Prince Rupert of the Rhine

Encyclopedia

Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Bavaria, 1st Duke of Cumberland, 1st Earl of Holderness , commonly called Prince Rupert of the Rhine, KG

, FRS

(17 December 1619 – 29 November 1682) was a noted soldier, admiral, scientist, sportsman, colonial governor and amateur artist during the 17th century. Rupert was a younger son of the German prince Frederick V, Elector Palatine

and his wife Elizabeth

, the eldest daughter of James I of England

. Thus Rupert was the nephew of King Charles I of England

, who created him Duke of Cumberland

and Earl of Holderness

, and the first cousin of King Charles II of England

. His sister Electress Sophia was the mother of George I of Great Britain

.

Prince Rupert had a varied career. He was a soldier from a young age, fighting against Spain

in the Netherlands

during the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648), and against the Holy Roman Emperor

in Germany during the Thirty Years' War

(1618–48). Aged 23, he was appointed commander of the Royalist

cavalry

during the English Civil War

, becoming the archetypal Cavalier

of the war and ultimately the senior Royalist general. He surrendered after the fall of Bristol

and was banished from England. He served under Louis XIV of France

against Spain, and then as a Royalist privateer

in the Caribbean. Following the Restoration, Rupert returned to England, becoming a senior British naval commander during the Second

and Third

Anglo-Dutch wars

, engaging in scientific invention, art, and serving as the first Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company

. Prince Rupert died in England in 1682, aged 62.

Rupert is considered to have been a quick-thinking and energetic cavalry

general, but ultimately undermined by his youthful impatience in dealing with his peers during the Civil War. In the Interregnum, Rupert continued the conflict against Parliament

by sea from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean, showing considerable persistence in the face of adversity. As the head of the Royal Navy

in his later years, he showed greater maturity and made impressive and long-lasting contributions to the Royal Navy's doctrine

and development. As a colonial governor, Rupert shaped the political geography of modern Canada (Rupert's Land

was named in his honour) and played a role in the early African slave trade

. Rupert's varied and numerous scientific and administrative interests combined with his considerable artistic skills made him one of the more colourful individuals of the Restoration period.

Rupert was born in Prague

Rupert was born in Prague

in 1619, at the time of the Thirty Years' War

, to Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart

. He was declared a prince by the principality of Lusatia

. Rupert's father, Frederick V

, as ruler of the Palatinate, was a leading member of the Holy Roman Empire

, the head of the Protestant Union

, with a martial family tradition stretching back several centuries. His family was also at the heart of the network of Protestant rulers across the north of Europe at the time. Frederick enjoyed close ties through his mother to the ruling House of Orange-Nassau

in the United Provinces

. Elizabeth was a daughter of King James I of England

and sister of King Charles I of England

, and related in turn to the Danish royal family. The family enjoyed an extremely wealthy lifestyle in Heidelberg

, enjoying the famous palace gardens—the Hortus Palatinus

, designed by Inigo Jones

and Salomon de Caus

—and a lavish castle with one of the best libraries in Europe.

Frederick had allied himself with rebellious Protestant Bohemian

nobility in 1619, expecting support from the Protestant Union in his revolt against the Catholic Ferdinand II

, the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor. This support was not forthcoming, resulting in a crushing defeat at the hands of his Catholic enemies at the Battle of White Mountain

. With Frederick now outlawed the family fled from Bohemia

to the Netherlands

, where Rupert spent his childhood. Rupert's parents were mockingly termed the "Winter King and Queen" as a consequence of their reigns in Bohemia having lasted only a single season.

Rupert was almost left behind in the court's rush to escape Ferdinand's advance on Prague, until Christopher Dhona, a court member, tossed the prince into a carriage at the last moment. Rupert accompanied his parents to The Hague

, where he spent his early years at the Hof te Wassenaer. Rupert's mother paid her children little attention even by the standards of the day, apparently preferring her pet monkeys and dogs. Instead, Frederick employed Monsieur and Madame de Plessen to act as governors to his children, with instructions to inculcate a positive attitude towards the Bohemians and the English, and to bring them up as strict Calvinists

. The result was a strict school routine including logic

, mathematics, writing, drawing, singing and playing instruments. As a child, Rupert was at times badly behaved, 'fiery, mischievous, and passionate' and earned himself the nickname Robert le Diable, or "Rupert The Devil". Nonetheless, Rupert proved to be an able student. By the age of 3 he could speak some English, Czech and French, and mastered German while still young, but had little interest in Latin and Greek. He excelled in art, being taught by Gerard van Honthorst

, and found the maths and sciences easy. By the time he was 18 he stood about 6 ft 4 in tall and had become a dashing young prince.

Rupert's family continued their attempts to regain the Palatinate during their time in The Hague. Money was short, with the family relying upon a relatively small pension from The Hague, the proceeds from family investments in Dutch raids on Spanish shipping, and revenue from pawned family jewellery. By 1625, however, Frederick had convinced an alliance of nations—including England, France and Sweden—to support his attempts to regain the Palatinate and Bohemia. By the early 1630s this appeared closer than ever. Rupert's father, Frederick, had increasingly invested in relationship with the Swedish King Gustavus

, now the dominant religious leader in Germany. In 1632, however, the two men disagreed over Gustavus' insistence that Frederick provide equal rights to his Lutheran and Calvinist subjects after regaining his lands; Frederick refused and started to return to The Hague. He died of a fever along the way and was buried in an unmarked grave. Rupert had lost his father at the age of 13, and Gustavus' death at the battle of Lützen

in the same month deprived the family of a critical Protestant ally. With Frederick gone, King Charles proposed that the family move to England; Rupert's mother declined, but asked that Charles extend his protection to her remaining children instead.

Rupert spent the beginning of his teenage years in England between the courts of The Hague

Rupert spent the beginning of his teenage years in England between the courts of The Hague

and his uncle King Charles I, before being captured and imprisoned in Linz

during the middle stages of the Thirty Years' War

. Rupert had become a soldier early; at the age of 14 he attended the Dutch pas d'armes

with the Protestant Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange

, later that year he fought alongside him at the siege of Rheinberg

, and by 1635 he was acting as a military lifeguard

to Prince Frederick. Rupert went on to fight against imperial Spain in the successful campaign around Breda

in 1637 during the Eighty Years' War in the Netherlands. By the end of this period, Rupert had acquired a reputation for fearlessness in battle, high spirits and considerable industry.

In between these campaigns Rupert had visited his uncle's court in England. The Palatinate cause was a popular Protestant issue in England, and in 1637 a general public subscription helped fund an expedition under Charles Louis

to try and regain the electorate as part of a joint French campaign. Rupert was placed in command of a Palatinate cavalry regiment, and his later friend Lord Craven, an admirer of Rupert's mother, assisted in raising funds and accompanied the army on the campaign. The campaign ended badly at the Battle of Vlotho

(17 October 1638) during the invasion of Westphalia

; Rupert escaped death, but was captured by the forces of the Imperial General Melchior von Hartzfeld towards the end of the battle.

