Surrender of Japan

Encyclopedia

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1869 until 1947, when it was dissolved following Japan's constitutional renunciation of the use of force as a means of settling international disputes...

was incapable of conducting operations and an Allied invasion of Japan

Operation Downfall

Operation Downfall was the Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of World War II. The operation was cancelled when Japan surrendered after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union's declaration of war against Japan. The operation had two parts: Operation...

was imminent. While publicly stating their intent to fight on to the bitter end, Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

's leaders at the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War

Supreme War Council (Japan)

The Supreme War Council was established during the development of representative government in Meiji period Japan to further strengthen the authority of the state. Its first leader was Yamagata Aritomo , a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to...

(the "Big Six") were privately making entreaties to the neutral Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, to mediate peace on terms favorable to the Japanese. The Soviets, meanwhile, were preparing to attack the Japanese, in fulfillment of their promises to the Americans and the British made at the Tehran

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference was the meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill between November 28 and December 1, 1943, most of which was held at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. It was the first World War II conference amongst the Big Three in which Stalin was present...

and Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

s.

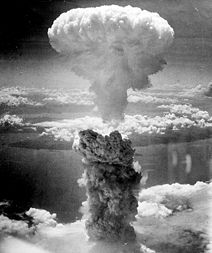

On August 6, the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

. Late in the evening of August 8, in accordance with Yalta agreements but in violation of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and soon after midnight on August 9, it invaded the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Later that day the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

. The combined shock of these events caused Emperor Hirohito

Hirohito

, posthumously in Japan officially called Emperor Shōwa or , was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989. Although better known outside of Japan by his personal name Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to...

to intervene and order the Big Six to accept the terms for ending the war that the Allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

had set down in the Potsdam Declaration

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender is a statement calling for the Surrender of Japan in World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S...

. After several more days of behind-the-scenes negotiations and a failed coup d'état

Kyujo Incident

The ' was an attempted military coup d'état in Japan at the end of the Second World War. It happened on the night of 14 August 1945 – 15 August 1945, just prior to announcement of Japan's surrender to the Allies...

, Hirohito gave a recorded radio address to the nation on August 15. In the radio address, called the Gyokuon-hōsō

Gyokuon-hoso

The , lit. "Jewel Voice Broadcast", was the radio broadcast in which Japanese emperor Hirohito read out the , announcing to the Japanese people that the Japanese Government had accepted the Potsdam Declaration demanding the unconditional surrender of the Japanese military at the end of World War II...

("Jewel Voice Broadcast"), he announced the surrender of Japan.

On August 28, the occupation of Japan by the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers

Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers

Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the Occupation of Japan following World War II...

began. The surrender ceremony was held on September 2 aboard the U.S. battleship , at which officials from the Japanese government signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender

Japanese Instrument of Surrender

The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that enabled the Surrender of Japan, marking the end of World War II. It was signed by representatives from the Empire of Japan, the United States of America, the Republic of China, the United Kingdom, the Union of Soviet Socialist...

, ending World War II. Allied civilians and servicemen alike celebrated V-J Day, the end of the war; however, some isolated soldiers and personnel from Japan's far-flung forces throughout Asia and the Pacific islands refused to surrender

Japanese holdout

Japanese holdouts or stragglers were Japanese soldiers in the Pacific Theatre who, after the August 1945 surrender of Japan that marked the end of World War II, either adamantly doubted the veracity of the formal surrender due to strong dogmatic or militaristic principles, or were not aware of it...

for months and years after, some into the 1970s. Since Japan's surrender, historians have debated the ethics of using the atomic bombs

Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki concerns the ethical, legal and military controversies surrounding the United States' atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 August and 9 August 1945 at the close of the Second World War...

.

The state of war between Japan and the United States formally ended when the Treaty of San Francisco

Treaty of San Francisco

The Treaty of Peace with Japan , between Japan and part of the Allied Powers, was officially signed by 48 nations on September 8, 1951, at the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco, California...

came into force on April 28, 1952. Four more years passed before Japan and the Soviet Union signed the Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956 which formally brought an end to the state of war.

Impending defeat

South West Pacific theatre of World War II

The South West Pacific Theatre, technically the South West Pacific Area, between 1942 and 1945, was one of two designated area commands and war theatres enumerated by the Combined Chiefs of Staff of World War II in the Pacific region....

, the Marianas campaign

Mariana and Palau Islands campaign

The Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, also known as Operation Forager, was an offensive launched by United States forces against Imperial Japanese forces in the Mariana Islands and Palau in the Pacific Ocean between June and November, 1944 during the Pacific War...

, and the Philippines campaign. In July 1944, following the loss of Saipan

Battle of Saipan

The Battle of Saipan was a battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II, fought on the island of Saipan in the Mariana Islands from 15 June-9 July 1944. The Allied invasion fleet embarking the expeditionary forces left Pearl Harbor on 5 June 1944, the day before Operation Overlord in Europe was...

, General Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tōjō was a general of the Imperial Japanese Army , the leader of the Taisei Yokusankai, and the 40th Prime Minister of Japan during most of World War II, from 17 October 1941 to 22 July 1944...

was replaced as prime minister by General Kuniaki Koiso

Kuniaki Koiso

- Notes :...

, who declared that the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

would be the site of the decisive battle. After the Japanese loss of the Philippines, Koiso in turn was replaced by Admiral Kantarō Suzuki

Kantaro Suzuki

Baron was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, member and final leader of the Taisei Yokusankai and 42nd Prime Minister of Japan from 7 April-17 August 1945.-Early life:...

. The first half of 1945 saw the Allies capture the nearby islands of Iwo Jima

Battle of Iwo Jima

The Battle of Iwo Jima , or Operation Detachment, was a major battle in which the United States fought for and captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Empire of Japan. The U.S...

and Okinawa

Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War of World War II. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June 1945...

. Okinawa was to be a staging area

Staging area

A staging area is a location where organisms, people, vehicles, equipment or material are assembled before use.- In construction :...

for Operation Downfall

Operation Downfall

Operation Downfall was the Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of World War II. The operation was cancelled when Japan surrendered after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union's declaration of war against Japan. The operation had two parts: Operation...

