Anti-Semitism

Encyclopedia

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination

against Jews

for reasons connected to their Jewish

heritage. According to a 2005 U.S. governmental report, antisemitism is "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity." In an extreme form, it "attributes to the Jews an exceptional position among all other civilizations, defames them as an inferior group and denies their being part of the nation[s]" in which they reside. A person who holds such views is called an "antisemite".

Antisemitism may be manifested in many ways, ranging from expressions of hatred of or discrimination

against individual Jews to organized violent attacks by mobs, or even state police, or military attacks on entire Jewish communities. Extreme instances of persecution

include the pogroms which preceded the First Crusade in 1096, the expulsion from England

in 1290, the massacres of Spanish Jews in 1391, the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition

, the expulsion from Spain

in 1492, the expulsion from Portugal in 1497, various Russian pogroms, the Dreyfus Affair

, and the Final Solution

by Hitler's Germany

and official Soviet

anti-Jewish policies.

While the term's etymology

might suggest that antisemitism is directed against all Semitic peoples, the term was coined in the late 19th century in Germany as a more scientific-sounding term for Judenhass ("Jew-hatred"),

and that has been its normal use since then.

s, Ethiopians, or Assyrians

) and that not all Jews speak a Semitic language.

The term anti-Semitic has been used on occasion to include bigotry against other Semitic-language peoples such as Arabs, but such usage is not widely accepted.

Both terms anti-Semitism and antisemitism are in common use. Some scholars favor the unhyphenated form antisemitism to avoid possible confusion involving whether the term refers specifically to Jews, or to Semitic

-language speakers as a whole. For example, Emil Fackenheim

supported the unhyphenated spelling, in order to "dispel[] the notion that there is an entity 'Semitism' which 'anti-Semitism' opposes."

Although Wilhelm Marr

Although Wilhelm Marr

is generally credited with coining the word anti-Semitism (see below), Alex Bein

writes that the word was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider

in the phrase "anti-Semitic prejudices". Steinschneider used this phrase to characterize Ernest Renan

's ideas about how "Semitic

races" were inferior to "Aryan

races." These pseudo-scientific

theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussia

n nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke

did much to promote this form of racism. He coined the term "the Jews are our misfortune" which would later be widely used by Nazis. In Treitschke's writings Semitic was synonymous with Jewish, in contrast to its use by Renan and others.

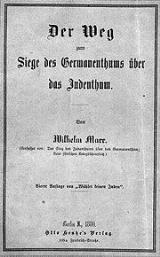

In 1873 German journalist Wilhelm Marr

published a pamphlet "The Victory of the Jewish Spirit over the Germanic Spirit. Observed from a non-religious perspective." ("Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum. Vom nicht confessionellen Standpunkt aus betrachtet.") in which he used the word "Semitismus" interchangeably with the word "Judentum" to denote both "Jewry" (the Jews as a collective) and "jewishness" (the quality of being Jewish, or the Jewish spirit). Although he did not use the word "Antisemitismus" in the pamphlet, the coining of the latter word followed naturally from the word "Semitismus", and indicated either opposition to the Jews as a people, or else opposition to Jewishness or the Jewish spirit, which he saw as infiltrating German culture. In his next pamphlet, "The Way to Victory of the Germanic Spirit over the Jewish Spirit", published in 1880, Marr developed his ideas further and coined the related German word Antisemitismus – antisemitism, derived from the word "Semitismus" that he had earlier used.

The pamphlet became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Antisemites" ("Antisemiten-Liga"), the first German organization committed specifically to combatting the alleged threat to Germany and German culture posed by the Jews and their influence, and advocating their forced removal

from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published "Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte," and Wilhelm Scherer

used the term "Antisemiten" in the January issue of "Neue Freie Presse". The related word semitism

was coined around 1885.

professor Helen Fein

defines it as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions – social or legal discrimination, political mobilization against the Jews, and collective or state violence – which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews." Elaborating on Fein's definition, Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne

writes that, to antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the antisemites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."

Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis

defines antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism.

There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. The U.S. Department of State defines antisemitism in its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism as "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (now Fundamental Rights Agency), then an agency of the European Union

, developed a more detailed working definition, which states: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." It adds "such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity." It provides contemporary examples of antisemitism, which include: promoting the harming of Jews in the name of an ideology or religion; promoting negative stereotypes of Jews; holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of an individual Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust

or accusing Jews or Israel of exaggerating it; and accusing Jews of dual loyalty

or a greater allegiance to Israel than their own country. It also lists ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor, or applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, or holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel.

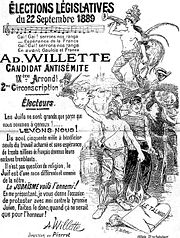

founded the Antisemiten-Liga (Antisemitic League). Identification with antisemitism and as an antisemite was politically advantageous in Europe in the latter 19th century. For example, Karl Lueger

, the popular mayor of fin de siècle

Vienna

, skillfully exploited antisemitism as a way of channeling public discontent to his political advantage. In its 1910 obituary of Lueger, The New York Times notes that Lueger was "Chairman of the Christian Social Union of the Parliament and of the Anti-Semitic Union of the Diet of Lower Austria. In 1895 A. C. Cuza

organized the Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle in Bucharest. In the period before World War II

, when animosity towards Jews was far more commonplace, it was not uncommon for a person, organization, or political party to self-identify as an antisemite or antisemitic.

The early Zionist pioneer, Judah Leib Pinsker, in a pamphlet written in 1882, said that antisemitism was an inherited predisposition:

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht

, Goebbels announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."

After Hitler's fall from power, and particularly after the extent of the Nazi genocide

of Jews became known, the term "antisemitism" acquired pejorative

connotations. This marked a full circle shift in usage, from an era just decades earlier when "Jew" was used as a pejorative term. Yehuda Bauer wrote in 1984: "There are no antisemites in the world... Nobody says, 'I am antisemitic.'" You cannot, after Hitler. The word has gone out of fashion."

It is often emphasized that there are different forms of antisemitism. René König mentions social antisemitism, economic antisemitism, religious antisemitism, and political antisemitism as examples. König points out that these different forms demonstrate that the "origins of antisemitic prejudices are rooted in different historical periods." König asserts that differences in the chronology of different antisemitic prejudices and the irregular distribution of such prejudices over different segments of the population create "serious difficulties in the definition of the different kinds of antisemitism." These difficulties may contribute to the existence of different taxonomies that have been developed to categorize the forms of antisemitism. The forms identified are substantially the same; it is primarily the number of forms and their definitions that differ. Bernard Lazare identifies three forms of antisemitism: Christian antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and ethnologic antisemitism.

