August 1911

Encyclopedia

January

- February

- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- August - September

- October

- November

- December

The following events occurred in August 1911:

The following events occurred in August 1911:

January 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1911:-January 1, 1911 :...

- February

February 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in February 1911:-February 1, 1911 :...

- March

March 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1911:-March 1, 1911 :...

- April

April 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1911:-April 1, 1911 :...

- May

May 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in May 1911:-May 1, 1911 :...

- June

June 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1911:-June 1, 1911 :*The Senate voted 48-20 to reopen the investigation of U.S...

- July

July 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1911:-July 1, 1911 :...

- August - September

September 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1911:-September 1, 1911 :*Emilio Estrada was inaugurated as the 23rd President of Ecuador...

- October

October 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1911:-October 1, 1911 :...

- November

November 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1911:-November 1, 1911 :*The first aerial bombardment in history took place when 2d.Lt...

- December

December 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1911:-December 1, 1911 :...

August 1, 1911 (Tuesday)

- Harriet QuimbyHarriet QuimbyHarriet Quimby was an early American aviator and a movie screenwriter. In 1911 she was awarded a U.S. pilot's certificate by the Aero Club of America, becoming the first woman to gain a pilot's license in the United States. In 1912 she became the first woman to fly across the English Channel...

became the first American woman to receive an airplane pilot's license, and only the second in the world (after Raymonde de LarocheRaymonde de LaRocheRaymonde de Laroche , born Elise Raymonde Deroche, was a French aviatrix and the first woman in the world to receive an aeroplane pilot's licence.-Early life:...

). She was one of only 37 certified pilots in the world at that time. - The GMC logo, for General Motors Corporation trucks, was registered for the first time.

- Died: Edwin Austin AbbeyEdwin Austin AbbeyEdwin Austin Abbey was an American artist, illustrator, and painter. He flourished at the beginning of what is now referred to as the "golden age" of illustration, and is best known for his drawings and paintings of Shakespearean and Victorian subjects, as well as for his painting of Edward VII's...

, 59, American painter and designer

August 2, 1911 (Wednesday)

- President François C. Antoine SimonFrançois C. Antoine SimonFrançois C. Antoine Simon was President of Haiti from 6 December 1908 to 3 August 1911. He led a rebellion against Pierre Nord Alexis and succeeded him as president.-Biography:...

of HaitiHaitiHaiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

fled from his palace at Port-au-PrincePort-au-PrincePort-au-Prince is the capital and largest city of the Caribbean nation of Haiti. The city's population was 704,776 as of the 2003 census, and was officially estimated to have reached 897,859 in 2009....

as rebels approached, and took refuge on the Haitian cruiser 17 Decembre. The next day, he and 43 relatives and associates departed on the Dutch steamer Prinz Nederlanden bound for Jamaica. - Born: Ann DvorakAnn DvorakAnn Dvorak was an American film actress.Asked how to pronounce her adopted surname, she told The Literary Digest: "My name is properly pronounced vor'shack. The D remains silent...

, American film actress, as Annabelle McKim in New York City; and Rusty WescoattRusty WescoattRusty Wescoatt was an American supporting actor who appeared in over 80 films between 1947 and 1965, according to the Internet Movie Database. He was born in Hawaii....

, American character actor and bad guy in film, in Hawaii; d. 1987; - Died: Arabella MansfieldArabella MansfieldArabella Mansfield , née Belle Aurelia Babb, became the first female lawyer in the United States when she was admitted to the Iowa bar in 1869. She was allowed to take the bar exam and passed with high scores, despite a state law restricting applicants to white males over 21...

, 65, the first American woman lawyer; and Bob ColeBob Cole (composer)Robert Allen "Bob" Cole was an American composer, actor, playwright, and stage producer and director.In collaboration with Billy Johnson, he wrote and produced A Trip to Coontown , the first musical entirely created and owned by black showmen. The popular song La Hoola Boola was also a result of...

, 43, African-American composer and comedian, by suicide

August 3, 1911 (Thursday)

- The United States signed arbitration treaties with both the United Kingdom and France in separate ceremonies at the White HouseWhite HouseThe White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

office of U.S. President Taft. At 3:10 pm, British Ambassador James BryceJames Bryce, 1st Viscount BryceJames Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce OM, GCVO, PC, FRS, FBA was a British academic, jurist, historian and Liberal politician.-Background and education:...

and U.S. Secretary of State Philander KnoxPhilander C. KnoxPhilander Chase Knox was an American lawyer and politician who served as United States Attorney General , a Senator from Pennsylvania and Secretary of State ....

signed the first pact. French Ambassador Jean Jules JusserandJean Jules JusserandJean Adrien Antoine Jules Jusserand was a French author and diplomat. He was the French ambassador to the United States during World War I.-Career:...

and Knox signed the second treaty. Based on the concept of "unlimited arbitration" of disputes between the three super-powers, the "Taft-Knox Treaties", were favored by the American public, but the U.S. Senate amended both agreements beyond recognition. Taft refused to renegotiate the terms with the other nations. - Allvar GullstrandAllvar GullstrandAllvar Gullstrand was a Swedish ophthalmologist.Born at Landskrona, Sweden, Gullstrand was professor successively of eye therapy and of optics at the University of Uppsala. He applied the methods of physical mathematics to the study of optical images and of the refraction of light in the eye...

first demonstrated the slit lampSlit lampThe slit lamp is an instrument consisting of a high-intensity light source that can be focused to shine a thin sheet of light into the eye. It is used in conjunction with a biomicroscope...

. His invention's introduction has been described as "an occasion of tremendous significance to ophthalmology". - Born: Manuel EsperonManuel EsperónManuel Esperón González was a Mexican song writer and composer. He wrote many songs for Mexican films, including Ay, Jalisco, no te rajes! for the 1941 film of the same name, Cocula for El peñón de las ánimas , and Amor con Amor Se Paga for Hay un niño en su futuro...

, Mexican composer and songwriter, in Mexico CityMexico CityMexico City is the Federal District , capital of Mexico and seat of the federal powers of the Mexican Union. It is a federal entity within Mexico which is not part of any one of the 31 Mexican states but belongs to the federation as a whole...

(d.2011) - Died: Edward Murphy, Jr.Edward Murphy, Jr.Edward Murphy, Jr. was a single term United States Senator from New York, a businessman, and mayor of Troy, New York.-Birth and early years:...

