Joseph Sturge

Encyclopedia

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn, and the entire Forest of Dean....

, was an English Quaker, abolitionist and activist. He founded the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society

Anti-Slavery Society

The Anti-Slavery Society or A.S.S. was the everyday name of two different British organizations.The first was founded in 1823 and was committed to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Its official name was the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the...

(now Anti-Slavery International

Anti-Slavery International

Anti-Slavery International is an international nongovernmental organization, charity and a lobby group, based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1839, it is the world's oldest international human rights organization, and the only charity in the United Kingdom to work exclusively against slavery and...

). He worked throughout his life in Radical

Political radicalism

The term political radicalism denotes political principles focused on altering social structures through revolutionary means and changing value systems in fundamental ways...

political actions supporting pacifism

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

, working-class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

rights, and the universal emancipation

Emancipation

Emancipation means the act of setting an individual or social group free or making equal to citizens in a political society.Emancipation may also refer to:* Emancipation , a champion Australian thoroughbred racehorse foaled in 1979...

of slaves. In the late 1830s he published two books about the apprenticeship system in Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

, which helped persuade the British Parliament to adopt an earlier full emancipation date. In Jamaica, Sturge also helped found Free Villages

Free Villages

Free Villages is the term used for Caribbean settlements, particularly in Jamaica, founded in the 1830s and 1840s independent of the control of plantation owners and other major estates.-Pioneering the concept:...

with the Baptists, to provide living quarters for freed slaves; one was named "Sturge Town" in his memory.

Early career

Joseph Sturge went to BirminghamBirmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

to work in 1822. A member of the Religious Society of Friends

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

(commonly known as Quakers), he refused to deal in grain used in the manufacture of alcoholic spirits, although he was a corn factor

Factor (agent)

A factor, from the Latin "he who does" , is a person who professionally acts as the representative of another individual or other legal entity, historically with his seat at a factory , notably in the following contexts:-Mercantile factor:In a relatively large company, there could be a hierarchy,...

.

In rapidly expanding industrial Birmingham, he was appointed an alderman

Alderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members themselves rather than by popular vote, or a council...

in 1835. He opposed the building of the Birmingham Town Hall

Birmingham Town Hall

Birmingham Town Hall is a Grade I listed concert and meeting venue in Victoria Square, Birmingham, England. It was created as a home for the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival established in 1784, the purpose of which was to raise funds for the General Hospital, after St Philip's Church became...

, to be used for performances, because of his conscientious objection to the performance of sacred oratorio

Oratorio

An oratorio is a large musical composition including an orchestra, a choir, and soloists. Like an opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias...

. Joseph Sturge became interested in the island of Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

and the conditions of its enslaved workers. He visited it several times and witnessed first hand the horrors of slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

, as well as the abuses under an apprenticeship system designed to control the labour of all former slaves above the age of six for 12 years. He worked for emancipation and abolition with African-Caribbean

British African-Caribbean community

The British African Caribbean communities are residents of the United Kingdom who are of West Indian background and whose ancestors were primarily indigenous to Africa...

and English Baptists.

In 1838, after full emancipation was authorized, Sturge laid the foundation stone to the "Emancipation School Rooms" in Birmingham. Attending were United Baptist

Baptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

Sunday School

Sunday school

Sunday school is the generic name for many different types of religious education pursued on Sundays by various denominations.-England:The first Sunday school may have been opened in 1751 in St. Mary's Church, Nottingham. Another early start was made by Hannah Ball, a native of High Wycombe in...

and Baptist ministers of the city.

In 1839 his work was honoured by a marble monument in a Baptist mission chapel in Falmouth, Jamaica

Falmouth, Jamaica

Falmouth is the chief town and capital of the parish of Trelawny in Jamaica. It is situated on Jamaica's north coast 18 miles east of Montego Bay. It is noted for being one of the Caribbean’s best-preserved Georgian towns....

. It was dedicated to "the Emancipated Sons of Africa".

Campaign against indentured apprenticeship

After legislation for the abolition of slaverySlavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

in the British dominions was enacted in 1833, slave-owning planters in the West Indies lobbied to postpone freedom for adults for twelve years in a form of indenture. Enslaved children under the age of six were emancipated by the new law on 1 August 1834, but older children and adults had to serve a period of bonded labour or "indentured apprenticeship". Sturge led a campaign against this delaying mechanism.

His work to speed up adult emancipation was supported by Quaker abolitionists, including William Allen

William Allen (Quaker)

William Allen FRS, FLS was an English scientist and philanthropist who opposed slavery and engaged in schemes of social and penal improvement in early nineteenth century England.-Early life:...

, Lord Brougham

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux was a British statesman who became Lord Chancellor of Great Britain.As a young lawyer in Scotland Brougham helped to found the Edinburgh Review in 1802 and contributed many articles to it. He went to London, and was called to the English bar in...

, and others. In a speech to the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

, Brougham acknowledged Sturge's central role at that time in rousing British anti-slavery opinion.

In 1834 Sturge sailed to the West Indies to study apprenticeship as defined by the British Emancipation Act of 1833. He intended to open it to criticism as an intermediate stage en route to emancipation. He traveled throughout the West Indies and talked directly to apprentices, proprietors (planters), and others directly involved. Upon his return to Great Britain, he published Narrative of Events since the First of August 1834; In it he cited an African-Caribbean witness, to whom he referred as "James Williams" to protect him from reprisals.

The original statement was signed by two free African-Caribbeans and six apprentices. As was customary at the time, it was authenticated, by Rev. Dr. Thomas Price

Thomas Price

Thomas Price was a stonecutter, teacher, lay preacher, businessman, stonemason, clerk-of-works, union secretary, union president and politician...

of Hackney, London, who wrote the introduction. Following another trip and further study, Sturge published The West Indies in 1837. Both books highlighted the cruelty and injustice of the system of indentured apprenticeship. Whilst in Jamaica, Sturge worked with the Baptist

Baptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

chapel

Chapel

A chapel is a building used by Christians as a place of fellowship and worship. It may be part of a larger structure or complex, such as a church, college, hospital, palace, prison or funeral home, located on board a military or commercial ship, or it may be an entirely free-standing building,...

s to found Free Villages

Free Villages

Free Villages is the term used for Caribbean settlements, particularly in Jamaica, founded in the 1830s and 1840s independent of the control of plantation owners and other major estates.-Pioneering the concept:...

, to create homes for freed slaves when they achieved full emancipation. They planned the communities to be outside the control of planters.

As a result of Sturge's single-minded campaign, in which he publicized details of the brutality of apprenticeship to shame the British Government, a major row broke out amongst abolitionists. The more radical element were pitted against the government. Although both had the same ends in sight, Sturge and the Baptists, with mainly Nonconformist support, led a successful popular movement for immediate and full emancipation. As a consequence, the British Government moved the date for full emancipation forward to 1 August 1838. They abolished the 12-year intermediary apprenticeship scheme. For many English Nonconformists and African-Caribbean people, 1 August 1838, became recognised as the true date of abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

International anti-slavery campaign

Anti-Slavery Society

The Anti-Slavery Society or A.S.S. was the everyday name of two different British organizations.The first was founded in 1823 and was committed to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Its official name was the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the...

, Sturge founded the Central Negro Emancipation Committee. More significantly, in 1839, one year after abolition in the British dominions (a time when many members of the Anti-Slavery Society considered their work to be completed), Sturge led a small group to found a new Anti-Slavery Society. They named it the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, based on the ambitious objective of achieving emancipation and an end to slavery worldwide. This society continues today as Anti-Slavery International

Anti-Slavery International

Anti-Slavery International is an international nongovernmental organization, charity and a lobby group, based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1839, it is the world's oldest international human rights organization, and the only charity in the United Kingdom to work exclusively against slavery and...

; its work is far from achieved since slavery exists on a large scale in many countries, albeit no longer legally.

In the 19th century, the Society's first major activity was to organize the first international conference, as well as the first devoted to abolition. It was known as the World's Anti-Slavery Conference and took place in June 1840 in London. Others were held in 1843 (Brussels) and 1849 (Paris). The convention was held at the Freemasons Hall on 12 June 1840. It attracted delegates from Europe, North America, and Caribbean countries, as well as the British dominions of Australia and Ireland, though no delegates from Africa attended. It included African-Caribbean delegates from Haiti

Haiti

Haiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

and Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

(then representing Britain), women activists from the United States, and many Nonconformists.