It is often emphasized that there are different forms of antisemitism. René König mentions social antisemitism, economic antisemitism, religious antisemitism, and political antisemitism as examples. König points out that these different forms demonstrate that the "origins of antisemitic prejudices are rooted in different historical periods." König asserts that differences in the chronology of different antisemitic prejudices and the irregular distribution of such prejudices over different segments of the population create "serious difficulties in the definition of the different kinds of antisemitism." These difficulties may contribute to the existence of different taxonomies that have been developed to categorize the forms of antisemitism. The forms identified are substantially the same; it is primarily the number of forms and their definitions that differ. Bernard Lazare identifies three forms of antisemitism: Christian antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and ethnologic antisemitism.

William Brustein names four categories: religious, racial, economic and political. The Roman Catholic historian Edward Flannery

distinguished four varieties of antisemitism:

Louis Harap provides a similar list that separates out "economic antisemitism" and merges "political" and "nationalistic" antisemitism into what Harap terms as "ideological antisemitism". Harap also adds a category of "social antisemitism".

An important feature of cultural antisemitism is that it considers the negative attributes of Judaism to be redeemable by education or religious conversion.

to the official or right religion, and sometimes, liturgical exclusion of Jewish converts (the case of Christianized Marranos or Iberian Jews in the late 15th century and 16th century convicted of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs).

Although the origins of antisemitism are rooted in the religious conflict between Christianity and Judaism, religious antisemitism has largely been supplanted in the modern era by other forms of antisemitism. Frederick Schweitzer asserts that, "most scholars ignore the Christian foundation on which the modern antisemitic edifice rests and invoke political antisemitism, cultural antisemitism, racism or racial antisemitism, economic antisemitism and the like." William Nichols draws a distinction between religious antisemitism and modern antisemitism which is based on racial or ethnic grounds. Nichols writes, "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion . . . a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." From the perspective of racial antisemitism, however, "... the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism ... . From the Enlightenment onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews... Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

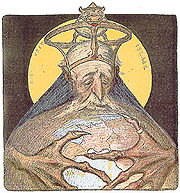

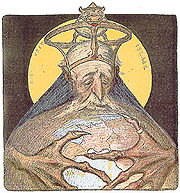

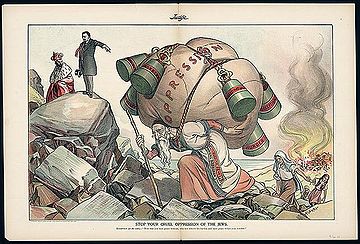

Allegations regarding the relationship of Jews and money have been characterized as underpinning the most damaging and lasting antisemitic canards. Antisemites have often promulgated myths related to money, such as the canard

that Jews control the world finances, first promoted in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and later repeated by Henry Ford

and his Dearborn Independent. In the modern era, many such myths continue to be widespread in books such as The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews

published by the Nation of Islam

, and on the internet.

Derek Penslar

writes that there are two components to the financial canards:

Abraham Foxman

describes six facets of the financial canards:

Gerald Krefetz summarizes the myth as "[Jews] control the banks, the money supply, the economy, and businesses – of the community, of the country, of the world". Krefetz gives, as illustrations, many slurs and proverbs (in several different languages) which suggest that Jews are stingy, or greedy, or miserly, or aggressive bargainers. Krefetz suggests that during the nineteenth century, most of the myths focused on Jews being "scurrilous, stupid, and tight-fisted", but following the Jewish Emancipation

and the rise of Jews to the middle- or upper-class in Europe the myths evolved and began to assert that Jews were "clever, devious, and manipulative financiers out to dominate [world finances]".

Leon Poliakov

asserts that economic antisemitism is not a distinct form of antisemitism, but merely a manifestation of theologic antisemitism (because, without the theological causes of the economic antisemitism, there would be no economic antisemitism). In opposition to this view, Derek Penslar contends that in the modern era, the economic antisemitism is "distinct and nearly constant" but theological antisemitism is "often subdued".

.jpg) Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism

as a religion.

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics

movement, which categorized non-"Europeans" as inferior. It more specifically claimed that the "Nordic" Europeans were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their "alien" extra-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion. Anthropologists discussed whether the Jews possessed any Arabic-Armenoid

, African-Nubian or Asian-Turkic

ancestries.

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution

, following the emancipation of the Jews

, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism

, the rise of eugenics

, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion . . . a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism ... . From the Enlightenment

onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews... Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

In the early 19th century, a number of laws enabling emancipation of the Jews

were enacted in Western European countries. The old laws restricting them to ghetto

s, as well as the many laws that limited their property rights, rights of worship and occupation, were rescinded. Despite this, traditional discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism, encouraged by the work of racial theorists such as Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and particularly his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Race of 1853–5.Nationalist agendas based on ethnicity, known as ethnonationalism, usually excluded the Jews from the national community as an alien race. Allied to this were theories of Social Darwinism

, which stressed a putative conflict between higher and lower races of human beings. Such theories, usually posited by white Europeans, advocated the superiority of white Aryan

s to Semitic

Jews.

According to Viktor Karády, political antisemitism became widespread after the legal emancipation of the Jews and sought to reverse some of the consequences of that emancipation.

's millennial and messianic vision which culminated in the Holocaust is sometimes referred to as an "apocalyptic antisemitism".

and Jewish conspiracy theories are also considered a form of antisemitism.

, the right

, and radical Islam

, which tends to focus on opposition to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel, and argue that the language of anti-Zionism

and criticism of Israel are used to attack the Jews more broadly. In this view, the proponents of the new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism

are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and attribute this to antisemitism. It is asserted that the new antisemitism deploys traditional antisemitic motifs, including older motifs such as the "Blood Libel

".

Critics of the concept view it as trivializing the meaning of antisemitism, and as exploiting antisemitism in order to silence debate and deflect attention from legitimate criticism of the State of Israel, and, by associating anti-Zionism with antisemitism, misused to taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies.

Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

in the 3rd century BCE. Alexandria was home to the largest Jewish community in the world and the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible

, was produced there. Manetho

, an Egyptian priest and historian of that time, wrote scathingly of the Jews and his themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon

, Lysimachus

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

, and in Apion

and Tacitus

. Agatharchides of Cnidus ridiculed the practices of the Jews and the "absurdity of their Law

", making a mocking reference to how Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BCE because its inhabitants were observing the Shabbat

. One of the earliest anti-Jewish edict

s, promulgated by Antiochus Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees

in Judea

.

In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek

retelling of Ancient Egypt

ian prejudices". The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died. The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews being portrayed as misanthropes

. Tcherikover argues that the reason for hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the poleis

. Bohak has argued, however, that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, and that many Greeks showed animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.