, the American invasion of the Japanese Home Islands

Japanese Archipelago

The , which forms the country of Japan, extends roughly from northeast to southwest along the northeastern coast of the Eurasia mainland, washing upon the northwestern shores of the Pacific Ocean...

. Following Germany's defeat, the Soviet Union quietly began redeploying its battle-hardened European forces to the Far East, in addition to about forty divisions that had been stationed there since 1941, as a counterbalance to the million-strong Kwantung Army.

The Allied submarine campaign

Allied submarines in the Pacific War

Allied submarines were used extensively during the Pacific War and were a key contributor to the defeat of the Empire of Japan. During the war, submarines of the United States Navy were responsible for 55% of Japan's merchant marine losses; other Allied navies added to the toll. The war against...

and the mining of Japanese coastal waters

Operation Starvation

Operation Starvation was an American naval mining operation conducted in World War II by the Army Air Force, in which vital water routes and ports of Japan were mined by air in order to disrupt enemy shipping.-Operation:...

had largely destroyed the Japanese merchant fleet. With few natural resources, Japan was dependent on raw materials, particularly oil, imported from Manchuria and other parts of the East Asian mainland, and from the conquered territory in the Dutch East Indies

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Netherlands government in 1800....

. The destruction of the Japanese merchant fleet, combined with the strategic bombing of Japanese industry, had wrecked Japan's war economy. Production of coal, iron, steel, rubber, and other vital supplies was only a fraction of that before the war.

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1869 until 1947, when it was dissolved following Japan's constitutional renunciation of the use of force as a means of settling international disputes...

(IJN) had ceased to be an effective fighting force. Following a series of raids

Bombing of Kure (July 1945)

The bombing of Kure and surrounding areas by United States and British naval aircraft in late July 1945 led to the sinking of most of the surviving large warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy . The United States Third Fleet's attacks on Kure Naval Arsenal and nearby ports on 24, 25, and 28 July...

on the Japanese shipyard at Kure, Japan

Kure Naval Arsenal

was one of four principal naval shipyards owned and operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy. -History:The Kure Naval District was established at Kure, Hiroshima in 1889, as the second of the naval districts responsible for the defense of the Japanese home islands along with the establishment of the...

, the only major warships in fighting order were six aircraft carriers, four cruisers, and one battleship, none of which could be fueled adequately. Although 19 destroyers and 38 submarines were still operational, their use was limited by the lack of fuel.

Defense preparations

Faced with the prospect of an invasion of the Home Islands starting with KyūshūKyushu

is the third largest island of Japan and most southwesterly of its four main islands. Its alternate ancient names include , , and . The historical regional name is referred to Kyushu and its surrounding islands....

, and also the prospect of a Soviet invasion of Manchuria, Japan's last source of natural resources, the War Journal of the Imperial Headquarters concluded:

We can no longer direct the war with any hope of success. The only course left is for Japan's one hundred million people to sacrifice their lives by charging the enemy to make them lose the will to fight.

As a final attempt to stop the Allied advances, the Japanese Imperial High Command planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū codenamed Operation Ketsugō. This was to be a radical departure from the "defense in depth

Defence in depth

Defence in depth is a military strategy; it seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space...

" plans used in the invasions of Peleliu

Battle of Peleliu

The Battle of Peleliu, codenamed Operation Stalemate II, was fought between the United States and the Empire of Japan in the Pacific Theater of World War II, from September–November 1944 on the island of Peleliu, present-day Palau. U.S...

, Iwo Jima

Battle of Iwo Jima

The Battle of Iwo Jima , or Operation Detachment, was a major battle in which the United States fought for and captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Empire of Japan. The U.S...

, and Okinawa

Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War of World War II. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June 1945...

. Instead, everything was staked on the beachhead; more than 3,000 kamikaze

Kamikaze

The were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, designed to destroy as many warships as possible....

s would be sent to attack the amphibious transports before troops and cargo were disembarked on the beach.

If this did not drive the Allies away, they planned to send another 3,500 kamikazes along with 5,000 Shin'yō suicide boats and the remaining destroyers and submarines—"the last of the Navy's operating fleet"—to the beach. If the Allies had fought through this and successfully landed on Kyūshū, only 3,000 planes would have been left to defend the remaining islands, although Kyūshū would be "defended to the last" regardless. A set of caves were excavated near Nagano. In the event of invasion, these caves, the Matsushiro Underground Imperial Headquarters

Matsushiro Underground Imperial Headquarters

The was a large underground bunker complex built during the Second World War in the Matsushiro suburb of Nagano, Japan.. The facility was to be used by Emperor Hirohito, his family, and the Imperial General Headquarters to direct Japanese armed forces fighting against the Allied invasion of...

, were to be used by the army to direct the war and to house the emperor and his family.

Supreme Council for the Direction of the War

Japanese policy-making centered on the Supreme Council for the Direction of the WarSupreme War Council (Japan)

The Supreme War Council was established during the development of representative government in Meiji period Japan to further strengthen the authority of the state. Its first leader was Yamagata Aritomo , a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to...

(created in 1944 by earlier Prime Minister Kuniaki Koiso

Kuniaki Koiso

- Notes :...

), the so-called "Big Six"—the Prime Minister

Prime Minister of Japan

The is the head of government of Japan. He is appointed by the Emperor of Japan after being designated by the Diet from among its members, and must enjoy the confidence of the House of Representatives to remain in office...

, Minister of Foreign Affairs

Minister for Foreign Affairs (Japan)

The of Japan is the Cabinet member responsible for Japanese foreign policy and the chief executive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Since the end of the American occupation of Japan, the position has been one of the most powerful in the Cabinet, as Japan's economic interests have long relied on...

, Minister of the Army

Ministry of War of Japan

The , more popularly known as the Ministry of War of Japan, was cabinet-level ministry in the Empire of Japan charged with the administrative affairs of the Imperial Japanese Army...

, Minister of the Navy

Ministry of the Navy of Japan

The was a cabinet-level ministry in the Empire of Japan charged with the administrative affairs of the Imperial Japanese Navy . It existed from 1872 to 1945.-History:...

