Nobel Prize controversies

Encyclopedia

Subsequent to his death in 1896, the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel

established the Nobel Prize

s. Annual prizes were to be awarded for service to humanity in the fields of physics

, chemistry

, physiology or medicine

, literature

, and peace

. Similarly, the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel is awarded along with the Nobel Prizes. Since the first award in 1901, the prizes have engendered criticism and controversy.

Nobel sought to reward "those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind". One prize, he stated, should be given "to the person who shall have made the most important 'discovery' or 'invention' within the field of physics". Awards committees have historically rewarded discoveries over inventions: 77% of Nobel Prizes in physics have been given to discoveries, compared with only 23% to inventions. In addition, the scientific prizes typically reward contributions over an entire career rather than a single year.

No Nobel Prize was established for mathematics

and many other scientific and cultural fields. An early theory that jealousy led Nobel to omit a prize to mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler was refuted because of timing inaccuracies. Another possibility is that Nobel did not consider mathematics as a "practical" discipline. Both the Fields Medal

and the Abel Prize

have been described as the "Nobel Prize of mathematics".

The most notorious controversies have been over prizes for Literature, Peace and Economics. Beyond disputes over which contributor's work was more worthy, critics most often discerned political bias and Eurocentrism

in the result. The interpretation of Nobel's original words concerning the Literature prize have been repeatedly revised.

, Martin Chalfie

and Roger Y. Tsien

for their work on green fluorescent protein

or GFP. However, Douglas Prasher

was the first to clone the GFP gene and suggested its use as a biological tracer. Martin Chalfie stated, "(Douglas Prasher's) work was critical and essential for the work we did in our lab. They could've easily given the prize to Douglas and the other two and left me out." Dr. Prasher's accomplishments were not recognized and he lost his job. When the Nobel was awarded in 2008, Dr. Prasher was working as a courtesy shuttle bus driver in Huntsville Alabama.

The 2000 prize "for the Discovery and Development of Conductive polymer

s" to Alan J. Heeger

,

Alan MacDiarmid

, and

Hideki Shirakawa

recognized the 1977 discovery of passive high-conductivity in oxidized iodine-doped polyacetylene

black and related materials, as well as determining conduction mechanisms and developing devices, especially batteries. The citation alleges that this work led to present-day "active" devices, where a voltage or current controls electron flow. However, three years before their discovery, an active organic polymer electronic device was reported in the journal Science. In the "ON" state it showed almost metallic conductivity. This device is now on the "Smithsonian chips" list of key discoveries in semiconductor technology. Moreover, 14 years earlier, Weiss and coworkers in Australia had reported equivalent high electrical conductivity in an almost identical compound—oxidized, iodine-doped polypyrrole

black. Eventually, the Australian group achieved resistances as low as 0.03 ohm/cm. This was roughly equivalent to the later efforts. Slightly later, DeSurville and coworkers reported high conductivity in a polyaniline

. This award also ignored the 1955 discovery of highly-conductive organic charge transfer complex

es. Some of these were superconductive. The Nobel Prize information page omitted these earlier discoveries and emphasized the importance of the Nobel laureates in launching the field.

The 1993 prize credited Kary Mullis

with the development of the polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) method, a central technique in molecular biology

which allowed for the amplification of specified DNA sequences. However, others claimed that Norwegian scientist Kjell Kleppe, together with 1968 Nobel Prize laureate H. Gobind Khorana, had an earlier and better claim to the discovery dating from 1969. Mullis' co-workers at that time denied that he was solely responsible for the idea of using Taq polymerase

in the PCR process. Rabinow raised the issue of whether or not Mullis "invented" PCR or "merely" came up with the concept of it. However, Khudyakov and Howard Fields claimed "the full potential [of PCR] was not realized" until Mullis' work in 1983.

The 1961 prize for carbon assimilation in plants awarded to Melvin Calvin

was controversial because it ignored the contributions of Andrew Benson

and James Bassham

. While originally named the Calvin cycle

, many biologists and botanists now refer to the Calvin-Benson, Benson-Calvin, or Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle. Three decades after winning the Nobel, Calvin published an autobiography titled "Following the trail of light" about his scientific journey which didn't mention Benson.

Fritz Haber

's 1918 prize for developing an industrial process of producing ammonia

was controversial because of his leadership of Germany's World War I chemical warfare program

.

Henry Eyring

(1901–1981) allegedly failed to receive the prize because of his Mormon faith.

Dmitri Mendeleyev, who originated the periodic table

of the elements

, never received a Nobel Prize. He completed his first periodic table in 1869. However, a year earlier, another chemist, Julius Lothar Meyer

, had reported a somewhat similar table. In 1866 John Alexander Reina Newlands

, presented a paper that first proposed a periodic law. However, none of these tables were correct—the 19th century tables arranged the elements in order of increasing atomic weight (or atomic mass

). It was left to Henry Moseley

to base the periodic table on the atomic number

(the number of protons). Mendeleyev died in 1907, six years after the first Nobel Prizes were awarded. He came within one vote of winning in 1906, but died the next year. Hargittai claimed that Mendeleyev's omission was due to behind-the-scenes machinations of one dissenter on the Nobel Committee who disagreed with his work.

had garnered nine Prizes—far more than any other university. This led to claims of bias against alternative or heterodox

economics.

The 2008 prize went to Paul Krugman

"for his analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity". Krugman was a fierce critic of George W. Bush

. The award produced charges of a left-wing bias, with headlines such as "Bush critic wins 2008 Nobel for economics", prompting the prize committee to deny "the committee has ever taken a political stance."

The 2005 prize to Robert Aumann

"for having enhanced our understanding of conflict and cooperation through game-theory

analysis", was criticized by the European press due to his alleged use of game theory to oppose the dismantling of Israeli settlements in the West Bank

.

The 1994 prize to John Forbes Nash

and others "for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games

" caused controversy within the selection committee because of Nash' mental illness

and alleged anti-Semitism

. The controversy resulted in a change to the governing committee: members served three year instead of unlimited terms and the prize's scope expanded to include political science, psychology, and sociology.

The 1976 prize was awarded to Milton Friedman

"for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilisation policy". The award caused international protests, mostly by the radical left, ostensibly because of Friedman's brief association with Chile

an dictator Augusto Pinochet

. During March 1975 Friedman visited Chile and gave lectures on inflation, meeting with Pinochet and other government officials.

, Ezra Pound

, James Joyce

, Vladimir Nabokov

, Virginia Woolf

, Jorge Luis Borges

, Gertrude Stein

, August Strindberg

, John Updike

, Arthur Miller

, Yannis Ritsos, often for political or extra-literary reasons. Conversely, many writers whom subsequent criticism regarded as minor, inconsequential or transitional won the prize.

From 1901 to 1912, the committee's work reflected an interpretation of the "ideal direction" stated in Nobel's will as "a lofty and sound idealism", which caused Leo Tolstoy

, Henrik Ibsen

, Émile Zola

and Mark Twain

to be rejected. Sweden's historic antipathy towards Russia was cited as the reason neither Tolstoy

nor Anton Chekhov

took the prize. During World War I and its immediate aftermath, the committee adopted a policy of neutrality, favoring writers from non-combatant countries.

The heavy focus on European authors, and Swedes in particular, has been the subject of mounting criticism, including from major Swedish newspapers. The majority of the laureates have been European. Swedes received more prizes than all of Asia. In 2008, Horace Engdahl

, then the permanent secretary of the Academy, declared that "Europe still is the center of the literary world" and that "the US is too isolated, too insular. They don't translate enough and don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature." In 2009, Engdahl's replacement, Peter Englund

, rejected this sentiment ("In most language areas ... there are authors that really deserve and could get the Nobel Prize and that goes for the United States and the Americas, as well,") and acknowledged the Eurocentric bias of the selections, saying that, "I think that is a problem. We tend to relate more easily to literature written in Europe and in the European tradition."

