Dutch inventions and discoveries

Encyclopedia

The Dutch people

have a history

and tradition

in inventing and discovery

. Dutch scientists and engineers have made a remarkable contribution to human progress as a whole, from something as simple as the sawmill to microbiology and artificial organs.

1569 Mercator projection

The standard map projection for nautical purposes that supports rhumb lines.

1585 (est.) Yacht

Originally defined as a light, fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries. Later, yachts came to be perceived as luxury, or recreational vessels.

1590 Microscope

In 1590 the Dutchmen Hans and Zacharias Janssen

(Father and son) invented the first compound microscope. It would have a single glass lens of short focal length

for the objective, and another single glass lens for the eyepiece

or ocular. A resident of Delft, Anton van Leeuwenhoek

, effectively launched high-power microscopy using single-lens, simple microscopes. With these modest instruments he discovered the world of micro-organisms. Modern microscopes are far more complex, with multiple lens components in both objective and eyepiece assemblies. These multi-component lenses are designed to reduce aberrations

, particularly chromatic aberration

and spherical aberration

. In modern microscopes the mirror is replaced by a lamp unit providing stable, controllable illumination.

1594 Wind powered sawmill

Cornelis Corneliszoon

(Born 1550 in Uitgeest

- died 1600) was the inventor of the wind powered sawmill. Prior to the invention of sawmills, boards were rived and planed, or more often sawn by two men with a whipsaw using saddleblocks to hold the log and a pit for the pitman who worked below and got the benefit of the sawdust in his eyes. Sawing was slow and required strong and enduring men. The topsawer had to be the stronger of the two because the saw was pulled in turn by each man, and the lower had the advantage of gravity. The topsawyer also had to guide the saw so the board was of even thickness. This was often done by following a chalkline.

Early sawmills simply adapted the whipsaw to mechanical power, generally driven by a water wheel

to speed up the process. The circular motion of the wheel was changed to back-and-forth motion of the saw blade by a pitman thus introducing a term used in many mechanical applications. A pitman is similar to a crankshaft but used in reverse. A crankshaft converts back-and-forth motion to circular motion.

Generally only the saw was powered and the logs had to be loaded and moved by hand. An early improvement was the development of a movable carriage, also water powered, to steadily move the log through the saw blade.

1602 Multinational corporation

The Dutch East India Company

was the first multinational corporation and the first megacorporation. It was also the first corporation to issue shares of stock

and bonds

.

1606 Stock market

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange

was the first of its kind and it traded the first shares of stock

(from the Dutch East India Company

). Here, the Dutch also pioneered stock futures

, stock options, short selling

, debt-equity swaps, merchant banking, bonds

, unit trusts

and other speculative instruments

. Also, a speculative bubble

that crashed in 1695, and a change in fashion that unfolded and reverted in time with the market.

1608 Telescope

Hans Lippershey

Hans Lippershey

created and disseminated the first practical telescope. Crude telescopes and spyglasses may have been created much earlier, but Lippershey is believed to be the first to apply for a patent

for his design (beating out Jacob Metius

by a few weeks) and make it available for general use in 1608. He failed to receive a patent but was handsomely rewarded by the Dutch government

for copies of his design

. A description of Lippershey's instrument

quickly reached Galileo Galilei

, who created a working design in 1609, with which he made the observations found in his Sidereus Nuncius

of 1610.

There is a legend

that Lippershey's children actually discovered the telescope while playing with flawed lenses in their father's workshop

, but this may be apocrypha

l.

Lippershey crater

, on the Moon

, is named after him.

1620 Submarine

Cornelius Drebbel

, was the inventor of the first navigable submarine, while working for the Royal Navy

. Using William Bourne

's design from 1578, he manufactured a steerable submarine with a leather-covered wooden frame. Between 1620 and 1624 Drebbel successfully built and tested two more submarines, each one bigger than the last. The final (third) model had 6 oar

s and could carry 16 passengers. This model was demonstrated to King James I in person and several thousand Londoners. The submarine stayed submerged for three hours and could travel from Westminster

to Greenwich

and back, cruising at a depth of from 12 to 15 feet (4 to 5 metres). This submarine was tested many times in the Thames

, but never used in combat

1656 Pendulum clock

A pendulum clock uses a pendulum as its time base. From their invention until about 1930, the most accurate clock

s were pendulum

clocks. Pendulum clocks cannot operate on vehicles, because the acceleration

s of the vehicle drive the pendulum, causing inaccuracies. See marine chronometer

for a discussion of the problems of navigational clocks.The pendulum clock was invented by Christian Huygens in 1656, based on the pendulum introduced by Galileo Galilei

.

Pendulum clocks remained the mechanism of choice for accurate timekeeping for centuries, with the Fedchenko observatory clocks produced from after World War II

up to around 1960 marking the end of the pendulum era as time standard

s considered.

Pendulum clocks remain popular for domestic, decorative and antique use.

1673 Fire hose

In Holland, the Superintendent of the Fire Brigade, Jan van der Heyden

, and his son Nicholaas took firefighting to its next step with the fashioning of the first Fire hose

in 1673.

1739 Pyrometer

The pyrometer, invented by Pieter van Musschenbroek

, is a temperature

measuring device, which may consist of several different arrangements. A simple type of pyrometer uses a thermocouple

placed either in the furnace or on the item to be measured. The voltage output of the thermocouple is read from a digital or analog meter calibrated in degrees Celsius

(C) or Fahrenheit

(F). There are many different types of thermocouple available, and these can be used to measure temperatures from -200 °C to above 1500 °C.

1746 Leyden jar

]

]

The Leyden jar was the original capacitor, developed by Pieter van Musschenbroek

in the 18th century and used to conduct many early experiments in electricity.

The device was a glass jar coated inside and out with metal. The inner coating was connected to a rod that passed through the lid and ended in a metal ball. Typical designs consist of an electrode

and a plate, each of which stores an opposite charge. These two elements are conductive and are separated by an insulator (e.g., the glass dielectric

). The charge is stored at the surface of the elements, at the boundary with the dielectric.

1860 Kipp's apparatus

Kipp's apparatus, also called Kipp generator, is an apparatus designed for preparation of small volumes of gas

es. It was invented around 1860 by the Dutch pharmacist Petrus Jacobus Kipp

and widely used in chemical laboratories and for demonstrations in schools into the second half of the 20th century.

