United States Capitol Rotunda

Encyclopedia

Rotunda (architecture)

A rotunda is any building with a circular ground plan, sometimes covered by a dome. It can also refer to a round room within a building . The Pantheon in Rome is a famous rotunda. A Band Rotunda is a circular bandstand, usually with a dome...

of the United States Capitol

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol is the meeting place of the United States Congress, the legislature of the federal government of the United States. Located in Washington, D.C., it sits atop Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

. Located below the Capitol dome

United States Capitol dome

The United States Capitol dome is the massive dome situated above the United States Capitol which reaches upwards to in height and in diameter. The dome was designed by Thomas U...

, it is the tallest part of the Capitol and has been described as its "symbolic and physical heart."

The rotunda is surrounded by corridors connecting the House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

and Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

sides of the Capitol. To the south of the rotunda is the semi-circular National Statuary Hall

National Statuary Hall

National Statuary Hall is a chamber in the United States Capitol devoted to sculptures of prominent Americans. The hall, also known as the Old Hall of the House, is a large, two-story, semicircular room with a second story gallery along the curved perimeter. It is located immediately south of the...

, which until 1857 was the House of Representatives chamber. The northeast of the Rotunda is the Old Senate Chamber

Old Senate Chamber

The Old Senate Chamber is a room in the United States Capitol that was the legislative chamber of the United States Senate from 1810 to 1859. It was designed in Neoclassical style and is elaborately decorated...

, used by the Senate until 1859.

The Rotunda is 96 feet (29.3 m) in diameter and rises 180 feet 3 inches (54.94 m) to the canopy, and is visited by thousands of people each day. It is also used for ceremonial events authorized by concurrent resolution

Concurrent resolution

A concurrent resolution is a resolution adopted by both houses of a bicameral legislature that lacks the force of law and does not require the approval of the chief executive.-United States Congress:...

, including the lying in state

Lying in state

Lying in state is a term used to describe the tradition in which a coffin is placed on view to allow the public at large to pay their respects to the deceased. It traditionally takes place in the principal government building of a country or city...

of honored people.

Design and construction

William Thornton

Dr. William Thornton was a British-American physician, inventor, painter and architect who designed the United States Capitol, an authentic polymath...

was the winner of the contest to design the Capitol in 1793. Thornton had first conceived the idea of a central rotunda. However, due to lack of funds or resources, oft-interrupted construction, and the British attack on Washington

Burning of Washington

The Burning of Washington was an armed conflict during the War of 1812 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States of America. On August 24, 1814, led by General Robert Ross, a British force occupied Washington, D.C. and set fire to many public buildings following...

during the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

, work on the rotunda did not begin until 1818. The rotunda was completed in 1824 under Architect of the Capitol

Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex, and also the head of that agency. The Architect of the Capitol is in the legislative branch and is responsible to the United States...

Charles Bulfinch

Charles Bulfinch

Charles Bulfinch was an early American architect, and has been regarded by many as the first native-born American to practice architecture as a profession....

, as part of a series of new buildings and projects in preparation for the final visit of Marquis de Lafayette in 1824. The rotunda was designed in the neoclassical style

Neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture was an architectural style produced by the neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century, manifested both in its details as a reaction against the Rococo style of naturalistic ornament, and in its architectural formulas as an outgrowth of some classicizing...

and was intended to evoke the design of the Pantheon

Pantheon, Rome

The Pantheon ,Rarely Pantheum. This appears in Pliny's Natural History in describing this edifice: Agrippae Pantheum decoravit Diogenes Atheniensis; in columnis templi eius Caryatides probantur inter pauca operum, sicut in fastigio posita signa, sed propter altitudinem loci minus celebrata.from ,...

.

The sandstone

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

rotunda walls rise 48 feet (15 m) above the floor; everything above this—the Capitol dome–was designed in 1854 by Thomas U. Walter

Thomas U. Walter

Thomas Ustick Walter of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was an American architect, the dean of American architecture between the 1820 death of Benjamin Latrobe and the emergence of H.H. Richardson in the 1870s...

, the fourth Architect of the Capitol. Walter had also designed the Capitol's north and south extensions. Work on the dome began in 1856, and in 1859, Walter redesigned the rotunda to consist of an inner and outer dome, with a canopy suspended between them that would be visible through an oculus

Oculus

An Oculus, circular window, or rain-hole is a feature of Classical architecture since the 16th century. They are often denoted by their French name, oeil de boeuf, or "bull's-eye". Such circular or oval windows express the presence of a mezzanine on a building's façade without competing for...

at the top of the inner dome. In 1862, Walter asked painter Constantino Brumidi

Constantino Brumidi

Constantino Brumidi was an Greek/Italian-American historical painter, best known and honored for his fresco work in the Capitol Building in Washington, DC.-Parentage and early life:...

to design "a picture 65 feet (20 m) in diameter, painted in fresco, on the concave canopy over the eye of the New Dome of the U.S. Capitol." At this time, Brumidi may have added a watercolor canopy design over Walter's tentative 1859 sketch. The dome was being finished in the middle of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

and was constructed from fireproof cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

. During the Civil War, the rotunda was used as a military hospital

Military hospital

Military hospital is a hospital, which is generally located on a military base and is reserved for the use of military personnel, their dependents or other authorized users....

for Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

soldiers. The dome was finally completed in 1866.

Apotheosis of Washington

The Apotheosis of Washington

The Apotheosis of Washington

The Apotheosis of Washington is the immense fresco painted by Italian artist Constantino Brumidi in 1865 and visible through the oculus of the dome in the rotunda of the United States Capitol Building. The fresco is suspended above the rotunda floor and covers an area of . The figures painted are...

