Anti-communism

Encyclopedia

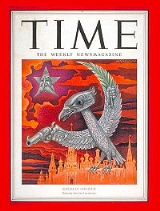

Anti-communism is opposition to communism

. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution

in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War

in 1947.

, which is a central idea in Marxism

. Anti-communists reject the Marxist belief that capitalism will be followed by socialism and communism, just as feudalism

was followed by capitalism. Anti-communists question the validity of the Marxist claim that the socialist state will "wither away" when it becomes unnecessary in a true communist society.

Anti-communists argue that the repression in the early years of the Bolshevik

regime, while not as extreme as that during Stalin's reign, was still severe by reasonable standards, citing examples such as Felix Dzerzhinsky's secret police, which eliminated numerous political opponents by extrajudicial executions, and the brutal crushing of the Kronstadt rebellion

and Tambov rebellion

. Some anti-communists refer to both Communism and fascism

as totalitarianism

, seeing similarity between the actions of communist and fascist governments. Robert Conquest

, a former Stalinist

and British Intelligence officer

, argued that Communism was responsible for tens of millions of deaths during the 20th century.

Opponents argue that Communist parties that have come to power have tended to be rigidly intolerant of political opposition. These opponents claim that most Communist countries have shown no signs of advancing from Marx's socialist stage of economy to an ideal communist stage. Rather, Communist governments have been accused of creating a new ruling class

(called the Nomenklatura

by Russians), with powers and privileges greater than those previously enjoyed by the upper classes in the pre-revolutionary regimes.

to form the Communist Third International, democratic socialists and social democrats have been in conflict with Communism, criticising it for its anti-democratic nature. Examples of left-wing critics of Communist states and parties are George Orwell

, Boris Souveraine, Bayard Rustin

, Irving Howe

and Max Shachtman

.

(spelled with a lower case c), all anarchists criticize authoritarian Communist parties and states. They argue that Marxist concepts such as dictatorship of the proletariat

and state ownership of the means of production

are anathema to anarchism. Some anarchists criticize communism from an individualist

or anarcho-capitalist point of view.

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin

debated with Karl Marx

in the First International, arguing that the Marxist state is another form of oppression. He loathed the idea of a vanguard party

ruling the masses from above. Anarchists initially participated in, and rejoiced over, the 1917 revolution

as an example of workers taking power for themselves. However, after the October revolution

, it became evident that the Bolsheviks and the anarchists had very different ideas. Anarchist Emma Goldman

, deported from the United States to Russia in 1919, was initially enthusiastic about the revolution, but was left sorely disappointed, and began to write her book My Disillusionment in Russia

. Anarchist Peter Kropotkin

, proffered trenchant criticism of the emergent Bolshevik bureaucracy in letters to Vladimir Lenin

, noting in 1920: "[a party dictatorship] is positively harmful for the building of a new socialist system. What is needed is local construction by local forces ... Russia has already become a Soviet Republic only in name." Many anarchists fought against Russian, Spanish and Greek Communists; many were killed by them, such as Lev Chernyi

, Camillo Berneri

and Constantinos Speras

. As well a lot of anarchists were massacred in concentration camps by Communists.

. Furthermore many capitalist theorists believe that communism interferes with the price mechanism that is only optimized in private competition. See economic calculation debate.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx lays out a 10-point plan advising the redistribution of land and production, and Ludwig von Mises

argues that the initial and ongoing forms of redistribution constitute direct coercion. Neither Marx's 10-point plan nor the rest of the manifesto say anything about who has the right to carry out the plan. Milton Friedman

argued that the absence of voluntary economic activity makes it too easy for repressive political leaders to grant themselves coercive powers. Friedman's view was also shared by Friedrich Hayek

and John Maynard Keynes

, both of whom believed that capitalism is vital for freedom to survive and thrive.

Many capitalist critics see a key error in communist economic theory, which predicts that in capitalist societies, the bourgeoisie will accumulate ever-increasing capital and wealth, while the lower classes become more dependent on the ruling class for survival, selling their labor power

for the most minimal of salaries, blaming the effect on capitalism. Anti-communists point to the overall rise in the average standard of living

in the non-communist West and claim that both the rich and poor have steadily gotten richer. Anti-communists argue that former Third World

countries that have successfully escaped poverty in recent decades have done so using capitalism, most notably India

and China

. Anti-communists cite the Mengistu regime in Ethiopia

as an example how a Communist regime in the Third World failed to achieve development or economic growth.

argue that wealth (or any other human value) is the creation of individual minds, that human nature requires motivation by personal incentive, and therefore, that only political and economic freedom are consistent with human prosperity. This is demonstrated, they believe, by the comparative prosperity of free market

and socialist

economies. Objectivist Ayn Rand

writes that communist leaders typically claim to work for the common good, but many or all of them have been corrupt and totalitarian.

Edward O. Wilson said "Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species," meaning that while ant

s and other social insects appear to live in communist-like societies, they only do so because they are forced to because they lack reproductive independence. Worker ants are sterile, and individual ants cannot reproduce without a queen, so ants are forced to live in centralised societies. Humans possess reproductive independence, so they can give birth to offspring without the need of a "queen". According to Wilson, humans enjoy their maximum level of Darwinian fitness only when they look after themselves and their families, while finding innovative ways to use the societies they live in for their own benefit.

turned from a Communist into a social democrat. Milovan Đilas, was a former Yugoslav

Communist official, who became a prominent dissident

and critic of Communism. Leszek Kołakowski was a Polish Communist who became a famous anti-communist. He was best known for his critical analyses of Marxist

thought, especially his acclaimed three-volume history, Main Currents of Marxism, which is "considered by some to be one of the most important books on political theory of the 20th century." The God That Failed

is a 1949 book which collects together six essay

s with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-Communists

, who were writers and journalists. The common theme of the essays is the authors' disillusionment with and abandonment of Communism. The promotional byline

to the book is "Six famous men tell how they changed their minds about Communism." Another notable anti-communist was Whittaker Chambers

, a former Soviet Union

spy who testified against his fellow spies before the House Un-American Activities Committee

.

Other anti-communists who were once Marxists include the writers Max Eastman

, John Dos Passos

, James Burnham

, Morrie Ryskind

, Frank Meyer

, Will Herberg

, Sidney Hook

, Louis Fischer

, André Gide

, Arthur Koestler

, Ignazio Silone

, Stephen Spender

, Peter Hitchens

and Richard Wright

. Anti-communists who were once socialists

, modern liberals or social democrats

include: John Chamberlain

, Friedrich Hayek

, Raymond Moley

, Norman Podhoretz

and Irving Kristol

.

