.gif)

History of Poland (1569–1795)

Encyclopedia

The Nihil novi

act adopted by the Polish

Diet

in 1505 transferred all legislative power from the king

to the Diet. This event marked the beginning of the period known as "Nobles' Democracy" or "Nobles' Commonwealth" (Rzeczpospolita

szlachecka) when the state

was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility (szlachta

). The Lublin Union of 1569 constituted the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an influential player in European politics

and a vital cultural

entity. By the 18th century the nobles' democracy gradually declined into anarchy

, making the once powerful Commonwealth vulnerable to foreign influence. Eventually the country was partitioned by its neighbors

and erased from the map in 1795.

The death of Sigismund II Augustus

The death of Sigismund II Augustus

in 1572 was followed by a three-year interregnum

period during which adjustments were made to the constitutional system. The lower nobility was now included in the selection process, and the power of the monarch was further circumscribed in favor of the expanded noble class. Each king had to sign the so called Henrician Articles

, which were the basis of the political system of Poland, and pacta conventa

which were various personal obligations of the chosen king. From that point, the king was effectively a partner with the noble class and constantly supervised by a group of senators. Once the Jagiellons

disappeared from the scene, the fragile equilibrium of the Commonwealth government began to go awry. The constitutional reforms made the monarchy electoral in fact as well as name. As more and more power went to the noble electors, it also eroded from the government's center.

In its periodic opportunities to fill the throne, the szlachta

In its periodic opportunities to fill the throne, the szlachta

exhibited a preference for foreign candidates who would not found another strong dynasty

. This policy produced monarchs who were either totally ineffective or in constant debilitating conflict with the nobility. Furthermore, aside from notable exceptions such as the able Transylvania

n Stefan Batory

(1576–1586), the kings of alien origin were inclined to subordinate the interests of the Commonwealth to those of their own country and ruling house.

to elect the French prince Henry of Valois

as ruler. A marriage with Henry was to further legitimize Henry's rule but less than a year after his coronation, Henry fled Poland to succeed his brother Charles IX

as King of France.

ports: Gdańsk

controlling the Vistula

river trade and Riga

controlling Western Dvina trade. Both cities were among the largest in the country.

During the Livonian War

During the Livonian War

(1558–1582), between Ivan the Terrible of Russia and Stephen Báthory of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Pskov

was besieged by Polish forces. Poland failed to capture the city, but Batory, with his chancellor

Jan Zamojski, led the Polish army in a brilliant decisive campaign and forced Russia to return other territories and gained Livonia

and Polock. In 1582 the war ended with Commonwealth victory with the peace treaty in Jam Zapolski.

War of the Polish Succession (1587-1588)

Stephen Báthory planned a Christian

alliance against the Islam

ic Ottomans. He proposed an anti-Ottoman alliance with Russia, which he considered a necessary step for his anti-Ottoman crusade. However, Russia was on the way to the Time of Troubles

so he could not find a partner there. When Stephen Bathory died, there was a one year interregnum. Emperor Mathias's

brother Maximilian III tried to claim title of King of Poland, but was defeated at Byczyna

in 1588 and Sigismund III Vasa

succeeded Stephen Bathory.

The first few years of Sigismund's reign, until 1598 saw Poland and Sweden

The first few years of Sigismund's reign, until 1598 saw Poland and Sweden

united in a personal union that made the Baltic Sea an internal lake (the Polish–Swedish union). However, the rebellion in Sweden started the chain of events that would involve the Commonwealth in more than a century of warfare with Sweden.

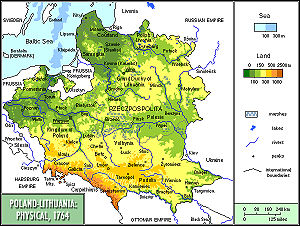

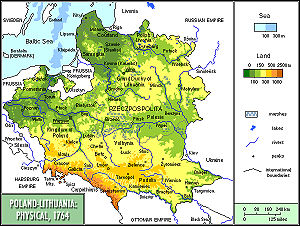

For 10 years between 1619 and 1629 the Commonwealth was at its greatest geographical extent in history. In 1619 the Russo-Polish Truce of Deulino

came into effect, whereby Russia conceded Commonwealth control over Smolensk

and several other border territories. In 1629 the Swedish-Polish Truce of Altmark

came into effect, whereby the Commonwealth conceded Swedish control over most of Livonia

, which the Swedes had invaded in 1626.

In the end, Sigismund III Vasa

failed to strengthen the Commonwealth or to solve its internal problems; instead he concentrated on a futile attempt to regain his former Swedish throne.

and later also Russia. In 1598 Sigismund tried to defeat Charles with a mixed army from Sweden and Poland but was defeated in the battle of Stångebro

. The war continued, punctuated by many ceasefires and broken peace treaties. On occasion, these campaigns brought Poland to a nearly complete conquest of Russia and the Baltic coast during the Time of Troubles

and False Dimitris

, had it not been for the military burden imposed by the ongoing rivalry on multiple borders: the Ottoman Empire

, the Swedes and the Russians.

was the thorn in the Ottoman plans of European conquest. Since the second half of the 16th century, Polish-Ottomans relations, never too friendly, were further worsened by the escalation of Cossacks-Tatars border warfare, which turned the entire border region between the Commonwealth and Ottoman Empire into a semi-permanent warzone

. A constant threat from Crimean Tatars

supported the appearance of Cossackdom.

In the 1595, magnate

s of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth intervened in the affairs of Moldavia

. This would start a series of conflicts that would soon spread to Transylvania

, Wallachia

and Hungary

, when the Commonwealth forces clashed with the forces backed by Ottoman Empire and occasionally Habsburgs, all competing for the domination over that region.

With the Commonwealth engaged on its northern and eastern borders with near constant conflicts against Sweden and Muscovy, its armies were spread thin. Finally, the southern wars culminated in the Polish defeat at the Battle of Cecora

in 1620. Eventually the Commonwealth was forced to renounce all claims to Moldavia, Transylvania, Wallachia and Hungary.

was neither overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nor Polish. This circumstance resulted from the federation with Lithuania, where ethnic Poles

were a distinct minority. In those days, to be Polish was much less an indication of ethnicity than of rank; it was a designation largely reserved for the landed noble class, which included members of Polish and non-Polish origin alike. Generally speaking, the ethnically non-Polish noble families of Lithuania adopted the Polish language

and culture. As a result, in the eastern territories of the kingdom a Polish aristocracy dominated over a peasantry whose great majority was neither Polish nor Catholic. Moreover, the decades of peace brought huge colonization efforts to Ukraine

, which heightened tensions between peasants, Jew

s and nobles. The tensions were aggravated by the conflicts between Orthodox

and Greek Catholic churches following the Union of Brest

and by several Cossack

uprisings. On the West and North, cities had big German

minorities, often of reformed belief. According to the Risāle-yi Tatar-i Leh (an account of the Lipka Tatars

written for Süleyman the Magnificent by an anonymous Polish Muslim

during a stay in Istanbul in 1557-8 on his way to Mecca) there were 100 Lipka Tatar settlements with mosques in Poland. In the year 1672, the Tatar subjects rose up in open rebellion against the Commonwealth.

