Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

Encyclopedia

The United Kingdom was the third country to test an independently developed nuclear weapon

, in October 1952. It is one of the five "Nuclear Weapons States" (NWS) under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

, which the UK ratified in 1968. The UK is currently thought to retain a weapons stockpile of around 160 operational nuclear warhead

s and 225 nuclear warheads in total but has refused to declare exact size of its arsenal.

Since the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

, the United States

and the United Kingdom have cooperated extensively on nuclear security matters. The special relationship

between the two countries has involved the exchange of classified scientific information and nuclear materials such as plutonium

. The UK has not run an independent nuclear weapons delivery system development and production programme since the cancellation of the Blue Streak missile

in the 1960s, instead it has pursued joint development (for its own use) of US delivery systems, designed and manufactured by Lockheed Martin

, and fitting them with warheads designed and manufactured by the UK's Atomic Weapons Research Establishment and its successor the Atomic Weapons Establishment

. In 1974 a US proliferation assessment noted that "In many cases [Britain's sensitive technology in nuclear and missile fields] is based on technology received from the US and could not legitimately be passed on without US permission."

In contrast with the other permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

, the United Kingdom currently operates only a single nuclear weapon delivery system since decommissioning its tactical WE.177

free-falling nuclear bombs in 1998. The present system consists of four Vanguard class

submarines based at HMNB Clyde

, armed with up to 16 Trident missile

s, which each carry nuclear warheads in up to eight MIRVs

, performing both strategic

and sub-strategic

deterrence roles.

While a firm decision has yet to be taken on the replacement of the UK's nuclear weapons, the manufacturer of the UK's warheads, AWE

, is currently undertaking research which is largely dedicated to providing new warheads and on 4 December 2006 the then Prime Minister Tony Blair

announced plans for a new class of nuclear missile submarines

.

In the Strategic Defence Review published in July 1998, the United Kingdom government stated that once the Vanguard submarines became fully operational (the fourth and final one, Vengeance

In the Strategic Defence Review published in July 1998, the United Kingdom government stated that once the Vanguard submarines became fully operational (the fourth and final one, Vengeance

, entered service on 27 November 1999), it would "maintain a stockpile of fewer than 200 operationally available warheads". The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute has estimated the figure as about 165, consisting of 144 deployed weapons plus an extra 15 percent as spares.

At the same time, the UK government indicated that warheads "required to provide a necessary processing margin and for technical surveillance purposes" were not included in the "fewer than 200" figure. However, as recently declassified archived documents on Chevaline

make clear, the 15% excess (referred to by SIPRI as for spares) is normally intended to provide the 'necessary processing margin', and 'surveillance rounds do not contain any nuclear material, being completely inert. These surveillance rounds are used to monitor deterioration in the many non-nuclear components of the warhead, and are best compared with inert training rounds. The SIPRI figures correspond accurately with the official announcements and are likely to be the most accurate. The Natural Resources Defense Council

speculates that a figure of 200 is accurate to within a few tens. In 2008 the National Audit Office

stated that the UK stockpile was of fewer than 160 operationally available nuclear warheads.

During a debate on the Queen's Speech on 26 May 2010 Foreign Secretary William Hague

reiterated that the UK has no more than 160 operationally available warheads, and announced that the total number will not exceed 225.

with the final test being the Julin Bristol

shot which took place on 26 November 1991. The apparently low numbers of UK tests is misleading when compared to the large numbers of tests carried out by the US, the Soviet Union

, China

, and especially France

; because the UK has had extensive access to US test data, obviating the need for UK tests: and an added factor is that many tests required are for 'weapon effects tests'; tests not of the nuclear device itself, but of the nuclear effects on hardened components designed to resist ABM attack. Numerous such 'effects' tests were done in support of the Chevaline

programme especially; and there is some evidence that some were permitted for the French programme to harden their RVs and warheads; because most French tests being under the ocean floor, access to measure 'weapon effects' was nigh impossible. An independent test programme would see the UK numbers soar to French levels. The UK government signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty

on 5 August 1963 along with the United States and the Soviet Union

which effectively restricted it to underground nuclear tests by outlawing testing in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. The UK signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

on 24 September 1996 and ratified it on 6 April 1998, having passed the necessary legislation on 18 March 1998 as the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998.

The UK has relied on the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System

The UK has relied on the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System

(BMEWS) and, in later years, Defense Support Program

(DSP) satellites for warning of a nuclear attack. Both of these systems are owned and controlled by the United States, although the UK has joint control over UK based systems. One of the four component radars for the BMEWS is based at RAF Fylingdales

in North Yorkshire

.

In 2003 the UK government stated that it will consent to a request from the US to upgrade the radar at Fylingdales for use in the US National Missile Defense

system.

Nevertheless, missile defence is not currently a significant political issue within the UK. The ballistic missile threat is perceived to be less severe, and consequently less of a priority, than other threats to its security.

, a significant effort by government and academia was made to assess the effects of a nuclear attack on the UK. A major government exercise, Square Leg

, was held in September 1980 and involved around 130 warheads with a total yield of 200 MtonTNT. This is probably the largest attack that the apparatus of the nation state could survive in some limited form. Observers have speculated that an actual exchange would be much larger with one academic describing a 200-megaton attack as an "extremely low figure and one which we find very difficult to take seriously". In the early 1980s it was thought an attack causing almost complete loss of life could be achieved with the use of less than 15% of the total nuclear yield available to the Soviets.

s entitled Protect and Survive

.

The booklet contained information on building a nuclear refuge

within a so-called 'fall out room' at home, sanitation, limiting fire hazards and descriptions of the audio signals for attack warning, fallout warning and all clear. It was anticipated that families might need to stay within the fall-out room for up to fourteen days after an attack almost without leaving it at all.

The government also prepared a recorded announcement which was to have been broadcast by the BBC if a nuclear attack ever did occur.

Sirens left over from the London Blitz during World War II

were also to be used to warn the public. The system was mostly dismantled in 1993.

and Rudolf Peierls

wrote a memorandum on the construction of "a radioactive super-bomb". Forwarded to the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), the secret MAUD Committee

to evaluate the possibilities was soon set up. British scientists worked initially alone on the atomic bomb under the cover name of Tube Alloys

, later becoming a partner in the tri-national Manhattan Project

under the Quebec Agreement

. The Manhattan Project resulted in the two nuclear weapons dropped over Japan

.

Prime Minister

Clement Attlee

set up a cabinet sub-committee

, the Gen 75 Committee (GEN.75)

(known informally as the "Atomic Bomb Committee"), to examine the feasibility as early as 29 August 1945. It was US refusal to continue nuclear cooperation with the UK after World War II (due to the McMahon Act of 1946 restricting foreign access to US nuclear technology) which eventually prompted the building of a bomb:

The committee, under pressure from Hugh Dalton

and Sir Stafford Cripps

to opt out of building the bomb due to its cost, eventually decided to go ahead not just because of considerations of Britain's prestige but also because of the likely industrial importance of atomic energy.

