Timeline of the Manhattan Project

Encyclopedia

The following is a timeline

of the Manhattan Project

, the effort by the United States

, United Kingdom

, and Canada

to develop the first nuclear weapon

s for use during World War II

. The following includes a number of events prior to the official formation of the Manhattan Project as the Manhattan Engineering District (MED) in August 1942 and a number of events after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

, until the MED was formally replaced by the United States Atomic Energy Commission

in 1947.

Timeline

A timeline is a way of displaying a list of events in chronological order, sometimes described as a project artifact . It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labeled with dates alongside itself and events labeled on points where they would have happened.-Uses of timelines:Timelines...

of the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

, the effort by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, and Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

to develop the first nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s for use during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. The following includes a number of events prior to the official formation of the Manhattan Project as the Manhattan Engineering District (MED) in August 1942 and a number of events after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

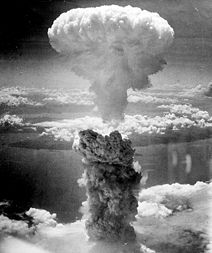

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

, until the MED was formally replaced by the United States Atomic Energy Commission

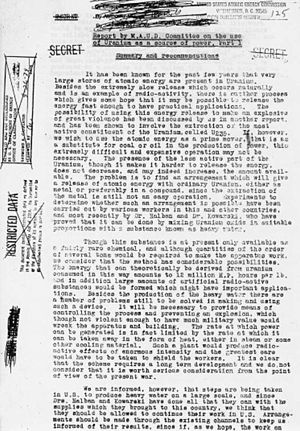

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by Congress to foster and control the peace time development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S...

in 1947.

1939

- August 2: Albert EinsteinAlbert EinsteinAlbert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

signs a letter authored by physicist Leó SzilárdLeó SzilárdLeó Szilárd was an Austro-Hungarian physicist and inventor who conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear reactor with Enrico Fermi, and in late 1939 wrote the letter for Albert Einstein's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb...

addressed to President Franklin D. RooseveltFranklin D. RooseveltFranklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

, advising him to fund research into the possibility of using nuclear fissionNuclear fissionIn nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into smaller parts , often producing free neutrons and photons , and releasing a tremendous amount of energy...

as a weapon in the event that Nazi GermanyNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

may also be conducting such research. He later regretted signing the letter. - September 1: Nazi Germany invades Poland, beginning World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. - October 11: Economist Alexander SachsAlexander SachsAlexander Sachs was an Jewish American economist and banker. In 1939, he delivered the Einstein–Szilárd letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt, in which it was suggested that nuclear research should be fomented....

meets with President Roosevelt and delivers the Einstein-Szilárd letterEinstein-Szilárd letterThe Einstein–Szilárd letter was a letter sent to the United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 2, 1939, that was signed by Albert Einstein but largely written by Leó Szilárd in consultation with fellow Hungarian physicists Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner. The letter suggested that the...

. Roosevelt authorizes the creation of the Advisory Committee on Uranium. - October 21: First meeting of the Uranium CommitteeS-1 Uranium CommitteeThe S-1 Uranium Committee was a Committee of the National Defense Research Committee that succeeded the Briggs Advisory Committee on Uranium and later evolved into the Manhattan Project.- World War II begins :...

, headed by Lyman Briggs of the National Bureau of Standards. $6,000 is budgeted for neutron experiments.

1940

- March: Otto Frisch and Rudolph Peierls author the Frisch-Peierls memorandumFrisch-Peierls memorandumThe Frisch–Peierls memorandum was written by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls while they were both working at the University of Birmingham, England. The memorandum contained new calculations about the size of the critical mass needed for an atomic bomb, and helped accelerate British and U.S...

, calculating that an atomic bomb might need as little as 1 lb of enriched uranium to work. - April 10: MAUD CommitteeMAUD CommitteeThe MAUD Committee was the beginning of the British atomic bomb project, before the United Kingdom joined forces with the United States in the Manhattan Project.-Frisch & Peierls:...