, Chief of the Army

Imperial Japanese Army

-Foundation:During the Meiji Restoration, the military forces loyal to the Emperor were samurai drawn primarily from the loyalist feudal domains of Satsuma and Chōshū...

General Staff, and Chief of the Navy

Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff

The was the highest organ within the Imperial Japanese Navy. In charge of planning and operations, it was headed by an Admiral headquartered in Tokyo.-History:...

General Staff. At the formation of the Suzuki government in April 1945, the council's membership consisted of:

- Prime Minister: Admiral Kantarō SuzukiKantaro SuzukiBaron was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, member and final leader of the Taisei Yokusankai and 42nd Prime Minister of Japan from 7 April-17 August 1945.-Early life:...

- Minister of Foreign Affairs: Shigenori TōgōShigenori Togowas Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Empire of Japan at both the start and the end of the Japanese-American conflict during World War II...

- Minister of the Army: General Korechika Anami

- Minister of the Navy: Admiral Mitsumasa YonaiMitsumasa Yonaiwas an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, and politician. He was the 37th Prime Minister of Japan from 16 January to 22 July 1940.-Early life & Naval career:...

- Chief of the Army General Staff: General Yoshijirō Umezu

- Chief of the Navy General Staff: Admiral Koshirō OikawaKoshiro Oikawawas an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy and Naval Minister during World War II.-Biography:Oikawa was born into a wealthy family in rural Koshi County, Niigata Prefecture, but was raised in Morioka city, Iwate prefecture in northern Japan....

(later replaced by Admiral Soemu Toyoda)

Legally, the Japanese Army and Navy had the right to nominate (or refuse to nominate) their respective ministers. Thus, they could prevent the formation of undesirable governments, or by resignation bring about the collapse of an existing government.

Emperor Hirohito

Hirohito

, posthumously in Japan officially called Emperor Shōwa or , was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989. Although better known outside of Japan by his personal name Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to...

and Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan

The was an administrative post not of Cabinet rank in the government of the Empire of Japan. The Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal was responsible for keeping the Privy Seal of Japan and State Seal of Japan....

Kōichi Kido

Koichi Kido

Marquis served as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal from 1940 to 1945, and was the closest advisor to Emperor Showa throughout World War II.Kido was the grandson of Kido Takayoshi, one of the leaders of the Meiji Restoration...

also were present at some of the meetings, following the emperor's wishes.

Divisions within the Japanese leadership

For the most part, Suzuki's military-dominated cabinet favored continuing the war. For the Japanese, surrender was unthinkable—Japan had never been invaded or lost a war in its history. Only Mitsumasa Yonai, the Navy minister, was known to desire an early end to the war. According to historian Richard B. FrankRichard B. Frank

Richard B. Frank is an American lawyer and military historian.Frank graduated from the University of Missouri in 1969, after which he served four years in the United States Army. During the Vietnam War, he served a tour of duty as a platoon leader in the 101st Airborne Division...

:

- Although Suzuki might indeed have seen peace as a distant goal, he had no design to achieve it within any immediate time span or on terms acceptable to the Allies. His own comments at the conference of senior statesmen gave no hint that he favored any early cessation of the war ... Suzuki's selections for the most critical cabinet posts were, with one exception, not advocates of peace either.

After the war, Suzuki and others from his government and their apologists claimed they were secretly working towards peace, and could not publicly advocate it. They cite the Japanese concept of haragei—"the art of hidden and invisible technique"—to justify the dissonance between their public actions and alleged behind-the-scenes work. However, many historians reject this. Robert J. C. Butow

Robert Butow

Robert Joseph Charles Butow is a professor emeritus of Japanese history at the University of Washington in Seattle. An author of several books, he is a leading authority on Japan during World War II....

wrote:

- Because of its very ambiguity, the plea of haragei invites the suspicion that in questions of politics and diplomacy a conscious reliance upon this 'art of bluff' may have constituted a purposeful deception predicated upon a desire to play both ends against the middle. While this judgment does not accord with the much-lauded character of Admiral Suzuki, the fact remains that from the moment he became Premier until the day he resigned no one could ever be quite sure of what Suzuki would do or say next.

Japanese leaders had always envisioned a negotiated settlement to the war. Their prewar planning expected a rapid expansion, consolidation, eventual conflict with the United States, and then a settlement in which they would be able to retain at least some of the new territory they had conquered. By 1945, Japan's leaders were in agreement that the war was going badly, but they disagreed over the best means to negotiate an end to it. There were two camps: the so-called "peace" camp favored a diplomatic initiative to persuade Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, the leader of the Soviet Union, to mediate a settlement between the Allies and Japan; and the hardliners who favored fighting one last "decisive" battle that would inflict so many casualties on the Allies that they would be willing to offer more lenient terms. Both approaches were based on Japan's experience in the Russo–Japanese War, forty years earlier, which consisted of a series of costly but largely indecisive battles, followed by the decisive naval Battle of Tsushima

Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima , commonly known as the “Sea of Japan Naval Battle” in Japan and the “Battle of Tsushima Strait”, was the major naval battle fought between Russia and Japan during the Russo-Japanese War...

.

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

into a 40-page dossier and given to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

on February 2, two days before the Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

. Reportedly, the dossier was dismissed by Roosevelt out of hand—the proposals all included the condition that the emperor's position would be assured, if possibly as a puppet ruler; whereas at this time the Allied policy was to accept only an unconditional surrender

Unconditional surrender

Unconditional surrender is a surrender without conditions, in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. In modern times unconditional surrenders most often include guarantees provided by international law. Announcing that only unconditional surrender is acceptable puts psychological...

. Additionally, these proposals were strongly opposed by the powerful military members of the Japanese government.

In February 1945, Prince Fumimaro Konoe

Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a politician in the Empire of Japan who served as the 34th, 38th and 39th Prime Minister of Japan and founder/leader of the Taisei Yokusankai.- Early life :...

gave Emperor Hirohito a memorandum analyzing the situation, and told him that if the war continued, the imperial family

Imperial House of Japan

The , also referred to as the Imperial Family or the Yamato Dynasty, comprises those members of the extended family of the reigning Emperor of Japan who undertake official and public duties. Under the present Constitution of Japan, the emperor is the symbol of the state and unity of the people...

might be in greater danger from an internal revolution than from defeat. According to the diary of Grand Chamberlain

Chamberlain of Japan

The is a domestic caretaker and aide of the Emperor of Japan. He also keeps the Privy Seal and the State Seal and has been an official civil servant since the Meiji Period. Today the Grand Chamberlain, assisted by a Vice-Grand Chamberlain, heads the Board of the Chamberlains, the division of the...

