April 1946

Encyclopedia

January

– February

– March

- April – May

– June

– July

– August

– September

– October

– November

– December

The following events occurred in April

The following events occurred in April

, 1946:

January 1946

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1946.-January 1, 1946 :...

– February

February 1946

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in February 1946.-February 1, 1946 :...

– March

March 1946

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in March, 1946.-March 1, 1946 :...

- April – May

May 1946

January – February – March - April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in May, 1946:-May 1, 1946 :...

– June

June 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June, 1946:-June 1, 1946 :...

– July

July 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1946:-July 1, 1946 :...

– August

August 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1946:-August 1, 1946 :...

– September

September 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1946:-September 1, 1946 :...

– October

October 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1946:-October 1, 1946 :...

– November

November 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - November - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1946:-November 1, 1946 :...

– December

December 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November — DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1946:-December 1, 1946 :...

April

April is the fourth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars, and one of four months with a length of 30 days. April was originally the second month of the Roman calendar, before January and February were added by King Numa Pompilius about 700 BC...

, 1946:

April 1, 1946 (Monday)

- A tsunamiTsunamiA tsunami is a series of water waves caused by the displacement of a large volume of a body of water, typically an ocean or a large lake...

, generated by an 8.6 magnitude earthquake near AlaskaAlaskaAlaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

, killed 159 people in HawaiiHawaiiHawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

. Waves 25 feet high struck Hilo shortly after local time, and almost five hours after the Alaskan tremor. - Bituminous coalBituminous coalBituminous coal or black coal is a relatively soft coal containing a tarlike substance called bitumen. It is of higher quality than lignite coal but of poorer quality than Anthracite...

miners walked off the job across the United States, as 400,000 UMWA members went on strike in 26 states. The miners returned to work after six weeks. - As part of Operation Road's End, the United States Navy destroyed and sank 24 Japanese submarines that had been surrendered at the end of World War II. Twenty-tree were blown up with demolition charges. The I-402, which had sunk the USS IndianapolisUSS Indianapolis (CA-35)USS Indianapolis was a of the United States Navy. She holds a place in history due to the circumstances of her sinking, which led to the greatest single loss of life at sea in the history of the U.S. Navy...

, was destroyed by shellfire. - The United Kingdom made SingaporeSingaporeSingapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

a Crown colony, separating the predominantly Chinese population from the rest of the Union of Malaya. - The United States Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari on an appeal from the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in Chapman v. King, et al. 154 F.2d 460 (5th Cir. 1946), which held that African-Americans could not be barred from voting in primary elections in GeorgiaGeorgia (U.S. state)Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

. At the time, the Democratic Party was the dominant political party in Georgia and other Southern states in the Fifth Circuit, and the winner of the Democratic primary was frequently unopposed in the general election. Primus E. King of Columbus, GeorgiaColumbus, GeorgiaColumbus is a city in and the county seat of Muscogee County, Georgia, United States, with which it is consolidated. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 189,885. It is the principal city of the Columbus, Georgia metropolitan area, which, in 2009, had an estimated population of 292,795...

, had commenced the suit in 1944, to challenge the practice of allowing political parties to set their own rules concerning who would be allowed to vote in a nominating election. The decision paved the way for allowing Negroes to vote in primary elections in other states. - Born: Robert Garwood, U.S. Marine and Vietnam POW, who was convicted in 1981 of collaboration with the enemy; in Greensburg, IN

- Died: Noah Beery, Sr.Noah Beery, Sr.Noah Nicholas Beery was an American actor, who appeared in films from 1913 to 1945.-Early life:His parents originally came from Switzerland. Beery was born in Kansas City, Missouri. He and his brothers William C. Beery and Wallace Beery became Hollywood actors...

, 64, American film actor; and Edward SheldonEdward SheldonEdward Brewster Sheldon was an American dramatist. His plays include Salvation Nell and Romance , which was made into a motion picture with Greta Garbo....

, 60, American playwright

April 2, 1946 (Tuesday)

- In Japan, General Douglas MacArthurDouglas MacArthurGeneral of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

, administrator of the American occupation, issued the first regulations against fraternizationFraternizationFraternization is "turning people into brothers"—conducting social relations with people who are actually unrelated and/or of a different class as though they were siblings, family members, personal friends or lovers....

between American soldiers and Japanese citizens. Originally intended to stop soldiers from consorting with prostitutes, the regulations soon provided for segregation in public transportation, food service and accommodation, with Japanese residents being barred from American facilities, and vice-versa. - Japanese storekeeper Katsumi Yanagisawa began the business of manufacturing music stands, which grew into the Pearl Musical Instrument Company, and eventually became Pearl DrumsPearl DrumsFounded in 1952, the is a multinational corporation based in Japan with a wide range of products, predominately percussion instruments.-History:Pearl was founded by Katsumi Yanagisawa, who began manufacturing music stands in Sumida, Tokyo on April 2, 1946...

. - Born: Yves "Apache" TrudeauYves "Apache" TrudeauYves "Apache" Trudeau , also known as "The Mad Bumper", is a Canadian former head of the Hells Angels North Chapter outlaw motorcycle gang in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Frustrated by cocaine addiction and his suspicion that his fellow gang members wanted him dead he became a government informant...

, Canadian murderer alleged to have killed 43 people for the Hell's Angels group. - Died: Kate BruceKate BruceKate Bruce was an American actress of the silent era. She appeared in 289 films between 1908 and 1931.She was born in Columbus, Indiana and died in New York, New York.-Selected filmography:* The Golden Louis...

, 88, silent screen actress, 1908–31

April 3, 1946 (Wednesday)

- An article, on the front page of the AmsterdamAmsterdamAmsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

newspaper Het ParoolHet ParoolHet Parool is an Amsterdam-based daily newspaper. It was founded as a resistance paper during World War II by Frans Van Heuven Goedhart and Jaap Nunes Vaz...

, brought the attention of publishers to the existence of a diary, written by a teenage girl who had died in a Nazi concentration camp. Historian Jan RomeinJan RomeinJan Marius Romein was a Dutch journalist and historian.Born in Rotterdam, Romein married the writer and historian Annie Romein-Verschoor on August 14, 1920.Romein began writing while a student in 1916...

wrote, under the headline "Kinderstem" ("A Child's Voice"), "[T]his apparently inconsequential diary by a child ... stammered out in a child's voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence at Nueremberg put together." Published in the Netherlands as 1947 as Het Archterhuis: Dagboekbrieven ("The Attic: Diary Notes"), the book would be translated into English in 1952 as Anne FrankAnne FrankAnnelies Marie "Anne" Frank is one of the most renowned and most discussed Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Acknowledged for the quality of her writing, her diary has become one of the world's most widely read books, and has been the basis for several plays and films.Born in the city of Frankfurt...

: The Diary of a Young GirlThe Diary of a Young GirlThe Diary of a Young Girl is a book of the writings from the Dutch language diary kept by Anne Frank while she was in hiding for two years with her family during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. The family was apprehended in 1944 and Anne Frank ultimately died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen...

. - Died: Lt.Gen. Masaharu HommaMasaharu Hommawas a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He is noteworthy for his role in the invasion and occupation of the Philippines during World War II. Homma, who was an amateur painter and playwright, was also known as the Poet General.-Biography:...