A nuclear programme started in 1946 under the control of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment

(incorporated into the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority

(UKAEA) in 1954), that was civilian in character, but was also tasked with the job of producing the fissile material, initially only plutonium 239, that was expected to be required for a military programme. It was based on a former airfield, Harwell

, Berkshire

; and a former Royal Ordnance Factory

, Risley in Cheshire

. Risley became the headquarters of the Industrial Division of UKAEA, and there were other sites under its control, notably the Calder Hall reactors at Windscale (later Sellafield

) used to produce weapons grade Pu-239. The first nuclear pile in the UK, GLEEP

, went critical at Harwell on 15 August 1947. AWRE was established at Aldermaston by the Ministry of Supply

; later becoming the Weapons Division of the (civilian) UKAEA, before being subsumed into the Ministry of Defence

in the 1970s.

William Penney

, a physicist

specialising in hydrodynamics was asked in October 1946 to prepare a report on the viability of building a UK weapon. Joining the Manhattan project in 1944, he had been in the observation plane Big Stink

over Nagasaki, and had also done damage assessment on the ground following Japan

's surrender. He had subsequently participated in the American Operation Crossroads

test at Bikini Atoll

. As a result of his report, the decision to proceed was formally made on 8 January 1947 at a meeting of the GEN.163 committee of six cabinet members, including Prime Minister

Clement Attlee

with Penney appointed to take charge of the programme.

The project was hidden under the name High Explosive Research or HER and was based initially at the Ministry of Supply

's Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) at Fort Halstead

in Kent, but in 1950 moved to a new site at AWRE Aldermaston

in Berkshire

. A particular problem was the McMahon Act. Although British scientists knew the areas of the Manhattan Project in which they had worked well, they only had the sketchiest details of those parts which they were not directly involved in. With the start of the Cold War

there had been some warming of nuclear relations between the UK and US governments, which led to hopes of American cooperation. However these were quickly dashed by the arrest in early 1950 of Klaus Fuchs

, a Soviet spy

working at Harwell. Plutonium production reactors were based at Windscale, later known as Sellafield

in Cumberland and construction began in September 1947, leading to the first plutonium metal ready in March 1952.

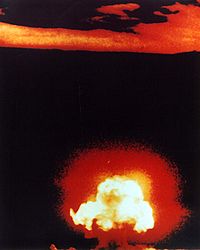

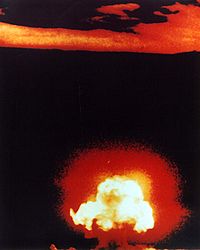

The first UK weapon test, Operation Hurricane

The first UK weapon test, Operation Hurricane

, was detonated below the frigate HMS Plym

anchored in the Monte Bello Islands on 3 October 1952. This led to the first deployed weapon, the Blue Danube

free-fall bomb, in November 1953. It was very similar to the American Mark 4 weapon in having a 60 inches (152.4 cm) diameter, 32 lens implosion system with a levitated core suspended within a natural uranium tamper. The warhead was contained within a bomb casing measuring 62 inches (1.6 m) diameter and 24 feet (7.3 m) long, and being so large, could only be carried by the V-Bomber fleet.

A nuclear landmine dubbed Brown Bunny, later Blue Bunny, and finally Blue Peacock

that used the Blue Danube warhead was developed from 1954 with the goal of deployment in the Rhine area of Germany

. The system would have been set to an eight-day timer in the case of invasion of Western Europe by the Soviets but was cancelled in February 1958 with only two built. It was judged that the risks posed by the nuclear fallout

and the political aspects of preparing for destruction and contamination of allied territory were simply too high to justify. A more usual reason for cancellation revealed by numerous archived declassified documents was that the Army felt it was too unwieldy and diverted their efforts into a successor, Violet Vision, based on the smaller successor to Blue Danube, Red Beard. None were ever built, the Army instead receiving US ADMs or Atomic Demolition Munitions

under the established procedures for supply of NATO allies from US stocks held in US custody in Europe. A sea mine based on the Blue Danube warhead and codenamed Cudgel was also envisaged for delivery by midget submarines, referred to by naval sources as "sneak craft"; perhaps reflecting a belief that these craft were really rather ungentlemanly methods of waging war. None were built.

A gaseous diffusion plant was built at Capenhurst

, near Chester

and started production in 1953 producing low enriched uranium (LEU). By 1957 it was capable of annually producing 125 kg of highly enriched uranium (HEU). The capacity was further increased and by 1959 it may have been producing as much as 1600 kg per year. At the end of 1961, having produced between 3.8 and 4.9 tonne

s of HEU it was switched over to LEU production for civil use. Additional plutonium production was provided by eight electricity generating Magnox

reactors at Calder Hall and Chapelcross which started operating in 1956 and 1959 respectively.

and a decision was made on 27 July 1954 to begin development of a thermonuclear bomb, making use of the more powerful nuclear fusion

reaction rather than nuclear fission

. There was little or no dissent in the House of Commons.

The Economist

The Economist

, the New Statesman

and many left-wing newspapers supported the government's policy of nuclear deterrence as a means of reducing the size of conventional forces. Their view (in 1954-55) is fairly summarised as being not opposed to nuclear deterrence and nuclear weapons, but in their view that of the United States would suffice, and that of the costs of the 'nuclear umbrella' was best left to be borne by the United States alone. Their attitudes to nuclear weapons have changed somewhat since then.

The first prototype, Short Granite, was detonated on 15 May 1957 in Operation Grapple

, with disappointing results at 300 ktonTNT, when the target requirement was 1 MtonTNT. A further test of Purple Granite yielded less at 200 ktonTNT. Further testing in 1958 got performance up to the requirement, but none were ever deployed, because the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

intervened, making fully developed and Service engineered designs available more quickly, and more cheaply. The first of these was the US Mk-28 weapon

which was anglicised and manufactured in the UK as Red Snow

and quickly deployed as Yellow Sun

Mk.2 in the V-bomber fleet. Red Snow became the warhead of choice for the Blue Steel

stand-off missile and some of the Skybolt missiles intended for carriage by the V-bombers. Under the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

5.4 tonnes of UK produced plutonium was sent to the US in return for 6.7 kg of tritium

and 7.5 tonnes of HEU over the period 1960-1979, replacing Capenhurst production, although much of the HEU was used not for weapons, but as fuel for the growing UK fleet of nuclear submarines, both of the Polaris variety and others numbering approx twelve.

Fifty-eight Blue Danube bombs were produced, although archived declassified files indicate that only a small proportion of these were ever serviceable at any one time. It remained in service until 1963, when it was replaced by Red Beard

, a smaller tactical boosted fission weapon

that used the same fissile core as Blue Danube and was deployed on many smaller aircraft than the V-bombers, both ashore and at sea aboard five carriers. Stocks of Red Beard were maintained in Cyprus

, Singapore

, and a smaller number in the UK.