Statements exhibiting prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan Greek

and Roman

writers. Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho

, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers

who had been taught by Moses

"not to adore the gods." The same themes appeared in the works of Chaeremon

, Lysimachus

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon

, and in Apion

and Tacitus

. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practices" of the Jews and of the "absurdity of their Law" and how Ptolemy Lagus

was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BC because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath

. Edward Flannery describes antisemitism in ancient times as essentially "cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia played out in political settings."

There are examples of Hellenistic rulers desecrating the Temple

and banning Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision

, Shabbat observance, study of Jewish religious books, etc. Examples may also be found in anti-Jewish riots in Alexandria

in the 3rd century BCE. Philo of Alexandria described an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died.

The Jewish diaspora on the Nile island Elephantine

, which was founded by mercenaries, experienced the destruction of its temple in 410 BCE.

Relationships between the Jewish people and the occupying Roman Empire

were at times antagonistic and resulted in several rebellions

. According to Suetonius

, the emperor Tiberius

expelled from Rome Jews who had gone to live there. The 18th century English historian Edward Gibbon

identified a more tolerant period in Roman-Jewish relations beginning in about 160 CE . However, when Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire, the state's attitude towards the Jews gradually worsened.

James Carroll asserted: "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire

. By that ratio, if other factors such as pogrom

s and conversion

s had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."

classified Jews (and Christians) as dhimmi

, and allowed them to practice their religion more freely than they could do in medieval Christian Europe

. Under Islamic rule

, there was a Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain that lasted until at least the 11th century, when several Muslim pogrom

s against Jews took place in the Iberian Peninsula

; those that occurred in Córdoba

in 1011 and in Granada in 1066

. Several decrees ordering the destruction of synagogue

s were also enacted in Egypt

, Syria

, Iraq

and Yemen

from the 11th century. Jews were also forced to convert to Islam or face death in some parts of Yemen, Morocco

and Baghdad

several times between the 12th and 18th centuries. The Almohads, who had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi

and Andalusian territories by 1147, were far more fundamentalist in outlook, and they treated the dhimmis harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians emigrated. Some, such as the family of Maimonides

, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands, while some others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms.

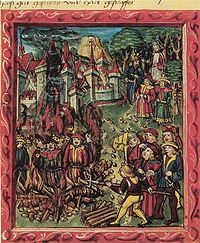

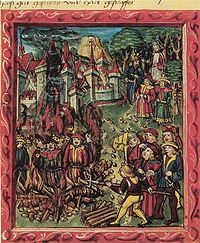

During the Middle Ages

in Europe there was persecution against Jews in many places, with blood libel

s, expulsions, forced conversion

s and massacre

s. A main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious. The persecution hit its first peak during the Crusades

. In the First Crusade

(1096) flourishing communities on the Rhine and the Danube

were destroyed

. In the Second Crusade

(1147) the Jews in Germany were subject to several massacres. The Jews were also subjected to attacks by the Shepherds' Crusade

s of 1251 and 1320. The Crusades were followed by expulsions, including, in 1290, the banishing of all English

Jews; in 1396, the expulsion of 100,000 Jews in France; and in 1421, the expulsion of thousands from Austria. Many of the expelled Jews fled to Poland. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, a major contributor to the deepening of antisemitic sentiment and legal action among the Christian populations was the popular preaching of the zealous reform religious orders, the Franciscans (especially Bernardino of Feltre) and Dominicans (especially Vincent Ferrer), who combed European promoting antisemitism through their often fiery, emotional appeals.

As the Black Death

epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than half of the population, Jews were used as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed. Although Pope Clement VI

tried to protect them by the July 6, 1348, papal bull

and an additional bull in 1348, several months later, 900 Jews were burned alive in Strasbourg

, where the plague had not yet affected the city.

was devastated by several conflicts, in which the Commonwealth lost over a third of its population (over 3 million people), and Jewish losses were counted in hundreds of thousands. First, the Chmielnicki Uprising when Bohdan Khmelnytsky

's Cossacks massacred tens of thousands of Jews in the eastern and southern areas he controlled (today's Ukraine

). The precise number of dead may never be known, but the decrease of the Jewish population during that period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, which also includes emigration, deaths from diseases and captivity in the Ottoman Empire

, called jasyr.

limited the number of Jews allowed to live in Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged a similar practice in other Prussia

n cities. In 1750 he issued the Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow

). In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa

ordered Jews out of Bohemia

but soon reversed her position, on the condition that Jews pay for their readmission every ten years. This extortion

was known as malke-geld (queen's money). In 1752 she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II

abolished most of these persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish

and Hebrew

were eliminated from public records and that judicial autonomy was annulled. Moses Mendelssohn

wrote that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than open persecution."

In 1772, the empress of Russia Catherine II forced the Jews of the Pale of Settlement

to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.

writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries. Benny Morris

writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. Morris quotes a 19th century traveler: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine

. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."

published Das Judenthum in der Musik

("Jewishness in Music") under a pseudonym

in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik

. The essay began as an attack on Jewish composers, particularly Wagner's contemporaries (and rivals) Felix Mendelssohn

and Giacomo Meyerbeer

, but expanded to accuse Jews of being a harmful and alien element in German culture

. Antisemitism can also be found in many of the Grimms' Fairy Tales by Jacob

and Wilhelm Grimm

, published from 1812 to 1857. It is mainly characterized by Jews being the villain

of a story, such as in "The Good Bargain (Der gute Handel)" and "The Jew Among Thorns (Der Jude im Dorn)."

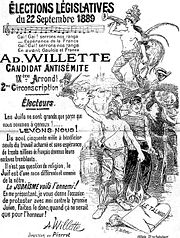

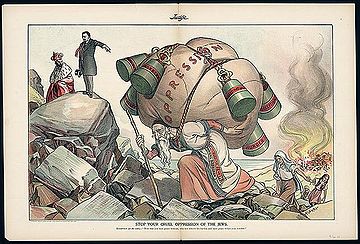

The Dreyfus Affair

was an infamous antisemitic event of the late 19th century and early 20th century. Alfred Dreyfus

, a Jewish artillery captain in the French army, was accused in 1894 of passing secrets to the Germans. As a result of these charges, Dreyfus was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment

at Devil's Island. The actual spy, Marie Charles Esterhazy, was acquitted. The event caused great uproar among the French, with the public choosing sides regarding whether Dreyfus was actually guilty or not. Émile Zola

accused the army of polluting the French justice system. However, general consensus held that Dreyfus was guilty: eighty percent of the press in France condemned him. This attitude among the majority of the French population reveals the underlying antisemitism of the time period.

