History of South Africa

Encyclopedia

South African history has been dominated by the interaction and conflict of several diverse ethnic groups. The aboriginal Khoisan

Khoisan

Khoisan is a unifying name for two ethnic groups of Southern Africa, who share physical and putative linguistic characteristics distinct from the Bantu majority of the region. Culturally, the Khoisan are divided into the foraging San and the pastoral Khoi...

people have lived in the region for millennia. Most of the population, however, trace their history to immigration since. Indigenous Africans in South Africa are descendants of immigrants from further north in Africa who first entered what are now the confines of the country roughly one thousand years ago. White South Africans

Whites in South Africa

White South African is a term which refers to people from South Africa who are of European descent and who don't regard themselves, or are not regarded as being part of another racial group, for example, as Coloured...

are descendants of later European settlers, mainly from the Netherlands and Britain. The Coloured

Coloured

In the South African, Namibian, Zambian, Botswana and Zimbabwean context, the term Coloured refers to an heterogenous ethnic group who possess ancestry from Europe, various Khoisan and Bantu tribes of Southern Africa, West Africa, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaya, India, Mozambique,...

s are descended at least in part from all of these groups, as well as from slaves from the then East Indies, and there are many South Africans of Indian and Chinese origin, descendants of labourers who arrived in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The history South Africa is taken here more broadly to cover the history not only of the current South African state but of other polities in the region, including those of the Khoisan, the several Bantu kingdoms in the region before colonisation, the rule of the Dutch in the Cape

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony, part of modern South Africa, was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, with the founding of Cape Town. It was subsequently occupied by the British in 1795 when the Netherlands were occupied by revolutionary France, so that the French revolutionaries could not take...

and the subsequent rule of the British there and in Natal

Natal, South Africa

Natal is a region in South Africa. It stretches between the Indian Ocean in the south and east, the Drakensberg in the west, and the Lebombo Mountains in the north. The main cities are Pietermaritzburg and Durban...

, and the so-called Boer republics

Boer Republics

The Boer Republics were independent self-governed republics created by the northeastern frontier branch of the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of the north eastern Cape Province and their descendants in mainly the northern and eastern parts of what is now the country of...

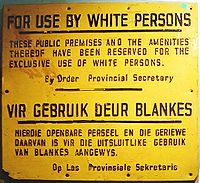

, including the Orange Free State and the South African Republic. South Africa was under an official system of racial segregation and white minority rule from 1948 known as Apartheid, until its first egalitarian elections in 1994, when the ruling African National Congress came to dominate the politics of the country.

Ancient and medieval history

Starting from around 500 BCAnno Domini

and Before Christ are designations used to label or number years used with the Julian and Gregorian calendars....

, some San groups acquired livestock from further north. Gradually, hunting and gathering gave way to herding

Herding

Herding is the act of bringing individual animals together into a group , maintaining the group and moving the group from place to place—or any combination of those. While the layperson uses the term "herding", most individuals involved in the process term it mustering, "working stock" or...

as the dominant economic

Economic system

An economic system is the combination of the various agencies, entities that provide the economic structure that defines the social community. These agencies are joined by lines of trade and exchange along which goods, money etc. are continuously flowing. An example of such a system for a closed...

activity as these San People tended to small herd

Herd

Herd refers to a social grouping of certain animals of the same species, either wild or domestic, and also to the form of collective animal behavior associated with this or as a verb, to herd, to its control by another species such as humans or dogs.The term herd is generally applied to mammals,...

s of cattle and ox

Ox

An ox , also known as a bullock in Australia, New Zealand and India, is a bovine trained as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration makes the animals more tractable...

en. The arrival of livestock introduced concepts of personal wealth

Wealth

Wealth is the abundance of valuable resources or material possessions. The word wealth is derived from the old English wela, which is from an Indo-European word stem...

and property

Property

Property is any physical or intangible entity that is owned by a person or jointly by a group of people or a legal entity like a corporation...

-ownership

Ownership

Ownership is the state or fact of exclusive rights and control over property, which may be an object, land/real estate or intellectual property. Ownership involves multiple rights, collectively referred to as title, which may be separated and held by different parties. The concept of ownership has...

into San society. Community structures solidified and expanded, and chief

Chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political economy that organizes regional populations through a hierarchy of the chief.In anthropological theory, one model of human social development rooted in ideas of cultural evolution describes a chiefdom as a form of social organization more complex than a tribe or a band...

taincies developed. These pastoralist San People became known as Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi

The Khoikhoi or Khoi, in standardised Khoekhoe/Nama orthography spelled Khoekhoe, are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group, the native people of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen . They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD...

('men of men'), as opposed to the still hunter-gatherer San People, whom the Colonialist Settlers referred to as Bushmen. At the point where the two groups became intermarried, mixed and hard to tell apart, the term Khoisan

Khoisan

Khoisan is a unifying name for two ethnic groups of Southern Africa, who share physical and putative linguistic characteristics distinct from the Bantu majority of the region. Culturally, the Khoisan are divided into the foraging San and the pastoral Khoi...

arose.

Over time the Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi

The Khoikhoi or Khoi, in standardised Khoekhoe/Nama orthography spelled Khoekhoe, are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group, the native people of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen . They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD...

established themselves along the coast, while small groups of San continued to inhabit the interior.

Around 2,500 years ago Bantu peoples started migrating

Human migration

Human migration is physical movement by humans from one area to another, sometimes over long distances or in large groups. Historically this movement was nomadic, often causing significant conflict with the indigenous population and their displacement or cultural assimilation. Only a few nomadic...

across sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa as a geographical term refers to the area of the African continent which lies south of the Sahara. A political definition of Sub-Saharan Africa, instead, covers all African countries which are fully or partially located south of the Sahara...

from the Niger River Delta

Niger River

The Niger River is the principal river of western Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in southeastern Guinea...

. The San People of Southern Africa and the Bantu-speakers didn't have any method of writing, so researchers know little of this period outside of archaeological

Archaeology

Archaeology, or archeology , is the study of human society, primarily through the recovery and analysis of the material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts and cultural landscapes...

artefacts

The Bantu-speakers had started to make their way south and eastwards in about 1000 BC, reaching the present-day KwaZulu-Natal Province by 500 CE. The Bantu-speakers had an advanced Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

culture, keeping domestic animals and also practising agriculture, farming sorghum

Sorghum

Sorghum is a genus of numerous species of grasses, one of which is raised for grain and many of which are used as fodder plants either cultivated or as part of pasture. The plants are cultivated in warmer climates worldwide. Species are native to tropical and subtropical regions of all continents...

and other crops. They lived in small settled villages. The Bantu-speakers arrived in South Africa in small waves rather than in one cohesive migration. Some groups, the ancestor

Ancestor

An ancestor is a parent or the parent of an ancestor ....

s of today's Nguni people

Nguni people

-History:The ancient history of the Nguni people is wrapped up in their oral history. According to legend they were a people who migrated from Egypt to the Great Lakes region of sub-equatorial Central/East Africa...

s (the Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi, and Ndebele), preferred to live near the coast. Others, now known as the Sotho–Tswana peoples (Tswana, Pedi

Pedi people

Pedi, , has been a cultural/linguistic term. It was previously used to describe the entire set of people speaking various dialects of the Sotho language who live in the northern Transvaal of South Africa...