The 2009 prize awarded to Herta Müller

The 2009 prize awarded to Herta Müller

was attacked because many US literary critics and professors had never heard of Müller before. This reignited criticism that the committee was too Eurocentric.

The 2005 prize went to Harold Pinter

"who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression's closed rooms".. The award was delayed for some days, apparently due to Knut Ahnlund

's resignation. In turn, this renewed speculation about a "political element" existing in the Swedish Academy's awarding of the Prize. Although poor health prevented him from giving his controversial Nobel Lecture, "Art, Truth and Politics", in person, he appeared on video, which was simultaneously transmitted on Britain's Channel Four. The issue of "political stance" was also raised in response to Orhan Pamuk

and Doris Lessing

, prizewinners in 2006 and 2007, respectively.

The 2004 prize was awarded to Elfriede Jelinek

. Inactive since 1996 Academy member Knut Ahnlund resigned, alleging that selecting Jelinek had caused "irreparable damage" to the prize's reputation.

The 1997 prize went to Italian performance artist Dario Fo

and was initially considered "rather lightweight" by some critics, as he was seen primarily as a performer and had previously been censured by the Roman Catholic Church

. Salman Rushdie and Arthur Miller

had been favored to receive the Prize, but a committee member was later quoted as saying that they would have been "too predictable, too popular."

The 1974 prize was denied to Graham Greene

, Vladimir Nabokov

, and Saul Bellow

in favor of a joint award for Swedish authors Eyvind Johnson

and Harry Martinson

—both Nobel judges—and unknown outside their home country. Bellow won in 1976; neither Greene nor Nabokov took home the prize.

The 1970 prize was awarded to Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

, who did not attend the ceremony in Stockholm for fear that the Soviet Union

would prevent his return. His works there are available only in Samizdat

-published, clandestine form. After the Swedish government refused to hold a public award ceremony and lecture at its Moscow embassy, Solzhenitsyn refused the award altogether, commenting that the conditions set by the Swedes (who preferred a private ceremony) were "an insult to the Nobel Prize itself." Solzhenitsyn later accepted the award on 10 December 1974, after the Soviet Union banished him.

Czech writer Karel Čapek

's "War With the Newts" was considered too offensive to the German government, and he declined to suggest a non-controversial publication that could be cited in its stead ("Thank you for the good will, but I have already written my doctoral dissertation"). He never received a prize.

French novelist and intellectual André Malraux

was considered for the Literature prize in the 1950s, according to Swedish Academy

archives studied by newspaper Le Monde

on their opening in 2008. Malraux was competing with Albert Camus

, but was rejected several times, especially in 1954 and 1955, "so long as he does not come back to novel", while Camus won the prize in 1957.

W. H. Auden

's missing prize was attributed to errors in his translation of 1961 Peace Prize

winner Dag Hammarskjöld

's Vägmärken (Markings) and to statements that Auden made during a Scandinavian lecture tour suggesting that Hammarskjöld was, like Auden, homosexual.

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges

was nominated several times but never won. Edwin Williamson, Borges's biographer, stated that the author's support of Argentine and Chilean right-wing military dictators. Borges' failure to win the Nobel Prize contrasts with awards to writers who openly supported left-wing dictatorships, including Joseph Stalin

, in the case of Jean Paul Sartre and Pablo Neruda

.

The academy's refusal to express support for Salman Rushdie in 1989, after Ayatollah

Ruhollah Khomeini

issued a fatwā

on his life led two Academy members to resign.

The 2010 prize

went to Liu Xiaobo

"for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China". Liu was imprisoned at the time of the award and neither he nor his family were allowed to attend the ceremony. The Chinese government alleged that Liu did not promote "international friendship, disarmament, and peace meetings", the prize's stated goal. Further, Liu Xiabo participated in organizations that received funding from the American National Endowment for Democracy

, which claim brings his status, and in fact the Nobel Peace Prize, into question. Chinese groups also criticized Liu's selection due to his low profile and obscurity within China and among Chinese youth. In the west, Tariq Ali

, Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong critized Liu's selection due to his long support of American invasions of other nations, particularly Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan and Iraq. Liu's selection was also criticized due to his support of the George W Bush administration in the United States and the Ariel Sharon

government in Israel and his ideological alignment with the neoconservative movement. The Chinese government responded by creating a rival award—the Confucius Peace Prize

.

The 2009 prize

was awarded to Barack Obama

"for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples". The award, given in the first year of Obama's presidency, received criticism that it was undeserved, premature and politically motivated. Obama himself said that he felt "surprised" by the win and did not consider himself worthy of the award, but nonetheless accepted it. Obama's peace prize was called a "stunning surprise" by The New York Times

. Much of the surprise arose from the fact that nominations for the award had been due by 1 February 2009, only 12 days after Obama took office. In an October 2011 interview. Thorbjørn Jagland

, chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, defended the award on narrow grounds:

The 2007 prize went to Al Gore

and the IPCC

, "for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change". The award received criticism on the grounds of political motivation and because the winners' work was not directly related to ending conflict. Al Gore's victory over prize candidate Irena Sendler

, a Polish social worker known as the "female Oskar Schindler

" for her efforts to save Jewish children during the Holocaust

, attracted criticism from the humanitarian agency International Federation of Social Workers

(IFSW).

The 2004 prize went to Wangari Maathai

"for her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace". Controversially, she was reported by the Kenya

n newspaper Standard

and Radio Free Europe

to have stated that HIV/AIDS was originally developed by Western scientists in order to depopulate Africa. She later denied these claims, although the Standard stood by its reporting. Additionally, in a Time magazine interview, she hinted at HIV's non-natural origin, saying that someone knows where it came from and that it "...did not come from monkeys."

The 2002 prize was awarded to Jimmy Carter

for "decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development." The announcement of the award came shortly after the US House and Senate authorized President George W. Bush

to use military force against Iraq

in order to enforce UN Security Council resolutions requiring that Baghdad

give up weapons of mass destruction

. Asked if the selection of the former president was a criticism of Bush, Gunnar Berge

, head of the Nobel Prize committee, said: "With the position Carter has taken on this, it can and must also be seen as criticism of the line the current US administration has taken on Iraq." Carter declined to comment on the remark in interviews, saying that he preferred to focus on the work of the Carter Center

.

The 1994 prize went to Yasser Arafat

, Shimon Peres

, and Yitzhak Rabin

"to honour a political act which called for great courage on both sides, and which has opened up opportunities for a new development towards fraternity in the Middle East.". Arafat's critics have referred to him as an "unrepentant terrorist with a long legacy of promoting violence". Kåre Kristiansen

, a Norwegian member of the Nobel Committee, resigned in protest at Arafat's award, calling him a "terrorist". Supporters of Arafat claimed fairness, citing Nelson Mandela

, who had never renounced political violence, and had been a founder member of Umkhonto we Sizwe

. On the other hand, Edward Said

was critical of Peres and Rabin and the entire Oslo Accords

.

The 1992 prize was awarded to Rigoberta Menchú

for "her work for social justice and ethno-cultural reconciliation based on respect for the rights of indigenous peoples". The prize-winner's memoirs, which had brought her to fame, turned out to be partly fictitious.

The 1989 prize was awarded to the 14th Dalai Lama

. This was not well-accepted by the Chinese government, which cited his separatist tendencies. Additionally, the Nobel Prize Committee cited their intention to put pressure on China.

The 1978 prize went to Anwar Sadat

, president of Egypt during the 1973 Yom Kippur War

against Israel, and Menachem Begin

"for the Camp David Agreement

, which brought about a negotiated peace between Egypt and Israel". Both had fought against British rule of their respective countries, and Begin was involved in a failed plot to assassinate German chancellor Konrad Adenauer

.

