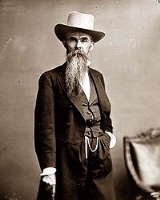

William Mahone

Encyclopedia

William Mahone was a civil engineer

, teacher

, soldier

, railroad executive, and a member of the Virginia General Assembly

and U.S. Congress. Small of stature, he was nicknamed "Little Billy".

Educated at Virginia Military Institute

, Mahone helped build Virginia's roads and railroads in the antebellum period. In 1855, he married the former Otelia Voinard Butler

of Smithfield

. Local tradition notes that they were each colorful characters. Based upon Ivanhoe

, a novel she had been reading, the naming of several railroad towns in Southside Virginia is credited to Otelia and "Little Billy". The name of Disputanta

was allegedly created after the couple had a "dispute" over an appropriate name.

During the American Civil War

, as a leader eventually attaining the rank of major general of the Confederate States Army

, Mahone is best known for turning the tide of the Battle of the Crater

against the Union

advance during the Siege of Petersburg

in 1864. His wife served as a nurse in Richmond. Although the Mahone family had owned several slaves before the war, biographer Nelson Blake has noted that during the War and after, Mahone accorded the African Americans under his leadership and generally with considerably more respect than many of his peers. Still, many African American leaders complained that Mahone was relegating them to the lower rung political positions, and he was affected by public sentiments against African Americans. To elevate them could diminish his white support and needed both public and white support.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, he returned to his pre-war position heading the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

, working to rebuild it, and the two trunk lines west of Petersburg to Bristol, Virginia

, at the Tennessee border. He successfully united the three in 1870 to form the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad

(AM&O), which was headquartered in Lynchburg

. As he and Otelia made their home there, the pundits were already claiming that AM&O really stood for "All Mine and Otelia's".

Even while still serving in the Confederate Army, Mahone had also become involved in politics. In the post-war years, he helped form and lead a coalition of blacks, Republicans, and Conservative Democrats that became known as the Readjuster Party

(so-named for a position regarding Virginia's troublesome post-War public debt issues). Partially owned by the state, the AM&O went into receivership several years after the Financial Panic of 1873

. When it was sold to northern interests who formed the Norfolk and Western (N&W) in 1881, Mahone working with African American members of the Readjuster Party helped arrange for a portion of the proceeds to be used to fund a teacher's school

and collegiate institute to educate Virginia's large African American population, now known as Virginia State University

, and also to build a mental hospital for blacks nearby, long known as Central State Hospital

.

Mahone's hand-picked candidate, William E. Cameron, won the election as Governor of Virginia

as a Readjuster, and Mahone himself subsequently won a term as a U.S. Senator. With his status as an independent, he held an important swing vote in the evenly divided upper house in the U.S. Congress, which became especially important after the assassination of President James A Garfield. However, he tended to caucus with the Republicans, and was defeated for reelection by the candidate of Virginia's Conservative Democrats, who were also assuming the other political control in Virginia they would later hold until the 1960s under the Byrd Organization

.

Despite eventually losing control of both the AM&O railroad and the political power that went with the Readjuster Party, Mahone accumulated substantial wealth, partially through the foresight of valuable personal investments in bituminous coal

lands in the western regions of Virginia where he had hoped to extend the AM&O. When Mahone died in 1895, followed by his widow Otelia in 1911, they were each interred with other family members in Petersburg's Blandford Cemetery

. Their former residence formed a portion of a new Petersburg Public Library.

, to Fielding Jordan Mahone and Martha (née Drew) Mahone. Beginning with the immigration of his Mahone ancestors from Ireland

, he was the third individual to be called "William Mahone." He did not have a middle name as shown by records including his two Bibles, VMI Diploma, marriage license, and Confederate Army commissions. Likewise, the General and Otelia's first born son was christened William Mahone. The suffix "Jr." was added to his name later in his life, during a period of similar cultural naming transitions in Virginia.

The little town of Monroe was on the banks of the Nottoway River

about eight miles south of the county seat

at Jerusalem, a town which was renamed Courtland

in 1888. The river was an important transportation artery in the years before railroads and later highways served the area. Fielding Mahone ran a store at Monroe and owned considerable farmland. The family narrowly escaped the massacre of local whites during Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831.

The local shift of transportation in the area was from the river to the new technology emerging with railroads in the 1830s. In 1840, when William was 14 years old, the family moved to Jerusalem, where Fielding Mahone purchased and operated a tavern. As recounted by his biographer, Nelson Blake, the freckled-faced youth of Irish-American heritage gained a reputation in the small town for both "gambling and a prolific use of tobacco and profanity."

Young Billy Mahone gained his primary education from a country schoolmaster but with special instruction in mathematics from his father. As a teenager, for a short time, he transported the U. S. Mail by horseback from his hometown to Hicksford, a small town on the south bank of the Meherrin River

in Greensville County

which later combined with the town of Belfield on the north bank to form the current independent city

of Emporia

. He was awarded a spot as a state cadet at the recently opened Virginia Military Institute

(VMI) in Lexington, Virginia

. Studying under VMI Commandant William Gilham

and a professor named Thomas J. Jackson

, he graduated with a degree as a civil engineer

in the Class of 1847.

, beginning in 1848, but was actively seeking an entry into civil engineering. He did some work helping locate the Orange and Alexandria Railroad

, an 88-mile line between Gordonsville, Virginia

, and the City of Alexandria

. Having performed well with the new railroad, was hired to build a plank road

between Fredericksburg

and Gordonsville.

On April 12, 1853, he was hired by Dr. Francis Mallory

of Norfolk

, as chief engineer to build the new Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

(N&P). Mahone's innovative 12 mile-long roadbed through the Great Dismal Swamp

between South Norfolk

and Suffolk

employed a log foundation laid at right angles beneath the surface of the swamp. Still in use 150 years later, Mahone's corduroy

design withstands immense tonnages of modern coal

traffic. He was also responsible for engineering and building the famous 52 mile-long tangent

track between Suffolk

and Petersburg

. With no curves, it is a major artery of modern Norfolk Southern rail traffic.

In 1854, Mahone surveyed and laid out with streets and lots of Ocean View City, a new resort town fronting on the Chesapeake Bay

in Norfolk County

. With the advent of electric streetcars in the late 19th century, an amusement park

was developed there and a boardwalk

was built along the adjacent beach

area. Most of Mahone's street plan is still in use in the 21st century as Ocean View, now a section of the City of Norfolk, is redeveloped.