Hisanori Fujita

Hisanori Fujita

was a Japanese naval officer, and after retiring from the navy was an assistant to the Emperor of Japan during World War II.Fujita graduated from the Japanese Naval Staff College, and became Commander of the Japanese battleship Kirishima on December 1, 1924. In 1929, he attained the rank of...

, the emperor, looking for a decisive battle (tennōzan), replied that it was premature to seek peace, "unless we make one more military gain". Also in February, Japan's treaty division wrote about Allied policies towards Japan regarding "unconditional surrender, occupation, disarmament, elimination of militarism, democratic reforms, punishment of war criminals, and the status of the emperor." Allied-imposed disarmament, Allied punishment of Japanese war criminals and especially occupation and removal of the emperor were not acceptable to the Japanese leadership.

On April 5, the Soviet Union gave the required 12 months' notice that it would not renew the five-year Soviet–Japanese Neutrality PactDeclaration Regarding Mongolia, April 13, 1941. (Avalon Project

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library....

at Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

) (which had been signed in 1941 following the Nomonhan Incident

Battle of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhyn Gol was the decisive engagement of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese Border Wars fought among the Soviet Union, Mongolia and the Empire of Japan in 1939. The conflict was named after the river Khalkhyn Gol, which passes through the battlefield...

), when it expired. Unknown to the Japanese, at the Tehran Conference

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference was the meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill between November 28 and December 1, 1943, most of which was held at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. It was the first World War II conference amongst the Big Three in which Stalin was present...

in November–December 1943, it had been agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once Nazi Germany was defeated. At the Yalta conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

in February 1945, the Americans had made substantial concessions to the Soviets to secure a promise that they would declare war on Japan within three months of the surrender of Germany. Although the five-year Neutrality Pact did not expire until April 5, 1946, the announcement caused the Japanese great concern. Molotov, in Moscow, and Malik, Soviet ambassador in Tokyo, went to great lengths to assure the Japanese that "The period of the Pact's validity has not ended".

Naotake Sato

was a Japanese diplomat and politician. He was born at Osaka. He graduated from the Tokyo Higher Commercial School in 1904, attended the consul course of the same institute, and quit studying there in 1905.- Home political career :He was an active politician and diplomat...

in Moscow, only Foreign minister Tōgō realized the possibility that Roosevelt and Churchill may already have made concessions to Stalin to bring the Soviets into the war against Japan. As a result of these meetings, Tōgō was authorized to approach the Soviet Union, seeking to maintain its neutrality, or (despite the very remote probability) to form an alliance.

In keeping with the custom of a new government declaring its purposes, following the May meetings the Army staff produced a document, "The Fundamental Policy to Be Followed Henceforth in the Conduct of the War," which stated that the Japanese people would fight to extinction rather than surrender. This policy was adopted by the Big Six on June 6. (Tōgō opposed it, while the other five supported it.) Documents submitted by Suzuki at the same meeting suggested that, in the diplomatic overtures to the USSR, Japan adopt the following approach:

It should be clearly made known to Russia that she owes her victory over Germany to Japan, since we remained neutral, and that it would be to the advantage of the Soviets to help Japan maintain her international position, since they have the United States as an enemy in the future.

On June 9, the emperor's confidant Marquis Kōichi Kido

Koichi Kido

Marquis served as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal from 1940 to 1945, and was the closest advisor to Emperor Showa throughout World War II.Kido was the grandson of Kido Takayoshi, one of the leaders of the Meiji Restoration...

wrote a "Draft Plan for Controlling the Crisis Situation," warning that by the end of the year Japan's ability to wage modern war would be extinguished and the government would be unable to contain civil unrest. "... We cannot be sure we will not share the fate of Germany and be reduced to adverse circumstances under which we will not attain even our supreme object of safeguarding the Imperial Household and preserving the national polity." Kido proposed that the emperor take action, by offering to end the war on "very generous terms." Kido proposed that Japan give up occupied European colonies, provided they were granted independence, and that the nation disarm and for a time be "content with minimum defense." With the emperor's authorization, Kido approached several members of the Supreme Council

Supreme War Council (Japan)

The Supreme War Council was established during the development of representative government in Meiji period Japan to further strengthen the authority of the state. Its first leader was Yamagata Aritomo , a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to...

, the "Big Six." Tōgō was very supportive. Suzuki and Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai

Mitsumasa Yonai

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, and politician. He was the 37th Prime Minister of Japan from 16 January to 22 July 1940.-Early life & Naval career:...

, the Navy minister

Ministry of the Navy of Japan

The was a cabinet-level ministry in the Empire of Japan charged with the administrative affairs of the Imperial Japanese Navy . It existed from 1872 to 1945.-History:...

, were both cautiously supportive; each wondered what the other thought. General Korechika Anami, the Army minister

Ministry of War of Japan

The , more popularly known as the Ministry of War of Japan, was cabinet-level ministry in the Empire of Japan charged with the administrative affairs of the Imperial Japanese Army...

, was ambivalent, insisting that diplomacy must wait until "after the United States has sustained heavy losses" in Ketsugō.

In June, the emperor lost confidence in the chances of achieving a military victory. The Battle of Okinawa

Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War of World War II. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June 1945...

was lost, and he learned of the weakness of the Japanese army in China, of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria, of the navy, and of the army defending the Home Islands. The emperor received a report by Prince Higashikuni from which he concluded that "it was not just the coast defense; the divisions reserved to engage in the decisive battle also did not have sufficient numbers of weapons." According to the Emperor:

I was told that the iron from bomb fragments dropped by the enemy was being used to make shovels. This confirmed my opinion that we were no longer in a position to continue the war.

