Building the Virginian Railway

Encyclopedia

Bituminous coal

Bituminous coal or black coal is a relatively soft coal containing a tarlike substance called bitumen. It is of higher quality than lignite coal but of poorer quality than Anthracite...

reserves in southern West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

early in the 20th century. After facing a refusal of the big railroads (who had their own coal lands) to negotiate equitable rates to interchange and forward the coal for shipping, the owners and their investors expanded their scheme and built a U.S. Class I railroad

Class I railroad

A Class I railroad in the United States and Mexico, or a Class I rail carrier in Canada, is a large freight railroad company, as classified based on operating revenue.Smaller railroads are classified as Class II and Class III...

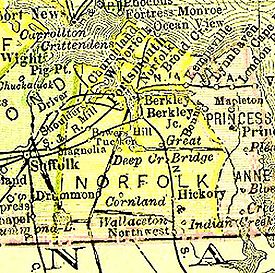

which extended from some of the most rugged terrain of West Virginia over 400 miles (643.7 km) to reach port at Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

near Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

.

Southern West Virginia natural resources

In the expansion westward of the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, transportation was largely via riverRiver

A river is a natural watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, a lake, a sea, or another river. In a few cases, a river simply flows into the ground or dries up completely before reaching another body of water. Small rivers may also be called by several other names, including...

s, canal

Canal

Canals are man-made channels for water. There are two types of canal:#Waterways: navigable transportation canals used for carrying ships and boats shipping goods and conveying people, further subdivided into two kinds:...

s, and other waterways. European moving westward often bypassed settling in the mountainous and wooded regions of western Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

(much of which became the newly-formed State of West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

in 1863) to reach the valley of the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

, and the fertile plains beyond. The Native Americans and early European settlers were aware of coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

deposits throughout the area, and some had small personal mines. However, timber

Timber

Timber may refer to:* Timber, a term common in the United Kingdom and Australia for wood materials * Timber, Oregon, an unincorporated community in the U.S...

was the only natural resource which was practical to export as a product until the railroads emerged as a transportation mode beginning in the 1830s. The earliest railroad to build through the area which is now southern West Virginia was the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P...

(C&O), whose leader, Collis P. Huntington

Collis P. Huntington

Collis Potter Huntington was one of the Big Four of western railroading who built the Central Pacific Railroad as part of the first U.S. transcontinental railroad...

(1821–1900), was initially focused on creating a transcontinental route

Transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad is a contiguous network of railroad trackage that crosses a continental land mass with terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single railroad, or over those owned or controlled by multiple railway companies...

and only later developed coal opportunities and the great railroad shipping locations at Newport News, Virginia

Newport News, Virginia

Newport News is an independent city located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of Virginia. It is at the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula, on the north shore of the James River extending southeast from Skiffe's Creek along many miles of waterfront to the river's mouth at Newport News...

and on the Great Lakes

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes are a collection of freshwater lakes located in northeastern North America, on the Canada – United States border. Consisting of Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario, they form the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth by total surface, coming in second by volume...

. Building west from Covington, Virginia

Covington, Virginia

Covington is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia, located at the confluence of Jackson River and Dunlap Creek. It is in Alleghany County where it is also the county seat. The population was 5,961 in 2010. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Covington with Alleghany...

, the C&O largely followed a water-level route along the Greenbrier

Greenbrier River

The Greenbrier River is a tributary of the New River, long, in southeastern West Virginia, USA. Via the New, Kanawha and Ohio Rivers, it is part of the watershed of the Mississippi River, draining an area of...

, New, and Kanawha River

Kanawha River

The Kanawha River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, it has formed a significant industrial region of the state since the middle of the 19th century.It is formed at the town of Gauley...

s, opening access to the New River Coalfield

New River Coalfield

The New River Coalfield is located in northeastern Raleigh County and southern Fayette County, West Virginia. Commercial mining of coal began in the 1870s and thrived into the 20th century. The coal in this field is a low volatile coal, and the seams of coal that have been mined include Sewell,...

. To the south, following through and refining plans initially developed by William Mahone

William Mahone

William Mahone was a civil engineer, teacher, soldier, railroad executive, and a member of the Virginia General Assembly and U.S. Congress. Small of stature, he was nicknamed "Little Billy"....

(1826–1895) and others, Frederick J. Kimball

Frederick J. Kimball

Frederick James Kimball was a civil engineer. He was an early president of the Norfolk and Western Railway and helped develop the Pocahontas coalfields in Virginia and West Virginia....

(1838–1903) is credited with developing the famous Pocahontas coalfields for the owners of the Norfolk and Western Railway

Norfolk and Western Railway

The Norfolk and Western Railway , a US class I railroad, was formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It had headquarters in Roanoke, Virginia for most of its 150 year existence....

(N&W) who also controlled large tracts of land in the area.

In an area of southern West Virginia not yet reached by either the C&O or the N&W, there was land owned by many others, including Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and candidate for President of the United States...

(1791–1883) and Abram S. Hewitt (1822–1903) (or their estates and heirs), Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

(1840–1909) and William Nelson Page

William N. Page

William Nelson Page was an American civil engineer, entrepreneur, industrialist and capitalist. He was active in the Virginias following the U.S. Civil War...

(1854–1932). While the others were based in northern cities (Hewitt was a mayor of New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, Rogers a vice president of Standard Oil

Standard Oil

Standard Oil was a predominant American integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company. Established in 1870 as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world and operated as a major company trust and was one of the world's first and largest multinational...

headquartered in New York City), Page lived and worked nearby.

Locally known as "Colonel" Page, and trained as a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

, William Nelson Page came to West Virginia in the early 1870s to help build the C&O, and made the mountain state his home. He lived in Ansted

Ansted, West Virginia

Ansted is a town in Fayette County in the U.S. state of West Virginia. It is situated on high bluffs along U.S. Highway 60 on a portion of the Midland Trail a National Scenic Byway near Hawk's Nest overlooking the New River far below....

a tiny mountain hamlet in Fayette County

Fayette County, West Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 47,579 people, 18,945 households, and 13,128 families residing in the county. The population density was 72 people per square mile . There were 21,616 housing units at an average density of 33 per square mile...

on the old James River and Kanawha Turnpike

James River and Kanawha Turnpike

The James River and Kanawha Turnpike was built to facilitate portage of shipments of passengers and freight by water between the western reaches of the James River via the James River and Kanawha Canal and the eastern reaches of the Kanawha River....