Adolf Stoecker

(1835–1909), the Lutheran court chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, founded in 1878 an antisemitic, antiliberal political party called The Christian Social Party (Germany)

. However, this party did not attract as many votes as the Nazi party, which flourished in part because of The Great Depression, which hit Germany especially hard during the early 1930s.

Karl Marx

regarded Jews as the embodiment of capitalism

and the creators of its evils. Albert Lindemann

and Hyam Maccoby

have suggested that Marx was embarrassed by his Jewish background

. His work On The Jewish Question

is seen as an antisemitic, and he often used antisemitic epithets in his published and private writings. Marx's equation of Judaism with capitalism, together with his pronouncements on Jews, strongly influenced socialist movements and shaped their attitudes and policies toward the Jews. Marx's On the Jewish Question influenced National Socialist

, as well as Soviet and Arab antisemites.

Between 1900 and 1924, approximately 1.75 million Jews migrated to America, the bulk from Eastern Europe. Before 1900 American Jews had always amounted to less than 1 percent of America's total population, but by 1930 Jews formed about 3½ percent. This increase, combined with the upward social mobility of some Jews, contributed to a resurgence of antisemitism. In the first half of the 20th century, in the USA, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrolment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. The lynching of Leo Frank

Between 1900 and 1924, approximately 1.75 million Jews migrated to America, the bulk from Eastern Europe. Before 1900 American Jews had always amounted to less than 1 percent of America's total population, but by 1930 Jews formed about 3½ percent. This increase, combined with the upward social mobility of some Jews, contributed to a resurgence of antisemitism. In the first half of the 20th century, in the USA, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrolment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. The lynching of Leo Frank

by a mob of prominent citizens in Marietta

, Georgia

in 1915 turned the spotlight on antisemitism in the United States. The case was also used to build support for the renewal of the Ku Klux Klan

which had been inactive since 1870.

In the beginning of 20th century, the Beilis Trial

in Russia represented incidents of blood-libel in Europe. Christians used allegations of Jews killing Christians as justification for killing of Jews.

Antisemitism in America reached its peak during the interwar period. The pioneer automobile manufacturer Henry Ford

propagated antisemitic ideas in his newspaper The Dearborn Independent

(published by Ford from 1919 to 1927). The radio speeches of Father Coughlin in the late 1930s attacked Franklin D. Roosevelt

's New Deal

and promoted the notion of a Jewish financial conspiracy. Some prominent politicians shared such views: Louis T. McFadden, Chairman of the United States House Committee on Banking and Currency, blamed Jews for Roosevelt's decision to abandon the gold standard

, and claimed that "in the United States today, the Gentiles have the slips of paper while the Jews have the lawful money".

In the 1940s the aviator

In the 1940s the aviator

Charles Lindbergh

and many prominent Americans led The America First Committee

in opposing any involvement in the war against Fascism

. During his July 1936 visit to Germany, he wrote letters saying that there was "more intelligent leadership in Germany than is generally recognized".

The German American Bund held parades in New York City during the late 1930s, where members wore Nazi uniforms and raised flags featuring swastika

s alongside American flags. With the start of U.S. involvement in World War II

most of the Bund's members were placed in internment camps, and some were deported at the end of the war.

Sometimes race riots, as in Detroit in 1943, targeted Jewish businesses for looting and burning.

In Germany the National Socialist regime of Adolf Hitler

In Germany the National Socialist regime of Adolf Hitler

, which came to power on 30 January 1933, instituted repressive legislation denying the Jews basic civil rights. It instituted a pogrom on the night of 9–10 November 1938, dubbed Kristallnacht

, in which Jews were killed, their property destroyed and their synagogues torched. Antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were extended to Nazi-occupied Europe in the wake of conquest, often building on local antisemitic traditions. In the east the Third Reich forced Jews into ghettos in Warsaw

, Krakow

, Lvov, Lublin

and Radom

. After the invasion of Russia in 1941 a campaign of mass murder, conducted by the Einsatzgruppen

, culminated between 1942 to 1945 in systematic genocide

: the Holocaust

. Eleven million Jews were targeted for extermination by the Nazis, and some six million were eventually killed.

Antisemitism was commonly used as an instrument for personal conflicts in Soviet Russia, starting from conflict between Joseph Stalin

and Leon Trotsky

and continuing through numerous conspiracy-theories spread by official propaganda. Antisemitism in the USSR reached new heights after 1948 during the campaign against the "rootless cosmopolitan"

(euphemism for "Jew") in which numerous Yiddish-language poets, writers, painters and sculptors were killed or arrested. This culminated in the so-called Doctors' Plot

(1952–1953). Similar antisemitic propaganda in Poland resulted in the flight of Polish Jewish survivors from the country.

After the war, the Kielce pogrom

and "March 1968 events" in communist Poland represented further incidents of antisemitism in Europe. The anti-Jewish violence in postwar Poland has a common theme of blood-libel

rumours.

In 1965 Pope Paul VI

disbanded the cult of Simon of Trent

, and the shrine erected to him was dismantled. He was removed from the Roman Catholic calendar of saints, and his future veneration was forbidden, though a handful of extremists still promote the Simon of Trent narrative as fact.

found that there was an increase in antisemitism across the world, and that both old and new expressions of antisemitism persist.

(ADL) concluded that 15% of Americans hold antisemitic views, which was in-line with the average of the previous ten years, but a decline from the 29% of the early sixties. The survey concluded that education was a strong predictor, “with most educated Americans being remarkably free of prejudicial views.” The belief that Jews have too much power was considered a common anti-Semitic view by the ADL. Other views indicating antisemitism, according to the survey, include the view that Jews are more loyal to Israel than America, and that they are responsible for the death of Christ. The survey found that antisemitic Americans are likely to be intolerant generally, e.g. regarding immigration and free-speech.

In November 2005, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights examined antisemitism on college campuses. It reported that "incidents of threatened bodily injury, physical intimidation or property damage are now rare", but antisemitism still occurs on many campuses and is a "serious problem." The Commission recommended that the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights

protect college students from antisemitism through vigorous enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and further recommended that Congress

clarify that Title VI applies to discrimination against Jewish students.

