Presidency of Jimmy Carter

Encyclopedia

Jimmy Carter

served as the thirty-ninth President of the United States

from 1977 to 1981. His administration sought to make the government "competent and compassionate" but, in the midst of an economic crisis produced by rising energy prices

and stagflation

, met with difficulty in achieving its objectives. At the end of his administration, Carter had substantively reduced both unemployment and the deficit but had not been able to completely eliminate the recession. Carter created the United States Department of Education

and United States Department of Energy

, established a national energy policy

and pursued civil service and social security reform. In foreign affairs, Carter initiated the Camp David Accords

, the Panama Canal Treaties and the second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

(SALT II). Throughout his career, Carter strongly emphasized human rights. He returned the Panama Canal Zone

to Panama and he faced criticism at home for his decision, which was widely seen as yet another signal of U.S. weakness and of his own habit of backing down when faced with confrontation. The final year of his presidential tenure was marked by several major crises, including the 1979 takeover of the American embassy in Iran

and holding of hostages

by Iranian students, an unsuccessful rescue attempt

of the hostages, serious fuel shortages

, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

.

Carter had campaigned on a promise to eliminate the trappings of the "Imperial Presidency

," and he began taking action according to that promise on Inauguration Day, breaking with recent history and security protocols by walking up Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol

to the White House

in his inaugural parade. His first steps in the White House went further in this direction: Carter reduced the size of the staff by one-third; canceled government-funded chauffeur

service for Cabinet

members, ordering them to drive their own cars; and put the USS Sequoia

, the presidential yacht

up for sale.

Others:

, he appointed 56 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals

, and 203 judges to the United States district courts. Carter also experienced a small number of judicial appointment controversies

, as three of his nominees for different federal appellate judgeships

were not processed by the Democratic-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee

before Carter's presidency ended.

and the Department of Health and Human Services

. He signed into law a major Civil Service Reform, the first in over 100 years.

On Carter's first day in office, January 20, 1977, he fulfilled a campaign promise by issuing an executive order declaring unconditional amnesty

On Carter's first day in office, January 20, 1977, he fulfilled a campaign promise by issuing an executive order declaring unconditional amnesty

for Vietnam War

-era draft evaders.

Under Carter's watch, the Airline Deregulation Act

of 1978 was passed, which phased out the Civil Aeronautics Board. He also enacted deregulation

in the trucking, rail, communications, and finance industries.

Among Presidents who served at least one full term, Carter is the only one who never made an appointment to the Supreme Court

.

Carter was the first president to address the topic of gay

rights. He opposed the Briggs Initiative, a California

ballot measure that would have banned gay

s and supporters of gay rights from being public school teachers. His administration was the first to meet with a group of gay rights activists, and in recent years he has acted in favor of civil unions and ending the ban on gays in the military. He has stated that he "opposes all forms of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation

and believes there should be equal protection under the law for people who differ in sexual orientation".

The federal government was in deficit every year of the Carter presidency. His Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

created 103 million acre

s (417,000 km²) of national park land in Alaska

.

from the start. Unreturned phone calls, verbal insults (both real and imagined), and an unwillingness to trade political favors soured many on Capitol Hill and tangibly affected the president's ability to push through his ambitious agenda.

During the first 100 days of his presidency, Carter wrote a letter to Congress proposing several water projects be scrapped. Among the opponents of Carter's proposal was Senator Russell Long, a powerful Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee

. Carter's plan was overturned and bitter feeling became a problem for him.

A rift grew between the White House and Congress. Carter wrote that the most intense and mounting opposition to his policies came from the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which he attributed to Ted Kennedy’s ambition to replace him as president.

A few months after his term started, and thinking he had the support of about 74 Congressmen, Carter issued a "hit list" of 19 projects that he claimed were "pork barrel

" spending. He said that he would veto any legislation that contained projects on this list.

This list met with opposition from the leadership of the Democratic Party. Carter had characterized a rivers and harbors bill as wasteful spending. House speaker Tip O'Neill

thought it was unwise for the President to interfere with matters that had traditionally been the purview of Congress. Carter was then further weakened when he signed into law a bill containing many of the "hit list" projects.

Later, Congress refused to pass major provisions of his consumer protection

bill and his labor reform package. Carter then vetoed a public works package calling it "inflationary", as it contained what he considered to be wasteful spending. Congressional leaders sensed that public support for his legislation was weak, and took advantage of it. After gutting his consumer protection bill, they transformed his tax plan into nothing more than spending for special interests, after which Carter referred to the congressional tax committees as "ravenous wolves."

’s disagreements with Carter's proposed health-care reform plan thwarted Carter’s efforts to provide comprehensive health-care

for citizens outside the Medicare

system.

Some progress was made in the field of occupational health following Carter's appointment of Dr. Eula Bingham

as Director of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

. Bingham drew from her experience as a physiologist working with carcinogen

s to raise and simplify standards, redirect the office's resources to industry groups with the worst records, while enacting occupational particulate, lead

and benzene

exposure standards and regulations on workers' right to know

about workplace hazards, including labeling of toxic substances. Bingham enacted many of these provisions over the opposition of not only Republicans, but also some in the Carter Admnistration itself, notably Council of Economic Advisers

Chairman Charles Schultze

and her own boss, Labor Secretary

Ray Marshall

; ultimately, many of her proposed reforms were never enacted, or were later rescinded.

In 1973, during the Nixon Administration

In 1973, during the Nixon Administration

, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) reduced supplies of oil

available to the world market, in part because of deflation of the dollars they were receiving as a result of Nixon leaving the gold standard

and in part as a reaction to America's sending of arms to Israel

during the Yom Kippur War

. This sparked the 1973 Oil Crisis

and forced oil prices to rise sharply, spurring price inflation throughout the economy and slowing growth. The U.S government imposed price controls

on gasoline

and oil

following the announcement, which had the effect of causing shortages and long lines at filling stations for gasoline. The lines were quelled through the lifting of price controls on gasoline, although oil controls remained until Reagan's presidency. Significant government borrowing helped keep interest rates high relative to inflation

. Carter told Americans that the energy crisis was "a clear and present danger to our nation" and "the moral equivalent of war

" and drew out a plan he thought would address it. Carter said that world oil supply would probably only be able to keep up with Americans' demand for six to eight more years.

In 1977, Carter convinced the Democratic Congress to create the United States Department of Energy

(DoE) with the goal of conserving energy

. Carter set oil and natural gas price controls, had solar hot water

panels installed on the roof of the White House, had a wood stove in his living quarters, ordered the General Services Administration

to turn off hot water in some federal facilities, and requested that all Christmas

light decorations remain dark in 1979 and 1980. Nationwide, controls were put on thermostat

s in government and commercial buildings to prevent people from raising temperatures in the winter (above 65 degrees Fahrenheit = 18.33 °C) or lowering them in the summer (below 78 degrees Fahrenheit = 25.55 °C).

As reaction to the energy crisis and growing concerns over air pollution

, Carter also signed the National Energy Act

(NEA) and the Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA). The purpose of these watershed laws was to encourage energy conservation and the development of national energy resources, including renewables

such as wind

and solar energy.