, took power with the blessing of Italy's king after years of leftist unrest led many conservatives

to fear that a communist revolution was inevitable. Historians Ian Kershaw

and Joachim Fest

argue that in post-World War I

Germany, the Nazis were one of many nationalist and fascistic political parties contending for the leadership of Germany’s anti-communist

movement, and of the German state. The Nazis claimed that communism was dangerous to the well-being of nations because of its intention to dissolve private property

, its support of class conflict

, its aggression against the middle class, its hostility to small businessmen, and its atheism

. Nazism rejected class conflict-based socialism and economic egalitarianism

, favouring instead a stratified

economy with classes based on merit and talent, retaining private property

, and the creation of national solidarity that transcends class distinction.

In Europe, numerous aristocrats

, conservative intellectuals, capitalists and industrialists lent their support to fascist movements. During the late 1930s and the 1940s, several other anti-communist regimes and groups supported Nazism: the Falange

in Spain

; the Vichy regime

and the Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism

(Wehrmacht

Infantry Regiment 638) in France; the Cliveden set

, Lord Halifax, and associates of Neville Chamberlain

in Britain.; and, in South America, movements such as Brazilian Integralism

.

Anti-communism remained a theme in far right politics after the war. For example, in the US, Frank L. Britton, editor of The American Nationalist published a book, Behind Communism, in 1952 which disseminated the myth that Communism was a Jewish conspiracy originating in Palestine

.

ese Buddhist monk

and anti-communist dissident. In 1977, Huyền Quang wrote a letter to Prime Minister

Phạm Văn Đồng detailing counts of oppression by the Communist regime. For this, he and five other senior monks were arrested and detained. In 1982, Huyền Quang was arrested and subsequently put into permanent house arrest for opposition to government policy after publicly denouncing the establishment of the state-controlled Vietnam Buddhist Church. Thích Quảng Độ is a Vietnamese Buddhist monk and anti-communist dissident. In January 2008, the Europe-based magazine A Different View

chose Ven. Thích Quảng Độ as one of the 15 Champions of World Democracy.

states: "The Catholic Church has rejected the totalitarian and atheistic

ideologies associated in modern times with 'communism' or 'socialism.' … Regulating the economy solely by centralized planning perverts the basis of social bonds … [Still,] reasonable regulation of the marketplace and economic initiatives, in keeping with a just hierarchy of values and a view to the common good, is to be commended."

Pope John Paul II

was a harsh critic of communism, and other popes shared this view as well, for example Pope Pius IX

issued a Papal

encyclical

, entitled Quanta Cura

, in which he called "Communism and Socialism" the most fatal error. During the Spanish Civil War

, the Catholic Church opposed the left-leaning Republican forces due to their ties to communism and atrocities against Catholicism in Spain, and in many churches and schools prayers were made for the victory of Franco

.

Lúcia Santos

, a visionary of the Marian apparition at Fátima, Portugal

was known for her anti-communist beliefs, as well as the message of Fatima in general.

From 1945 onward Australian Labor Party

leadership accepted the assistance of an anti-Communist Roman Catholic movement, led by B.A. Santamaria to oppose communist subversion of Australian Trade Unions (Catholics being an important traditional support base). To oppose communist infiltration of unions Industrial Groups

were formed to regain control of them. The groups were active from 1945 to 1954, with the knowledge support of ALP leadership until after Labor's loss of the 1954 election, when federal leader Dr H.V. Evatt, in the context of his response to the Petrov affair

, blamed “subversive” activities of the "Groupers", for the defeat. After bitter public dispute many Groupers (including most members of the NSW and Victorian state executives and most Victorian Labor branches) were expelled from the ALP and formed the Democratic Labor Party (historical)

. In an attempt to force the ALP reform and remove communist influence, with a view to then rejoining the “purged” ALP, the DLP preferenced (see Australian electoral system

) the Liberal Party of Australia

, enabling them remain in power for over two decades. Their negative strategy failed, and after the Whitlam Labor Government during the 1970s it, the majority of the DLP decided to wind up the party in 1978, although a small Federal and State party continued based in Victoria (see Democratic Labor Party

) with state parties reformed in NSW and Qld in 2008.

After the sovietic occupation of Hungary During the final Stages of the Second World War, many clerigs were arrested. The case of the Archbishop

József Mindszenty of Esztergom

, head of the Catholic Church in Hungary was the most known. He was accused of treason to the communist ideas and was sent to trials and tortured during several years between 1949 and 1956. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 against the communism he was set free and after the failure of the movement he was forced to move to the United States' ambassy on Budapest

. There he lived until 1971 when the Vatican and the communist government of Hungary pacted his way out to Austria

. In the following years Mindszenty travelled for all over the world visiting the Hungarian colonies on Canada

, United States, Germany, Austria

, South Africa

and Venezuela

. He led a high critical campaign against the communist regime denouncing the atrocities committed by them against him and the Hungarian people. The communist government accused him and demanded that the Vatican remove him the title of archbishop of Esztergom and forbid him to keep giving public speechs about the communist torture ways and freedom privations. After a lot of polithical interventions, the Vatican was forced to accomplish what the sovietic regime demanded. However Mindszenty kept travelling all over the world being a real symbol of unity, cultural preservation, and hope for the Hungarian people, no matter their religion (Lutherans, Calvinists, Catholics, etc.).

headquarters, Zhongnanhai

, in a silent protest following an incident in Tianjin

. Two months later the Chinese government banned the practice through a crackdown and began a large propaganda campaign. Since 1999, Falun Gong practitioners in China have been reportedly subject to torture, illegal imprisonment, beatings, forced labor, organ harvesting

, and psychiatric abuses. Falun Gong has responded with their own media campaign, and have emerged as a notable voice of dissent against the Communist Party of China, by founding organizations such as the Epoch Times, NTDTV and the Shen Yun Performing Arts

to publicize their cause.

in Afghanistan, 1978. Before this, traditional Muslim clerics railed against Communist influences in Muslim societies, but any action beyond the sermons was rare. After the declaration in Kabul of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

, a Civil War began that spiralled into the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union. This event elevated the ideology of Islamism

, which was rooted in Afghanistan's anti-Communist struggle, into a regional influence throughout South West Asia.

, a democratic socialist

, wrote two of the most widely read and influential anti-totalitarian novels: Nineteen Eighty-Four

and Animal Farm

, both of which featured allusions to the Soviet Union

under Joseph Stalin

.