(Military Application of Uranium Detonation) established by Henry TizardHenry TizardSir Henry Thomas Tizard FRS was an English chemist and inventor and past Rector of Imperial College....

to investigate feasibility of an atomic bomb - July 1: Responsibility for fission research is taken over by Vannevar BushVannevar BushVannevar Bush was an American engineer and science administrator known for his work on analog computing, his political role in the development of the atomic bomb as a primary organizer of the Manhattan Project, the founding of Raytheon, and the idea of the memex, an adjustable microfilm viewer...

's National Defense Research CommitteeNational Defense Research CommitteeThe National Defense Research Committee was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the United States from June 27, 1940 until June 28, 1941...

. - December: Franz SimonFrancis SimonSir Francis Simon, born Franz Eugen Simon , was a German and later British physical chemist and physicist who devised the method, and confirmed its feasibility, of separating the isotope Uranium-235 and thus made a major contribution to the creation of the atomic bomb.-Early life:He was born to a...

reports to MAUD that uranium-235 can be separated using gaseous diffusionGaseous diffusionGaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride through semi-permeable membranes. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235 and uranium-238 . By use of a large cascade of many stages, high separations...

. Gives cost estimates and technical specifications. James ChadwickJames ChadwickSir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

realizes "a nuclear bomb...is inevitable"

1941

- February 26: Conclusive discovery of plutoniumPlutoniumPlutonium is a transuranic radioactive chemical element with the chemical symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, forming a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four oxidation...

by Glenn Seaborg and Arthur WahlArthur WahlArthur C. Wahl was an American chemist who, as a PhD student of Glenn T. Seaborg at UC Berkeley, first isolated plutonium in February 1941. He also worked on the Manhattan Project.- Further readings :...

. - April - May: MAUD committee research in Liverpool, led by Chadwick, showed that a bomb's critical mass could be reached with maybe less than 8 kg of uranium. Nazis' bombing of the immediate environs of his lab, plus the burden of keeping such key findings secret from all others there, made Chadwick desolate: "it was inevitable.... Some country would put them into action.... I had to then take sleeping pills. It was the only remedy."

- May 17: A report by Arthur ComptonArthur ComptonArthur Holly Compton was an American physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his discovery of the Compton effect. He served as Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis from 1945 to 1953.-Early years:...

and the National Academy of SciencesUnited States National Academy of SciencesThe National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

is issued which finds favorable the prospects of developing nuclear power production for military use. Vannevar BushVannevar BushVannevar Bush was an American engineer and science administrator known for his work on analog computing, his political role in the development of the atomic bomb as a primary organizer of the Manhattan Project, the founding of Raytheon, and the idea of the memex, an adjustable microfilm viewer...

creates the Office of Scientific Research and DevelopmentOffice of Scientific Research and DevelopmentThe Office of Scientific Research and Development was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1941, and it was created formally by on June 28, 1941...

(OSRD) - July 2: The MAUD Committee chooses James Chadwick to write the second (and final) draft of its report on the design and costs of developing a bomb.

- July 15: The MAUD Committee issues final detailed technical report on design and costs to develop a bomb. Advance copy sent to Vannevar BushVannevar BushVannevar Bush was an American engineer and science administrator known for his work on analog computing, his political role in the development of the atomic bomb as a primary organizer of the Manhattan Project, the founding of Raytheon, and the idea of the memex, an adjustable microfilm viewer...

who decides to wait for official version before taking any action. - August: Mark Oliphant travels to USA to urge development of a bomb rather than power production http://www.childrenofthemanhattanproject.org/HISTORY/H-04f.htm

- October 3: Official copy of MAUD Report (written by Chadwick) reaches Bush.

