History of West Virginia

Encyclopedia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

is one of two American states

U.S. state

A U.S. state is any one of the 50 federated states of the United States of America that share sovereignty with the federal government. Because of this shared sovereignty, an American is a citizen both of the federal entity and of his or her state of domicile. Four states use the official title of...

formed during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

(1861–1865), along with Nevada

Nevada

Nevada is a state in the western, mountain west, and southwestern regions of the United States. With an area of and a population of about 2.7 million, it is the 7th-largest and 35th-most populous state. Over two-thirds of Nevada's people live in the Las Vegas metropolitan area, which contains its...

, and is the only state to form by seceding from a Confederate state. It was originally part of the British Virginia Colony (1607–1776) and the western part of the state of Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

(1776–1863), whose population became sharply divided over the issue of secession from the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

and in the separation from Virginia, formalized by admittance to the Union as a new state in 1863. West Virginia was one of the Civil War Border states

Border states (Civil War)

In the context of the American Civil War, the border states were slave states that did not declare their secession from the United States before April 1861...

.

West Virginia's history was profoundly affected by its mountainous terrain, spectacular river valleys, and rich natural resources. These were all factors driving its economy and the lifestyles of residents, as well as drawing visitors to the "Mountain State" in the early 21st century.

Prehistory

The area now known as West Virginia was a favorite hunting ground of numerous Native AmericanNative Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

peoples before the arrival of European

European ethnic groups

The ethnic groups in Europe are the various ethnic groups that reside in the nations of Europe. European ethnology is the field of anthropology focusing on Europe....

settlers. Many ancient man-made earthen mounds from various mound builder cultures survive, especially in the areas of Moundsville

Moundsville, West Virginia

Moundsville is a city in Marshall County, West Virginia, along the Ohio River. It is part of the Wheeling Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 9,998 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Marshall County. The city was named for the Grave Creek Mound. Moundsville was settled in...

, South Charleston

South Charleston, West Virginia

South Charleston is a city in Kanawha County, West Virginia, U.S. The population was 13,450 at the 2010 census. South Charleston was established in 1906, but not incorporated until 1919 by special charter enacted by the West Virginia Legislature...

, and Romney

Romney, West Virginia

Romney is a city in and the county seat of Hampshire County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 1,940 at the 2000 census, while the area covered by the city's ZIP code had a population of 5,873. It is a city with a very historic background dating back to the 18th century...

. The artifacts uncovered in these give evidence of a village society having a tribal trade system culture that practiced limited cold worked

Work hardening

Work hardening, also known as strain hardening or cold working, is the strengthening of a metal by plastic deformation. This strengthening occurs because of dislocation movements within the crystal structure of the material. Any material with a reasonably high melting point such as metals and...

copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

. As of 2009, over 12,500 archaeological sites have been documented in West Virginia (Bryan Ward 2009:10).

Paleo-Indian culture appears by 10,500 BC in West Virginia passing along the major river valleys and ridge-line gap watersheds. Following are the traditional Archaic sub-periods; Early (8000-6000 BC), Middle (6000-4000 BC), and Late (4000-1000 BC), (Kerr, 2010). Within the greater region of and neighboring the Mountain State, the Riverton Tradition includes: Maple Creek Phase. Also are the Buffalo Phase, Transitional Archaic Phase, Transitional Period Culture and Central Ohio Valley Archaic Phase. Also within the region, the Laurention Archaic Tradition which includes: Brewerton Phase, Feheeley Phase, Dunlop Phase, McKibben Phase, Genesee Phase, Stringtown/Satchel Phase, Satchel Phase and Lamoka/Dustin Phase.

The Adena

Adena

Adena can mean:*Adena, Ohio, USA*Adena, Colorado, USA*The Adena culture, a Mound-building Native American culture.*The Adena Mansion, Thomas Worthington's home and estate in Chillicothe, Ohio...

provided the greatest cultural influence in the state. For practical purposes, the Adena is Early Woodland period

Woodland period

The Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures was from roughly 1000 BCE to 1000 CE in the eastern part of North America. The term "Woodland Period" was introduced in the 1930s as a generic header for prehistoric sites falling between the Archaic hunter-gatherers and the...

according to West Virginia University

West Virginia University

West Virginia University is a public research university in Morgantown, West Virginia, USA. Other campuses include: West Virginia University at Parkersburg in Parkersburg; West Virginia University Institute of Technology in Montgomery; Potomac State College of West Virginia University in Keyser;...

's Dr. Edward V. McMichael (1968:16), also among the 1963 Geological Survey

Geological survey

The term geological survey can be used to describe both the conduct of a survey for geological purposes and an institution holding geological information....

. Middle and Late Woodland people include: Middle Woodland Watson pottery people, Late Woodland Wood Phase, Late Hopewell at Romney, Montaine (late Woodland AD 500-1000), Wilhelm culture (Late Middle Woodland, c. AD 1~500), Armstrong (Late Middle Woodland, c. AD 1~500), Buck Garden (Late Woodland AD500-1200), Childers Phase (Late Middle Woodland c. 400 AD) followed by Parkline phase (Late Woodland AD 750~1000). Adena villages can be characterized as rather large compared to Late Prehistoric tribes.

The Adena Indians used ceremonial pipes that were exceptional works of art. They lived in round shaped (double post method) wicker sided and bark sheet roofed houses (McMichael 1968:21). Little is known about the housing of Paleo-Indian and Archaic periods, but Woodland Indians lived in wigwams. They grew sunflowers, tubers, gourds, squash and several seeds such as lambsquarter, may grass, sumpweed, smartweed and little barley cereal

Cereal

Cereals are grasses cultivated for the edible components of their grain , composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran...

s. In the Fort Ancient period, Indians lived in much larger poled rectanglar shaped houses with walls hide covered (McMichael 1968:38). They were farmers who cultivated large fields around their villages, concentrating on corn

Corn

Corn is the name used in the United States, Canada, and Australia for the grain maize.In much of the English-speaking world, the term "corn" is a generic term for cereal crops, such as* Barley* Oats* Wheat* Rye- Places :...