However, during the 1979 crisis, Carter reinstated some price controls on gasoline, which again had the effect of causing lines at gasoline stations. During his "malaise" speech he asked Congress to impose a "Windfall Profit Tax" to help pay for energy efficiency initiatives. Enacted in 1980 on domestic oil production, the tax was repealed in 1988, as prices had collapsed in the 1980s oil glut

, making it politically possible to remove the tax, said removal one of President Reagan's campaign issues.

at its lowest level since the 1970 recession and unemployment at 9%. The second two years were marked by double-digit inflation

, coupled with very high interest rates, oil shortages

, and slow economic growth. The nation's economy grew by an average of 3.4% during the Carter Administration (at par with the historical average). Each of these two-year periods, however, would differ dramatically.

The U.S. economy, which had grown by 5% in 1976, continued to grow at a similar pace during 1977 and 1978. Unemployment declined from 7.5% in January 1977 to 5.6% by May 1979, with over 9 million net new jobs created during that interim, and real median household income grew by 5% from 1976 to 1978. The recovery in business investment in evidence during 1976 strengthened as well. Fixed private investment (machinery and construction) grew by 30% from 1976 to 1979, home sales and construction grew another one third by 1978, and industrial production, motor vehicle output and sales did so by nearly 15%; with the exception of new housing starts, which remained slightly below their 1972 peak, each of these benchmarks reached record levels in 1978 or 1979.

The 1979 energy crisis

ended this period of growth, however, and as both inflation and interest rates rose, economic growth, job creation, and consumer confidence

declined sharply. The relatively loose monetary policy

adopted by Federal Reserve Board Chairman G. William Miller

, had already contributed to somewhat higher inflation

, rising from 5.8% in 1976 to 7.7% in 1978. The sudden doubling of crude oil prices by OPEC

, the world's leading oil exporting cartel

, forced inflation to double-digit levels, averaging 11.3% in 1979 and 13.5% in 1980. The sudden shortage of gasoline

as the 1979 summer vacation season began exacerbated the problem, and would come to symbolize the crisis among the public in general; the acute shortage, originating in the shutdown of Amerada Hess refining facilities, led to a lawsuit against the company that year by the Federal Government.

Carter, like Nixon, asked Congress to impose price controls

on energy, medicine, and consumer prices, but was unable to secure passage of such measures due to strong opposition from Congress. One related measure approved by Congress during the presidency of Gerald Ford

, the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, gave Presidents the authority to deregulate prices of domestic oil

, and Carter exercised this option on July 1, 1979, as a means of encouraging both oil production and conservation. Oil imports, which had reached a record 2.4 billion barrels in 1977 (50% of supply), declined by half from 1979 to 1983.

Following a August 1979 cabinet shakeup in which Carter asked for the resignations of several cabinet members (see "Malaise speech" below), Carter appointed G. William Miller

as Secretary of the Treasury, naming Paul Volcker

as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Volcker pursued a tight monetary policy

to bring down inflation, which he considered his mandate. Volcker (and Carter) succeeded, but only by first going through an unpleasant phase during which the economy slowed and unemployment

rose. Inflation did not return to low single-digit levels until 1982, during a second, more severe recession; President Reagan re-appointed Volcker to the post in 1983.

Led by Volcker, the Federal Reserve raised the discount rate from 10% when Volcker assumed the chairmanship in August 1979 to 12% within two months. The prime rate

outstripped the Federal funds rate

, reaching 20% in March 1980. Carter then enacted an austerity

program by executive order, justifying these measures by observing that inflation had reached a "crisis stage"; both inflation and short-term interest rates reached 18 percent in February and March of 1980. Investments in fixed income (both bond

s held by Wall Street and pension

s paid to retired people

) were becoming less valuable in real term

s, and on March 14, 1980, President Carter announced the first credit control measures since World War II

.

The policy, as well as record interest rates, would lead to a sharp recession in the spring of 1980

. The sudden fall in GDP during the second quarter caused unemployment to jump from 6% to 7.5% by May, with output in the auto and housing sectors falling by over 20% and to their weakest level since the 1975 recession. Carter phased out credit controls in May, and by July, the prime rate

had fallen to 11%, with inflation breaking the earlier trend and easing to under 13% for the remainder of 1980. The V-shaped recession

coincided with Carter's re-election campaign, however, and contributed to his unexpectedly severe loss.

Lower interest rates and easing of credit controls sparked a recovery during the second half of 1980, and although the hard-hit auto and housing sectors would not recover substantially, GDP and employment totals regained pre-recession levels by the first quarter of 1981. The S&P 500

(which had remained at around 100 since 1976), rose to nearly 140 by the latter part of the year. A resumption in growth prompted renewed tightening by the Fed, however, and the prime rate reached 21.5% in December 1980, the highest rate in U.S. history under any President. The Carter Administration remained fiscally conservative during both growth and recession periods, vetoing numerous spending increases while enacting deregulation

in the energy and transportation sectors and sharply reducing the top capital gains tax

rate. Federal budget deficits

throughout his term remained at around the $ 70 billion level reached in 1976, while falling as a percent of GDP from 4% to 2.5% by the 1980–81 Fiscal Year.

, he was planning on delivering his fifth major speech on energy; however, he felt that the American people were no longer listening. Carter left for the presidential retreat of Camp David

. "For more than a week, a veil of secrecy enveloped the proceedings. Dozens of prominent Democratic Party leaders—members of Congress, governors, labor leaders, academics and clergy—were summoned to the mountaintop retreat to confer with the beleaguered president." His pollster, Pat Caddell, told him that the American people simply faced a crisis of confidence because of the assassinations of John F. Kennedy

, Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Vietnam War

; and Watergate

. On July 15, 1979, Carter gave a nationally-televised address in which he identified what he believed to be a "crisis of confidence" among the American people. This came to be known as his "malaise

" speech, although the word never appeared in it:

Carter's speech was written by Hendrik Hertzberg

and Gordon Stewart. Though it is often said to have been ill-received, The New York Times

ran the headline "Speech Lifts Carter Rating to 37%; Public Agrees on Confidence Crisis; Responsive Chord Struck" later that week.

Carter's later election loss may have turned other politicians off the idea of asking Americans to conserve energy in a similar way. Three days after the speech, Carter asked for the resignations of all of his Cabinet officers, and ultimately accepted those of five who had clashed with the White House the most, including Energy Secretary James Schlesinger and Health, Education and Welfare chief Joseph Califano, known as a supporter of Senator Ted Kennedy

. After campaigning that he would never appoint a Chief of Staff, Carter appointed Jordan as a new White House Chief of Staff. Many in the administration chafed when Jordan circulated a "questionnaire" that read more like a loyalty oath. "I think the idea was that they were going to firm up the administration, show that there was real change by these personnel changes, and move on," remembers Mondale. "But the message the American people got was that we were falling apart." Carter later admitted in his memoirs that he should simply have asked only those five members for their resignations. In 2008, a U.S. News and World Report piece stated:

, a United States federal law designed to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances.

He also installed a 32 solar-powered heating system on the White House roof On June 20, 1979, to promote the use of solar energy.