- October 9: Bush takes MAUD Report to Roosevelt, who approves Project to confirm MAUD's findings: "Roosevelt indicated that he could find a way to finance the project and asked Bush to draft a letter so that the British government could be approached 'at the top.' " http://www.cfo.doe.gov/me70/manhattan/tentative_decision_build.htm

- December 6: Vannevar Bush holds a meeting to organize an accelerated research project, still managed by Arthur ComptonArthur ComptonArthur Holly Compton was an American physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his discovery of the Compton effect. He served as Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis from 1945 to 1953.-Early years:...

. Harold UreyHarold UreyHarold Clayton Urey was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934...

is assigned to develop research into gaseous diffusion as a uranium enrichment method, while Ernest O. Lawrence is assigned to investigate electromagnetic separation methods. - December 7: The Japanese attack Pearl HarborAttack on Pearl HarborThe attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

. The United States issues a formal declaration of war against Japan the next day. Four days later, Nazi GermanyNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

declares war on the United States. - December 18: First meeting of the OSRD sponsored S-1 projectS-1 Uranium CommitteeThe S-1 Uranium Committee was a Committee of the National Defense Research Committee that succeeded the Briggs Advisory Committee on Uranium and later evolved into the Manhattan Project.- World War II begins :...

, dedicated to developing fission weapons

1942

- July–September: Physicist Robert OppenheimerRobert OppenheimerJulius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project, the World War II project that developed the first...

convenes a summer conference at the University of California, BerkeleyUniversity of California, BerkeleyThe University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

to discuss the design of a fission bomb. Edward TellerEdward TellerEdward Teller was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist, known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb," even though he did not care for the title. Teller made numerous contributions to nuclear and molecular physics, spectroscopy , and surface physics...

brings up the possibility of a hydrogen bomb as a major point of discussion. - August: Creation of the Manhattan Engineering District by the Army Corps of Engineers.

- September 13: At a meeting of the S-1 Executive Committee, it is decided that a centralized laboratory should be established to study fast neutrons, code-named "Project Y".

- September 17: Col. Leslie GrovesLeslie GrovesLieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr. was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb during World War II. As the son of a United States Army chaplain, Groves lived at a...

is assigned command of the Manhattan Engineering District. Six days later he is appointed to Brigadier General. - September 24: After a visit to Tennessee, Groves purchases 52,000 acres (210 km²) of land in TennesseeTennesseeTennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

for "Site X", which will become the Oak Ridge, TennesseeOak Ridge, TennesseeOak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 27,387 at the 2000 census...

laboratory and production site. - September 26: The Manhattan Project is given permission to use the highest wartime priority rating by the War Production BoardWar Production BoardThe War Production Board was established as a government agency on January 16, 1942 by executive order of Franklin D. Roosevelt.The purpose of the board was to regulate the production and allocation of materials and fuel during World War II in the United States...

. - October 15: Groves appoints Robert OppenheimerRobert OppenheimerJulius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project, the World War II project that developed the first...

to coordinate the scientific research of the project at the "Site Y" laboratory. - November 16: Groves and Oppenheimer visit Los Alamos, New MexicoLos Alamos, New MexicoLos Alamos is a townsite and census-designated place in Los Alamos County, New Mexico, United States, built upon four mesas of the Pajarito Plateau and the adjoining White Rock Canyon. The population of the CDP was 12,019 at the 2010 Census. The townsite or "the hill" is one part of town while...

and designate it as the location for "Site Y". - December 2: Chicago Pile-1Chicago Pile-1Chicago Pile-1 was the world's first man-made nuclear reactor. CP-1 was built on a rackets court, under the abandoned west stands of the original Alonzo Stagg Field stadium, at the University of Chicago. The first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 on December 2, 1942...

, the first nuclear reactorNuclear reactorA nuclear reactor is a device to initiate and control a sustained nuclear chain reaction. Most commonly they are used for generating electricity and for the propulsion of ships. Usually heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid , which runs through turbines that power either ship's...

goes critical at the University of ChicagoUniversity of ChicagoThe University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

under the leadership and design of Enrico FermiEnrico FermiEnrico Fermi was an Italian-born, naturalized American physicist particularly known for his work on the development of the first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and for his contributions to the development of quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics...