, and Basotho

Basotho

The ancestors of the Sotho people have lived in southern Africa since around the fifth century. The Sotho nation emerged from the accomplished diplomacy of Moshoeshoe I who gathered together disparate clans of Sotho–Tswana origin that had dispersed across southern Africa in the early 19th century...

), settled in the Highveld, while today's Venda

Venda

Venda was a bantustan in northern South Africa, now part of Limpopo province. It was founded as a homeland for the Venda people, speakers of the Venda language. It bordered modern Zimbabwe and South Africa, and is now part of Limpopo in South Africa....

, Lemba

Lemba

The Lemba or 'wa-Remba' are a southern African ethnic group to be found in Zimbabwe and South Africa with some little known branches in Mozambique and Malawi. According to Parfitt they are thought to number 70,000...

, and Shangaan

Shangaan

The Tsonga people inhabit the southern coastal plain of Mozambique, parts of Zimbabwe and Swaziland, and the Limpopo Province of South Africa...

-Tsonga peoples made their homes in the north-eastern areas of South Africa

Bantu-speakers and Khoisan mixed, as evidenced by rock paintings showing the two different groups interacting. The type of contact remains unknown, although linguistic

Linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. Linguistics can be broadly broken into three categories or subfields of study: language form, language meaning, and language in context....

proof of integration survives, as several Southern Bantu languages

Bantu languages

The Bantu languages constitute a traditional sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages. There are about 250 Bantu languages by the criterion of mutual intelligibility, though the distinction between language and dialect is often unclear, and Ethnologue counts 535 languages...

(notably Xhosa

Xhosa language

Xhosa is one of the official languages of South Africa. Xhosa is spoken by approximately 7.9 million people, or about 18% of the South African population. Like most Bantu languages, Xhosa is a tonal language, that is, the same sequence of consonants and vowels can have different meanings when said...

and Zulu

Zulu language

Zulu is the language of the Zulu people with about 10 million speakers, the vast majority of whom live in South Africa. Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in South Africa as well as being understood by over 50% of the population...

) incorporated many click consonant

Click consonant

Clicks are speech sounds found as consonants in many languages of southern Africa, and in three languages of East Africa. Examples of these sounds familiar to English speakers are the tsk! tsk! or tut-tut used to express disapproval or pity, the tchick! used to spur on a horse, and the...

s of earlier Khoisan languages

Khoisan languages

The Khoisan languages are the click languages of Africa which do not belong to other language families. They include languages indigenous to southern and eastern Africa, though some, such as the Khoi languages, appear to have moved to their current locations not long before the Bantu expansion...

. Archaeologists have found numerous Khoisan artefacts at the sites of Bantu settlements

From around 1200 AD a trade network began to emerge just to the North as is evidenced at such sites as Mapungubwe

Mapungubwe

After Mapungubwe's fall, it was forgotten until 1932. On New Year's Eve 1932, E. S. J. van Graan, a local farmer and prospector, and his son, a former student of the University of Pretoria, discovered the wealth of artifacts on top of the hill. They reported the find to Professor Leo...

. Additionally, the idea of sacred leadership emerged – concept that transcends English terms such as “Kings”

Monarch

A monarch is the person who heads a monarchy. This is a form of government in which a state or polity is ruled or controlled by an individual who typically inherits the throne by birth and occasionally rules for life or until abdication...

or “Queens”

Queen regnant

A queen regnant is a female monarch who reigns in her own right, in contrast to a queen consort, who is the wife of a reigning king. An empress regnant is a female monarch who reigns in her own right over an empire....

. Sacred

Sacred

Holiness, or sanctity, is in general the state of being holy or sacred...

leaders were elite

Elite

Elite refers to an exceptional or privileged group that wields considerable power within its sphere of influence...

members of the community, types of prophet

Prophet

In religion, a prophet, from the Greek word προφήτης profitis meaning "foreteller", is an individual who is claimed to have been contacted by the supernatural or the divine, and serves as an intermediary with humanity, delivering this newfound knowledge from the supernatural entity to other people...

s, people with supernatural

Supernatural

The supernatural or is that which is not subject to the laws of nature, or more figuratively, that which is said to exist above and beyond nature...

powers and the ability to predict the future.

Ivory trade

The ivory trade is the commercial, often illegal trade in the ivory tusks of the hippopotamus, walrus, narwhal, mammoth, and most commonly, Asian and African elephants....

and trading for glass beads

Powder glass beads

The earliest powder glass beads on record were discovered during archaeological excavations at Mapungubwe, in present-day Zimbabwe, and dated to 970-1000 CE. In our time, the main area of powder glass bead manufacture is West Africa, most importantly, Ghana...

and porcelain

Porcelain

Porcelain is a ceramic material made by heating raw materials, generally including clay in the form of kaolin, in a kiln to temperatures between and...

from as far away as China.

European expeditions

Although the PortuguesePortugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

basked in the nautical achievement of successfully navigating the cape, they showed little interest in colonisation. The area's fierce weather and rocky shoreline posed a threat to their ships, and many of their attempts to trade with the local Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi

The Khoikhoi or Khoi, in standardised Khoekhoe/Nama orthography spelled Khoekhoe, are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group, the native people of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen . They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD...

ended in conflict. The Portuguese found the Mozambican coast more attractive, with appealing bay

Headlands and bays

Headlands and bays are two related features of the coastal environment.- Geology and geography :Headlands and bays are often found on the same coastline. A bay is surrounded by land on three sides, whereas a headland is surrounded by water on three sides. Headlands are characterized by high,...

s to use as way stations, for prawn

Prawn

Prawns are decapod crustaceans of the sub-order Dendrobranchiata. There are 540 extant species, in seven families, and a fossil record extending back to the Devonian...

ing, and as links to gold ore

Gold mining

Gold mining is the removal of gold from the ground. There are several techniques and processes by which gold may be extracted from the earth.-History:...

in the interior.