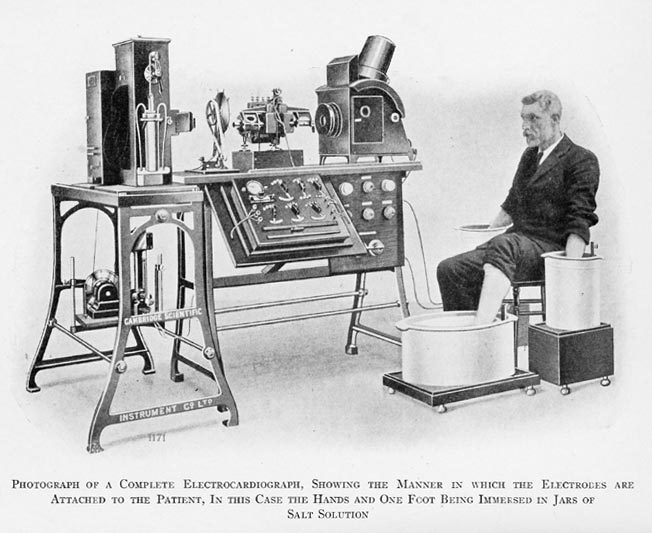

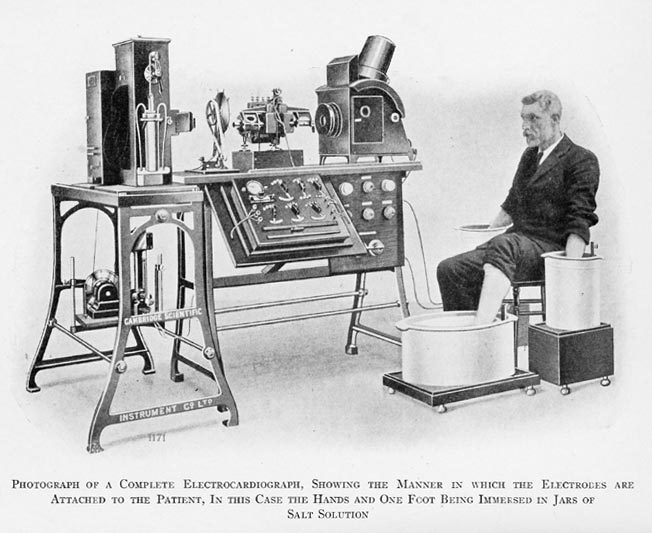

In the 19th century it became clear that the heart generated electricity. The first to systematically approach the heart from an electrical point-of-view was Augustus Waller, working in St Mary's Hospital

In the 19th century it became clear that the heart generated electricity. The first to systematically approach the heart from an electrical point-of-view was Augustus Waller, working in St Mary's Hospital

in Paddington

, London

. In 1911 he still saw little clinical application for his work. The breakthrough came when Willem Einthoven

, working in Leiden, The Netherlands, used the string galvanometer

invented by him in 1901, which was much more sensitive than the capillary electrometer that Waller used. Einthoven assigned the letters P, Q, R, S and T to the various deflections, and described the electrocardiographic features of a number of cardiovascular disorders. He was awarded the 1924 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery.

1903 Four-wheel drive

In 1903, the Dutch car manufacturer Spyker

introduces the first four-wheel drive car, as well as hill-climb racer, with internal combustion engine, the Spyker 60 H.P..

1926 Pentode

A pentode is an electronic device having five active electrode

s. The term most commonly applies to a three-grid vacuum tube

(thermionic valve), which was invented by the Dutchman Bernhard D.H. Tellegen in 1926.

The same holds in a typical microscope, i.e., although the phase variations introduced by the sample are preserved by the instrument (at least in the limit of the perfect imaging instrument) this information is lost in the process which measures the light. In order to make phase variations observable, it is necessary to combine the light passing through the sample with a reference so that the resulting interference reveals the phase structure of the sample.

This was first realized by Frits Zernike

during his study of diffraction gratings. During these studies he appreciated both that it is necessary to interfere with a reference beam, and that to maximise the contrast achieved with the technique, it is necessary to introduce a phase shift to this reference so that the no-phase-change condition gives rise to completely destructive interference.

He later realized that the same technique can be applied to optical microscopy. The necessary phase shift is introduced by rings etched accurately onto glass plates so that they introduce the required phase shift when inserted into the optical path of the microscope. When in use, this technique allows phase of the light passing through the object under study to be inferred from the intensity of the image produced by the microscope. This is the phase-contrast technique.

In optical microscopy many objects such as cell parts in protozoans, bacteria and sperm tails are essentially fully transparent unless stained (and therefore killed). The difference in densities and composition within these objects however often give rise to changes in the phase of light passing through them, hence they are sometimes called "phase objects". Using the phase-contrast technique makes these structures visible and allows their study with the specimen still alive.

This phase contrast technique proved to be such an advancement in microscopy that Zernike was awarded the Nobel prize

(physics) in 1953.

1939 Submarine snorkel

A submarine snorkel is a device that allows a submarine to operate submerged while still taking in air from above the surface. It was invented by the Dutchman J.J.Wichers shortly before World War II and copied by the Germans during the war for use by U-Boats. Its common military name is snort.

1939 Philishave

Philishave was the brand name for the electric shavers manufactured by the Philips Domestic Appliances and Personal Care unit of Philips

(in the U.S.A., the Norelco

name is used instead). The Philishave shaver was invented by Philips engineer Alexandre Horowitz

, who used rotating cutters instead of the reciprocating cutters that had been used in previous electric shavers.

1943 Artificial kidney (Hemodialysis

An artificial kidney is the machine and its related devices which allow to clean the blood of patients who have a temporary (acute) or an ongoing (chronic) failure of their kidneys. The first artificial kidney was developed by Willem Johan Kolff. The procedure of cleaning the blood by this means is called dialysis, a type of renal replacement therapy

which is used to provide an artificial replacement for lost kidney

function due to renal failure

. It is a life support

treatment and does not treat any kidney diseases.

1948 Gyrator

A gyrator is a passive

, linear, lossless, two-port

electrical network element

invented in 1948 by Dutchman Bernard D. H. Tellegen

as a hypothetical fifth linear element

after the resistor

, capacitor

, inductor

and ideal transformer.

Dutch

Dutch

company Gatsometer BV, founded by the 1950s rally driver Maurice Gatsonides

, invented the first traffic enforcement camera. Gatsonides wished to better monitor his speed around the corners of a race track and came up with the device in order to improve his time around the circuit http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199900/ldhansrd/pdvn/lds05/text/50608-10.htm. The company developed the first radar

for use with road traffic

, and is the world's largest supplier of speed camera systems. Because of this, in some countries speed cameras are sometimes referred to as "Gatso

s". They are also sometimes referred to as "photo radar", even though many of them do not use radar.

The first systems introduced in the late 1960s used film cameras to take their pictures. From the late 1990s, digital camera

s began to be introduced. Digital cameras can be fitted with a modem

or other electronic interface to transfer images to a central processing location automatically, so they have advantages over film cameras in speed of issuing fines, and operational monitoring. However, film-based systems still generally provide superior image quality in the variety of lighting conditions encountered on road

s, and in some jurisdictions are required by the courts due to the ease with which digital images may be modified. New film-based systems are still being sold.

1962 Compact Cassette

In 1962 Philips

In 1962 Philips

invented the compact audio cassette medium for audio storage

, introducing it in Europe in August 1963 (at the Berlin Radio Show

) and in the United States (under the Norelco

brand) in November 1964, with the trademark

name Compact Cassette.

1969 Laserdisc

Laserdisc technology, using a transparent disc, was invented by David Paul Gregg

in 1958 (and patented in 1961 and 1990). By 1969, Philips

had developed a videodisc in reflective mode, which has great advantages over the transparent mode. MCA

and Philips

decided to join their efforts. They first publicly demonstrated the videodisc in 1972. Laserdisc was first available on the market, in Atlanta, on December 15, 1978, two years after the VHS

VCR and four years before the CD

, which is based on Laserdisc technology. Philips produced the players and MCA the discs.

