Eugenics

Encyclopedia

Applied science

Applied science is the application of scientific knowledge transferred into a physical environment. Examples include testing a theoretical model through the use of formal science or solving a practical problem through the use of natural science....

or the bio-social movement

Social movement

Social movements are a type of group action. They are large informal groupings of individuals or organizations focused on specific political or social issues, in other words, on carrying out, resisting or undoing a social change....

which advocates the use of practices aimed at improving the genetic composition of a population

Population genetics

Population genetics is the study of allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the four main evolutionary processes: natural selection, genetic drift, mutation and gene flow. It also takes into account the factors of recombination, population subdivision and population...

", usually referring to human populations. The origins of the concept of eugenics began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance is a scientific description of how hereditary characteristics are passed from parent organisms to their offspring; it underlies much of genetics...

, and the theories of August Weismann

August Weismann

Friedrich Leopold August Weismann was a German evolutionary biologist. Ernst Mayr ranked him the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Charles Darwin...

. Historically, many of the practitioners of eugenics viewed eugenics as a science, not necessarily restricted to human populations; this embraced the views of Darwin and Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is a term commonly used for theories of society that emerged in England and the United States in the 1870s, seeking to apply the principles of Darwinian evolution to sociology and politics...

.

Eugenics was widely popular in the early decades of the 20th century. The First International Congress of Eugenics in 1912 was supported by many prominent persons, including: its president Leonard Darwin

Leonard Darwin

Major Leonard Darwin , a son of the English naturalist Charles Darwin, was variously a soldier, politician, economist, eugenicist and mentor of the statistician and evolutionary biologist Ronald Fisher.- Biography :...

, the son of Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

; honorary vice-president Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, then First Lord of the Admiralty and future Prime Minister of the United Kingdom; Auguste Forel, famous Swiss pathologist; Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell was an eminent scientist, inventor, engineer and innovator who is credited with inventing the first practical telephone....

, the inventor of the telephone; among other prominent people. The National Socialists' (NSDAP) approach to genetics and eugenics became focused on Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer was a German professor of medicine, anthropology and eugenics. He was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics between 1927 and 1942...

's concept of phenogenetics and the Nazi twin study

Nazi twin study

The methodology of twin study has been used for fraudulent purposes by many scientists. Two famous examples are the "Burt Affair" and Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer's work at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics....

methods of Fischer and Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer

Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer

Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer was a German human biologist and eugenicist concerned primarily with "racial hygiene" and twin research...

.

Eugenics was a controversial concept even shortly after its creation. The first major challenge to eugenics was made in 1915 by Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist and embryologist and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries relating the role the chromosome plays in heredity.Morgan received his PhD from Johns Hopkins University in zoology...

, who demonstrated the event of genetic mutation

Mutation

In molecular biology and genetics, mutations are changes in a genomic sequence: the DNA sequence of a cell's genome or the DNA or RNA sequence of a virus. They can be defined as sudden and spontaneous changes in the cell. Mutations are caused by radiation, viruses, transposons and mutagenic...

occuring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the birth of a fruit fly

Fruit fly

Fruit fly may refer to several organisms:* Tephritidae, a family of large, colorfully marked flies including agricultural pests* Drosophilidae, a family of smaller flies, including:** Drosophila, the genus of small fruit flies and vinegar flies...

with white eyes from a family and ancestry of the red-eyed Drosophila melanogaster

Drosophila melanogaster

Drosophila melanogaster is a species of Diptera, or the order of flies, in the family Drosophilidae. The species is known generally as the common fruit fly or vinegar fly. Starting from Charles W...

species of fruit fly. Morgan claimed that this demonstrated that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance and that the concept of eugenics based upon genetic inheritance was severely flawed.

By the mid-20th century eugenics had fallen into disfavor, having become associated with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

. Both the public and some elements of the scientific community have associated eugenics with Nazi

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

abuses, such as enforced "racial hygiene

Racial hygiene

Racial hygiene was a set of early twentieth century state sanctioned policies by which certain groups of individuals were allowed to procreate and others not, with the expressed purpose of promoting certain characteristics deemed to be particularly desirable...

", human experimentation

Nazi human experimentation

Nazi human experimentation was a series of medical experiments on large numbers of prisoners by the Nazi German regime in its concentration camps mainly in the early 1940s, during World War II and the Holocaust. Prisoners were coerced into participating: they did not willingly volunteer and there...

, and the extermination

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

of "undesired" population groups. However, developments in genetic

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

, genomic

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is among the newest and most sophisticated of techniques used to test for genetic disorders which involves direct examination of the DNA molecule itself. Other genetic tests include biochemical tests for such gene products as enzymes and other proteins and for microscopic...

, and reproductive technologies

Human cloning

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. It does not usually refer to monozygotic multiple births nor the reproduction of human cells or tissue. The ethics of cloning is an extremely controversial issue...

at the end of the 20th century have raised many new questions and concerns about the meaning of eugenics and its ethical and moral status in the modern era, effectively creating a resurgence of interest in eugenics.

Overview

As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century. By the end of World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

eugenics had been largely abandoned. Although current trends in genetics have raised questions amongst critical academics concerning parallels between pre-war attitudes about eugenics and current "utilitarian" and social theories allegedly related to Darwinism, they are, in fact, only superficially related and somewhat contradictory to one another. At its pre-war height, the movement often pursued pseudoscientific notions of racial supremacy and purity.