The 1973 prize went to North Vietnamese leader Le Duc Tho

and United States Secretary of State

Henry A. Kissinger "for the 1973 Paris Peace Accords

intended to bring about a cease-fire in the Vietnam War

and a withdrawal of the American forces". Tho later declined the prize. North Vietnam invaded South Vietnam

in April 1975 and reunified the country. Kissinger's history included the secret 1969–1975 bombing campaign against North Vietnamese Army troops infiltrating the South via Cambodia

, the alleged U.S. involvement in Operation Condor

—a mid-1970s campaign of kidnapping and murder coordinated among the intelligence and security services of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile (see details), Paraguay, and Uruguay—as well as the death of French nationals under the Chilean junta. He also supported the Turkish Intervention in Cyprus resulting in the de facto partition of the island. According to Irwin Abrams

, this prize was the most controversial to date. Two Norwegian Nobel Committee members resigned in protest. When the award was announced, hostilities were continuing.

The 1945 prize was awarded to Cordell Hull

as "Former Secretary of State; Prominent participant in the originating of the UN". Hull was Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Secretary of State

during the SS St. Louis

Crisis. The St. Louis sailed from Hamburg

in the summer of 1939 carrying over 950 Jewish refugees

, seeking asylum from Nazi persecution. Initially, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt showed some willingness to take in some of those on board, but Hull and Southern Democrats voiced vehement opposition, and some of them threatened to withhold their support of Roosevelt in the 1940 election. On 4 June 1939 Roosevelt denied entry to the ship, which was waiting in the Caribbean Sea between Florida and Cuba. The passengers began negotiations with the Cuban government, but those broke down. Forced to return to Europe, over a quarter of its passengers subsequently died in the Holocaust.

Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize, although he was nominated five times between 1937 and 1948. A decades-later Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission. Geir Lundestad, Secretary of Norwegian Nobel Committee in 2006 said, "The greatest omission in our 106 year history is undoubtedly that Mahatma Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace prize. Gandhi could do without the Nobel Peace prize, whether Nobel committee can do without Gandhi is the question". The Nobel Committee of the time may have tacitly acknowledged its error, however, when in 1948 (the year of his death), it made no award, stating "there was no suitable living candidate". A later committee awarded the prize posthumously to Scandinavian Dag Hammarskjöld

in 1961, who died after being nominated.

The progress in the search for the Higgs boson

The progress in the search for the Higgs boson

led to a dispute on who should get credit for the discovery and the resulting Physics Prize. Six people, across three different teams, were credited with the most significant contributions to this work: Robert Brout

and François Englert

of the Université Libre de Bruxelles

; Peter Higgs

of University of Edinburgh

; and G. S. Guralnik at Brown University

, C. R. Hagen

of the University of Rochester

, and Tom Kibble at Imperial College London

. Three papers written in 1964 explained what is now known as the "Englert-Brout-Higgs-Guralnik-Hagen-Kibble mechanism" (or Higgs mechanism

and Higgs boson

for short). The mechanism was the key element of the electroweak theory that formed part of the Standard model

of particle physics

. The papers that introduced this mechanism were published in Physical Review Letters

in 1964 and were each recognized as milestones during PRL’s 50th anniversary celebration. All six won The American Physical Society's

J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics

for "elucidation of the properties of spontaneous symmetry breaking

in four-dimensional relativistic gauge theory

and of the mechanism for the consistent generation of vector boson

masses"

The 2009 prize was awarded to Willard Boyle

and George E. Smith

for developing the CCD

. However, Eugene I. Gordon

and Michael Francis Tompsett

claimed that it should have been theirs for figuring out that the technology could be used for imaging.

Half of the 2008 prize was awarded to Makoto Kobayashi

and Toshihide Maskawa

for their 1972 work on quark

mixing. This postulated the existence of three additional quarks beyond the three then known to exist and used this postulate to provide a possible mechanism for CP violation

, which had been observed 8 years earlier. Their work expanded and reinterpreted research by Nicola Cabibbo

, dating to 1963, before the quark model was even introduced. The resulting quark mixing matrix, which described probabilities of different quarks to turn into each other under the action of the weak force, is known as CKM matrix, after Cabibbo, Kobayashi, and Maskawa. Cabibbo arguably merited a share of the award. Possibly, the Committee wanted to recognize Yoichiro Nambu

, the other recipient of the 2008 prize, who was 87 at the time. Since the prize is awarded to at most three people, the committee was forced to choose only two of the CKM researchers.

The 2006 prize was won by John C. Mather

and George F. Smoot (leaders of the COsmic Background Explorer (COBE

) satellite experiment) for "the blackbody form and anisotropy

of the cosmic microwave background radiation

(CMBR)." However, in July 1983 an experiment launched aboard the Prognoz-9 satellite, studied CMBR via a single frequency. In January 1992, Andrei A. Brukhanov presented a seminar at Sternberg Astronomical Institute

in Moscow, where he first reported on the discovery. However, the Relikt team claimed only an upper limit, not a detection, in their 1987 paper.

Half of the 2005 prize was awarded to Roy J. Glauber

"for his contribution to the quantum theory of optical coherence". This research involved George Sudarshan

's relevant 1960 work in quantum optics

, which was allegedly slighted in this award. Glauber—who initially derided the former representations, later produced the same P-representation

under a different name, viz., Sudarshan-Glauber representation or Sudarshan diagonal representation—was the winner instead. According to others, the deserving Leonard Mandel

and Daniel Frank Walls

were passed over because posthumous nominations were not accepted.

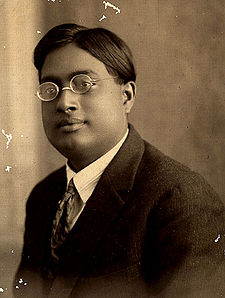

The 2001 prize went to Eric Allin Cornell

The 2001 prize went to Eric Allin Cornell

, Carl Edwin Wieman and Wolfgang Ketterle

"for the achievement of Bose-Einstein condensation in dilute gases of alkali atoms, and for early fundamental studies of the properties of the condensates". However, the original work by Indian mathematician and physicist Satyendra Nath Bose

and Albert Einstein regarding the gas-like qualities of electromagnetic radiation and quantum mechanics in the early 1920s provided the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics

and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate

was never awarded the prize.

The 1997 prize was awarded to Steven Chu

, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji

and William Daniel Phillips

"for development of methods to cool and trap atoms with laser light." The award was disputed by Russian scientists who questioned the awardees' priority in the acquired approach and techniques, which the Russians claimed to have carried out more than a decade before.

The 1983 prize went to William Alfred Fowler

"for his theoretical and experimental studies of the nuclear reactions of importance in the formation of the chemical elements in the universe". Fowler acknowledged Fred Hoyle

as the pioneer of the concept of stellar nucleosynthesis

but that was not enough for Hoyle to receive a share. Hoyle's obituary in Physics Today

notes that "Many of us felt that Hoyle should have shared Fowler's 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics, but the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences later made partial amends by awarding Hoyle, with Edwin Salpeter, its 1997 Crafoord Prize

".

