History of Philadelphia

Encyclopedia

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

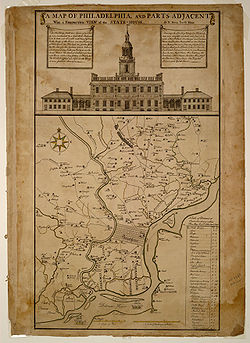

, goes back to 1682, when the city was founded by William Penn

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

.

Before then, the area was inhabited by the Lenape (Delaware)

Lenape

The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the...

Indians

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

and Swedish

New Sweden

New Sweden was a Swedish colony along the Delaware River on the Mid-Atlantic coast of North America from 1638 to 1655. Fort Christina, now in Wilmington, Delaware, was the first settlement. New Sweden included parts of the present-day American states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania....

settlers who arrived in the area in the early 17th century. Philadelphia quickly grew into an important colonial

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

city and during the American Revolution

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

was the site of the First

First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from twelve of the thirteen North American colonies that met on September 5, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, early in the American Revolution. It was called in response to the passage of the Coercive Acts by the...

and Second Continental Congress

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that started meeting on May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon after warfare in the American Revolutionary War had begun. It succeeded the First Continental Congress, which met briefly during 1774,...

es. After the Revolution the city was chosen to be the temporary capital of the United States. At the beginning of the 19th century, the federal and state governments left Philadelphia, but the city remained the cultural and financial center of the country. Philadelphia became one of the first U.S. industrial centers and the city contained a variety of industries, the largest being textile

Textile

A textile or cloth is a flexible woven material consisting of a network of natural or artificial fibres often referred to as thread or yarn. Yarn is produced by spinning raw fibres of wool, flax, cotton, or other material to produce long strands...

s.

After the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

Philadelphia's government was controlled by a corrupt Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

political machine

Political machine

A political machine is a political organization in which an authoritative boss or small group commands the support of a corps of supporters and businesses , who receive rewards for their efforts...

and by the beginning of the 20th Century Philadelphia was described as "corrupt and contented." Various reform efforts slowly changed city government with the most significant in 1950 where a new city charter strengthened the position of mayor

Mayor

In many countries, a Mayor is the highest ranking officer in the municipal government of a town or a large urban city....

and weakened the Philadelphia City Council

Philadelphia City Council

The Philadelphia City Council, the legislative body of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, consists of ten members elected by district and seven members elected at-large. The council president is elected by the members from among their number...

. At the same time Philadelphia moved its support from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

, which has been predominant in local politics for many decades. The city's population began to decline in the 1950s as mostly white and middle class families left for the suburbs. Many of Philadelphia's houses were in poor condition and lacked modernized utilities, and gang

Gang

A gang is a group of people who, through the organization, formation, and establishment of an assemblage, share a common identity. In current usage it typically denotes a criminal organization or else a criminal affiliation. In early usage, the word gang referred to a group of workmen...

and mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

warfare plagued the city.

By the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st, revitalization and gentrification

Gentrification

Gentrification and urban gentrification refer to the changes that result when wealthier people acquire or rent property in low income and working class communities. Urban gentrification is associated with movement. Consequent to gentrification, the average income increases and average family size...

of certain neighborhoods started caused an increase in population as people began to return to the city. Promotions and incentives in the 1990s and the early 21st century have improved the city's image and created a condominium

Condominium

A condominium, or condo, is the form of housing tenure and other real property where a specified part of a piece of real estate is individually owned while use of and access to common facilities in the piece such as hallways, heating system, elevators, exterior areas is executed under legal rights...

boom in Center City

Center City, Philadelphia

Center City, or Downtown Philadelphia includes the central business district and central neighborhoods of the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. As of 2005, its population of over 88,000 made it the third most populous downtown in the United States, after New York City's and Chicago's...

and the surrounding areas.

Founding

Lenape

The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the...

Indians

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

. European colonization of the Delaware River Valley (called the Zuyd, meaning "South" river at the time) began in 1609 when a Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson first entered the river in search of the Northwest Passage

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is a sea route through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways amidst the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans...

. The Valley, including the future location of Philadelphia, became part of the New Netherland

New Netherland

New Netherland, or Nieuw-Nederland in Dutch, was the 17th-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the East Coast of North America. The claimed territories were the lands from the Delmarva Peninsula to extreme southwestern Cape Cod...

claim of the Dutch and Dutch explorer Cornelius Jacobsen Mey

Cornelius Jacobsen Mey

Cornelis Jacobszoon May , was a Dutch explorer, captain and fur trader, and namesake of Cape May, Cape May County, and the city of Cape May, New Jersey, so named first in 1620.-Family:...

(after whom Cape May, New Jersey is named) charted the shoals Delaware Bay in the 1620s. The Dutch built a fort on the west side of the bay at Swanendael

Zwaanendael Colony

Zwaanendael or Swaanendael was a short lived Dutch colonial settlement in Delaware. It was built in 1631. The name is archaic Dutch spelling for "swan valley" or dale...

.

In 1637, Swedish, Dutch and German stockholders formed the New Sweden

New Sweden

New Sweden was a Swedish colony along the Delaware River on the Mid-Atlantic coast of North America from 1638 to 1655. Fort Christina, now in Wilmington, Delaware, was the first settlement. New Sweden included parts of the present-day American states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania....

Company to trade for furs and tobacco in North America. Under the command of Peter Minuit

Peter Minuit

Peter Minuit, Pieter Minuit, Pierre Minuit or Peter Minnewit was a Walloon from Wesel, in present-day North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, then part of the Duchy of Cleves. He was the Director-General of the Dutch colony of New Netherland from 1626 until 1633, and he founded the Swedish colony of...