, but never had any control over Russian territories. In the end, like his father, he failed to strengthen the Commonwealth or prevent the crippling events of The Deluge

or Khmelnytsky Uprising

, that devastated the Commonwealth in 1648.

In 1660 John Casimir would be forced to renounce his claims to the Swedish throne and acknowledge Swedish sovereignty over Livonia

and city of Riga

. He abdicated on 16 September 1668 and returned to France where he joined the Jesuit order and became an ordinary monk

. He died in 1672.

Khmelnytsky Uprising

This largest of all Cossack

This largest of all Cossack

s rebellions, led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky

, proved disastrous for the Commonwealth. In the end, the Commonwealth not only lost parts of its territory to Russia, but was weakened at the moment of invasion by Sweden.

(1618–1648), the following two decades would subject the nation to one of its worst trials ever. This colorful but ruinous interval, the stuff of legend and the popular historical novels of Nobel

laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz

, became known as the potop, or The Deluge

, for the magnitude and suddenness of its hardships. The emergency began when the Ukrainian Cossacks rose in revolt and declared an independent state based around Kiev

and allied with the Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman Empire. Their leader Bohdan Chmielnicki defeated two Polish armies in 1648 and 1651 and after the Cossacks concluded the Treaty of Pereyaslav

with Russia in 1654, Tsar Alexis overran the entire eastern part of Poland to Lvov. Taking advantage of Poland's preoccupation and weakness, Charles X of Sweden intervened. Most of the Polish nobility along with Frederick William of Brandenberg agreed to recognize him as king after he promised to drive out the Russians. However, the Swedish troops embarked on an orgy of looting and destruction, which caused the Polish populace to rise up in revolt. Nonetheless, the Swedes overran the remainder of Poland except for Lvov and Danzig. Poland-Lithuania rallied to recover most of its losses from the Swedes. In exchange for breaking the alliance with Sweden, the ruler of Ducal Prussia was released from his vassalage and became a de facto independent sovereign, while much of the Polish Protestant nobility went over to the side of the Swedes. Under hetman Stefan Czarniecki

, the Poles and Lithuanians had driven the Swedes from their territory by 1657. The armies of Frederick William of Brandenberg intervened and were also defeated. Frederick William's rule over East Prussia was recognized, although Poland retained nominal authority over the duchy until 1773.

Further complicated by dissenting nobles and wars with the Ottoman Turks

, the thirteen-year struggle over control of Ukraine ended when that country reentered into union with Poland (1658) and the Russians were defeated in 1660-1662. However Russia still refused to give up its claims to the Ukraine, and when peace was concluded in 1667, it annexed the right bank of the Dnepr River. Kiev was also leased to Russia for two years, but ultimately never returned and eventually Poland recognized Russian control of the city.

Despite the improbable survival of the Commonwealth in the face of the potop, one of the most dramatic instances of the Poles' knack for prevailing in adversity, the episode inflicted irremediable damage and contributed heavily to the ultimate demise of the state. Held responsible for the greatest disaster in Polish history, John Casimir abdicated in 1668. The population of the Commonwealth had been reduced a staggering 45% (a greater percentage than in World War II) by military casualties, slave raids, plague epidemics, and mass murders of civilians. Most of Poland's cities were reduced to rubble, and the nation's economic base decimated. The war had been paid for by large-scale minting of worthless currency, causing runaway inflation. Religious feelings had also been inflamed by the conflict, ending tolerance of non-Catholic beliefs. Henceforth, the Commonwealth would be on the strategic defensive facing hostile neighbors. Not until the Polish-Soviet War

of the early 20th century would Poland compete with Russia as a military equal.

(1598–1599), Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629) and the Northern Wars

(1655–1660)).

After the Treaty of Andrusovo in 1667 and the Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686

, the Commonwealth lost left-bank Ukraine

to Russia.

Polish culture and the Greek Catholic Church

gradually advanced and by the 18th century, the population of Ducal Prussia was a mixture of Catholics and Protestants and used both the German

and Polish languages. The rest of Poland and most of Lithuania remained firmly Roman Catholic, while Ukraine and some parts of Lithuania (i.e., Belarus

) were Greek Orthodox. The society was split into an upper stratum (8% nobles, 1%priests), townspeople (6%), Jews (10%), Ormians/Tatars (2%), and peasants (73%Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians and other). In the year 1772 out of the 12mln inhabitants there were: 43% Roman Catholics, 33% Greek Catholics, 10% Orthodox, 9% Jews, 4% Protestants, 1% Muslims.

Following the abdication of King John Casimir Vasa and the end of The Deluge

Following the abdication of King John Casimir Vasa and the end of The Deluge

, the Polish nobility (szlachta

) elected Michael Korybut Wisniowiecki as king, believing he would further the interests of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was the first monarch of Polish origin since the last of Jagiellonian dynasty, Sigismund II Augustus

, died in 1572. Michael was a son of a successful but controversial military commander Jeremi Wiśniowiecki

, known for his actions during the Khmelnytsky Uprising

led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky

.

His reign was less than successful, and the nobility was not satisfied with the House of Vasa

's dynastic policies. Despite his father's military fame, Michael lost a war against the Ottoman Empire, with Turk

s occupying Podolia

and most of Ukraine in 1672-1673. He was unable to cope with his responsibilities and with the different quarreling factions within Poland.

John III Sobieski's most famous achievement was to deal a crushing defeat to the Ottoman Empire in 1683 at the Battle of Vienna

John III Sobieski's most famous achievement was to deal a crushing defeat to the Ottoman Empire in 1683 at the Battle of Vienna

, which marked the final turning point in a 250-year struggle between the forces of Christian Europe and the Islamic Ottoman Empire. Over the 16 years following the battle (the so-called Great Turkish War

), the Turks would be permanently driven south of the Danube River, never to threaten central Europe again. When the Holy Alliance concluded peace with the Ottomans in 1699, Poland recovered Podolia and Ukraine. On other fronts, John III was less successful, including agreements with France and Sweden in a failed attempt to regain the Duchy of Prussia. Meanwhile, Kiev had been leased to the Russians for two years after 1667 and never returned. Poland formally relinquished all claims to the city in 1686.

subject to the manipulations of Russia, Sweden, the Kingdom of Prussia

, France and Austria

. Poland's weakness was exacerbated by an unworkable constitution which allowed each noble or gentry representative in the Sejm to use his vetoing power to stop further parliamentary proceedings for the given session. This greatly weakened the central authority of Poland and paved the way for its destruction.

Most accounts of Polish history show the two centuries after the end of the Jagiellon dynasty

as a time of decline leading to foreign domination.