After the detonation of US and Soviet thermonuclear weapons the UK deployed an Interim Megaton Weapon in the V-bomber fleet until a true thermonuclear weapon could be devised from the Christmas Island tests. This never tested interim weapon derived from the Orange Herald

warhead tested at Christmas Island on 31 May 1957 yielding 720 ktonTNT known as Green Grass was merely a very large unboosted pure fission weapon yielding 400 ktonTNT. It was the largest pure fission weapon ever deployed by any nuclear state. Green Grass was deployed first in a modified Blue Danube casing and known as Violet Club

. A later variant was deployed in a Yellow Sun

Mk.1 casing. A true thermonuclear device was planned for the later Yellow Sun

Mk.2 bomb, and after the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

the choice fell on a US Mk.28 warhead manufactured in the UK and known as Red Snow

. This Red Snow warhead was also fitted in the Blue Steel

, an air-launched stand-off missile which remained in service until Dec 1970. It was to have been replaced by Skybolt air-launched ballistic missiles purchased from the United States. In 1962 and 1960 respectively the UK cancelled their Blue Steel extended range upgrade (Blue Steel Mk2)and Blue Streak

missile projects. It was asserted in Parliament at the time that the Blue Streak missiles were cancelled because of their vulnerability to Soviet attack as they were liquid fuelled an immobile, although this vulnerability was in fact negligible. However, the main aim in British policy had changed from one of independence to interdependence- subsequently the Macmillan Government favoured the purchase of Skybolt missiles from the United States to the continuation of an independent project. Similarly, reassessments of Soviet capabilities changed military perceptions and led to the removal of Thor IRBM missiles in the UK

; and Jupiter IRBMs in Italy and Turkey; although the Turkish sites were implicated in an alleged deal following the Cuban Missile Crisis

. To consternation, and considerable protests, the incoming Kennedy administration cancelled Skybolt at the end of 1962 because it was believed by the US Secretary of State for Defense

, Robert McNamara

, that other delivery systems were progressing better than expected, and a further expensive system was surplus to US requirements.

and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

Harold Macmillan

, the Polaris Sales Agreement

, was announced on 21 December 1962 and HMS Resolution made her first Polaris-armed operational patrol on 15 June 1968. In the 1970s the UK Polaris RVs and warheads were vulnerable to the Soviet ABM

screen concentrated around Moscow, and the UK developed a Polaris improved-front-end (IFE) codenamed Chevaline

, designed to counter this ABM defence which threatened to completely nullify an independent UK deterrent posture. When Chevaline became public knowledge in 1980, it generated huge controversy as it had been kept secret by the four governments of Wilson, Heath, Wilson (again) and Callaghan, whilst costs rocketed; admittedly during a period of high inflation; until disclosed by the Thatcher government

. By the time it entered service in 1982 it had cost approx £1bn. The final Polaris/Chevaline patrol took place in 1996, two years after the first Trident-carrying submarine sailed on its first patrol.

As well as the establishment at Aldermaston, the UK nuclear weapons programme also has a factory at Burghfield

nearby which assembled the weapons and is responsible for their maintenance, and had another in Cardiff

which fabricated non-fissile components and a 2000 acre (8 km²) test range at Foulness

. Since 1993 the sites have been managed by private consortia. The Foulness and Cardiff facilities closed in October 1996 and February 1997 respectively.

The UK currently has four Vanguard class

The UK currently has four Vanguard class

submarines based at HMNB Clyde

in Scotland

, armed with nuclear-tipped Trident missile

s. The principle of operation is based on maintaining deterrent effect by always having at least one submarine at sea, and was designed for the Cold War

period. One submarine is normally undergoing maintenance and the remaining two in port or on training exercises. It has been suggested that the UK's ballistic missile submarine patrols are coordinated with those of the French

.

Each submarine carries 16 Trident II D-5 missiles, which can each carry up to twelve warheads. However, the UK government announced in 1998 that each submarine would carry only 48 warheads, an increase of 50% over the 32 warheads carried by Trident's predecessor, Chevaline, (halving the limit specified by the previous government), which is an average of three per missile. However one or two missiles per submarine are probably armed with fewer warheads for "sub-strategic" use causing others to be armed with more; but this is speculative.

The UK-designed warheads are thought to be selectable between 0.3, 5-10 and 100 kt (1.3, 21–42 and 420 TJ); the yields obtained using either the unboosted primary, the boosted primary, or the entire "physics package"; although it must be stressed that these yields and similar data are entirely speculative. The true position is unlikely to be known with certainty for many years; as was the case with the misplaced speculation about the earlier Chevaline programme; only now becoming publicly known. Although the UK designed, manufactured and owns the warheads, there is evidence that the warhead design is similar to, or even based on, the US W76

warhead fitted in some US Navy Trident missiles, with design data being supplied by the United States through the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

. The United Kingdom owns 58 missiles which are shared in a joint pool with the United States government and these are exchanged when requiring maintenance with missiles from the United States Navy

's own pool and vice versa.

Until August 1998, the UK also retained the WE.177

nuclear weapon manufactured in the mid-1960s to late 1970s, in air-dropped free-fall bomb and depth charge

versions. This left the four Vanguard class submarines, which replaced the Polaris ones in the early 1990s, as the United Kingdom's only nuclear weapons platform. It has been estimated by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

that the United Kingdom has built around 1,200 warheads since the first Hurricane

device of 1952. In terms of number of warheads, the UK arsenal was at its maximum size of about 350 in the 1970s, but this figure does not include the large numbers of US-owned warheads, bombs, nuclear depth bombs supplied from US stocks in Europe for use by NATO allies. At its peak, these numbered 327 for the British Army of the Rhine

in Germany alone.

(Prime Minister

at that time) told MPs it would be "unwise and dangerous" for the UK to give up its nuclear weapons. He outlined plans to spend up to £20bn on a new generation of submarines for Trident missiles.

He said submarine numbers may be cut from four to three, while the number of nuclear warheads would be cut by 20% to 160. Mr Blair said although the Cold War had ended, the UK needed nuclear weapons, as no-one could be sure another nuclear threat would not emerge in the future.

role. This arrangement commenced in 1958 as Project E

to provide nuclear weapons to the RAF prior to a sufficient number of Britain's own nuclear weapons becoming available.

The weapons deployed included nuclear artillery

, nuclear demolition mines and warheads for Corporal and Lance missiles in Germany

; theatre nuclear weapons on RAF

aircraft; Mark 101

nuclear depth bomb

s on RAF Shackleton

maritime patrol aircraft, later replaced by a modern successor, the B-57

deployed on RAF Nimrod aircraft.

