Henry H. Rogers

Encyclopedia

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was a United States

capitalist

, businessman, industrialist, financier

, and philanthropist

. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil

.

, Massachusetts

, on January 29, 1840. He was the son of Rowland Rogers, a former ship captain, bookkeeper, and grocer, and Mary Eldredge Huttleston Rogers. Both parents were descended from the Pilgrims who arrived in the 17th century aboard the Mayflower

. His mother's family had earlier used the spelling "Huddleston" rather than "Huttleston." (Consequently, Henry Rogers' name is often misspelled.)

The family moved to nearby Fairhaven, Massachusetts

, a fishing village across the Acushnet River

from the great whaling

port, New Bedford

. Fairhaven is a small seaside town on the south coast of Massachusetts. It borders the Acushnet River to the west and Buzzards Bay

to the south. Fairhaven was incorporated in 1812 and was already steeped in history when "Hen" Rogers was just a boy. Fort Phoenix

is in Fairhaven. There, during the American Revolution

, British troops once stormed the area. Also within sight of the fort, the first naval battle of the American Revolution took place on May 14, 1775.

In the mid 1850s, whaling was already an industry in decline in New England

. The emergence of petroleum

and later natural gas

as a replacement fuel for lighting in the second half of the 19th century caused a much further decline.

Henry Rogers' father was one of the many men of New England who changed from a life on the sea to other work to provide for their families. As a teenager, "Hen" Rogers carried newspaper

s and he worked in his father's grocery store, making deliveries by wagon. He was only an average student, and was in the first graduating class of the local high school in 1857. Continuing to live with his parents, he hired on with the Fairhaven Branch Railroad

, an early precursor of the Old Colony Railroad

, as an expressman

and brakeman

, working for 3–4 years while carefully saving his earnings.

and its newly discovered oil fields. Borrowing another US$600, the young partners began a small refinery

at McClintocksville

near Oil City

. They named their new enterprise Wamsutta Oil Refinery

.

The old Native American name "Wamsutta

" was apparently selected in honor of their hometown area of New England, where Wamsutta Company

in nearby New Bedford

had opened in 1846, and was a major employer. The Wamsutta Company was the first of many textile

mills that gradually came to supplant whaling as the principal employer in New Bedford.

Rogers and Ellis and their refinery

made US$30,000 their first year. This amount was more than the earnings of three whaling ship trips during an average voyage of more than a year's duration. When Rogers returned home to Fairhaven for a short vacation the next year, he was greeted as a success.

While vacationing in Fairhaven in 1862, Rogers married his childhood sweetheart, Abbie Palmer Gifford

, who was also of Mayflower lineage. She returned with him to the oil fields where they lived in a one-room shack along Oil Creek where her young husband and Ellis worked the Wamsutta Oil Refinery. While they lived in Pennsylvania, their first daughter, Anne Engle, was born in 1865. They had five surviving children together, four girls and a boy. Another son died at birth.

After the young family moved to New York in 1866, Cara Leland Rogers was born in Fairhaven in 1867, Millicent was born in 1873, followed by Mary (a.k.a. Mai)

in 1875. Their son, Henry Huttleston Rogers Jr., was born in 1879, and was known as Harry.

Abbie Palmer Gifford Rogers

died unexpectedly on May 21, 1894. Her childhood home, a two-story, gable-end frame house built in the Greek Revival style, has been preserved. It is made available for tours of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, where she and her husband grew up.

In 1896, the widower Rogers remarried, to Emelie Augusta Randel Hart, a divorcée and New York socialite. They had no children.

(1830–91). Born in Watertown, Massachusetts

, Pratt had been one of eleven children. His father, Asa Pratt, was a carpenter. Of modest means, he spent three winters as a student at Wesleyan Academy, and is said to have lived on a dollar a week at times. In nearby Boston, Massachusetts, Pratt joined a company specializing in paints and whale oil products. In 1850 or 1851, he came to New York City

, where he worked for a similar company handling paint and oil.

Pratt was a pioneer of the natural oil industry, and established his kerosene

refinery Astral Oil Works

in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn, New York. Pratt's product later gave rise to the slogan, "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil". He also later founded the Pratt Institute

.

When Pratt met Rogers at McClintocksville on a business trip, he already knew Charles Ellis, having earlier bought whale oil from him back east in Fairhaven. Although Ellis and Rogers had no wells and were dependent upon purchasing crude oil to refine and sell to Pratt, the two young men agreed to sell the entire output of their small Wamsutta refinery to Pratt's company at a fixed price. This worked well at first. Then, a few months later, crude oil prices suddenly increased due to manipulation by speculators. The young entrepreneur

s struggled to try to live up to their contract with Pratt, but soon their surplus was wiped out. Before long, they were heavily in debt to Pratt.

Charles Ellis gave up, but in 1866, Henry Rogers went to Pratt in New York and told him he would take personal responsibility for the entire debt. This so impressed Pratt that he immediately hired him for his own organization.

if sales ran over $50,000 a year. The Rogers' family moved to Brooklyn. Rogers moved steadily from foreman to manager, and then superintendent of Pratt's Astral Oil Refinery. He accomplished and exceeded the substantial sales increase goal which Pratt had set when recruiting him. As promised, Pratt gave Rogers an interest in the business. In 1867, with Henry Rogers as a partner, he established the firm of Charles Pratt and Company

. In the next few years, Rogers became, in the words of Elbert Hubbard

, Pratt's "hands and feet and eyes and ears" (Little Journeys to the Homes, 1909). As their family grew, Henry and Abbie continued to live in New York City, but vacationed frequently at Fairhaven.

While working with Pratt, Rogers invented an improved way of separating naphtha

, a light oil similar to kerosene

, from crude oil. He was granted U.S. Patent # 120,539 on October 31, 1871.

, Samuel Andrews, and Henry M. Flagler (of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

, a Cleveland-based refining company) and the South Improvement Company

. In developing what would become Standard Oil

, Rockefeller, a manager of extraordinary abilities, and Flagler, an exceptional marketer, recognized that the costs and control of the shipment of crude oil would be key elements in competition with other refiners. With its combination of clever market manipulation, and hard-nosed dealings with the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad

(PRR), the South Improvement scheme was an example of the type of business tactics which Rockefeller and his associates used to become successful. Although Rockefeller became the target of many who decried Standard Oil's ruthlessness in subsequent years, the South Improvement rebate scheme was Flagler's idea.

South Improvement was basically a mechanism to obtain secret favorable net rates from Tom Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad

(PRR) and other railroads through secret rebate

s from the common carrier

. A "common carrier" is somewhat like a utility, inasmuch as it often has certain rights, powers and monopolies on its services beyond those normally afforded regular business enterprises. A common carrier was expected to serve the public good and treat its customers uniformly. Rates in that era were promulgated and published in what was called "tariffs" and were public information. The rebate scheme was done outside of that process.

Newspapers were quick to publicize the issue. The injustice of the South Improvement scheme outraged many independent oil producers and owners of refineries. Rogers led the opposition among the New York refiners. The New York interests formed an association, and about the middle of March 1872 sent a committee of three, with Rogers as head, to Oil City to consult with the Oil Producers' Union. Working with the Pennsylvania independents, Rogers and the New York delegation managed to forge an agreement with the railroads, whose leaders eventually agreed to open their rates to all and promised to end their shady dealings with South Improvement.