, Japanese general who ordered the Bataan death marchBataan Death MarchThe Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer, by the Imperial Japanese Army, of 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war after the three-month Battle of Bataan in the Philippines during World War II, which resulted in the deaths of thousands of prisoners.The march was characterized by...

, was executed in Manila by a U.S. Army firing squad.

April 4, 1946 (Thursday)

- The eleven nation Far Eastern CommissionFar Eastern CommissionIt was agreed at the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers, and made public in communique issued at the end of the conference on December 27, 1945 that the Far Eastern Advisory Commission would become the Far Eastern Commission , it would be based in Washington, and would oversee the Allied...

exempted Japan's Emperor HirohitoHirohito, posthumously in Japan officially called Emperor Shōwa or , was the 124th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989. Although better known outside of Japan by his personal name Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to...

from being tried for war crimes. - Nine U.S. Navy personnel, from the aircraft carrier USS TarawaUSS Tarawa (CV-40)USS Tarawa was one of 24 s built during and shortly after World War II for the United States Navy. The ship was the first US Navy ship to bear the name, and was named for the bloody 1943 Battle of Tarawa. Tarawa was commissioned in December 1945, too late to serve in World War II. After serving a...

, were killed while watching training exercises from an observation tower in Puerto Rico. One of the airplanes inadvertently released a bomb which made a direct hit on the tower. - Born: Dave HillDave HillDave Hill is an English musician, who is the lead guitarist and backing vocalist in the English glam rock group, Slade. The music journalist, Stuart Maconie, commented "he usually wore a jumpsuit made of the foil that you baste your turkeys in and platforms of oil-rig-derrick height...

, English guitarist (SladeSladeSlade are an English rock band from Wolverhampton, who rose to prominence during the glam rock era of the early 1970s. With 17 consecutive Top 20 hits and six number ones, the British Hit Singles & Albums names them as the most successful British group of the 1970s based on sales of singles...

), in HolbetonHolbetonHolbeton is a village located 9 miles south east of Plymouth in Devon, UK. Historically it formed part of Ermington Hundred. To the east of the village is an Iron age enclosure or Hill fort known as Holbury...

April 5, 1946 (Friday)

- The Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and IranIranIran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

announced a 25-year agreement to create a "Soviet-Persian Oil Company", with the U.S.S.R. to have 51% of Iran's oil rights in return for the withdrawal of Soviet troops. However, the treaty, subject to the approval of Iran's Majlis, was rejected in 1947. - By a 41–27 margin, the United States SenateUnited States SenateThe United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

approved increasing the 40¢/hour minimum wageMinimum wageA minimum wage is the lowest hourly, daily or monthly remuneration that employers may legally pay to workers. Equivalently, it is the lowest wage at which workers may sell their labour. Although minimum wage laws are in effect in a great many jurisdictions, there are differences of opinion about...

to 65¢ per hour. - Thirty-six years after it had been written, Charles IvesCharles IvesCharles Edward Ives was an American modernist composer. He is one of the first American composers of international renown, though Ives' music was largely ignored during his life, and many of his works went unperformed for many years. Over time, Ives came to be regarded as an "American Original"...

's Third SymphonySymphony No. 3 (Ives)The Symphony No. 3, S. 3 , The Camp Meeting by Charles Ives was written between the years of 1908 and 1910. In 1947, Ives was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his Symphony No. 3. Later, his works were performed by conductors like Leonard Bernstein...

was given its first public performance. In 1947, Ives would win a Pulitzer Prize for the 1910 symphony. - Born: Björn GranathBjörn GranathBjörn Gösta Tryggve Granath is a Swedish actor.Granath was born in Örgryte, Gothenburg, Sweden. He has starred in a broad range of films from comedies to dramas. He was active as an actor and director on the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm between the years 1987-2007...

, Swedish actor, in GothenburgGothenburgGothenburg is the second-largest city in Sweden and the fifth-largest in the Nordic countries. Situated on the west coast of Sweden, the city proper has a population of 519,399, with 549,839 in the urban area and total of 937,015 inhabitants in the metropolitan area... - Died: Vincent YoumansVincent YoumansVincent Youmans was an American popular composer and Broadway producer.- Life :Vincent Millie Youmans was born in New York City on September 27, 1898 and grew-up on Central Park West on the site where the Mayflower Hotel once stood. His father, a prosperous hat manufacturer, moved the family to...

, 45, American songwriter

April 6, 1946 (Saturday)

- Captain Hoshijima Susumu, Japanese commander of the Sandakan prisoner-of-war camp in IndonesiaIndonesiaIndonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

, was hanged for war crimes. Capt. Hoshijima had ordered the "Sandakan Death MarchesSandakan Death MarchesThe Sandakan Death Marches were a series of forced marches in Borneo from Sandakan to Ranau which resulted in the deaths of more than 3,600 Indonesian civilian slave labourers and 2,400 Allied prisoners of war held captive by the Empire of Japan during the Pacific campaign of World War II at prison...

" as the war approached a close in 1945. During his administration, nearly 6,000 prisoners died-- 4,000 Indonesians, 1,381 Australians and 641 British. - Acting on a tip from a geisha house, American officials unearthed two billion dollars worth of gold, silver and platinum that had been hidden in the muddy bottom of Tokyo BayTokyo Bayis a bay in the southern Kantō region of Japan. Its old name was .-Geography:Tokyo Bay is surrounded by the Bōsō Peninsula to the east and the Miura Peninsula to the west. In a narrow sense, Tokyo Bay is the area north of the straight line formed by the on the Miura Peninsula on one end and on...

. An officer of the Japanese Army had carried out the concealment of the precious metals in July 1945, shortly before the surrender of Japan.

April 7, 1946 (Sunday)

- Free elections were conducted in MilanMilanMilan is the second-largest city in Italy and the capital city of the region of Lombardy and of the province of Milan. The city proper has a population of about 1.3 million, while its urban area, roughly coinciding with its administrative province and the bordering Province of Monza and Brianza ,...

for the first time since 1922, when Benito MussoliniBenito MussoliniBenito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

had installed a Fascist regime, and 800,000 ballots were cast in voting for local councilmen. - Born: Colette BessonColette BessonColette Besson was a French athlete, the surprise winner of the 400 m at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.-Athletic career:...

, French athlete, 1968 Olympic gold in ; in Saint-Georges-de-DidonneSaint-Georges-de-DidonneSaint-Georges-de-Didonne is a commune in the Charente-Maritime department in southwestern France.-Population:-References:*...

(d. 2005); Zaid Abdul-AzizZaid Abdul-AzizZaid Abdul-Aziz is a retired American professional basketball player. Donald Smith changed his name to Zaid Abdul-Aziz in 1976. The 6'9" Abdul-Aziz starred at Iowa State University before being drafted by the NBA's Cincinnati Royals in 1968...

, American NBA player, as Donald A. Smith in BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

; and Léon KrierLéon KrierLéon Krier is an architect, architectural theorist and urban planner. From the late 1970s onwards Krier has been one of the most influential neo-traditional architects and planners...