The Portuguese had little competition in the region until the late 16th century, when the English

Evolution of the British Empire

The territorial evolution of the British Empire is considered to have begun with the foundation of the English colonial empire in the late 16th century...

and Dutch

Dutch Empire

The Dutch Empire consisted of the overseas territories controlled by the Dutch Republic and later, the modern Netherlands from the 17th to the 20th century. The Dutch followed Portugal and Spain in establishing an overseas colonial empire, but based on military conquest of already-existing...

began to challenge the Portuguese along their trade route

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

s. Stops at the continent's southern tip increased, and the cape became a regular stopover for scurvy

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

-ridden crews. In 1647, a Dutch vessel was wrecked in the present-day Table Bay

Table Bay

Table Bay is a natural bay on the Atlantic Ocean overlooked by Cape Town and is at the northern end of the Cape Peninsula, which stretches south to the Cape of Good Hope. It was named because it is dominated by the flat-topped Table Mountain.Bartolomeu Dias was the first European to explore this...

at Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

. The marooned crew, the first Europeans to attempt settlement in the area, built a fort and stayed for a year until they were rescued.

Arrival of the Dutch

Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia...

(in the Dutch of the day: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) decided to establish a permanent settlement. The VOC, one of the major European trading houses sailing the spice route

Spice trade

Civilizations of Asia were involved in spice trade from the ancient times, and the Greco-Roman world soon followed by trading along the Incense route and the Roman-India routes...

to the East, had no intention of colonising the area, instead wanting only to establish a secure base camp where passing ships could shelter, and where hungry sailors could stock up on fresh supplies of meat, fruit, and vegetables. To this end, a small VOC expedition under the command of Jan van Riebeeck

Jan van Riebeeck

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck was a Dutch colonial administrator and founder of Cape Town.-Biography:...

reached Table Bay on 6 April 1652.

While the new settlement traded out of necessity with the neighbouring Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi

The Khoikhoi or Khoi, in standardised Khoekhoe/Nama orthography spelled Khoekhoe, are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group, the native people of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen . They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD...

, it was not a friendly relationship, and the company authorities made deliberate attempts to restrict contact. Partly as a consequence, VOC employees found themselves faced with a labour shortage. To remedy this, they released a small number of Dutch from their contracts and permitted them to establish farms, with which they would supply the VOC settlement from their harvest

Harvest

Harvest is the process of gathering mature crops from the fields. Reaping is the cutting of grain or pulse for harvest, typically using a scythe, sickle, or reaper...

s. This arrangement proved highly successful, producing abundant supplies of fruit, vegetables, wheat, and wine; they also later raised livestock. The small initial group of free burghers, as these farmers were known, steadily increased in number and began to expand their farms further north and east into the territory of the Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi

The Khoikhoi or Khoi, in standardised Khoekhoe/Nama orthography spelled Khoekhoe, are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group, the native people of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen . They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD...

.

The majority of burghers had Dutch ancestry and belonged to the Calvinist Reformed Church of the Netherlands, but there were also numerous Germans as well as some Scandinavia

Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern Europe that includes the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, characterized by their common ethno-cultural heritage and language. Modern Norway and Sweden proper are situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula,...

ns. In 1688 the Dutch and the Germans were joined by French Huguenots, also Calvinists, who were fleeing religious persecution in France under King Louis XIV

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

.

In addition to establishing the free burgher system, van Riebeeck and the VOC also began to import large numbers of slaves, primarily from Madagascar

Madagascar

The Republic of Madagascar is an island country located in the Indian Ocean off the southeastern coast of Africa...

and Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

. These slaves often married Dutch settlers, and their descendants became known as the Cape Coloureds

Cape Coloureds

The Cape Coloureds form a minority group within South Africa, however they are the predominant population group in the Western Cape. They are generally bilingual, however subsets within the group can be exclusively Afrikaans speakers, whereas others primarily speak English...

and the Cape Malays

Cape Malays

The Cape Malay community is an ethnic group or community in South Africa. It derives its name from the present-day Western Cape of South Africa and the people originally from Maritime Southeast Asia, mostly Javanese from modern-day Indonesia, a Dutch colony for several centuries, and Dutch...

. A significant number of the offspring from the White and slave unions were absorbed into the local proto-Afrikaans

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic language, spoken natively in South Africa and Namibia. It is a daughter language of Dutch, originating in its 17th century dialects, collectively referred to as Cape Dutch .Afrikaans is a daughter language of Dutch; see , , , , , .Afrikaans was historically called Cape...

speaking White population. With this additional labour, the areas occupied by the VOC expanded further to the north and east, with inevitable clashes with the Khoikhoi. The newcomers drove the Khoikhoi from their traditional lands, decimated them with introduced diseases, and destroyed them with superior weapons when they fought back, which they did in a number of major wars and with guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

resistance movements that continued into the 19th century. Most survivors were left with no option but to work for the Europeans in an exploitative arrangement that differed little from slavery. Over time, the Khoisan, their European overseers, and the imported slaves mixed, with the offspring of these unions forming the basis for today's Coloured

Coloured

In the South African, Namibian, Zambian, Botswana and Zimbabwean context, the term Coloured refers to an heterogenous ethnic group who possess ancestry from Europe, various Khoisan and Bantu tribes of Southern Africa, West Africa, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaya, India, Mozambique,...

population.

The best-known Khoikhoi groups included the Griqua, who had originally lived on the western coast between St Helena Bay

St Helena Bay

St Helena Bay is a settlement in West Coast District Municipality in the Western Cape province of South Africa....

and the Cederberg Range. In the late 18th century, they managed to acquire guns and horses and began trekking north-east. En route, other groups of Khoisan, Coloureds, and even white adventurers joined them, and they rapidly gained a reputation as a formidable military force. Ultimately, the Griquas reached the Highveld around present-day Kimberley, where they carved out territory that came to be known as Griqualandalina.

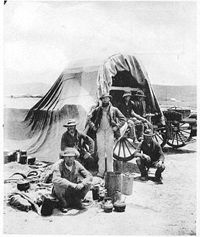

Burgher expansion

Pastoralism

Pastoralism or pastoral farming is the branch of agriculture concerned with the raising of livestock. It is animal husbandry: the care, tending and use of animals such as camels, goats, cattle, yaks, llamas, and sheep. It may have a mobile aspect, moving the herds in search of fresh pasture and...

lifestyle, in some ways not far removed from that of the Khoikhoi they displaced. In addition to its herds, a family might have a wagon

Wagon

A wagon is a heavy four-wheeled vehicle pulled by draught animals; it was formerly often called a wain, and if low and sideless may be called a dray, trolley or float....

, a tent

Tent

A tent is a shelter consisting of sheets of fabric or other material draped over or attached to a frame of poles or attached to a supporting rope. While smaller tents may be free-standing or attached to the ground, large tents are usually anchored using guy ropes tied to stakes or tent pegs...

