Polish Corridor

Encyclopedia

|

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia

Pomerelia

Pomerelia is a historical region in northern Poland. Pomerelia lay in eastern Pomerania: on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea and west of the Vistula and its delta. The area centered on the city of Gdańsk at the mouth of the Vistula...

(Pomeranian Voivodeship, eastern Pomerania

Pomerania

Pomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

, formerly part of West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

), which provided the Second Republic of Poland (1920–1939) with access to the Baltic Sea

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

, thus dividing the bulk of Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

from the province of East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

. The Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

(now the Polish city of Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

) was separate from both Poland and Germany. A similar territory, also occasionally referred to as a corridor, had been connected to the Polish Crown as part of Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia was a Region of the Kingdom of Poland and of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth . Polish Prussia included Pomerelia, Chełmno Land , Malbork Voivodeship , Gdańsk , Toruń , and Elbląg . It is distinguished from Ducal Prussia...

during the period 1466–1772.

Terminology

According to German historian Hartmut BoockmannHartmut Boockmann

Hartmut Boockmann was a German historian, whose research in medieval history made him internationally respected.Hartmut Boockmann made his Ph.D. in 1965...

the term "Corridor" was first used by Polish politicians, while Polish historian Grzegorz Lukomski writes that the word was coined by German nationalist propaganda of the 1920s. Internationally the term was used in the English language already as early as March 1919 and whatever its origins, it became a widespread term in English language usage.

The equivalent German term is Polnischer Korridor. Polish names include korytarz polski ("Polish corridor") and korytarz gdański ("Gdańsk corridor"); however, reference to the region as a corridor came to be regarded as offensive by interwar Polish diplomacy. Among harshest criticizers of the term corridor was Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck

Józef Beck

' was a Polish statesman, diplomat, military officer, and close associate of Józef Piłsudski...

, who in his May 5, 1939 speech in Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

(Polish parliament) said: "I am insisting that the term Pomeranian Voivodeship should be used. The word corridor is an artificial idea, as this land has been Polish for centuries, with a small percentage of German settlers". Poles would commonly refer to the region as Pomorze Gdańskie ("Gdańsk Pomerania, Pomerelia

Pomerelia

Pomerelia is a historical region in northern Poland. Pomerelia lay in eastern Pomerania: on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea and west of the Vistula and its delta. The area centered on the city of Gdańsk at the mouth of the Vistula...

") or simply Pomorze ("Pomerania

Pomerania

Pomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

"), or as województwo pomorskie ("Pomeranian Voivodeship

Pomeranian Voivodeship (1919-1939)

Pomeranian Voivodeship or Pomorskie Voivodeship was an administrative unit of inter-war Poland . It ceased to exist in September 1939, following German and Soviet aggression on Poland...

"), which was the administrative name for the region.

History of the area

In the tenth century, Pomerelia was settled by Slavic Pomeranians, ancestors of the KashubiansKashubians

Kashubians/Kaszubians , also called Kashubs, Kashubes, Kaszubians, Kassubians or Cassubians, are a West Slavic ethnic group in Pomerelia, north-central Poland. Their settlement area is referred to as Kashubia ....

, which were subdued by Boleslaw I of Poland

Boleslaw I of Poland

Bolesław I Chrobry , in the past also known as Bolesław I the Great , was a Duke of Poland from 992-1025 and the first King of Poland from 19 April 1025 until his death...

. In the eleventh century, they created an independent duchy. In 1116/1121, Pomerania

Pomerania

Pomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

was again conquered by Poland. In 1138, following the death of Duke Bolesław III, Poland was fragmented into several semi-independent principalities. The Samborides

Samborides

The Samborides or House of Sobiesław were a ruling dynasty in the historic region of Pomerania. They were first documented about 1155 as governors in the eastern Pomerelian lands serving the royal Piast dynasty of Poland, and from 1227 ruled as autonomous princes until 1294, at which time the...

, principes in Pomerelia

Pomerelia

Pomerelia is a historical region in northern Poland. Pomerelia lay in eastern Pomerania: on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea and west of the Vistula and its delta. The area centered on the city of Gdańsk at the mouth of the Vistula...

, gradually evolved into independent dukes, who ruled the duchy until 1294. Before Pomerelia regained independence in 1227, their dukes were vassals of Poland and Denmark. Since 1308, following succession wars between Poland and Brandenburg, Pomerelia was subjugated by the Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights

Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights

The State of the Teutonic Order, , also Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights or Ordensstaat , was formed in 1224 during the Northern Crusades, the Teutonic Knights' conquest of the pagan West-Baltic Old Prussians in the 13th century....

in Prussia

Prussia (region)

Prussia is a historical region in Central Europe extending from the south-eastern coast of the Baltic Sea to the Masurian Lake District. It is now divided between Poland, Russia, and Lithuania...

. In 1466, with the second Peace of Thorn, Pomerelia became part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

as a part of autonomous Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia was a Region of the Kingdom of Poland and of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth . Polish Prussia included Pomerelia, Chełmno Land , Malbork Voivodeship , Gdańsk , Toruń , and Elbląg . It is distinguished from Ducal Prussia...