Eugenics was practiced around the world and was promoted by governments, and influential individuals and institutions. Its advocates regarded it as a social philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

for the improvement of human

Human

Humans are the only living species in the Homo genus...

hereditary traits through the promotion of higher reproduction of certain people and traits, and the reduction of reproduction of other people and traits.

Today it is widely regarded as a brutal movement which inflicted massive human rights

Human rights

Human rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...

violations on millions of people. The "interventions" advocated and practiced by eugenicists involved prominently the identification and classification of individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, homosexuals and entire racial groups -- such as the Roma and Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

-- as "degenerate" or "unfit"; the segregation or institutionalisation of such individuals and groups, their sterilization, euthanasia, and in the extreme case of Nazi Germany, their mass extermination.

The practices engaged in by eugenicists involving violations of privacy, attacks on reputation, violations of the right to life, to found a family, to freedom from discrimination are all today classified as violations of human rights

Human rights

Human rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...

. The practice of negative racial aspects of eugenics, after World War II, fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 as General Assembly Resolution 260. The Convention entered into force on 12 January 1951. It defines genocide in legal terms, and is the culmination of...

.

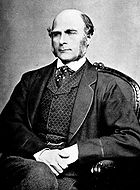

The modern field and term were first formulated by Sir Francis Galton

Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton /ˈfrɑːnsɪs ˈgɔːltn̩/ FRS , cousin of Douglas Strutt Galton, half-cousin of Charles Darwin, was an English Victorian polymath: anthropologist, eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, psychometrician, and statistician...

in 1883, drawing on the recent work of his half-cousin Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

. At its peak of popularity eugenics was supported by a wide variety of prominent people, including Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, Margaret Sanger

Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger was an American sex educator, nurse, and birth control activist. Sanger coined the term birth control, opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, and established Planned Parenthood...

, Marie Stopes

Marie Stopes

Marie Carmichael Stopes was a British author, palaeobotanist, campaigner for women's rights and pioneer in the field of birth control...

, H. G. Wells

H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells was an English author, now best known for his work in the science fiction genre. He was also a prolific writer in many other genres, including contemporary novels, history, politics and social commentary, even writing text books and rules for war games...

, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

, John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA , was a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments...

, John Harvey Kellogg

John Harvey Kellogg

John Harvey Kellogg was an American medical doctor in Battle Creek, Michigan, who ran a sanitarium using holistic methods, with a particular focus on nutrition, enemas and exercise. Kellogg was an advocate of vegetarianism and is best known for the invention of the corn flakes breakfast cereal...

, Linus Pauling

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling was an American chemist, biochemist, peace activist, author, and educator. He was one of the most influential chemists in history and ranks among the most important scientists of the 20th century...

and Sidney Webb. Many members of the American Progressive Movement supported eugenics, seduced by its scientific trappings and its promise of a quick end to social ills. Its most infamous proponent and practitioner was, however, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

who praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf is a book written by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. It combines elements of autobiography with an exposition of Hitler's political ideology. Volume 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926...

and emulated Eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States.

The American sociologist Lester Frank Ward

Lester Frank Ward

Lester F. Ward was an American botanist, paleontologist, and sociologist. He served as the first president of the American Sociological Association.-Biography:...

and the English writer G. K. Chesterton

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG was an English writer. His prolific and diverse output included philosophy, ontology, poetry, plays, journalism, public lectures and debates, literary and art criticism, biography, Christian apologetics, and fiction, including fantasy and detective fiction....

were early critics of the philosophy of eugenics. Ward's 1913 article "Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics" and Chesterton's 1917 book Eugenics and Other Evils were harshly critical of the rapidly growing eugenics movement.

Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities, and received funding from many sources. Three International Eugenics Conference

International Eugenics Conference

Three International Eugenics Congresses took place between 1912 and 1932 and were the global venue for scientists, politicians, and social leaders to plan and discuss the application of programs to improve human heredity in the early twentieth century....

s presented a global venue for eugenicists with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York. Eugenic policies were first implemented in the early 1900s in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Later, in the 1920s and 30s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing

Compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization also known as forced sterilization programs are government policies which attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization...

certain mental patients was implemented in a variety of other countries, including Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, and Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, among others. The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin

Ernst Rüdin

Ernst Rüdin , was a Swiss psychiatrist, geneticist and eugenicist. Rüdin was born in St. Gallen, Switzerland...

used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies

Racial policy of Nazi Germany

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented by Nazi Germany, asserting the superiority of the "Aryan race", and based on a specific racist doctrine which claimed scientific legitimacy...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, and when proponents of eugenics among scientists and thinkers prompted a backlash in the public. Nevertheless, in Sweden the eugenics program continued until 1975.

Since the postwar

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

period, both the public and the scientific communities have associated eugenics with Nazi

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

abuses, such as enforced racial hygiene

Racial hygiene

Racial hygiene was a set of early twentieth century state sanctioned policies by which certain groups of individuals were allowed to procreate and others not, with the expressed purpose of promoting certain characteristics deemed to be particularly desirable...