(now known as the Midland Trail

Midland Trail

For the trail's section in West Virginia see: The Midland Trail in West Virginia.The Midland Trail, also called the Roosevelt Midland Trail, was a national auto trail spanning the United States from Washington, D.C...

).

Col. Page was a protégé of Dr. David T. Ansted

David T. Ansted

David Thomas Ansted was an English geologist and author.- Youth, education :Ansted was born in London on 5 February 1814. He was educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, and after taking his degree of M.A...

, the British geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

for whom the town of Ansted had been named in 1873. Dr. Ansted, a noted professor in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, owned land in the area, had studied the coal deposits, and had written several books. Page was involved many coal, timber, and railroad projects. He managed a number of coal and iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

projects which were owned by northern U.S. and overseas investors. Among these, he was head of Gauley Mountain Coal Company, whose carpenters he had build a palatial white mansion on a hilltop in the center of town, where he lived with his wife Emma Gilham Page

Emma Gilham Page

Emma Hayden Page was the youngest daughter of Major William Gilham, Commandant of Cadets at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, where she was born 5½ years before the beginning of the American Civil War.In 1882, Emma married William Nelson Page a United States civil engineer,...

and their four children.

- See also featured article William Nelson Page

Deepwater Railway: West Virginia short-line

In 1896, in the western portion of Fayette CountyFayette County, West Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 47,579 people, 18,945 households, and 13,128 families residing in the county. The population density was 72 people per square mile . There were 21,616 housing units at an average density of 33 per square mile...

, Col. Page formed a small logging railroad, Loup Creek and Deepwater Railway which extended from an interchange point at Deepwater, West Virginia

Deepwater, West Virginia

Deep Water, also known historically as Deepwater, is an unincorporated census-designated place on the Kanawha River in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States. As of the 2010 census, its population was 280. It is best known as the starting point of the Deepwater Railway founded in 1898 by...

with the C&O. on the south bank of the navigable Kanawha River

Kanawha River

The Kanawha River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, it has formed a significant industrial region of the state since the middle of the 19th century.It is formed at the town of Gauley...

about four miles (6 km) up a steep grade into the mountainous terrain southward, following the winding Loup Creek to reach a sawmill at Robson

Robson, West Virginia

Robson is an unincorporated village in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States, situated primarily on the banks of Loup Creek. Robson is served by State Highway 61, and is located from Montgomery and to from Oak Hill. Robson's Post Office serves the smaller communities of Beards Fork and...

. Col. Page, who had been involved with building the C&O and more recently in developing some of its coal branches, arranged for the larger railroad to operate his short line to the sawmill on the Loup Creek Estate under a verbal agreement which was to last until 1903.

In 1898, Col. Page renamed his logging railroad to become the Deepwater Railway

Deepwater Railway

The Deepwater Railway was an intrastate short line railroad located in West Virginia in the United States which operated from 1898 to 1907.William N. Page, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, had begun a small logging railroad in Fayette County in 1896, sometimes called the Loup Creek and Deepwater...

, and developed a scheme to convert the railroad into a coal hauler and extend it into portion of the New River coalfield not yet reached by the nearby C&O, originally to somewhere near Glen Jean

Glen Jean, West Virginia

Glen Jean is an unincorporated census-designated place in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States, near Oak Hill. As of the 2010 census, its population is 210....

. He enlisted the support of millionaire

Millionaire

A millionaire is an individual whose net worth or wealth is equal to or exceeds one million units of currency. It can also be a person who owns one million units of currency in a bank account or savings account...

industrialist Henry Huttleton Rogers

Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

in the plan.

In 1902, with Rogers' investment made quietly through the Loup Creek Estate and the Loup Creek Colliery, the Deepwater Railway charter was amended to provide for the short-line railroad to connect with the existing lines of the C&O along the Kanawha River at Deepwater and the N&W at Matoaka

Matoaka, West Virginia

Matoaka is a small town in Mercer County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 317 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Bluefield, WV-VA micropolitan area which has a population of 107,578...

. After the extension provided by the 1902 amendment, the total distance involved, all within West Virginia, was about 80 miles (128.7 km). This longer version than the 1898 scheme would provide access to additional coal lands not only in the New River Field, but also along the upper Guyandotte River

Guyandotte River

The Guyandotte River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 166 mi long, in southwestern West Virginia in the United States. It was named after the French term for the Wendat Native Americans...

basin through Mullens

Mullens, West Virginia

Mullens is a city in Wyoming County, West Virginia. As of the 2000 census, it had a population of 1,769.Located in a valley along the Guyandotte River within a mountainous region of southern West Virginia, the town was nearly destroyed by flash flooding in July 2001...

and into area under development by the N&W.

By planning interchange points with the two large railroads, Page could anticipate competition and negotiation of fair rates with the only two big railroads nearby. However, as he developed the short-line Deepwater Railway and began attempting to negotiate with either of the larger railroads, he ran into an unexpected brick wall. Page had realized that each major railroad had considered the territory his company was developing to be potentially theirs for future growth, but when each was faced with his new traffic going instead to a competitor, he had thought negotiations would still be possible. However, he got nowhere with either of them.

There was a reason, and it presented a serious obstacle to the Deepwater Railway plans: collusion

Collusion

Collusion is an agreement between two or more persons, sometimes illegal and therefore secretive, to limit open competition by deceiving, misleading, or defrauding others of their legal rights, or to obtain an objective forbidden by law typically by defrauding or gaining an unfair advantage...

. It was only later revealed that at the time, both the C&O and the N&W were essentially under the common control of the even larger Pennsylvania Railroad

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad was an American Class I railroad, founded in 1846. Commonly referred to as the "Pennsy", the PRR was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania....