, former U.S. Senator from New York; and Reinhold BegasReinhold BegasReinhold Begas was a German sculptor.Begas was born in Berlin, son of the painter Karl Begas. He received his early education studying under Christian Daniel Rauch and Ludwig Wilhelm Wichmann...

, 90 "the most renowned sculptor in Germany"

August 4, 1911 (Friday)

- Japan's Admiral Count Tōgō HeihachirōTogo HeihachiroFleet Admiral Marquis was a Fleet Admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of Japan's greatest naval heroes. He was termed by Western journalists as "the Nelson of the East".-Early life:...

, commander of the Japanese fleet during the Russo-Japanese War, was welcomed to New York City as a guest of the United States. After arriving the night before on the LusitaniaRMS LusitaniaRMS Lusitania was a British ocean liner designed by Leonard Peskett and built by John Brown and Company of Clydebank, Scotland. The ship entered passenger service with the Cunard Line on 26 August 1907 and continued on the line's heavily-traveled passenger service between Liverpool, England and New...

at 11:40 pm, he transferred to two smaller boats and stayed at the Hotel Knickerbocker. Meeting Mayor William J. GaynorWilliam Jay GaynorWilliam Jay Gaynor was an American politician from New York City, associated with the Tammany Hall political machine. He served as mayor of the City of New York from 1910 to 1913, as well as stints as a New York Supreme Court Justice from 1893 to 1909.-Early life:Gaynor was born in Oriskany, New...

later in the day, he departed on a train for Washington DC that afternoon, where he was hosted at a state dinner by President Taft.

August 5, 1911 (Saturday)

- ColombiaColombiaColombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

n and PeruPeruPeru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

vian troops fought a battle in Caquetá Department, with the Colombian forces being defeated and reportedly sustaining "great losses". - The sinking of an overcrowded passenger boat on the Nile River killed 100 people. Most of the victims were on their way to a festival in Desouk.

- Born: Robert TaylorRobert Taylor (actor)Robert Taylor was an American film and television actor.-Early life:Born Spangler Arlington Brugh in Filley, Nebraska, he was the son of Ruth Adaline and Spangler Andrew Brugh, who was a farmer turned doctor...

, American film and TV actor, as Spangler Brugh in Filley, NebraskaFilley, NebraskaFilley is a village in Gage County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 174 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Filley is located at .According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of , all of it land....

(d. 1969)

August 6, 1911 (Sunday)

- General Cincinnatus LeconteCincinnatus LeconteJean-Jacques Dessalines Michel Cincinnatus Leconte was President of Haiti from August 15, 1911 until his death on August 8, 1912. He was a great-grandson of Jean-Jacques Dessalines—a former African slave who briefly held power as Emperor of Haiti—and an uncle of Joseph Laroche, the only black...

was proclaimed as President of HaitiPresident of HaitiThe President of the Republic of Haiti is the head of state of Haiti. Executive power in Haiti is divided between the president and the government headed by the Prime Minister of Haiti...

, rather than General Anténor Firmin, who had also led an attack on the capital. replacing President Simon. Leconte was formally elected on August 14. - Born: Lucille BallLucille BallLucille Désirée Ball was an American comedian, film, television, stage and radio actress, model, film and television executive, and star of the sitcoms I Love Lucy, The Lucy–Desi Comedy Hour, The Lucy Show, Here's Lucy and Life With Lucy...

, American comedienne and television executive (I Love Lucy); in Celoron, New YorkCeloron, New YorkCeloron is a village in Chautauqua County, New York, United States. It sits on the west boundary of the City of Jamestown, New York and is surrounded by the Town of Ellicott. The population was 1,295 at the 2000 census.- History :...

(a suburb of JamestownJamestown, New YorkJamestown is a city in Chautauqua County, New York in the United States. The population was 31,146 at the 2010 census.The City of Jamestown is adjacent to Town of Ellicott and is at the southern tip of Chautauqua Lake...

(d. 1989); and Constance HeavenConstance HeavenConstance Heaven, née Constance Fecher was a British writer of romance novels from 1963 to 1995, under her maiden name, her married name and under the pseudonym Christina Merlin...

, British romance novelist, in LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

(d. 1995)

August 7, 1911 (Monday)

- Leader of the OppositionLeader of the OppositionThe Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest party not in government in a Westminster System of parliamentary government...

Arthur BalfourArthur BalfourArthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, DL was a British Conservative politician and statesman...

's vote of censure on the government of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith failed to pass in the House of Commons, by a margin of 246 to 365. A similar measure in the House of Lords had passed 282-68. - Born: Nicholas RayNicholas RayNicholas Ray was an American film director best known for the movie Rebel Without a Cause....

, American film director (Rebel Without a Cause), as Raymond Nicholas Kienzle in Galesville, WisconsinGalesville, WisconsinGalesville is a city in Trempealeau County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 1,481 at the 2010 census.Galesville is located where Beaver Creek flows into a wide area of the Mississippi River valley...

(d. 1979) - Died: Elizabeth Chase AllenElizabeth Chase AllenElizabeth Chase Akers Allen was an American author, journalist and poet.-Biography:Born Elizabeth Anne Chase, she grew up in Farmington, Maine, where she attended Farmington Academy...

, 78, American poet

August 8, 1911 (Tuesday)

- Pope Pius XPope Pius XPope Saint Pius X , born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto, was the 257th Pope of the Catholic Church, serving from 1903 to 1914. He was the first pope since Pope Pius V to be canonized. Pius X rejected modernist interpretations of Catholic doctrine, promoting traditional devotional practices and orthodox...

lowered the age for First CommunionFirst CommunionThe First Communion, or First Holy Communion, is a Catholic Church ceremony. It is the colloquial name for a person's first reception of the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. Catholics believe this event to be very important, as the Eucharist is one of the central focuses of the Catholic Church...

in the Roman Catholic ChurchRoman Catholic ChurchThe Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

to seven years old, with the papal decree quam singulari. - The first American newsreelNewsreelA newsreel was a form of short documentary film prevalent in the first half of the 20th century, regularly released in a public presentation place and containing filmed news stories and items of topical interest. It was a source of news, current affairs and entertainment for millions of moviegoers...

, Pathé's WeeklyPathe NewsPathé Newsreels were produced from 1910 until the 1970s, when production of newsreels was in general stopped. Pathé News today is known as British Pathé and its archive of over 90,000 reels is fully digitised and online.-History:...