, a Bible, and a few guns. As they became more settled, they would build a mud

Mud

Mud is a mixture of water and some combination of soil, silt, and clay. Ancient mud deposits harden over geological time to form sedimentary rock such as shale or mudstone . When geological deposits of mud are formed in estuaries the resultant layers are termed bay muds...

-walled cottage

Cottage

__toc__In modern usage, a cottage is usually a modest, often cozy dwelling, typically in a rural or semi-rural location. However there are cottage-style dwellings in cities, and in places such as Canada the term exists with no connotations of size at all...

, frequently located, by choice, days of travel from the nearest European settlement. These were the first of the Trekboer

Trekboer

The Trekboers were nomadic pastoralists descended from almost equal numbers of Dutch colonists, French Huguenots and German Protestants. The Trekboere began migrating from the areas surrounding what is now Cape Town during the 17th century throughout the 18th century.-Origins:The Trekboere were...

s (Wandering Farmers, later shortened to Boer

Boer

Boer is the Dutch and Afrikaans word for farmer, which came to denote the descendants of the Dutch-speaking settlers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 18th century, as well as those who left the Cape Colony during the 19th century to settle in the Orange Free State,...

s), completely independent of official controls, extraordinarily self-sufficient, and isolated. Their harsh lifestyle produced individualists

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that stresses "the moral worth of the individual". Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance while opposing most external interference upon one's own...

who were well acquainted with the land. Like many pioneers with Christian backgrounds, the burghers attempted to live their lives – and to construct a theocracy

Theocracy

Theocracy is a form of organization in which the official policy is to be governed by immediate divine guidance or by officials who are regarded as divinely guided, or simply pursuant to the doctrine of a particular religious sect or religion....

– based on their particular Christian denominations (Dutch Reformed Church

Dutch Reformed Church

The Dutch Reformed Church was a Reformed Christian denomination in the Netherlands. It existed from the 1570s to 2004, the year it merged with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Kingdom of the Netherlands to form the Protestant Church in the...

) reading into eisegesis

Eisegesis

Eisegesis is the process of misinterpreting a text in such a way that it introduces one's own ideas, reading into the text. This is best understood when contrasted with exegesis. While exegesis draws out the meaning from the text, eisegesis occurs when a reader reads his/her interpretation into...

characters and plot found in the Hebrew scriptures (as distinct from the Christian Gospels and Epistles).

British at the Cape

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

moved in to fill the vacuum. They seized the Cape in 1795 to prevent it from falling into French hands, then briefly relinquished it back to the Dutch (1803), before definitively conquering it in 1806. British sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

of the area was recognised at the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

in 1815.

At the tip of the continent the British found an established colony with 25,000 slaves, 20,000 white colonists, 15,000 Khoisan

Khoisan

Khoisan is a unifying name for two ethnic groups of Southern Africa, who share physical and putative linguistic characteristics distinct from the Bantu majority of the region. Culturally, the Khoisan are divided into the foraging San and the pastoral Khoi...

, and 1,000 freed black slaves. Power resided solely with a white élite

Elite

Elite refers to an exceptional or privileged group that wields considerable power within its sphere of influence...

in Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

, and differentiation on the basis of race was deeply entrenched. Outside Cape Town and the immediate hinterland, isolated black and white pastoralists populated the country.

Like the Dutch before them, the British initially had little interest in the Cape Colony, other than as a strategically located port. As one of their first tasks they tried to resolve a troublesome border dispute between the Boers and the Xhosa on the colony's eastern frontier. In 1820 the British authorities persuaded about 5,000 middle-class British immigrants (most of them "in trade") to leave Great Britain behind and settle on tracts of land between the feuding groups with the idea of providing a buffer zone. The plan was singularly unsuccessful. Within three years, almost half of these 1820 Settlers

1820 Settlers

The 1820 Settlers were several groups or parties of white British colonists settled by the British government and the Cape authorities in the South African Eastern Cape in 1820....

had retreated to the towns, notably Grahamstown

Grahamstown

Grahamstown is a city in the Eastern Cape Province of the Republic of South Africa and is the seat of the Makana municipality. The population of greater Grahamstown, as of 2003, was 124,758. The population of the surrounding areas, including the actual city was 41,799 of which 77.4% were black,...

and Port Elizabeth, to pursue the jobs they had held in Britain.

While doing nothing to resolve the border dispute, this influx of settlers solidified the British presence in the area, thus fracturing the relative unity of white South Africa. Where the Boers and their ideas had before gone largely unchallenged, white South Africa now had two distinct language groups and two distinct cultures. A pattern soon emerged whereby English-speakers became highly urbanised, and dominated politics, trade, finance, mining, and manufacturing, while the largely uneducated Boers were relegated to their farms.

The gap between the British settlers and the Boers further widened with the abolition of slavery in 1834, a move that the Boers generally regarded as against the God-given ordering of the races. Yet the British settlers' conservatism stopped any radical social reforms, and in 1841 the authorities passed a Masters and Servants Ordinance, which perpetuated white control. Meanwhile, numbers of British immigrants increased rapidly in Cape Town, in the area east of the Cape Colony (present-day Eastern Cape Province), in Natal

Colony of Natal

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on May 4, 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three other colonies to form the Union of South Africa, as one of its...

. The discovery of diamonds at Kimberley

Kimberley, Northern Cape

Kimberley is a city in South Africa, and the capital of the Northern Cape. It is located near the confluence of the Vaal and Orange Rivers. The town has considerable historical significance due its diamond mining past and siege during the Second Boer War...

and the subsequent discovery of gold in parts of the Transvaal

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

, mainly around present-day Gauteng led to a rapid increase in immigration of fortune seekers from all parts of the globe, including Africa itself.

Difaqane and destruction

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

. Sotho-speakers know this period as the difaqane ("forced migration

Forced migration

Forced migration refers to the coerced movement of a person or persons away from their home or home region...

"); while Zulu

Zulu language

Zulu is the language of the Zulu people with about 10 million speakers, the vast majority of whom live in South Africa. Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in South Africa as well as being understood by over 50% of the population...

-speakers call it the mfecane ("crushing").