The 1979 prize was awarded to Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam

and Steven Weinberg

for the electroweak interaction unification theory. However, George Sudarshan

and Robert Marshak

were the first proponents of the successful V-A (vector minus axial vector, or left-handed) theory for weak interactions in 1957. It was essentially the same theory as that proposed by Richard Feynman

and Murray Gell-Mann

in their "mathematical physics" paper on the structure of the weak interaction

. Actually, Gell-Mann had been let in on the Sudarshan/Marshak work on Sudarshan's initiative, but no acknowledgment appeared in the later paper—except for an informal allusion. The reason given was that the originators' work had not been published in a formal or 'reputable enough' science journal at the time. The theory is popularly known in the west as the Feynman-Gell-Mann theory. The V-A theory for weak interactions was, in effect, a new Law of Nature. It was conceived in the face of a series of apparently contradictory experimental results, including several from Chien-Shiung Wu

, helped along by a sprinkling of other evidence, such as the muon

. Discovered in 1936, the muon had a colorful history itself and would lead to a new revolution in the 21st Century. This breakthrough was not awarded a Nobel Prize. The V-A theory would later form the foundation for the electroweak interaction

theory. Sudarshan regarded the V-A theory as his finest work. The Sudarshan-Marshak (or V-A theory) was assessed, preferably and favorably, as "beautiful" by J. Robert Oppenheimer, only to be disparaged later on as "less complete" and "inelegant" by John Gribbin

.

The 1978 prize was awarded for the chanced "detection of Cosmic microwave background radiation

". The joint winners, Arno Allan Penzias

and Robert Woodrow Wilson

, had their discovery elucidated by others. Many scientists felt that Ralph Alpher, who predicted the cosmic microwave background radiation and in 1948 worked out the underpinnings of the Big Bang theory, should have shared in the prize or received one independently. In 2005, Alpher received the National Medal of Science

for his pioneering contributions to understanding of nucleosynthesis

, the prediction of the relic radiation from the Big Bang, as well as for a model for the Big Bang.

The 1974 prize was awarded to Martin Ryle

and Antony Hewish

"for their pioneering research in radio astrophysics: Ryle for his observations and inventions, in particular of the aperture synthesis

technique, and Hewish for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsar

s". Hewish was not the first to correctly explain pulsars, initially describing them as communications from "Little Green Men" (LGM-1

) in outer space. David Staelin and Edward Reifenstein, of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia, found a pulsar at the center of the Crab Nebula

. The notion that pulsars were neutron star

s, leftovers from a supernova

explosion, had been proposed in 1933. Soon after their 1968 discovery, Fred Hoyle

and astronomer Thomas Gold

correctly explained it as a rapidly spinning neutron star with a strong magnetic field, emitting radio waves. Jocelyn Bell Burnell

, Hewish's graduate student, was not recognized, although she was the first to notice the stellar radio source that was later recognized as a pulsar. While Hoyle argued that Bell should have been included in the prize, Bell said, "I believe it would demean Nobel Prizes if they were awarded to research students, except in very exceptional cases, and I do not believe this is one of them." Prize-winning research students include Louis de Broglie, Rudolf Mössbauer, Douglas Osheroff, Gerard 't Hooft, John Forbes Nash

, Jr., John Robert Schrieffer

and H. David Politzer.

The 1969 prize was won by Murray Gell-Mann

"for his contributions and discoveries concerning the classification of elementary particles and their interactions" (essentially, discovering quark

s). George Zweig

, then a PhD student at Caltech, independently espoused the physical existence of aces, essentially the same thing. The physics community ostracized Zweig and blocked his career. Israeli physicist Yuval Ne'eman

published the classification of hadron

s through their SU(3) flavor symmetry

independently of Gell-Mann in 1962, and also felt that he had been unjustly deprived of the prize for the quark model

.

The 1956 prize went to John Bardeen

, Walter Houser Brattain

and William Bradford Shockley "for their researches on semiconductors and their discovery of the transistor effect". However, the committee did not recognize numerous preceding ]patent applications. As early as 1928, Julius Edgar Lilienfeld

patented several modern transistor

types. In 1934, Oskar Heil

patented a field-effect transistor

. It is unclear whether Lilienfeld or Heil had built such devices, but they did cause later workers significant patent problems. Further, Herbert F. Mataré and Heinrich Walker, at Westinghouse

Paris, applied for a patent in 1948 of an amplifier

based on the minority carrier injection process. Mataré had first observed transconductance effects during the manufacture of germanium

diodes for German radar equipment during World War II. Shockley was part of other controversies—including his position as a corporate director and his self-promotion efforts. Further, the original design Shockley presented to Brattain and Bardeen did not work. His share of the prize resulted from his development of the superior junction transistor

, which became the basis of the electronics revolution. He excluded Brattain and Bardeen from the proceeds of this process, even though the idea may have been theirs. Another controversy associated with Shockley was his support of eugenics

. He regarded his published works on this topic as the most important work of his career.

The 1950 prize went to Cecil Powell for "his development of the photographic method of studying nuclear processes and his discoveries regarding meson

s made with this method". However, Brazil

ian physicist César Lattes

was the main researcher and the first author of the historical Nature

journal article describing the subatomic particle

meson

pi (pion

). Lattes was solely responsible for the improvement of the nuclear emulsion used by Powell (by asking Kodak Co. to add more boron

to it—and in 1947, he made with them his great experimental discovery). This result was explained by the Nobel Committee policy (ended in 1960) to award the prize to the research group head only. Lattes calculated the pion's mass and, with USA physicist Eugene Gardner, demonstrated the existence of this particle after atomic collisions in a synchrotron

. Gardner was denied a prize because he died soon thereafter.

The 1938 prize went to Enrico Fermi

in part for "his demonstrations of the existence of new radioactive elements produced by neutron irradiation". However, in this case, the award later appeared to be premature: Fermi thought he had created transuranic elements (specifically, hesperium

), but had in fact unwittingly demonstrated nuclear fission

(and had actually created only fission products—isotopes of much lighter elements than uranium). The fact that Fermi's interpretation was incorrect was discovered shortly after he had received his prize.

The 1936 prize went to Carl D. Anderson for the discovery of the positron. While a graduate student at Caltech in 1930, Chung-Yao Chao

was the first to experimentally identify positron

s through electron-positron annihilation

, but did not realize what they were. Anderson used the same radioactive source, , as Chao. (Historically, was known as "thorium C double prime" or "ThC", see decay chains.) Late in life, Anderson admitted that Chao had inspired his discovery: Chao's research formed the foundation from which much of Anderson's own work developed. Chao died in 1998, without sharing in a Nobel Prize acknowledgment.

The 1923 prize went to Robert Millikan

"for his work on the elementary charge of electricity and on the photoelectric effect

". Millikan might have won in 1920 but for Felix Ehrenhaft

's incorrect claim to have measured a smaller charge. Some controversy, however, still seems to linger over Millikan's oil-drop procedure and experimental interpretation, over whether Millikan manipulated his data in the 1913 scientific paper measuring the electron charge. Allegedly, he did not report all his observations.

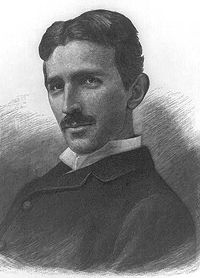

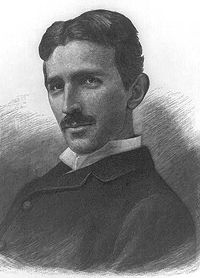

The 1915 prize went to William Henry Bragg

and William Lawrence Bragg

"For their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays", an important step in the development of X-ray crystallography

. At the time, both Thomas Edison

and Nikola Tesla

were mentioned as potential laureates. Despite their enormous scientific contributions, neither ever won the award, possibly because of their mutual animosity. Circumstantial evidence hints that each sought to minimize the other's achievements and right to win the award, that both refused to ever accept the award if the other received it first, and that both rejected any possibility of sharing it—as was rumored in the press. Tesla had a greater financial need for the award than Edison: in 1916, he filed for bankruptcy.