Before another hundred years have elapsed, Poland-Lithuania had virtually ceased to function as a coherent and genuinely independent state. The commonwealth's last martial triumph occurred in 1683 when King John Sobieski drove the Turks from the gates of Vienna

with a heavy cavalry charge. Poland's important role in aiding the European alliance to roll back the Ottoman Empire was rewarded with some territory in Podole

by the Treaty of Karlowicz (1699). Nonetheless, this isolated success did little to mask the internal weakness and paralysis of the Polish–Lithuanian political system. For the next quarter century, Poland was often a pawn in Russia's campaigns against other powers. When John III died in 1697, 18 candidates vied for the throne, which ultimately went to Frederick Augustus of Saxony, who then converted to Catholicism. Ruling as Augustus II, his reign presented the opportunity to unite Saxony (an industrialized area) with Poland, a country rich in mineral resources. However, the king lacked any skill in foreign policy and so became entangled in a war with Sweden. His allies the Russians and Danes were repelled by Charles XII of Sweden, beginning the Great Northern War

. Charles installed a puppet ruler in Poland and marched on Saxony, compelling Augustus to give up his crown and making Poland into a base for the Swedish army. Poland was again devastated by the armies of Sweden, Russia, and Saxony. Its major cities were destroyed and a third of the population killed by the war and a plague outbreak in 1709. The Swedes finally withdrew from Poland and invaded Ukraine, where they were defeated by the Russians at Poltava. Augustus was able to reclaim his throne with Russian support, but Peter the Great decided to annex Livonia in 1710. He also suppressed the Cossacks, who had been in revolt against Poland since 1699. Later on, the tsar frustrated an attempt by Prussia to regain territory from Poland (despite Augustus' approval of this). After the Great Northern War, Poland became an effective protectorate of Russia for the rest of the 18th century.

In the eighteenth century, the powers of the monarchy and the central administration became purely formal. Kings were denied permission to provide for the elementary requirements of defense and finance, and aristocratic clans made treaties directly with foreign sovereigns. Attempts at reform were stymied by the determination of the szlachta to preserve their "golden freedoms" most notably the liberum veto

. Because of the chaos sown by the veto provision, under Augustus III (1733–63) only one of thirteen Sejm sessions ran to an orderly adjournment.

Unlike Spain and Sweden, great power

s that were allowed to settle peacefully into secondary status at the periphery of Europe at the end of their time of glory, Poland endured its decline at the strategic crossroads of the continent. Lacking central leadership and impotent in foreign relations, Poland-Lithuania became a chattel of the ambitious kingdoms that surrounded it, an immense but feeble buffer state

. During the reign of Peter the Great

(1682–1725), the commonwealth fell under the dominance of Russia, and by the middle of the eighteenth century Poland-Lithuania had been made a virtual protectorate of its eastern neighbor, retaining only the theoretical right to self-rule.

The War of the Polish Succession

was fought from 1733–1735.

of Saxony

, was an over-ambitious ruler. He defeated his biggest rival, François Louis, Prince of Conti

, supported by France, and Sobieski's son, Jakub. To ensure his success for the crown of Poland he decided to convert to Roman Catholicism from Lutheranism

. Augustus hoped to make the Polish throne hereditary within his family, and to use his resources as Elector of Saxony to impose some order on the chaotic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. However, he was soon distracted from his internal reform projects by the possibility of external conquest. He allied with Denmark and Russia, provoking war with Sweden. After the former were defeated, the latter's king Charles XII marched from Livonia into Poland, using it as his base of operations. Installing a puppet ruler in Warsaw, he occupied Saxony and drove Augustus II from the throne. Poland, which had only recently returned to its 1650 population level, was once again completely razed to the ground by the armies of Sweden, Saxony, and Russia. Two million people died as a result of the war and disease epidemics. Cities were reduced to rubble, and cultural losses were immense. The Swedish armies eventually left Poland and turned east into Russia. Augustus II regained the throne with Russian backing, but the latter proceeded to annex Livonia after driving the Swedes from it. Meanwhile, a Cossack revolt that had begun in 1699 was suppressed by the Russians, and Tsar Peter the Great declared Russia to be the guardian of the Polish Republic's territorial integrity. This effectively meant that Poland became a Russian protectorate for the remainder of the 18th century.

, inherited Saxony after his father's death, and was elected king of Poland by a minority sejm with the support of Russian troops. August III was uninterested in the affairs of his Polish dominion, which he viewed mostly as a source of funds and resources for strengthening his power in Saxony. During his 30-year reign, he spent less than 3 years in Poland, delegating most of his powers and responsibilities to Count Heinrich von Brühl

. Thirty years of August III's uninterested reign festered the political anarchy

and further weakened the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, while neighboring Prussia

, Austria and Russia finalized plans for the partitions of Poland

.

Partitions:

During the reign of Empress Catherine the Great (1762–1796), Russia intensified its manipulation in Polish affairs. The Kingdom of Prussia

and Austria, the other powers surrounding the republic, also took advantage of internal religious and political bickering to divide up the country in three partition

stages. After two partitions, the third one in 1795 eventually wiped Poland-Lithuania from the map of Europe.

In 1764 Catherine dictated the election of her former favorite and lover, Stanisław August Poniatowski, as king of Poland-Lithuania. Confounding expectations that he would be an obedient servant of his mistress, Stanislaw August encouraged the modernization of his realm's ramshackle political system and achieved a temporary moratorium on use of the individual veto in the Sejm (1764–1766). This turnabout threatened to renew the strength of the monarchy and brought displeasure in the foreign capitals that preferred an inert, pliable Poland. Catherine, being among the most displeased by Poniatowski's independence, encouraged religious dissension in Poland-Lithuania's substantial Eastern Orthodox population, which earlier in the eighteenth century had lost the rights enjoyed during the Jagiellon Dynasty

In 1764 Catherine dictated the election of her former favorite and lover, Stanisław August Poniatowski, as king of Poland-Lithuania. Confounding expectations that he would be an obedient servant of his mistress, Stanislaw August encouraged the modernization of his realm's ramshackle political system and achieved a temporary moratorium on use of the individual veto in the Sejm (1764–1766). This turnabout threatened to renew the strength of the monarchy and brought displeasure in the foreign capitals that preferred an inert, pliable Poland. Catherine, being among the most displeased by Poniatowski's independence, encouraged religious dissension in Poland-Lithuania's substantial Eastern Orthodox population, which earlier in the eighteenth century had lost the rights enjoyed during the Jagiellon Dynasty

.

Under heavy Russian pressure, the Sejm introduced Orthodox and Protestant equality in 1767. Through the Polish nobles that Russia controlled and Russian Minister to Warsaw Prince Nikolai Repnin, Czarina Catherine the Great forced a constitution, which undid the reforms of 1764 under Stanislaw II, on Poland in 1767. The liberum veto and all the old abuses of the last one and a quarter centuries were guaranteed as unalterable parts of this new constitution.

