Ronald Reagan

Encyclopedia

Ronald Wilson Reagan (ˈrɒnld ˈwɪlsn ˈreɪɡən; February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was the 40th President of the United States

(1981–1989), the 33rd Governor of California

(1967–1975) and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor.

Reagan was born in Tampico, Illinois

and raised in Dixon

. He was educated at Eureka College

, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and sociology

. Upon his graduation, Reagan first moved to Iowa

to work as a radio broadcaster and then in 1937 to Los Angeles, where he began a career as an actor, first in films and later television. Some of his most notable films are in Knute Rockne, All American

, Kings Row

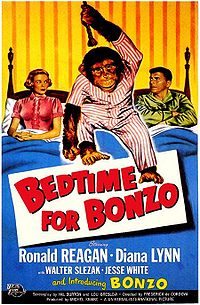

, and Bedtime for Bonzo

. Reagan served as president of the Screen Actors Guild

, and later spokesman for General Electric

; his start in politics occurred during his work for GE.

Originally a member of the Democratic Party

, he ceased supporting or endorsing Democratic Party

candidates for political office around 1952, and eventually switched officially to the Republican Party

in 1962. After delivering a rousing speech

in support of Barry Goldwater

's presidential candidacy in 1964, he was persuaded to seek the California governorship, winning two years later

and again in 1970

. He was defeated in his run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1968

as well as 1976

, but won both the nomination and election in 1980

, defeating incumbent Jimmy Carter

.

As president, Reagan implemented sweeping new political and economic initiatives. His supply-side economic

policies, dubbed "Reaganomics

", advocated reducing tax rates to spur economic growth, controlling the money supply to reduce inflation, deregulation of the economy, and reducing government spending. In his first term he survived an assassination attempt

, took a hard line against labor unions, and ordered an invasion of Grenada

. He was reelected in a landslide in 1984

, proclaiming that it was "Morning in America

". His second term was primarily marked by foreign matters, such as the ending of the Cold War

, the 1986 bombing of Libya, and the revelation of the Iran-Contra affair

. Publicly describing the Soviet Union as an "evil empire

", he supported anti-communist movements worldwide and spent his first term forgoing the strategy of détente

by ordering a massive military buildup in an arms race

with the USSR. Reagan negotiated with General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Mikhail Gorbachev

, culminating in the INF Treaty and the decrease of both countries' nuclear arsenals.

Reagan left office in 1989. In 1994, the former president disclosed that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease

earlier in the year; he died ten years later

at the age of 93. He ranks highly in public opinion polls of U.S. Presidents and is credited for generating an ideological renaissance on the American political right.

Ronald Wilson Reagan was born in an apartment on the second floor of a commercial building in Tampico, Illinois on February 6, 1911, to Jack Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was born in an apartment on the second floor of a commercial building in Tampico, Illinois on February 6, 1911, to Jack Reagan

and Nelle Wilson Reagan

. Reagan's father was a salesman and a storyteller, the grandson of Irish Catholic

immigrants from County Tipperary

while his mother had Scots

-English

ancestors. Reagan had one sibling, his older brother, Neil

(1908–1996), who became an advertising executive. As a boy, Reagan's father nicknamed his son "Dutch", due to his "fat little Dutchman"-like appearance, and his "Dutchboy" haircut; the nickname stuck with him throughout his youth. Reagan's family briefly lived in several towns and cities in Illinois, including Monmouth

, Galesburg

and Chicago

, until 1919, when they returned to Tampico and lived above the H.C. Pitney Variety Store. After his election as president, residing in the upstairs White House private quarters, Reagan would quip that he was "living above the store again".

According to Paul Kengor

, author of God and Ronald Reagan, Reagan had a particularly strong faith in the goodness of people, which stemmed from the optimistic faith of his mother, Nelle, and the Disciples of Christ faith, which he was baptized into in 1922. For the time, Reagan was unusual in his opposition to racial discrimination, and recalled a time in Dixon

when the local inn would not allow black people

to stay there. Reagan brought them back to his house, where his mother invited them to stay the night and have breakfast the next morning.

Following the closure of the Pitney Store in late 1920, the Reagans moved to Dixon; the midwestern "small universe" had a lasting impression on Reagan. He attended Dixon High School

, where he developed interests in acting, sports, and storytelling. His first job was as a lifeguard at the Rock River in Lowell Park, near Dixon, in 1927. Reagan performed 77 rescues as a lifeguard, noting that he notched a mark on a wooden log for every life he saved. Reagan attended Eureka College

, where he became a member of the Tau Kappa Epsilon

fraternity, and majored in economics and sociology. He developed a reputation as a jack of all trades, excelling in campus politics, sports and theater. He was a member of the football team, captain of the swim team and was elected student body president. As student president, Reagan notably led a student revolt against the college president after he tried to cut back the faculty.

at Des Moines

, Iowa. He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Officers Reserve Corps of the Cavalry on May 25, 1937.

Reagan was ordered to active duty for the first time on April 18, 1942. Due to his nearsightedness, he was classified for limited service only, which excluded him from serving overseas. His first assignment was at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation at Fort Mason

, California, as a liaison officer of the Port and Transportation Office. Upon the approval of the Army Air Force (AAF), he applied for a transfer from the Cavalry to the AAF on May 15, 1942, and was assigned to AAF Public Relations and subsequently to the First Motion Picture Unit

(officially, the "18th AAF Base Unit") in Culver City

, California. On January 14, 1943 he was promoted to First Lieutenant and was sent to the Provisional Task Force Show Unit of This Is The Army at Burbank

, California. He returned to the First Motion Picture Unit after completing this duty and was promoted to Captain on July 22, 1943.

In January 1944, Captain Reagan was ordered to temporary duty in New York City to participate in the opening of the sixth War Loan Drive. He was re-assigned to the First Motion Picture Unit on November 14, 1944, where he remained until the end of World War II. He was recommended for promotion to Major on February 2, 1945, but this recommendation was disapproved on July 17 of that year. He returned to Fort MacArthur

, California, where he was separated from active duty on December 9, 1945. By the end of the war, his units had produced some 400 training films for the AAF.

After graduating from Eureka in 1932, Reagan drove himself to Iowa, where he auditioned for a job at many small-town radio stations. The University of Iowa

After graduating from Eureka in 1932, Reagan drove himself to Iowa, where he auditioned for a job at many small-town radio stations. The University of Iowa

hired him to broadcast home football games for the Hawkeyes

. He was paid $10 per game. Soon after, a staff announcer's job opened at radio station WOC in Davenport

, and Reagan was hired, now earning $100 per month. Aided by his persuasive voice, he moved to WHO

radio in Des Moines as an announcer for Chicago Cubs

baseball games. His specialty was creating play-by-play accounts of games that the station received by wire.

While traveling with the Cubs in California, Reagan took a screen test in 1937 that led to a seven-year contract with Warner Brothers

studios. He spent the first few years of his Hollywood career in the "B film

" unit, where, Reagan joked, the producers "didn't want them good, they wanted them Thursday". While sometimes overshadowed by other actors, Reagan's screen performances did receive many good reviews.

His first screen credit was the starring role in the 1937 movie Love Is on the Air

His first screen credit was the starring role in the 1937 movie Love Is on the Air

, and by the end of 1939 he had already appeared in 19 films, including Dark Victory

. Before the film Santa Fe Trail

in 1940, he played the role of George "The Gipper" Gipp

in the film Knute Rockne, All American

; from it, he acquired the lifelong nickname "the Gipper". Reagan's favorite acting role was as a double amputee in 1942's Kings Row

, in which he recites the line, "Where's the rest of me?", later used as the title of his 1965 autobiography. Many film critics considered Kings Row to be his best movie, though the film was condemned by New York Times critic Bosley Crowther

.