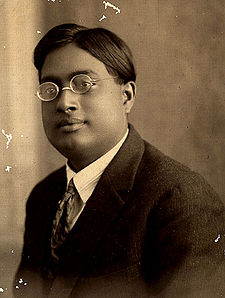

The 1909 prize was awarded to Guglielmo Marconi

for the invention of radio. However, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office first awarded the patent on radio to Tesla, but changed its decision in Marconi's favor in 1904. In 1942, the patent office reversed itself in Tesla's favor. In 1893, Tesla demonstrated the first public radio

communication. One year later, Indian physicist, Jagadish Chandra Bose, demonstrated publicly the use of radio waves in Calcutta. In 1894, Bose ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance using electromagnetic waves, showing independently that signals could be sent without using wires. In 1896, the Daily Chronicle of England reported on his UHF experiments: "The inventor (J.C. Bose) has transmitted signals to a distance of nearly a mile and herein lies the first and obvious and exceedingly valuable application of this new theoretical marvel." Bose did not seek patent protection for sending signals. In 1899, Bose announced the development of an "iron-mercury-iron coherer with telephone detector" in a paper presented at the Royal Society in London. Later he received U.S. Patent 755,840, "Detector for electrical disturbances" (1904), for a specific electromagnetic receiver.

The 1903 prize was awarded to Henri Becquerel

(along with Pierre

and Marie Curie

) "in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by his discovery of spontaneous radioactivity". However, critics alleged that Becquerel merely rediscovered a phenomenon first noticed and investigated decades earlier by the French scientist Abel Niepce de Saint-Victor

.

won the prize. Lise Meitner

contributed directly to the discovery of nuclear fission in 1939, Her work preceded that of Otto Hahn

. Working with the then-available experimental data, she managed, with Otto Robert Frisch

's participation, to incorporate Niels Bohr

's liquid drop model (first suggested by George Gamow

) into fission's theoretical foundation. She also predicted the possibility of chain reaction

s. In an earlier collaboration with Hahn, she had independently discovered a new chemical element (called protactinium

). Bohr nominated both for this work, in addition to recommending the Chemistry prize for Hahn. A junior contributor, Fritz Strassmann

, was not considered for the prize. The Nazis successfully pressured Hahn to minimize Meitner's role, since she was Jewish. However, he maintained this position even after the war.

Chien-Shiung Wu

disproved the law of the conservation of parity

(1956) and was the first Wolf Prize winner in physics. She died in 1997 without receiving a Nobel. Wu assisted Tsung-Dao Lee

personally in his parity laws development—with Chen Ning Yang—by providing him in 1956 with a possible test method for beta decay that worked successfully.Her book Beta Decay (1965) is still a sine qua non

reference for nuclear physicists.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

's 1921 Nobel Prize Award mainly recognized his 1905 discovery of the mechanism of the photoelectric effect

and "for his services to Theoretical Physics". The Nobel committee passed on several nominations for his many other seminal contributions, although these led to prizes for others who later applied more advanced technology to experimentally verify his work. Many predictions of Einstein's theories have been verified as technology advances. Recent examples include the bending of light in a gravitational field

, gravitational wave

s, gravitational lensing and black holes. It wasn't until 1993 that the first evidence for the existence of gravitational radiation came via the Nobel Prize-winning measurements of the Hulse-Taylor binary system.

The committee also failed to recognize the other contributions of his Annus Mirabilis Papers

on Brownian motion

and Special Relativity

. Often these nominations for Special Relativity were for both Hendrik Lorentz

and Einstein. Henri Poincaré

was also nominated at least once for his work, including on Lorentz's relativity theory. However, Kaufmann's then-experimental results (incorrectly) cast doubt on Special Relativity. These doubts were not resolved until 1915. By this time, Einstein had progressed to his General Theory of Relativity, including his theory of gravitation. Empirical support—in this case the predicted spectral shift of sunlight—was in question for many decades. The only piece of original evidence was the consistency with the known perihelion precession of the planet Mercury. Some additional support was gained at the end of 1919, when the predicted deflection of starlight near the sun was confirmed by Arthur Stanley Eddington

's Solar Eclipse Expedition, though here again the actual results were somewhat ambiguous. (A TV movie was made in 2008 about this.)

Conclusive proof of the gravitational light deflection prediction was not achieved until the 1970s.

days before the award, a fact unknown to the Nobel committee at the time of the award. Committee rules prohibit posthumous awards, and Steinman's death created a dilemma unprecedented in the history of the award. The committee ruled that Steinman remained eligible for the award despite his death, under the rule that allows awardees to receive the award who die between being named and the awards ceremony.

The 2008 prize was awarded in part to Harald zur Hausen

"for his discovery of human papilloma viruses (HPV) causing cervical cancer

". The Swedish police anticorruption unit investigated charges of improper influence by AstraZeneca

, which had a stake in two lucrative HPV vaccine

s. The company had agreed to sponsor Nobel Media and Nobel Web and had strong links with two senior figures in the process that chose zur Hausen.

The other half of the 2008 prize was split between Luc Montagnier

and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi

"for their discovery of human immunodeficiency virus". The omission of Robert Gallo

was controversial: 106 scientists signed a letter to the journal Science stating that 'While these awardees fully deserve the award, it is equally important to recognize the contributions of Robert C. Gallo', which 'warrant equal recognition'. Montagnier said that he was 'surprised' that the award had not been shared with Gallo.

The 2006 prize went to Andrew Fire

and Craig C. Mello "for their discovery of RNA interference

—gene silencing by double-stranded RNA

". Many of the discoveries credited by the committee to Fire and Mello, who studied RNA interference in C. elegans

, had been previously studied by plant biologists, and was suggested that at least one plant biologist, such as David Baulcombe

, should have been awarded a share of the prize.

The 2003 prize was awarded to Paul Lauterbur

and Sir Peter Mansfield

"for their discoveries concerning magnetic resonance imaging

" (MRI). Two independent alternatives have been alleged. Raymond Damadian first reported that NMR

could distinguish in vitro between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues on the basis of different proton relaxation times. He later translated this into the first human scan. Damadian's original report prompted Lauterbur to develop NMR into the present method. Damadian took out large advertisements in an international newspapers protesting his exclusion. Some researchers felt that Damadian's work deserved at least equal credit.Separately, Herman Y. Carr both pioneered the NMR gradient technique and demonstrated rudimentary MRI imaging in the 1950s. The Nobel prize winners had almost certainly seen Carr's work, but did not cite it. Consequently, the prize committee very likely was unaware of Carr's discoveries, a situation likely abetted by Damadian's campaign.

The 2000 prize went to Arvid Carlsson

, Paul Greengard

, and Eric R. Kandel

, "for their discoveries concerning signal transduction in the nervous system". The award caused many neuroscientists to protest that Oleh Hornykiewicz

, who helped pioneer the dopamine replacement treatment for Parkinson's disease, was left out, and that Hornykiewicz's research provided a foundation for the honorees' success.

The 1997 prize was awarded to Dr. Stanley B. Prusiner

for his discovery of prions. This award caused a long stream of polemics. Critics attacked the validity of the work, which had been criticized by other researchers as not yet proven.

The 1993 prize went to Philip Allen Sharp and Richard J. Roberts

"for their discoveries of split genes" the discovery of introns in eukaryotic DNA

and the mechanism of gene splicing. Several other scientists, such as Norman Davidson and James D. Watson

, argued that Louise T. Chow, a China-born Taiwanese researcher who collaborated with Roberts, should have had part of the prize. In 1976, as Staff Investigator, Chow carried out the studies of the genomic origins and structures of adenovirus transcripts that led directly to the discovery of RNA splicing and alternative RNA processing at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

on Long Island

in 1977. Norman Davidson, (a Caltech expert in electron microscopy, under whom Chow apprenticed as a graduate student), affirmed that Chow operated the electron microscope

through which the splicing process was observed, and was the crucial experiment's sole designer, using techniques she had developed.