(1865) is the very large fresco

Fresco

Fresco is any of several related mural painting types, executed on plaster on walls or ceilings. The word fresco comes from the Greek word affresca which derives from the Latin word for "fresh". Frescoes first developed in the ancient world and continued to be popular through the Renaissance...

painted by a Greek art

Greek art

Greek art began in the Cycladic and Minoan prehistorical civilization, and gave birth to Western classical art in the ancient period...

ist Constantino Brumidi

Constantino Brumidi

Constantino Brumidi was an Greek/Italian-American historical painter, best known and honored for his fresco work in the Capitol Building in Washington, DC.-Parentage and early life:...

in the dome of the rotunda. Brumidi, who left northern Greece at an early age, immigrated to Italy and worked for three years in the Vatican

Vatican City

Vatican City , or Vatican City State, in Italian officially Stato della Città del Vaticano , which translates literally as State of the City of the Vatican, is a landlocked sovereign city-state whose territory consists of a walled enclave within the city of Rome, Italy. It has an area of...

under Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI , born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari, named Mauro as a member of the religious order of the Camaldolese, was Pope of the Catholic Church from 1831 to 1846...

and served several aristocrats

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

as an artist for palace

Palace

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word itself is derived from the Latin name Palātium, for Palatine Hill, one of the seven hills in Rome. In many parts of Europe, the...

s and villa

Villa

A villa was originally an ancient Roman upper-class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became small farming compounds, which were increasingly fortified in Late Antiquity,...

s, including the prince Torlonia

Torlonia

200px|thumb|Coat of arms of the House of Torlonia.The princes Torlonia are an Italian noble family from Rome, who acquired a huge fortune in the 18th and 19th centuries through administering the finances of the Vatican.-History:...

, before immigrating to the United States

Immigration to the United States

Immigration to the United States has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of the United States. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants,...

in 1852, spent much of the last 25 years of his life working in the Capitol and dedicating much of his female based artwork off the love of his life Lola, who married him at the age of 18 in 1855. In addition to the Apotheosis of Washington he designed the Brumidi Corridors

Brumidi Corridors

The Brumidi Corridors are the vaulted, ornately-decorated corridors on the first floor of the Senate wing in the United States Capitol.-Background and artist:...

. On February 19, 1880, at 6:30 AM, while reaching up the steps of one of the platforms he was painting on, Brumidi fell from fatigue and could not move his extremities upon hitting the floor. Suffering from years of ailments, spending most of his salary on medication and depression after his wife Lola left him, Brumidi passed away.

Frieze of American History

The "Frieze of American History" is painted to appear as a carved stone bas-relief friezeFrieze

thumb|267px|Frieze of the [[Tower of the Winds]], AthensIn architecture the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Even when neither columns nor pilasters are expressed, on an astylar wall it lies upon...

but is actually a trompe-l'œil fresco cycle depicting 19 scenes from American history. The "frieze" occupies a band immediately below the 36 windows. Brumidi designed the frieze and prepared a sketch in 1859 but did not begin painting until 1878. Brumidi painted seven and a half scenes. While working on "William Penn

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

and the Indians," Brumidi fell off the scaffolding

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a temporary structure used to support people and material in the construction or repair of buildings and other large structures. It is usually a modular system of metal pipes or tubes, although it can be from other materials...

and held on to a rail for 15 minutes until he was rescued. He died a few months later in 1880. After Brumidi's death, Filippo Costaggini

Filippo Costaggini

thumb|300px|Filippo CostagginiFilippo Costaggini was an artist from Rome, Italy, who worked in the United States Capitol. He and Constantino Brumidi both trained at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, and he came to the United States in 1870. In addition to working in the United States Capitol,...

was commissioned to complete the eight and a half remaining scenes in Brumidi's sketches. He finished in 1889 and left a 31 feet (9 m) gap due to an error in Brumidi's original design. In 1951, Allyn Cox

Allyn Cox

Allyn Cox was an American artist known for his murals, including those he painted in the United States Capitol and the U. S. Department of State....

completed the frieze.

Except for the last three panels named by Allyn Cox, the scenes have no particular titles and many variant titles have been given. The names given here are the names used by the Architect of the Capitol, which uses the names that Brumidi used most frequently in his letters and that were used in Edward Clark and by newspaper articles. The 19 panels are:

| Scene | Description |

|---|---|

|

America and History This is the first panel and the only allegorical one, portraying a personification of America, wearing a liberty cap Liberty cap Chiefly it refers to:*liberty cap, a brimless felt cap, such as the Phrygian cap or pileus, emblematic of a slave's manumission in the Ancient World.The phrase may also refer to:*Liberty Cap, a celebrated granite dome in Yosemite National Park... , with spear and shield in the center, surrounded by other allegorical figures. To the right is an Indian Native Americans in the United States Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as... maiden with a bow and arrows, representing the wild North America North America North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas... n continent. At America's feet is a the female personification of History History History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians... , with a stone tablet to record events. To the left of History is an eagle, perched on a fasces Fasces Fasces are a bundle of wooden sticks with an axe blade emerging from the center, which is an image that traditionally symbolizes summary power and jurisdiction, and/or "strength through unity"... , the ancient Roman Ancient Rome Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world.... bundle of birch Birch Birch is a tree or shrub of the genus Betula , in the family Betulaceae, closely related to the beech/oak family, Fagaceae. The Betula genus contains 30–60 known taxa... rods symbolizing authority Auctoritas Auctoritas is a Latin word and is the origin of English "authority." While historically its use in English was restricted to discussions of the political history of Rome, the beginning of phenomenological philosophy in the twentieth century expanded the use of the word.In ancient Rome, Auctoritas... . To the left of America is another eagle, carrying the olive branch Olive branch The olive branch in Western culture, derived from the customs of Ancient Greece, symbolizes peace or victory and was worn by brides.-Ancient Greece and Rome:... of peace. To the center-left in the background is a man in same pose as the prospector Prospecting Prospecting is the physical search for minerals, fossils, precious metals or mineral specimens, and is also known as fossicking.Prospecting is a small-scale form of mineral exploration which is an organised, large scale effort undertaken by mineral resource companies to find commercially viable ore... at the end of "Discovery of Gold in California"; this is because Brumidi planned to have the scene connect with his planned last one. |