, was shown in North American cinemas. Promotional material described it as "issued every Tuesday, made up of short scenes of great international events of universal interest from all over the world". - The United States Senate approved statehood for ArizonaArizonaArizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

and New MexicoNew MexicoNew Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

, 53-18. Earlier a proposed amendment by Senator NelsonKnute NelsonKnute Nelson was an Norwegian American politician. A Republican, he served in the Wisconsin Legislature and Minnesota Legislature, in the U.S. House of Representatives, as the 12th Governor of Minnesota, and as a U.S...

of Minnesota, proposing to condition Arizona statehood on removing judicial recall from its constitution, failed 26-43. - Died: William P. FryeWilliam P. FryeWilliam Pierce Frye was an American politician from the U.S. state of Maine. Frye spent most of his political career as a legislator, serving in the Maine House of Representatives and U.S. House of Representatives before being elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served for 30 years and died in...

, 79, U.S. Representative from Maine 1971-1881, and U.S. Senator for five terms, 1881–1911; President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate, 1896–1911

August 9, 1911 (Wednesday)

- Eighty-six people were drowned when the French ship Emir foundered after colliding with the British ship Silverton The ship was passing through the Strait of GibraltarStrait of GibraltarThe Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Spain in Europe from Morocco in Africa. The name comes from Gibraltar, which in turn originates from the Arabic Jebel Tariq , albeit the Arab name for the Strait is Bab el-Zakat or...

, five miles east of TarifaTarifaTarifa is a small town in the province of Cádiz, Andalusia, on the southernmost coast of Spain. The town is located on the Costa de la Luz and across the Straits of Gibraltar facing Morocco. The municipality includes Punta de Tarifa, the southernmost point in continental Europe. There are five...

, after sailing from Gibraltar to Tangier. There were only 15 survivors from the Emir. The Silverton had been on its way from NewportNewportNewport is a city and unitary authority area in Wales. Standing on the banks of the River Usk, it is located about east of Cardiff and is the largest urban area within the historic county boundaries of Monmouthshire and the preserved county of Gwent...

to TarantoTarantoTaranto is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto and is an important commercial port as well as the main Italian naval base....

. - The Australian ship Fifeshire wrecked at Cape GuardafuiCape GuardafuiCape Guardafui , also known as Ras Asir and historically as Aromata promontorium, is a headland in the northeastern Bari province of Somalia. Located in the autonomous Puntland region, it forms the geographical apex of the region commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa.-Location:Cape Guardafui...

in the Gulf of AdenGulf of AdenThe Gulf of Aden is located in the Arabian Sea between Yemen, on the south coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and Somalia in the Horn of Africa. In the northwest, it connects with the Red Sea through the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, which is about 20 miles wide....

, killing 25 people. - A record for the hottest day in the history of the United Kingdom was set when a temperature of 36.7°C (98.1°F) was measured at Raunds, Northamptonshire, EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. The record was broken on August 3, 1990 (37.1°C) and again on August 10, 2003 (38.1°C). - Born: William Alfred FowlerWilliam Alfred FowlerWilliam Alfred "Willy" Fowler was an American astrophysicist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1983. He should not be confused with the British astronomer Alfred Fowler....

, American astrophysicist, who shared the Nobel Prize for Physics, 1983, for his work on stellar nucleosynthesisStellar nucleosynthesisStellar nucleosynthesis is the collective term for the nuclear reactions taking place in stars to build the nuclei of the elements heavier than hydrogen. Some small quantity of these reactions also occur on the stellar surface under various circumstances...

; in Pittsburgh (d. 1995) - Died: John Warne GatesJohn Warne GatesJohn Warne Gates , also known as "Bet-a-Million" Gates, was a pioneer promoter of barbed wire who became a Gilded Age industrialist.-Biography:...

, 56, American financier who went from a salesman of barbed wireBarbed wireBarbed wire, also known as barb wire , is a type of fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strand. It is used to construct inexpensive fences and is used atop walls surrounding secured property...

to a multimillionaire; and George W. Gordon, 75, Commander of the United Confederate VeteransUnited Confederate VeteransThe United Confederate Veterans, also known as the UCV, was a veteran's organization for former Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War, and was equivalent to the Grand Army of the Republic which was the organization for Union veterans....

, and, as U.S. Representative from Tennessee, the last Confederate general to serve in Congress

August 10, 1911 (Thursday)

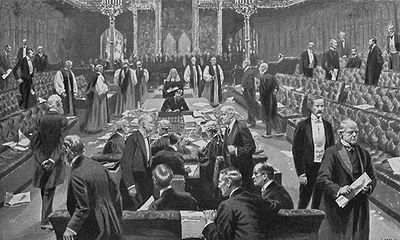

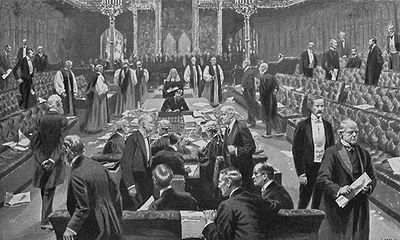

- By a margin of 131-114, the House of LordsHouse of LordsThe House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

passed the Parliament Act 1911Parliament Act 1911The Parliament Act 1911 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords which make up the Houses of Parliament. This Act must be construed as one with the Parliament Act 1949...

, also called the "Veto Bill" because it allowed the United Kingdom House of Commons to put limits on the Lords' power. More than 300 eligible peers declined to participate. However, the 88 Liberal peers were joined in voting in favor by 29 Tories and 13 of the 15 Anglican archbishops and bishops who cast votes. Conservative MP George WyndhamGeorge WyndhamGeorge Wyndham PC was a British Conservative politician, man of letters, noted for his elegance, and one of The Souls.-Background and education:...

would later remark, "We were beaten by the bishops and the rats." - Born: A.N. Sherwin-WhiteA.N. Sherwin-WhiteAdrian Nicholas Sherwin-White was a British historian of Ancient Rome. He was a fellow of St John's College, Oxford, president of the Society for Promotion of Roman Studies, and a fellow of the British Academy...

, British historian, in Fifield, OxfordshireFifield, OxfordshireFifield is a village and civil parish about north of Burford in Oxfordshire.-History:The toponymy is probably a transliteration of its Old English name of Fifhides....

(d. 1993)

August 11, 1911 (Friday)

- U.S. President William H. Taft began a three month long stay away from Washington, D.C., starting with a month long vacation in Beverly, MassachusettsBeverly, MassachusettsBeverly is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 39,343 on , which differs by no more than several hundred from the 39,862 obtained in the 2000 census. A resort, residential and manufacturing community on the North Shore, Beverly includes Beverly Farms and Prides...