The 1975 prize was awarded to David Baltimore

, Renato Dulbecco

and Howard Martin Temin

"for their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumor viruses and the genetic material of the cell". It has been argued that Dulbecco was distantly, if at all, involved in this ground-breaking work. Further, the award failed to recognize the contributions of Satoshi Mizutani, Temin's Japanese postdoctoral fellow. Mizutani and Temin jointly discovered that the Rous sarcoma virus

particle contained the enzyme

reverse transcriptase

. However, Mizutani was solely responsible for the original conception and design of the novel experiment that confirmed Temin's provirus

hypothesis. A second controversy implicated Baltimore in the "Imanishi-Kari" affair, involving charges that Thereza Imanishi-Kari

, a researcher in his laboratory, had fabricated data. Imanishi-Kari was initially found to have committed scientific fraud by the Office of Scientific Integrity (OSI), following highly publicized and politicized hearings. However, in 1996, she was vindicated by an appeals panel of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which overturned the OSI's findings and criticized their investigation. Baltimore's staunch defense of Imanishi-Kari initially drew substantial criticism and controversy; the case itself was often referred to as "The Baltimore Affair", and contributed to his resignation as president of Rockefeller University

. Following Imanishi-Kari's vindication, Baltimore's role was reassessed; the New York Times opined that "... the most notorious fraud case in recent scientific history has collapsed in embarrassment for the Federal Government and belated vindication for the accused scientist."

The 1973 prize went to Konrad Lorenz

, Nikolaas Tinbergen

and Karl von Frisch

"for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns". Von Frisch's contribution was the "dance language" of bees. However, controversy emerged over the lack of direct proof of the waggle dance

—as exactly worded by von Frisch. A team of researchers from Rothamsted Research in 2005 settled the controversy by using radar to track bees as they flew to a food source. Their results did not exactly match von Frisch's original formulation, ending up closer to his opponent Adrian Wenner's theory that the bees used the odor of the food returned by the dancer.

The 1968 prize went to Robert W. Holley

, Har Gobind Khorana and Marshall W. Nirenberg "for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis". However, Heinrich J. Matthaei

broke the genetic code

in 1961 with Nirenberg in their poly-U experiment at National Institutes of Health

(NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, paving the way for modern genetics

. Matthaei was responsible for experimentally obtaining the first codon (nucleotide

triple that usually specifies an amino acid

) extract, while Nirenberg tampered with his initial, accurate results (due to his belief in 'less precise', 'more believable' data presentation).

The 1962 prize was awarded to James D. Watson

, Francis Crick

and Maurice Wilkins

"for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material". It did not recognize critical contributions from Alec Stokes

, Herbert Wilson

, and Erwin Chargaff

. In addition, Erwin Chargaff

, Oswald Avery

and Rosalind Franklin

(whose key DNA

X-ray crystallography

work was the most detailed yet least acknowledged among the three) contributed directly to Watson and Crick's ability to solve the DNA molecule's structure. Avery's death in 1955, and Franklin's in 1958, eliminated them from contention.

The 1952 prize was awarded solely to Selman Waksman

"for his discovery of streptomycin

, the first antibiotic

effective against tuberculosis

" and omitted recognition due his co-discoverer Albert Schatz

. Schatz sued Waksman over the details and credit of the discovery. Schatz was awarded a substantial settlement, and, together with Waksman, Schatz was legally recognized as a co-discoverer.

The 1949 prize was awarded to Portuguese neurologist Antonio Egas Moniz "for his discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy (lobotomy) in certain psychoses". Soon after, Dr. Walter Freeman developed the transorbital lobotomy, which was easier to carry out. Criticism was raised because the procedure was often prescribed injudiciously and without regard for medical ethics

. Popular acceptance of the procedure had been fostered by enthusiastic press coverage such as a 1938 "New York Times" report. Endorsed by such influential publications as The New England Journal of Medicine, in the three years following the Prize, some 5,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States alone, and many more throughout the world.Joseph Kennedy, father of U.S. President John F. Kennedy

, had his daughter Rosemary

lobotomized when she was in her twenties. The procedure later fell into disrepute and was prohibited in many countries.

The 1945 prize was awarded to Ernst Boris Chain

, Howard Florey and Alexander Fleming

"for the discovery of penicillin

and its curative effect in various infectious disease

s". Fleming accidentally stumbled upon the then-unidentified fungal

mold

. However, some critics pointed out that Fleming did not in fact discover penicillin, that it was technically a rediscovery; decades before Fleming, Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson

, William Roberts (physician)

, John Tyndall

and Ernest Duchesne

) had already done studies and research on its useful properties and medicinal characteristics. Moreover, according to Fleming himself, the first known reference to penicillin was from Psalm 51

: "Purge me with hyssop

and I shall be clean". Meanwhile, he had learned from mycologist Charles Thom (the same who helped Fleming establish the identity of the mysterious fungal mold) that "Penicillium notatum" was first recognized by Westling, a Swedish chemist, from a specimen of decayed hyssop. In this award, as it had been pointed out, several deserving contemporaneous contributors had been left out of the Prize altogether

.

The 1926 prize went to Johannes Andreas Grib Fibiger

, "for his discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma

", a microbial parasite which Fibiger claimed was the cause of cancer. This "finding" was discredited by other scientists shortly thereafter.

The 1923 prize was awarded to Frederick Banting

and John Macleod "for the discovery of insulin

". Banting clearly deserved the prize, however, the choice of Macleod as co-winner was controversial. Banting initially refused to accept the prize with Macleod, claiming that he did not deserve it, and that Charles Best was the proper corecipient. Banting complained that Macleod's initial contribution to the project had only been to let Banting use his lab space at the University of Toronto

while Macleod was on vacation. Macleod also loaned Banting a lab assistant (Best) to help with the experiments, and ten dogs for experimentation. Banting and Best achieved limited success with their experiments, which they presented to Macleod in the fall of 1921. Macleod pointed out design flaws in some experiments. He then advised Banting and Best to repeat the experiments with better lab equipment, more dogs, and better controls and provided better lab space. He also began paying Banting. The salary made their relationship official, and equivalent to the present-day relationship between a postdoctoral researcher

and supervisor. Banting and Best repeated the experiments, which were conclusive. While Banting's original method of isolating insulin worked, it was too labor-intensive for large-scale production. Best then set about finding a biochemical extraction method. Meanwhile, James Bertram Collip, a chemistry professor on sabbatical from the University of Alberta

joined what was now Macleod's team, and sought a biochemical method for extracting insulin in parallel with Best. Best and Collip simultaneously succeeded. The fact that Banting was being supported with money from Macleod's research grants was no doubt a factor in the Nobel Committee's decision. When Banting agreed to share the prize, he gave half his prize money to Best. Macleod, in turn, split his half of the prize money with Collip. Later, it became known that Nicolae Paulescu

, a Romanian professor, had been working on diabetes since 1916, and may have isolated insulin (which he called pancreatine) about a year before the Canadians.

Oswald Theodore Avery, best known for his 1944 demonstration

that DNA

is the cause of bacterial transformation and potentially the material of which genes

are composed, never received a Nobel Prize, although two Nobel Laureates, Joshua Lederberg

and Arne Tiselius

, praised him and his work as a pioneering platform for further genetic research. According to John M. Barry

, in his book The Great Influenza, the committee was preparing to award Avery, but declined to do so after the DNA findings were published, fearing that they would be endorsing findings that had not yet survived significant scrutiny.

when it awarded the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize to Carl von Ossietzky

, a German writer who publicly opposed Hitler and Nazism

. (At that time, the prize was awarded the following year.) Hitler reacted by issuing a decree on 31 January 1937 that forbade German nationals to accept any Nobel Prize. Awarding the peace prize to Ossietzky was itself considered controversial. While Fascism

had few supporters outside Italy and Germany, those who did not necessarily sympathize felt that it was wrong to (deliberately) offend Germany.