1979 Compact disc

The compact disc was jointly developed by Philips (Joop Sinjou) and Sony (Toshitada Doi

The compact disc was jointly developed by Philips (Joop Sinjou) and Sony (Toshitada Doi

). In the early 1970s, Philips

' researchers started experiments with "audio-only" optical discs, and at the end of the 1970s, Philips

, Sony

, and other companies presented prototypes of digital audio discs. Philips

publicly demonstrated a prototype of an optical digital audio disc at a press conference titled "Philips Introduce Compact Disc" in Eindhoven, The Netherlands on March 8, 1979.

discovered Bear Island, a week before their discovery of Spitsbergen.

1596 Spitsbergen

On 17 June 1596, Dutch explorers Willem Barentsz and Jacob van Heemskerk

discovered Spitsbergen while searching for the Northern Sea Route

.

1597 Novaya Zemlya effect

The first person to record the phenomenon was Gerrit de Veer

, a member of Willem Barentsz' ill-fated third expedition into the polar region. Novaya Zemlya

, the archipelago where de Veer first observed the phenomenon, lends its name to the effect.

1600 Falkland Islands

The first reliable sighting is usually attributed to the Dutch explorer Sebald de Weert

in 1600, who named the archipelago the Sebald Islands, a name they bore on Dutch maps into the 19th century.

1606 Australia

The first undisputed sighting

The first undisputed sighting

of Australia

by a European was made on 26 February 1606. The Dutch

vessel Duyfken

, captained by Willem Janszoon

, followed the coast of New Guinea

, missed Torres Strait

, and explored perhaps 350 km of western side of Cape York

, in the Gulf of Carpentaria

, believing the land was still part of New Guinea. The Dutch made one landing, but were promptly attacked by Aborigines and subsequently abandoned further exploration.

1614 Jan Mayen

After unconfirmed reports of Dutch discovery as early as 1611, the island was named after Dutchman Jan Jacobszoon May van Schellinkhout who visited the island in July 1614. As locations of these islands were kept secret by the whalers, Jan Mayen only got its current name in 1620.

1614 Long Island Sound

The first European to record the existence of Long Island Sound was the Dutch explorer Adriaen Block

, who entered the sound from the East River in 1614.

1614 Connecticut River

The first European to see the Connecticut River was the Dutch explorer Adriaen Block

in 1614.

1615 Staten Island

On 25 December 1615, Dutch explorers Jacob le Maire

and Willem Schouten

aboard the Eendracht, discovered Staten Island, close to Cape Horn.

1616 Cape Horn

On 29 January, 1616, the Dutch ship Eendracht with explorers Jacob le Maire

and Willem Schouten

sighted land they called Cape Horn, after the city of Hoorn in Holland. Aboard the Eendracht was the crew of the recently wrecked ship called Hoorn.

1616 Tonga

The Dutch ship Eendracht with explorers Jacob le Maire

and Willem Schouten

discovered Tonga on 21 April 1616.

1616 Hoorn Islands

The Dutch ship Eendracht with explorers Jacob le Maire

and Willem Schouten

discovered the Hoorn Islands on 28 April 1616.

1616 New Ireland (island)

The Dutch ship Eendracht with explorers Jacob le Maire

and Willem Schouten

discovered the New Ireland around May-July 1616.

1616 Schouten Islands

The Dutch ship Eendracht with explorers Jacob le Maire

and Willem Schouten

discovered the Schouten Islands on 24 July 1616.

1624 Hermite Islands

In February 1624, Dutch admiral Jacques l'Hermite

discovered the Hermite Islands at Cape Horn.

1642 Tasmania

In 1642, Abel Tasman

sailed from Mauritius and on 24 November, sighted Tasmania

. He named Tasmania Van Diemen's Land

, after Anthony van Diemen

, the Dutch East India Company

's Governor General at Batavia, who had commissioned his voyage. Tasman claimed Van Diemen's Land for the Netherlands.

1643 Sakhalin

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643.

1643 Kuril Islands

In the summer of 1643, the Castricum, under command of Maarten Gerritsz Vries

sailed by the southern Kuril Islands, visiting Kunashir, Iturup, and Urup, which they named "Company Island" and claimed for the Netherlands.

1655 Rings of Saturn

In 1655, Christiaan Huygens became the first person to suggest that Saturn was surrounded by a ring, after Galileo's much less advanced telescope had failed to show rings. Galileo had reported the anomaly as possibly 3 planets instead of one.

1674 Infusoria

Infusoria is a collective term for minute aquatic creatures like ciliate

, euglena

, paramecium

, protozoa

and unicellular algae

that exist in freshwater pond

water. However, in formal classification microorganism

called infusoria belongs to Kingdom Animal

ia, Phylum Protozoa

, Class Ciliates (Infusoria).They were first discovered by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek.

1676 Bacteria

The first bacteria were observed by Anton van Leeuwenhoek

in 1676 using a single-lens microscope of his own design. The creatures he saw were described as small creatures. The name bacterium was introduced much later, by Ehrenberg

in 1828, derived from the Greek word βακτηριον meaning "small stick". Because of the difficulty in describing individual bacteria and the importance of their discovery to fields such as medicine, biochemistry and geochemistry, the history of bacteria is generally described as the history of microbiology

.

σπερμα (seed) and ζων (alive) and more commonly known as a sperm cell, is the haploid

cell

that is the male gamete

. It joins an ovum

to form a zygote

. A zygote can grow into a new organism

, such as a human being. Sperm cells contribute half of the genetic information

to the diploid offspring. In mammals, the sex

of the offspring is determined by the sperm cells: a spermatozoon bearing a Y chromosome

will lead to a male

(XY) offspring, while one bearing an X chromosome will lead to a female

(XX) offspring ( the ovum

always provides an X chromosome). Sperm cells were first observed by a student of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

in 1677. Leeuwenhoek pictured sperm cells with great accuracy.

1722 Easter Island

On Easter Sunday, 5 April 1722, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen discovered Easter Island.

1722 Samoa

On 13 June 1722, after his discovery of Easter Island, Jacob Roggeveen discovered the Samoa islands.

1779 Orange River

The Orange River was named by Colonel Robert Gordon

, commander of the Dutch East India Company

garrison at Cape Town

, on a trip to the interior in 1779.

1779 Plant respiration and photosynthesis

Photosynthesis and plant respiration is an important biochemical

Photosynthesis and plant respiration is an important biochemical

process in which plant

s, algae, and some bacteria convert the energy of sunlight

to chemical energy. The process was discovered by Jan Ingenhousz

in 1779. The chemical energy is used to drive synthetic reactions such as the formation of sugars or the fixation of nitrogen into amino acids, the building blocks for protein synthesis. Ultimately, nearly all living things depend on energy produced from photosynthesis for their nourishment, making it vital to life on Earth

. It is also responsible for producing the oxygen

that makes up a large portion of the Earth's atmosphere

. Organisms that produce energy through photosynthesis are called photoautotrophs. Plants are the most visible representatives of photoautotrophs, but bacteria and algae also contribute to the conversion of free energy into usable energy.

Dutch people

The Dutch people are an ethnic group native to the Netherlands. They share a common culture and speak the Dutch language. Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Suriname, Chile, Brazil, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, and the United...

have a history

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

and tradition

Tradition

A tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, still maintained in the present, with origins in the past. Common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes , but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings...

in inventing and discovery

Discovery (observation)

Discovery is the act of detecting something new, or something "old" that had been unknown. With reference to science and academic disciplines, discovery is the observation of new phenomena, new actions, or new events and providing new reasoning to explain the knowledge gathered through such...

