Huxley family

Encyclopedia

The Huxley family is a British family of which several members have excelled in scientific, medical, artistic, and literary fields. The family also includes members who occupied senior public positions in the service of the United Kingdom

.

The patriarch of the family was the zoologist and comparative anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley (referred to here as THH). THH's grandsons include Aldous Huxley

, author of Brave New World

and Doors of Perception, his brother Julian Huxley

, evolutionist and first director of UNESCO

, and Nobel laureate physiologist Andrew Huxley

.

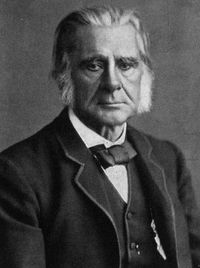

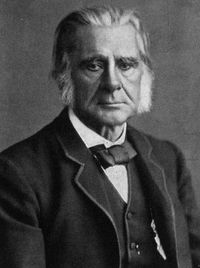

Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895) was an English biologist, known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his defence of Charles Darwin

Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895) was an English biologist, known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his defence of Charles Darwin

's theory of evolution. Mostly a self-educated man, he had an extraordinary influence on the British educated public. He was instrumental in developing scientific education in Britain, and opposed those Christian leaders who tried to stifle scientific debate. He was a member of eight Royal Commission

s and two other commissions. A noted unbeliever, he used the term "agnostic" to describe his attitude to theism

.

Though Huxley was a great comparative anatomist

and invertebrate

zoologist, perhaps his most notable scientific achievement was his work on human evolution

. Starting in 1858, Huxley gave lectures and published papers which analysed the zoological position of man. The best were collected in a landmark work: Evidence as to Man's place in nature

(1863). This contained two themes: first, humans are related to the great apes, and second, the species has evolved in a similar manner to all other forms of life. These were ideas which the careful and cautious Darwin had only hinted at in The Origin of Species

, but with which Huxley was in full agreement.

In 1855, he married Henrietta Anne Heathorn (1825–1915), an English émigrée whom he had met in Sydney

. They had five daughters and three sons:

Huxley's relationship with his relatives and children were quite genial by the standards of the day, so long as they lived their lives in an honourable manner, which some did not. After his mother, his eldest sister Lizzie was the most important person in his life until his own marriage. He remained on good terms with his own children, which is more than can be said of many Victorian fathers.

John Collier

John Collier

was not a Huxley by birth, but by marriage twice over: both his wives were daughters of THH. The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP

ROI

(January 27, 1850–April 11, 1934) was a writer and painter in the Pre-Raphaelite style. He was one of the leading portrait painters of his generation. The National Portrait Gallery's collection of his portraiture is weak, but in 2007 it bought his first wife's portrait of him painting her.

Collier's views on religion and ethics are interesting for their comparison with the views of THH and Julian Huxley, both of whom gave Romanes lecture

s on that subject. In The religion of an artist (1926) Collier explains "It [the book] is mostly concerned with ethics apart from religion... I am looking forward to a time when ethics will have taken the place of religion... My religion is really negative. [The benefits of religion] can be attained by other means which are less conducive to strife and which put less strain on upon the reasoning faculties". On secular morality: "My standard is frankly utilitarian. As far as morality is intuitive, I think it may be reduced to an inherent impulse of kindliness towards our fellow citizens". On the idea of God: "People may claim without much exaggeration that the belief in God is universal. They omit to add that superstition, often of the most degraded kind, is just as universal". And "An omnipotent Deity who sentences even the vilest of his creatures to eternal torture is infinitely more cruel than the cruellest man". And on the Church: "To me, as to most Englishmen, the triumph of Roman Catholicism would mean an unspeakable disaster to the cause of civilization". His views, then, were very close to the agnosticism

of THH and the humanism

of Julian Huxley.

_by_john_collier.jpg) Collier and his first wife Marian (Mady) had one child, Joyce, a portrait miniaturist. She married twice, first to Leslie Crawshay-Williams, whose family were South Wales ironmasters. They had two children Rupert Crawshay-Williams and Gillian. Joyce next married Drysdale Kilburn; they had a son, Nicholas Kilburn.

Collier and his first wife Marian (Mady) had one child, Joyce, a portrait miniaturist. She married twice, first to Leslie Crawshay-Williams, whose family were South Wales ironmasters. They had two children Rupert Crawshay-Williams and Gillian. Joyce next married Drysdale Kilburn; they had a son, Nicholas Kilburn.

By his second wife Ethel he had a daughter and a son, Sir Laurence Collier

KCMG, (1890–1976), British Ambassador to Norway 1939–1950. In later life Ethel became known as The Dragon, and then The Grand-Dragon to her grand-children. She vetted all the family marriages; inspecting Elizabeth Powell for prospective marriage to Rupert Crawshay-Williams (her stepdaughter's son) she said "You are marrying into one of the great atheist families; I know you are an atheist now, but will you be able to keep it up until you die?" The bridegroom started working for Gramophone Records, but became a philosopher and writer. He was the author of The comforts of unreason (1947); Methods and criteria of reasoning (1957) and Russell remembered (1970); a homage to Bertrand Russell

.

Ethel's daughter Joan married Captain (later General) Frank Anstie Buzzard. They had three children: John Huxley Buzzard, Richard Buzzard, and Pamela.

, Julian and Juliette Huxley

, Aldous Huxley

; Henry (Harry) Huxley and his wife, and son Gervas; Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley; and there are others.

Many scientific friends and supporters of Huxley sat for Collier. Darwin and Huxley themselves, twice each – and there were a number of replica portraits of Darwin and Huxley made by Collier. George John Romanes, William Kingdom Clifford, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

, William Spottiswoode

, Sir John Lubbock

, E. Ray Lankester and Sir Michael Foster

were all important friends. Francis Balfour and John Tyndall

were portrayed after their tragic deaths.

(1902–1988) was second cousin once removed of T.H.H. Much of his life was spent in Australia, though he was at Oxford from 1923–30. He obtained his D.Phil from Oxford University in 1928. The final period of his life was spent in Australia, University of Adelaide

(1949–60); Australian National University

(1960–67), latterly as Vice-Chancellor. A key figure in the establishment of the Anglo-Australian Telescope

.

(1860–1933), the most prominent of THH's children, had six children, several of whom left their mark on the twentieth century. He was a teacher (assistant master) at Charterhouse

, then assistant editor and later editor of the Cornhill Magazine

. Huxley's major biographies were the three volumes of Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley and the two volumes of Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

OM GCSI.

