Timeline of LGBT history in Britain

Encyclopedia

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of the lesbian

, gay

, bisexual and transgender

community in the United Kingdom

.

1939-1945 World War II

Lesbian

Lesbian is a term most widely used in the English language to describe sexual and romantic desire between females. The word may be used as a noun, to refer to women who identify themselves or who are characterized by others as having the primary attribute of female homosexuality, or as an...

, gay

Gay

Gay is a word that refers to a homosexual person, especially a homosexual male. For homosexual women the specific term is "lesbian"....

, bisexual and transgender

Transgender

Transgender is a general term applied to a variety of individuals, behaviors, and groups involving tendencies to vary from culturally conventional gender roles....

community in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

.

16th century

- 1533 In England and Wales Buggery was made a felonyFelonyA felony is a serious crime in the common law countries. The term originates from English common law where felonies were originally crimes which involved the confiscation of a convicted person's land and goods; other crimes were called misdemeanors...

by the Buggery Act in 1533, during the reign of Henry VIII. The punishment for those convicted was the death penalty. The lesser offence of "attempted buggery" was punished by 2 years of jail and often horrific time on the pilloryPilloryThe pillory was a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse, sometimes lethal...

.

18th century

- 1726 Three men (Gabriel Lawrence, William Griffin, and Thomas Wright) were hanged at TyburnTyburnTyburn is a former village just outside the then boundaries of London that was best known as a place of public execution.Tyburn may also refer to:* Tyburn , river and historical water source in London...

for sodomySodomySodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

following a raid of Margaret ClapMargaret ClapMargaret Clap , better known as Mother Clap, ran a coffee house from 1724 to 1726 in Holborn, London. Notable for running a molly house, an inn or tavern primarily frequented by homosexual men, she was also heavily involved in the ensuing legal battles after her premise was raided and shut down...

's Molly houseMolly houseA Molly house is an archaic 18th century English term for a tavern or private room where homosexual and cross-dressing men could meet each other and possible sexual partners. Molly houses were one precursor to some types of gay bars....

.

- 1727 Charles HitchenCharles HitchenCharles Hitchen was a "thief-taker" in 18th century London who was also famously tried for homosexuality....

, a London “Under City Marshal”, was convicted of attempted sodomySodomySodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

at a Molly houseMolly houseA Molly house is an archaic 18th century English term for a tavern or private room where homosexual and cross-dressing men could meet each other and possible sexual partners. Molly houses were one precursor to some types of gay bars....

. Hitchen had frequently picked up soldiers for sex, but had eluded prosecution by the Society for the Reformation of MannersSociety for the Reformation of MannersThe Society for the Reformation of Manners was founded in the Tower Hamlets area of London in 1691. Its espoused aims were the suppression of profanity, immorality, and other lewd activities in general, and of brothels and prostitution in particular....

.

- 1785 Jeremy BenthamJeremy BenthamJeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

becomes one of the first people to argue for the decriminalisation of sodomy in England.

19th century

- 1835 The last two men hanged in Britain under the 1533 Buggery Act, James Pratt and John Smith, were arrested at a house in SouthwarkSouthwarkSouthwark is a district of south London, England, and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Southwark. Situated east of Charing Cross, it forms one of the oldest parts of London and fronts the River Thames to the north...

after being observed having sex.

- 1861 The Buggery Act was changed from a capital crimeCapital punishmentCapital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

and with it the death penalty for buggeryBuggeryThe British English term buggery is very close in meaning to the term sodomy, and is often used interchangeably in law and popular speech. It may be, also, a specific common law offence, encompassing both sodomy and bestiality.-In law:...

was finally abolished. A total of 8921 men had been prosecuted since 1806 for sodomySodomySodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

with 404 sentenced to death and 56 executed.

- 1881 A scandal occurred when Corporal John Cameron of the Scots GuardsScots GuardsThe Scots Guards is a regiment of the Guards Division of the British Army, whose origins lie in the personal bodyguard of King Charles I of England and Scotland...

was accused of committing an “atrocious offence” in a coffee house in Sloane StreetSloane StreetSloane Street is a major London street which runs north to south, from Knightsbridge to Sloane Square, crossing Pont Street about half way along, entirely in The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Sloane Street takes its name from Sir Hans Sloane, who purchased the surrounding area in 1712...

with Count Guido zu Lynar, a secretary at the GermanGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

embassy.