Reagan called Kings Row the film that "made me a star". However, he was unable to capitalize on his success because he was ordered to active duty with the U.S. Army at San Francisco two months after its release, and never regained "star" status in motion pictures. In the post-war era, after being separated from almost four years of World War II stateside service with the 1st Motion Picture Unit in December 1945, Reagan co-starred in such films as, The Voice of the Turtle, John Loves Mary

Reagan called Kings Row the film that "made me a star". However, he was unable to capitalize on his success because he was ordered to active duty with the U.S. Army at San Francisco two months after its release, and never regained "star" status in motion pictures. In the post-war era, after being separated from almost four years of World War II stateside service with the 1st Motion Picture Unit in December 1945, Reagan co-starred in such films as, The Voice of the Turtle, John Loves Mary

, The Hasty Heart

, Bedtime for Bonzo

, Cattle Queen of Montana

, Tennessee's Partner

, Hellcats of the Navy

and The Killers

(his final film) in a 1964 remake.

to answer his fan mail. She would hand-write letters and sign his name as if he had written the letters himself. Mrs. Reagan would sign her actor-son's name on photographs and even on membership cards in the Ronald Reagan Fan Club. The article "Devoted Mother, Devoted Son" in the January/February 1985 issue of The Pen & Quill

, journal of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club, compares the handwriting of mother and son, pointing out the differences, and also reveals that Reagan was paying his mother $75.00 a week.

Reagan was first elected to the Board of Directors of the Screen Actors Guild

Reagan was first elected to the Board of Directors of the Screen Actors Guild

in 1941, serving as an alternate. Following World War II, he resumed service and became 3rd vice-president in 1946. The adoption of conflict-of-interest bylaws in 1947 led the SAG president and six board members to resign; Reagan was nominated in a special election for the position of president and subsequently elected. He would subsequently be chosen by the membership to seven additional one-year terms, from 1947 to 1952 and in 1959. Reagan led SAG through eventful years that were marked by labor-management disputes, the Taft-Hartley Act

, House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) hearings and the Hollywood blacklist

era.

Amid the Red Scare

in the late 1940s, Reagan provided the FBI with names of actors whom he believed to be communist sympathizers within the motion picture industry. Reagan testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee on the subject as well. A fervent anti-communist, he reaffirmed his commitment to democratic principles, stating, "I never as a citizen want to see our country become urged, by either fear or resentment of this group, that we ever compromise with any of our democratic principles through that fear or resentment."

Though an early critic of television, Reagan landed fewer film roles in the late 1950s and decided to join the medium. He was hired as the host of General Electric Theater

, a series of weekly dramas that became very popular. His contract required him to tour GE plants sixteen weeks out of the year, often demanding of him fourteen speeches per day. He earned approximately $125,000 per year (about $1.07 million in 2010 dollars) in this role. His final work as a professional actor was as host and performer from 1964 to 1965 on the television series Death Valley Days

. Reagan and Nancy Davis appeared together several times, including an episode of GE Theater in 1958 called A Turkey for the President.

with actress Jane Wyman

(1917–2007). They were engaged at the Chicago Theatre

, and married on January 26, 1940, at the Wee Kirk o' the Heather church

in Glendale

, California. Together they had two biological children, Maureen

(1941–2001) and Christine (who was born in 1947 but only lived one day), and adopted a third, Michael

(born 1945). Following arguments about Reagan's political ambitions, Wyman filed for divorce in 1948, citing a distraction due to her husband's Screen Actors Guild union duties; the divorce was finalized in 1949. He is the only US president to have been divorced.

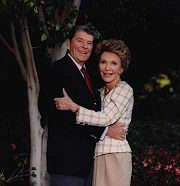

Reagan met actress Nancy Davis

Reagan met actress Nancy Davis

(born 1921) in 1949 after she contacted him in his capacity as president of the Screen Actors Guild to help her with issues regarding her name appearing on a communist blacklist in Hollywood (she had been mistaken for another Nancy Davis). She described their meeting by saying, "I don't know if it was exactly love at first sight, but it was pretty close." They were engaged at Chasen's

restaurant in Los Angeles and were married on March 4, 1952, at the Little Brown Church in the San Fernando Valley

. Actor William Holden

served as best man at the ceremony. They had two children: Patti

(born October 21, 1952) and Ron

(born May 20, 1958).

Observers described the Reagans' relationship as close, real and intimate. During his presidency they were reported as frequently displaying their affection for one another; one press secretary said, "They never took each other for granted. They never stopped courting." He often called her "Mommy" she called him "Ronnie". He once wrote to her, "Whatever I treasure and enjoy ... all would be without meaning if I didn’t have you." When he was in the hospital in 1981, she slept with one of his shirts to be comforted by his scent. In a letter to U.S. citizens written in 1994, Reagan wrote "I have recently been told that I am one of the millions of Americans who will be afflicted with Alzheimer's disease

.... I only wish there was some way I could spare Nancy from this painful experience," and in 1998, while Reagan was stricken by Alzheimer's, Nancy told Vanity Fair

, "Our relationship is very special. We were very much in love and still are. When I say my life began with Ronnie, well, it's true. It did. I can't imagine life without him."

, admirer of Franklin D. Roosevelt

, and an active supporter of New Deal policies

. In the early 1950s, as his relationship with Republican actress Nancy Davis grew, he shifted to the right and, while remaining a Democrat, endorsed the presidential candidacies of Dwight D. Eisenhower

in 1952 and 1956 as well as Richard Nixon

in 1960. The last time Reagan actively supported a Democratic candidate was in 1950 when he helped Helen Gahagan Douglas in her unsuccessful Senate campaign against Richard Nixon. After being hired in 1954 to host the General Electric Theater, a TV drama series, Reagan soon began to embrace the conservative views of the sponsoring company's officials. His many GE speeches—which he wrote himself—were non-partisan but carried a conservative, pro-business message; he was influenced by Lemuel Boulware

, a senior GE executive. Boulware, known for his tough stance against unions and his innovative strategies to win over workers, championed the core tenets of modern American conservatism: free markets, anticommunism, lower taxes, and limited government. Eventually, the ratings for Reagan's show fell off and GE dropped Reagan in 1962. In August of that year Reagan formally switched to the Republican Party

, stating, "I didn't leave the Democratic Party. The party left me."

Reagan opposed certain civil rights legislation, saying "If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house, it is his right to do so". He later reversed his opposition to voting rights and fair housing laws. He strongly denied having racist motives. When legislation that would become Medicare

was introduced in 1961, Reagan created a recording for the American Medical Association

warning that such legislation would mean the end of freedom in America. Reagan said that if his listeners did not write letters to prevent it, "we will awake to find that we have socialism. And if you don't do this, and if I don't do it, one of these days, you and I are going to spend our sunset years telling our children, and our children's children, what it once was like in America when men were free."

Reagan endorsed the campaign of conservative presidential contender Barry Goldwater

in 1964. Speaking for Goldwater, Reagan stressed his belief in the importance of smaller government. He revealed his ideological motivation in a famed speech delivered on October 27, 1964: "The Founding Fathers

knew a government can't control the economy without controlling people. And they knew when a government sets out to do that, it must use force and coercion to achieve its purpose. So we have come to a time for choosing." This "Time for Choosing

" speech raised $1 million for Goldwater's campaign and is considered the event that launched Reagan's political career.

Reagan was a Life Member of the National Rifle Association

.

California Republicans were impressed with Reagan's political views and charisma after his "Time for Choosing" speech, and nominated him for Governor of California

California Republicans were impressed with Reagan's political views and charisma after his "Time for Choosing" speech, and nominated him for Governor of California

in 1966. In Reagan's campaign, he emphasized two main themes: "to send the welfare bums back to work," and, in reference to burgeoning anti-war and anti-establishment student protests

at the University of California at Berkeley, "to clean up the mess at Berkeley." He was elected, defeating two-term governor Edmund G. "Pat" Brown

, and was sworn in on January 2, 1967. In his first term, he froze government hiring and approved tax hikes to balance the budget.

