Augustan prose

Encyclopedia

Poetry

Poetry is a form of literary art in which language is used for its aesthetic and evocative qualities in addition to, or in lieu of, its apparent meaning...

. However, the general time represented by Augustan literature

Augustan literature

Augustan literature is a style of English literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II on the 1740s with the deaths of Pope and Swift...

saw a rise in prose writing as high literature. The essay

Essay

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author's personal point of view. Essays can consist of a number of elements, including: literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. The definition...

, satire, and dialogue

Dialogue

Dialogue is a literary and theatrical form consisting of a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people....

(in philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

and religion) thrived in the age, and the English novel

English novel

The English novel is an important part of English literature.-Early novels in English:A number of works of literature have each been claimed as the first novel in English. See the article First novel in English.-Romantic novel:...

was truly begun as a serious art form. At the outset of the Augustan age, essays were still primarily imitative, novels were few and still dominated by the Romance, and prose was a rarely used format for satire, but, by the end of the period, the English essay was a fully formed periodical feature, novels surpassed drama as entertainment and as an outlet for serious authors, and prose was serving every conceivable function in public discourse. It is the age that most provides the transition from a court-centered and poetic literature to a more democratic, decentralized literary world of prose.

The precondition of literacy

Literacy rates in the early 18th century are difficult to estimate accurately. However, it appears that literacy was much higher than school enrollment would indicate and that literacy passed into the working classes, as well as the middle and upper classes (Thompson). The churches emphasized the need for every Christian to read the BibleBible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

, and instructions to landlords indicated that it was their duty to teach servants and workers how to read and to have the Bible read aloud to them. Furthermore, literacy does not appear to be confined to men, though rates of female literacy are very difficult to establish. Even where workers were not literate, however, some prose works enjoyed currency well beyond the literate, as works were read aloud to the illiterate.

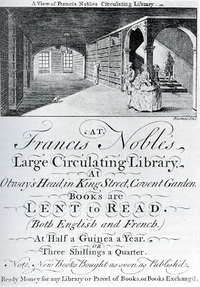

For those who were literate, circulating libraries

Library

In a traditional sense, a library is a large collection of books, and can refer to the place in which the collection is housed. Today, the term can refer to any collection, including digital sources, resources, and services...

in England began in the Augustan period. The first was probably at Bath in 1725, but they spread very rapidly. Libraries purchased sermon collections and books on manners, and they were open to all, but they were associated with female patronage and novel reading. Circulating libraries were a way for women, in particular, to satisfy their desire for books without facing the expense of purchase. Inasmuch as books were still regarded principally as tools for work, any book that existed merely for entertainment was subject to a charge of frivolity. Therefore, the sales of novels and light entertainments testify to a very strong demand for these books indeed.

The essay/journalism

MontesquieuCharles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu

Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu , generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French social commentator and political thinker who lived during the Enlightenment...

's "essais" were available to English authors in the 18th century, both in French and in translation, and he exerted an influence on several later authors, both in terms of content and form, but the English essay developed independently from continental tradition. At the end of the Restoration, periodical literature began to be popular. These were combinations of news with reader's questions and commentary on the manners and news of the day. Since periodicals were inexpensive to produce, quick to read, and a viable way of influencing public opinion, their numbers increased dramatically after the success of The Athenian Mercury (flourished in the 1690s but published in book form in 1709). In the early years of the 18th century, most periodicals served as a way for a collection of friends to offer up a relatively consistent political point of view, and these periodicals were under the auspices of a bookseller.

However, one periodical outsold and dominated all others and set out an entirely new philosophy for essay writing, and that was The Spectator

The Spectator

The Spectator is a weekly British magazine first published on 6 July 1828. It is currently owned by David and Frederick Barclay, who also owns The Daily Telegraph. Its principal subject areas are politics and culture...

, written by Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was a man of letters, eldest son of Lancelot Addison...

and Richard Steele

Richard Steele

Sir Richard Steele was an Irish writer and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine The Spectator....

. By 1711, when The Spectator began, there was already a thriving industry of periodical literature in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, but The Spectator was far and away the most successful and significant periodical of the era. Each issue was a single, folio

Paper size

Many paper size standards conventions have existed at different times and in different countries. Today there is one widespread international ISO standard and a localised standard used in North America . The paper sizes affect writing paper, stationery, cards, and some printed documents...

sheet of paper, printed front and back, sometimes with advertisements, and issues were not only read throughout London, but also were carried out to the countryside. Up to twenty years after publication stopped, people were counting collections of the issues among their inheritable goods. Addison's prose style was magisterial, placid, and with perfect balance of clauses. Steele's prose style was more direct than Addison's, and more worldly. The journal developed a number of pseudonymous characters, including "Mr. Spectator," Roger de Coverley

Roger de Coverley

Roger de Coverley is the name of an English country dance and a Scottish country dance . An early version was published in The Dancing Master, 9th edition . The Virginia Reel is probably related to it...

, and "Isaac Bickerstaff

Isaac Bickerstaff

Isaac Bickerstaff Esq was a pseudonym used by Jonathan Swift as part of a hoax to predict the death of then famous Almanac–maker and astrologer John Partridge....

" (a character Jonathan Swift would later borrow). Both authors developed fictions to surround their narrators. For example, Roger de Coverley came from Coverley Hall, had a family, liked hunting, and was a solid squire. The effect was something similar to a lighthearted serial

Serial (literature)

In literature, a serial is a publishing format by which a single large work, most often a work of narrative fiction, is presented in contiguous installments—also known as numbers, parts, or fascicles—either issued as separate publications or appearing in sequential issues of a single periodical...

novel, intermixed with meditations on follies and philosophical musings. The paper's politics were generally Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

, but never sharply or pedantically so, and thus a number of prominent Tories

Tory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

wrote "letters" to the paper (the letters were generally not actual letters but, instead, contributions from guest authors). The highly Latinate sentence structures and dispassionate view of the world (the pose of a spectator, rather than participant) was essential for the development of the English essay, as it set out a ground wherein Addison and Steele could comment and meditate upon manners and events, rather than campaign for specific policies or persons (as had been the case with previous, more political periodical literature) and without having to rely upon pure entertainment (as in the question and answer format found in The Athenian Mercury). Further, the pose of the Spectator allowed author and reader to meet as peers, rather than as philosopher and student (which was the case with Montesquieu).

