.gif)

History of Georgia (U.S. state)

Encyclopedia

The history of Georgia spans pre-Columbian

time to the present day.

, Archaic, Woodland

and Mississippian

.

The Mississippian culture, lasting from 800 to 1500 AD, developed urban societies, distinguished by their construction of truncated earthwork

pyramid mounds, or platform mound

s; as well as their hierarchical chiefdom

s; intensive village-based horticulture

, which enabled the development of more dense populations; and creation of ornate copper

, shell and mica

paraphernalia adorned with a series of motifs known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

(SECC). The largest Mound Builder sites surviving in present-day Georgia are Kolomoki

in Early County

, Etowah

in Bartow County, and Ocmulgee National Monument

in Macon

.

, the historic Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee

and Muskogean-speaking Creek and Yamasee

Indians lived in what is now Georgia. The Cherokee

spread southward along the Ridge and Valley Appalachians, occupying lands reaching to the upper Chattahoochee

, which formed the southern boundary of their lands, stretching all the way to the Ohio River

.

The Creek or Muscogee were a loose confederation of tribes descended from the Mississippian culture

people. They were divided between the Lower Creeks along the Ocmulgee

, Flint

and the lower Chattahoochee

rivers, and the more remote Upper Creeks along the Coosa

and Alabama

rivers. The Yamasee occupied the coastal areas along the Savannah River

.

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León

may have sailed along the coast during his exploration of Florida

. In 1526, Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón

attempted to establish a colony on an island, possibly near St. Catherines Island

.

The French founded the colonial settlement of Charlesfort in 1562 on Parris Island, when Jean Ribault

and his party of French Huguenots settled an area in the Port Royal Sound

area of present-day South Carolina

. Within a year the colony failed. Most of the colonists followed René Goulaine de Laudonnière

south and founded a new outpost called Fort Caroline

in present-day Florida .

Over the next few decade

s, a number of Spanish explorers from Florida

visited the inland

region of present-day Georgia. The local Mississippian culture, described by Hernando de Soto

in 1540, had completely disappeared by 1560. The people may have succumbed to new infectious diseases introduced by the Europeans.

English fur traders from the Province of Carolina

first encountered the Lower Creeks in 1690. The English established a fort at Ocmulgee

. There they traded iron

tools, guns, cloth, and rum for deerskins and Indian slaves captured by warring tribes in regular raids.

The conflict between Spain and Great Britain

over control of Georgia began in earnest in about 1670, when the British colony of South Carolina

was founded just north of the missionary provinces of Guale

and Mocama

, part of Spanish Florida

. Guale and Mocama, today part of Georgia, lay between Carolina's capital, Charles Town

, and Spanish Florida's capital, St. Augustine

. They were subjected to repeated military invasions by both sides.

The Spanish mission system was permanently destroyed by 1704. The coast of future Georgia was occupied by British-allied Yamasee

Indians until they were decimated in the Yamasee War

of 1715–1717. The surviving Yamasee fled to Florida, leaving the coast of Georgia depopulated, making formation of a new British colony possible. A few defeated Yamasee remained and later became known as the Yamacraw

.

English settlement began in the early 1730s after James Oglethorpe

, a Member of Parliament

, promoted the area be colonized with the worthy poor of England, to provide an alternative to the overcrowded debtors' prisons. Oglethorpe and other English philanthropists secured a royal charter

as the Trustees of the colony of Georgia

on June 9, 1732. It is commonly known Georgia was founded as a debtor or penal colony persists due to the numerous English convicts who were sentenced to transportation to Georgia. With the motto, "Not for ourselves, but for others," the Trustees selected colonists for Georgia. On February 12, 1733, the first settlers arrived in the ship Anne, at what was to become the city of Savannah

.

In 1742 the colony was invaded by Spanish forces

during the War of Jenkins' Ear

. Oglethorpe mobilized local forces and defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh

. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

, which ended the war, confirmed the English position in Georgia.

From 1735 to 1750, the trustees of Georgia, unique among Britain's American colonies, prohibited African slavery as a matter of public policy. However, as the growing wealth of the slave-based plantation economy in neighboring South Carolina

demonstrated, slaves were more profitable than other forms of labor available to colonists. Improving economic conditions in Europe led to fewer whites being willing to immigrate as indentured servants. In addition, many of the whites suffered high mortality rates from the climate and diseases of the Low Country.

In 1749, the state overturned its ban on slavery. From 1750 to 1775, planters so rapidly imported slaves that the enslaved population grew from less than 500 to approximately 18,000. Some historians have surmised that the Africans had the knowledge and material techniques to build the elaborate earthworks of dams, banks, and irrigation systems throughout the Low Country that supported rice

and indigo

cultivation; Georgia planters imported slaves chiefly from rice-growing regions of present-day Sierra Leone

, the Gambia

and Angola

. Recent scholarship argues that the Europeans could have developed the rice culture on their own and that African knowledge played a minor role in the success of its cultivation as a commodity crop. Later planters added sugar cane as a crop.

In 1752 Georgia became a royal colony. Planters from South Carolina, wealthier than the original settlers of Georgia, migrated south and soon dominated the colony. They replicated the customs and institutions of the South Carolina Low Country

. Planters had higher rates of absenteeism from their large coastal plantations. They often took their families to the hills during the summer, the "sick season", when the Low Country had high rates of disease.

The pacing and development of large plantations made the Georgia coast society more like that of the West Indies than of Virginia

. There was a higher proportion of African-born slaves, and Africans who came from closely related regions. The slaves of the 'Rice Coast' of South Carolina and Georgia developed the unique Gullah

or Geechee culture (the latter term more common in Georgia), in which important parts of West Africa

n linguistic, religious and cultural heritage were preserved. This culture developed throughout the Low Country and Sea Islands, where enslaved African Americans later worked at cotton plantations. African-American influence was strong on cuisine and music that became integral parts of southern culture.

Georgia was largely untouched by war during much of Britain's involvement in the Seven Years War

– as the colony was located a long distance from Canada and the French-allied Indians. However, in 1762 Georgia was believed to be under threat from a potential Spanish invasion from Florida, although this did not occur by the time peace was signed at the 1763 Treaty of Paris

. During this period the Cherokee Rebellion began.

Governor Wright wrote in 1766 that Georgia had

was popular. But all of the 13 colonies developed the same strong position defending the traditional rights of Englishmen which they feared London was violating. Georgia and the others moved rapidly toward republicanism

which rejected monarchy, aristocracy and corruption, and demanded government based on the will of the people. In particular, they demanded "No taxation without representation

" and rejected the Stamp Act in 1765 and all subsequent royal taxes. More fearsome was the British punishment of Boston after the Boston Tea Party

. Georgians knew their remote coastal location made them vulnerable.

In August 1774 at a general meeting in Savannah

, the people proclaimed, "Protection and allegiance are reciprocal, and under the British Constitution correlative terms; ... the Constitution admits of no taxation without representation." Georgia had few grievances of its own but ideologically supported the patriot cause and expelled the British.