His first wife was Julia Arnold (1862–1908), founder in 1902 of Prior's Field School

a still existing girl's school in Godalming, Surrey

. Through her Leonard was connected to the intellectual family of the Arnolds: his wife's father was Tom Arnold

(1823–1900), who married Julia Sorell, granddaughter of a former governor of Tasmania. Julia Arnold's sister was the best-selling novelist Mary

(who wrote as Mrs Humphry Ward), her uncle the poet Matthew Arnold

, and her grandfather the influential Rugby School

headmaster Thomas Arnold

. In her youth she and her sister Ethel had inspired Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) to invent doublet (now called word ladder

).http://www.lewiscarroll.org/news/times060298.html

Leonard and Julia had four children, including the biologist Sir Julian Sorell Huxley

and the writer Aldous Leonard Huxley

. Their middle son, Noel Trevenen (born in 1889) committed suicide in 1914. Their daughter, Margaret Arnold Huxley, was born in 1899 and died on 11 October 1981.

After the death of his first wife, Leonard married Rosalind Bruce (1890–1994), and had two further sons. The elder of these was David Bruce Huxley (born 1915), whose daughter Angela Huxley married George Pember Darwin, son of the physicist Sir Charles Galton Darwin

(and thus a great-grandson of Charles Darwin

married a great-granddaughter of Thomas Huxley

). The younger son (born 1917) was the Nobel prize

winner, physiologist Andrew Fielding Huxley

.

A Plaque was erected in 1995 at the house in Bracknell Gardens, Hampstead to commemorate Leonard, Julian and Aldous 'Men of Science and Letters, lived here.'

Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley

(1887–1975) was the first Director-General of UNESCO

. He was Secretary of Zoological Society and co-founder of the World Wildlife Fund. He won the Darwin Medal

of the Royal Society

, the Darwin-Wallace Medal

of the Linnaean Society, the Kalinga Prize

and the Lasker Award

. He presided over the founding conference for the International Humanist and Ethical Union

. He wrote fifty books.

Julian was important as a proponent of natural selection

at a time when Darwin

's idea was denigrated by many. His master-work Evolution: the modern synthesis

gave the name to a mid-century movement which united biological theory and overcame problems caused by over-specialisation.

Julian married Juliette Baillot in 1919. They had two children, and both became scientists: Anthony Julian Huxley, a botanist and horticulturalist, and Francis Huxley, an anthropologist.

A Wetherspoon Public house in Selsdon

was named after him as he was one of the main backers of the Selsdon Wood

Nature Reserve.

(1894–1963) was an outstanding novelist. His style was iconoclastic

; disenchanted social commentary and a dystopic view of the future were repeated themes. He was regarded in California, where he spent the latter part of his life, as a considerable intellectual guru. He was associated with Vedanta

. His main works include Crome Yellow

(1921), Antic Hay

(1923), Brave New World

(1932), which began as a parody of Men Like Gods

by H.G. Wells, Eyeless in Gaza

(1936) and Island

(1960). Island, his last novel, is a utopia, in profound contrast to Brave New World. The central theme is the development of a society which unites the best of western and eastern culture. It contains, amongst more serious ideas, the utterly charming notion of parrots who utter uplifting slogans. Huxley also wrote many essays: The Doors of Perception

, (1954), is perhaps the best known collection. Its title was taken from a poem by William Blake

, and in turn inspired the name of the band The Doors

.

Aldous married twice, to Maria Nys (1918), and after her death, to Laura Archera

(1956). His only child, Matthew Huxley (1920 – 10 February 2005, age 84) was also an author, as well as an educator, anthropologist and prominent epidemiologist. His work ranged from promoting universal health care to establishing standards of care for nursing home patients and the mentally ill to investigating the question of what is a socially sanctionable drug. Matthew's first marriage, to documentary filmmaker Ellen Hovde, ended in divorce. His second wife died in 1983. He was survived by his third wife, Franziska Reed Huxley; and two children from his first marriage, Trevenen Huxley and Tessa Huxley.

in Africa and Iraq

reaching the rank of Brigade Major

in the British Army

. He became the youngest Queen's Counsel

(QC) in the British Empire

. In Bermuda

in the 1940s and 1950s he was Solicitor General, Attorney General

, and acting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He compiled and revised many of the laws of Bermuda. He married twice and had five children by his first wife. His daughter Angela married George Pember Darwin, and his son Michael became curator of science at the Smithsonian Institution

. In retirement, David and his second wife, Ouida (who was raised by her aunt Ouida Rathbone, married to the actor Basil Rathbone

) lived in Wansford-in-England, Cambridgeshire

, where he served as churchwarden

.

(born 1917), the last child of Leonard Huxley, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

for studies of the central nervous system

, especially the activity of nerve fibres. He was knighted in 1974 and appointed to the Order of Merit

in 1983. He was the second Huxley to be President of the Royal Society

, the first being his grandfather, T.H.H.

In 1947 he married Jocelyn Richenda Gammell Pease (1925–2003), the daughter of the geneticist Michael Pease

and his wife Helen Bowen Wedgwood, the daughter of Josiah Wedgwood IV. They had one son and five daughters:

Janet Rachel Huxley (born 1948);

Stewart Leonard Huxley (born 1949);

Camilla Rosalind Huxley (born 1952);

Eleanor Bruce Huxley (born 1959);

Henrietta Catherine Huxley (born 1960);

Clare Marjory Pease Huxley (born 1962).

when two years old, a disease which had killed her brother Noel. She grew up to marry Frederick Waller, who became architect to the Dean and Chapter of Gloucester Cathedral

and unofficial architect-in-chief to the Huxley family.

Jessie and Fred had a son, Noel Huxley Waller, and a daughter, Oriana Huxley Waller. Noel won the Military Cross

in the Gloucestershire Regiment in World War I

, later becoming Colonel of the 5th Gloucesters, a territorial battalion of the regiment. He succeeded his father as architect to Gloucester Cathedral, and had five children from two marriages. He married, first, Helen Durrant, with Anthony, Audrey, Oriana and Letitia as children. Then he married Marion Taylor, with daughters Marion and Priscilla.

Oriana married E. S. P. Haynes, an Eton

and Balliol

scholar who became a dedicated divorce law reformer. They had three daughters, Renée, Celia and Elvira. Renée, a successful novelist, married Jerrard Tickell

, an Irish writer. They had three sons, one of whom, Crispin, became a distinguished civil servant. The daughter of another son, Patrick, is Dame Clare Tickell

, Chief Executive of Action for Children. Clare Tickell's brother, Adam, is Pro Vice Chancellor at the University of Birmingham

, which grew out of Mason Science College

which Thomas Huxley formally opened in 1880.

GCMG

KCVO

(born 1930) is a British diplomat, academic and environmentalist. He is the great-grandson of Jessica Huxley. He was Chef de Cabinet

to the President of the European Commission

(1977–1980), British Ambassador to Mexico (1981–1983), Permanent Secretary of the Official Development Assistance

(now Department for International Development) (1984–1987), and British Ambassador to the United Nations

and Permanent Representative on the UN Security Council (1987–1990).

Tickell was Warden of Green College, Oxford

, between 1990 and 1997 and is director of the Policy Foresight Programme of the James Martin Institute for Science and Civilization at the University of Oxford

. He has been the recipient, between 1990 and 2006, of 23 honorary doctorates.