|

Landing of Columbus Christopher Columbus Christopher Columbus Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the... is depicting arriving in the Americas in the first of four scenes of the Spanish conquest. Columbus disembarks off a plank from the Santa María Santa María (ship) La Santa María de la Inmaculada Concepción , was the largest of the three ships used by Christopher Columbus in his first voyage. Her master and owner was Juan de la Cosa.-History:... . His crew, armed with weapons, stays aboard; one crew member has a spyglass Telescope A telescope is an instrument that aids in the observation of remote objects by collecting electromagnetic radiation . The first known practical telescopes were invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 1600s , using glass lenses... . Native Americans are portrayed greeting Columbus. Indian women and children are shown, along with native warriors to the right. The Columbus figure may have been based on Luigi Persico statue of Columbus, which was at the time of the painting the on the east central steps of the Capitol. |

|

Cortez and Montezuma at Mexican Temple This panel shows the Spanish conquistador Conquistador Conquistadors were Spanish soldiers, explorers, and adventurers who brought much of the Americas under the control of Spain in the 15th to 16th centuries, following Europe's discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492... Hernán Cortés Hernán Cortés Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca was a Spanish Conquistador who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of mainland Mexico under the rule of the King of Castile in the early 16th century... entering an Aztec Aztec The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the... temple Aztec mythology The aztec civilization recognized a polytheistic mythology, which contained the many deities and supernatural creatures from their religious beliefs. "orlando"- History :... , being welcomed by Moctezuma II. At the beginning of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Moctezuma Moctezuma II Moctezuma , also known by a number of variant spellings including Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma and referred to in full by early Nahuatl texts as Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, was the ninth tlatoani or ruler of Tenochtitlan, reigning from 1502 to 1520... and the Aztecs honored Cortés as a god, believing that he was the returning god Quetzalcoatl Quetzalcoatl Quetzalcoatl is a Mesoamerican deity whose name comes from the Nahuatl language and has the meaning of "feathered serpent". The worship of a feathered serpent deity is first documented in Teotihuacan in the first century BCE or first century CE... . The Aztec sun stone Aztec sun stone The Aztec calendar stone, Mexica sun stone, Stone of the Sun , or Stone of the Five Eras, is a large monolithic sculpture that was excavated in the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square, on December 17, 1790. It was discovered whilst Mexico City Cathedral was being repaired... and cult image Cult image In the practice of religion, a cult image is a human-made object that is venerated for the deity, spirit or daemon that it embodies or represents... s are based on sketches drawn by Brumidi in Mexico City Mexico City Mexico City is the Federal District , capital of Mexico and seat of the federal powers of the Mexican Union. It is a federal entity within Mexico which is not part of any one of the 31 Mexican states but belongs to the federation as a whole... . |

|

Pizarro Going to Peru Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro Francisco Pizarro Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess was a Spanish conquistador, conqueror of the Incan Empire, and founder of Lima, the modern-day capital of the Republic of Peru.-Early life:... is depicted leading his horse through the jungle in search of El Dorado El Dorado El Dorado is the name of a Muisca tribal chief who covered himself with gold dust and, as an initiation rite, dived into a highland lake.Later it became the name of a legendary "Lost City of Gold" that has fascinated – and so far eluded – explorers since the days of the Spanish Conquistadors... , the mythical land of gold, in this representation of the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. This historic process of military conquest was made by Spanish conquistadores and their native allies.... . |

|

Burial of DeSoto This panel depict the burial of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto Hernando de Soto (explorer) Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who, while leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States, was the first European documented to have crossed the Mississippi River.... in the Mississippi River Mississippi River The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains... after his death from a fever Fever Fever is a common medical sign characterized by an elevation of temperature above the normal range of due to an increase in the body temperature regulatory set-point. This increase in set-point triggers increased muscle tone and shivering.As a person's temperature increases, there is, in... . De Soto has led the largest European expedition of both 15th and 16th centuries through the Southeast Southeastern United States The Southeastern United States, colloquially referred to as the Southeast, is the eastern portion of the Southern United States. It is one of the most populous regions in the United States of America.... and Midwest Midwestern United States The Midwestern United States is one of the four U.S. geographic regions defined by the United States Census Bureau, providing an official definition of the American Midwest.... searching for gold, silver, and other valuables. |

|

Captain Smith and Pocahontas Pocahontas Pocahontas Pocahontas was a Virginia Indian notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of Chief Powhatan, the head of a network of tributary tribal nations in Tidewater Virginia... is portrayed saving Captain John Smith John Smith of Jamestown Captain John Smith Admiral of New England was an English soldier, explorer, and author. He was knighted for his services to Sigismund Bathory, Prince of Transylvania and friend Mózes Székely... , one of the founders of Jamestown, Virginia Jamestown, Virginia Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke... , from being clubbed to death. |

|

Landing of the Pilgrims Pilgrims led by William Brewster William Brewster (Pilgrim) Elder William Brewster was a Mayflower passenger and a Pilgrim colonist leader and preacher.-Origins:Brewster was probably born at Doncaster, Yorkshire, England, circa 1566/1567, although no birth records have been found, and died at Plymouth, Massachusetts on April 10, 1644 around 9- or 10pm... give thanks to God for their safe voyage in this scene depicting Plymouth Colony Plymouth Colony Plymouth Colony was an English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691. The first settlement of the Plymouth Colony was at New Plymouth, a location previously surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement, which served as the capital of the colony, is today the modern town... . |