He was surveyor for the Norfolk and South Air Line Railroad, on the Eastern Shore

of Virginia.

On February 8, 1855, Mahone married Otelia Butler (1835 – 1911), the daughter the late Dr. Robert Butler from Smithfield

, who had been State Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Virginia from 1846 until his death in 1853. Her mother was Butler's second wife, Otelia Voinard Butler (1803–1855), originally from Petersburg

.

Young Otelia Butler is said to have been a cultured lady. She and William settled in Norfolk, where they lived for most of the years before the Civil War. They had 13 children, but only 3 survived to adulthood, two sons, William Jr.

and Robert, and a daughter, also named Otelia

.

The Mahone family escaped the yellow fever

epidemic that broke out in the summer of 1855 and killed almost a third of the populations of Norfolk and Portsmouth

by staying with his mother some distance away in Jerusalem. However, as a consequence of the epidemic, the decimated citizenry of the Norfolk area had difficulty in meeting financial obligations, and work on their new railroad to Petersburg almost came to a standstill. Ever frugal, Mahone and his mentor

, Dr. Mallory, nevertheless pushed the project to completion.

Popular legend has it that Otelia and William Mahone traveled along the newly completed railroad naming stations from Ivanhoe and other books she was reading written by Sir Walter Scott

. From his historical Scottish novels, she chose the place names of Windsor

, Waverly

, and Wakefield

. She tapped the Scottish Clan "McIvor" for the name of Ivor

, a small Southampton County

town. When they reached a location where they could not agree, it is said that the name Disputanta

was created. The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was completed in 1858, and Mahone was named its president a short time later.

According to some records, in 1860, Mahone owned 7 slaves

, all black

: 3 male (ages 13, 4, 2), 4 female (ages 45, 24, 11, 1). Nevertheless, during the Civil War and after, he showed an empathy for former slaves that was atypical for the times, and worked diligently for their fair treatment and education.

As the political differences between Northern

As the political differences between Northern

and Southern

factions escalated in the second half of the 19th century, Mahone was in favor of secession

of the Southern states. During the American Civil War

, he was active in the actual conflict even before he became an officer in the Confederate Army. Early in the War, in 1861, his Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

was especially valuable to the Confederacy and transported ordnance to the Norfolk area where it was used during the Confederate occupation. By the end of the war, most of what was left of the railroad was in Federal hands.

After Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861, Mahone was still a civilian, and not yet in the Confederate Army, but working in coordination with Walter Gwynn

, he orchestrated the ruse and capture of the Gosport Shipyard

. He bluffed the Federal troops into abandoning the shipyard in Portsmouth by running a single passenger train into Norfolk with great noise and whistle-blowing, then much more quietly, sending it back west, and then returning the same train again, creating the illusion of large numbers of arriving troops to the Federals listening in Portsmouth across the Elizabeth River

(and just barely out of sight). The ruse

worked, and not a single Confederate soldier was lost as the Union authorities abandoned the area, and retreated to Fort Monroe

across Hampton Roads

. After this, Mahone accepted a commission as lieutenant colonel

and later colonel

of the 6th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment

in the Confederate Army. He commanded the Confederate's Norfolk district until its evacuation. He was promoted to brigadier general in November 1861.

In May 1862, after the evacuation of Norfolk by Southern forces during the Peninsula Campaign

, he aided in the construction of the defenses of Richmond on the James River

around Drewry's Bluff

. A short time later, he led his brigade at the Battle of Seven Pines

, and the Battle of Malvern Hill

. He also fought at Second Bull Run

, Fredericksburg

, Chancellorsville

, Gettysburg

, the Wilderness

, and Spotsylvania Court House

.

Small of stature, 5 foot 5 or 6 inches, and weighing only 100 lb (45 kg), he was nicknamed "Little Billy". As one of his soldiers put it, "He was every inch a soldier, though there were not many inches of him." Otelia Mahone was working in Richmond as a nurse, when Virginia Governor John Letcher

sent word that Mahone had been injured at Second Bull Run, but had only received a "flesh wound." She is said to have replied "Now I know it is serious for William has no flesh whatsoever."

Although his wound at Manassas

had not been serious, Mahone did suffer from acute dyspepsia

all of his life. During the War, a cow and chickens accompanied him in order to provide dairy products. Otelia and their children moved to Petersburg to be near him during the final campaign of the War in 1864-65 as Grant moved against Petersburg, seeking to sever the rail lines supplying the Confederate capital of Richmond.

It was during that final campaign that William Mahone became widely regarded as the hero of the Battle of the Crater

on July 30, 1864. During the Siege of Petersburg

of 1864–65, former Pennsylvania

coal miners in the Union Army tunneled under the Confederate line and blew it up in a massive explosion, killing and wounding many Confederates and breaching a key point in the defense line around Petersburg. However, they lost their initial advantage and Mahone rallied the remaining Confederate forces nearby, repelling the attack. After beginning as an innovative initiative, the Crater scheme turned into a terrible loss for the Union leaders. The quick and effective action led by Mahone was a rare cause for celebration by the occupants of Petersburg, embattled citizens and weary troops alike. "Little Billy" Mahone was promoted to major general as a result.

However, Grant's strategy at Petersburg eventually succeeded as the last rail line from the south to supply the Cockcade City (and hence Richmond) was severed in early April 1865. Mahone was with Gen. Robert E. Lee

and the Army of Northern Virginia

for the surrender at Appomattox Court House

about a week later. Dr. Douglas Southall Freeman, noted biographer of Robert E. Lee, wrote that, after the surrender, Lee instructed his lieutenants: "Go home and start rebuilding."

. He was president of all three by the end of 1867. During the post-war Reconstruction period, he worked diligently lobbying the Virginia General Assembly

to gain the legislation necessary to form the Atlantic, Mississippi & Ohio Railroad (AM&O), a new line comprising the three railroads he headed, extending 408 miles from Norfolk to Bristol, Virginia

, in 1870.

This conflicted with the expansion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

from Baltimore.

The Mahones were colorful characters: the letters A, M & O were said to stand for "All Mine and Otelia's".

They lived in Lynchburg, Virginia

, during this time, but moved back to Petersburg

in 1872.

The Financial Panic of 1873

put the A,M & O into conflict with its bondholders in England and Scotland. After several years of operating under receiverships, Mahone's relationship with the creditors soured, and an alternate receiver, Henry Fink, was appointed to oversee the A,M & O's finances. Mahone still worked to regain control, but his role as a railroad builder ended, in 1881, when Philadelphia-based interests outbid him and purchased the A,M & O at auction, renaming it Norfolk and Western (N&W).