Shortly after the beginning of his term, Reagan tested the presidential waters in 1968

as part of a "Stop Nixon" movement, hoping to cut into Nixon's Southern support and be a compromise candidate if neither Nixon nor second-place Nelson Rockefeller

received enough delegates to win on the first ballot at the Republican convention

. However, by the time of the convention Nixon had 692 delegate votes, 25 more than he needed to secure the nomination, followed by Rockefeller with Reagan in third place.

Reagan was involved in high-profile conflicts with the protest movements of the era. On May 15, 1969, during the People's Park protests at UC Berkeley, Reagan sent the California Highway Patrol

and other officers to quell the protests, in an incident that became known as "Bloody Thursday", resulting in the death of student James Rector and the blinding of carpenter Alan Blanchard. Reagan then called out 2,200 state National Guard

troops to occupy the city of Berkeley for two weeks in order to crack down on the protesters. A year after "Bloody Thursday", Reagan responded to questions about campus protest movements saying, "If it takes a bloodbath, let's get it over with. No more appeasement." When the Symbionese Liberation Army

kidnapped Patty Hearst

in Berkeley and demanded the distribution of food to the poor, Reagan joked, "It's just too bad we can't have an epidemic of botulism

."

Early in 1967, the national debate on abortion was beginning. Democratic California state senator Anthony Beilenson introduced the "Therapeutic Abortion Act," in an effort to reduce the number of "back-room abortions" performed in California. The State Legislature sent the bill to Reagan's desk where, after many days of indecision, he signed it. About two million abortions would be performed as a result, most because of a provision in the bill allowing abortions for the well-being of the mother. Reagan had been in office for only four months when he signed the bill, and stated that had he been more experienced as governor, it would not have been signed. After he recognized what he called the "consequences" of the bill, he announced that he was pro-life

Early in 1967, the national debate on abortion was beginning. Democratic California state senator Anthony Beilenson introduced the "Therapeutic Abortion Act," in an effort to reduce the number of "back-room abortions" performed in California. The State Legislature sent the bill to Reagan's desk where, after many days of indecision, he signed it. About two million abortions would be performed as a result, most because of a provision in the bill allowing abortions for the well-being of the mother. Reagan had been in office for only four months when he signed the bill, and stated that had he been more experienced as governor, it would not have been signed. After he recognized what he called the "consequences" of the bill, he announced that he was pro-life

. He maintained that position later in his political career, writing extensively about abortion.

Despite an unsuccessful attempt to recall him in 1968, Reagan was re-elected in 1970, defeating "Big Daddy" Jesse Unruh. He chose not to seek a third term in the following election cycle. One of Reagan's greatest frustrations in office concerned capital punishment, which he strongly supported. His efforts to enforce the state's laws in this area were thwarted when the Supreme Court of California

issued its People v. Anderson

decision, which invalidated all death sentences issued in California prior to 1972, though the decision was later overturned by a constitutional amendment. The only execution during Reagan's governorship was on April 12, 1967, when Aaron Mitchell's sentence was carried out by the state in San Quentin's gas chamber.

In 1969, Reagan, as Governor, signed the Family Law Act which was the first no fault divorce legislation in the United States.

Reagan's terms as governor helped to shape the policies he would pursue in his later political career as president. By campaigning on a platform of sending "the welfare bums back to work," he spoke out against the idea of the welfare state. He also strongly advocated the Republican ideal of less government regulation of the economy, including that of undue federal taxation.

Reagan did not seek re-election to a third term as governor in 1974 and was succeeded by Democratic California Secretary of State

Jerry Brown

on January 6, 1975.

In 1976, Reagan challenged incumbent President Gerald Ford

In 1976, Reagan challenged incumbent President Gerald Ford

in a bid to become the Republican Party's candidate for president. Reagan soon established himself as the conservative candidate with the support of like-minded organizations such as the American Conservative Union

which became key components of his political base, while President Ford was considered a more moderate Republican.

Reagan's campaign relied on a strategy crafted by campaign manager John Sears of winning a few primaries early to damage the inevitability of Ford's likely nomination. Reagan won North Carolina, Texas, and California, but the strategy failed, as he ended up losing New Hampshire, Florida, and his native Illinois. The Texas campaign lent renewed hope to Reagan, when he swept all ninety-six delegates chosen in the May 1 primary, with four more awaiting at the state convention. Much of the credit for that victory came from the work of three co-chairmen, including Ernest Angelo

, the mayor of Midland

, and Ray Barnhart

of Houston, whom President Reagan tapped in 1981 as director of the Federal Highway Administration

.

However, as the GOP convention

neared, Ford appeared close to victory. Acknowledging his party's moderate wing, Reagan chose moderate Senator Richard Schweiker

of Pennsylvania as his running mate

if nominated. Nonetheless, Ford prevailed with 1,187 delegates to Reagan's 1,070. Ford would go on to lose the 1976 Presidential election

to the Democrat Jimmy Carter

.

Reagan's concession speech emphasized the dangers of nuclear war and the threat posed by the Soviet Union. Though he lost the nomination, he received 307 write-in votes in New Hampshire, 388 votes as an Independent on Wyoming's ballot, and a single electoral vote from a faithless elector

in the November election from the state of Washington, which Ford had won over Democratic challenger Jimmy Carter

.

The 1980 presidential campaign between Reagan and incumbent President Jimmy Carter

was conducted during domestic concerns and the ongoing Iran hostage crisis

. His campaign stressed some of his fundamental principles: lower taxes to stimulate the economy, less government interference in people's lives, states' rights

, a strong national defense, and restoring the U.S. Dollar to a gold standard

.

Reagan launched his campaign by declaring "I believe in states' rights," in Philadelphia, Mississippi

, known at the time for the murder of three civil rights workers who had been trying to register African-Americans to vote during the civil rights movement. After receiving the Republican nomination, Reagan selected one of his primary opponents, George H.W. Bush, to be his running mate. His showing in the October televised debate

boosted his campaign. Reagan won the election, carrying 44 states with 489 electoral votes to 49 electoral votes for Carter (representing six states and Washington, D.C.). Reagan received 50.7% of the popular vote while Carter took 41%, and Independent John B. Anderson

(a liberal Republican) received 6.7%. Republicans captured the Senate

for the first time since 1952, and gained 34 House seats

, but the Democrats retained a majority.

During the presidential campaign, questions were raised by reporters on Reagan's stance on the Briggs Initiative, also known as Proposition 6, a ballot initiative in Reagan's home state of California where he was governor, which would have banned gays, lesbians, and supporters of LGBT rights from working in public schools in California. His opposition to the initiative was instrumental in its landslide defeat by Californian voters. Reagan published an editorial in which he stated "homosexuality is not a contagious disease like the measles..." and that prevailing scientific opinion was that a child's sexual orientation cannot be influenced by someone else.

. Termed the Reagan Revolution, his presidency would reinvigorate American morale and reduce the people's reliance upon government. As president, Reagan kept a series of diaries in which he commented on daily occurrences of his presidency and his views on the issues of the day. The diaries were published in May 2007 in the bestselling book, The Reagan Diaries

.

To date, Reagan is the oldest man elected to the office of the presidency (at 69). In his first inaugural address on January 20, 1981, which Reagan himself wrote, he addressed the country's economic malaise arguing: "In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem."

To date, Reagan is the oldest man elected to the office of the presidency (at 69). In his first inaugural address on January 20, 1981, which Reagan himself wrote, he addressed the country's economic malaise arguing: "In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem."

The Reagan Presidency began in a dramatic manner; as Reagan was giving his inaugural address, 52 U.S. hostages, held by Iran for 444 days

were set free.