After a failed attempt to bribe his way free of his guards, Rupert was imprisoned in Linz

. Lord Craven, also taken in the battle, attempted to persuade his captors to allow him to remain with Rupert, but was refused. Rupert's imprisonment was surrounded by religious overtones. His mother was deeply concerned that he might be converted from Calvinism

to Catholicism; his captors, encouraged by Emperor Ferdinand III

, deployed Jesuit priests in an attempt to convert

him. The Emperor went further, proffering the option of freedom, a position as an Imperial general and a small principality if Rupert would convert. Rupert refused.

As time went on, Rupert's imprisonment became more relaxed on the advice of the Archduke Leopold

, Ferdinand's younger brother, who met and grew to like Rupert. Rupert practised etching, played tennis, practised shooting, read military textbooks and was taken on accompanied hunting trips. He also entered into a romantic affair with Susan Kuffstein, the daughter of Count von Kuffstein, his gaoler. He also received a present of a rare white poodle

, a dog that Rupert called Boye

, and which remained with him into the English Civil War

. Despite attempts by a Franco-Swedish army to seize Linz and free Rupert, his release was ultimately negotiated through Leopold and the Empress Anna Maria; in exchange for a commitment never again to take up arms against the Emperor, Rupert would be released. Rupert formally kissed the Emperor's hand at the end of 1641, turned down a final offer of an Imperial command and left Germany for England.

. He had considerable success during the early years of the war, his drive, determination and experience of European techniques bringing him early victories. As the war progressed, Rupert's youth and lack of maturity in managing his relationships with other Royalist commanders ultimately resulted in his removal from his post and ultimate retirement from the war. Throughout the conflict, however, Rupert also enjoyed a powerful symbolic position: he was an iconic Royalist Cavalier

and as such was frequently the subject of both Parliamentarian and Royalist propaganda, an image which has endured over the years.

, and after one initial failure, evaded the pro-Parliamentary navy and landed in Newcastle

. Riding across country, he finally found the King with a tiny army at Leicester Abbey

, and was promptly appointed General of Horse

, a coveted appointment at the time in European warfare.

Rupert set about recruiting and training: with great effort he had put together a partially trained mounted force of 3,000 cavalry by the end of September. Rupert's reputation continued to rise. Leading a sudden, courageous charge, he routed a Parliamentarian force at Powick Bridge

in September 1642. Although a small engagement, this had a propaganda and morale value far exceeding the importance of the battle itself, and Rupert became an heroic figure for many young men in the Royalist camp.

Rupert joined the King in the advance on London, playing a key role in the resulting Battle of Edgehill

Rupert joined the King in the advance on London, playing a key role in the resulting Battle of Edgehill

in October. Once again, Rupert was at his best with swift battlefield movements; the night before, he had undertaken a forced march and seized the summit of Edgehill, giving the Royalists a superior position. Some of the weaknesses of Rupert's character began to display themselves, however, when he quarrelled with his fellow infantry commander, Lindsey

. Rupert vigorously interjected—probably correctly, but certainly tactlessly—that Lindsey should deploy his men in the modern Swedish fashion that Rupert was used to in Europe, which would have maximised their available firepower. The result was an argument in front of the troops and Lindsey's resignation and replacement by Sir Jacob Astley

. In the subsequent battle Rupert's men made a dramatic cavalry charge, but despite his best efforts a subsequent scattering and loss of discipline turned a potential victory into a stalemate.

After Edgehill, Rupert asked Charles for a swift cavalry attack on London before the Earl of Essex

's army could return. The King's senior counsellors, however, urged him to advance slowly on the capital with the whole army. By the time they arrived, the city had organized defences against them. Some argue that, in delaying, the Royalists had perhaps lost their best chance of winning the war, although others have argued that Rupert's proposed attack would have had trouble penetrating a hostile London. Instead, early in 1643, Rupert began to clear the South-West, taking Cirencester

in February before moving further against Bristol

, a key port. Rupert took Bristol in July with his brother Maurice using Cornish

forces and was appointed Governor of the city. By mid-1643 Rupert had in fact become so well known that he was an issue in any potential peace accommodation—Parliament was seeking to see him punished as part of any negotiated solution, and the presence of Rupert at the court, close to the King during the negotiations, was perceived as a bellicose statement in itself.

During the second half of the war, political opposition within the Royalist senior leadership against Rupert continued to grow. Rupert's personality during the war had made him both friends and enemies. He enjoyed a "frank and generous disposition", showed a "quickness of... intellect", was prepared to face grave dangers, and could be thorough and patient when necessary. However, he lacked the social gifts of a courtier

During the second half of the war, political opposition within the Royalist senior leadership against Rupert continued to grow. Rupert's personality during the war had made him both friends and enemies. He enjoyed a "frank and generous disposition", showed a "quickness of... intellect", was prepared to face grave dangers, and could be thorough and patient when necessary. However, he lacked the social gifts of a courtier

, and his humour could turn into a "sardonic wit and a contemptuous manner": with a hasty temper, he was too quick to say who he respected, and who he disliked. The result was that, while Rupert could inspire great loyalty in some, especially his men, he also made many enemies at the Royal court. Rupert had quarrelled with Lindsey

at Edgehill; when he took Bristol, he managed to slight the Marquis of Hertford

, the rather lethargic but politically significant Royalist leader of the south-west. Most critically, Rupert fell out with George Digby

, a favourite of both the King and the Queen. Digby was a classic courtier, with a "darting wit and fluent tongue"; Rupert fell to arguing with him repeatedly in meetings. The result was that towards the end of the war Rupert's position at court was increasingly undermined by his enemies.

Rupert continued to impress militarily. By 1644, now the Duke of Cumberland

and Earl of Holderness

, he led the relief of Newark and York

and its castle

. Having marched north, taking Bolton

and Liverpool

along the way in two bloody assaults, Rupert then intervened in Yorkshire in two highly effective manoeuvres, in the first outwitting the enemy forces at Newark with his sheer speed; in the second, striking suddenly across country and approaching York by surprise from the north. Rupert then commanded much of the royalist army at its defeat at Marston Moor, with much of the blame falling on the poor working relationship between Rupert and the Marquis of Newcastle, and orders from the King that wrongly conveyed a desperate need for a speedy success in the north.

In November 1644 Rupert was appointed General of the entire Royalist army, which increased already marked tensions between him and a number of the King's councillors. By May 1645, and now desperately short of supplies, Rupert captured Leicester

but suffered a severe reversal at the Battle of Naseby

a month later. Although Rupert had counselled the King against accepting battle at Naseby, the opinions of Digby had won the day in council: nonetheless, Rupert's defeat damaged him, rather than Digby, politically. After Naseby, Rupert regarded the Royalist cause as lost, and urged Charles to conclude a peace with Parliament. Charles, still supported by an optimistic Digby, believed he could win the war. By late summer Rupert had become trapped in Bristol by Parliamentary forces; faced with an impossible military situation on the ground, Rupert surrendered Bristol in September 1645, and Charles dismissed him from his service and command.