Rockefeller and his associates quickly started another approach, which frequently included buying-up opposing interests. Their dominance of the growing industry and the squeezing out of smaller competitors continued and expanded. But, the South Improvement incident prompted growing public sentiment to support governmental oversight and regulation of large businesses, including the railroads. Congress passed new antitrust laws, the administration created the Interstate Commerce Commission

(ICC), and the courts eventually ordered the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust in the early 20th century.

By this date, Charles Pratt was reaching an age to consider retirement, and he subsequently devoted much of his time and interests to activities such as founding the Pratt Institute. However, Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt

(1858 to 1913), became Corporate Secretary of Standard Oil. As a part owner of Pratt and Company, Rogers, who was about 35 years old, now owned a share of Standard Oil himself. In the deal, Rockefeller had also added Henry Rogers to his team. He undoubtedly placed a high value on Rogers' potential. History does not tell us if he foresaw that the promising young man was destined to become one of his major partners.

, long regarded as the principal founder, was of a modest background and education. Born in New York in 1839, his family moved to Cleveland in 1855. His first job was as an assistant bookkeeper for a produce company. He delighted, as he later recalled, in "all the methods and systems of the office". He became particularly well-skilled at calculating transportation costs, a skill which would later serve him particularly well. He worked in variety of small business enterprises during the next few years, owning interests in several.

During this time, Rockefeller became friends with Henry Morrison Flagler. The two men had much in common, as they were each conservative, hard-working and energetic, and driven to make money. Their backgrounds included working separately for a number of years in various retail enterprises, including the grain business. Although teetotalers personally, distilled spirits were a byproduct of the handling of corn, and each embraced the business opportunity that presented; making money was clearly paramount.

Of their various separate forays into business, financial results for each had been mixed. Flagler, 9 years senior to Rockefeller, had been completely wiped out financially in a venture into salt. Only a loan from a relative, Stephen V. Harkness

, allowed him to keep creditors at bay and stay out of total ruin.

In the second half of the 19th century, the United States began a transition from use of whale oil to petroleum for heating and lighting. Discovery of oil fields in western Pennsylvania in the late 1850s and the promise of increased industrial activity and economic growth after the end of the American Civil War

combined to make the refining of crude oil seem an attractive business to Rockefeller. He and Flagler enlisted chemist Samuel Andrews and with his brother, William Rockefeller

, Jabez Bostwick

, and Flagler's relative and silent partner

, Stephen V. Harkness

, went into the refining business in Cleveland as Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

.

By all accounts, Rockefeller was an extraordinarily talented manager and financial planner, Flagler was an exceptional marketer, and Andrews had the know-how to oversee refining aspects. It was to be a very successful combination. As the demand for kerosene and a new byproduct, gasoline, grew in the United States, by 1868, what was to become Standard Oil was the world's largest oil refinery.

In 1870, Rockefeller formed Standard Oil Company of Ohio

and started his strategy of buying up the competition and consolidating all oil refining under one company. It was during this period that the Pratt interests and Henry Rogers were brought into the fold. By 1878 Standard Oil held about 90% of the refining capacity in the United States.

Flagler's wife was in failing health due to what was later determined to be tuberculosis

. On advice of her physician, he took her to Florida for the winter months beginning in 1877, and she did seem to improve with the gentle winter and cool ocean breezes there. While in Florida, Flagler was struck with the lack of good rail transportation south of Jacksonville

, the equally poor availability of good lodging, and the potential the impoverished state held as a vacation destination for northerners. Sensing a major business opportunity, he began to invest and become a major developer of Florida's east coast in what many regard as his "second career." However, his ventures in Florida marked the beginning of his gradual reduction in management participation at Standard Oil.

In 1881 the company was reorganized as the Standard Oil Trust. In 1885, the headquarters were relocated from Cleveland to New York City

. By this time, the three main men of Standard Oil Trust had become John D. Rockefeller, his brother William, and Henry Rogers, who had emerged as a key financial strategist. By 1890, Rogers was a vice president of Standard Oil and chairman of the organization's operating committee.

s were first developed in Pennsylvania in the 1860s to replace transport in wooden barrels loaded on wagons drawn by mules and driven by teamster

s. This mule-drawn transportation was expensive and fraught with difficulties: leaking barrels, muddy trails, wagon breakdowns and mule/driver problems.

The first successful metal pipeline was completed in 1865, when Samuel Van Syckel built a four-mile (6 km) pipeline from Pithole, Pennsylvania, to the nearest railroad. This initial success led to the construction of pipelines to connect crude oil production, increasingly moving west as new fields were discovered and Pennsylvania fields declined, to refineries located near major demand centers in the Northeast. Biographer Z. James Varanini writes, "the completion of these pipelines represented a move towards a new type of interconnectivity of previously isolated states."

When Rockefeller observed this, he began to acquire many of the new pipelines. Soon, his Standard Oil companies owned a majority of the lines, which provided cheap, efficient transportation for oil. Cleveland, Ohio

, became a center of the refining industry principally because of its transportation systems.

Rogers conceived the idea of long pipelines for transporting oil and natural gas

. In 1881, the National Transit Company was formed by Standard Oil to own and operate Standard's pipelines. The National Transit Company remained one of Rogers' favorite projects throughout the rest of his life.

East Ohio Gas Company (EOG) was incorporated on September 8, 1898, as a marketing company for the National Transit Company, the natural gas arm of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. The company launched its business by selling to consumers in northeast Ohio gas produced by another National Transit subsidiary, Hope Natural Gas Company.

Rubber-manufacturing city Akron, Ohio

, was the first to take advantage of the lower prices for natural gas. It granted the East Ohio Gas Company a franchise in September 1898, the same month that the company was founded. During the winter of 1898–99, the National Transit Company built a 10-inch wrought iron

pipeline that stretched from the Pipe Creek on the Ohio River

to Akron, with branches to Canton, Massillon, Dover, New Philadelphia, Uhrichsville, and Dennison. The first gas from the pipeline burned in Akron on May 10, 1899.

, long the leading steel magnate of Pittsburgh

, retired at the turn of the 20th century, and refocused his interests on philanthropy. His steel holdings were consolidated into the new United States Steel Corporation. Standard Oil's interest in steel properties led to Rogers' becoming one of the directors when it was organized in 1901.

. This act is the source of all American anti-monopoly laws. The law forbids every contract, scheme, deal, conspiracy to restrain trade. It also forbids inspirations to secure monopoly of a given industry. The Standard Oil Trust attracted attention from antitrust

authorities. The Ohio

Attorney General

filed and won an antitrust suit in 1892.

Ida M. Tarbell

, an American

author and journalist, who was known as one of the leading muckrakers, criticized Standard Oil practices.

Born in Erie County, Pennsylvania

, Tarbell saw her own family affected by unorthodox business practices, as her father was forced out of business around 1872 by the South Improvement Company

scheme. In 1894, she was hired by McClure's

magazine. She soon turned to investigative journalism

, and redefined the in-depth technique of writing. She used documentation concerning Standard Oil, as well as interviews of employees, competitors, lawyers and experts on the topic. Tarbell and her fellow staff members Ray Stannard Baker

and Lincoln Steffens

became a celebrated muckraking trio.

Tarbell met Rogers, by then the most senior and powerful director of Standard Oil, through his friend, Mark Twain

. They began to meet in January 1902 and continued for the next two years. As Tarbell brought up case histories, Rogers provided an explanation, documents and figures concerning the case. Rogers may have believed Tarbell intended a complimentary work, as he was apparently candid. Her interviews with him were the basis of her negative exposé of Standard Oil's questionable business practices. Tarbell's investigations of Standard Oil for McClure's, ran in 19 parts from November 1902 to October 1904. They were collected and published as The History of the Standard Oil Company

in 1904. The book placed fifth in a 1999 list of the top 100 works of journalism in the 20th century.