Angered by the news of the battle of Concord, on the eleventh of May 1775, the patriots stormed the royal magazine at Savannah

and carried off its ammunition. The customary celebration of the King's birthday on June 4 was turned into a wild demonstration against the King; a liberty pole was erected. Within a month the patriots completely defied royal authority and set up their own government. In June and July, assemblies at Savannah chose a Council of Safety and a Provincial Congress to take control of the government and cooperate with the other colonies. They started raising troops and prepared for war. "In short my lord," wrote Wright to Lord Dartmouth on September 16, 1775, "the whole Executive Power is Assumed by them, and the King's Governor remains little Else than Nominally so."

In February 1776, Wright fled to a British warship and the patriots controlled all of Georgia. The new Congress adopted "Rules and Regulations" on April 15, 1776, which can be considered the Constitution of 1776. (There never was a Georgia declaration of independence.) Georgia was no longer a colony; it was a state with a weak chief executive, the "President and Commander-in-Chief," who was elected by the Congress for a term of only six months. Archibald Bulloch

, President of the two previous Congresses, was elected first President. He bent his efforts to mobilizing and training the militia. The Constitution of 1777 put power in the hands of the elected House of Assembly, which chose the governor; there was no senate and the franchise was open to nearly all white men.

The new state's exposed seaboard position made it a tempting target for the British Navy. Savannah

was captured by British and Loyalist

forces in 1778, along with some of its hinterland. Enslaved Africans and African Americans chose their independence by escaping to British lines, where they were promised freedom. About one-third of Georgia's 15,000 slaves escaped during the Revolution.

The patriots moved to Augusta

. At the Siege of Savannah

in 1779, American and French troops (the latter including a company of free blacks

from Haiti

) fought unsuccessfully to retake the city. During the final years of the American Revolution, Georgia had a functioning Loyalist colonial government along the coast. Together with New York City, it was the last Loyalist bastion.

An early historian reported:

Georgia ratified the U.S. Constitution on January 2, 1788.

The original eight counties of Georgia were Burke

, Camden

, Chatham

, Effingham

, Glynn

, Liberty

, Richmond

and Wilkes

. Before these counties were created in 1777, Georgia had been divided into local government units called parishes.

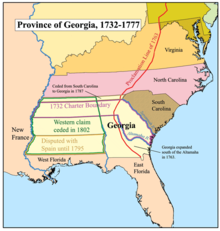

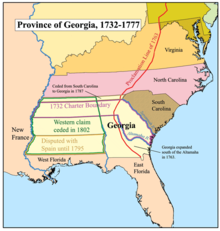

established the eastern boundary of Georgia as the Savannah River

, to Tugalo Lake. Twelve to fourteen miles of land (inhabited at the time by the Cherokee Nation

) separate the lake from the southern boundary of North Carolina. South Carolina ceded its claim to this land (extending all the way to the Pacific Ocean) to the federal government.

Georgia maintained a claim on western land from 31° N to 35° N, the southern part of which overlapped with the Mississippi Territory

created from part of Spanish Florida

in 1798. Georgia ceded its claims in 1802, fixing its present western boundary. In 1804, the federal government added the cession to the Mississippi Territory.

The Treaty of 1816 fixed the present-day boundary between Georgia and South Carolina at the Chattooga River

, proceeding northwest from the lake.

In 1794, Eli Whitney

, a Massachusetts

-born artisan residing in Savannah

, patented sac cotton gin

, mechanizing cotton

production. The Industrial Revolution

had resulted in the mechanized spinning and weaving of cloth in the world’s first factories in the north of England. Fueled by the soaring demands of British textile manufacturers, King Cotton

quickly came to dominate Georgia and the other southern states. Although Congress

banned the slave trade in 1808, Georgia's slave population continued to grow with the importation of slaves from the plantations of the South Carolina Low Country

and Chesapeake

Tidewater, increasing from 149,656 in 1820 to 280,944 in 1840. A small population of free blacks developed, mostly working as artisans. The Georgia legislature unanimously passed a resolution in 1842 declaring that free blacks were not U.S. citizens.

Slaves worked the fields in large cotton plantation

s, and the economy of the state became dependent on the institution of slavery. Requiring little cultivation and easy to transport, cotton proved ideally suited to the inland frontier. The lower Piedmont

or 'Black Belt' counties – comprising the middle third of the state and initially named for the regions distinctively dark and fertile soil – became the site of the largest and most productive cotton plantations.

In 1829, gold was discovered in the north Georgia mountains, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

, the first gold rush

in U.S. history. A Federal mint was established in Dahlonega, Georgia

and continued to operate until 1861. An influx of white settlers pressured the U.S. government to take the land away from the Cherokee

Indians. They owned land, operated their own government with a written constitution, and did not recognize the authority of the state of Georgia.

Please note: In reference to Georgia being the first "gold rush" in U.S. history see wiki pages: "Gold Rush," and "Georgia Gold Rush," both of which state that it was the second gold rush in the U.S. The first having been in North Carolina in 1799,according to other wiki pages.

The dispute culminated in the Indian Removal Act

of 1830, under which all eastern tribes were sent west to Indian reservations in present-day Oklahoma. In Worcester v. Georgia

, the Supreme Court in 1832 ruled that states were not permitted to redraw the boundaries of Indian lands, but President Andrew Jackson

and the state of Georgia ignored the ruling. In 1838, his successor, Martin van Buren

dispatched federal troops to round up the Cherokee and deport them west of the Mississippi

. This forced relocation, known as the Trail of Tears

led to the death of over 4,000 Cherokees.

Growth continued in the Black Belt region. By 1860, the slave population in the Black Belt was three times greater than that of the coastal counties, where rice

remained the principal crop. The upper Piedmont

was settled mainly by white yeoman farmers of English descent. While there were also many smaller cotton plantations, the proportion of slaves was lower in north Georgia than in the coastal

and Black Belt counties, but it still ranged up to 25% of the population. In 1860 in the state as a whole, enslaved African Americans comprised 44% of the population of slightly more than one million.

The proportion of slaves in Georgia was quite big since the cotton is most efficiently grown on large plantations with many slaves rather than on small family farms. The Sokoloff/Engerman (SE) hypothesis predicts that cotton producers with large slave plantations will have a restrictive franchise which has a wealth or literacy requirement for voting. That’s a factor to induce Georgia into Civil War as Southern party to keep their elite rights.

.

in February.

The first major battle in Georgia was a Confederate victory at the Battle of Chickamauga

in 1863—it was the last major Confederate victory in the west. In 1864, William T. Sherman's armies invaded Georgia as part of the Atlanta Campaign

. Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston

fought a series of delaying battles, the largest being the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

, as he tried to delay as long as possible by retreating toward Atlanta. Johnston's replacement, Gen. John Bell Hood

attempted several unsuccessful counterattacks at the Battle of Peachtree Creek

and the Battle of Atlanta

, but Sherman captured the city on September 2, 1864.

After the loss of Atlanta, Governor Brown

withdrew the state's militia from the Confederate forces to harvest crops for the state and the army.

on November 15, en route to Milledgeville

, the state capital, which he reached on November 23, and the port city of Savannah

, which he entered on December 22. His army destroyed a swath of land about 60 miles (96.6 km) across in this campaign, less than 10% of the state. Once Sherman's army passed through, the Confederates regained control. The March is a major part of the state's folk history. The crisis was the setting for Margaret Mitchell

's 1936 novel Gone with the Wind

and the subsequent 1939 film

. One of the last land battles of the Civil War, the Battle of Columbus, Georgia

, was fought on the Georgia-Alabama border.