, Washington police officer Thomas Delahanty, and Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy were struck by gunfire from would-be assassin John Hinckley, Jr.

outside the Washington Hilton Hotel

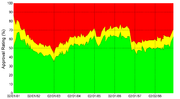

. Although "close to death" during surgery, Reagan recovered and was released from the hospital on April 11, becoming the first serving U.S. President to survive being shot in an assassination attempt. The attempt had great influence on Reagan's popularity; polls indicated his approval rating to be around 73%. Reagan believed that God had spared his life so that he might go on to fulfill a greater purpose.

During Jimmy Carter

During Jimmy Carter

's last year in office (1980), inflation averaged 12.5%, compared to 4.4% during Reagan's last year in office (1988). During Reagan's administration, the unemployment rate declined from 7.1% to 5.5%, with the average annual rate hitting highs of 9.7% in 1982 and 9.6% in 1983, averaging 7.5% over the eight years.

Reagan implemented policies based on supply-side economics

and advocated a classical liberal

and laissez-faire

philosophy, seeking to stimulate the economy with large, across-the-board tax cuts. He also supported returning the U.S. to some sort of gold standard

, and successfully urged Congress to establish the U.S. Gold Commission to study how one could be implemented. Citing the economic theories of Arthur Laffer

, Reagan promoted the proposed tax cuts as potentially stimulating the economy enough to expand the tax base, offsetting the revenue loss due to reduced rates of taxation, a theory that entered political discussion as the Laffer curve

. Reaganomics was the subject of debate with supporters pointing to improvements in certain key economic indicators as evidence of success, and critics pointing to large increases in federal budget deficits and the national debt. His policy of "peace through strength

" (also described as "firm but fair") resulted in a record peacetime defense buildup including a 40% real increase in defense spending between 1981 and 1985.

During Reagan's presidency, federal income tax rates were lowered significantly with the signing of the bipartisan Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 which lowered the top marginal tax bracket from 70% to 50% and the lowest bracket from 14% to 11%, however other tax increases signed by Reagan ensured that tax revenues over his two terms were 18.2% of GDP as compared to 18.1% over the past 40 years. Then, in 1982 the Job Training Partnership Act of 1982

was signed into law, initiating one of the nation's first public/private partnerships and a major part of the president's job creation program. Reagan's Assistant Secretary of Labor and Chief of Staff, Al Angrisani

, was a primary architect of the bill. The Tax Reform Act of 1986

, another bipartisan effort championed by Reagan, reduced the top rate further to 28% while raising the bottom bracket from 11% to 15% and reducing the quantity of brackets to 4. Conversely, Congress passed and Reagan signed into law tax increases of some nature in every year from 1981 to 1987 to continue funding such government programs as TEFRA, Social Security, and the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984. Despite the fact that TEFRA was the "largest peacetime tax increase in American history," Reagan is better known for his tax cuts and lower-taxes philosophy. Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth recovered strongly after the early 1980s recession

ended in 1982, and grew during his eight years in office at an annual rate of 3.85% per year. Unemployment peaked at 10.8% monthly rate in December 1982—higher than any time since the Great Depression—then dropped during the rest of Reagan's presidency. Sixteen million new jobs were created, while inflation significantly decreased. The net effect of all Reagan-era tax bills was a 1% decrease in government revenues when compared to Treasury Department revenue estimates from the Administration's first post-enactment January budgets. However, federal Income Tax receipts increased from 1980 to 1989, rising from $308.7Bn to $549.0Bn.

During the Reagan Administration, federal receipts grew at an average rate of 8.2% (2.5% attributed to higher Social Security receipts), and federal outlays grew at an annual rate of 7.1%. Reagan also revised the tax code

with the bipartisan Tax Reform Act of 1986

.

Reagan's policies proposed that economic growth would occur when marginal tax rates were low enough to spur investment, which would then lead to increased economic growth, higher employment and wages. Critics labeled this "trickle-down economics

"—the belief that tax policies that benefit the wealthy will create a "trickle-down" effect to the poor. Questions arose whether Reagan's policies benefited the wealthy more than those living in poverty, and many poor and minority citizens viewed Reagan as indifferent to their struggles. These views were exacerbated by the fact that Reagan's economic regimen included freezing the minimum wage

at $3.35 an hour, slashing federal assistance to local governments by 60 percent, cutting the budget for public housing

and Section 8 rent subsidies

in half, and eliminating the antipoverty Community Development Block Grant

program.

Further following his less-government intervention views, Reagan cut the budgets of non-military programs including Medicaid

, food stamps, federal education programs and the EPA

. While he protected entitlement programs, such as Social Security

and Medicare

, his administration attempted to purge many people with disabilities from the Social Security disability rolls.

The administration's stance toward the Savings and Loan industry contributed to the Savings and loan crisis

. It is also suggested, by a minority of Reaganomics critics, that the policies partially influenced the stock market crash of 1987

, but there is no consensus regarding a single source for the crash. In order to cover newly spawned federal budget deficits, the United States borrowed heavily both domestically and abroad, raising the national debt from $997 billion to $2.85 trillion. Reagan described the new debt as the "greatest disappointment" of his presidency.

He reappointed Paul Volcker

as Chairman of the Federal Reserve

, and in 1987 he appointed monetarist Alan Greenspan

to succeed him. Reagan ended the price controls

on domestic oil which had contributed to energy crises in the early 1970s. The price of oil subsequently dropped, and the 1980s did not see the fuel shortages that the 1970s had. Reagan also fulfilled a 1980 campaign promise to repeal the Windfall profit tax in 1988, which had previously increased dependence on foreign oil. Some economists, such as Nobel Prize winners Milton Friedman

and Robert A. Mundell, argue that Reagan's tax policies invigorated America's economy and contributed to the economic boom of the 1990s. Other economists, such as Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow

, argue that the deficits were a major reason why Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, reneged on a campaign promise

and raised taxes.

During Reagan's presidency, a program was initiated within the US intelligence community to ensure America's economic strength. The program, Project Socrates

, developed and demonstrated the means required for the US to generate and lead the next evolutionary leap in technology acquisition and utilization for a competitive advantage—automated innovation. To ensure that the US acquired the maximum benefit from automated innovation, President Reagan, during his second term, had an executive order drafted to create a new Federal agency to implement the Project Socrates results on a nation-wide basis. However, President Reagan's term came to end before the executive order could be coordinated and signed, and the incoming Bush administration, labeling Project Socrates as "industrial policy", had it terminated.

American peacekeeping forces in Beirut

American peacekeeping forces in Beirut

, a part of a multinational force

during the Lebanese Civil War

who had been earlier deployed by Reagan, were attacked on October 23, 1983. The Beirut barracks bombing

resulted in the deaths of 241 American servicemen and the wounding of more than 60 others by a suicide truck bomber. Reagan sent a White House team to the site four days later, led by his Vice President, George H.W. Bush. Reagan called the attack "despicable," pledged to keep a military force in Lebanon, and planned to target the Sheik Abdullah barracks in Baalbek

, Lebanon, training ground for Hezbollah fighters, but the mission was later aborted. On February 7, 1984, President Reagan ordered the Marines to begin withdrawal from Lebanon. In April 1984, as his keynote address to the 20,000 attendees of the Rev. Jerry Falwell

's "Baptist Fundamentalism '84" convention in Washington, D.C., he read a first hand account of the bombing, written by Navy Chaplain (Rabbi) Arnold Resnicoff

, who had been asked to write the report by Bush and his team. Osama bin Laden

would later cite Reagan's withdrawal of forces as a sign of American weakness.

