Maritime history of England

Encyclopedia

The Maritime history of England involves events including shipping

, port

s, navigation

, and seamen

, as well as marine sciences, exploration, trade, and maritime themes in the arts of England

. Until the advent of air transport and the creation of the Channel Tunnel

, marine transport was the only way of reaching the rest of Europe from England and for this reason, maritime trade and naval power have always had great importance. Prior to the Acts of Union in 1707

, the maritime history of the British Isles was largely dominated by that of England.

and mesolithic

hunter-gatherers may well have reached Great Britain

by sea, at least partly. Separation of the island from Ireland

was about 9000 BC while separation from the continent of Europe

occurred around 6500 BC. English maritime history really starts with the Massaliote Periplus

used by Phoenicia

n traders in Iron Age

Europe. This includes a description of the trade route

to England around 600 BC. It is believed that this trade was in tin and other raw materials. A later periplus

was that of Pytheas

of Marsallia

in "On the Ocean", written about 325 BC. It is clear that in the Iron Age trade between Gaul

and Britain

was routine and that fishermen travelled to Orkney, Shetland and Norway

.

The first vessels used by Britons are presumed to have been raft

s and dugout

canoe

s, though the coracle

, a small single passenger boat is known to have been used at least since the Roman invasion

. Coracles are round or oval in shape, made of a wooden basket-like frame with a hide stretched over it then tarred to provided waterproofing. Being light, it can be carried over a shoulder. Coracles are capable of operating in mere inches of water due to the keel

-less hull

. The early peoples are believed to have used these boats for fishing and travel.

Early Britons used hollowed tree trunks as canoes. Examples of these canoes have been found buried in marshes and mud banks of river, at lengths upwards of two metres. One of these was found at Shapwick

, Somerset

in 1906. It was formed from an oak log and was six metres long. It was probably used to transport people, animals and goods across the Somerset Levels

in the Iron Age.

In 1992 a notable archaeological find, named the "Dover Bronze Age Boat

In 1992 a notable archaeological find, named the "Dover Bronze Age Boat

", was unearthed from beneath what is modern day Dover

, England. It is about 9.5 metres long by 2.3 metres wide and was determined to have been a sea-going vessel. Radiocarbon dating

revealed that the craft dates from approximately 1600 BC and is the oldest known ocean-going boat. The hull was of half oak

logs and side panels also of oak that were stitched on with yew

withies

. Both the straight grained oak and yew bindings are now extinct in England. A reconstruction in 1996 proved that a crew of between four and sixteen paddlers could have easily propelled the boat during Force 4 winds

at upwards of four knots to a maximum of 5 knots (9.8 km/h). The boat could have easily carried a significant amount of cargo and with a strong crew may have been able to traverse up to thirty nautical mile

s in a day.

Remains from a Bronze Age

trading vessel have been found off Salcombe

, Devon

. The finds include palstave

axe

heads, an adze

, a cauldron handle and a gold bracelet. There are also blades of sword

s and rapier

s which are amongst the earliest in the country. Some of the objects originated in north France and are types that are rare in Britain. Evidence of tin trading has been found at Mount Batten

and Bantham

in Devon.

made brief exploratory sea-borne expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BC, these were nearly a disaster because many of the boats were wrecked. The invasion fleet under the emperor Claudius

in AD 43 was a large one, with 40000 men, and landed at Richborough

, Kent

.

Later, part of the Classis Britannica

was based in Britain, the job of which was to control the English Channel

and North Sea

. At this time Britannia suffered raids by Scoti

(from Ireland) and Saxons

, as well as attacks by Picts

from what is now northern Scotland. There was a Roman officer in charge of the "Saxon Shore

" and a series of forts (or perhaps trading posts) was set up along the south and east coast. There also seems to have been a Roman fleet

in the Bristol Channel

, based on archaeological evidence.

Roman trade with Britain was in grain and olive oil from North Africa

, with slaves and lead being exported, while men for the army and administration also came. Later, grain was exported to the continent for the army. There was also trade with Ireland.

as arriving in "three keels" and were soon followed by more. After a dispute over pay, the Saxons revolted and were able to establish Saxon controlled areas in the east and south of England. This apparently involved both Angles

and Jutes

as well as Saxons. This led to much trade across the North Sea from the east coast of Britain. When an important person died their body would be placed inside a ship burial

, such as at Sutton Hoo

where the traces of a boat 27 m long by 4.5 m wide and 1.5 m deep were found, dating to about 625 AD.

In the western areas of Britain trade with the Mediterranean

world continued, many pots and other goods from Byzantium

having been found at sites such as Tintagel

. There was migration from southern England to Brittany

and northern Spain

.

By the 730s a toll was placed on ships using the port of London

, which was re-founded by King Alfred

after its recapture from the Viking

s in 886 AD. Wine, timber and food was imported while salt, cloth, hide, lead and slaves were exported.

From the 9th century, Vikings raided Britain but were also traders. King Alfred raised a navy to counter this and the first sea battle against them is thought to have been fought in 875 AD. The Viking longship

was clinker

built, utilising overlapping wooden strakes and curved stemposts. It was propelled by both oars and sail. There was a steering oar at the back on the right-hand side. The knarr

was a cargo vessel that differed from the longship in that it was larger and relied solely on its square rig

ged sail for propulsion.

in 300-500 ships. The Norman conquest of England

, in the autumn of 1066, which occurred after a seaborne invasion at Hastings

, was unopposed as the English fleet had returned to base. After this the Kings of England were also rulers of much of France so presumably there was much trade across the English Channel. Various wars were fought against the French requiring transport of armies and their support. In 1120 the "White Ship

" was wrecked and the sons of Henry I

drowned, while in 1147 a fleet of 167 ships sailed from Dartmouth

on a crusade to capture Lisbon

from the Moors

. Henry II

invaded Ireland in 1171 and another crusade fleet sailed in 1190.

The Cinque Ports

were a group of harbours, originally five, that were given privileges in exchange for providing ships to the kings of England when required.