, human experimentation

Human experimentation

Human subject research includes experiments and observational studies. Human subjects are commonly participants in research on basic biology, clinical medicine, nursing, psychology, and all other social sciences. Humans have been participants in research since the earliest studies...

, and the extermination

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

of "undesired" population groups. However, developments in genetic, genomic, and reproductive technologies at the end of the 20th century have raised many new questions and concerns about what exactly constitutes the meaning of eugenics and what its ethical and moral status is in the modern era.

Meanings and types

The word eugenics derivesEtymology

Etymology is the study of the history of words, their origins, and how their form and meaning have changed over time.For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts in these languages and texts about the languages to gather knowledge about how words were used during...

from the Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

word eu (good or well) and the suffix -genēs (born), and was coined by Sir Francis Galton in 1883 to replace the word stirpiculture (also see: Oneida stirpiculture

Oneida stirpiculture

Stirpiculture is a word coined by John Humphrey Noyes, founder of the Oneida Community, to refer to eugenics, or the breeding of humans to achieve desired perfections within the species...

) which he had used previously but which had come to be mocked by people of culture due to its perceived sexual overtones. Galton defined eugenics as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations". Eugenics has, from the very beginning, meant many different things to many different people. Historically, the term has referred to everything from prenatal care for mothers to forced sterilization and euthanasia

Euthanasia

Euthanasia refers to the practice of intentionally ending a life in order to relieve pain and suffering....

. To population geneticists

Population genetics

Population genetics is the study of allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the four main evolutionary processes: natural selection, genetic drift, mutation and gene flow. It also takes into account the factors of recombination, population subdivision and population...

the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding

Inbreeding

Inbreeding is the reproduction from the mating of two genetically related parents. Inbreeding results in increased homozygosity, which can increase the chances of offspring being affected by recessive or deleterious traits. This generally leads to a decreased fitness of a population, which is...

without necessarily altering allele

Allele

An allele is one of two or more forms of a gene or a genetic locus . "Allel" is an abbreviation of allelomorph. Sometimes, different alleles can result in different observable phenotypic traits, such as different pigmentation...

frequencies; for example, J. B. S. Haldane

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane FRS , known as Jack , was a British-born geneticist and evolutionary biologist. A staunch Marxist, he was critical of Britain's role in the Suez Crisis, and chose to leave Oxford and moved to India and became an Indian citizen...

wrote that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent". Much debate has taken place in the past, as it does today, as to what exactly counts as eugenics. Some types of eugenics deal only with perceived beneficial and/or detrimental genetic traits. These are sometimes called "pseudo-eugenics" by proponents of strict eugenics.

The term eugenics is often used to refer to movements and social policies influential during the early 20th century. In a historical and broader sense, eugenics can also be a study of "improving human genetic qualities". It is sometimes broadly applied to describe any human action whose goal is to improve the gene pool

Gene pool

In population genetics, a gene pool is the complete set of unique alleles in a species or population.- Description :A large gene pool indicates extensive genetic diversity, which is associated with robust populations that can survive bouts of intense selection...

. Some forms of infanticide

Infanticide

Infanticide or infant homicide is the killing of a human infant. Neonaticide, a killing within 24 hours of a baby's birth, is most commonly done by the mother.In many past societies, certain forms of infanticide were considered permissible...

in ancient societies, present-day reprogenetics

Reprogenetics

Reprogenetics is a term referring to the merging of reproductive and genetic technologies expected to happen in the near future as techniques like germinal choice technology become more available and more powerful. The term was coined by Lee M...

, preemptive abortions and designer babies have been (sometimes controversially) referred to as eugenic. Because of its normative

Norm (philosophy)

Norms are concepts of practical import, oriented to effecting an action, rather than conceptual abstractions that describe, explain, and express. Normative sentences imply “ought-to” types of statements and assertions, in distinction to sentences that provide “is” types of statements and assertions...

goals and historical association with scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

, as well as the development of the science of genetics

Genetics

Genetics , a discipline of biology, is the science of genes, heredity, and variation in living organisms....

, the western scientific community has mostly disassociated itself from the term "eugenics", although one can find advocates of what is now known as liberal eugenics

Liberal eugenics

Liberal eugenics is an ideology which advocates the use of reproductive and genetic technologies where the choice of enhancing human characteristics and capacities is left to the individual preferences of parents acting as consumers, rather than the public health policies of the state.-History:The...

. Despite its ongoing criticism in the United States, several regions globally practice different forms of eugenics.

Eugenicists advocate specific policies that (if successful) they believe will lead to a perceived improvement of the human gene pool. Since defining what improvements are desired or beneficial is perceived by many as a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined objectively (e.g., by empirical, scientific inquiry), eugenics has often been deemed a pseudoscience

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice which is presented as scientific, but which does not adhere to a valid scientific method, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, cannot be reliably tested, or otherwise lacks scientific status...

. The most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. This aspect of eugenics has historically been tainted with scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

.

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with perceived intelligence factors that often correlated strongly with social class

Social class

Social classes are economic or cultural arrangements of groups in society. Class is an essential object of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, economists, anthropologists and social historians. In the social sciences, social class is often discussed in terms of 'social stratification'...