. Dutch scientists and engineers have made a remarkable contribution to human progress as a whole, from something as simple as the sawmill to microbiology and artificial organs.

1569 Mercator projectionMercator projectionThe Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Belgian geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator, in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as...

The standard map projection for nautical purposes that supports rhumb lines.1585 (est.) YachtYachtA yacht is a recreational boat or ship. The term originated from the Dutch Jacht meaning "hunt". It was originally defined as a light fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries...

Originally defined as a light, fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries. Later, yachts came to be perceived as luxury, or recreational vessels.1590 MicroscopeMicroscopeA microscope is an instrument used to see objects that are too small for the naked eye. The science of investigating small objects using such an instrument is called microscopy...

In 1590 the Dutchmen Hans and Zacharias JanssenZacharias Janssen

Zacharias Jansen was a Dutch spectacle-maker from Middelburg associated with the invention of the first optical telescope. Jansen is sometimes also credited for inventing the first truly compound microscope...

(Father and son) invented the first compound microscope. It would have a single glass lens of short focal length

Focal length

The focal length of an optical system is a measure of how strongly the system converges or diverges light. For an optical system in air, it is the distance over which initially collimated rays are brought to a focus...

for the objective, and another single glass lens for the eyepiece

Eyepiece

An eyepiece, or ocular lens, is a type of lens that is attached to a variety of optical devices such as telescopes and microscopes. It is so named because it is usually the lens that is closest to the eye when someone looks through the device. The objective lens or mirror collects light and brings...

or ocular. A resident of Delft, Anton van Leeuwenhoek

Anton van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek was a Dutch tradesman and scientist from Delft, Netherlands. He is commonly known as "the Father of Microbiology", and considered to be the first microbiologist...

, effectively launched high-power microscopy using single-lens, simple microscopes. With these modest instruments he discovered the world of micro-organisms. Modern microscopes are far more complex, with multiple lens components in both objective and eyepiece assemblies. These multi-component lenses are designed to reduce aberrations

Aberration in optical systems

Aberrations are departures of the performance of an optical system from the predictions of paraxial optics. Aberration leads to blurring of the image produced by an image-forming optical system. It occurs when light from one point of an object after transmission through the system does not converge...

, particularly chromatic aberration

Chromatic aberration

In optics, chromatic aberration is a type of distortion in which there is a failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same convergence point. It occurs because lenses have a different refractive index for different wavelengths of light...

and spherical aberration

Spherical aberration

thumb|right|Spherical aberration. A perfect lens focuses all incoming rays to a point on the [[Optical axis|optic axis]]. A real lens with spherical surfaces suffers from spherical aberration: it focuses rays more tightly if they enter it far from the optic axis than if they enter closer to the...

. In modern microscopes the mirror is replaced by a lamp unit providing stable, controllable illumination.

1594 Wind powered sawmillSawmillA sawmill is a facility where logs are cut into boards.-Sawmill process:A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago; a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end....

Cornelis CorneliszoonCornelis Corneliszoon

Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest, or Krelis Lootjes was a Dutch windmill owner from Uitgeest who invented the wind-powered sawmill, which made the conversion of log timber into planks 30 times faster than before.-Biography:...

(Born 1550 in Uitgeest

Uitgeest

Uitgeest is a municipality and a town in the Netherlands, in the province of North Holland.-Population centres :The municipality of Uitgeest consists of the following cities, towns, villages and/or districts: Assum, Busch en Dam, Groot Dorregeest, Uitgeest....

- died 1600) was the inventor of the wind powered sawmill. Prior to the invention of sawmills, boards were rived and planed, or more often sawn by two men with a whipsaw using saddleblocks to hold the log and a pit for the pitman who worked below and got the benefit of the sawdust in his eyes. Sawing was slow and required strong and enduring men. The topsawer had to be the stronger of the two because the saw was pulled in turn by each man, and the lower had the advantage of gravity. The topsawyer also had to guide the saw so the board was of even thickness. This was often done by following a chalkline.

Early sawmills simply adapted the whipsaw to mechanical power, generally driven by a water wheel

Water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of free-flowing or falling water into useful forms of power. A water wheel consists of a large wooden or metal wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving surface...

to speed up the process. The circular motion of the wheel was changed to back-and-forth motion of the saw blade by a pitman thus introducing a term used in many mechanical applications. A pitman is similar to a crankshaft but used in reverse. A crankshaft converts back-and-forth motion to circular motion.

Generally only the saw was powered and the logs had to be loaded and moved by hand. An early improvement was the development of a movable carriage, also water powered, to steadily move the log through the saw blade.

1602 Multinational corporationMultinational corporationA multi national corporation or enterprise , is a corporation or an enterprise that manages production or delivers services in more than one country. It can also be referred to as an international corporation...

The Dutch East India CompanyDutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia...

was the first multinational corporation and the first megacorporation. It was also the first corporation to issue shares of stock

Stock

The capital stock of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders. It serves as a security for the creditors of a business since it cannot be withdrawn to the detriment of the creditors...

and bonds

Bond (finance)

In finance, a bond is a debt security, in which the authorized issuer owes the holders a debt and, depending on the terms of the bond, is obliged to pay interest to use and/or to repay the principal at a later date, termed maturity...

.

1606 Stock marketStock marketA stock market or equity market is a public entity for the trading of company stock and derivatives at an agreed price; these are securities listed on a stock exchange as well as those only traded privately.The size of the world stock market was estimated at about $36.6 trillion...

The Amsterdam Stock ExchangeAmsterdam Stock Exchange

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange is the former name for the stock exchange based in Amsterdam. It merged on 22 September 2000 with the Brussels Stock Exchange and the Paris Stock Exchange to form Euronext, and is now known as Euronext Amsterdam.-History:...

was the first of its kind and it traded the first shares of stock

Stock

The capital stock of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders. It serves as a security for the creditors of a business since it cannot be withdrawn to the detriment of the creditors...

(from the Dutch East India Company

Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia...

). Here, the Dutch also pioneered stock futures

Futures contract

In finance, a futures contract is a standardized contract between two parties to exchange a specified asset of standardized quantity and quality for a price agreed today with delivery occurring at a specified future date, the delivery date. The contracts are traded on a futures exchange...

, stock options, short selling

Short selling

In finance, short selling is the practice of selling assets, usually securities, that have been borrowed from a third party with the intention of buying identical assets back at a later date to return to that third party...

, debt-equity swaps, merchant banking, bonds

Bond (finance)

In finance, a bond is a debt security, in which the authorized issuer owes the holders a debt and, depending on the terms of the bond, is obliged to pay interest to use and/or to repay the principal at a later date, termed maturity...

, unit trusts

Trust law

In common law legal systems, a trust is a relationship whereby property is held by one party for the benefit of another...

and other speculative instruments

Speculation

In finance, speculation is a financial action that does not promise safety of the initial investment along with the return on the principal sum...

. Also, a speculative bubble

Stock market bubble

A stock market bubble is a type of economic bubble taking place in stock markets when market participants drive stock prices above their value in relation to some system of stock valuation....

that crashed in 1695, and a change in fashion that unfolded and reverted in time with the market.

1608 TelescopeTelescopeA telescope is an instrument that aids in the observation of remote objects by collecting electromagnetic radiation . The first known practical telescopes were invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 1600s , using glass lenses...