He is the president of the UK charity Tree Aid

, which enables communities in Africa's drylands to fight poverty and become self-reliant, while improving the environment. He has many interests, including climate change

, population issues, conservation of biodiversity and the early history of the Earth.

His son, Oliver Tickell

, is a journalist, author and campaigner on environmental issues.

Rachel married, secondly, Harold Shawcross, and they had two children, Betty and Anthony Shawcross. Anthony married Mary Donaldson, and they had three children, Elizabeth, Simon and David.

Henry Huxley, the youngest son and penultimate child of THH, trained in medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital

Henry Huxley, the youngest son and penultimate child of THH, trained in medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital

, London. He married Sophy Stobart, a nurse. As she was the daughter of a considerable landowning and churchgoing family in Yorkshire

, who were somewhat nervous of a connection with the son of a famous infidel, family meetings were held to smooth feelings and avoid difficulties. After the marriage the couple were set up in London, with a medical practice for Henry.

The couple had five children: Marjorie (m. Sir E.J. Harding), Gervas (m. Elspeth), Michael (m. Ottille de Lotbinière Mills, 3c.), Christopher (m. Edmée Ritchie, 3c.) and Anne (m. Geoffrey Cooke, 3c.).

Eldest son of Henry Huxley, served in the British Army

Eldest son of Henry Huxley, served in the British Army

from 1914, became battalion bombing officer. Received the Military Cross

on the first day of Passchendaele for capturing prisoners whose presence showed the arrival of a fresh German Guards Division. Demobilised in 1919.

Gervas was recruited in 1939 to help set up the wartime Ministry of Information. After the war he sat on the Executive Committee of the British Council

, and became a successful author of biographies. He died at Chippenham

in 1971.

Gervas's second marriage was to Elspeth Grant

(1907–1997) in 1931; she had grown up in Kenya

and was a friend of Joy Adamson

. After the marriage she wrote White man's country: Lord Delamere and the making of Kenya

. Her life and work are the subject of a 2002 biography. As an author, Elspeth Huxley was well up to Huxley standards, and one of the few wives who was better-known than her husband. The flame trees of Thika (1959) was perhaps the most celebrated of her thirty books; it was later adapted for television. They had one son, Charles, b.1944.

His favourite daughter, the artistically talented Mady (Marion), who became the first wife of artist John Collier

, was troubled by mental illness for years. By her mid-twenties it was becoming clear that she was not sane, and was getting steadily worse (the diagnosis is uncertain). Huxley persuaded Jean-Martin Charcot

, one of Freud's teachers, to examine her with a view to treatment; but soon Mady died of pneumonia.

About THH himself we have a more complete record. As a young apprentice to a physician, he was taken to watch a post-mortem dissection. Afterwards he sank into a 'deep lethargy' and though he ascribed this to dissection poisoning, Cyril Bibby

and others are probably right to suspect that emotional shock precipitated a clinical depression

. The next episode we know of in his life was on the third voyage of HMS Rattlesnake in 1848. This voyage was mostly to New Guinea

and the NE Australian coast, including the Great Barrier Reef

, which is a kind of wonderland for any zoologist, especially a young man hoping to make his career. The story is clear from the diary Huxley kept: p112 'little interest in the Barrier Reef'; p116 'two entries in seven weeks'; p117 '3 months passed and no journal' p124 'the black months of struggle and depression'. For him to pass up such a golden opportunity speaks of his state of mind.

THH had periods of depression at the end of 1871, alleviated by a cruise to Egypt. And again in 1873, this time coincident with expensive building work on his house. His friends were really alarmed, and his doctor ordered three months rest. Darwin picked up his pen, and with Tyndall's help raised £2,100 for him — an enormous sum. The money was partly to pay for his recuperation, and partly to pay his bills. Huxley set out in July with Hooker to the Auvergne

THH had periods of depression at the end of 1871, alleviated by a cruise to Egypt. And again in 1873, this time coincident with expensive building work on his house. His friends were really alarmed, and his doctor ordered three months rest. Darwin picked up his pen, and with Tyndall's help raised £2,100 for him — an enormous sum. The money was partly to pay for his recuperation, and partly to pay his bills. Huxley set out in July with Hooker to the Auvergne

, and his wife and son Leonard joined him in Cologne

, while the younger children stayed at Down House

in Emma Darwin

's care.

Finally, in 1884 THH sank into another depression, and this time it precipitated his decision to retire in 1885, at the age of only 60. He resigned the Presidency of the Royal Society in mid-term, the Inspectorship of Fisheries, and his chair as soon as he decently could, and took six months' leave. His pension was a fairly handsome £1500 a year.

This is enough to indicate the way depression (or perhaps a moderate bi-polar disorder) interfered with his life, but he was able to function well at other times.

The problems continued sporadically into the third generation. Two of Leonard's sons suffered serious depression: Trevenen committed suicide in 1914 and Julian suffered a number of breakdowns. Of course, there are many family members for whom no information one way or the other is available, but both the talent and the mental problems would have interested Francis Galton

: "The direct result of this enquiry is... to prove that the laws of heredity are as applicable to the mental faculties as to the bodily faculties".

his two sons, Jonathan and Emilio, and Paul Fleiss.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

.

The patriarch of the family was the zoologist and comparative anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley (referred to here as THH). THH's grandsons include Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

, author of Brave New World

Brave New World

Brave New World is Aldous Huxley's fifth novel, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Set in London of AD 2540 , the novel anticipates developments in reproductive technology and sleep-learning that combine to change society. The future society is an embodiment of the ideals that form the basis of...

and Doors of Perception, his brother Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis...

, evolutionist and first director of UNESCO

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations...

, and Nobel laureate physiologist Andrew Huxley

Andrew Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley, OM, FRS is an English physiologist and biophysicist, who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his experimental and mathematical work with Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin on the basis of nerve action potentials, the electrical impulses that enable the activity...

.

Family tree

| Huxley family tree (partial) |

|---|

Thomas Henry Huxley

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

's theory of evolution. Mostly a self-educated man, he had an extraordinary influence on the British educated public. He was instrumental in developing scientific education in Britain, and opposed those Christian leaders who tried to stifle scientific debate. He was a member of eight Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

s and two other commissions. A noted unbeliever, he used the term "agnostic" to describe his attitude to theism

Theism

Theism, in the broadest sense, is the belief that at least one deity exists.In a more specific sense, theism refers to a doctrine concerning the nature of a monotheistic God and God's relationship to the universe....

.

Though Huxley was a great comparative anatomist

Comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of organisms. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny .-Description:...

and invertebrate

Invertebrate

An invertebrate is an animal without a backbone. The group includes 97% of all animal species – all animals except those in the chordate subphylum Vertebrata .Invertebrates form a paraphyletic group...

zoologist, perhaps his most notable scientific achievement was his work on human evolution

Human evolution

Human evolution refers to the evolutionary history of the genus Homo, including the emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species and as a unique category of hominids and mammals...