Although public opposition to Rockefeller and Standard Oil existed prior to Tarbell's investigation, there had been general opposition to Standard Oil and trusts. Her book is widely credited with hastening the 1911 breakup of Standard Oil. "They had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me", Tarbell wrote about the company.

The United States Supreme Court

declared the company to be an "unreasonable" monopoly

under the Sherman Antitrust Act

on May 15, 1911 in v. . The owners remained in charge of the smaller companies which made up four of the Seven Sisters

.

Standard Oil developed a reputation for dubious business practices, including subduing competitors and engaging in illegal transportation deals with the railroad companies to undercut competitors' prices. With the growing demand for oil other than for heat and light, Standard Oil, formed many years before the discovery of Spindletop

in Texas, was well-placed to control the growth of the oil business in the United States. Observers thought it owned and controlled all aspects of the trade.

interests was one of business warfare.

properties in the western United States. In 1899, with William Rockefeller, and Thomas W. Lawson

, he formed the first $75,000,000 section of the gigantic trust, Amalgamated Copper Mining Company, which was the subject of much acrid criticism then and for years afterward. In the building of this great trust, some of the most ruthless strokes in modern business history were dealt: the $38,000,000 "watering" of the stock of the first corporation, its subsequent manipulation, the seizure of the copper property of the Butte & Boston Consolidated Mining Company, the using of the latter as a weapon against the Boston & Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company, the guerrilla warfare

against certain private interests, and the wrecking of the Globe Bank of Boston.

A holding company aimed at controlling copper production and distribution, Amalgamated Copper controlled the copper mines of Butte, Montana

and later became Anaconda Copper Company.

and Meiers Corners

. Trolleys, which cost only a nickel a ride through most of their existence, help facilitate mass transit across the Island by reaching communities not serviced by trains. Henry H. Rogers was long-known as the Staten Island transit magnate, and was also involved with the Staten Island-Manhattan Ferry Service

and the Richmond Power and Light Company.

in the latter's extensive railroad operations. He was a director of the Santa Fe, St. Paul, Erie

, Lackawanna, Union Pacific

, and several other large railroads. However, he also involved himself in at least three West Virginia short-line railroad projects, one of which would grow much larger than he probably anticipated.

who was also secretly involved with Standard Oil

. Charles M. Pratt

and Rogers were two of the largest owners and the Ohio River Railroad's General Manager was C.M. Burt. Its General Solicitor was former West Virginia governor William A. MacCorkle

. The owners wished to sell the railroad, which was losing money.

Under Rogers' leadership, they formed a subsidiary, West Virginia Short Line Railroad, to build a new line between New Martinsville

and Clarksburg

to reach new coal mining areas, into territory already planned for expansion by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

(B&O). The expansion plans had the desired effect of essentially forcing B&O to purchase the Ohio River Railroad to block the competition in the new coal areas. The Ohio River Railroad was sold to B&O in 1898.

in 1898 by either a son of Charles Pratt or the estate of Charles Pratt. Its line ran 15 miles (24.1 km) from the Kanawha River

up a tributary called Paint Creek. Once again, new coal mining territory was involved. Rogers, acting on behalf of Charles Pratt and Company

negotiated its lease to the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

(C&O) in 1901 and its sale to a newly formed C&O subsidiary, Kanawha and Paint Creek Railway Company, in 1902.

(VGN), which eventually extended 600 miles (965.6 km) from the coal fields of southern West Virginia

to port near Norfolk

at Sewell's Point

, Virginia in the harbor of Hampton Roads

. Initially, Rogers' involvement in the project began in 1902 with Page's Deepwater Railway

Initially, Rogers' involvement in the project began in 1902 with Page's Deepwater Railway

, planned as an 80 miles (128.7 km) short line to reach untapped coal reserves in a very rugged portion of southern West Virginia, and interchange its traffic with the C&O and/or the N&W. The Deepwater Railway was probably intended for resale in the manner of the earlier two West Virginia short lines. However, if so, the ploy was foiled by collusion of the bigger railroads, who agreed with each other to neither purchase it or grant favorable interchange rates.

Page was the "front man" for the Deepwater project, and it is likely the leaders of the big railroads were unaware that their foe was backed by the wealthy Rogers, who did not give up a good fight easily. Instead of abandoning the project, Page and Rogers secretly developed a plan to extend their new railroad all the way across West Virginia and Virginia to port at Hampton Roads. They modified the Deepwater Railway charter to reach the Virginia-state line. A Rogers coal property attorney in Staunton, Virginia

formed another intrastate railroad in Virginia, the Tidewater Railway

.

The battle for the Tidewater Railway's rights-of-way displayed Rogers at his most crafty and ingenious. He was able to persuade the leading citizens of Roanoke

and Norfolk

, both strongholds of the rival Norfolk and Western, that his new railroad would be a boon to both communities, secretly securing crucial rights-of-way

in the process. In 1907, the name of the Tidewater Railway was changed to The Virginia Railway Company, and it acquired the Deepwater Railway to form the needed West Virginia-Virginia link.

Financed almost entirely from Rogers' own resources, and completed in 1909, instead of interchanging, the new Virginian Railway competed with the much larger Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

and Norfolk and Western Railway

for coal

traffic. Built following his policy of investing in the best route and equipment on initial selection and purchase to save operating expenses, the VGN enjoyed a more modern pathway built to the highest standards, and provided major competition to its larger neighboring railroads, each of whom tried several times unsuccessfully to acquire it after they realized it could not be blocked from completion.

However, the time and enormous effort Rogers expended on the project continued to undermine his already declining health, not only because of his Herculean work but also because of the uncertain economy of the period, exacerbated by the financial Panic of 1907

which began in March of that year. To obtain the needed financing, he was forced to pour many of his own assets into the railroad. Management of the funding Rogers was providing was handled by Boston

financier Godfrey M. Hyams

, with whom he had also worked on the Anaconda Company, and many other natural resource projects.

On July 22, 1907, he suffered a debilitating stroke

. Over a period of about five months, he gradually recovered. In 1908, he put the remaining financing in place needed to see his railroad to completion. When completed the following year, the Virginian Railway was called by the newspapers "the biggest little railway in the world" and proved both viable and profitable.

Many historians consider the Virginian Railway to be one of Henry Rogers' greatest legacies. The 600 miles (965.6 km) Virginian Railway (VGN) followed his philosophy regarding investing in the best equipment and paying its employees and vendors well throughout its profitable history. It operated some of the largest and most powerful steam, electric, and diesel locomotive

s throughout its 50-year history. Chronicled by rail historian and rail photographer H. Reid

in The Virginian Railway (Kalmbach, 1961), the VGN gained a following of railway enthusiasts which continues to the present day.

The VGN was merged into the Norfolk & Western in 1959. However, almost all of the former VGN mainline trackage in West Virginia

and about 50% of that in Virginia

is still in use in 2006 as the preferred route for eastbound coal trains for Norfolk Southern Corporation due to the more favorable gradients while crossing the Allegheny Mountains

' continental divide and the Blue Ridge Mountains

east of Roanoke, while most westbound traffic of empty coal cars uses the original Norfolk and Western main line.

" of his day, as times were changing. Nevertheless, Rogers amassed a great fortune, estimated at over $100 million. He invested heavily in various industries, including copper, steel, mining, and railways.