. Many eugenicists took inspiration from the selective breeding

Selective breeding

Selective breeding is the process of breeding plants and animals for particular genetic traits. Typically, strains that are selectively bred are domesticated, and the breeding is sometimes done by a professional breeder. Bred animals are known as breeds, while bred plants are known as varieties,...

of animals (where purebred

Purebred

Purebreds, also called purebreeds, are cultivated varieties or cultivars of an animal species, achieved through the process of selective breeding...

s are often strived for) as their analogy for improving human society. The mixing of races (or miscegenation

Miscegenation

Miscegenation is the mixing of different racial groups through marriage, cohabitation, sexual relations, and procreation....

) was usually considered as something to be avoided in the name of racial purity. At the time this concept appeared to have some scientific support, and it remained a contentious issue until the advanced development of genetics

Genetics

Genetics , a discipline of biology, is the science of genes, heredity, and variation in living organisms....

led to a scientific consensus that the division of the human species into unequal races is unjustifiable.

Eugenics has also been concerned with the elimination of hereditary diseases such as hemophilia

Haemophilia

Haemophilia is a group of hereditary genetic disorders that impair the body's ability to control blood clotting or coagulation, which is used to stop bleeding when a blood vessel is broken. Haemophilia A is the most common form of the disorder, present in about 1 in 5,000–10,000 male births...

and Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease, chorea, or disorder , is a neurodegenerative genetic disorder that affects muscle coordination and leads to cognitive decline and dementia. It typically becomes noticeable in middle age. HD is the most common genetic cause of abnormal involuntary writhing movements called chorea...

. However, there are several problems with labeling certain factors as genetic defects. In many cases there is no scientific consensus on what a genetic defect is. It is often argued that this is more a matter of social or individual choice. What appears to be a genetic defect in one context or environment may not be so in another. This can be the case for genes with a heterozygote advantage

Heterozygote advantage

A heterozygote advantage describes the case in which the heterozygote genotype has a higher relative fitness than either the homozygote dominant or homozygote recessive genotype. The specific case of heterozygote advantage is due to a single locus known as overdominance...

, such as sickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease , or sickle-cell anaemia or drepanocytosis, is an autosomal recessive genetic blood disorder with overdominance, characterized by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. Sickling decreases the cells' flexibility and results in a risk of various...

or Tay-Sachs disease

Tay-Sachs disease

Tay–Sachs disease is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder...

, which in their heterozygote

Zygosity

Zygosity refers to the similarity of alleles for a trait in an organism. If both alleles are the same, the organism is homozygous for the trait. If both alleles are different, the organism is heterozygous for that trait...

form may offer an advantage against, respectively, malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

. Although some birth defects are uniformly lethal, disabled persons can succeed in life. Many of the conditions early eugenicists identified as inheritable (pellagra

Pellagra

Pellagra is a vitamin deficiency disease most commonly caused by a chronic lack of niacin in the diet. It can be caused by decreased intake of niacin or tryptophan, and possibly by excessive intake of leucine. It may also result from alterations in protein metabolism in disorders such as carcinoid...

is one such example) are currently considered to be at least partially, if not wholly, attributed to environmental conditions. Similar concerns have been raised when a prenatal diagnosis

Prenatal diagnosis

Prenatal diagnosis or prenatal screening is testing for diseases or conditions in a fetus or embryo before it is born. The aim is to detect birth defects such as neural tube defects, Down syndrome, chromosome abnormalities, genetic diseases and other conditions, such as spina bifida, cleft palate,...

of a congenital disorder

Congenital disorder

A congenital disorder, or congenital disease, is a condition existing at birth and often before birth, or that develops during the first month of life , regardless of causation...

leads to abortion

Abortion

Abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy by the removal or expulsion from the uterus of a fetus or embryo prior to viability. An abortion can occur spontaneously, in which case it is usually called a miscarriage, or it can be purposely induced...

(see also preimplantation genetic diagnosis

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis

In medicine and genetics pre-implantation genetic diagnosis refers to procedures that are performed on embryos prior to implantation, sometimes even on oocytes prior to fertilization. PGD is considered another way to prenatal diagnosis...

).

Eugenic policies have been conceptually divided into two categories. Positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged. Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, in vitro fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning. Negative eugenics is aimed at lowering fertility among the genetically disadvantaged. This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning. Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive. Abortion by fit

Fitness (biology)

Fitness is a central idea in evolutionary theory. It can be defined either with respect to a genotype or to a phenotype in a given environment...

women was illegal in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and in the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

during Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's reign.

During the 20th century, many countries enacted various eugenics policies and programs, including:

genetic screening, birth control

Birth control

Birth control is an umbrella term for several techniques and methods used to prevent fertilization or to interrupt pregnancy at various stages. Birth control techniques and methods include contraception , contragestion and abortion...

, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

and segregation of the mentally ill from the rest of the population), compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization also known as forced sterilization programs are government policies which attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization...

, forced abortions or forced pregnancies and genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

. Most of these policies were later regarded as coercive and/or restrictive, and now few jurisdictions implement policies that are explicitly labeled as eugenic or unequivocally eugenic in substance. However, some private organizations assist people in genetic counseling

Genetic counseling

Genetic counseling or traveling is the process by which patients or relatives, at risk of an inherited disorder, are advised of the consequences and nature of the disorder, the probability of developing or transmitting it, and the options open to them in management and family planning...