.

1943

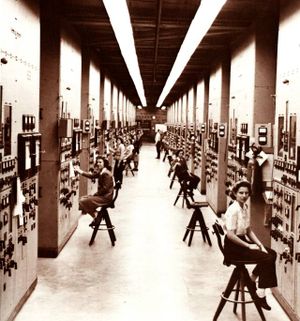

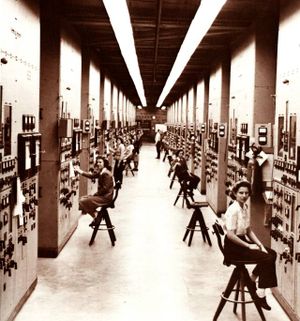

- February 18: Construction begins for Y-12 at Oak Ridge, TennesseeOak Ridge, TennesseeOak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 27,387 at the 2000 census...

, a massive electromagnetic separation plant for enriching uranium. - April 5–14: Introductory lectures began at Los Alamos, later are compiled into The Los Alamos Primer.

- April 20: The University of CaliforniaUniversity of CaliforniaThe University of California is a public university system in the U.S. state of California. Under the California Master Plan for Higher Education, the University of California is a part of the state's three-tier public higher education system, which also includes the California State University...

becomes the formal business manager of the Los AlamosLos Alamos National LaboratoryLos Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

laboratory. - August 19: Roosevelt and Winston ChurchillWinston ChurchillSir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

sign Quebec AgreementQuebec AgreementThe Quebec Agreement is an Anglo-Canadian-American document outlining the terms of nuclear nonproliferation between the United Kingdom and the United States, and signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt on August 19, 1943, two years before the end of World War II, in Quebec City,...

. Team of British scientists join project as a result, including Klaus FuchsKlaus FuchsKlaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II... - October 4: Construction begins for the first reactor at Hanford SiteHanford SiteThe Hanford Site is a mostly decommissioned nuclear production complex on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington, operated by the United States federal government. The site has been known by many names, including Hanford Works, Hanford Engineer Works or HEW, Hanford Nuclear Reservation...

. - October: Project W-47, later called Project AlbertaProject AlbertaProject Alberta was a section of the Manhattan Project which developed the means of delivering the first atomic bombs, used by the United States Army Air Forces against the Empire of Japan during World War II...

set up to plan delivery of the bomb

1944

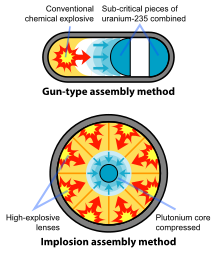

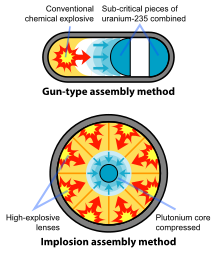

- April 5: At Los Alamos, Emilio Segrè receives the first sample of reactor-bred plutonium from Oak Ridge, and within ten days discovers that the spontaneous fission rate is too high for use in a gun-type fission weaponGun-type fission weaponGun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another...

. - May: Fermi at Los Alamos tests the world's third reactor, LOPO, the first aqueous homogeneous reactorAqueous homogeneous reactorAqueous homogeneous reactors are a type of nuclear reactor in which soluble nuclear salts have been dissolved in water. The fuel is mixed with the coolant and the moderator, thus the name "homogeneous" The water can be either heavy water or light water, both which need to be very pure...

, and the first fueled by enriched uraniumEnriched uraniumEnriched uranium is a kind of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Natural uranium is 99.284% 238U isotope, with 235U only constituting about 0.711% of its weight...

. - July 4: Oppenheimer reveals Segrè's final measurements to the Los Alamos staff, and the development of the gun-type plutonium weapon "Thin ManThin Man nuclear bombThe "Thin Man" nuclear bomb was a proposed plutonium gun-type nuclear bomb which the United States was developing during the Manhattan Project...