- 1885 The British Parliament enacted section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 , or "An Act to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes", was the latest in a 25-year series of legislation in the United Kingdom beginning with the Offences against the Person Act 1861 that...

, known as the Labouchere AmendmentLabouchere AmendmentThe Labouchere Amendment, also known as Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 made gross indecency a crime in the United Kingdom. The amendment gave no definition of "gross indecency," as Victorian morality demurred from precise descriptions of activity held to be immoral...

which prohibited gross indecencyGross indecencyGross indecency is a UK and Canadian legal term of art which was used in the definition of the following criminal offences:*Gross indecency between men, contrary to section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 and later contrary to section 13 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956.*Indecency with a...

between males. It thus became possible to prosecute homosexuals for engaging is sexual acts where buggeryBuggeryThe British English term buggery is very close in meaning to the term sodomy, and is often used interchangeably in law and popular speech. It may be, also, a specific common law offence, encompassing both sodomy and bestiality.-In law:...

or attempted buggery could not be proven.

- 1889 The Cleveland Street scandalCleveland Street scandalThe Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel in Cleveland Street, Fitzrovia, London, was discovered by police. At the time, sexual acts between men were illegal in Britain, and the brothel's clients faced possible prosecution and certain social ostracism if discovered...

occurred, when a homosexual male brothelBrothelBrothels are business establishments where patrons can engage in sexual activities with prostitutes. Brothels are known under a variety of names, including bordello, cathouse, knocking shop, whorehouse, strumpet house, sporting house, house of ill repute, house of prostitution, and bawdy house...

in Cleveland Street, FitzroviaFitzroviaFitzrovia is a neighbourhood in central London, near London's West End lying partly in the London Borough of Camden and partly in the City of Westminster ; and situated between Marylebone and Bloomsbury and north of Soho. It is characterised by its mixed-use of residential, business, retail,...

, LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, was raided by police after they discovered telegraph boyTelegraph boyTelegraph boys were uniformed young men between 10 and 18 years of age who, mounted on bicycles, carried telegrams through urban streets...

s had been working there as rent boys. A number of aristocratic clients were discovered including Lord Arthur Somerset equerryEquerryAn equerry , and related to the French word "écuyer" ) is an officer of honour. Historically, it was a senior attendant with responsibilities for the horses of a person of rank. In contemporary use, it is a personal attendant, usually upon a Sovereign, a member of a Royal Family, or a national...

to the Prince of WalesEdward VII of the United KingdomEdward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

. The Prince of WalesEdward VII of the United KingdomEdward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

’s son Prince Albert Victor and Lord Euston were also implicated in the scandal.

- 1895 Oscar WildeOscar WildeOscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

tried for gross indecency over a relationship with Lord Alfred DouglasLord Alfred DouglasLord Alfred Bruce Douglas , nicknamed Bosie, was a British author, poet and translator, better known as the intimate friend and lover of the writer Oscar Wilde...

, was sentenced to two years in prison with hard labour.

20th century

- 1910 London homosexuals gathered openly in public places such as pubs, coffee houses and tea shops. Waitresses ensured that a section of Lyons Corner House in Piccadilly CircusPiccadilly CircusPiccadilly Circus is a road junction and public space of London's West End in the City of Westminster, built in 1819 to connect Regent Street with the major shopping street of Piccadilly...

was reserved for homosexuals. The section became known as the Lily Pond.

- 1918 The gay English poet and writer W. H. AudenW. H. AudenWystan Hugh Auden , who published as W. H. Auden, was an Anglo-American poet,The first definition of "Anglo-American" in the OED is: "Of, belonging to, or involving both England and America." See also the definition "English in origin or birth, American by settlement or citizenship" in See also...

attended his first boarding school where he met Christopher IsherwoodChristopher IsherwoodChristopher William Bradshaw Isherwood was an English-American novelist.-Early life and work:Born at Wyberslegh Hall, High Lane, Cheshire in North West England, Isherwood spent his childhood in various towns where his father, a Lieutenant-Colonel in the British Army, was stationed...