Before the Civil War, the Virginia Board of Public Works

had invested state funds in a substantial portion of the stock of the A,M & O's predecessor railroads. Although he lost control of the railroad, as a major political leader in Virginia, Mahone was able to arrange for a portion of the State's proceeds of the sale to be directed to help found a school to prepare teachers to help educate black children and former slaves near his home at Petersburg, where he had earlier been mayor. The Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute eventually expanded to become Virginia State University

. He also directed another portion of the funds to help found the predecessor of today's Central State Hospital

in Dinwiddie County

, also located adjacent to Petersburg. Mahone personally retained his ownership of land investments which were linked to the N&W's development of the rich coal

fields of western Virginia and southern West Virginia

, contributing to his rank as one of Virginia's wealthiest men at his death, according to his biographer, author Nelson Blake.

William Mahone was active in the economic and political life of Virginia for almost 30 years, beginning in the midst of the Civil War when he was elected to the Virginia General Assembly

William Mahone was active in the economic and political life of Virginia for almost 30 years, beginning in the midst of the Civil War when he was elected to the Virginia General Assembly

as a Delegate from Norfolk in 1863. He later served as mayor of Petersburg

. After his unsuccessful bid for governor in 1877, he became the leader of the Readjuster Party

, a coalition of Democrats, Republicans

, and African-Americans seeking a reduction in Virginia's prewar debt, and an appropriate allocation made to the former portion of the state that constituted the new State of West Virginia

. In 1881, Mahone led the successful effort to elect the Readjuster candidate William E. Cameron as the next governor, and he himself as a United States Senator.

At the Congressional level, with a 37-37 split between Republicans and Democrats in the Senate and with a second third-party candidate willing to caucus with the latter, Mahone's affiliation would determine which party would control the Senate, since under Senate rules, Vice President of the United States

Chester A. Arthur

, a Republican, would cast any tie-breaking votes. Mahone's eventual decision to caucus with the Republicans came at a high price to them. Despite being a freshman senator, he received chairmanship of the influential Agriculture Committee and gained control over Virginia's federal patronage, both from President James A. Garfield, and by the right to select both the Senate's Secretary and Sergeant at Arms.

Once affiliated with the Republican Party, Mahone led Virginia delegations to the Republican National Conventions of 1884 and 1888. However, he lost his Senate seat to Conservative Democrat John W. Daniel

in 1886. In 1889, he ran for governor on a Republican ticket, but lost to Democrat Philip W. McKinney

. It was to be 80 more years before Virginia sent another non-Democrat to the Governor's Mansion (Republican A. Linwood Holton Jr.

in 1969). Although out of office, the seemingly tireless Mahone continued to stay involved in Virginia-related politics until he suffered a catastrophic stroke

in Washington, D.C.

, in the fall of 1895. He died a week later, aged 68. His widow, Otelia, lived on in Petersburg until her own death in 1911.

Although Mahone was not to live to see the outcome, for several decades, Virginia and West Virginia disputed the new state's share of the Virginia government's debt. The issue was finally settled in 1915, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that West Virginia owed Virginia $12,393,929.50. The final installment of this sum was paid off in 1939.

William Mahone was interred in the family mausoleum in Blandford Cemetery

William Mahone was interred in the family mausoleum in Blandford Cemetery

in Petersburg, Virginia

. His widow, Otelia, lived until 1911, and was interred alongside him. The mausoleum is identified by the General's well known monogram, the initial "M" centered on a star inside a shield.

Otelia and William Mahone's first home in Petersburg, originally occupied by John Dodson, Petersburg's mayor in 1851-2, was on South Sycamore St. That structure now serves as part of the Petersburg Public Library. In 1874, they acquired and greatly enlarged a home on South Market St. and it was their primary residence thereafter. Virginia State University

, which he helped found as a normal school

, is a major community presence nearby.

A large portion of U.S. Highway 460 in eastern Virginia (between Petersburg

and Suffolk

) parallels the 52-mile tangent railroad tracks that Mahone had engineered, passing through some of the towns he and Otelia are believed to have named. Several sections of the road are labeled "General Mahone Boulevard" and "General Mahone Highway" in his honor. A monument to Mahone's Brigade is located on the Gettysburg Battlefield

.

The site of the Battle of the Crater

is a major feature of the National Park Service

's Petersburg National Battlefield Park. In 1927, the United Daughters of the Confederacy

erected an imposing monument to his memory. It stands on the preserved Crater Battlefield, a short distance from the Crater itself. The monument states:

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

, teacher

Teacher

A teacher or schoolteacher is a person who provides education for pupils and students . The role of teacher is often formal and ongoing, carried out at a school or other place of formal education. In many countries, a person who wishes to become a teacher must first obtain specified professional...

, soldier

Soldier

A soldier is a member of the land component of national armed forces; whereas a soldier hired for service in a foreign army would be termed a mercenary...

, railroad executive, and a member of the Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

and U.S. Congress. Small of stature, he was nicknamed "Little Billy".

Educated at Virginia Military Institute

Virginia Military Institute

The Virginia Military Institute , located in Lexington, Virginia, is the oldest state-supported military college and one of six senior military colleges in the United States. Unlike any other military college in the United States—and in keeping with its founding principles—all VMI students are...

, Mahone helped build Virginia's roads and railroads in the antebellum period. In 1855, he married the former Otelia Voinard Butler

Otelia B. Mahone

Otelia Butler Mahone from Smithfield, Virginia was a nurse during the American Civil War and the wife of Confederate Major General William Mahone, who was a civil engineer, teacher, railroad builder, and Senator in the United States Congress...

of Smithfield

Smithfield, Virginia

Smithfield is a town in Isle of Wight County, in the South Hampton Roads subregion of the Hampton Roads region of Virginia in the United States. The population was 8,089 at the 2010 census....

. Local tradition notes that they were each colorful characters. Based upon Ivanhoe

Ivanhoe

Ivanhoe is a historical fiction novel by Sir Walter Scott in 1819, and set in 12th-century England. Ivanhoe is sometimes credited for increasing interest in Romanticism and Medievalism; John Henry Newman claimed Scott "had first turned men's minds in the direction of the middle ages," while...