Poland was compelled to sign Treaty of Guarantee with Russia, where Catherine was imposed as protector

of Polish political system. After that Poland became de facto a Russian protectorate

. The real power in Poland lay with the Russian ambassadors

, and the Polish king became only an executor of their will.

This action provoked a Catholic uprising by the Confederation of Bar, a league of Polish nobles that fought with Russian intervention until 1772 to revoke Catherine's mandate.

The defeat of the Confederation of Bar again left Poland exposed to the ambitions of its neighbors. Although Catherine initially opposed partition, Frederick the Great of Prussia profited from Austria's threatening military position to the southwest by pressing a long-standing proposal to carve territory from the commonwealth. Catherine, persuaded that Russia did not have the resources to continue its unilateral domination of Poland, agreed. In 1772 Russia, Prussia, and Austria forced terms of partition upon the helpless commonwealth under the pretext of restoring order in the anarchic conditions of the country.

and George Washington

. At the same time, Polish intellectuals discussed Enlightenment philosophers such as Montesquieu

and Rousseau. During the period of Polish Enlightenment, the concept of democratic institutions for all classes was accepted in Polish society. Education reform included establishment of the first ministry of education in Europe (the Komisja Edukacji Narodowej

). Taxation and the army underwent thorough reform, and government again was centralized in the Permanent Council. Landholders emancipated large numbers of peasants, although there was no official government decree. Polish cities, in decline for many decades, were revived by the influence of the Industrial Revolution

, especially in mining and textiles.

Stanislaw August's process of renovation reached its climax when, after three years of intense debate, the "Four Years' Sejm" produced the Constitution of May 3, 1791

, which historian Norman Davies

calls "the first constitution of its kind in Europe". Conceived in the liberal spirit of the contemporaneous document in the United States, the constitution recast Poland-Lithuania as a hereditary monarchy and abolished many of the eccentricities and antiquated features of the old system. The new constitution abolished the individual veto in parliament; provided a separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government; and established "people's sovereignty" (for the noble and bourgeois classes). Although never fully implemented, the Constitution of May 3rd gained an honored position in the Polish political heritage; tradition marks the anniversary of its passage as the country's most important civic holiday.

Passage of the constitution alarmed nobles who would lose considerable stature under the new order. In autocratic states such as Russia, the democratic ideals of the constitution also threatened the existing order, and the prospect of Polish recovery threatened to end domination of Polish affairs by its neighbors. In 1792, Polish factions formed the Confederation of Targowica and appealed for Russian assistance in restoring the status quo. Catherine was happy to use this opportunity; enlisting Prussian support, she invaded Poland under the pretext of defending Poland's ancient liberties. The irresolute Stanislaw August capitulated, defecting to the Targowica faction. Arguing that Poland had fallen prey to the radical Jacobinism then at high tide in France, Russia and Prussia abrogated the Constitution of May 3, 1791

Passage of the constitution alarmed nobles who would lose considerable stature under the new order. In autocratic states such as Russia, the democratic ideals of the constitution also threatened the existing order, and the prospect of Polish recovery threatened to end domination of Polish affairs by its neighbors. In 1792, Polish factions formed the Confederation of Targowica and appealed for Russian assistance in restoring the status quo. Catherine was happy to use this opportunity; enlisting Prussian support, she invaded Poland under the pretext of defending Poland's ancient liberties. The irresolute Stanislaw August capitulated, defecting to the Targowica faction. Arguing that Poland had fallen prey to the radical Jacobinism then at high tide in France, Russia and Prussia abrogated the Constitution of May 3, 1791

, carried out a second partition of Poland in 1793, and placed the remainder of the country under occupation by Russian troops.

The second partition was far more injurious than the first. Russia received a vast area of eastern Poland, extending southward from its gains in the first partition nearly to the Black Sea

. To the west, Prussia received an area known as South Prussia, nearly twice the size of its first-partition gains along the Baltic, as well as the port of Gdańsk. Thus, Poland's neighbors reduced the commonwealth to a rump state and plainly signaled their designs to abolish it altogether at their convenience.

In a gesture of defiance, a general Polish revolt broke out in 1794 under the leadership of Tadeusz Kościuszko

In a gesture of defiance, a general Polish revolt broke out in 1794 under the leadership of Tadeusz Kościuszko

(Kościuszko Uprising

), a military officer who had rendered notable service in the American Revolution

. Kosciuszko's ragtag insurgent armies won some initial successes, but they eventually fell before the superior forces of Russian General Alexander Suvorov

. In the wake of the insurrection of 1794, Russia, Prussia, and Austria carried out the third and final partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1795, erasing the Commonwealth of Two Nations from the map and pledging never to let it return.

Much of Europe condemned the dismemberment as an international crime without historical parallel. Amid the distractions of the French Revolution

and its attendant wars, however, no state actively opposed the annexations. In the long term, the dissolution of Poland-Lithuania upset the traditional European balance of power, dramatically magnifying the influence of Russia and paving the way for the Germany that would emerge in the nineteenth century with Prussia at its core. For the Poles, the third partition began a period of continuous foreign rule that would endure well over a century.

Nihil novi

Nihil novi nisi commune consensu is the original Latin title of a 1505 act adopted by the Polish Sejm , meeting in the royal castle at Radom.-History:...

act adopted by the Polish

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

Diet

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

in 1505 transferred all legislative power from the king

Monarch

A monarch is the person who heads a monarchy. This is a form of government in which a state or polity is ruled or controlled by an individual who typically inherits the throne by birth and occasionally rules for life or until abdication...

to the Diet. This event marked the beginning of the period known as "Nobles' Democracy" or "Nobles' Commonwealth" (Rzeczpospolita

Rzeczpospolita

Rzeczpospolita is a traditional name of the Polish State, usually referred to as Rzeczpospolita Polska . It comes from the words: "rzecz" and "pospolita" , literally, a "common thing". It comes from latin word "respublica", meaning simply "republic"...

szlachecka) when the state

Sovereign state

A sovereign state, or simply, state, is a state with a defined territory on which it exercises internal and external sovereignty, a permanent population, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. It is also normally understood to be a state which is neither...

was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility (szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

). The Lublin Union of 1569 constituted the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an influential player in European politics

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

and a vital cultural

Culture

Culture is a term that has many different inter-related meanings. For example, in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions...

entity. By the 18th century the nobles' democracy gradually declined into anarchy

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

, making the once powerful Commonwealth vulnerable to foreign influence. Eventually the country was partitioned by its neighbors

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

and erased from the map in 1795.

Founding of the elective monarchy

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus I was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the only son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548...

in 1572 was followed by a three-year interregnum

Interregnum

An interregnum is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order...

period during which adjustments were made to the constitutional system. The lower nobility was now included in the selection process, and the power of the monarch was further circumscribed in favor of the expanded noble class. Each king had to sign the so called Henrician Articles

Henrician Articles

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles were a permanent contract that stated the fundamental principles of governance and constitutional law in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the form of 21 Articles written and adopted by the nobility in 1573 at the town of Kamień, near Warsaw,...