, bean

Bean

Bean is a common name for large plant seeds of several genera of the family Fabaceae used for human food or animal feed....

s, tuber

Tuber

Tubers are various types of modified plant structures that are enlarged to store nutrients. They are used by plants to survive the winter or dry months and provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growing season and they are a means of asexual reproduction...

s, sunflower

Sunflower

Sunflower is an annual plant native to the Americas. It possesses a large inflorescence . The sunflower got its name from its huge, fiery blooms, whose shape and image is often used to depict the sun. The sunflower has a rough, hairy stem, broad, coarsely toothed, rough leaves and circular heads...

s, gourd

Gourd

A gourd is a plant of the family Cucurbitaceae. Gourd is occasionally used to describe crops like cucumbers, squash, luffas, and melons. The term 'gourd' however, can more specifically, refer to the plants of the two Cucurbitaceae genera Lagenaria and Cucurbita or also to their hollow dried out shell...

s and many types of squash including the pumpkin

Pumpkin

A pumpkin is a gourd-like squash of the genus Cucurbita and the family Cucurbitaceae . It commonly refers to cultivars of any one of the species Cucurbita pepo, Cucurbita mixta, Cucurbita maxima, and Cucurbita moschata, and is native to North America...

. They also raised domestic turkeys and kept dogs as pets. Their neighbors in the northerly of the state, the Monongahelan houses were generally circular in shape often with nook or storage appendage. Their living characteristics were more of a heritage from the Woodland Indians (McMichael 1968:49).

The Late Prehistoric (ADE 950~1650) phases of the Fort Ancient Tradition include: Feurt Phase, Blennerhassett Phase, Bluestone Phase, Clover Complex followed by the Orchard Phase (ADE 1550~1650) with a Late Proto-historic arrival of a Lizard Cult from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture that coincided with their adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom-level complex social organization from...

. Contemporaneously to Fort Ancient Tradition southerly of the state, the sister culture called Monongahela is found on the northerly of the Mountain State stemming from the Drew Tradition. Early historic tribes living within or routinely hunting and trading within the state include: Calicuas later mixed in colonial north-western Virginia-Pennsylvania at the time as popular termed Cherokee, Mohetans, Rickohockans from ancient Nation du Chat area, Monetons and Monecaga or Monacan, Tomahitans or Yuchi-Occaneechi, Tuscarora or mixed broad termed Mingoe & Canawagh or Kanawhas (Chiroenhaka, Mooney 1894:7-8), Oniasantkeronons or Tramontane of the proto-historic southerly Neutral Nation trade empire (element Nation du Chat), Shattera or Tutelo, Ouabano or Mohican-Delaware, Chaouanon or Shawnee, Cheskepe or Shawnee-Yuchi, Loupe (Captina Island

Captina Island

Captina Island is an island on the Ohio River in Marshall County, West Virginia in the United States. Powhatan Point, Ohio is located on the opposite shore from Captina Island. It lies at the southern end of Round Bottom with a stream-like channel separating the island from the West Virginia shore...

historic mix, Lanape & Powhatan

Powhatan Point, Ohio

Powhatan Point is one of several small villages in Belmont County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River. The population was 1,744 at the 2000 census...

), Tionontatacaga and Little Mingoe (Guyandottes), Massawomeck and later mixed as Mohawk, Susquesahanock or White Minqua later mixed Mingoes and Arrigahaga or Black Minqua of the Nation du Chat and proto-historic Neutral Nation

Neutral Nation

The Neutrals, also known as the Attawandaron, were an Iroquoian nation of North American native people who lived near the shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie.-Territory:...

trade empire.

Within the Mountain State, these tribal villages can be characterized as rather small and scattered as they moved about the old fields every couple of generations. Many would join other tribes and remove to the midwest regions as settlers arrived in the state. Although, there were those who would acculturate within the historic as sometimes called Fireside Cabin culture. Some are early historic documented seeking protection closer, moving to the easterly Colonial trade towns. And later, other small splintered clans were attracted to, among others, James Le Tort, Charles Poke and John Van Metre trading houses within the state. This historic period changed way of living extends from a little before the 18th century Virginia and Pennsylvania region North American fur trade

North American Fur Trade

The North American fur trade was the industry and activities related to the acquisition, exchange, and sale of animal furs in the North American continent. Indigenous peoples of different regions traded among themselves in the Pre-Columbian Era, but Europeans participated in the trade beginning...

beginning on the Eastern Panhandle of the state.

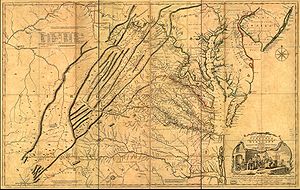

European exploration and settlement

Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood , sometimes referred to as "General" or "Colonel" Wood, was an English fur trader and explorer of 17th century colonial Virginia...

, at the direction of Royal Governor William Berkeley of the Virginia Colony, sent the party of Thomas Batts and Robert Fallum into the West Virginia area. During this expedition the pair followed the New River and discovered Kanawha Falls.

On July 13, 1709, Louis Michel, George Ritter, and Baron Christoph von Graffenried

Christoph von Graffenried

Christoph von Graffenried led a group of Swiss and Palatine Germans to North Carolina in 1705, and later authored Relation of My American Project, an account of the establishment of this colony in the New World....

petitioned the King of England for a land grant in the Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. In many books the town is called "Harper's Ferry" with an apostrophe....

, Shepherdstown

Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located along the Potomac River. It is the oldest town in the state, having been chartered in 1762 by Colonial Virginia's General Assembly. Since 1863, Shepherdstown has been in West Virginia, and is the oldest town in...

area, Jefferson County

Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County is a county located in the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 53,498. Its county seat is Charles Town...

, in order to establish a Swiss colony

Colony

In politics and history, a colony is a territory under the immediate political control of a state. For colonies in antiquity, city-states would often found their own colonies. Some colonies were historically countries, while others were territories without definite statehood from their inception....