, a novel she had been reading, the naming of several railroad towns in Southside Virginia is credited to Otelia and "Little Billy". The name of Disputanta

Disputanta, Virginia

Disputanta is an unincorporated community in Prince George County, Virginia, United States in the Richmond-Petersburg region and is a portion of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area...

was allegedly created after the couple had a "dispute" over an appropriate name.

During the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, as a leader eventually attaining the rank of major general of the Confederate States Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

, Mahone is best known for turning the tide of the Battle of the Crater

Battle of the Crater

The Battle of the Crater was a battle of the American Civil War, part of the Siege of Petersburg. It took place on July 30, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee and the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Major General George G. Meade The...

against the Union

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

advance during the Siege of Petersburg

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg Campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War...

in 1864. His wife served as a nurse in Richmond. Although the Mahone family had owned several slaves before the war, biographer Nelson Blake has noted that during the War and after, Mahone accorded the African Americans under his leadership and generally with considerably more respect than many of his peers. Still, many African American leaders complained that Mahone was relegating them to the lower rung political positions, and he was affected by public sentiments against African Americans. To elevate them could diminish his white support and needed both public and white support.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, he returned to his pre-war position heading the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was built between Norfolk and Petersburg, Virginia and was completed by 1858.It played a role on the American Civil War , and became part of the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad in 1870. The AM&O became the Norfolk and Western in 1881...

, working to rebuild it, and the two trunk lines west of Petersburg to Bristol, Virginia

Bristol, Virginia

Bristol is an independent city in Virginia, United States, bounded by Washington County, Virginia, Bristol, Tennessee, and Sullivan County, Tennessee....

, at the Tennessee border. He successfully united the three in 1870 to form the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad

Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad

Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad was formed in 1870 in Virginia from 3 east-west railroads which traversed across the southern portion of the state. Organized and led by former Confederate general William Mahone , the 428-mile line linked Norfolk with Bristol, Virginia by way of Suffolk,...

(AM&O), which was headquartered in Lynchburg

Lynchburg, Virginia

Lynchburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 75,568 as of 2010. Located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains along the banks of the James River, Lynchburg is known as the "City of Seven Hills" or "The Hill City." Lynchburg was the only major city in...

. As he and Otelia made their home there, the pundits were already claiming that AM&O really stood for "All Mine and Otelia's".

Even while still serving in the Confederate Army, Mahone had also become involved in politics. In the post-war years, he helped form and lead a coalition of blacks, Republicans, and Conservative Democrats that became known as the Readjuster Party

Readjuster Party

The Readjuster Party was a political coalition formed in Virginia in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the American Civil War. Readjusters aspired "to break the power of wealth and established privilege" and to promote public education, a program which attracted biracial support....

(so-named for a position regarding Virginia's troublesome post-War public debt issues). Partially owned by the state, the AM&O went into receivership several years after the Financial Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

. When it was sold to northern interests who formed the Norfolk and Western (N&W) in 1881, Mahone working with African American members of the Readjuster Party helped arrange for a portion of the proceeds to be used to fund a teacher's school

Normal school

A normal school is a school created to train high school graduates to be teachers. Its purpose is to establish teaching standards or norms, hence its name...

and collegiate institute to educate Virginia's large African American population, now known as Virginia State University

Virginia State University

Virginia State University is a historically black and land-grant university located north of the Appomattox River in Chesterfield, in the Richmond area. Founded on , Virginia State was the United States's first fully state-supported four-year institution of higher learning for black Americans...

, and also to build a mental hospital for blacks nearby, long known as Central State Hospital

Central State Hospital (Virginia)

Central State Hospital is an institution for mentally handicapped adults near Dinwiddie, Virginia. It is supported and administered by the Virginia Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation, and Substance Abuse Services. It was established in 1870....

.

Mahone's hand-picked candidate, William E. Cameron, won the election as Governor of Virginia

Governor of Virginia

The governor of Virginia serves as the chief executive of the Commonwealth of Virginia for a four-year term. The position is currently held by Republican Bob McDonnell, who was inaugurated on January 16, 2010, as the 71st governor of Virginia....

as a Readjuster, and Mahone himself subsequently won a term as a U.S. Senator. With his status as an independent, he held an important swing vote in the evenly divided upper house in the U.S. Congress, which became especially important after the assassination of President James A Garfield. However, he tended to caucus with the Republicans, and was defeated for reelection by the candidate of Virginia's Conservative Democrats, who were also assuming the other political control in Virginia they would later hold until the 1960s under the Byrd Organization

Byrd Organization

The Byrd Organization was a political machine led by former Governor and U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. that dominated Virginia politics for much of the middle portion of the 20th century...

.

Despite eventually losing control of both the AM&O railroad and the political power that went with the Readjuster Party, Mahone accumulated substantial wealth, partially through the foresight of valuable personal investments in bituminous coal

Bituminous coal

Bituminous coal or black coal is a relatively soft coal containing a tarlike substance called bitumen. It is of higher quality than lignite coal but of poorer quality than Anthracite...

lands in the western regions of Virginia where he had hoped to extend the AM&O. When Mahone died in 1895, followed by his widow Otelia in 1911, they were each interred with other family members in Petersburg's Blandford Cemetery

Blandford Cemetery

Blandford Cemetery is located in Petersburg, Virginia, USA. The oldest stone, marking the grave of Richard Yarbrough, reads 1702. Veterans of six wars are buried there, including 30,000 Confederates killed in the Siege of Petersburg during the American Civil War.In 1866, Blandford Cemetery was the...

. Their former residence formed a portion of a new Petersburg Public Library.

Childhood, education

William Mahone was born in Monroe in Southampton County, VirginiaSouthampton County, Virginia

As of the census of 2010, there were 18,570 people, 6,279 households, and 4,502 families residing in the county. The population density was 29 people per square mile . There were 7,058 housing units at an average density of 12 per square mile...

, to Fielding Jordan Mahone and Martha (née Drew) Mahone. Beginning with the immigration of his Mahone ancestors from Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

, he was the third individual to be called "William Mahone." He did not have a middle name as shown by records including his two Bibles, VMI Diploma, marriage license, and Confederate Army commissions. Likewise, the General and Otelia's first born son was christened William Mahone. The suffix "Jr." was added to his name later in his life, during a period of similar cultural naming transitions in Virginia.

