Great Purge

Encyclopedia

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression

and persecution

in the Soviet Union

orchestrated by Joseph Stalin

from 1936 to 1938. It involved a large-scale purge of the Communist Party and government officials

, repression of peasants, Red Army

leadership, and the persecution of unaffiliated persons, characterized by widespread police surveillance, widespread suspicion of "saboteurs", imprisonment, and arbitrary executions.

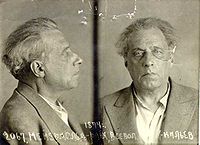

In Russian historiography the period of the most intense purge, 1937–1938, is called Yezhovshchina , after Nikolai Yezhov

, the head of the Soviet secret police, NKVD

.

In the Western World

, Robert Conquest

's 1968 book The Great Terror

popularized that phrase. Conquest was in turn inspired by the period of terror (French: la Terreur) during the French Revolution

.

. Additional campaigns of repression were carried out against national minorities and social groups which were accused of acting against the Soviet state and the politics of the Communist Party

.

A number of purges were officially explained as an elimination of the possibilities of sabotage and espionage, mostly by a fictitious "Polish Military Organisation". While over 70% of the victims of the purge were ordinary citizens of Polish origin, most public attention was focused on the purge of the leadership of the Communist Party itself, as well as of government bureaucrats and leaders of the armed forces, most being Party members. The campaigns also affected many other categories of the society: intelligentsia, peasants and especially those branded as "too rich for a peasant" (kulak

s), and professionals. A series of NKVD

(the Soviet secret police

) operations affected a number of national minorities, accused of being "fifth column

" communities.

According to Nikita Khrushchev

's 1956 speech, "On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

", and more recent findings, a great number of accusations, notably those presented at the Moscow show trial

s, were based on forced confession

s, often obtained by torture

, and on loose interpretations of Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code

, which dealt with counter-revolutionary crimes. Due legal process, as defined by Soviet law in force at the time, was often largely replaced with summary proceedings by NKVD troika

s.

Hundreds of thousands of victims were accused of various political crimes (espionage

, wrecking

, sabotage

, anti-Soviet agitation, conspiracies to prepare uprisings and coups) and then executed by shooting, or sent to the Gulag

labor camp

s. Many died at the penal labor camps due to starvation, disease, exposure, and overwork. Other methods of dispatching victims were used on an experimental basis. One secret policeman, for example, gassed people to death in batches in the back of a specially adapted airtight van

.

The Great Purge was started under the NKVD chief Genrikh Yagoda

, but the height of the campaigns occurred while the NKVD was headed by Nikolai Yezhov

, from September 1936 to August 1938, hence the name "Yezhovshchina". The campaigns were carried out according to the general line, and often by direct orders, of the Party Politburo

headed by Stalin.

The term "purge

The term "purge

" in Soviet

political slang

was an abbreviation of the expression purge of the Party ranks. In 1933, for example, some 400,000 people were expelled from the Party. But from 1936 until 1953, the term changed its meaning, because being expelled from the Party came to mean almost certain arrest, imprisonment, and even execution.

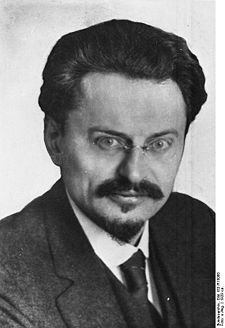

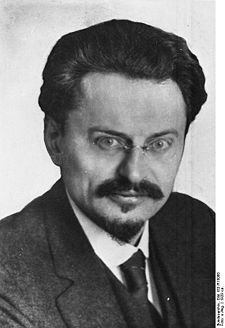

The political purge was primarily an effort by Stalin to eliminate challenge from past and potential opposition groups, including left and right wings led by Leon Trotsky

and Nikolai Bukharin

, respectively. Following the Civil War

and reconstruction of the Soviet economy in the late 1920s, the "temporary" wartime dictatorship which had passed from Lenin to Stalin seemed no longer necessary to veteran Communists. Stalin's opponents on both sides of the political spectrum chided him as undemocratic and lax on bureaucratic corruption. These tendencies may have accumulated substantial support among the working class by attacking the privileges and luxuries the state offered to its high-paid elite. The Ryutin Affair

seemed to vindicate Stalin's suspicions. He therefore enforced a ban on party factions and banned those party members who had opposed him, effectively ending democratic centralism

. In the new form of Party organization, the Politburo, and Stalin in particular, were the sole dispensers of communist ideology. This necessitated the elimination of all Marxists with different views, especially those among the prestigious "old guard" of revolutionaries. Communist heroes like Mikhail Tukhachevsky

and Béla Kun

, as well as the majority of Lenin's Politburo

, were shot for disagreements in policy. The NKVD

were equally merciless towards the supporters, friends, and family of these heretical Marxists, whether they lived in Russia or not. The most infamous case is that of Leon Trotsky, whose family was almost annihilated, before he himself was killed in Mexico by NKVD agent Ramón Mercader

, who was part of an assassination task force put together by Special Agent Pavel Sudoplatov

, under the personal orders of Joseph Stalin.

Sergey Kirov

's murder in 1934 was used by Stalin as a pretext to launch the Great Purge, in which about a million people perished. Some later historians came to believe that Stalin himself arranged the murder, or at least that there was sufficient evidence to reach such a conclusion. Kirov himself was a staunch Stalin loyalist, but Stalin may have viewed him as a potential rival because of his emerging popularity among the moderates. In the 1934 party congress, Kirov was elected to the central committee with only three negative votes, the fewest of any candidate, while Stalin received 292 negative votes. After Kirov's assassination, Stalin NKVD

charged the ever growing group of former oppositionists with Kirov's murder and a growing list of other charges including treason, terrorism, sabotage, and espionage.

Another justification was to remove any possible "fifth column

" in case of a war. This was a justification maintained to the very end by Vyacheslav Molotov

and Lazar Kaganovich

, participants in the repression as members of the Politburo, who both signed many death lists. Stalin was convinced of the imminence of war with an explicitly hostile Nazi Germany and an expansionist Japan. This was reflected in the Soviet press, which also portrayed the country as threatened from within by Fascist spies.

Repression against perceived enemies of the Bolsheviks had been a systematic method of instilling fear and facilitating social control, being continuously applied by Lenin since the October Revolution

, although there had been periods of heightened repression, such as the Red Terror

, the deportation of kulaks

who opposed collectivization, and a severe famine

. A distinctive feature of the Great Purge was that, for the first time, the ruling party itself underwent repressions on a massive scale. Nevertheless, only a minority of those affected by the purges were Communist Party members and office-holders. The purge of the Party was accompanied by the purge of the whole society. The following events are used for the demarcation of the period.

Between 1936 and 1938, three very large Moscow Trials of former senior Communist Party leaders were held, in which they were accused of conspiring with fascist and capitalist powers to assassinate Stalin and other Soviet leaders, dismember the Soviet Union and restore capitalism. These trials were highly publicized and extensively covered by the outside world, which was mesmerized by the spectacle of Lenin's closest associates confessing to most outrageous crimes and begging for death sentences.