Also on the left, Arthur Koestler

— a former member of the Communist Party — explored the ethics of revolution from an anti-communist perspective in a variety of works. His trilogy of early novels testified to Koestler's growing conviction that utopian ends do not justify the means often used by revolutionary governments. These novels are: The Gladiators (which explores the slave uprising led by Spartacus

in the Roman Empire as an allegory

for the Russian Revolution), Darkness at Noon

(based on the Moscow Trials

, this was a very widely read novel that made Koestler one of the most prominent anti-communist intellectuals of the period), and Arrival and Departure

.

Whittacker Chambers — an American ex-communist who became infamous for his cooperation with the House Un-American Activities Committee

(HUAC), where he implicated Alger Hiss

— published an influential anti-communist memoir, Witness, in 1952.

Boris Pasternak

, a Russian writer, rose to international fame after his anti-communist novel Doctor Zhivago

was smuggled out of the Soviet Union (where it was banned) and published in the West

in 1957. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature, much to the chagrin of the Soviet authorities.

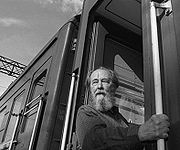

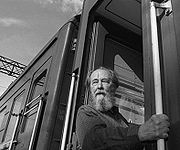

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was a Russian

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was a Russian

novelist, dramatist and historian

. Through his writings, — particularly The Gulag Archipelago

and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

, his two best-known works — he made the world aware of the Gulag

, the Soviet Union's forced labor camp system. For these efforts, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature

in 1970, and was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974.

Herta Müller

is a Romania

n-born German

novelist, poet and essayist noted for her works depicting the harsh conditions of life in Communist Romania

under the repressive Nicolae Ceauşescu

regime, the history of the Germans in the Banat

(and more broadly, Transylvania

), and the persecution of Romanian ethnic Germans

by Stalinist

Soviet occupying forces in Romania

and the Soviet-imposed Communist regime of Romania. Müller has been an internationally-known author since the early 1990s, and her works have been translated into more than 20 languages. She has received over 20 awards, including the 1994 Kleist Prize

, the 1995 Aristeion Prize

, the 1998 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

, the 2009 Franz Werfel Human Rights Award

and the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature

.

Ayn Rand

was a Russian-American 20th century writer who was an enthusiastic supporter of laissez-faire

capitalism

. She wrote We the Living

about the effects of Communism in Russia.

(also translated The Tenderfoot and the Tart) is a play in four acts by Russian

author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

. It is set over the course of about one week in 1945 in a Stalin-era Soviet prison camp. As in many of Solzhenitsyn's works, the author paints a vivid and honest picture of the suffering prisoners and their incompetent but powerful wardens. Most of the prisoners depicted in the play are serving 10 year sentences for violations of Soviet Penal Code Article 58. In this play, the author first explores the analogy of the camp system to a separate nation within the Soviet Union

, an analogy which would dominate his later work, most clearly in The Gulag Archipelago

.

was a key form of dissident activity across the Soviet-bloc; individuals reproduced censored publications by hand and passed the documents from reader to reader, thus building a foundation for the successful resistance of the 1980s. This grassroots

practice to evade officially imposed censorship

was fraught with danger as harsh punishments were meted out to people caught possessing or copying censored

materials. Vladimir Bukovsky

defined it as follows: "I myself create it, edit it, censor it, publish it, distribute it, and get imprisoned for it."

During the Cold War, Western countries invested heavily in powerful transmitters which enabled broadcasters to be heard in the Eastern Bloc, despite attempts by authorities to jam

such signals. In 1947, VOA started broadcasting in Russian

with the intent to counter Soviet propaganda directed against American leaders and policies. These included Radio Free Europe

(RFE)), RIAS (Berlin)

the Voice of America

(VOA), Deutsche Welle

, Radio France International and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). The Soviet Union responded by attempting aggressive, electronic jamming

of VOA (and some other Western) broadcasts on 1949. The BBC World Service

similarly broadcast language-specific programming to countries behind the Iron Curtain

.

In the People's Republic of China, people have to bypass the Chinese Internet censorship

and other forms of censorship.

(PACE), issued on January 25, 2006 during its winter session, "strongly condemns crimes of totalitarian communist regimes".

The European Parliament has proposed making 23 August a Europe-wide day of remembrance for 20th-century Nazi and communist crimes.

, and other anti-communist movements in addition to the winning communist group. Stemming was the unsuccessful Western-backed campaign of toppling the communist government through the infiltration of dissidents into the country that was made possible from the unification of the four anti-communist groups Legaliteti, Balli Kombëtar

, Independents' Block, and the Kosovars' Group.

In 1946, an armed uprising took place in Postribë

whereby more than a dozen participants were killed and others imprisoned. In 1973, a number of prisoners at the Spac

concentration camp staged a rebellion where the non-communist flag was raised. In 1984, a similar rebellion took place at the prison of Qafë Bar.

Albania has enacted the Law on Communist Genocide with the purpose of expediting the prosecution of the violations of the basic human rights

and freedoms by the former communist governments of the Socialist People's Republic of Albania. The law has also been referred to in English as the "Genocide Law" and the "Law on Communist Genocide".

The Velvet Revolution

or Gentle Revolution was a non-violent

revolution

in Czechoslovakia

that saw the overthrow of the Communist government. It is seen as one of the most important of the Revolutions of 1989

.

On November 17, 1989, a Friday, riot police suppressed a peaceful student demonstration

in Prague

. That event sparked a series of popular demonstrations from November 19 to late December. By November 20 the number of peaceful protesters assembled in Prague had swollen from 200,000 the previous day to an estimated half-million. A two-hour general strike

, involving all citizens of Czechoslovakia, was held on November 27. In June 1990 Czechoslovakia held its first democratic

election

s since 1946.

Memorials for the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989

are held every year in Hong Kong. Tens of thousands people have attended the candlelight vigil.

, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. The revolt began as a student demonstration which attracted thousands as it marched through central Budapest

to the Parliament building

. A student delegation entering the radio building

in an attempt to broadcast its demands

was detained. When the delegation's release was demanded by the demonstrators outside, they were fired upon by the State Security Police

(ÁVH) from within the building. The news spread quickly and disorder and violence erupted throughout the capital. The revolt spread quickly across Hungary

, and the government fell. After announcing a willingness to negotiate a withdrawal of Soviet forces, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

changed its mind and moved to crush the revolution.

n government and allied militia

.

