Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

Encyclopedia

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

, United States.

Beginnings

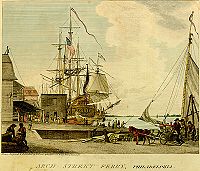

The year of 1793 had been a profitable one for the port city of Philadelphia, experiencing a rising demand for tobacco and sugarcane. The on-going Haitian RevolutionHaitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution was a period of conflict in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which culminated in the elimination of slavery there and the founding of the Haitian republic...

forced many French refugees to flee, and many of them landed in Philadelphia. However, the citizens of the city didn't know that some of the refugees were suffering from yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

, a raging fever that turned its victim's skin and eyes yellow. In what turned out to be one of the most devastating epidemics in U.S. history, the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 killed ten percent of Philadelphia's population in the first month alone.

A source of contention in the Philadelphia College of Physicians was Dr. Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush was a Founding Father of the United States. Rush lived in the state of Pennsylvania and was a physician, writer, educator, humanitarian and a Christian Universalist, as well as the founder of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania....

's claim to having found a cure. Doctors of the time believed in vis medicatrix naturae

Vis medicatrix naturae

Vis medicatrix naturae is the Latin translation of the Greek, νονσων φνσεις ιητροι, a phrase attributed to Hippocrates but which he did not actually use...

, "the healing power of nature." This was the belief that the body would in its own due course rid itself of any illness or poisons and that it was the doctor's job simply to help this natural process along. Rush saw that nothing was coming from this practice and decided more drastic measures needed to be taken. He tried many treatments (with no results) that included: administering shaved tree bark with wine, brandy, and aromatics such as ginger or cinnamon; sweating the fever out by coating a patient's body with a thick salve of herbs and chemicals; and wrapping the whole body in a blanket soaked in warm vinegar. Finally, after hours of reading for an answer, Dr. Rush came upon John Mitchell's published letter concerning a yellow fever outbreak fifty years prior in Virginia. Mitchell noted that the stomach and intestines filled with blood and that these organs had to be emptied at all costs. He urged doctors to be blunt and to forget any "ill-timed scrupulousness about the weakness of the body."

Last used during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, "Ten-and-Ten" was an intense purge of the body produced through administering ten grains of calomel (mercury)

Mercury(I) chloride

Mercury chloride is the chemical compound with the formula Hg2Cl2. Also known as calomel or mercurous chloride, this dense white or yellowish-white, odorless solid is the principal example of a mercury compound...

and ten grains of the cathartic

Cathartic

In medicine, a cathartic is a substance that accelerates defecation. This is in contrast to a laxative, which is a substance which eases defecation, usually by softening feces. It is possible for a substance to be both a laxative and a cathartic...

drug jalap

Jalap

Jalap is a cathartic drug consisting of the tuberous roots of Ipomoea purga, a convolvulaceous plant growing on the eastern declivities of the Sierra Madre Oriental of Mexico at an elevation of 5000 to 8000 ft...

(the poisonous root of a Mexican plant, Ipomoea purga, related to the morning glory

Morning glory

Morning glory is a common name for over 1,000 species of flowering plants in the family Convolvulaceae, whose current taxonomy and systematics is in flux...

, which was dried and powdered before ingesting). Both substances, being highly toxic, would create the desired elimination that Dr. Rush was looking for. To accelerate the process, he increased the dosage to ten-and-fifteen and administered it three times a day, in effect poisoning his patients to rid the body of waste. Rush also believed in bloodletting

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is the withdrawal of often little quantities of blood from a patient to cure or prevent illness and disease. Bloodletting was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily fluid were considered to be "humors" the proper balance of which maintained health...

, as did virtually every doctor of the time. He removed copious amounts of blood from a patient with the thought that it would cleanse the body. Many at the time believed the body held about twenty-five pounds of blood, but in reality, it holds less than half that, and many of Rush's patients passed out because they were bled so radically. However drastic were Rush's methods, he saw signs of improvement, claiming that eight out of ten patients had gotten better with a single treatment, and that the next day nine out of ten were over the fever.