On October 25, 1983, only two days later, Reagan ordered U.S. forces to invade Grenada, code named Operation Urgent Fury, where a 1979 coup d'état had established an independent non-aligned

Marxist-Leninist

government. A formal appeal from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) led to the intervention of U.S. forces; President Reagan also cited an allegedly regional threat posed by a Soviet-Cuban military build-up in the Caribbean and concern for the safety of several hundred American medical students at St. George's University as adequate reasons to invade. Operation Urgent Fury was the first major military operation conducted by U.S. forces since the Vietnam War

, several days of fighting commenced, resulting in a U.S. victory, with 19 American fatalities and 116 wounded American soldiers. In mid-December, after a new government was appointed by the Governor-General, U.S. forces withdrew.

which began in 1979 following the Soviet war in Afghanistan

. Reagan ordered a massive buildup of the United States Armed Forces

and implemented new policies towards the Soviet Union: reviving the B-1 Lancer

program that had been canceled by the Carter administration, and producing the MX missile. In response to Soviet deployment of the SS-20, Reagan oversaw NATO's deployment of the Pershing missile

in West Germany.

Together with the United Kingdom's prime minister Margaret Thatcher

, Reagan denounced the Soviet Union in ideological terms. In a famous address on June 8, 1982 to the British Parliament in the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster

, Reagan said, "the forward march of freedom and democracy will leave Marxism-Leninism

on the ash-heap of history." On March 3, 1983, he predicted that communism would collapse, stating, "Communism is another sad, bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages even now are being written." In a speech to the National Association of Evangelicals

on March 8, 1983, Reagan called the Soviet Union "an evil empire

".

After Soviet fighters downed Korean Air Lines Flight 007 near Moneron Island

on September 1, 1983, carrying 269 people, including Georgia congressman Larry McDonald

, Reagan labeled the act a "massacre" and declared that the Soviets had turned "against the world and the moral precepts which guide human relations among people everywhere". The Reagan administration responded to the incident by suspending all Soviet passenger air service to the United States, and dropped several agreements being negotiated with the Soviets, wounding them financially. As result of the shootdown, and the cause of KAL 007's going astray thought to be inadequacies related to its navigational system, Reagan announced on September 16, 1983 that the Global Positioning System

would be made available for civilian use, free of charge, once completed in order to avert similar navigational errors in future.

Under a policy that came to be known as the Reagan Doctrine

, Reagan and his administration also provided overt and covert aid

to anti-communist resistance movements

in an effort to "rollback

" Soviet-backed communist governments in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Reagan deployed the CIA's Special Activities Division

to Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were instrumental in training, equipping and leading Mujaheddin forces against the Soviet Army

. President Reagan's Covert Action program has been given credit for assisting in ending the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, though the US funded armaments introduced then would later pose a threat to US troops in the 2000s war in Afghanistan

. However, in a break from the Carter policy of arming Taiwan under the Taiwan Relations Act

. Reagan also agreed with the communist government in China to reduce the sale of arms to Taiwan

.

In March 1983, Reagan introduced the Strategic Defense Initiative

, a defense project that would have used ground and space-based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic nuclear ballistic missiles. Reagan believed that this defense shield could make nuclear war impossible, but disbelief that the technology could ever work led opponents to dub SDI "Star Wars" and argue that the technological objective was unattainable. The Soviets became concerned about the possible effects SDI would have; leader Yuri Andropov

said it would put "the entire world in jeopardy". For those reasons, David Gergen

, former aide to President Reagan, believes that in retrospect, SDI hastened the end of the Cold War.

Critics labeled Reagan's foreign policies as aggressive, imperialistic, and chided them as "warmongering," though they were supported by leading American conservatives who argued that they were necessary to protect U.S. security interests. A reformer, Mikhail Gorbachev

, would later rise to power in the Soviet Union in 1985, implementing new policies for openness and reform that were called glasnost

and perestroika

.

Reagan accepted the Republican nomination in Dallas, Texas, on a wave of positive feeling. He proclaimed that it was "morning again in America

Reagan accepted the Republican nomination in Dallas, Texas, on a wave of positive feeling. He proclaimed that it was "morning again in America

," regarding the recovering economy and the dominating performance by the U.S. athletes at the 1984 Summer Olympics

, among other things. He became the first American president to open an Olympic Games held in the United States.

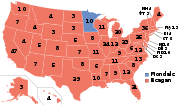

Reagan's opponent in the 1984 presidential election was former Vice President Walter Mondale

. With questions about Reagan's age, and a weak performance in the first presidential debate, his ability to perform the duties of president for another term was questioned. His apparent confused and forgetful behavior was evident to his supporters; they had previously known him clever and witty. Rumors began to circulate that he had Alzheimer's disease. Reagan rebounded in the second debate, and confronted questions about his age, quipping, "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience," which generated applause and laughter, even from Mondale himself.

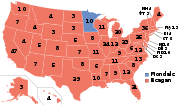

That November, Reagan was re-elected, winning 49 of 50 states. The president's overwhelming victory saw Mondale carry only his home state of Minnesota (by 3800 votes) and the District of Columbia. Reagan won a record 525 electoral votes, the most of any candidate in United States history, and received 58.8% of the popular vote to Mondale's 40.6%.

. Because January 20 fell on a Sunday, a public celebration was not held but took place in the Capitol Rotunda the following day. January 21 was one of the coldest days on record

in Washington, D.C.; due to poor weather, inaugural celebrations were held inside the Capitol.

In the summer of 1982, several conservative activists, including Howard Phillips of The Conservative Caucus

In the summer of 1982, several conservative activists, including Howard Phillips of The Conservative Caucus

and Clymer Wright

of Houston, Texas, had urged Reagan to remove his White House chief of staff

James Baker

, also of Houston, on grounds that Baker, a political intimate of George H. W. Bush, was undercutting conservative initiatives in the administration. Not only did Reagan reject the Wright-Phillips request, but in 1985, after his reelection, he named Baker as United States Secretary of the Treasury

, at Baker's request in a job-swap with then Secretary Donald T. Regan, a former Merrill Lynch

officer who became chief of staff. Reagan also rebuked Wright and Phillips for having waged a "campaign of sabotage" against Baker.

In 1985, Reagan visited a German military cemetery in Bitburg

to lay a wreath with West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl

. It was determined that the cemetery held the graves of forty-nine members of the Waffen-SS

. Reagan issued a statement that called the Nazi soldiers buried in that cemetery as themselves "victims," a designation which ignited a stir over whether Reagan had equated the SS men to victims of the Holocaust

; Patrick J. Buchanan, Reagan's Director of Communications, argued that the president did not equate the SS members with the actual Holocaust. Now strongly urged to cancel the visit, the president responded that it would be wrong to back down on a promise he had made to Chancellor Kohl. He ultimately attended the ceremony where two military generals laid a wreath.

The disintegration of the Space Shuttle Challenger

on January 28, 1986 proved a pivotal moment in Reagan's presidency. All seven astronaut

s aboard were killed. On the night of the disaster, Reagan delivered a speech written by Peggy Noonan

in which he said (quoting the first and last lines of John Gillespie Magee's 1941 poem High Flight):

In 1986, Reagan signed a drug enforcement bill that budgeted $1.7 billion to fund the War on Drugs and specified a mandatory minimum penalty for drug offenses. The bill was criticized for promoting significant racial disparities in the prison population and critics also charged that the policies did little to reduce the availability of drugs on the street, while resulting in a great financial burden for America. Defenders of the effort point to success in reducing rates of adolescent drug use. First Lady

Nancy Reagan

made the War on Drugs her main priority by founding the "Just Say No

" drug awareness campaign, which aimed to discourage children and teenagers from engaging in recreational drug use

by offering various ways of saying "no". Mrs. Reagan traveled to 65 cities in 33 states, raising awareness about the dangers of drugs including alcohol.

in 1981; by 1982, Gaddafi was considered by the CIA to be, along with USSR leader Leonid Brezhnev and Cuban leader Fidel Castro, part of a group known as the "unholy trinity" and was also labeled as "our international public enemy number one" by a CIA official. These tensions were later revived in early April 1986, when a bomb exploded in a Berlin discothèque, resulting in the injury of 63 American military personnel and death of one serviceman. Stating that there was "irrefutable proof" that Libya had directed the "terrorist bombing", Reagan authorized the use of force against the country. In the late evening of April 15, 1986, the U.S. launched a series of air strikes on ground targets in Libya. The UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

allowed the US Air Force to use Britain's air bases to launch the attack, on the justification that the UK was supporting America's right to self-defense under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. The attack was designed to halt Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