, where the Taft family rented Paramatta from Mrs. Lucy Peabody for use as his "Summer White House". On September 15, he began a 15,000 mile tour of 30 of the 46 states, and did not return to the White House until November 12. - Born: Field Marshal Thanom KittikachornThanom KittikachornField Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn was a military dictator of Thailand. A staunch anti-Communist, Thanom oversaw a decade of military rule in Thailand from 1963 to 1973, until public protests which exploded into violence forced him to step down...

, Prime Minister of ThailandPrime Minister of ThailandThe Prime Minister of Thailand is the head of government of Thailand. The Prime Minister is also the chairman of the Cabinet of Thailand. The post has existed since the Revolution of 1932, when the country became a constitutional monarchy....

in 1958, and then again, as a military dictator, from 1963 to 1973 (d. 2004)

August 12, 1911 (Saturday)

- "For a period of one year from and after the date hereof, the landing in Canada shall be, and the same is prohibited, of any immigrants belonging to the Negro race," declared an Order in Council approved by the Cabinet of Prime Minister Wilfrid LaurierWilfrid LaurierSir Wilfrid Laurier, GCMG, PC, KC, baptized Henri-Charles-Wilfrid Laurier was the seventh Prime Minister of Canada from 11 July 1896 to 6 October 1911....

on this date, "which race is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada." The racist order, made in response to hundreds of African-Americans moving to the Canadian prairies from Oklahoma, was never enforced, and repealed on October 5. - Duke KahanamokuDuke KahanamokuDuke Paoa Kahinu Mokoe Hulikohola Kahanamoku was a Hawaiian swimmer, actor, lawman, early beach volleyball player and businessman credited with spreading the sport of surfing. He was a five-time Olympic medalist in swimming.-Early years:The name "Duke" is not a title, but a given name...

broke three world swimming records in his very first meet, in Honolulu. Besides taking 1.6 seconds off of the 50 yard freestyle (to 24.2), he became the first person to swim 100 yards in under a minute, swimming in 55.4 seconds, 4.6 less than the AAU record. - Henry Percival James, British Assistant Commissioner of NigeriaNigeriaNigeria , officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a federal constitutional republic comprising 36 states and its Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The country is located in West Africa and shares land borders with the Republic of Benin in the west, Chad and Cameroon in the east, and Niger in...

, was shot and killed along with five other people while traveling along the Forcados RiverForcados RiverThe Forcados River is a channel in the Niger Delta, in southern Nigeria. It flows for approximately 198 km and meets the sea at the Bight of Benin in Delta State. It is an important channel for small ships...

on government business. - John MuirJohn MuirJohn Muir was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have been read by millions...

set off from Brooklyn to begin a voyage of exploration of the Amazon River. - Born: CantinflasCantinflasFortino Mario Alfonso Moreno Reyes , was a Mexican comic film actor, producer, and screenwriter known professionally as Cantinflas. He often portrayed impoverished campesinos or a peasant of pelado origin...

(real name Fortino Mario Alfonso Moreno Reyes), Mexican film comedian, in Mexico City (d. 1993) - Died: General Jules BrunetJules BrunetJules Brunet was a French officer who played an active role in Mexico and Japan, and later became a General and Chief of Staff of the French Minister of War in 1898...

, 73, Chief of Staff of French Army; Jozef IsraëlsJozef IsraëlsJozef Israëls was a Dutch painter, and "the most respected Dutch artist of the second half of the nineteenth century".-Youth:...

, 87, Dutch painter; and Henry Clay Loudenslager, 59, American Congressman

August 13, 1911 (Sunday)

- A lynch mob in Coatesville, PennsylvaniaCoatesville, PennsylvaniaCoatesville is the only city in Chester County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 13,100 at the 2010 census. Coatesville is approximately 39 miles west of Philadelphia....

, burned an African-American to death after he was accused of murder. Three men were arrested on August 16. The night before, Zachariah Walker had shot and killed Edgar Rice, a private policeman, then injured himself in a suicide attempt while fleeing. While recovering in custody at the local hospital and restrained to a cot, Rice was seized by an angry mob. A fire was set and Walker, still chained to his hospital bed, was tossed into the flames. Pennsylvania Governor John K. TenerJohn K. TenerJohn Kinley Tener was a Major League baseball player and executive and, from 1911 to 1915, served as the 25th Governor of Pennsylvania.-Biography:...

would later say that the charter of Coatesville should be revoked, declaring "Had her officers or her citizens done their duty, the Commonwealth would not have been disgraced and her fair name dishonored." - Matilde E. Moisant became the 3rd woman licensed airplane pilot in history. Unlike the first two, Raymonde de la Roche and Harriet Quimby, Moisant avoided death in a plane crash, and would live (until 1964) to the age of 85.

- Born: William BernbachWilliam BernbachWilliam Bernbach was an American advertising creative director. He was one of the three founders in 1949 of the international advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach...

, American advertising executive and co-founder of Doyle Dayne Bernbach; in New York City (d. 1982); Bert Combs, reformist Governor of Kentucky and federal appellate court judge, in Manchester, KentuckyManchester, KentuckyAs of the census of 2000, there were 1,738 people, 778 households, and 455 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,148.4 people per square mile . There were 844 housing units at an average density of 557.7 per square mile...

(died in accident, 1991)

August 14, 1911 (Monday)

- Edgar Rice BurroughsEdgar Rice BurroughsEdgar Rice Burroughs was an American author, best known for his creation of the jungle hero Tarzan and the heroic Mars adventurer John Carter, although he produced works in many genres.-Biography:...

, a 35 year old salesman for a manufacturer of pencil sharpeners, submitted a partial manuscript to Argosy Magazine, entitled "Dejah Thoris, Martian Princess". The title would be changed and the story lengthened to six installments in All-Story MagazineArgosy (magazine)Argosy was an American pulp magazine, published by Frank Munsey. It is generally considered to be the first American pulp magazine. The magazine began as a general information periodical entitled The Golden Argosy, targeted at the boys adventure market.-Launch of Argosy:In late September 1882,...

with the title Under the Moons of Mars, starting the literary career of Burroughs. - Harry Atwood took off from St. Louis at 7:05 in the morning local time to begin a 1,365 mile trip to New York City. Making 20 stops, and logging 28 1/2 hours flying time, he reached New York at 2:38 pm on August 25.