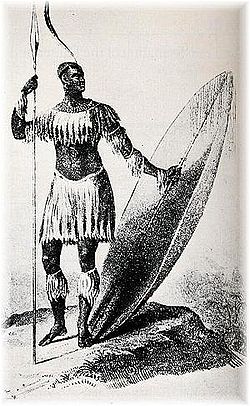

The full causes of the difaqane remain in dispute, although certain factors stand out. The rise of a unified Zulu kingdom had particular significance. In the early 19th century, Nguni

Nguni people

-History:The ancient history of the Nguni people is wrapped up in their oral history. According to legend they were a people who migrated from Egypt to the Great Lakes region of sub-equatorial Central/East Africa...

tribes in KwaZulu-Natal began to shift from a loosely organised collection of kingdoms into a centralised, militaristic state. Shaka Zulu, son of the chief of the small Zulu clan, became the driving force behind this shift. At first something of an outcast, Shaka proved himself in battle and gradually succeeded in consolidating power in his own hands. He built large armies

Army

An army An army An army (from Latin arma "arms, weapons" via Old French armée, "armed" (feminine), in the broadest sense, is the land-based military of a nation or state. It may also include other branches of the military such as the air force via means of aviation corps...

, breaking from clan tradition by placing the armies under the control of his own officers rather than of the hereditary chiefs. Shaka then set out on a massive programme of expansion, killing or enslaving those who resisted in the territories he conquered. His impis (warrior regiments) were rigorously disciplined: failure in battle meant death.

Peoples in the path of Shaka's armies moved out of his way, becoming in their turn aggressors against their neighbours. This wave of displacement spread throughout Southern Africa and beyond. It also accelerated the formation of several states, notably those of the Sotho (present-day Lesotho

Lesotho

Lesotho , officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a landlocked country and enclave, surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It is just over in size with a population of approximately 2,067,000. Its capital and largest city is Maseru. Lesotho is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The name...

) and of the Swazi (now Swaziland

Swaziland

Swaziland, officially the Kingdom of Swaziland , and sometimes called Ngwane or Swatini, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa, bordered to the north, south and west by South Africa, and to the east by Mozambique...

).

In 1828 Shaka was killed by his half-brothers Dingaan

Dingane

Dingane kaSenzangakhona Zulu —commonly referred to as Dingane or Dingaan—was a Zulu chief who became king of the Zulu Kingdom in 1828...

and Umhlangana. The weaker and less-skilled Dingaan became king, relaxing military discipline while continuing the despotism. Dingaan also attempted to establish relations with the British traders on the Natal coast, but events had started to unfold that would see the demise of Zulu independence.

The Great Trek

Meanwhile, the Boers had started to grow increasingly dissatisfied with British rule in the Cape Colony

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony, part of modern South Africa, was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, with the founding of Cape Town. It was subsequently occupied by the British in 1795 when the Netherlands were occupied by revolutionary France, so that the French revolutionaries could not take...

. The British proclamation of the equality of the races particularly angered them, and they were also unhappy with the process of payment of compensation for slave-owners whose slaves had been freed. Beginning in 1835, several groups of Boers, together with large numbers of Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi

The Khoikhoi or Khoi, in standardised Khoekhoe/Nama orthography spelled Khoekhoe, are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group, the native people of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen . They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD...

and black servants, decided to trek off into the interior in search of greater independence

Independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state in which its residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory....

. North and east of the Orange River

Orange River

The Orange River , Gariep River, Groote River or Senqu River is the longest river in South Africa. It rises in the Drakensberg mountains in Lesotho, flowing westwards through South Africa to the Atlantic Ocean...

(which formed the Cape Colony's frontier) these Boers or Voortrekkers

Voortrekkers

The Voortrekkers were emigrants during the 1830s and 1840s who left the Cape Colony moving into the interior of what is now South Africa...

("Pioneer

Settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established permanent residence there, often to colonize the area. Settlers are generally people who take up residence on land and cultivate it, as opposed to nomads...

s") found vast tracts of apparently uninhabited grazing lands. They had, it seemed, entered their promised land, with space enough for their cattle to graze and their culture of anti-urban independence to flourish. Little did they know that what they found – deserted pasture

Pasture

Pasture is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep or swine. The vegetation of tended pasture, forage, consists mainly of grasses, with an interspersion of legumes and other forbs...

lands, disorganised bands of refugee

Refugee

A refugee is a person who outside her country of origin or habitual residence because she has suffered persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or because she is a member of a persecuted 'social group'. Such a person may be referred to as an 'asylum seeker' until...

s, and tales of brutality – resulted from the difaqane, rather than representing the normal state of affairs.

With the exception of the more powerful Ndebele, the Voortrekkers encountered little resistance among the scattered peoples of the plain

Plain

In geography, a plain is land with relatively low relief, that is flat or gently rolling. Prairies and steppes are types of plains, and the archetype for a plain is often thought of as a grassland, but plains in their natural state may also be covered in shrublands, woodland and forest, or...

s. The difaqane had dispersed them, and the remnants lacked horses and firearm

Firearm

A firearm is a weapon that launches one, or many, projectile at high velocity through confined burning of a propellant. This subsonic burning process is technically known as deflagration, as opposed to supersonic combustion known as a detonation. In older firearms, the propellant was typically...

s. Their weakened condition also solidified the Boers' belief that European occupation meant the coming of civilisation to a savage land. However, the mountains where King Moshoeshoe I had started to forge the Basotho nation that would later become Lesotho and the wooded valleys of Zululand

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

proved a more difficult proposition. Here the Boers met strong resistance, and their incursions set off a series of skirmishes, and treaties

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

that would litter the next 50 years of increasing white domination.

British, Boers and Zulus

Great Trek

The Great Trek was an eastward and north-eastward migration away from British control in the Cape Colony during the 1830s and 1840s by Boers . The migrants were descended from settlers from western mainland Europe, most notably from the Netherlands, northwest Germany and French Huguenots...

first halted at Thaba Nchu

Thaba Nchu

Thaba Nchu is a town in Free State, South Africa, located 60 km east of Bloemfontein. Its population is largely made up of Tswana and Sotho people. The town was settled in the 1830s and officially established in 1873...

, near present-day Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein is the capital city of the Free State Province of South Africa; and, as the judicial capital of the nation, one of South Africa's three national capitals – the other two being Cape Town, the legislative capital, and Pretoria, the administrative capital.Bloemfontein is popularly and...

, where the trekkers established a republic. Following disagreements among their leadership

Leadership

Leadership has been described as the “process of social influence in which one person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task". Other in-depth definitions of leadership have also emerged.-Theories:...

, the various Voortrekker groups split apart. While some headed north, most crossed the Drakensberg

Drakensberg

The Drakensberg is the highest mountain range in Southern Africa, rising to in height. In Zulu, it is referred to as uKhahlamba , and in Sesotho as Maluti...

into Natal with the idea of establishing a republic there.