On June 22, the emperor summoned the Big Six to a meeting. Unusually, he spoke first: "I desire that concrete plans to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and that efforts made to implement them." It was agreed to solicit Soviet aid in ending the war. Other neutral nations, such as Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

, Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, and the Vatican City

Vatican City

Vatican City , or Vatican City State, in Italian officially Stato della Città del Vaticano , which translates literally as State of the City of the Vatican, is a landlocked sovereign city-state whose territory consists of a walled enclave within the city of Rome, Italy. It has an area of...

, were known to be willing to play a role in making peace, but they were so small they were believed unable to do more than deliver the Allies' terms of surrender and Japan's acceptance or rejection. The Japanese hoped that the Soviet Union could be persuaded to act as an agent for Japan in negotiations with America and Britain.

Attempts to deal with the Soviet Union

On June 30, Tōgō told Naotake SatōNaotake Sato

was a Japanese diplomat and politician. He was born at Osaka. He graduated from the Tokyo Higher Commercial School in 1904, attended the consul course of the same institute, and quit studying there in 1905.- Home political career :He was an active politician and diplomat...

, Japan's ambassador in Moscow, to try to establish "firm and lasting relations of friendship." Satō was to discuss the status of Manchuria and "any matter the Russians would like to bring up." The Soviets were well aware of the situation and of their promises to the Allies, and they employed delaying tactics to encourage the Japanese without promising anything. Satō finally met with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

on July 11, but without result. On July 12, Tōgō directed Satō to tell the Soviets that:

His Majesty the Emperor, mindful of the fact that the present war daily brings greater evil and sacrifice upon the peoples of all the belligerent powers, desires from his heart that it may be quickly terminated. But so long as England and the United States insist upon unconditional surrender, the Japanese Empire has no alternative but to fight on with all its strength for the honor and existence of the Motherland.

The emperor proposed sending Prince Konoe as a special envoy, although he would be unable to reach Moscow before the Potsdam Conference

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

.

Satō advised Tōgō that in reality, "unconditional surrender or terms closely equivalent thereto" was all that Japan could expect. Moreover, in response to Molotov's requests for specific proposals, Satō suggested that Tōgō's messages were not "clear about the views of the Government and the Military with regard to the termination of the war," thus questioning whether Tōgō's initiative was supported by the key elements of Japan's power structure.

On July 17, Tōgō responded:

Although the directing powers, and the government as well, are convinced that our war strength still can deliver considerable blows to the enemy, we are unable to feel absolutely secure peace of mind ... Please bear particularly in mind, however, that we are not seeking the Russians' mediation for anything like an unconditional surrender.

In reply, Satō clarified:

It goes without saying that in my earlier message calling for unconditional surrender or closely equivalent terms, I made an exception of the question of preserving [the imperial family].

On July 21, speaking in the name of the cabinet, Tōgō repeated:

With regard to unconditional surrender we are unable to consent to it under any circumstances whatever. ... It is in order to avoid such a state of affairs that we are seeking a peace, ... through the good offices of Russia. ... it would also be disadvantageous and impossible, from the standpoint of foreign and domestic considerations, to make an immediate declaration of specific terms.

American cryptographers had broken

Magic (cryptography)

Magic was an Allied cryptanalysis project during World War II. It involved the United States Army's Signals Intelligence Section and the United States Navy's Communication Special Unit. -Codebreaking:...

most of Japan's codes, including the Purple code used by the Japanese Foreign Office to encode high-level diplomatic correspondence. As a result, messages between Tokyo

Tokyo

, ; officially , is one of the 47 prefectures of Japan. Tokyo is the capital of Japan, the center of the Greater Tokyo Area, and the largest metropolitan area of Japan. It is the seat of the Japanese government and the Imperial Palace, and the home of the Japanese Imperial Family...

and Japan's embassies were provided to Allied policy-makers nearly as quickly as to the intended recipients.

Soviet intentions

Security concerns dominated Soviet decisions concerning the Far East. Chief among these was gaining unrestricted access to the Pacific OceanPacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

. The year-round ice-free areas of the Soviet Pacific coastline—Vladivostok

Vladivostok

The city is located in the southern extremity of Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, which is about 30 km long and approximately 12 km wide.The highest point is Mount Kholodilnik, the height of which is 257 m...

in particular—could be blockaded by air and sea from Sakhalin island and the Kurile Islands. Acquiring these territories, thus guaranteeing free access to the Soya Strait, was their primary objective. Secondary objectives were leases for the Chinese Eastern Railway

Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or was a railway in northeastern China . It connected Chita and the Russian Far East. English-speakers have sometimes referred to this line as the Manchurian Railway...

, Southern Manchuria Railway, Dairen, and Port Arthur.

To this end, Stalin and Molotov strung out the negotiations with the Japanese, giving them false hope of a Soviet-mediated peace. At the same time, in their dealings with the United States and Britain, the Soviets insisted on strict adherence to the Cairo Declaration

Cairo Declaration

The Cairo Declaration was the outcome of the Cairo Conference in Cairo, Egypt, on November 27, 1943. President Franklin Roosevelt of the United States, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China were present...

, re-affirmed at the Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

, that the Allies would not accept separate or conditional peace with Japan. The Japanese would have to surrender unconditionally to all the Allies. To prolong the war, the Soviets opposed any attempt to weaken this requirement. This would give the Soviets time to complete the transfer of their troops from the Western Front to the Far East, and conquer Manchuria (Manchukuo

Manchukuo

Manchukuo or Manshū-koku was a puppet state in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, governed under a form of constitutional monarchy. The region was the historical homeland of the Manchus, who founded the Qing Empire in China...

), Inner Mongolia (Mengjiang

Mengjiang

Mengjiang , also known in English as Mongol Border Land, was an autonomous area in Inner Mongolia, operating under nominal Chinese sovereignty and Japanese control. It consisted of the then-Chinese provinces of Chahar and Suiyuan, corresponding to the central part of modern Inner Mongolia...

), Korea, Sakhalin, the Kuriles, and possibly, Hokkaidō

Hokkaido

, formerly known as Ezo, Yezo, Yeso, or Yesso, is Japan's second largest island; it is also the largest and northernmost of Japan's 47 prefectural-level subdivisions. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaido from Honshu, although the two islands are connected by the underwater railway Seikan Tunnel...