One of the cultural innovations of the late Restoration had been the coffee house and chocolate house, where patrons would gather to drink coffee or chocolate (which was a beverage like hot chocolate

Hot chocolate

Hot chocolate is a heated beverage typically consisting of shaved chocolate, melted chocolate or cocoa powder, heated milk or water, and sugar...

and was unsweetened). Each coffee shop in the City was associated with a particular type of patron. Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

merchants favored Lloyd's, for example, and founded Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's, also known as Lloyd's of London, is a British insurance and reinsurance market. It serves as a partially mutualised marketplace where multiple financial backers, underwriters, or members, whether individuals or corporations, come together to pool and spread risk...

there. However, Button's and Will's coffee shops attracted writers, and Addison and Steele became the center of their own Kit-Kat Club and exerted a powerful influence over which authors rose or fell in reputation. (This would be satirized by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

later, as Atticus acting as a petty tyrant to a "little senate" of sycophants.) Addison's essays, and to a lesser extent Steele's, helped set the critical framework for the time. Addison's essays on the imagination were highly influential as distillations and reformulations of aesthetic philosophy. Mr. Spectator would comment upon fashions, the vanity of women, the emptiness of conversation, and the folly of youth.

After the success of The Spectator, more political periodicals of comment appeared, including the vaguely Tory The Guardian

The Guardian

The Guardian, formerly known as The Manchester Guardian , is a British national daily newspaper in the Berliner format...

and The Observer

The Observer

The Observer is a British newspaper, published on Sundays. In the same place on the political spectrum as its daily sister paper The Guardian, which acquired it in 1993, it takes a liberal or social democratic line on most issues. It is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.-Origins:The first issue,...

(note that none of these periodicals continued to the present day without interruption). The Gentleman's Magazine

The Gentleman's Magazine

The Gentleman's Magazine was founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term "magazine" for a periodical...

and Gentleman's Quarterly both began soon after. Some of these journals featured news more than commentary, and others featured reviews of recent works of literature. Many periodicals came from the area of the Inns of Court

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. All such barristers must belong to one such association. They have supervisory and disciplinary functions over their members. The Inns also provide libraries, dining facilities and professional...

, which had been associated with a bohemian lifestyle since the 1670s. Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

's later The Rambler

The Rambler

The Rambler was a periodical by Samuel Johnson.-Description:The Rambler was published on Tuesdays and Saturdays from 1750 to 1752 and totals 208 articles. It was Johnson's most consistent and sustained work in the English language...

and The Idler

The Idler (1758-1760)

The Idler was a series of 103 essays, all but twelve of them by Samuel Johnson, published in the London weekly the Universal Chronicle between 1758 and 1760. It is likely that the Chronicle was published for the sole purpose of including The Idler, since it had produced only one issue before the...

would self-consciously recreate the pose of Mr. Spectator to give a platform for musings and philosophy, as well as literary criticism.

However, the political factions (historian Louis B. Namier reminds us that officially there were no political parties in England at this time, even though those living in London referred to them quite often) and coalitions of politicians very quickly realized the power of the press, and they began funding newspapers to spread rumors. The Tory ministry of Robert Harley

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer KG was a British politician and statesman of the late Stuart and early Georgian periods. He began his career as a Whig, before defecting to a new Tory Ministry. Between 1711 and 1714 he served as First Lord of the Treasury, effectively Queen...

(1710 - 1714) reportedly spent over 50,000 pounds sterling on creating and bribing the press. Politicians wrote papers, wrote into papers, and supported papers, and it was well known that some of the periodicals, like Mist's Journal, were party mouthpieces.

Philosophy and religious writing

In contrast to the Restoration period, the Augustan period showed less literature of controversy. Compared to the extraordinary energy that produced Richard Baxter, George FoxGeorge Fox

George Fox was an English Dissenter and a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends.The son of a Leicestershire weaver, Fox lived in a time of great social upheaval and war...

, Gerrard Winstanley

Gerrard Winstanley

Gerrard Winstanley was an English Protestant religious reformer and political activist during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell...

, and William Penn

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

, the literature of dissenting religious in the first half of the 18th century was spent. One of the names usually associated with the novel is perhaps the most prominent in Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

writing: Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

. After the coronation of Anne, dissenter hopes of reversing the Restoration were at an ebb. Further, the Act of Settlement 1701

Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an act of the Parliament of England that was passed in 1701 to settle the succession to the English throne on the Electress Sophia of Hanover and her Protestant heirs. The act was later extended to Scotland, as a result of the Treaty of Union , enacted in the Acts of Union...

had removed one of their prime rallying points, for it was now somewhat sure that England would not become Roman Catholic. Therefore, dissenter literature moved from the offensive to the defensive, from revolutionary to conservative. Thus, Defoe's infamous volley in the struggle between high and low church came in the form of The Shortest Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church. The work is satirical, attacking all of the worries of Establishment figures over the challenges of dissenters. It is, therefore, an attack upon attackers and differs subtly from the literature of dissent found fifteen years earlier. For his efforts, Defoe was put in the pillory

Pillory

The pillory was a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse, sometimes lethal...

. He would continue his Puritan campaigning in his journalism and novels, but never again with public satire of this sort.

Instead of wild battles of religious controversy, the early 18th century was a time of emergent, de facto latitudinarian

Latitudinarian

Latitudinarian was initially a pejorative term applied to a group of 17th-century English theologians who believed in conforming to official Church of England practices but who felt that matters of doctrine, liturgical practice, and ecclesiastical organization were of relatively little importance...

ism. The Hanoverian kings distanced themselves from church politics and polity and themselves favored low church positions. Anne took few clear positions on church matters. The most majestic work of the era, and the one most quoted and read, was William Law

William Law

William Law was an English cleric, divine and theological writer.-Early life:Law was born at Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire in 1686. In 1705 he entered as a sizar at Emmanuel College, Cambridge; in 1711 he was elected fellow of his college and was ordained...

's A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728) (see his online works, below). Although Law was a non-juror

Non-juror

A non-juror is a person who refuses to swear a particular oath.* In British history, non-jurors refused to swear allegiance to William and Mary; see Nonjuring schism...