, the company's first expedition sailed from Sweden late in 1637 in two ships, Kalmar Nyckel

Kalmar Nyckel

The Kalmar Nyckel was a Dutch-built armed merchant ship famed for carrying Finnish and Swedish settlers to North America in 1638 to establish the colony of New Sweden. A replica of the ship was launched at Wilmington, Delaware, in 1997.-History:The Kalmar Nyckel was constructed in about 1625 and...

and Fogel Gri. Minuit had been the governor of the New Netherland

New Netherland

New Netherland, or Nieuw-Nederland in Dutch, was the 17th-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the East Coast of North America. The claimed territories were the lands from the Delmarva Peninsula to extreme southwestern Cape Cod...

from 1626 to 1631. Resenting his dismissal by the Dutch West India Company

Dutch West India Company

Dutch West India Company was a chartered company of Dutch merchants. Among its founding fathers was Willem Usselincx...

he had brought to the new project the knowledge that the Dutch colony had temporarily abandoned its efforts in the Delaware Valley to focus on the Hudson River valley to the north. (The Hudson was known to the Dutch as the Noort, or "North" river relative to "South" of the Delaware.) Minuit and his partners further knew that the Dutch view of colonies held that actual occupation was necessary to secure legal claim. The ships reached Delaware Bay in March 1638, and the settlers began to build a fort at the site of present-day Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington is the largest city in the state of Delaware, United States, and is located at the confluence of the Christina River and Brandywine Creek, near where the Christina flows into the Delaware River. It is the county seat of New Castle County and one of the major cities in the Delaware Valley...

. They named it Fort Christina

Fort Christina

Fort Christina was the first Swedish settlement in North America and the principal settlement of the New Sweden colony...

, in honor of the twelve-year-old Queen Christina

Christina of Sweden

Christina , later adopted the name Christina Alexandra, was Queen regnant of Swedes, Goths and Vandals, Grand Princess of Finland, and Duchess of Ingria, Estonia, Livonia and Karelia, from 1633 to 1654. She was the only surviving legitimate child of King Gustav II Adolph and his wife Maria Eleonora...

of Sweden. It was the first permanent European settlement in the Delaware Valley. Part of this colony eventually included land on the west side of the Delaware River

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river on the Atlantic coast of the United States.A Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson in 1609 first mapped the river. The river was christened the South River in the New Netherland colony that followed, in contrast to the North River, as the Hudson River was then...

from just below the Schuylkill River

Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River is a river in Pennsylvania. It is a designated Pennsylvania Scenic River.The river is about long. Its watershed of about lies entirely within the state of Pennsylvania. The source of its eastern branch is in the Appalachian Mountains at Tuscarora Springs, near Tamaqua in...

.

Johan Björnsson Printz

Johan Björnsson Printz

Johan Björnsson Printz was governor from 1643 until 1653 of the Swedish colony of New Sweden on the Delaware River in North America.-Early Life in Sweden:...

, who had been ennobled, was appointed to be the first royal governor of New Sweden, arriving in the colony on 15 February 1643. Under his ten year rule, the administrative center of New Sweden

New Sweden

New Sweden was a Swedish colony along the Delaware River on the Mid-Atlantic coast of North America from 1638 to 1655. Fort Christina, now in Wilmington, Delaware, was the first settlement. New Sweden included parts of the present-day American states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania....

was moved north to Tinicum Island

Tinicum Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania

Tinicum Township, more popularly known as "Tinicum Island" or "The Island", a census-designated place and township in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 4,353 at the 2000 census. Included within the township's boundaries are the communities of Essington and Lester...

(to the immediate SW of today's Philadelphia), where he built Fort New Gothenburg and his own manor house which he called the Printzhof

The Printzhof

The Printzhof, located in Governor Printz Park in Essington, Pennsylvania, was the home of Johan Björnsson Printz, governor of New Sweden....

.

The first English settlement was around 1642 when 50 Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

families from the New Haven Colony

New Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was an English colonial venture in present-day Connecticut in North America from 1637 to 1662.- Quinnipiac Colony :A Puritan minister named John Davenport led his flock from exile in the Netherlands back to England and finally to America in the spring of 1637...

in Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

led by George Lamberton attempted to establish a theocracy

Theocracy

Theocracy is a form of organization in which the official policy is to be governed by immediate divine guidance or by officials who are regarded as divinely guided, or simply pursuant to the doctrine of a particular religious sect or religion....

at the mouth of the Schuylkill River

Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River is a river in Pennsylvania. It is a designated Pennsylvania Scenic River.The river is about long. Its watershed of about lies entirely within the state of Pennsylvania. The source of its eastern branch is in the Appalachian Mountains at Tuscarora Springs, near Tamaqua in...

. The New Haven Colony had earlier struck a deal with the Native Americans to buy much of New Jersey south of Trenton (although the tribes Lenape were to be accused of selling the same land twice). The Dutch and Swedes in the area burned their buildings. A Swedish court under Swedish Governor Johan Björnsson Printz

Johan Björnsson Printz

Johan Björnsson Printz was governor from 1643 until 1653 of the Swedish colony of New Sweden on the Delaware River in North America.-Early Life in Sweden:...

was to convict Lamberton of "trespassing, conspiring with the Indians." The New Haven colony received no support and Puritan Governor John Winthrop

John Winthrop

John Winthrop was a wealthy English Puritan lawyer, and one of the leading figures in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the first major settlement in New England after Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the first large wave of migrants from England in 1630, and served as governor for 12 of...

testified that the New Haven Colony

New Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was an English colonial venture in present-day Connecticut in North America from 1637 to 1662.- Quinnipiac Colony :A Puritan minister named John Davenport led his flock from exile in the Netherlands back to England and finally to America in the spring of 1637...

was dissolved owing to summer "sickness and mortality." The disaster was to contribute to New Haven's ultimate loss of its home colony to the Connecticut Colony

Connecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in British America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritan noblemen. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English...