Much of what we know about Rogers and his style in business dealings were recorded by others. His behavior in public Court Proceedings provide some of the better examples and some insight. Rogers' business style extended to his testimony in many court settings. Before the Hepburn Commission of 1878, investigating the railroads of New York, he fine-tuned his circumlocutory, ambiguous, and haughty responses. His most intractable performance was later in a 1906 lawsuit by the state of Missouri

, which claimed that two companies in that state registered as independents were actually subsidiaries of Standard Oil, a secret ownership Rogers finally acknowledged.

In Marquis Who's Who for 1908, Rogers listed more than twenty corporations of which he was either president and director or vice president and director.

Henry H. Rogers is in the top 25 wealthiest men in America of all time. According to The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates - A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present published by two business professors in 1996, Rogers is #22, ranking ahead of J.P. Morgan, #23, Bill Gates

#31, William Rockefeller

#35, Warren Buffett

#39, J. Paul Getty

#67, and Frank W. Woolworth #82.

, Mark Twain

, and Booker T. Washington

. Beginning in 1885, he began to donate buildings to his hometown of Fairhaven, Massachusetts. These included a grammar school, Rogers School, built in 1885. The Millicent Library

was completed in 1893 and was a gift to the Town by the Rogers children in memory of their sister Millicent, who had died in 1890 at the age of 17.

Abbie Palmer (née Gifford) Rogers

presented the new Town Hall in 1894. The George H. Taber Masonic Lodge building, named for Rogers' boyhood mentor and former Sunday-school teacher, was completed in 1901. The Unitarian Memorial Church was dedicated in 1904 to the memory of Rogers' mother, Mary Huttleston (née Eldredge) Rogers. He had the Tabitha Inn built in 1905, and a new Fairhaven High School

, called "Castle on the Hill," was completed in 1906. Rogers funded the draining of the mill pond to create a park, installed the town's public water and sewer systems, and served as superintendent of streets for his hometown. Years later, Henry H. Rogers' daughter, Cara Leland Rogers Broughton (Lady Fairhaven), purchased the site of Fort Phoenix

, and donated it to the Town of Fairhaven in her father's memory.

. It was less than six weeks before full operations were scheduled to begin on his Virginian Railway. After a funeral at the First Unitarian Church in Manhattan

, his body was transported to Fairhaven by a New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad

train. He was interred beside Abbie in Fairhaven's Riverside Cemetery.

and Booker T. Washington

. He was instrumental in the education of Helen Keller

. Urged on by Twain, Rogers and his second wife financed her college education.

In 1899, Rogers had a luxury steam yacht

built by a shipyard in the Bronx. The Kanawha

, at 471-tons, was 200 feet (61 m) long and manned by a crew of 39. For the final ten years of his life, Rogers entertained friends as they sailed on cruises mostly along the East Coast of the United States, north to Maine and Canada, and south to Virginia. With Mark Twain

among his frequent guests, the movements of the Kanawha attracted great attention from the newspapers, the major public media of the era.

In 1893, a mutual friend introduced Rogers to humorist Mark Twain

In 1893, a mutual friend introduced Rogers to humorist Mark Twain

. Rogers reorganized Twain's tangled finances, and the two became close friends for the rest of Rogers' life. By the 1890s, Twain's fortunes began to decline; in his later life, Twain suffered from depression. He lost three of his four children, and his wife, Olivia Langdon, before his death in 1910.

Twain had some very bad times with his businesses. His publishing company ended up going bankrupt, and he lost thousands of dollars on a typesetting machine that was never finished. He also lost a great deal of revenue on royalties from his books being plagiarized

before he had a chance to publish them himself.

Rogers and Twain enjoyed a more than 16-year friendship. Rogers' family became Twain's surrogate family, and he was a frequent guest at the Rogers townhouse in New York City. Earl J. Dias described the relationship in these words: "Rogers and Twain were kindred spirits - fond of poker, billiards, the theater, practical jokes, mild profanity, the good-natured spoof. Their friendship, in short, was based on a community of interests and on the fact that each, in some way, needed the other." Their letters were published as Mark Twain's Correspondence with Henry Huttleston Rogers, 1893-1909, They had a standing joke that Twain was inclined to pilfer items from the Rogers household whenever he spent the night there as a guest. Two letters provide an illustration. Twain wrote to Anne Rogers that he had packed:

Rogers responded on October 31, 1906 with the following:

In April 1907, they traveled together on the Kanawha to the Jamestown Exposition

in celebration of the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony. Twain returned to Norfolk, Virginia

with Rogers in April 1909, and was the guest speaker at the dedication dinner held for the newly completed Virginian Railway

, a "Mountains to Sea" engineering marvel of the day. The construction of the new railroad had been solely financed by industrialist Rogers.

, Rogers and Mark Twain first saw Helen Keller

, then sixteen years old. Although she had been made blind and mute by illness as a young child, she had been reached by her teacher-companion, Anne Sullivan

. When she was 20, Keller passed with distinction the entrance examination to Radcliffe College

. Twain praised "this marvelous child" and hoped that Helen would not be forced to retire from her studies because of poverty. He urged the Rogers to aid Keller and to solicit other Standard Oil chiefs to help her. The Rogers paid for her education at Radcliffe and arranged a monthly stipend. It was reduced after her marriage to John Macy.

Keller dedicated her book, The World I Live In, "To Henry H. Rogers, my Dear Friend of Many Years." On the fly leaf of Rogers' copy, she wrote, To Mrs Rogers The best of the world I live in is the kindness of friends like you and Mr Rogers.

's speeches at Madison Square Garden

in New York City

. The next day, Rogers contacted the educator and invited him to his offices. They had common ground in relatively humble beginnings and became strong friends. Washington became a frequent visitor to Rogers' office, his 85-room mansion in Fairhaven, and the yacht.

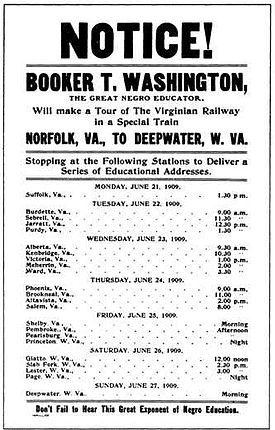

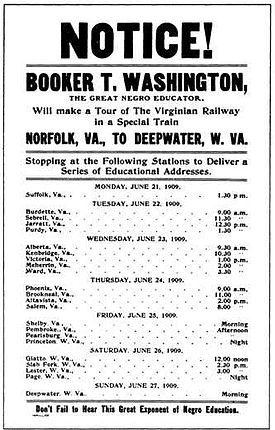

Although Rogers had died suddenly a few weeks earlier, in June 1909 Dr. Washington went on a previously arranged speaking tour along the newly completed Virginian Railway

Although Rogers had died suddenly a few weeks earlier, in June 1909 Dr. Washington went on a previously arranged speaking tour along the newly completed Virginian Railway

. He rode in Rogers' personal rail car, Dixie, making speeches at many locations over a seven-day period. Washington said Rogers had urged the trip to explore how to improve race relations and economic conditions for African American

s along the route of the new railway. It connected many previously isolated rural communities in the southern portions of Virginia

and West Virginia

.

Washington told about Rogers' philanthropy: "funding the operation of at least 65 small country schools for the education and betterment of African Americans in Virginia and other portions of the South, all unknown to the recipients." Rogers had also generously provided support to Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute. Rogers supported projects with at least partial matching funds

, in order to achieve more work, and to ensure recipients were also stakeholders.