, which were the basis of the political system of Poland, and pacta conventa

Pacta conventa (Poland)

Pacta conventa was a contractual agreement, from 1573 to 1764 entered into between the "Polish nation" and a newly-elected king upon his "free election" to the throne.The pacta conventa affirmed the king-elect's pledge to respect the laws of the...

which were various personal obligations of the chosen king. From that point, the king was effectively a partner with the noble class and constantly supervised by a group of senators. Once the Jagiellons

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty was a royal dynasty originating from the Lithuanian House of Gediminas dynasty that reigned in Central European countries between the 14th and 16th century...

disappeared from the scene, the fragile equilibrium of the Commonwealth government began to go awry. The constitutional reforms made the monarchy electoral in fact as well as name. As more and more power went to the noble electors, it also eroded from the government's center.

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

exhibited a preference for foreign candidates who would not found another strong dynasty

Dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers considered members of the same family. Historians traditionally consider many sovereign states' history within a framework of successive dynasties, e.g., China, Ancient Egypt and the Persian Empire...

. This policy produced monarchs who were either totally ineffective or in constant debilitating conflict with the nobility. Furthermore, aside from notable exceptions such as the able Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

n Stefan Batory

Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory may refer to several noblemen of Hungarian descent:* Stephen III Báthory , Palatine of Hungary* Stephen V Báthory , judge of the Royal Court and Prince of Transylvania...

(1576–1586), the kings of alien origin were inclined to subordinate the interests of the Commonwealth to those of their own country and ruling house.

Henry of Valois (1573–1574)

In April 1573, Sigismund's sister Anna, the sole heir to the crown, convinced the SejmSejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

to elect the French prince Henry of Valois

Henry III of France

Henry III was King of France from 1574 to 1589. As Henry of Valois, he was the first elected monarch of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with the dual titles of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1573 to 1575.-Childhood:Henry was born at the Royal Château de Fontainebleau,...

as ruler. A marriage with Henry was to further legitimize Henry's rule but less than a year after his coronation, Henry fled Poland to succeed his brother Charles IX

Charles IX of France

Charles IX was King of France, ruling from 1560 until his death. His reign was dominated by the Wars of Religion. He is best known as king at the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre.-Childhood:...

as King of France.

Stefan Báthory (1576–1586)

Poland defeated Russia's Ivan the Terrible and retrieved most of the lost provinces, including Livland. At the end of his reign, Poland ruled two main Baltic SeaBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

ports: Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

controlling the Vistula

Vistula

The Vistula is the longest and the most important river in Poland, at 1,047 km in length. The watershed area of the Vistula is , of which lies within Poland ....

river trade and Riga

Riga

Riga is the capital and largest city of Latvia. With 702,891 inhabitants Riga is the largest city of the Baltic states, one of the largest cities in Northern Europe and home to more than one third of Latvia's population. The city is an important seaport and a major industrial, commercial,...

controlling Western Dvina trade. Both cities were among the largest in the country.

Livonian War

The Livonian War was fought for control of Old Livonia in the territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia when the Tsardom of Russia faced a varying coalition of Denmark–Norway, the Kingdom of Sweden, the Union of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland.During the period 1558–1578,...

(1558–1582), between Ivan the Terrible of Russia and Stephen Báthory of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Pskov

Pskov

Pskov is an ancient city and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, Russia, located in the northwest of Russia about east from the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population: -Early history:...

was besieged by Polish forces. Poland failed to capture the city, but Batory, with his chancellor

Chancellor

Chancellor is the title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the Cancellarii of Roman courts of justice—ushers who sat at the cancelli or lattice work screens of a basilica or law court, which separated the judge and counsel from the...

Jan Zamojski, led the Polish army in a brilliant decisive campaign and forced Russia to return other territories and gained Livonia

Livonia

Livonia is a historic region along the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It was once the land of the Finnic Livonians inhabiting the principal ancient Livonian County Metsepole with its center at Turaida...

and Polock. In 1582 the war ended with Commonwealth victory with the peace treaty in Jam Zapolski.

War of the Polish Succession (1587-1588)War of the Polish Succession (1587-1588)The War of the Polish Succession or the Hapsburg-Polish War took place from 1587 to 1588 over the election of monarch after the death of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Stephen Báthory. The war was fought between factions of Sigismund III Vasa and Maximilian III, with Sigismund...

Stephen Báthory planned a ChristianChristian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

alliance against the Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

ic Ottomans. He proposed an anti-Ottoman alliance with Russia, which he considered a necessary step for his anti-Ottoman crusade. However, Russia was on the way to the Time of Troubles

Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles was a period of Russian history comprising the years of interregnum between the death of the last Russian Tsar of the Rurik Dynasty, Feodor Ivanovich, in 1598, and the establishment of the Romanov Dynasty in 1613. In 1601-1603, Russia suffered a famine that killed one-third...

so he could not find a partner there. When Stephen Bathory died, there was a one year interregnum. Emperor Mathias's

Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor

Matthias of Austria was Holy Roman Emperor from 1612, King of Hungary and Croatia from 1608 and King of Bohemia from 1611...

brother Maximilian III tried to claim title of King of Poland, but was defeated at Byczyna

Battle of Byczyna

The Battle of Byczyna or Battle of Pitschen was the deciding battle of the 1587–1588 War of the Polish Succession, which erupted after two rival candidates were elected to the Polish throne...

in 1588 and Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, a monarch of the united Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1587 to 1632, and King of Sweden from 1592 until he was deposed in 1599...

succeeded Stephen Bathory.

Zygmunt III Vasa (1587–1632)

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

united in a personal union that made the Baltic Sea an internal lake (the Polish–Swedish union). However, the rebellion in Sweden started the chain of events that would involve the Commonwealth in more than a century of warfare with Sweden.

For 10 years between 1619 and 1629 the Commonwealth was at its greatest geographical extent in history. In 1619 the Russo-Polish Truce of Deulino

Truce of Deulino

Truce of Deulino was signed on 11 December 1618 and took effect on 4 January 1619. It concluded the Polish–Muscovite War between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia....

came into effect, whereby Russia conceded Commonwealth control over Smolensk

Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River. Situated west-southwest of Moscow, this walled city was destroyed several times throughout its long history since it was on the invasion routes of both Napoleon and Hitler. Today, Smolensk...

and several other border territories. In 1629 the Swedish-Polish Truce of Altmark

Truce of Altmark

The six-year Truce of Altmark was signed on 25 September 1629 at the Altmark , near Danzig by Sweden and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during Thirty Years' War, ending the Polish–Swedish War ....

came into effect, whereby the Commonwealth conceded Swedish control over most of Livonia

Livonia

Livonia is a historic region along the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It was once the land of the Finnic Livonians inhabiting the principal ancient Livonian County Metsepole with its center at Turaida...