Rupert responded by making his way across Parliament-held territory to the King at Newark

with Prince Maurice and around a hundred men, fighting their way through smaller enemy units and evading larger ones. King Charles attempted to order Rupert to desist, fearing an armed coup

, but Rupert arrived at the royal court anyway. After a difficult meeting, Rupert convinced the King to hold a court-martial

over his conduct at Bristol, which exonerated him and Maurice. After a final argument over the fate of the governor of Newark, who had let Rupert into the royal court to begin with, Rupert resigned and left the service of King Charles, along with most of his best cavalry officers. Earlier interpretations of this event have focused on Rupert's concern for his honour in the face of his initial dismissal by the King; later works have highlighted the practical importance of the courts martial to Rupert's future employability as a mercenary in Europe, given that Rupert knew that the war by this point was effectively lost. Rupert and Maurice spent the winter of 1645 in Woodstock, examining options for employment under the Venetian Republic, before returning to Oxford and the King in 1646. Rupert and the King were reconciled, the Prince remaining to defend Oxford when the King left for the north. After the ensuing siege and surrender of Oxford

in 1646, Parliament banished both Rupert and his brother from England.

Rupert's contemporaries believed him to have been involved in some of the bloodier events of the war, although later histories have largely exonerated him. Rupert had grown up surrounded by the relatively savage customs of the Thirty Years' War

Rupert's contemporaries believed him to have been involved in some of the bloodier events of the war, although later histories have largely exonerated him. Rupert had grown up surrounded by the relatively savage customs of the Thirty Years' War

in Europe. Shortly after his arrival in England he caused consternation by following similar practices; one of his early acts was to demand two thousand pounds from the people of Leicester

for the King as the price of not sacking Leicester. Although in keeping with European practices, this was not yet considered appropriate behaviour in England and Rupert was reprimanded by the King.

Rupert's reputation never truly recovered, and in subsequent sieges and attacks he was frequently accused of acting without restraint. Birmingham

, a key arms-producing town, was taken in April 1643, and Rupert faced allegations—probably untrue—of wilfully burning the town to the ground. Shortly afterwards Rupert attempted to take the town of Lichfield

, whose garrison had executed Royalist prisoners, angrily promising to kill all the soldiers inside. Only the urgent call for assistance from the King prevented him from doing so, forcing him to agree more lenient terms in exchange for a prompt surrender. Towards the end of the war, practices were changing for the worse across all sides; a rebellious Leicester was retaken by the Prince in May 1645, and no attempt was made to limit the subsequent killing and plunder.

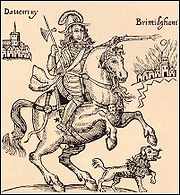

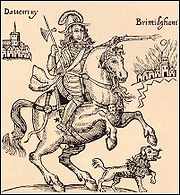

Rupert was accordingly a prominent figure in Parliamentary propaganda. He faced numerous accusations of witchcraft

, either personally or by proxy through his pet dog, Boye

. Boye, a large white hunting poodle

, accompanied Rupert everywhere from 1642 up until the dog's death at Marston Moor

and was widely suspected of being a witch's familiar

. There were numerous accounts of Boye's abilities; some suggested that he was the Devil in disguise, come to help Rupert. Pro-Royalist publications ultimately produced parodies of these, including one which listed Rupert's dog as being a "Lapland Lady" transformed into a white dog; Boye was able, apparently, to find hidden treasure, possessed invulnerability to attack, could catch bullets fired at Rupert in his mouth, and could prophesy as well as the 16th-century soothsayer

, Mother Shipton.

After the end of the First English Civil War

After the end of the First English Civil War

Rupert was employed by the young King Louis XIV of France

to fight the Spanish during the final years of the Thirty Years' War

(1618–1648). Rupert's military employment was complicated by his promises to the Holy Roman Emperor

that had led to his release from captivity in 1642, and his ongoing commitment to the Royalist faction in exile. Throughout the period Rupert was inconvenienced by his lack of secure income, and his ongoing feuds with other leading members of the Royalist circle.

but found it still dominated by the Queen

and her favourite, Rupert's enemy Digby

. Instead, Rupert moved on, accepting a well-paid commission from Anne of Austria

to serve Louis XIV of France

as a mareschal de camp

, subject to Rupert being free to leave French service to fight for King Charles, should he be called upon to do so. In 1647 Rupert fought under Marshal de Gassion

against the Spanish. After a three week siege, Rupert took the powerful fortress of La Bassée

through quiet negotiations with the enemy commander—an impressive accomplishment, and one that won him favour in French court circles. Gassion and Rupert were ambushed shortly afterwards by a Spanish party; during the resulting fight, Rupert was shot in the head and seriously injured. Afterwards, Gassion noted: "Monsieur, I am most annoyed that you are wounded." "And me also," Rupert is recorded as replying. Gassion was himself killed shortly afterwards, and Rupert returned to St Germain to recuperate.

broke out, and Rupert informed the French King that he would be returning to King Charles' service. The Parliamentary navy mutinied

in favour of the King and sailed for Holland, providing the Royalists with a major fleet for the first time since the start of the civil conflict; Rupert joined the fleet under the command of the Duke of York

, who assumed the rank of High Admiral. Rupert argued that the fleet should be used to rescue the King, then being held prisoner on the Isle of Wight

, while others advised sailing in support of the fighting in the north. The fleet itself rapidly lost discipline, with many vessels' crews focussing on seizing local ships and cargoes. This underlined a major problem for the Royalists—the cost of maintaining the new fleet was well beyond their means. Discipline continued to deteriorate, and Rupert had to intervene personally several times, including defusing one group of mutinous

sailors by suddenly dangling the ringleader over the side of his vessel and threatening to drop him into the sea. Most of the fleet finally switched sides once more, returning to England in late 1648.

Then, following a degree of reconciliation with Charles, Rupert obtained command of the Royalist fleet himself. The intention was to restore Royalist finances by using the remaining vessels of the fleet to conduct a campaign of organised piracy

against English shipping across the region. One of the obstacles that this plan faced was the growing strength of the Parliamentary fleet and the presence of Robert Blake

, one of the finest admirals of the period, as Rupert's opponent during the campaign.

Rupert's naval campaign formed two phases. The first involved the Royalist fleet sailing from Kinsale

in Ireland to Lisbon

in Portugal. He took three large ships, the , the Convertine and the Swallow, accompanied by four smaller vessels. Rupert sailed to Lisbon taking several prizes on route, where he received a warm welcome from King John IV

, the ruler of recently-independent Portugal, who was a supporter of Charles II. Blake arrived shortly afterwards with a Parliamentary fleet, and an armed stand-off ensued. Tensions rose, skirmishes began to break out and King John became increasingly keen for his Royalist guests to leave. In October 1650, Rupert's fleet, now comprising six vessels, broke out and headed into the Mediterranean. Still pursued by Blake, the Royalist fleet manoeuvred up the Spanish coast, steadily losing vessels to their pursuers;

The second phase of the campaign then began, as Rupert crossed back into the Atlantic and, during 1651, cutting west to the Azores

capturing vessels as he went. He intended to continue on to the West Indies, where there would be many rich targets, but encountered a late summer storm, leading to the sinking of the Constant Reformation with the loss of 333 lives—almost including Rupert's brother, Prince Maurice, who only just escaped—and a great deal of captured treasure. Turning back to regroup, repair and re-equip in early 1652, Rupert's reduced force moored at Cape Blanc, an island near what is now Mauritania

. Rupert took the opportunity to explore and acquired a Moorish

servant boy, who remained in his service for many years. Rupert also explored 150 miles up the Gambia River

, taking two Spanish vessels as prizes and catching malaria

in the process.