, in which over 20,000 people accused of being Communists were purged from their places of employment.

is a loosely organized anti-communist movement in the People's Republic of China

. The movement began during Beijing Spring

in 1978 and played an important role in the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989

. The 1959 Tibetan Rebellion had some anti-communist leanings. In the 1990s, the movement underwent a decline both within China

and overseas, and is currently fragmented and not considered by most analysts to be a serious threat to power to the Communist Party's rule.

Charter 08

is a manifesto

signed by over 303 Chinese intellectual

s and human rights

activists to promote political reform and democratization

in the People's Republic of China

.

As a document of Chinese origin, it is unusual in calling for greater freedom of expression

and for free election

s. It was published on 10 December 2008, the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and its name is a reference to Charter 77

, issued by dissident

s in Czechoslovakia.

Since its release, more than 8,100 people inside and outside of China have signed the charter.

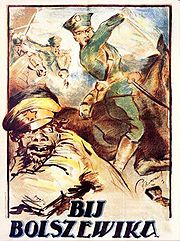

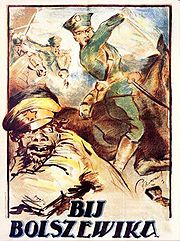

Lenin

saw Poland as the bridge which the Red Army

would have to cross in order to assist the other communist movements

and help bring about other European revolutions. Poland was the first country which successfully stopped a communist military advance. Between February 1919 and March 1921, Poland's successful defence of its independence was known as the Polish–Soviet War. According to American sociologist Alexander Gella, "the Polish victory had gained twenty years of independence not only for Poland, but at least for an entire central part of Europe."

After the German and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, the first Polish uprising during World War II

After the German and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, the first Polish uprising during World War II

was against the Soviets. The Czortków Uprising

occurred during January 21–22, 1940, in the Soviet-occupied Podolia

. Teenagers from local high schools stormed the local Red Army

barracks and a prison, in order to release Polish soldiers who had been imprisoned there.

In the latter years of the war, there were increasing conflicts between Polish and Soviet partisans

, and some groups continued to oppose the Soviets long after the war. Between 1944 and 1946, soldiers of the anti-communist armed groups, known as the cursed soldiers

, made a series of attacks on communist prisons immediately following the end of World War II

in Poland

. The last of the cursed soldiers

, members of the militant anti-communist resistance in Poland

, was Józef Franczak

, who was killed with a pistol in his hand by ZOMO

in 1963.

Poznań 1956 protests

were massive anti-communist protests in the People's Republic of Poland

. Protesters were repressed by the regime.

The Polish 1970 protests

were anti-Comintern protests which occurred in northern Poland

in December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase in the prices of food and other everyday items. As a result of the riots, brutally put down by the Polish People's Army and the Citizen's Militia

, at least 42 people were killed and more than 1,000 were wounded.

Solidarity was an anti-communist trade union in a Warsaw Pact

country. In the 1980s, it constituted a broad anti-communist movement. The government attempted to destroy the union during the period of martial law in the early 1980s

, and several years of repression, however, in the end, it had to start negotiating with the union. The Round Table Talks

between the government and the Solidarity-led opposition led to semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August, a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed, and in December 1990, Wałęsa was elected President of Poland. Since then, it has become a more traditional trade union.

lasted between 1948 and the early 1960s. Armed resistance was the first and most structured form of resistance against the communist regime. It was not until the overthrow of Nicolae Ceauşescu

in late 1989 that details about what was called “anti-communist armed resistance” were made public. It was only then that the public learned about the numerous small groups of "haiducs" who had taken refuge in the Carpathian Mountains

, where some resisted for ten years against the troops of the Securitate

. The last “haiduc” was killed in the mountains of Banat

in 1962. The Romanian resistance was one of the longest lasting armed movement in the former Soviet bloc

.

The Romanian Revolution of 1989

was a week-long series of increasingly violent riots and fighting in late December 1989 that overthrew the Government of Nicolae Ceauşescu

. After a trial, Ceauşescu and his wife Elena

were executed. Romania

was the only Eastern Bloc

country to overthrow its government violently or to execute its leaders.

emerged on April 7, 2009, in major cities of Moldova

after the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) had allegedly rigged elections.

The anti-communists organized themselves using an online social network service

, Twitter

, hence its moniker used by the media, the Twitter Revolution or Grape revolution.

anti-Communist partisans fought during World War II, on the Yugoslav Front: nationalist and royalist paramilitary Chetniks

conducted a guerilla war against much the stronger Communist-led Yugoslav Partisans, the latter heavily sponsored by the Allied powers

, in the last two years of war.

s of South America

implemented Operation Condor

, a campaign of political repression

involving assassinations and other intelligence operations. The campaign was aimed at eradicating alleged communist and socialist influences in their respective countries, and control opposition against the government, which resulted in a large number of deaths. Participatory governments include Argentina

, Bolivia

, Brazil

, Chile

, Paraguay

and Uruguay

, with limited support from the United States

.

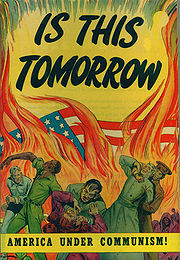

The first major manifestation of anti-communism in the United States occurred in 1919 and 1920, during the First Red Scare

The first major manifestation of anti-communism in the United States occurred in 1919 and 1920, during the First Red Scare

, led by Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer

. During the Red Scare, the Lusk Committee investigated those suspected of sedition, and many laws were passed in the US that sanctioned the firings of Communists. First came the Hatch Act of 1939

which was sponsored by Carl Hatch

of New Mexico

. This law attempted to drive Communism out of public work places. The Hatch Act outlawed the hiring of federal workers who advocated the "overthrow of our Constitutional form of government". This phrase was specifically directed at the Communist Party. Later in the spring of 1941 another anti-communist law, Public Law 135, was passed. This law sanctioned the investigation of any federal worker suspected of being communist and the firing of any communist worker.

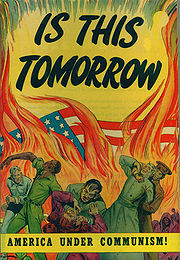

Following World War II

and the rise of the Soviet Union, many anti-communists in the United States feared that Communism would triumph throughout the entire world and eventually be a direct threat to the US government. This fear led to the domino theory

, which stated that a Communist takeover in any nation could not be tolerated because it would lead to a chain reaction that would result in worldwide Communism. There were fears that powerful Communist states such as the Soviet Union

and the People's Republic of China

were using their power to forcibly assimilate other countries into Communist rule. The Soviet Union's expansion into central Europe

after World War II was seen as evidence of this. The US policy of halting further Communist expansion came to be known as containment

. This period, up to 1957, is known as the Second Red Scare.