, his book was orthodox to all Protestants in England at the time and moved its readers to contemplate and practice their Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

more devoutly. The Meditations of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

remained popular as well. Both of these works called for revivalism, and they set the stage for the later development of Methodism

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

and George Whitefield

George Whitefield

George Whitefield , also known as George Whitfield, was an English Anglican priest who helped spread the Great Awakening in Britain, and especially in the British North American colonies. He was one of the founders of Methodism and of the evangelical movement generally...

's sermon style. They were works for the individual, rather than for the community. They were non-public and concentrated on the priesthood of all believers

Priesthood of all believers

The universal priesthood or the priesthood of all believers, as it would come to be known in the present day, is a Christian doctrine believed to be derived from several passages of the New Testament...

notion of an individual revelation.

Also in contrast to the Restoration, when philosophy in England was so fully dominated by John Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

that few other voices are remembered today, the 18th century had a vigorous competition among followers of Locke, and philosophical writing was strong. Bishop George Berkeley

George Berkeley

George Berkeley , also known as Bishop Berkeley , was an Irish philosopher whose primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immaterialism"...

and David Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

are the best remembered major philosophers of 18th-century England, but other philosophers adapted the political ramifications of empiricism

Empiricism

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism, idealism and historicism, empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence,...

, including Bernard de Mandeville

Bernard de Mandeville

Bernard Mandeville, or Bernard de Mandeville , was a philosopher, political economist and satirist. Born in the Netherlands, he lived most of his life in England and used English for most of his published works...

, Charles Davenant

Charles Davenant

Charles Davenant , English economist, eldest son of Sir William Davenant, the poet, was born in London.-Overview:He was educated at Cheam grammar school and Balliol College, Oxford, but left the university without taking a degree...

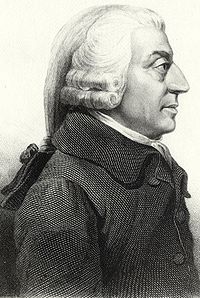

, and Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

. All of these figures can be considered empiricists, for they all begin with the relative certainty of perception, but they reach vastly different conclusions.

Bishop Berkeley extended Locke's emphasis on perception to argue that perception entirely solves the Cartesian problem of subjective and objective knowledge by saying "to be is to be perceived." Only, Berkeley argued, those things that are perceived by a consciousness are real. If there is no perception of a thing, then that thing cannot exist. Further, it is not the potential of perception that lends existence, but the actuality of perception. When Samuel Johnson flippantly kicked a rock and "thus...refute(d) Berkeley," his kick only affirmed Berkeley's position, for by perceiving the rock, Johnson had given it greater reality. However, Berkeley's empiricism was designed, at least partially, to lead to the question of who observes and perceives those things that are absent or undiscovered. For Berkeley, the persistence of matter rests in the fact that God

God

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

is perceiving those things that humans are not, that a living and continually aware, attentive, and involved God is the only rational explanation for the existence of objective matter. In essence, then, Berkeley's skepticism leads inevitably to faith.

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world, although the term is not easily defined. Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:...

in areas that other empiricists had assumed were material. Hume attacked the weakness of inductive logic and the apparently mystical assumptions behind key concepts such as energy

Energy

In physics, energy is an indirectly observed quantity. It is often understood as the ability a physical system has to do work on other physical systems...

and causality

Causality

Causality is the relationship between an event and a second event , where the second event is understood as a consequence of the first....

. (E.g. has anyone ever seen energy as energy? Are related events demonstrably causal instead of coincident?) Hume doggedly refused to enter into questions of his faith in the divine, but his assault on the logic and assumptions of theodicy

Theodicy

Theodicy is a theological and philosophical study which attempts to prove God's intrinsic or foundational nature of omnibenevolence , omniscience , and omnipotence . Theodicy is usually concerned with the God of the Abrahamic religions Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, due to the relevant...

and cosmogeny was devastating. He was an anti-apologist without ever agreeing to be atheist. Later philosophers have seen in Hume a basis for Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory holding that the proper course of action is the one that maximizes the overall "happiness", by whatever means necessary. It is thus a form of consequentialism, meaning that the moral worth of an action is determined only by its resulting outcome, and that one can...

and naturalism.

In social and political philosophy, economics underlies much of the debate. Charles Davenant, writing as a radical Whig, was the first to propose a theoretical argument on trade and virtue with his A Discourse on Grants and Resumptions and Essays on the Balance of Power (1701). However, Davenant's work was not directly very influential. On the other hand, Bernard de Mandeville's The Fable of the Bees became a centerpoint of controversy regarding trade, morality, and social ethics. It was initially a short poem called The Grumbling Hive, or Knaves Turn'd Honest in 1705. However, in 1714 he published it with its current title, The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits and included An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue. Mandeville argued that wastefulness, lust, pride, and all the other "private" vices (those applying to the person's mental state, rather than the person's public actions) were good for the society at large, for each led the individual to employ others, to spend freely, and to free capital to flow through the economy. William Law attacked the work, as did Bishop Berkeley (in the second dialogue of Alciphron in 1732). In 1729, when a new edition appeared, the book was prosecuted as a public nuisance. It was also denounced in the periodicals. John Brown attacked it in his Essay upon Shaftesbury's Characteristics (1751). It was reprinted again in 1755. Although there was a serious political and economic philosophy that derived from Mandeville's argument, it was initially written as a satire on the Duke of Marlborough's taking England to war for his personal enrichment. Mandeville's work is full of paradox and is meant, at least partially, to problematize what he saw as the naive philosophy of human progress and inherent virtue.

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, but his Theory of Moral Sentiments of 1759 attempted to strike out a new ground for moral action. His emphasis on "sentiment" was in keeping with the era, as he emphasized the need for "sympathy" between individuals as the basis of fit action. The idea, first rudimentally presented in Locke's Essay on Human Understanding, of a natural coherence between sensible beings being necessary for communication not only of words, but of emotions and states of being, was here brought out more fully. While Francis Hutcheson

Francis Hutcheson (philosopher)

Francis Hutcheson was a philosopher born in Ireland to a family of Scottish Presbyterians who became one of the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment....

had presupposed a separate sense in humans for morality (akin to conscience

Conscience

Conscience is an aptitude, faculty, intuition or judgment of the intellect that distinguishes right from wrong. Moral judgement may derive from values or norms...

but more primitive and more native), Smith argued that moral sentiment is communicated, that it is spread by what might be better called empathy. These ideas had been satirized already by wits like Jonathan Swift (who insisted that readers of his A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. It is arguably his most difficult satire, and perhaps his most masterly...

would be incapable of understanding it unless, like him, they were poor, hungry, had just had wine, and were located in a specific garret), but they were, through Smith and David Hartley

David Hartley (philosopher)

David Hartley was an English philosopher and founder of the Associationist school of psychology. -Early life and education:...