. Neither the land grant or the Swiss colony ever materialized.

Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood was a Lieutenant-Colonel in the British Army and a noted Lieutenant Governor of Virginia. He is noted in Virginia and American history for a number of his projects as Governor, including his exploring beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains, his establishing what was perhaps the first...

is sometimes credited with taking his 1716 "Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition

Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition

The Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition took place in 1716 in the British Colony of Virginia. The Royal Governor and a number of prominent citizens traveled westward, across the Blue Ridge Mountains on an exploratory expedition...

" into what is now Pendleton County

Pendleton County, West Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 8,196 people, 3,350 households, and 2,355 families residing in the county. The population density was 12 people per square mile . There were 5,102 housing units at an average density of 7 per square mile...

, although according to contemporary accounts, Spotwood's trail went no farther west than Harrisonburg, Virginia

Harrisonburg, Virginia

Harrisonburg is an independent city in the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia in the United States. Its population as of 2010 is 48,914, and at the 2000 census, 40,468. Harrisonburg is the county seat of Rockingham County and the core city of the Harrisonburg, Virginia Metropolitan Statistical...

. The Treaty of Albany, 1722, designated the Blue Ridge Mountains

Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap. The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southern-most...

as the western boundary of white settlement, and recognized Iroquois

Iroquois

The Iroquois , also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse", are an association of several tribes of indigenous people of North America...

rights on the west side of the ridge, including all of West Virginia. The Iroquois made little effort to settle these parts, but nonetheless claimed them as their hunting ground, as did other tribes, notably the Shawnee

Shawnee

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania...

and Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

. Soon after this, white settlers began moving into the Greater Shenandoah-Potomac Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

making up the entire eastern portion of the State. They found it largely unoccupied, apart from Tuscaroras who had lately moved into the area around Martinsburg, WV, some Shawnee villages in the region around Moorefield, WV and Winchester, VA, and frequent passing bands of "Northern Indians" (Lenape

Lenape

The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the...

from New Jersey) and "Southern Indians" (Catawba

Catawba

Catawba may refer to several things:*Catawba , a Native American tribe*Catawban languages-Botany:*Catalpa, a genus of trees, based on the name used by the Catawba and other Native American tribes*Catawba , a variety of grape...

from South Carolina) who were engaged in a bitter long-distance war, using the Valley as a battleground.

John Van Metre, an Indian trader, penetrated into the northern portion of West Virginia in 1725. Also in 1725, Pearsall's Flats in the South Branch Potomac River valley, present-day Romney

Romney, West Virginia

Romney is a city in and the county seat of Hampshire County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 1,940 at the 2000 census, while the area covered by the city's ZIP code had a population of 5,873. It is a city with a very historic background dating back to the 18th century...

, was settled, and later became the site of the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

stockade, Fort Pearsall

Fort Pearsall

Fort Pearsall was an early frontier fort constructed in 1756 in Romney, West Virginia to protect local settlers in the South Branch Potomac River valley against Native American raids...

. Morgan ap Morgan

Morgan Morgan

Colonel Morgan Morgan is traditionally believed to have founded the first permanent white settlement in present day West Virginia at Cool Spring Farm, and he is credited with founding the first church in what is now West Virginia.-Early life:Little direct evidence of Morgan's early life and...

, a Welshman, built a cabin near present-day Bunker Hill

Bunker Hill, West Virginia

Bunker Hill is an unincorporated town in Berkeley County, West Virginia, United States located on Winchester Pike at its junction with West Virginia Secondary Route 26 south of Martinsburg. It is the site of the confluence of Torytown Run and Mill Creek, a tributary of Opequon Creek...

in Berkeley County

Berkeley County, West Virginia

Berkeley County is a county located in the Eastern Panhandle region of the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population is 104,169, making it the second-most populous county in West Virginia, behind Kanawha...

in 1727. The same year German settlers from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

founded New Mecklenburg, the present Shepherdstown

Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located along the Potomac River. It is the oldest town in the state, having been chartered in 1762 by Colonial Virginia's General Assembly. Since 1863, Shepherdstown has been in West Virginia, and is the oldest town in...

, on the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

, and others soon followed.

Orange County, Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

was formed in 1734. It included all areas west of the Blue Ridge Mountains

Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap. The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southern-most...

, constituting all of present West Virginia. However, in 1736 the Iroquois Six Nations protested Virginia's colonization beyond the demarcated Blue Ridge, and a skirmish was fought in 1743. The Iroquois were on the point of threatening all-out war against the Virginia Colony over the "Cohongoruton lands", which would have been destructive and devastating, when Governor Gooch bought out their claim for 400 pounds at the Treaty of Lancaster

Treaty of Lancaster

The Treaty of Lancaster was a treaty concluded between the Six Nations and the colonies of Virginia and Maryland. Deliberations began at Lancaster, Pennsylvania on June 28, and ended on July 4, 1744....

(1744).

In 1661, King Charles II of England

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

had granted a company of gentlemen the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock

Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length. It traverses the entire northern part of the state, from the Blue Ridge Mountains in the west, across the Piedmont, to the Chesapeake Bay, south of the Potomac River.An important river in American...

rivers, known as the Northern Neck

Northern Neck

The Northern Neck is the northernmost of three peninsulas on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay in the Commonwealth of Virginia. This peninsula is bounded by the Potomac River on the north and the Rappahannock River on the south. It encompasses the following Virginia counties: Lancaster,...

. The grant eventually came into the possession of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron was the son of Thomas Fairfax, 5th Lord Fairfax of Cameron and of Catherine, daughter of Thomas Culpeper, 2nd Baron Culpeper of Thoresway....

and in 1746 a stone

Fairfax Stone

Fairfax Stone Historical Monument State Park is a West Virginia state park commemorating the Fairfax Stone, a surveyor's marker and boundary stone at the source of the North Branch of the Potomac River in West Virginia...

was erected at the source of the North Branch Potomac River to mark the western limit of the grant. A considerable part of this land was surveyed by George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, especially the South Branch Potomac River valley between 1748 and 1751. The diary kept by Washington indicates that there were already many squatters, largely of German origin, along the South Branch. Christopher Gist

Christopher Gist

Christopher Gist was an accomplished American explorer, surveyor and frontiersman. He was one of the first white explorers of the Ohio Country . He is credited with providing the first detailed description of the Ohio Country to Great Britain and her colonists...