Rupert then finally made a successful crossing into the Caribbean, landing first at St Lucia, before continuing up the chain of the Antilles

to the Virgin Islands

. There the fleet was hit by a terrible hurricane, which scattered the ships and sank the Defiance, this time with Prince Maurice on board. It was a while before Maurice's death became certain, which came as a terrible blow to Rupert. He was forced to return to Europe, arriving in France in March 1653 with a fleet of five ships. It became clear, as the profits and losses of the piracy campaign were calculated, that the venture had not been as profitable as hoped. This complicated tensions in the Royalist court, and Charles II and Rupert eventually split the spoils, after which Rupert, tired and a little bitter, returned to France to recuperate from the long campaign.

In 1654, Rupert appears to have been involved in a plot to assassinate Oliver Cromwell

, an event that would then have been followed by a coup

, the landing of a small army in Sussex

, and the restoration of Charles II. Charles himself is understood to have rejected the assassination proposal, but three conspirators—who implicated Rupert in the plan—were arrested and confessed in London. Rupert's presence at the royal court continued to be problematic; as in 1643, he was regarded by Edward Hyde

(later Earl of Clarendon

) and others as a bellicose figure and an obstacle to peace negotiations; in 1655 Rupert left for Germany.

to visit his brother Charles Louis

, now partially restored as Elector Palatine, where the two had an ambivalent reunion. Charles Louis and Rupert had not been friendly as children and had almost ended up on opposite sides during the Civil War. To make matters worse, Charles Louis had been deprived of half the old Palatinate under the Peace of Westphalia

, leaving him badly short of money, although he still remained responsible under the Imperial laws of apanage for providing for his younger brother and had offered the sum of £375 per annum, which Rupert had accepted. Rupert travelled on to Vienna

, where he attempted to claim the £15,000 compensation allocated to him under the Peace of Westphalia from the Emperor. Emperor Ferdinand III

warmly welcomed him, but was unable to pay such a sum immediately—instead, he would have to pay in installments, to the disadvantage of Rupert.

Over the next twelve months, Rupert was asked by the Duke of Modena in northern Italy to raise an army against the Papal States

—having done so, and with the army stationed in the Palatinate, the enterprise collapsed, with the Duke requesting that Rupert invade Spanish-held Milan

instead. Rupert moved on, having placed his brother Charles Louis in some diplomatic difficulties with Spain. Rupert travelled onwards, continuing to attempt to convince Ferdinand to back Charles II's efforts to regain his throne.

In 1656 relations between Rupert and Charles Louis deteriorated badly. Rupert had fallen in love with Louise von Degenfeld

, one of his sister-in-law's maids of honour. By bad luck, one of Rupert's notes proffering his affections fell into the possession of Charles Louis' wife Charlotte, who believed it was written to her. Charlotte was keen to engage in an affair with Rupert and became unhappy when she was declined and the mistake explained. Unfortunately, von Degenfeld was uninterested in Rupert, but was engaged in an affair with Charles Louis—this was discovered in due course, leading to the annulment of the marriage. Rupert, for his part, was unhappy that Charles Louis could not endow him with a suitable estate, and the two parted on bad terms in 1657, Rupert refusing to ever return to the Palatinate again and taking up employment under Ferdinand III

in Hungary.

During this period Rupert became closely involved in the development of the printmaking process of mezzotint, a method of 'negative' printing which eventually superseded the older woodcut

method of printmaking. Considerable academic debate surrounds the issue, but the modern consensus is that mezzotint was invented in 1642 by Ludwig von Siegen

, a German Lieutenant-Colonel who was also an amateur artist. Siegen may or may not have met Rupert: Siegen had worked as chamberlain

, and probably part-tutor, to Rupert's young cousin William VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

, with whom Rupert discussed the technique in letters from 1654, and it remains a matter of scholarly controversy. In any event, Rupert appears to have told a range of associates that he had conceived of the mezzotint process having watched a soldier scrape the rust from the barrel of his musket during a military campaign; John Evelyn

credited Rupert as the inventor of the technique in 1662, and Rupert's story was further popularised by Horace Walpole during the 18th century. Despite the dispute over the links between Rupert and Siegen, historians agree that Rupert certainly did invent the "rocker", a key tool in the mezzotint process.

Whoever had invented it, Rupert became a noted artist in mezzotint. He produced a few stylish prints in the technique, mostly interpretations of existing paintings, and introduced it to England after the Restoration

, though it was Wallerant Vaillant

, Rupert's artistic assistant or tutor, who first popularised the process and exploited it commercially. Prince Rupert's most famous and largest art work, The Great Executioner

, produced in 1658, is still regarded by critics as full of "brilliance and energy", "superb" and "one of the greatest mezzotints" ever produced; other important works by Rupert include the Head of Titian and The Standard Bearer.

in 1660, Rupert returned to England, where Charles had already largely completed the process of balancing the different factions across the country in a new administration. Since most of the better government posts were already taken, Rupert's employment was limited, although Charles rewarded him with the second highest pension he had granted, £4,000 a year. Rupert's close family ties to King Charles were critical to his warm reception; following the deaths of the Duke of Gloucester

and Princess Mary

, Rupert was the King's closest adult relation in England after his brother, the Duke of York

, and so a key member of the new regime. Rupert, as the Duke of Cumberland

, resumed his seat in the House of Lords

. For the first time in his life, Rupert's financial position was relatively secure, and he had matured—near-contemporaries described how "his temper was less explosive than formerly and his judgement sounder". Rupert continued to serve as an admiral in the Royal Navy

throughout the period, ultimately rising to the rank of "General at Sea and Land".

in 1662, taking roles on the Foreign Affairs

Committee, the Admiralty

Committee and the Tangier

Committee. Accounts vary of Rupert's role in all these committees of government. Samuel Pepys

, no friend of Rupert's, sat on the Tangier Committee with him and later declared that all Rupert did was to laugh and swear occasionally: other records, such as those of the Foreign Affairs Committee, show him taking a full and active role in proceedings.

In 1668, the King appointed Rupert to be the Constable of Windsor Castle. Rupert was already one of the Knights of the Garter, who had their headquarters at the castle, and was a close companion of the King, who would wish to be suitably entertained at the castle. Rupert immediately began to reorder the castle's defences, sorting out the garrison's accommodation, repairing the Devil's Tower, reconstructing the real tennis

court and improving the castle's hunting estate. Rupert acquired his own apartments in the castle, which were recorded as being "very singular" with some decorated with an "extraordinary" number of "pikes, muskets, pistols, bandoliers, holsters, drums, back, breast, and head pieces", and his inner chambers "hung with tapisserie, curious and effeminate pictures". King Charles II and Rupert spent much time together over the years hunting and playing tennis together at Windsor, and Rupert was also a close companion of James, the Duke of York. Rupert was considered by Pepys to be the fourth best tennis player in England.