.

In 1644, New Sweden

New Sweden

New Sweden was a Swedish colony along the Delaware River on the Mid-Atlantic coast of North America from 1638 to 1655. Fort Christina, now in Wilmington, Delaware, was the first settlement. New Sweden included parts of the present-day American states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania....

supported the Susquehannocks in their victory in a war against the English Province of Maryland, lead by General Harrison the second. The Dutch never recognized the legitimacy of the Swedish claim and in the late summer of 1655 Director-General Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant , served as the last Dutch Director-General of the colony of New Netherland from 1647 until it was ceded provisionally to the English in 1664, after which it was renamed New York...

muster a military expedition to the Delaware Valley and subdued the rogue colony. Though the colonists now recognized the authority of New Netherland

New Netherland

New Netherland, or Nieuw-Nederland in Dutch, was the 17th-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the East Coast of North America. The claimed territories were the lands from the Delmarva Peninsula to extreme southwestern Cape Cod...

, the Dutch terms were quite tolerant and the Swedish and Finnish settlers continued to enjoy a much local autonomy, having their own militia, religion, court, and lands. This official status lasted until the English conquest of New Netherland

New Netherland

New Netherland, or Nieuw-Nederland in Dutch, was the 17th-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the East Coast of North America. The claimed territories were the lands from the Delmarva Peninsula to extreme southwestern Cape Cod...

in October 1664, and continued unofficially until the area was included in William Penn's charter for Pennsylvania, in 1682. By 1682 the area of modern Philadelphia was inhabited by about fifty Europeans, mostly subsistence farmers.

In 1681, as part of a repayment of a debt, Charles II of England

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

granted William Penn

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

a charter

Charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified...

for what would become the Pennsylvania colony

Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as Pennsylvania Colony, was founded in British America by William Penn on March 4, 1681 as dictated in a royal charter granted by King Charles II...

. Shortly after receiving the charter, Penn said he would lay out "a large Towne or Citty in the most Convenient place upon the Delaware River

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river on the Atlantic coast of the United States.A Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson in 1609 first mapped the river. The river was christened the South River in the New Netherland colony that followed, in contrast to the North River, as the Hudson River was then...

for health & Navigation." Penn wanted the city to live peacefully in the area, without a fortress or walls

Defensive wall

A defensive wall is a fortification used to protect a city or settlement from potential aggressors. In ancient to modern times, they were used to enclose settlements...

, so he bought the land from the Lenape. The legend

Legend

A legend is a narrative of human actions that are perceived both by teller and listeners to take place within human history and to possess certain qualities that give the tale verisimilitude...

is that Penn made a treaty of friendship with Lenape chief Tammany

Tamanend

Tamanend or Tammany or Tammamend, the "affable", was a chief of one of the clans that made up the Lenni-Lenape nation in the Delaware Valley at the time Philadelphia was established...

under an elm tree at Shackamaxon

Shackamaxon

Shackamaxon or Shakamaxon was a historic village along the Delaware River inhabited by Delaware Indians in North America. It was located within what are now the borders of the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States....

, in what became the city's Kensington District

Kensington District, Pennsylvania

Kensington District, or The Kensington District of the Northern Liberties, was one of the twenty-nine municipalities that formed Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania prior to the enactment of the Act of Consolidation, 1854, when it became incorporated into the newly expanded City of Philadelphia...

. Penn envisioned a city where all people regardless of religion could worship freely and live together. Being a Quaker

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

, Penn had experienced religious persecution. He also planned that the city's streets would be set up in a grid, with the idea that the city would be more like the rural towns of England than its crowded cities. The homes would be spread far apart and surrounded by gardens and orchards. The city would grant the first purchasers, the landowners who first bought land in the colony, land along the river for their homes. The city, which he named Philadelphia (philos, "love" or "friendship", and adelphos, "brother"), would have a commercial center for a market, state house, and other key buildings.

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river on the Atlantic coast of the United States.A Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson in 1609 first mapped the river. The river was christened the South River in the New Netherland colony that followed, in contrast to the North River, as the Hudson River was then...

between modern South

South Street (Philadelphia)

South Street is an east-west street forming the southern border of the Center City neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the northern border for the neighborhoods of South Philadelphia. The stretch of South Street between Front Street and Seventh Street is known for its "bohemian"...

and Vine Streets. Penn arrived in Philadelphia in October 1682. He felt the area was too cramped and expanded the city west to the bank of the Schuylkill River

Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River is a river in Pennsylvania. It is a designated Pennsylvania Scenic River.The river is about long. Its watershed of about lies entirely within the state of Pennsylvania. The source of its eastern branch is in the Appalachian Mountains at Tuscarora Springs, near Tamaqua in...

, making the city a total of 1,200 acres (4.8 km²). Streets were laid out in a gridiron

Grid plan

The grid plan, grid street plan or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid...

system. Except for the two widest streets, High (now Market)

Market Street (Philadelphia)

Market Street, originally known as High Street, is a major east–west street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. For the majority of its length, it serves as Pennsylvania Route 3....

and Broad

Broad Street (Philadelphia)

Broad Street is a major arterial street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and is nearly 13 miles long.It is Pennsylvania Route 611 along its entire length with the exception of its northernmost part between Old York Road and Pennsylvania Route 309 and the southernmost part south of Interstate 95...