. Starting in 1858, Huxley gave lectures and published papers which analysed the zoological position of man. The best were collected in a landmark work: Evidence as to Man's place in nature

Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature

Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature is an 1863 book by Thomas Henry Huxley, in which he gives evidence for the evolution of man and apes from a common ancestor. It was the first book devoted to the topic of human evolution, and discussed much of the anatomical and other evidence...

(1863). This contained two themes: first, humans are related to the great apes, and second, the species has evolved in a similar manner to all other forms of life. These were ideas which the careful and cautious Darwin had only hinted at in The Origin of Species

The Origin of Species

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published on 24 November 1859, is a work of scientific literature which is considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology. Its full title was On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the...

, but with which Huxley was in full agreement.

In 1855, he married Henrietta Anne Heathorn (1825–1915), an English émigrée whom he had met in Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

. They had five daughters and three sons:

- Noel Huxley (1856–1860), died aged 4.

- Jessie Oriana Huxley (1856–1927), married architect Fred Waller in 1877.

- Marian Huxley (1859–1887) married artist John CollierJohn Collier (artist)The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI , called 'Jack' by his family and friends, was a leading English artist, and an author. He painted in the Pre-Raphaelite style, and was one of the most prominent portrait painters of his generation. Both his marriages were to daughters of Thomas Henry...

in 1879. - Leonard HuxleyLeonard Huxley (writer)Leonard Huxley was an English schoolteacher, writer and editor.- Family :His father was the zoologist Thomas Henry Huxley, 'Darwin's bulldog'. Leonard was educated at University College School, London, St. Andrews University, and Balliol College, Oxford. He first married Julia Arnold, daughter of...

(1860–1933), married Julia Arnold. - Rachel Huxley (1862–1934) married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884.

- Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer.

- Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London.

- Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.

Huxley's relationship with his relatives and children were quite genial by the standards of the day, so long as they lived their lives in an honourable manner, which some did not. After his mother, his eldest sister Lizzie was the most important person in his life until his own marriage. He remained on good terms with his own children, which is more than can be said of many Victorian fathers.

John Collier (son-in-law)

John Collier (artist)

The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI , called 'Jack' by his family and friends, was a leading English artist, and an author. He painted in the Pre-Raphaelite style, and was one of the most prominent portrait painters of his generation. Both his marriages were to daughters of Thomas Henry...

was not a Huxley by birth, but by marriage twice over: both his wives were daughters of THH. The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP

Royal Society of Portrait Painters

The Royal Society of Portrait Painters is a British association of portrait painters which holds an annual exhibition at the Mall Galleries in London...

ROI

Royal Institute of Oil Painters

The Royal Institute of Oil Painters, also known as ROI, is an association of painters in London and is the only major art society which features work done only in oil. It is a member society of the Federation of British Artists.-History:...

(January 27, 1850–April 11, 1934) was a writer and painter in the Pre-Raphaelite style. He was one of the leading portrait painters of his generation. The National Portrait Gallery's collection of his portraiture is weak, but in 2007 it bought his first wife's portrait of him painting her.

Collier's views on religion and ethics are interesting for their comparison with the views of THH and Julian Huxley, both of whom gave Romanes lecture

Romanes Lecture

The Romanes Lecture is a prestigious free public lecture given annually at the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, England.The lecture series was founded by, and named after, the biologist George Romanes, and has been running since 1892. Over the years, many notable figures from the Arts and Sciences have...

s on that subject. In The religion of an artist (1926) Collier explains "It [the book] is mostly concerned with ethics apart from religion... I am looking forward to a time when ethics will have taken the place of religion... My religion is really negative. [The benefits of religion] can be attained by other means which are less conducive to strife and which put less strain on upon the reasoning faculties". On secular morality: "My standard is frankly utilitarian. As far as morality is intuitive, I think it may be reduced to an inherent impulse of kindliness towards our fellow citizens". On the idea of God: "People may claim without much exaggeration that the belief in God is universal. They omit to add that superstition, often of the most degraded kind, is just as universal". And "An omnipotent Deity who sentences even the vilest of his creatures to eternal torture is infinitely more cruel than the cruellest man". And on the Church: "To me, as to most Englishmen, the triumph of Roman Catholicism would mean an unspeakable disaster to the cause of civilization". His views, then, were very close to the agnosticism

Agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view that the truth value of certain claims—especially claims about the existence or non-existence of any deity, but also other religious and metaphysical claims—is unknown or unknowable....

of THH and the humanism

Humanism

Humanism is an approach in study, philosophy, world view or practice that focuses on human values and concerns. In philosophy and social science, humanism is a perspective which affirms some notion of human nature, and is contrasted with anti-humanism....

of Julian Huxley.

_by_john_collier.jpg)

By his second wife Ethel he had a daughter and a son, Sir Laurence Collier

Laurence Collier

Sir Laurence Collier KCMG was the British ambassador to Norway between 1939 and 1950, including the period when Norway's government was in exile in London during the Second World War....

KCMG, (1890–1976), British Ambassador to Norway 1939–1950. In later life Ethel became known as The Dragon, and then The Grand-Dragon to her grand-children. She vetted all the family marriages; inspecting Elizabeth Powell for prospective marriage to Rupert Crawshay-Williams (her stepdaughter's son) she said "You are marrying into one of the great atheist families; I know you are an atheist now, but will you be able to keep it up until you die?" The bridegroom started working for Gramophone Records, but became a philosopher and writer. He was the author of The comforts of unreason (1947); Methods and criteria of reasoning (1957) and Russell remembered (1970); a homage to Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these things...

.

Ethel's daughter Joan married Captain (later General) Frank Anstie Buzzard. They had three children: John Huxley Buzzard, Richard Buzzard, and Pamela.

Collier's portraits of the family and others

Collier painted numerous portraits of members of the family. He painted both his wives, Marian (Mady) and Ethel; his children; both THH and his wife; and many of the next two generations. Indeed, a biographer reports a total of thirty-two Huxley family portraits during the half-century after his marriage to Mady. His favourite sitter was his eldest daughter Joyce, of whom six portraits are recorded. Second wife Ethel sat for four portraits; their children, Joan and Laurence, the Buzzard children, Laurence's wife Eleanor, and several of their children were also portrayed. Many of Huxley's children and some of his grand-children were portrayed: Leonard HuxleyLeonard Huxley

Leonard Huxley may refer to:* Leonard Huxley , British writer and editor and member of the famous Huxley family* Leonard Huxley , Australian physicist, and also a peripheral member of the Huxley family...

, Julian and Juliette Huxley

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis...

, Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

; Henry (Harry) Huxley and his wife, and son Gervas; Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley; and there are others.

Many scientific friends and supporters of Huxley sat for Collier. Darwin and Huxley themselves, twice each – and there were a number of replica portraits of Darwin and Huxley made by Collier. George John Romanes, William Kingdom Clifford, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM, GCSI, CB, MD, FRS was one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany, and Charles Darwin's closest friend...