- Born: Ethel L. PayneEthel L. PayneEthel L. Payne was an African American journalist. Known as the "First Lady of the Black Press", she was a columnist, lecturer, and free-lance writer. She combined advocacy with journalism as she reported on the civil rights movement during the 1950s and 1960s...

, African-American journalist who earned the nickname "First Lady of the Black Press" for her tough reporting for the Chicago Defender (d. 1991)

August 15, 1911 (Tuesday)

- President Taft vetoed the statehood bill for ArizonaArizonaArizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

and New MexicoNew MexicoNew Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

to the 46-state union. Although the veto was directed at Arizona's judicial recall provision, New Mexico was blocked as well because the two states had been included in the same legislation. - Died: Major Henry Reed Rathbone, 74, who was present at the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and had been stabbed by John Wilkes Booth. Rathbone had been imprisoned at the Hildesheim Asylum for the Criminally Insane after murdering his wife while the American Consul at Hanover.

August 16, 1911 (Wednesday)

- Born: E. F. SchumacherE. F. SchumacherErnst Friedrich "Fritz" Schumacher was an internationally influential economic thinker, statistician and economist in Britain, serving as Chief Economic Advisor to the UK National Coal Board for two decades. His ideas became popularized in much of the English-speaking world during the 1970s...

, German economist, in BonnBonnBonn is the 19th largest city in Germany. Located in the Cologne/Bonn Region, about 25 kilometres south of Cologne on the river Rhine in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, it was the capital of West Germany from 1949 to 1990 and the official seat of government of united Germany from 1990 to 1999....

(d. 1977) - Died: Apostol Petkov, Bulgarian guerilla leader, while fighting Ottoman troops BYB-1911

- Died: Patrick Francis Moran, Archbishop of Sydney, Age 80.

August 17, 1911 (Thursday)

- In the USA, President TaftWilliam Howard TaftWilliam Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States...

vetoed the Wool Tariff Reform Bill, an amendment to the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act that would have cut the duty on imported wool in half, reducing the cost of clothing to American consumers. The legislation had passed earlier in the week, 206-90 in the House, but only 38-28 in the Senate. A historian would later write that, in making the veto, "Taft deliberately, knowingly committed the sole enduring mistake of his presidency." - In Britain, civil unrest across the industrial regions continued with the first national railway strike, beginning with the Llanelli Railway Riots. Six men died during the protests that aimed to improve workers rights.

- Born: Mikhail BotvinnikMikhail BotvinnikMikhail Moiseyevich Botvinnik, Ph.D. was a Soviet and Russian International Grandmaster and three-time World Chess Champion. Working as an electrical engineer and computer scientist at the same time, he was one of the very few famous chess players who achieved distinction in another career while...

, World Chess Champion 1948-57, 1958–60 and 1960–63, in KuokkalaRepinoRepino is a municipal settlement in Kurortny District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia, and a station of the Saint Petersburg-Vyborg railroad. It was known by its Finnish name Kuokkala until 1948, when it was renamed after its most famous inhabitant, Ilya Repin...

, Russian Empire (d. 1995); and Martin SandbergerMartin SandbergerMartin Sandberger was an SS Standartenführer and commander of Sonderkommando 1a of the Einsatzgruppe, as well as commander of the Sicherheitspolizei and SD in Estonia. He played an important role in the mass murder of the Jews in the Baltic states...

, German Nazi war criminal, in CharlottenburgCharlottenburgCharlottenburg is a locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, named after Queen consort Sophia Charlotte...

(d. 2010) - Died: Myrtle ReedMyrtle ReedMyrtle Reed was an American author, poet, journalist, and philanthropist, the daughter of author Elizabeth Armstrong Reed and the preacher Hiram von Reed...

, 36, writer of fiction (including Lavender and Old Lace), and cookbooks (as Olive Green); by suicide.

August 18, 1911 (Friday)

- In Indiana, William Perry Woods incorporated the Royal Order of Lions. This was a forerunner of Lions Clubs InternationalLions Clubs InternationalLions Clubs International is a secular service organization with over 44,500 clubs and more than 1,368,683 members in 191 countries around the world founded by Melvin Jones Headquartered in Oak Brook, Illinois, United States, the organization aims to meet the needs of communities on a local and...

(incorporated 1917), the world's largest service club organization, with 1,350,000 members in 45,000 Lions Club chapters. - Royal assent was given to the Veto bill.

- Senate adopted resolution to admit Arizona and New Mexico; House passed bill the next day

- Ten days after the Pathe newsreel debut in the United States, the first Vitagraph newsreel was shown, The Vitagraph Monthly of Current Events.

- Born: Amelia Boynton RobinsonAmelia Boynton RobinsonAmelia Platts Boynton Robinson was a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama. A key figure in the 1965 march that became known as Bloody Sunday, she later became vice-president of the Schiller Institute affiliated with Lyndon LaRouche. She was awarded the Martin Luther King,...

, American civil rights leader, in Savannah, GeorgiaSavannah, GeorgiaSavannah is the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. Established in 1733, the city of Savannah was the colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. Today Savannah is an industrial center and an important...

(still alive in 2011)

August 19, 1911 (Saturday)

- The victory of Emilio EstradaEmilio EstradaEmilio Estrada Carmona was President of Ecuador September 1-December 21, 1911....

over General Flavio Alfaro in elections for President of Ecuador was certified by the Ecuadorian Congress. - The Constitution of the Republic of Portugal was adopted by the National Assembly at 1:35 am.

- The United States Senate voted 53-8 in favor of an amendment to the statehood bill for Arizona and New Mexico, conditioning Arizona's admission into the union on its revocation of a provision to recall elected judges.

- Two hundred Welshmen attacked and looted Jewish shops at Tredegar. On August 21, rioting spread to Ebbw Vale and Rhymney, and then on Tuesday across Wales.

August 20, 1911 (Sunday)

- The New York Times sent the first round-the-world cable message, receiving the text back 16½ minutes after it was sent.

- Lincoln BeacheyLincoln BeacheyLincoln J. Beachey was a pioneer American aviator and barnstormer. He became famous and wealthy from flying exhibitions, staging aerial stunts, helping invent aerobatics, and setting aviation records....

broke the world altitude record, ascending to a height of 11,642 feet, more than 2 miles and more than 3½ km. - Born: Karl FrenzelKarl FrenzelSS-Oberscharführer Karl August Wilhelm Frenzel was the commandant of Sobibor extermination camp's Lager I section, which was the section for the Sonderkommando forced-labor prisoner-workers, who also herded victims into the gas chambers...