On September 19, 2006, Yale University

founded the Yale Initiative for the Interdisciplinary Study of Anti-Semitism (YIISA), the first North American university-based center for study of the subject, as part of its Institution for Social and Policy Studies. Director Charles Small

of the Center cited the increase in antisemitism worldwide in recent years as generating a "need to understand the current manifestation of this disease". In June 2011, Yale voted to close this initiative. After carrying out a routine review, the faculty review committee said that the initiative had not met its research and teaching standards. Donald Green, who heads Yale’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies, the body under whose aegis the antisemitism initiative was run, said that it had not had many papers published in the relevant leading journals or attracted many students. As with other programs that had been in a similar situation, the initiative had therefore been cancelled. This decision has been criticized by figures such as former U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Staff Director Kenneth L. Marcus

, who is now the director of the Initiative to Combat Anti-Semitism and Anti-Israelism in America’s Educational Systems at the Institute for Jewish and Community Research, and Deborah Lipstadt

, who described the decision as "weird" and "strange." Antony Lerman

has supported Yale's decision, describing the YIISA as a politicized initiative that was devoted to the promotion of Israel rather than to serious research on antisemitism.

A 2009 study published in Boston Review

found that nearly 25 percent of non-Jewish Americans blamed Jews for the financial crisis of 2008–2009, with a higher percentage among Democrats than Republicans.

, antisemitism had increased significantly in Europe since 2000, with significant increases in verbal attacks against Jews and vandalism such as graffiti, fire bombings of Jewish schools, desecration of synagogues and cemeteries. Germany, France, Britain

and Russia are the countries with the highest rate of antisemitic incidents in Europe. The Netherlands and Sweden have also consistently had high rates of antisemitic attacks since 2000.

Much of the new European antisemitic violence can actually be seen as a spill over from the long running Arab-Israeli conflict since the majority of the perpetrators are from the large Muslim immigrant communities in European cities

. However, compared to France, the United Kingdom and much of the rest of Europe, in Germany Arab and pro-Palestinian groups are involved in only a small percentage of antisemitic incidents. According to The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism, most of the more extreme attacks on Jewish sites and physical attacks on Jews in Europe come from militant Islamic and Muslim groups, and most Jews tend to be assaulted in countries where groups of young Muslim immigrants reside.

On January 1, 2006, Britain's chief rabbi

, Lord Jonathan Sacks

, warned that what he called a "tsunami of antisemitism" was spreading globally. In an interview with BBC Radio 4

, Sacks said: "A number of my rabbinical colleagues throughout Europe have been assaulted and attacked on the streets. We've had synagogues desecrated. We've had Jewish schools burnt to the ground – not here but in France. People are attempting to silence and even ban Jewish societies on campuses on the grounds that Jews must support the state of Israel, therefore they should be banned, which is quite extraordinary because ... British Jews see themselves as British citizens. So it's that kind of feeling that you don't know what's going to happen next that's making ... some European Jewish communities uncomfortable."

, points out the official policy of Germany: "We will not tolerate any form of extremism, xenophobia or anti-Semitism." Although the number of extreme right-wing groups and organisations grew from 141 (2001) to 182 (2006), especially in the formerly communist East Germany, Germany's measures against right wing groups and antisemitism are effective, despite Germany having the highest rates of antisemitic acts in Europe. According to the annual reports of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution the overall number of far-right extremists in Germany dropped during the last years from 49,700 (2001), 45,000 (2002), 41,500 (2003), 40,700 (2004), 39,000 (2005), to 38,600 in 2006. Germany provided several million Euros to fund "nationwide programs aimed at fighting far-right extremism, including teams of traveling consultants, and victims' groups."

descent. According to the Centre for Information and Documentation on Israel, a pro-Israel lobby group in the Netherlands, in 2009, the number of antisemitic incidents in Amsterdam

, the city that is home to most of the approximately 40,000 Dutch Jews

, was said to be doubled compared to 2008. In 2010, Raphaël Evers, an orthodox

rabbi in Amsterdam

, told the Norwegian newspaper aftenposten

that Jews can no longer be safe in the city anymore due to the risk of violent assaults. "Jews no longer feel at home in the city. Many are considering aliyah

to Israel

."

set up an inquiry into antisemitism, which published its findings in 2006. Its report stated that "until recently, the prevailing opinion both within the Jewish community and beyond [had been] that antisemitism had receded to the point that it existed only on the margins of society." It found a reversal of this progress since 2000. It aimed to investigate the problem, identify the sources of contemporary antisemitism and make recommendations to improve the situation. It discussed the influence of the Israel-Palestine conflict and issues of anti-Israel sentiment versus antisemitism at length and noted "most of those who gave evidence were at pains to explain that criticism of Israel is not to be regarded in itself as antisemitic ... The Israeli government itself may, at times, have mistakenly perceived criticism of its policies and actions to be motivated by antisemitism."

or African heritage, but also growing among Caribbean

islanders from former French colonies.

Former Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy

denounced the killing of Ilan Halimi

on 13 February 2006 as an antisemitic crime.

Jewish philanthropist Baron Eric de Rothschild suggests that the extent of antisemitism in France has been exaggerated. In an interview with The Jerusalem Post

he says that "the one thing you can't say is that France is an anti-Semitic country."

s revealed that Muslim students often "praise or admire Adolf Hitler

for his killing of Jews", that "Jew-hate is legitimate within vast groups of Muslim students" and that "Muslims laugh or command [teachers] to stop when trying to educate about the Holocaust". Additionally, "while some students might protest when some express support for terrorism

, none object when students express hate of Jews", saying that it says in "the Quran that you shall kill Jews, all true Muslims hate Jews". Most of these students were said to be born and raised in Norway. One Jewish father also stated that his child had been taken by a Muslim mob after school (though the child managed to escape), reportedly "to be taken out to the forest and hung

because he was a Jew".

Norwegian Education Minister Kristin Halvorsen referred to the antisemitism reported in this study as being “completely unacceptable.” The head of a local Islamic council joined Jewish leaders and Halvorsen in denouncing such antisemitism.

described these results as "surprising and terrifying". However, the Rabbi of Stockholm's Orthodox Jewish community, Meir Horden claimed that "It's not true to say that the Swedes are anti-Semitic. Some of them are hostile to Israel because they support the weak side, which they perceive the Palestinians to be."

In early 2010, the Swedish publication The Local published series of articles about the growing anti-Semitism in Malmö, Sweden. In an interview in January 2010, Fredrik Sieradzki of the Jewish Community of Malmö stated that "Threats against Jews have increased steadily in Malmö in recent years and many young Jewish families are choosing to leave the city. Many feel that the community and local politicians have shown a lack of understanding for how the city's Jewish residents have been marginalized." He also added that "right now many Jews in Malmö are really concerned about the situation here and don't believe they have a future here." The Local also reported that Jewish cemeteries and synagogues have repeatedly been defaced with anti-Semitic graffiti, and a chapel at another Jewish burial site in Malmö was firebombed in 2009. In 2009 the Malmö police received reports of 79 anti-Semitic incidents, double the number of the previous year (2008). Fredrik Sieradzki, spokesman for the Malmo Jewish community, estimated that the already small Jewish population is shrinking by 5% a year. "Malmo is a place to move away from," he said, citing anti-Semitism as the primary reason.