|

William Penn and the Indians Quaker Religious Society of Friends The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences... leader and Province of Pennsylvania Province of Pennsylvania The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as Pennsylvania Colony, was founded in British America by William Penn on March 4, 1681 as dictated in a royal charter granted by King Charles II... founder William Penn William Penn William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful... is depicted with Lenape Lenape The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the... (Delaware) Native Americans under the elm Elm Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus Ulmus in the plant family Ulmaceae. The dozens of species are found in temperate and tropical-montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ranging southward into Indonesia. Elms are components of many kinds of natural forests... tree at Shackamaxon Shackamaxon Shackamaxon or Shakamaxon was a historic village along the Delaware River inhabited by Delaware Indians in North America. It was located within what are now the borders of the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.... . This is the last panel on which Brumidi worked. |

|

Colonization of New England This panel shows New England New England New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut... settlers busily logging Logging Logging is the cutting, skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks.In forestry, the term logging is sometimes used in a narrow sense concerning the logistics of moving wood from the stump to somewhere outside the forest, usually a sawmill or a lumber yard... , saw Saw A saw is a tool that uses a hard blade or wire with an abrasive edge to cut through softer materials. The cutting edge of a saw is either a serrated blade or an abrasive... ing, and using lumber Timber Timber may refer to:* Timber, a term common in the United Kingdom and Australia for wood materials * Timber, Oregon, an unincorporated community in the U.S... to construct a building. This is the first scene painted entirely by Filippo Costaggini Filippo Costaggini thumb|300px|Filippo CostagginiFilippo Costaggini was an artist from Rome, Italy, who worked in the United States Capitol. He and Constantino Brumidi both trained at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, and he came to the United States in 1870. In addition to working in the United States Capitol,... . |

|

Oglethorpe and the Indians James Oglethorpe James Oglethorpe James Edward Oglethorpe was a British general, member of Parliament, philanthropist, and founder of the colony of Georgia... , founder of Georgia Colony Province of Georgia The Province of Georgia was one of the Southern colonies in British America. It was the last of the thirteen original colonies established by Great Britain in what later became the United States... and first Georgia governor, is shown with the Muskogee Creek people The Muscogee , also known as the Creek or Creeks, are a Native American people traditionally from the southeastern United States. Mvskoke is their name in traditional spelling. The modern Muscogee live primarily in Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida... (Creek) leaders in Savannah, Georgia Savannah, Georgia Savannah is the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. Established in 1733, the city of Savannah was the colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. Today Savannah is an industrial center and an important... . The Muskogee present Oglethorpe with a buffalo American Bison The American bison , also commonly known as the American buffalo, is a North American species of bison that once roamed the grasslands of North America in massive herds... skin with an eagle in the center, a symbol of friendship and trust. |

|

Battle of Lexington This panel depicts the "shot heard 'round the world" at the Battle of Lexington Battles of Lexington and Concord The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. They were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy , and Cambridge, near Boston... , the first major battle of the American Revolutionary War. Major Major (UK) In the British military, major is a military rank which is used by both the British Army and Royal Marines. The rank insignia for a major is a crown... John Pitcairn John Pitcairn John Pitcairn was a British Marine who was stationed in Boston, Massachusetts at the start of the American Revolutionary War.... is shown on horseback at center, with British Army British Army The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England... or Royal Marines Royal Marines The Corps of Her Majesty's Royal Marines, commonly just referred to as the Royal Marines , are the marine corps and amphibious infantry of the United Kingdom and, along with the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, form the Naval Service... troops to the right and Lexington militia Militia The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with... men at left. |

|

Declaration of Independence Idealized depiction of John Adams John Adams John Adams was an American lawyer, statesman, diplomat and political theorist. A leading champion of independence in 1776, he was the second President of the United States... , Thomas Jefferson Thomas Jefferson Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia... , and Benjamin Franklin Benjamin Franklin Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat... , authors of the Declaration of Independence United States Declaration of Independence The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a... , reading the declaration to celebrating colonists. |

|

Surrender of Cornwallis Depiction of George Washington George Washington George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of... on horseback receiving the ceremonial sword of surrender from Charles O'Hara Charles O'Hara General Charles O'Hara was a British military officer who served in the Seven Years War, American War of Independence, and French Revolutionary War, and later served as Governor of Gibraltar... , who represented Lord Cornwallis Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis KG , styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as The Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army officer and colonial administrator... after the final British defeat at the Battle of Yorktown Siege of Yorktown The Siege of Yorktown, Battle of Yorktown, or Surrender of Yorktown in 1781 was a decisive victory by a combined assault of American forces led by General George Washington and French forces led by the Comte de Rochambeau over a British Army commanded by Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis... . In reality, it is thought that Washington declined O'Hara's sword because according to the custom of the time it would only be proper for Washington to receive the sword from Cornwallis himself; Major General Major General Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general... Benjamin Lincoln Benjamin Lincoln Benjamin Lincoln was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War... instead accepted the sword. |

|

Death of Tecumseh This panel depicts the death of Shawnee Shawnee The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania... chief and Indian Confederation leader Tecumseh Tecumseh Tecumseh was a Native American leader of the Shawnee and a large tribal confederacy which opposed the United States during Tecumseh's War and the War of 1812... at the Battle of the Thames Battle of the Thames The Battle of the Thames, also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was a decisive American victory in the War of 1812. It took place on October 5, 1813, near present-day Chatham, Ontario in Upper Canada... in Upper Canada Upper Canada The Province of Upper Canada was a political division in British Canada established in 1791 by the British Empire to govern the central third of the lands in British North America and to accommodate Loyalist refugees from the United States of America after the American Revolution... during the War of 1812 War of 1812 The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant... (partially an extension of Tecumseh's War Tecumseh's War Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion are terms sometimes used to describe a conflict in the Old Northwest between the United States and an American Indian confederacy led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh... ). |