" is abandoned. Designing a workable "implosion" design becomes top priority of the laboratory. - July 20: The Los Alamos organizational structure is completely changed to reflect the new priority of "implosion".

- July 25: First preliminary test of the RaLa ExperimentRaLa ExperimentThe RaLa Experiment, or RaLa, was a series of tests during and after the Manhattan Project designed to study the behavior of converging shock waves to achieve the spherical implosion necessary for compression of the plutonium pit of the nuclear weapon...

series performed - September 2: chemists Peter N. Bragg, Jr. http://www.mphpa.org/classic/FH/PH/Peter_Bragg.htm and Douglas P. Meigs http://www.mphpa.org/classic/FH/PH/Douglas_Meigs.htm are killed, and Arnold KramishArnold KramishArnold Kramish was an American nuclear physicist and author who was associated with the Manhattan Project. While working on the project, he was nearly killed in an accident at the Philadelphia Naval Yard where a prototype thermal diffusion isotope separation device was being constructed...

almost killed, while attempting to unclog a uranium enrichment device which is part of the pilot thermal diffusion plant at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Two soldiers, George LeFevre and John Tompkins, also receive extensive injuries. An explosion of liquid uranium hexafluoride burst nearby steam pipes, and steam combined with the uranium hexafluoride to spray them with highly corrosive hydrofluoric acidHydrofluoric acidHydrofluoric acid is a solution of hydrogen fluoride in water. It is a valued source of fluorine and is the precursor to numerous pharmaceuticals such as fluoxetine and diverse materials such as PTFE ....

. See also http://www.mphpa.org/classic/FH/PH/Article_04_1.htm http://www.mphpa.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=93&Itemid=84 and http://www.mphpa.org/classic/FH/PH/Louis_McDonough.htm - September 22: First RaLa test with a radioactive source performed

- December 9: 509th Composite Group509th Composite GroupThe 509th Composite Group was a United States Army Air Forces unit created during World War II, and tasked with operational deployment of nuclear weapons...

of USAAF constituted to deliver the bomb - December 14: Definite evidence of achievable compression obtained in a RaLa test

- Mid-December: Successful test of explosive lensExplosive lensAn explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized explosive charge, a special type of a shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges that are shaped in such a way as to change the shape of the detonation wave passing through it,...

for Fat ManFat Man"Fat Man" is the codename for the atomic bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, by the United States on August 9, 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons to be used in warfare to date , and its detonation caused the third man-made nuclear explosion. The name also refers more...

.

1945

- January: Gen. Thomas Farrell named Gen. Groves' deputy.

- January 7: First RaLaRALARas-related protein Ral-A is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RALA gene.-Interactions:RALA has been shown to interact with Filamin, Phospholipase D1 and RALBP1.-Further reading:...

test using exploding bridgewire detonators - January 14: Second RaLa test using exploding bridgewire detonators

- May 7: Nazi Germany formally surrenders to Allied powers, marking the end of World War II in EuropeEnd of World War II in EuropeThe final battles of the European Theatre of World War II as well as the German surrender to the Western Allies and the Soviet Union took place in late April and early May 1945.-Timeline of surrenders and deaths:...

. - May 10–11: second meeting of the Target Committee, at Los Alamos, which works to finalize the list of cities on which atomic bombs may be dropped.http://www.dannen.com/decision/targets.html

- June 11: Metallurgical Laboratory scientists under James FranckJames FranckJames Franck was a German Jewish physicist and Nobel laureate.-Biography:Franck was born to Jacob Franck and Rebecca Nachum Drucker. Franck completed his Ph.D...

issue the Franck ReportFranck ReportThe Franck Report of June 1945 was a document signed by several prominent nuclear physicists recommending that the United States not use the atomic bomb as a weapon to prompt the surrender of Japan in World War II....