The little town of Monroe was on the banks of the Nottoway River

Nottoway River

The Nottoway River is in southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. It is part of the Chowan River system, which flows into Albemarle Sound in North Carolina.-Cities and towns:Cities and towns along the river include:* Courtland, Virginia...

about eight miles south of the county seat

County seat

A county seat is an administrative center, or seat of government, for a county or civil parish. The term is primarily used in the United States....

at Jerusalem, a town which was renamed Courtland

Courtland, Virginia

Courtland is an incorporated town in Southampton County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,270 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Southampton County....

in 1888. The river was an important transportation artery in the years before railroads and later highways served the area. Fielding Mahone ran a store at Monroe and owned considerable farmland. The family narrowly escaped the massacre of local whites during Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831.

The local shift of transportation in the area was from the river to the new technology emerging with railroads in the 1830s. In 1840, when William was 14 years old, the family moved to Jerusalem, where Fielding Mahone purchased and operated a tavern. As recounted by his biographer, Nelson Blake, the freckled-faced youth of Irish-American heritage gained a reputation in the small town for both "gambling and a prolific use of tobacco and profanity."

Young Billy Mahone gained his primary education from a country schoolmaster but with special instruction in mathematics from his father. As a teenager, for a short time, he transported the U. S. Mail by horseback from his hometown to Hicksford, a small town on the south bank of the Meherrin River

Meherrin River

The Meherrin River is a long river in the U.S. states of Virginia and North Carolina. It begins in central Virginia, about northwest of Emporia, and flows roughly east-southeast into North Carolina, where it joins the larger Chowan River....

in Greensville County

Greensville County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 11,560 people, 3,375 households, and 2,396 families residing in the county. The population density was 39 people per square mile . There were 3,765 housing units at an average density of 13 per square mile...

which later combined with the town of Belfield on the north bank to form the current independent city

Independent city

An independent city is a city that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity. These type of cities should not be confused with city-states , which are fully sovereign cities that are not part of any other sovereign state.-Historical precursors:In the Holy Roman Empire,...

of Emporia

Emporia, Virginia

Emporia is an independent city located within the confines of Greensville County, Virginia, United States. The population was estimated to be 5,927 in 2010. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Emporia with surrounding Greensville county for statistical purposes...

. He was awarded a spot as a state cadet at the recently opened Virginia Military Institute

Virginia Military Institute

The Virginia Military Institute , located in Lexington, Virginia, is the oldest state-supported military college and one of six senior military colleges in the United States. Unlike any other military college in the United States—and in keeping with its founding principles—all VMI students are...

(VMI) in Lexington, Virginia

Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an independent city within the confines of Rockbridge County in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 7,042 in 2010. Lexington is about 55 minutes east of the West Virginia border and is about 50 miles north of Roanoke, Virginia. It was first settled in 1777.It is home to...

. Studying under VMI Commandant William Gilham

William Gilham

William Henry Gilham was an American soldier, teacher, chemist, and author. A member of the faculty at Virginia Military Institute, in 1860, he wrote a military manual which was still in modern use 145 years later...

and a professor named Thomas J. Jackson

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

, he graduated with a degree as a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

in the Class of 1847.

Civil engineer, railroad builder, family

Mahone worked as a teacher at Rappahannock Academy in Caroline County, VirginiaCaroline County, Virginia

Caroline County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 28,545. Its county seat is Bowling Green. Caroline County is also home to The Meadow stables, the birthplace of the renowned racehorse Secretariat, winner of the 1973 Kentucky Derby, Preakness and...

, beginning in 1848, but was actively seeking an entry into civil engineering. He did some work helping locate the Orange and Alexandria Railroad

Orange and Alexandria Railroad

The Orange and Alexandria Railroad was an intrastate railroad in Virginia, United States. It extended from Alexandria to Gordonsville, with another section from Charlottesville to Lynchburg...

, an 88-mile line between Gordonsville, Virginia

Gordonsville, Virginia

Gordonsville is a town in Louisa and Orange counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 1,496 at the 2010 census.-History:Nathaniel Gordon purchased in 1787 and in 1794, or possibly earlier, applied for and was granted a license to operate a tavern...

, and the City of Alexandria

Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2009, the city had a total population of 139,966. Located along the Western bank of the Potomac River, Alexandria is approximately six miles south of downtown Washington, D.C.Like the rest of northern Virginia, as well as...

. Having performed well with the new railroad, was hired to build a plank road

Plank road

A plank road or puncheon is a dirt path or road covered with a series of planks, similar to the wooden sidewalks one would see in a Western movie. Plank roads were very popular in Ontario, the U.S. Northeast and U.S. Midwest in the first half of the 19th century...

between Fredericksburg

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia located south of Washington, D.C., and north of Richmond. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 24,286...

and Gordonsville.

On April 12, 1853, he was hired by Dr. Francis Mallory

Francis Mallory

Francis Mallory was an American naval officer, physician, politician, and railroad executive.-Biography:...

of Norfolk

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

, as chief engineer to build the new Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was built between Norfolk and Petersburg, Virginia and was completed by 1858.It played a role on the American Civil War , and became part of the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad in 1870. The AM&O became the Norfolk and Western in 1881...

(N&P). Mahone's innovative 12 mile-long roadbed through the Great Dismal Swamp

Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp is a marshy area on the Coastal Plain Region of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina in the United States. It is located in parts of southern Chesapeake and Suffolk in Virginia, as well as northern...

between South Norfolk

South Norfolk, Virginia

South Norfolk was an independent city in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia and is now a section of the City of Chesapeake, one of the cities of Hampton Roads which surround the harbor of Hampton Roads and are linked by the Hampton Roads Beltway.-History:Located a few miles south of...

and Suffolk

Suffolk, Virginia

Suffolk is the largest city by area in Virginia, United States, and is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 84,585. Its median household income was $57,546.-History:...

employed a log foundation laid at right angles beneath the surface of the swamp. Still in use 150 years later, Mahone's corduroy

Corduroy road

A corduroy road or log road is a type of road made by placing sand-covered logs perpendicular to the direction of the road over a low or swampy area....

design withstands immense tonnages of modern coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

traffic. He was also responsible for engineering and building the famous 52 mile-long tangent

Tangent

In geometry, the tangent line to a plane curve at a given point is the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. More precisely, a straight line is said to be a tangent of a curve at a point on the curve if the line passes through the point on the curve and has slope where f...

track between Suffolk

Suffolk, Virginia

Suffolk is the largest city by area in Virginia, United States, and is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 84,585. Its median household income was $57,546.-History:...

and Petersburg

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

. With no curves, it is a major artery of modern Norfolk Southern rail traffic.