The Lance missiles were purchased in 1975, to replace Honest John missiles which had been bought in 1960; and were themselves a replacement for the US Corporal missiles deployed in Germany by the Royal Artillery

. Not generally recognised is the fact that the Royal Artillery deployed a numerically greater quantity of US nuclear weapons than the RAF and Royal Navy combined, peaking at 277 in 1976-78; with a further 50 ADMs deployed with another British Army

unit, the Royal Engineers

, peaking in 1971-81. The dual-key agreement for controlling US tactical nuclear weapons, known as the Heidelberg Agreement, was made on 30 August 1961. The UK sponsored access for the Canadian Army Honest John missile deployments to the US/UK nuclear warhead storage sites.

The UK continues to permit the US to deploy nuclear weapons from its territory, the first having arrived in 1954. During the 1980s nuclear armed USAF Ground Launched Cruise Missile

s were deployed at RAF Greenham Common

and RAF Molesworth

. As of 2005 it is believed that approximately 110 tactical B61 nuclear bomb

s are stored at RAF Lakenheath

for deployment by USAF F-15E Strike Eagle

aircraft.

and approximately 14 miles (22.5 km) south-west of Reading, Berkshire

, near a village called Aldermaston

, bordering with Tadley

. It was built in 1949 on the site of a former World War II

Royal Air Force

base and converted to nuclear weapons research, design and development in the 1950s. Although some early test devices were probably assembled on this site, final assembly of Service-engineered weapons takes place at the nearby site of Burghfield.

and Burghfield

near Reading, Berkshire

. These were the only two Royal Ordnance Factories (ROFs) not privatised

in the 1980s.

ROF Cardiff, which closed in 1997, was involved in nuclear weapons programmes since 1961. The site was used for the task of recycling old nuclear weapons and precisely shaping uranium 235 (U235) and metallic beryllium

components for the boosted fission devices used as primaries or 'triggers' in modern thermonuclear weapons. ROF Burghfield was a former Filling Factory

, opened in 1942, and run as an Agency Factory, by Imperial Tobacco

, to fill Oerlikon 20 mm

ammunition.

The anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom consists of groups who oppose nuclear technologies such as nuclear power

The anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom consists of groups who oppose nuclear technologies such as nuclear power

and nuclear weapons. Many different groups and individuals have been involved in anti-nuclear demonstrations and protests

over the years.

One of the most prominent anti-nuclear groups in the UK is the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

(CND). CND's Aldermaston Marches began in 1958 and continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches. One significant anti-nuclear mobilization in the 1980s was the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp

. In London, in October 1983, more than 300,000 people assembled in Hyde Park as part of the largest protest against nuclear weapons in British history. In 2005 in Britain, there were many protests about the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system

with a newer model.

The UK has relaxed its nuclear posture since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Labour

government's 1998 Strategic Defence Review

made a number of reductions from the plans announced by the previous Conservative

government:

Current UK posture as outlined in the Strategic Defence Review of 1998 is as it has been for many years. Only the delivery methods have changed. Trident SLBMs still provide the long-range strategic element as they have done for some years. Until 1998 the free-fall WE.177A, WE.177B and WE.177C bombs provided an aircraft-delivered sub-strategic option in addition to their designed function of tactical battlefield weapons. With the retirement of WE.177, a sub-strategic warhead is stated by Ministers to be incorporated into some (but not all) Trident missiles deployed. The exact mix of weapons on each submarine is unknown as is the numbers and warhead yield. Current UK thinking is that the capacity to launch a very limited strike is a more credible deterrent in the current world situation than use of a MIRVed strategic system.

of the Royal Navy. Both the Prime Minister and the Polaris Control Officer would be able to see each other on their monitors when the command was given. If the link failed – for instance during a nuclear attack or when the PM was away from Downing Street – the Prime Minister would send an authentication code which could be verified at Northwood. The Commander in Chief would then broadcast a firing order to the Polaris submarines via the Very Low Frequency radio station at Rugby. The UK has not deployed control equipment requiring codes to be sent before weapons can be used, such as the U.S. Permissive Action Link

, which if installed would preclude the possibility that military officers could launch British nuclear weapons without authorisation.

Until 1998, when it was withdrawn from service, the WE.177 bomb was armed with a standard tubular pin tumbler lock

Until 1998, when it was withdrawn from service, the WE.177 bomb was armed with a standard tubular pin tumbler lock

(as used on bicycle locks) and a standard allen key was used to set yield and burst height. Currently, British Trident commanders are able to launch their missiles without authorisation, whereas their American colleagues cannot. At the end of the Cold War the U.S. Fail Safe Commission recommended installing devices to prevent rogue commanders persuading their crews to launch unauthorised nuclear attacks. This was endorsed by the Nuclear Posture Review and Trident Coded Control Devices were fitted to all U.S. SSBNs by 1997. These devices prevented an attack until a launch code had been sent by the Chiefs of Staff on behalf of the President. The UK took a decision not to install Trident CCDs or their equivalent on the grounds that an aggressor might be able to wipe out the British chain of command before a launch order had been sent.

In December 2008 BBC Radio 4 made a programme titled The Human Button, providing new information on the manner in which the United Kingdom could launch its nuclear weapons, particularly relating to safeguards against a rogue launch. Former Chief of the Defence Staff

(most senior officer of all British armed forces

) and Chief of the General Staff

(most senior officer in the British Army

), General Lord Guthrie of Craigiebank

, explained that the highest level of safeguard was against a prime minister

ordering a launch without due cause: Lord Guthrie stated that the constitutional structure of the United Kingdom provided some protection against such an occurrence, as while the Prime Minister is the chief executive and so practically commands the armed services, the ultimate commander-in-chief is the Monarch

, to whom the chief of the defence staff could appeal:

"the chief of the defence staff, if he really did think the prime minister had gone mad, would make quite sure that that order was not obeyed... You have to remember that actually prime ministers give direction, they tell the chief of the defence staff what they want, but it's not prime ministers who actually tell a sailor to press a button in the middle of the Atlantic. The armed forces are loyal, and we live in a democracy, but actually their ultimate authority is the Queen."

The same interview pointed out that while the Prime Minister would have the constitutional authority to fire the Chief of the Defence Staff, he could not appoint a replacement as the position is appointed by the monarch. During the Cold War the Prime Minister was also required to name a senior member of the cabinet as his/her designated-survivor, who would have the authority to order a nuclear response in the event of an attack incapacitating the Prime Minister, and this system was re-adopted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States.