, a surveyor for the first Ohio Company

Ohio Company

The Ohio Company, formally known as the Ohio Company of Virginia, was a land speculation company organized for the settlement by Virginians of the Ohio Country and to trade with the Indians there...

, which was composed chiefly of Virginians, explored the country along the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

north of the mouth of the Kanawha River

Kanawha River

The Kanawha River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, it has formed a significant industrial region of the state since the middle of the 19th century.It is formed at the town of Gauley...

in 1751 and 1752. The company sought to have a fourteenth colony established with the name Vandalia

Vandalia (colony)

Vandalia was the name of a proposed British colony in North America . The colony was located south of the Ohio River, primarily in what is now the U.S...

.

Many settlers crossed the mountains after 1750, though they were hindered by Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

resistance. The 1744 Treaty of Lancaster had left ambiguous whether the Iroquois had sold only as far as the Alleghenies, or all their claim south of the Ohio, including the rest of modern West Virginia. In 1752 at the Treaty of Logstown

Logstown

The riverside village of Logstown was a significant Native American settlement in Western Pennsylvania and the site of the 1752 signing of the treaty of friendship between the Ohio Company and the Amerindians occupying the region in the years leading up to the...

, they acknowledged the right of English settlements south of the Ohio, but the Cherokee and Shawnee claims still remained. During the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

(1754–1763), the scattered settlements were almost destroyed. The Proclamation of 1763 again confirmed all land beyond the Alleghenies as Indian Territory, but the Iroqouis finally relinquished their claims south of the Ohio to Britain at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was an important treaty between North American Indians and the British Empire. It was signed in 1768 at Fort Stanwix, located in present-day Rome, New York...

in 1768.

Most of the Cherokee claim within West Virginia, the southwestern part of the state, was sold to Virginia in 1770 by the Treaty of Lochaber

Treaty of Lochaber

The Treaty of Lochaber was signed on October 18, 1770 by British representative John Stuart and the Cherokees. Based on the terms of the accord, the Cherokee relinquished all claims to property from the North Carolina and Virginia border to a point near Long Island on the Holston River to the mouth...

. In 1774, the Crown Governor of Virginia, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore was a British peer and colonial governor. He was the son of William Murray, 3rd Earl of Dunmore, and his wife Catherine . He is best remembered as the last royal governor of the Colony of Virginia.John was the eldest son of William and Catherine Murray, and nephew...

, led a force over the mountains, and a body of militia under Colonel Andrew Lewis dealt the Shawnee Indians under Cornstalk

Cornstalk

Cornstalk was a prominent leader of the Shawnee nation just prior to the American Revolution. His name, Hokoleskwa, translates loosely into "stalk of corn" in English, and is spelled Colesqua in some accounts...

a crushing blow at the junction of the Kanawha and Ohio rivers, in the Battle of Point Pleasant

Battle of Point Pleasant

The Battle of Point Pleasant, known as the Battle of Kanawha in some older accounts, was the only major battle of Dunmore's War. It was fought on October 10, 1774, primarily between Virginia militia and American Indians from the Shawnee and Mingo tribes...

. Following this conflict, known as Dunmore's War

Dunmore's War

Dunmore's War was a war in 1774 between the Colony of Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo American Indian nations....

, the Shawnee and Mingo

Mingo

The Mingo are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans made up of peoples who migrated west to the Ohio Country in the mid-eighteenth century. Anglo-Americans called these migrants mingos, a corruption of mingwe, an Eastern Algonquian name for Iroquoian-language groups in general. Mingos have also...

ceded their rights south of the Ohio, that is, to West Virginia and Kentucky. But renegade Cherokee chief Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe

Tsiyu Gansini , "He is dragging his canoe", known to whites as Dragging Canoe, was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee against colonists and United States settlers...

continued to dispute the settlers' advance, fighting the Chickamauga Wars (1776-1794) until after the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. During the war, the settlers in Western Virginia were generally active Whigs and many served in the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

.

Early River traffic

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

.

October, 1748, the Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

passed an act establishing a ferry across the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

from the landing of Evan Watkin near the mouth of Conococheague Creek

Conococheague Creek

Conococheague Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River, is a free-flowing stream that originates in Pennsylvania and empties into the Potomac River near Williamsport, Maryland. It is in length, with in Pennsylvania and in Maryland...

in present-day Berkeley County

Berkeley County, West Virginia

Berkeley County is a county located in the Eastern Panhandle region of the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population is 104,169, making it the second-most populous county in West Virginia, behind Kanawha...

to the property of Edmund Wade in Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

. Robert Harper obtained a permit

Permit

Permit may refer to:*Permit *Various legal licenses:*License*Work permit*Learner's permit*Permit to travel*Construction permit*Home Return Permit*One-way Permit*Permit is the common name for the Trachinotus falcatus, a type of Pompano....

to operate a ferry

Ferry

A ferry is a form of transportation, usually a boat, but sometimes a ship, used to carry primarily passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo as well, across a body of water. Most ferries operate on regular, frequent, return services...

across the Shenandoah River

Shenandoah River

The Shenandoah River is a tributary of the Potomac River, long with two forks approximately long each, in the U.S. states of Virginia and West Virginia...

at present-day Harpers Ferry, Jefferson County on March of 1761. Thus, these two ferry crossings became the earliest locations of government authorized civilian commercial crafts on what would become a part of the West Virginia Waterways.