The cog

The cog

was a boat design which is believed to have evolved from (or at least have been influenced by) the longship and was in wide use by the 12th century. It too used the clinker method of construction. Ships began to be built with straight stem posts and the rudder

was fixed to the stern post which made a boat easier to steer. To make ships faster, more masts and sails were fitted.

The Hanseatic League

was an alliance of trading guild

s that established and maintained a trade monopoly over the Baltic Sea

and to a certain extent the North Sea in the Late Middle Ages

, starting in the 13th century. Protection for the league was given in England in 1157. Warehouses belonging to the league were set up in eight English ports and one Scottish port. By the 16th century the league imploded and there was a rise of Dutch and English merchants.

In the 14th and 15th centuries seamen's guilds were formed in Bristol

, King's Lynn

, Grimsby

, Hull

, York

and Newcastle

.

in 1480/1 and may have reached Newfoundland.

Before Christopher Columbus

reached mainland America, John Cabot

was employed by the English government to discover new lands. He first sailed from Bristol in the "Matthew

" in 1497. It is not clear where the small fleet went but two likely locations are Nova Scotia

or Newfoundland. They did not find the passage to China

for which they were looking. A second voyage was made in 1498 but 4 of the 5 ships vanished. Some scholars maintain that the name "America" comes from Richard Amerike

, a Bristol merchant and customs officer, who is claimed (on very slender evidence) to have helped finance the Cabots' voyages.

An attempt was made to find a north-east passage to China in 1553 which was unsuccessful but led to the formation of the Muscovy Company

. The Baltic was explored in the 1570s and led to the setting up of English bases in Hanse ports.

In 1578, Sir Francis Drake

In 1578, Sir Francis Drake

, in the course of his circumnavigation of the world, discovered Cape Horn

at the tip of South America

. The sea between this and Antarctica is now known as Drake Passage

.

Richard Hakluyt

was an English writer who is remembered for his efforts in promoting and supporting the settlement of North America

by the English through his works, notably Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America (1582) and The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (1598–1600). The latter also included accounts of voyages to Russia

.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert

established a colony

in Newfoundland in 1583. The first (unsuccessful) British colony in America was set up by Sir Walter Raleigh

at Roanoke

, "Virginia" (now North Carolina

) in 1585. Only one of the 22 ships sailing to Roanoke was lost. An exploratory voyage had been made the year before. When a re-supply voyage was made the colonists had vanished.

As a result of this exploration joint stock companies

were set up, such as the Muscovy (Russia) Company, the Honourable East India Company (1599), the Levant Company

and the Hudson's Bay Company

. Trading "factories" were set up in India

by the British in several ports. Similar companies were set up by the Dutch and Portuguese, which led to rivalries.

The first modern underwater boat proposal was made by the Englishman William Bourne

who designed a prototype submarine

in 1578. Unfortunately for him these ideas never got past the planning stage.

The first successful British colony in America was set up in 1607 at Jamestown

The first successful British colony in America was set up in 1607 at Jamestown

. It languished until a new wave of colonists arrived in the late 17th century and set up commercial agriculture based on tobacco

. The Mayflower

sailed from Plymouth

in 1620. The connection between the American colonies and Britain, with shipping as its cornerstone, would continue to grow unhindered for almost two hundred years.

Several major internal political events hinged on the participation (or lack of participation) of the Navy. First, at the end of the years of the Protectorate, the English Royal Navy brought Charles II

back from his exile in Holland in May 1660, aboard the hastily renamed . Again in 1688, the monarchy changed leadership as Roman Catholic

James II

fled the country; the British fleet made no effort oppose the landing of the Protestant

William of Orange

.

During the 17th century ship experienced significant change. During the early part of the 17th century, English shipbuilders developed sturdy, well masted and defensible ships, that because of the way they were rigged, required a significant crew to man. Though this allowed English ships to travel great distances and survive in hostile waters, they could not remain competitive in the merchant shipping industry, which required ships that had greater stowage but smaller crews. The Dutch had long been building such ships called fluits, which originated towards the end of the 16th century in the Netherlands. These vessels carried little more than half the crew of English merchant ships of comparable stowage because of their longer keel, which allowed for a much larger hold, and fewer sails, which required fewer men to maintain. When the English engaged in several wars with the Dutch and their European allies during the later half of the century, they were exceptionally good at capturing Dutch merchant ships. These ships were soon bought into the English merchant fleet and gradually, out of the popular demand of merchants, English shipbuilders adapted some of the techniques used by Dutch builders to create ships which required smaller crews and had larger stowage.

The 17th century was a period of growth in maritime shipping. Though growth was slow in the first several decades, trade with the Mediterranean, East Indies, and North America Colonies and the participation in the Newfoundland Fishing Industry, witnessed growth throughout the teens, 20s and 30s. Though the Civil War caused some decrease in trade, growth was generally good until the resurgence of the Dutch traders due to a return to peace in their country in 1648, causing a decrease in English trade, especially to the Baltic. Parliament enacted the Navigation Ordinance of 1651 to control the access the Dutch had to English ports, in an attempt to abate the control the Dutch had over trade. After the restoration, the fishing industry, which now was focusing more on the Iceland fishery than Newfoundland which had been taken over by North American fishermen, reached its apex of expansion, however foreign trade continued to significantly expand.

The first modern submersible to be actually built was that of Cornelius Drebbel

, a Dutchman in the service of James I of England

in 1620. Its exact design is not known but improved versions were tested in the River Thames

between 1620 and 1624.

, Kent, fell into disuse. It was revived by Athelstan

and had 400 ships in 937. When the Norman invasion was imminent, King Harold

had trusted his navy to prevent William the Conqueror

's fleet from crossing the Channel. However, not long before the invasion, the fleet was damaged in a storm, driven into harbour and the Normans were able to cross unopposed.

The Norman kings created a naval force in 1155, or adapted a force that already existed, with ships provided by the Cinque Ports. The English Navy began to develop during the 12th and 13th centuries, King John

having a fleet of 500 sails. In the mid 14th century Edward III's

navy had 712 ships. There then followed a period of decline.