Hitler's decree prevented three Germans from accepting their prizes: Gerhard Domagk

(1939 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine), Richard Kuhn

(1938 Nobel Prize in Chemistry), and Adolf Butenandt

(1939 Nobel Prize in Chemistry). The three later received their certificates and medals, but not the prize money.

On 19 October 1939, about a month and a half after World War II

had started, the Nobel Committee of the Karolinska Institutet

met to discuss the 1939 prize in physiology or medicine. The majority favored Domagk and someone leaked the news, which traveled to Berlin. The Kulturministerium in Berlin replied with a telegram stating that a Nobel Prize to a German was "completely unwanted" (durchaus unerwünscht). Despite the telegram, a large majority voted for on 26 October 1939. Once he learned of the decision, hopeful that it only applied to the peace prize, Domagk sent a request to the Ministry of Education in Berlin asking permission to accept the prize. Since he did not receive a reply after more than a week had passed, he felt it would be impolite to wait any longer without responding, and on 3 November 1939 he wrote a letter to the Institute thanking them for the distinction, but added that he had to wait for the government's approval before he could accept the prize. He was subsequently ordered to send a copy of his letter to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Berlin, and on 17 November 1939, was arrested by the Gestapo

. He was released after one week, then arrested again. On 28 November 1939, he was forced by the Kulturministerium to sign a prepared letter, addressed to the Institute, declining the prize. Since the Institute had already prepared his medal and diploma before the second letter arrived, they were able to award them to him later, during the 1947 Nobel festival. Domagk was the first to decline a prize. Due to his refusal, the procedures changed so that if a laureate declined the prize or failed to collect the prize award before 1 October of the following year, the money would not be awarded.

On 9 November 1939, the Royal Academy of Sciences awarded the 1938 Prize for Chemistry to Kuhn and half of the 1939 prize to Butenandt. When notified of the decision, the German scientists were forced to decline by threats of violence. Their refusal letters arrived in Stockholm after Domagk's refusal letter, helping to confirm suspicions that the German government had forced them to refuse the prize. In 1948, they wrote to the Academy expressing their gratitude for the prizes and their regret for being forced to refuse them in 1939. They were awarded their medals and diplomas at a ceremony in July 1949.

Otto Heinrich Warburg

, a German national who won the 1931 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, was rumored to have been selected for the 1944 prize, but was forbidden to accept it. According to the Nobel Foundation, this story is not true.

Boris Pasternak

at first accepted the 1958 Nobel Prize in Literature, but was forced by Soviet authorities to decline, because the prize was considered a "reward for the dissident political innuendo in his novel, Doctor Zhivago

." Pasternak died without ever receiving the prize. He was eventually honored by the Nobel Foundation at a banquet in Stockholm on 9 December 1989, when they presented his medal to his son.

declined 1964 prize for Literature, stating, "A writer must refuse to allow himself to be transformed into an institution, even if it takes place in the most honourable form." The second person who refused the prize is Lê Đức Thọ

, who was awarded the 1973 Peace Prize for his role in the Paris Peace Accords

. He declined, claiming there was no actual peace in Vietnam.

, philosophy and social studies

-were not included among the Nobel Prizes, because they were not part of Alfred Nobel's will. When Jakob von Uexkull

approached the Nobel Foundation with a proposal to establish two new awards for the environment and for the lives of the poor, he was turned down. He then established the Right Livelihood Award

.

In 2003 purportedly a new Nobel-equivalent Award was also created especially for mathematics, the Abel Prize

, though the older Fields Medal

is often considered as the mathematical Nobel equivalent.

However, the Nobel Committee did allow the creation of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. Many people have opposed this expansion, including the Swedish human rights lawyer Peter Nobel, a great-grandnephew of Alfred Nobel. In his speech at the 1974 Nobel banquet, awardee Friedrich Hayek

stated that had he been consulted whether to establish an economics prize, he would "have decidedly advised against it" primarily because "the Nobel Prize confers on an individual an authority which in economics no man ought to possess... This does not matter in the natural sciences. Here the influence exercised by an individual is chiefly an influence on his fellow experts; and they will soon cut him down to size if he exceeds his competence. But the influence of the economist that mainly matters is an influence over laymen: politicians, journalists, civil servants and the public generally."

to incarcerated Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese tabloid Global Times

created the Confucius Peace Prize. The award ceremony was deliberately organized to take place on 8 December, one day before the Nobel ceremony. Organizers said that the prize had no relation to the Chinese government, the Ministry of Culture or Beijing Normal University.

The German National Prize for Art and Science

was Hitler's alternative to the Nobel Prize.

The Ig Nobel Prize

is an American parody of the Nobel Prize.

Alfred Nobel

Alfred Bernhard Nobel was a Swedish chemist, engineer, innovator, and armaments manufacturer. He is the inventor of dynamite. Nobel also owned Bofors, which he had redirected from its previous role as primarily an iron and steel producer to a major manufacturer of cannon and other armaments...

established the Nobel Prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

s. Annual prizes were to be awarded for service to humanity in the fields of physics

Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895 and awarded since 1901; the others are the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Peace Prize, and...

, chemistry

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

, physiology or medicine

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine administered by the Nobel Foundation, is awarded once a year for outstanding discoveries in the field of life science and medicine. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, in his will...

, literature

Nobel Prize in Literature

Since 1901, the Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded annually to an author from any country who has, in the words from the will of Alfred Nobel, produced "in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction"...

, and peace

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

. Similarly, the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel is awarded along with the Nobel Prizes. Since the first award in 1901, the prizes have engendered criticism and controversy.

Nobel sought to reward "those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind". One prize, he stated, should be given "to the person who shall have made the most important 'discovery' or 'invention' within the field of physics". Awards committees have historically rewarded discoveries over inventions: 77% of Nobel Prizes in physics have been given to discoveries, compared with only 23% to inventions. In addition, the scientific prizes typically reward contributions over an entire career rather than a single year.

No Nobel Prize was established for mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

and many other scientific and cultural fields. An early theory that jealousy led Nobel to omit a prize to mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler was refuted because of timing inaccuracies. Another possibility is that Nobel did not consider mathematics as a "practical" discipline. Both the Fields Medal

Fields Medal

The Fields Medal, officially known as International Medal for Outstanding Discoveries in Mathematics, is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians not over 40 years of age at each International Congress of the International Mathematical Union , a meeting that takes place every four...

and the Abel Prize

Abel Prize

The Abel Prize is an international prize presented annually by the King of Norway to one or more outstanding mathematicians. The prize is named after Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel . It has often been described as the "mathematician's Nobel prize" and is among the most prestigious...

have been described as the "Nobel Prize of mathematics".

The most notorious controversies have been over prizes for Literature, Peace and Economics. Beyond disputes over which contributor's work was more worthy, critics most often discerned political bias and Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism is the practice of viewing the world from a European perspective and with an implied belief, either consciously or subconsciously, in the preeminence of European culture...

in the result. The interpretation of Nobel's original words concerning the Literature prize have been repeatedly revised.

Chemistry

The 2008 prize was awarded to Osamu ShimomuraOsamu Shimomura

is a Japanese organic chemist and marine biologist, and Professor Emeritus at Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts and Boston University Medical School...