, and reprogenetics

Reprogenetics

Reprogenetics is a term referring to the merging of reproductive and genetic technologies expected to happen in the near future as techniques like germinal choice technology become more available and more powerful. The term was coined by Lee M...

may be considered as a form of non-state-enforced liberal eugenics.

Implementation methods

There are three main ways by which the methods of eugenics can be applied. One is mandatory eugenics or authoritarian eugenics, in which the government mandates a eugenics program. Policies and/or legislation are often seen as being coercive and restrictive. Another is promotional voluntary eugenics, in which eugenics is voluntarily practiced and promoted to the general population, but not officially mandated. This is a form of non-state enforced eugenics, using a liberal or democratic approach, which can mostly be seen in the 1900s. The third is private eugenics, which is practiced voluntarily by individuals and groups, but not promoted to the general population.Pre-Galtonian philosophies

The philosophy was most famously expounded by PlatoPlato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, who believed human reproduction should be monitored and controlled by the state. However, Plato understood this form of government control would not be readily accepted, and proposed the truth be concealed from the public via a fixed lottery. Mates, in Plato's Republic, would be chosen by a "marriage number" in which the quality of the individual would be quantitatively analyzed, and persons of high numbers would be allowed to procreate with other persons of high numbers. In theory, this would lead to predictable results and the improvement of the human race. However, Plato acknowledged the failure of the "marriage number" since "gold soul" persons could still produce "bronze soul" children. Plato's ideas may have been one of the earliest attempts to mathematically analyze genetic inheritance, which was not perfected until the development of Mendel

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel was an Austrian scientist and Augustinian friar who gained posthumous fame as the founder of the new science of genetics. Mendel demonstrated that the inheritance of certain traits in pea plants follows particular patterns, now referred to as the laws of Mendelian inheritance...

ian genetics and the mapping of the human genome

Human genome

The human genome is the genome of Homo sapiens, which is stored on 23 chromosome pairs plus the small mitochondrial DNA. 22 of the 23 chromosomes are autosomal chromosome pairs, while the remaining pair is sex-determining...

.

Other ancient civilizations, such as Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

, Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

and Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

, practiced infanticide

Infanticide

Infanticide or infant homicide is the killing of a human infant. Neonaticide, a killing within 24 hours of a baby's birth, is most commonly done by the mother.In many past societies, certain forms of infanticide were considered permissible...

through exposure as a form of phenotypic selection. In Sparta, newborns were inspected by the city's elders, who decided the fate of the infant. If the child was deemed incapable of living, it was usually exposed in the Apothetae near the Taygetus

Taygetus

Mount Taygetus, Taugetus, or Taigetus is a mountain range in the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece. The name is one of the oldest recorded in Europe, appearing in the Odyssey. In classical mythology, it was associated with the nymph Taygete...

mountain. It was more common for boys than girls to be killed this way in Sparta.

Trials for babies included bathing them in wine and exposing them to the elements. To Sparta, this would ensure only the strongest survived and procreated. Adolf Hitler considered Sparta to be the first "Völkisch

Völkisch movement

The volkisch movement is the German interpretation of the populist movement, with a romantic focus on folklore and the "organic"...

State", and much like Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Haeckel

The "European War" became known as "The Great War", and it was not until 1920, in the book "The First World War 1914-1918" by Charles à Court Repington, that the term "First World War" was used as the official name for the conflict.-Research:...

before him, praised Sparta for its selective infanticide policy, though the Nazis believed the children were killed outright and not exposed.

The Twelve Tables of Roman Law

Twelve Tables

The Law of the Twelve Tables was the ancient legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. The Law of the Twelve Tables formed the centrepiece of the constitution of the Roman Republic and the core of the mos maiorum...

, established early in the formation of the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

, stated in the fourth table that deformed children must be put to death. In addition, patriarchs in Roman society were given the right to "discard" infants at their discretion. This was often done by drowning undesired newborns in the Tiber River. The practice of open infanticide in the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

did not subside until its Christianization

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

.

Galton's theory

Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton /ˈfrɑːnsɪs ˈgɔːltn̩/ FRS , cousin of Douglas Strutt Galton, half-cousin of Charles Darwin, was an English Victorian polymath: anthropologist, eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, psychometrician, and statistician...

systematized these ideas and practices according to new knowledge about the evolution of man and animals provided by the theory of his half-cousin Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

during the 1860s and 1870s. After reading Darwin's Origin of Species, Galton built upon Darwin's ideas whereby the mechanisms of natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

were potentially thwarted by human civilization

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

. He reasoned that, since many human societies sought to protect the underprivileged and weak, those societies were at odds with the natural selection responsible for extinction of the weakest; and only by changing these social policies could society be saved from a "reversion towards mediocrity", a phrase he first coined in statistics and which later changed to the now common "regression towards the mean".

Galton first sketched out his theory in the 1865 article "Hereditary Talent and Character", then elaborated further in his 1869 book Hereditary Genius. He began by studying the way in which human intellectual, moral, and personality traits tended to run in families. Galton's basic argument was "genius" and "talent" were hereditary traits in humans

Inheritance of intelligence

The study of the heritability of IQ investigates the relative importance of genetics and environment for variation in intelligence quotient in a population...