, which the Swedes had invaded in 1626.

In the end, Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, a monarch of the united Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1587 to 1632, and King of Sweden from 1592 until he was deposed in 1599...

failed to strengthen the Commonwealth or to solve its internal problems; instead he concentrated on a futile attempt to regain his former Swedish throne.

Polish-Sweden-Muscovy Wars

Sigismund desire to reclaim the throne drove Sigismund into prolonged military adventures waged against his native Sweden under Charles IXCharles IX of Sweden

Charles IX of Sweden also Carl, was King of Sweden from 1604 until his death. He was the youngest son of King Gustav I of Sweden and his second wife, Margaret Leijonhufvud, brother of Eric XIV and John III of Sweden, and uncle of Sigismund III Vasa king of both Sweden and Poland...

and later also Russia. In 1598 Sigismund tried to defeat Charles with a mixed army from Sweden and Poland but was defeated in the battle of Stångebro

Battle of Stångebro

The Battle of Stångebro or Battle of Linköping took place at Linköping, Sweden on September 25, 1598, and effectively ended the personal union between Sweden and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, that had only existed since 1592...

. The war continued, punctuated by many ceasefires and broken peace treaties. On occasion, these campaigns brought Poland to a nearly complete conquest of Russia and the Baltic coast during the Time of Troubles

Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles was a period of Russian history comprising the years of interregnum between the death of the last Russian Tsar of the Rurik Dynasty, Feodor Ivanovich, in 1598, and the establishment of the Romanov Dynasty in 1613. In 1601-1603, Russia suffered a famine that killed one-third...

and False Dimitris

False Dmitriy I

False Dmitriy I was the Tsar of Russia from 21 July 1605 until his death on 17 May 1606 under the name of Dimitriy Ioannovich . He is sometimes referred to under the usurped title of Dmitriy II...

, had it not been for the military burden imposed by the ongoing rivalry on multiple borders: the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, the Swedes and the Russians.

The southern wars

Commonwealth-Ottomans relations were never too warm, as the Commonwealth viewed itself as the 'bulwark of the Christendom' and together with Habsburgs and Republic of VeniceRepublic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

was the thorn in the Ottoman plans of European conquest. Since the second half of the 16th century, Polish-Ottomans relations, never too friendly, were further worsened by the escalation of Cossacks-Tatars border warfare, which turned the entire border region between the Commonwealth and Ottoman Empire into a semi-permanent warzone

Wild Fields

The Wild Field or the Wilderness is a historical term used in the Polish–Lithuanian documents of the 16th and 18th centuries referring to forest steppes and steppes of the Black sea and Azov sea regions...

. A constant threat from Crimean Tatars

Crimean Khanate

Crimean Khanate, or Khanate of Crimea , was a state ruled by Crimean Tatars from 1441 to 1783. Its native name was . Its khans were the patrilineal descendants of Toqa Temür, the thirteenth son of Jochi and grandson of Genghis Khan...

supported the appearance of Cossackdom.

In the 1595, magnate

Magnate

Magnate, from the Late Latin magnas, a great man, itself from Latin magnus 'great', designates a noble or other man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or other qualities...

s of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth intervened in the affairs of Moldavia

Moldavia

Moldavia is a geographic and historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester river...

. This would start a series of conflicts that would soon spread to Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

, Wallachia

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians...

and Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, when the Commonwealth forces clashed with the forces backed by Ottoman Empire and occasionally Habsburgs, all competing for the domination over that region.

With the Commonwealth engaged on its northern and eastern borders with near constant conflicts against Sweden and Muscovy, its armies were spread thin. Finally, the southern wars culminated in the Polish defeat at the Battle of Cecora

Battle of Tutora (1620)

The Battle of Ţuţora was a battle between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Ottoman forces , fought from 17 September to 7 October 1620 in Moldavia, near the Prut River.- Prelude :Because of the failure of Commonwealth diplomatic mission to Constantinople, and violations of the Treaty of...

in 1620. Eventually the Commonwealth was forced to renounce all claims to Moldavia, Transylvania, Wallachia and Hungary.

Religious and social tensions

The population of Poland-LithuaniaPoland-Lithuania

Poland–Lithuania can refer to:* Polish–Lithuanian union from 1385 until 1569* Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 until 1795See also: Polish-Lithuanian...

was neither overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nor Polish. This circumstance resulted from the federation with Lithuania, where ethnic Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

were a distinct minority. In those days, to be Polish was much less an indication of ethnicity than of rank; it was a designation largely reserved for the landed noble class, which included members of Polish and non-Polish origin alike. Generally speaking, the ethnically non-Polish noble families of Lithuania adopted the Polish language

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

and culture. As a result, in the eastern territories of the kingdom a Polish aristocracy dominated over a peasantry whose great majority was neither Polish nor Catholic. Moreover, the decades of peace brought huge colonization efforts to Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

, which heightened tensions between peasants, Jew

History of the Jews in Poland

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back over a millennium. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world. Poland was the centre of Jewish culture thanks to a long period of statutory religious tolerance and social autonomy. This ended with the...

s and nobles. The tensions were aggravated by the conflicts between Orthodox

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

and Greek Catholic churches following the Union of Brest

Union of Brest

Union of Brest or Union of Brześć refers to the 1595-1596 decision of the Church of Rus', the "Metropolia of Kiev-Halych and all Rus'", to break relations with the Patriarch of Constantinople and place themselves under the Pope of Rome. At the time, this church included most Ukrainians and...

and by several Cossack

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

uprisings. On the West and North, cities had big German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

minorities, often of reformed belief. According to the Risāle-yi Tatar-i Leh (an account of the Lipka Tatars

Lipka Tatars

The Lipka Tatars are a group of Tatars who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of 14th century. The first settlers tried to preserve their shamanistic religion and sought asylum amongst the non-Christian Lithuanians...

written for Süleyman the Magnificent by an anonymous Polish Muslim

Islam in Poland

The first ever written account of Poland was recorded by the Muslim Caliphate of Córdoba's 10th-century envoy, Ibrahim ibn Jakub. A continuous presence of Islam in Poland began in the 14th century. From this time it was primarily associated with the Tatars, many of whom settled in the...

during a stay in Istanbul in 1557-8 on his way to Mecca) there were 100 Lipka Tatar settlements with mosques in Poland. In the year 1672, the Tatar subjects rose up in open rebellion against the Commonwealth.