, Millicent Library

, Unitarian Memorial Church

, and Fairhaven High School. A granite shaft on the High School lawn is dedicated to Rogers. In Riverside Cemetery, the Henry Huttleston Rogers Mausoleum is patterned after the Temple of Minerva

in Athens

, Greece

. Henry, his first wife Abbie, and several family members are interred there.

In 1916, Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company launched the SS H.H. Rogers, a Pratt-class tanker of 8,807 tons with a capacity of 119390 barrels (18,981,493.2 l) of oil. It was operated by Panama Transport Co., a subsidiary of Standard Oil of New Jersey. During World War II

, on February 21, 1943, it was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat in the North Atlantic Ocean

600 miles (965.6 km) off the coast of Ireland

while en route from Liverpool

, England

to the United States. All 73 persons aboard were saved.

In Virginia and West Virginia, former employees, area residents, and enthusiasts of the Virginian Railway consider the entire railroad to have been a memorial to him. Almost 50 years after it was merged into a competitor, Rogers' railroad has a remarkable following. One of the most active Yahoo! railway enthusiasts groups has more than 800 members. A passenger station has been restored in Suffolk, Virginia

, a replica built and museum established in Princeton, West Virginia

, and work is underway on a larger former VGN station in Roanoke

.

In 2004, volunteers engraved Rogers' initials (and those of VGN co-founder William Nelson Page) into new rail laid in Victoria, Virginia

. It carries a VGN Class 10-A caboose, built by the company and restored by members of the National Railway Historical Society

(NRHS) chapter in Roanoke. Fully equipped, it offers an interpretive display of the business conducted in a caboose along the historic right-of-way.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, businessman, industrialist, financier

Financier

Financier is a term for a person who handles typically large sums of money, usually involving money lending, financing projects, large-scale investing, or large-scale money management. The term is French, and derives from finance or payment...

, and philanthropist

Philanthropist

A philanthropist is someone who engages in philanthropy; that is, someone who donates his or her time, money, and/or reputation to charitable causes...

. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil

Standard Oil

Standard Oil was a predominant American integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company. Established in 1870 as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world and operated as a major company trust and was one of the world's first and largest multinational...

.

Youth and education

Henry Huttleston Rogers was born in MattapoisettMattapoisett, Massachusetts

Mattapoisett is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 6,463 at the 2008 census.For geographic and demographic information on the village of Mattapoisett Center, please see the article Mattapoisett Center, Massachusetts....

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

, on January 29, 1840. He was the son of Rowland Rogers, a former ship captain, bookkeeper, and grocer, and Mary Eldredge Huttleston Rogers. Both parents were descended from the Pilgrims who arrived in the 17th century aboard the Mayflower

Mayflower

The Mayflower was the ship that transported the English Separatists, better known as the Pilgrims, from a site near the Mayflower Steps in Plymouth, England, to Plymouth, Massachusetts, , in 1620...

. His mother's family had earlier used the spelling "Huddleston" rather than "Huttleston." (Consequently, Henry Rogers' name is often misspelled.)

The family moved to nearby Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Fairhaven is a town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, in the United States. It is located on the south coast of Massachusetts where the Acushnet River flows into Buzzards Bay, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean...

, a fishing village across the Acushnet River

Acushnet River

The Acushnet River is the largest river, long, flowing into Buzzards Bay in southeastern Massachusetts, in the United States. The name "Acushnet" comes from the Wampanoag or Algonquian word, "Cushnea", meaning "as far as the waters", a word that was used by the original owners of the land in...

from the great whaling

Whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales mainly for meat and oil. Its earliest forms date to at least 3000 BC. Various coastal communities have long histories of sustenance whaling and harvesting beached whales...

port, New Bedford

New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States, located south of Boston, southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, and about east of Fall River. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 95,072, making it the sixth-largest city in Massachusetts...

. Fairhaven is a small seaside town on the south coast of Massachusetts. It borders the Acushnet River to the west and Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay is a bay along the southern edge of Massachusetts in the United States. The name may also refer to:*Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, a village in Bourne, Massachusetts*Buzzards Bay , the name of the horse that won the 2005 Santa Anita Derby...

to the south. Fairhaven was incorporated in 1812 and was already steeped in history when "Hen" Rogers was just a boy. Fort Phoenix

Fort Phoenix

Fort Phoenix is a Revolutionary War-era fort located at the entrance to the Fairhaven-New Bedford harbor, south of U.S. 6 in Fort Phoenix Park in Fairhaven, Massachusetts....

is in Fairhaven. There, during the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, British troops once stormed the area. Also within sight of the fort, the first naval battle of the American Revolution took place on May 14, 1775.

In the mid 1850s, whaling was already an industry in decline in New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. The emergence of petroleum

Petroleum

Petroleum or crude oil is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds, that are found in geologic formations beneath the Earth's surface. Petroleum is recovered mostly through oil drilling...

and later natural gas

Natural gas

Natural gas is a naturally occurring gas mixture consisting primarily of methane, typically with 0–20% higher hydrocarbons . It is found associated with other hydrocarbon fuel, in coal beds, as methane clathrates, and is an important fuel source and a major feedstock for fertilizers.Most natural...

as a replacement fuel for lighting in the second half of the 19th century caused a much further decline.

Henry Rogers' father was one of the many men of New England who changed from a life on the sea to other work to provide for their families. As a teenager, "Hen" Rogers carried newspaper

Newspaper

A newspaper is a scheduled publication containing news of current events, informative articles, diverse features and advertising. It usually is printed on relatively inexpensive, low-grade paper such as newsprint. By 2007, there were 6580 daily newspapers in the world selling 395 million copies a...

s and he worked in his father's grocery store, making deliveries by wagon. He was only an average student, and was in the first graduating class of the local high school in 1857. Continuing to live with his parents, he hired on with the Fairhaven Branch Railroad

Fairhaven Branch Railroad

The Fairhaven Branch Railroad was a short-line railroad in Massachusetts. It ran from West Wareham on the Cape Cod main line of the Old Colony Railroad, southwest to Fairhaven, a town across the Acushnet River from New Bedford.-History:...

, an early precursor of the Old Colony Railroad

Old Colony Railroad

The Old Colony Railroad was a major railroad system, mainly covering southeastern Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island. It operated from 1845 to 1893. Old Colony trains ran from Boston to points such as Plymouth, Fall River, New Bedford, Newport, Providence, Fitchburg, Lowell and Cape Cod...

, as an expressman

Expressman

An expressman refers to anyone who has the duty of packing, managing, and ensuring the delivery of any cargo on board a train.During the 19th century, an expressman was someone whose responsibility it was to ensure the safe delivery of a train's gold or currency, which was secured in the "express...

and brakeman

Brakeman

A brakeman is a rail transport worker whose original job it was to assist the braking of a train by applying brakes on individual wagons. The advent of through brakes on trains made this role redundant, although the name lives on in the United States where brakemen carry out a variety of functions...

, working for 3–4 years while carefully saving his earnings.

Seeking his fortune

In 1861, 21-year-old Henry pooled his savings of approximately US$600 with a friend, Charles P. Ellis. They set out to western PennsylvaniaPennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

and its newly discovered oil fields. Borrowing another US$600, the young partners began a small refinery

Refinery

A refinery is a production facility composed of a group of chemical engineering unit processes and unit operations refining certain materials or converting raw material into products of value.-Types of refineries:Different types of refineries are as follows:...

at McClintocksville

McClintocksville, Pennsylvania

McClintocksville, Pennsylvania was a small community in Cornplanter Township in Venango County located in the state of Pennsylvania in the United States.- History :...

near Oil City

Oil City, Pennsylvania

Oil City is a city in Venango County, Pennsylvania that is known in the initial exploration and development of the petroleum industry. After the first oil wells were drilled nearby in the 1850s, Oil City became central in the petroleum industry while hosting headquarters for the Pennzoil, Quaker...