, influential on the sentimental novel

Sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility...

and even the nascent Methodist movement. If sympathetic sentiment communicated morality, would it not be possible to induce morality by providing sympathetic circumstances?

Smith's greatest work was An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776. What it held in common with de Mandeville, Hume, and Locke was that it began by analytically examining the history of material exchange, without reflection on morality. Instead of deducing from the ideal to the real, it examined the real and tried to formulate inductive rules. However, unlike Charles Davenant and the other radical Whig authors (including Daniel Defoe), it also did not begin with a desired outcome and work backward to deduce policy. Smith instead worked from a strictly empiricist basis to create the conceptual framework for an analytical economics.

The novel

As has been indicated above, the ground for the novel had been laid by journalism. It had also been laid by drama and by satire. Long prose satires like Swift's Gulliver's TravelsGulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

(1726) had a central character who goes through adventures and may (or may not) learn lessons. In fact, satires and philosophical works like Thomas More

Thomas More

Sir Thomas More , also known by Catholics as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, social philosopher, author, statesman and noted Renaissance humanist. He was an important councillor to Henry VIII of England and, for three years toward the end of his life, Lord Chancellor...

's Utopia

Utopia (book)

Utopia is a work of fiction by Thomas More published in 1516...

(1516), Rabelais's Gargantua and Pantagruel

Gargantua and Pantagruel

The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel is a connected series of five novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais. It is the story of two giants, a father and his son and their adventures, written in an amusing, extravagant, satirical vein...

(1532–64), and even Erasmus's In Praise of Folly (1511) had established long fictions subservient to a philosophical purpose. However, the most important single satirical source for the writing of novels came from Cervantes

Cervantes

-People:*Alfonso J. Cervantes , mayor of St. Louis, Missouri*Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, 16th-century man of letters*Ignacio Cervantes, Cuban composer*Jorge Cervantes, a world-renowned expert on indoor, outdoor, and greenhouse cannabis cultivation...

's Don Quixote (1605, 1615), which had been quickly translated from Spanish into other European languages including English. It would never go out of print, and the Augustan age saw many free translations in varying styles, by journalists (Ned Ward

Ned Ward

Ned Ward , also known as Edward Ward, was a satirical writer and publican in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century based in London, England. His most famous work is The London Spy. Published in 18 monthly instalments starting in November 1698 it was described as a "complete survey" of...

, 1700 and Peter Motteux, 1712) as well as novelists (Tobias Smollett

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

, 1755). In general, one can see these three axes, drama, journalism, and satire, as blending in and giving rise to three different types of novel.

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn was a prolific dramatist of the English Restoration and was one of the first English professional female writers. Her writing contributed to the amatory fiction genre of British literature.-Early life:...

had written literary novels before the turn of the 18th century, but there were not many immediate successors. Behn's Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684) had been bred in satire, and her Oroonoko

Oroonoko

Oroonoko is a short work of prose fiction by Aphra Behn , published in 1688, concerning the love of its hero, an enslaved African in Surinam in the 1660s, and the author's own experiences in the new South American colony....

(1688) had come from her theatrical experience. Mary Delarivier Manley's New Atlantis (1709) comes closest to an inheritor of Behn's, but her novel, while political and satirical, was a minor scandal. On the other hand, Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

's Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe is a novel by Daniel Defoe that was first published in 1719. Epistolary, confessional, and didactic in form, the book is a fictional autobiography of the title character—a castaway who spends 28 years on a remote tropical island near Trinidad, encountering cannibals, captives, and...

(1719) was the first major novel of the new century. Defoe had written political and religious polemics prior to Robinson Crusoe, and he worked as a journalist during and after its composition. Thus, Defoe encountered the memoirs of Alexander Selkirk

Alexander Selkirk

Alexander Selkirk was a Scottish sailor who spent four years as a castaway when he was marooned on an uninhabited island. It is probable that his travels provided the inspiration for Daniel Defoe's novel Robinson Crusoe....

, who was a rather brutish individual who had been stranded in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

on an island for some years. Defoe took the actual life and, from that, generated a fictional life. Instead of an expelled Scotsman, Crusoe became a devout Puritan. Instead of remaining alone the entire time, Crusoe encountered a savage named Friday, whom he civilized. The actual Selkirk had been a slave trader, and Crusoe becomes a far more enlightened teacher and missionary. Travel writing sold very well during the period, and tales of extraordinary adventures with pirates and savages were devoured by the public, and Defoe satisfied an essentially journalistic market with his fiction.

Jack Sheppard

Jack Sheppard was a notorious English robber, burglar and thief of early 18th-century London. Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter but took to theft and burglary in 1723, with little more than a year of his training to complete...

and Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them...

and wrote True Accounts of the former's escapes (and fate) and the latter's life. Defoe, unlike his competition, seems to have been a scrupulous journalist. Although his fictions contained great imagination and a masterful shaping of facts to build themes, his journalism seems based on actual investigation. From his reportage on the prostitutes and criminals, Defoe may have become familiar with the real-life Mary Mollineaux, who may have been the model for Moll in Moll Flanders (1722). As with the transformation of a real Selkirk into a fictional Crusoe, the fictional Moll is everything that the real prostitute was not. She pursues a wild career of material gain, travels to Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

, commits incest

Incest

Incest is sexual intercourse between close relatives that is usually illegal in the jurisdiction where it takes place and/or is conventionally considered a taboo. The term may apply to sexual activities between: individuals of close "blood relationship"; members of the same household; step...

, returns to England, and repents of her sins. She returns to the new land of promise for all Puritans of Maryland, where she lives honestly, with a great sum of money (derived from her licentious life). In the same year, Defoe produced a flatly journalistic A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), and an attempted tale of a working class male rise in Colonel Jack (1722). His last novel returned to the theme of fallen women in Roxana (1724). Thematically, Defoe's works are consistently Puritan. They all involve a fall, a degradation of the spirit, a conversion, and an ecstatic elevation. This religious structure necessarily involved a bildungsroman

Bildungsroman

In literary criticism, bildungsroman or coming-of-age story is a literary genre which focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from youth to adulthood , and in which character change is thus extremely important...