Hans Lippershey

Hans Lippershey , also known as Johann Lippershey or Lipperhey, was a German-Dutch lensmaker commonly associated with the invention of the telescope, although it is unclear if he was the first to build one.-Biography:...

created and disseminated the first practical telescope. Crude telescopes and spyglasses may have been created much earlier, but Lippershey is believed to be the first to apply for a patent

Patent

A patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

for his design (beating out Jacob Metius

Jacob Metius

Jacob Metius was a Dutch instrument-maker and a specialist in grinding lenses. He was born in Alkmaar and was the brother of Adriaan Adriaanszoon...

by a few weeks) and make it available for general use in 1608. He failed to receive a patent but was handsomely rewarded by the Dutch government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...

for copies of his design

Design

Design as a noun informally refers to a plan or convention for the construction of an object or a system while “to design” refers to making this plan...

. A description of Lippershey's instrument

Optical instrument

An optical instrument either processes light waves to enhance an image for viewing, or analyzes light waves to determine one of a number of characteristic properties.-Image enhancement:...

quickly reached Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei , was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations and support for Copernicanism...

, who created a working design in 1609, with which he made the observations found in his Sidereus Nuncius

Sidereus Nuncius

Sidereus Nuncius is a short treatise published in New Latin by Galileo Galilei in March 1610. It was the first scientific treatise based on observations made through a telescope...

of 1610.

There is a legend

Legend

A legend is a narrative of human actions that are perceived both by teller and listeners to take place within human history and to possess certain qualities that give the tale verisimilitude...

that Lippershey's children actually discovered the telescope while playing with flawed lenses in their father's workshop

Workshop

A workshop is a room or building which provides both the area and tools that may be required for the manufacture or repair of manufactured goods...

, but this may be apocrypha

Apocrypha

The term apocrypha is used with various meanings, including "hidden", "esoteric", "spurious", "of questionable authenticity", ancient Chinese "revealed texts and objects" and "Christian texts that are not canonical"....

l.

Lippershey crater

Lippershey (crater)

Lippershey is a relatively tiny lunar impact crater located in the southeast section of the Mare Nubium. It is a circular, cup-shaped feature surrounded by the lunar mare...

, on the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

, is named after him.

1620 SubmarineSubmarineA submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

Cornelius DrebbelCornelius Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel was the Dutch builder of the first navigable submarine in 1620. Drebbel was an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, optics and chemistry....

, was the inventor of the first navigable submarine, while working for the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. Using William Bourne

William Bourne (mathematician)

William Bourne was an English mathematician, innkeeper and former Royal Navy gunner who invented the first navigable submarine and wrote important navigational manuals...

's design from 1578, he manufactured a steerable submarine with a leather-covered wooden frame. Between 1620 and 1624 Drebbel successfully built and tested two more submarines, each one bigger than the last. The final (third) model had 6 oar

Oar

An oar is an implement used for water-borne propulsion. Oars have a flat blade at one end. Oarsmen grasp the oar at the other end. The difference between oars and paddles are that paddles are held by the paddler, and are not connected with the vessel. Oars generally are connected to the vessel by...

s and could carry 16 passengers. This model was demonstrated to King James I in person and several thousand Londoners. The submarine stayed submerged for three hours and could travel from Westminster

Westminster

Westminster is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster, England. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames, southwest of the City of London and southwest of Charing Cross...

to Greenwich

Greenwich

Greenwich is a district of south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich.Greenwich is best known for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich Meridian and Greenwich Mean Time...

and back, cruising at a depth of from 12 to 15 feet (4 to 5 metres). This submarine was tested many times in the Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

, but never used in combat

1656 Pendulum clockPendulum clockA pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is a resonant device; it swings back and forth in a precise time interval dependent on its length, and resists swinging at other rates...

A pendulum clock uses a pendulum as its time base. From their invention until about 1930, the most accurate clockClock

A clock is an instrument used to indicate, keep, and co-ordinate time. The word clock is derived ultimately from the Celtic words clagan and clocca meaning "bell". A silent instrument missing such a mechanism has traditionally been known as a timepiece...

s were pendulum

Pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced from its resting equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the equilibrium position...

clocks. Pendulum clocks cannot operate on vehicles, because the acceleration

Acceleration

In physics, acceleration is the rate of change of velocity with time. In one dimension, acceleration is the rate at which something speeds up or slows down. However, since velocity is a vector, acceleration describes the rate of change of both the magnitude and the direction of velocity. ...

s of the vehicle drive the pendulum, causing inaccuracies. See marine chronometer

Marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a clock that is precise and accurate enough to be used as a portable time standard; it can therefore be used to determine longitude by means of celestial navigation...

for a discussion of the problems of navigational clocks.The pendulum clock was invented by Christian Huygens in 1656, based on the pendulum introduced by Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei , was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations and support for Copernicanism...

.

Pendulum clocks remained the mechanism of choice for accurate timekeeping for centuries, with the Fedchenko observatory clocks produced from after World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

up to around 1960 marking the end of the pendulum era as time standard

Time standard

A time standard is a specification for measuring time: either the rate at which time passes; or points in time; or both. In modern times, several time specifications have been officially recognized as standards, where formerly they were matters of custom and practice. An example of a kind of time...

s considered.

Pendulum clocks remain popular for domestic, decorative and antique use.

1673 Fire hoseFire hoseA fire hose is a high-pressure hose used to carry water or other fire retardant to a fire to extinguish it. Outdoors, it is attached either to a fire engine or a fire hydrant. Indoors, it can be permanently attached to a building's standpipe or plumbing system...

In Holland, the Superintendent of the Fire Brigade, Jan van der HeydenJan van der Heyden

Jan van der Heyden was a Dutch Baroque-era painter, draughtsman, printmaker, a mennonite and inventor who significantly contributed to contemporary firefighting. He improved the fire hose in 1672, with his brother Nicolaes, who was a hydraulic engineer...

, and his son Nicholaas took firefighting to its next step with the fashioning of the first Fire hose

Fire hose

A fire hose is a high-pressure hose used to carry water or other fire retardant to a fire to extinguish it. Outdoors, it is attached either to a fire engine or a fire hydrant. Indoors, it can be permanently attached to a building's standpipe or plumbing system...

in 1673.

1739 PyrometerPyrometerA pyrometer is a non-contacting device that intercepts and measures thermal radiation, a process known as pyrometry.This device can be used to determine the temperature of an object's surface....

The pyrometer, invented by Pieter van MusschenbroekPieter van Musschenbroek

Pieter van Musschenbroek was a Dutch scientist. He was a professor in Duisburg, Utrecht, and Leiden, where he held positions in mathematics, philosophy, medicine, and astrology. He is credited with the invention of the first capacitor in 1746: the Leyden jar. He performed pioneering work on the...

, is a temperature

Temperature

Temperature is a physical property of matter that quantitatively expresses the common notions of hot and cold. Objects of low temperature are cold, while various degrees of higher temperatures are referred to as warm or hot...

measuring device, which may consist of several different arrangements. A simple type of pyrometer uses a thermocouple

Thermocouple

A thermocouple is a device consisting of two different conductors that produce a voltage proportional to a temperature difference between either end of the pair of conductors. Thermocouples are a widely used type of temperature sensor for measurement and control and can also be used to convert a...

placed either in the furnace or on the item to be measured. The voltage output of the thermocouple is read from a digital or analog meter calibrated in degrees Celsius

Celsius

Celsius is a scale and unit of measurement for temperature. It is named after the Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius , who developed a similar temperature scale two years before his death...