. They named their new enterprise Wamsutta Oil Refinery

Wamsutta Oil Refinery

Wamsutta Oil Refinery was established around 1861 in McClintocksville in Venango County near Oil City, Pennsylvania, in the United States. It was the first business enterprise of Henry Huttleston Rogers , who became a famous capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist.-...

.

The old Native American name "Wamsutta

Wamsutta

Wamsutta , also known as Alexander Pokanoket, as he was called by New England colonists, was the eldest son of Massasoit and a sachem of the Wampanoag native American tribe. His sale of Wampanoag lands to colonists other than those of the Plymouth Colony brought the Wampanoag considerable power,...

" was apparently selected in honor of their hometown area of New England, where Wamsutta Company

Wamsutta Company

Wamsutta Company, also known as Wamsutta Mills, was located in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a port known for its whaling ships. The company was named for Wamsutta, the son of an Native American chief who negotiated an early alliance with the English settlers of the Plymouth Colony in the 17th...

in nearby New Bedford

New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States, located south of Boston, southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, and about east of Fall River. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 95,072, making it the sixth-largest city in Massachusetts...

had opened in 1846, and was a major employer. The Wamsutta Company was the first of many textile

Textile

A textile or cloth is a flexible woven material consisting of a network of natural or artificial fibres often referred to as thread or yarn. Yarn is produced by spinning raw fibres of wool, flax, cotton, or other material to produce long strands...

mills that gradually came to supplant whaling as the principal employer in New Bedford.

Rogers and Ellis and their refinery

Refinery

A refinery is a production facility composed of a group of chemical engineering unit processes and unit operations refining certain materials or converting raw material into products of value.-Types of refineries:Different types of refineries are as follows:...

made US$30,000 their first year. This amount was more than the earnings of three whaling ship trips during an average voyage of more than a year's duration. When Rogers returned home to Fairhaven for a short vacation the next year, he was greeted as a success.

Marriage and family

- For more detailed information about Abbie and Henry Rogers' children, marriages and their descendants, see article Abbie G. RogersAbbie G. RogersAbbie Gifford Rogers , was the first wife of Henry Huttleston Rogers, , a United States capitalist, businesswoman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist....

While vacationing in Fairhaven in 1862, Rogers married his childhood sweetheart, Abbie Palmer Gifford

Abbie G. Rogers

Abbie Gifford Rogers , was the first wife of Henry Huttleston Rogers, , a United States capitalist, businesswoman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist....

, who was also of Mayflower lineage. She returned with him to the oil fields where they lived in a one-room shack along Oil Creek where her young husband and Ellis worked the Wamsutta Oil Refinery. While they lived in Pennsylvania, their first daughter, Anne Engle, was born in 1865. They had five surviving children together, four girls and a boy. Another son died at birth.

After the young family moved to New York in 1866, Cara Leland Rogers was born in Fairhaven in 1867, Millicent was born in 1873, followed by Mary (a.k.a. Mai)

Mary (Mai) Huttleston Rogers Coe

Mai Rogers Coe was born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. She was christened Mary Huttleston Rogers, and was the youngest of four daughters of Henry Huttleston Rogers and Abbie Palmer Rogers ....

in 1875. Their son, Henry Huttleston Rogers Jr., was born in 1879, and was known as Harry.

Abbie Palmer Gifford Rogers

Abbie G. Rogers

Abbie Gifford Rogers , was the first wife of Henry Huttleston Rogers, , a United States capitalist, businesswoman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist....

died unexpectedly on May 21, 1894. Her childhood home, a two-story, gable-end frame house built in the Greek Revival style, has been preserved. It is made available for tours of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, where she and her husband grew up.

In 1896, the widower Rogers remarried, to Emelie Augusta Randel Hart, a divorcée and New York socialite. They had no children.

Career

In Pennsylvania, Rogers was introduced to Charles PrattCharles Pratt

Charles Pratt was a United States capitalist, businessman and philanthropist.Pratt was a pioneer of the U.S. petroleum industry, and established his kerosene refinery Astral Oil Works in Brooklyn, New York. An advertising slogan was "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil." He...

(1830–91). Born in Watertown, Massachusetts

Watertown, Massachusetts

The Town of Watertown is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 31,915 at the 2010 census.- History :Archeological evidence suggests that Watertown was inhabited for thousands of years before the arrival of settlers from England...

, Pratt had been one of eleven children. His father, Asa Pratt, was a carpenter. Of modest means, he spent three winters as a student at Wesleyan Academy, and is said to have lived on a dollar a week at times. In nearby Boston, Massachusetts, Pratt joined a company specializing in paints and whale oil products. In 1850 or 1851, he came to New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, where he worked for a similar company handling paint and oil.

Pratt was a pioneer of the natural oil industry, and established his kerosene

Kerosene

Kerosene, sometimes spelled kerosine in scientific and industrial usage, also known as paraffin or paraffin oil in the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Ireland and South Africa, is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid. The name is derived from Greek keros...

refinery Astral Oil Works

Astral Oil Works

Astral Oil Works was founded in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn, New York by Charles Pratt. Pratt was a pioneer of the petroleum industry who formed Charles Pratt and Company with Henry H. Rogers. The Pratt interests became part of John D...

in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn, New York. Pratt's product later gave rise to the slogan, "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil". He also later founded the Pratt Institute

Pratt Institute

Pratt Institute is a private art college in New York City located in Brooklyn, New York, with satellite campuses in Manhattan and Utica. Pratt is one of the leading undergraduate art schools in the United States and offers programs in Architecture, Graphic Design, History of Art and Design,...

.

When Pratt met Rogers at McClintocksville on a business trip, he already knew Charles Ellis, having earlier bought whale oil from him back east in Fairhaven. Although Ellis and Rogers had no wells and were dependent upon purchasing crude oil to refine and sell to Pratt, the two young men agreed to sell the entire output of their small Wamsutta refinery to Pratt's company at a fixed price. This worked well at first. Then, a few months later, crude oil prices suddenly increased due to manipulation by speculators. The young entrepreneur

Entrepreneur

An entrepreneur is an owner or manager of a business enterprise who makes money through risk and initiative.The term was originally a loanword from French and was first defined by the Irish-French economist Richard Cantillon. Entrepreneur in English is a term applied to a person who is willing to...

s struggled to try to live up to their contract with Pratt, but soon their surplus was wiped out. Before long, they were heavily in debt to Pratt.

Charles Ellis gave up, but in 1866, Henry Rogers went to Pratt in New York and told him he would take personal responsibility for the entire debt. This so impressed Pratt that he immediately hired him for his own organization.

New York, oil refining

Pratt made Rogers foreman of his Brooklyn refinery, with a promise of a partnershipPartnership

A partnership is an arrangement where parties agree to cooperate to advance their mutual interests.Since humans are social beings, partnerships between individuals, businesses, interest-based organizations, schools, governments, and varied combinations thereof, have always been and remain commonplace...

if sales ran over $50,000 a year. The Rogers' family moved to Brooklyn. Rogers moved steadily from foreman to manager, and then superintendent of Pratt's Astral Oil Refinery. He accomplished and exceeded the substantial sales increase goal which Pratt had set when recruiting him. As promised, Pratt gave Rogers an interest in the business. In 1867, with Henry Rogers as a partner, he established the firm of Charles Pratt and Company

Charles Pratt and Company

Charles Pratt and Company was an oil company that was formed in Brooklyn, New York, in the United States by Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers in 1867. It became part of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil organization in 1874....