Commissioned by the society and its "moral radicals", a great painting of the event was completed. It hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, London to this day. The conference's political significance lay in the fact-finding groups it set up to report about slavery worldwide. It also created studied links between British investment and business and overseas slavery.

The conference was historically notable within the women's suffrage movement due to delegates' having excluded women's participation just prior to its opening. Activists Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Coffin Mott was an American Quaker, abolitionist, social reformer, and proponent of women's rights.- Early life and education:...

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American social activist, abolitionist, and leading figure of the early woman's movement...

were galvanized to organize a United States movement advocating woman's rights. Stanton, on her honeymoon at the time, and Mott were active in the US anti-slavery movement. The issue of women's participation provoked the split between followers of Garrison of the American Anti-Slavery Society

American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass was a key leader of this society and often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown was another freed slave who often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had...

and Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan was a New York abolitionist who worked to achieve the freedom of the illegally enslaved Africans of the Amistad. Contacted by Connecticut abolitionists soon after the Amistad arrived in port, Tappan focused extensively on the captive Africans...

's American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society

American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society

The American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society split off from the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1840 over a number of issues, including the increasing influence of anarchism , hostility to established religion, and feminism in the latter...

. The latter was ideologically congruent with Sturge's English counterpart.

In 1841 Sturge travelled in the United States with the poet John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier was an influential American Quaker poet and ardent advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. He is usually listed as one of the Fireside Poets...

to examine the slavery question there. He published his findings to promote American abolition. In 1845, Sturge visited Nottingham as he was local parliamentary candidate

Nottingham (UK Parliament constituency)

Nottingham was a parliamentary borough in Nottinghamshire, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1295. In 1885 the constituency was abolished and the city of Nottingham divided into three single-member constituencies....

. There he visited a Sunday School run by Samuel Fox. The idea of a school that taught not only scripture, but also basic skills such as reading and writing was taken up by Sturge. Sturge opened a similar school in about 1845.

Chartism and the Peace Society

On his return to England, Sturge supported the Chartist movement. In 1842 he ran as parliamentary candidate for NottinghamNottingham (UK Parliament constituency)

Nottingham was a parliamentary borough in Nottinghamshire, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1295. In 1885 the constituency was abolished and the city of Nottingham divided into three single-member constituencies....

, but was defeated by John Walter

John Walter (second)

John Walter was the son of John Walter, the founder of The Times, and second editor of it.He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School and Trinity College, Oxford...

, the proprietor of The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

.

He then took up the cause of peace and arbitration being pioneered by Henry Richard

Henry Richard

Rev. Henry Richard MP , "the Apostle of Peace", was a Congregational minister and Welsh Member of Parliament, 1868-88. The son of the Rev...

. He helped found the Peace Society

Peace Society

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a society founded on 14 June 1816 for the promotion of permanent and universal peace; it advocated a gradual, proportionate, and...

. In addition, he was instrumental in the founding of the Morning Star in 1855 as a newspaper through which to promote the Peace Society

Peace Society

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a society founded on 14 June 1816 for the promotion of permanent and universal peace; it advocated a gradual, proportionate, and...

and his other socially progressive ideas.

Personal life

Sturge married, first, in 1834, Eliza, sister of John CropperJohn Cropper

John Cropper was a British philanthropist and abolitionist. A businessman, he was known as "the most generous man in Liverpool".-Business and philanthropy:...

. After her death, in 1846 he married Hannah, daughter of Barnard Dickinson.

Death and memorial

Edgbaston

Edgbaston is an area in the city of Birmingham in England. It is also a formal district, managed by its own district committee. The constituency includes the smaller Edgbaston ward and the wards of Bartley Green, Harborne and Quinton....

, Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

. A memorial to him was unveiled three years later before a crowd of 12,000 on 4 June 1862 at Five Ways

Five Ways, Birmingham

Five Ways is an area of Birmingham, England. It takes its name from a major road junction, now a busy roundabout to the south-west of the city centre which lies at the outward end of Broad Street, where the Birmingham Middle ring road crosses the start of the A456 .-History:The name of Five Ways...

. Standing at the boundary between Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

and Edgbaston

Edgbaston

Edgbaston is an area in the city of Birmingham in England. It is also a formal district, managed by its own district committee. The constituency includes the smaller Edgbaston ward and the wards of Bartley Green, Harborne and Quinton....