. After the First Partition of Poland

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

in 1772 it was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

and named West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

, and became a constituent part of the new German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

in 1871. Thus the Polish Corridor was not an entirely new creation: the territory assigned to Poland had nominally been part of Poland prior to 1772, but with a large degree of autonomy.

Allied plans for a corridor in the World War I aftermath

After the First World War, a Poland was to be re-established as an independent country. Since a Polish state had not existed since the Congress of ViennaCongress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

, the future republic's territory had to be defined.

Giving Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

access to the sea was one of the guarantees proposed by United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

in his Fourteen Points

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that the Great War was being fought for a moral cause and for postwar peace in Europe...

of 1918. The thirteenth of Wilson's points was:

- "An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant."

The following arguments were behind the creation of the corridor:

Ethnographic reasons

Kashubians

Kashubians/Kaszubians , also called Kashubs, Kashubes, Kaszubians, Kassubians or Cassubians, are a West Slavic ethnic group in Pomerelia, north-central Poland. Their settlement area is referred to as Kashubia ....

, who had supported the Polish national lists in German elections) in the region compared with 385,000 Germans (including troops stationed in the area). The Poles did not want the Polish population to remain under the control of the German state, which had in the past treated the Polish population and other minorities as second-class citizens and pursued Germanization. As Professor Lewis Bernstein Namier

Lewis Bernstein Namier

Sir Lewis Bernstein Namier was an English historian. He was born Ludwik Niemirowski in Wola Okrzejska in what was then part of the Russian Empire and is today in Poland.-Life:...

(1888–1960) born to Jewish parents in Lublin Governorate

Lublin Governorate

Lublin Governorate ) was an administrative unit of the Congress Poland.-History:It was created in 1837 from the Lublin Voivodeship, and had the same borders and capital as the voivodeship....

(Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, former Congress Poland

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

) and later a British citizen, a former member of the British Intelligence Bureau throughout World War I and the British delegation at the Versailles conference, known for his anti-Polish attitude wrote in the Manchester Guardian on November 7, 1933: "The Poles are the Nation of the Vistula, and their settlements extend from the sources of the river to its estuary.... It is only fair that the claim of the river-basin should prevail against that of the seaboard.".

Economic reasons

The Poles held the view that without direct access to the Baltic SeaBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

, Poland's economic independence would be illusory. Around 60.5% of Polish import trade and 55.1% of exports went through the area. The report of the Polish Commission presented to the Allied Supreme Council said:

- "1,600,000 Germans in East Prussia can be adequately protected by securing for them freedom of trade across the corridor, whereas it would be impossible to give an adequate outlet to the inhabitants of the new Polish state (numbering 25,000,000) if this outlet had to be guaranteed across the territory of an alien and probably hostile Power."

The United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

eventually accepted this argument. The suppression of the Polish Corridor would have abolished the economic ability of Poland to resist dependence on Germany. As Lewis Bernstein Namier

Lewis Bernstein Namier

Sir Lewis Bernstein Namier was an English historian. He was born Ludwik Niemirowski in Wola Okrzejska in what was then part of the Russian Empire and is today in Poland.-Life:...

, Professor of Modern History at the University of Manchester

University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public research university located in Manchester, United Kingdom. It is a "red brick" university and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive British universities and the N8 Group...

and known for his "legendary hatred of Germany" and his Germanophobia, wrote in a newspaper article in 1933:

- "The whole of Poland's transport system ran towards the mouth of the Vistula....

- "90% of Polish exports came from her western provinces.

- "Cutting through of the Corridor has meant a minor amputation for Germany; its closing up would mean strangulation for Poland.".

By 1938, 77.7% of Polish exports left either through Gdańsk (31.6%) or the newly-built port of Gdynia

Gdynia

Gdynia is a city in the Pomeranian Voivodeship of Poland and an important seaport of Gdańsk Bay on the south coast of the Baltic Sea.Located in Kashubia in Eastern Pomerania, Gdynia is part of a conurbation with the spa town of Sopot, the city of Gdańsk and suburban communities, which together...

(46.1%)

Incorporation into the Second Polish Republic

During World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

had forced the Imperial Russian

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

troops out of Congress Poland

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

and Galicia, as manifested in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

on 3 March 1918. Following the military defeat of Austria-Hungary

Battle of Vittorio Veneto

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto was fought between 24 October and 3 November 1918, near Vittorio Veneto, during the Italian Campaign of World War I...

, an independent Polish republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

was declared in Western Galicia on 3 November 1918, the same day Austria signed the armistice. The collapse of Imperial Germany

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

's Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

, and the subsequent withdrawal of her remaining occupation forces after the Armistice of Compiègne

Armistice with Germany (Compiègne)

The armistice between the Allies and Germany was an agreement that ended the fighting in the First World War. It was signed in a railway carriage in Compiègne Forest on 11 November 1918 and marked a victory for the Allies and a complete defeat for Germany, although not technically a surrender...

on 11 November allowed the republic led by Roman Dmowski

Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski was a Polish politician, statesman, and chief ideologue and co-founder of the National Democracy political movement, which was one of the strongest political camps of interwar Poland.Though a controversial personality throughout his life, Dmowski was instrumental in...

and Josef Pilsudski to seize control over the former Congress Polish areas

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

. Also in November, the revolution in Germany forced the Kaiser

Kaiser

Kaiser is the German title meaning "Emperor", with Kaiserin being the female equivalent, "Empress". Like the Russian Czar it is directly derived from the Latin Emperors' title of Caesar, which in turn is derived from the personal name of a branch of the gens Julia, to which Gaius Julius Caesar,...