In 1854, Mahone surveyed and laid out with streets and lots of Ocean View City, a new resort town fronting on the Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

in Norfolk County

Norfolk County, Virginia

Norfolk County was a county of the South Hampton Roads in eastern Virginia in the United States that was created in 1691. After the American Civil War, for a period of about 100 years, portions of Norfolk County were lost and the territory of the county reduced as they became parts of the separate...

. With the advent of electric streetcars in the late 19th century, an amusement park

Amusement park

thumb|Cinderella Castle in [[Magic Kingdom]], [[Disney World]]Amusement and theme parks are terms for a group of entertainment attractions and rides and other events in a location for the enjoyment of large numbers of people...

was developed there and a boardwalk

Boardwalk

A boardwalk, in the conventional sense, is a wooden walkway for pedestrians and sometimes vehicles, often found along beaches, but they are also common as paths through wetlands, coastal dunes, and other sensitive environments....

was built along the adjacent beach

Beach

A beach is a geological landform along the shoreline of an ocean, sea, lake or river. It usually consists of loose particles which are often composed of rock, such as sand, gravel, shingle, pebbles or cobblestones...

area. Most of Mahone's street plan is still in use in the 21st century as Ocean View, now a section of the City of Norfolk, is redeveloped.

He was surveyor for the Norfolk and South Air Line Railroad, on the Eastern Shore

Eastern Shore

Eastern Shore refers to many places, including:* Eastern Shore of Maryland* Eastern Shore of Virginia* Eastern Shore * Eastern Shore , of Mobile BayOther uses, a United States Navy cargo ship in commission from 1918 to 1919...

of Virginia.

On February 8, 1855, Mahone married Otelia Butler (1835 – 1911), the daughter the late Dr. Robert Butler from Smithfield

Smithfield, Virginia

Smithfield is a town in Isle of Wight County, in the South Hampton Roads subregion of the Hampton Roads region of Virginia in the United States. The population was 8,089 at the 2010 census....

, who had been State Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Virginia from 1846 until his death in 1853. Her mother was Butler's second wife, Otelia Voinard Butler (1803–1855), originally from Petersburg

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

.

Young Otelia Butler is said to have been a cultured lady. She and William settled in Norfolk, where they lived for most of the years before the Civil War. They had 13 children, but only 3 survived to adulthood, two sons, William Jr.

William T. Mahone Jr.

William Mahone Jr., also known as Master Willie Mahone, was a businessman and government official.He was the son of Otelia Mahone and Confederate General and United States Senator William Mahone...

and Robert, and a daughter, also named Otelia

Otelia M. McGill

Otelia McGill of Petersburg, Virginia was the daughter of Otelia Mahone and Confederate General and United States Senator William Mahone....

.

The Mahone family escaped the yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

epidemic that broke out in the summer of 1855 and killed almost a third of the populations of Norfolk and Portsmouth

Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of the U.S. Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the city had a total population of 95,535.The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard, is a historic and active U.S...

by staying with his mother some distance away in Jerusalem. However, as a consequence of the epidemic, the decimated citizenry of the Norfolk area had difficulty in meeting financial obligations, and work on their new railroad to Petersburg almost came to a standstill. Ever frugal, Mahone and his mentor

Mentor

In Greek mythology, Mentor was the son of Alcimus or Anchialus. In his old age Mentor was a friend of Odysseus who placed Mentor and Odysseus' foster-brother Eumaeus in charge of his son Telemachus, and of Odysseus' palace, when Odysseus left for the Trojan War.When Athena visited Telemachus she...

, Dr. Mallory, nevertheless pushed the project to completion.

Popular legend has it that Otelia and William Mahone traveled along the newly completed railroad naming stations from Ivanhoe and other books she was reading written by Sir Walter Scott

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright, and poet, popular throughout much of the world during his time....

. From his historical Scottish novels, she chose the place names of Windsor

Windsor, Virginia

Windsor is an incorporated town in Isle of Wight County in the Hampton Roads region of southeastern Virginia in the United States. It is located near the crossroads of U.S. Route 460 and U.S. Route 258. The population was 916 at the 2000 census...

, Waverly

Waverly, Virginia

Waverly is an incorporated town in Sussex County, Virginia, United States. The population was 2,309 at the 2000 census.-History:Popular legend has it that William Mahone , builder of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad , and his cultured wife, Otelia Butler Mahone , traveled along the newly...

, and Wakefield

Wakefield, Virginia

Wakefield is an incorporated town in Sussex County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,038 at the 2000 census.Wakefield is famous for being the "Peanut Capital of the World" and the location of the famous , as well as the site of Airfield Conference and 4-H Educational Center...

. She tapped the Scottish Clan "McIvor" for the name of Ivor

Ivor, Virginia

Ivor is an incorporated town in Southampton County, Virginia, United States. The population was 320 at the 2000 census.- Overview :Popular legend has it that William Mahone , builder of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad , and his cultured wife, Otelia Butler Mahone , who had been raised in...

, a small Southampton County

Southampton County, Virginia

As of the census of 2010, there were 18,570 people, 6,279 households, and 4,502 families residing in the county. The population density was 29 people per square mile . There were 7,058 housing units at an average density of 12 per square mile...

town. When they reached a location where they could not agree, it is said that the name Disputanta

Disputanta, Virginia

Disputanta is an unincorporated community in Prince George County, Virginia, United States in the Richmond-Petersburg region and is a portion of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area...

was created. The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was completed in 1858, and Mahone was named its president a short time later.

According to some records, in 1860, Mahone owned 7 slaves

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

, all black

Black people

The term black people is used in systems of racial classification for humans of a dark skinned phenotype, relative to other racial groups.Different societies apply different criteria regarding who is classified as "black", and often social variables such as class, socio-economic status also plays a...

: 3 male (ages 13, 4, 2), 4 female (ages 45, 24, 11, 1). Nevertheless, during the Civil War and after, he showed an empathy for former slaves that was atypical for the times, and worked diligently for their fair treatment and education.

"Little Billy": Hero of the Battle of the Crater

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

and Southern

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

factions escalated in the second half of the 19th century, Mahone was in favor of secession

Secession

Secession is the act of withdrawing from an organization, union, or especially a political entity. Threats of secession also can be a strategy for achieving more limited goals.-Secession theory:...

of the Southern states. During the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, he was active in the actual conflict even before he became an officer in the Confederate Army. Early in the War, in 1861, his Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad

The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was built between Norfolk and Petersburg, Virginia and was completed by 1858.It played a role on the American Civil War , and became part of the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad in 1870. The AM&O became the Norfolk and Western in 1881...

was especially valuable to the Confederacy and transported ordnance to the Norfolk area where it was used during the Confederate occupation. By the end of the war, most of what was left of the railroad was in Federal hands.

After Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861, Mahone was still a civilian, and not yet in the Confederate Army, but working in coordination with Walter Gwynn

Walter Gwynn

Walter Gwynn was a civil engineer and soldier who became a Confederate general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, he orchestrated the ruse and capture of the Gosport Shipyard

Norfolk Naval Shipyard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling, and repairing the Navy's ships. It's the oldest and largest industrial facility that belongs to the U.S. Navy as well as the most...

. He bluffed the Federal troops into abandoning the shipyard in Portsmouth by running a single passenger train into Norfolk with great noise and whistle-blowing, then much more quietly, sending it back west, and then returning the same train again, creating the illusion of large numbers of arriving troops to the Federals listening in Portsmouth across the Elizabeth River

Elizabeth River (Virginia)

The Elizabeth River is a tidal estuary forming an arm of Hampton Roads harbor at the southern end of Chesapeake Bay in southeast Virginia in the United States. It is located along the southern side of the mouth of the James River, between the cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk...

(and just barely out of sight). The ruse

Deception

Deception, beguilement, deceit, bluff, mystification, bad faith, and subterfuge are acts to propagate beliefs that are not true, or not the whole truth . Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda, and sleight of hand. It can employ distraction, camouflage or concealment...

worked, and not a single Confederate soldier was lost as the Union authorities abandoned the area, and retreated to Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe was a military installation in Hampton, Virginia—at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula...

across Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

. After this, Mahone accepted a commission as lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Air Force, and United States Marine Corps, a lieutenant colonel is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of major and just below the rank of colonel. It is equivalent to the naval rank of commander in the other uniformed services.The pay...

and later colonel

Colonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

of the 6th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment

6th Virginia Infantry

The 6th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment raised in Virginia for service in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. It fought mostly with the Army of Northern Virginia....

in the Confederate Army. He commanded the Confederate's Norfolk district until its evacuation. He was promoted to brigadier general in November 1861.

In May 1862, after the evacuation of Norfolk by Southern forces during the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

, he aided in the construction of the defenses of Richmond on the James River

James River (Virginia)

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia. It is long, extending to if one includes the Jackson River, the longer of its two source tributaries. The James River drains a catchment comprising . The watershed includes about 4% open water and an area with a population of 2.5 million...

around Drewry's Bluff

Battle of Drewry's Bluff

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, also known as the Battle of Fort Darling, or Fort Drewry, took place on May 15, 1862, in Chesterfield County, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. Five American warships, including the ironclads and , steamed up the James River to...

. A short time later, he led his brigade at the Battle of Seven Pines

Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive up the Virginia Peninsula by Union Maj. Gen....

, and the Battle of Malvern Hill

Battle of Malvern Hill

The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, took place on July 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, on the seventh and last day of the Seven Days Battles of the American Civil War. Gen. Robert E. Lee launched a series of disjointed assaults on the nearly impregnable...

. He also fought at Second Bull Run

Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive campaign waged by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia against Union Maj. Gen...

, Fredericksburg

Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, between General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside...

, Chancellorsville

Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville was a major battle of the American Civil War, and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville Campaign. It was fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Chancellorsville. Two related battles were fought nearby on...

, Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

, the Wilderness

Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness, fought May 5–7, 1864, was the first battle of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Both armies suffered heavy casualties, a harbinger of a bloody war of attrition by...

, and Spotsylvania Court House

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania , was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Overland Campaign of the American Civil War. Following the bloody but inconclusive Battle of the Wilderness, Grant's army disengaged...

.

Small of stature, 5 foot 5 or 6 inches, and weighing only 100 lb (45 kg), he was nicknamed "Little Billy". As one of his soldiers put it, "He was every inch a soldier, though there were not many inches of him." Otelia Mahone was working in Richmond as a nurse, when Virginia Governor John Letcher

John Letcher

John Letcher was an American lawyer, journalist, and politician. He served as a Representative in the United States Congress, was the 34th Governor of Virginia during the American Civil War, and later served in the Virginia General Assembly...

sent word that Mahone had been injured at Second Bull Run, but had only received a "flesh wound." She is said to have replied "Now I know it is serious for William has no flesh whatsoever."

Although his wound at Manassas

Manassas, Virginia

The City of Manassas is an independent city surrounded by Prince William County and the independent city of Manassas Park in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Its population was 37,821 as of 2010. Manassas also surrounds the county seat for Prince William County but that county...

had not been serious, Mahone did suffer from acute dyspepsia

Dyspepsia

Dyspepsia , also known as upset stomach or indigestion, refers to a condition of impaired digestion. It is a medical condition characterized by chronic or recurrent pain in the upper abdomen, upper abdominal fullness and feeling full earlier than expected when eating...

all of his life. During the War, a cow and chickens accompanied him in order to provide dairy products. Otelia and their children moved to Petersburg to be near him during the final campaign of the War in 1864-65 as Grant moved against Petersburg, seeking to sever the rail lines supplying the Confederate capital of Richmond.

It was during that final campaign that William Mahone became widely regarded as the hero of the Battle of the Crater

Battle of the Crater

The Battle of the Crater was a battle of the American Civil War, part of the Siege of Petersburg. It took place on July 30, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee and the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Major General George G. Meade The...

on July 30, 1864. During the Siege of Petersburg

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg Campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War...

of 1864–65, former Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

coal miners in the Union Army tunneled under the Confederate line and blew it up in a massive explosion, killing and wounding many Confederates and breaching a key point in the defense line around Petersburg. However, they lost their initial advantage and Mahone rallied the remaining Confederate forces nearby, repelling the attack. After beginning as an innovative initiative, the Crater scheme turned into a terrible loss for the Union leaders. The quick and effective action led by Mahone was a rare cause for celebration by the occupants of Petersburg, embattled citizens and weary troops alike. "Little Billy" Mahone was promoted to major general as a result.