, it was sculpted by John Thomas, whom Sir Charles Barry had employed as stone and wood carver on the former King Edward's Grammar School at Five Ways. Thomas had also worked on the Palace of Westminster

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament or Westminster Palace, is the meeting place of the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom—the House of Lords and the House of Commons...

and Balmoral

Balmoral

- Australia :* Balmoral, New South Wales, a locality of Sydney* Balmoral, New South Wales * Balmoral, New South Wales * Balmoral, Queensland* Balmoral, Victoria* Balmoral, Western Australia- Canada :...

, as well as the reliefs on Windsor

Windsor Station

-Australia:* Windsor railway station, Brisbane* Windsor railway station, Sydney* Windsor railway station, Melbourne- United Kingdom :* Windsor & Eton Riverside railway station* Windsor & Eton Central railway station- United States :...

and Euston Station

Euston station

Euston station may refer to one of the following stations in London, United Kingdom:*Euston railway station, a major terminus for trains to the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and part of Scotland...

s.

Sturge is posed as if he were teaching, with his right hand resting on the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

to indicate his strong Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

faith. Lower on the plinth

Plinth

In architecture, a plinth is the base or platform upon which a column, pedestal, statue, monument or structure rests. Gottfried Semper's The Four Elements of Architecture posited that the plinth, the hearth, the roof, and the wall make up all of architectural theory. The plinth usually rests...

, he is flanked by two female allegorical

Allegory

Allegory is a demonstrative form of representation explaining meaning other than the words that are spoken. Allegory communicates its message by means of symbolic figures, actions or symbolic representation...

figures: one representing Peace holds a dove and an olive branch, with a lamb at her feet, symbolic of innocence; and the other, Charity, offers comfort and succour to two Afro-Caribbean infants, recalling the fight and victory over slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. Around the crown of the plinth are inscribed the words "Charity, Temperance and Peace", as well as Sturge's name and his date of death.

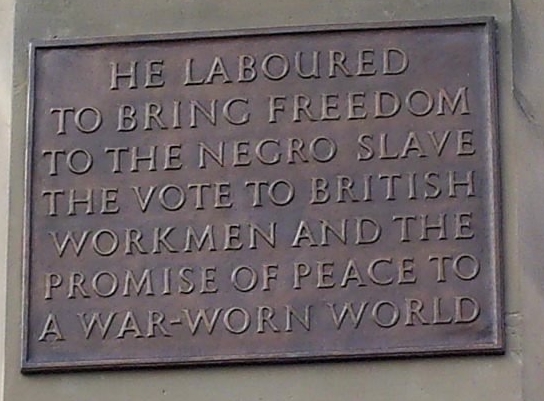

In 1925 a plaque was installed at the memorial to tell passers-by more about its subject. The inscription reads:

The Birmingham Civic Society

The Birmingham Civic Society was founded at an inaugural meeting on 10 June 1918 in The Council House, Birmingham, England and is registered with The Civic Trust. The first President of the Society, the Earl of Plymouth, addressed the assembled Aldermen, Councillors, Architects and other city...

, Birmingham City Council

Birmingham City Council

The Birmingham City Council is the body responsible for the governance of the City of Birmingham in England, which has been a metropolitan district since 1974. It is the most populated local authority in the United Kingdom with, following a reorganisation of boundaries in June 2004, 120 Birmingham...

, and the Sturge family restored the statue for the 200th anniversary of the Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act

The Slave Trade Act was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom passed on 25 March 1807, with the long title "An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade". The original act is in the Parliamentary Archives...

of 1807. The statue is grade II listed.

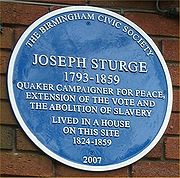

Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event, serving as a historical marker....

(historic marker) was unveiled at the site of his home in Wheeleys Road, Edgbaston.

Further reading

- Richard, Henry (1864), Memoirs of Joseph Sturge, London: Partridge

- Temperley, Howard (1972), British Anti-Slavery 1733-1870, London: Longman

- Pickering, Paul & Tyrell, Alex (2004) Contested Sites: commemoration, memorial & popular politics, pub:Ashgate

- Tyrrell, Richard (1987), Joseph Sturge and the Moral Radical Party in Victorian Britain, London: Helm

External links

- The Joseph Sturge Monument - A photo essay on the history of his statue in Birmingham.

- The Birmingham Civic Society

- Joseph Sturge

----