, the streets were named after prominent landowners who owned adjacent lots. The streets were later renamed in 1684; the ones running east-west were renamed after local trees and the north-south streets were numbered. Within the area, four squares (now named Rittenhouse

Rittenhouse Square

Rittenhouse Square is one of the five original open-space parks planned by William Penn and his surveyor Thomas Holme during the late 17th century in central Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The park cuts off 19th Street at Walnut Street and also at a half block above Manning Street. Its boundaries are...

, Logan

Logan Circle (Philadelphia)

Logan Circle, also known as Logan Square, is an open-space park in Center City Philadelphia's northwest quadrant and one of the five original planned squares laid out on the city grid. The circle itself exists within the original bounds of the square; the names Logan Square and Logan Circle are...

, Washington

Washington Square (Philadelphia)

Washington Square, originally designated in 1682 as Southeast Square, is an open-space park in Center City Philadelphia's Southeast quadrant and one of the five original planned squares laid out on the city grid by William Penn's surveyor, Thomas Holme. It is part of both the Washington Square West...

and Franklin

Franklin Square (Philadelphia)

Franklin Square is one of the five original open-space parks planned by William Penn during the late 17th century in central Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.- History :...

) were set up as parks open for everyone. Penn designed a central square at the intersection of Broad and what is now Market Street that would be surrounded by public buildings.

Some of the first settlers lived in caves dug out of the river bank, but the city grew with construction of homes, churches, and wharves. The new landowners did not share Penn's vision of a non-congested city. Most people bought land along the Delaware River instead of spreading westward towards the Schuylkill. The lots they bought were subdivided and resold with smaller streets constructed between them. Before 1704, few people lived west of Fourth Street.

Early growth

Philadelphia grew from a few hundred inhabitants in 1683 to over 2,500 in 1701. The population was mostly English, WelshWales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, Irish, Germans

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, Swedes, Finns

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, Dutch, and African slaves

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. Before William Penn left Philadelphia for the last time on October 25, 1701 he issued the Charter of 1701. The charter established Philadelphia as a city and gave the mayor

Mayor

In many countries, a Mayor is the highest ranking officer in the municipal government of a town or a large urban city....

, aldermen

Alderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members themselves rather than by popular vote, or a council...

, and councilmen the authority to issue laws and ordinances and regulate markets and fairs. The first known Jewish

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

resident of Philadelphia was Jonas Aaron, a German who moved to the city in 1703. He is mentioned in an article entitled "A Philadelphia Business Directory of 1703," by Charles H. Browning. It was published in "The American Historical Register," in April, 1895.

As Philadelphia became established it gradually became an important trading center. Initially the city's main source of trade was with the West Indies

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

. However Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War , as the North American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession was known in the British colonies, was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought between France and England, later Great Britain, in North America for control of the continent. The War of the...

, which lasted between 1702 and 1713, cut off trade and hurt Philadelphia financially. The end of the war brought brief prosperity to all of the British territories, but a depression

Recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction, a general slowdown in economic activity. During recessions, many macroeconomic indicators vary in a similar way...

in the 1720s stunted Philadelphia's growth. The 1720s and '30s saw immigration from mostly Germany and Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

to Philadelphia and the surrounding countryside. The countryside around Philadelphia was soon turned into farmland and exports of breadstuffs, along with lumber products and flax

Flax

Flax is a member of the genus Linum in the family Linaceae. It is native to the region extending from the eastern Mediterranean to India and was probably first domesticated in the Fertile Crescent...

seeds, to Europe and elsewhere in the American colonies helped bring Philadelphia out of the depression.

Philadelphia's pledge of religious tolerance attracted many other religions beside Quakers. Mennonite

Mennonite

The Mennonites are a group of Christian Anabaptist denominations named after the Frisian Menno Simons , who, through his writings, articulated and thereby formalized the teachings of earlier Swiss founders...

s, Pietists

Pietism

Pietism was a movement within Lutheranism, lasting from the late 17th century to the mid-18th century and later. It proved to be very influential throughout Protestantism and Anabaptism, inspiring not only Anglican priest John Wesley to begin the Methodist movement, but also Alexander Mack to...

, Anglicans

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

, Catholics

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

, and Jews

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

had moved to the city and soon Quakers were a minority although they were still powerful politically. However, there were still political tensions between and within the religious groups. A series of riot

Riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder characterized often by what is thought of as disorganized groups lashing out in a sudden and intense rash of violence against authority, property or people. While individuals may attempt to lead or control a riot, riots are thought to be typically chaotic and...

s in 1741 and 1742, whose causes ranged between bread prices and drunken sailors, climaxed in October 1742. The "Bloody Election" riots had sailors attack Quakers and pacifist Germans whose peace politics were strained by the War of Jenkins' Ear

War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear was a conflict between Great Britain and Spain that lasted from 1739 to 1748, with major operations largely ended by 1742. Its unusual name, coined by Thomas Carlyle in 1858, relates to Robert Jenkins, captain of a British merchant ship, who exhibited his severed ear in...

. The city was also plagued by pickpockets and other petty criminals. Working in the city government had such a poor reputation that fines were imposed on citizens who refused to serve an office after being chosen. One man fled Philadelphia to avoid serving as mayor.