Rupert became romantically engaged to Frances Bard (1646–1708), the daughter of the English explorer and Civil War veteran Henry Bard. Frances claimed to have secretly married Rupert in 1664, although this was denied by him and no firm proof exists to support the claim. Rupert acknowledged the son he had with Frances, Dudley Bard (1666–1686), often called "Dudley Rupert", who was schooled at Eton College

. In 1673, Rupert was urged by Charles Louis to return home, marry and establish an heir to the Palatinate, as it appeared likely that Charles Louis's own son would not survive infancy. Rupert refused, and remained in England.

For much of the 17th century, Britain was embroiled in conflict with commercial rival Holland through the Anglo-Dutch Wars

For much of the 17th century, Britain was embroiled in conflict with commercial rival Holland through the Anglo-Dutch Wars

. Rupert became closely involved in these as a senior Admiral to King Charles II, rising to command the Royal Navy

by the end of his career. Although several famous admirals of the day had previously been army commanders, including Blake and Monk

, they had commanded relatively small land forces and Rupert was still relatively unusual for the period in having both practical experience of commanding large land armies and having extensive naval experience from his campaigns in the 1650s.

At the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War

(1665–7), Rupert was appointed as one of the three squadron

commanders of the English fleet, under the overall command of the Duke of York, taking the as his flagship. As the commander of the White Squadron, Rupert fought at the Battle of Lowestoft

in 1665, breaking through the enemy defences at a critical moment; Rupert's leg was injured in the battle, an injury that caused him ongoing pain. Recalled to accompany the King during the plague

that was sweeping London, Rupert continued to argue in favour of the fleet seeking a set-piece engagement with the Dutch that would force the Dutch back to the negotiating table. The following year, Rupert was made joint commander of the fleet with Monk and given the opportunity to put this plan into practice. In June 1666, they fought the Dutch at the Four Days Battle

, one of the longest naval battles in history; the battle saw the new aggressive tactics of Rupert and Monk applied, resulting in "a sight unique till then in sailing-ship warfare, the English beating upwind and breaking the enemy's line from leeward." The Four Days Battle was at best a draw, but the St. James's Day Battle

the following month allowed Rupert and Monk to use the same tactics to inflict heavy damage on the Dutch and the battle resulted in a significant English victory. The Dutch however would see a favourable end to the war with the decisive Raid on the Medway

.

Rupert also played a prominent role in the Third Anglo-Dutch War

(1672–4). This time Louis XIV of France

was a key British ally against Holland, and it was decided that the French would form a squadron in a combined fleet. The English fleet had been much expanded, and Rupert had three ships, , and , equipped with a high-specification, annealed

and lathe

-produced gun of his own design, the Rupertinoe

. Unfortunately the cost of the weapon—three times that of a normal gun—prevented its wider deployment in the fleet. The French role in the conflict proved a problem when Charles turned to the appointment of an admiral, however; Rupert's objection to the French alliance was well known, and accordingly the King appointed the Duke of York to the role instead. Rupert was instead instructed to take over the Duke's work at the Admiralty, which he did with gusto. The Allied naval plans were stalled after the Duke's inconclusive battle with the Dutch at Solebay

.

The English plan for 1673 centred on first achieving naval dominance, followed by landing an amphibious army in Zeeland

; this would require some planning, and the King appointed the Duke as supreme commander, with Rupert as his deputy, combining the rank of General and Vice Admiral of England. During the winter of 1672, however, Charles—still childless—decided that the risk to the Duke, his heir, was too great and made Rupert supreme Allied commander in his place. Rupert began the 1673 campaign against the Dutch knowing the logistical support for his fleet remained uncertain, with many ships undermanned. The result was the Battle of Schooneveld

in June and the Battle of Texel

in August, a controversial sequence of engagements in which, at a minimum, poor communications between the French and English commanders assisted the marginal Dutch victory. Many English commentators were harsher, blaming the French for failing to fully engage in the battles and Rupert—having cautioned against the alliance in the first place—was popularly hailed as a hero. Rupert finally retired from active sea-going command later that year.

_-_nightly_battle_between_cornelis_tromp_and_eward_spragg_(willem_van_de_velde_ii,_1707).jpg) Rupert had a characteristic style as an admiral; he relied upon "energetic personal leadership backed by close contact with his officers"; having decided how to proceed in a naval campaign, however, it could be difficult for his staff to change his mind. Recent work on Rupert's role as a commander has also highlighted the progress the prince made in formulating the way that orders were given to the British fleet. Fleet communications were limited during the period, and the traditional orders from admirals before a battle were accordingly quite rigid, limiting a captain's independence in the battle. Rupert played a key part in the conferences held by the Duke of York in 1665 to review tactics and operational methods from the first Dutch war, and put these into practice before the St James Day battle. These instructions and supplementary instructions to ships' captains, which attempted to balance an adherence to standing orders with the need to exploit emerging opportunities in a battle, proved heavily influential over the next hundred years and shaped the idea that an aggressive fighting spirit should be at the core of British naval doctrine.

Rupert had a characteristic style as an admiral; he relied upon "energetic personal leadership backed by close contact with his officers"; having decided how to proceed in a naval campaign, however, it could be difficult for his staff to change his mind. Recent work on Rupert's role as a commander has also highlighted the progress the prince made in formulating the way that orders were given to the British fleet. Fleet communications were limited during the period, and the traditional orders from admirals before a battle were accordingly quite rigid, limiting a captain's independence in the battle. Rupert played a key part in the conferences held by the Duke of York in 1665 to review tactics and operational methods from the first Dutch war, and put these into practice before the St James Day battle. These instructions and supplementary instructions to ships' captains, which attempted to balance an adherence to standing orders with the need to exploit emerging opportunities in a battle, proved heavily influential over the next hundred years and shaped the idea that an aggressive fighting spirit should be at the core of British naval doctrine.

After 1673 Rupert remained a senior member of the Royal Navy and Charles' administration. Rupert allied himself with Lord Shaftesbury

on matters of foreign policy, but remained loyal to King Charles II on other issues, and was passionate about protecting the Royal Prerogative

. As a consequence he opposed Parliament's plan in 1677 to appoint him to Lord High Admiral—on the basis that only the King should be allowed to propose such appointments—but noted that he was willing to become Admiral if the King wished him to do so. The King's solution was to establish a small, empowered Admiralty Commission, of which Rupert became the first commissioner. As a result, from 1673 to 1679 Rupert was able to focus on ensuring a closer regulation of manning, gunning and the selection of officer, and priorities between the different theatres of operations that the British Navy were now involved in around the world. Rupert was also appointed to the supreme position of "General at Sea and Land", effectively assuming the wartime powers of the Lord High Admiral.

After the end of his sea-going naval career Rupert continued to be actively involved in both government and science, although he was increasingly removed from current politics. To the younger members of the court the prince appeared increasingly distant—almost from a different era. Count Grammont

After the end of his sea-going naval career Rupert continued to be actively involved in both government and science, although he was increasingly removed from current politics. To the younger members of the court the prince appeared increasingly distant—almost from a different era. Count Grammont

described Rupert as "brave and courageous even to rashness, but cross-grained and incorrigibly obstinate... he was polite, even to excess, unseasonably; but haughty, and even brutal, when he ought to have been gentle and courteous... his manners were ungracious: he had a dry hard-favoured visage, and a stern look, even when he wished to please; but, when he was out of humour, he was the true picture of reproof". Rupert's health during this period was also less robust; his head wound from his employment in France required a painful trepanning treatment, his leg wound continued to hurt and he still suffered from the malaria

he had caught whilst in The Gambia

.