Between 1936 and 1938, three very large Moscow Trials of former senior Communist Party leaders were held, in which they were accused of conspiring with fascist and capitalist powers to assassinate Stalin and other Soviet leaders, dismember the Soviet Union and restore capitalism. These trials were highly publicized and extensively covered by the outside world, which was mesmerized by the spectacle of Lenin's closest associates confessing to most outrageous crimes and begging for death sentences.

Some Western observers who attended the trials said that they were fair and that the guilt of the accused had been established. They based this assessment on the confessions of the accused, which were freely given in open court, without any apparent evidence that they had been extracted by torture or drugging. Others, like Fitzroy Maclean were a little more astute in their observations and conclusions.

Some Western observers who attended the trials said that they were fair and that the guilt of the accused had been established. They based this assessment on the confessions of the accused, which were freely given in open court, without any apparent evidence that they had been extracted by torture or drugging. Others, like Fitzroy Maclean were a little more astute in their observations and conclusions.

The British lawyer and Member of Parliament D. N. Pritt, for example, wrote: "Once again the more faint-hearted socialists are beset with doubts and anxieties", but "once again we can feel confident that when the smoke has rolled away from the battlefield of controversy it will be realized that the charge was true, the confessions correct and the prosecution fairly conducted".

It is now known that the confessions were given only after great psychological pressure and torture had been applied to the defendants. From the accounts of former OGPU officer Alexander Orlov

and others, the methods used to extract the confessions are known: such tortures as repeated beatings, simulated drownings, making prisoners stand or go without sleep for days on end, and threats to arrest and execute the prisoners' families. For example, Kamenev's teenage son was arrested and charged with terrorism

. After months of such interrogation, the defendants were driven to despair and exhaustion.

Zinoviev and Kamenev demanded, as a condition for "confessing", a direct guarantee from the Politburo that their lives and that of their families and followers would be spared. This offer was accepted, but when they were taken to the alleged Politburo meeting, only Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov

, and Yezhov were present. Stalin claimed that they were the "commission" authorized by the Politburo and gave assurances that death sentences would not be carried out. After the trial, Stalin not only broke his promise to spare the defendants, he had most of their relatives arrested and shot.

in the Moscow Trials, commonly known as the Dewey Commission

, was set up in the United States by supporters of Trotsky, to establish the truth about the trials. The commission was headed by the noted American philosopher and educator John Dewey

. Although the hearings were obviously conducted with a view to proving Trotsky's innocence, they brought to light evidence which established that some of the specific charges made at the trials could not be true.

For example, Georgy Pyatakov

testified that he had flown to Oslo

in December 1935 to "receive terrorist instructions" from Trotsky. The Dewey Commission established that no such flight had taken place. Another defendant, Ivan Smirnov, confessed to taking part in the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, at a time when he had already been in prison for a year.

The Dewey Commission later published its findings in a 422-page book titled Not Guilty. Its conclusions asserted the innocence of all those condemned in the Moscow Trials. In its summary, the commission wrote: "Independent of extrinsic evidence, the Commission finds:

The commission concluded: "We therefore find the Moscow Trials to be frame-ups."

provided (or more accurately was forced to provide) the pretext for greater purge to come on a massive scale with his testimony that there was a "third organization separate from the cadres which had passed through [Trotsky's] school" as well as "semi-Trotskyites, quarter-Trotskyites, one-eighth-Trotskyites, people who helped us, not knowing of the terrorist organization but sympathizing with us, people who from liberalism, from a Fronde against the Party, gave us this help."

By the "third organization", he meant the last remaining former opposition group called the Rightists

, led by Bukharin, whom he implicated by saying:

The third and final trial, in March 1938, known as The Trial of the Twenty-One, is the most famous of the Soviet show trials, because of persons involved and the scope of charges which tied together all loose threads from earlier trials. It included 21 defendants alleged to belong to the so-called "Bloc of Rightists and Trotskyites", led by Nikolai Bukharin

The third and final trial, in March 1938, known as The Trial of the Twenty-One, is the most famous of the Soviet show trials, because of persons involved and the scope of charges which tied together all loose threads from earlier trials. It included 21 defendants alleged to belong to the so-called "Bloc of Rightists and Trotskyites", led by Nikolai Bukharin

, the former chairman of the Communist International, ex-premier Alexei Rykov

, Christian Rakovsky

, Nikolai Krestinsky

and Genrikh Yagoda

, recently disgraced head of the NKVD.

The fact that Yagoda was one of the accused showed the speed at which the purges were consuming its own. Meant to be the culmination of previous trials, it was now alleged that Bukharin and others sought to assassinate Lenin and Stalin from 1918, murder Maxim Gorky

by poison, partition the U.S.S.R and hand out her territories to Germany, Japan, and Great Britain, and other preposterous charges.

Even previously sympathetic observers who had stomached the earlier trials found it harder to swallow new allegations as they became ever more absurd, and the purge now expanded to include almost every living Old Bolshevik leader except Stalin. No other crime of the Stalin years so captivated Western intellectuals as the trial and execution of Bukharin, who was a Marxist theorist of international standing. For some prominent communists such as Bertram Wolfe

, Jay Lovestone

, Arthur Koestler

, and Heinrich Brandler

, the Bukharin trial marked their final break with communism, and even turned the first three into fervent anti-Communists eventually. To them, Bukharin’s confession symbolized the

depredations of communism, which not only destroyed its sons but also conscripted them in self-destruction and individual abnegation.

The preparation for this trial, which took over a year, was delayed in its early stages due to the reluctance of some party members in denouncing their comrades. It was at this time that Stalin personally intervened to speed up the process and replaced Yagoda with Nikolai Yezhov

.

Anastas Mikoyan

and Vyacheslav Molotov

later claimed that Bukharin was never tortured, but it is now known that his interrogators were given the order, "beating permitted," and were under great pressure to extract confession out of the "star" defendant. Bukharin held out for three months, but threats to his young wife and infant son, combined with "methods of physical influence" wore him down. But when he read his confession amended and corrected personally by Stalin, he withdrew his whole confession. The examination started all over again, with a double team of interrogators.

Bukharin's confession in particular became subject of much debate among Western observers, inspiring Koestler's acclaimed novel Darkness at Noon

and philosophical essay by Maurice Merleau-Ponty

in Humanism and Terror.

His confessions were somewhat different from others in that while he pled guilty to "sum total of crimes", he denied knowledge when it came to specific crimes. Some astute observers noted that he would allow only what was in written confession and refuse to go any further.

The result was a curious mix of fulsome confessions (of being a "degenerate fascist" working for "restoration of capitalism") and subtle criticisms of the trial. After disproving several charges against him, one observer noted that he "proceeded to demolish or rather showed he could very easily demolish the whole case." He continued by saying that "the confession of the accused is not essential. The confession of the accused is a medieval principle of jurisprudence" in a trial that was solely based on confessions, he finished his last plea with the words: "the monstrousness of my crime is immeasurable especially in the new stage of struggle of the U.S.S.R. May this trial be the last severe lesson, and may the great might of the U.S.S.R become clear to all."