The memory of Sherman's March became iconic and central to the "Myth of the Lost Cause

." Most important were many "salvation stories" that tell not what Yankee soldiers destroyed, but what was saved by the quick thinking and crafty women on the home front, or perhaps was saved by a Northerners' appreciation of the beauty of homes and the charm of Southern women.

, became the first Confederate to be tried and executed as a war criminal.

In January 1865, William T. Sherman issued Special Field Orders, No. 15 authorizing federal authorities to confiscate abandoned plantations in the Sea Islands

and redistribute land in smaller plots to former slaves, so that they might get a stake in life. Later that year after succeeding Lincoln in the presidency, Andrew Johnson

revoked the order and returned the plantations to their former owners.

After the Civil War, many blacks moved from rural areas to Atlanta to take part in rebuilding the city and railroads, have freedom from the plantation counties, and to set up their own communities. Others migrated away from plantations to towns and worked to reunite their families.

Andrew Johnson

's decision to restore the former Confederate states to the Union without requirements for change to reflect the outcome of the war was criticized by Radical Republicans in Congress. In March 1867, they passed the First Reconstruction Act to place the South under temporary military occupation to help manage the transition to citizenship of freedmen. Along with Alabama

and Florida

, Georgia was included in the Third Military District, under the command of General John Pope

.

To try to ensure the election of loyal governments, Radical Republicans passed an act requiring ex-Confederates to take an ironclad oath

of loyalty or be prevented from voting or holding office for a few years. They were replaced in southern legislatures by a coalition of newly enfranchised freedmen, Northerners (who were called carpetbaggers), and Southerners who were for the Union, also disparagingly called scalawags. The latter were mostly former Whigs

who had opposed secession.

In January 1868, Charles Jenkins

, Georgia's first governor elected after the end of the war, refused to authorize state funds for a racially integrated state constitutional convention. Pope's successor General George Meade dissolved Jenkins' government and replaced it with a military governor to ensure the constitutional convention was held representing all citizens.

This action outraged many white conservatives, already opposed to the Republican administration. Some were already engaged in organized political terrorism and others joined such insurgent paramilitary groups. The Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan

, Nathan Bedford Forrest

, visited Atlanta several times in 1868 to help organize the Klan in Georgia. Political violence increased in the state against freedmen and their allies. The Freedmen's Bureau agents reported 336 cases of murder or assault with intent to kill perpetrated against freedmen across the state from January 1 through November 15 of 1868.

In July 1868, the newly elected General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth Amendment

; a Republican governor, Rufus Bullock

, was inaugurated, and Georgia was readmitted to the Union. The state's Democrats, including former Confederate leaders Robert Toombs

and Howell Cobb

, convened in Atlanta to denounce Reconstruction. Theirs was described as the largest mass rally of whites held in Georgia. In September, white Republicans joined with the Democrats in expelling the thirty-two black legislators from the General Assembly. A week later in the southwest Georgia town of Camilla

, white residents attacked a black Republican rally and killed twelve men.

In 1868, Georgia became the first state in the South to implement the convict lease

system. It made money by leasing out the overwhelmingly black prison population to work for private businesses and citizens. The work force was unprotected and did not receive any income. Railroad companies, mines, turpentine distilleries and other manufacturers, in essence, used unpaid convict labor to hasten industrialization. While the entities employing convicts were legally obliged to provide humane treatment, widespread reports that leased convicts were being overworked, brutally whipped, and killed were completely ignored. Georgia’s incipient capitalists reaped huge profits from this system. The greatest beneficiary was Joseph E. Brown

, whose railroads, coal mines and iron works were all dependent on convict labor. (See next section.)

As whites tried to reestablish social and political dominance in a changed labor market in the midst of a severe agricultural depression, militia and lynch-mob violence directed against freedmen and their allies rose in Georgia and other Confederate states. It was continuation of the Civil War by other means.

These developments led many to call for return of Georgia to military rule, to ensure protection of citizens. Georgia was one of only two ex-Confederate states to vote against Ulysses S. Grant

in the presidential election of 1868. In March 1869 the state legislature defeated ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment.

The same month the U.S. Congress again barred Georgia's representatives from their seats because of election fraud and inequities. This caused the re-imposition of military rule in December 1869. In January 1870, Gen. Alfred H. Terry, the final commanding general of the Third District, purged the General Assembly's of ex-Confederates. He replaced them with the Republican runners-up and reinstated the expelled black legislators. This created a large Republican majority in the legislature.

In February 1870 the newly constituted legislature ratified the Fifteenth Amendment

and chose new Senators to send to Washington. On July 15, Georgia became the last former Confederate state readmitted into the Union. The Democrats subsequently won commanding majorities in both houses of the General Assembly. Under their threat of impeachment, the last Republican governor Rufus Bullock

fled the state.

Under the Reconstruction government, the former state capital of Milledgeville

Under the Reconstruction government, the former state capital of Milledgeville

was replaced by the inland rail terminus of Atlanta. Construction began on a new capitol building

, which was completed by 1889. The population of Atlanta increased rapidly.

Post-Reconstruction Georgia was dominated by the 'Bourbon

Triumvirate' of Joseph E. Brown

, Gen. John B. Gordon and Gen. Alfred H. Colquitt

. Between 1872 and 1890, either Brown or Gordon held one of Georgia's Senate

seats, Colquitt held the other, and, in the major part of that period, either Colquitt

or Gordon occupied the Governor's office. With their appeals to white supremacy, the Democrats effectively monopolized state politics. Colquitt

represented the old planter class; Brown

, head of Western & Atlantic Railroad and one of the states first millionaires, represented the New South

businessmen. Gordon was neither a planter nor a successful businessman, but proved the most skilled politician.

A general in the Army of Northern Virginia

who led the fabled last charge at Appomattox

, Brown was the leader of the Ku Klux Klan

in Georgia. He was the first former Confederate to serve in the U.S. Senate. There he helped write the Compromise of 1877

that ended Reconstruction. A native of northwest Georgia, his popularity impeded the growth of the 'mountain Republicanism' prevalent throughout southern Appalachia

, where slavery had been uncommon and resentment against the planter class widespread.

During the Gilded Age

, Georgia recovered from the devastation of the Civil War and had unprecedented economic growth based in part on development of resources. One of the most enduring products came about in reaction to the age's excesses. In 1885, when Atlanta and Fulton County

enacted prohibition

legislation, a local pharmacist, John Pemberton

invented a new drink. Two years later, after he sold the drink to Asa Candler who promoted it, Coca-Cola

became the state's most famous product.

Henry W. Grady

, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, emerged as the leading spokesman of the 'New South

'. He promoted sectional reconciliation and the region's place in a rapidly industrializing nation. The International Cotton Exposition of 1881

and the Cotton States and International Exposition of 1895

were staged to promote Georgia and the South as textile centers. They attracted mills from New England to build a new economic base in the post-war South by diversifying the region’s agrarian economies. Attracted by low labor costs and the proximity to raw materials, new textile businesses transformed Columbus

and Atlanta, as well as Graniteville

, on the Georgia-South Carolina

border, into textile manufacturing centers.