, for each character had to learn a lesson about him or herself and emerge the wiser.

Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson was an 18th-century English writer and printer. He is best known for his three epistolary novels: Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded , Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady and The History of Sir Charles Grandison...

's Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740) is the next landmark development in the English novel. Richardson was, like Defoe, a dissenter. Unlike Defoe, however, his profession was as a printer rather than a journalist. Therefore, his generic models were quite distinct from those of Defoe. Instead of working from the journalistic biography

Biography

A biography is a detailed description or account of someone's life. More than a list of basic facts , biography also portrays the subject's experience of those events...

, Richardson had in mind the dramatic cautionary tales of abused women and the books of improvement that were popular at the time. Pamela is an epistolary novel, like Behn's Love Letters, but its purpose is to illustrate a single chapter in the life of a poor country girl. Pamela Andrews enters the employ of a "Mr. B." As a dutiful girl, she writes to her mother constantly, and as a Christian girl, she is always on guard for her "virtue" (i.e. her virginity), for Mr. B lusts after her. The plot is somewhat melodramatic, and it is pathetic: the reader's sympathies and fears are engaged throughout, and the novel comes close to the She-tragedy

She-tragedy

The term she-tragedy refers to a vogue in the late 17th and early 18th centuries for tragic plays focused on the sufferings of an innocent and virtuous woman...

of the close of the 17th century in its depiction of a woman as a victim. However, Pamela triumphs. She acts as an angel for the reformation of Mr. B, and the novel ends with her marriage to her employer and rising to the position of lady

Lady

The word lady is a polite term for a woman, specifically the female equivalent to, or spouse of, a lord or gentleman, and in many contexts a term for any adult woman...

.

Pamela, like its author, presents a dissenter's and a Whig's view of the rise of the classes. It emphasizes duty and perseverance of the saint, and the work was an enormous popular success. It also drew a nearly instantaneous set of satires. Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

's response was to link Richardson's virtuous girl with Colley Cibber

Colley Cibber

Colley Cibber was an English actor-manager, playwright and Poet Laureate. His colourful memoir Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber describes his life in a personal, anecdotal and even rambling style...

's shamefaced Apology in the form of Shamela, or an Apology for the Life of Miss Shamela Andrews

An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews

An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews, or Shamela, as it is more commonly known, is a satirical novel written by Henry Fielding and first published in April 1741 under the name of Mr. Conny Keyber. Fielding never owned to writing the work, but it is widely considered to be his...

(1742) and it is the most memorable of the "answers" to Richardson. First, it inaugurated the rivalry between the two authors. Second, beneath the very loose and ribald satire, there is a coherent and rational critique of Richardson's themes. In Fielding's satire, Pamela, as Shamela, writes like a country peasant instead of a learned Londoner (as Pamela had), and it is her goal from the moment she arrives in Squire Booby's (as Mr. B is called) house to become lady of the place by selling her "vartue." Fielding also satirizes the presumption that a woman could write of dramatic, ongoing events ("He comes abed now, Mama. O Lud, my vartu! My vartu!"). Specifically, Fielding thought that Richardson's novel was very good, very well written, and very dangerous, for it offered serving women the illusion that they might sleep their way to wealth and an elevated title. In truth, Fielding saw serving women abused and lords renegging on both their spiritual conversions and promises.

After the coarse satire of Shamela, Fielding continued to bait Richardson with Joseph Andrews

Joseph Andrews

Joseph Andrews, or The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams, was the first published full-length novel of the English author and magistrate Henry Fielding, and indeed among the first novels in the English language...

. Shamela had appeared anonymously, but Fielding published Joseph Andrews under his own name, also in 1742. Joseph Andrews is the tale of Shamela's brother, Joseph, who goes through his life trying to protect his own virginity. Women, rather than men, are the sexual aggressors, and Joseph seeks only to find his place and his true love, Fanny, and accompany his childhood friend, Parson Adams, who is travelling to London to sell a collection of sermons to a bookseller in order to feed his large family. Since the term "fanny" had obscene implications in the 18th century, Joseph's longings for "my Fanny" survive as satirical blows, and the inversion of sexual predation strips bare the essentials of Richardson's valuation of virginity. However, Joseph Andrews is not a parody of Richardson. In that novel, Fielding proposed for the first time his belief in "good nature." Parson Adams, although not a fool, is a naif. His own basic good nature blinds him to the wickedness of the world, and the incidents on the road (for most of the novel is a travel story) allow Fielding to satirize conditions for the clergy, rural poverty (and squires), and the viciousness of businessmen. Fielding's novels arise out of a satirical model, and the same year that he wrote Joseph Andrews, he also wrote a work that parodied Daniel Defoe's criminal biographies: The History of Jonathan Wild the Great. Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them...

was published in Fielding's Miscellanies, and it is a thorough-going assault on the Whig party. It pretends to tell of the greatness of Jonathan Wild, but Wild is a stand-in for Robert Walpole, who was known as "the Great Man."

In 1747 through 1748, Samuel Richardson published Clarissa

Clarissa

Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady is an epistolary novel by Samuel Richardson, published in 1748. It tells the tragic story of a heroine whose quest for virtue is continually thwarted by her family, and is the longest real novelA completed work that has been released by a publisher in...

in serial form. Like Pamela, it is an epistolary novel. Unlike Pamela, it is not a tale of virtue rewarded. Instead, it is a highly tragic and affecting account of a young girl whose parents try to force her into an uncongenial marriage, thus pushing her into the arms of a scheming rake

Rake (character)

A rake, short for rakehell, is a historic term applied to a man who is habituated to immoral conduct, frequently a heartless womanizer. Often a rake was a man who wasted his fortune on gambling, wine, women and song, incurring lavish debts in the process...

named Lovelace. Lovelace is far more wicked than Mr. B. He imprisons Clarissa and tortures her psychologically in an effort to get her consent to marriage. Eventually, Clarissa is violated (whether by Lovelace or the household maids is unclear). Her letters to her parents are pleading, while Lovelace is sophisticated and manipulative. Most of Clarissa's letters are to her childhood friend, Anna Howe. Lovelace is not consciously evil, for he will not simply rape Clarissa. He desires her free consent, which Clarissa will not give. In the end, Clarissa dies by her own will. The novel is a masterpiece of psychological realism and emotional effect, and, when Richardson was drawing to a close in the serial publication, even Henry Fielding wrote to him, begging him not to kill Clarissa. There are many themes in play in Clarissa. Most obviously, the novel is a strong argument for romantic love

Romantic love

Romance is the pleasurable feeling of excitement and mystery associated with love.In the context of romantic love relationships, romance usually implies an expression of one's love, or one's deep emotional desires to connect with another person....

and against arranged marriages. Clarissa will marry, but she wishes to have her own say in choice of mate. As with Pamela, Richardson emphasizes the individual over the social and the personal over the class. His work was part of a general valuation of the individual over and against the social good.