Since the Zulus controlled this territory, the Voortrekker leader, accompanied by about 70 men of his Trek-Boer community, Piet Retief

Piet Retief

Pieter Mauritz Retief was a South African Boer leader. Settling in 1814 in the frontier region of the Cape Colony, he assumed command of punitive expeditions in response to raiding parties from the adjacent Xhosa territory...

paid a visit to King Dingane kaSenzangakhona (Shaka's brother). Dingane promised them land in payment for a favour. The Batlokwa people, under chief Sekonyela had stolen cattle from him and he wanted it back. Retief went to them and retrieved the cattle. After receiving the specified cattle, Dingane invited Retief and his men into his kraal, where they were given all the land between the iZimvubu and Tugela rivers up to the Drakensberg. The treaty between the two men currently sits in a museum in The Netherlands. As a celebration, Dingane invited Retief and all his men to come and drink uTshwala (Traditional Zulu Beer) in his kraal, but the Boers had to leave all their weapons outside. Also included in the offer were guns and money. While drinking and being entertained by Zulu dancers, Dingane cried out "Bulalani abathakathi" (Kill the wizards"; also sometimes reported as "Bambani abathakathi", "Seize the wizards"). Dingane's men, having taken Retief's men by surprise, dragged the men to a hill Hloma Mabuto (or perhaps kwaMatiwane) where, one by one, they were all killed, leaving Retief for last so that he could watch.

After the massacre, the impis went back to the encampment where Retief and his fellow farmers had left their wives, children and livestock. Taken by surprise, the women, children and remaining farmers (numbering about 500) were also killed at the site called "Weenen", but not without retribution, they themselves managed to stop the initial onslaught and managed to get away, without many of their guns and animals. A missionary, Rev. Owen, had seen all of this take place and approached Dingane in order to give the dead an appropriate burial. While the reverend and a helper of his were burying the dead and reading them their last rights, they happened to come across Retief's rucksack, still containing the treaty and a few personal belongings.

At the Battle of Itala, a Boer army's attempt at revenge failed miserably. The culmination came on 16 December 1838, at the Ncome River in Natal. The Boers established a defensive enclosure or laager before the Zulu attack. Though only three Boers suffered injuries, they killed about three thousand Zulu warriors using three cannons and an elephant gun (along with other weapons). Before the battle, on 9 December 1838, the Boers made a vow to God that if He protected them and defeated their enemy, they will build a church in His name and they and their offspring will remember the day and the date. In remembrance of this vow, 16 December became a South African public holiday in the 1920s. So much bloodshed reportedly caused the Ncome's waters to run red, thus the clash is historically known as the Battle of Blood River

Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River, so called due to the colour of water in the Ncome River turning red with blood, was fought between 470 Voortrekkers led by Andries Pretorius, and an estimated 10,000–15,000 Zulu attackers on the bank of the Ncome River on 16 December 1838, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal,...

.

Divinity

Divinity and divine are broadly applied but loosely defined terms, used variously within different faiths and belief systems — and even by different individuals within a given faith — to refer to some transcendent or transcendental power or deity, or its attributes or manifestations in...

approval. Yet their hopes for establishing a Natal republic remained short lived. The British annexed the area in 1843, and founded their new Natal colony at present-day Durban

Durban

Durban is the largest city in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal and the third largest city in South Africa. It forms part of the eThekwini metropolitan municipality. Durban is famous for being the busiest port in South Africa. It is also seen as one of the major centres of tourism...

. Most of the Boers, feeling increasingly squeezed between the British on one side and the native African populations on the other, headed north.

The British set about establishing large sugar plantation

Plantation

A plantation is a long artificially established forest, farm or estate, where crops are grown for sale, often in distant markets rather than for local on-site consumption...

s in Natal, but found few inhabitants of the neighbouring Zulu areas willing to provide labour. The British confronted stiff resistance to their encroachments from the Zulus, a nation with well-established traditions of waging war, who inflicted one of the most humiliating defeats on the British army at the Battle of Isandlwana

Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom...

in 1879, where over 1400 British soldiers were killed. During the ongoing Anglo-Zulu War

Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom.Following the imperialist scheme by which Lord Carnarvon had successfully brought about federation in Canada, it was thought that a similar plan might succeed with the various African kingdoms, tribal areas and...

s, the British eventually established their control over what was then named Zululand

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

, and is today known as KwaZulu-Natal Province.

The British turned to India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

to resolve their labour shortage, as Zulu men refused to adopt the servile position of labourers and in 1860 the SS Truro arrived in Durban harbour with over 300 people on board. Over the next 50 years, 150,000 more indentured

Indentured servant

Indentured servitude refers to the historical practice of contracting to work for a fixed period of time, typically three to seven years, in exchange for transportation, food, clothing, lodging and other necessities during the term of indenture. Usually the father made the arrangements and signed...

Indians arrived, as well as numerous free "passenger Indians", building the base for what would become the largest Indian community outside of India. As early as 1893, when Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , pronounced . 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was the pre-eminent political and ideological leader of India during the Indian independence movement...

arrived in Durban, Indians outnumbered whites in Natal. (See Asians in South Africa

Asians in South Africa

The majority of the Asian South African population is Indian in origin, most of them descended from indentured workers transported to work in the 19th century on the sugar plantations of the eastern coastal area, then known as Natal. They are largely English speaking, although many also retain the...

.)

The Boer republics

Boer Republics

The Boer Republics were independent self-governed republics created by the northeastern frontier branch of the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of the north eastern Cape Province and their descendants in mainly the northern and eastern parts of what is now the country of...

, e.g. the Transvaal or South African Republic

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

and the Orange Free State

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State was an independent Boer republic in southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, and later a British colony and a province of the Union of South Africa. It is the historical precursor to the present-day Free State province...

. For a while it seemed that these republics would develop into stable states, despite having thinly spread populations of fiercely independent Boers, no industry, and minimal agriculture. The discovery of diamonds near Kimberley turned the Boers' world on its head (1869). The first diamonds came from land belonging to the Griqua, but to which both the Transvaal and Orange Free State laid claim. Britain quickly stepped in and resolved the issue by annexing the area for itself.

The discovery of the Kimberley diamond-mines

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

unleashed a flood of European and black labourers into the area. Towns sprang up in which the inhabitants ignored the "proper" separation of whites and blacks, and the Boers expressed anger that their impoverished republics had missed out on the economic benefits of this Mineral Revolution

Mineral Revolution

The Mineral Revolution is a term used by historians to refer to the rapid industrialisation and economic changes which occurred in South Africa from the 1870s onwards. The Mineral Revolution was largely driven by the need to create a permanent workforce to work in the mining industry, and saw South...

.

Anglo-Boer Wars

First Anglo-Boer War

Long-standing Boer resentment turned into full-blown rebellion in the Transvaal (under British control from 1877), and the first Anglo-Boer WarFirst Boer War

The First Boer War also known as the First Anglo-Boer War or the Transvaal War, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881-1877 annexation:...