, German Nazi war criminal who commanded the Sobibor extermination campSobibór extermination campSobibor was a Nazi German extermination camp located on the outskirts of the town of Sobibór, Lublin Voivodeship of occupied Poland as part of Operation Reinhard; the official German name was SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor...

; in ZehdenickZehdenickZehdenick is a town in the Oberhavel district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is situated on the river Havel, 26 km southeast of Fürstenberg/Havel, and 51 km north of Berlin .-Subdivision:Zehdenick includes the following villages:...

(died of natural causes, 1996)

August 21, 1911 (Monday)

- The Mona LisaMona LisaMona Lisa is a portrait by the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. It is a painting in oil on a poplar panel, completed circa 1503–1519...

was stolen from the Louvre Museum while the museum was closed for cleaning. Witnesses reported that a tall stout individual had been carrying what appeared to be a large panel covered with a horse blanket, then caught the Paris to Bordeaux express at 7:47 am as it was pulling out of the Quai d'Orsay station. Two years later, Vincenzo PeruggiaVincenzo PeruggiaVincenzo Peruggia was the man who stole the Mona Lisa.-Theft:In 1911 Vincenzo Peruggia perpetrated what has been described as the greatest art theft of the 20th century. The former Louvre worker hid inside the museum on Sunday, August 20, knowing that the museum would be closed the following day...

, an Italian patriot who claimed that he stole the painting to return it to the homeland of Leonardo da VinciLeonardo da VinciLeonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance...

, was arrested in FlorenceFlorenceFlorence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

and the world's most famous painting was recovered. - At 3:08 pm, President Taft signed the joint resolution offering American statehood to ArizonaArizonaArizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

and New MexicoNew MexicoNew Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

. - Former U.S. President Theodore RooseveltTheodore RooseveltTheodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

announced that he would not consent to use of his name as a possible candidate in 1912. - Sir James WhitneyJames WhitneySir James Pliny Whitney, KCMG was a politician in the Canadian province of Ontario. Whitney was a lawyer in eastern Ontario, Conservative member for Dundas from 1888 to 1914, and the sixth Premier of Ontario from 1905 to 1914.- Early life :Whitney was born in Williamsburgh Township in 1843 and...

, the Premier of OntarioPremier of OntarioThe Premier of Ontario is the first Minister of the Crown for the Canadian province of Ontario. The Premier is appointed as the province's head of government by the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, and presides over the Executive council, or Cabinet. The Executive Council Act The Premier of Ontario...

, announced that he opposed the reciprocity bill with the United States because he believed that it would lead to annexation. - Born: Anthony BoucherAnthony BoucherAnthony Boucher was an American science fiction editor and author of mystery novels and short stories. He was particularly influential as an editor. Between 1942 and 1947 he acted as reviewer of mostly mystery fiction for the San Francisco Chronicle...

, mystery and science fiction author, as William Anthony White in Oakland, California - Died: William Rotch Wister, 84, "the father of American cricket". Wister had founded the Philadelphia Cricket Club after watching English mill workers playing the game in 1842.

August 22, 1911 (Tuesday)

- The former Shah of Persia was routed at SavadkuhSavadkuh CountySavadkuh County is a county in Mazandaran Province in Iran. At the 2006 census, the county's population was 66,430, in 17,918 families. The county is subdivided into two districts: the Central District and Shirgah District...

with the loss of 300 of his men. - In Britain, the Official Secrets ActOfficial Secrets Act 1911The Official Secrets Act 1911 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It replaces the Official Secrets Act 1889....

is commenced by parliamentary.

August 23, 1911 (Wednesday)

- A secret meeting of the Committee of Imperial DefenceCommittee of Imperial DefenceThe Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ad hoc part of the government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of World War II...

was convened by Prime Minister Asquith to discuss overall military strategy for war against Germany. Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson and Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson, the leaders of the British Army and the Royal Navy, respectively, presented their opposing views on how a war in continental Europe should be conducted. - Born: Betty RobinsonBetty RobinsonElizabeth Robinson , later Elizabeth R. Schwartz was an American athlete and winner of the first Olympic 100 m for women....

, American athlete and winner of first women's 100 meter in the Summer Olympics; gold medalist 1928 and 1936; holder of 100m world record and "fastest woman on Earth", 1928–1932; (d. 1999); and Birger RuudBirger RuudBirger Ruud was a Norwegian ski jumper.Born in Kongsberg, Birger Ruud, with his brothers Sigmund and Asbjørn, dominated international jumping in the 1930s, winning three world championships in 1931, 1935 and 1937. Ruud also won the Olympic gold medal in 1932 and 1936...

, Norwegian ski jumper, Olympic gold medalist 1932 and 1936, world champion 1931, 1935 and 1937; in KongsbergKongsbergis a town and municipality in Buskerud county, Norway. It is located at the southern end of the traditional region of Numedal. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Kongsberg....

(d. 1998)

August 24, 1911 (Thursday)

- Led by the organization Tung Chi Huei, Chinese citizens living in ChengduChengduChengdu , formerly transliterated Chengtu, is the capital of Sichuan province in Southwest China. It holds sub-provincial administrative status...

walked off of their jobs in protest over the Imperial Government's agreement with foreign nations to build a railroad through the SichuanSichuan' , known formerly in the West by its postal map spellings of Szechwan or Szechuan is a province in Southwest China with its capital in Chengdu...

Province, after businesses there had raised $20,000,000 to build it themselves. "Few people in this country realized when the brief telegrams reported the occurrence of a strike," wrote an American author later,"that the beginning of the end of the Manchu Dynasty had arrived." The Xinhai RevolutionXinhai RevolutionThe Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, also known as Revolution of 1911 or the Chinese Revolution, was a revolution that overthrew China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing , and established the Republic of China...

would begin six weeks later. - Manuel de ArriagaManuel de ArriagaManuel José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira e Peyrelongue was a Portuguese lawyer, the first Attorney-General and the first elected President of the First Portuguese Republic, following the abdication of King Manuel II of Portugal and a Republican Provisional Government headed by Teófilo Braga Manuel...

, Procurator General of Portugal was elected the first President of PortugalPresident of PortugalPortugal has been a republic since 1910, and since that time the head of state has been the president, whose official title is President of the Portuguese Republic ....