, Luxembourgian architect

April 8, 1946 (Monday)

- In GenevaGenevaGeneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

, the League of NationsLeague of NationsThe League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, predecessor to the United NationsUnited NationsThe United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, opened its final session. - The Fort Wayne Zollner Pistons, who would later become the NBA's Detroit PistonsDetroit PistonsThe Detroit Pistons are a franchise of the National Basketball Association based in Auburn Hills, Michigan. The team's home arena is The Palace of Auburn Hills. It was originally founded in Fort Wayne, Indiana as the Fort Wayne Pistons as a member of the National Basketball League in 1941, where...

, won their third consecutive World Professional Basketball TournamentWorld Professional Basketball TournamentWorld Professional Basketball Tournament was an invitational tournament for professional basketball teams in the United States held in Chicago, Illinois by the Chicago Herald American. The annual event was held from 1939 to 1948...

, defeating the Oshkosh All-StarsOshkosh All-StarsThe Oshkosh All-Stars were a professional basketball team based in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. From 1937 to 1948 they played in the National Basketball League, a forerunner to the NBA. The team appeared in the NBL finals five consecutive years , winning twice...

73-57 to win the third and final game of the best-of-three series. - Two iconic films of 1946, Frank CapraFrank CapraFrank Russell Capra was a Sicilian-born American film director. He emigrated to the U.S. when he was six, and eventually became a creative force behind major award-winning films during the 1930s and 1940s...

's It's a Wonderful LifeIt's a Wonderful LifeIt's a Wonderful Life is a 1946 American Christmas drama film produced and directed by Frank Capra and based on the short story "The Greatest Gift" written by Philip Van Doren Stern....

and William WylerWilliam WylerWilliam Wyler was a leading American motion picture director, producer, and screenwriter.Notable works included Ben-Hur , The Best Years of Our Lives , and Mrs. Miniver , all of which won Wyler Academy Awards for Best Director, and also won Best Picture...

's The Best Years of Our LivesThe Best Years of Our LivesThe Best Years of Our Lives is a 1946 American drama film directed by William Wyler, and starring Fredric March, Myrna Loy, Dana Andrews, Teresa Wright, and Harold Russell, a United States paratrooper who lost both hands in a military training accident. The film is about three United States...

, began filming on the same day. - Électricité de FranceÉlectricité de FranceÉlectricité de France S.A. is the second largest French utility company. Headquartered in Paris, France, with €65.2 billion in revenues in 2010, EDF operates a diverse portfolio of 120,000+ megawatts of generation capacity in Europe, Latin America, Asia, the Middle East and Africa.EDF is one of...

(EDF) was created, as the French government nationalized the electric industry in that nation, formerly handled by more than 1,450 firms. - Ethiopian AirlinesEthiopian AirlinesEthiopian Airlines , formerly Ethiopian Air Lines, often referred to as simply Ethiopian, is an airline headquartered on the grounds of Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. It serves as the country's flag carrier, and is wholly owned by the Government of Ethiopia...

, now one of the largest airlines in Africa, began its first service, with a flight between Addis AbabaAddis AbabaAddis Ababa is the capital city of Ethiopia...

and CairoCairoCairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

. - Born: Robert L. JohnsonRobert L. JohnsonRobert L. Johnson is an American business magnate best known for being the founder of television network Black Entertainment Television , and is also its former chairman and chief executive officer...

, the first African-American billionaire and founder of Black Entertainment TelevisionBlack Entertainment TelevisionBlack Entertainment Television is an American, Viacom-owned cable network based in Washington, D.C.. Currently viewed in more than 90 million homes worldwide, it is the most prominent television network targeting young Black-American audiences. The network was launched on January 25, 1980, by its...

(BET), in Hickory, MS; and Jim "Catfish" Hunter, American MLB pitcher, in Hertford, NC (d.1999) - Died: Qin BangxianQin BangxianQin Bangxian or better known as Bo Gu was a senior leader of the Chinese Communist Party in its early stages, and well-known as a member of the group of 28 Bolsheviks.-Biography:...

, 39, General Secretary of the Communist Party of ChinaGeneral Secretary of the Communist Party of ChinaThe General Secretary of the Communist Party of China , officially General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, is the highest ranking official within the Communist Party of China, a standing member of the Politburo and head of the Secretariat...

1932–35, Ye TingYe TingYe Ting , born in Huiyang, Guangdong, was a Chinese military leader. He started out nationalist and went to the communists....

, Bo Gu, Deng FaDeng FaDeng Fa was a Chinese Communist politician who was the fifth president of the Party School of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, the highest training center for party workers and leaders. Deng served as principal from 1939 to 1942.-External links:*...

and others in a plane crash while en route from ChongqingChongqingChongqing is a major city in Southwest China and one of the five national central cities of China. Administratively, it is one of the PRC's four direct-controlled municipalities , and the only such municipality in inland China.The municipality was created on 14 March 1997, succeeding the...

to Yan'anYan'anYan'an , is a prefecture-level city in the Shanbei region of Shaanxi province in China, administering several counties, including Zhidan County , which served as the Chinese communist capital before the city of Yan'an proper took that role....

.

April 9, 1946 (Tuesday)

- The Montreal CanadiensMontreal CanadiensThe Montreal Canadiens are a professional ice hockey team based in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. They are members of the Northeast Division of the Eastern Conference of the National Hockey League . The club is officially known as ...

won the Stanley CupStanley CupThe Stanley Cup is an ice hockey club trophy, awarded annually to the National Hockey League playoffs champion after the conclusion of the Stanley Cup Finals. It has been referred to as The Cup, Lord Stanley's Cup, The Holy Grail, or facetiously as Lord Stanley's Mug...

, defeating the Boston BruinsBoston BruinsThe Boston Bruins are a professional ice hockey team based in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. They are members of the Northeast Division of the Eastern Conference of the National Hockey League . The team has been in existence since 1924, and is the league's third-oldest team and its oldest in the...

6–3 to win the series in five games. - Angkatan Udara Republik Indonesia (AURI), the Indonesian Air ForceIndonesian Air ForceThe Indonesian Air Force is the air force branch of the Indonesian National Armed Forces.The Indonesian Air Force has 34,930 personnel equipped with 110 combat aircraft including Su-27 and Su-30.-Before Indonesian independence :...

, was formally established, drawing primarily from a fleet of about 50 captured Japanese airplanes. - The University of BergenUniversity of BergenThe University of Bergen is located in Bergen, Norway. Although founded as late as 1946, academic activity had taken place at Bergen Museum as far back as 1825. The university today serves more than 14,500 students...

was founded in NorwayNorwayNorway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

.

April 10, 1946 (Wednesday)

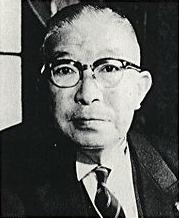

- Japanese general election, 1946Japanese general election, 1946General elections were held in Japan on 10 April 1946, the first after World War II. Voters had one, two or three votes, depending on how many MPs were elected from their constituency. The result was a victory for the Liberal Party, which won 148 of the 464 seats. Voter turnout was 72.1%-Results:...

: In that nation's first election since the end of World War II (and the first since 1942 and first multiparty vote since 1932), women were allowed to vote for the first time as 2,770 candidates vied for 464 seats in the House of Representatives of JapanHouse of Representatives of JapanThe is the lower house of the Diet of Japan. The House of Councillors of Japan is the upper house.The House of Representatives has 480 members, elected for a four-year term. Of these, 180 members are elected from 11 multi-member constituencies by a party-list system of proportional representation,...