(although neither he nor Darwin yet had a working model of this type of heredity). He concluded since one could use artificial selection

Artificial selection

Artificial selection describes intentional breeding for certain traits, or combination of traits. The term was utilized by Charles Darwin in contrast to natural selection, in which the differential reproduction of organisms with certain traits is attributed to improved survival or reproductive...

to exaggerate traits in other animals, one could expect similar results when applying such models to humans. As he wrote in the introduction to Hereditary Genius:

- I propose to show in this book that a man's natural abilities are derived by inheritance, under exactly the same limitations as are the form and physical features of the whole organic world. Consequently, as it is easy, notwithstanding those limitations, to obtain by careful selection a permanent breed of dogs or horses gifted with peculiar powers of running, or of doing anything else, so it would be quite practicable to produce a highly-gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations.

Galton claimed that the less intelligent were more fertile than the more intelligent of his time. Galton did not propose any selection methods; rather, he hoped a solution would be found if social mores

Mores

Mores, in sociology, are any given society's particular norms, virtues, or values. The word mores is a plurale tantum term borrowed from Latin, which has been used in the English language since the 1890s....

changed in a way that encouraged people to see the importance of breeding. He first used the word eugenic in his 1883 Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, a book in which he meant "to touch on various topics more or less connected with that of the cultivation of race, or, as we might call it, with 'eugenic' questions". He included a footnote to the word "eugenic" which read:

- That is, with questions bearing on what is termed in Greek, eugenes namely, good in stock, hereditary endowed with noble qualities. This, and the allied words, eugeneia, etc., are equally applicable to men, brutes, and plants. We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea; it is at least a neater word and a more generalized one than viticulture which I once ventured to use.

In 1904 he clarified his definition of eugenics as "the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage".

Galton's formulation of eugenics was based on a strong statistical

Statistics

Statistics is the study of the collection, organization, analysis, and interpretation of data. It deals with all aspects of this, including the planning of data collection in terms of the design of surveys and experiments....

approach, influenced heavily by Adolphe Quetelet

Adolphe Quetelet

Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet was a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician and sociologist. He founded and directed the Brussels Observatory and was influential in introducing statistical methods to the social sciences...

's "social physics". Unlike Quetelet, however, Galton did not exalt the "average man" but decried him as mediocre. Galton and his statistical heir Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson FRS was an influential English mathematician who has been credited for establishing the disciplineof mathematical statistics....

developed what was called the biometrical

Biometrics

Biometrics As Jain & Ross point out, "the term biometric authentication is perhaps more appropriate than biometrics since the latter has been historically used in the field of statistics to refer to the analysis of biological data [36]" . consists of methods...

approach to eugenics, which developed new and complex statistical models (later exported to wholly different fields) to describe the heredity of traits. However, with the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel was an Austrian scientist and Augustinian friar who gained posthumous fame as the founder of the new science of genetics. Mendel demonstrated that the inheritance of certain traits in pea plants follows particular patterns, now referred to as the laws of Mendelian inheritance...

's hereditary laws, two separate camps of eugenics advocates emerged. One was made up of statisticians, the other of biologists. Statisticians thought the biologists had exceptionally crude mathematical models, while biologists thought the statisticians knew little about biology.

Eugenics eventually referred to human selective reproduction with an intent to create children with desirable traits, generally through the approach of influencing differential birth rates. These policies were mostly divided into two categories: positive eugenics, the increased reproduction of those seen to have advantageous hereditary traits; and negative eugenics, the discouragement of reproduction by those with hereditary traits perceived as poor. Negative eugenic policies in the past have ranged from attempts at segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

to sterilization

Compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization also known as forced sterilization programs are government policies which attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization...

and even genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

. Positive eugenic policies have typically taken the form of awards or bonuses for "fit" parents who have another child. Relatively innocuous practices like marriage counseling had early links with eugenic ideology. Eugenics is superficially related to what would later be known as Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is a term commonly used for theories of society that emerged in England and the United States in the 1870s, seeking to apply the principles of Darwinian evolution to sociology and politics...

. While both claimed intelligence was hereditary, eugenics asserted new policies were needed to actively change the status quo towards a more "eugenic" state, while the Social Darwinists argued society itself would naturally "check" the problem of "dysgenics

Dysgenics

Dysgenics is the study of factors producing the accumulation and perpetuation of defective or disadvantageous genes and traits in offspring of a particular population or species. Dysgenic mutations have been studied in animals such as the mouse and the fruit fly...

" if no welfare policies were in place (for example, the poor might reproduce more but would have higher mortality rates).

Charles Davenport

Charles DavenportCharles Davenport

Charles Benedict Davenport was a prominent American eugenicist and biologist. He was one of the leaders of the American eugenics movement, which was directly involved in the sterilization of around 60,000 "unfit" Americans and strongly influenced the Holocaust in Europe.- Biography :Davenport was...

, a scientist from the United States, stands out as one of history's leading eugenicists. He took eugenics from a scientific idea to a worldwide movement implemented in many countries. Davenport obtained funding to establish the Biological Experiment Station at Cold Spring Harbor in 1904 and the Eugenics Records Office in 1910, which provided the scientific basis for later Eugenic policies such as enforced sterilization. He became the first President of the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations

International Federation of Eugenics Organizations

The International Federation of Eugenic Organizations was founded in 1925. Most members of this organization united eugenics with racism with political propaganda for the enhancement of the 'white race'." Charles Davenport founded the International Federation of Eugenic Organizations and was its...