|

American Army Entering the City of Mexico. U.S. Army United States Army The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services... troops led by Winfield Scott Winfield Scott Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852.... enter Mexico City Mexico City Mexico City is the Federal District , capital of Mexico and seat of the federal powers of the Mexican Union. It is a federal entity within Mexico which is not part of any one of the 31 Mexican states but belongs to the federation as a whole... after the fall of Mexico City Battle for Mexico City The Battle for Mexico City refers to the series of engagements from September 8 to September 15, 1847, in the general vicinity of Mexico City during the Mexican-American War... , which ended the Mexican-American War with a decisive American victory. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is the peace treaty, largely dictated by the United States to the interim government of a militarily occupied Mexico City, that ended the Mexican-American War on February 2, 1848... , which provided for the massive Mexican Cession Mexican Cession The Mexican Cession of 1848 is a historical name in the United States for the region of the present day southwestern United States that Mexico ceded to the U.S... of territory in what is now the Western United States Western United States .The Western United States, commonly referred to as the American West or simply "the West," traditionally refers to the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. Because the U.S. expanded westward after its founding, the meaning of the West has evolved over time... . |

|

Discovery of Gold in California Prospectors Prospecting Prospecting is the physical search for minerals, fossils, precious metals or mineral specimens, and is also known as fossicking.Prospecting is a small-scale form of mineral exploration which is an organised, large scale effort undertaken by mineral resource companies to find commercially viable ore... dig Gold extraction Gold extraction or recovery from its ores may require a combination of comminution, mineral processing, hydrometallurgical, and pyrometallurgical processes to be performed on the ore.... and pan Placer mining Placer mining is the mining of alluvial deposits for minerals. This may be done by open-pit or by various surface excavating equipment or tunneling equipment.... for gold with picks, shovels, and other tools in this depiction of the California Gold Rush California Gold Rush The California Gold Rush began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The first to hear confirmed information of the gold rush were the people in Oregon, the Sandwich Islands , and Latin America, who were the first to start flocking to... . In the center, three men (one possibly representing John Sutter John Sutter Johann Augus Sutter was a Swiss pioneer of California known for his association with the California Gold Rush by the discovery of gold by James W. Marshall and the mill making team at Sutter's Mill, and for establishing Sutter's Fort in the area that would eventually become Sacramento, the... ) examine a prospector's pan. This was the last scene designed by Brumidi and painted by Costaggini. |

|

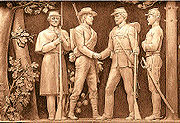

Peace at the End of the Civil War This scene, the first of Allyn Cox's three panels, depicts a Confederate Confederate States Army The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the... soldier and a Union Union Army The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army... soldier shaking hands at the end of the American Civil War American Civil War The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25... , symbolizing reconciliation and reunification. The cotton Cotton Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal.... plant and the Northern pine tree Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus, commonly known as the eastern white pine, is a large pine native to eastern North America, occurring from Newfoundland west to Minnesota and southeastern Manitoba, and south along the Appalachian Mountains to the northern edge of Georgia.It is occasionally known as simply white pine,... symbolize the South Southern United States The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States... and the North Northern United States Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region... . |

|

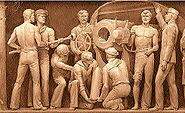

Naval Gun Crew in the Spanish-American War A group of United States Navy United States Navy The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S... sailors in a gun crew are depicted in a naval battle Naval battle A naval battle is a battle fought using boats, ships or other waterborne vessels. Most naval battles have occurred at sea, but a few have taken place on lakes or rivers. The earliest recorded naval battle took place in 1210 BC near Cyprus... during the Spanish–American War. and the United States won a victory over Spain in the war. The 1898 Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris (1898) The Treaty of Paris of 1898 was signed on December 10, 1898, at the end of the Spanish-American War, and came into effect on April 11, 1899, when the ratifications were exchanged.... provided for Cuba's independence from Spain and the American acquisition of Puerto Rico Puerto Rico Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an... , Guam Guam Guam is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States located in the western Pacific Ocean. It is one of five U.S. territories with an established civilian government. Guam is listed as one of 16 Non-Self-Governing Territories by the Special Committee on Decolonization of the United... , and the Philippines Philippines The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam... . |

|

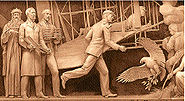

The Birth of Aviation. This scene depicts the Wright brothers' Wright brothers The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur , were two Americans credited with inventing and building the world's first successful airplane and making the first controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight, on December 17, 1903... first flight at Kitty Hawk Kitty Hawk, North Carolina Kitty Hawk is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 3,000 at the 2000 census. It was established in the early 18th century as Chickahawk.... in 1903. The Wright Flyer Wright Flyer The Wright Flyer was the first powered aircraft, designed and built by the Wright brothers. They flew it four times on December 17, 1903 near the Kill Devil Hills, about four miles south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, U.S.The U.S... is shown just off the ground, with Orville Wright in the plane and Wilbur Wright running alongside to steady the wing. To the left are Leonardo da Vinci Leonardo da Vinci Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance... , Samuel Pierpont Langley Samuel Pierpont Langley Samuel Pierpont Langley was an American astronomer, physicist, inventor of the bolometer and pioneer of aviation... , and Octave Chanute Octave Chanute Octave Chanute was a French-born American railway engineer and aviation pioneer. He provided the Wright brothers with help and advice, and helped to publicize their flying experiments. At his death he was hailed as the father of aviation and the heavier-than-air flying machine... , other aviation pioneers, holding models of earlier designs for the first flying machine First flying machine There are conflicting views as to what was the first flying machine.Much of the debate surrounding records of early flying machines depends on the exact definition of what constitutes a "flying machine", "flight", and even "first".... . An eagle holds an olive branch in the bottom right. |