, William Spottiswoode

William Spottiswoode

William Spottiswoode FRS was an English mathematician and physicist. He was President of the Royal Society from 1878 to 1883.-Early life:...

, Sir John Lubbock

John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury

John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury PC , FRS , known as Sir John Lubbock, 4th Baronet from 1865 until 1900, was a polymath and Liberal Member of Parliament....

, E. Ray Lankester and Sir Michael Foster

Michael Foster (physiologist)

Sir Michael Foster was an English physiologist.He was born in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire and educated at University College School, London....

were all important friends. Francis Balfour and John Tyndall

John Tyndall

John Tyndall FRS was a prominent Irish 19th century physicist. His initial scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he studied thermal radiation, and produced a number of discoveries about processes in the atmosphere...

were portrayed after their tragic deaths.

Sir Leonard George Holden Huxley (distant cousin)

Sir Leonard George Holden Huxley KBEOrder of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

(1902–1988) was second cousin once removed of T.H.H. Much of his life was spent in Australia, though he was at Oxford from 1923–30. He obtained his D.Phil from Oxford University in 1928. The final period of his life was spent in Australia, University of Adelaide

University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide is a public university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third oldest university in Australia...

(1949–60); Australian National University

Australian National University

The Australian National University is a teaching and research university located in the Australian capital, Canberra.As of 2009, the ANU employs 3,945 administrative staff who teach approximately 10,000 undergraduates, and 7,500 postgraduate students...

(1960–67), latterly as Vice-Chancellor. A key figure in the establishment of the Anglo-Australian Telescope

Anglo-Australian Telescope

The Anglo-Australian Telescope is a 3.9 m equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia at an altitude of a little over 1100 m...

.

Leonard Huxley and issue

Leonard HuxleyLeonard Huxley (writer)

Leonard Huxley was an English schoolteacher, writer and editor.- Family :His father was the zoologist Thomas Henry Huxley, 'Darwin's bulldog'. Leonard was educated at University College School, London, St. Andrews University, and Balliol College, Oxford. He first married Julia Arnold, daughter of...

(1860–1933), the most prominent of THH's children, had six children, several of whom left their mark on the twentieth century. He was a teacher (assistant master) at Charterhouse

Charterhouse School

Charterhouse School, originally The Hospital of King James and Thomas Sutton in Charterhouse, or more simply Charterhouse or House, is an English collegiate independent boarding school situated at Godalming in Surrey.Founded by Thomas Sutton in London in 1611 on the site of the old Carthusian...

, then assistant editor and later editor of the Cornhill Magazine

Cornhill Magazine

The Cornhill Magazine was a Victorian magazine and literary journal named after Cornhill Street in London.Cornhill was founded by George Murray Smith in 1860 and was published until 1975. It was a literary journal with a selection of articles on diverse subjects and serialisations of new novels...

. Huxley's major biographies were the three volumes of Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley and the two volumes of Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM, GCSI, CB, MD, FRS was one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany, and Charles Darwin's closest friend...

OM GCSI.

His first wife was Julia Arnold (1862–1908), founder in 1902 of Prior's Field School

Prior's Field School

Prior’s Field is an independent girls boarding and day school in Godalming, Surrey. It is set in 23 acres of Surrey parkland, 34 miles south west of London and adjacent to the A3. Its original building was designed and developed by Charles Voysey , an English architect of the Arts and Crafts movement...

a still existing girl's school in Godalming, Surrey

Godalming

Godalming is a town and civil parish in the Waverley district of the county of Surrey, England, south of Guildford. It is built on the banks of the River Wey and is a prosperous part of the London commuter belt. Godalming shares a three-way twinning arrangement with the towns of Joigny in France...

. Through her Leonard was connected to the intellectual family of the Arnolds: his wife's father was Tom Arnold

Tom Arnold (academic)

Tom Arnold , also known as Thomas Arnold the Younger, was a British literary scholar.- Life :He was the second son of Thomas Arnold, headmaster of Rugby School, and younger brother of the poet Matthew Arnold...

(1823–1900), who married Julia Sorell, granddaughter of a former governor of Tasmania. Julia Arnold's sister was the best-selling novelist Mary

Mary Augusta Ward

Mary Augusta Ward née Arnold; , was a British novelist who wrote under her married name as Mrs Humphry Ward.- Early life:...

(who wrote as Mrs Humphry Ward), her uncle the poet Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold was a British poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the famed headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, literary professor, and William Delafield Arnold, novelist and colonial administrator...

, and her grandfather the influential Rugby School

Rugby School

Rugby School is a co-educational day and boarding school located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire, England. It is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain.-History:...

headmaster Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold

Dr Thomas Arnold was a British educator and historian. Arnold was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement...

. In her youth she and her sister Ethel had inspired Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) to invent doublet (now called word ladder

Word ladder

A Word Ladder is a word game invented by Lewis Carroll. A word ladder puzzle begins with two words, and to solve the puzzle one must find a chain of other words, where at each step the words differ by altering a single letter.-History:Lewis Carroll says that he invented the game on Christmas day...

).http://www.lewiscarroll.org/news/times060298.html

Leonard and Julia had four children, including the biologist Sir Julian Sorell Huxley

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis...

and the writer Aldous Leonard Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

. Their middle son, Noel Trevenen (born in 1889) committed suicide in 1914. Their daughter, Margaret Arnold Huxley, was born in 1899 and died on 11 October 1981.

After the death of his first wife, Leonard married Rosalind Bruce (1890–1994), and had two further sons. The elder of these was David Bruce Huxley (born 1915), whose daughter Angela Huxley married George Pember Darwin, son of the physicist Sir Charles Galton Darwin

Charles Galton Darwin

Sir Charles Galton Darwin, KBE, MC, FRS was an English physicist, the grandson of Charles Darwin. He served as director of the National Physical Laboratory during the Second World War.-Early life:...

(and thus a great-grandson of Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

married a great-granddaughter of Thomas Huxley

Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley PC FRS was an English biologist, known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution....

). The younger son (born 1917) was the Nobel prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

winner, physiologist Andrew Fielding Huxley

Andrew Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley, OM, FRS is an English physiologist and biophysicist, who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his experimental and mathematical work with Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin on the basis of nerve action potentials, the electrical impulses that enable the activity...

.

A Plaque was erected in 1995 at the house in Bracknell Gardens, Hampstead to commemorate Leonard, Julian and Aldous 'Men of Science and Letters, lived here.'

Sir Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis...

(1887–1975) was the first Director-General of UNESCO

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations...