, Martin Chalfie

Martin Chalfie

Martin Chalfie is an American scientist. He is the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Biological Sciences at Columbia University, where he is also chair of the department of biological sciences. He shared the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Osamu Shimomura and Roger Y. Tsien "for the...

and Roger Y. Tsien

Roger Y. Tsien

Roger Yonchien Tsien is a Chinese American biochemist and a professor at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego...

for their work on green fluorescent protein

Green fluorescent protein

The green fluorescent protein is a protein composed of 238 amino acid residues that exhibits bright green fluorescence when exposed to blue light. Although many other marine organisms have similar green fluorescent proteins, GFP traditionally refers to the protein first isolated from the...

or GFP. However, Douglas Prasher

Douglas Prasher

Douglas C. Prasher is an American molecular biologist. He is known for his work to clone and sequence the gene for green fluorescent protein and for his proposal to use GFP as a tracer molecule.-Career:...

was the first to clone the GFP gene and suggested its use as a biological tracer. Martin Chalfie stated, "(Douglas Prasher's) work was critical and essential for the work we did in our lab. They could've easily given the prize to Douglas and the other two and left me out." Dr. Prasher's accomplishments were not recognized and he lost his job. When the Nobel was awarded in 2008, Dr. Prasher was working as a courtesy shuttle bus driver in Huntsville Alabama.

The 2000 prize "for the Discovery and Development of Conductive polymer

Conductive polymer

Conductive polymers or, more precisely, intrinsically conducting polymers are organic polymers that conduct electricity. Such compounds may have metallic conductivity or can be semiconductors. The biggest advantage of conductive polymers is their processability, mainly by dispersion. Conductive...

s" to Alan J. Heeger

Alan J. Heeger

Alan Jay Heeger is an American physicist, academic and Nobel Prize laureate in chemistry.Heeger was born in Sioux City, Iowa to a Jewish family. He earned a B.S. in physics and mathematics from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1957, and a Ph.D in physics from the University of California,...

,

Alan MacDiarmid

Alan MacDiarmid

Alan Graham MacDiarmid ONZ was a chemist, and one of three recipients of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2000.-Early life:He was born in Masterton, New Zealand as one of five children - three brothers and two sisters...

, and

Hideki Shirakawa

Hideki Shirakawa

Hideki Shirakawa is a Japanese chemist and winner of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of conductive polymers together with physics professor Alan J. Heeger and chemistry professor Alan G...

recognized the 1977 discovery of passive high-conductivity in oxidized iodine-doped polyacetylene

Polyacetylene

Polyacetylene is an organic polymer with the repeat unit n. The high electrical conductivity discovered for these polymers beginning in the 1960's accelerated interest in the use of organic compounds in microelectronics...

black and related materials, as well as determining conduction mechanisms and developing devices, especially batteries. The citation alleges that this work led to present-day "active" devices, where a voltage or current controls electron flow. However, three years before their discovery, an active organic polymer electronic device was reported in the journal Science. In the "ON" state it showed almost metallic conductivity. This device is now on the "Smithsonian chips" list of key discoveries in semiconductor technology. Moreover, 14 years earlier, Weiss and coworkers in Australia had reported equivalent high electrical conductivity in an almost identical compound—oxidized, iodine-doped polypyrrole

Polypyrrole

Polypyrrole is a chemical compound formed from a number of connected pyrrole ring structures. For example a tetrapyrrole is a compound with four pyrrole rings connected. Methine-bridged cyclic tetrapyrroles are called porphyrins. Polypyrroles are conducting polymers of the rigid-rod polymer host...

black. Eventually, the Australian group achieved resistances as low as 0.03 ohm/cm. This was roughly equivalent to the later efforts. Slightly later, DeSurville and coworkers reported high conductivity in a polyaniline

Polyaniline

Polyaniline is a conducting polymer of the semi-flexible rod polymer family. Although the compound itself was discovered over 150 years ago, only since the early 1980s has polyaniline captured the intense attention of the scientific community. This is due to the rediscovery of its high electrical...

. This award also ignored the 1955 discovery of highly-conductive organic charge transfer complex

Charge transfer complex

A charge-transfer complex or electron-donor-acceptor complex is an association of two or more molecules, or of different parts of one very large molecule, in which a fraction of electronic charge is transferred between the molecular entities. The resulting electrostatic attraction provides a...

es. Some of these were superconductive. The Nobel Prize information page omitted these earlier discoveries and emphasized the importance of the Nobel laureates in launching the field.

The 1993 prize credited Kary Mullis

Kary Mullis

Kary Banks Mullis is a Nobel Prize winning American biochemist, author, and lecturer. In recognition of his improvement of the polymerase chain reaction technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and earned the Japan Prize in the same year. The process was first...

with the development of the polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction is a scientific technique in molecular biology to amplify a single or a few copies of a piece of DNA across several orders of magnitude, generating thousands to millions of copies of a particular DNA sequence....

(PCR) method, a central technique in molecular biology

Molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that deals with the molecular basis of biological activity. This field overlaps with other areas of biology and chemistry, particularly genetics and biochemistry...

which allowed for the amplification of specified DNA sequences. However, others claimed that Norwegian scientist Kjell Kleppe, together with 1968 Nobel Prize laureate H. Gobind Khorana, had an earlier and better claim to the discovery dating from 1969. Mullis' co-workers at that time denied that he was solely responsible for the idea of using Taq polymerase

Taq polymerase

thumb|228px|right|Structure of Taq DNA polymerase bound to a DNA octamerTaq polymerase is a thermostable DNA polymerase named after the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus from which it was originally isolated by Thomas D. Brock in 1965...

in the PCR process. Rabinow raised the issue of whether or not Mullis "invented" PCR or "merely" came up with the concept of it. However, Khudyakov and Howard Fields claimed "the full potential [of PCR] was not realized" until Mullis' work in 1983.

The 1961 prize for carbon assimilation in plants awarded to Melvin Calvin

Melvin Calvin

Melvin Ellis Calvin was an American chemist most famed for discovering the Calvin cycle along with Andrew Benson and James Bassham, for which he was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He spent most of his five-decade career at the University of California, Berkeley.- Life :Calvin was born...

was controversial because it ignored the contributions of Andrew Benson

Andrew Benson

Andrew Alm Benson is an American biologist and a professor of biology at the University of California, San Diego until his retirement in 1989...

and James Bassham

James Bassham

James Alan Bassham James Alan Bassham James Alan Bassham (born November 26, 1922 in Sacramento, California is an American scientist known for his work on photosynthesis.He received a B.S. degree in chemistry in 1945 from the University of California and his Ph.D. degree in 1949...

. While originally named the Calvin cycle

Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle or Calvin–Benson-Bassham cycle or reductive pentose phosphate cycle or C3 cycle or CBB cycle is a series of biochemical redox reactions that take place in the stroma of chloroplasts in photosynthetic organisms...

, many biologists and botanists now refer to the Calvin-Benson, Benson-Calvin, or Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle. Three decades after winning the Nobel, Calvin published an autobiography titled "Following the trail of light" about his scientific journey which didn't mention Benson.

Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber was a German chemist, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his development for synthesizing ammonia, important for fertilizers and explosives. Haber, along with Max Born, proposed the Born–Haber cycle as a method for evaluating the lattice energy of an ionic solid...

's 1918 prize for developing an industrial process of producing ammonia

Haber process

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the nitrogen fixation reaction of nitrogen gas and hydrogen gas, over an enriched iron or ruthenium catalyst, which is used to industrially produce ammonia....

was controversial because of his leadership of Germany's World War I chemical warfare program

Poison gas in World War I

The use of chemical weapons in World War I ranged from disabling chemicals, such as tear gas and the severe mustard gas, to lethal agents like phosgene and chlorine. This chemical warfare was a major component of the first global war and first total war of the 20th century. The killing capacity of...

.

Henry Eyring

Henry Eyring

Henry Eyring was a Mexican-born American theoretical chemist whose primary contribution was in the study of chemical reaction rates and intermediates....

(1901–1981) allegedly failed to receive the prize because of his Mormon faith.