's "ability to export terrorism", offering him "incentives and reasons to alter his criminal behavior". The president addressed the nation from the Oval Office

after the attacks had commenced, stating, "When our citizens are attacked or abused anywhere in the world on the direct orders of hostile regimes, we will respond so long as I'm in this office." As early as 1981, Reagan had referred to Gaddafi as "the mad dog of the Middle East" and considered him to be public enemy number one.

in 1986. The act made it illegal to knowingly hire or recruit illegal immigrants, required employers to attest to their employees' immigration status, and granted amnesty

to approximately 3 million illegal immigrants who entered the United States prior to January 1, 1982, and had lived in the country continuously. Critics argue that the employer sanctions were without teeth and failed to stem illegal immigration. Upon signing the act at a ceremony held beside the newly refurbished Statue of Liberty

, Reagan said, "The legalization provisions in this act will go far to improve the lives of a class of individuals who now must hide in the shadows, without access to many of the benefits of a free and open society. Very soon many of these men and women will be able to step into the sunlight and, ultimately, if they choose, they may become Americans." Reagan also said, "The employer sanctions program is the keystone and major element. It will remove the incentive for illegal immigration by eliminating the job opportunities which draw illegal aliens here."

in Nicaragua, which had been specifically outlawed by an act of Congress. The Iran-Contra affair

became the largest political scandal in the United States during the 1980s. The International Court of Justice

, whose jurisdiction to decide the case was disputed, ruled that the U.S. had violated international law in Nicaragua due to its obligations not to intervene in the affairs of other states.

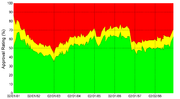

President Reagan professed ignorance of the plot's existence. He appointed two Republicans and one Democrat (John Tower

, Brent Scowcroft

and Edmund Muskie

, known as the "Tower Commission") to investigate the scandal. The commission could not find direct evidence that Reagan had prior knowledge of the program, but criticized him heavily for his disengagement from managing his staff, making the diversion of funds possible. A separate report by Congress concluded that "If the president did not know what his national security advisers were doing, he should have." Reagan's popularity declined from 67 percent to 46 percent in less than a week, the greatest and quickest decline ever for a president. The scandal resulted in fourteen indictments within Reagan's staff, and eleven convictions.

Many Central Americans criticize Reagan for his support of the Contras, calling him an anti-communist zealot, blinded to human rights abuses, while others say he "saved Central America". Daniel Ortega

, Sandinistan

and current president of Nicaragua, said that he hoped God would forgive Reagan for his "dirty war against Nicaragua". In 1986 the USA was found guilty by the International Court of Justice

(World Court) of war crimes against Nicaragua.

By the early 1980s, the USSR had built up a military arsenal and army surpassing that of the United States. Previously, the U.S. had relied on the qualitative superiority of its weapons to essentially frighten the Soviets, but the gap had been narrowed. After President Reagan's military buildup, the Soviet Union did not further dramatically build up its military; the enormous military expenses, in combination with collectivized agriculture and inefficient planned manufacturing

By the early 1980s, the USSR had built up a military arsenal and army surpassing that of the United States. Previously, the U.S. had relied on the qualitative superiority of its weapons to essentially frighten the Soviets, but the gap had been narrowed. After President Reagan's military buildup, the Soviet Union did not further dramatically build up its military; the enormous military expenses, in combination with collectivized agriculture and inefficient planned manufacturing

, were a heavy burden for the Soviet economy

. At the same time, the Reagan Administration persuaded Saudi Arabia to increase oil production, which resulted in a drop of oil prices in 1985 to one-third of the previous level; oil was the main source of Soviet export revenues. These factors gradually brought the Soviet economy to a stagnant state during Gorbachev

's tenure.

Reagan recognized the change in the direction of the Soviet leadership with Mikhail Gorbachev

, and shifted to diplomacy, with a view to encourage the Soviet leader to pursue substantial arms agreements. Reagan's personal mission was to achieve "a world free of nuclear weapons," which he regarded as "totally irrational, totally inhumane, good for nothing but killing, possibly destructive of life on earth and civilization." He was able to start discussions on nuclear disarmament with General Secretary Gorbachev. Gorbachev and Reagan held four summit conferences between 1985 and 1988: the first

in Geneva, Switzerland, the second

in Reykjavík

, Iceland

, the third in Washington, D.C., and the fourth in Moscow. Reagan believed that if he could persuade the Soviets to allow for more democracy and free speech, this would lead to reform and the end of Communism.

Speaking at the Berlin Wall

on June 12, 1987, Reagan challenged Gorbachev to go further, saying:

Prior to Gorbachev visiting Washington, D.C., for the third summit in 1987, the Soviet leader announced his intention to pursue significant arms agreements. The timing of the announcement led Western diplomats to contend that Gorbachev was offering major concessions to the U.S. on the levels of conventional forces, nuclear weapons, and policy in Eastern Europe. He and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at the White House, which eliminated an entire class of nuclear weapons. The two leaders laid the framework for the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START I

Prior to Gorbachev visiting Washington, D.C., for the third summit in 1987, the Soviet leader announced his intention to pursue significant arms agreements. The timing of the announcement led Western diplomats to contend that Gorbachev was offering major concessions to the U.S. on the levels of conventional forces, nuclear weapons, and policy in Eastern Europe. He and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at the White House, which eliminated an entire class of nuclear weapons. The two leaders laid the framework for the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START I

; Reagan insisted that the name of the treaty be changed from Strategic Arms Limitation Talks to Strategic Arms Reduction Talks.

When Reagan visited Moscow for the fourth summit in 1988, he was viewed as a celebrity by the Soviets. A journalist asked the president if he still considered the Soviet Union the evil empire. "No," he replied, "I was talking about another time, another era." At Gorbachev's request, Reagan gave a speech on free markets at the Moscow State University

. In his autobiography, An American Life

, Reagan expressed his optimism about the new direction that they charted and his warm feelings for Gorbachev. In November 1989, the Berlin Wall

was torn down, the Cold War was officially declared over at a Malta Summit on December 3, 1989 and two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed.

, first in his right ear and later in his left as well. His decision to go public in 1983 regarding his wearing the small, audio-amplifying device boosted their sales.

On July 13, 1985, Reagan underwent surgery at Bethesda Naval Hospital to remove cancerous polyps from his colon. He relinquished presidential power to the Vice President for eight hours in a similar procedure as outlined in the 25th Amendment

, which he specifically avoided invoking. The surgery lasted just under three hours and was successful. Reagan resumed the powers of the presidency later that day. In August of that year, he underwent an operation to remove skin cancer cells from his nose. In October, additional skin cancer cells were detected on his nose and removed.

In January 1987, Reagan underwent surgery for an enlarged prostate

which caused further worries about his health. No cancerous growths were found, however, and he was not sedated during the operation. In July of that year, aged 76, he underwent a third skin cancer operation on his nose.

to fill the vacancy created by the retirement of Justice Potter Stewart

. In his second term, Reagan elevated William Rehnquist

to succeed Warren Burger as Chief Justice

, and named Antonin Scalia

to fill the vacant seat. Reagan nominated conservative jurist Robert Bork

to the high court in 1987. Senator Ted Kennedy

, a Democrat of Massachusetts, strongly condemned Bork, and great controversy ensued. Bork's nomination was rejected 58–42. Reagan then nominated Douglas Ginsburg

, but Ginsburg withdrew his name from consideration after coming under fire for his cannabis

use. Anthony Kennedy

was eventually confirmed in his place. Along with his three Supreme Court appointments, Reagan appointed 83 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals

, and 290 judges to the United States district courts.