(PRR) and New York Central Railroad

New York Central Railroad

The New York Central Railroad , known simply as the New York Central in its publicity, was a railroad operating in the Northeastern United States...

(NYC), whose leaders, Alexander Cassatt

Alexander Cassatt

Alexander Johnston Cassatt was the 7th president of the Pennsylvania Railroad , serving from June 9, 1899 to December 28, 1906. Frequently referred to as A. J. Cassatt, the great accomplishment under his stewardship was the planning and construction of tunnels under the Hudson River to finally...

and William Vanderbilt

William Kissam Vanderbilt

William Kissam Vanderbilt was a member of the prominent American Vanderbilt family. He managed railroads and was a horse breeder.-Biography:...

respectively, had secretly entered into a "community of interests" pact. The C&O and the N&W had apparently agreed with each other to refuse to negotiate with Col. Page and his upstart Deepwater Railway. It wasn't just the rates that Page wanted to share, which could possibly have been negotiated. The bigger issue was the coal lands which both larger railroads, especially the N&W, had large investments in.

If Col. Page and his Deepwater Railway scheme had met with an unpleasant surprise, as it turned out, the big railroads were in for an even bigger one. Page didn't give up his scheme, as most surely must have been anticipated. Instead, he stubbornly continued building his short-line railroad through some of the most rugged terrain of the Mountain State, to the increasing puzzlement of the leaders of the big railroads. They were unaware that one of Page's investors (who were silent partner

Silent partner

Silent partner may refer to:*An anonymous member of a business partnership, or one uninvolved in management*The Silent Partner, the name of several films*Silent partner , a piece of climbing equipment...

s in the venture) was the powerful Rogers. Henry Rogers was an old hand at mineral and transportation development, and his projects and investments seldom failed. His tenacity, energy, and organizational skills had led him to become one of John D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of...

's key men at the Standard Oil Trust. Always ready to do corporate battle, Rogers wasn't about to have the Deepwater investment foiled by the big railroads.

See also article Henry H. Rogers

Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

When Page and Rogers realized the Deepwater Railway project would have no connection options with other railroads to ship its coal, they set about exploring alternatives. One of these was securing their own route out of the mountains of West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

, if necessary, all the way to the sea, if suitable connections could not be made in Virginia. By forcing Rogers' hand, the seeds for what would become the Virginian Railway

Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads....

had been planted by the C&O and N&W.

From the mountains to the sea

While they may not have recognized the collusion of the C&O and N&W, Page and Rogers did know that the larger railroads would surely attempt to block any effort to extend the Deepwater a great distance to reach any other major trunk lines, many of which such as the New York Central, Pennsylvania and Baltimore and Ohio RailroadBaltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was one of the oldest railroads in the United States and the first common carrier railroad. It came into being mostly because the city of Baltimore wanted to compete with the newly constructed Erie Canal and another canal being proposed by Pennsylvania, which...

were also under common control of sorts (although it is not known if Page and Rogers realized or even suspected this). However, to their advantage, the Deepwater Railway charter already granted by West Virginia came to a location within a fairly short distance of the Virginia state line.

Railroads in the United States often grew by combining smaller lines, and that is how the C&O and N&W each had grown between the 1830s and 1898 when the Deepwater Railway began its expansions. However, there appeared to be no extant Virginia short-lines available for the Deepwater interests to acquire to suit their needs. Therefore, on October 13, 1904, they had new intrastate railroad company, the Tidewater Railway

Tidewater Railway

The Tidewater Railway was formed in 1904 as an intrastate railroad in Virginia, in the United States, by William N. Page, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, and his silent partner, millionaire industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers of Standard Oil fame...

chartered in Virginia to be used for the portion of their project to be in that state. The headquarters were in Staunton

Staunton, Virginia

Staunton is an independent city within the confines of Augusta County in the commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 23,746 as of 2010. It is the county seat of Augusta County....

, where one of Henry Rogers' lawyers, Thomas D. Ransom, was based and Col. Page had relatives. In the new charter, no direct reference was made to a possible future connection with the Deepwater, nor was one precluded by limiting language.

In those days, railroad and real estate attorneys

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

generally practiced in only one state, with land matters (such as right-of-way

Right-of-way (railroad)

A right-of-way is a strip of land that is granted, through an easement or other mechanism, for transportation purposes, such as for a trail, driveway, rail line or highway. A right-of-way is reserved for the purposes of maintenance or expansion of existing services with the right-of-way...

) generally handled in various local county courts. Apparently because the Deepwater Railway in West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

and Tidewater Railway in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

were each under the jurisdiction of their respective states, an association between the two little railroads was not identified initially by the various lawyers for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P...

and the Norfolk and Western Railway

Norfolk and Western Railway

The Norfolk and Western Railway , a US class I railroad, was formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It had headquarters in Roanoke, Virginia for most of its 150 year existence....

.

Planning and land acquisition for the Tidewater Railway were done largely in secret. In his book The Virginian Railway (Kalmbach, 1961), author H. Reid

H. Reid

Harold A. Reid was an American writer, photographer, and historian. Reid is best known for his lifelong love of railroading and related photography and published work...

described some of the tactics used. Reid recalled that on a Sunday in February, 1905, a group of 35 surveyors from New York disguised themselves as fishermen and rode to the location aboard a N&W passenger train. While they stood in icy water apparently "fishing" with their transit poles, the surveyors mapped out a crossing of the New River

New River (West Virginia)

The New River, part of the Ohio River watershed, is a tributary of the Kanawha River about 320 mi long. The river flows through the U.S. states of North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia...

at Glen Lyn

Glen Lyn, Virginia

Glen Lyn is a town in Giles County, Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the East and New Rivers. The population was 151 at the 2000 census...

, as well as the adjacent portion of the line through Narrows

Narrows, Virginia

Narrows, named for the narrowing of the New River that flows past it, is a town in Giles County, Virginia, United States. The population was 2,111 at the 2000 census...

to point near Radford

Radford, Virginia

Radford is a city in Virginia, United States. The population was 16,408 in 2010. For statistical purposes, the Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Radford with neighboring Montgomery County, including the towns of Blacksburg and Christiansburg, calling the combination the...