Due to Georgia's relatively untapped virgin forests, particularly in the thinly populated pine barrens

of the Atlantic Coastal Plain

, logging became a major industry. It supported other new industries, most notably paper mill

s and turpentine

distilling, which, by 1900, made Georgia the leading producer of naval stores. Also important were coal

, granite

and kaolin mining, the latter used in the manufacture of paper, bricks and ceramic piping.

Even after the Democrats gained power, in the volatile 1880s and 1890s the number of lynchings of blacks grew steadily, reaching its height in 1899, when twenty-seven Georgians were killed by lynch mobs. From 1890 to 1900, Georgia averaged more than one mob killing per month. More than 95% of the victims of the 450 lynchings documented between 1882 and 1930 were black. This period corresponded to Georgia's disfranchisement of blacks and many poor whites through changes to its constitution and addition of such requirements as poll taxes, literacy and comprehension tests, and residency requirements. Political violence was used against blacks to reduce voting until they were disfranchised, a situation that prevailed for more than 60 years into the 20th century.

The Cotton States and International Exposition was famous as the occasion of Booker T. Washington

's Atlanta Compromise

. He urged blacks to focus their efforts, not on demands for social equality, but to improve their own conditions by becoming proficient in agriculture, mechanics, and domestic service. He proposed building a broad base within existing conditions. He urged whites to take responsibility to improve social and economic relations between the races. Black leaders such as W. E. B. Du Bois, who supported classical academic standards for education, strongly disagreed with Washington and denounced him for acquiescing to oppression. Du Bois, the most highly educated black man in America, in 1897 joined the faculty of Atlanta University

and taught there for several years. His experience and research in Georgia informed his famous book The Souls of Black Folk.

The black community mobilized quickly to get as much education as possible. Starting from having only a few schools before the Civil War, by the end of the century, the community had seen more than 30,000 teachers trained and put to work in schools across the South for African American children. Often rural schools in Georgia and other states were held only a few months a year because of demands to use children for labor, but parents tried their best. Teaching was highly regarded as a career and seen as a way for talented leaders, both men and women, to help their race.

insisted on Georgia's urban future, the state's economy remained overwhelmingly dependent on cotton. Much of the industrialization that did occur was as a subsidiary of cotton agriculture; many of the state's new textile factories were devoted to the manufacture of simple cotton bags. The price per pound of cotton plummeted from $1 at the end of the Civil War

to an average of 20 cents in the 1870s, nine cents in the 1880s, and seven cents in the 1890s. By 1898, it had fallen to five cents a pound -while costing seven cents to produce. Once-prosperous planters were reduced to fledgling small farmers.

Thousands of freedmen became tenant farmers or sharecroppers rather than hire out to labor gangs. Through the lien system, small-county merchants assumed a central role in cotton production, monopolizing the supply of equipment, fertilizers, seeds and foodstuffs needed to make sharecropping possible. As cotton prices plummeted below production costs, by the 1890s, 80–90% of cotton growers, whether owner or tenant, were in debt to lien merchants.

Indebted Georgia cotton growers responded by embracing the "agrarian radicalism" manifested, successively, in the 1870s with the Granger movement, in the 1880s with the Farmers' Alliance

, and in the 1890s with the Populist Party

. In 1892, Congressman Tom Watson

joined the Populists, becoming the most visible spokesman for their predominately Western Congressional delegation. Southern Populists denounced the convict lease system, while urging white and black small farmers to unite on the basis of shared economic self-interest. They generally refrained from advocating social equality.

In his essay 'The Negro Question in the South,' Watson framed his appeal for a united front between black and white farmers declaring:

"You are kept apart that you may be separately fleeced of your earnings. You are made to hate each other because upon that hatred is rested the keystone of the arch of financial despotism which enslaves you both. You are deceived and blinded that you may not see how this race antagonism perpetuates a monetary system which beggars both."

Southern Populists did not share their Western counterparts' emphasis on Free Silver

and bitterly opposed their desire for fusion with the Democratic Party

. They had faced death threats, mob violence and ballot-box stuffing to challenge the monopoly of their states' Bourbon Democrat

political machines. The merger with the Democratic Party in the 1896 Presidential election dealt a fatal blow to Southern Populism. The Populists nominated Watson as William Jennings Bryan

's vice-president, but Bryan selected New England

industrialist Arthur Sewall

as a concession to Democratic leaders.

Watson

was not reelected. As the Populist Party disintegrated, through his periodical The Jeffersonian, Watson crusaded as a vigorous anti-Semite, anti-Catholic and white supremacist. He attacked the socialism

which had attracted many former Populists. He campaigned with little success for the party's candidate for President in 1904 and 1908. Watson continued to exert influence in Georgia politics, and provided a key endorsement in the gubernatorial campaign of M. Hoke Smith.

's administration, M. Hoke Smith broke with Cleveland because of his support for Bryan. Hoke Smith's tenure as governor was noted for the passage of Jim Crow laws

and the 1908 constitutional amendment that required a person to satisfy qualifications for literacy tests and property ownership for voting. Because a grandfather clause

was used to waive those requirements for most whites, the legislation effectively secured the disfranchisement of African Americans. Georgia's amendment was made following 1898 and 1903 Supreme Court decisions that had upheld similar provisions in the constitutions of Mississippi and Alabama.

The new provisions were devastating for the African American community and poor whites, as losing the ability to register to vote meant they were excluded from serving on juries, as well as losing all representation at local, state and Federal levels. In 1900 African Americans numbered 1,035,037 in Georgia, nearly 47% of the state's population.

Continued litigation by people from Georgia and other states brought some relief, as in the overturning of the grandfather clause in Guinn v. United States

(1915). White-dominated state legislatures and the state Democratic parties quickly responded by creating new barriers to expanded franchise, such as white-only primaries.

In 1934 Georgia passed legislation to impose a poll tax as a voting requirement, a provision upheld in the Supreme Court case of Breedlove v. Suttles (1937), a challenge brought by a poor white man seeking the ability to vote without paying a fee. By 1940 only 20,000 blacks in Georgia managed to register. In 1944 the Supreme Court's decision in Smith v. Allwright

banned white-only primaries, and in 1945 Georgia repealed its poll tax. Black civil rights groups, especially the All-Citizens Registration Committee (ACRC) of Atlanta, moved quickly to register African Americans. By 1947 they had managed to register 125,000 people, 18.8% of those of eligible age.

In 1958 the state passed legislation again making registration more restrictive, by requiring those who were illiterate to answer 20 of 30 questions posed. In rural counties such as Terrell, black voting registration was repressed. After the legislation, although the county was 64% black in population, only 48 blacks managed to register to vote.

All Georgia citizens would not gain full protection for voting again until the mid-1960s, after African-American leadership in the Civil Rights Movement gained passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

to Georgia in the early 20th century. The goal was to modernize the state, increase efficiency, apply scientific methods, promote education and eliminate waste and corruption. Key leaders were governors Joseph M. Terrell

(1902–07) and Hoke Smith

. Terrell pushed through important legislation covering judicial affairs, schools, food and drug regulation, taxation and labor measures. He failed to obtain necessary penal and railroad reforms.