(IFEO) in 1925, an organization he was instrumental in building. While Davenport was located at Cold Spring Harbor and received money from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, the organization known as the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) started to become an embarrassment after the well-known debates between Davenport and Franz Boas. Instead, Davenport occupied the same office and the same address at Cold Spring Harbor, but his organization now became known as the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories, which currently retains the archives of the Eugenics Record Office. However, Davenport's racist views were not supported by all geneticists at Cold Spring Harbor, including H. J. Muller, Bentley Glass, and Esther Lederberg

Esther Lederberg

Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg was an American microbiologist and immunologist and pioneer of bacterial genetics...

.

In 1932 Davenport welcomed Ernst Rüdin

Ernst Rüdin

Ernst Rüdin , was a Swiss psychiatrist, geneticist and eugenicist. Rüdin was born in St. Gallen, Switzerland...

, a prominent Swiss eugenicist and race scientist, as his successor in the position of President of the IFEO. Rüdin, director of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Institute for Psychiatry, located in Munich), a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science was a German scientific institution established in 1911. It was implicated in Nazi science, and after the Second World War was wound up and its functions replaced by the Max Planck Society...

, was a co-founder (with his brother-in-law Alfred Ploetz

Alfred Ploetz

Alfred Ploetz was a German physician, biologist, eugenicist known for coining the term racial hygiene and promoting the concept in Germany. Rassenhygiene is a form of eugenics.-Biography:...

) of the German Society for the Racial Hygiene. Other prominent figures in Eugenics who were associated with Davenport included Harry Laughlin (United States), Havelock Ellis

Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis, known as Havelock Ellis , was a British physician and psychologist, writer, and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He was co-author of the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in 1897, and also published works on a variety of sexual practices and...

(United Kingdom), Irving Fischer (United States), Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer was a German professor of medicine, anthropology and eugenics. He was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics between 1927 and 1942...

(Germany), Madison Grant

Madison Grant

Madison Grant was an American lawyer, historian and physical anthropologist, known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist...

(United States), Lucien Howe

Lucien Howe

Lucien Howe was an American physician who spent much of his career as a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Buffalo. In 1876 he was instrumental in the creation of the Buffalo Eye and Ear Infirmary....

(United States), and Margaret Sanger

Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger was an American sex educator, nurse, and birth control activist. Sanger coined the term birth control, opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, and established Planned Parenthood...

(United States, founder of Planned Parenthood).

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, eugenics never received significant state funding, but it was supported by many prominent figures of different political persuasions before World War I, including: LiberalLiberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

economists William Beveridge

William Beveridge

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge KCB was a British economist and social reformer. He is best known for his 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services which served as the basis for the post-World War II welfare state put in place by the Labour government elected in 1945.Lord...

and John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA , was a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments...

; Fabian socialists

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist movement, whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist, rather than revolutionary, means. It is best known for its initial ground-breaking work beginning late in the 19th century and continuing up to World...

such as Irish author George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

, H. G. Wells

H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells was an English author, now best known for his work in the science fiction genre. He was also a prolific writer in many other genres, including contemporary novels, history, politics and social commentary, even writing text books and rules for war games...

and Sidney Webb; the future Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

; and Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

such as Arthur Balfour

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, DL was a British Conservative politician and statesman...

. The influential economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA , was a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments...

was a prominent supporter of Eugenics, serving as Director of the British Eugenics Society, and writing that eugenics is "the most important, significant and, I would add, genuine branch of sociology which exists".

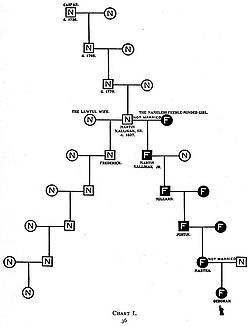

Its emphasis was more upon social class

Social class

Social classes are economic or cultural arrangements of groups in society. Class is an essential object of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, economists, anthropologists and social historians. In the social sciences, social class is often discussed in terms of 'social stratification'...

, rather than race. Indeed, Francis Galton

Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton /ˈfrɑːnsɪs ˈgɔːltn̩/ FRS , cousin of Douglas Strutt Galton, half-cousin of Charles Darwin, was an English Victorian polymath: anthropologist, eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, psychometrician, and statistician...

expressed these views during a lecture in 1901 in which he placed British society into groups. These groupings are shown in the figure and indicate the proportion of society falling into each group and their perceived genetic worth. Galton suggested that negative eugenics (i.e. an attempt to prevent them from bearing offspring) should be applied only to those in the lowest social group (the "Undesirables"), while positive eugenics applied to the higher classes. However, he appreciated the worth of the higher working classes to society and industry.