The deepening of the Cold War

in the 1950s saw a dramatic increase in anti-communism in the United States, including the anti-communist campaign known as McCarthyism

. Thousands of Americans, such as the filmmaker Charlie Chaplin

, were accused of being Communists or sympathizers, and many became the subject of aggressive investigations by government committees such as the House Committee on Un-American Activities. As a result of sometimes vastly exaggerated accusations, many of the accused lost their jobs and became blacklisted, although most of these verdicts were later overturned. This was also the period of the McCarran Internal Security Act and the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

trial. After the collapse of the Soviet Union many records were made public that in fact verified that many of those thought to be falsely accused for political purposes were in fact Communist spies or sympathizers (see Venona Project

).

During the 1980s, the Ronald Reagan

administration pursued an aggressive policy against the Soviet Union and its allies by building up weapons programs, including the Strategic Defense Initiative

. The Reagan Doctrine

was implemented to reduce the influence of the Soviet Union worldwide by providing aid to anti-Soviet resistance movements, including the Contras

in Nicaragua

and the Mujahideen

s in Afghanistan

. The accidental downing of Korean Air Lines Flight 007 near Moneron Island

by the Soviets on Sept. 1, 1983 contributed to the anti-communism propaganda of the 1980s. KAL 007 had been carrying 269 people, including a sitting U.S. Congressman, Larry McDonald

.

The US government usually argued its anti-communist policies by citing the human rights record of communist states, most notably the Soviet Union during the Joseph Stalin

The US government usually argued its anti-communist policies by citing the human rights record of communist states, most notably the Soviet Union during the Joseph Stalin

era, Maoist

China, North Korea

, and the Pol Pot

-led Khmer Rouge

government and the pro-Hanoi

People's Republic of Kampuchea

in Cambodia

. Those states killed millions of their own people and continued to suppress civil liberties of the surviving population. During the 1980s, the Kirkpatrick Doctrine

was particularly influential in American politics; it advocated US support of anti-communist governments around the world, including authoritarian regimes.

Anti-communism became significantly muted after the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc

Communist regimes in Europe between 1989 and 1991; the fear of a worldwide Communist takeover was no longer a serious concern. Remnants of anti-communism remain, however, in US foreign policy toward Cuba

and North Korea

. In the case of Cuba, the US continues to maintain economic sanctions

against the country. Tensions with North Korea have heightened as the result of reports that it is stockpiling nuclear weapons, and the assertion that it is willing to sell its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile

technology to any group willing to pay a high enough price. Much of the US foreign policy establishment does not regard the People's Republic of China

as communist in any meaningful sense. Nevertheless, there is some hostility toward the Chinese government, particularly among conservative Congressional Republicans. For example, national security issues were raised during Chinese state-owned CNOOC Ltd.'s takeover bid for Unocal, an American energy firm.

, anti-communist movements, including those from pro-democracy and pro-human rights groups, had largely been limited before the advent of the Internet

. This was due to repression of dissidents as well as the Vietnamese government's efforts in censorship and propaganda regarding foreign and domestic policies, including examination of personal mails (especially those sent from overseas), and a heavy censorship of foreign media broadcasts.

Prior to the arrival of the Internet, much of the global anti-communist activities directed towards Vietnam were religious in nature. Clerical North American and European organizations voiced concerns about religious oppressions. Of particular robustness were the organizations of Monsignor Tran Van Hoai, the first Director of the Vatican's Center of Pastoral Apostolate for Overseas Vietnamese.

In recent years, there have been many Vietnamese bloggers who, with the aid of the World Wide Web

, have disseminated information critical of Ho Chi Minh

and the Vietnamese government's relations with the People's Republic of China

, the most controversial of which are deals struck between the two communist countries' leaders, such as territorial claims of islands in the South China Sea

. These have sparked intense nationalism and led to much outrage felt even on the part of many Vietnamese themselves. The culmination of the sentiments can be seen in many recent protests held in both former North Vietnam

's capital Hanoi

and former South Vietnam

's capital Saigon.

Frequent arrests of some democracy advocates by the government have also led to activism among many Vietnamese who demand an release of all political dissidents as well as greater clarity in their trials. Recently, there have also been protests against the government blocking access to free networking

and blogging services such as Facebook

, Wordpress

, as well as calls for a unified effort in boycotting government sanctioned blogging services like the so-called "Yahoo! Việt Nam 360plus".

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

in 1947.

Objections to communist theory

Most anti-communists reject the concept of historical materialismHistorical materialism

Historical materialism is a methodological approach to the study of society, economics, and history, first articulated by Karl Marx as "the materialist conception of history". Historical materialism looks for the causes of developments and changes in human society in the means by which humans...

, which is a central idea in Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

. Anti-communists reject the Marxist belief that capitalism will be followed by socialism and communism, just as feudalism

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

was followed by capitalism. Anti-communists question the validity of the Marxist claim that the socialist state will "wither away" when it becomes unnecessary in a true communist society.

Anti-communists argue that the repression in the early years of the Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

regime, while not as extreme as that during Stalin's reign, was still severe by reasonable standards, citing examples such as Felix Dzerzhinsky's secret police, which eliminated numerous political opponents by extrajudicial executions, and the brutal crushing of the Kronstadt rebellion

Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion was one of many major unsuccessful left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks in the aftermath of the Russian Civil War...

and Tambov rebellion

Tambov Rebellion

The Tambov Rebellion which occurred between 1920 and 1921 was one of the largest and best-organized peasant rebellions challenging the Bolshevik regime during the Russian Civil War. The uprising took place in the territories of the modern Tambov Oblast and part of the Voronezh Oblast, less than...

. Some anti-communists refer to both Communism and fascism

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

as totalitarianism

Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system where the state recognizes no limits to its authority and strives to regulate every aspect of public and private life wherever feasible...

, seeing similarity between the actions of communist and fascist governments. Robert Conquest

Robert Conquest

George Robert Ackworth Conquest CMG is a British historian who became a well-known writer and researcher on the Soviet Union with the publication in 1968 of The Great Terror, an account of Stalin's purges of the 1930s...