A representative local leader was newspaper editor Thomas Lee Bailey (1865–1945), who used his Cochran Journal to reach out to Bleckley County

, from 1910 to 1925. The paper mirrored Bailey's personality and philosophy for it was folksy, outspoken, and upbeat and covered a variety of local topics. Bailey was a strong advocate for diversified farming, quality education, civic and political reform, and controls on alcohol and gambling.

further west. In 1911, Georgia produced a record 2.8 million bales of cotton. Four years later, the boll weevil arrived in Georgia, and by 1921 reached such epidemic proportions that it destroyed 45% of the states' cotton crop. World War I drove cotton prices to a high of $1 a pound in 1919, but it quickly fell to 10 cents per pound. Landowners ruined by the boll weevil and declining prices expelled their sharecroppers.

for work, better education for their children, and the right to vote From 1910 to 1940 and in a second wave from the 1940s to 1970, more than 6.5 million African Americans left the South for northern and western industrial cities. They rapidly became urbanized and many built successful lives as industrial workers.

and secured a local option law that dried up most of the rural counties. Atlanta and the other cities were wet strongholds.

By 1907 the much more effective Anti-Saloon League

took over from the preachers and women and cut deals with the politicians, such as Hoke Smith. The League pushed through a prohibition law in 1907 but it had with loopholes that allowed men to import whiskey from other states through the mail, and allowed saloons that supposedly sold only non-alcoholic drinks. The drys finally in 1915 passed an ironclad state law that effectively closed nearly all the liquor traffic. Illegal distilling and bootlegging continued, but most Georgians perforce turned to a new concoction invented in Atlanta, Coca-Cola

. Asa Griggs Candler

bought the cola company and with aggressive regional, national and international marketing turned it into one of the largest and most profitable corporations in the New South.

Although middle class women in Atlanta were well-organized supporters of suffrage, the rural areas were hostile. The state legislature ignored efforts to let women vote in local elections, and not only refused to ratify the Federal 19th Amendment, but took pride in being the first to reject it. Nevertheless the Amendment passed and Georgia women gained the right to vote in 1920; black women did not vote until the 1960s.

, accused of raping and murdering a white Irish Catholic employee, thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan. After appeals failed, a lynch mob murdered Frank in 1917. Ringleaders calling themselves 'The Knights of Mary Phagan' included prominent politicians, most notably former Governor Joseph Mackey Brown

. Publisher Watson

played a leading role in instigating the violence with inflammatory newspaper coverage.

Added to rising social tensions from new immigration, urban migration and rapid change, the trial contributed to revival of the Ku Klux Klan

, refounded in a ceremony at Stone Mountain

in November 1915. With Atlanta as its Imperial City, the Klan quickly grew to occupy a powerful role in state and municipal politics. Governor Clifford Walker

, who served from 1923 to 1927, was closely associated with the Klan. By the end of the decade, the organization suffered a number of scandals, internal feuds, and voices raised in opposition. Klan membership in the state declined from a peak of 156,000 in 1925 to 1,400 in 1930.

The Great Depression

Been hard times for both rural and urban Georgia, with farmers and blue-collar workers hit hardest.

Georgia benefited greatly by the New Deal

, which raised cotton prices to $.11 or $.12 a pound, brought rural electrification, and set up a rural and urban work relief programs. Enacted during Roosevelt's first 100 days in office, the Agricultural Adjustment Act

paid farmers to plant less cotton to reduce supply. Between 1933 and 1940, the New Deal brought $250 million to Georgia. Franklin Delano Roosevelt Identified with The hardships of life and Georgia as he repeatedly returned to the 'Little White House

' where he was treated for polio with the therapeutic waters of Warm Springs

.

Roosevelt's proposals were popular among the Georgia congressional delegation, especially the Civilian Conservation Corps

Which put young men on relief to work, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration which supported the price of cotton and peanuts, and the In the work relief programs that spread money across the state. However, the most powerful member of the Georgia delegation, Congressman Eugene Cox, often opposed legislation which favored labor and urban interests, particularly the National Industrial Recovery Administration.

Georgia's powerful governor Eugene Talmadge

(1933–37) disliked Roosevelt and the new deal. He was a former Agriculture Commissioner whose claims to be a 'real dirt farmer' won him the loyalty of his rural constituencies. Talmadge sought to subvert many New Deal programs. Appealing to white supremacy, he denounced New Deal programs that paid black workers wages equal to whites, and attacked what he described as the communist tendencies of the New Deal. In the 1936 election, Talmadge unsuccessfully attempted to run for the Senate, but lost to pro-New Deal incumbent Richard Russell, Jr.

. The candidate he endorsed for Governor was also defeated. Under the pro-New Deal administration of State House speaker E.D. Rivers, by 1940 Georgia led the nation in the number of Rural Electrification Cooperatives and rural public housing projects.

Although re-elected Governor in 1940, Talmadge suffered from a scandal caused by his firing of a dean of the University of Georgia system, on the grounds that he advocated racial equality. This led the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

to withdraw accreditation from the state's white colleges. In 1942, Talmadge was defeated in his bid for reelection. In 1946, he was reelected, in part by opposing a Federal court ruling that invalidated the white primary, but he died before taking office. The administration was often able to circumvent Talmadge's opposition by working with pro-New Deal politicians, most notably Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield

.

Wartime factory production during World War II

lifted Georgia's economy out of recession. Marietta

's Bell Aircraft plant, the principal assembly site for the B-29 Superfortress

bomber, employed some 28,000 people at its peak, Robins Air Field

near Macon

employed some 13,000 civilians; Fort Benning

became the world's largest infantry training school; and newly opened Fort Gordon

became a major deployment center. Shipyards in Savannah

and Brunswick

built many of the Liberty Ship

s used to transport materiel

to the European and Pacific Theaters. Following the cessation of hostilities, the state's urban centers continued to thrive.

In 1946, Georgia became the first state to allow 18-year-olds to vote, and remained the only one to do so before passage of the 26th Amendment

in 1971. (Three other states set the voting age at 19 or 20.) The same year, the Communicable Disease Center, later called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

was founded in Atlanta from staff of the former Malaria Control in War Areas offices. From 1946 to 1955, some 500 new factories were constructed in the state. By 1950, more Georgians were employed in manufacturing than farming.

At the same time, the mechanization of agriculture dramatically reduced the need for farm laborers. It precipitated another wave of urban migration of former sharecroppers and tenant farmers, chiefly to the urban Midwest, West

and Northeast

, but also to the state's own burgeoning urban centers. During the war, Atlanta's Candler Field

was the nation's busiest airport in terms of flight operation. Afterwards Mayor Hartsfield

lobbied successfully to make the city a hub of commercial air travel, based on its strategic location in relation to the nation's major population centers.

In 1960 after waves of migration to the North, African Americans in Georgia declined to 28% of the state's population, a total of 1,122,596 people. Most of those of eligible voting age were still disfranchised. With Atlanta's leadership among educated, middle-class blacks, Georgia became an important battleground in the American Civil Rights Movement

.

The Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education

(1954) was denounced by Governor Marvin Griffin

, who pledged to keep Georgia's schools segregated, "come hell or high water".

Atlanta-born and bred Baptist

minister Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

emerged as a national leader in the Montgomery Bus Boycott

in 1955. The son of a minister, King earned a doctorate from Boston University and was part of the educated middle class that had developed in the strong African-American community of Atlanta. The success of the Montgomery boycott led to King's joining with others to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC) in Atlanta in 1957, to provide political leadership for the Civil Rights Movement across the South. Black churches had long been important centers of their communities. Ministers and their congregations were at the forefront of the civil rights struggle.

In Georgia and elsewhere, tensions over social change broke out into violence. In 1958, a group called the 'Confederate Underground' bombed a Reform Jewish temple in Atlanta

in reaction to Jewish support of the Civil Rights Movement.

The SCLC led a desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia

in 1961. Together with the local police chief's restraint from violence, this campaign's broad focus failed to achieve any dramatic victories. The Albany campaign taught King and the SCLC important lessons which they put to use in the more successful Birmingham campaign

of 1963–64 in Alabama. The leadership of King and his followers led national opinion to turn in favor of the moral position of activists' claiming common civil rights for all citizens. John F. Kennedy

and his brother Bobby prepared and submitted a Civil Rights bill to Congress.

With the cause of African Americans' capturing the support of the nation, in 1964 President Johnson secured passage of the Civil Rights Act

. The following year he secured passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which established protections for voting. African Americans throughout the South quickly registered to vote and began to re-enter the political process, but it took some years for Georgians to elect the first African American to Congress in the 20th century.

Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. testified before Congress in support of the Civil Rights Act, and Governor Carl Sanders

worked with the Kennedy

administration to ensure the state's compliance. Ralph McGill

, editor and syndicated columnist at the Atlanta Constitution, earned both admiration and enmity by writing in support of the Civil Rights Movement. However, the majority of white Georgians continued to oppose integration.

In 1964, Republican Barry Goldwater

won a majority of votes for president in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi, in part because of his opposition to the Civil Rights Act

. In 1968 arch-segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace

won these three states when he ran as an Independent for the Presidency.

In 1966, Lester Maddox

was elected Governor of Georgia. He had gained fame by threatening African-American civil rights demonstrators who attempted to enter his public restaurant. He stubbornly agitated against integration. After the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Gov. Maddox refused to honor the Nobel Prize winner by allowing his body to lie in state at the capitol.

In 1969, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a successful lawsuit against the state that required integration of public schools. In 1970, newly elected Governor Jimmy Carter

declared in his inaugural address that the era of racial segregation had ended.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and Voting Rights Act (1965) enabled African Americans to regain their suffrage and formal political participation. In 1972 Georgians elected Andrew Young

to Congress as the first African American since Reconstruction. He had been one of King

's lieutenants in the movement. In 1973, the city of Atlanta elected Maynard Jackson

as its first African-American mayor.

. The largest in the world, it was designed to accommodate up to 55 million passengers a year. The airport became a major engine for economic growth. With the advantages of cheap real estate, low taxes, anti-union Right-to-work

laws and lax corporate regulations, the Atlanta metropolitan area became a national center of finance

, insurance

, and real estate

companies, as well as the convention and trade show business. As a testament to the city's growing international profile, in 1990 the International Olympic Committee

selected Atlanta as the site of the 1996 Summer Olympics

. Taking advantage of Atlanta's status as a transportation hub, in 1991 UPS

established its headquarters in a suburb. In 1992, construction finished on Bank of America Plaza

, the tallest building in the U.S. outside New York or Chicago.

In reaction to the association of the Democratic Party

with civil rights legislation and Federal involvement on integration , Georgia, along with the rest of the formerly Democratic Solid South

, gradually shifted to support Republican

s, first in presidential elections. Realignment was hastened by the turbulent one-term Presidency of native-son Jimmy Carter

, the popularity of Reagan

and organizational efforts of the Republican Party, and the growth of the Religious Right

.

The Christian Coalition, whose leader, Ralph E. Reed, Jr.

, had close ties to Georgia, mobilized evangelical

and fundamentalist Christian voters in support of Republican candidates during the 1994 midterm elections. Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich

, the acknowledged leader of the Republican Revolution

, was elected Speaker of the House. His seat represented the wealthy northern suburbs of Atlanta. Bob Barr

, another Georgia Republican Congressman, introduced the Defense of Marriage Act

and led the campaign to impeach President Bill Clinton

. Barr later switched his party affiliation to Libertarian

and announced his intention to run for the U.S. presidency on May 12, 2008. On May 25, he was nominated at the Libertarian convention.

Georgia gained notoriety as a center of radical right-wing terrorism. During the 1996 Olympics, after the International Olympic Committee

condemned the anti-homosexuality resolutions passed by suburban Cobb County

, Eric Robert Rudolph

, a militant Christian fundamentalist detonated a bomb

that killed one person and wounded 11. The following year, the Army of God

, to which Rudolph was linked, bombed an Atlanta lesbian nightclub and an abortion clinic.

In this political climate, Georgia's leading Democrat, Governor Zell Miller

(1990–99), shifted to the right. After being appointed to the Senate following the death of Coverdell in 2000, he emerged as a prominent ally of George W. Bush

on the war in Iraq, Social Security privatization

, tax cuts, and opposition to gay marriage. He delivered a controversial keynote speech at the 2004 Republican convention where he endorsed Bush for reelection and denounced his Democratic Party colleagues. In 2002, Georgia elected Sonny Perdue

, the first Republican governor since Reconstruction. He had campaigned against a controversial redesign of the state flag that removed the Confederate battle emblem.

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

time to the present day.

Pre-Columbian

Before European contact, Native American cultures are divided into four lengthy archeological time periods: PaleoPaleo

Paleo, aka David Strackany, is an American singer of folk music who is notable for writing a song every day for 365 days using a "half-size children's guitar" while living out of his car and being essentially homeless...

, Archaic, Woodland

Woodland period

The Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures was from roughly 1000 BCE to 1000 CE in the eastern part of North America. The term "Woodland Period" was introduced in the 1930s as a generic header for prehistoric sites falling between the Archaic hunter-gatherers and the...

and Mississippian

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1500 CE, varying regionally....

.

The Mississippian culture, lasting from 800 to 1500 AD, developed urban societies, distinguished by their construction of truncated earthwork

Earthworks (archaeology)

In archaeology, earthwork is a general term to describe artificial changes in land level. Earthworks are often known colloquially as 'lumps and bumps'. Earthworks can themselves be archaeological features or they can show features beneath the surface...

pyramid mounds, or platform mound

Platform mound

A platform mound is any earthwork or mound intended to support a structure or activity.-Eastern North America:The indigenous peoples of North America built substructure mounds for well over a thousand years starting in the Archaic period and continuing through the Woodland period...

s; as well as their hierarchical chiefdom

Chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political economy that organizes regional populations through a hierarchy of the chief.In anthropological theory, one model of human social development rooted in ideas of cultural evolution describes a chiefdom as a form of social organization more complex than a tribe or a band...

s; intensive village-based horticulture

Horticulture

Horticulture is the industry and science of plant cultivation including the process of preparing soil for the planting of seeds, tubers, or cuttings. Horticulturists work and conduct research in the disciplines of plant propagation and cultivation, crop production, plant breeding and genetic...