Satisfying eastern tanneries' growing demand for beaver

Beaver

The beaver is a primarily nocturnal, large, semi-aquatic rodent. Castor includes two extant species, North American Beaver and Eurasian Beaver . Beavers are known for building dams, canals, and lodges . They are the second-largest rodent in the world...

more often came to the 'Point' by canoe

Canoe

A canoe or Canadian canoe is a small narrow boat, typically human-powered, though it may also be powered by sails or small electric or gas motors. Canoes are usually pointed at both bow and stern and are normally open on top, but can be decked over A canoe (North American English) or Canadian...

and raft

Raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is the most basic of boat design, characterized by the absence of a hull...

from the Kanawha region's tributary creeks. Isaac Vanbibber and Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone was an American pioneer, explorer, and frontiersman whose frontier exploits mad']'e him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. Boone is most famous for his exploration and settlement of what is now the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which was then beyond the western borders of...

trading post

Trading post

A trading post was a place or establishment in historic Northern America where the trading of goods took place. The preferred travel route to a trading post or between trading posts, was known as a trade route....

was established about 1790 at the mouth of Crooked Creek at Point Pleasant, West Virginia

Point Pleasant, West Virginia

Point Pleasant is a city in Mason County, West Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha rivers. The population was 4,637 at the 2000 census...

. Hudson's Trade Post and early landing appears on the 1807 Madison map opposite St Albans. By this decade, the steel trap increases efficiency as beaver becomes scarce within two decades. A shift to the state's other natural resources begins in ever increasing export quantity. Kanawha Harbor had a great amount of freight and passenger lay-over after the Old War of the 1790s. Kanawha salt

Salt

In chemistry, salts are ionic compounds that result from the neutralization reaction of an acid and a base. They are composed of cations and anions so that the product is electrically neutral...

production followed by coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

and timber

Timber

Timber may refer to:* Timber, a term common in the United Kingdom and Australia for wood materials * Timber, Oregon, an unincorporated community in the U.S...

floats were moved from West Virginia streams to the populace of other regions. A number of river side locations were used for early Industrial Revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

keelboat

Keelboat

Keelboat has two distinct meanings related to two different types of boats: one a riverine cargo-capable working boat, and the other a classification for small- to mid-sized recreational sailing yachts.-Historical keel-boats:...

building in the Kanawha region. Among others are at Leon, Ravenswood Murraysville and Little Kanawha River. Earlier 19th century steamboat building and machine repair were located at Wheeling and Parkersburg followed by Point Pleasant and Mason City. Wooden coal barges were built on the Monongahela River near Morgantown, Coal River

Coal River (West Virginia)

The Coal River is a tributary of the Kanawha River in southern West Virginia. It is formed near the community of Alum Creek by the confluence of the Big and Little Coal Rivers, and flows generally northward through western Kanawha County, past the community of Upper Falls and into the Kanawha...

and some at Elk River

Elk River (West Virginia)

The Elk River is a tributary of the Kanawha River, long, in central West Virginia in the United States. Via the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers, it is part of the watershed of the Mississippi River.-Course:...

near Charleston before metal barge

Barge

A barge is a flat-bottomed boat, built mainly for river and canal transport of heavy goods. Some barges are not self-propelled and need to be towed by tugboats or pushed by towboats...

became the trend. To example as how local water works progressed, Kanawha Harbor's boat building increased after a horse drawn logging "tram" with special block & tackle for the hill-side harvesting was brought into use and some expansion of Crooked Creek such as the wooden Barrel Works plant at the creek's mouth. Later, this tram and other steam machinery were used for collecting timber to be used as railroad ties in the railway construction along the Kanawha river. It was finished about 1880. This brought the small steamboat landings of the farmers along the rivers to use the railway. Many railroading spurs were built throughout West Virginia connecting mines to the river boat's barge and coal-tipples.

Trans-Allegheny Virginia, 1776-1861

Social conditions in western Virginia were entirely unlike those existing in the eastern portion of the state. The population was not homogeneous, as a considerable part of the immigration came by way of Pennsylvania and included Germans, Protestant Ulster-ScotsUlster-Scots

The Ulster Scots are an ethnic group in Ireland, descended from Lowland Scots and English from the border of those two countries, many from the "Border Reivers" culture...

, and settlers from the states farther north. During the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, the movement to create a state beyond the Alleghanies was revived and, in 1776, a petition for the establishment of "Westsylvania" was presented to Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

, on the grounds that the mountains made an almost impassable barrier on the east. The rugged nature of the country made slavery unprofitable, and time only increased the social, political and economic differences between the two sections of Virginia.

The convention which met in 1829 to form a new constitution for Virginia, against the protest of the counties beyond the mountains, required a property qualification for suffrage

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

, and gave the slave-holding counties the benefit of three-fifths of their slave population in apportioning the state's representation in the lower Federal house. As a result, every county beyond the Alleghanies except one voted to reject the constitution, which was nevertheless carried by eastern votes. Though the Virginia constitution of 1850 provided for white manhood suffrage, the distribution of representation among the counties was such as to give control to the section east of the Blue Ridge Mountains

Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap. The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southern-most...

. Another grievance of the West was the large expenditure for internal improvements at state expense by the Virginia Board of Public Works

Virginia Board of Public Works

The Virginia Board of Public Works was a governmental agency which oversaw and helped finance the development of Virginia's internal transportation improvements during the 19th century. In that era, it was customary to invest public funds in private companies, which were the forerunners of the...

in the East compared with the scanty proportion allotted to the West.

For the western areas, problems included the distance from the state seat of government in Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

and the difference of common economic interests resultant from the tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

and food crops farming, fishing, and coastal shipping to the east of the Eastern Continental Divide

Eastern Continental Divide

The Eastern Continental Divide, in conjunction with other continental divides of North America, demarcates two watersheds of the Atlantic Ocean: the Gulf of Mexico watershed and the Atlantic Seaboard watershed. Prior to 1760, the divide represented the boundary between British and French colonial...

(waters which drain to the Atlantic Ocean) along the Allegheny Mountains

Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range , also spelled Alleghany, Allegany and, informally, the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the eastern United States and Canada...

, and the interests of the western portion which drained to the Ohio

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

and Mississippi

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

rivers and the Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico is a partially landlocked ocean basin largely surrounded by the North American continent and the island of Cuba. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. In...

.