. The Liberal Party, led by Ichirō HatoyamaIchiro Hatoyamawas a Japanese politician and the 52nd, 53rd and 54th Prime Minister of Japan, serving terms from December 10, 1954 through March 19, 1955, from then to November 22, 1955, and from then through December 23, 1956.-Personal life:...

, won 142 seats, followed by the Progressive Party (94) and the Japanese Socialist Party (92), but Hatoyama was not allowed by the Allied occupation authorities to serve, as Prime Minister, because of prior service in the enemy government. - The Federal Communications CommissionFederal Communications CommissionThe Federal Communications Commission is an independent agency of the United States government, created, Congressional statute , and with the majority of its commissioners appointed by the current President. The FCC works towards six goals in the areas of broadband, competition, the spectrum, the...

approved the first expanison of long distance telephone calling since before World War II, as AT&TAT&TAT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications corporation headquartered in Whitacre Tower, Dallas, Texas, United States. It is the largest provider of mobile telephony and fixed telephony in the United States, and is also a provider of broadband and subscription television services...

was granted the right to add 1,000 new phone circuits. - At the annual meeting of the American Chemical SocietyAmerican Chemical SocietyThe American Chemical Society is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 161,000 members at all degree-levels and in all fields of chemistry, chemical...

in Atlantic City, Dr. Glenn T. SeaborgGlenn T. SeaborgGlenn Theodore Seaborg was an American scientist who won the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "discoveries in the chemistry of the transuranium elements", contributed to the discovery and isolation of ten elements, and developed the actinide concept, which led to the current arrangement of the...

announced the names for the two newest elements which had been created in 1946 at the University of California. Element 95 was dubbed americiumAmericiumAmericium is a synthetic element that has the symbol Am and atomic number 95. This transuranic element of the actinide series is located in the periodic table below the lanthanide element europium, and thus by analogy was named after another continent, America.Americium was first produced in 1944...

and Element 96 was curiumCuriumCurium is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Cm and atomic number 96. This radioactive transuranic element of the actinide series was named after Marie Skłodowska-Curie and her husband Pierre Curie. Curium was first intentionally produced and identified in summer 1944 by the group of...

.

April 11, 1946 (Thursday)

- The French National Assembly passed a resolution sponsored by deputy Félix Houphouët-BoignyFélix Houphouët-BoignyFélix Houphouët-Boigny , affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux, was the first President of Côte d'Ivoire. Originally a village chief, he worked as a doctor, an administrator of a plantation, and a union leader, before being elected to the French Parliament and serving in a number of...

of the Ivory Coast, finally outlawing the practice of "forced labor", in France's overseas territories. Until that time, it was permissible for the colonial government to require adult males in the African colonies to work on government projects, without remuneration, for a set number of days in each year. On the island of Madagascar, Malagasy men had to labor a minimum of fifty days on colonial projects. Houphouët-Boigny, for whom the "Loi Houphouët-Boigny" was named, would become the first President of the Ivory Coast in 1960. - The Bell X-1Bell X-1The Bell X-1, originally designated XS-1, was a joint NACA-U.S. Army/US Air Force supersonic research project built by Bell Aircraft. Conceived in 1944 and designed and built over 1945, it eventually reached nearly 1,000 mph in 1948...

experimental jet airplane made its first powered flight, with Chalmers "Slick" GoodlinChalmers GoodlinChalmers H. "Slick" Goodlin was the second test pilot of the Bell X-1 supersonic rocket plane, and the first to operate the craft in powered flight...

taking the first of the three prototypes, X-1-1, on a flight from the Muroc Army Air Field. The X-1-1 had first been glide-tested on January 25, 1946. On October 14, 1947, Chuck Yeager would fly the X-1-1 at faster than the speed of sound.

April 12, 1946 (Friday)

- British war hero Harold Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of TunisHarold Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of TunisField Marshal Harold Rupert Leofric George Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis was a British military commander and field marshal of Anglo-Irish descent who served with distinction in both world wars and, afterwards, as Governor General of Canada, the 17th since Canadian...

, took office as the 17th Governor General of CanadaGovernor General of CanadaThe Governor General of Canada is the federal viceregal representative of the Canadian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II...

, serving until 1952. - The Goodyear Tire and Rubber CompanyGoodyear Tire and Rubber CompanyThe Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company was founded in 1898 by Frank Seiberling. Goodyear manufactures tires for automobiles, commercial trucks, light trucks, SUVs, race cars, airplanes, farm equipment and heavy earth-mover machinery....

announced its plans to build dirigibles that would carry up to 300 passengers on overseas trips in the same manner as an ocean liner. None were ever put into service. - Born: Ed O'NeillEd O'NeillEdward Phillip "Ed" O'Neill, Jr. is an American actor. He is best known for his role as the main character, Al Bundy, on the Fox Network sitcom Married... with Children, for which he was nominated for two Golden Globes...

, American TV actor (Al Bundy on Married ... with Children), in YoungstownYoungstownYoungstown may refer to:A place*Canada**Britannia Youngstown, Edmonton, Alberta**Youngstown, Alberta*United States**Youngstown, Florida**Youngstown, Indiana**Youngstown, New York**Youngstown, Ohio***Youngstown State University...

, OhioOhioOhio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus... - Died: "Chips"Chips (dog)Chips the dog was the most decorated war dog from World War II. Chips was a German Shepherd-Collie-Siberian Husky mix owned by Edward J. Wren of Pleasantville, NY. During the war, private citizens like Wren donated their dogs for duty. Chips shipped out to the War Dog Training Center, Front...

, 6, mixed breed dog who was awarded the Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross for combat during World War II (both were later rescinded); of kidney failure.

April 13, 1946 (Saturday)

- A group of Jewish employees at a bakery in NurembergNurembergNuremberg[p] is a city in the German state of Bavaria, in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Situated on the Pegnitz river and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it is located about north of Munich and is Franconia's largest city. The population is 505,664...

placed arsenic on the bottom of thousands of loaves of bread to be delivered to a prisoner-of-war camp housing former members of the German SS. In all, 2,283 SS men at Stalag 13 became ill, none fatally, in the week that followed. - In France, the "Loi Marthe RichardMarthe RichardMarthe Richard, née Betenfeld was a prostitute and spy. She later became a politician and worked towards the closing of brothels in France in 1946.-Early life:...

" took effect, and the system of government-regulated houses of prostitution came to an end. The 1,400 brothels, including 200 in Paris, were closed. - "Arzamas-16" was established by the Soviet government at the site of the Russian town of SarovSarovSarov is a closed town in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia. Until 1995 it was known as Kremlyov ., while from 1946 to 1991 it was called Arzamas-16 . The town is off limits to foreigners as it is the Russian center for nuclear research. Population: -History:The history of the town can be divided...

, as a secret center for the construction of nuclear weapons. - British Prime Minister Clement AttleeClement AttleeClement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

authorized Sir Stafford CrippsStafford CrippsSir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour politician of the first half of the 20th century. During World War II he served in a number of positions in the wartime coalition, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union and Minister of Aircraft Production...