The programme also addressed the workings of the system; detailing that two persons are required

to authenticate each stage of the process before launching, with the submarine captain only able to access the firing trigger after two safes have been opened with keys held by the ship's executive and weapons engineering officers. It was explained that all prime ministers issue hand-written orders, termed the letters of last resort

, seen by their eyes only, sealed and stored within the safes of each of the four Royal Navy trident submarines: These notes instruct the captain of what action to take in the event of the United Kingdom being attacked with nuclear weapons that destroy Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom and/or the chain of command. Although the final orders of the Prime Minister are at his or her discretion, and no fixed options exist, four known options are often presented to prime ministers by military advisers when writing such notes of last resort: (i) Captain ordered to respond to the nuclear attack on the UK by launching submarine's nuclear weapons; (ii) Captain ordered not to respond with nuclear weapons; (iii) Captain ordered to use own judgement whether to return fire with nuclear weapons; (iv) Captain ordered to place himself and ship under the command of Her Majesty's Government in Australia

, or alternatively of the President of the United States

. This system of issuing notes containing orders in the event of the head of government's death is said to be unique to the United Kingdom (although the concept of written last orders, particularly of a ship's captain, is a naval tradition), with other nuclear powers using different procedures. Such orders are destroyed unopened whenever a prime minister leaves office, so the decision of its use or not by previous prime ministers are known only to them - however, all relevant former prime ministers have supported an "independent nuclear deterrent", as does incumbent David Cameron

. Only former prime minister Lord Callaghan has given any insight on his orders: Callaghan stated that, although in a situation where nuclear weapon use was required - and thus the whole purpose and value of the weapon as a deterrent had failed - he would have ordered use of nuclear weapons, if needed: ...if we had got to that point, where it was, I felt it was necessary to do it, then I would have done it (used the weapon)...but if I had lived after pressing that button, I could have never forgiven myself.

The process by which a Trident submarine would determine if the British government continues to function includes, amongst other checks, establishing whether BBC Radio 4

continues broadcasting.

The Government of the United Kingdom has announced plans to renew the UK's only nuclear weapons system, the Trident missile system. They have published a white paper

The Future of the United Kingdom’s Nuclear Deterrent in which they state that the renewal is fully compatible with the United Kingdom's treaty commitments and international law. These arguments are summarised in a question and answer briefing published by UK Permanent Representative to the Conference on Disarmament

s. The first, commissioned by Peacerights, was given on 19 December 2005 by Rabinder Singh

QC

and Professor

Christine Chinkin

of Matrix Chambers. It addressed '...whether Trident or a likely replacement to Trident breaches customary international law

'

Drawing on the International Court of Justice

(ICJ) opinion, Singh and Chinkin advised that:

The second opinion was commissioned by Greenpeace

and given by Philippe Sands

QC

and Helen Law, also of Matrix Chambers

, on 13 November 2006. The opinion addressed

With regards to the jus ad bellum, Sands and Law advised that

The phrase "very survival of the state" is a direct quote from paragraph 97 of the ICJ ruling. With regards to international humanitarian law, they advised that

Finally, with reference to the NPT, Sands and Law advised that

debate to authorize the replacement of Trident, Margaret Beckett

stated:

The subsequent vote was won overwhelmingly, including unanimous support from the opposition Conservative Party

.

The Government position remains that it is abiding by the NPT legally in renewing Trident and Britain has the right to possess nuclear weapons, a position reiterated by Tony Blair

in PMQs on 21 February 2007.

In contrast, the report by Sands was commissioned solely by Greenpeace

and the report by Singh and Chinkin by the Peace Rights group, both notable groups in opposition to renewal, use or proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Furthermore, the British Government and NATO do not recognise advisory opinion of the ICJ, as interpreter of IHL and referred to by Sands et al., (see Advisory Opinion

) with regard to use of nuclear weaponry as legally binding.

This position is held in common with all five nuclear states as defined in the NPT. However, only the United Kingdom has expressed its opposition to the establishment of a new legally binding treaty to prevent the threat or use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states by its vote in the United Nations General Assembly

in 1998.

This legal position is further discussed in the article International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons.

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

, in October 1952. It is one of the five "Nuclear Weapons States" (NWS) under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is a landmark international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy and to...

, which the UK ratified in 1968. The UK is currently thought to retain a weapons stockpile of around 160 operational nuclear warhead

Warhead

The term warhead refers to the explosive material and detonator that is delivered by a missile, rocket, or torpedo.- Etymology :During the early development of naval torpedoes, they could be equipped with an inert payload that was intended for use during training, test firing and exercises. This...

s and 225 nuclear warheads in total but has refused to declare exact size of its arsenal.

Since the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

The 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement is a bilateral treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom on nuclear weapons cooperation.It was signed after the UK successfully tested its first hydrogen bomb during Operation Grapple. While the U.S...

, the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and the United Kingdom have cooperated extensively on nuclear security matters. The special relationship

Special relationship

The Special Relationship is a phrase used to describe the exceptionally close political, diplomatic, cultural, economic, military and historical relations between the United Kingdom and the United States, following its use in a 1946 speech by British statesman Winston Churchill...

between the two countries has involved the exchange of classified scientific information and nuclear materials such as plutonium

Plutonium

Plutonium is a transuranic radioactive chemical element with the chemical symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, forming a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four oxidation...

. The UK has not run an independent nuclear weapons delivery system development and production programme since the cancellation of the Blue Streak missile

Blue Streak missile

The Blue Streak missile was a British medium range ballistic missile . The Operational Requirement for the missile was issued in 1955 and the design was complete by 1957...

in the 1960s, instead it has pursued joint development (for its own use) of US delivery systems, designed and manufactured by Lockheed Martin

Lockheed Martin

Lockheed Martin is an American global aerospace, defense, security, and advanced technology company with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta in March 1995. It is headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland, in the Washington Metropolitan Area....

, and fitting them with warheads designed and manufactured by the UK's Atomic Weapons Research Establishment and its successor the Atomic Weapons Establishment

Atomic Weapons Establishment

The Atomic Weapons Establishment is responsible for the design, manufacture and support of warheads for the United Kingdom's nuclear deterrent. AWE plc is responsible for the day-to-day operations of AWE...

. In 1974 a US proliferation assessment noted that "In many cases [Britain's sensitive technology in nuclear and missile fields] is based on technology received from the US and could not legitimately be passed on without US permission."

In contrast with the other permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is one of the principal organs of the United Nations and is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers, outlined in the United Nations Charter, include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of...

, the United Kingdom currently operates only a single nuclear weapon delivery system since decommissioning its tactical WE.177

WE.177

WE.177 was the last air-delivered tactical nuclear weapon of the British Armed Forces. There were three versions; WE.177A was a boosted fission weapon, while WE.177B and WE.177C were thermonuclear weapons...

free-falling nuclear bombs in 1998. The present system consists of four Vanguard class

Vanguard class submarine

The Vanguard class are the Royal Navy's current nuclear ballistic missile submarines , each armed with up to 16 Trident II Submarine-launched ballistic missiles...

submarines based at HMNB Clyde

HMNB Clyde

Her Majesty's Naval Base Clyde is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy...

, armed with up to 16 Trident missile

Trident missile

The Trident missile is a submarine-launched ballistic missile equipped with multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles . The Fleet Ballistic Missile is armed with nuclear warheads and is launched from nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines . Trident missiles are carried by fourteen...

s, which each carry nuclear warheads in up to eight MIRVs

Multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle

A multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle warhead is a collection of nuclear weapons carried on a single intercontinental ballistic missile or a submarine-launched ballistic missile . Using a MIRV warhead, a single launched missile can strike several targets, or fewer targets redundantly...