, known to Afrikaner

Afrikaner

Afrikaners are an ethnic group in Southern Africa descended from almost equal numbers of Dutch, French and German settlers whose native tongue is Afrikaans: a Germanic language which derives primarily from 17th century Dutch, and a variety of other languages.-Related ethno-linguistic groups:The...

s as the "War of Independence", broke out in 1880. The conflict ended almost as soon as it began with a crushing Boer victory at Battle of Majuba Hill

Battle of Majuba Hill

The Battle of Majuba Hill on 27 February 1881 was the main battle of the First Boer War. It was a resounding victory for the Boers. Major-General Sir George Pomeroy Colley occupied the summit of the hill on the night of February 26–27, 1881. His motive for occupying the hill remains unclear...

(27 February 1881). The republic regained its independence as the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek ("South African Republic

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

"), or ZAR. Paul Kruger

Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger , better known as Paul Kruger and affectionately known as Uncle Paul was State President of the South African Republic...

, one of the leaders of the uprising, became President of the ZAR in 1883. Meanwhile, the British, who viewed their defeat at Majuba as an aberration, forged ahead with their desire to federate

Federation

A federation , also known as a federal state, is a type of sovereign state characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions united by a central government...

the Southern African colonies and republics. They saw this as the best way to come to terms with the fact of a white Afrikaner majority, as well as to promote their larger strategic interests in the area.

Inter-war period

In 1879 Zululand came under British control. Then in 1886 an Australian prospector discovered goldWitwatersrand Gold Rush

The Witwatersrand Gold Rush was a gold rush in 1886 that led to the establishment of Johannesburg, South Africa. It was part of the Mineral Revolution....

in the Witwatersrand

Witwatersrand

The Witwatersrand is a low, sedimentary range of hills, at an elevation of 1700–1800 metres above sea-level, which runs in an east-west direction through Gauteng in South Africa. The word in Afrikaans means "the ridge of white waters". Geologically it is complex, but the principal formations...

, accelerating the federation process and dealing the Boers yet another blow. Johannesburg

Johannesburg

Johannesburg also known as Jozi, Jo'burg or Egoli, is the largest city in South Africa, by population. Johannesburg is the provincial capital of Gauteng, the wealthiest province in South Africa, having the largest economy of any metropolitan region in Sub-Saharan Africa...

's population exploded to about 100,000 by the mid-1890s, and the ZAR suddenly found itself hosting thousands of uitlanders, both black and white, with the Boers squeezed to the sidelines. The influx of Black labour in particular worried the Boers, as the shortage of jobs meant that they would suffer further economic hardships.

The enormous wealth of the mines, largely controlled by European "Randlord

Randlord

Randlord is a term used to denote the entrepreneurs who controlled the diamond and gold mining industries in South Africa in its pioneer phase from the 1870s up to World War I....

s" soon became irresistible for the British. In 1895, a group of renegades led by Captain Leander Starr Jameson

Leander Starr Jameson

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, KCMG, CB, , also known as "Doctor Jim", "The Doctor" or "Lanner", was a British colonial statesman who was best known for his involvement in the Jameson Raid....

entered the ZAR with the intention of sparking an uprising on the Witwatersrand and installing a British administration. This incursion became known as the Jameson Raid

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid was a botched raid on Paul Kruger's Transvaal Republic carried out by a British colonial statesman Leander Starr Jameson and his Rhodesian and Bechuanaland policemen over the New Year weekend of 1895–96...

. The scheme ended in fiasco, but it seemed obvious to Kruger that it had at least the tacit approval of the Cape Colony government, and that his republic faced danger. He reacted by forming an alliance with Orange Free State.

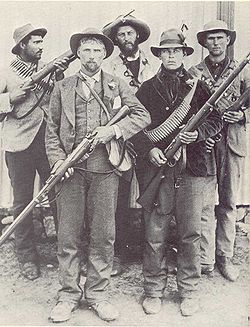

Second Anglo-Boer War

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

. Kruger rejected the British demand and called for the withdrawal of British troops from the ZAR's borders. When the British refused, Kruger declared war. This Second Anglo-Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

lasted longer than the first, and the British preparedness surpassed that of Majuba Hill. By June 1900, Pretoria

Pretoria

Pretoria is a city located in the northern part of Gauteng Province, South Africa. It is one of the country's three capital cities, serving as the executive and de facto national capital; the others are Cape Town, the legislative capital, and Bloemfontein, the judicial capital.Pretoria is...

, the last of the major Boer towns, had surrendered. Yet resistance by Boer bittereinder

Bittereinder

Bittereinders were a faction of Boer guerrilla fighters, resisting the forces of the British Empire in the later stages of the Second Boer War ....

s continued for two more years with guerrilla-style battles, which the British met in turn with scorched earth

Scorched earth

A scorched earth policy is a military strategy or operational method which involves destroying anything that might be useful to the enemy while advancing through or withdrawing from an area...

tactics. By 1902 26,000 women and children had died of disease and neglect in concentration camps. On 31 May 1902 a superficial peace came with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging

Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was the peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the South African War between the South African Republic and the Republic of the Orange Free State, on the one side, and the British Empire on the other.This settlement provided for the end of hostilities and...

. Under its terms, the Boer republics acknowledged British sovereignty, while the British in turn committed themselves to reconstruction of the areas under their control.

Union of South Africa

During the immediate post-war years the British focussed their attention on rebuilding the country, in particular the mining industry. By 1907 the mines of the Witwatersrand produced almost one-third of the world's annual gold production. But the peace brought by the treaty remained fragile and challenged on all sides. The Afrikaners found themselves in the ignominious position of poor farmers in a country where big mining ventures and foreign capitalCapital (economics)

In economics, capital, capital goods, or real capital refers to already-produced durable goods used in production of goods or services. The capital goods are not significantly consumed, though they may depreciate in the production process...

rendered them irrelevant. Britain's unsuccessful attempts to Anglicise them, and to impose English as the official language in schools and the workplace

Office

An office is generally a room or other area in which people work, but may also denote a position within an organization with specific duties attached to it ; the latter is in fact an earlier usage, office as place originally referring to the location of one's duty. When used as an adjective, the...

particularly incensed them. Partly as a backlash to this, the Boers came to see Afrikaans

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic language, spoken natively in South Africa and Namibia. It is a daughter language of Dutch, originating in its 17th century dialects, collectively referred to as Cape Dutch .Afrikaans is a daughter language of Dutch; see , , , , , .Afrikaans was historically called Cape...

as the volkstaal ("people's language") and as a symbol of Afrikaner nationhood

Afrikaner nationalism

Afrikaner nationalism is a political ideology that was born in the late 19th century around the idea that Afrikaners in South Africa were a "chosen people"; it was also strongly influenced by anti-British sentiments that grew strong among the Afrikaners, especially because of the Boer Wars...