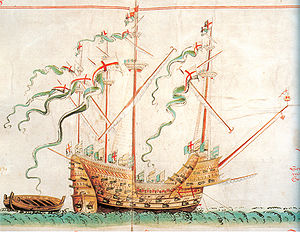

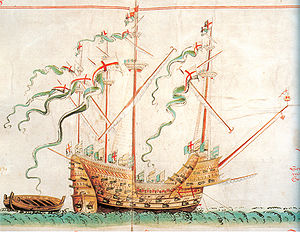

Until the time of Henry VII

Until the time of Henry VII

, the kings of England commandeered and armed merchant ships when there was a need for a navy. Henry started a programme of building specialised warships. By the end of his reign there were five royal ships, two being four-masted carrack

s that were much larger than the usual English merchant ship. By the time that Henry VIII

died in 1547 the navy had been built up to about 40 ships. The invention of gunport meant that guns could be carried much lower in a ship and so more and heavier ones could be carried. In addition a warship carried archers who tried to kill the enemy crew. However the king still needed to borrow some ships to fight sea battles. Henry VIII started new shipbuilding yards at Deptford

and Woolwich Dockyard

. He had two major ships: the Henri Grâce à Dieu and the Mary Rose

, which later sank.

or Charles I

was willing to spend money on the navy. It became too weak to defend the coast from Barbary pirates.

During the Commonwealth of England

, Oliver Cromwell

improved the navy. Admiral Robert Blake

led the English fleet to victory in the First Anglo–Dutch War. After the restoration of the monarchy, Charles II

continued to reform the navy. The king's brother, later James II

, was for many years the Lord High Admiral. Samuel Pepys

became Clerk of the Acts to the King's Ships and reformed the supply service to the Navy. He also instigated examinations for commanders, pursers, surgeons and parsons.

was set up in March 1545 as the King's Council of the Marine. It was responsible for Navy operations and the ship's officers. The First Lord of the Admiralty is a civilian and a member of the Government.

The first Fighting Instructions were issued in 1653 and Sailing Instructions in 1673.

(1337–1453) the French fleet was initial stronger than then English one, but the former was almost completely destroyed at the Battle of Sluys

in 1340. Many other sea battles were fought in this period.

The Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada

was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of Alonso de Guzmán El Bueno, 7th Duke of Medina Sidonia

in 1588. It was sent by King Philip II

of Spain to take the Duke of Parma

's army from the Spanish Netherlands

to a landing in southeast England. The Armada consisted of about 130 warships and converted merchant ships. After forcing its way up the English Channel, being attacked by the English fleet of about 200 vessels, it anchored off the coast at Gravelines

waiting for the army. A fire ship

attack drove the Spanish ships from their safe anchorage. The Armada was blown north up the east coast of England and attempted to return to Spain by sailing around Scotland but many ships were wrecked off Ireland. The Spanish sent a smaller fleet, about 100 ships, the following year but this ran into stormy weather off Cornwall

and was blown back to Spain.

The English sent a fleet of warships to Spain in 1589 led by Sir Francis Drake

. This caused a further weakening of the Spanish fleet but failed to strike a decisive blow. A further raid was made in 1596. The Anglo-Spanish war was concluded by the Treaty of London in 1604. The peace enabled the British to consolidate their hold on Ireland and make a concerted effort to establish colonies in North America.

, Portland

, the Gabbard

and Scheveningen

. In the last of these the Dutch commander Maarten Tromp

was killed but his acting flag captain

kept up fleet morale by not lowering Tromp's standard. In the Second Anglo-Dutch War

(1665-7) Cornelis Tromp

prevented a total catastrophe for the Dutch by taking over fleet command to allow the escape of the greater part of the fleet. The war proved to be a victory for the Dutch, after which the Dutch Navy became the worlds strongest, continuing domination over world trade.

in England started in the many small creeks and rivers around the coast. A 14 m x 4 m Anglo-Saxon

cargo boat (about 900 AD) was found at Graveney

, Kent

. A 13th century ship has been found at Magor Pill on the River Severn

.

Originally open, ships began to have decks around the 12th century. Rudders were fitted on the stern

by 1200 rather than the quarters as previously. In 1416 the king's ship "Anne" had two masts while the "Edward" was built in 1466 with three. Topsail

s were added by 1460, then a spritsail

under a bowsprit

. By 1510 a large warship had 12 sails but usually there were four.

By 1500 there were about 60 types of vessel, mostly cogs with deep hulls. However, from about 1450 "carvels" began to built, based on the Portuguese caravel

. These had non-overlapping planks on a frame. Gunports became used in the mid 16th century. The main type of English galleon

had a low bow

, a sleek hull and a large number of heavy guns. It was both speedy and manoeverable.

In the 16th century the Thames region had become the main shipbuilding area. Royal Dockyards were built and the Honourable East India Company also had shipbuilding facilities there. The East India Company built large well-defended ships which became known as "East Indiamen".

was built in Portsmouth for Henry VIII

between 1509 and 1511. She was the flagship of his navy and was one of the first with gunports. She was rebuilt in 1536. Mary Rose sank on 19 July 1545 off Portsmouth as she was leaving for an engagement with a French fleet that had attacked the English coast. Her remains were discovered in the 19th century but it was not until 1982 that she was raised from the seabed. Many artifacts were recovered and these are now on display in Portsmouth at the Royal Dockyard together with the ship's remains.

s have a commission in the form of a "letter of marque

" authorising the capture of enemy ships, while pirates

do not. Both are robbery at sea or sometimes attacks from the sea onto shore. In 937 Irish pirates sided with Scots, Vikings and Welsh in an invasion of England but were driven back by Athelstan

.

An Englishman called William Maurice was convicted of piracy in 1241 and is the first person known to have been hanged, drawn and quartered

. In the Medieval period piracy was widespread and most pirate attacks came from France, which led to the organisation of the Cinque Ports

.