(starting with a landing at Rumoi

Rumoi, Hokkaido

is a city located in Rumoi, Hokkaidō, Japan. It is the capital of Rumoi Subprefecture.As of 2008, the city has an estimated population of 26,017 and the density of 87.5 persons per km². The total area is 297.44 km².The city was founded on October 1, 1947....

).

Manhattan Project

In 1939, Albert EinsteinAlbert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

and Leó Szilárd

Leó Szilárd

Leó Szilárd was an Austro-Hungarian physicist and inventor who conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear reactor with Enrico Fermi, and in late 1939 wrote the letter for Albert Einstein's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb...

wrote a letter to President Roosevelt urging him to fund research and development of atomic bombs. Roosevelt agreed, and the result was the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

—a top-secret research program administered by General Leslie Groves

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr. was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb during World War II. As the son of a United States Army chaplain, Groves lived at a...

, with scientific direction from J. Robert Oppenheimer. The first bomb was tested successfully in the Trinity explosion on July 16, 1945.

As the project neared its conclusion, American planners began to consider the use of the bomb. Groves formed a committee that met in April and May 1945 to draw up a list of targets. One of the primary criteria was that the target cities must not have been damaged by conventional bombing. This would allow for an accurate assessment of the damage done by the atomic bomb.

The targeting committee's list included 18 Japanese cities. At the top of the list were Kyoto

Kyoto

is a city in the central part of the island of Honshū, Japan. It has a population close to 1.5 million. Formerly the imperial capital of Japan, it is now the capital of Kyoto Prefecture, as well as a major part of the Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto metropolitan area.-History:...

, Hiroshima, Yokohama

Yokohama

is the capital city of Kanagawa Prefecture and the second largest city in Japan by population after Tokyo and most populous municipality of Japan. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of Tokyo, in the Kantō region of the main island of Honshu...

, Kokura

Kokura

is an ancient castle town and the center of Kitakyūshū, Japan, guarding, via its suburb Moji, the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshū and Kyūshū. Kokura is also the name of the penultimate station on the southbound Sanyo Shinkansen line, which is owned by JR Kyūshū and an important part of the...

, and Niigata

Niigata, Niigata

is the capital and the most populous city of Niigata Prefecture, Japan. It lies on the northwest coast of Honshu, the largest island of Japan, and faces the Sea of Japan and Sado Island....

. Ultimately, Kyoto was removed from the list at the insistence of Secretary of War

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

Henry L. Stimson

Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson was an American statesman, lawyer and Republican Party politician and spokesman on foreign policy. He twice served as Secretary of War 1911–1913 under Republican William Howard Taft and 1940–1945, under Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the latter role he was a leading hawk...

, who had visited the city on his honeymoon and knew of its cultural and historical significance.

In May, Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

(who had become president upon Franklin Roosevelt's death on April 12) approved the formation of an "Interim Committee"

Interim Committee

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on matters pertaining to nuclear energy...

, an advisory group that would report on the atomic bomb. It consisted of George L. Harrison

George L. Harrison

George Leslie Harrison was an American banker, insurance executive and advisor to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson during World War II....

, Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush was an American engineer and science administrator known for his work on analog computing, his political role in the development of the atomic bomb as a primary organizer of the Manhattan Project, the founding of Raytheon, and the idea of the memex, an adjustable microfilm viewer...

, James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant was a chemist, educational administrator, and government official. As thePresident of Harvard University he reformed it as a research institution.-Biography :...

, Karl Taylor Compton

Karl Taylor Compton

Karl Taylor Compton was a prominent American physicist and president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1930 to 1948.- The early years :...

, William L. Clayton

William L. Clayton

William Lockhart "Will" Clayton was an American business leader and government official.-Early life and career:...

, and Ralph Austin Bard

Ralph Austin Bard

Ralph Austin Bard was a Chicago financier who served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1941–1944, and as Under Secretary, 1944–1945. He is noted for a memorandum he wrote to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson in 1945 urging that Japan be given a warning before the use of the atomic...

, advised by scientists Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi was an Italian-born, naturalized American physicist particularly known for his work on the development of the first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and for his contributions to the development of quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics...

, Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was an American physicist and Nobel Laureate, known for his invention, utilization, and improvement of the cyclotron atom-smasher beginning in 1929, based on his studies of the works of Rolf Widerøe, and his later work in uranium-isotope separation for the Manhattan Project...

, and Arthur Compton

Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton was an American physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his discovery of the Compton effect. He served as Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis from 1945 to 1953.-Early years:...

. In a June 1 report, the Committee concluded that the bomb should be used as soon as possible against a war plant surrounded by worker's homes, and that no warning or demonstration should be given.

The Committee's mandate did not include the use of the bomb—its use upon completion was presumed. Following a protest by scientists involved in the project, in the form of the Franck Report

Franck Report

The Franck Report of June 1945 was a document signed by several prominent nuclear physicists recommending that the United States not use the atomic bomb as a weapon to prompt the surrender of Japan in World War II....

, the Committee re-examined the use of the bomb. In a June 21 meeting, it reaffirmed that there was no alternative.

Events at Potsdam

The leaders of the major Allied powers met at the Potsdam ConferencePotsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

from July 16 to August 2, 1945. The participants were the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, represented by Stalin, Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

(later Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

), and Truman respectively.

Negotiations

Although the Potsdam Conference was mainly concerned with European affairs, the war against Japan was also discussed in detail. Truman learned of the successful Trinity test early in the conference, and shared this information with the British delegation. The successful test caused the American delegation to reconsider the necessity and wisdom of Soviet participation, for which the U.S. had lobbied hard at the TehranTehran Conference

The Tehran Conference was the meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill between November 28 and December 1, 1943, most of which was held at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. It was the first World War II conference amongst the Big Three in which Stalin was present...

and Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

s. High on the Americans' list of priorities was shortening the war and reducing American casualties—Soviet intervention seemed likely to do both, but at the cost of possibly allowing the Soviets to capture territory beyond that which had been promised to them at Tehran and Yalta, and causing a postwar division of Japan similar to that which had occurred in Germany

Allied Occupation Zones in Germany

The Allied powers who defeated Nazi Germany in World War II divided the country west of the Oder-Neisse line into four occupation zones for administrative purposes during 1945–49. In the closing weeks of fighting in Europe, US forces had pushed beyond the previously agreed boundaries for the...