, a former Stalinist

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

and British Intelligence officer

SPY

SPY is a three-letter acronym that may refer to:* SPY , ticker symbol for Standard & Poor's Depositary Receipts* SPY , a satirical monthly, trademarked all-caps* SPY , airport code for San Pédro, Côte d'Ivoire...

, argued that Communism was responsible for tens of millions of deaths during the 20th century.

Opponents argue that Communist parties that have come to power have tended to be rigidly intolerant of political opposition. These opponents claim that most Communist countries have shown no signs of advancing from Marx's socialist stage of economy to an ideal communist stage. Rather, Communist governments have been accused of creating a new ruling class

Ruling class

The term ruling class refers to the social class of a given society that decides upon and sets that society's political policy - assuming there is one such particular class in the given society....

(called the Nomenklatura

Nomenklatura

The nomenklatura were a category of people within the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries who held various key administrative positions in all spheres of those countries' activity: government, industry, agriculture, education, etc., whose positions were granted only with approval by the...

by Russians), with powers and privileges greater than those previously enjoyed by the upper classes in the pre-revolutionary regimes.

Left-wing anti-communism

Since the split of the Communist Parties from the socialist Second InternationalSecond International

The Second International , the original Socialist International, was an organization of socialist and labour parties formed in Paris on July 14, 1889. At the Paris meeting delegations from 20 countries participated...

to form the Communist Third International, democratic socialists and social democrats have been in conflict with Communism, criticising it for its anti-democratic nature. Examples of left-wing critics of Communist states and parties are George Orwell

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair , better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English author and journalist...

, Boris Souveraine, Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was an American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, pacifism and non-violence, and gay rights.In the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation , Rustin practiced nonviolence...

, Irving Howe

Irving Howe

Irving Howe was an American literary and social critic and a prominent figure of the Democratic Socialists of America.-Life and career:...

and Max Shachtman

Max Shachtman

Max Shachtman was an American Marxist theorist. He evolved from being an associate of Leon Trotsky to a social democrat and mentor of senior assistants to AFL-CIO President George Meany.-Beginnings:...

.

Anarchists

Although many anarchists describe themselves as communistsAnarchist communism

Anarchist communism is a theory of anarchism which advocates the abolition of the state, markets, money, private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership of the means of production, direct democracy and a horizontal network of voluntary associations and workers' councils with...

(spelled with a lower case c), all anarchists criticize authoritarian Communist parties and states. They argue that Marxist concepts such as dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

and state ownership of the means of production

Means of production

Means of production refers to physical, non-human inputs used in production—the factories, machines, and tools used to produce wealth — along with both infrastructural capital and natural capital. This includes the classical factors of production minus financial capital and minus human capital...

are anathema to anarchism. Some anarchists criticize communism from an individualist

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that stresses "the moral worth of the individual". Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance while opposing most external interference upon one's own...

or anarcho-capitalist point of view.

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a well-known Russian revolutionary and theorist of collectivist anarchism. He has also often been called the father of anarchist theory in general. Bakunin grew up near Moscow, where he moved to study philosophy and began to read the French Encyclopedists,...

debated with Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

in the First International, arguing that the Marxist state is another form of oppression. He loathed the idea of a vanguard party

Vanguard party

A vanguard party is a political party at the forefront of a mass action, movement, or revolution. The idea of a vanguard party has its origins in the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels...

ruling the masses from above. Anarchists initially participated in, and rejoiced over, the 1917 revolution

February Revolution

The February Revolution of 1917 was the first of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. Centered around the then capital Petrograd in March . Its immediate result was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire...

as an example of workers taking power for themselves. However, after the October revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

, it became evident that the Bolsheviks and the anarchists had very different ideas. Anarchist Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century....

, deported from the United States to Russia in 1919, was initially enthusiastic about the revolution, but was left sorely disappointed, and began to write her book My Disillusionment in Russia

My Disillusionment in Russia

My Disillusionment in Russia is a book published in 1923 by Emma Goldman describing her experiences in Soviet Russia from 1920 to 1921, where she saw the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

. Anarchist Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin

Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian zoologist, evolutionary theorist, philosopher, economist, geographer, author and one of the world's foremost anarcho-communists. Kropotkin advocated a communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations between...

, proffered trenchant criticism of the emergent Bolshevik bureaucracy in letters to Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

, noting in 1920: "[a party dictatorship] is positively harmful for the building of a new socialist system. What is needed is local construction by local forces ... Russia has already become a Soviet Republic only in name." Many anarchists fought against Russian, Spanish and Greek Communists; many were killed by them, such as Lev Chernyi

Lev Chernyi

Pável Dimítrievich Turchanínov , known by the pseudonym Lev Chernyi , was a Russian anarchist theorist, activist and poet, and a leading figure of the Third Russian Revolution. His early thought was individualist, rejecting anarcho-communism as a threat to individual liberty...

, Camillo Berneri

Camillo Berneri

Camillo Berneri was an Italian professor of philosophy, anarchist militant, propagandist and theorist....

and Constantinos Speras

Constantinos Speras

Constantinos Speras was a Greek anarcho-syndicalist, and one of the pioneers of the working class trade-union movement in Greece. He spent the biggest part of his life in prison and in exile, totalling 109 times...

. As well a lot of anarchists were massacred in concentration camps by Communists.

Conservatives

The communist principle of redistribution of wealth acquired in capitalist accumulation is held by anti-communists to be opposed to the principle of voluntary free tradeFree trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

. Furthermore many capitalist theorists believe that communism interferes with the price mechanism that is only optimized in private competition. See economic calculation debate.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx lays out a 10-point plan advising the redistribution of land and production, and Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises was an Austrian economist, philosopher, and classical liberal who had a significant influence on the modern Libertarian movement and the "Austrian School" of economic thought.-Biography:-Early life:...

argues that the initial and ongoing forms of redistribution constitute direct coercion. Neither Marx's 10-point plan nor the rest of the manifesto say anything about who has the right to carry out the plan. Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman was an American economist, statistician, academic, and author who taught at the University of Chicago for more than three decades...

argued that the absence of voluntary economic activity makes it too easy for repressive political leaders to grant themselves coercive powers. Friedman's view was also shared by Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August Hayek CH , born in Austria-Hungary as Friedrich August von Hayek, was an economist and philosopher best known for his defense of classical liberalism and free-market capitalism against socialist and collectivist thought...

and John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA , was a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments...

, both of whom believed that capitalism is vital for freedom to survive and thrive.