.

After leaving the valley of the New River, the new line was surveyed to cross the U.S. Eastern Continental Divide

Eastern Continental Divide

The Eastern Continental Divide, in conjunction with other continental divides of North America, demarcates two watersheds of the Atlantic Ocean: the Gulf of Mexico watershed and the Atlantic Seaboard watershed. Prior to 1760, the divide represented the boundary between British and French colonial...

in a mile-long tunnel to be built near Merrimac, Virginia

Merrimac, Virginia

Merrimac is a census-designated place in Montgomery County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,751 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Blacksburg–Christiansburg–Radford Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Montgomery County and the city of...

. After descending on the eastern side of the mountain, the new line for the Tidewater Railway essentially followed the valley of the Roanoke River

Roanoke River

The Roanoke River is a river in southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States, 410 mi long. A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains southeast across the Piedmont...

past the cities of Salem

Salem, Virginia

Salem is an independent city in Virginia, USA, bordered by the city of Roanoke to the east but otherwise adjacent to Roanoke County. It is part of the Roanoke Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 24,802 according to 2010 U.S. Census...

and Roanoke

Roanoke, Virginia

Roanoke is an independent city in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. state of Virginia and is the tenth-largest city in the Commonwealth. It is located in the Roanoke Valley of the Roanoke Region of Virginia. The population within the city limits was 97,032 as of 2010...

and through the water gap formed by the Roanoke River in the Blue Ridge Mountains

Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap. The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southern-most...

. As the terrain changed to the more gentle rolling hills of the Piedmont region, the plan was to run almost due east across Southside Virginia to Suffolk

Suffolk, Virginia

Suffolk is the largest city by area in Virginia, United States, and is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 84,585. Its median household income was $57,546.-History:...

, within just a few miles of the goal: Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

, one of the world's largest harbor

Harbor

A harbor or harbour , or haven, is a place where ships, boats, and barges can seek shelter from stormy weather, or else are stored for future use. Harbors can be natural or artificial...

s. There, ships could be loaded with coal destined for northeastern U.S. ports, or other countries overseas.

Agents for the Tidewater Railway quietly struck deals with the landowners and various communities all along the way. Many were small towns and villages that had been passed by when the big railroads were choosing routes and building 20-25 years earlier, and the new railroad was welcomed. At several key points, negotiations were especially sensitive. Roanoke

Roanoke, Virginia

Roanoke is an independent city in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. state of Virginia and is the tenth-largest city in the Commonwealth. It is located in the Roanoke Valley of the Roanoke Region of Virginia. The population within the city limits was 97,032 as of 2010...

was one such place, as the Norfolk & Western had virtually put Roanoke on the map only 20 years earlier when it had been only a tiny town known as Big Lick. However, in the spirit of free enterprise

Free enterprise

-Transport:* Free Enterprise I, a ferry in service with European Ferries between 1962 and 1980.* Free Enterprise II, a ferry in service with European Ferries between 1965 and 1982....

, the leaders of the City of Roanoke agreed to provide the needed right-of-way through the city along the north bank of the Roanoke River. This was only a short distance from N&W's general offices and principal shops.

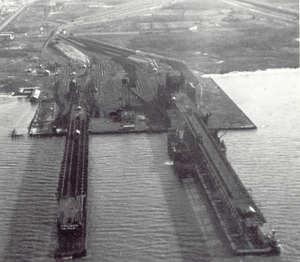

A coup at Sewell's Point

Perhaps most notable of all of the communities which helped make the new railroad possible was the City of Norfolk, VirginiaNorfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

. Access to Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

frontage and space to build a new coal pier was crucial to the whole scheme. There just wasn't enough suitable waterfront land available anywhere nearby, and none at all to which access could be assured without permission of the big railroads. Norfolk & Western's coal pier and huge storage yards were at Lambert's Point

Lambert's Point

Lamberts Point is a point of land on the south shore of the Elizabeth River near the downtown area of the independent city of Norfolk in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia, United States...

on the Elizabeth River

Elizabeth River (Virginia)

The Elizabeth River is a tidal estuary forming an arm of Hampton Roads harbor at the southern end of Chesapeake Bay in southeast Virginia in the United States. It is located along the southern side of the mouth of the James River, between the cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk...

near downtown Norfolk. Other big railroads, Seaboard Air Line, Atlantic Coast Line

Atlantic Coast Line Railroad

The Atlantic Coast Line Railroad was an American railroad that existed between 1900 and 1967, when it merged with the Seaboard Air Line Railroad, its long-time rival, to form the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad...

, and a Pennsylvania Railroad

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad was an American Class I railroad, founded in 1846. Commonly referred to as the "Pennsy", the PRR was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania....

subsidiary, had established facilities nearby as well.

Newport News, Virginia

Newport News is an independent city located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of Virginia. It is at the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula, on the north shore of the James River extending southeast from Skiffe's Creek along many miles of waterfront to the river's mouth at Newport News...

nor the N&W find out, or surely they would attempt to interfere with creation of a new coal pier.

Fortunately, about this same time, Norfolk

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

's civic leaders were also working on a site for the upcoming Jamestown Exposition

Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

, to be held in 1907 to celebrate the tercentennial of the founding of Jamestown

Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

a few miles up the James River

James River (Virginia)

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia. It is long, extending to if one includes the Jackson River, the longer of its two source tributaries. The James River drains a catchment comprising . The watershed includes about 4% open water and an area with a population of 2.5 million...

back in 1607 (300 years earlier). A solution to both the Tidewater Railway coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

pier site and Jamestown Exposition problems was found at an unlikely location: isolated and somewhat desolate Sewell's Point

Sewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and the Lafayette...

in a rural area on the south bank of the Elizabeth River near the mouth of Hampton Roads.