. Several nationalist organisations sprang up.

The system left Blacks and Coloureds completely marginalised. The authorities imposed harsh taxes and reduced wages, while the British caretaker administrator encouraged the immigration of thousands of Chinese to undercut any resistance. Resentment exploded in the Bambatha Rebellion

Bambatha Rebellion

The Bambatha Uprising was a Zulu revolt against British rule and taxation in Natal, South Africa, in 1906. The revolt was led by Bambatha kaMancinza The Bambatha Uprising was a Zulu revolt against British rule and taxation in Natal, South Africa, in 1906. The revolt was led by Bambatha kaMancinza...

of 1906, in which 4,000 Zulus lost their lives after protesting against onerous tax legislation.

The British meanwhile moved ahead with their plans for union. After several years of negotiations, the South Africa Act 1909

South Africa Act 1909

The South Africa Act 1909 was an Act of the British Parliament which created the Union of South Africa from the British Colonies of the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, Orange River Colony, and the Transvaal Colony. The Act also made provisions for admitting Rhodesia as a fifth province of the Union in...

brought the colonies and republics – Cape Colony, Natal, Transvaal, and Orange Free State – together as the Union of South Africa

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa is the historic predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into being on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the previously separate colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State...

. Under the provisions of the act, the Union remained British territory, but with home-rule for Afrikaners. The British High Commission territories of Basutoland

Basutoland

Basutoland or officially the Territory of Basutoland, was a British Crown colony established in 1884 after the Cape Colony's inability to control the territory...

(now Lesotho

Lesotho

Lesotho , officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a landlocked country and enclave, surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It is just over in size with a population of approximately 2,067,000. Its capital and largest city is Maseru. Lesotho is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The name...

), Bechuanaland (now Botswana

Botswana

Botswana, officially the Republic of Botswana , is a landlocked country located in Southern Africa. The citizens are referred to as "Batswana" . Formerly the British protectorate of Bechuanaland, Botswana adopted its new name after becoming independent within the Commonwealth on 30 September 1966...

), Swaziland

Swaziland

Swaziland, officially the Kingdom of Swaziland , and sometimes called Ngwane or Swatini, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa, bordered to the north, south and west by South Africa, and to the east by Mozambique...

, and Rhodesia

Rhodesia

Rhodesia , officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state located in southern Africa that existed between 1965 and 1979 following its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965...

(now Zambia

Zambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

and Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country located in the southern part of the African continent, between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers. It is bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the southwest, Zambia and a tip of Namibia to the northwest and Mozambique to the east. Zimbabwe has three...

) continued under direct rule from Britain.

English and Dutch became the official languages. Afrikaans did not gain recognition as an official language until 1925. Despite a major campaign by Blacks and Coloureds, the voter franchise remained as in the pre-Union republics and colonies, and only whites could gain election to parliament

Parliament of South Africa

The Parliament of South Africa is South Africa's legislature and under the country's current Constitution is composed of the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces....

.

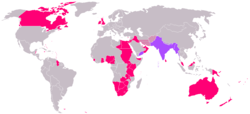

Most significantly, the new Union of South Africa gained international respect with British Dominion status putting it on par with three other important British dominions and allies: Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Segregationist legislation also included the Franchise and Ballot Act (1892), which limited the black vote by finance and education, the Natal Legislative Assembly Bill (1894), which deprived Indians of the right to vote; the General Pass Regulations Bill (1905), which denied blacks the vote altogether, limited them to fixed areas and inaugurated the infamous Pass System; the Asiatic Registration Act (1906) requiring all Indians to register and carry passes; the South Africa Act (1910) that enfranchised whites, giving them complete political control over all other race groups; the above-mentioned Native Land Act (1913) which prevented all blacks, except those in the Cape, from buying land outside 'reserves'. The reserves were the "original homes" of the black tribes of South Africa. The reserves later became known as bantustan

Bantustan

A bantustan was a territory set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa , as part of the policy of apartheid...

s of which the failed objective was to make self-governing, quasi-independent ethnically homogeneous states. At this time the state effectively reserved 87% of the land which whites exclusively could purchase; the Natives in Urban Areas Bill (1918) designed to move blacks living in "white" South Africa into specific 'locations' as a precautionary security measure; the Urban Areas Act (1923) which introduced residential segregation

Residential Segregation

Residential segregation is the physical separation of cultural groups based on residence and housing, or a form of segregation that "sorts population groups into various neighborhood contexts and shapes the living environment at the neighborhood level."...

in South Africa and provided cheap unskilled labour for the white mining and farming industry; the Colour Bar Act (1926), preventing blacks from practising skilled trades; the Native Administration Act (1927) that made the British Crown, rather than paramount chiefs, the supreme head over all African affairs; the Native Land and Trust Act (1936) that complemented the 1913 Native Land Act and, in the same year, the Representation of Natives Act, which removed blacks from the Cape voters' roll. The final 'apartheid' legislation passed by the South African parliament before the beginning of the 'Apartheid' era was the Asiatic Land Tenure Bill (1946), which banned any further land sales to Indians.

Participation in World Wars

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, South Africa joined Great Britain and the Allies against the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. Both Prime Minister Louis Botha

Louis Botha

Louis Botha was an Afrikaner and first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa—the forerunner of the modern South African state...

and Defence Minister Jan Smuts

Jan Smuts

Jan Christiaan Smuts, OM, CH, ED, KC, FRS, PC was a prominent South African and British Commonwealth statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 until 1924 and from 1939 until 1948...

, were former Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

generals who had fought against the British then, but they now became active and respected members of the Imperial War Cabinet

Imperial War Cabinet

The Imperial War Cabinet was created by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George in the spring of 1917 as a means of co-ordinating the British Empire's military policy during the First World War...

. Elements of the South African army refused to fight against the Germans and along with other opponents of the government they rose in an open revolt known as the Maritz Rebellion

Maritz Rebellion

The Maritz Rebellion or the Boer Revolt or the Five Shilling Rebellion, occurred in South Africa in 1914 at the start of World War I, in which men who supported the recreation of the old Boer republics rose up against the government of the Union of South Africa...

. The government declared martial law on 14 October 1914, and forces loyal to the government under the command of General Louis Botha and Jan Smuts proceeded to destroy the rebellion. The leading Boer activists were convicted and given terms of imprisonment of six and seven years and heavy fines.

Nearly a quarter million South Africans served in South African military units in supporting the Allies during World War I. This included 43,000 in German South-West Africa and 30,000 on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

. An estimated 3,000 South Africans also joined the Royal Flying Corps

Royal Flying Corps