Romain Rolland

and others wrote to Stalin seeking clemency for Nikolai Bukharin

, but all the leading defendants were executed except Rakovsky and two others (who were killed in NKVD prisoner massacres in 1941). Despite the promise to spare his family, Bukharin's wife, Anna Larina

, was sent to a labor camp, but she survived to see her husband rehabilitated

.

was claimed to be supported by Nazi-forged documents (said to have been correspondence between Marshal Tukhachevsky

and members of the German high command). The claim is unsupported by facts, as by the time the documents were supposedly created, two people from the eight in the Tukhachevsky group were already imprisoned, and by the time the document was said to reach Stalin the purging process was already underway.

However the actual evidence introduced at trial was obtained from forced confessions. The purge of the army removed three of five marshals

(then equivalent to six-star generals), 13 of 15 army commanders (then equivalent to four- and five-star generals), eight of nine admirals (the purge fell heavily on the Navy, who were suspected of exploiting their opportunities for foreign contacts), 50 of 57 army corps

commanders, 154 out of 186 division commanders, 16 of 16 army commissar

s, and 25 of 28 army corps commissars.

At first it was thought 25-50% of Red Army officers were purged, it is now known to be 3.7-7.7%. Previously, the size of the Red Army officer corp was underestimated and it was overlooked that most of those purged were merely expelled from the Party. 30% of officers purged 1937-9 were allowed back.

s who had played prominent roles during the Russian Revolution of 1917

, or in Lenin's

Soviet government afterwards, were executed. Out of six members of the original Politburo

during the 1917 October Revolution

who lived until the Great Purge, Stalin himself was the only one who remained in the Soviet Union, alive. Four of the other five were executed. The fifth, Leon Trotsky

, went into exile in Mexico

after being expelled from the Party but was assassinated by Soviet agent Ramón Mercader

in 1940. Of the seven members elected to the Politburo between the October Revolution and Lenin's death in 1924, four were executed, one (Tomsky

) committed suicide and two (Molotov

and Kalinin

) lived.

However, the trials and executions of the former Bolshevik leaders, while being the most visible part, were only a minor part of the purges.

In the 1920s and 1930s, two thousand writers, intellectuals, and artists were imprisoned and 1,500 died in prisons and concentration camps. After sunspot development research was judged un-Marxist, twenty-seven astronomers disappeared between 1936 and 1938. The Meteorological Office was violently purged as early as 1933 for failing to predict weather harmful to the crops. But the toll was especially high among writers. Those who perished during the Great Purge include:

In the 1920s and 1930s, two thousand writers, intellectuals, and artists were imprisoned and 1,500 died in prisons and concentration camps. After sunspot development research was judged un-Marxist, twenty-seven astronomers disappeared between 1936 and 1938. The Meteorological Office was violently purged as early as 1933 for failing to predict weather harmful to the crops. But the toll was especially high among writers. Those who perished during the Great Purge include:

s" and other "anti-Soviet elements" (such as former officials of the Tsarist regime

, former members of political parties other than the communist party, etc.).

They were to be executed or sent to GULAG

prison camps extrajudicially, under the decisions of NKVD troika

s.

was carried out during 1937–1940, justified by the fear of the fifth column

in the expectation of war with "the most probable adversary", i.e., Germany

, as well as according to the notion of the "hostile capitalist surrounding", which wants to destabilize the country. The Polish operation of the NKVD

was the largest and the first of this kind, setting an example of dealing with other targeted minorities. Many such operations were conducted on a quota system. NKVD local officials were mandated to arrest and execute a specific number of "counter-revolutionaries," produced by upper officials based on various statistics. The Polish operation also claimed the largest number of victims: 143,810 arrests and 111,091 executions, and at least eighty-five thousand of these were ethnic Poles.

in order to find work. At the height of the Terror, American immigrants besieged the US embassy, begging for passport

s so they could leave Russia. They were turned away by embassy officials, only to be arrested on the pavement outside by lurking NKVD

agents. Many were subsequently shot dead at Butovo Field

near Scherbinka, south of Moscow

. In addition, 141 American Communists of Finnish origin were executed and buried at Sandarmokh

. 127 Finnish Canadians were also shot and buried there.

During the late 1930s, Stalin dispatched NKVD

During the late 1930s, Stalin dispatched NKVD

operatives to the Mongolian People's Republic, established a Mongolian version of the NKVD troika

, and proceeded to execute tens of thousands of people accused of having ties to "pro-Japanese spy rings." Buddhist lama

s made up the majority of victims, with 18,000 being killed in the terror. Other victims were nobility and political and academic figures, along with some ordinary workers and herders. Mass graves containing hundreds of executed Buddhist monks and civilians have been discovered as recently as 2003.

of Xinjiang

province in China launched his own purge in 1937 to coincide with Stalin's Great Purge, the Xinjiang War (1937)

broke out amid the purge. Sheng received assistance from the NKVD

, Sheng and the Soviets alleged a massive Trotskyist conspiracy and a "Fascist Trotskyite plot" to destroy the Soviet Union

. The Soviet Consul General Garegin Apresoff, General Ma Hushan

, Ma Shaowu

, Mahmud Sijan, the official leader of the Xinjiang province Huang Han-chang and Hoja-Niyaz

were among the 435 alleged conspirators in the plot. Xinjiang became under virtual Soviet control. Stalin opposed the Chinese Communist Party.

October 1936–February 1937: Reforming the security organizations, adopting official plans on purging the elites.

March 1937–June 1937: Purging the Elites; Adopting plans for the mass repressions against the "social base" of the potential aggressors, starting of purging the "elites" from opposition.

July 1937–October 1938: Mass repressions against "kulak

s", "dangerous" ethnic minorities, family members of oppositionists, military officers, Saboteurs

in agriculture and industry.

November 1938–1939: Stopping of mass operations, abolishing of many organs of extrajudicial executions, repressions against some organizers of mass repressions.

By the summer of 1938, Stalin and his circle realized that the purges had gone too far; Yezhov was relieved from his post as head of the NKVD

By the summer of 1938, Stalin and his circle realized that the purges had gone too far; Yezhov was relieved from his post as head of the NKVD

and was eventually purged himself. Lavrenty Beria, a fellow Georgian and Stalin confidant, succeeded him as head of the NKVD. On November 17, 1938 a joint decree of Sovnarkom USSR and Central Committee

of VKP(b) (Decree about Arrests, Prosecutor Supervision and Course of Investigation

) and the subsequent order of NKVD undersigned by Beria cancelled most of the NKVD orders of systematic repression

and suspended implementation of death sentences. The decree signaled the end of massive Soviet purges.

Nevertheless, the practice of mass arrest

and exile was continued until Stalin's death in 1953. Political executions also continued, but, with the exception of Katyn

and other NKVD massacres during WWII, on a vastly smaller scale. One notorious example is the "Night of the Murdered Poets

", in which at least thirteen prominent Yiddish writers were executed on August 12, 1952. Historians such as Michael Parrish have argued that while the Great Terror ended in 1938, a lesser terror continued in the 1940s.