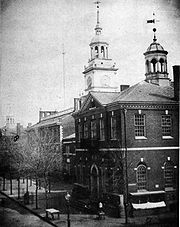

Christ Church, Philadelphia

Christ Church is an Episcopal church located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1695 by members of the Church of England, who built a small wooden church on the site by the next year. When the congregation outgrew this structure some twenty years later, they decided to erect a new...

and the Pennsylvania State House, better known as Independence Hall, were giving the city a skyline

Skyline

A skyline is the overall or partial view of a city's tall buildings and structures consisting of many skyscrapers in front of the sky in the background. It can also be described as the artificial horizon that a city's overall structure creates. Skylines serve as a kind of fingerprint of a city, as...

. Streets were paved and illuminated with gas lights

Gas lighting

Gas lighting is production of artificial light from combustion of a gaseous fuel, including hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, propane, butane, acetylene, ethylene, or natural gas. Before electricity became sufficiently widespread and economical to allow for general public use, gas was the most...

. Philadelphia's first newspaper

Newspaper

A newspaper is a scheduled publication containing news of current events, informative articles, diverse features and advertising. It usually is printed on relatively inexpensive, low-grade paper such as newsprint. By 2007, there were 6580 daily newspapers in the world selling 395 million copies a...

, Andrew Bradford

Andrew Bradford

Andrew Bradford was an early American printer in colonial Philadelphia. He published the first newspaper in Pennsylvania in 1729....

's American Weekly Mercury, began publishing on December 22, 1719.

The city also developed culturally and scientifically. Schools, libraries and theaters were founded. James Logan

James Logan (statesman)

James Logan , a statesman and scholar, was born in Lurgan, County Armagh, Ireland of Scottish descent and Quaker parentage. In 1689, the Logan family moved to Bristol, England where, in 1693, James replaced his father as schoolmaster...

arrived in Philadelphia in 1701 as a secretary for William Penn. He was the first to help establish Philadelphia as a place of culture and learning. Logan, who was the mayor of Philadelphia in the early 1720s, created one of the largest libraries in the colonies. He also helped guide other prominent Philadelphia residents, which included botanist John Bartram

John Bartram

*Hoffmann, Nancy E. and John C. Van Horne, eds., America’s Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram 1699-1777. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 243. ....

and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

. Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia in October 1723 and would play a large part in the city's development. To help protect the city from fire, Franklin founded the Union Fire Company

Union Fire Company

Union Fire Company, sometimes called Benjamin Franklin's Bucket Brigade, was a volunteer fire department formed in Philadelphia in 1736 with the assistance of Benjamin Franklin. The first fire fighting organization in Philadelphia, though followed within the year by the Fellowship Fire Company...

. In the 1750s Franklin was named one of the city's post master generals and he established postal routes between Philadelphia, New York

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, Boston, and elsewhere. He helped raise money to build the American colonies' first hospital

Pennsylvania Hospital

Pennsylvania Hospital is a hospital in Center City, Philadelphia, affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania Health System . Founded on May 11, 1751 by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Bond, it was the first hospital in the United States...

, which opened in 1752. That same year the College of Philadelphia

The Academy and College of Philadelphia

The Academy and College of Philadelphia in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, is considered by many to have been the first American academy. It was founded in 1749 by Benjamin Franklin....

, another project Franklin led, received its charter of incorporation. Threatened by French and Spanish privateer

Privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship authorized by a government by letters of marque to attack foreign shipping during wartime. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without having to spend public money or commit naval officers...

s, Franklin and others set up a volunteer group for defense and built two batteries. When the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

began Franklin was able to allow the creation of militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

s. During the war, the city became home to many refugees from the west. When Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's War, Pontiac's Conspiracy, or Pontiac's Rebellion was a war that was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of elements of Native American tribes primarily from the Great Lakes region, the Illinois Country, and Ohio Country who were dissatisfied with British postwar policies in the...

occurred in 1763, refugees again fled into the city, including a group of Native Americans hiding from other Native Americans angry at their pacifism and violent white frontiersmen. A group called the Paxton Boys

Paxton Boys

The Paxton Boys were a vigilante group who murdered 20 Susquehannock in events collectively called the Conestoga Massacre. Scots-Irish frontiersmen from central Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna River formed a vigilante group to retaliate against local American Indians in the aftermath of the...

attempted to enter Philadelphia and kill the Native Americans, but was prevented by the city's militia and Franklin who convinced them to leave.

Revolution

In the 1760s the Stamp ActStamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765 was a direct tax imposed by the British Parliament specifically on the colonies of British America. The act required that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper produced in London, carrying an embossed revenue stamp...

and the Townshend Acts

Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts were a series of laws passed beginning in 1767 by the Parliament of Great Britain relating to the British colonies in North America. The acts are named after Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who proposed the program...

, combined with other frustrations, were causing anger against England in the colonies, Philadelphia included. Both the Stamp and Townshend Acts led to boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

s of the importation of British goods. After the Tea Act

Tea Act

The Tea Act was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. Its principal overt objective was to reduce the massive surplus of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses. A related objective was to undercut the price of tea smuggled into Britain's...

in 1773, there were threats against anyone who would store tea and any ships which brought tea up the Delaware. In December, after the Boston Tea Party

Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a direct action by colonists in Boston, a town in the British colony of Massachusetts, against the British government and the monopolistic East India Company that controlled all the tea imported into the colonies...

, a shipment of tea had arrived on the ship the Polly. The captain left after a committee told him to leave without dropping off his cargo.