; when reintroduced to Isherwood in 1925, Auden probably fell in love with Isherwood and in the 1930s they maintained a sexual friendship in intervals between their relations with others.

- 1921 The Criminal Law Amendment ActCriminal Law Amendment ActCriminal Law Amendment Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, Canada, India and South Africa which amends the criminal law...

, to make sexual acts between women illegal was passed in House of Commons. However it was defeated in the House Of LordsHouse of LordsThe House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

and thus never became law.

- 1928 The Well of LonelinessThe Well of LonelinessThe Well of Loneliness is a 1928 lesbian novel by the British author Radclyffe Hall. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose "sexual inversion" is apparent from an early age...

by Radclyffe HallRadclyffe HallRadclyffe Hall was an English poet and author, best known for the lesbian classic The Well of Loneliness.- Life :...

is published in the UK by Jonathan CapeJonathan CapeJonathan Cape was a London-based publisher founded in 1919 as "Page & Co" by Herbert Jonathan Cape , formerly a manager at Duckworth who had worked his way up from a position of bookshop errand boy. Cape brought with him the rights to cheap editions of the popular author Elinor Glyn and sales of...

. This sparks great legal controversy and brings the topic of homosexuality to public conversation. James Douglas, editor of the Sunday ExpressDaily ExpressThe Daily Express switched from broadsheet to tabloid in 1977 and was bought by the construction company Trafalgar House in the same year. Its publishing company, Beaverbrook Newspapers, was renamed Express Newspapers...

newspaper, began a campaign to suppress the book with poster and billboard advertising. Publisher Jonathan CapeJonathan CapeJonathan Cape was a London-based publisher founded in 1919 as "Page & Co" by Herbert Jonathan Cape , formerly a manager at Duckworth who had worked his way up from a position of bookshop errand boy. Cape brought with him the rights to cheap editions of the popular author Elinor Glyn and sales of...

panicked and sent a copy of The Well of LonelinessThe Well of LonelinessThe Well of Loneliness is a 1928 lesbian novel by the British author Radclyffe Hall. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose "sexual inversion" is apparent from an early age...

to the Home SecretaryHome SecretaryThe Secretary of State for the Home Department, commonly known as the Home Secretary, is the minister in charge of the Home Office of the United Kingdom, and one of the country's four Great Offices of State...

, William Joynson-Hicks (a ConservativeConservative Party (UK)The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

) for his opinion; he took only two days to reply that The Well of LonelinessThe Well of LonelinessThe Well of Loneliness is a 1928 lesbian novel by the British author Radclyffe Hall. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose "sexual inversion" is apparent from an early age...

was "gravely detrimental to the public interest" and if Cape did not withdraw it voluntarily, criminal proceedings would be brought against him. CapeJonathan CapeJonathan Cape was a London-based publisher founded in 1919 as "Page & Co" by Herbert Jonathan Cape , formerly a manager at Duckworth who had worked his way up from a position of bookshop errand boy. Cape brought with him the rights to cheap editions of the popular author Elinor Glyn and sales of...

suppressed the book after only two editions.

- 1929 The death of Edward CarpenterEdward CarpenterEdward Carpenter was an English socialist poet, socialist philosopher, anthologist, and early gay activist....

(29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929), an EnglishEnglish peopleThe English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

socialist poetPoetA poet is a person who writes poetry. A poet's work can be literal, meaning that his work is derived from a specific event, or metaphorical, meaning that his work can take on many meanings and forms. Poets have existed since antiquity, in nearly all languages, and have produced works that vary...

, socialist philosopher, anthologist, and early gay activist.

- 1932 Sir Noël CowardNoël CowardSir Noël Peirce Coward was an English playwright, composer, director, actor and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what Time magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and chic, pose and poise".Born in Teddington, a suburb of London, Coward attended a dance academy...

writes "Mad About the BoyMad About the BoyDinah Washington's 1952 recording of "Mad about the Boy" is possibly the most widely known version of the song in modern times. The 6/8-time arrangement for voice and jazz orchestra by Quincy Jones omits two verses and was recorded in the singer's native Chicago on the Mercury label.Washington's...