. He was Secretary of Zoological Society and co-founder of the World Wildlife Fund. He won the Darwin Medal

Darwin Medal

The Darwin Medal is awarded by the Royal Society every alternate year for "work of acknowledged distinction in the broad area of biology in which Charles Darwin worked, notably in evolution, population biology, organismal biology and biological diversity". First awarded in 1890, it was created in...

of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, the Darwin-Wallace Medal

Darwin-Wallace Medal

The Darwin–Wallace Medal is a medal awarded by the Linnean Society of London for "major advances in evolutionary biology". Historically, the medals have been awarded every 50 years, beginning in 1908...

of the Linnaean Society, the Kalinga Prize

Kalinga Prize

The Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science is an award given by UNESCO for exceptional skill in presenting scientific ideas to lay people...

and the Lasker Award

Lasker Award

The Lasker Awards have been awarded annually since 1946 to living persons who have made major contributions to medical science or who have performed public service on behalf of medicine. They are administered by the Lasker Foundation, founded by advertising pioneer Albert Lasker and his wife Mary...

. He presided over the founding conference for the International Humanist and Ethical Union

International Humanist and Ethical Union

The International Humanist and Ethical Union is an umbrella organisation embracing humanist, atheist, rationalist, secular, skeptic, freethought and Ethical Culture organisations worldwide. Founded in Amsterdam in 1952, the IHEU is a democratic union of more than 100 member organizations in 40...

. He wrote fifty books.

Julian was important as a proponent of natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

at a time when Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

's idea was denigrated by many. His master-work Evolution: the modern synthesis

Evolution: The Modern Synthesis

Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, a 1942 book by Julian Huxley , is one of the most important books of the modern evolutionary synthesis.- Publication history :Allen & Unwin, London...

gave the name to a mid-century movement which united biological theory and overcame problems caused by over-specialisation.

Julian married Juliette Baillot in 1919. They had two children, and both became scientists: Anthony Julian Huxley, a botanist and horticulturalist, and Francis Huxley, an anthropologist.

A Wetherspoon Public house in Selsdon

Selsdon

Selsdon is an area located in the southern suburbs of the London Borough of Croydon. The suburb was developed during the inter-war period during the 1920s and 1930s, and is remarkable for its many Art Deco houses...

was named after him as he was one of the main backers of the Selsdon Wood

Selsdon Wood

Selsdon Wood is a woodland area located in the London Borough of Croydon. The park is owned by the National Trust but managed by the London Borough of Croydon. It is a Local Nature Reserve....

Nature Reserve.

Aldous Huxley

Aldous HuxleyAldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

(1894–1963) was an outstanding novelist. His style was iconoclastic

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction of religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually with religious or political motives. It is a frequent component of major political or religious changes...

; disenchanted social commentary and a dystopic view of the future were repeated themes. He was regarded in California, where he spent the latter part of his life, as a considerable intellectual guru. He was associated with Vedanta

Vedanta

Vedānta was originally a word used in Hindu philosophy as a synonym for that part of the Veda texts known also as the Upanishads. The name is a morphophonological form of Veda-anta = "Veda-end" = "the appendix to the Vedic hymns." It is also speculated that "Vedānta" means "the purpose or goal...

. His main works include Crome Yellow

Crome Yellow

Crome Yellow is the first novel by British author Aldous Huxley. It was published in 1921. In the book, Huxley satirises the fads and fashions of the time. It is the witty story of a house party at "Crome"...

(1921), Antic Hay

Antic Hay

Antic Hay is a comic novel by Aldous Huxley, published in 1923. The story takes place in London, and depicts the aimless or self-absorbed cultural elite in the sad and turbulent times following the end of World War I....

(1923), Brave New World

Brave New World

Brave New World is Aldous Huxley's fifth novel, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Set in London of AD 2540 , the novel anticipates developments in reproductive technology and sleep-learning that combine to change society. The future society is an embodiment of the ideals that form the basis of...

(1932), which began as a parody of Men Like Gods

Men Like Gods

Men Like Gods is a novel written in 1923 by H. G. Wells. It features a utopian parallel universe.-Plot summary :The hero of the novel, Mr. Barnstaple, is a depressive journalist working for a newspaper called the Liberal. At the beginning of the story, Barnstaple, as well as a few other...

by H.G. Wells, Eyeless in Gaza

Eyeless in Gaza

Eyeless in Gaza is a bestselling novel by Aldous Huxley, first published in 1936. The title originates from a phrase in John Milton's Samson Agonistes:The chapters of the book are not ordered chronologically...

(1936) and Island

Island (novel)

Island is the final book by English writer Aldous Huxley, published in 1962. It is the account of Will Farnaby, a cynical journalist who is shipwrecked on the fictional island of Pala. Island is Huxley's utopian counterpart to his most famous work, the 1932 novel Brave New World, itself often...

(1960). Island, his last novel, is a utopia, in profound contrast to Brave New World. The central theme is the development of a society which unites the best of western and eastern culture. It contains, amongst more serious ideas, the utterly charming notion of parrots who utter uplifting slogans. Huxley also wrote many essays: The Doors of Perception

The Doors of Perception

The Doors of Perception is a 1954 book by Aldous Huxley detailing his experiences when taking mescaline. The book takes the form of Huxley’s recollection of a mescaline trip which took place over the course of an afternoon, and takes its title from William Blake's poem The Marriage of Heaven and Hell...

, (1954), is perhaps the best known collection. Its title was taken from a poem by William Blake

William Blake

William Blake was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age...

, and in turn inspired the name of the band The Doors

The Doors

The Doors were an American rock band formed in 1965 in Los Angeles, California, with vocalist Jim Morrison, keyboardist Ray Manzarek, drummer John Densmore, and guitarist Robby Krieger...

.

Aldous married twice, to Maria Nys (1918), and after her death, to Laura Archera

Laura Huxley

Laura Huxley was a musician, author, psychological counselor and lecturer.-Life and work:...

(1956). His only child, Matthew Huxley (1920 – 10 February 2005, age 84) was also an author, as well as an educator, anthropologist and prominent epidemiologist. His work ranged from promoting universal health care to establishing standards of care for nursing home patients and the mentally ill to investigating the question of what is a socially sanctionable drug. Matthew's first marriage, to documentary filmmaker Ellen Hovde, ended in divorce. His second wife died in 1983. He was survived by his third wife, Franziska Reed Huxley; and two children from his first marriage, Trevenen Huxley and Tessa Huxley.

David Bruce Huxley

Financier and lawyer (1915–1992). He served in World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

in Africa and Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

reaching the rank of Brigade Major

Brigade Major

In the British Army, a Brigade Major was the Chief of Staff of a brigade. He held the rank of Major and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section directly and oversaw the two other branches, "A - Administration" and "Q - Quartermaster"...

in the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. He became the youngest Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel , known as King's Counsel during the reign of a male sovereign, are lawyers appointed by letters patent to be one of Her [or His] Majesty's Counsel learned in the law...

