer and author of works of literature, Mu'tazili theology, and politico-religious polemics.In biology, Al-Jahiz introduced the concept of food chains and also proposed a scheme of animal evolution that entailed...

speaks of the deterioration of the Jewish stock due to excessive inbreeding. Ibn Hazm

Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ) was an Andalusian philosopher, litterateur, psychologist, historian, jurist and theologian born in Córdoba, present-day Spain...

also implies racial qualities in his attacks on the Jews. However, these were exceptions, and the racial theme left little or no trace in the medieval Muslim anti-Jewish writings.

Anti-Jewish sentiments usually flared up at times of the Muslim political or military weakness or when Muslims felt that some Jews had overstepped the boundary of humiliation prescribed to them by the Islamic law. In Moorish Iberia

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their anti-Jewish writings on the latter allegation. This was also the chief motivation behind the 1066 Granada massacre

1066 Granada massacre

The 1066 Granada massacre took place on 30 December 1066 when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada, which was at that time in Muslim-ruled al-Andalus, assassinated the Jewish vizier Joseph ibn Naghrela and massacred many of the Jewish population of the city.-Joseph ibn Naghrela:Joseph...

, when "[m]ore than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day", and in Fez

Fes, Morocco

Fes or Fez is the second largest city of Morocco, after Casablanca, with a population of approximately 1 million . It is the capital of the Fès-Boulemane region....

in 1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465.

Islamic law does not differentiate between Jews and Christians in their status as dhimmis. According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, FBA is a British-American historian, scholar in Oriental studies, and political commentator. He is the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University...

, the normal practice of Muslim governments until modern times was consistent with this aspect of sharia

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

law. This view is countered by Jane Gerber, who maintains that of all dhimmis, Jews had the lowest status. Gerber maintains that this situation was especially pronounced in the latter centuries, when Christian communities enjoyed protection, unavailable to the Jews, under the provisions of Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and European powers, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or ahdnames, were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were entered into by each contracting party towards the other, not mere...

. For example, in 18th century Damascus

Damascus

Damascus , commonly known in Syria as Al Sham , and as the City of Jasmine , is the capital and the second largest city of Syria after Aleppo, both are part of the country's 14 governorates. In addition to being one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Damascus is a major...

, a Muslim noble held a festival, inviting to it all social classes in descending order, according to their social status: the Jews outranked only the peasants and prostitutes. In 1865, when the equality of all subjects of the Ottoman Empire was proclaimed, Ahmed Cevdet Pasha, a high-ranking official observed: "whereas in former times, in the Ottoman State, the communities were ranked, with the Muslims first, then the Greeks, then the Armenians, then the Jews, now all of them were put on the same level. Some Greeks objected to this, saying: 'The government has put us together with the Jews. We were content with the supremacy of Islam.'"

Some scholars have questioned the correctness of the term "antisemitism" to Muslim culture in pre-modern times. Robert Chazan and Alan Davies argue that the most obvious difference between pre-modern Islam and pre-modern Christendom was the "rich melange of racial, ethic, and religious communities" in Islamic countries, within which "the Jews were by no means obvious as lone dissenters, as they had been earlier in the world of polytheism or subsequently in most of medieval Christendom." According to Chazan and Davies, this lack of uniqueness ameliorated the circumstances of Jews in the medieval world of Islam. According to Norman Stillman

Norman Stillman

Norman Arthur Stillman, also Noam , b. 1945, is the Schusterman-Josey Professor and Chair of Judaic History at the University of Oklahoma. He specializes in the intersection of Jewish and Islamic culture and history, and in Oriental and Sephardi Jewry, with special interest in the Jewish...

, antisemitism, understood as hatred of Jews as Jews, "did exist in the medieval Arab world even in the period of greatest tolerance". Also see Bostom, Bat Ye'or, and the CSPI issued text, supporting Stillman and cited in the bibliography.

Nineteenth century

Historian Martin GilbertMartin Gilbert

Sir Martin John Gilbert, CBE, PC is a British historian and Fellow of Merton College, University of Oxford. He is the author of over eighty books, including works on the Holocaust and Jewish history...

writes that in the 19th century the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries.

There was a massacre of Jews in Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

in 1828 and in 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue, and destroyed the Torah scrolls

Sefer Torah

A Sefer Torah of Torah” or “Torah scroll”) is a handwritten copy of the Torah or Pentateuch, the holiest book within Judaism. It must meet extremely strict standards of production. The Torah scroll is mainly used in the ritual of Torah reading during Jewish services...

. It was only by forcible conversion that a massacre was averted. There was another massacre in Barfurush in 1867.