, receiving 121 votes from the Constituent Assembly. In second place was Foreign Minister Bernardo Machado, with 86 votes. Arriaga had been a Professor at Columbia University and had taught English to the late King Carlos of PortugalCarlos I of Portugal-Assassination:On 1 February 1908 the royal family returned from the palace of Vila Viçosa to Lisbon. They travelled by train to Barreiro and, from there, they took a steamer to cross the Tagus River and disembarked at Cais do Sodré in central Lisbon. On their way to the royal palace, the open...

. - The first shipment of coal was made from Harlan County, KentuckyHarlan County, KentuckyHarlan County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It was formed in 1819. As of 2000, the population was 33,200. Its county seat is Harlan...

, the beginning of its transformation into a major coal producer. The influx of miners and their families raised the population from 11,000 to 31,500 in ten years, and to 75,000 by 1940, before declining to 29,000 by 2011. - Born: Frederick E. Nolting, Jr., U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam (1961-63) in Richmond, VirginiaRichmond, VirginiaRichmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

(d. 1989)

August 25, 1911 (Friday)

- Andre Jaeger-SchmidtNellie BlyNellie Bly was the pen name of American pioneer female journalist Elizabeth Jane Cochran. She remains notable for two feats: a record-breaking trip around the world in emulation of Jules Verne's character Phileas Fogg, and an exposé in which she faked insanity to study a mental institution from...

made good on his bet to travel around the world in 40 days, arriving at Cherbourg at 11:15 pm, in Paris 4 hours and 17 minutes ahead of schedule. - Harry Atwood completed his flight from St. Louis to New York, covering 1,265 miles in 11 days, setting a new distance record.

- Twenty-eight people were killed and 74 injured in a train wreck at Manchester, New YorkManchester, New YorkManchester, New York is both a town and a village located in Ontario County, New York.*Manchester , New York*Manchester , New York...

. Two passenger cars on the Lehigh Valley Train No. 4Lehigh Valley RailroadThe Lehigh Valley Railroad was one of a number of railroads built in the northeastern United States primarily to haul anthracite coal.It was authorized April 21, 1846 in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and incorporated September 20, 1847 as the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill and Susquehanna Railroad...

fell from the track into a ravine after encountering a section of track weakened by metal fatigue. Many of the dead and injured were veterans of the American Civil War and other members of the Grand Army of the RepublicGrand Army of the RepublicThe Grand Army of the Republic was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army, US Navy, US Marines and US Revenue Cutter Service who served in the American Civil War. Founded in 1866 in Decatur, Illinois, it was dissolved in 1956 when its last member died...

organization, on their way to an encampment in Rochester. - George SantayanaGeorge SantayanaGeorge Santayana was a philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. A lifelong Spanish citizen, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States and identified himself as an American. He wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters...

address coined a term in "The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy" in an address to the Philosophical Union of the University of California at Berkeley - Count Katsura TarōKatsura TaroPrince , was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, politician and three-time Prime Minister of Japan.-Early life:Katsura was born into a samurai family from Hagi, Chōshū Domain...

resigned as Prime Minister of JapanPrime Minister of JapanThe is the head of government of Japan. He is appointed by the Emperor of Japan after being designated by the Diet from among its members, and must enjoy the confidence of the House of Representatives to remain in office...

, along with his entire cabinet. - Born: Vo Nguyen GiapVo Nguyen GiapVõ Nguyên Giáp is a retired Vietnamese officer in the Vietnam People’s Army and a politician. He was a principal commander in two wars: the First Indochina War and the Vietnam War...

, North Vietnamese General who guided the Communist victory in the Vietnam War; in An Xa, Quảng Bình ProvinceQuang Binh ProvinceQuảng Bình , formerly Tiên Bình under the reign of Le Trung Hung of the Lê Dynasty, this province was renamed Quảng Bình in 1604) is a province in the North Central Coast of Vietnam....

(still living in 2011) - Died: William S. HutchingsWilliam S. HutchingsWilliam S. Hutchings, also known as Professor Hutchings and the Lightning Calculator, was a 19th century math prodigy and mental calculator who P. T. Barnum first billed as the "Boy Lightning Calculator"...

, 80, the "lightning calculator" for P.T. Barnum's circus.

August 26, 1911 (Saturday)

- Twenty-six people were killed at the Morgan Opera House, a movie theatre in Canonsburg, PennsylvaniaCanonsburg, PennsylvaniaCanonsburg is a borough in Washington County, Pennsylvania, southwest of Pittsburgh. Canonsburg was laid out by Colonel John Canon in 1789 and incorporated in 1802....

, after a false alarm of fire. At 8:15 pm, 800 people were watching a film when it flared up and a cry of alarm was made. - At the Indian Head, Maryland, proving grounds of the U.S. Navy, an anti-aircraft shell was fired to a record high altitude, 18,000 feet.

- The Argentine battleship ARA RivadaviaARA RivadaviaARA Rivadavia"ARA" is an acronym for Armada de la República Argentina was a battleship of the Argentine Navy. Named after the first Argentine president, Bernardino Rivadavia, she was the lead ship of her class and the third dreadnought built during the South American dreadnought race...

, largest in the world, was launched at the Fore River ShipyardFore River ShipyardThe Fore River Shipyard of Quincy, Massachusetts, more formally known as the Fore River Ship and Engine Building Company, was a shipyard in the United States from 1883 until 1986. Located on the Weymouth Fore River, the yard began operations in 1883 in Braintree, Massachusetts before being moved...

in Quincy, MassachusettsQuincy, MassachusettsQuincy is a city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. Its nicknames are "City of Presidents", "City of Legends", and "Birthplace of the American Dream". As a major part of Metropolitan Boston, Quincy is a member of Boston's Inner Core Committee for the Metropolitan Area Planning Council...

. Mme. Naon, wife of the Argentine Ambassador to the United States, broke the champagne bottle over the bow at 1:58 pm.

August 27, 1911 (Sunday)

- Quoting from astronomer Percival LowellPercival LowellPercival Lawrence Lowell was a businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, and formed the beginning of the effort that led to the discovery of Pluto 14 years after his death...

, the New York Times reported that "vast engineering works" had been "accomplished in an incredibly short time by our planetary neighbors", referring to canals built on the planet Mars by its inhabitants. The Times noted that in two years, straight chasms had been built that were 20 miles wide and 1,000 miles in length. - The phrase "our place in the sun", describing one's belief in an entitlement, was first used by Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II in a speech delivered at Hamburg "No one can dispute with us the place in the sun that is our due", borrowed from Blaise Pascal's Pensees.