In some cases, military officers arrested under Yezhov were later executed under Beria. Some examples include Marshal of the Soviet Union A.I. Egorov, arrested in April 1938 and shot (or died from torture) in February 1939 (his wife, G.A. Egorova, was shot in August 1938); Army Commander I.F. Fed'ko, arrested July 1938 and shot February 1939; Flagman K.I. Dushenov, arrested May 1938 and shot February 1940; Komkor G.I. Bondar, arrested August 1938 and shot March 1939. All the aforementioned have been posthumously rehabilitated.

When the relatives of those who had been executed in 1937-38 inquired about their fate, they were told by NKVD that their arrested relatives had been sentenced to "ten years without the right of correspondence" (десять лет без права переписки). When these ten-year periods elapsed in 1947-48 but the arrested did not appear, the relatives asked MGB

about their fate again and this time were told that the arrested died in imprisonment.

took the position that evidence of the camps should be ignored, in order that the French proletariat not be discouraged. A series of legal actions ensued at which definitive evidence was presented which established the validity of the former labor camp inmates' testimony.

According to Robert Conquest

in his 1968 book The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties, with respect to the trials of former leaders, some Western observers were unable to see through the fraudulent nature of the charges and evidence, notably Walter Duranty

of The New York Times

, a Russian speaker; the American Ambassador, Joseph E. Davies

, who reported, "proof...beyond reasonable doubt to justify the verdict of treason" and Beatrice

and Sidney Webb, authors of Soviet Communism: A New Civilization. While "Communist Parties everywhere simply transmitted the Soviet line", some of the most critical reporting also came from the left, notably The Manchester Guardian

.

Evidence and the results of research began to appear after Stalin's death which revealed the full enormity of the Purges. The first of these sources were the revelations of Nikita Khrushchev

, which particularly affected the American editors of the Communist Party USA

newspaper, the Daily Worker

, who, following the lead of The New York Times, published the Secret Speech

in full.

Efforts to minimize the extent of the Great Purge continue among revisionist scholars in the

West. Jerry F. Hough

claims, regarding the numbers executed in the Great Purge, "a figure in the low hundreds of thousands seems much more probable than one in the high hundreds" and that a lower figure of only "tens of thousands" was "even probable". Sheila Fitzpatrick

also placed the numbers executed in the "low hundreds of thousands." Robert W. Thurston allows for 681,692 executions, but claims that Stalin "was not guilty of mass first degree murder from 1934 to 1941" and that he was a "fear ridden man" who just "overreacted to events."

following Stalin's death. In his secret speech

to the 20th CPSU

congress in February 1956 (which was made public a month later), Khrushchev referred to the purges as an "abuse of power" by Stalin which resulted in enormous harm to the country. In the same speech, he recognized that many of the victims were innocent and were convicted on the basis of false confessions extracted by torture. To take that position was politically useful to Khrushchev, as he was at that time engaged in a power struggle with rivals who had been associated with the Purge, the so-called Anti-Party Group

. The new line on the Great Purges undermined their power, and helped propel him to the Chairmanship of the Council of Ministers.

Starting from 1954, some of the convictions were overturned. Mikhail Tukhachevsky

and other generals convicted in the Trial of Red Army Generals were declared innocent ("rehabilitated

") in 1957. The former Politburo members Yan Rudzutak

and Stanislav Kosior

and many lower-level victims were also declared innocent in the 1950s. Nikolai Bukharin

and others convicted in the Moscow Trials

were not rehabilitated until as late as 1988.

The book Rehabilitation: The Political Processes of the 1930s-50s (Реабилитация. Политические процессы 30-50-х годов) (1991) contains a large amount of newly presented original archive material: transcripts of interrogations, letters of convicts, and photos. The material demonstrates in detail how numerous show trials were fabricated.

Some experts believe the evidence released from the Soviet archives is understated, incomplete, or unreliable. For example, Robert Conquest

claims that the probable figure for executions during the years of the Great Purge is not 681,692, but some two and a half times as high. He believes that the KGB was covering its tracks by falsifying the dates and causes of death of rehabilitated victims.

Historian Michael Ellman

claims the best estimate of deaths brought about by Soviet repression during these two years is the range 950,000 to 1.2 million, which includes deaths in detention and those who died shortly after being released from the Gulag as a result of their treatment in it. He also states that this is the estimate which should be used by historians and teachers of Russian history.

In addition to authorizing torture, Stalin also signed 357 proscription

lists in 1937 and 1938 which condemned to execution some 40,000 people, and about 90% of these are confirmed to have been shot. While reviewing one such list, Stalin reportedly muttered to no one in particular: "Who's going to remember all this riff-raff in ten or twenty years time? No one. Who remembers the names now of the boyars Ivan the Terrible got rid of? No one."

after Stalin's death. The first was headed by Molotov

and included Voroshilov

, Kaganovich

, Suslov

, Furtseva, Shvernik

, Aristov

, Pospelov and Rudenko

. They were given the task to investigate the materials concerning Bukharin, Rykov, Zinoviev, Tukhachevsky and others. The commission worked in 1956–1957. While stating that the accusations against Tukhachevsky et al. should be abandoned, it failed to fully rehabilitate the victims of the three Moscow trials, although the final report does contain an admission that the accusations have not been proven during the trials and "evidence" had been produced by lies, blackmail, and "use of physical influence". Bukharin, Rykov, Zinoviev, and others were still seen as political opponents, and though the charges against them were obviously false, they could not have been rehabilitated because "for many years they headed the anti-Soviet struggle against the building of socialism in USSR".

The second commission largely worked from 1961 to 1963 and was headed by Shvernik ("Shvernik Commission

"). It included Shelepin

, Serdyuk, Mironov, Rudenko, and Semichastny. The hard work resulted in two massive reports, which detailed the mechanism of falsification of the show-trials against Bukharin, Zinoviev, Tukhachevsky, and many others. The commission based its findings in large part on eyewitness testimonies of former NKVD workers and victims of repressions, and on many documents. The commission recommended to rehabilitate every accused with exception of Radek and Yagoda, because Radek's materials required some further checking, and Yagoda was a criminal and one of the falsifiers of the trials (though most of the charges against him had to be dropped too, he was not a "spy", etc.). The commission stated:

However, soon Khrushchev was deposed and the "Thaw"

ended, so most victims of the three show-trials were not rehabilitated until Gorbachev

's time.

near Minsk

and Bykivnia

near Kiev

, are believed to contain up to 200,000 corpses.

In 2007, one such site, the Butovo firing range

near Moscow

, was turned into a shrine to the victims of Stalinism. From August 1937 through October 1938, more than 20,000 people were shot and buried there.

Political repression

Political repression is the persecution of an individual or group for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing their ability to take political life of society....

and persecution

Persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another group. The most common forms are religious persecution, ethnic persecution, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these terms. The inflicting of suffering, harassment, isolation,...

in the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

orchestrated by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

from 1936 to 1938. It involved a large-scale purge of the Communist Party and government officials

Purge of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Purges with a "small-p" purge was one of the key rituals during which a periodic review of party members was conducted to get rid of the "undesirables"....