Until 1536 piracy was a civil law

problem and difficult to prove but it then became a common law

offence. In the 1550s English gentlemen opposed to the reign of Phillip

and Mary

took refuge in France and were active in the English Channel as privateers having gained ships, money and men with letters of marque from Henry II of France

. Six of their vessels were captured off Plymouth in 1556. Some of these men went on to assume positions of authority under Queen Elizabeth, such as Edward Horsey. The Sea Beggars

(Geuzen) were a small group of Protestant noblemen in Queen Elizabeth's time and who were determined to drive the Spanish out of the Netherlands. They were led by William the Silent

.

Queen Elizabeth allowed attacks on the Spanish but tried to prevent war. Gentlemen, merchants and sea captains combined to fit out ships. Perhaps the most famous English privateer was Sir Francis Drake, one of many operating against the Spanish treasure fleet. Thomas Cavendish

was another and obtained valuable charts of the East during a circumnavigation.

Barbary pirates came from North Africa to attack shipping. In 1621 an expedition to North Africa was made against the Barbary pirates. In 1655 Blake routed them and started a campaign against them in the Caribbean.

Sir Henry Morgan

, Captain William Kidd

and Edward Teach (Blackbeard)

were just three of the many English pirate leaders who operated in the Atlantic and Caribbean in the 17th century. In 1700 an Act of Parliament was passed to try pirates in Vice Admiral's Courts.

Important people

Shipping

Shipping has multiple meanings. It can be a physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo, by land, air, and sea. It also can describe the movement of objects by ship.Land or "ground" shipping can be by train or by truck...

, port

Port

A port is a location on a coast or shore containing one or more harbors where ships can dock and transfer people or cargo to or from land....

s, navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

, and seamen

Sailor

A sailor, mariner, or seaman is a person who navigates water-borne vessels or assists in their operation, maintenance, or service. The term can apply to professional mariners, military personnel, and recreational sailors as well as a plethora of other uses...

, as well as marine sciences, exploration, trade, and maritime themes in the arts of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. Until the advent of air transport and the creation of the Channel Tunnel

Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel is a undersea rail tunnel linking Folkestone, Kent in the United Kingdom with Coquelles, Pas-de-Calais near Calais in northern France beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. At its lowest point, it is deep...

, marine transport was the only way of reaching the rest of Europe from England and for this reason, maritime trade and naval power have always had great importance. Prior to the Acts of Union in 1707

Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union were two Parliamentary Acts - the Union with Scotland Act passed in 1706 by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act passed in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland - which put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706,...

, the maritime history of the British Isles was largely dominated by that of England.

Ancient times

PaleolithicPaleolithic

The Paleolithic Age, Era or Period, is a prehistoric period of human history distinguished by the development of the most primitive stone tools discovered , and covers roughly 99% of human technological prehistory...

and mesolithic

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

hunter-gatherers may well have reached Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

by sea, at least partly. Separation of the island from Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

was about 9000 BC while separation from the continent of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

occurred around 6500 BC. English maritime history really starts with the Massaliote Periplus

Massaliote Periplus

The Massaliote Periplus or Massaliot Periplus is the name of a now-lost merchants' handbook possibly dating to as early as the 6th century BC describing the sea routes used by traders from Phoenicia and Tartessus in their journeys around Iron Age Europe...

used by Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

n traders in Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

Europe. This includes a description of the trade route

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

to England around 600 BC. It is believed that this trade was in tin and other raw materials. A later periplus

Periplus

Periplus is the Latinization of an ancient Greek word, περίπλους , literally "a sailing-around." Both segments, peri- and -plous, were independently productive: the ancient Greek speaker understood the word in its literal sense; however, it developed a few specialized meanings, one of which became...

was that of Pytheas

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia or Massilia , was a Greek geographer and explorer from the Greek colony, Massalia . He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe at about 325 BC. He travelled around and visited a considerable part of Great Britain...

of Marsallia

Marseille

Marseille , known in antiquity as Massalia , is the second largest city in France, after Paris, with a population of 852,395 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Marseille extends beyond the city limits with a population of over 1,420,000 on an area of...

in "On the Ocean", written about 325 BC. It is clear that in the Iron Age trade between Gaul

Gaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

and Britain

British Iron Age

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron-Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric Ireland, and which had an independent Iron Age culture of...

was routine and that fishermen travelled to Orkney, Shetland and Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

.

The first vessels used by Britons are presumed to have been raft

Raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is the most basic of boat design, characterized by the absence of a hull...

s and dugout

Dugout (boat)

A dugout or dugout canoe is a boat made from a hollowed tree trunk. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. Monoxylon is Greek -- mono- + ξύλον xylon -- and is mostly used in classic Greek texts. In Germany they are called einbaum )...

canoe

Canoe

A canoe or Canadian canoe is a small narrow boat, typically human-powered, though it may also be powered by sails or small electric or gas motors. Canoes are usually pointed at both bow and stern and are normally open on top, but can be decked over A canoe (North American English) or Canadian...

s, though the coracle

Coracle

The coracle is a small, lightweight boat of the sort traditionally used in Wales but also in parts of Western and South Western England, Ireland , and Scotland ; the word is also used of similar boats found in India, Vietnam, Iraq and Tibet...

, a small single passenger boat is known to have been used at least since the Roman invasion

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

. Coracles are round or oval in shape, made of a wooden basket-like frame with a hide stretched over it then tarred to provided waterproofing. Being light, it can be carried over a shoulder. Coracles are capable of operating in mere inches of water due to the keel

Keel

In boats and ships, keel can refer to either of two parts: a structural element, or a hydrodynamic element. These parts overlap. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in construction of a ship, in British and American shipbuilding traditions the construction is dated from this event...

-less hull

Hull (watercraft)

A hull is the watertight body of a ship or boat. Above the hull is the superstructure and/or deckhouse, where present. The line where the hull meets the water surface is called the waterline.The structure of the hull varies depending on the vessel type...

. The early peoples are believed to have used these boats for fishing and travel.

Early Britons used hollowed tree trunks as canoes. Examples of these canoes have been found buried in marshes and mud banks of river, at lengths upwards of two metres. One of these was found at Shapwick

Shapwick, Somerset

Shapwick is a village on the Somerset Levels, in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, England. It is situated to the west of Glastonbury.-History:Shapwick is the site of one end of the Sweet Track, an ancient causeway dating from the 39th century BC....

, Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

in 1906. It was formed from an oak log and was six metres long. It was probably used to transport people, animals and goods across the Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

in the Iron Age.

Dover Bronze Age Boat

Dover Bronze Age boat is one of the few Bronze Age boats to be found in Britain. It dates to 1575-1520BC. The boat was made using oak planks sewn together with yew lashings. This technique has a long tradition of use in British prehistory; the oldest known examples are from Ferriby in east Yorkshire...

", was unearthed from beneath what is modern day Dover

Dover

Dover is a town and major ferry port in the home county of Kent, in South East England. It faces France across the narrowest part of the English Channel, and lies south-east of Canterbury; east of Kent's administrative capital Maidstone; and north-east along the coastline from Dungeness and Hastings...

, England. It is about 9.5 metres long by 2.3 metres wide and was determined to have been a sea-going vessel. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating is a radiometric dating method that uses the naturally occurring radioisotope carbon-14 to estimate the age of carbon-bearing materials up to about 58,000 to 62,000 years. Raw, i.e. uncalibrated, radiocarbon ages are usually reported in radiocarbon years "Before Present" ,...

revealed that the craft dates from approximately 1600 BC and is the oldest known ocean-going boat. The hull was of half oak

Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus Quercus , of which about 600 species exist. "Oak" may also appear in the names of species in related genera, notably Lithocarpus...

logs and side panels also of oak that were stitched on with yew

Taxus baccata

Taxus baccata is a conifer native to western, central and southern Europe, northwest Africa, northern Iran and southwest Asia. It is the tree originally known as yew, though with other related trees becoming known, it may be now known as the English yew, or European yew.-Description:It is a small-...

withies

Withy

Withy or withe is a strong flexible willow stem that is typically used in thatching and for gardening. An advantage of using this type of material is said to be a greater resistance to woodworm....

. Both the straight grained oak and yew bindings are now extinct in England. A reconstruction in 1996 proved that a crew of between four and sixteen paddlers could have easily propelled the boat during Force 4 winds

Beaufort scale

The Beaufort Scale is an empirical measure that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea or on land. Its full name is the Beaufort Wind Force Scale.-History:...

at upwards of four knots to a maximum of 5 knots (9.8 km/h). The boat could have easily carried a significant amount of cargo and with a strong crew may have been able to traverse up to thirty nautical mile

Nautical mile

The nautical mile is a unit of length that is about one minute of arc of latitude along any meridian, but is approximately one minute of arc of longitude only at the equator...

s in a day.

Remains from a Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

trading vessel have been found off Salcombe

Salcombe

Salcombe is a town in the South Hams district of Devon, south west England. The town is close to the mouth of the Kingsbridge Estuary, built mostly on the steep west side of the estuary and lies within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty...

, Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

. The finds include palstave

Palstave

A Palstave is a type of early bronze axe. It was common in the mid Bronze Age in north, western and south-western Europe. In the technical sense, although precise definitions differ, an axe is generally deemed to be a palstave if it is hafted by means of a forked wooden handle kept in place with...

axe

Axe

The axe, or ax, is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood; to harvest timber; as a weapon; and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol...

heads, an adze

Adze

An adze is a tool used for smoothing or carving rough-cut wood in hand woodworking. Generally, the user stands astride a board or log and swings the adze downwards towards his feet, chipping off pieces of wood, moving backwards as they go and leaving a relatively smooth surface behind...

, a cauldron handle and a gold bracelet. There are also blades of sword

Sword

A sword is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. The precise definition of the term varies with the historical epoch or the geographical region under consideration...

s and rapier

Rapier

A rapier is a slender, sharply pointed sword, ideally used for thrusting attacks, used mainly in Early Modern Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries.-Description:...

s which are amongst the earliest in the country. Some of the objects originated in north France and are types that are rare in Britain. Evidence of tin trading has been found at Mount Batten

Mount Batten

Mount Batten is a 24-metre-tall outcrop of rock on a 600-metre peninsula in Plymouth Sound, Devon, England.After some redevelopment which started with the area coming under the control of the Plymouth Development Corporation for five years from 1993, the peninsula now has a marina and centre for...

and Bantham

Bantham

Bantham is a village in Devon, England. It is in the South Hams district and lies on the estuary of the River Avon quarter of a mile from the sea at Bigbury Bay. It has a beach which is used by surfers....

in Devon.

Roman Period

Although Julius CaesarJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

made brief exploratory sea-borne expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BC, these were nearly a disaster because many of the boats were wrecked. The invasion fleet under the emperor Claudius

Claudius

Claudius , was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul and was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside Italy...

in AD 43 was a large one, with 40000 men, and landed at Richborough

Richborough

Richborough is a settlement north of Sandwich on the east coast of the county of Kent, England. Richborough lies close to the Isle of Thanet....

, Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

.

Later, part of the Classis Britannica

Classis Britannica

The Classis Britannica was a provincial naval fleet of the navy of ancient Rome. Its purpose was to control the English Channel and the waters around the Roman province of Britannia...

was based in Britain, the job of which was to control the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

and North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

. At this time Britannia suffered raids by Scoti

Scoti

Scoti or Scotti was the generic name used by the Romans to describe those who sailed from Ireland to conduct raids on Roman Britain. It was thus synonymous with the modern term Gaels...

(from Ireland) and Saxons

Saxons

The Saxons were a confederation of Germanic tribes originating on the North German plain. The Saxons earliest known area of settlement is Northern Albingia, an area approximately that of modern Holstein...

, as well as attacks by Picts

Picts

The Picts were a group of Late Iron Age and Early Mediaeval people living in what is now eastern and northern Scotland. There is an association with the distribution of brochs, place names beginning 'Pit-', for instance Pitlochry, and Pictish stones. They are recorded from before the Roman conquest...

from what is now northern Scotland. There was a Roman officer in charge of the "Saxon Shore

Saxon Shore

Saxon Shore could refer to one of the following:* Saxon Shore, a military command of the Late Roman Empire, encompassing southern Britain and the coasts of northern France...