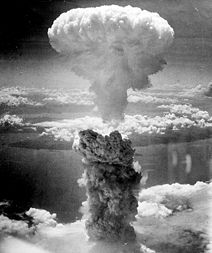

arguing for a demonstration of the bomb before using it against civilian targets. - July 16: the first nuclear explosionNuclear explosionA nuclear explosion occurs as a result of the rapid release of energy from an intentionally high-speed nuclear reaction. The driving reaction may be nuclear fission, nuclear fusion or a multistage cascading combination of the two, though to date all fusion based weapons have used a fission device...

, the "TrinityTrinity testTrinity was the code name of the first test of a nuclear weapon. This test was conducted by the United States Army on July 16, 1945, in the Jornada del Muerto desert about 35 miles southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, at the new White Sands Proving Ground, which incorporated the Alamogordo Bombing...

" test of an implosion-style plutonium-based nuclear weaponNuclear weaponA nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

known as "the gadget", near Alamogordo, New MexicoAlamogordo, New MexicoAlamogordo is the county seat of Otero County and a city in south-central New Mexico, United States. A desert community lying in the Tularosa Basin, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains. It is the nearest city to Holloman Air Force Base. The population was 35,582 as of the 2000...

. - July 24: President Harry S. TrumanHarry S. TrumanHarry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

discloses to Soviet leader Joseph StalinJoseph StalinJoseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

that the United States has atomic weapons. Stalin feigns little surprise; he already knows this through espionage. - July 25: General Carl SpaatzCarl SpaatzCarl Andrew "Tooey" Spaatz GBE was an American World War II general and the first Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. He was of German descent.-Early life:...

is ordered to bomb one of the targets: HiroshimaHiroshimais the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture, and the largest city in the Chūgoku region of western Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It became best known as the first city in history to be destroyed by a nuclear weapon when the United States Army Air Forces dropped an atomic bomb on it at 8:15 A.M...

, KokuraKokurais an ancient castle town and the center of Kitakyūshū, Japan, guarding, via its suburb Moji, the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshū and Kyūshū. Kokura is also the name of the penultimate station on the southbound Sanyo Shinkansen line, which is owned by JR Kyūshū and an important part of the...

, NiigataNiigata, Niigatais the capital and the most populous city of Niigata Prefecture, Japan. It lies on the northwest coast of Honshu, the largest island of Japan, and faces the Sea of Japan and Sado Island....

, or NagasakiNagasakiis the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan. Nagasaki was founded by the Portuguese in the second half of the 16th century on the site of a small fishing village, formerly part of Nishisonogi District...

as soon as weather permitted, some time after August 3.http://www.mbe.doe.gov/me70/manhattan/order_drop.htm http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/library/correspondence/handy-thomas/corr_handy_1945-07-25.htm - August 6: "Little BoyLittle Boy"Little Boy" was the codename of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, of the United States Army Air Forces. It was the first atomic bomb to be used as a weapon...

", a gun-type uranium-235 weapon, is used againstAtomic bombings of Hiroshima and NagasakiDuring the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

the city of Hiroshima, JapanJapanJapan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

(the primary target). - August 9: "Fat ManFat Man"Fat Man" is the codename for the atomic bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, by the United States on August 9, 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons to be used in warfare to date , and its detonation caused the third man-made nuclear explosion. The name also refers more...

", an implosion-type plutonium-239Plutonium-239Plutonium-239 is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 has also been used and is currently the secondary isotope. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main isotopes demonstrated usable as fuel in...

weapon, is used againstAtomic bombings of Hiroshima and NagasakiDuring the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

the city of Nagasaki, JapanJapanJapan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

(the secondary target, as the primary target, Kokura, was obscured by cloud). - August 12: The Smyth ReportSmyth ReportThe Smyth Report was the common name given to an administrative history written by physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth about the Allied World War II effort to develop the atomic bomb, the Manhattan Project...

is released to the public, giving the first technical history of the development of the first atomic bombs. - August 15: Surrender of JapanSurrender of JapanThe surrender of Japan in 1945 brought hostilities of World War II to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy was incapable of conducting operations and an Allied invasion of Japan was imminent...

to the Allied powers. - August 21: Harry K. Daghlian, Jr.Harry K. Daghlian, Jr.Haroutune Krikor Daghlian, Jr. was an Armenian-American physicist with the Manhattan Project who accidentally irradiated himself on August 21, 1945, during a critical mass experiment at the remote Omega Site facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, resulting in his death 25 days...