.

In dealing with Stalin, Truman decided to give the Soviet leader vague hints about the existence of a powerful new weapon without going into details. The Allies were unaware that Soviet intelligence had penetrated the Manhattan Project in its early stages, so Stalin already knew of the existence of the atomic bomb, but did not appear impressed by its potential.

The Potsdam Declaration

It was decided to issue a statement, the Potsdam DeclarationPotsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender is a statement calling for the Surrender of Japan in World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S...

, defining "Unconditional Surrender" and clarifying what it meant for the position of the emperor and for Hirohito personally. The American and British governments strongly disagreed on this point—Americans wanted to abolish the position and possibly try him as a war criminal, while the British wanted to retain the position, perhaps with Hirohito still reigning. The Potsdam Declaration went through many drafts until a version acceptable to all was found.

On July 26, the United States, Britain and China released the Potsdam Declaration announcing the terms for Japan's surrender, with the warning, "We will not deviate from them. There are no alternatives. We shall brook no delay." For Japan, the terms of the declaration specified:

- the elimination "for all time [of] the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest"

- the occupation of "points in Japanese territory to be designated by the Allies"

- "Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of HonshūHonshuis the largest island of Japan. The nation's main island, it is south of Hokkaido across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyushu across the Kanmon Strait...

, HokkaidōHokkaido, formerly known as Ezo, Yezo, Yeso, or Yesso, is Japan's second largest island; it is also the largest and northernmost of Japan's 47 prefectural-level subdivisions. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaido from Honshu, although the two islands are connected by the underwater railway Seikan Tunnel...

, KyūshūKyushuis the third largest island of Japan and most southwesterly of its four main islands. Its alternate ancient names include , , and . The historical regional name is referred to Kyushu and its surrounding islands....

, ShikokuShikokuis the smallest and least populous of the four main islands of Japan, located south of Honshū and east of the island of Kyūshū. Its ancient names include Iyo-no-futana-shima , Iyo-shima , and Futana-shima...

and such minor islands as we determine." As had been announced in the Cairo DeclarationCairo DeclarationThe Cairo Declaration was the outcome of the Cairo Conference in Cairo, Egypt, on November 27, 1943. President Franklin Roosevelt of the United States, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China were present...

in 1943, Japan was to be reduced to her pre-1894 territory and stripped of her pre-war empire including KoreaKoreaKorea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

and TaiwanTaiwanTaiwan , also known, especially in the past, as Formosa , is the largest island of the same-named island group of East Asia in the western Pacific Ocean and located off the southeastern coast of mainland China. The island forms over 99% of the current territory of the Republic of China following...

, as well as all her recent conquests. - "The Japanese military forces shall be completely disarmed"

- "stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners"

- "We do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation, ... The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speechFreedom of speechFreedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship. The term freedom of expression is sometimes used synonymously, but includes any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used...

, of religionFreedom of religionFreedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

, and of thoughtFreedom of thoughtFreedom of thought is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints....

, as well as respect for the fundamental human rightsHuman rightsHuman rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...

shall be established." - "Japan shall be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind, ... Japanese participation in world trade relations shall be permitted."

- "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government.

Contrary to popular belief, the only use of the term "unconditional surrender" came at the end of the declaration:

- "We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction."

Contrary to what had been intended at its conception, the Declaration made no mention of the emperor at all. Allied intentions on issues of utmost importance to the Japanese, including whether Hirohito was to be regarded as one of those who had "misled the people of Japan" or even a war criminal, or alternatively, whether the emperor might become part of a "peacefully inclined and responsible government" were thus left unstated.

The "prompt and utter destruction" clause has been interpreted as a veiled warning about American possession of the atomic bomb (which had been tested successfully on the first day of the conference).

Japanese reaction

On July 27, the Japanese government considered how to respond to the Declaration. The four military members of the Big Six wanted to reject it, but Tōgō persuaded the cabinet not to do so until he could get a reaction from the Soviets. In a telegram, Shun'ichi Kase, Japan's ambassador to Switzerland, observed that "unconditional surrender" applied only to the military and not to the government or the people, and he pleaded that it should be understood that the careful language of Potsdam appeared "to have occasioned a great deal of thought" on the part of the signatory governments—"they seem to have taken pains to save faceFace (sociological concept)

Face, idiomatically meaning dignity/prestige, is a fundamental concept in the fields of sociology, sociolinguistics, semantics, politeness theory, psychology, political science, communication, and Face Negotiation Theory.-Definitions:...

for us on various points." The next day, Japanese newspapers reported that the Declaration, the text of which had been broadcast and dropped by leaflet

Airborne leaflet propaganda

Airborne leaflet propaganda is a form of psychological warfare in which leaflets are scattered in the air. Military forces have used aircraft to drop leaflets to alter the behavior of people in enemy-controlled territory, sometimes in conjunction with air strikes...

into Japan, had been rejected. In an attempt to manage public perception, Prime Minister Suzuki met with the press, and stated:

I consider the Joint Proclamation a rehash of the Declaration at the Cairo Conference. As for the Government, it does not attach any important value to it at all. The only thing to do is just kill it with silence (mokusatsu). We will do nothing but press on to the bitter end to bring about a successful completion of the war.

The meaning of mokusatsu

Mokusatsu

is a Japanese word meaning "to ignore" or "to treat with silent contempt". It is composed of two kanji: and . The government of Japan used the term as a response to Allied demands in the Potsdam Declaration for unconditional surrender in World War II, which influenced President Harry S...

, literally "kill with silence," can range from "ignore" to "treat with contempt"—which fairly accurately described the range of reactions within the government. But Suzuki's statement, particularly its final sentence, leaves little room for misinterpretation and was taken as a rejection by the press, both in Japan and abroad, and no further statement was made in public or through diplomatic channels to alter this understanding.