, the leader of the Cabinet Mission to British India, to agree to the partition of the colony into separate nations. The predominantly Hindu provinces became the Union of India, while the mostly Muslim provinces became the Dominion of PakistanDominion of PakistanThe Dominion of Pakistan was an independent federal Commonwealth realm in South Asia that was established in 1947 on the partition of British India into two sovereign dominions . The Dominion of Pakistan, which included modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, was intended to be a homeland for the...

(and, later, PakistanPakistanPakistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a sovereign state in South Asia. It has a coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by Afghanistan and Iran in the west, India in the east and China in the far northeast. In the north, Tajikistan...

and BangladeshBangladeshBangladesh , officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh is a sovereign state located in South Asia. It is bordered by India on all sides except for a small border with Burma to the far southeast and by the Bay of Bengal to the south...

). - Rikichi AndōRikichi Ando-See also:* Taiwan under Japanese rule...

, the last Japanese Governor-General of TaiwanGovernor-General of TaiwanThe position of Governor-General of Taiwan existed when Taiwan and the Pescadores were part of the Empire of Japan, from 1895 to 1945.The Japanese Governors-General were members of the Diet, civilian officials, Japanese nobles or generals...

, was captured by Nationalist forces and charged with war crimes. He committed suicide one week later. - Born: Al GreenAl GreenAlbert Greene , better known as Al Green, is an American gospel and soul music singer. He reached the peak of his popularity in the 1970s, with hit singles such as "You Oughta Be With Me", "I'm Still In Love With You", "Love and Happiness", and "Let's Stay Together"...

, American soul and gospel singer, in Forrest City, AR - Died: Miss Elsie Marks, who worked in carnivals for 20 years as the "Cobra Woman", after being bitten by a diamondback rattlesnake during a performance in Long Beach, California. Her autopsy confirmed that the Cobra Woman had been a man, Alexander Marks.

April 14, 1946 (Sunday)

- Chinese Communist leader Zhou EnlaiZhou EnlaiZhou Enlai was the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, serving from October 1949 until his death in January 1976...

announced the beginning of a war against the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shekChiang Kai-shekChiang Kai-shek was a political and military leader of 20th century China. He is known as Jiǎng Jièshí or Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng in Mandarin....

, one day after Soviet troops had withdrawn from Manchuria. The Communist forces attacked ChangchunChangchunChangchun is the capital and largest city of Jilin province, located in the northeast of the People's Republic of China, in the center of the Songliao Plain. It is administered as a sub-provincial city with a population of 7,677,089 at the 2010 census under its jurisdiction, including counties and...

on the same day and caputred it by April 17.

April 15, 1946 (Monday)

- The first television networkTelevision networkA television network is a telecommunications network for distribution of television program content, whereby a central operation provides programming to many television stations or pay TV providers. Until the mid-1980s, television programming in most countries of the world was dominated by a small...

was created, as the DuMont Television NetworkDuMont Television NetworkThe DuMont Television Network, also known as the DuMont Network, DuMont, Du Mont, or Dumont was one of the world's pioneer commercial television networks, rivalling NBC for the distinction of being first overall. It began operation in the United States in 1946. It was owned by DuMont...

linked New York and Washington by coaxial cableCoaxial cableCoaxial cable, or coax, has an inner conductor surrounded by a flexible, tubular insulating layer, surrounded by a tubular conducting shield. The term coaxial comes from the inner conductor and the outer shield sharing the same geometric axis...

. A two-hour program featuring speeches, "along with a short play, a quiz show, and a dance routine" were broadcast simultaneously on both stations. - Frozen concentrated orange juiceOrange juiceOrange juice is a popular beverage made from oranges. It is made by extraction from the fresh fruit, by desiccation and subsequent reconstitution of dried juice, or by concentration of the juice and the subsequent addition of water to the concentrate...

was first put on sale, by Florida Foods Corporation, as shipments arrived from a plant in Plymouth, FloridaPlymouth, FloridaPlymouth is an unincorporated community in Orange County, Florida, United States. It is located northwest of downtown Apopka along US 441 , at the intersection with Plymouth-Sorrento Road...

, under the name "Minute MaidMinute MaidMinute Maid is a product line of beverages, usually associated with lemonade or orange juice, but now extends to soft drinks of many kinds, including Hi-C...

" - Production began of the first NikonNikon, also known as just Nikon, is a multinational corporation headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, specializing in optics and imaging. Its products include cameras, binoculars, microscopes, measurement instruments, and the steppers used in the photolithography steps of semiconductor fabrication, of which...

cameras. The Japanese Optical Company (Nippon Kogaku) had manufactured lenses since 1917. - For the first time since 1933, the Jewish observance of PassoverPassoverPassover is a Jewish holiday and festival. It commemorates the story of the Exodus, in which the ancient Israelites were freed from slavery in Egypt...

was legally held in Germany. - The United States Army revealed the existence of its previously secret night vision device, the "Snooperscope", which had been used by Army snipers during the Second World War.

- The daily comic strip Mark TrailMark TrailMark Trail is a newspaper comic strip created by the American cartoonist Ed Dodd. Introduced April 15, 1946, the strip centers on environmental and ecological themes. In 2006, King Features syndicated the strip to nearly 175 newspapers....

, created by Ed DoddEd DoddEdward Benton Dodd was a 20th century American cartoonist known for his Mark Trail comic strip.-Early years:...

and showcasing the adventures of a park ranger, made debut, syndicated by the New York PostNew York PostThe New York Post is the 13th-oldest newspaper published in the United States and is generally acknowledged as the oldest to have been published continuously as a daily, although – as is the case with most other papers – its publication has been periodically interrupted by labor actions...

. - Died: Thomas Dixon, Jr.Thomas Dixon, Jr.Thomas F. Dixon, Jr. was an American Baptist minister, playwright, lecturer, North Carolina state legislator, lawyer, and author, perhaps best known for writing The Clansman — which was to become the inspiration for D. W...

, 92, American author and racist

April 16, 1946 (Tuesday)

- The United States made its first successful launch of a V-2 rocketV-2 rocketThe V-2 rocket , technical name Aggregat-4 , was a ballistic missile that was developed at the beginning of the Second World War in Germany, specifically targeted at London and later Antwerp. The liquid-propellant rocket was the world's first long-range combat-ballistic missile and first known...

, captured from Germany and tested at the White Sands Proving Ground. In all, 63 were fired for various purposes as part of American development of its own missile program. - The mining firm Western Holdings Lts. announced the discovery, at OdendaalsrusOdendaalsrusOdendaalsrus is the oldest gold mining town in the Lejweleputswa District Municipality of the Free State province in South Africa.-History:It started out in 1912 as a ramshackle collection of farms and a central church that became a town. In April 1946 gold was struck on the farm Geduld near the town...

of the richest gold vein ever found in South AfricaSouth AfricaThe Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

, setting off the first gold rushGold rushA gold rush is a period of feverish migration of workers to an area that has had a dramatic discovery of gold. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, and the United States, while smaller gold rushes took place elsewhere.In the 19th and early...

since before World War II. The yield was 62 ounces per ton, compared to 1/4 ounce per ton in most South African ore. - Baseball CommissionerBaseball CommissionerThe Commissioner of Baseball is the chief executive of Major League Baseball and its associated minor leagues. Under the direction of the Commissioner, the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball hires and maintains the sport's umpiring crews, and negotiates marketing, labor, and television contracts...