In March 2010, Fredrik Sieradzk told Die Presse, an Austrian Internet publication, that Jews are being "harassed and physically attacked" by "people from the Middle East," although he added that only a small number of Malmo's 40,000 Muslims "exhibit hatred of Jews." Sieradzk also stated that approximately 30 Jewish families have emigrated from Malmo to Israel in the past year, specifically to escape from harassment. Also in March, the Swedish newspaper Skånska Dagbladet reported that attacks on Jews in Malmo totaled 79 in 2009, about twice as many as the previous year, according to police statistics.

In October 2010, The Forward reported on the current state of Jews and the level of Anti-semitism in Sweden. Henrik Bachner, a writer and professor of history at the University of Lund, claimed that members of the Swedish Parliament have attended anti-Israel rallies where the Israeli flag was burned while the flags of Hamas and Hezbollah were waved, and the rhetoric was often anti-Semitic—not just anti-Israel. But such public rhetoric is not branded hateful and denounced. Charles Small, director of the Yale Initiative for the Interdisciplinary Study of Antisemitism, stated that "Sweden is a microcosm of contemporary anti-Semitism. It's a form of acquiescence to radical Islam, which is diametrically opposed to everything Sweden stands for." Per Gudmundson, chief editorial writer for Svenska Dagbladet, has sharply criticized politicians who offer "weak excuses" for Muslims accused of anti-Semitic crimes. "Politicians say these kids are poor and oppressed, and we have made them hate. They are, in effect, saying the behavior of these kids is in some way our fault." Judith Popinski, an 86-year-old Holocaust survivor, stated that she is no longer invited to schools that have a large Muslim presence to tell her story of surviving the Holocaust. Popinski, who found refuge in Malmo in 1945, stated that, until recently, she told her story in Malmo schools as part of their Holocaust studies program, but that now, many schools no longer ask Holocaust survivors to tell their stories, because Muslim students treat them with such disrespect, either ignoring the speakers or walking out of the class. She further stated that "Malmo reminds me of the anti-Semitism I felt as a child in Poland before the war. "I am not safe as a Jew in Sweden anymore."

In December 2010, the Jewish

human rights

organization Simon Wiesenthal Center

issued a travel advisory concerning Sweden, advising Jews to express "extreme caution" when visiting the southern parts of the country due to an increase in verbal and physical harassment of Jewish citizens in the city of Malmö

.

, founder of Human Rights Watch

, says that anti-Semitism is "deeply ingrained and institutionalized" in "Arab nations in modern times."

Mudar Zahran, a Palestinian, writing for the Hudson Institute

says that "the Palestinians have been used as fuel for the new form of anti-Semitism; this has hurt the Palestinians and exposed them to unprecedented and purposely media-ignored abuse by Arab governments, including some of those who claim love for the Palestinians, yet in fact only bear hatred to Jews. This has resulted in Palestinian cries for justice, equality, freedom and even basic human rights being ignored while the world getting consumed with delegitimizing Israel from either ignorance or malice."

In a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center

, all of the Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries polled held strongly negative views of Jews. In the questionnaire, only 2 percent of Egypt

ians, 3 percent of Lebanese

Muslims, and 2 percent of Jordan

ians reported having a positive view of Jews. Muslim-majority countries outside the Middle East held similarly negative views, with 4 percent of Turks

and 9 percent of Indonesia

ns viewing Jews favorably.

Edward Rothstein

Edward Rothstein

, cultural critic of The New York Times

, writes that some of the dialogue from Middle East media and commentators about Jews bear a striking resemblance to Nazi propaganda

. According to Josef Joffe of Newsweek

, "anti-Semitism—the real stuff, not just bad-mouthing particular Israeli policies—is as much part of Arab life today as the hijab or the hookah. Whereas this darkest of creeds is no longer tolerated in polite society in the West, in the Arab world, Jew hatred remains culturally endemic."

In the Middle East, anti-Zionist propaganda frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders.

In Egypt

, Dar al-Fadhilah published a translation of Henry Ford

's antisemitic treatise, The International Jew

, complete with distinctly antisemitic imagery on the cover.

The website of the Saudi Arabia

n Supreme Commission for Tourism

initially stated that Jews would not be granted tourist visas to enter the country.

The Saudi embassy in the U.S. distanced itself from the statement, which was later removed. Members of religions other than Islam, including Jews, are not permitted to practice their religion publicly in Saudi Arabia.

In 2001, Arab Radio and Television of Saudi Arabia produced a 30-part television miniseries entitled "Horseman Without a Horse", a dramatization of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

. One Saudi Arabian government newspaper suggested that hatred of all Jews is justifiable.

Saudi textbooks vilify Jews (and Christians and non-Wahabi Muslims): according to the May 21, 2006 issue of The Washington Post

, Saudi textbooks claimed by them to have been sanitized of antisemitism still call Jews apes (and Christians swine); demand that students avoid and not befriend Jews; claim that Jews worship the devil; and encourage Muslims to engage in Jihad to vanquish Jews.

The Center for Religious Freedom of Freedom House

analyzed a set of Saudi Ministry of Education textbooks in Islamic studies courses for elementary and secondary school students. The researchers found statements promoting hate of Christians, Jews, "polytheists" and other "unbelievers," including non-Wahhabi Muslims. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

was taught as historical fact. The texts described Jews and Christians as enemies of Muslim believers and the clash between them as an ongoing fight that will end in victory over the Jews. Jews were blamed for virtually all the "subversion" and wars of the modern world. A of Saudi Arabia's curriculum has been released to the press by the Hudson Institute

.

Al-Manar

recently aired a drama series, The Diaspora, which observers allege is based on historical antisemitic allegations. BBC

correspondents who have watched the program says it quotes extensively from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Muslim clerics in the Middle East have frequently referred to Jews as descendants of apes and pigs, which are conventional epithets for Jews and Christians. Abdul Rahman Al-Sudais

is the leading imam

of the Grand mosque

located in the Islamic holy city of Mecca

, Saudi Arabia

. The BBC

aired a Panorama

episode, entitled A Question of Leadership, which reported that al-Sudais referred to Jews as "the scum of the human race" and "offspring of apes and pigs", and stated, "the worst [...] of the enemies of Islam are those [...] whom he [...] made monkeys and pigs, the aggressive Jews and oppressive Zionists and those that follow them [...] Monkeys and pigs and worshippers of false Gods who are the Jews and the Zionists." In another sermon, on April 19, 2002, he declared that Jews are "evil offspring, infidels, distorters of [others'] words, calf-worshippers, prophet-murderers, prophecy-deniers [...] the scum of the human race whom Allah cursed and turned into apes and pigs [...]"