Nevertheless, success came with criticism. Most doctors believed he was poisoning his patients instead of curing them. Dr. Jean Devèze publicly criticized Rush saying: "He, I say, is a scourge more fatal to the human kind than the plague itself would be." Other doctors suggested treatments of their own, but no one claimed to have the cure as fervently as Rush did. He continued to face criticism until he himself fell ill with the fever. He had a servant administer the cure to him and fully recovered within five days. It wasn't until that point that many people sought him out for his cure; afterwards, over one-hundred fifty people came to him for help. Still, most of Philadelphia's physicians condemned his technique, calling him the "Prince of Bleeders."

Re-elevating the morale of the city

Although the College of Physicians came to no agreement about the illness, they did provide a list of precautions and measurements to be delivered to the citizens of Philadelphia. The list included cleaning the streets, hospitalization for victims, avoiding fatigue, limiting the intake of beer and wine, placing patients in airy rooms, removing soiled clothes and linens often, putting strong smelling substances such as vinegar on handkerchiefs to place over the mouth, using gunpowder to purify the air, and to stay away from people with the disease. The list, however, did not offer a cure.In response to the list, the citizens of Philadelphia created a feeling of panic. One citizen, Mathew Carey noted, "Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod." Immediately people began evacuating the city to country homes and relatives far away, leaving behind the poor who could not afford such luxuries. Mayor Clarkson became increasing concerned over this because the poor were swiftly becoming poorer. As the middle and upper class people began closing their shops, many poor people lost their jobs, and could therefore not pay for food, medicine, a physician, or a nurse. A militia company from nearby Fort Mifflin

Fort Mifflin

Fort Mifflin, originally called Fort Island Battery and also known as Mud Island Fort, was commissioned in 1771 and sits on Mud Island on the Delaware River below Philadelphia, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia International Airport...

began hauling a cannon around the streets, firing off gunpowder to calm the citizens that were left in the city. This was just one unsuccessful precaution taken to re-elevate the mood of the city.

Another unsettling fact was the low number of government officials that kept showing up for work. Only ten out of eighteen senators and thirty-six h

ospital turned away fever victims because they feared the disease would spread rampantly through the wards due to the close conditions of the patients and workers. One solution was to turn Ricketts' Circus

John Bill Ricketts

John Bill Ricketts , an Englishman who brought the first modern circus to the United States, began his theatrical career with Hughes Royal Circus in London in the 1780s, and came over from England in 1792 to establish his first circus in Philadelphia.He built a circus building in Philadelphia in...

building into a place for the excess homeless. Seven yellow fever victims were placed in the abandoned Circus and left to die there. The ones that were still alive were only moved when neighbors complained about the smells and sounds, to Bush Hill, an illegally seized building. However, Bush Hill was no better for the victims: it was described as "limited, crude, and insufficient."

theres also a book about it call the yellow fevr of 1793 its a good bok.

Bush Hill

For the majority of the epidemic, Bush Hill remained overcrowded and understaffed. "The sick, the dying, and the dead were indiscriminately mingled together," eyewitness Mathew Carey reported. "The ordure and other evacuations of the sick, were allowed to remain in the most offensive state imaginable… It was, in fact, a great human slaughter-house." It was not until Mayor Clarkson, in despair, organized a committee that the institution changed. Two members, Peter Helm, a barrel maker, and Stephen GirardStephen Girard

Stephen Girard was a French-born, naturalized American, philanthropist and banker. He personally saved the U.S. government from financial collapse during the War of 1812, and became one of the wealthiest men in America, estimated to have been the fourth richest American of all time, based on the...

, a very wealthy merchant and shipowner, decided to volunteer to personally manage the interim hospital.

In days, the hospital was running more smoothly, and the patients' morale increased. The first thing Helm and Girard did was to split up the work. Helm took the chores that were concerned with the outside of the building. He established an area where coffins were to be constructed, provided decent housing for staff members of the mansion, had the barn converted into rooming space for those recovering from illness so that they would not be affected from the newly ill, found sufficient areas for storage supplies, and had the property's water pump repaired so that fresh water would be available to patients for the first time. He also took on the daunting task of creating a system for receiving new patients and effectively carting away the dead.