, which enabled the development of more dense populations; and creation of ornate copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

, shell and mica

Mica

The mica group of sheet silicate minerals includes several closely related materials having highly perfect basal cleavage. All are monoclinic, with a tendency towards pseudohexagonal crystals, and are similar in chemical composition...

paraphernalia adorned with a series of motifs known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture that coincided with their adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom-level complex social organization from...

(SECC). The largest Mound Builder sites surviving in present-day Georgia are Kolomoki

Kolomoki Mounds Historic Park

The Kolomoki Mounds are the largest and oldest Woodland period mound complex in the Southeastern United States and currently stand in present day Early County, Georgia, near the Chattahoochee River. The mounds were named a National Historic Landmark in 1964...

in Early County

Early County, Georgia

Early County is a county located in the U.S. state of Georgia. It was created on December 15, 1818 and was named for Peter Early. As of 2010, the population is 11,008. The county seat is Blakely.-Geography:...

, Etowah

Etowah Indian Mounds

Etowah Indian Mounds is a archaeological site in Bartow County, Georgia south of Cartersville, in the United States. Built and occupied in three phases, from 1000–1550 CE, the prehistoric site is located on the north shore of the Etowah River. Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site is a designated...

in Bartow County, and Ocmulgee National Monument

Ocmulgee National Monument

Ocmulgee National Monument preserves traces of over ten millennia of Southeastern Native American culture, including major earthworks built more than 1,000 years ago by Mississippian culture peoples: the Great Temple and other ceremonial mounds, a burial mound, and defensive trenches...

in Macon

Macon, Georgia

Macon is a city located in central Georgia, US. Founded at the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is part of the Macon metropolitan area, and the county seat of Bibb County. A small portion of the city extends into Jones County. Macon is the biggest city in central Georgia...

.

European exploration

At the time of European colonization of the AmericasEuropean colonization of the Americas

The start of the European colonization of the Americas is typically dated to 1492. The first Europeans to reach the Americas were the Vikings during the 11th century, who established several colonies in Greenland and one short-lived settlement in present day Newfoundland...

, the historic Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

and Muskogean-speaking Creek and Yamasee

Yamasee

The Yamasee were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans that lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida.-History:...

Indians lived in what is now Georgia. The Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

spread southward along the Ridge and Valley Appalachians, occupying lands reaching to the upper Chattahoochee

Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River flows through or along the borders of the U.S. states of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers and emptying into Apalachicola Bay in the Gulf of...

, which formed the southern boundary of their lands, stretching all the way to the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

.

The Creek or Muscogee were a loose confederation of tribes descended from the Mississippian culture

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1500 CE, varying regionally....

people. They were divided between the Lower Creeks along the Ocmulgee

Ocmulgee River

The Ocmulgee River is a tributary of the Altamaha River, approximately 255 mi long, in the U.S. state of Georgia...

, Flint

Flint River (Georgia)

The Flint River is a river in the U.S. state of Georgia. The river drains of western Georgia, flowing south from the upper Piedmont region south of Atlanta to the wetlands of the Gulf Coastal Plain in the southwestern corner of the state. Along with the Apalachicola and the Chattahoochee rivers,...

and the lower Chattahoochee

Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River flows through or along the borders of the U.S. states of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers and emptying into Apalachicola Bay in the Gulf of...

rivers, and the more remote Upper Creeks along the Coosa

Coosa River

The Coosa River is a tributary of the Alabama River in the U.S. states of Alabama and Georgia. The river is about long altogether.The Coosa River is one of Alabama's most developed rivers...

and Alabama

Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery.The river flows west to Selma, then southwest until, about from Mobile, it unites with the Tombigbee, forming the Mobile and Tensaw rivers, which discharge into...

rivers. The Yamasee occupied the coastal areas along the Savannah River

Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of South Carolina and Georgia. Two tributaries of the Savannah, the Tugaloo River and the Chattooga River, form the northernmost part of the border...

.

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León was a Spanish explorer. He became the first Governor of Puerto Rico by appointment of the Spanish crown. He led the first European expedition to Florida, which he named...

may have sailed along the coast during his exploration of Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

. In 1526, Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón was a Spanish explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, the first European attempt at a settlement in what is now the continental United States...

attempted to establish a colony on an island, possibly near St. Catherines Island

St. Catherines Island

St. Catherines Island, also known as Santa Catalina, is one of the Sea Islands or Golden Isles on the coast of the U.S. state of Georgia, 50 miles south of Savannah in Liberty County. The island is ten miles long and from one to three miles wide, located between St. Catherine's Sound and Sapelo...

.

The French founded the colonial settlement of Charlesfort in 1562 on Parris Island, when Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault was a French naval officer, navigator, and a colonizer of what would become the southeastern United States. He was a major figure in the French attempts to colonize Florida...

and his party of French Huguenots settled an area in the Port Royal Sound

Port Royal Sound

Port Royal Sound is a coastal sound, or inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, located in the Sea Islands region, in Beaufort County in the U.S. state of South Carolina...

area of present-day South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

. Within a year the colony failed. Most of the colonists followed René Goulaine de Laudonnière

René Goulaine de Laudonnière

René Goulaine de Laudonnière was a French Huguenot explorer and the founder of the French colony of Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida...

south and founded a new outpost called Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was the first French colony in the present-day United States. Established in what is now Jacksonville, Florida, on June 22, 1564, under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière, it was intended as a refuge for the Huguenots. It lasted one year before being obliterated by the...

in present-day Florida .

Over the next few decade

Decade

A decade is a period of 10 years. The word is derived from the Ancient Greek dekas which means ten. This etymology is sometime confused with the Latin decas and dies , which is not correct....

s, a number of Spanish explorers from Florida

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida refers to the Spanish territory of Florida, which formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and the Spanish Empire. Originally extending over what is now the southeastern United States, but with no defined boundaries, la Florida was a component of...

visited the inland

Inland

Inland is an area of land away from the coast or shore line. It usually refers to the interior part of a country or region.Inland may refer to:* Inland Fräkne Hundred, a hundred of Bohuslän in Sweden...

region of present-day Georgia. The local Mississippian culture, described by Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (explorer)

Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who, while leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States, was the first European documented to have crossed the Mississippi River....

in 1540, had completely disappeared by 1560. The people may have succumbed to new infectious diseases introduced by the Europeans.

English fur traders from the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina

The Province of Carolina, originally chartered in 1629, was an English and later British colony of North America. Because the original Heath charter was unrealized and was ruled invalid, a new charter was issued to a group of eight English noblemen, the Lords Proprietors, in 1663...

first encountered the Lower Creeks in 1690. The English established a fort at Ocmulgee

Ocmulgee National Monument

Ocmulgee National Monument preserves traces of over ten millennia of Southeastern Native American culture, including major earthworks built more than 1,000 years ago by Mississippian culture peoples: the Great Temple and other ceremonial mounds, a burial mound, and defensive trenches...