", a song which deals with the theme of homosexualHomosexualityHomosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

love. It was introduced in the 19321932 in music-Events:*January 14 – Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto is premièred in Paris.*May 1 – The music to John Alden Carpenter's ballet Skyscrapers is recorded by the Victor Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Nathaniel Shilkret; in addition to be being issued as six sides on 78 rpm discs, the...

revueRevueA revue is a type of multi-act popular theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance and sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century American popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural presence of its own during its golden years from 1916 to 1932...

, but due to the risque nature of the song, it was sung by a woman.

1939-1945 World War II

- 1952 Sir John Nott-BowerJohn Nott-BowerSir John Reginald Hornby Nott-Bower KCVO KPM OStJ was Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, the head of the London Metropolitan Police, from 1953 to 1958...

, commissioner of Scotland YardScotland YardScotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

began to weed out homosexuals from the British Government at the same time as McCarthyJoseph McCarthyJoseph Raymond "Joe" McCarthy was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957...

was conducting a federal homosexual witch hunt in the US.

- 1954 Alan TuringAlan TuringAlan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS , was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which played a...

, an English mathematicianMathematicianA mathematician is a person whose primary area of study is the field of mathematics. Mathematicians are concerned with quantity, structure, space, and change....

, logician, cryptanalyst and computer scientistComputer scientistA computer scientist is a scientist who has acquired knowledge of computer science, the study of the theoretical foundations of information and computation and their application in computer systems....

influential in the development of computer scienceComputer scienceComputer science or computing science is the study of the theoretical foundations of information and computation and of practical techniques for their implementation and application in computer systems...

committed suicide. He had been given a course of female hormones (chemical castrationChemical castrationChemical castration is the administration of medication designed to reduce libido and sexual activity, usually in the hope of preventing rapists, child molesters and other sex offenders from repeating their crimes...

) by doctors as an alternative to prison after being prosecuted by the police because of his homosexualityHomosexualityHomosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

.

- 1957 The Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (better known as the Wolfenden reportWolfenden reportThe Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution was published in Britain on 4 September 1957 after a succession of well-known men, including Lord Montagu, Michael Pitt-Rivers and Peter Wildeblood, were convicted of homosexual offences.-The committee:The...

, after Lord Wolfenden) was published. It advised the British Government that homosexuality should not be illegal.

- 1958 The Homosexual Law Reform SocietyHomosexual Law Reform SocietyThe Homosexual Law Reform Society was an organisation that campaigned in the United Kingdom for changes in the laws that criminalised homosexual relations between men.- History :...

is founded in the United Kingdom following the Wolfenden reportWolfenden reportThe Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution was published in Britain on 4 September 1957 after a succession of well-known men, including Lord Montagu, Michael Pitt-Rivers and Peter Wildeblood, were convicted of homosexual offences.-The committee:The...

the previous year, to begin a campaign to make homosexuality legal in the UK.

1960s

- 1967 The Sexual Offences ActSexual Offences ActSexual Offences Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom relating to sexual offences ....

decriminalised homosexual acts between two men over 21 years of age "in private" in EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and WalesWalesWales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

. This did not apply to ScotlandScotlandScotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, Northern IrelandNorthern IrelandNorthern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

nor the Channel IslandsChannel IslandsThe Channel Islands are an archipelago of British Crown Dependencies in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two separate bailiwicks: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey...

; The book Homosexual Behavior Among Males by Wainwright Churchill breaks ground as a scientific study approaching homosexuality as a fact of life and introduces the term "homoerotophobia", a possible precursor to "homophobia";

- 1969 Campaign for Homosexual EqualityCampaign for Homosexual EqualityThe Campaign for Homosexual Equality is one of the oldest gay rights organisations in the United Kingdom. It is a membership organisation which aims to promote legal and social equality for lesbians, gay men and bisexuals in England and Wales...

(CHE) formed as the first British gay activist group.