On May 5, 2001, after Shimon Peres

visited Egypt

, the Egyptian al-Akhbar internet paper said that "lies and deceit are not foreign to Jews[...]. For this reason, Allah changed their shape and made them into monkeys and pigs."

In Israel, Zalman Gilichenski has warned about the spread of antisemitism among immigrants from Russia in the last decade.

was targeted in a car bombing, killing 21 Turkish Muslims and 6 Jews.

In June 2011, the Economist suggested that "The best way for Turks to promote democracy would be to vote against the ruling party". Not long after, the Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

, said that "The international media, as they are supported by Israel, would not be happy with the continuation of the AKP government". The Hurriyet Daily News went further by stating that "The Economist is part of an Israeli conspiracy that aims to topple the Turkish government".

Moreover, during Erdogan's tenure, Hitler's Mein Kampf has once again become a best selling book in Turkey. Prime Minister Erdogan called antisemitism a "crime against humanity." He also said that "as a minority, they're our citizens. Both their security and the right to observe their faith are under our guarantee."

Discrimination

Discrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

against Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

for reasons connected to their Jewish

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

heritage. According to a 2005 U.S. governmental report, antisemitism is "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity." In an extreme form, it "attributes to the Jews an exceptional position among all other civilizations, defames them as an inferior group and denies their being part of the nation[s]" in which they reside. A person who holds such views is called an "antisemite".

Antisemitism may be manifested in many ways, ranging from expressions of hatred of or discrimination

Discrimination

Discrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

against individual Jews to organized violent attacks by mobs, or even state police, or military attacks on entire Jewish communities. Extreme instances of persecution

Persecution of Jews

Persecution of Jews has occurred on numerous occasions and at widely different geographical locations. As well as being a major component in Jewish history, it has significantly affected the general history and social development of the countries and societies in which the persecuted Jews...

include the pogroms which preceded the First Crusade in 1096, the expulsion from England

Edict of Expulsion

In 1290, King Edward I issued an edict expelling all Jews from England. Lasting for the rest of the Middle Ages, it would be over 350 years until it was formally overturned in 1656...

in 1290, the massacres of Spanish Jews in 1391, the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition

Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition , commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition , was a tribunal established in 1480 by Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms, and to replace the Medieval...

, the expulsion from Spain

Alhambra decree

The Alhambra Decree was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ordering the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Spain and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.The edict was formally revoked on 16 December 1968, following the Second...

in 1492, the expulsion from Portugal in 1497, various Russian pogroms, the Dreyfus Affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

, and the Final Solution

The Final Solution

The Final Solution is a 2004 novel by Michael Chabon. It is a detective story that in many ways pays homage to the writings of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and other writers of the genre...

by Hitler's Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and official Soviet

History of the Jews in the Soviet Union

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is discussed in the following articles relating to specific regions of the former Soviet Union:*History of the Jews in Armenia*History of the Jews in Azerbaijan*History of the Jews in Belarus...

anti-Jewish policies.

While the term's etymology

Etymology

Etymology is the study of the history of words, their origins, and how their form and meaning have changed over time.For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts in these languages and texts about the languages to gather knowledge about how words were used during...

might suggest that antisemitism is directed against all Semitic peoples, the term was coined in the late 19th century in Germany as a more scientific-sounding term for Judenhass ("Jew-hatred"),

and that has been its normal use since then.

Usage

Despite the use of the prefix anti-, the terms Semitic and anti-Semitic are not directly opposed to each other. Antisemitism refers specifically to prejudice against Jews alone and in general, despite the fact that there are other speakers of Semitic languages (e.g. ArabArab

Arab people, also known as Arabs , are a panethnicity primarily living in the Arab world, which is located in Western Asia and North Africa. They are identified as such on one or more of genealogical, linguistic, or cultural grounds, with tribal affiliations, and intra-tribal relationships playing...

s, Ethiopians, or Assyrians

Assyrian people

The Assyrian people are a distinct ethnic group whose origins lie in ancient Mesopotamia...

) and that not all Jews speak a Semitic language.

The term anti-Semitic has been used on occasion to include bigotry against other Semitic-language peoples such as Arabs, but such usage is not widely accepted.

Both terms anti-Semitism and antisemitism are in common use. Some scholars favor the unhyphenated form antisemitism to avoid possible confusion involving whether the term refers specifically to Jews, or to Semitic

Semitic

In linguistics and ethnology, Semitic was first used to refer to a language family of largely Middle Eastern origin, now called the Semitic languages...

-language speakers as a whole. For example, Emil Fackenheim

Emil Fackenheim

Emil Ludwig Fackenheim, Ph.D. was a noted Jewish philosopher and Reform rabbi.Born in Halle, Germany, he was arrested by the Nazis on the night of November 9, 1938, known as Kristallnacht...

supported the unhyphenated spelling, in order to "dispel[] the notion that there is an entity 'Semitism' which 'anti-Semitism' opposes."

Etymology

Wilhelm Marr

Wilhelm Marr was a German agitator and publicist, who coined the term "antisemitism" .-Life:Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son of an actor and stage director. He went to a primary school in Hannover, then to a high school in Braunschweig...

is generally credited with coining the word anti-Semitism (see below), Alex Bein

Alex Bein

Alex Bein was a Jewish scholar in Jewish culture and history, one of the founders of Zionist historiography...

writes that the word was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider

Moritz Steinschneider

Moritz Steinschneider was a Bohemian bibliographer and Orientalist. He received his early instruction in Hebrew from his father, Jacob Steinschneider , who was not only an expert Talmudist, but was also well versed in secular science...

in the phrase "anti-Semitic prejudices". Steinschneider used this phrase to characterize Ernest Renan

Ernest Renan

Ernest Renan was a French expert of Middle East ancient languages and civilizations, philosopher and writer, devoted to his native province of Brittany...

's ideas about how "Semitic

Semitic

In linguistics and ethnology, Semitic was first used to refer to a language family of largely Middle Eastern origin, now called the Semitic languages...

races" were inferior to "Aryan

Aryan

Aryan is an English language loanword derived from Sanskrit ārya and denoting variously*In scholarly usage:**Indo-Iranian languages *in dated usage:**the Indo-European languages more generally and their speakers...

races." These pseudo-scientific

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice which is presented as scientific, but which does not adhere to a valid scientific method, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, cannot be reliably tested, or otherwise lacks scientific status...

theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke

Heinrich von Treitschke

Heinrich Gotthard von Treitschke was a nationalist German historian and political writer during the time of the German Empire.-Early life and teaching career:...

did much to promote this form of racism. He coined the term "the Jews are our misfortune" which would later be widely used by Nazis. In Treitschke's writings Semitic was synonymous with Jewish, in contrast to its use by Renan and others.