- Fifteen people were killed by a hurricane at Charleston, South CarolinaCharleston, South CarolinaCharleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

. - Born: Van Rensselaer PotterVan Rensselaer PotterVan Rensselaer Potter II was an American biochemist. He was professor of oncology at the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison for more than 50 years....

, developer of study of bioethicsBioethicsBioethics is the study of controversial ethics brought about by advances in biology and medicine. Bioethicists are concerned with the ethical questions that arise in the relationships among life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, politics, law, and philosophy....

; in Pierpont, South DakotaPierpont, South DakotaPierpont is a town in Day County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 135 at the 2010 census.-Geography:Pierpont is located at ....

(d. 2001); Johnny EckJohnny EckJohnny Eck, born John Eckhardt, Jr. was an American freak show performer born with the appearance that he was missing the lower half of his torso. Eck is best known today for his role in Tod Browning's 1932 cult classic film, Freaks...

, real name John Eckhardt, Jr.; American acrobat and sideshow performer who overcame a birth defect, walking on his hands after being born without legs; billed by Robert Ripley as "The Most Remarkable Man in the World" , in BaltimoreBaltimoreBaltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

(d. 1991)

August 28, 1911 (Monday)

- The United States acquired the four small Causeway IslandsCauseway IslandsCauseway Islands are four small islands by the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal, they were linked to the mainland via a causeway, made from rock extracted during the excavations from the Panama Canal...

(Flamenco, Culebra, Naos and Perico) at the western end of the Panama CanalPanama CanalThe Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

. Later named collectively for the causewayCausewayIn modern usage, a causeway is a road or railway elevated, usually across a broad body of water or wetland.- Etymology :When first used, the word appeared in a form such as “causey way” making clear its derivation from the earlier form “causey”. This word seems to have come from the same source by...

that connected them to the mainland, the islands reverted to Panamanian control when the Panama Canal ZonePanama Canal ZoneThe Panama Canal Zone was a unorganized U.S. territory located within the Republic of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending 5 miles on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón, which otherwise would have been partly within the limits of...

was transferred in 1979 - Born: Joseph LunsJoseph LunsJoseph Marie Antoine Hubert Luns was a Dutch politician and diplomat of the defunct Catholic People's Party now merged into the Christian Democratic Appeal . He was the longest-serving Minister of Foreign Affairs from September 2, 1952 until July 6, 1971...

, Foreign Minister of the Netherlands, 1952–1971, Secretary General of NATOSecretary General of NATOThe Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation is the chairman of the North Atlantic Council, the supreme decision-making organisation of the defence alliance. The Secretary-General also serves as the leader of the organisation's staff and as its chief spokesman...

, 1971–1984; in RotterdamRotterdamRotterdam is the second-largest city in the Netherlands and one of the largest ports in the world. Starting as a dam on the Rotte river, Rotterdam has grown into a major international commercial centre...

(d. 2002)

August 29, 1911 (Tuesday)

- "IshiIshiIshi was the last member of the Yahi, the last surviving group of the Yana people of the U.S. state of California. Ishi is believed to have been the last Native American in Northern California to have lived most of his life completely outside the European American culture...

", the last surviving member of the Yahi American Indian tribe and last speaker of the Yana languageYana languageYana is an extinct language isolate formerly spoken in north-central California between the Feather and Pit rivers in what is now Shasta and Tehama counties....

, was discovered hiding in a corral near Oroville, CaliforniaOroville, CaliforniaOroville is the county seat of Butte County, California. The population was 15,506 at the 2010 census, up from 13,004 at the 2000 census...

. Ishi lived the rest of his life as the guest of Professor Alfred Kroeber, curator of the Museum of Anthropology in San Francisco, and died in 1916. - Died: Mahbub Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VI, 45, richest prince of the Indian Empire. As the Nizam of Hyderabad, he had an income of $10,000,000 a year and ruled over 11 million subjects. He was succeeded by his 25 year old son, Osman Ali Khan.

August 30, 1911 (Wednesday)

- The Director of the U.S. Census Bureau announced that the center of population in the United States had been calculated incorrectly, at that it was located in the western part of Bloomington, IndianaBloomington, IndianaBloomington is a city in and the county seat of Monroe County in the southern region of the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 80,405 at the 2010 census....

, eight miles from the originally announced center in Brown County, Indiana. - The Marquis Saionji KinmochiSaionji KinmochiPrince was a Japanese politician, statesman and twice Prime Minister of Japan. His title does not signify the son of an emperor, but the highest rank of Japanese hereditary nobility; he was elevated from marquis to prince in 1920...

became the new Prime MinisterPrime ministerA prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

of Japan. - Francisco I. MaderoFrancisco I. MaderoFrancisco Ignacio Madero González was a politician, writer and revolutionary who served as President of Mexico from 1911 to 1913. As a respectable upper-class politician, he supplied a center around which opposition to the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz could coalesce...

was formally nominated for President of MexicoPresident of MexicoThe President of the United Mexican States is the head of state and government of Mexico. Under the Constitution, the president is also the Supreme Commander of the Mexican armed forces...

as a candidate for the National Progressive Party. - Sir William RamsayWilliam RamsaySir William Ramsay was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air" .-Early years:Ramsay was born in Glasgow on 2...

predicted that Britain's coal supplies would be exhausted by 2086. - Born: Arsenio RodríguezArsenio RodríguezArsenio Rodríguez was a Cuban musician who played the tres , reorganized the conjunto and developed the son montuno, and other Afro-Cuban rhythms in the 1940s and 50s...

, blind Cuban musician who popularized mambo (d. 1970); and Robert Gibney, Bell Labs chemist who helped perfect the transistor; in Wilmington, DelawareWilmington, DelawareWilmington is the largest city in the state of Delaware, United States, and is located at the confluence of the Christina River and Brandywine Creek, near where the Christina flows into the Delaware River. It is the county seat of New Castle County and one of the major cities in the Delaware Valley...

August 31, 1911 (Thursday)

- Died: Brigadier General Benjamin GriersonBenjamin GriersonBenjamin Henry Grierson was a music teacher and then a career officer in the United States Army. He was a cavalry general in the volunteer Union Army during the American Civil War and later led troops in the American Old West...

, 85, Union cavalry leader during the American Civil War, and later organizer and commander of the African-American 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army