" and a series of forts (or perhaps trading posts) was set up along the south and east coast. There also seems to have been a Roman fleet

Roman Navy

The Roman Navy comprised the naval forces of the Ancient Roman state. Although the navy was instrumental in the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean basin, it never enjoyed the prestige of the Roman legions...

in the Bristol Channel

Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales from Devon and Somerset in South West England. It extends from the lower estuary of the River Severn to the North Atlantic Ocean...

, based on archaeological evidence.

Roman trade with Britain was in grain and olive oil from North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

, with slaves and lead being exported, while men for the army and administration also came. Later, grain was exported to the continent for the army. There was also trade with Ireland.

Early Middle Ages

After the end of Roman control of Britain in the early 5th century, "Saxon" mercenaries were recruited by British kings. The first are described by GildasGildas

Gildas was a 6th-century British cleric. He is one of the best-documented figures of the Christian church in the British Isles during this period. His renowned learning and literary style earned him the designation Gildas Sapiens...

as arriving in "three keels" and were soon followed by more. After a dispute over pay, the Saxons revolted and were able to establish Saxon controlled areas in the east and south of England. This apparently involved both Angles

Angles

The Angles is a modern English term for a Germanic people who took their name from the ancestral cultural region of Angeln, a district located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany...

and Jutes

Jutes

The Jutes, Iuti, or Iutæ were a Germanic people who, according to Bede, were one of the three most powerful Germanic peoples of their time, the other two being the Saxons and the Angles...

as well as Saxons. This led to much trade across the North Sea from the east coast of Britain. When an important person died their body would be placed inside a ship burial

Ship burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as a container for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave...

, such as at Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo, near to Woodbridge, in the English county of Suffolk, is the site of two 6th and early 7th century cemeteries. One contained an undisturbed ship burial including a wealth of Anglo-Saxon artefacts of outstanding art-historical and archaeological significance, now held in the British...

where the traces of a boat 27 m long by 4.5 m wide and 1.5 m deep were found, dating to about 625 AD.

In the western areas of Britain trade with the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

world continued, many pots and other goods from Byzantium

Byzantium

Byzantium was an ancient Greek city, founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king Byzas . The name Byzantium is a Latinization of the original name Byzantion...

having been found at sites such as Tintagel

Tintagel

Tintagel is a civil parish and village situated on the Atlantic coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. The population of the parish is 1,820 people, and the area of the parish is ....

. There was migration from southern England to Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

and northern Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

.

By the 730s a toll was placed on ships using the port of London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, which was re-founded by King Alfred

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

after its recapture from the Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

s in 886 AD. Wine, timber and food was imported while salt, cloth, hide, lead and slaves were exported.

From the 9th century, Vikings raided Britain but were also traders. King Alfred raised a navy to counter this and the first sea battle against them is thought to have been fought in 875 AD. The Viking longship

Longship

Longships were sea vessels made and used by the Vikings from the Nordic countries for trade, commerce, exploration, and warfare during the Viking Age. The longship’s design evolved over many years, beginning in the Stone Age with the invention of the umiak and continuing up to the 9th century with...

was clinker

Clinker (boat building)

Clinker building is a method of constructing hulls of boats and ships by fixing wooden planks and, in the early nineteenth century, iron plates to each other so that the planks overlap along their edges. The overlapping joint is called a land. In any but a very small boat, the individual planks...

built, utilising overlapping wooden strakes and curved stemposts. It was propelled by both oars and sail. There was a steering oar at the back on the right-hand side. The knarr

Knarr

The Knarr is a Bermuda rigged, long keeled, sailing yacht designed in 1943 by Norwegian Erling L. Kristofersen. Knarrer were traditionally built in wood, with the hull upside down on a fixed frame, then attaching the iron keel after the hull was completed. The hull planks were manufactured with...

was a cargo vessel that differed from the longship in that it was larger and relied solely on its square rig

Square rig

Square rig is a generic type of sail and rigging arrangement in which the primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spars which are perpendicular, or square, to the keel of the vessel and to the masts. These spars are called yards and their tips, beyond the last stay, are called the yardarms...

ged sail for propulsion.

Later Middle Ages

In the spring of 1066 northern Britain was attacked by King Harald of Norway and Tostig GodwinsonTostig Godwinson

Tostig Godwinson was an Anglo-Saxon Earl of Northumbria and brother of King Harold Godwinson, the last crowned english King of England.-Early life:...

in 300-500 ships. The Norman conquest of England

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

, in the autumn of 1066, which occurred after a seaborne invasion at Hastings

Hastings

Hastings is a town and borough in the county of East Sussex on the south coast of England. The town is located east of the county town of Lewes and south east of London, and has an estimated population of 86,900....

, was unopposed as the English fleet had returned to base. After this the Kings of England were also rulers of much of France so presumably there was much trade across the English Channel. Various wars were fought against the French requiring transport of armies and their support. In 1120 the "White Ship

White Ship

The White Ship was a vessel that sank in the English Channel near the Normandy coast off Barfleur, on 25 November 1120. Only one of those aboard survived. Those who drowned included William Adelin, the only surviving legitimate son and heir of King Henry I of England...

" was wrecked and the sons of Henry I

Henry I of England

Henry I was the fourth son of William I of England. He succeeded his elder brother William II as King of England in 1100 and defeated his eldest brother, Robert Curthose, to become Duke of Normandy in 1106...

drowned, while in 1147 a fleet of 167 ships sailed from Dartmouth

Dartmouth, Devon

Dartmouth is a town and civil parish in the English county of Devon. It is a tourist destination set on the banks of the estuary of the River Dart, which is a long narrow tidal ria that runs inland as far as Totnes...

on a crusade to capture Lisbon

Lisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

from the Moors

Moors

The description Moors has referred to several historic and modern populations of the Maghreb region who are predominately of Berber and Arab descent. They came to conquer and rule the Iberian Peninsula for nearly 800 years. At that time they were Muslim, although earlier the people had followed...

. Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

invaded Ireland in 1171 and another crusade fleet sailed in 1190.

The Cinque Ports

Cinque Ports

The Confederation of Cinque Ports is a historic series of coastal towns in Kent and Sussex. It was originally formed for military and trade purposes, but is now entirely ceremonial. It lies at the eastern end of the English Channel, where the crossing to the continent is narrowest...

were a group of harbours, originally five, that were given privileges in exchange for providing ships to the kings of England when required.

Cog (ship)

A cog is a type of ship that first appeared in the 10th century, and was widely used from around the 12th century on. Cogs were generally built of oak, which was an abundant timber in the Baltic region of Prussia. This vessel was fitted with a single mast and a square-rigged single sail...

was a boat design which is believed to have evolved from (or at least have been influenced by) the longship and was in wide use by the 12th century. It too used the clinker method of construction. Ships began to be built with straight stem posts and the rudder

Rudder

A rudder is a device used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft or other conveyance that moves through a medium . On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw and p-factor and is not the primary control used to turn the airplane...

was fixed to the stern post which made a boat easier to steer. To make ships faster, more masts and sails were fitted.

The Hanseatic League

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was an economic alliance of trading cities and their merchant guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe...

was an alliance of trading guild

Guild

A guild is an association of craftsmen in a particular trade. The earliest types of guild were formed as confraternities of workers. They were organized in a manner something between a trade union, a cartel, and a secret society...

s that established and maintained a trade monopoly over the Baltic Sea

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

and to a certain extent the North Sea in the Late Middle Ages

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages was the period of European history generally comprising the 14th to the 16th century . The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern era ....

, starting in the 13th century. Protection for the league was given in England in 1157. Warehouses belonging to the league were set up in eight English ports and one Scottish port. By the 16th century the league imploded and there was a rise of Dutch and English merchants.

In the 14th and 15th centuries seamen's guilds were formed in Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

, King's Lynn

King's Lynn

King's Lynn is a sea port and market town in the ceremonial county of Norfolk in the East of England. It is situated north of London and west of Norwich. The population of the town is 42,800....

, Grimsby

Grimsby

Grimsby is a seaport on the Humber Estuary in Lincolnshire, England. It has been the administrative centre of the unitary authority area of North East Lincolnshire since 1996...

, Hull

Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull , usually referred to as Hull, is a city and unitary authority area in the ceremonial county of the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It stands on the River Hull at its junction with the Humber estuary, 25 miles inland from the North Sea. Hull has a resident population of...

, York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

and Newcastle

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

.

Age of Exploration

From the early 15th century, continuing into the 17th century, English ships travelled around the world searching for new trading partners and establishing new trading routes. In the process new peoples were encountered and lands were mapped that were previously unknown to the English. Bristol ships were venturing into the Atlantic OceanAtlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

in 1480/1 and may have reached Newfoundland.

Before Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

reached mainland America, John Cabot

John Cabot

John Cabot was an Italian navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America is commonly held to have been the first European encounter with the continent of North America since the Norse Vikings in the eleventh century...

was employed by the English government to discover new lands. He first sailed from Bristol in the "Matthew

Matthew (ship)

The Matthew was a caravel sailed by John Cabot in 1497 from Bristol to North America, presumably Newfoundland. After a voyage which had got no further than Iceland, Cabot left again with only one vessel, the Matthew, a small ship , but fast and able. The crew consisted of only 18 people. The...

" in 1497. It is not clear where the small fleet went but two likely locations are Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

or Newfoundland. They did not find the passage to China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

for which they were looking. A second voyage was made in 1498 but 4 of the 5 ships vanished. Some scholars maintain that the name "America" comes from Richard Amerike

Richard Amerike

Richard ap Meryk, Anglicised to Richard Amerike was a wealthy English merchant, royal customs officer and sheriff, of Welsh descent. He was the principal owner of the Matthew, the ship sailed by John Cabot during his voyage of exploration to North America in 1497...

, a Bristol merchant and customs officer, who is claimed (on very slender evidence) to have helped finance the Cabots' voyages.

An attempt was made to find a north-east passage to China in 1553 which was unsuccessful but led to the formation of the Muscovy Company

Muscovy Company

The Muscovy Company , was a trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint stock company, the precursor of the type of business that would soon flourish in England, and became closely associated with such famous names as Henry Hudson and William Baffin...

. The Baltic was explored in the 1570s and led to the setting up of English bases in Hanse ports.

Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake, Vice Admiral was an English sea captain, privateer, navigator, slaver, and politician of the Elizabethan era. Elizabeth I of England awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581. He was second-in-command of the English fleet against the Spanish Armada in 1588. He also carried out the...

, in the course of his circumnavigation of the world, discovered Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island...

at the tip of South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

. The sea between this and Antarctica is now known as Drake Passage

Drake Passage

The Drake Passage or Mar de Hoces—Sea of Hoces—is the body of water between the southern tip of South America at Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica...

.

Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt was an English writer. He is principally remembered for his efforts in promoting and supporting the settlement of North America by the English through his works, notably Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America and The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and...

was an English writer who is remembered for his efforts in promoting and supporting the settlement of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

by the English through his works, notably Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America (1582) and The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (1598–1600). The latter also included accounts of voyages to Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert

Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert of Devon in England was a half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh. Adventurer, explorer, member of parliament, and soldier, he served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth and was a pioneer of English colonization in North America and the Plantations of Ireland.-Early life:Gilbert...

established a colony

Colony

In politics and history, a colony is a territory under the immediate political control of a state. For colonies in antiquity, city-states would often found their own colonies. Some colonies were historically countries, while others were territories without definite statehood from their inception....

in Newfoundland in 1583. The first (unsuccessful) British colony in America was set up by Sir Walter Raleigh

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English aristocrat, writer, poet, soldier, courtier, spy, and explorer. He is also well known for popularising tobacco in England....

at Roanoke

Roanoke Colony

The Roanoke Colony on Roanoke Island in Dare County, present-day North Carolina, United States was a late 16th-century attempt to establish a permanent English settlement in what later became the Virginia Colony. The enterprise was financed and organized by Sir Walter Raleigh and carried out by...