A series of acts

Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts or the Coercive Acts are names used to describe a series of laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 relating to Britain's colonies in North America...

in 1774 further angered the colonies and there was a call for a general congress. The Massachusetts Assembly of June 17, 1774 suggested the general congress meeting be held in Philadelphia. The First Continental Congress

First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from twelve of the thirteen North American colonies that met on September 5, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, early in the American Revolution. It was called in response to the passage of the Coercive Acts by the...

was held in September in Carpenters' Hall

Carpenters' Hall

Carpenters' Hall is a two-story brick building in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that was a key meeting place in the early history of the United States. Completed in 1773 and set back from Chestnut Street, the meeting hall was built for and is still owned by the...

. The American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

began after the Battles of Lexington and Concord

Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. They were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy , and Cambridge, near Boston...

in April, 1775 and the Second Continental Congress

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that started meeting on May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon after warfare in the American Revolutionary War had begun. It succeeded the First Continental Congress, which met briefly during 1774,...

met the next month at the Pennsylvania State House where they would sign the Declaration of Independence

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

more than a year later. Besides being the location of the Continental Congress, Philadelphia was important to the war effort, as Robert Morris

Robert Morris (merchant)

Robert Morris, Jr. was a British-born American merchant, and signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution...

described "You will consider Philadelphia, from its centrical situation, the extent of its commerce, the number of its artificers, manufactures and other circumstances, to be to the United States what the heart is to the human body in circulating the blood."

Philadelphia was vulnerable to attack by the British. There were efforts to help protect the city from invasion from Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is a major estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the Northeast seaboard of the United States whose fresh water mixes for many miles with the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. It is in area. The bay is bordered by the State of New Jersey and the State of Delaware...

and to recruit more soldiers, but there was no serious defense for the city. In March 1776 two British frigate

Frigate

A frigate is any of several types of warship, the term having been used for ships of various sizes and roles over the last few centuries.In the 17th century, the term was used for any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built"...

s began a blockade

Blockade

A blockade is an effort to cut off food, supplies, war material or communications from a particular area by force, either in part or totally. A blockade should not be confused with an embargo or sanctions, which are legal barriers to trade, and is distinct from a siege in that a blockade is usually...

of the mouth of Delaware Bay and the British were moving south through New Jersey

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

. In December the fear that the city was about to be invaded led to half of Philadelphia's population fleeing the city, including the Continental Congress which had fled to Baltimore. General George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

pushed back the British advance at the Battles of Princeton

Battle of Princeton

The Battle of Princeton was a battle in which General George Washington's revolutionary forces defeated British forces near Princeton, New Jersey....

and Trenton

Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Trenton took place on December 26, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, after General George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River north of Trenton, New Jersey. The hazardous crossing in adverse weather made it possible for Washington to lead the main body of the...

and the refugees and Congress returned. In September 1777 the British invaded Philadelphia from the south. General George Washington intercepted them at the Battle of Brandywine

Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of the Brandywine or the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American army of Major General George Washington and the British-Hessian army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777. The British defeated the Americans and...

but was driven back. Thousands fled north into Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

and east into New Jersey; Congress fled to Lancaster

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster is a city in the south-central part of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is the county seat of Lancaster County and one of the older inland cities in the United States, . With a population of 59,322, it ranks eighth in population among Pennsylvania's cities...

then to York

York, Pennsylvania

York, known as the White Rose City , is a city located in York County, Pennsylvania, United States which is in the South Central region of the state. The population within the city limits was 43,718 at the 2010 census, which was a 7.0% increase from the 2000 count of 40,862...

. British troops marched into the half-empty Philadelphia on September 23 to cheering Loyalist

Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to the Kingdom of Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. At the time they were often called Tories, Royalists, or King's Men. They were opposed by the Patriots, those who supported the revolution...

crowds.

The occupation lasted ten months; with the French now helping the Americans, the last British troops pulled out of Philadelphia on June 18, 1778 to help defend New York City. The American troops arrived the same day and began reoccupying the city under supervision of Major General Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold V was a general during the American Revolutionary War. He began the war in the Continental Army but later defected to the British Army. While a general on the American side, he obtained command of the fort at West Point, New York, and plotted to surrender it to the British forces...

, who had been appointed the city's military commander. The city government returned a week later and the Continental Congress returned in early July. While no longer under serious threat by the British, Philadelphia was experiencing serious inflation

Inflation

In economics, inflation is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation also reflects an erosion in the purchasing power of money – a...

issues, with the poor suffering the worst. This led to unrest in 1779, with people blaming the upper class and Loyalists. One riot in January which had sailors striking for higher wages ended up dismantling ships. The Fort Wilson Riot on October 4 had a group of men target James Wilson

James Wilson

James Wilson was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence. Wilson was elected twice to the Continental Congress, and was a major force in drafting the United States Constitution...

, a signer of the Declaration of Independence but accused of being a Loyalist sympathizer. Soldiers broke up the riot, but five people had died and seventeen were injured.

Temporary capital

.jpg)

Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783

The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 was an anti-government protest by nearly 400 soldiers of the Continental Army in June 1783...

, the United States Congress had moved out of Philadelphia, eventually settling in New York City. Besides the Constitutional Convention

Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to address problems in governing the United States of America, which had been operating under the Articles of Confederation following independence from...

in May 1787, United States politics was no longer centered in Philadelphia. Philadelphians tried to lobby and petition the Congress to move back to Philadelphia or southeastern Pennsylvania. However, a permanent capital was selected to be along the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

and Philadelphia was selected to be the temporary United States capital for ten years starting in 1790. Congress occupied the Philadelphia County Courthouse, which became known as Congress Hall, and the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

worked at City Hall. Robert Morris donated his home on Market Street to be the residence for President Washington.