1970s

- 1970 Gay Liberation FrontGay Liberation FrontGay Liberation Front was the name of a number of Gay Liberation groups, the first of which was formed in New York City in 1969, immediately after the Stonewall riots, in which police clashed with gay demonstrators.-The Gay Liberation Front:...

(GLF) was established in response to debates many gay men and lesbians were having in the UK about the way they were treated. The formation of GLF also influenced by the Stonewall Rebellion in the USA that started on 28 June 1969.

- 1971 The Nationwide Festival of LightNationwide Festival of LightThe Nationwide Festival of Light was a grassroots movement formed by British Christians concerned about the development of the permissive society in the UK at the end of the 1960s....

supported by Cliff RichardCliff RichardSir Cliff Richard, OBE is a British pop singer, musician, performer, actor, and philanthropist who has sold over an estimated 250 million records worldwide....

, Mary WhitehouseMary WhitehouseMary Whitehouse, CBE was a British campaigner against the permissive society particularly as the media portrayed and reflected it...

, Malcolm MuggeridgeMalcolm MuggeridgeThomas Malcolm Muggeridge was an English journalist, author, media personality, and satirist. During World War II, he was a soldier and a spy...

and Lord Longford was held by British Christians who were concerned about the development of the permissive societyPermissive societyThe permissive society is a society where social norms are becoming increasingly liberal. This usually accompanies a change in what is considered deviant. While typically preserving the rule "do not harm others", a permissive society would have few other moral codes...

in the UK and in particular, homosexuality and out of wedlock sexual activity. The GLFGay Liberation FrontGay Liberation Front was the name of a number of Gay Liberation groups, the first of which was formed in New York City in 1969, immediately after the Stonewall riots, in which police clashed with gay demonstrators.-The Gay Liberation Front:...

interrupted the festival with a series of demonstrations.

- 1972 The First UK Gay Pride RallyPride LondonPride London is the name of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender registered charity which arranges LGBT events in London, most notably the annual gay pride parade which is held in June/July. The most recent Pride London was on 2 July 2011. The 2010 event was attended by 1 million people,...

was held in LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

with 1000 people marching from Trafalgar SquareTrafalgar SquareTrafalgar Square is a public space and tourist attraction in central London, England, United Kingdom. At its centre is Nelson's Column, which is guarded by four lion statues at its base. There are a number of statues and sculptures in the square, with one plinth displaying changing pieces of...

to Hyde ParkHyde Park, LondonHyde Park is one of the largest parks in central London, United Kingdom, and one of the Royal Parks of London, famous for its Speakers' Corner.The park is divided in two by the Serpentine...

.

- 1975 The groundbreaking film portraying homosexual gay icon Quentin CrispQuentin CrispQuentin Crisp , was an English writer and raconteur. He became a gay icon in the 1970s after publication of his memoir, The Naked Civil Servant.- Early life :...

's life, The Naked Civil ServantThe Naked Civil Servant (film)The Naked Civil Servant is a 1975 TV film based on the 1968 autobiography by the gay icon Quentin Crisp, also titled The Naked Civil Servant. It stars John Hurt in the title role....

(based on the 1968 autobiography and starring John HurtJohn HurtJohn Vincent Hurt, CBE is an English actor, known for his leading roles as John Merrick in The Elephant Man, Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Mr. Braddock in The Hit, Stephen Ward in Scandal, Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant and An Englishman in New York...

) was transmitted by Thames TelevisionThames TelevisionThames Television was a licensee of the British ITV television network, covering London and parts of the surrounding counties on weekdays from 30 July 1968 until 31 December 1992....

for the British Television channel ITVITVITV is the major commercial public service TV network in the United Kingdom. Launched in 1955 under the auspices of the Independent Television Authority to provide competition to the BBC, it is also the oldest commercial network in the UK...

.

- 1976 The UK's political pressure group LibertyLiberty (pressure group)Liberty is a pressure group based in the United Kingdom. Its formal name is the National Council for Civil Liberties . Founded in 1934 by Ronald Kidd and Sylvia Crowther-Smith , the group campaigns to protect civil liberties and promote human rights...