A.B. Chandler announced a five-year suspension of any American players who broke their contracts to sign with Jorge Pasquel's Mexican League. Twenty major leaguers had been signed away after Pasquel attempted to compete against the American and National Leagues. - In the eight opening games for the 16 major league teams, a record 236,730 turned out. Among 18,261 who watched the Boston Braves beat the visiting Brooklyn Dodgers, 5–3, more than 300 discovered that they had been sitting in wet paint.

- The world learned for the first time of a coal mine disaster that had killed 1,549 minersBenxihu CollieryBenxihu Colliery , located in Benxi, Liaoning, China, was first mined in 1905. It started as a iron and coal mining project under joint Japanese and Chinese control. As time passed, the project came more and more under Japanese control...

-- mostly Chinese and Korean, laboring for a Japanese company – four years after it had happened. The April 16, 1942, explosion had been kept secret, even from the Tokyo government, by Japanese military officials.

April 17, 1946 (Wednesday)

- In the first large scale protest against American occupation since Japan's 1945 surrender, an estimated 200,000 Japanese demonstrators marched in TokyoTokyo, ; officially , is one of the 47 prefectures of Japan. Tokyo is the capital of Japan, the center of the Greater Tokyo Area, and the largest metropolitan area of Japan. It is the seat of the Japanese government and the Imperial Palace, and the home of the Japanese Imperial Family...

in protest against the U.S.-selected Prime Minister, Kijūrō ShideharaKijuro ShideharaBaron was a prominent pre–World War II Japanese diplomat and the 44th Prime Minister of Japan from 9 October 1945 to 22 May 1946. He was a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan before and after World War II, and was also the last Japanese prime minister who was a member of the kazoku...

. The SCAP occupation sent in U.S. soldiers to disperse the crowd. - SyriaSyriaSyria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

's independence from France was made complete with the withdrawal of the last occupying forces from that nation. April 17 is still recognized as "evacuation day".

- Died: Jack Quinn (baseball)Jack Quinn (baseball)John Picus "Jack" Quinn, born Joannes Pajkos , was a pitcher in Major League Baseball. Quinn pitched for eight teams in three major leagues and made his final appearance at the age of 50.-Biography:Born in Štefurov, Slovakia , Quinn emigrated to America as an...

, 62, American baseball player 1909–1933, and one of the last three who could legally throw a "spitballSpitballA spitball is an illegal baseball pitch in which the ball has been altered by the application of saliva, petroleum jelly, or some other foreign substance....

"

April 18, 1946 (Thursday)

- The 34-member League of NationsLeague of NationsThe League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, in its last meeting, transferred its assets to the United NationsUnited NationsThe United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and disbanded at midnight GenevaGenevaGeneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

time (2300 GMT). - The International Court of JusticeInternational Court of JusticeThe International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

, established by the United NationsUnited NationsThe United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and often referred to as the World CourtWorld Court* any of the international courts located in The Hague:**the International Court of Justice , a UN court that settles disputes between nations...

, held its first meeting, assembling at The HagueThe HagueThe Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

. - The United States gave full diplomatic recognition to the government of Josip Broz TitoJosip Broz TitoMarshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

in YugoslaviaYugoslaviaYugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

. - Twelve coal miners near Radford, VirginiaRadford, VirginiaRadford is a city in Virginia, United States. The population was 16,408 in 2010. For statistical purposes, the Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Radford with neighboring Montgomery County, including the towns of Blacksburg and Christiansburg, calling the combination the...

, were killed in a methane explosion. 4/19 - Jackie RobinsonJackie RobinsonJack Roosevelt "Jackie" Robinson was the first black Major League Baseball player of the modern era. Robinson broke the baseball color line when he debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947...

made his debut in "organized baseball", appearing for the minor league Montreal RoyalsMontreal RoyalsThe Montreal Royals were a minor league professional baseball team located in Montreal, Quebec, that existed from 1897–1917 and from 1928–60 as a member of the International League and its progenitor, the original Eastern League...

after having played for the Kansas City MonarchsKansas City MonarchsThe Kansas City Monarchs were the longest-running franchise in the history of baseball's Negro Leagues. Operating in Kansas City, Missouri and owned by J.L. Wilkinson, they were charter members of the Negro National League from 1920 to 1930. J.L. Wilkinson was the first Caucasian owner at the time...

in the Negro American LeagueNegro American LeagueThe Negro American League was one of the several Negro leagues which were created during the time organized baseball was segregated. The league was established in 1937, and continued to exist until 1960...

.

April 19, 1946 (Friday)

- The Constituent Assembly of France voted 309–249 to approve a new Constitution for what would be called the "Fourth Republic", subject to approval at a referendum set for May 5, under which a unicameral legislature would replace the existing Senate and Chamber of Deputies.

- Belmont, West VirginiaBelmont, West VirginiaBelmont is a city in Pleasants County, West Virginia, in the United States. It is part of the Parkersburg-Marietta-Vienna, WV-OH Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 1,036 at the 2000 census....

, and Farmers Branch, TexasFarmers Branch, TexasFarmers Branch is a city in Dallas County, Texas, United States. It is both an inner-ring suburb of Dallas and is part of the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. The population was 27,508 at the 2000 census. A July 1, 2008 U.S...

, were both incorporated as cities. - Born: Tim CurryTim CurryTimothy James "Tim" Curry is a British actor, singer, composer and voice actor, known for his work in a diverse range of theatre, film and television productions. He currently resides in Los Angeles, California....

, British actor, vocalist, and composer, in GrappenhallGrappenhallGrappenhall is a suburban village in Warrington, Cheshire, England. It is situated along the Bridgewater Canal, and forms one of the principal settlements of Grappenhall and Thelwall civil parish... - Died: Walter DandyWalter DandyWalter Edward Dandy, M.D. was an American neurosurgeon and scientist. He is considered one of the founding fathers of neurosurgery, along with Victor Horsley and Harvey Cushing...

, 60, pioneering American neurosurgeon

April 20, 1946 (Saturday)

- The Anglo-American Committee of InquiryAnglo-American Committee of InquiryThe Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and American attempt in 1946 to agree upon a policy as regards the admission of Jews to Palestine. The Committee was tasked to consult representative Arabs and Jews on the problems of Palestine, and to make other recommendations 'as may be...

issued its recommendations on the future of PalestinePalestinePalestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

, including allowing up to 100,000 Jewish refugees from Europe to be resettled in the area, but barring a Jewish state. - The residents of Lake Success, New YorkLake Success, New YorkLake Success is a village in Nassau County, New York in the United States. The population was 2,934 at the 2010 census.Lake Success is in the Town of North Hempstead on northwest Long Island. Lake Success was the temporary home of the United Nations from 1946 to 1951, occupying the headquarters of...

, a village on Long IslandLong IslandLong Island is an island located in the southeast part of the U.S. state of New York, just east of Manhattan. Stretching northeast into the Atlantic Ocean, Long Island contains four counties, two of which are boroughs of New York City , and two of which are mainly suburban...

, voted 118–70 to temporarily house the headquarters of the United NationsUnited NationsThe United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, at the old Sperry Gyroscope Company plant. - Born: Julien PoulinJulien PoulinJulien Poulin is an actor, film director, screenwriter, film producer, and composer in Quebec, Canada. He has portrayed numerous roles in several popular Quebec films and series...