, repression of peasants, Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

leadership, and the persecution of unaffiliated persons, characterized by widespread police surveillance, widespread suspicion of "saboteurs", imprisonment, and arbitrary executions.

In Russian historiography the period of the most intense purge, 1937–1938, is called Yezhovshchina , after Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov or Ezhov was a senior figure in the NKVD under Joseph Stalin during the period of the Great Purge. His reign is sometimes known as the "Yezhovshchina" , "the Yezhov era", a term that began to be used during the de-Stalinization campaign of the 1950s...

, the head of the Soviet secret police, NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

.

In the Western World

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

, Robert Conquest

Robert Conquest

George Robert Ackworth Conquest CMG is a British historian who became a well-known writer and researcher on the Soviet Union with the publication in 1968 of The Great Terror, an account of Stalin's purges of the 1930s...

's 1968 book The Great Terror

The Great Terror

The Great Terror is a book by British historian Robert Conquest, published in 1968. It gave rise to an alternate title of the period in Soviet history known as the Great Purge. The complete title of the book is The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties...

popularized that phrase. Conquest was in turn inspired by the period of terror (French: la Terreur) during the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

.

Introduction

The term "repression" was officially used to denote the prosecution of people considered as anti-revolutionaries and enemies of the people. The purge was motivated by the desire on the part of the leadership to remove dissenters from the Party and what is often considered to have been a desire to consolidate the authority of Joseph StalinJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

. Additional campaigns of repression were carried out against national minorities and social groups which were accused of acting against the Soviet state and the politics of the Communist Party

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

.

A number of purges were officially explained as an elimination of the possibilities of sabotage and espionage, mostly by a fictitious "Polish Military Organisation". While over 70% of the victims of the purge were ordinary citizens of Polish origin, most public attention was focused on the purge of the leadership of the Communist Party itself, as well as of government bureaucrats and leaders of the armed forces, most being Party members. The campaigns also affected many other categories of the society: intelligentsia, peasants and especially those branded as "too rich for a peasant" (kulak

Kulak

Kulaks were a category of relatively affluent peasants in the later Russian Empire, Soviet Russia, and early Soviet Union...

s), and professionals. A series of NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

(the Soviet secret police

Secret police

Secret police are a police agency which operates in secrecy and beyond the law to protect the political power of an individual dictator or an authoritarian political regime....

) operations affected a number of national minorities, accused of being "fifth column

Fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who clandestinely undermine a larger group such as a nation from within.-Origin:The term originated with a 1936 radio address by Emilio Mola, a Nationalist General during the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War...

" communities.

According to Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

's 1956 speech, "On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

On the Personality Cult and its Consequences was a report, critical of Joseph Stalin, made to the Twentieth Party Congress on February 25, 1956 by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. It is more commonly known as the Secret Speech or the Khrushchev Report...

", and more recent findings, a great number of accusations, notably those presented at the Moscow show trial

Moscow Trials

The Moscow Trials were a series of show trials conducted in the Soviet Union and orchestrated by Joseph Stalin during the Great Purge of the 1930s. The victims included most of the surviving Old Bolsheviks, as well as the leadership of the Soviet secret police...

s, were based on forced confession

Forced confession

A forced confession is a confession obtained by a suspect or a prisoner under means of torture, enhanced interrogation technique or duress.Depending on the level of coercion used, a forced confession may or may not be valid in revealing the truth...

s, often obtained by torture

Torture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

, and on loose interpretations of Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code

Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code)

Article 58 of the Russian SFSR Penal Code was put in force on 25 February 1927 to arrest those suspected of counter-revolutionary activities. It was revised several times...

, which dealt with counter-revolutionary crimes. Due legal process, as defined by Soviet law in force at the time, was often largely replaced with summary proceedings by NKVD troika

NKVD troika

NKVD troika or Troika, in Soviet Union history, were commissions of three persons who convicted people without trial. These commissions were employed as an instrument of extrajudicial punishment introduced to circumvent the legal system with a means for quick execution or imprisonment...

s.

Hundreds of thousands of victims were accused of various political crimes (espionage

Espionage

Espionage or spying involves an individual obtaining information that is considered secret or confidential without the permission of the holder of the information. Espionage is inherently clandestine, lest the legitimate holder of the information change plans or take other countermeasures once it...

, wrecking

Wrecking (Soviet crime)

Wrecking , was a crime specified in the criminal code of the Soviet Union in the Stalin era. It is often translated as "sabotage"; however "wrecking" and "diversionist acts" and "counter-revolutionary sabotage" were distinct sub-articles of Article 58 , and the meaning of "wrecking" is closer to...

, sabotage

Sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening another entity through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. In a workplace setting, sabotage is the conscious withdrawal of efficiency generally directed at causing some change in workplace conditions. One who engages in sabotage is...

, anti-Soviet agitation, conspiracies to prepare uprisings and coups) and then executed by shooting, or sent to the Gulag

Gulag

The Gulag was the government agency that administered the main Soviet forced labor camp systems. While the camps housed a wide range of convicts, from petty criminals to political prisoners, large numbers were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas and other instruments of...

labor camp

Labor camp

A labor camp is a simplified detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons...

s. Many died at the penal labor camps due to starvation, disease, exposure, and overwork. Other methods of dispatching victims were used on an experimental basis. One secret policeman, for example, gassed people to death in batches in the back of a specially adapted airtight van

Gas van

The gas van or gas wagon was an extermination method devised by Nazi Germany to kill victims of the regime. It was also rumored that analog of such device was used by the Soviet Union on an experimental basis during the Great Purge-Nazi Germany:...

.

The Great Purge was started under the NKVD chief Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda , born Enokh Gershevich Ieguda , was a Soviet state security official who served as director of the NKVD, the Soviet Union's Stalin-era security and intelligence agency, from 1934 to 1936...

, but the height of the campaigns occurred while the NKVD was headed by Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov or Ezhov was a senior figure in the NKVD under Joseph Stalin during the period of the Great Purge. His reign is sometimes known as the "Yezhovshchina" , "the Yezhov era", a term that began to be used during the de-Stalinization campaign of the 1950s...

, from September 1936 to August 1938, hence the name "Yezhovshchina". The campaigns were carried out according to the general line, and often by direct orders, of the Party Politburo

Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Politburo , known as the Presidium from 1952 to 1966, functioned as the central policymaking and governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.-Duties and responsibilities:The...

headed by Stalin.

Background

Purge

In history, religion, and political science, a purge is the removal of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, from another organization, or from society as a whole. Purges can be peaceful or violent; many will end with the imprisonment or exile of those purged,...

" in Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

political slang

Slang

Slang is the use of informal words and expressions that are not considered standard in the speaker's language or dialect but are considered more acceptable when used socially. Slang is often to be found in areas of the lexicon that refer to things considered taboo...

was an abbreviation of the expression purge of the Party ranks. In 1933, for example, some 400,000 people were expelled from the Party. But from 1936 until 1953, the term changed its meaning, because being expelled from the Party came to mean almost certain arrest, imprisonment, and even execution.