With the end of the war the city began cleaning up the damage and after 1787 the city's economy experienced accelerated growth. The growth was interrupted by yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

outbreaks in the 1790s. Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush was a Founding Father of the United States. Rush lived in the state of Pennsylvania and was a physician, writer, educator, humanitarian and a Christian Universalist, as well as the founder of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania....

identified the first outbreak in August 1793

Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793 is believed to have killed several thousand people in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.-Beginnings:...

. Fear of contracting the disease caused thousands to flee the city and trade virtually stopped as people were fearful of coming to the city or interacting with its inhabitants. The fever abated at the end of October with the onset of colder weather. The death toll is believed to be more than 5,000, about a tenth of the population. Yellow fever continued to resurface over the next few decades with none as bad as the one in 1793. The closest came in 1798 where again thousands fled the city and led to the deaths of an estimated 1,292.

Industrial growth

Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 and the subsequent Nonintercourse Acts were American laws restricting American ships from engaging in foreign trade between the years of 1807 and 1812. The Acts were diplomatic responses by presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison designed to protect American interests...

and then the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

. After the war, Philadelphia's shipping industry never returned to its pre-embargo status and New York City would soon become the United States' busiest port and largest city.

The embargo and lack of foreign trade helped establish factories in and around Philadelphia to make goods that were no longer available from foreign markets. Manufacturing plants

Factory

A factory or manufacturing plant is an industrial building where laborers manufacture goods or supervise machines processing one product into another. Most modern factories have large warehouses or warehouse-like facilities that contain heavy equipment used for assembly line production...

and foundries

Foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal in a mold, and removing the mold material or casting after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals processed are aluminum and cast iron...

were built and Philadelphia became an important center of paper-related industries and the leather, shoe, and boot industries. Coal and iron mines, and the construction of new roads, canal

Canal

Canals are man-made channels for water. There are two types of canal:#Waterways: navigable transportation canals used for carrying ships and boats shipping goods and conveying people, further subdivided into two kinds:...

s, and railroads helped Philadelphia's manufacturing power grow and the city became the United States' first major industrial city. Major industrial projects included the Waterworks

Fairmount Water Works

The Fairmount Water Works in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was Philadelphia's second municipal waterworks. Designed in 1812 by Frederick Graff and built between 1812 and 1872, it operated until 1909, winning praise for its design and becoming a popular tourist attraction...

, iron water pipes, a gasworks, and the U.S. Naval Yard

Philadelphia Naval Shipyard

The Philadelphia Naval Business Center, formerly known as the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard and Philadelphia Navy Yard, was the first naval shipyard of the United States. The U.S. Navy reduced its activities there in the 1990s, and ended most of them on September 30, 1995...

. Along with its industrial power, Philadelphia was also the financial center of the country. Along with chartered and private banks, the city was the home of the First

First Bank of the United States

The First Bank of the United States is a National Historic Landmark located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania within Independence National Historical Park.-Banking History:...

and Second Banks of the United States

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816, five years after the First Bank of the United States lost its own charter. The Second Bank of the United States was initially headquartered in Carpenters' Hall, Philadelphia, the same as the First Bank, and had branches throughout the...

, Mechanics National Bank

Mechanics National Bank

The Mechanics National Bank was a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, bank founded by and geared toward mechanics.-History:In 1809, Philadelphia was already known for both skilled workers and as America's main financial center, but the merchants who controlled its banks had little interest in lending to...

and the first U.S. Mint

Philadelphia Mint

The Philadelphia Mint was created from the need to establish a national identity and the needs of commerce in the United States. This led the Founding Fathers of the United States to make an establishment of a continental national mint a main priority after the ratification of the Constitution of...

. Cultural institutions such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is a museum and art school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1805 and is the oldest art museum and school in the United States. The academy's museum is internationally known for its collections of 19th and 20th century American paintings,...

, the Academy of Natural Sciences

Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the New World...

, the Athenaeum and the Franklin Institute

Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and one of the oldest centers of science education and development in the United States, dating to 1824. The Institute also houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial.-History:On February 5, 1824, Samuel Vaughn Merrick and...

also developed. Public education became available after the Pennsylvania General Assembly

Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times , the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. Since the Constitution of 1776, written by...

passed the Free School Law of 1834.

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

, smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

, tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

, and cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

, with the poor being affected the worst.

Along with sanitation, violence was a serious problem. Gang

Gang

A gang is a group of people who, through the organization, formation, and establishment of an assemblage, share a common identity. In current usage it typically denotes a criminal organization or else a criminal affiliation. In early usage, the word gang referred to a group of workmen...

s like the Moyamensing Killers and the Blood Tubs controlled various neighborhoods. During the 1840s and early 1850s when volunteer fire companies, some of which were infiltrated by gangs, responded to a fire, fights with other fire companies would usually break out. The lawlessness among fire companies virtually ended in 1853 and 1854 when the city took more control over their operations. The 1840s and 50s also saw a lot of violence directed against immigrants. Nativists

Nativism (politics)

Nativism favors the interests of certain established inhabitants of an area or nation as compared to claims of newcomers or immigrants. It may also include the re-establishment or perpetuation of such individuals or their culture....

had a strong presence in the city and often held mostly anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is a generic term for discrimination, hostility or prejudice directed against Catholicism, and especially against the Catholic Church, its clergy or its adherents...

, anti-Irish meetings. Violence against immigrants also occurred, the worst being the nativist riots in 1844

Philadelphia Nativist Riots

The Philadelphia Nativist Riots were a series of riots that took place between May 6 and 8 and July 6 and 7, 1844, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, and the adjacent districts of Kensington and Southwark...