On December 2, 1980, he signed into law Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

. The law provided for the creation or revision of 15 National Park Service properties, and set aside other public lands for the United States Forest Service and United States Fish and Wildlife Service. In all, the act provided for the designation of 79.53 million acres (124,281 square miles; 321,900 km²) of public lands, fully a third of which was set aside as wilderness area in Alaska

.

spacecraft for its trip outside our solar system on September 5, 1977:

s from South Korea

and announce his intention to cut back the number of US troops stationed there. Other military men confined intense criticism of the withdrawal to private conversations or testimony before congressional committees, but in 1977 Major General John K. Singlaub

, chief of staff of U.S. forces in South Korea, publicly criticized Carter's decision to lower the U.S. troop level there. On March 21, 1977, Carter relieved him of duty, saying his publicly stated sentiments were "inconsistent with announced national security policy." Carter planned to remove all U.S. troops, with the exception of 14,000 U.S. air force personnel and logistics specialists, from South Korea by 1982, but after cutting only 3,600 troops, he was forced by intense Congressional pressure to abandon the effort in 1978.

Carter's Secretary of State Cyrus Vance

Carter's Secretary of State Cyrus Vance

and National Security Advisor

Zbigniew Brzezinski

paid close attention to the Arab–Israeli conflict

. Diplomatic communications between Israel

and Egypt

increased significantly after the Yom Kippur War

and the Carter administration felt that the time was right for comprehensive solution to the conflict.

In mid-1978, Carter became quite concerned as there were only a few months left before the Egyptian-Israeli Disengagement Treaty expired. As a result, Carter sent a special envoy to the Middle East

. The American Ambassador flew back and forth between Cairo

and Tel Aviv

in search of ways to narrow the disagreement between the two countries. It was then suggested that the foreign ministers meet at Leeds Castle

, England where they could discuss the possibilities of peace. They tried to come to an agreement, but the foreign ministers failed. This led to the 1978 Camp David Accords

, one of Carter's most important accomplishments as President. The accords were a peace agreement between Israel and Egypt negotiated by Carter, which followed up on earlier negotiations conducted in the Middle East. In these negotiations King Hassan II of Morocco

acted as a negotiator between Arab

interests and Israel, and Nicolae Ceauşescu

of Romania acted as go-between for Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization

(PLO, the unofficial representative of the Palestinian people

). Once initial negotiations had been completed, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat

approached Carter for assistance. Carter then invited Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin

and Anwar El Sadat to Camp David

to continue the negotiations. They arrived on August 8, 1978. Upon their arrival, neither leader had addressed one another since the Vienna meeting. President Carter inevitably became the mediator between the two leaders. He spoke to each leader separately until an agreement was reached. Almost a month had passed, but no resolution had been reached. President Carter decided to take the two of them on a trip to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to break this deadlock. He showed the two leaders the battlefield and gave them a history lesson about one of the battles

that had taken place during the U.S. Civil War. Carter emphasized how important it was to have peace in order to bring prosperity to the people. A lesson was learned, and when Begin and Sadat returned to Camp David, they finally agreed that something had to be signed.

On September 12, 1978, President Carter suggested dividing the negotiations over the peace treaty into two frameworks: framework #1 and framework #2. Framework #1 would address the West Bank and Gaza. Framework #2 would deal with Sinai.

The first framework dealt with the Palestinian territories

(the West Bank and Gaza). The first point stated that the election of a self-governing authority would be allowed to provide full autonomy to the inhabitants of the West Bank

and Gaza

. This government would be elected by the Palestinians and would only look after municipal affairs. The second step would be to grant Palestinians autonomy mainly on those municipal matters. Five years down the road after having gone through steps one and two, the status of Palestine could then be negotiated. Framework #1 was not very well received; the Palestinians and Jordanians were furious. They objected to the fact that Begin and Sadat were deciding on their ultimate destiny without consulting them or their leaders. Framework #1 for that reason was not going to work; it was essentially a dead end.

The second framework dealt with the Sinai Peninsula

. This framework consisted of two points:

1. The two parties, Egypt and Israel, should negotiate a treaty over a period of six months based on the principle of Egyptian sovereignty over Sinai and the withdrawal of Israel from that region.

2. This treaty would be followed and included in it would be the establishment of diplomatic, political, economic, and cultural relations between Egypt and Israel.

President Carter admitted that "there's still great difficulties that remain and many hard issues to be settled." This would be a peace that would establish normal relations between the two states. This was the basis of the two frameworks, but it had yet to be approved.

The reaction to this proposal in the Arab world was very negative. In November 1978, there was an emergency meeting held by the Arab League in Damascus. Once again, Egypt was the main subject of the meeting, and they condemned the proposed treaty that Egypt was going to sign.

Sadat was also attacked by the Arab press for breaking ranks with the Arab League and having betrayed the Arab world. Discussions pertaining to the future peace treaty took place in both countries. Israel insisted in its negotiations that the Israel-Egypt treaty should supersede all of Egypt's other treaties, including those signed with the Arab League and Arab states.

Israel also wanted access to the oil discovered in the Sinai region. President Carter interjected and informed the Israelis that the U.S. would supply Israel with whatever oil it needed for the next 15 years if Egypt at any point decided not to supply oil to Israel.

While framework #1 was already approved by the Israeli Government, the second framework also needed approval. The Israeli Cabinet accepted the second framework of the treaty. The Israeli Parliament also approved the second framework with a comfortable majority. Alternatively, the Egyptian Government was arguing about a number of things. They did not like the fact that this proposed treaty was going to supersede all other treaties. Egyptians were also disappointed that they were unable to link the Sinai question to the Palestinian question.

On March 26, 1979, Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty in Washington, D.C. Carter's role in getting the treaty was essential. Aaron David Miller

interviewed many officials for his book The Much Too Promised Land (2008) and concluded the following: "No matter whom I spoke to — Americans, Egyptians, or Israelis — most everyone said the same thing: no Carter, no peace treaty."

(RDF), a mobile fighting force capable of responding to worldwide trouble spots, without drawing on forces committed to NATO. The RDF was the forerunner of CENTCOM

.

toward the Soviet Union. In its place, Carter promoted a foreign policy that put human rights

at the forefront. This was a break from the policies of several predecessors, in which human rights

abuses were often overlooked if they were committed by a government that was allied, or purported to be allied, with the United States.

He nominated civil rights

activist Patricia M. Derian

as Coordinator for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs, and in August 1977, had the post elevated to that of Assistant Secretary of State. Derian established the United States' Country Reports on Human Rights Practices

, published annually since 1977, and made their findings a factor in military aid

determinations, effectively ending such aid for five Latin American countries for the remainder of Carter's tenure. The Carter Administration ended support to the historically U.S.-backed Somoza

regime in Nicaragua

and gave aid to the new Sandinista National Liberation Front

government that assumed power after Somoza's overthrow. However, Carter ignored a plea from El Salvador

's Archbishop Óscar Romero

not to send military aid to that country; Romero was later assassinated for his criticism of El Salvador's violation of human rights. Generally, human rights in Latin America, which had deteriorated sharply in the previous decade, improved following these initiatives; a publisher tortured during Argentina

's Dirty War

, Jacobo Timerman

, credited these policies for the positive trend, stating that they not only saved lives, but also "built up democratic consciousness in the United States."

Many in his own administration were opposed to these initiatives, however, and the more assertive human rights policy of the Carter years was blunted by the discord that ensued between, on one hand, Derian and State Department Policy Planning Director Anthony Lake

, who endorsed human rights considerations as an enhancement of U.S. diplomatic effectiveness abroad, and National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski

, who held Cold War

considerations as paramount. These policy disputes reached their most contentious point during the 1979 fall of Pol Pot

's genocidal regime of Democratic Kampuchea

following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, when Brzezinski prevailed in having the administration refuse to recognize the new Cambodian government due to its support by the Soviet Union

. Carter was also criticized by the feminist author and activist Andrea Dworkin for ignoring issues of women's rights in Saudi Arabia

.