's abdication and gave way to the establishment of the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

. Starting in December, the Polish-Ukrainian War

Polish-Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918 and 1919 was a conflict between the forces of the Second Polish Republic and West Ukrainian People's Republic for the control over Eastern Galicia after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary.-Background:...

expanded the Polish republic's territory to include Volhynia

Volhynia

Volhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

and parts of Eastern Galicia, while at the same time the German Province of Posen

Province of Posen

The Province of Posen was a province of Prussia from 1848–1918 and as such part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. The area was about 29,000 km2....

(where even according to the German made 1910 census 61,5% of the population was Polish) was severed by the Greater Poland uprising

Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919)

The Greater Poland Uprising of 1918–1919, or Wielkopolska Uprising of 1918–1919 or Posnanian War was a military insurrection of Poles in the Greater Poland region against Germany...

, which succeeded in attaching most of the province's territory to Poland by January 1919. This led Weimar's Otto Landsberg

Otto Landsberg

Otto Landsberg was a German jurist and politician.-Life:Landsberg was born in 1869 in Rybnik in the Province of Silesia. After passing the Abitur in 1887 in Ostrowo, he moved to Berlin to study law. In 1895, having passed the First and Second State Examination , he opened a lawyer's office in...

and Rudolf Breitscheid

Rudolf Breitscheid

Rudolf Breitscheid, was a leading member of the Social Democratic Party and a delegate to the Reichstag during the era of the Weimar Republic in Germany....

to call for an armed force to secure Germany's remaining eastern territories (some of which contained significant Polish minorities, primarily on the former Prussian partition

Prussian partition

The Prussian partition refers to the former territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired during the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century by the Kingdom of Prussia.-History:...

territories). The call was answered by the minister of defense Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany . He served as the first Minister of Defence of Germany between 1919 and 1920.-Biography:...

, who decreed support for raising and deploying volunteer "Grenzschutz" forces to secure East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

, Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

and the Netze District

Netze District

The Netze District or District of the Netze was a territory in the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 until 1807. It included the urban centers of Bydgoszcz , Inowrocław , Piła and Wałcz and was given its name for the Noteć River that traversed it.Beside Royal Prussia, a land of the Polish Crown...

.

On 12 January, the Paris peace conference

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. It took place in Paris in 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities...

opened, resulting in the draft of the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

28 June 1919. Articles 27 and 28 of the treaty ruled on the territorial shape of the corridor, while articles 89 to 93 ruled on transit, citizenship and property issues. Per the terms of the Versailles treaty, which was put into effect on 20 January 1920, the corridor was established as Poland's access to the Baltic Sea

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

from 70% of the dissolved province of West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

.

The primarily German-speaking seaport of Danzig (Gdańsk), controlling the estuary

Estuary

An estuary is a partly enclosed coastal body of water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea....

of the main Polish waterway, the Vistula

Vistula

The Vistula is the longest and the most important river in Poland, at 1,047 km in length. The watershed area of the Vistula is , of which lies within Poland ....

river, became the Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

and was placed under the protection of the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

without a plebiscite. After the dock workers of Danzig harbour went on strike at a critical moment during the Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic—four states in post–World War I Europe...

, refusing to unload ammunition, the Polish Government decided to build a new seaport at Gdynia

Gdynia

Gdynia is a city in the Pomeranian Voivodeship of Poland and an important seaport of Gdańsk Bay on the south coast of the Baltic Sea.Located in Kashubia in Eastern Pomerania, Gdynia is part of a conurbation with the spa town of Sopot, the city of Gdańsk and suburban communities, which together...

in the territory of the Corridor, and connected this seaport to the Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

n industrial centers by the newly constructed Polish Coal Trunk Line railways.

Exodus of the German population

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

and aimed at a removal of the Polish nobility, which he treated with contempt. Frederick also described Poles as 'slovenly Polish trash' and compared them to the Iroquois

Iroquois

The Iroquois , also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse", are an association of several tribes of indigenous people of North America...

.

A second colonization aimed at Germanisation was pursued by Prussia after 1832. On the other hand, he encouraged administrators and teachers to be able to speak both German and Polish

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

. Laws were passed in Prussia aimed at Germanisation of the provinces of Posen

Province of Posen

The Province of Posen was a province of Prussia from 1848–1918 and as such part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. The area was about 29,000 km2....

and West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

in the late 19th century. A further 154,000 colonists, including locals, were settled by the Prussian Settlement Commission in the provinces of Posen and West Prussia before World War I. Military personnel was included in the population census. A number of German civil servants and merchants were introduced to the area, which influenced the population status.