Władysław IV Vasa (1632–1648)

Władysław tried to achieve many military goals, including conquest of Russia, Sweden and Turkey. His reign is that of many small victories, few of them bringing anything worthwhile to the Commonwealth. For a time, he was elected a tsarTsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

, but never had any control over Russian territories. In the end, like his father, he failed to strengthen the Commonwealth or prevent the crippling events of The Deluge

The Deluge (Polish history)

The term Deluge denotes a series of mid-17th century campaigns in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In a wider sense it applies to the period between the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648 and the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, thus comprising the Polish–Lithuanian theaters of the Russo-Polish and...

or Khmelnytsky Uprising

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, was a Cossack rebellion in the Ukraine between the years 1648–1657 which turned into a Ukrainian war of liberation from Poland...

, that devastated the Commonwealth in 1648.

Jan Kazimierz Vasa (1648–1668)

The reign of the last of Vasas in the Commonwealth would be dominated by the culmination in the war with Sweden, groundwork for which was laid down by the two previous Vasa kings of the Commonwealth.In 1660 John Casimir would be forced to renounce his claims to the Swedish throne and acknowledge Swedish sovereignty over Livonia

Livonia

Livonia is a historic region along the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It was once the land of the Finnic Livonians inhabiting the principal ancient Livonian County Metsepole with its center at Turaida...

and city of Riga

Riga

Riga is the capital and largest city of Latvia. With 702,891 inhabitants Riga is the largest city of the Baltic states, one of the largest cities in Northern Europe and home to more than one third of Latvia's population. The city is an important seaport and a major industrial, commercial,...

. He abdicated on 16 September 1668 and returned to France where he joined the Jesuit order and became an ordinary monk

Monk

A monk is a person who practices religious asceticism, living either alone or with any number of monks, while always maintaining some degree of physical separation from those not sharing the same purpose...

. He died in 1672.

Khmelnytsky UprisingKhmelnytsky UprisingThe Khmelnytsky Uprising, was a Cossack rebellion in the Ukraine between the years 1648–1657 which turned into a Ukrainian war of liberation from Poland...

, 1648–1654

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

s rebellions, led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

, proved disastrous for the Commonwealth. In the end, the Commonwealth not only lost parts of its territory to Russia, but was weakened at the moment of invasion by Sweden.

The Deluge, (1648–1667)

Although Poland-Lithuania was unaffected by the Thirty Years' WarThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

(1618–1648), the following two decades would subject the nation to one of its worst trials ever. This colorful but ruinous interval, the stuff of legend and the popular historical novels of Nobel

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz was a Polish journalist and Nobel Prize-winning novelist. A Polish szlachcic of the Oszyk coat of arms, he was one of the most popular Polish writers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1905 for his...

, became known as the potop, or The Deluge

The Deluge (Polish history)

The term Deluge denotes a series of mid-17th century campaigns in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In a wider sense it applies to the period between the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648 and the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, thus comprising the Polish–Lithuanian theaters of the Russo-Polish and...

, for the magnitude and suddenness of its hardships. The emergency began when the Ukrainian Cossacks rose in revolt and declared an independent state based around Kiev

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

and allied with the Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman Empire. Their leader Bohdan Chmielnicki defeated two Polish armies in 1648 and 1651 and after the Cossacks concluded the Treaty of Pereyaslav

Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Treaty of Pereyaslav is known in history more as the Council of Pereiaslav.Council of Pereyalslav was a meeting between the representative of the Russian Tsar, Prince Vasili Baturlin who presented a royal decree, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky as the leader of Cossack Hetmanate. During the council...

with Russia in 1654, Tsar Alexis overran the entire eastern part of Poland to Lvov. Taking advantage of Poland's preoccupation and weakness, Charles X of Sweden intervened. Most of the Polish nobility along with Frederick William of Brandenberg agreed to recognize him as king after he promised to drive out the Russians. However, the Swedish troops embarked on an orgy of looting and destruction, which caused the Polish populace to rise up in revolt. Nonetheless, the Swedes overran the remainder of Poland except for Lvov and Danzig. Poland-Lithuania rallied to recover most of its losses from the Swedes. In exchange for breaking the alliance with Sweden, the ruler of Ducal Prussia was released from his vassalage and became a de facto independent sovereign, while much of the Polish Protestant nobility went over to the side of the Swedes. Under hetman Stefan Czarniecki

Stefan Czarniecki

Stefan Czarniecki or Stefan Łodzia de Czarnca Czarniecki Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth general and nobleman. Field Hetman of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom. He was a military commander, regarded as a Polish national hero...

, the Poles and Lithuanians had driven the Swedes from their territory by 1657. The armies of Frederick William of Brandenberg intervened and were also defeated. Frederick William's rule over East Prussia was recognized, although Poland retained nominal authority over the duchy until 1773.

Further complicated by dissenting nobles and wars with the Ottoman Turks

Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War refers to a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and contemporary European powers, then joined into a Holy League, during the second half of the 17th century.-1667–1683:...

, the thirteen-year struggle over control of Ukraine ended when that country reentered into union with Poland (1658) and the Russians were defeated in 1660-1662. However Russia still refused to give up its claims to the Ukraine, and when peace was concluded in 1667, it annexed the right bank of the Dnepr River. Kiev was also leased to Russia for two years, but ultimately never returned and eventually Poland recognized Russian control of the city.

Despite the improbable survival of the Commonwealth in the face of the potop, one of the most dramatic instances of the Poles' knack for prevailing in adversity, the episode inflicted irremediable damage and contributed heavily to the ultimate demise of the state. Held responsible for the greatest disaster in Polish history, John Casimir abdicated in 1668. The population of the Commonwealth had been reduced a staggering 45% (a greater percentage than in World War II) by military casualties, slave raids, plague epidemics, and mass murders of civilians. Most of Poland's cities were reduced to rubble, and the nation's economic base decimated. The war had been paid for by large-scale minting of worthless currency, causing runaway inflation. Religious feelings had also been inflamed by the conflict, ending tolerance of non-Catholic beliefs. Henceforth, the Commonwealth would be on the strategic defensive facing hostile neighbors. Not until the Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic—four states in post–World War I Europe...

of the early 20th century would Poland compete with Russia as a military equal.

Commonwealth after the Deluge

In the Treaty of Oliwa in 1660, John II of Poland finally renounced his claims to the Swedish Crown, which ended the feud between Sweden and the Commonwealth and the accompanying string of wars between those countries (War against SigismundWar against Sigismund

The war against Sigismund was a war between Duke Charles, later King Charles IX and Sigismund, King of Sweden and Poland. Lasting from 1598 to 1599, it is also called War of Deposition against Sigismund, since the focus of the conflicts was the attempt to depose the latter from the throne of Sweden...

(1598–1599), Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629) and the Northern Wars

Northern Wars

Northern Wars is a term used for a series of wars fought in northern and northeastern Europe in the 16th and 17th century. An internationally agreed nomenclature for these wars has not yet been devised...

(1655–1660)).

After the Treaty of Andrusovo in 1667 and the Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686

Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686

The Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686 was a treaty between Tsardom of Russia and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, signed by Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth envoys: voivod of Poznań Krzysztof Grzymułtowski and chancellor of Lithuania Marcjan Ogiński and Russian knyaz Vasily Vasilyevich...