, under their alternate name National Council for Civil Liberties, (NCCL) called for an equal age of consent of 14 in Britain

- 1977 The first gay lesbian Trades Union CongressTrades Union CongressThe Trades Union Congress is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in the United Kingdom, representing the majority of trade unions...

(TUC) conference took place to discuss workplace rights for Gays and Lesbians.

1980s

- 1980 The Sexual Offences ActSexual Offences ActSexual Offences Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom relating to sexual offences ....

decriminalised homosexual acts between two men over 21 years of age "in private" in ScotlandScotlandScotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

.

- 1981 The European Court of Human RightsEuropean Court of Human RightsThe European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is a supra-national court established by the European Convention on Human Rights and hears complaints that a contracting state has violated the human rights enshrined in the Convention and its protocols. Complaints can be brought by individuals or...

in Dudgeon v. United KingdomDudgeon v. United KingdomDudgeon v the United Kingdom was a European Court of Human Rights case, which held that legislation passed in the nineteenth century to criminalise male homosexual acts in England, Wales and Ireland - in 1980, still in force in Northern Ireland - violated the European Convention on Human Rights...

strikes down Northern IrelandNorthern IrelandNorthern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

's criminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults. The first UK case of AIDSAIDSAcquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

was recorded when a 49-year-old man was admitted to Brompton Hospital in London suffering from PCP (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia). He died ten days later.

- 1982 The Sexual Offences ActSexual Offences ActSexual Offences Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom relating to sexual offences ....

decriminalised homosexual acts between two men over 21 years of age "in private" in Northern IrelandNorthern IrelandNorthern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

. Terry HigginsTerry HigginsTerrence Higgins, known as Terry Higgins, was among the first people known to die of an AIDS-related illness in England. He died on July 4, 1982. He worked as a Hansard reporter in the House of Commons and as a barman in the nightclub Heaven...

dies of AIDSAIDSAcquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

in St Thomas' HospitalSt Thomas' HospitalSt Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS hospital in London, England. It is administratively a part of Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. It has provided health care freely or under charitable auspices since the 12th century and was originally located in Southwark.St Thomas' Hospital is accessible...

London, his friends set up the Terry Higgins Trust (which became the Terrence Higgins TrustTerrence Higgins TrustTerrence Higgins Trust is a British charity that campaigns on various issues related to AIDS and HIV. In particular, the charity aims to reduce the spread of HIV and promote good sexual health ; to provide services on a national and local level to people with, affected by, or at risk of...

), the first UK AIDS charity.

- 1983 Britain reports 17 cases of AIDS Gay men are asked not to donate blood.

- 1984 Chris SmithChris Smith, Baron Smith of FinsburyChristopher "Chris" Robert Smith, Baron Smith of Finsbury PC is a British Labour Party politician, and a former Member of Parliament and Cabinet Minister...

, newly elected to the UK parliament declares: "My name is Chris Smith. I'm the Labour MP for Islington South and FinsburyIslington South and FinsburyIslington South and Finsbury is a parliamentary constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first-past-the-post system of election.- Boundaries :...

, and I'm gay", making him the first openly out homosexual politician in the UK parliament. Britain reports 108 cases of AIDSAIDSAcquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

with 46 deaths (from AIDSAIDSAcquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

).

- 1985 AIDSAIDSAcquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

hysteria grows in the UK when passengers on the Queen Elizabeth 2 curtailed their holiday as a person with AIDS was discovered on-board. CunardCunard LineCunard Line is a British-American owned shipping company based at Carnival House in Southampton, England and operated by Carnival UK. It has been a leading operator of passenger ships on the North Atlantic for over a century...

were criticised for trying to cover this up. A London support group Body Positive was set up as a self-help group for people affected by HTLV-3Human T-lymphotropic virusHuman T-cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 , also called the Adult T-cell lymphoma virus type 1, a virus that has been seriously implicated in several kinds of diseases including HTLV-I-associated myelopathy, Strongyloides stercoralis hyper-infection, and a virus cancer link for leukemia...

and AIDS.