To reach Sewell's Point from Suffolk, the Tidewater Railway was plotted to run about 15 miles (24.1 km) to the east, staying well south of the downtown Portsmouth and Norfolk harbor areas (and the other railroads). After reaching South Norfolk

South Norfolk, Virginia

South Norfolk was an independent city in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia and is now a section of the City of Chesapeake, one of the cities of Hampton Roads which surround the harbor of Hampton Roads and are linked by the Hampton Roads Beltway.-History:Located a few miles south of...

, the new railroad would begin a wide 180' counter-clockwise loop to the north. The new coal trains would actually heading due west when reaching Hampton Roads.

To enable the necessary routing, the City of Norfolk's civic leaders provided a 13 miles (20.9 km) long right-of-way around their city through rural Norfolk County

Norfolk County, Virginia

Norfolk County was a county of the South Hampton Roads in eastern Virginia in the United States that was created in 1691. After the American Civil War, for a period of about 100 years, portions of Norfolk County were lost and the territory of the county reduced as they became parts of the separate...

. Page-Rogers' interests purchased 1000 feet (300 m) of the waterfront and 500 acres (202.3 ha) of adjoining land. There would be plenty of space for the new coal pier, storage yards, tracks, and support facilities at Sewell's Point. And, best of all, the land and route were each secured without alerting the big railroads.

Extending the Deepwater Railway to meet the Tidewater Railway

In West Virginia, the owners, surveyors, and builders of the Deepwater RailwayDeepwater Railway

The Deepwater Railway was an intrastate short line railroad located in West Virginia in the United States which operated from 1898 to 1907.William N. Page, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, had begun a small logging railroad in Fayette County in 1896, sometimes called the Loup Creek and Deepwater...

ran into lots of conflicts with both the C&O and the N&W. There was a nasty dispute with C&O forces over a contested tunnel site near Jenny Gap which landed in court. The Raleigh County

Raleigh County, West Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 79,220 people, 31,793 households, and 22,096 families residing in the county. The population density was 130 people per square mile . There were 35,678 housing units at an average density of 59 per square mile...

court ruled for the C&O, but the West Virginia Supreme Court reversed the ruling in favor of the Deepwater Railway. In another court case, Page had what may have been a near-miss with a perjury charge. Upon interrogation by N&W attorneys in a West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

legal confrontation over right-of-way, Col. Page representing the Deepwater Railway, identified the estate of the late Abram S. Hewitt, a former mayor of New York as one of his investors. Page never mentioned Rogers, who it is now known had been an associate of Hewitt and may have been acting through the Hewitt estate. The N&W attorneys were unsuccessful in learning more at that time, or during many other confrontations as they attempted to stop the progress of the Deepwater in West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

. Ultimately, both the C&O and the N&W lost the battle and the Deepwater routing was successfully secured east to the Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

state line near Glen Lyn

Glen Lyn, Virginia

Glen Lyn is a town in Giles County, Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the East and New Rivers. The population was 151 at the 2000 census...

.

At the same time, over in Virginia, in 1905, with the land and route secured, construction got underway on the Tidewater Railway

Tidewater Railway

The Tidewater Railway was formed in 1904 as an intrastate railroad in Virginia, in the United States, by William N. Page, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, and his silent partner, millionaire industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers of Standard Oil fame...

, which as it turned out, went nowhere near its headquarters in Staunton on the C&O. Instead, it started building an alignment which would match up amazingly well with the Deepwater Railway near Glen Lyn, and run almost parallel to the N & W all the way to Norfolk. By the time the larger railroads finally realized what was happening, and that Page was involved in both the Deepwater and Tidewater Railways, their new competitor could not be successfully blocked on the basis of right-of-way. The building of another major railroad from the mountains-to-the-sea seemed to have been set in motion. Completion, however, was still far from assured.

Page still willing to negotiate

As the construction continued throughout 1905, Col. Page continued to meet with each of the big railroads to attempt to negotiate rates for the Deepwater Railway's coal, offering to stop construction on the Tidewater Railway, and/or perhaps sell off his fledging enterprise. The leaders of the C&O and N&W exchanged correspondence which has been preserved in company archives sharing their mutual concern about the "common enemy." To them, Page did not appear to be financially capable of the project and they were skeptical that the new Deepwater and Tidewater railroads could be financed and completed. After all, they reasoned, there had been no public offering of bonds or stock, which were the way such enterprises were customarily financed at the time. All across the United States, railroad projects had been started, and many had died for lack of funds. Perhaps, the Page enterprise would join such ranks.Gambling on that premise, the two big railroads saw to it that the "negotiations" were always unproductive, and Col. Page always declined to indicate the source of his apparently "deep pockets." By this time, Page must surely have been enjoying his new found power in dealing with the arrogant big railroads. In fact, management of the funding Rogers was providing was handled by Boston

Boston

Boston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

financier Godfrey M. Hyams

Godfrey M. Hyams

Godfrey M. Hyams was an American metallurgist, civil engineer, financier, and philanthropist.Hyams was born in Baltimore, Maryland. His family moved to Boston, Massachusetts while he was a child...

, with whom he had also worked on the Anaconda Company, and many other natural resource projects.

Final attempts to block

Norfolk and Western clearly stood the most to lose by the Deepwater-Tidewater combination. Once rights-of-way had been granted, N&W President Lucius E. JohnsonLucius E. Johnson

Lucius E. Johnson was a president of the Norfolk and Western Railway from 1904 until his death in 1921, with the exception of 5 months in 1918 when he served as Chairman of its Board. He lived in Roanoke, Virginia....

(who had succeeded Frederick J. Kimball

Frederick J. Kimball

Frederick James Kimball was a civil engineer. He was an early president of the Norfolk and Western Railway and helped develop the Pocahontas coalfields in Virginia and West Virginia....

) tried a different tactic to block (or at least slow construction and increase costs) on the Tidewater Railway. He filed papers with the newly-formed Virginia State Corporation Commission, which had replaced the Virginia Board of Public Works

Virginia Board of Public Works

The Virginia Board of Public Works was a governmental agency which oversaw and helped finance the development of Virginia's internal transportation improvements during the 19th century. In that era, it was customary to invest public funds in private companies, which were the forerunners of the...

in 1903 and regulated Virginia's railroads, to attempt to force costly overpasses at proposed at-grade crossings with the N&W in Roanoke and South Norfolk

South Norfolk, Virginia

South Norfolk was an independent city in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia and is now a section of the City of Chesapeake, one of the cities of Hampton Roads which surround the harbor of Hampton Roads and are linked by the Hampton Roads Beltway.-History:Located a few miles south of...

citing "great concern about the potential safety hazards" which would allegedly result.