Sterilisation programmes were never legalised, although some were carried out in private upon the mentally ill by clinicians who were in favour of a more widespread eugenics plan. Indeed, those in support of eugenics shifted their lobbying of Parliament from enforced to voluntary sterilization, in the hope of achieving more legal recognition. But leave for the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

Major A. G. Church, to propose a Private Member's Bill

Private Member's Bill

A member of parliament’s legislative motion, called a private member's bill or a member's bill in some parliaments, is a proposed law introduced by a member of a legislature. In most countries with a parliamentary system, most bills are proposed by the government, not by individual members of the...

in 1931, which would legalise the operation for voluntary sterilization, was rejected by 167 votes to 89. The limited popularity of eugenics in the UK was reflected by the fact that only two universities established courses in this field (University College London

University College London

University College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and the oldest and largest constituent college of the federal University of London...

and Liverpool University). The Galton Institute, affiliated to UCL, was headed by Galton's protégé, Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson FRS was an influential English mathematician who has been credited for establishing the disciplineof mathematical statistics....

.

United States

One of the earliest modern advocates of eugenics (before it was labeled as such) was Alexander Graham BellAlexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell was an eminent scientist, inventor, engineer and innovator who is credited with inventing the first practical telephone....

. In 1881 Bell investigated the rate of deafness on Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard is an island located south of Cape Cod in Massachusetts, known for being an affluent summer colony....

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

. From this he concluded that deafness was hereditary in nature and, through noting that congenitally deaf parents were more likely to produce deaf children, tentatively suggested that couples where both were deaf should not marry, in his lecture Memoir upon the formation of a deaf variety of the human race presented to the National Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

on 13 November 1883. However, it was his hobby of livestock breeding which led to his appointment to biologist David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan, Ph.D., LL.D. was a leading eugenicist, ichthyologist, educator and peace activist. He was president of Indiana University and Stanford University.-Early life and education:...

's Committee on Eugenics, under the auspices of the American Breeders Association. The committee unequivocally extended the principle to man.

Another scientist considered the "father of the American eugenics movement" was Charles Benedict Davenport. In 1904 he secured funding for the The Station for Experimental Evolution, later renamed the Carnegie Department of Genetics. It was also around that time that Davenport became actively involved with the American Breeders' Association (ABA). This let to Davenport's first eugenics text, "The science of human improvement by better breeding", one of the first papers to connect agriculture and human heredity. Davenport later went on to set up a Eugenics Record Office (ERO), collecting hundreds of thousands of medical histories from Americans, which many considered having a racist and anti- immigration agenda. Davenport and his views were supported at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory is a private, non-profit institution with research programs focusing on cancer, neurobiology, plant genetics, genomics and bioinformatics. The Laboratory has a broad educational mission, including the recently established Watson School of Biological Sciences. It...

as late as 1963, when his views began to be de-emphasized (racism was no longer popular). Davenport was ultimately replaced as the head of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1969 by James D. Watson

James D. Watson

James Dewey Watson is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA in 1953 with Francis Crick...

, who himself was removed in 2007 as a consequence of his racist remarks.

As the science continued in the 20th century, researchers interested in familial mental disorders conducted a number of studies to document the heritability of such illnesses as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Their findings were used by the eugenics movement as proof for its cause. State laws were written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to prohibit marriage and force sterilization of the mentally ill in order to prevent the "passing on" of mental illness to the next generation. These laws were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927 and were not abolished until the mid-20th century. All in all, 60,000 Americans were sterilized.

In 1907 Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

became the first of more than thirty states to adopt legislation aimed at compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization also known as forced sterilization programs are government policies which attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization...

of certain individuals. Although the law was overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1921, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a Virginia law

Buck v. Bell

Buck v. Bell, , was the United States Supreme Court ruling that upheld a statute instituting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including the mentally retarded, "for the protection and health of the state." It was largely seen as an endorsement of negative eugenics—the attempt to improve...

allowing for the compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization also known as forced sterilization programs are government policies which attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization...

of patients of state mental institutions in 1927.

Beginning with Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

in 1896, many states enacted marriage laws with eugenic criteria, prohibiting anyone who was "epileptic, imbecile

Imbecile

Imbecile is a term for moderate to severe mental retardation, as well as for a type of criminal. It arises from the Latin word imbecillus, meaning weak, or weak-minded. "Imbecile" was once applied to people with an IQ of 26-50, between "moron" and "idiot" .The term was further refined into mental...

or feeble-minded

Feeble-minded

The term feeble-minded was used from the late nineteenth century in Great Britain, Europe and the United States to refer to a specific type of "mental deficiency". At the time, mental deficiency was an umbrella term, which encompassed all degrees of educational and social deficiency...

" from marrying. In 1898 Charles B. Davenport, a prominent American biologist

Biology

Biology is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living organisms, including their structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, distribution, and taxonomy. Biology is a vast subject containing many subdivisions, topics, and disciplines...

, began as director of a biological research station based in Cold Spring Harbor

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory is a private, non-profit institution with research programs focusing on cancer, neurobiology, plant genetics, genomics and bioinformatics. The Laboratory has a broad educational mission, including the recently established Watson School of Biological Sciences. It...

where he experimented with evolution in plants and animals. In 1904 Davenport received funds from the Carnegie Institution to found the Station for Experimental Evolution. The Eugenics Record Office

Eugenics Record Office

The Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States was a center for eugenics and human heredity research in the first half of the twentieth century. Both its founder, Charles Benedict Davenport, and its director, Harry H...

(ERO) opened in 1910 while Davenport and Harry H. Laughlin

Harry H. Laughlin