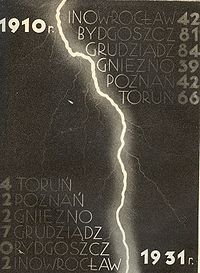

According to Richard Blanke, an American historian of German descent, 421,029 Germans were living in the area in 1910, making up 42.5% of the population. Blanke has been criticised by Christian Raitz von Frentz, his book classified by him as part of a series on the subject that have an anti-Polish bias, additionally Blanke's views have been described by Polish professor A. Cienciala as sympathetic to Germany. In addition to the military personnel included in the population census, a number of German civil servants and merchants were introduced to the area, which influenced the population mix, according to Andrzej Chwalba. By 1921 the proportion of Germans had dropped to 18.8% (175,771). Over the next decade, the German population decreased by another 70,000 to a share of 9.6%.

German political scientist Stefan Wolff

Stefan Wolff

Stefan Wolff is a German political scientist. He is a specialist in international security, particularly in the management, settlement and prevention of ethnic conflicts. He is currently Professor of International Security at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom...

, Professor at the University of Birmingham

University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham is a British Redbrick university located in the city of Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Birmingham Medical School and Mason Science College . Birmingham was the first Redbrick university to gain a charter and thus...

, says that the actions of Polish state officials after the corridor's establishment followed "a course of assimilation and oppression". As a result, a large number of Germans left Poland after the war: According to Wolff, 800,000 Germans had left Poland by 1923, according to Gotthold Rhode, 575,000 left the former province of Posen and the corridor after the war, according to Herrmann Rauschning, 800,000 Germans had left between 1918 and 1926, contemporary author Alfons Krysinski estimated 800,000 plus 100,000 from East Upper Silesia, the contemporary German statistics say 592,000 Germans had left by 1921, other Polish scholars say that up to a million Germans left. Polish author Władysław Kulski says that a number of them were civil servants with no roots in the province and around 378,000, and this is to a lesser degree is confirmed by some German sources such as Hermann Rauschning.

The question whether many of the Germans who left were actually settlers without roots in the area, has been raised by Lewis Bernstein Namier who remarked in 1933 "a question must be raised how many of those Germans had originally been planted artificially in that country by the Prussian Government."

According to the above mentioned Richard Blanke, in his book Orphans of Versailles, several reasons for the exodus of the German population are given.

- A number of former settlers from the Prussian Settlement Commission who settled in the area after 1886 in order to Germanise it were in some cases given a month to leave, in other cases they were told to leave at once.

- Poland found itself under threat during the Polish-Bolshevik war, and the German population feared that Bolshevik forces would control Poland. Migration to Germany was a way to avoid conscription and participation in the war.

- State-employed Germans such as judges, prosecutors, teachers and officials left as Poland did not renew their employment contracts. German industrial workers also left due to fear of lower-wage competitionCompetitionCompetition is a contest between individuals, groups, animals, etc. for territory, a niche, or a location of resources. It arises whenever two and only two strive for a goal which cannot be shared. Competition occurs naturally between living organisms which co-exist in the same environment. For...

. Many Germans became economically dependent on Prussian state aid as it fought the "Polish problem" in its provinces. - Germans refused to accept living in a Polish state. As Lewis Bernstein NamierLewis Bernstein NamierSir Lewis Bernstein Namier was an English historian. He was born Ludwik Niemirowski in Wola Okrzejska in what was then part of the Russian Empire and is today in Poland.-Life:...

said: "Some Germans undoubtedly left because they would not live under the dominion of a race which they had previously oppressed and despised." - Germans feared that the Poles would seek reprisals after over a century of harassment and discriminationDiscriminationDiscrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

by the Prussian and German state against the Polish population. - Social and linguistic isolation: While the population was mixed, only Poles were required to be bilingual. The Germans usually did not learn Polish. When Polish became the only official language in Polish-majority provinces, their situation became difficult. The Poles shunned Germans, which contributed to their isolation.

- Lower standards of living. Poland was a much poorer country than Germany.

- Former Nazi politician and later opponent Hermann RauschningHermann RauschningHermann Rauschning was a GermanConservative Revolutionary who briefly joined the Nazis before breaking with them. In 1934 he renounced Nazi party membership and defected to the United States where he denounced Nazism...

wrote that 10% of Germans were unwilling to remain in Poland regardless of their treatment, and another 10% were workers from other parts of the German Empire with no roots in the region.

Blanke says that official encouragement by the Polish state played a secondary role in the exodus. Christian Raitz von Frentz notes "that many of the repressive measures were taken by local and regional Polish authorities in defiance of Acts of Parliament and government decrees, which more often than not conformed with the minorities treaty, the Geneva Convention and their interpretation by the League council - though it is also true that some of the central authorities tacitly tolerated local initiatives against the German population." While there were demonstrations and protests and occasional violence against Germans, they were at a local level, and officials were quick to point out that they were a backlash against former discrimination against Poles. There were other demonstrations when Germans showed disloyalty during the Polish-Bolshevik war as the Red Army announced the return to the prewar borders of 1914. Despite popular pressure and occasional local actions, perhaps as many as 80% of Germans emigrated more or less voluntarily.