Historical paintings

Eight nichesNiche (architecture)

A niche in classical architecture is an exedra or an apse that has been reduced in size, retaining the half-dome heading usual for an apse. Nero's Domus Aurea was the first semi-private dwelling that possessed rooms that were given richly varied floor plans, shaped with niches and exedras;...

in the rotunda hold large, framed

Picture frame

A picture frame is a decorative edging for a picture, such as a painting or photograph, intended to enhance it, make it easier to display, or protect it.-Construction:...

historical paintings. All are oil-on-canvas

Oil painting

Oil painting is the process of painting with pigments that are bound with a medium of drying oil—especially in early modern Europe, linseed oil. Often an oil such as linseed was boiled with a resin such as pine resin or even frankincense; these were called 'varnishes' and were prized for their body...

and measure 12 by 18 feet (3.6 m by 5.5 m). Four of these are scenes from the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, painted by John Trumbull

John Trumbull

John Trumbull was an American artist during the period of the American Revolutionary War and was notable for his historical paintings...

, who was commissioned by Congress to do the work in 1817. These are Declaration of Independence, Surrender of General Burgoyne, Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, and General George Washington Resigning his Commission. These were placed between 1819 and 1824. Between 1840 and 1855, four more paintings were added. These depicted the exploration and colonization of America and were all done by different artists. These paintings are Landing of Columbus by John Vanderlyn

John Vanderlyn

John Vanderlyn was an American neoclassicist painter.-Biography:Vanderlyn was born at Kingston, New York. He was employed by a print-seller in New York, and was first instructed in art by Archibald Robinson , a Scotsman who was afterwards one of the directors of the American Academy of the Fine Arts...

, Discovery of the Mississippi by William Henry Powell

William Henry Powell

William Henry Powell , was an American artist from Ohio.Powell is known for a painting of the Battle of Lake Erie, of which one copy hangs in the Ohio state capitol building and the other, in the United States Capitol. Powell has a second piece of artwork displayed in the United States Capitol...

, Baptism of Pocahontas by John Gadsby Chapman

John Gadsby Chapman

John Gadsby Chapman was an American artist famous for The Baptism of Pocahontas, which was commissioned by the United States Congress and hangs in the United States Capitol rotunda.- Life and career :...

, and Embarkation of the Pilgrims by Robert Walter Weir

Robert Walter Weir

Robert Walter Weir was an American artist, best known as an educator, and as an historical painter. He was considered an artist of the Hudson River school, was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1829, and an instructor at the United States Military Academy...

.

Declaration of Independence

Trumbull's Declaration of Independence

John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence is a 12-by-18-foot oil-on-canvas painting in the United States Capitol Rotunda that depicts the presentation of the draft of the Declaration of Independence to Congress...

was the first painting that Trumbull completed for the rotunda. An iconic image and probably the most widely recognized of the paintings in the rotunda, the painting was commissioned in 1817, purchased in 1819 and placed in 1826.

The painting depicts John Adams

John Adams

John Adams was an American lawyer, statesman, diplomat and political theorist. A leading champion of independence in 1776, he was the second President of the United States...

, Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman was an early American lawyer and politician, as well as a founding father. He served as the first mayor of New Haven, Connecticut, and served on the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, and was also a representative and senator in the new republic...

, Robert R. Livingston, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

, and the principal author, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

—members of the Committee of Five

Committee of Five

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress drafted and presented to the Congress what became known as America's Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776...

, which drafted the Declaration of Independence—presenting the declaration to the Second Continental Congress

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that started meeting on May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon after warfare in the American Revolutionary War had begun. It succeeded the First Continental Congress, which met briefly during 1774,...

and President

President of the Continental Congress

The President of the Continental Congress was the presiding officer of the Continental Congress, the convention of delegates that emerged as the first national government of the United States during the American Revolution...

John Hancock

John Hancock

John Hancock was a merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts...

in July 1776 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

The painting is not completely historically accurate and is somewhat anachronistic. Of the 56 signers of the Declaration off Independence, 42 are represented; the rest are absent, possibly because they were not present at the adoption of the Declaration of Independence or had died by the time of Trumbull's painting. Four are included who did not sign the declaration but whom Trumbull found worthy also: George Clinton

George Clinton (vice president)

George Clinton was an American soldier and politician, considered one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He was the first Governor of New York, and then the fourth Vice President of the United States , serving under Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. He and John C...

, Robert R. Livingston, Thomas Willing

Thomas Willing

Thomas Willing was an American merchant and financier and a Delegate to the Continental Congress from Pennsylvania....

, and John Dickinson

John Dickinson (delegate)

John Dickinson was an American lawyer and politician from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Wilmington, Delaware. He was a militia officer during the American Revolution, a Continental Congressman from Pennsylvania and Delaware, a delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, President of...

. A reproduction of it appears on the United States two-dollar bill

United States two-dollar bill

The United States two-dollar bill is a current denomination of US currency. President Thomas Jefferson is featured on the obverse of the note...

.

Surrender of General Burgoyne

Surrender of General Burgoyne

The Surrender of General Burgoyne is an oil painting by John Trumbull. The painting was completed in 1821, and hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol in Washington, D. C....

was also commissioned in 1817, purchased in 1822, and placed in 1826. It depicts the surrender of British soldiers

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

under General

General (United Kingdom)

General is currently the highest peace-time rank in the British Army and Royal Marines. It is subordinate to the Army rank of Field Marshal, has a NATO-code of OF-9, and is a four-star rank....