, performing both strategic

Military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired strategic goals. Derived from the Greek strategos, strategy when it appeared in use during the 18th century, was seen in its narrow sense as the "art of the general", 'the art of arrangement' of troops...

and sub-strategic

Tactical nuclear weapon

A tactical nuclear weapon refers to a nuclear weapon which is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations. This is as opposed to strategic nuclear weapons which are designed to menace large populations, to damage the enemy's ability to wage war, or for general deterrence...

deterrence roles.

While a firm decision has yet to be taken on the replacement of the UK's nuclear weapons, the manufacturer of the UK's warheads, AWE

Atomic Weapons Establishment

The Atomic Weapons Establishment is responsible for the design, manufacture and support of warheads for the United Kingdom's nuclear deterrent. AWE plc is responsible for the day-to-day operations of AWE...

, is currently undertaking research which is largely dedicated to providing new warheads and on 4 December 2006 the then Prime Minister Tony Blair

Tony Blair

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair is a former British Labour Party politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2 May 1997 to 27 June 2007. He was the Member of Parliament for Sedgefield from 1983 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007...

announced plans for a new class of nuclear missile submarines

British replacement of the Trident system

The British replacement of Trident is a proposal to replace the existing Vanguard class of four Trident ballistic-missile armed submarines with a new class designed to continue a nuclear deterrent after the current boats reach the end of their service lives...

.

Number of warheads

HMS Vengeance (S31)

HMS Vengeance is the fourth and final of the Royal Navy. Vengeance carries the Trident ballistic missile, the UK's nuclear deterrent....

, entered service on 27 November 1999), it would "maintain a stockpile of fewer than 200 operationally available warheads". The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute has estimated the figure as about 165, consisting of 144 deployed weapons plus an extra 15 percent as spares.

At the same time, the UK government indicated that warheads "required to provide a necessary processing margin and for technical surveillance purposes" were not included in the "fewer than 200" figure. However, as recently declassified archived documents on Chevaline

Chevaline

Chevaline was a system to improve the penetrability of the British Polaris missile warheads. Devised as an answer to the improved Soviet defences around Moscow, the system was intended to increase the probability that at least one warhead would penetrate the city's anti-ballistic missile defences,...

make clear, the 15% excess (referred to by SIPRI as for spares) is normally intended to provide the 'necessary processing margin', and 'surveillance rounds do not contain any nuclear material, being completely inert. These surveillance rounds are used to monitor deterioration in the many non-nuclear components of the warhead, and are best compared with inert training rounds. The SIPRI figures correspond accurately with the official announcements and are likely to be the most accurate. The Natural Resources Defense Council

Natural Resources Defense Council

The Natural Resources Defense Council is a New York City-based, non-profit, non-partisan international environmental advocacy group, with offices in Washington DC, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Beijing...

speculates that a figure of 200 is accurate to within a few tens. In 2008 the National Audit Office

National Audit Office (United Kingdom)

The National Audit Office is an independent Parliamentary body in the United Kingdom which is responsible for auditing central government departments, government agencies and non-departmental public bodies...

stated that the UK stockpile was of fewer than 160 operationally available nuclear warheads.

During a debate on the Queen's Speech on 26 May 2010 Foreign Secretary William Hague

William Hague

William Jefferson Hague is the British Foreign Secretary and First Secretary of State. He served as Leader of the Conservative Party from June 1997 to September 2001...

reiterated that the UK has no more than 160 operationally available warheads, and announced that the total number will not exceed 225.

Weapons tests

Different sources give the number of test explosions that the UK has conducted as either 44 or 45. The 24 tests from December 1962 onwards were in conjunction with the United States at the Nevada Test SiteNevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site , previously the Nevada Test Site , is a United States Department of Energy reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about northwest of the city of Las Vegas...

with the final test being the Julin Bristol

Julin Bristol

Julin Bristol was the last British nuclear test, and took place at the Nevada Test Site on 26 November 1991. With a yield of less than 20 kilotons it may have been a proof test of some aspect of the British-designed warheads fitted to those Trident missiles in the British arsenal, possibly of a...

shot which took place on 26 November 1991. The apparently low numbers of UK tests is misleading when compared to the large numbers of tests carried out by the US, the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, and especially France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

; because the UK has had extensive access to US test data, obviating the need for UK tests: and an added factor is that many tests required are for 'weapon effects tests'; tests not of the nuclear device itself, but of the nuclear effects on hardened components designed to resist ABM attack. Numerous such 'effects' tests were done in support of the Chevaline

Chevaline

Chevaline was a system to improve the penetrability of the British Polaris missile warheads. Devised as an answer to the improved Soviet defences around Moscow, the system was intended to increase the probability that at least one warhead would penetrate the city's anti-ballistic missile defences,...

programme especially; and there is some evidence that some were permitted for the French programme to harden their RVs and warheads; because most French tests being under the ocean floor, access to measure 'weapon effects' was nigh impossible. An independent test programme would see the UK numbers soar to French levels. The UK government signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty

Partial Test Ban Treaty

The treaty banning nuclear weapon tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and under water, often abbreviated as the Partial Test Ban Treaty , Limited Test Ban Treaty , or Nuclear Test Ban Treaty is a treaty prohibiting all test detonations of nuclear weapons...

on 5 August 1963 along with the United States and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

which effectively restricted it to underground nuclear tests by outlawing testing in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. The UK signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty bans all nuclear explosions in all environments, for military or civilian purposes. It was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 September 1996 but it has not entered into force.-Status:...

on 24 September 1996 and ratified it on 6 April 1998, having passed the necessary legislation on 18 March 1998 as the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998.

Warning systems

Ballistic Missile Early Warning System

The United States Air Force Ballistic Missile Early Warning System was the first operational ballistic missile detection radar. The original system was built in 1959 and could provide long-range warning of a ballistic missile attack over the polar region of the Northern Hemisphere. They also...

(BMEWS) and, in later years, Defense Support Program

Defense Support Program

The Defense Support Program is a program of the U.S. Air Force that operates the reconnaissance satellites which form the principal component of the Satellite Early Warning System currently used by the United States....

(DSP) satellites for warning of a nuclear attack. Both of these systems are owned and controlled by the United States, although the UK has joint control over UK based systems. One of the four component radars for the BMEWS is based at RAF Fylingdales

RAF Fylingdales

RAF Fylingdales is a Royal Air Force station on Snod Hill in the North York Moors, England. Its motto is "Vigilamus" . It is a radar base and part of the United States-controlled Ballistic Missile Early Warning System...

in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is a non-metropolitan or shire county located in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England, and a ceremonial county primarily in that region but partly in North East England. Created in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972 it covers an area of , making it the largest...

.

In 2003 the UK government stated that it will consent to a request from the US to upgrade the radar at Fylingdales for use in the US National Missile Defense

National Missile Defense

National missile defense is a generic term for a type of missile defense intended to shield an entire country against incoming missiles, such as intercontinental ballistic missile or other ballistic missiles. Interception might be by anti-ballistic missiles or directed-energy weapons such as lasers...

system.