Helmutt Lippelt writes that Germany used the existence of German minority in Poland for political means and as part of its revisionist demands, which resulted in Polish countermeasures.As partial reaction to German revisionist claims the Polish Prime-Minister Władysław Sikorski stated in 1923, that the de-Germanization of these territories by liquidation of German properties and eviction of German "optaten" has to be ended quickly so that German nationalists will be educated that their view of temporary state of Polish western border is wrong.}

Impact on the East Prussian plebiscite

In the period leading up to the East Prussian plebisciteEast Prussian plebiscite

The East Prussia plebiscite , also known as the Allenstein and Marienwerder plebiscite or Warmia, Masuria and Powiśle plebiscite , was a plebiscite for self-determination of the regions Warmia , Masuria and Powiśle, which had been in parts of East Prussia and West Prussia, in accordance with...

in July 1920, the Polish authorities tried to prevent traffic through the Corridor, interrupting postal, telegraphic and telephone communication. On March 10, 1920, the British representative on the Marienwerder Plebiscite Commission, H.D. Beaumont, wrote of numerous continuing difficulties being made by Polish officials and added "as a result, the ill-will between Polish and German nationalities and the irritation due to Polish intolerance towards the German inhabitants in the Corridor (now under their rule), far worse than any former German intolerance of the Poles, are growing to such an extent that it is impossible to believe the present settlement (borders) can have any chance of being permanent.... It can confidently be asserted that not even the most attractive economic advantages would induce any German to vote Polish. If the frontier is unsatisfactory now, it will be far more so when it has to be drawn on this side (of the river) with no natural line to follow, cutting off Germany from the river bank and within a mile or so of Marienwerder, which is certain to vote German. I know of no similar frontier created by any treaty."

Impact on German through-traffic

The German Ministry for Transport established the Seedienst OstpreußenSeedienst Ostpreußen

The Seedienst Ostpreussen or Sea Service East Prussia was a ferry connection between the German provinces of Pomerania and, later, Schleswig-Holstein and the German exclave of East Prussia from 1920 to 1939.- Political background :...

("Sea Service East Prussia") in 1922 to provide a ferry connection to East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

, now a German exclave, so that it would be less dependent on transit through Polish territory.

Connections by train were also possible by "sealing" the wagons, i.e. passengers were not forced to apply for an official Polish visa

Visa (document)

A visa is a document showing that a person is authorized to enter the territory for which it was issued, subject to permission of an immigration official at the time of actual entry. The authorization may be a document, but more commonly it is a stamp endorsed in the applicant's passport...

in their passport; however the rigorous inspections by the Polish authorities before and after the sealing were strongly feared by the passengers.

In May 1925 a train, passing through the Corridor on its way to East Prussia, crashed because the spikes had been removed from the tracks for a short distance and the fishplates unbolted. 25 persons, including 12 women and 2 children, were killed, some 30 others were injured.

Land reform of 1925

According to Polish Historian Andrzej Chwalba, during the rule of the Kingdom of PrussiaKingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

and the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

various means were used to increase the amount of land owned by Germans at the expense of the Polish population. In Prussia, the Polish nobility had its estates confiscated after the Partitions, and handed over to German nobility. The same applied to Catholic monasteries. Later, the German Empire bought up land in an attempt to prevent the restoration of a Polish majority in Polish inhabited areas in its eastern provinces.

Christian Raitz von Frentz notes that measures aimed at reversing past Germanization included the liquidation of farms settled by the German government during the war under the 1908 law.

In 1925 the Polish government enacted a land reform program with the aim of expropriating landowners. While only 39% of the agricultural land in the Corridor was owned by Germans, the first annual list of properties to be reformed included 10,800 hectares from 32 German landowners and 950 hectares from seven Poles. The voivode of Pomorze, Wiktor Lamot, stressed that "the part of Pomorze through which the so-called corridor runs must be cleansed of larger German holdings". The coastal region "must be settled with a nationally conscious Polish population.... Estates belonging to Germans must be taxed more heavily to encourage them voluntarily to turn over land for settlement. Border counties... particularly a strip of land ten kilometers wide, must be settled with Poles. German estates that lie here must be reduced without concern for their economic value or the views of their owners'.

Prominent politicians and members of the German minority were the first to be included on the land reform list and to have their property expropriated.

Weimar German interests

The creation of the corridor aroused great resentment in Germany, and all post-war German WeimarWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

governments refused to recognize the eastern borders agreed at Versailles, and refused to follow Germany's acknowledgment of its western borders in the Treaty of Locarno of 1925 with a similar declaration with respect to its eastern borders.

Institutions in Weimar Germany supported and encouraged German minority organizations in Poland, in part radicalized by the Polish policy towards them, in filing close to 10,000 complaints about violations of minority rights to the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

.

Poland in 1931 declared her commitment to peace, but pointed out that any attempt to revise its borders would mean war. Additionally, in conversation with U.S. President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

, Polish delegate Filipowicz noted that any continued provocations by Germany could tempt the Polish side to invade, in order to settle the issue once and for all.

Nazi German and Polish diplomacy

The Nazi Party, led by Adolf HitlerAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

, took power in Germany in 1933. Hitler at first ostentatiously pursued a policy of rapprochement

Rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word rapprocher , is a re-establishment of cordial relations, as between two countries...

with Poland, culminating in the ten year Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact of 1934. In the years that followed, Germany placed an emphasis on rearmament, as did Poland and other European powers. Despite this, the Nazis were able to achieve their immediate goals without provoking armed conflict: in 1938 Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

annexed Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

after the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

. In October 1938, Germany tried to get Poland to join the Anti-Comintern Pact

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact was an Anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on November 25, 1936 and was directed against the Communist International ....