, Canadian actor, in MontrealMontrealMontreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America... - Died: Mae BuschMae BuschMae Busch was an Australian film actress who worked in both silent and sound films in early Hollywood. In the latter part of her career, she appeared in many Laurel and Hardy comedies, where she frequently played Hardy's shrewish wife.-Early life and career:Born in Melbourne, Australia, Busch was...

, 54, American film actress in Laurel and HardyLaurel and HardyLaurel and Hardy were one of the most popular and critically acclaimed comedy double acts of the early Classical Hollywood era of American cinema...

comedies

April 21, 1946 (Sunday)

- The Socialist Unity Party of GermanySocialist Unity Party of GermanyThe Socialist Unity Party of Germany was the governing party of the German Democratic Republic from its formation on 7 October 1949 until the elections of March 1990. The SED was a communist political party with a Marxist-Leninist ideology...

(Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands or SED), with one million members, was created in the Soviet zone of Germany (later East Germany by the merger of the Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party. The SED would govern East Germany from 1946 until 1990. - The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) made the first successful transmission of its system of color televisionColor televisionColor television is part of the history of television, the technology of television and practices associated with television's transmission of moving images in color video....

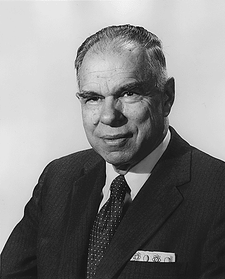

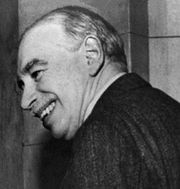

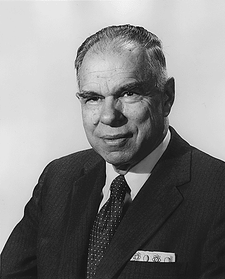

, in a format that could be received by both black-and-white and color television sets. - Died: John Maynard KeynesJohn Maynard KeynesJohn Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA , was a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments...

, 62, British economist for whom Keynesian economicsKeynesian economicsKeynesian economics is a school of macroeconomic thought based on the ideas of 20th-century English economist John Maynard Keynes.Keynesian economics argues that private sector decisions sometimes lead to inefficient macroeconomic outcomes and, therefore, advocates active policy responses by the...

is named

April 22, 1946 (Monday)

- Harlan Fiske StoneHarlan Fiske StoneHarlan Fiske Stone was an American lawyer and jurist. A native of New Hampshire, he served as the dean of Columbia Law School, his alma mater, in the early 20th century. As a member of the Republican Party, he was appointed as the 52nd Attorney General of the United States before becoming an...

, the 73 year old Chief Justice of the United StatesChief Justice of the United StatesThe Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

, was announcing his dissenting opinion in the case of Girouard v. United States, when he had the onset of a stroke. Stone was taken by ambulance to his home and died of a cerebral thrombosis that evening. - John F. KennedyJohn F. KennedyJohn Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

, the 28 year old son of former U.S. Ambassador to Britain Joseph P. Kennedy, announced his candidacy for the U.S. House of Representatives. - A woman in Bacacay, BrazilBrazilBrazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, was reported to have given birth to two boys and eight girls, an item listed under "Highest number at a single birth" in The Guinness Book of Records.

April 23, 1946 (Tuesday)

- Manuel RoxasManuel RoxasManuel Acuña Roxas was the first president of the independent Third Republic of the Philippines and fifth president overall. He served as president from the granting of independence in 1946 until his abrupt death in 1948...

was elected as the first President of the Third Republic of the Philippines, as well as the last President (equivalent to Governor) of the Commonwealth of the PhilippinesCommonwealth of the PhilippinesThe Commonwealth of the Philippines was a designation of the Philippines from 1935 to 1946 when the country was a commonwealth of the United States. The Commonwealth was created by the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1934. When Manuel L...

, defeating incumbent Sergio OsmeñaSergio OsmeñaSergio Osmeña y Suico was a Filipino politician who served as the 4th President of the Philippines from 1944 to 1946. He was Vice President under Manuel L. Quezon, and rose to the presidency upon Quezon's death in 1944, being the oldest Philippine president to hold office at age 65...

in advance of scheduled independence. - The patent for the first VespaVespaVespa is an Italian brand of scooter manufactured by Piaggio. The name means wasp in Italian.The Vespa has evolved from a single model motor scooter manufactured in 1946 by Piaggio & Co. S.p.A...

motor scooter was filed, by the Italian company Societa Rinaldo Piaggio. Inexpensive, reliable and fast, the Vespa soon became popular worldwide. - Grave robbers in MilanMilanMilan is the second-largest city in Italy and the capital city of the region of Lombardy and of the province of Milan. The city proper has a population of about 1.3 million, while its urban area, roughly coinciding with its administrative province and the bordering Province of Monza and Brianza ,...

stole the remains of Benito MussoliniBenito MussoliniBenito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

from an unmarked pauper's grave. The body, taken by admirers of Italy's Fascist dictator, was located on August 12 at a monastery in PaviaPaviaPavia , the ancient Ticinum, is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, northern Italy, 35 km south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It is the capital of the province of Pavia. It has a population of c. 71,000...

. - The Eastern Pennsylvania Basketball League, which went on to become the minor league Continental Basketball AssociationContinental Basketball AssociationThe Continental Basketball Association was a professional men's basketball league in the United States, which has been on hiatus since the 2009 season.- History :...

, was founded. The CBA played for 64 seasons before folding in 2009. - A 19-year old sailor, on the U.S. Navy tank landing ship USS LST-172, shot to death nine of his shipmates before being overpowered. Seaman 2nd class William Vincent Smith made the attack while the boat was cruising on the Yangtze RiverYangtze RiverThe Yangtze, Yangzi or Cháng Jiāng is the longest river in Asia, and the third-longest in the world. It flows for from the glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau in Qinghai eastward across southwest, central and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai. It is also one of the...

. Smith hanged himself in jail on August 2, 1947, while awaiting a court martial. - Howard HughesHoward HughesHoward Robard Hughes, Jr. was an American business magnate, investor, aviator, engineer, film producer, director, and philanthropist. He was one of the wealthiest people in the world...

's WesternWestern (genre)The Western is a genre of various visual arts, such as film, television, radio, literature, painting and others. Westerns are devoted to telling stories set primarily in the latter half of the 19th century in the American Old West, hence the name. Some Westerns are set as early as the Battle of...

movie The OutlawThe OutlawThe Outlaw is a 1943 American Western film, directed by Howard Hughes and starring Jane Russell. The supporting cast includes Jack Buetel, Thomas Mitchell, and Walter Huston. Hughes also produced the film, while Howard Hawks served as an uncredited co-director...

(USUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, 1943), starring Jane RussellJane RussellJane Russell was an American film actress and was one of Hollywood's leading sex symbols in the 1940s and 1950s....

, went on general releaseFilm releaseA film release is the stage at which a completed film is legally authorized by its owner for public distribution.The process includes locating a distributor to handle the film...

.