(C) or Fahrenheit

Fahrenheit

Fahrenheit is the temperature scale proposed in 1724 by, and named after, the German physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit . Within this scale, the freezing of water into ice is defined at 32 degrees, while the boiling point of water is defined to be 212 degrees...

(F). There are many different types of thermocouple available, and these can be used to measure temperatures from -200 °C to above 1500 °C.

1746 Leyden jarLeyden jarA Leyden jar, or Leiden jar, is a device that "stores" static electricity between two electrodes on the inside and outside of a jar. It was invented independently by German cleric Ewald Georg von Kleist on 11 October 1745 and by Dutch scientist Pieter van Musschenbroek of Leiden in 1745–1746. The...

The Leyden jar was the original capacitor, developed by Pieter van Musschenbroek

Pieter van Musschenbroek

Pieter van Musschenbroek was a Dutch scientist. He was a professor in Duisburg, Utrecht, and Leiden, where he held positions in mathematics, philosophy, medicine, and astrology. He is credited with the invention of the first capacitor in 1746: the Leyden jar. He performed pioneering work on the...

in the 18th century and used to conduct many early experiments in electricity.

The device was a glass jar coated inside and out with metal. The inner coating was connected to a rod that passed through the lid and ended in a metal ball. Typical designs consist of an electrode

Electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit...

and a plate, each of which stores an opposite charge. These two elements are conductive and are separated by an insulator (e.g., the glass dielectric

Dielectric

A dielectric is an electrical insulator that can be polarized by an applied electric field. When a dielectric is placed in an electric field, electric charges do not flow through the material, as in a conductor, but only slightly shift from their average equilibrium positions causing dielectric...

). The charge is stored at the surface of the elements, at the boundary with the dielectric.

1860 Kipp's apparatusKipp's apparatusKipp's apparatus, also called Kipp generator, is an apparatus designed for preparation of small volumes of gases. It was invented around 1860 by the Dutch pharmacist Petrus Jacobus Kipp and widely used in chemical laboratories and for demonstrations in schools into the second half of the 20th...

Kipp's apparatus, also called Kipp generator, is an apparatus designed for preparation of small volumes of gasGas

Gas is one of the three classical states of matter . Near absolute zero, a substance exists as a solid. As heat is added to this substance it melts into a liquid at its melting point , boils into a gas at its boiling point, and if heated high enough would enter a plasma state in which the electrons...

es. It was invented around 1860 by the Dutch pharmacist Petrus Jacobus Kipp

Petrus Jacobus Kipp

Petrus Jacobus Kipp was a Dutch apothecary, chemist and instrument maker. He became known as the inventor of the Kipp apparatus, chemistry equipment for the development of gases.-Biography:...

and widely used in chemical laboratories and for demonstrations in schools into the second half of the 20th century.

1903 Electrocardiograph (ECG)

St Mary's Hospital (London)

St Mary's Hospital is a hospital located in Paddington, London, England that was founded in 1845. Since the UK's first academic health science centre was created in 2008, it is operated by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, which also operates Charing Cross Hospital, Hammersmith Hospital,...

in Paddington

Paddington

Paddington is a district within the City of Westminster, in central London, England. Formerly a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. In 1911 he still saw little clinical application for his work. The breakthrough came when Willem Einthoven

Willem Einthoven

Willem Einthoven was a Dutch doctor and physiologist. He invented the first practical electrocardiogram in 1903 and received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1924 for it....

, working in Leiden, The Netherlands, used the string galvanometer

String galvanometer

The string galvanometer was one of the earliest instruments capable of detecting and recording the very small electrical currents produced by the human heart and provided the first practical Electrocardiogram . The original machines achieved "such amazing technical perfection that many modern day...

invented by him in 1901, which was much more sensitive than the capillary electrometer that Waller used. Einthoven assigned the letters P, Q, R, S and T to the various deflections, and described the electrocardiographic features of a number of cardiovascular disorders. He was awarded the 1924 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery.

1903 Four-wheel driveFour-wheel driveFour-wheel drive, 4WD, or 4×4 is a four-wheeled vehicle with a drivetrain that allows all four wheels to receive torque from the engine simultaneously...

with internal combustion engine

In 1903, the Dutch car manufacturer SpykerSpyker

Spyker was a Dutch car manufacturer, started in 1880 by coachbuilders Jacobus and Hendrik-Jan Spijker, but to be able to market the brand better in foreign countries, in 1903 the 'ij' was changed into 'y'...

introduces the first four-wheel drive car, as well as hill-climb racer, with internal combustion engine, the Spyker 60 H.P..

1926 PentodePentodeA pentode is an electronic device having five active electrodes. The term most commonly applies to a three-grid vacuum tube , which was invented by the Dutchman Bernhard D.H. Tellegen in 1926...

A pentode is an electronic device having five active electrodeElectrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit...

s. The term most commonly applies to a three-grid vacuum tube

Vacuum tube

In electronics, a vacuum tube, electron tube , or thermionic valve , reduced to simply "tube" or "valve" in everyday parlance, is a device that relies on the flow of electric current through a vacuum...

(thermionic valve), which was invented by the Dutchman Bernhard D.H. Tellegen in 1926.

1933 Phase contrast microscope

As light travels through a medium other than vacuum, interaction with this medium causes its amplitude and phase to change in a way which depends on properties of the medium. Changes in amplitude give rise to familiar absorption of light which gives rise to colors when it is wavelength dependent. The human eye measures only the energy of light arriving on the retina, so changes in phase are not easily observed, yet often these changes in phase carry a large amount of information.The same holds in a typical microscope, i.e., although the phase variations introduced by the sample are preserved by the instrument (at least in the limit of the perfect imaging instrument) this information is lost in the process which measures the light. In order to make phase variations observable, it is necessary to combine the light passing through the sample with a reference so that the resulting interference reveals the phase structure of the sample.

This was first realized by Frits Zernike

Frits Zernike

Frits Zernike was a Dutch physicist and winner of the Nobel prize for physics in 1953 for his invention of the phase contrast microscope, an instrument that permits the study of internal cell structure without the need to stain and thus kill the cells....

during his study of diffraction gratings. During these studies he appreciated both that it is necessary to interfere with a reference beam, and that to maximise the contrast achieved with the technique, it is necessary to introduce a phase shift to this reference so that the no-phase-change condition gives rise to completely destructive interference.

He later realized that the same technique can be applied to optical microscopy. The necessary phase shift is introduced by rings etched accurately onto glass plates so that they introduce the required phase shift when inserted into the optical path of the microscope. When in use, this technique allows phase of the light passing through the object under study to be inferred from the intensity of the image produced by the microscope. This is the phase-contrast technique.

In optical microscopy many objects such as cell parts in protozoans, bacteria and sperm tails are essentially fully transparent unless stained (and therefore killed). The difference in densities and composition within these objects however often give rise to changes in the phase of light passing through them, hence they are sometimes called "phase objects". Using the phase-contrast technique makes these structures visible and allows their study with the specimen still alive.

This phase contrast technique proved to be such an advancement in microscopy that Zernike was awarded the Nobel prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

(physics) in 1953.