Stephen Girard took the assignment of making sure everything was running efficiently inside the building. His first action was to clean every room of every floor from top to bottom. He then categorized the one hundred and forty current patients and placed them in separate rooms; the dying in one room, the "very low" in an additional room, and so on. He assigned each room and hallway a nurse, hired the French doctor Jean Devèze, who was critical of Rush, and placed a doorkeeper at the entrance to keep track of entrances as well as to prevent delirious patients from going out. In addition to managing those responsibilities, Girard found the time to personally help the patients, as one bystander describes:

"I even saw one of the diseased...[discharge] the contents of his stomach upon [him]. What did Girard do? ...He wiped the patient's cloaths, comforted [him]...arranged the bed, [and] inspired with courage, by renewing in him the hope that he should recover. ---From him he went to another, that vomited offensive matter that would have disheartened any other than this wonderful man."

Israel Israel

Another prominent figure from Mayor Matthew Clarkson's organization was forty-seven-year-old Israel Israel. A reserved merchant and tavern keeper, Israel became a saint of the epidemic. He was put in charge of many jobs, first to find housing, care, and support for the escalating number of orphans in the city. Not only did he rent a home, hire a matron, and have provisions carted to the door of the new home, but he provided all of these amenities to over one-hundred ninety-two orphans. Israel Israel also went where no sane man would go, to the potter's fieldPotter's field

A potter's field was an American term for a place for the burial of unknown or indigent people. The expression derives from the Bible, referring to a field used for the extraction of potter's clay, which was useless for agriculture but could be used as a burial site.-Origin:The term comes from...

, from which noxious odors were wafting, though many believed it the source of the epidemic; there he inspected burial procedures. He was also the one who arranged for the harvesting of grain at Bush Hill, and headed the Committee of Distribution who handed out food, firewood, and clothes to the city's rising number of disadvantaged families. It was also Israel who went to the Almshouse to persuade the keeper to open its doors to the poor once again.

Germantown

President Washington attempted to return to Philadelphia in early November, but was directed to GermantownGermantown, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Germantown is a neighborhood in the northwest section of the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, about 7–8 miles northwest from the center of the city...

, at that time a town some ten miles outside the city. He first lodged at the Dove House, on the campus of Germantown Academy

Germantown Academy

Germantown Academy is America's oldest nonsectarian day school, founded on December 6, 1759 . Germantown Academy is now a K-12 school in the Philadelphia suburb of Fort Washington, having moved from its original Germantown campus in 1965...

, and then rented the house on Germantown Avenue still known as the "Germantown White House". Members of his cabinet joined him in the suburb, waiting out the epidemic until they could safely return to Philadelphia. Polly Lear, the young wife of his secretary Tobias Lear

Tobias Lear

Tobias Lear is best known as the personal secretary to President George Washington. Lear served Washington from 1784 until the former-President's death in 1799...

, was an early victim.

End to the fever

As November edged closer, frost caused the cases of yellow fever to diminish (until the next summer). People began returning to their homes as the fever subsided, but what they found was a completely changed city. The streets were astonishingly clean; the trash and garbage had been swept away along with the removal of cats, dogs, birds, and pigs. The beggars and homeless children were also nowhere in sight. They found the survivors "exhausted and haggard looking", smelling strongly of vinegar and camphor. The skin of many still had a yellow tinge to it, and those who had taken Rush’s mercury purge had "unsightly black" teeth and were constantly spitting to rid their mouths of the foul taste.Legacy

Everyone's lives were affected by the fever. For instance, Dolley Payne ToddDolley Madison

Dolley Payne Todd Madison was the spouse of the fourth President of the United States, James Madison, and was First Lady of the United States from 1809 to 1817...

's husband and newborn baby died of the fever. She took herself and her two-year-old son to a farm, and even became infected themselves. Then after the fever abated they returned to the city and ran a boarding house. However Dolley did not spend her life living in the past, and eleven months after her husband John Todd's death she remarried a Virginia congressman and future U.S. president, James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

.