The political purge was primarily an effort by Stalin to eliminate challenge from past and potential opposition groups, including left and right wings led by Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

and Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin , was a Russian Marxist, Bolshevik revolutionary, and Soviet politician. He was a member of the Politburo and Central Committee , chairman of the Communist International , and the editor in chief of Pravda , the journal Bolshevik , Izvestia , and the Great Soviet...

, respectively. Following the Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

and reconstruction of the Soviet economy in the late 1920s, the "temporary" wartime dictatorship which had passed from Lenin to Stalin seemed no longer necessary to veteran Communists. Stalin's opponents on both sides of the political spectrum chided him as undemocratic and lax on bureaucratic corruption. These tendencies may have accumulated substantial support among the working class by attacking the privileges and luxuries the state offered to its high-paid elite. The Ryutin Affair

Ryutin Affair

The Ryutin Affair was one of the last attempts to oppose the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin within the Soviet Communist Party.Martemyan Ryutin was an Old Bolshevik and a secretary of the Moscow City Communist Party Committee in the 1920s...

seemed to vindicate Stalin's suspicions. He therefore enforced a ban on party factions and banned those party members who had opposed him, effectively ending democratic centralism

Democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is the name given to the principles of internal organization used by Leninist political parties, and the term is sometimes used as a synonym for any Leninist policy inside a political party...

. In the new form of Party organization, the Politburo, and Stalin in particular, were the sole dispensers of communist ideology. This necessitated the elimination of all Marxists with different views, especially those among the prestigious "old guard" of revolutionaries. Communist heroes like Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, commander in chief of the Red Army , and one of the most prominent victims of Joseph Stalin's Great Purge.-Early life:...

and Béla Kun

Béla Kun

Béla Kun , born Béla Kohn, was a Hungarian Communist politician and a Bolshevik Revolutionary who led the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919.- Early life :...

, as well as the majority of Lenin's Politburo

Politburo

Politburo , literally "Political Bureau [of the Central Committee]," is the executive committee for a number of communist political parties.-Marxist-Leninist states:...

, were shot for disagreements in policy. The NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

were equally merciless towards the supporters, friends, and family of these heretical Marxists, whether they lived in Russia or not. The most infamous case is that of Leon Trotsky, whose family was almost annihilated, before he himself was killed in Mexico by NKVD agent Ramón Mercader

Ramón Mercader

Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río Hernández was a Spanish communist who became famous as the murderer of Russian Communist ideologist Leon Trotsky in 1940, in Mexico...

, who was part of an assassination task force put together by Special Agent Pavel Sudoplatov

Pavel Sudoplatov

Lieutenant General Pavel Anatolyevich Sudoplatov was a member of the intelligence services of the Soviet Union who rose to the rank of lieutenant general...

, under the personal orders of Joseph Stalin.

Sergey Kirov

Sergey Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov , born Sergei Mironovich Kostrikov, was a prominent early Bolshevik leader in the Soviet Union. Kirov rose through the Communist Party ranks to become head of the Party organization in Leningrad...

's murder in 1934 was used by Stalin as a pretext to launch the Great Purge, in which about a million people perished. Some later historians came to believe that Stalin himself arranged the murder, or at least that there was sufficient evidence to reach such a conclusion. Kirov himself was a staunch Stalin loyalist, but Stalin may have viewed him as a potential rival because of his emerging popularity among the moderates. In the 1934 party congress, Kirov was elected to the central committee with only three negative votes, the fewest of any candidate, while Stalin received 292 negative votes. After Kirov's assassination, Stalin NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

charged the ever growing group of former oppositionists with Kirov's murder and a growing list of other charges including treason, terrorism, sabotage, and espionage.

Another justification was to remove any possible "fifth column

Fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who clandestinely undermine a larger group such as a nation from within.-Origin:The term originated with a 1936 radio address by Emilio Mola, a Nationalist General during the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War...

" in case of a war. This was a justification maintained to the very end by Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

and Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich was a Soviet politician and administrator and one of the main associates of Joseph Stalin.-Early life:Kaganovich was born in 1893 to Jewish parents in the village of Kabany, Radomyshl uyezd, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire...

, participants in the repression as members of the Politburo, who both signed many death lists. Stalin was convinced of the imminence of war with an explicitly hostile Nazi Germany and an expansionist Japan. This was reflected in the Soviet press, which also portrayed the country as threatened from within by Fascist spies.

Repression against perceived enemies of the Bolsheviks had been a systematic method of instilling fear and facilitating social control, being continuously applied by Lenin since the October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

, although there had been periods of heightened repression, such as the Red Terror

Red Terror

The Red Terror in Soviet Russia was the campaign of mass arrests and executions conducted by the Bolshevik government. In Soviet historiography, the Red Terror is described as having been officially announced on September 2, 1918 by Yakov Sverdlov and ended about October 1918...

, the deportation of kulaks

Dekulakization

Dekulakization was the Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, and executions of millions of the better-off peasants and their families in 1929-1932. The richer peasants were labeled kulaks and considered class enemies...

who opposed collectivization, and a severe famine

Soviet famine of 1932-1933

The Soviet famine of 1932–1933 killed many millions in the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union. These areas included Ukraine, Northern Caucasus, Volga Region and Kazakhstan, the South Urals, and West Siberia...

. A distinctive feature of the Great Purge was that, for the first time, the ruling party itself underwent repressions on a massive scale. Nevertheless, only a minority of those affected by the purges were Communist Party members and office-holders. The purge of the Party was accompanied by the purge of the whole society. The following events are used for the demarcation of the period.

- The First Moscow Trial, 1936.

- Introduction of NKVD troikaNKVD troikaNKVD troika or Troika, in Soviet Union history, were commissions of three persons who convicted people without trial. These commissions were employed as an instrument of extrajudicial punishment introduced to circumvent the legal system with a means for quick execution or imprisonment...

s for express implementation of "revolutionary justice" in 1937. - Introduction of Article 58-14Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code)Article 58 of the Russian SFSR Penal Code was put in force on 25 February 1927 to arrest those suspected of counter-revolutionary activities. It was revised several times...

about "counter-revolutionary sabotage" in 1937.

First and Second Moscow Trials

- The first trial was of 16 members of the so-called "Trotskyite-Kamenevite-Zinovievite-Leftist-Counter-Revolutionary Bloc", held in August 1936, at which the chief defendants were Grigory ZinovievGrigory ZinovievGrigory Yevseevich Zinoviev , born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky Apfelbaum , was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet Communist politician...

and Lev KamenevLev KamenevLev Borisovich Kamenev , born Rozenfeld , was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a prominent Soviet politician. He was briefly head of state of the new republic in 1917, and from 1923-24 the acting Premier in the last year of Lenin's life....