. In the next few years, Rogers became, in the words of Elbert Hubbard

Elbert Hubbard

Elbert Green Hubbard was an American writer, publisher, artist, and philosopher. Raised in Hudson, Illinois, he met early success as a traveling salesman with the Larkin soap company. Today Hubbard is mostly known as the founder of the Roycroft artisan community in East Aurora, New York, an...

, Pratt's "hands and feet and eyes and ears" (Little Journeys to the Homes, 1909). As their family grew, Henry and Abbie continued to live in New York City, but vacationed frequently at Fairhaven.

While working with Pratt, Rogers invented an improved way of separating naphtha

Naphtha

Naphtha normally refers to a number of different flammable liquid mixtures of hydrocarbons, i.e., a component of natural gas condensate or a distillation product from petroleum, coal tar or peat boiling in a certain range and containing certain hydrocarbons. It is a broad term covering among the...

, a light oil similar to kerosene

Kerosene

Kerosene, sometimes spelled kerosine in scientific and industrial usage, also known as paraffin or paraffin oil in the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Ireland and South Africa, is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid. The name is derived from Greek keros...

, from crude oil. He was granted U.S. Patent # 120,539 on October 31, 1871.

Fighting Rockefeller

In the early 1871-72, Pratt and Company and other refiners became involved in a conflict with John D. RockefellerJohn D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of...

, Samuel Andrews, and Henry M. Flagler (of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was a business concern formed in 1867 in Cleveland, Ohio which was a predecessor of the Standard Oil Company. The principals and namesakes were John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Samuel Andrews, and Henry M. Flagler. Flagler’s wife’s uncle, Stephen V...

, a Cleveland-based refining company) and the South Improvement Company

South Improvement Company

The South Improvement Company was a Pennsylvania corporation in 1871-1872. It was created by major railroad interests, but was widely seen as part of John D. Rockefeller's early efforts to organize and control the oil and natural gas industries in the United States which eventually became Standard...

. In developing what would become Standard Oil

Standard Oil

Standard Oil was a predominant American integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company. Established in 1870 as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world and operated as a major company trust and was one of the world's first and largest multinational...

, Rockefeller, a manager of extraordinary abilities, and Flagler, an exceptional marketer, recognized that the costs and control of the shipment of crude oil would be key elements in competition with other refiners. With its combination of clever market manipulation, and hard-nosed dealings with the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad was an American Class I railroad, founded in 1846. Commonly referred to as the "Pennsy", the PRR was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania....

(PRR), the South Improvement scheme was an example of the type of business tactics which Rockefeller and his associates used to become successful. Although Rockefeller became the target of many who decried Standard Oil's ruthlessness in subsequent years, the South Improvement rebate scheme was Flagler's idea.

South Improvement was basically a mechanism to obtain secret favorable net rates from Tom Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad was an American Class I railroad, founded in 1846. Commonly referred to as the "Pennsy", the PRR was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania....

(PRR) and other railroads through secret rebate

Rebate

Rebate can refer to:* Rebate or rabbet, a woodworking term for a groove* Film rebate, the term for the border around photographic film- Money :* Rebate , a type of sales promotion used in marketing* Tax rebate, a reduction in taxation demanded...

s from the common carrier

Common carrier

A common carrier in common-law countries is a person or company that transports goods or people for any person or company and that is responsible for any possible loss of the goods during transport...

. A "common carrier" is somewhat like a utility, inasmuch as it often has certain rights, powers and monopolies on its services beyond those normally afforded regular business enterprises. A common carrier was expected to serve the public good and treat its customers uniformly. Rates in that era were promulgated and published in what was called "tariffs" and were public information. The rebate scheme was done outside of that process.

Newspapers were quick to publicize the issue. The injustice of the South Improvement scheme outraged many independent oil producers and owners of refineries. Rogers led the opposition among the New York refiners. The New York interests formed an association, and about the middle of March 1872 sent a committee of three, with Rogers as head, to Oil City to consult with the Oil Producers' Union. Working with the Pennsylvania independents, Rogers and the New York delegation managed to forge an agreement with the railroads, whose leaders eventually agreed to open their rates to all and promised to end their shady dealings with South Improvement.

Rockefeller and his associates quickly started another approach, which frequently included buying-up opposing interests. Their dominance of the growing industry and the squeezing out of smaller competitors continued and expanded. But, the South Improvement incident prompted growing public sentiment to support governmental oversight and regulation of large businesses, including the railroads. Congress passed new antitrust laws, the administration created the Interstate Commerce Commission

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission was a regulatory body in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including...

(ICC), and the courts eventually ordered the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust in the early 20th century.

Combining forces: joining Standard Oil

In 1874, Rockefeller approached Pratt with a plan to cooperate and consolidate their businesses. Pratt discussed it with Rogers, and they decided that the combination would benefit them. Rogers formulated terms, which guaranteed financial security and jobs for Pratt and himself. Rockefeller had apparently learned a lot about Rogers' talents and negotiating skills during the South Improvement conflict. He quietly accepted the offer on the exact terms Rogers had laid out. In this manner, Charles Pratt and Company (including Astral Oil) became one of the important independent refiners to join the Standard Oil Trust.By this date, Charles Pratt was reaching an age to consider retirement, and he subsequently devoted much of his time and interests to activities such as founding the Pratt Institute. However, Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt

Charles Millard Pratt

Charles Millard Pratt was an American oil industrialist and philanthropist.-Early life:Pratt was born and raised in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, the eldest son of Charles Pratt and Lydia Ann Richardson....

(1858 to 1913), became Corporate Secretary of Standard Oil. As a part owner of Pratt and Company, Rogers, who was about 35 years old, now owned a share of Standard Oil himself. In the deal, Rockefeller had also added Henry Rogers to his team. He undoubtedly placed a high value on Rogers' potential. History does not tell us if he foresaw that the promising young man was destined to become one of his major partners.

Building Standard Oil with John D. Rockefeller

Standard Oil was an oil refining conglomerate. Its successors continued to be among the world's biggest corporations over 140 years later. John D. RockefellerJohn D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of...

, long regarded as the principal founder, was of a modest background and education. Born in New York in 1839, his family moved to Cleveland in 1855. His first job was as an assistant bookkeeper for a produce company. He delighted, as he later recalled, in "all the methods and systems of the office". He became particularly well-skilled at calculating transportation costs, a skill which would later serve him particularly well. He worked in variety of small business enterprises during the next few years, owning interests in several.

During this time, Rockefeller became friends with Henry Morrison Flagler. The two men had much in common, as they were each conservative, hard-working and energetic, and driven to make money. Their backgrounds included working separately for a number of years in various retail enterprises, including the grain business. Although teetotalers personally, distilled spirits were a byproduct of the handling of corn, and each embraced the business opportunity that presented; making money was clearly paramount.

Of their various separate forays into business, financial results for each had been mixed. Flagler, 9 years senior to Rockefeller, had been completely wiped out financially in a venture into salt. Only a loan from a relative, Stephen V. Harkness

Stephen V. Harkness

Stephen Vanderburgh Harkness was an American businessman from Cleveland, Ohio, who invested as a silent partner with oil titan John D. Rockefeller, Sr. in the founding of Standard Oil.-Biography:...