Reagan also nominated Vaughn R. Walker

, who would later be revealed to be the earliest known gay federal judge, to the United States District Court for the Central District of California

. However, the nomination stalled in the Senate, and Walker was not confirmed until he was renominated by Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush.

After leaving office in 1989, the Reagans purchased a home in Bel Air, Los Angeles in addition to the Reagan Ranch

After leaving office in 1989, the Reagans purchased a home in Bel Air, Los Angeles in addition to the Reagan Ranch

in Santa Barbara

. They regularly attended Bel Air Presbyterian Church

and occasionally made appearances on behalf of the Republican Party; Reagan delivered a well-received speech at the 1992 Republican National Convention. Previously on November 4, 1991, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

was dedicated and opened to the public. At the dedication ceremonies, five presidents were in attendance, as well as six first ladies, marking the first time five presidents were gathered in the same location. Reagan continued publicly to speak in favor of a line-item veto

; the Brady Bill; a constitutional amendment

requiring a balanced budget

; and the repeal of the 22nd Amendment, which prohibits anyone from serving more than two terms as president. In 1992 Reagan established the Ronald Reagan Freedom Award

with the newly formed Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. His final public speech was on February 3, 1994 during a tribute to him in Washington, D.C., and his last major public appearance was at the funeral

of Richard Nixon

on April 27, 1994.

, an incurable neurological disorder which destroys brain cells and ultimately causes death. In November he informed the nation through a handwritten letter, writing in part:

After his diagnosis, letters of support from well-wishers poured into his California home, but there was also speculation over how long Reagan had demonstrated symptoms of mental degeneration. In her memoirs, former CBS

White House correspondent Lesley Stahl

recounts her final meeting with the president, in 1986: "Reagan didn't seem to know who I was. ... Oh, my, he's gonzo, I thought. I have to go out on the lawn tonight and tell my countrymen that the president of the United States is a doddering space cadet." But then, at the end, he regained his alertness. As she described it, "I had come that close to reporting that Reagan was senile." However, Dr. Lawrence K. Altman, a physician employed as a reporter for the New York Times, noted that "the line between mere forgetfulness and the beginning of Alzheimer's can be fuzzy" and all four of Reagan's White House doctors said that they saw no evidence of Alzheimer's while he was president. Dr. John E. Hutton, Reagan's primary physician from 1984 to 1989, said the president "absolutely" did not "show any signs of dementia or Alzheimer's". Reagan did experience occasional memory lapses, though, especially with names. Once, while meeting with Japanese Prime Minister

Yasuhiro Nakasone

, he repeatedly referred to Vice President Bush as "Prime Minister Bush". Reagan's doctors, however, note that he only began exhibiting overt symptoms of the illness in late 1992 or 1993, several years after he had left office. His former Chief of Staff James Baker

considered "ludicrous" the idea of Reagan sleeping during cabinet meetings. Other staff members, former aides, and friends said they saw no indication of Alzheimer's while he was President. In contrast, Reagan's son, Ron Reagan

, wrote in his 2011 memoir that he had noticed evidence of dementia as early as Reagan's first Presidential term, and that by 1986 Reagan was unable to recall the names of previously familiar landmarks near Los Angeles.

Complicating the picture, Reagan suffered an episode of head trauma in July 1989, five years prior to his diagnosis. After being thrown from a horse in Mexico, a subdural hematoma

Complicating the picture, Reagan suffered an episode of head trauma in July 1989, five years prior to his diagnosis. After being thrown from a horse in Mexico, a subdural hematoma

was found and surgically treated later in the year. Nancy Reagan asserts that her husband's 1989 fall hastened the onset of Alzheimer's disease, citing what doctors told her, although acute brain injury has not been conclusively proven to accelerate Alzheimer's or dementia. Reagan's one-time physician Dr. Daniel Ruge has said it is possible, but not certain, that the horse accident affected the course of Reagan's memory.

Reagan suffered a fall at his Bel Air home on January 13, 2001, resulting in a broken hip. The fracture was repaired the following day and the 89 year old Reagan returned home later that week, although he faced difficult physical therapy at home. On February 6, 2001, Reagan reached the age of 90, becoming the third former president to do so (the other two being John Adams

and Herbert Hoover

, with Gerald Ford

later reaching 90). Reagan's public appearances became much less frequent with the progression of the disease, and as a result, his family decided that he would live in quiet isolation. Nancy Reagan told CNN's Larry King

in 2001 that very few visitors were allowed to see her husband because she felt that "Ronnie would want people to remember him as he was." Following her husband's diagnosis and death, Mrs. Reagan became a stem-cell research advocate, urging Congress

and President George W. Bush

to support federal funding for embryonic stem-cell research, something Bush opposed. In 2009, she praised President Barack Obama

for lifting restrictions on such research. Mrs. Reagan has said that she believes that it could lead to a cure for Alzheimer's.

Reagan died of pneumonia

Reagan died of pneumonia

at his home in Bel Air, California on the afternoon of June 5, 2004. A short time after his death, Nancy Reagan

released a statement saying: "My family and I would like the world to know that President Ronald Reagan has died after 10 years of Alzheimer's Disease at 93 years of age. We appreciate everyone's prayers." President George W. Bush

declared June 11 a National Day of Mourning

, and international tributes came in from around the world. Reagan's body was taken to the Kingsley and Gates Funeral Home in Santa Monica, California later in the day, where well-wishers paid tribute by laying flowers and American flags in the grass. On June 7, his body was removed and taken to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

, where a brief family funeral was held conducted by Pastor Michael Wenning

. His body lay in repose in the Library lobby until June 9; over 100,000 people viewed the coffin.

On June 9, Reagan's body was flown to Washington, D.C. where he became the tenth United States president to lie in state; in thirty-four hours, 104,684 people filed past the coffin.

On June 11, a state funeral

was conducted in the Washington National Cathedral

, and presided over by President George W. Bush. Eulogies were given by former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

, former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney

, and both Presidents Bush. Also in attendance were Mikhail Gorbachev

, and many world leaders, including British Prime Minister Tony Blair

, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder

, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi

, and interim presidents Hamid Karzai

of Afghanistan, and Ghazi al-Yawer

of Iraq.

After the funeral, the Reagan entourage was flown back to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California, where another service was held, and President Reagan was interred. At the time of his death, Reagan was the longest-lived president in U.S. history, having lived 93 years and 120 days (2 years, 8 months, and 23 days longer than John Adams

, whose record he surpassed). He is now the second longest-lived president, just 45 days fewer than Gerald Ford

. He was the first United States president to die in the 21st century, and his was the first state funeral in the United States since that of President Lyndon B. Johnson

in 1973.

His burial site is inscribed with the words he delivered at the opening of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

: "I know in my heart that man is good, that what is right will always eventually triumph and that there is purpose and worth to each and every life."

of The Washington Post has opined that Reagan was "a far more controversial figure in his time than the largely gushing obits on television would suggest." As Kurtz' assertion suggests, there remains substantial and often broadly polarized debate surrounding Reagan and his legacy. Supporters have pointed to a more efficient and prosperous economy, and a peaceful end to the Cold War, while critics contend that Reagan's policies caused huge budget deficits that quadrupled the United States national debt, and lowered American credibility in wake of the Iran-Contra affair. Reagan was also criticized for initially failing to address the AIDS

crisis. Regardless of the debates, Reagan has generally ranked among the most popular of all modern U.S. presidents in public opinion polls.

Edwin Feulner

, President of The Heritage Foundation

, said that Reagan "helped create a safer, freer world" and said of his economic policies: "He took an America suffering from 'malaise'... and made its citizens believe again in their destiny." However, Mark Weisbrot

, co-Director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research

, said that Reagan's "economic policies were mostly a failure"; with Reagan's detractors accusing him of creating a range of fiscal calamities such as widening the wealth inequality

to the point where the richest 1% of Americans held 39% of the nation's wealth, a rise in the poverty population from 26.1 million in 1979 to 32.7 million in 1988, and an increase in homelessness

to 600,000 Americans on any given night.