April 24, 1946 (Wednesday)

- In the United States, the Blue AngelsBlue AngelsThe United States Navy's Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, popularly known as the Blue Angels, was formed in 1946 and is currently the oldest formal flying aerobatic team...

stunt flying team was formed by the U.S. Navy. - In the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, two new fighter jets-- the MiG-9, flown by Alexei Grinchik, and the Yak-15, piloted by Mikhail I. Ivanov-- both flew for the first time. A coin toss determined that the MiG was allowed to take off first. - In France, the Constituent Assembly voted 487 to 63 to nationalize the insurance industry, taking over fifty large companies.

April 25, 1946 (Thursday)

- Forty-seven people were killed and 127 injured in a railroad accident at Naperville, IllinoisNaperville, IllinoisNaperville is a city in DuPage and Will Counties in Illinois in the United States, voted the second best place to live in the United States by Money Magazine in 2006. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 141,853. It is the fifth largest city in the state, behind Chicago,...

, when the Burlington Railroad's "Exposition Flyer" crashed at (CST) into the same line's "Advance Flyer", which had stalled after an earlier departure from Chicago. - A Marian apparition, wherein observers see the Virgin Mary appear before them, was first reported to have happened near the Bavarian village of MarienfriedPfaffenhofen (district)Pfaffenhofen is a district in Bavaria, Germany. It is bounded by the districts of Eichstätt, Kelheim, Freising, Dachau and Neuburg-Schrobenhausen, and the city of Ingolstadt.-History:...

. The Virgin's appearance was repeated on May 25 and June 25, and the shrine of "Our Lady of Marienfried" was established.

- Fritz Kuhn, the would-be American fuehrer who led the Nazi German American Bund, was released from an internment camp in his native Germany, after American authorities concluded that he no longer posed a threat to security.

- Born: Talia ShireTalia ShireTalia Shire is an American actress most known for her roles as Connie Corleone in The Godfather films and Adrian Balboa in the Rocky series.-Personal life:...

, American actress, in Lake Success, New YorkLake Success, New YorkLake Success is a village in Nassau County, New York in the United States. The population was 2,934 at the 2010 census.Lake Success is in the Town of North Hempstead on northwest Long Island. Lake Success was the temporary home of the United Nations from 1946 to 1951, occupying the headquarters of...

; Strobe TalbottStrobe TalbottNelson Strobridge "Strobe" Talbott III is an American foreign policy analyst associated with Yale University and the Brookings Institution, a former journalist associated with Time magazine and diplomat who served as the Deputy Secretary of State from 1994 to 2001.-Early life:Born in Dayton, Ohio...

, American foreign policy analyst, in DaytonDaytonDayton is a city in Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County, Ohio, United States.Dayton may also refer to:-United States:*Dayton, Alabama*Dayton, California, in Butte County*Dayton, Lassen County, California*Dayton, Idaho*Dayton, Indiana...

, OhioOhioOhio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

; John FoxJohn Fox (statistician)John Fox is a British statistician, who has worked in both the public service and academia.He was born on 25 April 1946, the son of Fred Frank Fox OBE. He was educated at Dauntsey's School, University College London and Imperial College London...

, British statistician; and Vladimir ZhirinovskyVladimir ZhirinovskyVladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky is a Russian politician, colonel of the Russian Army, founder and the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia , Vice-Chairman of the State Duma, and a member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe....

,

April 26, 1946 (Friday)

- The port of HarbinHarbinHarbin ; Manchu language: , Harbin; Russian: Харби́н Kharbin ), is the capital and largest city of Heilongjiang Province in Northeast China, lying on the southern bank of the Songhua River...

, tenth largest city in China, was taken over by Chinese Communist forces without incident. - The town of Pemberton, MinnesotaPemberton, MinnesotaPemberton is a city in Blue Earth County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 247 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Mankato–North Mankato Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

, was incorporated. - Born: Marilyn NelsonMarilyn NelsonMarilyn Nelson is an American poet, translator and children's book author. She is the author or translator of twelve books and three chapbooks.-Early life:...

, American poet, in Cleveland

April 27, 1946 (Saturday)

- The "Whirlaway", the first successful helicopter to have twin engines and twin rotors, was flown for the first time, with test pilot Charles R. Wood taking it up. Made by McDonnell AircraftMcDonnell AircraftThe McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer based in St. Louis, Missouri. The company was founded on July 16, 1939 by James Smith McDonnell, and was best known for its military fighters, including the F-4 Phantom II, and manned spacecraft including the Mercury capsule...

, the helicopter was designed so that if the engine powering one rotor failed, the remaining engine could still power both rotors, making helicopters safe to use. - In the first FA Cup Final1946 FA Cup FinalThe 1946 FA Cup Final, the first since the start of the Second World War, was contested by Derby County and Charlton Athletic at Wembley. Derby won 4–1 after extra time, with goals from Bert Turner , Peter Doherty and a double from Jackie Stamps.-Match summary:The game was goalless until the...

to be played since 1939, Derby CountyDerby County F.C.Derby County Football Club is an English football based in Derby. the club play in the Football League Championship and is notable as being one of the twelve founder members of the Football League in 1888 and is, therefore, one of only ten clubs to have competed in every season of the English...

beat Charlton AthleticCharlton Athletic F.C.Charlton Athletic Football Club is an English professional football club based in Charlton, in the London Borough of Greenwich. They compete in Football League One, the third tier of English football. The club was founded on 9 June 1905, when a number of youth clubs in the southeast London area,...

4–1.

April 28, 1946 (Sunday)

- In DresdenDresdenDresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

, elections in the American zone in occupied Germany were disrupted by rioting. A crowd of Jewish displaced persons, estimated by American officers at 5,000 or more, marched into town after two security guards went missing, and attacks were made on polling places. Rioting continued for 5½ hours until the U.S. Army forced the participants back to the displaced persons camp. The elections throughout the zone attracted voters for local government offices. - The Pestalozzi Children’s Village (Kinderdorf Pestalozzi) was established at TrogenTrogenTrogen is a municipality in the canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden in Switzerland. The town is the seat of the canton's judicial authorities.-History:...

in SwitzerlandSwitzerlandSwitzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

to accommodate and educate children orphanedOrphanAn orphan is a child permanently bereaved of or abandoned by his or her parents. In common usage, only a child who has lost both parents is called an orphan...

by World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, according to PestalozzianJohann Heinrich PestalozziJohann Heinrich Pestalozzi was a Swiss pedagogue and educational reformer who exemplified Romanticism in his approach....

principles. - The Chinese city of Tsitsihar (now QiqiharQiqihar- Subdivisions :Qiqihar is divided into 16 divisions: 7 districts , 8 counties and 1 county-level city .-Economy:...

), with several million residents, became the third major metropolitan area to surrender to the Chinese Communist government.

April 29, 1946 (Monday)

- International Military Tribunal for the Far EastInternational Military Tribunal for the Far EastThe International Military Tribunal for the Far East , also known as the Tokyo Trials, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, or simply the Tribunal, was convened on April 29, 1946, to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for three types of crimes: "Class A" crimes were reserved for those who...

: Former Japanese Prime Ministers Hideki TojoHideki TōjōHideki Tōjō was a general of the Imperial Japanese Army , the leader of the Taisei Yokusankai, and the 40th Prime Minister of Japan during most of World War II, from 17 October 1941 to 22 July 1944...