, allowed him to keep creditors at bay and stay out of total ruin.

In the second half of the 19th century, the United States began a transition from use of whale oil to petroleum for heating and lighting. Discovery of oil fields in western Pennsylvania in the late 1850s and the promise of increased industrial activity and economic growth after the end of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

combined to make the refining of crude oil seem an attractive business to Rockefeller. He and Flagler enlisted chemist Samuel Andrews and with his brother, William Rockefeller

William Rockefeller

William Avery Rockefeller, Jr. , American financier, was a co-founder with his older brother John D. Rockefeller of the prominent United States Rockefeller family. He was the son of William Avery Rockefeller, Sr. and Eliza Rockefeller.-Youth, education:Rockefeller was born in Richford, New York,...

, Jabez Bostwick

Jabez A. Bostwick

Jabez Abel Bostwick was an American businessman who was a founding partner of Standard Oil.-Biography:...

, and Flagler's relative and silent partner

Silent partner

Silent partner may refer to:*An anonymous member of a business partnership, or one uninvolved in management*The Silent Partner, the name of several films*Silent partner , a piece of climbing equipment...

, Stephen V. Harkness

Stephen V. Harkness

Stephen Vanderburgh Harkness was an American businessman from Cleveland, Ohio, who invested as a silent partner with oil titan John D. Rockefeller, Sr. in the founding of Standard Oil.-Biography:...

, went into the refining business in Cleveland as Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was a business concern formed in 1867 in Cleveland, Ohio which was a predecessor of the Standard Oil Company. The principals and namesakes were John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Samuel Andrews, and Henry M. Flagler. Flagler’s wife’s uncle, Stephen V...

.

By all accounts, Rockefeller was an extraordinarily talented manager and financial planner, Flagler was an exceptional marketer, and Andrews had the know-how to oversee refining aspects. It was to be a very successful combination. As the demand for kerosene and a new byproduct, gasoline, grew in the United States, by 1868, what was to become Standard Oil was the world's largest oil refinery.

In 1870, Rockefeller formed Standard Oil Company of Ohio

Standard Oil of Ohio

Standard Oil of Ohio or Sohio was an American oil company that was acquired by British Petroleum, now called BP.It was one of the successor companies to Standard Oil after the antitrust breakup in 1911. Standard Oil of Ohio was the original Standard Oil company founded by John D. Rockefeller. It...

and started his strategy of buying up the competition and consolidating all oil refining under one company. It was during this period that the Pratt interests and Henry Rogers were brought into the fold. By 1878 Standard Oil held about 90% of the refining capacity in the United States.

Flagler's wife was in failing health due to what was later determined to be tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

. On advice of her physician, he took her to Florida for the winter months beginning in 1877, and she did seem to improve with the gentle winter and cool ocean breezes there. While in Florida, Flagler was struck with the lack of good rail transportation south of Jacksonville

Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Florida in terms of both population and land area, and the largest city by area in the contiguous United States. It is the county seat of Duval County, with which the city government consolidated in 1968...

, the equally poor availability of good lodging, and the potential the impoverished state held as a vacation destination for northerners. Sensing a major business opportunity, he began to invest and become a major developer of Florida's east coast in what many regard as his "second career." However, his ventures in Florida marked the beginning of his gradual reduction in management participation at Standard Oil.

In 1881 the company was reorganized as the Standard Oil Trust. In 1885, the headquarters were relocated from Cleveland to New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. By this time, the three main men of Standard Oil Trust had become John D. Rockefeller, his brother William, and Henry Rogers, who had emerged as a key financial strategist. By 1890, Rogers was a vice president of Standard Oil and chairman of the organization's operating committee.

Oil and gas pipelines

Petroleum pipelinePipeline transport

Pipeline transport is the transportation of goods through a pipe. Most commonly, liquids and gases are sent, but pneumatic tubes that transport solid capsules using compressed air are also used....

s were first developed in Pennsylvania in the 1860s to replace transport in wooden barrels loaded on wagons drawn by mules and driven by teamster

Teamster

A teamster, in modern American English, is a truck driver. The trade union named after them is the International Brotherhood of Teamsters , one of the largest unions in the United States....

s. This mule-drawn transportation was expensive and fraught with difficulties: leaking barrels, muddy trails, wagon breakdowns and mule/driver problems.

The first successful metal pipeline was completed in 1865, when Samuel Van Syckel built a four-mile (6 km) pipeline from Pithole, Pennsylvania, to the nearest railroad. This initial success led to the construction of pipelines to connect crude oil production, increasingly moving west as new fields were discovered and Pennsylvania fields declined, to refineries located near major demand centers in the Northeast. Biographer Z. James Varanini writes, "the completion of these pipelines represented a move towards a new type of interconnectivity of previously isolated states."

When Rockefeller observed this, he began to acquire many of the new pipelines. Soon, his Standard Oil companies owned a majority of the lines, which provided cheap, efficient transportation for oil. Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Cuyahoga County, the most populous county in the state. The city is located in northeastern Ohio on the southern shore of Lake Erie, approximately west of the Pennsylvania border...

, became a center of the refining industry principally because of its transportation systems.

Rogers conceived the idea of long pipelines for transporting oil and natural gas

Natural gas

Natural gas is a naturally occurring gas mixture consisting primarily of methane, typically with 0–20% higher hydrocarbons . It is found associated with other hydrocarbon fuel, in coal beds, as methane clathrates, and is an important fuel source and a major feedstock for fertilizers.Most natural...

. In 1881, the National Transit Company was formed by Standard Oil to own and operate Standard's pipelines. The National Transit Company remained one of Rogers' favorite projects throughout the rest of his life.

East Ohio Gas Company (EOG) was incorporated on September 8, 1898, as a marketing company for the National Transit Company, the natural gas arm of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. The company launched its business by selling to consumers in northeast Ohio gas produced by another National Transit subsidiary, Hope Natural Gas Company.

Rubber-manufacturing city Akron, Ohio

Akron, Ohio

Akron , is the fifth largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Summit County. It is located in the Great Lakes region approximately south of Lake Erie along the Little Cuyahoga River. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 199,110. The Akron Metropolitan...

, was the first to take advantage of the lower prices for natural gas. It granted the East Ohio Gas Company a franchise in September 1898, the same month that the company was founded. During the winter of 1898–99, the National Transit Company built a 10-inch wrought iron

Wrought iron

thumb|The [[Eiffel tower]] is constructed from [[puddle iron]], a form of wrought ironWrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon...

pipeline that stretched from the Pipe Creek on the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

to Akron, with branches to Canton, Massillon, Dover, New Philadelphia, Uhrichsville, and Dennison. The first gas from the pipeline burned in Akron on May 10, 1899.

Steel

Andrew CarnegieAndrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-American industrialist, businessman, and entrepreneur who led the enormous expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century...

, long the leading steel magnate of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh is the second-largest city in the US Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Allegheny County. Regionally, it anchors the largest urban area of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley, and nationally, it is the 22nd-largest urban area in the United States...

, retired at the turn of the 20th century, and refocused his interests on philanthropy. His steel holdings were consolidated into the new United States Steel Corporation. Standard Oil's interest in steel properties led to Rogers' becoming one of the directors when it was organized in 1901.

Regulating Standard Oil: Ida M. Tarbell

In 1890 the U.S. Congress passed Sherman Antitrust ActSherman Antitrust Act