, the Commonwealth lost left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine is a historic name of the part of Ukraine on the left bank of the Dnieper River, comprising the modern-day oblasts of Chernihiv, Poltava and Sumy as well as the eastern parts of the Kiev and Cherkasy....

to Russia.

Polish culture and the Greek Catholic Church

Greek Catholic Church

The Greek Catholic Church consists of the Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine liturgical tradition and are thus in full communion with the Bishop of Rome, the Pope.-List of Greek Catholic Churches:...

gradually advanced and by the 18th century, the population of Ducal Prussia was a mixture of Catholics and Protestants and used both the German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

and Polish languages. The rest of Poland and most of Lithuania remained firmly Roman Catholic, while Ukraine and some parts of Lithuania (i.e., Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

) were Greek Orthodox. The society was split into an upper stratum (8% nobles, 1%priests), townspeople (6%), Jews (10%), Ormians/Tatars (2%), and peasants (73%Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians and other). In the year 1772 out of the 12mln inhabitants there were: 43% Roman Catholics, 33% Greek Catholics, 10% Orthodox, 9% Jews, 4% Protestants, 1% Muslims.

Michael Korybut Wisniowiecki (King 1669–1673)

The Deluge (Polish history)

The term Deluge denotes a series of mid-17th century campaigns in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In a wider sense it applies to the period between the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648 and the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, thus comprising the Polish–Lithuanian theaters of the Russo-Polish and...

, the Polish nobility (szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

) elected Michael Korybut Wisniowiecki as king, believing he would further the interests of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was the first monarch of Polish origin since the last of Jagiellonian dynasty, Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus I was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the only son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548...

, died in 1572. Michael was a son of a successful but controversial military commander Jeremi Wiśniowiecki

Jeremi Wisniowiecki

Jeremi Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki was a notable member of the aristocracy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Prince at Wiśniowiec, Łubnie and Chorol and a father of future Polish king Michał I...

, known for his actions during the Khmelnytsky Uprising

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, was a Cossack rebellion in the Ukraine between the years 1648–1657 which turned into a Ukrainian war of liberation from Poland...

led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

.

His reign was less than successful, and the nobility was not satisfied with the House of Vasa

House of Vasa

The House of Vasa was the Royal House of Sweden 1523-1654 and of Poland 1587-1668. It originated from a noble family in Uppland of which several members had high offices during the 15th century....

's dynastic policies. Despite his father's military fame, Michael lost a war against the Ottoman Empire, with Turk

Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are peoples residing in northern, central and western Asia, southern Siberia and northwestern China and parts of eastern Europe. They speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family. They share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds...

s occupying Podolia

Podolia

The region of Podolia is an historical region in the west-central and south-west portions of present-day Ukraine, corresponding to Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Vinnytsia Oblast. Northern Transnistria, in Moldova, is also a part of Podolia...

and most of Ukraine in 1672-1673. He was unable to cope with his responsibilities and with the different quarreling factions within Poland.

John III Sobieski (King 1674–1696)

Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna took place on 11 and 12 September 1683 after Vienna had been besieged by the Ottoman Empire for two months...

, which marked the final turning point in a 250-year struggle between the forces of Christian Europe and the Islamic Ottoman Empire. Over the 16 years following the battle (the so-called Great Turkish War

Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War refers to a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and contemporary European powers, then joined into a Holy League, during the second half of the 17th century.-1667–1683:...

), the Turks would be permanently driven south of the Danube River, never to threaten central Europe again. When the Holy Alliance concluded peace with the Ottomans in 1699, Poland recovered Podolia and Ukraine. On other fronts, John III was less successful, including agreements with France and Sweden in a failed attempt to regain the Duchy of Prussia. Meanwhile, Kiev had been leased to the Russians for two years after 1667 and never returned. Poland formally relinquished all claims to the city in 1686.

Decay of the Commonwealth

During the 18th century the Polish crown itself becamesubject to the manipulations of Russia, Sweden, the Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, France and Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

. Poland's weakness was exacerbated by an unworkable constitution which allowed each noble or gentry representative in the Sejm to use his vetoing power to stop further parliamentary proceedings for the given session. This greatly weakened the central authority of Poland and paved the way for its destruction.

Most accounts of Polish history show the two centuries after the end of the Jagiellon dynasty

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty was a royal dynasty originating from the Lithuanian House of Gediminas dynasty that reigned in Central European countries between the 14th and 16th century...

as a time of decline leading to foreign domination.

Before another hundred years have elapsed, Poland-Lithuania had virtually ceased to function as a coherent and genuinely independent state. The commonwealth's last martial triumph occurred in 1683 when King John Sobieski drove the Turks from the gates of Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

with a heavy cavalry charge. Poland's important role in aiding the European alliance to roll back the Ottoman Empire was rewarded with some territory in Podole

Podolia

The region of Podolia is an historical region in the west-central and south-west portions of present-day Ukraine, corresponding to Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Vinnytsia Oblast. Northern Transnistria, in Moldova, is also a part of Podolia...

by the Treaty of Karlowicz (1699). Nonetheless, this isolated success did little to mask the internal weakness and paralysis of the Polish–Lithuanian political system. For the next quarter century, Poland was often a pawn in Russia's campaigns against other powers. When John III died in 1697, 18 candidates vied for the throne, which ultimately went to Frederick Augustus of Saxony, who then converted to Catholicism. Ruling as Augustus II, his reign presented the opportunity to unite Saxony (an industrialized area) with Poland, a country rich in mineral resources. However, the king lacked any skill in foreign policy and so became entangled in a war with Sweden. His allies the Russians and Danes were repelled by Charles XII of Sweden, beginning the Great Northern War

Great Northern War

The Great Northern War was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in northern Central Europe and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swedish alliance were Peter I the Great of Russia, Frederick IV of...

. Charles installed a puppet ruler in Poland and marched on Saxony, compelling Augustus to give up his crown and making Poland into a base for the Swedish army. Poland was again devastated by the armies of Sweden, Russia, and Saxony. Its major cities were destroyed and a third of the population killed by the war and a plague outbreak in 1709. The Swedes finally withdrew from Poland and invaded Ukraine, where they were defeated by the Russians at Poltava. Augustus was able to reclaim his throne with Russian support, but Peter the Great decided to annex Livonia in 1710. He also suppressed the Cossacks, who had been in revolt against Poland since 1699. Later on, the tsar frustrated an attempt by Prussia to regain territory from Poland (despite Augustus' approval of this). After the Great Northern War, Poland became an effective protectorate of Russia for the rest of the 18th century.

In the eighteenth century, the powers of the monarchy and the central administration became purely formal. Kings were denied permission to provide for the elementary requirements of defense and finance, and aristocratic clans made treaties directly with foreign sovereigns. Attempts at reform were stymied by the determination of the szlachta to preserve their "golden freedoms" most notably the liberum veto

Liberum veto