In 1873 German journalist Wilhelm Marr

Wilhelm Marr

Wilhelm Marr was a German agitator and publicist, who coined the term "antisemitism" .-Life:Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son of an actor and stage director. He went to a primary school in Hannover, then to a high school in Braunschweig...

published a pamphlet "The Victory of the Jewish Spirit over the Germanic Spirit. Observed from a non-religious perspective." ("Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum. Vom nicht confessionellen Standpunkt aus betrachtet.") in which he used the word "Semitismus" interchangeably with the word "Judentum" to denote both "Jewry" (the Jews as a collective) and "jewishness" (the quality of being Jewish, or the Jewish spirit). Although he did not use the word "Antisemitismus" in the pamphlet, the coining of the latter word followed naturally from the word "Semitismus", and indicated either opposition to the Jews as a people, or else opposition to Jewishness or the Jewish spirit, which he saw as infiltrating German culture. In his next pamphlet, "The Way to Victory of the Germanic Spirit over the Jewish Spirit", published in 1880, Marr developed his ideas further and coined the related German word Antisemitismus – antisemitism, derived from the word "Semitismus" that he had earlier used.

The pamphlet became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Antisemites" ("Antisemiten-Liga"), the first German organization committed specifically to combatting the alleged threat to Germany and German culture posed by the Jews and their influence, and advocating their forced removal

Population transfer

Population transfer is the movement of a large group of people from one region to another by state policy or international authority, most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion...

from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published "Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte," and Wilhelm Scherer

Wilhelm Scherer

Wilhelm Scherer , German philologist and historian of literature.-Life:...

used the term "Antisemiten" in the January issue of "Neue Freie Presse". The related word semitism

Philo-Semitism

Philo-Semitism or Judeophilia is an interest in, respect for, and appreciation of the Jewish people, their historical significance and the positive impacts of Judaism in the history of the western world, in particular, generally on the part of a gentile...

was coined around 1885.

Definition

Though the general definition of antisemitism is hostility or prejudice against Jews, a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions. Holocaust scholar and City University of New YorkCity University of New York

The City University of New York is the public university system of New York City, with its administrative offices in Yorkville in Manhattan. It is the largest urban university in the United States, consisting of 23 institutions: 11 senior colleges, six community colleges, the William E...

professor Helen Fein

Helen Fein

Helen Fein is a historical sociologist, Professor, specialized on genocide, human rights, collective violence and other issues. She is an author and editor of 12 books and monographs, Associate of International Security Program , a founder and first President of the International Association of...

defines it as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions – social or legal discrimination, political mobilization against the Jews, and collective or state violence – which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews." Elaborating on Fein's definition, Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne

University of Cologne

The University of Cologne is one of the oldest universities in Europe and, with over 44,000 students, one of the largest universities in Germany. The university is part of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, an association of Germany's leading research universities...

writes that, to antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the antisemites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."

Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, FBA is a British-American historian, scholar in Oriental studies, and political commentator. He is the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University...

defines antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism.

There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. The U.S. Department of State defines antisemitism in its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism as "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (now Fundamental Rights Agency), then an agency of the European Union

European Union

The European Union is an economic and political union of 27 independent member states which are located primarily in Europe. The EU traces its origins from the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community , formed by six countries in 1958...

, developed a more detailed working definition, which states: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." It adds "such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity." It provides contemporary examples of antisemitism, which include: promoting the harming of Jews in the name of an ideology or religion; promoting negative stereotypes of Jews; holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of an individual Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust

Holocaust denial

Holocaust denial is the act of denying the genocide of Jews in World War II, usually referred to as the Holocaust. The key claims of Holocaust denial are: the German Nazi government had no official policy or intention of exterminating Jews, Nazi authorities did not use extermination camps and gas...

or accusing Jews or Israel of exaggerating it; and accusing Jews of dual loyalty

Dual loyalty

In politics, dual loyalty is loyalty to two separate interests that potentially conflict with each other.-Inherently controversial:While nearly all examples of alleged "dual loyalty" are considered highly controversial, these examples point to the inherent difficulty in distinguishing between what...

or a greater allegiance to Israel than their own country. It also lists ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor, or applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, or holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel.

Evolution of usage as a term

In 1879, Wilhelm MarrWilhelm Marr

Wilhelm Marr was a German agitator and publicist, who coined the term "antisemitism" .-Life:Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son of an actor and stage director. He went to a primary school in Hannover, then to a high school in Braunschweig...

founded the Antisemiten-Liga (Antisemitic League). Identification with antisemitism and as an antisemite was politically advantageous in Europe in the latter 19th century. For example, Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger was an Austrian politician and mayor of Vienna. The populist and anti-Semitic politics of his Christian Social Party are sometimes viewed as a model for Hitler's Nazism.- Career :...

, the popular mayor of fin de siècle

Fin de siècle

Fin de siècle is French for "end of the century". The term sometimes encompasses both the closing and onset of an era, as it was felt to be a period of degeneration, but at the same time a period of hope for a new beginning...

Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, skillfully exploited antisemitism as a way of channeling public discontent to his political advantage. In its 1910 obituary of Lueger, The New York Times notes that Lueger was "Chairman of the Christian Social Union of the Parliament and of the Anti-Semitic Union of the Diet of Lower Austria. In 1895 A. C. Cuza

A. C. Cuza

A. C. Cuza was a Romanian far right politician and theorist.-Early life:Born in Iaşi, after attending secondary school in his native city and in Dresden, Cuza studied law at the University of Paris, the Universität unter den Linden, and the Université Libre de Bruxelles...

organized the Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle in Bucharest. In the period before World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, when animosity towards Jews was far more commonplace, it was not uncommon for a person, organization, or political party to self-identify as an antisemite or antisemitic.

The early Zionist pioneer, Judah Leib Pinsker, in a pamphlet written in 1882, said that antisemitism was an inherited predisposition:

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht

Kristallnacht

Kristallnacht, also referred to as the Night of Broken Glass, and also Reichskristallnacht, Pogromnacht, and Novemberpogrome, was a pogrom or series of attacks against Jews throughout Nazi Germany and parts of Austria on 9–10 November 1938.Jewish homes were ransacked, as were shops, towns and...

, Goebbels announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."

After Hitler's fall from power, and particularly after the extent of the Nazi genocide

Genocide