. Poland refused, as the alliance was rapidly becoming a sphere of influence of an increasingly powerful Germany.

Following negotiations with Hitler on the Munich Agreement, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

reported that, "He told me privately, and last night he repeated publicly, that after this Sudeten German question is settled, that is the end of Germany's territorial claims in Europe". Almost immediately following the agreement, however, Hitler reneged on it. The Nazis increased their requests for the incorporation of the Free City of Danzig into the Reich, citing the "protection" of the German majority as a motive.

In November 1938, Danzig's district administrator, Albert Forster

Albert Forster

Albert Maria Forster was a Nazi German politician. Under his administration as the Gauleiter of Danzig-West Prussia during the Second World War, the local non-German population suffered ethnic cleansing, mass murder, and forceful Germanisation...

, reported to the League of Nations that Hitler had told him Polish frontiers would be guaranteed if the Poles were "reasonable like the Czechs." German State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker

Ernst von Weizsäcker

Ernst Freiherr von Weizsäcker was a German diplomat and politician. He served as State Secretary at the Foreign Office from 1938 to 1943, and as German Ambassador to the Holy See from 1943 to 1945...

reaffirmed this alleged guarantee in December 1938.

The situation regarding the Free City and the Polish Corridor created a number of headaches for German and Polish Customs. The Germans requested the construction of an extra-territorial highway (to complete the Reichsautobahn Berlin-Königsberg) and railway through the Polish Corridor, connecting East Prussia to Danzig and Germany proper. If Poland agreed, in return they would extend the non-aggression pact for 25 years.

This seemed to conflict with Hitler's plans and with Poland's rejection of the Anti-Comintern Pact, and his desire either to isolate or to gain support against the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. German newspapers in Danzig and Nazi Germany played an important role in inciting nationalist sentiment: headlines buzzed about how Poland was misusing its economic rights in Danzig and German Danzigers were increasingly subjugated to the will of the Polish state. At the same time, Hitler also offered Poland additional territory as an enticement, such as the possible annexation of Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, the Memel Territory, Soviet Ukraine

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

and Czech inhabited lands.

However, Polish leaders continued to fear for the loss of their independence and a fate like that of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, which had yielded the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

to Germany in October 1938, only to be invaded by Germany in March 1939. Some felt that the Danzig question was inextricably tied to the problems in the Polish Corridor and any settlement regarding Danzig would be one step towards the eventual loss of Poland's access to the sea. Hitler's credibility outside Germany was very low after the occupation of Czechoslovakia, though some British and French politicians approved of a peaceful revision of the corridor's borders.

In 1939, Nazi Germany made another attempt to renegotiate the status of Danzig; Poland was to retain a permanent right to use the seaport if the route through the Polish Corridor was to be constructed. However, the Polish administration distrusted Hitler and saw the plan as a threat to Polish sovereignty, practically subordinating Poland to the Axis and the Anti-Comintern Bloc while reducing the country to a state of near-servitude.

Hitler used the issue of the status city as pretext for attacking Poland, while explaining during a high level meeting of German military officials in May 1939 that his real goal is obtaining Lebensraum

Lebensraum

was one of the major political ideas of Adolf Hitler, and an important component of Nazi ideology. It served as the motivation for the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, aiming to provide extra space for the growth of the German population, for a Greater Germany...

for Germany, isolating Poles from their Allies in the West and afterwards attacking Poland, thus avoiding the repeat of Czech situation

Ultimatum of 1939

A revised and less favorable proposal came in the form of an ultimatumUltimatum

An ultimatum is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance. An ultimatum is generally the final demand in a series of requests...

delivered by the Nazis in late August, after the orders had already been given to attack Poland on September 1, 1939. Nevertheless, at midnight on August 29, Joachim von Ribbentrop

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop was Foreign Minister of Germany from 1938 until 1945. He was later hanged for war crimes after the Nuremberg Trials.-Early life:...

handed British Ambassador Sir Neville Henderson a list of terms that would allegedly ensure peace in regard to Poland. Danzig was to return to Germany and there was to be a plebiscite in the Polish Corridor; Poles who had been born or had settled there since 1919 would have no vote, while all Germans born but not living there would. An exchange of minority populations between the two countries was proposed. If Poland accepted these terms, Germany would agree to the British offer of an international guarantee, which would include the Soviet Union. A Polish plenipotentiary

Plenipotentiary

The word plenipotentiary has two meanings. As a noun, it refers to a person who has "full powers." In particular, the term commonly refers to a diplomat fully authorized to represent his government as a prerogative...

, with full powers, was to arrive in Berlin and accept these terms by noon the next day. The British Cabinet viewed the terms as "reasonable," except the demand for a Polish Plenipotentiary, which was seen as similar to Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha was a Czech lawyer, the third President of Czecho-Slovakia from 1938 to 1939. From March 1939, he presided under the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.-Judicial career:...

accepting Hitler's terms in mid-March 1939.

When Ambassador Józef Lipski

Józef Lipski

Józef Lipski . Polish diplomat and Ambassador to Nazi Germany, 1934 to 1939. Lipski played a key role in foreign policy of Second Polish Republic.-Life:Lipski trained as a lawyer, and joined the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1925....

went to see Ribbentrop on August 30, he was presented with Hitler’s demands. However, he did not have the full power to sign and Ribbentrop ended the meeting. News was then broadcast that Poland had rejected Germany's offer.

Nazi German invasion – end of the corridor

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded PolandInvasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

. German forces defeated the Polish Army Pomorze tasked with defense of this region and captured the corridor during the Battle of Tuchola Forest by September 5. Other notable battles took place at Westerplatte

Battle of Westerplatte

The Battle of Westerplatte was the very first battle that took place after Germany invaded Poland and World War II began in Europe. During the first week of September 1939, a Military Transit Depot on the peninsula of Westerplatte, manned by fewer than 200 Polish soldiers, held out for seven days...

, the Polish post office in Danzig

Defense of the Polish Post Office in Danzig

The Defense of the Polish Post Office in Danzig was one of the first acts of World War II in Europe, as part of the Invasion of Poland....

, Oksywie, and Hel

Battle of Hel

The Battle of Hel was one of the longest battles of the Invasion of Poland during World War II.The Hel Peninsula, together with the town of Hel, was the pocket of Polish Army resistance that held out the longest against the German invasion...

.

Ethnic composition

Most of the area was inhabited by PolesPoles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

, Germans

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

, and Kashubians

Kashubians

Kashubians/Kaszubians , also called Kashubs, Kashubes, Kaszubians, Kassubians or Cassubians, are a West Slavic ethnic group in Pomerelia, north-central Poland. Their settlement area is referred to as Kashubia ....

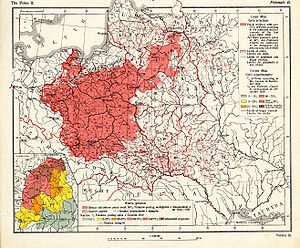

. The census of 1910 showed that there were 528,000 Poles (including West Slavic Kashubians) compared to 385,000 Germans in the region. The census included German soldiers stationed in the area as well as public officials sent to administer the area.

Since 1886, a Settlement Commission

Settlement Commission

The Prussian Settlement Commission was a Prussian government commission that operated between 1886 and 1924, but actively only until 1918. It was set up by Otto von Bismarck to increase land ownership by Germans at the expense of Poles, by economic and political means, in the German Empire's...

was set up by Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

to enforce German settlement while at the same time Poles, Jews and Germans migrated west during the Ostflucht

Ostflucht

The Ostflucht was a movement by residents of the former eastern territories of Germany, such as East Prussia, West Prussia, Silesia and Province of Posen beginning around 1850, to the more industrialized western German Rhine and Ruhr provinces...

.

In 1921 the proportion of Germans in Pomerania (where the Corridor was located) was 18.8% (175,771). Over the next decade, the German population decreased by another 70,000 to a share of 9.6%. There was also a Jewish minority. in 1905, Kashubians numbered about 72,500.

After the occupation by Nazi Germany, a census was made by the German authorities in December 1939. 71% of people declared themselves as Poles, 188,000 people declared Kashubian as their language, 100,000 of those declared themselves Polish.

| County | Total population | of which German | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Działdowo (Soldau) | 23,290 | 8,187 | 34.5 % (35.2%) |

| Lubawa Lubawa Lubawa is a town in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland. It is located in Iława County on the Sandela River, some 18 km southeast of Iława.-History:... (Löbau) |

59,765 | 4,478 | 7.6 % |

| Brodnica Brodnica Brodnica is a town in northern Poland with 27,400 inhabitants . Previously part of Toruń Voivodeship [a province], from 1975 to 1998, Brodnica has been situated in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship since 1999... (Strasburg) |

61,180 | 9,599 | 15.7% |

| Wąbrzeźno Wabrzezno Wąbrzeźno is a town in Poland, in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, about 35 km northeast of Toruń. It is the capital of the Wąbrzeźno County... (Briesen) |

47,100 | 14,678 | 31.1% |

| Toruń Torun Toruń is an ancient city in northern Poland, on the Vistula River. Its population is more than 205,934 as of June 2009. Toruń is one of the oldest cities in Poland. The medieval old town of Toruń is the birthplace of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus.... (Thorn) |

79,247 | 16,175 | 20.4% |

| Chełmno (Kulm) | 46,823 | 12,872 | 27.5% |

| Świecie Swiecie Świecie is a town in northern Poland with 25,968 inhabitants , situated in Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship ; it was previously in Bydgoszcz Voivodeship . It is the capital of Świecie County.-History:... (Schwetz) |

83,138 | 20,178 | 24.3% |

| Grudziądz Grudziadz Grudziądz is a city in northern Poland on the Vistula River, with 96 042 inhabitants . Situated in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship , the city was previously in the Toruń Voivodeship .- History :-Early history:... (Graudenz) |

77,031 | 21,401 | 27.8% |

| Tczew Tczew Tczew is a town on the Vistula River in Eastern Pomerania, Kociewie, northern Poland with 60,279 inhabitants . It is an important railway junction with a classification yard dating to the Prussian Eastern Railway... (Dirschau) |