John Burgoyne

John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne was a British army officer, politician and dramatist. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several battles, mostly notably during the Portugal Campaign of 1762....

after the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga

Battle of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga conclusively decided the fate of British General John Burgoyne's army in the American War of Independence and are generally regarded as a turning point in the war. The battles were fought eighteen days apart on the same ground, south of Saratoga, New York...

in 1777. This battle was a key victory for the Americans, prevented the division of New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

, and secured French military assistance to the Americans

France in the American Revolutionary War

France entered the American Revolutionary War in 1778, and assisted in the victory of the Americans seeking independence from Britain ....

.

The central figure, from the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

, is General

General (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Air Force, and United States Marine Corps, general is a four-star general officer rank, with the pay grade of O-10. General ranks above lieutenant general and below General of the Army or General of the Air Force; the Marine Corps does not have an...

Horatio Gates

Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates was a retired British soldier who served as an American general during the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga – Benedict Arnold, who led the attack, was finally forced from the field when he was shot in the leg – and...

, who refused to accept the traditional sword, of surrender, offered by Burgoyne. Instead, treating his former foe as a gentleman, General Gates invited General Burgoyne into his tent. The other Americans, shown to the right, are other officers serving in the Continental Army during the time.

Trumbull planned this outdoor scene to contrast with Declaration of Independence (above), displayed beside it on the wall of the U.S. Capitol rotunda. Both paintings show large groups of people, but one is an indoor scene, while the other is an outdoor scene of similar perspective.

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis was also commissioned in 1817 but placed in 1820. It depicts the final surrender of the British after the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, in which a combined American-French force led by George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Comte de Rochambeau

Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau

Marshal of France Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau was a French nobleman and general who participated in the American Revolutionary War as the commander-in-chief of the French Expeditionary Force which came to help the American Continental Army...

over British troops under Lord Cornwallis. The surrender led to the cessation of major Revolutionary War hostilities and British recognition of American independence in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

.

The scene here depicts the same event as the "Surrender of Cornwallis" panel of the "Frieze of American History." American General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War...

is portrayed at the center of the painting riding a white horse, with French officers on the left and Americans on the right, led by Washington on the brown horse. The British were represented by officers, but Lord Cornwallis himself was not present and was represented instead by Charles O'Hara. As noted above, Washington declined O'Hara's sword because according to the custom of the time it would only be proper from Washington to receive the sword from Cornwallis himself; Major Lincoln accepted the sword in Washington's place. Trumbull was proud of the fact that he had painted portraits of the French officers while in France and included a small self-portrait

Self-portrait

A self-portrait is a representation of an artist, drawn, painted, photographed, or sculpted by the artist. Although self-portraits have been made by artists since the earliest times, it is not until the Early Renaissance in the mid 15th century that artists can be frequently identified depicting...

of himself under the American flag on the right side of the painting.

General George Washington Resigning his Commission was commissioned in 1817 and placed in 1824. It depicts George Washington addressing Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

to resign his commission

Officer (armed forces)

An officer is a member of an armed force or uniformed service who holds a position of authority. Commissioned officers derive authority directly from a sovereign power and, as such, hold a commission charging them with the duties and responsibilities of a specific office or position...

as commander-in-chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

of the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

, on December 23, 1783.

The U.S. Congress, at the time, was meeting at the Maryland State House

Maryland State House

The Maryland State House is located in Annapolis and is the oldest state capitol in continuous legislative use, dating to 1772. It houses the Maryland General Assembly and offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor. The capitol has the distinction of being topped by the largest wooden dome in...

in Annapolis

Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland, as well as the county seat of Anne Arundel County. It had a population of 38,394 at the 2010 census and is situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east of Washington, D.C. Annapolis is...

. This celebrated incident established a strong tradition of civilian control of the military

Civilian control of the military

Civilian control of the military is a doctrine in military and political science that places ultimate responsibility for a country's strategic decision-making in the hands of the civilian political leadership, rather than professional military officers. One author, paraphrasing Samuel P...

in the United States and the rejection of military dictatorship

Military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a form of government where in the political power resides with the military. It is similar but not identical to a stratocracy, a state ruled directly by the military....

in favor of liberal democracy

Liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also known as constitutional democracy, is a common form of representative democracy. According to the principles of liberal democracy, elections should be free and fair, and the political process should be competitive...

.

Washington is depicted along with two aides-de-camp

Aide-de-camp

An aide-de-camp is a personal assistant, secretary, or adjutant to a person of high rank, usually a senior military officer or a head of state...

, as he addresses the president of the Congress. Also shown in the painting are Thomas Mifflin

Thomas Mifflin

Thomas Mifflin was an American merchant and politician from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, a member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, a Continental Congressman from Pennsylvania, President of the Continental...

, Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Thomas Gerry was an American statesman and diplomat. As a Democratic-Republican he was selected as the fifth Vice President of the United States , serving under James Madison, until his death a year and a half into his term...

, and three future U.S. presidents: Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

, James Monroe

James Monroe

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States . Monroe was the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States, and the last president from the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation...

, and James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

. His wife, Martha Washington

Martha Washington

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington was the wife of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Although the title was not coined until after her death, Martha Washington is considered to be the first First Lady of the United States...

, and her three grandchildren, are shown watching from the gallery section (balcony area at right), although they were not in fact present at Washington's resignation.

Landing of Columbus was commissioned in 1836/1837 and placed in 1847. Painted

by John Vanderlyn

John Vanderlyn

John Vanderlyn was an American neoclassicist painter.-Biography:Vanderlyn was born at Kingston, New York. He was employed by a print-seller in New York, and was first instructed in art by Archibald Robinson , a Scotsman who was afterwards one of the directors of the American Academy of the Fine Arts...