, with a royal charter to set up forts, factories, troops and to exercise martial law in West Africa, in pursuit of trade in gold, silver and slaves

; Rupert was the third named member of the company's executive committee.

By then, however, Rupert had turned his primary attentions to North America. The French explorers Radisson

and des Groseilliers

had come to England after conducting a joint exploration of the Hudson Bay region in 1659; there their account attracted the attention of the King and Prince Rupert. Rupert put an initial investment of £270 of his own money into a proposal for a fresh expedition and set about raising more; despite setbacks, including the Great Fire of London

, by 1667 he had formed a private syndicate and leased the Eaglet from the King for the expedition. The Eaglet failed, but her sister vessel, the Nonsuch

, made a successful expedition, returning in 1669 with furs worth £1,400. In 1670, the King approved the charter for "The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson's Bay" that would form the Hudson's Bay Company

, which was granted a trading monopoly

in the whole Hudson Bay watershed area, an immense territory named Rupert's Land

, with Rupert appointed the first Governor. Rupert's first company secretary was Sir James Hayes

and Radisson named the Hayes River

, in present-day Manitoba

, in his honour. The company continued to prosper, forming the basis for much of the commercial activity of colonial Canada. Rupert's role in colonial commerce was marked by his being asked to lay the cornerstone of the new Royal Exchange in 1670, and being made one of its first councillors.

After Rupert's retirement from active seafaring in around 1674, he was able to spend more time engaged in scientific research and became credited with many inventions and discoveries, although some subsequently turned out to be the innovative introduction of European inventions into England. Rupert converted some of the apartments at Windsor Castle

After Rupert's retirement from active seafaring in around 1674, he was able to spend more time engaged in scientific research and became credited with many inventions and discoveries, although some subsequently turned out to be the innovative introduction of European inventions into England. Rupert converted some of the apartments at Windsor Castle

to a luxury laboratory, complete with forge

s, instruments

and raw materials, from where he conducted a range of experiments.

Prince Rupert had already become the third founding member of the scientific Royal Society

, being referred to by contemporaries as a "philosophic warrior", and guided the Society as a Councillor during its early years. Very early on in the Society's history, Rupert demonstrated Prince Rupert's Drop

to King Charles II and the Society, glass teardrops which explode when the tail is cracked; although credited with their invention at the time, later interpretations suggest that he was instead responsible for the introduction of an existing European discovery into England. He demonstrated a new device for lifting water at the Royal Society, and received attention for his process for "painting colours on marble, which, when polished, became permanent". During this time, Rupert also formulated a mathematical question concerning the paradox that a cube can pass through a slightly smaller cube; Rupert questioned how large a cube had to be in order to fit. The question of Prince Rupert's cube

was first solved by the Dutch mathematician Pieter Nieuwland. Rupert was also known for his success in breaking cypher

codes.

Many of Rupert's inventions were military. After designing the Rupertinoe

naval gun, Rupert erected a water-mill on Hackney Marshes for a revolutionary method of boring guns, however his secret died with him, and the enterprise failed. Rupert enjoyed other military problems, and took to manufacturing gun locks

; he devised both a gun that fired multiple rounds

at high speed, and a "handgun

with rotating barrels". He is credited with the invention of a form of gunpowder

, which when demonstrated to the Royal Society in 1663 had a force of over ten times that of regular powder; a better method for using gunpowder in mining

; and a torpedo

. He also developed a form of grapeshot

for use by artillery

. Rupert also focussed on naval inventions: he devised a balancing mechanism to allow improved quadrant

measurements at sea, and produced a diving engine

for retrieving objects on the ocean floor. While recovering from his trepanning treatment Rupert set about inventing new surgical equipment to improve future operations.

Other parts of Rupert's scientific work lay in the field of metallurgy

. Rupert invented a new brass

alloy, slightly darker in hue than regular brass involving three parts of copper to one part of zinc, combined with charcoal; this became known as "Prince's metal" in his honour – sometimes also referred to as "Bristol Brass". Rupert invented the alloy in order to improve naval artillery, but it also became used as a replacement for gold in decorations. Prince Rupert was also credited with having devised an exceptional method for tempering

kirby fish hooks, and for casting

objects into an appearance of perspective

. He also invented an improved method for manufacturing shot

of varying sizes in 1663, that was later retained by the scientist Robert Hooke

, one of Rupert's Royal Society friends during the period.

actress named Peg Hughes

. Rupert became involved with her during the late 1660s, leaving his previous mistress, Frances Bard, although Hughes appears to have held out reciprocating his attentions with the aim of negotiating a suitable settlement. Hughes rapidly received advancement through his patronage; she became a member of the King's Company by 1669, giving her status and immunity from arrest for debt, and was painted four times by Sir Peter Lely

, the foremost court artist of the day.

Despite being encouraged to do so, Rupert did not marry Hughes, but acknowledged their daughter, Ruperta (later Howe), born in 1673. Hughes lived an expensive lifestyle during the 1670s, enjoying gambling and jewels; Rupert gave her at least £20,000 worth of jewellery during their relationship, including several items from the Palatinate royal collection. Margaret continued to act even after Ruperta's birth, returning to the stage in 1676 with the prestigious Duke's Company at the Dorset Garden Theatre

, near the Strand in London. The next year Rupert established Hughes with a "grand building" worth £25,000 that he bought in Hammersmith from Sir Nicholas Crispe. Rupert seems to have rather enjoyed the family lifestyle, commenting that his young daughter "already rules the whole house and sometimes argues with her mother, which makes us all laugh."

, on 29 November 1682 after a bout of pleurisy

, and was buried in the crypt

of Westminster Abbey

on 6 December after a state funeral

. Rupert left most of his estate, worth some £12,000, equally to Hughes and Ruperta. Hughes had an "uncomfortable widowhood" without Rupert's support, allegedly not helped by her unproductive gambling. Presents from Rupert such as Elizabeth of Bohemia

's earrings were sold to the Duchess of Marlborough

, while a pearl necklace given by Rupert's father

to Elizabeth

was sold to fellow actress Nell Gwynn. Hughes sold the house in Hammersmith

to the Margrave of Brandenburg—it ultimately became known as Brandenburg House. Ruperta ultimately married Emanuel Scrope Howe

, future MP and English general, and had five children, Sophia, William, Emanuel, James and Henrietta. Rupert's son, Dudley Bard, became a military officer, frequently known as "Captain Rupert", and died fighting at the Siege of Budapest

while in his late teens.

The towns of Prince Rupert, British Columbia

, Prince Rupert, Edmonton

and the Rupert River

in Quebec

are all named after the Prince. A British forces secondary school in Germany, Prince Rupert School, bears his name, it teaches both children from armed forces families and fee-paying English-speaking children. In Bristol

there was also a street, Rupert Street and formerly a public house, The Prince Rupert in Rupert Street named to commemorate Prince Rupert.

|-

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, founded in 1348, is the highest order of chivalry, or knighthood, existing in England. The order is dedicated to the image and arms of St...