(QC) in the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. In Bermuda

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British overseas territory in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located off the east coast of the United States, its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, about to the west-northwest. It is about south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and northeast of Miami, Florida...

in the 1940s and 1950s he was Solicitor General, Attorney General

Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general, or attorney-general, is the main legal advisor to the government, and in some jurisdictions he or she may also have executive responsibility for law enforcement or responsibility for public prosecutions.The term is used to refer to any person...

, and acting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He compiled and revised many of the laws of Bermuda. He married twice and had five children by his first wife. His daughter Angela married George Pember Darwin, and his son Michael became curator of science at the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

. In retirement, David and his second wife, Ouida (who was raised by her aunt Ouida Rathbone, married to the actor Basil Rathbone

Basil Rathbone

Sir Basil Rathbone, KBE, MC, Kt was an English actor. He rose to prominence in England as a Shakespearean stage actor and went on to appear in over 70 films, primarily costume dramas, swashbucklers, and, occasionally, horror films...

) lived in Wansford-in-England, Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire is a county in England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the northeast, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire to the west...

, where he served as churchwarden

Churchwarden

A churchwarden is a lay official in a parish church or congregation of the Anglican Communion, usually working as a part-time volunteer. Holders of these positions are ex officio members of the parish board, usually called a vestry, parish council, parochial church council, or in the case of a...

.

Andrew Huxley

Andrew HuxleyAndrew Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley, OM, FRS is an English physiologist and biophysicist, who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his experimental and mathematical work with Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin on the basis of nerve action potentials, the electrical impulses that enable the activity...

(born 1917), the last child of Leonard Huxley, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine administered by the Nobel Foundation, is awarded once a year for outstanding discoveries in the field of life science and medicine. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, in his will...

for studies of the central nervous system

Central nervous system

The central nervous system is the part of the nervous system that integrates the information that it receives from, and coordinates the activity of, all parts of the bodies of bilaterian animals—that is, all multicellular animals except sponges and radially symmetric animals such as jellyfish...

, especially the activity of nerve fibres. He was knighted in 1974 and appointed to the Order of Merit

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

in 1983. He was the second Huxley to be President of the Royal Society

President of the Royal Society

The president of the Royal Society is the elected director of the Royal Society of London. After informal meetings at Gresham College, the Royal Society was founded officially on 15 July 1662 for the encouragement of ‘philosophical studies’, by a royal charter which nominated William Brouncker as...

, the first being his grandfather, T.H.H.

In 1947 he married Jocelyn Richenda Gammell Pease (1925–2003), the daughter of the geneticist Michael Pease

Michael Pease

Michael Stewart Pease OBE was a British classical geneticist at Cambridge University.Pease was the son of Edward Reynolds Pease, writer and a founding member of the Fabian Society, of the Pease family of Quakers...

and his wife Helen Bowen Wedgwood, the daughter of Josiah Wedgwood IV. They had one son and five daughters:

Janet Rachel Huxley (born 1948);

Stewart Leonard Huxley (born 1949);

Camilla Rosalind Huxley (born 1952);

Eleanor Bruce Huxley (born 1959);

Henrietta Catherine Huxley (born 1960);

Clare Marjory Pease Huxley (born 1962).

Jessica Oriana Huxley (1858–1927) and issue

Jessica, the eldest daughter of THH, survived scarlet feverScarlet fever

Scarlet fever is a disease caused by exotoxin released by Streptococcus pyogenes. Once a major cause of death, it is now effectively treated with antibiotics...

when two years old, a disease which had killed her brother Noel. She grew up to marry Frederick Waller, who became architect to the Dean and Chapter of Gloucester Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral, or the Cathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinity, in Gloucester, England, stands in the north of the city near the river. It originated in 678 or 679 with the foundation of an abbey dedicated to Saint Peter .-Foundations:The foundations of the present...

and unofficial architect-in-chief to the Huxley family.

Jessie and Fred had a son, Noel Huxley Waller, and a daughter, Oriana Huxley Waller. Noel won the Military Cross

Military Cross

The Military Cross is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries....

in the Gloucestershire Regiment in World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, later becoming Colonel of the 5th Gloucesters, a territorial battalion of the regiment. He succeeded his father as architect to Gloucester Cathedral, and had five children from two marriages. He married, first, Helen Durrant, with Anthony, Audrey, Oriana and Letitia as children. Then he married Marion Taylor, with daughters Marion and Priscilla.

Oriana married E. S. P. Haynes, an Eton

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

and Balliol

Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College , founded in 1263, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England but founded by a family with strong Scottish connections....

scholar who became a dedicated divorce law reformer. They had three daughters, Renée, Celia and Elvira. Renée, a successful novelist, married Jerrard Tickell

Jerrard Tickell

Edward Jerrard Tickell was an Irish writer known for his novels and World War II historical books.Tickell was born in Dublin and educated in Tipperary and London. He joined the Royal Army Service Corps in 1940 and was commissioned in 1941, when he was appointed to the War Office...

, an Irish writer. They had three sons, one of whom, Crispin, became a distinguished civil servant. The daughter of another son, Patrick, is Dame Clare Tickell

Clare Tickell

Dame Clare Tickell, DBE is the Chief Executive of Action for Children. Before this position she served as:* 1997–2004 Chief Executive, Stonham Housing Association* 1992–1997 Chief Executive, Phoenix House Housing Association...

, Chief Executive of Action for Children. Clare Tickell's brother, Adam, is Pro Vice Chancellor at the University of Birmingham

University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham is a British Redbrick university located in the city of Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Birmingham Medical School and Mason Science College . Birmingham was the first Redbrick university to gain a charter and thus...

, which grew out of Mason Science College

Mason Science College

Mason Science College was founded by Josiah Mason in 1875, the buildings of which were opened in Edmund Street, Birmingham, England on 1 October 1880 by Thomas Henry Huxley...

which Thomas Huxley formally opened in 1880.

Sir Crispin Tickell

Sir Crispin TickellCrispin Tickell

Sir Crispin Tickell, GCMG, KCVO, MA , DSc , FRSGS , FRIBA , FZS, FRI , FCIWEM is a British diplomat, environmentalist, and academic.-Background:...

GCMG

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

KCVO

Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order is a dynastic order of knighthood and a house order of chivalry recognising distinguished personal service to the order's Sovereign, the reigning monarch of the Commonwealth realms, any members of her family, or any of her viceroys...

(born 1930) is a British diplomat, academic and environmentalist. He is the great-grandson of Jessica Huxley. He was Chef de Cabinet

Chef de Cabinet

Chef de Cabinet is the head of an office in the United Nations Secretariat, appointed by the Secretary-General, or in the European Commission, appointed by an individual European Commissioner for his personal cabinet. The position's rank and responsibilities are equivalent to a chief of staff....

to the President of the European Commission

President of the European Commission

The President of the European Commission is the head of the European Commission ― the executive branch of the :European Union ― the most powerful officeholder in the EU. The President is responsible for allocating portfolios to members of the Commission and can reshuffle or dismiss them if needed...