Even as Fielding was reading and enjoying Clarissa, he was also writing a counter to its messages. His Tom Jones

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, often known simply as Tom Jones, is a comic novel by the English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding. First published on 28 February 1749, Tom Jones is among the earliest English prose works describable as a novel...

of 1749 offers up the other side of the argument from Clarissa. Tom Jones agrees substantially in the power of the individual to be more or less than his or her class, but it again emphasizes the place of the individual in society and the social ramifications of individual choices. While Clarissa cloisters its characters geographically to a house imprisonment and isolates them to their own subjective impressions in the form of letters, Fielding's Tom Jones employs a third person narrative and features a narrator who is virtually another character in the novel itself. Fielding constantly disrupts the illusionary identification of the reader with the characters by referring to the prose itself and uses his narrative style to posit antitheses of characters and action. Tom is a bastard and a foundling who is cared for by Squire Allworthy, who is a man of great good nature. This squire is benevolent and salutary to his community and his family. Allworthy's sister has a child who is born to a high position but who has a vicious nature. Allworthy, in accordance with Christian principles, treats the boys alike. Tom falls in love with Sophia, the daughter of a neighboring squire, and then has to win her hand. It is society that interferes with Tom, and not personified evil. Fielding answers Richardson by featuring a similar plot device (whether a girl can choose her own mate) but by showing how family and village can complicate and expedite matches and felicity.

Henry Fielding's sister, Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding was a British author and sister of the novelist Henry Fielding. She was the author of The Governess, or The Little Female Academy , which was the first novel in English written especially for children , and had earlier achieved success with her novel The Adventures of David Simple...

, was also a novelist. Her David Simple (1744) outsold Joseph Andrews and was popular enough to require sequels. Like her brother, Sarah propounds a theory of good nature. David Simple is, as his name suggests, an innocent. He is possessed of a benevolent disposition and a desire to please, and the pressures and contradictory impulses of society complicate the plot. On the one hand, this novel emphasizes the role of society, but, on the other, it is a novel that sets up the sentimental novel

Sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility...

. The genuine compassion and desire for goodness of David Simple were affecting for contemporary audiences, David Simple is a forerunner of the heroes of later novels such as Henry Mackenzie

Henry Mackenzie

Henry Mackenzie was a Scottish novelist and miscellaneous writer. He was also known by the sobriquet "Addison of the North."-Biography:Mackenzie was born in Edinburgh....

's The Man of Feeling

The Man of Feeling

The Man of Feeling is a sentimental novel published in 1771, written by Scottish author Henry Mackenzie. The novel presents a series of moral vignettes which the naïve protagonist Harley either observes, is told about, or participates in...

(1771).

Two other novelists should be mentioned, for they, like Fielding and Richardson, were in dialog through their works. Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne was an Irish novelist and an Anglican clergyman. He is best known for his novels The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy; but he also published many sermons, wrote memoirs, and was involved in local politics...

and Tobias Smollett

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

held a personal dislike for one another, and their works similarly offered up oppositional views of the self in society and the method of the novel. Laurence Sterne was a clergyman, and he consciously set out to imitate Jonathan Swift with his Tristram Shandy (1759–1767). The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman was a stylistic and formal revolution for the novel. Like Swift's satires, it begins with radical skepticism and a willingness to break apart figurative language and commonplace assumptions. The novel in three books is virtually all narrative voice, with a few interpolated narratives, such as "Slawkenbergius's Tale." Tristram seeks to write his autobiography

Autobiography

An autobiography is a book about the life of a person, written by that person.-Origin of the term:...

, but like Swift's narrator in A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. It is arguably his most difficult satire, and perhaps his most masterly...

, he worries that nothing in his life can be understood without understanding its context. For example, he tells the reader that at the very moment he was conceived, his mother was saying, "Did you wind the clock?" To explain how he knows this, he explains that his father took care of winding the clock and "other family business" on one day a month. To explain why the clock had to be wound then, he has to explain his father. To explain his father, he must explain a habit of his uncle's (referred to as "My Uncle Toby"), and that requires knowing what his uncle did during the War of the Spanish Succession

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was fought among several European powers, including a divided Spain, over the possible unification of the Kingdoms of Spain and France under one Bourbon monarch. As France and Spain were among the most powerful states of Europe, such a unification would have...

at the Battle of Namur. In other words, the biography moves backward rather than forward in time, only to then jump forward years, hit another knot, and move backward again. Further, Sterne provides "plot diagrams" for his readers that look like a ball of yarn. When a character dies, the next page of the book is black, in mourning. At one point, there is an end paper inserted into the text as a false ending to the book. It is a novel of exceptional energy, of multi-layered digression

Digression

Digression is a section of a composition or speech that is an intentional change of subject. In Classical rhetoric since Corax of Syracuse, especially in Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian, the digression was a regular part of any oration or composition...

s, of multiple satires, and of frequent parodies. It was so experimental that Samuel Johnson later famously used it as an example of a fad when he said that nothing novel can sustain itself, for "Tristram Shandy did not last."

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

, on the other hand, wrote more seemingly traditional novels (although the novel was still too new to have much of a tradition). He concentrated on the picaresque novel, where a low-born character would go through a practically endless series of adventures that would carry him into various cities and circles of high life and achieve either a great gain (in a comic ending) or a great loss. Unlike Sterne, who only published two novels, or Fielding, who died before he could manage more than four novels, Smollett was prolific. He wrote the following and more: The Adventures of Roderick Random

The Adventures of Roderick Random

The Adventures of Roderick Random is a picaresque novel by Tobias Smollett, first published in 1748. It is partially based on Smollett's experience as a naval-surgeon’s mate in the British Navy, especially during Battle of Cartagena de Indias in 1741...