, FRS

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

(17 December 1619 – 29 November 1682) was a noted soldier, admiral, scientist, sportsman, colonial governor and amateur artist during the 17th century. Rupert was a younger son of the German prince Frederick V, Elector Palatine

Frederick V, Elector Palatine

Frederick V was Elector Palatine , and, as Frederick I , King of Bohemia ....

and his wife Elizabeth

Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth of Bohemia was the eldest daughter of King James VI and I, King of Scotland, England, Ireland, and Anne of Denmark. As the wife of Frederick V, Elector Palatine, she was Electress Palatine and briefly Queen of Bohemia...

, the eldest daughter of James I of England

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

. Thus Rupert was the nephew of King Charles I of England

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, who created him Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British Royal Family, named after the county of Cumberland.-History:...

and Earl of Holderness

Earl of Holderness

The title Earl of Holderness was created on three occasions in the Peerage of England.The first creation, in 1621, along with the subsidiary title Baron Kingston-upon-Thames, of Kingston-upon-Thames in the County of Surrey, was in favour of John Ramsay, 1st Viscount of Haddington...

, and the first cousin of King Charles II of England

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

. His sister Electress Sophia was the mother of George I of Great Britain

George I of Great Britain

George I was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 until his death, and ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg in the Holy Roman Empire from 1698....

.

Prince Rupert had a varied career. He was a soldier from a young age, fighting against Spain

Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to the history of Spain over the 16th and 17th centuries , when Spain was ruled by the major branch of the Habsburg dynasty...

in the Netherlands

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

during the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648), and against the Holy Roman Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

in Germany during the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

(1618–48). Aged 23, he was appointed commander of the Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

during the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, becoming the archetypal Cavalier

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

of the war and ultimately the senior Royalist general. He surrendered after the fall of Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

and was banished from England. He served under Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

against Spain, and then as a Royalist privateer

Privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship authorized by a government by letters of marque to attack foreign shipping during wartime. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without having to spend public money or commit naval officers...

in the Caribbean. Following the Restoration, Rupert returned to England, becoming a senior British naval commander during the Second

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo–Dutch War was part of a series of four Anglo–Dutch Wars fought between the English and the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries for control over the seas and trade routes....

and Third

Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo–Dutch War or Third Dutch War was a military conflict between England and the Dutch Republic lasting from 1672 to 1674. It was part of the larger Franco-Dutch War...

Anglo-Dutch wars

Anglo-Dutch Wars

The Anglo–Dutch Wars were a series of wars fought between the English and the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries for control over the seas and trade routes. The first war took place during the English Interregnum, and was fought between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic...

, engaging in scientific invention, art, and serving as the first Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company , abbreviated HBC, or "The Bay" is the oldest commercial corporation in North America and one of the oldest in the world. A fur trading business for much of its existence, today Hudson's Bay Company owns and operates retail stores throughout Canada...

. Prince Rupert died in England in 1682, aged 62.

Rupert is considered to have been a quick-thinking and energetic cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

general, but ultimately undermined by his youthful impatience in dealing with his peers during the Civil War. In the Interregnum, Rupert continued the conflict against Parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

by sea from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean, showing considerable persistence in the face of adversity. As the head of the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

in his later years, he showed greater maturity and made impressive and long-lasting contributions to the Royal Navy's doctrine

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

and development. As a colonial governor, Rupert shaped the political geography of modern Canada (Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land, or Prince Rupert's Land, was a territory in British North America, consisting of the Hudson Bay drainage basin that was nominally owned by the Hudson's Bay Company for 200 years from 1670 to 1870, although numerous aboriginal groups lived in the same territory and disputed the...

was named in his honour) and played a role in the early African slave trade

African slave trade

Systems of servitude and slavery were common in many parts of Africa, as they were in much of the ancient world. In some African societies, the enslaved people were also indentured servants and fully integrated; in others, they were treated much worse...

. Rupert's varied and numerous scientific and administrative interests combined with his considerable artistic skills made him one of the more colourful individuals of the Restoration period.

Early life and exile

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

in 1619, at the time of the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

, to Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart

Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth of Bohemia was the eldest daughter of King James VI and I, King of Scotland, England, Ireland, and Anne of Denmark. As the wife of Frederick V, Elector Palatine, she was Electress Palatine and briefly Queen of Bohemia...

. He was declared a prince by the principality of Lusatia

Lusatia

Lusatia is a historical region in Central Europe. It stretches from the Bóbr and Kwisa rivers in the east to the Elbe valley in the west, today located within the German states of Saxony and Brandenburg as well as in the Lower Silesian and Lubusz voivodeships of western Poland...

. Rupert's father, Frederick V

Frederick V, Elector Palatine

Frederick V was Elector Palatine , and, as Frederick I , King of Bohemia ....

, as ruler of the Palatinate, was a leading member of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

, the head of the Protestant Union

Protestant Union

The Protestant Union or Evangelical Union was a coalition of Protestant German states that was formed in 1608 to defend the rights, lands and person of each member....

, with a martial family tradition stretching back several centuries. His family was also at the heart of the network of Protestant rulers across the north of Europe at the time. Frederick enjoyed close ties through his mother to the ruling House of Orange-Nassau

House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau , a branch of the European House of Nassau, has played a central role in the political life of the Netherlands — and at times in Europe — since William I of Orange organized the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule, which after the Eighty Years' War...

in the United Provinces

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

. Elizabeth was a daughter of King James I of England

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

and sister of King Charles I of England

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, and related in turn to the Danish royal family. The family enjoyed an extremely wealthy lifestyle in Heidelberg

Heidelberg

-Early history:Between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago, "Heidelberg Man" died at nearby Mauer. His jaw bone was discovered in 1907; with scientific dating, his remains were determined to be the earliest evidence of human life in Europe. In the 5th century BC, a Celtic fortress of refuge and place of...

, enjoying the famous palace gardens—the Hortus Palatinus

Hortus Palatinus

The Hortus Palatinus, or Garden of the Palatinate, was a Baroque garden in the Italian Renaissance style attached to Heidelberg Castle, Germany. The garden was commissioned by Frederick V, Elector Palatine in 1614 for his new wife, Elizabeth Stuart, and became famous across Europe during the 17th...

, designed by Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones is the first significant British architect of the modern period, and the first to bring Italianate Renaissance architecture to England...

and Salomon de Caus

Salomon de Caus

Salomon de Caus was a French engineer and once credited with the development of the steam engine.Salomon was the elder brother of Isaac de Caus. Being a Huguenot, he spent his life moving across Europe....

—and a lavish castle with one of the best libraries in Europe.

Frederick had allied himself with rebellious Protestant Bohemian

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia was a country located in the region of Bohemia in Central Europe, most of whose territory is currently located in the modern-day Czech Republic. The King was Elector of Holy Roman Empire until its dissolution in 1806, whereupon it became part of the Austrian Empire, and...

nobility in 1619, expecting support from the Protestant Union in his revolt against the Catholic Ferdinand II

Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand II , a member of the House of Habsburg, was Holy Roman Emperor , King of Bohemia , and King of Hungary . His rule coincided with the Thirty Years' War.- Life :...