, a physicist, receives a fatal dose (510 rems) of radiation from a criticality accidentCriticality accidentA criticality accident, sometimes referred to as an excursion or a power excursion, is an accidental increase of nuclear chain reactions in a fissile material, such as enriched uranium or plutonium...

when he accidentally dropped a tungsten carbideTungsten carbideTungsten carbide is an inorganic chemical compound containing equal parts of tungsten and carbon atoms. Colloquially, tungsten carbide is often simply called carbide. In its most basic form, it is a fine gray powder, but it can be pressed and formed into shapes for use in industrial machinery,...

brick onto a plutonium bomb core. He dies on September 15. - October 16: Oppenheimer resigns as director of Los Alamos, and is succeeded by Norris BradburyNorris BradburyNorris Edwin Bradbury , was an American physicist who was born in Santa Barbara, California. He served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years , succeeding J. Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbury for the position of director after working closely with him on the...

the next day.

1946

- February: News of the Canadian spy ring exposed by defector Igor GouzenkoIgor GouzenkoIgor Sergeyevich Gouzenko was a cipher clerk for the Soviet Embassy to Canada in Ottawa, Ontario. He defected on September 5, 1945, with 109 documents on Soviet espionage activities in the West...

is made public (leaked by General Groves), creating a mild "atom spyAtomic SpiesAtomic Spies and Atom Spies are terms that refer to various people in the United States, Great Britain, and Canada who are thought to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold War...

" hysteria, pushing American Congressional discussions about postwar atomic regulation in a more conservative direction. - May 21: Louis SlotinLouis SlotinLouis Alexander Slotin was a Canadian physicist and chemist who took part in the Manhattan Project, the secret US program during World War II that developed the atomic bomb....

, a physicist, received a fatal dose of radiation (2100 rems) when the screwdriver he was using to keep two berylliumBerylliumBeryllium is the chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a divalent element which occurs naturally only in combination with other elements in minerals. Notable gemstones which contain beryllium include beryl and chrysoberyl...

hemispheres apart slipped; they were placed around the same plutonium core that had irradiated Daghilan. The upper hemisphere fell, causing a "prompt criticalPrompt criticalIn nuclear engineering, an assembly is prompt critical if for each nuclear fission event, one or more of the immediate or prompt neutrons released causes an additional fission event. This causes a rapid, exponential increase in the number of fission events...

" reaction with a burst of hard radiationHard radiationHard radiation is a term used to describe high-energy electromagnetic radiation, typically high energy X-rays or gamma rays. The term refers to the ability of the rays to penetrate a given thickness of material, typically a lead shield....

. Slotin lifted the upper hemisphere with his left hand and dropped it on the floor, so preventing a more serious accident. He was rushed to hospital, and died nine days later on May 30. Slotin had spent many hours with the dying Daghlian in 1945. - August 1: Harry S. TrumanHarry S. TrumanHarry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

signs the Atomic Energy Act of 1946Atomic Energy Act of 1946The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 determined how the United States federal government would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its wartime allies...

into law, ending almost a year of uncertainty about the control of atomic research in the postwar United States.

1947

- January 1: the Atomic Energy Act of 1946Atomic Energy Act of 1946The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 determined how the United States federal government would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its wartime allies...

(known as the McMahon Act) takes effect, and the Manhattan Project is officially turned over to the United States Atomic Energy CommissionUnited States Atomic Energy CommissionThe United States Atomic Energy Commission was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by Congress to foster and control the peace time development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S...

.

External links

- Chronology for the origin of atomic weapons from Carey Sublette's NuclearWeaponArchive.org

- Manhattan Project Chronology from Department of Energy's The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb