John Burgoyne

Encyclopedia

General

John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British

army officer, politician

and dramatist. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War

when he participated in several battles, mostly notably during the Portugal Campaign

of 1762.

Burgoyne is best known for his role in the American War of Independence. During the Saratoga campaign

he surrendered his army of 5,000 men

to the American troops on October 17, 1777. Appointed to command a force designated to capture Albany

and end the rebellion, Burgoyne advanced from Canada but soon found himself surrounded and outnumbered. He fought two battles at Saratoga

, but was forced to open negotiations with Horatio Gates

. Although he agreed to a convention, on 17 October 1777, which would allow his troops to return home, this was subsequently revoked and his men were made prisoners. Burgoyne faced criticism when he returned to Britain, and never held another active command.

Burgoyne was also an accomplished playwright known for his works such as The Maid of the Oaks

and The Heiress

, but his plays never reached the fame of his military career. He served as a member of the House of Commons of Parliament for a number of years, sitting for the seats of Midhurst

and Preston

. He is often referred to as Gentleman Johnny.

, location of the Burgoyne Baronets

family home Sutton Manor, on 4 February 1723. His mother was Anna Maria Burgoyne the daughter of a wealthy Hackney

merchant. His father was supposedly an army officer, Captain John Burgoyne, although there were rumours that he might be the illegitimate son of Lord Bingley

, who was his godfather

. When Bingley died in 1731 his will specified that Burgoyne was to inherit his estate if his daughters had no male issue.

From the age of ten Burgoyne attended the prestigious Westminster School

, as did many British army officers of the time such as Thomas Gage

with whom Burgoyne would later serve. Burgoyne was athletic

and outgoing and enjoyed life at the school where he made numerous important friends, in particular Lord James Strange. In August 1737 Burgoyne purchased a commission in the Horse Guards

a fashionable cavalry regiment. They were stationed in London and his duties were light, allowing him to cut a figure in high society

. He soon acquired the nickname "Gentleman Johnny" and became well known for his stylish uniforms and general high living which saw him run up large debts. In 1741 Burgoyne sold his commission, possibly to settle gambling

debts.

The outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession

led to an expansion in the size of the British army. In April 1745 Burgoyne joined the newly raised 1st Royal Dragoons as a cornet

, a commission he did not have to pay for as it was newly created. In April 1745 he was promoted to lieutenant

. In 1747 Burgoyne managed to scrape the money together to purchase a captaincy. The end of the war in 1748 cut off any prospect of further active service.

, one of Britain's leading politicians. After Derby refused permission for Burgoyne to marry Charlotte, they eloped together and married without his permission on April 1751. An outraged Derby cut his daughter off without a penny. Unable to support his wife otherwise, Burgoyne again sold his commission, raising £2,600 which they lived off for the next few years.

In October 1751 Burgoyne and his new wife went to live in Continental Europe

travelling through France and Italy. While in France Burgoyne met and befriended the Duc de Choiseul

who would later become the Foreign Minister and directed French policy during the Seven Years War

. While in Rome

Burgoyne had his portrait

painted by the British artist Allan Ramsay. In late 1754 Burgoyne's wife gave birth to a daughter, Charlotte Elizabeth, who was to prove to be the couples' only child. In the hope that a granddaughter would soften Derby's opposition to their marriage the Burgoynes returned to Britain in 1755. Lord Strange interceded on their behalf with Derby, who soon changed his mind and accepted them back into the family. Burgoyne soon became a favourite of Derby, who used his influence to boost Burgoyne's prospects.

Burgoyne bought a commission in the 11th Dragoons

. In 1758 he became captain and lieutenant-colonel in the Coldstream Guards

.

, including the Raid on Cherbourg

. During this period he was instrumental in introducing light cavalry

into the British Army

. The two regiments then formed were commanded by George Eliott

(afterwards Lord Heathfield) and Burgoyne. This was a revolutionary step, and Burgoyne was a pioneer in the early development of British light cavalry. Burgoyne admired independent thought amongst common soldiers, and encouraged his men to use their own initiative, in stark contrast to the established system employed at the time by the British army.

, and in the following year he served as a Brigadier-general in Portugal

which had just entered the war. Burgoyne won particular distinction by leading his cavalry in the capture of Valencia de Alcántara

and of Vila Velha de Ródão

following the Battle of Valencia de Alcántara

, compensating for the Portuguese loss of Almeida

. This played a major part in repulsing a large Spanish force bent on invading Portugal

.

In 1768, he was elected to the House of Commons for Preston

, and for the next few years he occupied himself chiefly with his parliamentary duties, in which he was remarkable for his general outspokenness and, in particular, for his attacks on Lord Clive, who was at the time considered the nation's leading soldier. He achieved prominence in 1772 by demanding an investigation of the East India Company

alleging widespread corruption by its officials. At the same time, he devoted much attention to art and drama (his first play, The Maid of the Oaks

, was produced by David Garrick

in 1775).

in May 1775, a few weeks after the first shots of the war had been fired at Lexington and Concord. He participated as part of the garrison during the Siege of Boston

, although he did not see action at the Battle of Bunker Hill

, in which the British forces were led by William Howe

and Henry Clinton. Frustrated by the lack of opportunities, he returned to England long before the rest of the garrison, which evacuated the city in March 1776.

In 1776, he was at the head of the British reinforcements that sailed up the Saint Lawrence River

and relieved Quebec City

, which was under siege by the Continental Army

. He led forces under General Guy Carleton

in the drive that chased the Continental Army from the province of Quebec

. Carleton then led the British forces onto Lake Champlain

, but was, in Burgoyne's opinion, insufficiently bold when he failed to attempt the capture of Fort Ticonderoga

after winning the naval Battle of Valcour Island

in October.

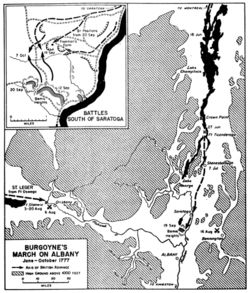

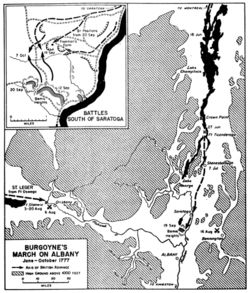

and his government of Carleton's faults, Burgoyne was given command of the British forces charged with gaining control of Lake Champlain and the Hudson River

valley. The plan, largely of his own creation, was for Burgoyne and his force to cross Lake Champlain from Quebec and capture Ticonderoga before advancing on Albany, New York

, where they would rendezvous with another British army under General Howe coming north from New York City

, and a smaller force that would come down the Mohawk River

valley under Barry St. Leger

. This would divide New England

from the southern colonies, and, it was believed, make it easier to end the rebellion.

From the beginning Burgoyne was vastly overconfident. Leading what he believed was an overwhelming force, he saw the campaign largely as a stroll that would make him a national hero who had saved the rebel colonies for the crown. Before leaving London he had wagered Charles James Fox

ten pounds that he would return victorious within a year. He refused to heed more cautious voices, both British

and American

, that suggested a successful campaign using the route he proposed was impossible, as the failed attempt the previous year had shown.

Underlining the plan was the belief that Burgoyne's aggressive thrust from Quebec would be aided by the movements of two other large British forces under Generals Howe and Clinton who would support the advance. However, Lord Germain

's orders dispatched from London were not clear on this point, with the effect that Howe took no action to support Burgoyne, and Clinton moved from New York too late and in too little strength to be any great help to Burgoyne.

As a result of this miscommunication, Burgoyne ended up conducting the campaign largely single-handedly. Even though he was not aware of this yet, he was still reasonably confident of success. Having amassed an army of over 7,000 troops in Quebec, Burgoyne was also led to believe by reports that he could rely on the support of large numbers of Native Americans

and American Loyalists

who would rally to the flag once the British came south. Even if the countryside was not as pro-British as expected, much of the area between Lake Champlain and Albany was underpopulated anyway, and Burgoyne was skeptical any major enemy force could gather there.

The campaign was initially successful. Burgoyne gained possession of the vital outposts of Fort Ticonderoga (for which he was made a lieutenant-general) and Fort Edward

, but, pushing on, decided to break his communications with Quebec, and was eventually hemmed in by a superior force led by American Major General Horatio Gates

. Several attempts to break through the enemy lines were repulsed at Saratoga

in September and October 1777. On 17 October 1777, Burgoyne surrendered his entire army, numbering 5,800. This was the greatest victory the colonists had yet gained, and it proved to be the turning point in the war.

, Burgoyne had agreed to a Convention that involved his men surrendering their weapons, and returning to Europe

with a pledge not to return to North America

. Burgoyne had been most insistent on this point, even suggesting he would try to fight his way back to Quebec if it was not agreed. Soon afterwards the Continental Congress

, urged by George Washington

, repudiated the treaty and imprisoned the remnants of the army in Massachusetts

and Virginia

, where they were sometimes maltreated. This was widely seen as revenge for the poor British treatment of Continental prisoners.

Following Saratoga, the indignation in Britain against Burgoyne was great. He returned at once, with the leave of the American general, to defend his conduct and demanded but never obtained a trial. He was deprived of his regiment and the governorship of Fort William in Scotland

, which he had held since 1769. Following the defeat, France

recognised the United States

and entered the war on 6 February 1778, transforming it into a global conflict.

Although Burgoyne at the time was widely held to blame for the defeat, historians have over the years shifted responsibility for the disaster at Saratoga to Lord Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies

. Germain had overseen the overall strategy for the campaign and had significantly neglected to order General Howe to support Burgoyne's invasion, instead leaving him to believe that he was free to launch his own attack on Philadelphia.

-leaning supporter of the North government

but following his return from Saratoga he began to associate with the Rockingham Whigs

. In 1782 when his political friends came into office, Burgoyne was restored to his rank, given a colonelcy and made commander-in-chief in Ireland

and a privy councillor. After the fall of the Rockingham

government in 1783, Burgoyne withdrew more and more into private life. His last public service was his participation in the Impeachment of Warren Hastings

. He died quite unexpectedly on 3 June 1792 at his home in Mayfair

, after having been seen the previous night at the theatre in apparent good health. Burgoyne is buried in Westminster Abbey

, in the North Walk of the Cloisters.

After the death of his wife in 1776, Burgoyne had four children by his mistress Susan Caulfield; one was Field Marshal John Fox Burgoyne

, father of Hugh Talbot Burgoyne

, VC

.

, writing a number of popular plays. The most notable were The Maid of the Oaks and The Heiress

(1786). He assisted Richard Brinsley Sheridan

in his production of The Camp

, which he may have co-authored. He also wrote the libretti for William Jackson

's only successful opera The Lord of the Manor (1780). He also wrote a translated semi-opera

version of Michel-Jean Sedaine

's work Richard Coeur de lion

with music by Thomas Linley the elder for the Drury Lane Theatre

where it was very successful in 1788. Had it not been for his role in the American War of Independence, Burgoyne would most likely be foremost remembered today as a dramatist.

Burgoyne has made appearances as a character in historical and alternative history

fiction. He appears as a character in George Bernard Shaw

's play The Devil's Disciple

and its 1959 and 1978 film adaptions. Historical novels by Chris Humphreys

that are set during the Saratoga campaign also feature him, while alternate or mystical history versions of his campaign are featured in For Want of a Nail by Robert Sobel

and the 1975 CBS Radio Mystery Theater

play "Windandingo".

General (United Kingdom)

General is currently the highest peace-time rank in the British Army and Royal Marines. It is subordinate to the Army rank of Field Marshal, has a NATO-code of OF-9, and is a four-star rank....

John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

army officer, politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

and dramatist. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War

Great Britain in the Seven Years War

The Kingdom of Great Britain was one of the major participants in the Seven Years' War which lasted between 1756 and 1763. Britain emerged from the war as the world's leading colonial power having gained a number of new territories at the Treaty of Paris in 1763 and established itself as the...

when he participated in several battles, mostly notably during the Portugal Campaign

Spanish invasion of Portugal (1762)

The Spanish invasion of Portugal, between 9 May and 24 November 1762, was the principal military campaign of the Spanish–Portuguese War, 1761–1763, which in turn was part of the larger Seven Years' War...

of 1762.

Burgoyne is best known for his role in the American War of Independence. During the Saratoga campaign

Battle of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga conclusively decided the fate of British General John Burgoyne's army in the American War of Independence and are generally regarded as a turning point in the war. The battles were fought eighteen days apart on the same ground, south of Saratoga, New York...

he surrendered his army of 5,000 men

Convention Army

The Convention Army was an army of British and allied troops captured after the Battles of Saratoga in the American Revolutionary War.-Convention of Saratoga:...

to the American troops on October 17, 1777. Appointed to command a force designated to capture Albany

Albany, New York

Albany is the capital city of the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Albany County, and the central city of New York's Capital District. Roughly north of New York City, Albany sits on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River...

and end the rebellion, Burgoyne advanced from Canada but soon found himself surrounded and outnumbered. He fought two battles at Saratoga

Saratoga, New York

Saratoga is a town in Saratoga County, New York, United States. The population was 5,141 at the 2000 census. It is also the commonly used, but not official, name for the neighboring and much more populous city, Saratoga Springs. The major village in the town of Saratoga is Schuylerville which is...

, but was forced to open negotiations with Horatio Gates

Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates was a retired British soldier who served as an American general during the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga – Benedict Arnold, who led the attack, was finally forced from the field when he was shot in the leg – and...

. Although he agreed to a convention, on 17 October 1777, which would allow his troops to return home, this was subsequently revoked and his men were made prisoners. Burgoyne faced criticism when he returned to Britain, and never held another active command.

Burgoyne was also an accomplished playwright known for his works such as The Maid of the Oaks

The Maid of the Oaks

The Maid of the Oaks is a comedy play by the British playwright and soldier John Burgoyne. It was first staged by David Garrick at Drury Lane Theatre on 5 November 1774. The set designs were by the artist Philip James de Loutherbourg. It was Burgoyne's first work, and he went on to write three...

and The Heiress

The Heiress (1786 play)

The Heiress is a comedy play by the British playwright and soldier John Burgoyne. The play debuted at the Drury Lane Theatre on 14 January 1786. It concerns the engagement of Lord Gayville to Miss Alscrip a fashionable woman he believes to be an heiress. Gayville later discovers that the woman who...

, but his plays never reached the fame of his military career. He served as a member of the House of Commons of Parliament for a number of years, sitting for the seats of Midhurst

Midhurst (UK Parliament constituency)

Midhurst was a parliamentary borough in Sussex, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1311 until 1832, and then one member from 1832 until 1885, when the constituency was abolished...

and Preston

Preston (UK Parliament constituency)

Preston is a borough constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election.-Boundaries:...

. He is often referred to as Gentleman Johnny.

Family and education

John Burgoyne was born in Sutton, BedfordshireSutton, Bedfordshire

Sutton, Bedfordshire, is a small village and civil parish located to the south of Potton, England. Sutton falls under the postal town of Sandy and is also near the market town of Biggleswade.- History :...

, location of the Burgoyne Baronets

Burgoyne Baronets

There have been two creations of Baronetcies for members of the Burgoyne family.The Baronetcy of Burgoyne of Sutton was created in the Baronetage of England on 15 July 1641 for John Burgoyne of Sutton, Bedfordshire....

family home Sutton Manor, on 4 February 1723. His mother was Anna Maria Burgoyne the daughter of a wealthy Hackney

London Borough of Hackney

The London Borough of Hackney is a London borough of North/North East London, and forms part of inner London. The local authority is Hackney London Borough Council....

merchant. His father was supposedly an army officer, Captain John Burgoyne, although there were rumours that he might be the illegitimate son of Lord Bingley

Robert Benson, 1st Baron Bingley

Robert Benson, 1st Baron Bingley, PC was an English politician of the 18th century.-Life:Robert Benson was born in Wakefield. He went to school in London before studying at Christ's College, Cambridge...

, who was his godfather

Godfather

A godfather is a male godparent in the Christian tradition.Godfather may also refer to:*A male arranged to be legal guardian of a child if untimely demise is met by the parentsPeople:* Capo di tutti capi, a Mafia crime boss...

. When Bingley died in 1731 his will specified that Burgoyne was to inherit his estate if his daughters had no male issue.

From the age of ten Burgoyne attended the prestigious Westminster School

Westminster School

The Royal College of St. Peter in Westminster, almost always known as Westminster School, is one of Britain's leading independent schools, with the highest Oxford and Cambridge acceptance rate of any secondary school or college in Britain...

, as did many British army officers of the time such as Thomas Gage

Thomas Gage

Thomas Gage was a British general, best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as military commander in the early days of the American War of Independence....

with whom Burgoyne would later serve. Burgoyne was athletic

Athletic

Athletic may refer to:* An athlete, or sportsperson* Athletic director, a position at many American universities and schools* Athletic type, a physical/psychological type in the classification of Ernst Kretschmer...

and outgoing and enjoyed life at the school where he made numerous important friends, in particular Lord James Strange. In August 1737 Burgoyne purchased a commission in the Horse Guards

Horse Guards Regiment

The Horse Guards Regiment was a regiment only in name: it actually consisted of several independent troops raised initially on the three different establishments...

a fashionable cavalry regiment. They were stationed in London and his duties were light, allowing him to cut a figure in high society

High society

High society may refer to:* Upper class, group of people at the top of a social hierarchy* Gentry, origin Old French genterie, from gentil ‘high-born, noble* High society , social grouping which socialites may be affiliated with....

. He soon acquired the nickname "Gentleman Johnny" and became well known for his stylish uniforms and general high living which saw him run up large debts. In 1741 Burgoyne sold his commission, possibly to settle gambling

Gambling

Gambling is the wagering of money or something of material value on an event with an uncertain outcome with the primary intent of winning additional money and/or material goods...

debts.

The outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession

War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession – including King George's War in North America, the Anglo-Spanish War of Jenkins' Ear, and two of the three Silesian wars – involved most of the powers of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.The...

led to an expansion in the size of the British army. In April 1745 Burgoyne joined the newly raised 1st Royal Dragoons as a cornet

Cornet

The cornet is a brass instrument very similar to the trumpet, distinguished by its conical bore, compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B. It is not related to the renaissance and early baroque cornett or cornetto.-History:The cornet was...

, a commission he did not have to pay for as it was newly created. In April 1745 he was promoted to lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

. In 1747 Burgoyne managed to scrape the money together to purchase a captaincy. The end of the war in 1748 cut off any prospect of further active service.

Elopement

Through his friendship with Lord Strange, Burgoyne came to know Strange's sister Lady Charlotte Stanley, the daughter of Lord DerbyEdward Stanley, 11th Earl of Derby

Edward Stanley, 11th Earl of Derby , known as Sir Edward Stanley, 5th Baronet, from 1714 to 1736, was a British peer and politician....

, one of Britain's leading politicians. After Derby refused permission for Burgoyne to marry Charlotte, they eloped together and married without his permission on April 1751. An outraged Derby cut his daughter off without a penny. Unable to support his wife otherwise, Burgoyne again sold his commission, raising £2,600 which they lived off for the next few years.

In October 1751 Burgoyne and his new wife went to live in Continental Europe

Continental Europe

Continental Europe, also referred to as mainland Europe or simply the Continent, is the continent of Europe, explicitly excluding European islands....

travelling through France and Italy. While in France Burgoyne met and befriended the Duc de Choiseul

Étienne François, duc de Choiseul

Étienne-François, comte de Stainville, duc de Choiseul was a French military officer, diplomat and statesman. Between 1758 and 1761, and 1766 and 1770, he was Foreign Minister of France and had a strong influence on France's global strategy throughout the period...

who would later become the Foreign Minister and directed French policy during the Seven Years War

France in the Seven Years War

France was one of the leading participants in the Seven Years' War which lasted between 1754 and 1763. France entered the war with hopes of achieving a lasting victory both in Europe against Prussia, Britain and their German Allies and across the globe against their major colonial rivals...

. While in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

Burgoyne had his portrait

Portrait

thumb|250px|right|Portrait of [[Thomas Jefferson]] by [[Rembrandt Peale]], 1805. [[New-York Historical Society]].A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expression is predominant. The intent is to display the likeness,...

painted by the British artist Allan Ramsay. In late 1754 Burgoyne's wife gave birth to a daughter, Charlotte Elizabeth, who was to prove to be the couples' only child. In the hope that a granddaughter would soften Derby's opposition to their marriage the Burgoynes returned to Britain in 1755. Lord Strange interceded on their behalf with Derby, who soon changed his mind and accepted them back into the family. Burgoyne soon became a favourite of Derby, who used his influence to boost Burgoyne's prospects.

Seven Years War

A month after the outbreak of the Seven Years' WarSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

Burgoyne bought a commission in the 11th Dragoons

11th Hussars

The 11th Hussars was a cavalry regiment of the British Army.-History:The regiment was founded in 1715 as Colonel Philip Honeywood's Regiment of Dragoons and was known by the name of its Colonel until 1751 when it became the 11th Regiment of Dragoons...

. In 1758 he became captain and lieutenant-colonel in the Coldstream Guards

Coldstream Guards

Her Majesty's Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards, also known officially as the Coldstream Guards , is a regiment of the British Army, part of the Guards Division or Household Division....

.

Raid on St Malo

In 1758 he participated in several expeditions made against the French coastFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, including the Raid on Cherbourg

Raid on Cherbourg

The Raid on Cherbourg took place in August 1758 during the Seven Year's War when a British force was landed on the coast of France by the Royal Navy with the intention of attacking the town of Cherbourg as part of the British government's policy of "descents" on the French Coast.-Background:Since...

. During this period he was instrumental in introducing light cavalry

Light cavalry

Light cavalry refers to lightly armed and lightly armored troops mounted on horses, as opposed to heavy cavalry, where the riders are heavily armored...

into the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. The two regiments then formed were commanded by George Eliott

George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield

George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield, KB was a British Army officer who took served in three major wars during the eighteenth century. He rose to distinction during the Seven Years War when he fought in Germany and participated in the British attacks on Belle Île and Cuba...

(afterwards Lord Heathfield) and Burgoyne. This was a revolutionary step, and Burgoyne was a pioneer in the early development of British light cavalry. Burgoyne admired independent thought amongst common soldiers, and encouraged his men to use their own initiative, in stark contrast to the established system employed at the time by the British army.

Portuguese campaign

In 1761, he sat in parliament for MidhurstMidhurst (UK Parliament constituency)

Midhurst was a parliamentary borough in Sussex, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1311 until 1832, and then one member from 1832 until 1885, when the constituency was abolished...

, and in the following year he served as a Brigadier-general in Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

which had just entered the war. Burgoyne won particular distinction by leading his cavalry in the capture of Valencia de Alcántara

Valencia de Alcántara

Valencia de Alcántara is a Spanish town near the Portuguese border . It is located in Cáceres province.Nuestra Señora de Rocamador is the most important church...

and of Vila Velha de Ródão

Battle of Vila Velha

The Battle of Vila Velha or Battle of Vila Velha de Ródão took place in October 1762 when a British-Portuguese force led by John Burgoyne and Charles Lee surprised and recaptured the town of Vila Velha de Ródão from Spanish invaders during the Seven Years' War as part of the Spanish invasion of...

following the Battle of Valencia de Alcántara

Battle of Valencia de Alcántara

The Battle of Valencia de Alcántara took place in August 1762 when an Anglo Portuguese force led by John Burgoyne surprised and captured the town of Valencia de Alcántara from its Spanish defenders during the Seven Years' War...

, compensating for the Portuguese loss of Almeida

Siege of Almeida (1762)

The Siege of Almeida took place in August 1762 when a Spanish force besieged and captured the city of Almeida from its Portuguese defenders during the Seven Years' War. The city was taken on 25 August as part of the invasion of Portugal by a Spanish army commanded by the Conte De Aranda.The force...

. This played a major part in repulsing a large Spanish force bent on invading Portugal

Spanish invasion of Portugal (1762)

The Spanish invasion of Portugal, between 9 May and 24 November 1762, was the principal military campaign of the Spanish–Portuguese War, 1761–1763, which in turn was part of the larger Seven Years' War...

.

In 1768, he was elected to the House of Commons for Preston

City of Preston, Lancashire

The City of Preston is a city and non-metropolitan district in Lancashire, England. It is located on the north bank of the River Ribble, and was granted city status in 2002, becoming England's 50th city in the 50th year of Queen Elizabeth II's reign...

, and for the next few years he occupied himself chiefly with his parliamentary duties, in which he was remarkable for his general outspokenness and, in particular, for his attacks on Lord Clive, who was at the time considered the nation's leading soldier. He achieved prominence in 1772 by demanding an investigation of the East India Company

East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

alleging widespread corruption by its officials. At the same time, he devoted much attention to art and drama (his first play, The Maid of the Oaks

The Maid of the Oaks

The Maid of the Oaks is a comedy play by the British playwright and soldier John Burgoyne. It was first staged by David Garrick at Drury Lane Theatre on 5 November 1774. The set designs were by the artist Philip James de Loutherbourg. It was Burgoyne's first work, and he went on to write three...

, was produced by David Garrick

David Garrick

David Garrick was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of theatrical practice throughout the 18th century and was a pupil and friend of Dr Samuel Johnson...

in 1775).

Early American War of Independence

In the army he had been promoted to major-general. On the outbreak of the American War of Independence, he was appointed to a command, and arrived in BostonBoston

Boston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

in May 1775, a few weeks after the first shots of the war had been fired at Lexington and Concord. He participated as part of the garrison during the Siege of Boston

Siege of Boston

The Siege of Boston was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War, in which New England militiamen—who later became part of the Continental Army—surrounded the town of Boston, Massachusetts, to prevent movement by the British Army garrisoned within...

, although he did not see action at the Battle of Bunker Hill

Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill took place on June 17, 1775, mostly on and around Breed's Hill, during the Siege of Boston early in the American Revolutionary War...

, in which the British forces were led by William Howe

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, KB, PC was a British army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the American War of Independence...

and Henry Clinton. Frustrated by the lack of opportunities, he returned to England long before the rest of the garrison, which evacuated the city in March 1776.

In 1776, he was at the head of the British reinforcements that sailed up the Saint Lawrence River

Saint Lawrence River

The Saint Lawrence is a large river flowing approximately from southwest to northeast in the middle latitudes of North America, connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean. It is the primary drainage conveyor of the Great Lakes Basin...

and relieved Quebec City

Quebec City

Quebec , also Québec, Quebec City or Québec City is the capital of the Canadian province of Quebec and is located within the Capitale-Nationale region. It is the second most populous city in Quebec after Montreal, which is about to the southwest...

, which was under siege by the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

. He led forces under General Guy Carleton

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, KB , known between 1776 and 1786 as Sir Guy Carleton, was an Irish-British soldier and administrator...

in the drive that chased the Continental Army from the province of Quebec

Province of Quebec (1763-1791)

The Province of Quebec was a colony in North America created by Great Britain after the Seven Years' War. Great Britain acquired Canada by the Treaty of Paris when King Louis XV of France and his advisors chose to keep the territory of Guadeloupe for its valuable sugar crops instead of New France...

. Carleton then led the British forces onto Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain is a natural, freshwater lake in North America, located mainly within the borders of the United States but partially situated across the Canada—United States border in the Canadian province of Quebec.The New York portion of the Champlain Valley includes the eastern portions of...

, but was, in Burgoyne's opinion, insufficiently bold when he failed to attempt the capture of Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga, formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century fort built by the Canadians and the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain in upstate New York in the United States...

after winning the naval Battle of Valcour Island

Battle of Valcour Island

The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island...

in October.

Saratoga campaign

The following year, having convinced King George IIIGeorge III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

and his government of Carleton's faults, Burgoyne was given command of the British forces charged with gaining control of Lake Champlain and the Hudson River

Hudson River

The Hudson is a river that flows from north to south through eastern New York. The highest official source is at Lake Tear of the Clouds, on the slopes of Mount Marcy in the Adirondack Mountains. The river itself officially begins in Henderson Lake in Newcomb, New York...

valley. The plan, largely of his own creation, was for Burgoyne and his force to cross Lake Champlain from Quebec and capture Ticonderoga before advancing on Albany, New York

Albany, New York

Albany is the capital city of the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Albany County, and the central city of New York's Capital District. Roughly north of New York City, Albany sits on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River...

, where they would rendezvous with another British army under General Howe coming north from New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, and a smaller force that would come down the Mohawk River

Mohawk River

The Mohawk River is a river in the U.S. state of New York. It is the largest tributary of the Hudson River. The Mohawk flows into the Hudson in the Capital District, a few miles north of the city of Albany. The river is named for the Mohawk Nation of the Iroquois Confederacy...

valley under Barry St. Leger

Barry St. Leger

Barrimore Matthew "Barry" St. Leger was a British colonel who led an invasion force during the American Revolutionary War.Barry St. Leger was baptised on May 1, 1733, in County Kildare, Ireland. He was the son of Sir John St...

. This would divide New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

from the southern colonies, and, it was believed, make it easier to end the rebellion.

From the beginning Burgoyne was vastly overconfident. Leading what he believed was an overwhelming force, he saw the campaign largely as a stroll that would make him a national hero who had saved the rebel colonies for the crown. Before leaving London he had wagered Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox PC , styled The Honourable from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned thirty-eight years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and who was particularly noted for being the arch-rival of William Pitt the Younger...

ten pounds that he would return victorious within a year. He refused to heed more cautious voices, both British

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

and American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, that suggested a successful campaign using the route he proposed was impossible, as the failed attempt the previous year had shown.

Underlining the plan was the belief that Burgoyne's aggressive thrust from Quebec would be aided by the movements of two other large British forces under Generals Howe and Clinton who would support the advance. However, Lord Germain

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville PC , known as the Hon. George Sackville to 1720, as Lord George Sackville from 1720 to 1770, and as Lord George Germain from 1770 to 1782, was a British soldier and politician who was Secretary of State for America in Lord North's cabinet during the American...

's orders dispatched from London were not clear on this point, with the effect that Howe took no action to support Burgoyne, and Clinton moved from New York too late and in too little strength to be any great help to Burgoyne.

As a result of this miscommunication, Burgoyne ended up conducting the campaign largely single-handedly. Even though he was not aware of this yet, he was still reasonably confident of success. Having amassed an army of over 7,000 troops in Quebec, Burgoyne was also led to believe by reports that he could rely on the support of large numbers of Native Americans

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

and American Loyalists

Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to the Kingdom of Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. At the time they were often called Tories, Royalists, or King's Men. They were opposed by the Patriots, those who supported the revolution...

who would rally to the flag once the British came south. Even if the countryside was not as pro-British as expected, much of the area between Lake Champlain and Albany was underpopulated anyway, and Burgoyne was skeptical any major enemy force could gather there.

The campaign was initially successful. Burgoyne gained possession of the vital outposts of Fort Ticonderoga (for which he was made a lieutenant-general) and Fort Edward

Fort Edward (village), New York

Fort Edward is a village in Washington County, New York, United States. It is part of the Glens Falls Metropolitan Statistical Area. The village population was 3,141 at the 2000 census...

, but, pushing on, decided to break his communications with Quebec, and was eventually hemmed in by a superior force led by American Major General Horatio Gates

Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates was a retired British soldier who served as an American general during the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga – Benedict Arnold, who led the attack, was finally forced from the field when he was shot in the leg – and...

. Several attempts to break through the enemy lines were repulsed at Saratoga

Battle of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga conclusively decided the fate of British General John Burgoyne's army in the American War of Independence and are generally regarded as a turning point in the war. The battles were fought eighteen days apart on the same ground, south of Saratoga, New York...

in September and October 1777. On 17 October 1777, Burgoyne surrendered his entire army, numbering 5,800. This was the greatest victory the colonists had yet gained, and it proved to be the turning point in the war.

Convention Army

Rather than an outright unconditional surrenderUnconditional surrender

Unconditional surrender is a surrender without conditions, in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. In modern times unconditional surrenders most often include guarantees provided by international law. Announcing that only unconditional surrender is acceptable puts psychological...

, Burgoyne had agreed to a Convention that involved his men surrendering their weapons, and returning to Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

with a pledge not to return to North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

. Burgoyne had been most insistent on this point, even suggesting he would try to fight his way back to Quebec if it was not agreed. Soon afterwards the Continental Congress

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates called together from the Thirteen Colonies that became the governing body of the United States during the American Revolution....

, urged by George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, repudiated the treaty and imprisoned the remnants of the army in Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

and Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, where they were sometimes maltreated. This was widely seen as revenge for the poor British treatment of Continental prisoners.

Following Saratoga, the indignation in Britain against Burgoyne was great. He returned at once, with the leave of the American general, to defend his conduct and demanded but never obtained a trial. He was deprived of his regiment and the governorship of Fort William in Scotland

Fort William, Scotland

Fort William is the second largest settlement in the highlands of Scotland and the largest town: only the city of Inverness is larger.Fort William is a major tourist centre with Glen Coe just to the south, Aonach Mòr to the north and Glenfinnan to the west, on the Road to the Isles...

, which he had held since 1769. Following the defeat, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

recognised the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and entered the war on 6 February 1778, transforming it into a global conflict.

Although Burgoyne at the time was widely held to blame for the defeat, historians have over the years shifted responsibility for the disaster at Saratoga to Lord Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies

Secretary of State for the Colonies

The Secretary of State for the Colonies or Colonial Secretary was the British Cabinet minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various colonial dependencies....

. Germain had overseen the overall strategy for the campaign and had significantly neglected to order General Howe to support Burgoyne's invasion, instead leaving him to believe that he was free to launch his own attack on Philadelphia.

Later life

Previously Burgoyne had been a ToryTory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

-leaning supporter of the North government

North Ministry

The North Ministry governed the Kingdom of Great Britain from 1770 until 1782. Overseeing in this time the Falklands Crisis, the Gordon Riots and much of the American War of Independence. It was headed by the Tory politician Lord North and served under George III.-Membership:...

but following his return from Saratoga he began to associate with the Rockingham Whigs

Rockingham Whigs

The Rockingham Whigs or Rockinghamite Whigs in 18th century British politics were a faction of the Whigs led by Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, when he was the opposition leader in the House of Lords during the government of Lord North from 1770 to 1782 and during the two...

. In 1782 when his political friends came into office, Burgoyne was restored to his rank, given a colonelcy and made commander-in-chief in Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

and a privy councillor. After the fall of the Rockingham

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham

Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, KG, PC , styled The Hon. Charles Watson-Wentworth before 1733, Viscount Higham between 1733 and 1746, Earl of Malton between 1746 and 1750 and The Earl Malton in 1750, was a British Whig statesman, most notable for his two terms as Prime...

government in 1783, Burgoyne withdrew more and more into private life. His last public service was his participation in the Impeachment of Warren Hastings

Impeachment of Warren Hastings

The Impeachment of Warren Hastings was a failed attempt to impeach the former Governor-General of India Warren Hastings in the Parliament of Great Britain between 1788 and 1795. Hastings was accused of misconduct during his time in Calcutta particularly relating to mismanagement and personal...

. He died quite unexpectedly on 3 June 1792 at his home in Mayfair

Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster.-History:Mayfair is named after the annual fortnight-long May Fair that took place on the site that is Shepherd Market today...

, after having been seen the previous night at the theatre in apparent good health. Burgoyne is buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

, in the North Walk of the Cloisters.

After the death of his wife in 1776, Burgoyne had four children by his mistress Susan Caulfield; one was Field Marshal John Fox Burgoyne

John Fox Burgoyne

Field Marshal Sir John Fox Burgoyne, 1st Baronet GCB was a British Army officer.-Military career:Burgoyne was the illegitimate son of General John Burgoyne and opera singer Susan Caulfield. In 1798, he was commissioned into the Royal Engineers as a Second Lieutenant...

, father of Hugh Talbot Burgoyne

Hugh Talbot Burgoyne

Captain Hugh Talbot Burgoyne VC RN was an Irish recipient of the Victoria Cross. Born in Dublin, he was the son of John Fox Burgoyne and the grandson of John Burgoyne....

, VC

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross is the highest military decoration awarded for valour "in the face of the enemy" to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries, and previous British Empire territories....

.

Dramatist

In his time Burgoyne was a notable playwrightPlaywright

A playwright, also called a dramatist, is a person who writes plays.The term is not a variant spelling of "playwrite", but something quite distinct: the word wright is an archaic English term for a craftsman or builder...

, writing a number of popular plays. The most notable were The Maid of the Oaks and The Heiress

The Heiress (1786 play)

The Heiress is a comedy play by the British playwright and soldier John Burgoyne. The play debuted at the Drury Lane Theatre on 14 January 1786. It concerns the engagement of Lord Gayville to Miss Alscrip a fashionable woman he believes to be an heiress. Gayville later discovers that the woman who...

(1786). He assisted Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan was an Irish-born playwright and poet and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. For thirty-two years he was also a Whig Member of the British House of Commons for Stafford , Westminster and Ilchester...

in his production of The Camp

The Camp (play)

The Camp: A Musical Entertainment is a 1778 play by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, with assistance from John Burgoyne and David Garrick. The set designs were by Philip James de Loutherbourg...

, which he may have co-authored. He also wrote the libretti for William Jackson

William Jackson (organist born 1730)

William Jackson was an English organist and composer.Jackson was born and died in Exeter, England. He was a pupil of Sylvester, the organist of Exeter Cathedral, and of J. Travers in London. After teaching for years at Exeter, he became organist and choirmaster at the cathedral in 1777...