The western area focused its commerce on neighbors to the west, and many citizens felt that the more populous eastern areas were too dominant in the Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

and insensitive to their needs. Major crisis in the Virginia state government over these differences was averted on more than one occasion during the period before the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, but the underlying problems were fundamental and never well resolved.

John Brown at Harpers Ferry, 1859

John BrownJohn Brown (abolitionist)

John Brown was an American revolutionary abolitionist, who in the 1850s advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to abolish slavery in the United States. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre during which five men were killed, in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas, and made his name in the...

(1800–1859), an abolitionist who considered slavery to be a sin, led an anti-slavery movement in Kansas and hoped to arm slaves and lead a violent revolt against slavery. With 18 armed men on Oct 16-17, 1859, he took hostages and freed slaves in Harpers Ferry, but no slaves answered his call and instead local militia surrounded Brown and his men in a firehouse. The President sent in a unit of U.S. Marines led by Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

; they stormed the firehouse and took Brown prisoner. The entire nation watched as Brown was convicted of treason against the state of Virginia and hanged. Southern outrage at what appeared to be a Yankee attempt to start a race war was a factor in causing the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Civil War and split

In 1861, as the United States itself became massively divided over regional issues, leading to the American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

(1861–1865), the western regions of Virginia split with the eastern portion politically, and the two were never reconciled as a single state again. In 1863, the western region was admitted to the Union as a new separate state, initially planned to be called the State of Kanawha

State of Kanawha

Kanawha was a proposed name for what later became the U.S. state of West Virginia, formed on October 24, 1861. It consisted of most of the northwestern counties of Virginia, which decided to secede from Virginia after Virginia joined the Confederate States of America on April 17, 1861 at the...

, but ultimately named West Virginia.

Separation

Clarksburg, West Virginia

Clarksburg is a city in and the county seat of Harrison County, West Virginia, United States, in the north-central region of the state. It is the principal city of the Clarksburg, WV Micropolitan Statistical Area...

recommended that each county in north-western Virginia send delegates to a convention to meet in Wheeling

Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in Ohio and Marshall counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia; it is the county seat of Ohio County. Wheeling is the principal city of the Wheeling Metropolitan Statistical Area...

on May 13, 1861.

When the First Wheeling Convention

Wheeling Convention

The 1861 Wheeling Convention was a series of two meetings that ultimately repealed the Ordinance of Secession passed by Virginia, thus establishing the Restored government of Virginia, which ultimately authorized the counties that organized the convention to become West Virginia. The convention was...

met, four hundred and twenty-five delegates from twenty-five counties were present, but soon there was a division of sentiment. Some delegates favored the immediate formation of a new state, while others argued that, as Virginia's secession

Secession

Secession is the act of withdrawing from an organization, union, or especially a political entity. Threats of secession also can be a strategy for achieving more limited goals.-Secession theory:...

had not yet been ratified or become effective, such action would constitute revolution against the United States. It was decided that if the ordinance were adopted (of which there was little doubt) another convention including the members-elect of the legislature should meet at Wheeling in June.

At the election (May 23, 1861), secession was ratified by a large majority in the state as a whole, in the western counties that would form the state of West Virginia the vote was approximately 34,677 against and 19,121 for ratification of the Ordinance of Secession.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

There were, therefore, two governments claiming to represent all of Virginia, one owing allegiance to the United States and one to the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

. The pro-northern government authorized the creation of the state of Kanawha

State of Kanawha

Kanawha was a proposed name for what later became the U.S. state of West Virginia, formed on October 24, 1861. It consisted of most of the northwestern counties of Virginia, which decided to secede from Virginia after Virginia joined the Confederate States of America on April 17, 1861 at the...

, consisting of most of the counties that now comprise West Virginia. A little over one month later, Kanawha was renamed West Virginia. The Wheeling Convention, which had taken a recess until August 6, reassembled on August 20 and called for a popular vote on the formation of a new state and for a convention to frame a constitution if the vote should be favorable.

The composition of the members of all three Wheeling Conventions, the May (First) Convention, the June (Second) Convention, and the Constitutional Convention, was of an irregular nature. The members of the May Convention were chosen by groups of Unionists, mostly in the far Northwestern counties. Over one-third came from the counties around the northern panhandle. The May Convention resolved to meet again in June should the Ordinance of Secession be ratified by public poll on May 23, 1861, which it was. The June Convention consisted of 104 members, 35 of which were members of the General Assembly in Richmond, some elected in the May 23rd vote, and some hold-over State Senators. Arthur Laidley, elected to the General Assembly from Cabell County, attended the June Convention but refused to take part. The other delegates to the June Convention were "chosen even more irregularly-some in mass meetings, others by county committee, and still others were seemingly self-appointed". It was this June Convention which drafted the Statehood resolution. The Constitutional Convention met in November 1861, and consisted of 61 members. Its composition was just as irregular. A delegate representing Logan County was accepted as a member of this body, though he did not live in Logan County, and his "credentials consisted of a petition signed by fifteen persons representing six families". The large number of Northerners at this convention caused great distrust over the new Constitution during Reconstruction years. In 1872, under the leadership of Samuel Price

Samuel Price

Samuel Price was a United States Senator from West Virginia. Born in Fauquier County, Virginia, he moved with his parents to Preston County in 1815. He received a preparatory training, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1832, commencing the practice of his profession in Nicholas and...

, former Lt. Governor of Virginia, the Wheeling constitution was discarded, and an entirely new one was written along ante-bellum principles. A Constitution of Our Own

The Wheeling politicians controlled only a small part of West Virginia. On September 20, 1862, Arthur Boreman wrote to Francis Pierpoint from Parkersburg: "The whole country South and East of us is abandoned to the Southern Confederacy—Men are here from the counties above named--[Wirt, Jackson, Roane] and indeed from Clay, Nicholas, &c &c,--who have been run off from their homes—Indeed the Ohio border is lined with refugees from Western Virginia. We are in worse condition than we were a year ago—These people come to me every day and say they can't stay at home...They must either have protection or abandon the country entirely... If they attempt to stay at home—they must keep their horses hid—and they dare not sleep at home but in the woods—and when at home in the day time they are in constant fear of their lives... The secessionists remain at home & are safe & now claim they are in the Southern Confederacy—which is practically the fact..."

Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2009, the city had a total population of 139,966. Located along the Western bank of the Potomac River, Alexandria is approximately six miles south of downtown Washington, D.C.Like the rest of northern Virginia, as well as...

from which he asserted jurisdiction over the counties of Virginia within the Federal lines.

Legality

The question of the constitutionality of the formation of the new state was eventually brought before the Supreme Court of the United StatesSupreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

, in the case of Virginia v. West Virginia

Virginia v. West Virginia

Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39 , is a 6-to-3 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States which held that where a governor has discretion in the conduct of the election, the legislature is bound by his action and cannot undo the results based on fraud...

, 78 U.S. 39 (1871). Berkeley

Berkeley County, West Virginia

Berkeley County is a county located in the Eastern Panhandle region of the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population is 104,169, making it the second-most populous county in West Virginia, behind Kanawha...

and Jefferson

Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County is a county located in the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 53,498. Its county seat is Charles Town...

counties lying on the Potomac east of the mountains, in 1863, with the consent of the Reorganized government of Virginia voted in favor of annexation to West Virginia. Many voters absent in the Confederate army when the vote was taken refused to acknowledge the transfer upon their return. The Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

repealed the act of cession and in 1866 brought suit against West Virginia asking the court to declare the counties a part of Virginia which would have in essence made West Virginia's admission as a state unconstitutional. Meanwhile Congress on March 10, 1866 passed a joint resolution recognizing the transfer. The Supreme Court decided in favor of West Virginia, and there has been no further question.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, West Virginia suffered comparatively little. Union General George B. McClellanGeorge B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

's forces gained possession of the greater part of the territory in the summer of 1861. Following Confederate General Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

's defeat at Cheat Mountain in the same year, Union supremacy in western Virginia was never again seriously challenged. In 1863, General John D. Imboden

John D. Imboden

John Daniel Imboden was a lawyer, teacher, Virginia state legislator. During the American Civil War, he was a Confederate cavalry general and partisan fighter...

, with 5,000 Confederates, overran a considerable portion of the state. Bands of guerrillas burned and plundered in some sections, and were not entirely suppressed until after the war was ended. Estimates of the numbers of soldiers from the state, Union and Confederate, have varied widely, but recent studies have placed the numbers about equal, from 22,000-25,000 each. The low vote turnout for the statehood referendum was due to many factors. On June 19, 1861 the Wheeling convention enacted a bill entitled "Ordinance to Authorize the Apprehending of Suspicious Persons in Time of War" which stated that anyone who supported Richmond or the Confederacy "shall be deemed...subjects or citizens of a foreign State or power at war with the United States.". Many private citizens were arrested by Federal authorities at the request of Wheeling and interred in prison camps, most notably Camp Chase

Camp Chase

Camp Chase was a military staging, training and prison camp in Columbus, Ohio, during the American Civil War. All that remains of the camp today is a Confederate cemetery containing 2,260 graves. The cemetery is located in what is now the Hilltop neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio.- History :Camp Chase...

in Columbus, Ohio. Camp Chase Civil Prisoners. Soldiers were also stationed at the polls to discourage secessionists and their supporters. In addition, a large portion of the state was secessionist, and any polls there had to be conducted under military intervention. The vote was further compromised by the presence of an undetermined number of non-resident soldier votes.

At the Constitutional Convention on December 14, 1861 the issue of slavery was raised by Rev. Gordon Battelle, an Ohio native, who wished to introduce a resolution for gradual emancipation. Granville Parker, originally from Massachusetts and a member of the convention, described the scene-"I discovered on that occasion as I never had before, the mysterious and over-powering influence 'the peculiar institution' had on men otherwise sane and reliable. Why, when Mr. Battelle submitted his resolutions, a kind of tremor-a holy horror, was visible throughout the house!" Instead of Rev. Battelle's resolution a policy of "Negro exclusion" for the new state was adopted to keep any new slaves, or freemen, from taking up residence, in the hope that this would satisfy abolitionist sentiment in Congress. When the statehood bill reached Congress, however, the lack of an emancipation clause prompted opposition from Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner was an American politician and senator from Massachusetts. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction,...

and Senator Benjamin Wade

Benjamin Wade

Benjamin Franklin "Bluff" Wade was a U.S. lawyer and United States Senator. In the Senate, he was associated with the Radical Republicans of that time.-Early life:...

of Ohio. A compromise was reached known as the Willey Amendment, which was approved by Unionist voters in the state on March 26, 1863. It called for the gradual emancipation of slaves based on age after July 4, 1863. Slavery was officially abolished by West Virginia on February 3, 1865. (It took the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution officially abolished and continues to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, passed by the House on January 31, 1865, and adopted on December 6, 1865. On...

to the U.S. Constitution accomplished on December 6, 1865 to abolish slavery nationwide).

During the war and for years afterwards, partisan feeling ran high. The property of Confederates might be confiscated, and, in 1866, a constitutional amendment disfranchising all who had given aid and comfort to the Confederacy was adopted. The addition of the Fourteenth

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

and Fifteenth Amendments

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

to the United States Constitution caused a reaction, the Democratic Party secured control in 1870, and in 1871 the constitutional amendment of 1866 was abrogated. The first steps toward this change had been taken, however, by the Republicans in 1870. In 1872, an entirely new constitution was adopted (August 22).

Following the war, Virginia unsuccessfully brought a case to the Supreme Court challenging the secession of Berkeley County

Berkeley County, West Virginia

Berkeley County is a county located in the Eastern Panhandle region of the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population is 104,169, making it the second-most populous county in West Virginia, behind Kanawha...

and Jefferson County

Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County is a county located in the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 53,498. Its county seat is Charles Town...

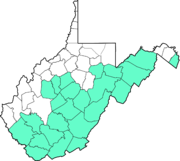

to West Virginia. (Five more counties were formed later, to result in the current 55).