Many capitalist critics see a key error in communist economic theory, which predicts that in capitalist societies, the bourgeoisie will accumulate ever-increasing capital and wealth, while the lower classes become more dependent on the ruling class for survival, selling their labor power

Labor power

Labour power is a crucial concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of capitalist political economy. He regarded labour power as the most important of the productive forces of human beings. Labour power can be simply defined as work-capacity, the ability to do work...

for the most minimal of salaries, blaming the effect on capitalism. Anti-communists point to the overall rise in the average standard of living

Standard of living

Standard of living is generally measured by standards such as real income per person and poverty rate. Other measures such as access and quality of health care, income growth inequality and educational standards are also used. Examples are access to certain goods , or measures of health such as...

in the non-communist West and claim that both the rich and poor have steadily gotten richer. Anti-communists argue that former Third World

Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either capitalism and NATO , or communism and the Soviet Union...

countries that have successfully escaped poverty in recent decades have done so using capitalism, most notably India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

. Anti-communists cite the Mengistu regime in Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

as an example how a Communist regime in the Third World failed to achieve development or economic growth.

Objectivism

ObjectivistsObjectivism (Ayn Rand)

Objectivism is a philosophy created by the Russian-American philosopher and novelist Ayn Rand . Objectivism holds that reality exists independent of consciousness, that human beings have direct contact with reality through sense perception, that one can attain objective knowledge from perception...

argue that wealth (or any other human value) is the creation of individual minds, that human nature requires motivation by personal incentive, and therefore, that only political and economic freedom are consistent with human prosperity. This is demonstrated, they believe, by the comparative prosperity of free market

Free market

A free market is a competitive market where prices are determined by supply and demand. However, the term is also commonly used for markets in which economic intervention and regulation by the state is limited to tax collection, and enforcement of private ownership and contracts...

and socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

economies. Objectivist Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand was a Russian-American novelist, philosopher, playwright, and screenwriter. She is known for her two best-selling novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged and for developing a philosophical system she called Objectivism....

writes that communist leaders typically claim to work for the common good, but many or all of them have been corrupt and totalitarian.

Sociobiology

SociobiologistSociobiology

Sociobiology is a field of scientific study which is based on the assumption that social behavior has resulted from evolution and attempts to explain and examine social behavior within that context. Often considered a branch of biology and sociology, it also draws from ethology, anthropology,...

Edward O. Wilson said "Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species," meaning that while ant

Ant

Ants are social insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from wasp-like ancestors in the mid-Cretaceous period between 110 and 130 million years ago and diversified after the rise of flowering plants. More than...

s and other social insects appear to live in communist-like societies, they only do so because they are forced to because they lack reproductive independence. Worker ants are sterile, and individual ants cannot reproduce without a queen, so ants are forced to live in centralised societies. Humans possess reproductive independence, so they can give birth to offspring without the need of a "queen". According to Wilson, humans enjoy their maximum level of Darwinian fitness only when they look after themselves and their families, while finding innovative ways to use the societies they live in for their own benefit.

Ex-communists

Many ex-communists have turned into anti-communists. Mikhail GorbachevMikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is a former Soviet statesman, having served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 until 1991, and as the last head of state of the USSR, having served from 1988 until its dissolution in 1991...

turned from a Communist into a social democrat. Milovan Đilas, was a former Yugoslav

Yugoslavs

Yugoslavs is a national designation used by a minority of South Slavs across the countries of the former Yugoslavia and in the diaspora...

Communist official, who became a prominent dissident

Dissident

A dissident, broadly defined, is a person who actively challenges an established doctrine, policy, or institution. When dissidents unite for a common cause they often effect a dissident movement....

and critic of Communism. Leszek Kołakowski was a Polish Communist who became a famous anti-communist. He was best known for his critical analyses of Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

thought, especially his acclaimed three-volume history, Main Currents of Marxism, which is "considered by some to be one of the most important books on political theory of the 20th century." The God That Failed

The God that Failed

The God That Failed is a 1949 book which collects together six essays with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-communists, who were writers and journalists. The common theme of the essays is the authors' disillusionment with and abandonment of communism...

is a 1949 book which collects together six essay

Essay

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author's personal point of view. Essays can consist of a number of elements, including: literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. The definition...

s with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-Communists

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

, who were writers and journalists. The common theme of the essays is the authors' disillusionment with and abandonment of Communism. The promotional byline

Byline

The byline on a newspaper or magazine article gives the name, and often the position, of the writer of the article. Bylines are traditionally placed between the headline and the text of the article, although some magazines place bylines at the bottom of the page, to leave more room for graphical...

to the book is "Six famous men tell how they changed their minds about Communism." Another notable anti-communist was Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers was born Jay Vivian Chambers and also known as David Whittaker Chambers , was an American writer and editor. After being a Communist Party USA member and Soviet spy, he later renounced communism and became an outspoken opponent later testifying in the perjury and espionage trial...

, a former Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

spy who testified against his fellow spies before the House Un-American Activities Committee

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities or House Un-American Activities Committee was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives. In 1969, the House changed the committee's name to "House Committee on Internal Security"...

.

Other anti-communists who were once Marxists include the writers Max Eastman

Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet, and a prominent political activist. For many years, Eastman was a supporter of socialism, a leading patron of the Harlem Renaissance and an activist for a number of liberal and radical causes...

, John Dos Passos

John Dos Passos

John Roderigo Dos Passos was an American novelist and artist.-Early life:Born in Chicago, Illinois, Dos Passos was the illegitimate son of John Randolph Dos Passos , a distinguished lawyer of Madeiran Portuguese descent, and Lucy Addison Sprigg Madison of Petersburg, Virginia. The elder Dos Passos...

, James Burnham

James Burnham

James Burnham was an American popular political theorist, best known for his influential work The Managerial Revolution, published in 1941. Burnham was a radical activist in the 1930s and an important factional leader of the American Trotskyist movement. In later years he left Marxism and produced...

, Morrie Ryskind

Morrie Ryskind

Morrie Ryskind was an American dramatist, lyricist and writer of theatrical productions and motion pictures, who became a conservative political activist later in life.-Biography:...

, Frank Meyer

Frank Meyer

Frank Straus Meyer was a libertarian political philosopher and co-founding editor of the National Review magazine.-Personal life:...

, Will Herberg

Will Herberg

Will Herberg was an American Jewish writer, intellectual and scholar. He was known as a social philosopher and sociologist of religion, as well as a Jewish theologian.-Early life:...

, Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook was an American pragmatic philosopher known for his contributions to public debates.A student of John Dewey, Hook continued to examine the philosophy of history, of education, politics, and of ethics. After embracing Marxism in his youth, Hook was known for his criticisms of...

, Louis Fischer

Louis Fischer

Louis Fischer was a Jewish-American journalist. Among his works were a contribution to the ex-Communist treatise The God that Failed, The Life of Lenin, which won a 1965 National Book Award, as well as a biography of Mahatma Gandhi entitled The Life of Mahatma Gandhi...

, André Gide

André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in literature in 1947. Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anticolonialism between the two World Wars.Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide...

, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler CBE was a Hungarian author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria...

, Ignazio Silone

Ignazio Silone

Ignazio Silone was the pseudonym of Secondino Tranquilli, an Italian author and politician.-Early life and career:...

, Stephen Spender

Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender CBE was an English poet, novelist and essayist who concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle in his work...

, Peter Hitchens

Peter Hitchens

Peter Jonathan Hitchens is an award-winning British columnist and author, noted for his traditionalist conservative stance. He has published five books, including The Abolition of Britain, A Brief History of Crime, The Broken Compass and most recently The Rage Against God. Hitchens writes for...

and Richard Wright

Richard Wright

Richard Wright may refer to:* Richard Wright , African-American novelist, writer, poet, essayist* Richard Wright , also known as Rick Wright, English musician, founding member of Pink Floyd...

. Anti-communists who were once socialists

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

, modern liberals or social democrats

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political ideology of the center-left on the political spectrum. Social democracy is officially a form of evolutionary reformist socialism. It supports class collaboration as the course to achieve socialism...

include: John Chamberlain

John Chamberlain

John Angus Chamberlain is an American sculptor.Born in Rochester, Indiana, John Chamberlain spent much of his youth in Chicago. After serving in the navy from 1943 to 1946, he attended the Art Institute of Chicago and Black Mountain College...

, Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August Hayek CH , born in Austria-Hungary as Friedrich August von Hayek, was an economist and philosopher best known for his defense of classical liberalism and free-market capitalism against socialist and collectivist thought...

, Raymond Moley

Raymond Moley

Raymond Charles Moley was a leading New Dealer who became its bitter opponent before the end of the Great Depression....

, Norman Podhoretz

Norman Podhoretz

Norman B. Podhoretz is an American neoconservative pundit and writer for Commentary magazine.-Early life:The son of Julius and Helen Podhoretz, Jewish immigrants from the Central European region of Galicia, Podhoretz was born and raised in Brownsville, Brooklyn...

and Irving Kristol

Irving Kristol

Irving Kristol was an American columnist, journalist, and writer who was dubbed the "godfather of neoconservatism"...

.

Fascism and far-right politics

Fascism is often considered a reaction to communist and socialist uprisings in Europe. Italian fascism, founded and led by Benito MussoliniBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

, took power with the blessing of Italy's king after years of leftist unrest led many conservatives

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

to fear that a communist revolution was inevitable. Historians Ian Kershaw

Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw is a British historian of 20th-century Germany whose work has chiefly focused on the period of the Third Reich...

and Joachim Fest

Joachim Fest

Joachim Clemens Fest was a German historian, journalist, critic and editor, best known for his writings and public commentary on Nazi Germany, including an important biography of Adolf Hitler and books about Albert Speer and the German Resistance...

argue that in post-World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

Germany, the Nazis were one of many nationalist and fascistic political parties contending for the leadership of Germany’s anti-communist

Anti-communism

Anti-communism is opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War in 1947.-Objections to communist theory:...

movement, and of the German state. The Nazis claimed that communism was dangerous to the well-being of nations because of its intention to dissolve private property

Private property

Private property is the right of persons and firms to obtain, own, control, employ, dispose of, and bequeath land, capital, and other forms of property. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which refers to assets owned by a state, community or government rather than by...

, its support of class conflict

Class conflict

Class conflict is the tension or antagonism which exists in society due to competing socioeconomic interests between people of different classes....

, its aggression against the middle class, its hostility to small businessmen, and its atheism

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

. Nazism rejected class conflict-based socialism and economic egalitarianism

Egalitarianism

Egalitarianism is a trend of thought that favors equality of some sort among moral agents, whether persons or animals. Emphasis is placed upon the fact that equality contains the idea of equity of quality...

, favouring instead a stratified

Social stratification

In sociology the social stratification is a concept of class, involving the "classification of persons into groups based on shared socio-economic conditions ... a relational set of inequalities with economic, social, political and ideological dimensions."...

economy with classes based on merit and talent, retaining private property

Private property

Private property is the right of persons and firms to obtain, own, control, employ, dispose of, and bequeath land, capital, and other forms of property. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which refers to assets owned by a state, community or government rather than by...

, and the creation of national solidarity that transcends class distinction.

In Europe, numerous aristocrats

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

, conservative intellectuals, capitalists and industrialists lent their support to fascist movements. During the late 1930s and the 1940s, several other anti-communist regimes and groups supported Nazism: the Falange

Falange

The Spanish Phalanx of the Assemblies of the National Syndicalist Offensive , known simply as the Falange, is the name assigned to several political movements and parties dating from the 1930s, most particularly the original fascist movement in Spain. The word means phalanx formation in Spanish....

in Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

; the Vichy regime

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

and the Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism

Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism

The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism was a collaborationist French militia founded on July 8, 1941. It gathered various collaborationist parties, including Marcel Bucard's Mouvement Franciste, Marcel Déat's National Popular Rally, Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party, Eugène...

(Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

Infantry Regiment 638) in France; the Cliveden set

Cliveden set

The Cliveden Set were a 1930s right-wing, upper class group of prominent individuals politically influential in pre-World War II Britain, who were in the circle of Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor...

, Lord Halifax, and associates of Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

in Britain.; and, in South America, movements such as Brazilian Integralism

Brazilian Integralism

Brazilian Integralism was a fascist political movement in Brazil, created on October 1932. Founded and led by Plínio Salgado, a literary figure who was somewhat famous for his participation in the 1922 Modern Art Week, the movement had adopted some characteristics of European mass movements of...

.

Anti-communism remained a theme in far right politics after the war. For example, in the US, Frank L. Britton, editor of The American Nationalist published a book, Behind Communism, in 1952 which disseminated the myth that Communism was a Jewish conspiracy originating in Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

.

Buddhists

Thích Huyền Quang was a prominent VietnamVietnam

Vietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

ese Buddhist monk

Bhikkhu