The Colonial government also found itself changed, both on the state and colonial level. Because many thought it was unconstitutional to meet outside of Philadelphia (this based on the fear of a future autocratic president, like the king of France at Versailles), the Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

didn't meet in the time of the plague, when its nation needed it the most. To avoid any future problems, congress granted the president the power to move a meeting in a time of grave danger and threat.

Philadelphians' hopes of permanently retaining the national capital were dashed. There were smaller yellow fever outbreaks through the 1790s, and during the summer of 1798 John Adams

John Adams

John Adams was an American lawyer, statesman, diplomat and political theorist. A leading champion of independence in 1776, he was the second President of the United States...

's administration evacuated to Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. As of the 2010 United States Census, Trenton had a population of 84,913...

. As scheduled, the federal government moved to the District of Columbia in November 1800. By then, Philadelphia had also lost its position as the state capital: in 1799, Pennsylvania's legislature moved from Philadelphia to Lancaster

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster is a city in the south-central part of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is the county seat of Lancaster County and one of the older inland cities in the United States, . With a population of 59,322, it ranks eighth in population among Pennsylvania's cities...

, before permanently settling in Harrisburg in 1812.

Transformation also came to the city, where people agreed that foul smells were the cause of disease. Public health codes were strengthened and enforced, and in 1799 the United States' first urban water system, designed by Benjamin Latrobe

Benjamin Latrobe

Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe was a British-born American neoclassical architect best known for his design of the United States Capitol, along with his work on the Baltimore Basilica, the first Roman Catholic Cathedral in the United States...

, was constructed in Philadelphia. Curiously, the water system did indirectly affect the risk of yellow fever, by reducing the barrels and cisterns of standing water in which mosquitoes breed. It encouraged Elizabeth Drinker, one of America's most prominent and faithful diarists, to take a bath after waiting twenty-eight years.

In a later epidemic in 1802, yellow fever shaped the fate of the United States. Napoleon I of France

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

sent thirty-three thousand soldiers to America with the purpose of reinforcing French claims to New Orleans. Twenty-nine thousand of these soldiers died of yellow fever, forcing Napoleon to sell the claims to Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

for unreasonably low prices, saying that they were too difficult to maintain. These claims became the Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

, more than tripling the United States land at the time.

Death total

Since most record keepers of the time, ministers, sextons, and city officials, either fled the city, or became ill that late summer in 1793, no real total of how many deaths occurred is available. However estimates have been produced and put the number between four and five thousand people. Yet even though the total doesn't begin to rival that of the original population of the city, the time span of two months that these deaths were incurred and the fear and panic they created remains unmistakably significant.See also

- Arthur MervynArthur MervynArthur Mervyn is a novel written by Charles Brockden Brown and published in 1799. It was one of Brown's more popular novels, and is in many ways representative of Brown's dark, gothic style and subject matter.-Meeting Mervyn:...

, a novel about the epidemic by Charles Brockden BrownCharles Brockden BrownCharles Brockden Brown , an American novelist, historian, and editor of the Early National period, is generally regarded by scholars as the most ambitious and accomplished US novelist before James Fenimore Cooper...

published in 1799 - Fever 1793Fever 1793Fever, 1793 is a historical novel by Laurie Halse Anderson that was published in 2000. Set during the Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic of 1793, its protagonist and narrator is a teenage girl named Matilda Cook who lives with her hardworking mother, war-fought grandfather, and their ex- slave...

, a historical novel about the epidemics published in 2000 - Philadelphia LazarettoPhiladelphia LazarettoThe Philadelphia Lazaretto was the first quarantine hospital in the United States, built in 1799, in Tinicum Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. The site was originally inhabited by the Lenni Lenape, and then the first Swedish settlers in America...

, built in 1799 in response to the 1793 epidemic - Stubbins FfirthStubbins FfirthStubbins Ffirth was an American trainee doctor notable for his unusual investigations into the cause of yellow fever. He theorized that the disease was not contagious, believing that the drop in cases during winter showed that it was more likely a result of the heat and stresses of the summer months...