, "Virginia" (now North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

) in 1585. Only one of the 22 ships sailing to Roanoke was lost. An exploratory voyage had been made the year before. When a re-supply voyage was made the colonists had vanished.

As a result of this exploration joint stock companies

Joint stock company

A joint-stock company is a type of corporation or partnership involving two or more individuals that own shares of stock in the company...

were set up, such as the Muscovy (Russia) Company, the Honourable East India Company (1599), the Levant Company

Levant Company

The Levant Company, or Turkey Company, was an English chartered company formed in 1581, to regulate English trade with Turkey and the Levant...

and the Hudson's Bay Company

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company , abbreviated HBC, or "The Bay" is the oldest commercial corporation in North America and one of the oldest in the world. A fur trading business for much of its existence, today Hudson's Bay Company owns and operates retail stores throughout Canada...

. Trading "factories" were set up in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

by the British in several ports. Similar companies were set up by the Dutch and Portuguese, which led to rivalries.

The first modern underwater boat proposal was made by the Englishman William Bourne

William Bourne (mathematician)

William Bourne was an English mathematician, innkeeper and former Royal Navy gunner who invented the first navigable submarine and wrote important navigational manuals...

who designed a prototype submarine

Submarine

A submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

in 1578. Unfortunately for him these ideas never got past the planning stage.

Seventeenth century

Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

. It languished until a new wave of colonists arrived in the late 17th century and set up commercial agriculture based on tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

. The Mayflower

Mayflower

The Mayflower was the ship that transported the English Separatists, better known as the Pilgrims, from a site near the Mayflower Steps in Plymouth, England, to Plymouth, Massachusetts, , in 1620...

sailed from Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

in 1620. The connection between the American colonies and Britain, with shipping as its cornerstone, would continue to grow unhindered for almost two hundred years.

Several major internal political events hinged on the participation (or lack of participation) of the Navy. First, at the end of the years of the Protectorate, the English Royal Navy brought Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

back from his exile in Holland in May 1660, aboard the hastily renamed . Again in 1688, the monarchy changed leadership as Roman Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

James II

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

fled the country; the British fleet made no effort oppose the landing of the Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

.

During the 17th century ship experienced significant change. During the early part of the 17th century, English shipbuilders developed sturdy, well masted and defensible ships, that because of the way they were rigged, required a significant crew to man. Though this allowed English ships to travel great distances and survive in hostile waters, they could not remain competitive in the merchant shipping industry, which required ships that had greater stowage but smaller crews. The Dutch had long been building such ships called fluits, which originated towards the end of the 16th century in the Netherlands. These vessels carried little more than half the crew of English merchant ships of comparable stowage because of their longer keel, which allowed for a much larger hold, and fewer sails, which required fewer men to maintain. When the English engaged in several wars with the Dutch and their European allies during the later half of the century, they were exceptionally good at capturing Dutch merchant ships. These ships were soon bought into the English merchant fleet and gradually, out of the popular demand of merchants, English shipbuilders adapted some of the techniques used by Dutch builders to create ships which required smaller crews and had larger stowage.

The 17th century was a period of growth in maritime shipping. Though growth was slow in the first several decades, trade with the Mediterranean, East Indies, and North America Colonies and the participation in the Newfoundland Fishing Industry, witnessed growth throughout the teens, 20s and 30s. Though the Civil War caused some decrease in trade, growth was generally good until the resurgence of the Dutch traders due to a return to peace in their country in 1648, causing a decrease in English trade, especially to the Baltic. Parliament enacted the Navigation Ordinance of 1651 to control the access the Dutch had to English ports, in an attempt to abate the control the Dutch had over trade. After the restoration, the fishing industry, which now was focusing more on the Iceland fishery than Newfoundland which had been taken over by North American fishermen, reached its apex of expansion, however foreign trade continued to significantly expand.

The first modern submersible to be actually built was that of Cornelius Drebbel

Cornelius Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel was the Dutch builder of the first navigable submarine in 1620. Drebbel was an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, optics and chemistry....

, a Dutchman in the service of James I of England

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

in 1620. Its exact design is not known but improved versions were tested in the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

between 1620 and 1624.

Early Navy

England's first known navy was established by Alfred the Great which, despite inflicting a significant defeat on the Vikings in the Wantsum ChannelWantsum Channel

The Wantsum Channel is the name given to a now silted-up watercourse separating the Isle of Thanet and what was the mainland of the English county of Kent...

, Kent, fell into disuse. It was revived by Athelstan

Athelstan of England

Athelstan , called the Glorious, was the King of England from 924 or 925 to 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder, grandson of Alfred the Great and nephew of Æthelflæd of Mercia...

and had 400 ships in 937. When the Norman invasion was imminent, King Harold

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

had trusted his navy to prevent William the Conqueror

William I of England

William I , also known as William the Conqueror , was the first Norman King of England from Christmas 1066 until his death. He was also Duke of Normandy from 3 July 1035 until his death, under the name William II...

's fleet from crossing the Channel. However, not long before the invasion, the fleet was damaged in a storm, driven into harbour and the Normans were able to cross unopposed.

The Norman kings created a naval force in 1155, or adapted a force that already existed, with ships provided by the Cinque Ports. The English Navy began to develop during the 12th and 13th centuries, King John

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

having a fleet of 500 sails. In the mid 14th century Edward III's

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

navy had 712 ships. There then followed a period of decline.

The Tudor navy

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

, the kings of England commandeered and armed merchant ships when there was a need for a navy. Henry started a programme of building specialised warships. By the end of his reign there were five royal ships, two being four-masted carrack

Carrack

A carrack or nau was a three- or four-masted sailing ship developed in 15th century Western Europe for use in the Atlantic Ocean. It had a high rounded stern with large aftcastle, forecastle and bowsprit at the stem. It was first used by the Portuguese , and later by the Spanish, to explore and...