, it depicts Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

landing in the West Indies, on San Salvador Island

San Salvador Island

San Salvador Island, also known as Watlings Island, is an island and district of the Bahamas. Until 1986, when the National Geographic Society suggested Samana Cay, it was widely believed that during his first expedition to the New World, San Salvador Island was the first land sighted and visited...

(Guanahani), on October 12, 1492.

In the foreground, Christopher Columbus raises the royal banner to claim the land for Spain, and he stands bareheaded with his hat at his feet in honor of the sanctity of the event. The captains of the ships Niña

Niña

La Niña was one of the three ships used by Christopher Columbus in his first voyage towards the Indies in 1492. The real name of the Niña was Santa Clara. The name Niña was probably a pun on the name of her owner, Juan Niño of Moguer...

and Pinta follow, carrying the banner of the Catholic Monarchs

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs is the collective title used in history for Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both descended from John I of Castile; they were given a papal dispensation to deal with...

, Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I was Queen of Castile and León. She and her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon brought stability to both kingdoms that became the basis for the unification of Spain. Later the two laid the foundations for the political unification of Spain under their grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor...

and Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand the Catholic was King of Aragon , Sicily , Naples , Valencia, Sardinia, and Navarre, Count of Barcelona, jure uxoris King of Castile and then regent of that country also from 1508 to his death, in the name of...

. The crew displays a range of emotions, and some search for gold in the sand. Nearby, natives watch from behind a tree at the right.

Discovery of the Mississippi was the last painting to be commissioned by Congress for the rotunda. William H. Powell

William Henry Powell

William Henry Powell , was an American artist from Ohio.Powell is known for a painting of the Battle of Lake Erie, of which one copy hangs in the Ohio state capitol building and the other, in the United States Capitol. Powell has a second piece of artwork displayed in the United States Capitol...

was given the commission in 1847, and the painting was finally purchased in 1855. At the center of the canvas, Spanish navigator

Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation. The navigator's primary responsibility is to be aware of ship or aircraft position at all times. Responsibilities include planning the journey, advising the Captain or aircraft Commander of estimated timing to...

and conquistador

Conquistador

Conquistadors were Spanish soldiers, explorers, and adventurers who brought much of the Americas under the control of Spain in the 15th to 16th centuries, following Europe's discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492...

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (explorer)

Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who, while leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States, was the first European documented to have crossed the Mississippi River....

is seen riding a white horse. De Soto is thought to have become the first European to see the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

in 1541.

The painting depicts de Soto and his troops approaching Native Americans in front of tepees, with a chief holding a peace pipe. The foreground is filled by weapons and soldiers to represent the devastating battle at Mauvila (or Mabila

Mabila

The town of Mabila was a small fortress town known to Chief Tuskaloosa in 1540, in a region of present-day central Alabama. The exact location has been debated for centuries...

), in which de Soto suffered a Pyrrhic victory

Pyrrhic victory

A Pyrrhic victory is a victory with such a devastating cost to the victor that it carries the implication that another such victory will ultimately cause defeat.-Origin:...

over Choctaw

Choctaw

The Choctaw are a Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States...

s under Tuscaloosa

Chief Tuscaloosa

Tuskaloosa was a paramount chief of a Mississippian chiefdom in what is now the U.S. state of Alabama. His people were possibly ancestors to the several southern Native American confederacies who later emerged in the region...

. To the right, a monk

Monk

A monk is a person who practices religious asceticism, living either alone or with any number of monks, while always maintaining some degree of physical separation from those not sharing the same purpose...

prays as a large crucifix

Crucifix

A crucifix is an independent image of Jesus on the cross with a representation of Jesus' body, referred to in English as the corpus , as distinct from a cross with no body....

is set into the ground.

Baptism of Pocahontas was painted by John Gadsby Chapman

John Gadsby Chapman

John Gadsby Chapman was an American artist famous for The Baptism of Pocahontas, which was commissioned by the United States Congress and hangs in the United States Capitol rotunda.- Life and career :...

, given the commission in 1837. The painting was placed in 1840. It depicts Pocahontas

Pocahontas

Pocahontas was a Virginia Indian notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of Chief Powhatan, the head of a network of tributary tribal nations in Tidewater Virginia...

in white as she is baptized

Baptism

In Christianity, baptism is for the majority the rite of admission , almost invariably with the use of water, into the Christian Church generally and also membership of a particular church tradition...

(under the name "Rebecca

Rebecca

Rebecca a biblical matriarch from the Book of Genesis and a common first name. In this book Rebecca was said to be a beautiful girl. As a name it is often shortened to Becky, Becki or Becca; see Rebecca ....

") by the Anglican priest Alexander Whiteaker in Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

. This event is believed to have taken place in 1613 or 1614.

Pocahontas kneels, surrounded by family members, including her father, Chief Powhatan

Chief Powhatan

Chief Powhatan , whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh , was the paramount chief of Tsenacommacah, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Virginia Indians in the Tidewater region of Virginia at the time English settlers landed at Jamestown in 1607...

, and colonists. Her brother Nantequaus turns away from the ceremony. The baptism occurred before her marriage to Englishman John Rolfe

John Rolfe

John Rolfe was one of the early English settlers of North America. He is credited with the first successful cultivation of tobacco as an export crop in the Colony of Virginia and is known as the husband of Pocahontas, daughter of the chief of the Powhatan Confederacy.In 1961, the Jamestown...

who stands behind her. Their union is said to be the first recorded marriage between a European and a Native American. The scene symbolizes the belief of some Americans at the time that native tribes should accept Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

and other European customs of the period.

Embarkation of the Pilgrims was also commissioned in 1837 and placed in 1844. Painted by Robert W. Weir, it depicts the Pilgrims on the deck of the ship Speedwell

Speedwell (ship)