Nevertheless, missile defence is not currently a significant political issue within the UK. The ballistic missile threat is perceived to be less severe, and consequently less of a priority, than other threats to its security.

Attack scenarios

During the Cold WarCold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, a significant effort by government and academia was made to assess the effects of a nuclear attack on the UK. A major government exercise, Square Leg

Square Leg

Square Leg was a 1980 British government home defence exercise that assessed the effects of a Soviet nuclear attack. It was assumed that 131 nuclear weapons would fall on Britain with a total yield of 205 megatons...

, was held in September 1980 and involved around 130 warheads with a total yield of 200 MtonTNT. This is probably the largest attack that the apparatus of the nation state could survive in some limited form. Observers have speculated that an actual exchange would be much larger with one academic describing a 200-megaton attack as an "extremely low figure and one which we find very difficult to take seriously". In the early 1980s it was thought an attack causing almost complete loss of life could be achieved with the use of less than 15% of the total nuclear yield available to the Soviets.

Civil defence

During the cold war, various governments developed civil defence programmes aimed to prepare civilian and local government infrastructure for a nuclear strike on the UK. A series of seven Civil Defence Bulletin films were produced in 1964; and in the 1980s the most famous such programme was probably the series of booklets and public information filmPublic information film

Public Information Films are a series of government commissioned short films, shown during television advertising breaks in the UK. The US equivalent is the Public Service Announcement .-Subjects:...

s entitled Protect and Survive

Protect and Survive

Protect and Survive was a public information series on civil defence produced by the British government during the late 1970s and early 1980s. It was intended to inform British citizens on how to protect themselves during a nuclear attack, and consisted of a mixture of pamphlets, radio broadcasts,...

.

The booklet contained information on building a nuclear refuge

Fallout shelter

A fallout shelter is an enclosed space specially designed to protect occupants from radioactive debris or fallout resulting from a nuclear explosion. Many such shelters were constructed as civil defense measures during the Cold War....

within a so-called 'fall out room' at home, sanitation, limiting fire hazards and descriptions of the audio signals for attack warning, fallout warning and all clear. It was anticipated that families might need to stay within the fall-out room for up to fourteen days after an attack almost without leaving it at all.

The government also prepared a recorded announcement which was to have been broadcast by the BBC if a nuclear attack ever did occur.

Sirens left over from the London Blitz during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

were also to be used to warn the public. The system was mostly dismantled in 1993.

Weapons programmes

See also History of nuclear weaponsHistory of nuclear weapons

The history of nuclear weapons chronicles the development of nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons possess enormous destructive potential derived from nuclear fission or nuclear fusion reactions...

Tube Alloys and Manhattan Project

The United Kingdom's nuclear weapons had their genesis in the Second World War when two recently exiled atomic scientists, Otto FrischOtto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch , Austrian-British physicist. With his collaborator Rudolf Peierls he designed the first theoretical mechanism for the detonation of an atomic bomb in 1940.- Overview :...

and Rudolf Peierls

Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, CBE was a German-born British physicist. Rudolf Peierls had a major role in Britain's nuclear program, but he also had a role in many modern sciences...

wrote a memorandum on the construction of "a radioactive super-bomb". Forwarded to the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), the secret MAUD Committee

MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was the beginning of the British atomic bomb project, before the United Kingdom joined forces with the United States in the Manhattan Project.-Frisch & Peierls:...

to evaluate the possibilities was soon set up. British scientists worked initially alone on the atomic bomb under the cover name of Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the code-name for the British nuclear weapon directorate during World War II, when the development of nuclear weapons was kept at such a high level of secrecy that it had to be referred to by code even in the highest circles of government...

, later becoming a partner in the tri-national Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

under the Quebec Agreement

Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement is an Anglo-Canadian-American document outlining the terms of nuclear nonproliferation between the United Kingdom and the United States, and signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt on August 19, 1943, two years before the end of World War II, in Quebec City,...

. The Manhattan Project resulted in the two nuclear weapons dropped over Japan

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

.

Post-war development programme

The United Kingdom started independently developing nuclear weapons again shortly after the war. LabourLabour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

set up a cabinet sub-committee

United Kingdom cabinet committee

The executive arm of the United Kingdom government is controlled by the Cabinet, a group of senior government ministers chaired by the Prime Minister. The Cabinet has a group of committees called cabinet committees, which perform most of the day-to-day work of cabinet government.The committee...

, the Gen 75 Committee (GEN.75)

Gen 75 Committee

The Gen 75 Committee was a subcommittee of the British Cabinet, convened by Prime Minister Clement Attlee on 29 August 1945. The purpose of the committee was to discuss and establish the British government's nuclear policy...

(known informally as the "Atomic Bomb Committee"), to examine the feasibility as early as 29 August 1945. It was US refusal to continue nuclear cooperation with the UK after World War II (due to the McMahon Act of 1946 restricting foreign access to US nuclear technology) which eventually prompted the building of a bomb:

The committee, under pressure from Hugh Dalton

Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton PC was a British Labour Party politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947, when he was implicated in a political scandal involving budget leaks....

and Sir Stafford Cripps

Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour politician of the first half of the 20th century. During World War II he served in a number of positions in the wartime coalition, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union and Minister of Aircraft Production...

to opt out of building the bomb due to its cost, eventually decided to go ahead not just because of considerations of Britain's prestige but also because of the likely industrial importance of atomic energy.

A nuclear programme started in 1946 under the control of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment

Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment near Harwell, Oxfordshire, was the main centre for atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from the 1940s to the 1990s.-Founding:...

(incorporated into the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority

United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority

The United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority is a UK government research organisation responsible for the development of nuclear fusion power. It is an executive non-departmental public body of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and was formerly chaired by Lady Barbara Judge CBE...

(UKAEA) in 1954), that was civilian in character, but was also tasked with the job of producing the fissile material, initially only plutonium 239, that was expected to be required for a military programme. It was based on a former airfield, Harwell

Harwell, Oxfordshire

Harwell is a village and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse west of Didcot. It was part of Berkshire until the 1974 boundary changes transferred it to Oxfordshire.-Amenities:...

, Berkshire

Berkshire

Berkshire is a historic county in the South of England. It is also often referred to as the Royal County of Berkshire because of the presence of the royal residence of Windsor Castle in the county; this usage, which dates to the 19th century at least, was recognised by the Queen in 1957, and...

; and a former Royal Ordnance Factory

Royal Ordnance Factory

Royal Ordnance Factories was the collective name of the UK government's munitions factories in and after World War II. Until privatisation in 1987 they were the responsibility of the Ministry of Supply and later the Ministry of Defence....