62,905 | 7,854 | 12.5% |

| Wejherowo Wejherowo Wejherowo is a town in Gdańsk Pomerania, northern Poland, with 47,435 inhabitants . It has been the capital of Wejherowo County in Pomeranian Voivodeship since 1999; previously, it was a town in Gdańsk Voivodeship .-History:... (Neustadt) |

71,692 | 7,857 | 11.0% |

| Kartuzy Kartuzy Kartuzy is a town in the historic Eastern Pomerania region of northwestern Poland, located about west of Gdańsk with a population of 15,472... (Karthaus) |

64,631 | 5,037 | 7.8% |

| Kościerzyna Koscierzyna Kościerzyna is a town in Kashubia in Gdańsk Pomerania region, northern Poland, with some 24,000 inhabitants. It has been the capital of Kościerzyna County in Pomeranian Voivodeship since 1999; previously it was in Gdańsk Voivodeship from 1975 to 1998... (Berent) |

49,935 | 9,290 | 18.6% |

| Starogard Gdański Starogard Gdanski Starogard Gdański is a town in Eastern Pomerania in northwestern Poland with 48,328 inhabitants... (Preußisch Stargard) |

62,400 | 5,946 | 9.5% |

| Chojnice Chojnice Chojnice is a town in northern Poland with 39 670 inhabitants , near famous Tuchola Forest, Lake Charzykowskie and many other water reservoirs. It is the capital of the Chojnice County.... (Konitz) |

71,018 | 13,129 | 18.5% |

| Tuchola Tuchola Tuchola is a town in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship in northern Poland. The Pomeranian town, which had a population of 13,976 as of 2004, is located close to the Tuchola Forests about 7t0 km north of Bydgoszcz, and is the seat of Tuchola County... (Tuchel) |

34,445 | 5,660 | 16.4% |

| Sępólno Krajeńskie Sepólno Krajenskie Sępólno Krajeńskie is a town in Poland, in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, about 63 km northwest of Bydgoszcz. It is the capital of Sępólno County and has a population of 9,174 .-History:... (Zempelburg) |

27,876 | 13,430 | 48.2% |

| Total | 935,643 (922,476 when added) |

175,771 |

18.8% (19.1% with 922,476) |

The former corridor area after World War II

At the 1945 Potsdam ConferencePotsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

following the German defeat in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Poland's borders were reorganized at the insistence of the Soviet Union, which occupied the entire area. Territories east of the Oder-Neisse line

Oder-Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, including Danzig, were put under Polish administration. The Potsdam Conference

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

did not debate about the future of the territories that were Part of Western Poland before the war, including the corridor. It automatically became part of the reborn state in 1945.

The corridor in literature

In The Shape of Things to ComeThe Shape of Things to Come

The Shape of Things to Come is a work of science fiction by H. G. Wells, published in 1933, which speculates on future events from 1933 until the year 2106. The book is dominated by Wells's belief in a world state as the solution to mankind's problems....

, published in 1933, H. G.Wells predicted the Corridor as the starting point of a future Second World War.

Similar corridors

Other land corridors linking a country either to the sea or to a remote part of the country are:- Czech CorridorCzech CorridorThe Czech Corridor was a failed proposal during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 in the aftermath of World War I. The proposal would have carved out an area of land to connect Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. A different name often given is Czech-Yugoslav Territorial Corridor...

(concept) - Eilat Corridor (IsraelIsraelThe State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

) - Jerusalem CorridorJerusalem corridorThe Jerusalem corridor is a segment of Israeli territory between the Shephelah and Jerusalem which is home to over 700,000 Israeli Jews. Not including the Arab population of annexed East Jerusalem the areas population is almost 99% Jewish. Roughly stretching from Latrun in the west to Jerusalem in...

(IsraelIsraelThe State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

) - Antofagasta or Atacama corridor (BoliviaBoliviaBolivia officially known as Plurinational State of Bolivia , is a landlocked country in central South America. It is the poorest country in South America...

) - Lachin corridorLachin corridorThe Lachin corridor is a mountain pass within de-jure borders of Azerbaijan, it is the shortest route which connects Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh Republic...

(ArmeniaArmeniaArmenia , officially the Republic of Armenia , is a landlocked mountainous country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia...

/Azerbaidjan) - Siliguri Corridor (IndiaIndiaIndia , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

) - Teen Bigha CorridorTeen Bigha CorridorThe Tin [or Teen] Bigha Corridor is a strip of land belonging to India on the West Bengal–Bangladesh border, which in September, 2011, was leased to Bangladesh so that it can access its Dahagram–Angarpota enclaves...

(BangladeshBangladeshBangladesh , officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh is a sovereign state located in South Asia. It is bordered by India on all sides except for a small border with Burma to the far southeast and by the Bay of Bengal to the south...

) - Wakhan CorridorWakhan CorridorWakhan Corridor is commonly used as a synonym for Wakhan, an area of far north-eastern Afghanistan which forms a land link or "corridor" between Afghanistan and China. The Corridor is a long and slender panhandle or salient, roughly long and between wide. It separates Tajikistan in the north...

(AfghanistanAfghanistanAfghanistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located in the centre of Asia, forming South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. With a population of about 29 million, it has an area of , making it the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world...

, this corridor was not created to link, but to separate areas)