1939 Submarine snorkelSubmarine snorkelA submarine snorkel is a device which allows a submarine to operate submerged while still taking in air from above the surface. Navy personnel often refer to it as the snort.-History:...

A submarine snorkel is a device that allows a submarine to operate submerged while still taking in air from above the surface. It was invented by the Dutchman J.J.Wichers shortly before World War II and copied by the Germans during the war for use by U-Boats. Its common military name is snort.1939 PhilishavePhilishavePhilishave was the brand name for the electric shavers manufactured by the Philips Domestic Appliances and Personal Care unit of Philips . In recent years, Philips had extended the Philishave brand to include hair clippers, beard trimmers and beard shapers...

Philishave was the brand name for the electric shavers manufactured by the Philips Domestic Appliances and Personal Care unit of PhilipsPhilips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

(in the U.S.A., the Norelco

Norelco

Norelco is the American brand name for electric shavers and other personal care products made by the Consumer Lifestyle division of Philips.-Norelco and Philishave:...

name is used instead). The Philishave shaver was invented by Philips engineer Alexandre Horowitz

Alexandre Horowitz

Alexandre Horowitz was a Belgian-born Dutch technical engineer and inventor.Alexandre "Sacha" Horowitz was born in 1904 in Antwerp, to parents of East-European Jewish heritage, and lived from 1914 in The Netherlands until his death in 1982...

, who used rotating cutters instead of the reciprocating cutters that had been used in previous electric shavers.

1943 Artificial kidney (HemodialysisHemodialysisIn medicine, hemodialysis is a method for removing waste products such as creatinine and urea, as well as free water from the blood when the kidneys are in renal failure. Hemodialysis is one of three renal replacement therapies .Hemodialysis can be an outpatient or inpatient therapy...

)

An artificial kidney is the machine and its related devices which allow to clean the blood of patients who have a temporary (acute) or an ongoing (chronic) failure of their kidneys. The first artificial kidney was developed by Willem Johan Kolff. The procedure of cleaning the blood by this means is called dialysis, a type of renal replacement therapyRenal replacement therapy

Renal replacement therapy is a term used to encompass life-supporting treatments for renal failure.It includes:*hemodialysis,*peritoneal dialysis,*hemofiltration and*renal transplantation.These treatments will not cure chronic kidney disease...

which is used to provide an artificial replacement for lost kidney

Kidney

The kidneys, organs with several functions, serve essential regulatory roles in most animals, including vertebrates and some invertebrates. They are essential in the urinary system and also serve homeostatic functions such as the regulation of electrolytes, maintenance of acid–base balance, and...

function due to renal failure

Renal failure

Renal failure or kidney failure describes a medical condition in which the kidneys fail to adequately filter toxins and waste products from the blood...

. It is a life support

Life support

Life support, in medicine is a broad term that applies to any therapy used to sustain a patient's life while they are critically ill or injured. There are many therapies and techniques that may be used by clinicians to achieve the goal of sustaining life...

treatment and does not treat any kidney diseases.

1948 GyratorGyratorA gyrator is a passive, linear, lossless, two-port electrical network element proposed in 1948 by Tellegen as a hypothetical fifth linear element after the resistor, capacitor, inductor and ideal transformer. Unlike the four conventional elements, the gyrator is non-reciprocal...

A gyrator is a passivePassivity (engineering)

Passivity is a property of engineering systems, used in a variety of engineering disciplines, but most commonly found in analog electronics and control systems...

, linear, lossless, two-port

Two-port network

A two-port network is an electrical circuit or device with two pairs of terminals connected together internally by an electrical network...

electrical network element

Lumped element model

The lumped element model simplifies the description of the behaviour of spatially distributed physical systems into a topology consisting of discrete entities that approximate the behaviour of the distributed system under certain assumptions...

invented in 1948 by Dutchman Bernard D. H. Tellegen

Bernard D. H. Tellegen

Bernard D.H. Tellegen was a Dutch electrical engineer and inventor of the penthode and the gyrator...

as a hypothetical fifth linear element

Linear element

In an electric circuit, a linear element is an electrical element with a linear relationship between current and [output[voltage]]. Resistors are the most common example of a linear element; other examples include capacitors, inductors, and transformers....

after the resistor

Resistor

A linear resistor is a linear, passive two-terminal electrical component that implements electrical resistance as a circuit element.The current through a resistor is in direct proportion to the voltage across the resistor's terminals. Thus, the ratio of the voltage applied across a resistor's...

, capacitor

Capacitor

A capacitor is a passive two-terminal electrical component used to store energy in an electric field. The forms of practical capacitors vary widely, but all contain at least two electrical conductors separated by a dielectric ; for example, one common construction consists of metal foils separated...

, inductor

Inductor

An inductor is a passive two-terminal electrical component used to store energy in a magnetic field. An inductor's ability to store magnetic energy is measured by its inductance, in units of henries...

and ideal transformer.

1958 Traffic enforcement camera

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

company Gatsometer BV, founded by the 1950s rally driver Maurice Gatsonides

Maurice Gatsonides

Maurice Gatsonides was a Dutch rally driver and inventor. Gatsonides was born in Central Java in the former Dutch East Indies...

, invented the first traffic enforcement camera. Gatsonides wished to better monitor his speed around the corners of a race track and came up with the device in order to improve his time around the circuit http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199900/ldhansrd/pdvn/lds05/text/50608-10.htm. The company developed the first radar

Radar

Radar is an object-detection system which uses radio waves to determine the range, altitude, direction, or speed of objects. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weather formations, and terrain. The radar dish or antenna transmits pulses of radio...

for use with road traffic

Traffic

Traffic on roads may consist of pedestrians, ridden or herded animals, vehicles, streetcars and other conveyances, either singly or together, while using the public way for purposes of travel...

, and is the world's largest supplier of speed camera systems. Because of this, in some countries speed cameras are sometimes referred to as "Gatso

Gatso

Gatso is the brand that Gatsometer BV use on their traffic enforcement cameras, most notably their speed cameras and red light cameras. The most commonly encountered Gatso speed cameras emit radar beams to measure the speed of a passing vehicle...

s". They are also sometimes referred to as "photo radar", even though many of them do not use radar.

The first systems introduced in the late 1960s used film cameras to take their pictures. From the late 1990s, digital camera

Digital camera

A digital camera is a camera that takes video or still photographs, or both, digitally by recording images via an electronic image sensor. It is the main device used in the field of digital photography...

s began to be introduced. Digital cameras can be fitted with a modem

Modem

A modem is a device that modulates an analog carrier signal to encode digital information, and also demodulates such a carrier signal to decode the transmitted information. The goal is to produce a signal that can be transmitted easily and decoded to reproduce the original digital data...

or other electronic interface to transfer images to a central processing location automatically, so they have advantages over film cameras in speed of issuing fines, and operational monitoring. However, film-based systems still generally provide superior image quality in the variety of lighting conditions encountered on road

Road

A road is a thoroughfare, route, or way on land between two places, which typically has been paved or otherwise improved to allow travel by some conveyance, including a horse, cart, or motor vehicle. Roads consist of one, or sometimes two, roadways each with one or more lanes and also any...

s, and in some jurisdictions are required by the courts due to the ease with which digital images may be modified. New film-based systems are still being sold.