On July 30, Ambassador Satō wrote that Stalin was probably talking to Roosevelt and Churchill about his dealings with Japan, and he wrote: "There is no alternative but immediate unconditional surrender if we are to prevent Russia's participation in the war." On August 2, Tōgō wrote to Satō: "it should not be difficult for you to realize that ... our time to proceed with arrangements of ending the war before the enemy lands on the Japanese mainland is limited, on the other hand it is difficult to decide on concrete peace conditions here at home all at once."

August 6: Hiroshima

On the morning of August 6, the Enola GayEnola Gay

Enola Gay is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, mother of the pilot, then-Colonel Paul Tibbets. On August 6, 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb as a weapon of war...

, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force, best known for being the pilot of the Enola Gay, the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in the history of warfare. The bomb, code-named Little Boy, was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima...

, dropped an atomic bomb

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

(code-named Little Boy

Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the codename of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, of the United States Army Air Forces. It was the first atomic bomb to be used as a weapon...

by the Americans) on the city of Hiroshima

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture, and the largest city in the Chūgoku region of western Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It became best known as the first city in history to be destroyed by a nuclear weapon when the United States Army Air Forces dropped an atomic bomb on it at 8:15 A.M...

in southwest Honshū. Throughout the day, confused reports reached Tokyo that Hiroshima had been the target of an air raid, which had leveled the city with a "blinding flash and violent blast". Later that day, they received U.S. President Truman's broadcast announcing the first use of an atomic bomb, and promising:

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth...

At first, some refused to believe the Americans had built an atomic bomb. The Japanese Army and Navy had their own independent atomic-bomb programs and therefore the Japanese understood enough to know how very difficult building it would be. Admiral Soemu Toyoda, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, argued that even if the Americans had made one, they could not have many more. American strategists, having anticipated a reaction like Toyoda's, planned to drop a second bomb shortly after the first, to convince the Japanese that the U.S. had a large supply.

August 8–9: Soviet invasion and Nagasaki

Detailed reports of the unprecedented scale of the destruction at Hiroshima were received in Tokyo, but two days passed before the government met to consider the changed situation.At 04:00 on August 9 word reached Tokyo that the Soviet Union had broken the Neutrality Pact, declared war on Japan, and launched an invasion of Manchuria.

Imperial Japanese Army

-Foundation:During the Meiji Restoration, the military forces loyal to the Emperor were samurai drawn primarily from the loyalist feudal domains of Satsuma and Chōshū...

took the news in stride, grossly underestimating the scale of the attack. With the support of Minister of War Anami, they did start preparing to impose martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

on the nation, to stop anyone attempting to make peace. Hirohito

Hirohito

, posthumously in Japan officially called Emperor Shōwa or , was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989. Although better known outside of Japan by his personal name Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to...

told Kido

Koichi Kido

Marquis served as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal from 1940 to 1945, and was the closest advisor to Emperor Showa throughout World War II.Kido was the grandson of Kido Takayoshi, one of the leaders of the Meiji Restoration...

to "quickly control the situation" because "the Soviet Union has declared war and today began hostilities against us."

The Supreme Council met at 10:30. Suzuki, who had just come from a meeting with the emperor, said it was impossible to continue the war. Tōgō Shigenori said that they could accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration but needed a guarantee of the emperor's position. Navy Minister Yonai said that they had to make some diplomatic proposal—they could no longer afford to wait for better circumstances.

In the middle of the meeting, shortly after 11:00, news arrived that Nagasaki

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan. Nagasaki was founded by the Portuguese in the second half of the 16th century on the site of a small fishing village, formerly part of Nishisonogi District...

, on the west coast of Kyūshū, had been hit by a second atomic bomb (called "Fat Man

Fat Man

"Fat Man" is the codename for the atomic bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, by the United States on August 9, 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons to be used in warfare to date , and its detonation caused the third man-made nuclear explosion. The name also refers more...

" by the Americans). By the time the meeting ended, the Big Six had split 3–3. Suzuki, Tōgō, and Admiral Yonai favored Tōgō's one additional condition to Potsdam, while Generals Anami, Umezu, and Admiral Toyoda insisted on three further terms that modified Potsdam: that Japan handle their own disarmament, that Japan deal with any Japanese war criminals, and that there be no occupation of Japan.

Imperial intervention, Allied response, and Japanese reply

The full cabinet met on 14:30 on August 9, and spent most of the day debating surrender. As the Big Six had done, the cabinet split, with neither Tōgō's position nor Anami's attracting a majority. Anami told the other cabinet ministers that, under torture, a captured American B-29 pilot had told his interrogators that the Americans possessed 100 atom bombs and that Tokyo and Kyoto would be bombed "in the next few days". The pilot, Marcus McDilda, was lying. He knew nothing of the Manhattan ProjectManhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

, and simply told his interrogators what he thought they wanted to hear to end the torture. The lie, which caused him to be classified as a high-priority prisoner, probably saved him from beheading. In reality, the United States would have had the third bomb ready for use around August 19, and a fourth in September 1945. The third bomb probably would have been used against Tokyo.

The cabinet meeting adjourned at 17:30 with no consensus. A second meeting lasting from 18:00 to 22:00 also ended with no consensus. Following this second meeting, Suzuki and Tōgō met the emperor, and Suzuki proposed an impromptu Imperial conference

Gozen Kaigi

was an extraconstitutional conference of matters of grave national importance in foreign affairs that were convened by the government of the Empire of Japan in the presence of the Emperor.-History and background:...

, which started just before midnight on the night of August 9–10. Suzuki presented Anami's four-condition proposal as the consensus position of the Supreme Council. The other members of the Supreme Council spoke, as did Kiichirō Hiranuma, the president of the Privy Council, who outlined Japan's inability to defend itself and also described the country's domestic problems, such as the shortage of food. The cabinet debated, but again no consensus emerged. At around 02:00 (August 10), Suzuki finally addressed Emperor Hirohito, asking him to decide between the two positions. The participants later recollected that the emperor stated:

I have given serious thought to the situation prevailing at home and abroad and have concluded that continuing the war can only mean destruction for the nation and prolongation of bloodshed and cruelty in the world. I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer. ...