The state authorities in Virginia ruled against N&W at both locations, and ordered it to accept interlocking (at grade) crossings with the new Tidewater Railway. The new railroad did accommodate the N&W with grade separations for crossings at Wabun, west of Salem

Salem, Virginia

Salem is an independent city in Virginia, USA, bordered by the city of Roanoke to the east but otherwise adjacent to Roanoke County. It is part of the Roanoke Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 24,802 according to 2010 U.S. Census...

and Kilby, just west of Suffolk

Suffolk, Virginia

Suffolk is the largest city by area in Virginia, United States, and is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 84,585. Its median household income was $57,546.-History:...

. However, these caused no major construction delays, as N&W's Johnson had hoped, and, if anything, the construction of the new Tidewater Railway continued at an even faster pace.

Henry Rogers steps forward

There was a lot at stake, as the C&O and N&W through the secret "community of interests pact" were carefully controlling coal shipping rates. Such collusion was the very game that helped Rogers make his fortune at Standard Oil

Standard Oil

Standard Oil was a predominant American integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company. Established in 1870 as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world and operated as a major company trust and was one of the world's first and largest multinational...

.

Finally, well into 1906, at the request of Rogers, famous industrialist turned philanthropist

Philanthropist

A philanthropist is someone who engages in philanthropy; that is, someone who donates his or her time, money, and/or reputation to charitable causes...

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-American industrialist, businessman, and entrepreneur who led the enormous expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century...

brought President Lucius E. Johnson

Lucius E. Johnson

Lucius E. Johnson was a president of the Norfolk and Western Railway from 1904 until his death in 1921, with the exception of 5 months in 1918 when he served as Chairman of its Board. He lived in Roanoke, Virginia....

of the Norfolk & Western Railway to Rogers' office in the Standard Oil Building in New York. According to N&W's corporate records, the meeting lasted less than five minutes. Some tense and less-than-pleasant words were exchanged, and Rogers' backing had finally been confirmed.

Of course, the head of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway soon also received the news, as did the leaders of the Pennsylvania and New York Central railroads. There would be an old and experienced hand at rate-making as a new player in their game of shipping coal.

1907: Virginian Railway born

In early 1907, the name of the Tidewater Railway was changed by amendment to its articles of incorporation in Virginia to become "The Virginian Railway Company." The Deepwater Railway, a West Virginia corporation, was acquired by and merged into the Virginian RailwayVirginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads....

a month later. On April 15, 1907, by a unanimous vote of the board of directors, Col. William Nelson Page became the first president of the new Virginian Railway

Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads....

.

About the same time, a large stretch of the eastern portion had been completed and regular passenger service established. This proved to be right-on time for a civic need of the City of Norfolk, and the Hampton Roads region.

Jamestown Exposition: helping a neighbor

Sewell's PointSewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and the Lafayette...

had been selected by the Jamestown Exposition

Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

Company for the international exposition on a mile-long site fronting on Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

right next to the Tidewater Railway property. The choice of location was politically correct: it was almost an equal distance from the cities of Norfolk

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

, Portsmouth

Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of the U.S. Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the city had a total population of 95,535.The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard, is a historic and active U.S...

, Newport News

Newport News, Virginia

Newport News is an independent city located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of Virginia. It is at the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula, on the north shore of the James River extending southeast from Skiffe's Creek along many miles of waterfront to the river's mouth at Newport News...

and Hampton

Hampton, Virginia

Hampton is an independent city that is not part of any county in Southeast Virginia. Its population is 137,436. As one of the seven major cities that compose the Hampton Roads metropolitan area, it is on the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula. Located on the Hampton Roads Beltway, it hosts...

.

A big plus for the site selection for the Exposition organizers was favorable access by water. A naval review was to be a major feature of the Exposition. Of course, one downside to the location was that the rural and sparely populated location was hard to reach by land. However, the new railroad was soon to be laying tracks nearby and could be relied upon to help transport the millions of attendees anticipated on land adjacent to the site where work had already begin on the new coal pier.

On April 26, 1907, US President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

opened the exposition. Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

was another honored guest, arriving with his friend Henry Rogers on the latter's yacht Kanawha

Kanawha (1899)

Kanawha was a 471-ton steam-powered luxury yacht initially built in 1899 for millionaire industrialist and financier Henry Huttleston Rogers . One of the key men in the Standard Oil Trust, Rogers was one of the last of the robber barons of the Gilded Age in the United States...

. At the exposition, Colonel Page, president of the new Virginian Railway next door, served as Chief of International Jury of Awards, Mines and Metallurgy. In addition to President Roosevelt, the VGN and the original Norfolk Southern Railway

Norfolk Southern Railway (former)

The Norfolk Southern Railway was the final name of a railroad running from Norfolk, Virginia southwest and west to Charlotte, North Carolina. It was acquired by the Southern Railway in 1974, which was merged with the Norfolk and Western Railway in 1990 to form the current entity of the Norfolk...

transported many of the 3 million persons who attended before the Exposition closed on December 1, 1907.

See Also article Jamestown Exposition

Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

Financial panic of 1907, Rogers suffers a stroke

While secrecy was a key feature of the success in securing the route, historians feel it is likely that Rogers had planned to finance the new railroad with sale of bonds to the public once the route had been secured, the two roads combined, and the name changed. However, these plans had suffered some setbacks in the "Financial PanicPanic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic, was a financial crisis that occurred in the United States when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from its peak the previous year. Panic occurred, as this was during a time of economic recession, and there were numerous runs on...

" which began in March of 1907. An initial offering of Virginian Railway bonds was poorly received by the financial community. Rogers was quite concerned about the situation, and then, a few months later that same year, he experienced a debilitating stroke

Stroke

A stroke, previously known medically as a cerebrovascular accident , is the rapidly developing loss of brain function due to disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This can be due to ischemia caused by blockage , or a hemorrhage...