Carter continued his predecessors' policies of imposing sanctions on Rhodesia

, and, after Bishop Abel Muzorewa

was elected Prime Minister

, protested the exclusion of Robert Mugabe

and Joshua Nkomo

from participating in the elections. Strong pressure from the United States and the United Kingdom prompted new elections in what was then called Zimbabwe Rhodesia

(now Zimbabwe

), which saw Robert Mugabe elected as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe; afterwards, sanctions were lifted, and diplomatic recognition was granted. Carter was also known for his criticism of Paraguay

's Alfredo Stroessner

, Augusto Pinochet

(although both Stroessner and Pinochet, along with other Latin American dictators of whom Carter was critical, attended the signing of the Panama Canal Treaty), the apartheid government of South Africa, Zaire

(although Carter later changed course and supported Zaire, in response to alleged — albeit unproven — Cuba

n support of anti-Mobutu

rebels) and other traditional allies.

Carter continued the policy of Richard Nixon to normalize relations with the People's Republic of China. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski

Carter continued the policy of Richard Nixon to normalize relations with the People's Republic of China. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski

and China expert Michel Oksenberg

who was serving on the National Security Council, traveled to Beijing in early 1978, where they worked with Leonard Woodcock

, head of the liaison office there, to lay the groundwork for granting the People's Republic of China full diplomatic and trade relations. In the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations

dated January 1, 1979, the United States transferred diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. The U.S. reiterated the Shanghai Communiqué's acknowledgment of the Chinese position that there is only one China and that Taiwan is a part of China; Beijing acknowledged that the American people would continue to carry on commercial, cultural, and other unofficial contacts with the people of Taiwan. The U.S. unofficially recognized Taiwan through the Taiwan Relations Act

.

One of the most controversial moves of Carter's presidency was the final negotiation and signature of the Panama Canal Treaties in September 1977. Those treaties, which essentially would transfer control of the American-built Panama Canal to the nation of Panama

One of the most controversial moves of Carter's presidency was the final negotiation and signature of the Panama Canal Treaties in September 1977. Those treaties, which essentially would transfer control of the American-built Panama Canal to the nation of Panama

, were bitterly opposed by a majority of the American public and by the Republican Party. A common argument against the treaties was that the United States was transferring an American asset of great strategic value to an unstable and corrupt country led by an unelected but popularly supported General (Omar Torrijos

). Those that supported the Treaties argued that the Canal was built within Panamanian territory therefore, by controlling it, the United States was in fact occupying part of another country and this agreement was intended to turn back to Panama the sovereignty of its complete territory. After the signature of the Canal treaties, in June 1978, Carter visited Panama with his wife and twelve U.S. Senators, amid widespread student disturbances against the Torrijos administration. Carter then began urging the Torrijos regime to soften its policies and move Panama towards gradual republicanism

.

A key foreign policy issue Carter worked laboriously on was the SALT II Treaty, which reduced the number of nuclear arms produced and/or maintained by both the United States and the Soviet Union. SALT is the common name for the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks, negotiations conducted between the US and the USSR. The work of Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon brought about the SALT I treaty, which had itself reduced the number of nuclear arms produced, but Carter wished to further this reduction. It was Carter's main goal (as was stated in his Inaugural Address) that nuclear weapons completely disappear from the world.

A key foreign policy issue Carter worked laboriously on was the SALT II Treaty, which reduced the number of nuclear arms produced and/or maintained by both the United States and the Soviet Union. SALT is the common name for the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks, negotiations conducted between the US and the USSR. The work of Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon brought about the SALT I treaty, which had itself reduced the number of nuclear arms produced, but Carter wished to further this reduction. It was Carter's main goal (as was stated in his Inaugural Address) that nuclear weapons completely disappear from the world.

Carter and Leonid Brezhnev

, the leader of the Soviet Union, reached an agreement to this end in 1979 — the SALT II Treaty, despite opposition in Congress to ratifying it, as many thought it weakened U.S. defenses. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

late in 1979 however, Carter withdrew the treaty from consideration by Congress and the treaty was never ratified (though it was signed by both Carter and Brezhnev). Even so, both sides honored the commitments laid out in the negotiations.

in December 1979, and began promptly arming the Afghan insurgents. Vice-President Walter Mondale famously declared: "I cannot understand—it just baffles me—why the Soviets these last few years have behaved as they have. Maybe we have made some mistakes with them. Why did they have to build up all these arms? Why did they have to go into Afghanistan? Why can't they relax just a little bit about Eastern Europe? Why do they try every door to see if it is locked?" The Soviets, several times shortly before the invasion, had staged conversations with the Afghan leadership suggesting that they had no desire to intervene, even as the Politburo was—with much hesitation—considering such an intervention. Though some have argued that U.S. financial assistance to Afghan dissidents, including Islamists and other militants, prior to the invasion; along with a Soviet desire to protect the leftist Afghan government, helped convince the Soviets to intervene, the Soviets ironically brutally murdered the Afghan President and his son, replacing him with a puppet regime, immediately after the invasion for fear that the US had secretly been collaborating with him.

One of the CIA's longest and most expensive covert operations was the supplying of billions of dollars in arms to the Afghan mujahideen militants. The CIA provided assistance to the fundamentalist insurgents through the Pakistan

i secret services, Inter-Services Intelligence

(ISI), in a program called Operation Cyclone

.

According to the "Progressive South Asia Exchange Net," citing an article in , U.S. policy, unbeknownst even to the Mujahideen, was part of a larger strategy of aiming "to induce a Soviet military intervention." The article includes a brief interview with President Carter's National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski

, in which he is quoted as saying that the U.S. provided aid to the mujahideen prior to the Soviet invasion for the deliberate purpose of provoking one. Brzezinski himself has denied the accuracy of the interview. According to Brzezinski, an NSC working group

on Afghanistan wrote several reports on the deteriorating situation in 1979, but President Carter ignored them until the Soviet intervention destroyed his illusions. Brzezinski has stated that the U.S. provided communications equipment and limited financial aid to the mujahideen prior to the "formal" invasion, but only in response to the Soviet deployment of forces to Afghanistan and the 1978 coup, and with the intention of preventing further Soviet encroachment in the region. Two declassified documents signed by Carter shortly before the invasion do authorize the provision "unilaterally or through third countries as appropriate support to the Afghan insurgents either in the form of cash or non-military supplies" and the "worldwide" distribution of "non-attributable propaganda" to "expose" the leftist Afghan government as "despotic and subservient to the Soviet Union" and to "publicize the efforts of the Afghan insurgents to regain their country's sovereignty," but the records also show that the provision of arms to the rebels did not begin until 1980.

The Soviet military invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 significantly damaged the already tenuous relationship between Secretary of State Vance and Brzezinski. Vance felt that Brzezinski's linkage of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

to other Soviet activities and the MX, together with the growing domestic criticisms in the United States of the SALT II Accord, convinced Brezhnev to decide on military intervention in Afghanistan. Brzezinski, however, later recounted that he repeatedly advanced proposals on how to maintain Afghanistan's "independence" and deter a Soviet invasion but was frustrated by the Department of State's opposition.