's only successful opera The Lord of the Manor (1780). He also wrote a translated semi-opera

Semi-opera

The terms Semi-opera, dramatic[k] opera and English opera were all applied to Restoration entertainments that combined spoken plays with masque-like episodes employing singing and dancing characters. They usually included machines in the manner of the restoration spectacular...

version of Michel-Jean Sedaine

Michel-Jean Sedaine

Michel-Jean Sedaine was a French dramatist, was born in Paris.- Biography :His father, who was an architect, died when Sedaine was quite young, leaving no fortune, and the boy began life as a mason's labourer...

's work Richard Coeur de lion

Richard Coeur de Lion (play)

Richard Coeur de Lion: An historical romance is a 1786 semi-opera with an English text by John Burgoyne set to music by Thomas Linley the Elder. It was first staged at Drury Lane Theatre in October 1786. It was a translation of Michel-Jean Sedaine's opera Richard Coeur-de-lion about the life of the...

with music by Thomas Linley the elder for the Drury Lane Theatre

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane is a West End theatre in Covent Garden, in the City of Westminster, a borough of London. The building faces Catherine Street and backs onto Drury Lane. The building standing today is the most recent in a line of four theatres at the same location dating back to 1663,...

where it was very successful in 1788. Had it not been for his role in the American War of Independence, Burgoyne would most likely be foremost remembered today as a dramatist.

Works

- The Dramatic and Poetical Works of the Late Lieut. Gen. J. Burgoyne, London 1808. Facsimile ed., 2 vols. in 1, 1977, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, ISBN 9780820112855.

- The Maid of the OaksThe Maid of the OaksThe Maid of the Oaks is a comedy play by the British playwright and soldier John Burgoyne. It was first staged by David Garrick at Drury Lane Theatre on 5 November 1774. The set designs were by the artist Philip James de Loutherbourg. It was Burgoyne's first work, and he went on to write three...

(1774, staged by David GarrickDavid GarrickDavid Garrick was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of theatrical practice throughout the 18th century and was a pupil and friend of Dr Samuel Johnson...

with music by François Barthélemon) - The CampThe Camp (play)The Camp: A Musical Entertainment is a 1778 play by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, with assistance from John Burgoyne and David Garrick. The set designs were by Philip James de Loutherbourg...

(1778) possible collaboration with Sheridan - The Lord of the ManorThe Lord of the ManorThe Lord of the Manor is a comic opera by the British soldier and playwright John Burgoyne. It was first staged at the Drury Lane Theatre in December 1780. It was written by Burgoyne for his lover the actress Susan Caulfield.-Bibliography:...

(1780) - The HeiressThe Heiress (1786 play)The Heiress is a comedy play by the British playwright and soldier John Burgoyne. The play debuted at the Drury Lane Theatre on 14 January 1786. It concerns the engagement of Lord Gayville to Miss Alscrip a fashionable woman he believes to be an heiress. Gayville later discovers that the woman who...

(1786) - Richard Coeur de LionRichard Coeur de Lion (play)Richard Coeur de Lion: An historical romance is a 1786 semi-opera with an English text by John Burgoyne set to music by Thomas Linley the Elder. It was first staged at Drury Lane Theatre in October 1786. It was a translation of Michel-Jean Sedaine's opera Richard Coeur-de-lion about the life of the...

(1786)

Legacy

John Burgoyne has often been portrayed by historians and commentators as a classic example of the marginally-competent aristocratic British general who acquired his rank through political connections rather than ability. Accounts of the lavish lifestyle he maintained on the Saratoga campaign, combined with a gentlemanly bearing and his career as a playwright led less-than-friendly contemporaries to caricature him, as historian George Billias writes, "a buffoon in uniform who bungled his assignments badly". Much of the historical record, Billias notes, is based upon these characterizations. Billias opines that Burgoyne was a ruthless and risk-taking general with a keen perception of his opponents, and that he was also a perceptive social and political commentator.Burgoyne has made appearances as a character in historical and alternative history

Alternative history

Alternative history may refer to a number of subjects relating to history, the chronology and study of the past. It may mean:* Alternate history, a subgenre of speculative fiction dealing with divergences from the world's actual history...

fiction. He appears as a character in George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

's play The Devil's Disciple

The Devil's Disciple

The Devil's Disciple is an 1897 play written by Irish dramatist, George Bernard Shaw. The play is Shaw's eighth, and after Richard Mansfield's original 1897 American production it was his first financial success, which helped to affirm his career as a playwright...

and its 1959 and 1978 film adaptions. Historical novels by Chris Humphreys

Chris Humphreys

Chris Humphreys is a British actor, playwright and novelist. Born in Toronto, Canada, he was raised in Los Angeles until the age of seven and then grew up in the United Kingdom. For acting he is best known for his role in The Bill where he played PC Richard Turnham from 1989 to 1990...

that are set during the Saratoga campaign also feature him, while alternate or mystical history versions of his campaign are featured in For Want of a Nail by Robert Sobel

Robert Sobel

Robert Sobel was an American professor of history at Hofstra University, and a well-known and prolific writer of business histories.- Biography :...

and the 1975 CBS Radio Mystery Theater

CBS Radio Mystery Theater

CBS Radio Mystery Theater was a radio drama series created by Himan Brown that was broadcast on CBS affiliates from 1974 to 1982....

play "Windandingo".

Sources

- Mintz, Max M. John Burgoyne & Horatio Gates: The Generals of Saratoga. Yale University Press, 1990.

- Stokesbury, James. Burgoyne biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Thomson, Peter. The Cambridge Introduction to English Theatre, 1660-1900. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Further reading

- Shaw, George Bernard. The Devil's Disciple

- Humphreys, Chris. Jack Absolute, The Blooding of Jack Absolute, Absolute Honour.