In 1840, the Jews of Damascus

History of the Jews in Syria

Syrian Jews derive their origin from two groups: those who inhabited Syria from early times and the Sephardim who fled to Syria after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain . There were large communities in Aleppo, Damascus, and Qamishli for centuries. In the early twentieth century a large...

were falsely accused of having murdered a Christian monk and his Muslim servant and of having used their blood

Blood libel

Blood libel is a false accusation or claim that religious minorities, usually Jews, murder children to use their blood in certain aspects of their religious rituals and holidays...

to bake Passover bread

Matzo

Matzo or matzah is an unleavened bread traditionally eaten by Jews during the week-long Passover holiday, when eating chametz—bread and other food which is made with leavened grain—is forbidden according to Jewish law. Currently, the most ubiquitous type of Matzo is the traditional Ashkenazic...

or Matza. A Jewish barber was tortured until he "confessed"; two other Jews who were arrested died under torture, while a third converted to Islam to save his life. Throughout the 1860s, the Jews of Libya

History of the Jews in Libya

The history of the Jews in Libya stretches back to the 3rd century BCE, when Cyrenaica was under Greek rule. During World War II, Libya's Jewish population was subjected to anti-Semitic laws by the Fascist Italian regime and deportations by German troops...

were subjected to what Gilbert calls punitive taxation. In 1864, around 500 Jews were killed in Marrakech

Marrakech

Marrakech or Marrakesh , known as the "Ochre city", is the most important former imperial city in Morocco's history...

and Fez

Fes, Morocco

Fes or Fez is the second largest city of Morocco, after Casablanca, with a population of approximately 1 million . It is the capital of the Fès-Boulemane region....

in Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

. In 1869, 18 Jews were killed in Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

, and an Arab mob looted Jewish homes and stores, and burned synagogues, on Jerba Island

Djerba

Djerba , also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is, at 514 km², the largest island of North Africa, located in the Gulf of Gabes, off the coast of Tunisia.-Description:...

. In 1875, 20 Jews were killed by a mob in Demnat, Morocco; elsewhere in Morocco, Jews were attacked and killed in the streets in broad daylight. In 1891, the leading Muslims in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

to prohibit the entry of Jews arriving from Russia. In 1897, synagogues were ransacked and Jews were murdered in Tripolitania

Tripolitania

Tripolitania or Tripolitana is a historic region and former province of Libya.Tripolitania was a separate Italian colony from 1927 to 1934...

.

Benny Morris

Benny Morris

Benny Morris is professor of History in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Be'er Sheva, Israel...

writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. Morris quotes a 19th century traveler: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine

Gaberdine

A gaberdine or gabardine is a long, loose gown or cloak with wide sleeves, worn by men in the later Middle Ages and into the 16th century....

. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."

According to Mark Cohen

Mark R. Cohen

Mark R. Cohen is a professor of Near Eastern studies at Princeton University specializing in Jews in the Muslim world. He is a leading scholar of the history of Jews in the Middle Ages under Islam. His research relies greatly on documents from the Cairo Geniza...

in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies, most scholars conclude that Arab antisemitism in the modern world arose in the 19th century, against the backdrop of conflicting Jewish and Arab nationalism, and was imported into the Arab world primarily by nationalistically minded Christian Arabs (and only subsequently was it "Islamized").

Modern Islamic antisemitism

There were NaziNazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

-inspired pogroms in Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

in the 1930s, and massive attacks on the Jews in Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

and Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

in the 1940s (see Farhud

Farhud

Farhud refers to the pogrom or "violent dispossession" carried out against the Jewish population of Baghdad, Iraq, on June 1-2, 1941 during the Jewish holiday of Shavuot. The riots occurred in a power vacuum following the collapse of the pro-Nazi government of Rashid Ali while the city was in a...

). Pro-Nazi Muslims slaughtered dozens of Jews in Baghdad in 1941. The massacres of Jews in Muslim countries continued into the 20th century. Martin Gilbert writes that 40 Jews were murdered in Taza

Taza

Taza is a city in northern Morocco, which occupies the corridor between the Rif mountians and Middle Atlas mountains, about 120 km east of Fez. It is located at 150 km from Nador, and 210 km from Oujda...

, Morocco in 1903. In 1905, old laws were revived in Yemen

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

forbidding Jews from raising their voices in front of Muslims, building their houses higher than Muslims, or engaging in any traditional Muslim trade or occupation. The Jewish quarter in Fez was almost destroyed by a Muslim mob in 1912.

Antagonism and violence increased still further as resentment against Zionist

Zionism

Zionism is a Jewish political movement that, in its broadest sense, has supported the self-determination of the Jewish people in a sovereign Jewish national homeland. Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Zionist movement continues primarily to advocate on behalf of the Jewish state...

efforts in the British Mandate of Palestine spread. Anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionistic views or opposition to the state of Israel. The term is used to describe various religious, moral and political points of view in opposition to these, but their diversity of motivation and expression is sufficiently different that "anti-Zionism" cannot be...

propaganda in the Middle East frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust

The Holocaust

The Holocaust , also known as the Shoah , was the genocide of approximately six million European Jews and millions of others during World War II, a programme of systematic state-sponsored murder by Nazi...

to demonize

Demonization

Demonization is the reinterpretation of polytheistic deities as evil, lying demons by other religions, generally monotheistic and henotheistic ones...

Israel and its leaders. At the same time, Holocaust denial

Holocaust denial

Holocaust denial is the act of denying the genocide of Jews in World War II, usually referred to as the Holocaust. The key claims of Holocaust denial are: the German Nazi government had no official policy or intention of exterminating Jews, Nazi authorities did not use extermination camps and gas...

and Holocaust minimization efforts have found increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries. Arabic- and Turkish-editions of Hitler'sMein Kampf

Mein Kampf