. There they traded iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

tools, guns, cloth, and rum for deerskins and Indian slaves captured by warring tribes in regular raids.

British colony

The conflict between Spain and Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

over control of Georgia began in earnest in about 1670, when the British colony of South Carolina

Province of Carolina

The Province of Carolina, originally chartered in 1629, was an English and later British colony of North America. Because the original Heath charter was unrealized and was ruled invalid, a new charter was issued to a group of eight English noblemen, the Lords Proprietors, in 1663...

was founded just north of the missionary provinces of Guale

Guale

Guale was an historic Native American chiefdom along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. Spanish Florida established its Roman Catholic missionary system in the chiefdom in the late 16th century. During the late 17th century and early 18th century, Guale society was shattered...

and Mocama

Mocama

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Their territory extended from about the Altamaha River in...

, part of Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida refers to the Spanish territory of Florida, which formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and the Spanish Empire. Originally extending over what is now the southeastern United States, but with no defined boundaries, la Florida was a component of...

. Guale and Mocama, today part of Georgia, lay between Carolina's capital, Charles Town

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

, and Spanish Florida's capital, St. Augustine

St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine is a city in the northeast section of Florida and the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida, United States. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorer and admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city and port in the continental United...

. They were subjected to repeated military invasions by both sides.

The Spanish mission system was permanently destroyed by 1704. The coast of future Georgia was occupied by British-allied Yamasee

Yamasee

The Yamasee were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans that lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida.-History:...

Indians until they were decimated in the Yamasee War

Yamasee War

The Yamasee War was a conflict between British settlers of colonial South Carolina and various Native American Indian tribes, including the Yamasee, Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Catawba, Apalachee, Apalachicola, Yuchi, Savannah River Shawnee, Congaree, Waxhaw, Pee Dee, Cape Fear, Cheraw, and...

of 1715–1717. The surviving Yamasee fled to Florida, leaving the coast of Georgia depopulated, making formation of a new British colony possible. A few defeated Yamasee remained and later became known as the Yamacraw

Yamacraw

The Yamacraw were a Native American tribe which settled parts of Georgia, specifically around the future site of the city of Savannah.- History :...

.

English settlement began in the early 1730s after James Oglethorpe

James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe was a British general, member of Parliament, philanthropist, and founder of the colony of Georgia...

, a Member of Parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

, promoted the area be colonized with the worthy poor of England, to provide an alternative to the overcrowded debtors' prisons. Oglethorpe and other English philanthropists secured a royal charter

Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal document issued by a monarch as letters patent, granting a right or power to an individual or a body corporate. They were, and are still, used to establish significant organizations such as cities or universities. Charters should be distinguished from warrants and...

as the Trustees of the colony of Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

on June 9, 1732. It is commonly known Georgia was founded as a debtor or penal colony persists due to the numerous English convicts who were sentenced to transportation to Georgia. With the motto, "Not for ourselves, but for others," the Trustees selected colonists for Georgia. On February 12, 1733, the first settlers arrived in the ship Anne, at what was to become the city of Savannah

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah is the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. Established in 1733, the city of Savannah was the colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. Today Savannah is an industrial center and an important...

.

In 1742 the colony was invaded by Spanish forces

Invasion of Georgia (1742)

The 1742 Invasion of Georgia saw a Spanish military force invade and attempt to occupy the British colony of Georgia as part of the War of Jenkins' Ear. Local British forces under the command of the Governor James Oglethorpe rallied and defeated the Spaniards at the Battle of Bloody Marsh and the...

during the War of Jenkins' Ear

War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear was a conflict between Great Britain and Spain that lasted from 1739 to 1748, with major operations largely ended by 1742. Its unusual name, coined by Thomas Carlyle in 1858, relates to Robert Jenkins, captain of a British merchant ship, who exhibited his severed ear in...

. Oglethorpe mobilized local forces and defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh

Battle of Bloody Marsh

The Battle of Bloody Marsh took place on July 18, 1742 between Spanish and British forces, and the latter were victorious. Part of the War of Jenkin's Ear, the battle was for control of the road between the British forts of Frederica and St. Simons, to control St. Simons Island and the forts'...

. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748 ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled at the Imperial Free City of Aachen—Aix-la-Chapelle in French—in the west of the Holy Roman Empire, on 24 April 1748...

, which ended the war, confirmed the English position in Georgia.

From 1735 to 1750, the trustees of Georgia, unique among Britain's American colonies, prohibited African slavery as a matter of public policy. However, as the growing wealth of the slave-based plantation economy in neighboring South Carolina

South Carolina Low Country

The Lowcountry is a geographic and cultural region located along South Carolina's coast. The region includes the South Carolina Sea Islands...

demonstrated, slaves were more profitable than other forms of labor available to colonists. Improving economic conditions in Europe led to fewer whites being willing to immigrate as indentured servants. In addition, many of the whites suffered high mortality rates from the climate and diseases of the Low Country.

In 1749, the state overturned its ban on slavery. From 1750 to 1775, planters so rapidly imported slaves that the enslaved population grew from less than 500 to approximately 18,000. Some historians have surmised that the Africans had the knowledge and material techniques to build the elaborate earthworks of dams, banks, and irrigation systems throughout the Low Country that supported rice

Rice

Rice is the seed of the monocot plants Oryza sativa or Oryza glaberrima . As a cereal grain, it is the most important staple food for a large part of the world's human population, especially in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and the West Indies...

and indigo

Indigo

Indigo is a color named after the purple dye derived from the plant Indigofera tinctoria and related species. The color is placed on the electromagnetic spectrum between about 420 and 450 nm in wavelength, placing it between blue and violet...

cultivation; Georgia planters imported slaves chiefly from rice-growing regions of present-day Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone , officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Guinea to the north and east, Liberia to the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west and southwest. Sierra Leone covers a total area of and has an estimated population between 5.4 and 6.4...

, the Gambia

The Gambia

The Republic of The Gambia, commonly referred to as The Gambia, or Gambia , is a country in West Africa. Gambia is the smallest country on mainland Africa, surrounded by Senegal except for a short coastline on the Atlantic Ocean in the west....

and Angola

Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola , is a country in south-central Africa bordered by Namibia on the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the north, and Zambia on the east; its west coast is on the Atlantic Ocean with Luanda as its capital city...

. Recent scholarship argues that the Europeans could have developed the rice culture on their own and that African knowledge played a minor role in the success of its cultivation as a commodity crop. Later planters added sugar cane as a crop.

In 1752 Georgia became a royal colony. Planters from South Carolina, wealthier than the original settlers of Georgia, migrated south and soon dominated the colony. They replicated the customs and institutions of the South Carolina Low Country

South Carolina Low Country

The Lowcountry is a geographic and cultural region located along South Carolina's coast. The region includes the South Carolina Sea Islands...

. Planters had higher rates of absenteeism from their large coastal plantations. They often took their families to the hills during the summer, the "sick season", when the Low Country had high rates of disease.

The pacing and development of large plantations made the Georgia coast society more like that of the West Indies than of Virginia

Virginia