However, Grant's strategy at Petersburg eventually succeeded as the last rail line from the south to supply the Cockcade City (and hence Richmond) was severed in early April 1865. Mahone was with Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

and the Army of Northern Virginia

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, as well as the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed against the Union Army of the Potomac...

for the surrender at Appomattox Court House

Appomattox Court House

The Appomattox Courthouse is the current courthouse in Appomattox, Virginia built in 1892. It is located in the middle of the state about three miles northwest of the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, once known as Clover Hill - home of the original Old Appomattox Court House...

about a week later. Dr. Douglas Southall Freeman, noted biographer of Robert E. Lee, wrote that, after the surrender, Lee instructed his lieutenants: "Go home and start rebuilding."

Atlantic, Mississippi, and Ohio Railroad

After the war, Lee advised his generals to go back to work rebuilding the Southern economy. William Mahone did just that, and became the driving force in the linkage of N&P, South Side Railroad, and the Virginia and Tennessee RailroadVirginia and Tennessee Railroad

The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was an historic railroad in the Southern United States, much of which is incorporated into the modern Norfolk Southern Railway...

. He was president of all three by the end of 1867. During the post-war Reconstruction period, he worked diligently lobbying the Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

to gain the legislation necessary to form the Atlantic, Mississippi & Ohio Railroad (AM&O), a new line comprising the three railroads he headed, extending 408 miles from Norfolk to Bristol, Virginia

Bristol, Virginia

Bristol is an independent city in Virginia, United States, bounded by Washington County, Virginia, Bristol, Tennessee, and Sullivan County, Tennessee....

, in 1870.

This conflicted with the expansion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was one of the oldest railroads in the United States and the first common carrier railroad. It came into being mostly because the city of Baltimore wanted to compete with the newly constructed Erie Canal and another canal being proposed by Pennsylvania, which...

from Baltimore.

The Mahones were colorful characters: the letters A, M & O were said to stand for "All Mine and Otelia's".

They lived in Lynchburg, Virginia

Lynchburg, Virginia

Lynchburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 75,568 as of 2010. Located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains along the banks of the James River, Lynchburg is known as the "City of Seven Hills" or "The Hill City." Lynchburg was the only major city in...

, during this time, but moved back to Petersburg

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

in 1872.

The Financial Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

put the A,M & O into conflict with its bondholders in England and Scotland. After several years of operating under receiverships, Mahone's relationship with the creditors soured, and an alternate receiver, Henry Fink, was appointed to oversee the A,M & O's finances. Mahone still worked to regain control, but his role as a railroad builder ended, in 1881, when Philadelphia-based interests outbid him and purchased the A,M & O at auction, renaming it Norfolk and Western (N&W).

Before the Civil War, the Virginia Board of Public Works

Virginia Board of Public Works

The Virginia Board of Public Works was a governmental agency which oversaw and helped finance the development of Virginia's internal transportation improvements during the 19th century. In that era, it was customary to invest public funds in private companies, which were the forerunners of the...

had invested state funds in a substantial portion of the stock of the A,M & O's predecessor railroads. Although he lost control of the railroad, as a major political leader in Virginia, Mahone was able to arrange for a portion of the State's proceeds of the sale to be directed to help found a school to prepare teachers to help educate black children and former slaves near his home at Petersburg, where he had earlier been mayor. The Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute eventually expanded to become Virginia State University

Virginia State University

Virginia State University is a historically black and land-grant university located north of the Appomattox River in Chesterfield, in the Richmond area. Founded on , Virginia State was the United States's first fully state-supported four-year institution of higher learning for black Americans...

. He also directed another portion of the funds to help found the predecessor of today's Central State Hospital

Central State Hospital (Virginia)

Central State Hospital is an institution for mentally handicapped adults near Dinwiddie, Virginia. It is supported and administered by the Virginia Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation, and Substance Abuse Services. It was established in 1870....

in Dinwiddie County

Dinwiddie County, Virginia

Dinwiddie County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 28,001. Its county seat is Dinwiddie.- History :...

, also located adjacent to Petersburg. Mahone personally retained his ownership of land investments which were linked to the N&W's development of the rich coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

fields of western Virginia and southern West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

, contributing to his rank as one of Virginia's wealthiest men at his death, according to his biographer, author Nelson Blake.

Virginia politics: Readjuster Party, U.S. Senate

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

as a Delegate from Norfolk in 1863. He later served as mayor of Petersburg

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

. After his unsuccessful bid for governor in 1877, he became the leader of the Readjuster Party

Readjuster Party

The Readjuster Party was a political coalition formed in Virginia in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the American Civil War. Readjusters aspired "to break the power of wealth and established privilege" and to promote public education, a program which attracted biracial support....

, a coalition of Democrats, Republicans

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

, and African-Americans seeking a reduction in Virginia's prewar debt, and an appropriate allocation made to the former portion of the state that constituted the new State of West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

. In 1881, Mahone led the successful effort to elect the Readjuster candidate William E. Cameron as the next governor, and he himself as a United States Senator.

At the Congressional level, with a 37-37 split between Republicans and Democrats in the Senate and with a second third-party candidate willing to caucus with the latter, Mahone's affiliation would determine which party would control the Senate, since under Senate rules, Vice President of the United States

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

Chester A. Arthur

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur was the 21st President of the United States . Becoming President after the assassination of President James A. Garfield, Arthur struggled to overcome suspicions of his beginnings as a politician from the New York City Republican machine, succeeding at that task by embracing...

, a Republican, would cast any tie-breaking votes. Mahone's eventual decision to caucus with the Republicans came at a high price to them. Despite being a freshman senator, he received chairmanship of the influential Agriculture Committee and gained control over Virginia's federal patronage, both from President James A. Garfield, and by the right to select both the Senate's Secretary and Sergeant at Arms.

Once affiliated with the Republican Party, Mahone led Virginia delegations to the Republican National Conventions of 1884 and 1888. However, he lost his Senate seat to Conservative Democrat John W. Daniel

John W. Daniel

John Warwick Daniel was an American lawyer, author, and Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates and represented Virginia in both the U.S. House and then five terms in the Senate...

in 1886. In 1889, he ran for governor on a Republican ticket, but lost to Democrat Philip W. McKinney

Philip W. McKinney

Philip Watkins McKinney was an American politician who served as the 41st Governor of Virginia from 1890 to 1894. Born in New Store, in Buckingham County, he attended Hampden-Sydney College, graduating in the class of 1851. McKinney served as a Confederate officer in the American Civil War in...

. It was to be 80 more years before Virginia sent another non-Democrat to the Governor's Mansion (Republican A. Linwood Holton Jr.

A. Linwood Holton Jr.