According to Eric Alterman

of The Nation

, Cyrus Vance

's close aide Marshall Shulman "insists that the State Department worked hard to dissuade the Soviets from invading and would never have undertaken a program to encourage it" and President Carter has said it was definitely "not my intention" to inspire a Soviet invasion but to deter one.

Robert Gates

, in his book Out Of The Shadows, wrote that Pakistan had actually been pressuring the United States for arms to aid the rebels for years, but that the Carter administration refused in the hope of finding a diplomatic solution to avoid war. Brzezinski seemed to have been in favor of the provision of arms to the rebels, while Vance's State Department, seeking a peaceful settlement, publicly accused Brzezinski of seeking to "revive" the Cold War

.

The Soviet invasion and occupation killed up to 2 million Afghans. Brzezinski defended the arming of the rebels in response, saying that it "was quite important in hastening the end of the conflict," thereby saving the lives of thousands of Afghans, but "not in deciding the conflict, because actually the fact is that even though we helped the mujaheddin, they would have continued fighting without our help, because they were also getting a lot of money from the Persian Gulf and the Arab states, and they weren't going to quit. They didn't decide to fight because we urged them to. They're fighters, and they prefer to be independent. They just happen to have a curious complex: they don't like foreigners with guns in their country. And they were going to fight the Soviets. Giving them weapons was a very important forward step in defeating the Soviets, and that's all to the good as far as I'm concerned." When he was asked if he thought it was the right decision in retrospect (given the Taliban's subsequent rise to power), he said: "Which decision? For the Soviets to go in? The decision was the Soviets', and they went in. The Afghans would have resisted anyway, and they were resisting. I just told you: in my view, the Afghans would have prevailed in the end anyway, 'cause they had access to money, they had access to weapons, and they had the will to fight." The interviewer then asked: "So U.S. support for the mujaheddin only begins after the Russians invade, not before?" Brzezinski replied: "With arms? Absolutely afterwards. No question about it. Show me some documents to the contrary." Likewise; Charlie Wilson said: "The U.S. had nothing whatsoever to do with these people's decision to fight ... but we'll be damned by history if we let them fight with stones."

The United States secretly began sending limited financial aid to anti-Soviet, Afghan Islamist factions on July 3, 1979. In December 1979 the USSR invaded Afghanistan and installed a new regime that would be loyal to Moscow. At the time some believed the Soviets were attempting to expand their borders southward in order to gain a foothold in the region. The Soviet Union had long lacked a warm water port, and their movement south seemed to position them for further expansion toward Pakistan

in the East, and Iran

to the West. American politicians, Republicans and Democrats alike, feared the Soviets were positioning themselves for a takeover of Middle East

ern oil. Others believed that the Soviet Union was afraid Iran's Islamic Revolution and Afghanistan's Islamization would spread to the millions of Muslims in the USSR.

After the invasion, Carter announced what became known as the Carter Doctrine

: that the U.S. would not allow any other outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf

. He terminated the Soviet Wheat Deal in January 1980, which was intended to establish trade with USSR and lessen Cold War

tensions. The grain exports had been beneficial to people employed in agriculture, and the Carter embargo

marked the beginning of hardship for American farmers. That same year, Carter also made two of the most unpopular decisions of his entire Presidency: prohibiting American athletes from participating in the 1980 Summer Olympics

in Moscow, and reinstating registration for the draft

for young males.

Carter and Brzezinski started a $3–4 billion covert program of training insurgents in Pakistan and Afghanistan as a part of the efforts to foil the Soviets' apparent plans. On the surface as well, Carter's diplomatic policies towards Pakistan in particular changed drastically. The administration had cut off financial aid

to the country in early 1979 when religious fundamentalists, encouraged by the prevailing Islamist military dictatorship

over Pakistan, burnt down a U.S. Embassy

based there. The international stake in Pakistan, however, had greatly increased with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The President of Pakistan

, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

, was offered 400 million dollars to subsidize the anti-communist

Mujahideen

in Afghanistan by Carter. General Zia declined the offer as insufficient, famously declaring it to be "peanuts"; and the U.S. was forced to step up aid to Pakistan.

Reagan would later expand this program greatly to combat Cold War concerns presented by the Soviet Union

at the time. Critics of this policy blame Carter and Reagan for the resulting instability of post-Soviet Afghan governments, which led to the rise of Islamic theocracy

in the region.

The main conflict between human rights and U.S. interests came in Carter's dealings with the Shah of Iran

The main conflict between human rights and U.S. interests came in Carter's dealings with the Shah of Iran

. The Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had been a strong ally of the United States since World War II and was one of the "twin pillars" upon which U.S. strategic policy in the Middle East

was built (the other being Saudi Arabia). However, his rule was strongly autocratic

, was seen as kleptocratic

at home, and in 1953 he went along with the Eisenhower Administration in staging a coup

to remove the elected Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadegh.

On a 1978 state visit to Iran, Carter spoke out in favor of the Shah, calling him a leader of supreme wisdom, and a pillar of stability in the volatile Middle East.

When the Iranian Revolution

broke out in Iran and the Shah was overthrown, the U.S. did not intervene directly. The Shah went into permanent exile

in January 1979. Carter initially refused him entry to the United States, even on grounds of medical emergency.

Despite his initial refusal to admit the Shah into the United States, on October 22, 1979, Carter finally granted him entry and temporary asylum

for the duration of his cancer

treatment. The Shah left the U.S. for Panama

on December 15, 1979. In response to the Shah's entry into the U.S., Iranian militants seized

the American embassy in Tehran

in November, taking 52 Americans hostage. The Iranians demanded:

Though later that year the Shah left the U.S. and died in Egypt

in July 1980, the hostage crisis continued and dominated the last year of Carter's presidency. The subsequent responses to the crisis — from a "Rose Garden

strategy" of staying inside the White House, to the ill-prepared and unsuccessful attempt to rescue the hostages by military means (Operation Eagle Claw

) — were largely seen as contributing to Carter's defeat in the 1980 election.

After the hostages were taken, Carter issued, on November 14, 1979, Executive Order 12170 — Blocking Iranian Government property, which was used to freeze the bank accounts of the Iranian government in U.S. banks, totaling about $8 billion U.S. at the time. This was to be used as a bargaining chip for the release of the hostages.

In the days before President Ronald Reagan

took office, Algeria

n diplomat Abdulkarim Ghuraib opened negotiations between the U.S. and Iran. This resulted in the "Algiers Accords" one day before the end of Carter's Presidency on January 19, 1981, which entailed Iran's commitment to free the hostages immediately. Additionally, Executive Orders 12277 through 12285 were issued by Carter releasing all assets belonging to the Iranian government and all assets belonging to the Shah found within the United States and the guarantee that the hostages would have no legal claim against the Iranian government that would be heard in U.S. courts. Iran, however, also agreed to place $1 billion of the frozen assets in an escrow account and both Iran and the United States agreed to the creation of a tribunal to adjudicate claims by U.S. Nationals against Iran for compensation for property lost by them or contracts breached by Iran. The tribunal, known as the Iran – United States Claims Tribunal, has awarded over $2 billion dollars to U.S. claimaints and has been described as one of the most important arbitration bodies in the history of international law

. Although the release of the hostages was negotiated and secured under the Carter administration, the hostages were released on January 20, 1981, moments after Reagan was sworn in as President.

, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget in the Carter administration, resigned his position on September 21, 1977, amid allegations of improper banking activities prior to his becoming Director. Lance was one of Carter's closest friends, and served as state highway director when Carter was Governor of Georgia. Carter supported Lance in his bid to succeed Carter as governor, but Lance was defeated in the primary. Lance was subsequently tried on various bank-related charges, but was acquitted. The Lance affair was an embarrassment to Carter, coming just a few years after the Watergate scandal

.

Griffin Bell

appointed Paul J. Curran as a special counsel to investigate loans made to the peanut business owned by Carter by a bank controlled by Bert Lance

, a friend of the president and the director of the Office of Management and Budget. Unlike Archibald Cox

and Leon Jaworski

who were named as special prosecutor

s to investigate the Watergate scandal

, Curran's position as special counsel meant that he would not be able to file charges on his own, but would require the approval of Assistant Attorney General Philip Heymann. Carter became the first sitting president to testify under oath as part of an investigation of that president.

The investigation was concluded in October 1979, with Curran announcing that no evidence had been found to support allegations that funds loaned from the National Bank of Georgia had been diverted to Carter's 1976 presidential campaign.

era draft dodger

s, issued in his first full day in office (January 21, 1977), President Carter used his power in other cases. In general, he issued 566 pardons or commutations as President, granting 20% of all requests that came before him.

Most notable cases:

Carter's youngest child Amy

Carter's youngest child Amy

lived in the White House while her father served as president. She was the subject of much media attention during this period as young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy

.

Carter's brother Billy

Carter's brother Billy

generated a great deal of notoriety during Carter's presidency for his colorful and often outlandish public behavior. In 1977, Billy Carter endorsed Billy Beer

, capitalizing upon his colorful image as a beer-drinking, Southern boy that had developed in the press

during President Carter's campaign. Billy Carter's name was occasionally used as a gag answer for a Washington, D.C.

, trouble-maker on 1970s episodes of The Match Game. Billy Carter once urinated on an airport runway in full view of the press and dignitaries. In late 1978 and early 1979, Billy Carter visited Libya

with a contingent from Georgia three times. He eventually registered as a foreign agent of the Libyan government and received a $220,000 loan. This led to a Senate

hearing over alleged influence peddling

, which some in the press dubbed "Billygate". A Senate subcommittee was called To Investigate Activities of Individuals Representing Interests of Foreign Governments (Billy Carter-Libya Investigation).

On May 5, 1979, Carter was the target of Raymond Lee Harvey

, a mentally ill

transient

, who was found with a starter pistol awaiting the President's Cinco de Mayo

speech at the Civic Center Mall in Los Angeles, and claimed to be part of a four-man assassination attempt.

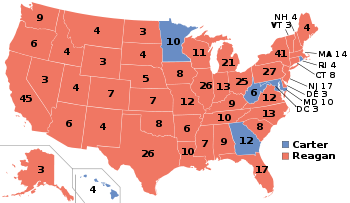

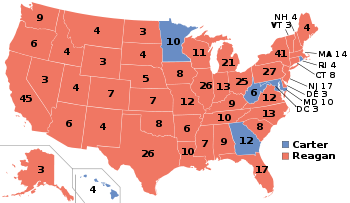

Carter lost the presidency to Ronald Reagan

Carter lost the presidency to Ronald Reagan

in the 1980 election. The popular vote went 50.7 percent, or 43.9 million popular votes, for Reagan and 41 percent, or 35.5 million, for Carter. Independent candidate John B. Anderson

won 6.6 percent, or 5.7 million votes. However, because Carter's support was not concentrated in any geographic region, Reagan won a landslide 91 percent of the electoral vote, leaving Carter with only six states and the District of Columbia. Reagan carried a total of 489 electoral votes compared to Carter's 49.

Carter's defeat marked the first time an elected president failed to secure a second term since Herbert Hoover in 1932. Furthermore, he was the first incumbent Democratic president to seek, but fail to achieve, re-election since Andrew Johnson (Grover Cleveland served two non-consecutive terms while Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson served one full term in addition to taking over after the deaths of Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy respectively and both Truman and Johnson did not seek re-election).

While Carter kept his promise (all 52 hostages returned home alive), he failed to secure the release of the hostages prior to the election. While Carter ultimately won their release, Iran did not release the hostages until minutes after Reagan took office. In recognition of the fact that Carter was responsible for bringing the hostages home, Reagan asked him to go to West Germany

to greet them upon their release.

During his campaign, Carter was mocked for an encounter with a swimming rabbit

while fishing on a farm pond on April 20, 1979.

Jimmy Carter

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

served as the thirty-ninth President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

from 1977 to 1981. His administration sought to make the government "competent and compassionate" but, in the midst of an economic crisis produced by rising energy prices

1970s energy crisis

The 1970s energy crisis was a period in which the major industrial countries of the world, particularly the United States, faced substantial shortages, both perceived and real, of petroleum...

and stagflation

Stagflation

In economics, stagflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high and the economic growth rate slows down and unemployment remains steadily high...

, met with difficulty in achieving its objectives. At the end of his administration, Carter had substantively reduced both unemployment and the deficit but had not been able to completely eliminate the recession. Carter created the United States Department of Education

United States Department of Education

The United States Department of Education, also referred to as ED or the ED for Education Department, is a Cabinet-level department of the United States government...

and United States Department of Energy

United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy is a Cabinet-level department of the United States government concerned with the United States' policies regarding energy and safety in handling nuclear material...

, established a national energy policy

Energy policy of the United States

The energy policy of the United States is determined by federal, state and local public entities in the United States, which address issues of energy production, distribution, and consumption, such as building codes and gas mileage standards...

and pursued civil service and social security reform. In foreign affairs, Carter initiated the Camp David Accords

Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were signed by Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on September 17, 1978, following thirteen days of secret negotiations at Camp David. The two framework agreements were signed at the White House, and were witnessed by United States...

, the Panama Canal Treaties and the second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty refers to two rounds of bilateral talks and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union—the Cold War superpowers—on the issue of armament control. There were two rounds of talks and agreements: SALT I and SALT...

(SALT II). Throughout his career, Carter strongly emphasized human rights. He returned the Panama Canal Zone

Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone was a unorganized U.S. territory located within the Republic of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending 5 miles on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón, which otherwise would have been partly within the limits of...

to Panama and he faced criticism at home for his decision, which was widely seen as yet another signal of U.S. weakness and of his own habit of backing down when faced with confrontation. The final year of his presidential tenure was marked by several major crises, including the 1979 takeover of the American embassy in Iran

Iran

Iran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

and holding of hostages

Iran hostage crisis

The Iran hostage crisis was a diplomatic crisis between Iran and the United States where 52 Americans were held hostage for 444 days from November 4, 1979 to January 20, 1981, after a group of Islamist students and militants took over the American Embassy in Tehran in support of the Iranian...

by Iranian students, an unsuccessful rescue attempt

Operation Eagle Claw

Operation Eagle Claw was an American military operation ordered by President Jimmy Carter to attempt to put an end to the Iran hostage crisis by rescuing 52 Americans held captive at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran on 24 April 1980...

of the hostages, serious fuel shortages

1979 energy crisis

The 1979 oil crisis in the United States occurred in the wake of the Iranian Revolution. Amid massive protests, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, fled his country in early 1979 and the Ayatollah Khomeini soon became the new leader of Iran. Protests severely disrupted the Iranian oil...

, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

Soviet war in Afghanistan

The Soviet war in Afghanistan was a nine-year conflict involving the Soviet Union, supporting the Marxist-Leninist government of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan against the Afghan Mujahideen and foreign "Arab–Afghan" volunteers...

.

Inauguration

In his inaugural address he said: "We have learned that more is not necessarily better, that even our great nation has its recognized limits, and that we can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems."Carter had campaigned on a promise to eliminate the trappings of the "Imperial Presidency

Imperial Presidency

Imperial Presidency is a term that became popular in the 1960s and that served as the title of a 1973 volume by historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. to describe the modern presidency of the United States...

," and he began taking action according to that promise on Inauguration Day, breaking with recent history and security protocols by walking up Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol is the meeting place of the United States Congress, the legislature of the federal government of the United States. Located in Washington, D.C., it sits atop Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall...

to the White House

White House

The White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

in his inaugural parade. His first steps in the White House went further in this direction: Carter reduced the size of the staff by one-third; canceled government-funded chauffeur

Chauffeur

A chauffeur is a person employed to drive a passenger motor vehicle, especially a luxury vehicle such as a large sedan or limousine.Originally such drivers were always personal servants of the vehicle owner, but now in many cases specialist chauffeur service companies, or individual drivers provide...

service for Cabinet

United States Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United States is composed of the most senior appointed officers of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States, which are generally the heads of the federal executive departments...

members, ordering them to drive their own cars; and put the USS Sequoia

USS Sequoia (presidential yacht)

USS Sequoia is a former United States presidential yacht used from Herbert Hoover to Jimmy Carter, who had it sold in 1977. The ship was decommissioned under Roosevelt and lost its "USS" status at that time, but by popular convention is still often used...

, the presidential yacht

Yacht

A yacht is a recreational boat or ship. The term originated from the Dutch Jacht meaning "hunt". It was originally defined as a light fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries...

up for sale.

Administration and cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President President of the United States The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.... |

Jimmy Carter | 1977–1981 |

| Vice President Vice President of the United States The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term... |

Walter Mondale Walter Mondale Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale is an American Democratic Party politician, who served as the 42nd Vice President of the United States , under President Jimmy Carter, and as a United States Senator for Minnesota... |

1977–1981 |

| State United States Secretary of State The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence... |

Cyrus Vance Cyrus Vance Cyrus Roberts Vance was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980... |

1977–1980 |

| Edmund Muskie Edmund Muskie Edmund Sixtus "Ed" Muskie was an American politician from Rumford, Maine. He served as Governor of Maine from 1955 to 1959, as a member of the United States Senate from 1959 to 1980, and as Secretary of State under Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981... |

1980–1981 | |

| Treasury United States Secretary of the Treasury The Secretary of the Treasury of the United States is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, which is concerned with financial and monetary matters, and, until 2003, also with some issues of national security and defense. This position in the Federal Government of the United... |

W. Michael Blumenthal W. Michael Blumenthal Werner Michael Blumenthal served as United States Secretary of the Treasury under President Jimmy Carter from 1977-1979.-Life and career:... |

1977–1979 |

| G. William Miller G. William Miller George William Miller served as the 65th United States Secretary of the Treasury under President Carter from August 6, 1979 to January 20, 1981... |

1979–1981 | |

| Defense United States Secretary of Defense The Secretary of Defense is the head and chief executive officer of the Department of Defense of the United States of America. This position corresponds to what is generally known as a Defense Minister in other countries... |

Harold Brown Harold Brown (Secretary of Defense) Harold Brown , American scientist, was U.S. Secretary of Defense from 1977 to 1981 in the cabinet of President Jimmy Carter. He had previously served in the Lyndon Johnson administration as Director of Defense Research and Engineering and Secretary of the Air Force.While Secretary of Defense, he... |

1977–1981 |

| Justice | Griffin Bell Griffin Bell Griffin Boyette Bell was an American lawyer and former Attorney General. He served as the nation's 72nd Attorney General during the Jimmy Carter administration... |

1977–1979 |

| Benjamin R. Civiletti | 1979–1981 | |

| Interior United States Secretary of the Interior The United States Secretary of the Interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior.The US Department of the Interior should not be confused with the concept of Ministries of the Interior as used in other countries... |

Cecil D. Andrus Cecil D. Andrus Cecil Dale Andrus was an American politician who served as Governor of Idaho from 1971 to 1977, and again from 1987 to 1995; and in Washington as United States Secretary of the Interior from 1977 to 1981, during the Carter administration... |

1977–1981 |

| Commerce United States Secretary of Commerce The United States Secretary of Commerce is the head of the United States Department of Commerce concerned with business and industry; the Department states its mission to be "to foster, promote, and develop the foreign and domestic commerce"... |

Juanita M. Kreps Juanita M. Kreps Juanita Morris Kreps was U.S. Secretary of Commerce from January 23, 1977 until October 31, 1979 under President Jimmy Carter and was the first woman to hold that position, and the fourth woman to hold any cabinet position.-Life and career:Kreps was born Clara Juanita Morris in Lynch, Kentucky,... |

1977–1979 |

| Philip M. Klutznick | 1979–1981 | |

| Labor United States Secretary of Labor The United States Secretary of Labor is the head of the Department of Labor who exercises control over the department and enforces and suggests laws involving unions, the workplace, and all other issues involving any form of business-person controversies.... |

Ray Marshall Ray Marshall Freddie Ray Marshall is the Professor Emeritus of the Audre and Bernard Rapoport Centennial Chair in Economics and Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin.... |

1977–1981 |

| Agriculture United States Secretary of Agriculture The United States Secretary of Agriculture is the head of the United States Department of Agriculture. The current secretary is Tom Vilsack, who was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on 20 January 2009. The position carries similar responsibilities to those of agriculture ministers in other... |

Robert Bergland Robert Bergland Robert Selmer Bergland is a United States politician. He grew up on a farm near Roseau, and studied agriculture at the University of Minnesota in a two year program... |

1977–1981 |

| HEW | Joseph A. Califano, Jr. Joseph A. Califano, Jr. Joseph Anthony Califano, Jr. is Founder and Chairman of The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, an independent non-profit research center affiliated with Columbia University in New York City... |

1977–1979 |

| HHS United States Secretary of Health and Human Services The United States Secretary of Health and Human Services is the head of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, concerned with health matters. The Secretary is a member of the President's Cabinet... |

Patricia R. Harris | 1979–1981 |

| Education United States Secretary of Education The United States Secretary of Education is the head of the Department of Education. The Secretary is a member of the President's Cabinet, and 16th in line of United States presidential line of succession... |

Shirley M. Hufstedler | 1979–1981 |

| HUD United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development The United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development is the head of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, a member of the President's Cabinet, and thirteenth in the Presidential line of succession. The post was created with the formation of the Department of Housing... |