(1977–1980), British Ambassador to Mexico (1981–1983), Permanent Secretary of the Official Development Assistance

Official development assistance

Official development assistance is a term compiled by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to measure aid. The DAC first compiled the term in 1969. It is widely used by academics and journalists as a convenient indicator of...

(now Department for International Development) (1984–1987), and British Ambassador to the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and Permanent Representative on the UN Security Council (1987–1990).

Tickell was Warden of Green College, Oxford

Green College, Oxford

Green College was a graduate college of the University of Oxford in England. It was centred around an architecturally appealing 18th century building: the Radcliffe Observatory, which is modelled after the ancient "Tower of the Winds" in Athens....

, between 1990 and 1997 and is director of the Policy Foresight Programme of the James Martin Institute for Science and Civilization at the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

. He has been the recipient, between 1990 and 2006, of 23 honorary doctorates.

He is the president of the UK charity Tree Aid

Tree Aid

Tree Aid is a forestry focused development charity providing funding and on the ground training and support to local communities in the Sahel of Africa. Tree Aid has a head office in Bristol, UK, and a West African office in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso...

, which enables communities in Africa's drylands to fight poverty and become self-reliant, while improving the environment. He has many interests, including climate change

Climate change

Climate change is a significant and lasting change in the statistical distribution of weather patterns over periods ranging from decades to millions of years. It may be a change in average weather conditions or the distribution of events around that average...

, population issues, conservation of biodiversity and the early history of the Earth.

His son, Oliver Tickell

Oliver Tickell

Oliver Tickell is a British journalist, author and campaigner on health and environment issues, and author of the Kyoto2 climate initiative, supported by a website...

, is a journalist, author and campaigner on environmental issues.

Rachel Huxley (1862–1934) and issue

Rachel Huxley, the fifth of THH's children, married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884, who built railways in various parts of the world. Their eldest son, Roger Huxley Eckersley, was born in Algeria; their second, Thomas Lydwell Eckersley, was born the next year. The family moved to Mexico, and their third son, Peter Eckersley, was born there. All three children married and had issue.Rachel married, secondly, Harold Shawcross, and they had two children, Betty and Anthony Shawcross. Anthony married Mary Donaldson, and they had three children, Elizabeth, Simon and David.

Henry Huxley (1865–1946) and issue

St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as Barts, is a hospital in Smithfield in the City of London, England.-Early history:It was founded in 1123 by Raherus or Rahere , a favourite courtier of King Henry I...

, London. He married Sophy Stobart, a nurse. As she was the daughter of a considerable landowning and churchgoing family in Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, who were somewhat nervous of a connection with the son of a famous infidel, family meetings were held to smooth feelings and avoid difficulties. After the marriage the couple were set up in London, with a medical practice for Henry.

The couple had five children: Marjorie (m. Sir E.J. Harding), Gervas (m. Elspeth), Michael (m. Ottille de Lotbinière Mills, 3c.), Christopher (m. Edmée Ritchie, 3c.) and Anne (m. Geoffrey Cooke, 3c.).

Gervas Huxley CMG MC (1894–1971)

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

from 1914, became battalion bombing officer. Received the Military Cross

Military Cross

The Military Cross is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries....

on the first day of Passchendaele for capturing prisoners whose presence showed the arrival of a fresh German Guards Division. Demobilised in 1919.

Gervas was recruited in 1939 to help set up the wartime Ministry of Information. After the war he sat on the Executive Committee of the British Council

British Council

The British Council is a United Kingdom-based organisation specialising in international educational and cultural opportunities. It is registered as a charity both in England and Wales, and in Scotland...

, and became a successful author of biographies. He died at Chippenham

Chippenham

Chippenham may be:* Chippenham, Wiltshire* Chippenham * Chippenham, Cambridgeshire-See also:* Virginia State Route 150, also known as Chippenham Parkway, USA* Cippenham, Berkshire, UK...

in 1971.

Gervas's second marriage was to Elspeth Grant

Elspeth Huxley

Elspeth Joscelin Huxley CBE was a polymath, writer, journalist, broadcaster, magistrate, environmentalist, farmer, and government advisor. She wrote 30 books; but she is best known for her lyrical books The Flame Trees of Thika and The Mottled Lizard which were based on her experiences growing up...

(1907–1997) in 1931; she had grown up in Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

and was a friend of Joy Adamson

Joy Adamson

Joy Adamson was a naturalist, artist, and author best known for her book, Born Free, which describes her experiences raising a lion cub named Elsa...

. After the marriage she wrote White man's country: Lord Delamere and the making of Kenya

History of Kenya

As part of East Africa, the territory of what is now Kenya has seen human habitation since the beginning of the Lower Paleolithic. The Bantu expansion from a West African center of dispersal reached the area by the 1st millennium AD...

. Her life and work are the subject of a 2002 biography. As an author, Elspeth Huxley was well up to Huxley standards, and one of the few wives who was better-known than her husband. The flame trees of Thika (1959) was perhaps the most celebrated of her thirty books; it was later adapted for television. They had one son, Charles, b.1944.

Mental problems in the family

Biographers have sometimes noted the occurrence of mental illness in the Huxley family. T.H. Huxley's father became "sunk in worse than childish imbecility of mind", and later died in Barming Asylum; brother George suffered from "extreme mental anxiety" and died in 1863 leaving serious debts. Brother James was at 55 "as near mad as any sane man can be".His favourite daughter, the artistically talented Mady (Marion), who became the first wife of artist John Collier

John Collier (artist)

The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI , called 'Jack' by his family and friends, was a leading English artist, and an author. He painted in the Pre-Raphaelite style, and was one of the most prominent portrait painters of his generation. Both his marriages were to daughters of Thomas Henry...

, was troubled by mental illness for years. By her mid-twenties it was becoming clear that she was not sane, and was getting steadily worse (the diagnosis is uncertain). Huxley persuaded Jean-Martin Charcot

Jean-Martin Charcot

Jean-Martin Charcot was a French neurologist and professor of anatomical pathology. He is known as "the founder of modern neurology" and is "associated with at least 15 medical eponyms", including Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis...

, one of Freud's teachers, to examine her with a view to treatment; but soon Mady died of pneumonia.

About THH himself we have a more complete record. As a young apprentice to a physician, he was taken to watch a post-mortem dissection. Afterwards he sank into a 'deep lethargy' and though he ascribed this to dissection poisoning, Cyril Bibby

Cyril Bibby

Cyril Bibby was a biologist and educator. He was also one of the first sexologists.-Early life, family, etc. :...

and others are probably right to suspect that emotional shock precipitated a clinical depression

Clinical depression

Major depressive disorder is a mental disorder characterized by an all-encompassing low mood accompanied by low self-esteem, and by loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities...

. The next episode we know of in his life was on the third voyage of HMS Rattlesnake in 1848. This voyage was mostly to New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

and the NE Australian coast, including the Great Barrier Reef

Great Barrier Reef