(1748), The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751), The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom

The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom

The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom is a novel by Tobias Smollett first published in 1753. It was Smollett's third novel and met with less success than his two previous more picaresque tales. The central character is a villainous dandy who cheats, swindles and philanders his way across...

(1753), The Life and Adventures of Sir Launcelot Greaves

The Life and Adventures of Sir Launcelot Greaves

The Life and Adventures of Sir Launcelot Greaves, a novel by Tobias Smollett, was published in 1760 in the monthly paper The British Magazine...

(1762), The History and Adventures of an Atom

The History and Adventures of an Atom

The History and Adventures of an Atom, by Tobias Smollett, is a novel that savagely satirises English politics during the Seven Years' War....

(1769), and The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771). Smollett depended upon his pen for his livelihood, and so he also wrote history and political tracts. Smollett was also a highly valued translator. He translated both Don Quixote and Alain Rene LeSage

Alain-René Lesage

Alain-René Lesage was a French novelist and playwright. Lesage is best known for his comic novel The Devil upon Two Sticks , his comedy Turcaret , and his picaresque novel Gil Blas .-Youth and education:Claude Lesage, the father of the novelist, held the united...

's Gil Blas

Gil Blas

Gil Blas is a picaresque novel by Alain-René Lesage published between 1715 and 1735. It is considered to be the last masterpiece of the picaresque genre.-Plot summary:...

(1748). These two translated works show to some degree Smollett's personal preferences and models, for they are both rambling, open-ended novels with highly complex plots and comedy both witty and earthy. Sterne's primary attack on Smollett was personal, for the two men did not like each other, but he referred to Smollett as "Smelfungus

Smelfungus

Smelfungus is a name given by Laurence Sterne to Tobias Smollett as author of a volume of Travels through France and Italy, for the snarling abuse he heaps on the institutions and customs of the countries he visited....

." He thought that Smollett's novels always paid undue attention to the basest and most common elements of life, that they emphasized the dirt. Although this is a superficial complaint, it points to an important difference between the two as authors. Sterne came to the novel from a satirical background, while Smollett approached it from journalism. Sterne's pose is ironic, detached, and amused. For Sterne, the novel itself is secondary to the purpose of the novel, and that purpose was to pose difficult problems, on the one hand, and to elevate the reader, on the other (with his Sentimental Journey). Smollett's characters are desperately working to attain relief from imposition and pain, and they have little choice but to travel and strive. The plot of the novel drives the theme, and not the theme the plot. In the 19th century, novelists would have plots much nearer to Smollett's than either Fielding's or Sterne's or Richardson's, and his sprawling, linear development of action would prove most successful. However, Smollett's novels are not thematically tightly organized, and action appears solely for its ability to divert the reader, rather than to reinforce a philosophical point. The exception to this is Smollett's last novel, Humphry Clinker, written during Smollett's final illness. That novel adopts the epistolary framework previously seen in Richardson, but to document a long journey taken by a family. All of the family members and servants get a coach and travel for weeks, experiencing a number of complications and set-backs. The letters come from all of the members of the entourage, and not just the patriarch or matriarch. They exhibit numerous voices, from the witty and learned Oxford University student, Jerry (who is annoyed to accompany his family), to the eruptive patriarch Matthew Bramble, to the nearly illiterate servant Wynn Jenkins (whose writing contains many malapropisms). The title character doesn't appear until over half way through the novel, and he is only a coachman who turns out to be better than his station (and is revealed to be Matt Bramble's bastard son).

Later novels/other trends

In the midst of this development of the novel, other trends were taking place. The novel of sentiment was beginning in the 1760s and would experience a brief period of dominance. This type of novel emphasized sympathy. In keeping with the philosophy of Hartley (see above), the sentimental novel concentrated on characters who are quickly moved to labile swings of mood and extraordinary empathy.At the same time, women were writing novels and moving away from the old romance plots that had dominated before the Restoration. There were utopian novels, like Sarah Scott

Sarah Scott

Sarah Scott was an English novelist, translator, and social reformer. Her father, Matthew Robinson, and her mother, Elizabeth Robinson, were both from distinguished families, and Sarah was one of nine children who survived to adulthood...

's Millennium Hall (1762), autobiographical women's novels like Frances Burney's works, female adaptations of older, male motifs, such as Charlotte Lennox

Charlotte Lennox

Charlotte Lennox was an English author and poet. She is most famous now as the author of The Female Quixote and for her association with Samuel Johnson, Joshua Reynolds, and Samuel Richardson, but she had a long career and wrote poetry, prose, and drama.-Life:Charlotte Lennox was born in Gibraltar...

's The Female Quixote (1752) and many others. These novels do not generally follow a strict line of development or influence. However, they were popular works that were celebrated by both male and female readers and critics.

Historians of the novel

Ian WattIan Watt

Ian Watt was a literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University. His Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding is an important work in the history of the genre...

's The Rise of the Novel (1957) still dominates attempts at writing a history of the novel. Watt's view is that the critical feature of the 18th-century novel is the creation of psychological realism

Psychological novel

A psychological novel, also called psychological realism, is a work of prose fiction which places more than the usual amount of emphasis on interior characterization, and on the motives, circumstances, and internal action which springs from, and develops, external action...

. This feature, he argued, would continue on and influence the novel as it has been known in the 20th century, and therefore those novels that created it are, in fact, the true progenitors of the novel. Although Watt thought Tristram Shandy was the finest novel of the century, he also regarded it as being a stylistic cul-de-sac. Since Watt's work, numerous theorists and historians have attempted to answer the limitations of his assumptions.

Michael McKeon, for example, brought a Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

approach to the history of the novel in his 1986 The Origins of the English Novel. McKeon viewed the novel as emerging as a constant battleground between two developments of two sets of world view that corresponded to Whig/Tory, Dissenter/Establishment, and Capitalist/Persistent Feudalist. The "novel," for him, is the synthesis of competing and clashing theses and antitheses of individual novels. I.e. the "novel" is the process of negotiation and conflict between competing ideologies

Ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

, rather than a definable and fixed set of thematic or generic conventions.