Patricia R. Harris | 1977–1979 |

| Maurice "Moon" Landrieu Moon Landrieu Maurice Edwin "Moon" Landrieu is a Democratic politician from Louisiana who served as Mayor of New Orleans from 1970–1978. He also is a former judge... |

1979–1981 | |

| Transportation United States Secretary of Transportation The United States Secretary of Transportation is the head of the United States Department of Transportation, a member of the President's Cabinet, and fourteenth in the Presidential line of succession. The post was created with the formation of the Department of Transportation on October 15, 1966,... |

Brock Adams Brock Adams Brockman "Brock" Adams was an American politician and member of Congress. Adams was a Democrat from Washington and served as a U.S. Representative, Senator, and United States Secretary of Transportation before retiring in January 1993.Adams was born in Atlanta, Georgia, and attended the public... |

1977–1979 |

| Neil E. Goldschmidt | 1979–1981 | |

| Energy United States Secretary of Energy The United States Secretary of Energy is the head of the United States Department of Energy, a member of the President's Cabinet, and fifteenth in the presidential line of succession. The position was formed on October 1, 1977 with the creation of the Department of Energy when President Jimmy... |

James R. Schlesinger James R. Schlesinger Dr. James Rodney Schlesinger is an American politician. He is best known for serving as Secretary of Defense from 1973 to 1975 under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford... |

1977–1979 |

| Charles W. Duncan | 1979–1981 |

- White House Chief of StaffWhite House Chief of StaffThe White House Chief of Staff is the highest ranking member of the Executive Office of the President of the United States and a senior aide to the President.The current White House Chief of Staff is Bill Daley.-History:...

- Hamilton JordanHamilton JordanWilliam Hamilton McWhorter Jordan was Chief of Staff to President of the United States Jimmy Carter.-Early life:...

(1979–1980) - Jack H. WatsonJack Watson (Presidential adviser)Jack H. Watson Jr. former Chief Legal Strategist of Monsanto Company, served as Assistant to the President for Intergovernmental Affairs, Secretary to the Cabinet, and White House Chief of Staff during the Carter Administration....

(1980–1981)

- Hamilton Jordan

- Director of the Office of Management and Budget

- Bert LanceBert LanceThomas Bertram Lance is an American businessman, who was Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Jimmy Carter. He is known mainly for his resignation from President Jimmy Carter's administration due to scandal in 1977.- Early Life :Lance was born in Gainesville, Georgia...

(1977) - James T. McIntyreJames T. McIntyreJames T. McIntyre was a director of the United States' Office of Management and Budget from September 24, 1977 until January 20, 1981....

(1977–1981)

- Bert Lance

- United States Trade Representative

- Robert S. StraussRobert Schwarz StraussRobert Schwarz Strauss is a figure in American politics and diplomacy. A Texas political figure, Strauss’s political service dates back to future president Lyndon Johnson’s first congressional campaign in 1937. By the 1950s, he was associated in Texas politics with the conservative faction of...

(1977–1979) - Reubin Askew (1979–1981)

- Robert S. Strauss

- Administrator of the Environmental Protection AgencyAdministrator of the Environmental Protection AgencyThe Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency is the head of the United States federal government's Environmental Protection Agency, and is thus responsible for enforcing the nation's Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, as well as numerous other environmental statutes. The Administrator is...

- John Quarles, Jr. (1977, acting)

- Douglas M. CostleDouglas M. CostleDouglas Michael Costle was one of the architects of the United States Environmental Protection Agency , and he served President Jimmy Carter as EPA Administrator from 1977 to 1981.- Early life and education :...

(1977–1981)

- United States Ambassador to the United NationsUnited States Ambassador to the United NationsThe United States Ambassador to the United Nations is the leader of the U.S. delegation, the U.S. Mission to the United Nations. The position is more formally known as the "Permanent Representative of the United States of America to the United Nations, with the rank and status of Ambassador...

- Andrew YoungAndrew YoungAndrew Jackson Young is an American politician, diplomat, activist and pastor from Georgia. He has served as Mayor of Atlanta, a Congressman from the 5th district, and United States Ambassador to the United Nations...

(1977–1979) - Donald McHenryDonald McHenryDonald Franchot McHenry is a former American diplomat. He was the United States Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations from September 1979 until January 20, 1981.-Biography:...

(1979–1981)

- Andrew Young

Others:

- Stansfield TurnerStansfield TurnerStansfield M. Turner is a retired Admiral and former Director of Central Intelligence. He is currently a senior research scholar at the University of Maryland, College Park School of Public Policy....

(Director of Central IntelligenceDirector of Central IntelligenceThe Office of United States Director of Central Intelligence was the head of the United States Central Intelligence Agency, the principal intelligence advisor to the President and the National Security Council, and the coordinator of intelligence activities among and between the various United...

) - Zbigniew BrzezińskiZbigniew BrzezinskiZbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski is a Polish American political scientist, geostrategist, and statesman who served as United States National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981....

(National Security AdvisorNational Security Advisor (United States)The Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, commonly referred to as the National Security Advisor , serves as the chief advisor to the President of the United States on national security issues...

)

Judicial appointments

Although Carter had no opportunity to appoint any justices to the Supreme Court of the United StatesSupreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

, he appointed 56 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals

United States courts of appeals

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal court system...

, and 203 judges to the United States district courts. Carter also experienced a small number of judicial appointment controversies

Jimmy Carter judicial appointment controversies

During President Jimmy Carter's presidency, he nominated four people for four different federal appellate judgeships who were not processed by the Democratic-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee before Carter's presidency ended. None of the four nominees were renominated by Carter's successor,...

, as three of his nominees for different federal appellate judgeships

United States federal judge

In the United States, the title of federal judge usually means a judge appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the United States Senate in accordance with Article II of the United States Constitution....

were not processed by the Democratic-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee

United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary is a standing committee of the United States Senate, of the United States Congress. The Judiciary Committee, with 18 members, is charged with conducting hearings prior to the Senate votes on confirmation of federal judges nominated by the...

before Carter's presidency ended.

Domestic policies

Carter's reorganization efforts separated the Department of Health, Education and Welfare into the Department of EducationUnited States Department of Education

The United States Department of Education, also referred to as ED or the ED for Education Department, is a Cabinet-level department of the United States government...

and the Department of Health and Human Services

United States Department of Health and Human Services

The United States Department of Health and Human Services is a Cabinet department of the United States government with the goal of protecting the health of all Americans and providing essential human services. Its motto is "Improving the health, safety, and well-being of America"...

. He signed into law a major Civil Service Reform, the first in over 100 years.

Amnesty

Amnesty is a legislative or executive act by which a state restores those who may have been guilty of an offense against it to the positions of innocent people, without changing the laws defining the offense. It includes more than pardon, in as much as it obliterates all legal remembrance of the...

for Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

-era draft evaders.

Under Carter's watch, the Airline Deregulation Act

Airline Deregulation Act

The Airline Deregulation Act is a United States federal law signed into law on October 24, 1978. The main purpose of the act was to remove government control over fares, routes and market entry from commercial aviation...

of 1978 was passed, which phased out the Civil Aeronautics Board. He also enacted deregulation

Deregulation

Deregulation is the removal or simplification of government rules and regulations that constrain the operation of market forces.Deregulation is the removal or simplification of government rules and regulations that constrain the operation of market forces.Deregulation is the removal or...

in the trucking, rail, communications, and finance industries.