According to economist and author Jeffery Sachs, Reagan's approach to governance was not all that it seemed on the surface. Sachs states that Reagan's core diagnosis of an overreaching, dysfunctional government "was a fateful misdiagnosis" that caused him to overlook what Sachs asserts should have been the actual core issue during his presidency: "the rise of global competition in the information age." Reagan's oversight, according to Sachs, left America in a state he described as "singularly unprepared to face the global economic, energy and environmental challenges" as the dawn of a new century approached. As a result, according to Sachs, Reagan's presidency had the ironic affect of planting the seeds for a later era of broad-scale Progressivism

, as those seeds have sought full fruition during what Sachs summarized as the discontented era that followed the Reagan era.

Despite the continuing debate surrounding his legacy, many conservative and liberal scholars agree that Reagan has been the most influential president since Franklin D. Roosevelt

, leaving his imprint on American politics, diplomacy, culture, and economics. Since he left office, historians have reached a consensus, as summarized by British historian M. J. Heale, who finds that scholars now concur that Reagan rehabilitated conservatism, turned the nation to the right, practiced a considerably pragmatic conservatism that balanced ideology and the constraints of politics, revived faith in the presidency and in American self-respect, and, as seemed a major preoccupation of his, contributed to victory in the Cold War.

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

was dedicated on November 4, 1991.

He was notable amongst post–World War II presidents as being convinced that the Soviet Union could be defeated rather than simply negotiated with, a conviction that was vindicated by Gennadi Gerasimov

He was notable amongst post–World War II presidents as being convinced that the Soviet Union could be defeated rather than simply negotiated with, a conviction that was vindicated by Gennadi Gerasimov

, the Foreign Ministry spokesman under Gorbachev, who said that Star Wars was "very successful blackmail. ... The Soviet economy couldn't endure such competition." Reagan's strong rhetoric toward the nation had mixed effects; Jeffery W. Knopf, PhD observes that being labeled "evil" probably made no difference to the Soviets but gave encouragement to the East-European citizens opposed to communism. That Reagan had little or no effect in ending the Cold War is argued with equal weight; that Communism's internal weakness had become apparent, and the Soviet Union would have collapsed in the end regardless of who was in power. President Harry Truman's policy of containment is also regarded as a force behind the fall of the U.S.S.R., and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

undermined the Soviet system itself.

General Secretary Gorbachev said of his former rival's Cold War role: "[He was] a man who was instrumental in bringing about the end of the Cold War," and deemed him "a great President." Gorbachev does not acknowledge a win or loss in the war, but rather a peaceful end; he said he was not intimidated by Reagan's harsh rhetoric. Margaret Thatcher, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

, said of Reagan, "he warned that the Soviet Union had an insatiable drive for military power... but he also sensed it was being eaten away by systemic failures impossible to reform." She later said, "Ronald Reagan had a higher claim than any other leader to have won the Cold War for liberty and he did it without a shot being fired." Said Brian Mulroney

, former Prime Minister of Canada

: "He enters history as a strong and dramatic player [in the Cold War]." Former President Lech Wałęsa

of Poland acknowledged, "Reagan was one of the world leaders who made a major contribution to communism's collapse."

s" were a result of his presidency.

Since leaving office, Reagan has become an iconic influence within the Republican party. His policies and beliefs have been frequently invoked by Republican presidential candidates since 1989. The 2008 Republican presidential candidates were no exception, for they aimed to liken themselves to him during the primary debates, even imitating his campaign strategies. Republican nominee John McCain

frequently stated that he came to office as "a foot soldier in the Reagan Revolution". Lastly, Reagan's most famous statement that "Government is not a solution to our problem, government is the problem", has become the unofficial slogan for the rise of conservative commentators like Glenn Beck

and Rush Limbaugh

; as well as the emergence of the Tea Party Movement

.

, and a stronger military. His role in the Cold War further enhanced his image as a different kind of leader. Reagan's "avuncular style, optimism, and plain-folks demeanor" also helped him turn "government-bashing into an art form."

As a sitting president, Reagan did not have the highest approval ratings, but his popularity has increased since 1989. Gallup polls in 2001 and 2007 ranked him number one or number two when correspondents were asked for the greatest president in history, and third of post–World War II presidents in a 2007 Rasmussen Reports

poll, fifth in an ABC 2000 poll, ninth in another 2007 Rasmussen poll, and eighth in a late 2008 poll by United Kingdom newspaper The Times

. In a Siena College

survey of over 200 historians, however, Reagan ranked sixteenth out of 42. While the debate about Reagan's legacy is ongoing, the 2009 Annual C-SPAN

Survey of Presidential Leaders ranked Reagan the 10th greatest president. The survey of leading historians rated Reagan number 11 in 2000.

In 2011, the Institute for the Study of the Americas released the first ever U.K. academic survey to rate U.S. presidents. This poll of U.K. specialists in U.S. history and politics placed Reagan as the 8th greatest U.S. president.

In 2011, the Institute for the Study of the Americas released the first ever U.K. academic survey to rate U.S. presidents. This poll of U.K. specialists in U.S. history and politics placed Reagan as the 8th greatest U.S. president.

Reagan's ability to connect with the American people earned him the laudatory moniker "The Great Communicator". Of it, Reagan said, "I won the nickname the great communicator. But I never thought it was my style that made a difference—it was the content. I wasn't a great communicator, but I communicated great things." His age and soft-spoken speech gave him a warm grandfatherly image.

Reagan also earned the nickname "the Teflon President," in that public perceptions of him were not tarnished by the controversies that arose during his administration. According to Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder

, who coined the phrase, and reporter Howard Kurtz, the epithet referred to Reagan's ability to "do almost anything wrong and not get blamed for it."

Public reaction to Reagan was always mixed; the oldest president was supported by young voters, and began an alliance that shifted many of them to the Republican party. Reagan did not fare well with minority groups, especially African-Americans. This was largely due to his opposition to affirmative action policies. However, his support of Israel throughout his presidency earned him support from many Jews, and he became the first Republican ever to win the Jewish vote. He emphasized family values

in his campaigns and during his presidency, although he was the first president to have been divorced. The combination of Reagan's speaking style, unabashed patriotism, negotiation skills, as well as his savvy use of the media, played an important role in defining the 1980s and his future legacy.

Reagan was known to gibe frequently during his lifetime, displayed humor throughout his presidency, and was famous for his storytelling

. His numerous jokes and one-liners

have been labeled "classic quips" and "legendary". Among the most notable of his jokes was one regarding the Cold War. As a sound check prior to his weekly radio address in August 1984, Reagan made the following joke as a way to test the microphone: "My fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes." Former aide David Gergen

commented, "It was that humor... that I think endeared people to Reagan."

Speaker Hall of Fame and received the United States Military Academy

's Sylvanus Thayer Award

.

In 1989, Reagan was made an Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

, one of the highest British orders (this entitled him to the use of the post-nominal letters "GCB" but, by not being the citizen of a Commonwealth realm

, not to be known as "Sir Ronald Reagan"); only two American presidents have received this honor, Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Reagan was also named an honorary Fellow of Keble College, Oxford

. Japan awarded him the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

in 1989; he was the second American president to receive the order and the first to have it given to him for personal reasons (Dwight D. Eisenhower

received it as a commemoration of U.S.-Japanese relations).

On January 18, 1993, Reagan's former Vice-President and sitting President George H. W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom

On January 18, 1993, Reagan's former Vice-President and sitting President George H. W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom

, the highest honor that the United States can bestow. Reagan was also awarded the Republican Senatorial Medal of Freedom, the highest honor bestowed by Republican members of the Senate.

On Reagan's 87th birthday, in 1998, Washington National Airport was renamed Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport

by a bill signed into law by President Bill Clinton

. That year, the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center