Satire (unclassified)

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

. Swift wrote poetry as well as prose, and his satires range over all topics. Critically, Swift's satire marked the development of prose parody away from simple satire or burlesque. A burlesque or lampoon in prose would imitate a despised author and quickly move to reductio ad absurdum

Reductio ad absurdum

In logic, proof by contradiction is a form of proof that establishes the truth or validity of a proposition by showing that the proposition's being false would imply a contradiction...

by having the victim say things coarse or idiotic. On the other hand, other satires would argue against a habit, practice, or policy by making fun of its reach or composition or methods. What Swift did was to combine parody

Parody

A parody , in current usage, is an imitative work created to mock, comment on, or trivialise an original work, its subject, author, style, or some other target, by means of humorous, satiric or ironic imitation...

, with its imitation of form and style of another, and satire in prose. Swift's works would pretend to speak in the voice of an opponent and imitate the style of the opponent and have the parodic work itself be the satire: the imitation would have subtle betrayals of the argument but would not be obviously absurd. For example, in A Modest Proposal

A Modest Proposal

A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland From Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick, commonly referred to as A Modest Proposal, is a Juvenalian satirical essay written and published anonymously by Jonathan Swift in...

(1729), Swift imitates the "projector." As indicated above, the book shops were filled with single sheets and pamphlets proposing economic panacea. These projectors would slavishly write according to the rules of rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

that they had learned in school by stating the case, establishing that they have no interest in the outcome, and then offering a solution before enumerating the profits of the plan. Swift does the same, but the proposed solution (cannibalism

Cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh of other human beings. It is also called anthropophagy...

) is immoral. There is very little logically wrong with the proposal, but it is unquestionably morally abhorrent, and it can only be acceptable if one regards the Irish as kine. The parody of an enemy is note-perfect, and the satire comes not from grotesque exaggerations of style, but in the extra-literary realm of morality and ethics.

A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. It is arguably his most difficult satire, and perhaps his most masterly...

(1703 - 1705). That satire introduced an ancients/moderns division that would serve as a handy distinction between the old and new conception of value. The "moderns" sought trade, empirical science, the individual's reason above the society's, and the rapid dissemination of knowledge, while the "ancients" believed in inherent and immanent value of birth, the society over the individual's determinations of the good, and rigorous education. In Swift's satire, the moderns come out looking insane and proud of their insanity, dismissive of the value of history, and incapable of understanding figurative language because unschooled. In Swift's most significant satire, Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

(1726), autobiography, allegory, and philosophy mix together in the travels. Under the umbrella of a parody of travel writing (such as Defoe's, but more particularly the fantastic and oriental tales that were circulating in London), Swift's Gulliver travels to Liliput, a figurative London beset by a figurative Paris, and sees all of the factionalism and schism

Schism (religion)

A schism , from Greek σχίσμα, skhísma , is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization or movement religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a break of communion between two sections of Christianity that were previously a single body, or to a division within...

as trifles of small men. He travels then to an idealized nation with a philosopher king

Philosopher king

Philosopher kings are the rulers, or Guardians, of Plato's Utopian Kallipolis. If his ideal city-state is to ever come into being, "philosophers [must] become kings…or those now called kings [must]…genuinely and adequately philosophize" .-In Book VI of The Republic:Plato defined a philosopher...

in Brobdingnag, where Gulliver's own London is summed up in the king's saying, "I cannot but conclude the bulk of your natives to be the most pernicious race of odious little vermin Nature ever suffered to crawl upon the face of the earth." Gulliver then moves beyond the philosophical kingdom to the land of the Houyhnhnms, a society of horses ruled by pure reason, where humanity itself is portrayed as a group of "yahoos" covered in filth and dominated by base desires. Swift later added a new third book to the satire, a heterogeneous book of travels to Laputa

Laputa

Laputa is a fictional place from the book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift.Laputa is a fictional flying island or rock, about 4.5 miles in diameter, with an adamantine base, which its inhabitants can maneuver in any direction using magnetic levitation...

, Balnibarbi, Glubdubdribb, Luggnagg, and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. This book's primary satire is on empiricsim and the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, whose reports Swift read. "Projectors" of all sorts live in the Academy of Lagado, a flying island (London) that saps all the nourishment from the land below (the countryside) and occasionally crushes, literally, troublesome cities (Dublin). Thematically, Gulliver's Travels is a critique of human vanity, of pride. Book one begins with the world as it is. Book two shows that an ideal philosopher kingdom is no home for a contemporary Englishman. Book three shows the uselessness and actual evil of indulging the passions of science without connection to the realm of simple production and consumption. Book four shows that, indeed, the very desire for reason may be undesirable, and humans must struggle to be neither Yahoos nor Houhynymns.

There were other satirists who worked in a less virulent way. Jonathan Swift's satires obliterated hope in any specific institution or method of human improvement, but some satirists instead took a bemused pose and only made lighthearted fun. Tom Brown

Tom Brown (satirist)

Tom Brown was an English translator and writer of satire, largely forgotten today save for a four-line gibe he wrote concerning Dr John Fell....

, Ned Ward

Ned Ward

Ned Ward , also known as Edward Ward, was a satirical writer and publican in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century based in London, England. His most famous work is The London Spy. Published in 18 monthly instalments starting in November 1698 it was described as a "complete survey" of...

, and Tom D'Urfey were all satirists in prose whose works appeared in the early part of the Augustan age. Tom Brown's most famous work in this vein was Amusements Serious and Comical, Calculated for the Meridian of London (1700). For poetry, Brown was important for his translation of Scarron's Le Virgile travesti, as well as the scandalous Roman satirist Petronius

Petronius

Gaius Petronius Arbiter was a Roman courtier during the reign of Nero. He is generally believed to be the author of the Satyricon, a satirical novel believed to have been written during the Neronian age.-Life:...

(CBEL). Ned Ward's most memorable work was The London Spy (1704–1706). The London Spy, before The Spectator, took up the position of an observer and uncomprehendingly reporting back. Thereby, Ward records and satirizes the vanity and exaggerated spectacle of London life in a lively prose style. Ward is also important for his history of secret clubs of the Augustan age. These included The Secret History of the Calves-Head Club, Complt. or, The Republican Unmask'd (1706), which sought humorously to expose the silly exploits of radicals. Ward also translated The Life &Adventures of Don Quixote de la Mancha, translated into Hudibrastic Verse in 1711, where the Hudibrastic

Hudibrastic

Hudibrastic is a type of English verse named for Samuel Butler's Hudibras, published in parts from 1663 to 1678. For the poem, Butler invented a mock-heroic verse structure. Instead of pentameter, the lines were written in iambic tetrameter...