, Risley in Cheshire

Cheshire

Cheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

. Risley became the headquarters of the Industrial Division of UKAEA, and there were other sites under its control, notably the Calder Hall reactors at Windscale (later Sellafield

Sellafield

Sellafield is a nuclear reprocessing site, close to the village of Seascale on the coast of the Irish Sea in Cumbria, England. The site is served by Sellafield railway station. Sellafield is an off-shoot from the original nuclear reactor site at Windscale which is currently undergoing...

) used to produce weapons grade Pu-239. The first nuclear pile in the UK, GLEEP

GLEEP

GLEEP, which stood for Graphite Low Energy Experimental Pile, was a long-lived experimental British nuclear reactor. Run for the first time on August 15, 1947, it was the first reactor to operate in Western Europe....

, went critical at Harwell on 15 August 1947. AWRE was established at Aldermaston by the Ministry of Supply

Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply was a department of the UK Government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. There was, however, a separate ministry responsible for aircraft production and the Admiralty retained...

; later becoming the Weapons Division of the (civilian) UKAEA, before being subsumed into the Ministry of Defence

Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom)

The Ministry of Defence is the United Kingdom government department responsible for implementation of government defence policy and is the headquarters of the British Armed Forces....

in the 1970s.

William Penney

William George Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney OM, KBE PhD, DSc, , FRS, FRSE, FIC, Hon FCGI was a British mathematician who was responsible for the development of British nuclear technology, following World War II...

, a physicist

Physicist

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole...

specialising in hydrodynamics was asked in October 1946 to prepare a report on the viability of building a UK weapon. Joining the Manhattan project in 1944, he had been in the observation plane Big Stink

Big Stink

Big Stink was the name of a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber that participated in the atomic bomb attack on Nagasaki, Japan on August 9, 1945...

over Nagasaki, and had also done damage assessment on the ground following Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

's surrender. He had subsequently participated in the American Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. It was the first test of a nuclear weapon after the Trinity nuclear test in July 1945...

test at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll is an atoll, listed as a World Heritage Site, in the Micronesian Islands of the Pacific Ocean, part of Republic of the Marshall Islands....

. As a result of his report, the decision to proceed was formally made on 8 January 1947 at a meeting of the GEN.163 committee of six cabinet members, including Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

with Penney appointed to take charge of the programme.

The project was hidden under the name High Explosive Research or HER and was based initially at the Ministry of Supply

Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply was a department of the UK Government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. There was, however, a separate ministry responsible for aircraft production and the Admiralty retained...

's Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) at Fort Halstead

Fort Halstead

Fort Halstead is a research site of Dstl, an Executive Agency of the UK Ministry of Defence. It is situated on the crest of the Kentish North Downs, overlooking the town of Sevenoaks...

in Kent, but in 1950 moved to a new site at AWRE Aldermaston

Atomic Weapons Establishment

The Atomic Weapons Establishment is responsible for the design, manufacture and support of warheads for the United Kingdom's nuclear deterrent. AWE plc is responsible for the day-to-day operations of AWE...

in Berkshire

Berkshire

Berkshire is a historic county in the South of England. It is also often referred to as the Royal County of Berkshire because of the presence of the royal residence of Windsor Castle in the county; this usage, which dates to the 19th century at least, was recognised by the Queen in 1957, and...

. A particular problem was the McMahon Act. Although British scientists knew the areas of the Manhattan Project in which they had worked well, they only had the sketchiest details of those parts which they were not directly involved in. With the start of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

there had been some warming of nuclear relations between the UK and US governments, which led to hopes of American cooperation. However these were quickly dashed by the arrest in early 1950 of Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II...

, a Soviet spy

SPY

SPY is a three-letter acronym that may refer to:* SPY , ticker symbol for Standard & Poor's Depositary Receipts* SPY , a satirical monthly, trademarked all-caps* SPY , airport code for San Pédro, Côte d'Ivoire...

working at Harwell. Plutonium production reactors were based at Windscale, later known as Sellafield

Sellafield

Sellafield is a nuclear reprocessing site, close to the village of Seascale on the coast of the Irish Sea in Cumbria, England. The site is served by Sellafield railway station. Sellafield is an off-shoot from the original nuclear reactor site at Windscale which is currently undergoing...

in Cumberland and construction began in September 1947, leading to the first plutonium metal ready in March 1952.

First test and early systems

Operation Hurricane

Operation Hurricane was the test of the first British atomic device on 3 October 1952. A plutonium implosion device was detonated in the lagoon between the Montebello Islands, Western Australia....

, was detonated below the frigate HMS Plym

HMS Plym (K271)

HMS Plym was a River class frigate that served in the Royal Navy between 1943 and 1952.-Construction:Plym was built to the Royal Navy's specifications as a Group II River class frigate...

anchored in the Monte Bello Islands on 3 October 1952. This led to the first deployed weapon, the Blue Danube

Blue Danube (nuclear weapon)

Blue Danube was the first operational British nuclear weapon. It also went by a variety of other names, including Smallboy, the Mk.1 Atom Bomb, Special Bomb and OR.1001, a reference to the Operational Requirement it was built to fill...

free-fall bomb, in November 1953. It was very similar to the American Mark 4 weapon in having a 60 inches (152.4 cm) diameter, 32 lens implosion system with a levitated core suspended within a natural uranium tamper. The warhead was contained within a bomb casing measuring 62 inches (1.6 m) diameter and 24 feet (7.3 m) long, and being so large, could only be carried by the V-Bomber fleet.

A nuclear landmine dubbed Brown Bunny, later Blue Bunny, and finally Blue Peacock

Blue Peacock

Blue Peacock, renamed from Blue Bunny and originally dubbed Brown Bunny, was the codename of a British tactical nuclear weapon project in the 1950s—dubbed the chicken-powered nuclear bomb by the press....

that used the Blue Danube warhead was developed from 1954 with the goal of deployment in the Rhine area of Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. The system would have been set to an eight-day timer in the case of invasion of Western Europe by the Soviets but was cancelled in February 1958 with only two built. It was judged that the risks posed by the nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout

Fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and shock wave have passed. It commonly refers to the radioactive dust and ash created when a nuclear weapon explodes...

and the political aspects of preparing for destruction and contamination of allied territory were simply too high to justify. A more usual reason for cancellation revealed by numerous archived declassified documents was that the Army felt it was too unwieldy and diverted their efforts into a successor, Violet Vision, based on the smaller successor to Blue Danube, Red Beard. None were ever built, the Army instead receiving US ADMs or Atomic Demolition Munitions

Atomic demolition munitions

Atomic demolition munitions , colloquially known as nuclear land mines, are small nuclear explosive devices. ADMs were developed for both military and civilian purposes. As weapons, they were designed to be exploded in the forward battle area, in order to block or channel enemy forces. ...

under the established procedures for supply of NATO allies from US stocks held in US custody in Europe. A sea mine based on the Blue Danube warhead and codenamed Cudgel was also envisaged for delivery by midget submarines, referred to by naval sources as "sneak craft"; perhaps reflecting a belief that these craft were really rather ungentlemanly methods of waging war. None were built.

A gaseous diffusion plant was built at Capenhurst

Capenhurst