President Lincoln was in a close campaign when he won reelection in 1864. However, the act that allowed the state to be created was signed in 1862, two years before Lincoln's re-election would have been an issue in any real way.

Enduring disputes

Beginning in Reconstruction, and for several decades thereafter, the two states disputed the new state's share of the pre-war Virginia government's debt, which had mostly been incurred to finance public infrastructure improvements, such as canals, roads, and railroads under the Virginia Board of Public WorksVirginia Board of Public Works

The Virginia Board of Public Works was a governmental agency which oversaw and helped finance the development of Virginia's internal transportation improvements during the 19th century. In that era, it was customary to invest public funds in private companies, which were the forerunners of the...

. Virginians led by former Confederate

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

General William Mahone

William Mahone

William Mahone was a civil engineer, teacher, soldier, railroad executive, and a member of the Virginia General Assembly and U.S. Congress. Small of stature, he was nicknamed "Little Billy"....

formed a political coalition based upon this theory, the Readjuster Party

Readjuster Party

The Readjuster Party was a political coalition formed in Virginia in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the American Civil War. Readjusters aspired "to break the power of wealth and established privilege" and to promote public education, a program which attracted biracial support....

. Although West Virginia's first constitution provided for the assumption of a part of the Virginia debt, negotiations opened by Virginia in 1870 were fruitless, and in 1871 that state funded two-thirds of the debt and arbitrarily assigned the remainder to West Virginia. The issue was finally settled in 1915, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that West Virginia owed Virginia $12,393,929.50. The final installment of this sum was paid off in 1939.

Disputes about the exact location of the border in some of the northern mountain reaches between Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia, and is part of the Washington Metropolitan Area. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the county is estimated to be home to 312,311 people, an 84 percent increase over the 2000 figure of 169,599. That increase makes the county the fourth...

and Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County is a county located in the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 53,498. Its county seat is Charles Town...

continued well into the 20th century. In 1991, both state legislatures appropriated money for a boundary commission to look into 15 miles (24.1 km) of the border area.

Salt

The new state benefited from development of its mineral resources more than any other single economic activity after Reconstruction. Much of the northern panhandle and north-central portion of the State are underlain by bedded saltSalt

In chemistry, salts are ionic compounds that result from the neutralization reaction of an acid and a base. They are composed of cations and anions so that the product is electrically neutral...

deposits over 50 feet (15.2 m) thick. Salt mining had been underway since the 18th century, though that which could be easily obtained had largely played out by the time of the American Civil War, when the red salt of Kanawha County

Kanawha County, West Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 200,073 people, 86,226 households, and 55,960 families residing in the county. The population density was 222 people per square mile . There were 93,788 housing units at an average density of 104 per square mile...

was a valued commodity of first Confederate, and later Union forces. Newer technology has since proved that West Virginia has enough salt resources to supply the nation's needs for an estimated 2,000 years. During recent years, production has been about 600,000 to 1,000,000 tons per year. http://www.wvgs.wvnet.edu/www/geology/geolmrsa.htm

Coal

In the 1850s, geologistGeologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

s such as British expert Dr. David T. Ansted

David T. Ansted

David Thomas Ansted was an English geologist and author.- Youth, education :Ansted was born in London on 5 February 1814. He was educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, and after taking his degree of M.A...

(1814–1880), surveyed potential coal fields and invested in land and early mining projects. After the War, with the new railroads came a practical method to transport large quantities of coal to expanding U.S. and export markets. Among the numerous investors were Charles Pratt

Charles Pratt

Charles Pratt was a United States capitalist, businessman and philanthropist.Pratt was a pioneer of the U.S. petroleum industry, and established his kerosene refinery Astral Oil Works in Brooklyn, New York. An advertising slogan was "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil." He...

and New York City mayor Abram S. Hewitt, whose father-in law, Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and candidate for President of the United States...

, had been a key man in earlier development of the anthracite coal

Anthracite coal

Anthracite is a hard, compact variety of mineral coal that has a high luster...

regions centered in eastern Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

and northwestern New Jersey

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

. As those mines were playing out by the end of the 19th century, these men were among investors and industrialists who focused new interest on the largely untapped coal resources of West Virginia.

Accidents in Coal Mines

Rakes (2008) examines coal mine fatalities in the state in the first half of the 20th century before safety regulations were strictly enforced in the 1960s. Besides the well-publicized mine disasters that killed a number of miners at a time, there were many smaller episodes in which one or two miners lost their lives. Mine accidents were considered inevitable, and mine safety did not appreciably improve the situation because of lax enforcement. West Virginia's mines were considered so unsafe that immigration officials would not recommend them as a source of employment for immigrants, and those unskilled immigrants who did work in the coal mines were more susceptible to death or injury. When the United States Bureau of MinesUnited States Bureau of Mines

For most of the 20th century, the U.S. Bureau of Mines was the primary United States Government agency conducting scientific research and disseminating information on the extraction, processing, use, and conservation of mineral resources.- Summary :...

was given more authority to regulate mine safety in the 1960s, safety awareness improved, and West Virginia coal mines became less dangerous.

Early railroads, shipping to East Coast and Great Lakes

The completion of the Chesapeake and Ohio RailwayChesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P...

(C&O) westerly across the state from Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

to the new city of Huntington

Huntington, West Virginia

Huntington is a city in Cabell and Wayne counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia, along the Ohio River. Most of the city is in Cabell County, for which it is the county seat. A small portion of the city, mainly the neighborhood of Westmoreland, is in Wayne County. Its population was 49,138 at...

on the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

in 1872 opened access to the New River Coalfield

New River Coalfield

The New River Coalfield is located in northeastern Raleigh County and southern Fayette County, West Virginia. Commercial mining of coal began in the 1870s and thrived into the 20th century. The coal in this field is a low volatile coal, and the seams of coal that have been mined include Sewell,...

. Within 10 years, the C&O was building tracks east from Richmond down the Virginia Peninsula

Virginia Peninsula