, the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor. This support was not forthcoming, resulting in a crushing defeat at the hands of his Catholic enemies at the Battle of White Mountain

Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain, 8 November 1620 was an early battle in the Thirty Years' War in which an army of 30,000 Bohemians and mercenaries under Christian of Anhalt were routed by 27,000 men of the combined armies of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor under Charles Bonaventure de Longueval,...

. With Frederick now outlawed the family fled from Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

to the Netherlands

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

, where Rupert spent his childhood. Rupert's parents were mockingly termed the "Winter King and Queen" as a consequence of their reigns in Bohemia having lasted only a single season.

Rupert was almost left behind in the court's rush to escape Ferdinand's advance on Prague, until Christopher Dhona, a court member, tossed the prince into a carriage at the last moment. Rupert accompanied his parents to The Hague

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

, where he spent his early years at the Hof te Wassenaer. Rupert's mother paid her children little attention even by the standards of the day, apparently preferring her pet monkeys and dogs. Instead, Frederick employed Monsieur and Madame de Plessen to act as governors to his children, with instructions to inculcate a positive attitude towards the Bohemians and the English, and to bring them up as strict Calvinists

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...

. The result was a strict school routine including logic

Logic

In philosophy, Logic is the formal systematic study of the principles of valid inference and correct reasoning. Logic is used in most intellectual activities, but is studied primarily in the disciplines of philosophy, mathematics, semantics, and computer science...

, mathematics, writing, drawing, singing and playing instruments. As a child, Rupert was at times badly behaved, 'fiery, mischievous, and passionate' and earned himself the nickname Robert le Diable, or "Rupert The Devil". Nonetheless, Rupert proved to be an able student. By the age of 3 he could speak some English, Czech and French, and mastered German while still young, but had little interest in Latin and Greek. He excelled in art, being taught by Gerard van Honthorst

Gerard van Honthorst

Gerard van Honthorst , also known as Gerrit van Honthorst and in Italy as Gherardo delle Notti for his nighttime candlelit subjects, was a Dutch Golden Age painter from Utrecht.-Biography:...

, and found the maths and sciences easy. By the time he was 18 he stood about 6 ft 4 in tall and had become a dashing young prince.

Rupert's family continued their attempts to regain the Palatinate during their time in The Hague. Money was short, with the family relying upon a relatively small pension from The Hague, the proceeds from family investments in Dutch raids on Spanish shipping, and revenue from pawned family jewellery. By 1625, however, Frederick had convinced an alliance of nations—including England, France and Sweden—to support his attempts to regain the Palatinate and Bohemia. By the early 1630s this appeared closer than ever. Rupert's father, Frederick, had increasingly invested in relationship with the Swedish King Gustavus

Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustav II Adolf has been widely known in English by his Latinized name Gustavus Adolphus Magnus and variously in historical writings also as Gustavus, or Gustavus the Great, or Gustav Adolph the Great,...

, now the dominant religious leader in Germany. In 1632, however, the two men disagreed over Gustavus' insistence that Frederick provide equal rights to his Lutheran and Calvinist subjects after regaining his lands; Frederick refused and started to return to The Hague. He died of a fever along the way and was buried in an unmarked grave. Rupert had lost his father at the age of 13, and Gustavus' death at the battle of Lützen

Battle of Lützen (1632)

The Battle of Lützen was one of the most decisive battles of the Thirty Years' War. It was a Protestant victory, but cost the life of one of the most important leaders of the Protestant alliance, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, which caused the Protestant campaign to lose direction.- Prelude to the...

in the same month deprived the family of a critical Protestant ally. With Frederick gone, King Charles proposed that the family move to England; Rupert's mother declined, but asked that Charles extend his protection to her remaining children instead.

Teenage years

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

and his uncle King Charles I, before being captured and imprisoned in Linz

Linz

Linz is the third-largest city of Austria and capital of the state of Upper Austria . It is located in the north centre of Austria, approximately south of the Czech border, on both sides of the river Danube. The population of the city is , and that of the Greater Linz conurbation is about...

during the middle stages of the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

. Rupert had become a soldier early; at the age of 14 he attended the Dutch pas d'armes

Pas d'Armes

The pas d'armes or passage of arms was a type of chivalric hastilude that evolved in the late 14th century and remained popular through the 15th century...

with the Protestant Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange

Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange

Frederick Henry, or Frederik Hendrik in Dutch , was the sovereign Prince of Orange and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel from 1625 to 1647.-Early life:...

, later that year he fought alongside him at the siege of Rheinberg

Rheinberg

Rheinberg is a town in the district of Wesel, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is situated on the left bank of the Rhine, approx. north of Moers and south of Wesel....

, and by 1635 he was acting as a military lifeguard

Bodyguard

A bodyguard is a type of security operative or government agent who protects a person—usually a famous, wealthy, or politically important figure—from assault, kidnapping, assassination, stalking, loss of confidential information, terrorist attack or other threats.Most important public figures such...

to Prince Frederick. Rupert went on to fight against imperial Spain in the successful campaign around Breda

Siege of Breda (1637)

The Fourth Siege of Breda was an important siege in the Eighty Years' War in which stadtholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange retook the city of Breda, which had last changed hands in 1625 when the Spanish general Ambrogio Spinola conquered it for Spain...

in 1637 during the Eighty Years' War in the Netherlands. By the end of this period, Rupert had acquired a reputation for fearlessness in battle, high spirits and considerable industry.

In between these campaigns Rupert had visited his uncle's court in England. The Palatinate cause was a popular Protestant issue in England, and in 1637 a general public subscription helped fund an expedition under Charles Louis

Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine

Charles Louis, , Elector Palatine KG was the second son of Frederick V of the Palatinate, the "Winter King" of Bohemia, and his wife, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King James I of England ....

to try and regain the electorate as part of a joint French campaign. Rupert was placed in command of a Palatinate cavalry regiment, and his later friend Lord Craven, an admirer of Rupert's mother, assisted in raising funds and accompanied the army on the campaign. The campaign ended badly at the Battle of Vlotho

Battle of Vlotho

The Battle of Vlotho was the culmination of an attempt by Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine to launch a campaign with the aim of recapturing the Rhenish Palatinate. Charles Louis' defeat marked the last time either Palatine or English forces played an important role in the Thirty Years'...

(17 October 1638) during the invasion of Westphalia

Westphalia

Westphalia is a region in Germany, centred on the cities of Arnsberg, Bielefeld, Dortmund, Minden and Münster.Westphalia is roughly the region between the rivers Rhine and Weser, located north and south of the Ruhr River. No exact definition of borders can be given, because the name "Westphalia"...

; Rupert escaped death, but was captured by the forces of the Imperial General Melchior von Hartzfeld towards the end of the battle.

After a failed attempt to bribe his way free of his guards, Rupert was imprisoned in Linz

Linz

Linz is the third-largest city of Austria and capital of the state of Upper Austria . It is located in the north centre of Austria, approximately south of the Czech border, on both sides of the river Danube. The population of the city is , and that of the Greater Linz conurbation is about...

. Lord Craven, also taken in the battle, attempted to persuade his captors to allow him to remain with Rupert, but was refused. Rupert's imprisonment was surrounded by religious overtones. His mother was deeply concerned that he might be converted from Calvinism

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...