, two of the most prominent former party leaders. Among other accusations, they were incriminated with the assassination of Sergey KirovSergey KirovSergei Mironovich Kirov , born Sergei Mironovich Kostrikov, was a prominent early Bolshevik leader in the Soviet Union. Kirov rose through the Communist Party ranks to become head of the Party organization in Leningrad...

and plotting to kill Stalin. After confessing to the charges, all were sentenced to death and executed.

- The second trial in January 1937 involved 17 lesser figures known as the "anti-Soviet Trotskyite-centre" which included Karl RadekKarl RadekKarl Bernhardovic Radek was a socialist active in the Polish and German movements before World War I and an international Communist leader after the Russian Revolution....

, Yuri Piatakov and Grigory Sokolnikov, and were accused of plotting with Trotsky, who was said to be conspiring with Nazi Germany. Thirteen of the defendants were eventually shot. The rest received sentences in labor camps where they soon died. - There was also a secret trial before a military tribunal of a group of Red ArmyRed ArmyThe Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

commanders, including Mikhail TukhachevskyMikhail TukhachevskyMikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, commander in chief of the Red Army , and one of the most prominent victims of Joseph Stalin's Great Purge.-Early life:...

, in June 1937.

The British lawyer and Member of Parliament D. N. Pritt, for example, wrote: "Once again the more faint-hearted socialists are beset with doubts and anxieties", but "once again we can feel confident that when the smoke has rolled away from the battlefield of controversy it will be realized that the charge was true, the confessions correct and the prosecution fairly conducted".

It is now known that the confessions were given only after great psychological pressure and torture had been applied to the defendants. From the accounts of former OGPU officer Alexander Orlov

Alexander Orlov

Alexander Mikhailovich Orlov , born Lev Feldbin, 21 August 1895–25 March 1973), was a General in the Soviet secret police and NKVD Rezident in the Second Spanish Republic. In 1938, Orlov refused to return to the Soviet Union because he realized that he would be executed, and fled with his...

and others, the methods used to extract the confessions are known: such tortures as repeated beatings, simulated drownings, making prisoners stand or go without sleep for days on end, and threats to arrest and execute the prisoners' families. For example, Kamenev's teenage son was arrested and charged with terrorism

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

. After months of such interrogation, the defendants were driven to despair and exhaustion.

Zinoviev and Kamenev demanded, as a condition for "confessing", a direct guarantee from the Politburo that their lives and that of their families and followers would be spared. This offer was accepted, but when they were taken to the alleged Politburo meeting, only Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov , popularly known as Klim Voroshilov was a Soviet military officer, politician, and statesman...

, and Yezhov were present. Stalin claimed that they were the "commission" authorized by the Politburo and gave assurances that death sentences would not be carried out. After the trial, Stalin not only broke his promise to spare the defendants, he had most of their relatives arrested and shot.

Dewey Commission

In May 1937, the Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made against Leon TrotskyLeon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

in the Moscow Trials, commonly known as the Dewey Commission

Dewey Commission

The Dewey Commission was initiated in March 1937 by the "American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky." It was named after its Chairman, John Dewey...

, was set up in the United States by supporters of Trotsky, to establish the truth about the trials. The commission was headed by the noted American philosopher and educator John Dewey

John Dewey

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. Dewey was an important early developer of the philosophy of pragmatism and one of the founders of functional psychology...

. Although the hearings were obviously conducted with a view to proving Trotsky's innocence, they brought to light evidence which established that some of the specific charges made at the trials could not be true.

For example, Georgy Pyatakov

Georgy Pyatakov

Georgy Leonidovich Pyatakov was a Bolshevik revolutionary leader during the Russian Revolution, and member of the Left Opposition.Pyatakov was born August 6, 1890 in the settlement of the Mariinsky sugar factory which was owned by his father, an ethnic Russian, Leonid Timofeyevich Pyatakov.He...

testified that he had flown to Oslo

Oslo

Oslo is a municipality, as well as the capital and most populous city in Norway. As a municipality , it was established on 1 January 1838. Founded around 1048 by King Harald III of Norway, the city was largely destroyed by fire in 1624. The city was moved under the reign of Denmark–Norway's King...

in December 1935 to "receive terrorist instructions" from Trotsky. The Dewey Commission established that no such flight had taken place. Another defendant, Ivan Smirnov, confessed to taking part in the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, at a time when he had already been in prison for a year.

The Dewey Commission later published its findings in a 422-page book titled Not Guilty. Its conclusions asserted the innocence of all those condemned in the Moscow Trials. In its summary, the commission wrote: "Independent of extrinsic evidence, the Commission finds:

- That the conduct of the Moscow Trials was such as to convince any unprejudiced person that no attempt was made to ascertain the truth.

- That while confessions are necessarily entitled to the most serious consideration, the confessions themselves contain such inherent improbabilities as to convince the Commission that they do not represent the truth, irrespective of any means used to obtain them.

- That Trotsky never instructed any of the accused or witnesses in the Moscow trials to enter into agreements with foreign powers against the Soviet Union [and] that Trotsky never recommended, plotted, or attempted the restoration of capitalism in the USSR.

The commission concluded: "We therefore find the Moscow Trials to be frame-ups."

Implication of the Rightists

In the second trial, Karl RadekKarl Radek

Karl Bernhardovic Radek was a socialist active in the Polish and German movements before World War I and an international Communist leader after the Russian Revolution....

provided (or more accurately was forced to provide) the pretext for greater purge to come on a massive scale with his testimony that there was a "third organization separate from the cadres which had passed through [Trotsky's] school" as well as "semi-Trotskyites, quarter-Trotskyites, one-eighth-Trotskyites, people who helped us, not knowing of the terrorist organization but sympathizing with us, people who from liberalism, from a Fronde against the Party, gave us this help."

By the "third organization", he meant the last remaining former opposition group called the Rightists

Right Opposition

The Right Opposition was the name given to the tendency made up of Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Mikhail Tomsky and their supporters within the Soviet Union in the late 1920s...

, led by Bukharin, whom he implicated by saying:

Third Moscow Trial

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin , was a Russian Marxist, Bolshevik revolutionary, and Soviet politician. He was a member of the Politburo and Central Committee , chairman of the Communist International , and the editor in chief of Pravda , the journal Bolshevik , Izvestia , and the Great Soviet...

, the former chairman of the Communist International, ex-premier Alexei Rykov

Alexei Rykov

Aleksei Ivanovich Rykov was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician most prominent as Premier of Russia and the Soviet Union from 1924–29 and 1924–30 respectively....

, Christian Rakovsky

Christian Rakovsky

Christian Rakovsky was a Bulgarian socialist revolutionary, a Bolshevik politician and Soviet diplomat; he was also noted as a journalist, physician, and essayist...

, Nikolai Krestinsky

Nikolai Krestinsky

Nikolay Nikolayevich Krestinsky was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet politician.-Origins:Krestinsky was born in the town of Mogilev, in what is now Mahilyow Voblast of Belarus. According to Russian archivist A. B. Roginsky, Krestinsky was of ethnic Russian origin...

and Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda , born Enokh Gershevich Ieguda , was a Soviet state security official who served as director of the NKVD, the Soviet Union's Stalin-era security and intelligence agency, from 1934 to 1936...