- 1987 ConservativeConservative Party (UK)The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

Prime MinisterPrime Minister of the United KingdomThe Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Margaret ThatcherMargaret ThatcherMargaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

at the 1987 Conservative party conference, issued the statement stating "Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay". Backbench Conservative MPs and Peers had already begun a backlash against the 'promotion' of homosexuality and, in December 1987, Clause 28Section 28Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the controversial addition of Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 , enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of Great Britain by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003...

is introduced into the local government bill by Dame Jill Knight, ConservativeConservative Party (UK)The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

MP for Birmingham Edgbaston. The first UK specialist HIVHIVHuman immunodeficiency virus is a lentivirus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome , a condition in humans in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive...

ward was opened by Diana, Princess of WalesDiana, Princess of WalesDiana, Princess of Wales was the first wife of Charles, Prince of Wales, whom she married on 29 July 1981, and an international charity and fundraising figure, as well as a preeminent celebrity of the late 20th century...

; at the opening she made a point of not wearing protective gloves or a mask when she shook hands with the patients. AZTZidovudineZidovudine or azidothymidine is a nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitor , a type of antiretroviral drug used for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. It is an analog of thymidine....

, the first HIV drug to show promise of suppressing the disease was made available in the UK for the first time.

- 1988 Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988Local Government Act 1988The United Kingdom Local Government Act of 1988 was famous for introducing the controversial Section 28 into law. In terms of the section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, Local Authorities were prohibited from promoting in specified category of schools, "the teaching of the acceptability of...

enacted as an amendment to the United KingdomUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

's Local Government Act 1986, on 24 May 1988 stated that a local authority "shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship". The act was introduced by Margaret ThatcherMargaret ThatcherMargaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

. Almost identical legislation was enacted for Scotland by the Westminster Parliament. Princess MargaretPrincess Margaret, Countess of SnowdonPrincess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon was the younger sister of Queen Elizabeth II and the younger daughter of King George VI....

opens the UK's first residential support centre for people living with HIVHIVHuman immunodeficiency virus is a lentivirus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome , a condition in humans in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive...

and AIDSAIDSAcquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

in London at London Lighthouse.

- 1989 The campaign group Stonewall UK is set up to oppose Section 28Section 28Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the controversial addition of Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 , enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of Great Britain by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003...

and other barriers to equality.

1990s

- 1990 OutRage!OutRage!OutRage! is a British LGBT rights group that was formed to fight for equal rights of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in comparison to heterosexual people. It is a group which has at times been criticised for outing individuals who wanted to keep their homosexuality secret and for being...

, an LGBT rights direct action group, forms in the UK; the first "gay pride" event in Manchester. Oranges Are Not the Only FruitOranges Are Not the Only Fruit (TV serial)Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit was a critically acclaimed 1990 BBC television drama, directed by Beeban Kidron. Jeanette Winterson wrote the screenplay, adapting her semi-autobiographical first novel of the same name . The BBC produced and screened three episodes, running to a total of 2 hours and...

by Jeanette WintersonJeanette WintersonJeanette Winterson OBE is a British novelist.-Early years:Winterson was born in Manchester and adopted on 21 January 1960. She was raised in Accrington, Lancashire, by Constance and John William Winterson...

a semi-autobiographical screenplay about her lesbian life was shown on BBCBBCThe British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

television; Justin FashanuJustin FashanuJustinus Soni "Justin" Fashanu was an English footballer who played for a variety of clubs between 1978 and 1997. He was known by his early clubs to be homosexual, and came out to the press later in his career, to become the first professional footballer to be openly gay...

is the first professional footballer to come out in the press. Northern IrelandNorthern IrelandNorthern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

held their first Pride ParadeGay prideLGBT pride or gay pride is the concept that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people should be proud of their sexual orientation and gender identity...

.

- 1992 The first Pride FestivalGay prideLGBT pride or gay pride is the concept that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people should be proud of their sexual orientation and gender identity...

is held in Brighton; EuroprideEuroprideEuropride is a pan-European international event dedicated to LGBT pride, hosted by a different European city each year. The host city is usually one with an established gay pride event or a significant LGBT community....

was inaugurated in London and was attended by estimated crowds of over 100,000.