. Work on the new railroad was at a virtual standstill throughout much of 1908. His published correspondence with his close friend Mark Twain alludes to the personal stress which resulted from the "great railroad enterprise."

Fortunately for the new railroad, Henry Rogers recovered his health, at least partially. Work progressed on the VGN using construction techniques not available when the larger railroads had been built about 25 years earlier. By paying for work with Henry Rogers' own personal fortune, the railway was built with no public debt. Construction, although slowed substantially during 1908, was continued on the new railroad until it was finally completed early in 1909.

Final spike, celebrations, tragedy

The final spike in the Virginian Railway was driven on January 29, 1909, at the west side of the massive New RiverNew River (West Virginia)

The New River, part of the Ohio River watershed, is a tributary of the Kanawha River about 320 mi long. The river flows through the U.S. states of North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia...

Bridge at Glen Lyn

Glen Lyn, Virginia

Glen Lyn is a town in Giles County, Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the East and New Rivers. The population was 151 at the 2000 census...

, near where the new railroad crossed the East River

East River (West Virginia)

The East River is a short tributary of the New River in Mercer County, West Virginia and a small portion of Giles County, Virginia, in the United States...

and the West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

-Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

state line. The former Deepwater and Tidewater Railways were now physically connected. It was also Henry Rogers' sixty-ninth birthday,

In April, 1909, Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

and Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

, old friends, returned to Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

together once again for a huge celebration of the new "Mountains to the Sea" railroad's completion.

They were met at the shore by a huge crowd of Norfolk citizens waiting with great excitement despite rain that day. While Rogers toured the railway’s new $2.5 million coal pier at Sewell's Point

Sewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and the Lafayette...

, Mark Twain spoke to groups of students at several local schools. That night, April 3, the city put on a long-planned grand banquet at the Monticello Hotel in downtown Norfolk. The city's civic leaders, Mark Twain, and other dignitaries made speeches. Finally, Henry Rogers himself rose and addresses the well-wishers. He said in part:

- "It is a great honor, and I shall not deny a great pleasure, to be your guest on this occasion. I am not gifted with the art of oratory, and am forced to say my thanks in plain and homely words. Yet they are none the less heartfelt. I make no pretense that the building of the Virginian Railway was intended wholly as a public service, and it is a business enterprise. I have faith that the resources of this Old Dominion State, when properly developed, mean a great deal, not for you who live here alone, but for the whole country."

- "And I have simply sought to bear what share I could in the development of these resources. You gentlemen of Virginia and I have a common interest. I shall endeavor to deal fairly by you and I am sure you propose doing the same by me. Again I thank you from the bottom of my heart for the honor you have conferred upon me."

Rogers and his party boarded a special train, and left the next day on his first (and only) tour of the newly completed railroad. He was greeted at points all along the route, and there was at least one additional banquet held to honor him at Roanoke

Roanoke, Virginia

Roanoke is an independent city in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. state of Virginia and is the tenth-largest city in the Commonwealth. It is located in the Roanoke Valley of the Roanoke Region of Virginia. The population within the city limits was 97,032 as of 2010...

. A now-famous photograph was taken of him of the rear platform of his personal railcar, which was named "Dixie."

Despite the relief of completing the "mountains-to-the sea" railroad, both his physician and mentor John D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of...

had expressed continuing concerns about Henry Rogers' health and urged him to slow down. He was known as a man who just couldn't seem to "take it easy," at least not for very long. The following month, in May 1909, he took a pleasant weekend getaway trip to his hometown of Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Fairhaven is a town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, in the United States. It is located on the south coast of Massachusetts where the Acushnet River flows into Buzzards Bay, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean...

. Afterward, he returned to New York City and his work. Three days later, on May 19, 1909, he awoke feeling very ill, and had numbness in his arm. By the time the doctor arrived in less than 30 minutes, he could not be saved. After his funeral in New York City, with Virginian Railway officials and his close friend Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

serving as pallbearers, the old widowers' body was transported by train to Fairhaven, to be interred in Riverside Cemetery beside his childhood sweetheart, Abbie Gifford Rogers

Abbie G. Rogers

Abbie Gifford Rogers , was the first wife of Henry Huttleston Rogers, , a United States capitalist, businesswoman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist....

(1841-1894).

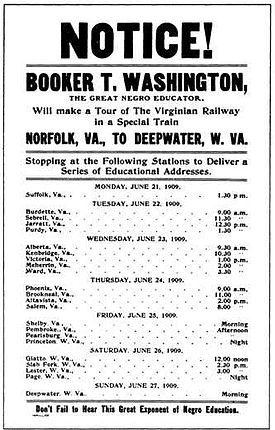

Last tour planned by Rogers

For the last 15 years of his life, Rogers had become close friends with Dr. Booker T. WashingtonBooker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

, the famous African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

educator. Dr. Washington had been an honored guest at Rogers' office and home in New York, his summer home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and aboard his steam yacht Kanawha. Rogers had been secretly funding much of Dr. Washington's work. They had planned a speaking tour for Dr. Washington along the new railroad to take place just prior to opening of through passenger service scheduled for July 1, 1909. Although Rogers had died suddenly, Dr. Washington decided to go ahead with his wishes for the previously arranged speaking tour in June 1909 along the route of the new railroad.

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s along the route of the new railway, which touched many previously isolated communities in the southern portions of Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

and West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

.

Some of the places where Dr. Washington spoke on the tour were (in order of the tour stops), Newport News

Newport News, Virginia

Newport News is an independent city located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of Virginia. It is at the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula, on the north shore of the James River extending southeast from Skiffe's Creek along many miles of waterfront to the river's mouth at Newport News...

, Norfolk

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

, Suffolk

Suffolk, Virginia

Suffolk is the largest city by area in Virginia, United States, and is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 84,585. Its median household income was $57,546.-History:...