, recently disgraced head of the NKVD.

The fact that Yagoda was one of the accused showed the speed at which the purges were consuming its own. Meant to be the culmination of previous trials, it was now alleged that Bukharin and others sought to assassinate Lenin and Stalin from 1918, murder Maxim Gorky

Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov , primarily known as Maxim Gorky , was a Russian and Soviet author, a founder of the Socialist Realism literary method and a political activist.-Early years:...

by poison, partition the U.S.S.R and hand out her territories to Germany, Japan, and Great Britain, and other preposterous charges.

Even previously sympathetic observers who had stomached the earlier trials found it harder to swallow new allegations as they became ever more absurd, and the purge now expanded to include almost every living Old Bolshevik leader except Stalin. No other crime of the Stalin years so captivated Western intellectuals as the trial and execution of Bukharin, who was a Marxist theorist of international standing. For some prominent communists such as Bertram Wolfe

Bertram Wolfe

Bertram David "Bert" Wolfe was an American scholar and former communist best known for biographical studies of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky, and Diego Rivera.-Early life:...

, Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Central Intelligence Agency helper, and foreign policy advisor to the leadership of the AFL-CIO and various unions...

, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler CBE was a Hungarian author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria...

, and Heinrich Brandler

Heinrich Brandler

Heinrich Brandler was a German communist trade unionist, politician, revolutionary activist, and writer. Brandler is best remember as the head of the Communist Party of Germany during the party's ill-fated "March Action" of 1921 and aborted uprising of 1923, for which he was held responsible by...

, the Bukharin trial marked their final break with communism, and even turned the first three into fervent anti-Communists eventually. To them, Bukharin’s confession symbolized the

depredations of communism, which not only destroyed its sons but also conscripted them in self-destruction and individual abnegation.

The preparation for this trial, which took over a year, was delayed in its early stages due to the reluctance of some party members in denouncing their comrades. It was at this time that Stalin personally intervened to speed up the process and replaced Yagoda with Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov or Ezhov was a senior figure in the NKVD under Joseph Stalin during the period of the Great Purge. His reign is sometimes known as the "Yezhovshchina" , "the Yezhov era", a term that began to be used during the de-Stalinization campaign of the 1950s...

.

Bukharin's confession

On the first day of trial, Krestinsky caused a sensation when he repudiated his written confession and pled not guilty to all the charges. However, he changed his plea the next day after "special measures", which dislocated his left shoulder among other things.Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan was an Armenian Old Bolshevik and Soviet statesman during the rules of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev, and Leonid Brezhnev....

and Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

later claimed that Bukharin was never tortured, but it is now known that his interrogators were given the order, "beating permitted," and were under great pressure to extract confession out of the "star" defendant. Bukharin held out for three months, but threats to his young wife and infant son, combined with "methods of physical influence" wore him down. But when he read his confession amended and corrected personally by Stalin, he withdrew his whole confession. The examination started all over again, with a double team of interrogators.

Bukharin's confession in particular became subject of much debate among Western observers, inspiring Koestler's acclaimed novel Darkness at Noon

Darkness at Noon

Darkness at Noon is a novel by the Hungarian-born British novelist Arthur Koestler, first published in 1940...

and philosophical essay by Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Merleau-Ponty was a French phenomenological philosopher, strongly influenced by Karl Marx, Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger in addition to being closely associated with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir...

in Humanism and Terror.

His confessions were somewhat different from others in that while he pled guilty to "sum total of crimes", he denied knowledge when it came to specific crimes. Some astute observers noted that he would allow only what was in written confession and refuse to go any further.

The result was a curious mix of fulsome confessions (of being a "degenerate fascist" working for "restoration of capitalism") and subtle criticisms of the trial. After disproving several charges against him, one observer noted that he "proceeded to demolish or rather showed he could very easily demolish the whole case." He continued by saying that "the confession of the accused is not essential. The confession of the accused is a medieval principle of jurisprudence" in a trial that was solely based on confessions, he finished his last plea with the words: "the monstrousness of my crime is immeasurable especially in the new stage of struggle of the U.S.S.R. May this trial be the last severe lesson, and may the great might of the U.S.S.R become clear to all."

Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915.-Biography:...

and others wrote to Stalin seeking clemency for Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin , was a Russian Marxist, Bolshevik revolutionary, and Soviet politician. He was a member of the Politburo and Central Committee , chairman of the Communist International , and the editor in chief of Pravda , the journal Bolshevik , Izvestia , and the Great Soviet...

, but all the leading defendants were executed except Rakovsky and two others (who were killed in NKVD prisoner massacres in 1941). Despite the promise to spare his family, Bukharin's wife, Anna Larina

Anna Larina

Anna Larina was the wife of the Bolshevik leader Nikolai Bukharin, and spent many years trying to rehabilitate her husband after he was executed in 1938. She was the author of a memoir entitled This I Cannot Forget....

, was sent to a labor camp, but she survived to see her husband rehabilitated

Rehabilitation (Soviet)

Rehabilitation in the context of the former Soviet Union, and the Post-Soviet states, was the restoration of a person who was criminally prosecuted without due basis, to the state of acquittal...

.

Purge of the army

The purge of the Red ArmyRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

was claimed to be supported by Nazi-forged documents (said to have been correspondence between Marshal Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, commander in chief of the Red Army , and one of the most prominent victims of Joseph Stalin's Great Purge.-Early life:...

and members of the German high command). The claim is unsupported by facts, as by the time the documents were supposedly created, two people from the eight in the Tukhachevsky group were already imprisoned, and by the time the document was said to reach Stalin the purging process was already underway.

However the actual evidence introduced at trial was obtained from forced confessions. The purge of the army removed three of five marshals

Marshal of the Soviet Union

Marshal of the Soviet Union was the de facto highest military rank of the Soviet Union. ....

(then equivalent to six-star generals), 13 of 15 army commanders (then equivalent to four- and five-star generals), eight of nine admirals (the purge fell heavily on the Navy, who were suspected of exploiting their opportunities for foreign contacts), 50 of 57 army corps

Corps

A corps is either a large formation, or an administrative grouping of troops within an armed force with a common function such as Artillery or Signals representing an arm of service...

commanders, 154 out of 186 division commanders, 16 of 16 army commissar

Commissar

Commissar is the English transliteration of an official title used in Russia from the time of Peter the Great.The title was used during the Provisional Government for regional heads of administration, but it is mostly associated with a number of Cheka and military functions in Bolshevik and Soviet...

s, and 25 of 28 army corps commissars.

At first it was thought 25-50% of Red Army officers were purged, it is now known to be 3.7-7.7%. Previously, the size of the Red Army officer corp was underestimated and it was overlooked that most of those purged were merely expelled from the Party. 30% of officers purged 1937-9 were allowed back.

The wider purge

Eventually almost all of the BolshevikBolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

s who had played prominent roles during the Russian Revolution of 1917

Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution is the collective term for a series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. The Tsar was deposed and replaced by a provisional government in the first revolution of February 1917...

, or in Lenin's

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...