1962 Compact CassetteCompact CassetteThe Compact Cassette, often referred to as audio cassette, cassette tape, cassette, or simply tape, is a magnetic tape sound recording format. It was designed originally for dictation, but improvements in fidelity led the Compact Cassette to supplant the Stereo 8-track cartridge and reel-to-reel...

Philips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

invented the compact audio cassette medium for audio storage

Sound recording and reproduction

Sound recording and reproduction is an electrical or mechanical inscription and re-creation of sound waves, such as spoken voice, singing, instrumental music, or sound effects. The two main classes of sound recording technology are analog recording and digital recording...

, introducing it in Europe in August 1963 (at the Berlin Radio Show

Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin

The IFA or Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin is one of the oldest industrial exhibitions in Germany. Between 1924 and 1939 it was an annual event, but as from 1950 it was organized on a two yearly basis until 2005. Since then it has become an annual event again, held in September...

) and in the United States (under the Norelco

Norelco

Norelco is the American brand name for electric shavers and other personal care products made by the Consumer Lifestyle division of Philips.-Norelco and Philishave:...

brand) in November 1964, with the trademark

Trademark

A trademark, trade mark, or trade-mark is a distinctive sign or indicator used by an individual, business organization, or other legal entity to identify that the products or services to consumers with which the trademark appears originate from a unique source, and to distinguish its products or...

name Compact Cassette.

1969 LaserdiscLaserdiscLaserDisc was a home video format and the first commercial optical disc storage medium. Initially licensed, sold, and marketed as MCA DiscoVision in North America in 1978, the technology was previously referred to interally as Optical Videodisc System, Reflective Optical Videodisc, Laser Optical...

Laserdisc technology, using a transparent disc, was invented by David Paul GreggDavid Paul Gregg

Dr. David Paul Gregg was the inventor of the optical disc . Gregg was inspired to create the optical disc in 1958. He originally had it patented as the "Videodisk" in 1961. In 1968 his patents were purchased by MCA who help develop the technology further...

in 1958 (and patented in 1961 and 1990). By 1969, Philips

Philips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

had developed a videodisc in reflective mode, which has great advantages over the transparent mode. MCA

Music Corporation of America

MCA, Inc. was an American talent agency. Initially starting in the music business, they would next become a dominant force in the film business, and later expanded into the television business...

and Philips

Philips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

decided to join their efforts. They first publicly demonstrated the videodisc in 1972. Laserdisc was first available on the market, in Atlanta, on December 15, 1978, two years after the VHS

VHS

The Video Home System is a consumer-level analog recording videocassette standard developed by Victor Company of Japan ....

VCR and four years before the CD

Compact Disc

The Compact Disc is an optical disc used to store digital data. It was originally developed to store and playback sound recordings exclusively, but later expanded to encompass data storage , write-once audio and data storage , rewritable media , Video Compact Discs , Super Video Compact Discs ,...

, which is based on Laserdisc technology. Philips produced the players and MCA the discs.

1979 Compact discCompact DiscThe Compact Disc is an optical disc used to store digital data. It was originally developed to store and playback sound recordings exclusively, but later expanded to encompass data storage , write-once audio and data storage , rewritable media , Video Compact Discs , Super Video Compact Discs ,...

Toshitada Doi

is a Japanese electrical engineer, who played a significant role in the digital audio revolution. He received a degree in electrical engineering from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1964, and a PhD from Tohoku University in 1972. He joined Sony Japan in 1964. He started the first digital audio...

). In the early 1970s, Philips

Philips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

' researchers started experiments with "audio-only" optical discs, and at the end of the 1970s, Philips

Philips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

, Sony

Sony

, commonly referred to as Sony, is a Japanese multinational conglomerate corporation headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan and the world's fifth largest media conglomerate measured by revenues....

, and other companies presented prototypes of digital audio discs. Philips

Philips

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. , more commonly known as Philips, is a multinational Dutch electronics company....

publicly demonstrated a prototype of an optical digital audio disc at a press conference titled "Philips Introduce Compact Disc" in Eindhoven, The Netherlands on March 8, 1979.

1594 Orange Islands

During his first journey in 1594, Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz discovered the Orange Islands.1596 Bear Island

On 10 June 1596, Dutch explorers Willem Barentsz and Jacob van HeemskerkJacob van Heemskerk

Jacob van Heemskerk was a Dutch explorer and later admiral commanding the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Gibraltar.-Arctic exploration:...

discovered Bear Island, a week before their discovery of Spitsbergen.

1596 SpitsbergenSpitsbergenSpitsbergen is the largest and only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in Norway. Constituting the western-most bulk of the archipelago, it borders the Arctic Ocean, the Norwegian Sea and the Greenland Sea...

On 17 June 1596, Dutch explorers Willem Barentsz and Jacob van HeemskerkJacob van Heemskerk

Jacob van Heemskerk was a Dutch explorer and later admiral commanding the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Gibraltar.-Arctic exploration:...

discovered Spitsbergen while searching for the Northern Sea Route

Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route is a shipping lane officially defined by Russian legislation from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean specifically running along the Russian Arctic coast from Murmansk on the Barents Sea, along Siberia, to the Bering Strait and Far East. The entire route lies in Arctic...

.

1597 Novaya Zemlya effectNovaya Zemlya effectThe Novaya Zemlya effect is a polar mirage caused by high refraction of sunlight between atmospheric thermoclines. The Novaya Zemlya effect will give the impression that the sun is rising earlier than it actually should and depending on the meteorological situation the effect will present the sun...

The first person to record the phenomenon was Gerrit de VeerGerrit de Veer

Gerrit de Veer was a Dutch officer on Willem Barentsz' third voyage in search of the Northeast passage. De Veer kept a diary of the voyage and in 1597 was the first person to observe and record the Novaya Zemlya effect, and the first westerner to observe hypervitaminosis A caused by consuming...

, a member of Willem Barentsz' ill-fated third expedition into the polar region. Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya , also known in Dutch as Nova Zembla and in Norwegian as , is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean in the north of Russia and the extreme northeast of Europe, the easternmost point of Europe lying at Cape Flissingsky on the northern island...

, the archipelago where de Veer first observed the phenomenon, lends its name to the effect.

1600 Falkland IslandsFalkland IslandsThe Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

The first reliable sighting is usually attributed to the Dutch explorer Sebald de WeertSebald de Weert

Sebald or Sebalt de Weert was a Dutch captain and vice-admiral of the Dutch East India Company...

in 1600, who named the archipelago the Sebald Islands, a name they bore on Dutch maps into the 19th century.

1606 AustraliaAustraliaAustralia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

Janszoon voyage of 1606

Willem Janszoon made the first recorded European landing on the Australian continent in 1606, sailing from Bantam, Java in the Duyfken. As an employee of the Dutch East India Company, Janszoon had been instructed to explore the coast of New Guinea in search of economic opportunities...

of Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

by a European was made on 26 February 1606. The Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

vessel Duyfken

Duyfken

Duyfken was a small Dutch ship built in the Netherlands. She was a fast, lightly armed ship probably intended for shallow water, small valuable cargoes, bringing messages, sending provisions, or privateering...

, captained by Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon , Dutch navigator and colonial governor, is probably the first European known to have seen the coast of Australia. His name is sometimes abbreviated to Willem Jansz....

, followed the coast of New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

, missed Torres Strait

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait is a body of water which lies between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is approximately wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost continental extremity of the Australian state of Queensland...