, Lawrenceville

Lawrenceville, Virginia

Lawrenceville is a town in Brunswick County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,275 at the 2000 census. Located by the Meherrin River, it is the county seat of Brunswick County and home to historically black Saint Paul's College, founded in 1888 and affiliated with the Episcopal Church...

, Kenbridge

Kenbridge, Virginia

Kenbridge is a town in Lunenburg County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,253 at the 2000 census. It is in a tobacco farming area. The area is home to noted folk artist Eldridge Bagley.-Geography:Kenbridge is located at ....

, Victoria

Victoria, Virginia

Victoria is an incorporated town in Lunenburg County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,821 at the 2000 census.- History :Lunenburg County in the Southside region was established on May 1, 1746 in Great Britain's Virginia Colony from Brunswick County...

, Charlotte Courthouse

Charlotte Court House, Virginia

Charlotte Court House is a town in and the county seat of Charlotte County, Virginia, United States. The population was 404 at the 2000 census.-Geography:...

, Roanoke

Roanoke, Virginia

Roanoke is an independent city in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. state of Virginia and is the tenth-largest city in the Commonwealth. It is located in the Roanoke Valley of the Roanoke Region of Virginia. The population within the city limits was 97,032 as of 2010...

, Salem

Salem, Virginia

Salem is an independent city in Virginia, USA, bordered by the city of Roanoke to the east but otherwise adjacent to Roanoke County. It is part of the Roanoke Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 24,802 according to 2010 U.S. Census...

, and Christiansburg

Christiansburg, Virginia

Christiansburg is a town in Montgomery County, Virginia, United States. The population was 21,041 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Montgomery County...

in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, and Princeton

Princeton, West Virginia

Princeton is a city in Mercer County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 7,652 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Bluefield, WV-VA micropolitan area which has a population of 111,586. It is the county seat of Mercer County...

, Mullens

Mullens, West Virginia

Mullens is a city in Wyoming County, West Virginia. As of the 2000 census, it had a population of 1,769.Located in a valley along the Guyandotte River within a mountainous region of southern West Virginia, the town was nearly destroyed by flash flooding in July 2001...

, Page

Page, West Virginia

Page is an unincorporated census-designated place in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States. As of the 2010 census, its population was 224. It was named for William Nelson Page , a civil engineer and industrialist who lived in nearby Ansted, where he managed Gauley Mountain Coal Company and...

and Deepwater

Deepwater, West Virginia

Deep Water, also known historically as Deepwater, is an unincorporated census-designated place on the Kanawha River in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States. As of the 2010 census, its population was 280. It is best known as the starting point of the Deepwater Railway founded in 1898 by...

in West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

. One of his trip companions reported that they had received a strong and favorable welcome from both white and African American citizens all along the tour route.

It was only after the multi-millionaire's death that Dr. Washington said he felt compelled to reveal publicly some of the extent of Henry Rogers' contributions for his causes. The funds, he said, were at that very time paying for the operation of at least 65 small country schools for the education and betterment of African Americans in Virginia and other portions of the South, all unknown to the recipients. Dr. Washington also disclosed that, known only to a few trustees, Henry Rogers had also generously provided support to institutions of higher education such as the schools which are now Hampton University

Hampton University

Hampton University is a historically black university located in Hampton, Virginia, United States. It was founded by black and white leaders of the American Missionary Association after the American Civil War to provide education to freedmen.-History:...

and Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University is a private, historically black university located in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It is a member school of the Thurgood Marshall Scholarship Fund...

.

Dr. Washington later wrote that Henry Rogers had encouraged projects with at least partial matching funds

Matching funds

Matching funds, a term used to describe the requirement or condition that a generally minimal amount of money or services-in-kind originate from the beneficiaries of financial amounts, usually for a purpose of charitable or public good.-Charitable causes:...

, as that way, two ends were accomplished:

- 1. The gifts would help fund even greater work.

- 2. Recipients would have a stake in knowing that they were helping themselves through their own hard work and sacrifice.

See Also article Dr. Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

.

Legacy

By the time Henry Rogers died, the work of the Page-Rogers partnership to build the Virginian Railway had been completed. It was a virtual "conveyor belt of steel" and as it turned out, the growing demand for coal was more than sufficient for coexistence of the Virginia Railway with the Chesapeake and Ohio and the Norfolk and Western for many years to come. Through what he had learned about the people of southern West Virginia and southside Virginia, while building the Virginian Railway to maximize the natural resource of coal, Rogers had also come to appreciate the potential for development of the area's human resourcesHuman resources

Human resources is a term used to describe the individuals who make up the workforce of an organization, although it is also applied in labor economics to, for example, business sectors or even whole nations...

as well.

See also

- William N. PageWilliam N. PageWilliam Nelson Page was an American civil engineer, entrepreneur, industrialist and capitalist. He was active in the Virginias following the U.S. Civil War...

- Henry H. RogersHenry H. RogersHenry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

- Bituminous coalBituminous coalBituminous coal or black coal is a relatively soft coal containing a tarlike substance called bitumen. It is of higher quality than lignite coal but of poorer quality than Anthracite...

- Robber BaronsRobber baron (industrialist)Robber baron is a pejorative term used for a powerful 19th century American businessman. By the 1890s the term was used to attack any businessman who used questionable practices to become wealthy...

- Norfolk and Western RailwayNorfolk and Western RailwayThe Norfolk and Western Railway , a US class I railroad, was formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It had headquarters in Roanoke, Virginia for most of its 150 year existence....

- Chesapeake and Ohio RailwayChesapeake and Ohio RailwayThe Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P...

- Ansted, West VirginiaAnsted, West VirginiaAnsted is a town in Fayette County in the U.S. state of West Virginia. It is situated on high bluffs along U.S. Highway 60 on a portion of the Midland Trail a National Scenic Byway near Hawk's Nest overlooking the New River far below....

- Victoria, VirginiaVictoria, VirginiaVictoria is an incorporated town in Lunenburg County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,821 at the 2000 census.- History :Lunenburg County in the Southside region was established on May 1, 1746 in Great Britain's Virginia Colony from Brunswick County...

- Sewell's PointSewell's PointSewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and the Lafayette...