. Violence against African Americans was also common during the 1830s, 40s, and 50s. Deadly race riots led to African American homes and churches being burned. In 1841, Joseph Sturge

Joseph Sturge

Joseph Sturge , son of a farmer in Gloucestershire, was an English Quaker, abolitionist and activist. He founded the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society . He worked throughout his life in Radical political actions supporting pacifism, working-class rights, and the universal emancipation of...

commented "...there is probably no city in the known world where dislike, amounting to the hatred of the coloured population, prevails more than in the city of brotherly love!" Despite the formation of several anti-slavery societies, and being a major stop on the Underground Railroad

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause. The term is also applied to the abolitionists,...

, much of Philadelphia was against the abolitionist

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

movement. Abolitionists were also the target of violence which included several of their meetinghouses being burned.

The lawlessness and the difficulty in controlling it, along with a large population shift just north of Philadelphia, led to the Act of Consolidation in 1854

Act of Consolidation, 1854

The Act of Consolidation, more formally known as the act of February 2, 1854 , was enacted by General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and approved February 2, 1854 by Governor William Bigler...

. The act passed on February 2, made Philadelphia's borders coterminous with Philadelphia County

Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania

-History:Tribes of Lenape were the first known occupants in the area which became Philadelphia County. The first European settlers were Swedes and Finns who arrived in 1638. The Netherlands seized the area in 1655, but permanently lost control to England in 1674...

, incorporating various district

District

Districts are a type of administrative division, in some countries managed by a local government. They vary greatly in size, spanning entire regions or counties, several municipalities, or subdivisions of municipalities.-Austria:...

s, borough

Borough

A borough is an administrative division in various countries. In principle, the term borough designates a self-governing township although, in practice, official use of the term varies widely....

s, townships

Township (United States)

A township in the United States is a small geographic area. Townships range in size from 6 to 54 square miles , with being the norm.The term is used in three ways....

, and any other unincorporated communities

Unincorporated area

In law, an unincorporated area is a region of land that is not a part of any municipality.To "incorporate" in this context means to form a municipal corporation, a city, town, or village with its own government. An unincorporated community is usually not subject to or taxed by a municipal government...

within the county.

Once the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

began in 1861, Philadelphia's southern

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

leanings changed and hostility moved from abolitionists to southern sympathizers. Mobs threatened a secessionist newspaper and the homes of suspected sympathizers and were only turned away by the police and Mayor Alexander Henry. Philadelphia supported the war with soldiers, ammunition, war ships and was a main source of army uniforms. Philadelphia was also a major receiving place of the wounded, with more than 157,000 soldiers and sailors treated within the city. Philadelphia began preparing for invasion in 1863, but the southern army was repelled at Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

.

Late 19th century

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

, and Italy started rivaling immigration from Western Europe. Much of the immigration from Russia and Eastern Europe were Jews. In 1881 there were around 5,000 Jews in the city

Jewish history in Philadelphia

The Jews of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania can trace their history back to Colonial America. Jews have lived there since the arrival of William Penn in 1682.-Early history:...

and by 1905 there were around 100,000. Philadelphia's Italian population grew from around 300 in 1870 to around 18,000 in 1900, with the majority settling in South Philadelphia

South Philadelphia

South Philadelphia, nicknamed South Philly, is the section of Philadelphia bounded by South Street to the north, the Delaware River to the east and south, and the Schuylkill River to the west.-History:...

. Along with foreign immigration, domestic immigration from African Americans gave Philadelphia the largest African American population of a Northern U.S.

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

city. In 1876 there were around 25,000 African Americans living in Philadelphia and by 1890 the population was near 40,000. While immigrants moved into the city Philadelphia's rich emptied out. During the 1880s much of Philadelphia's upper class moved into the growing suburbs along the Pennsylvania Railroad's Main Line

Pennsylvania Main Line

The Main Line is an unofficial historical and socio-cultural region of suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, comprising a collection of affluent towns built along the old Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad which ran northwest from downtown Philadelphia parallel to Lancaster Avenue , a road...

west of the city.

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

, and a political machine

Political machine

A political machine is a political organization in which an authoritative boss or small group commands the support of a corps of supporters and businesses , who receive rewards for their efforts...

. The Republicans dominated the post-war elections and corrupt officials made their way into the government and continued to control the city through voter fraud and intimidation. The Gas Trust was the hub of the city’s political machine. The trust

Trust (19th century)

A special trust or business trust is a business entity formed with intent to monopolize business, to restrain trade, or to fix prices. Trusts gained economic power in the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some, but not all, were organized as trusts in the legal sense...

controlled the gas company which supplied gas for lighting to the city. The board came under complete control by Republicans in 1865, and they used their power to award contracts and perks for themselves and their interests. Some government reform did occur during this time. The police department was reorganized and volunteer fire companies were eliminated and were replaced by a paid fire department

Philadelphia Fire Department

The Philadelphia Fire Department provides firefighting and Emergency Medical Services within the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania....

. Education was reformed as well with a compulsory school

Compulsory education

Compulsory education refers to a period of education that is required of all persons.-Antiquity to Medieval Era:Although Plato's The Republic is credited with having popularized the concept of compulsory education in Western intellectual thought, every parent in Judea since Moses's Covenant with...

act passed in 1895 and the Public School Reorganization Act which freed the city's education from the city's political machine. Higher education changed as well. The University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

moved to West Philadelphia

West Philadelphia