- 1994 The ConservativeConservative Party (UK)The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

Member of ParliamentParliament of the United KingdomThe Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

Edwina CurrieEdwina CurrieEdwina Jonesnée Cohen is a former British Member of Parliament. First elected as a Conservative Party MP in 1983, she was a Junior Health Minister for two years, before resigning in 1988 over the controversy over salmonella in eggs...

introduced an amendment to lower the age of consent for homosexual acts to 16 in line with that for heterosexual acts. The vote was defeated and the gay male age of consentAge of consentWhile the phrase age of consent typically does not appear in legal statutes, when used in relation to sexual activity, the age of consent is the minimum age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. The European Union calls it the legal age for sexual...

is set at 18. Lesbian age of consent was not set.

- 1997 Angela EagleAngela EagleAngela Eagle is a British Labour Party politician, who has been the Member of Parliament for Wallasey since 1992. She served as the Minister of State for Pensions and Ageing Society from June 2009 until May 2010. Eagle was elected to the Shadow Cabinet in October 2010 and was appointed by Ed...

, Labour MP for WallaseyWallaseyWallasey is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, in Merseyside, England, on the mouth of the River Mersey, at the northeastern corner of the Wirral Peninsula...

, becomes the first MP to come out voluntarily as a lesbian. Gay partners given equal immigration rights. The equal age of consentAge of consentWhile the phrase age of consent typically does not appear in legal statutes, when used in relation to sexual activity, the age of consent is the minimum age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. The European Union calls it the legal age for sexual...

to the Crime and Disorder Bill was law stalled by Conservative MP Baroness YoungJanet Young, Baroness YoungJanet Mary Baker Young, Baroness Young PC , was a British Conservative politician. She served as the first ever female Leader of the House of Lords from 1981 to 1983, first as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and from 1982 as Lord Privy Seal...

.

- 1998 The Bolton 7Bolton 7The Bolton 7 were a group of gay and bisexual men who were convicted on 12 January 1998 before Judge Michael Lever at Bolton Crown Court of the offences of gross indecency under the Sexual Offences Act 1956 and of age of consent offences under the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994...

, a group of gayGayGay is a word that refers to a homosexual person, especially a homosexual male. For homosexual women the specific term is "lesbian"....

and bisexual men were convicted at BoltonBoltonBolton is a town in Greater Manchester, in the North West of England. Close to the West Pennine Moors, it is north west of the city of Manchester. Bolton is surrounded by several smaller towns and villages which together form the Metropolitan Borough of Bolton, of which Bolton is the...

Crown Court of the offences of gross indecency under the Sexual Offences Act 1956Sexual Offences Act 1956The Sexual Offences Act 1956 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that consolidated the English criminal law relating to sexual offences between 1957 and 2004. It was mostly repealed by the Sexual Offences Act 2003 which replaced it, but sections 33 to 37 still survive. The 2003 Act...

and of age of consentAge of consentWhile the phrase age of consent typically does not appear in legal statutes, when used in relation to sexual activity, the age of consent is the minimum age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. The European Union calls it the legal age for sexual...

offences under the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It introduced a number of changes to the existing law, most notably in the restriction and reduction of existing rights and in greater penalties for certain "anti-social" behaviours...

. Although gay sex was partially decriminalised by the Sexual Offences Act 1967Sexual Offences Act 1967The Sexual Offences Act 1967 is an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom . It decriminalised homosexual acts in private between two men, both of whom had to have attained the age of 21. The Act applied only to England and Wales and did not cover the Merchant Navy or the Armed Forces...

, they were all convicted under section 13 of the 1956 Act because more than two men had sex together, which was still illegal.

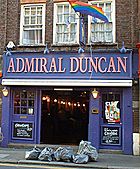

- 1999 Three people die in a nail bomb attack on a gay pub in London, the Admiral DuncanAdmiral Duncan pubThe Admiral Duncan is a pub in Old Compton Street, Soho in the heart of London's gay district. It is named after Admiral Adam Duncan, who defeated the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Camperdown in 1797.- Bombing :...

, in Soho, 30 April 1999.

21st century

- 2000 The Labour government scraps the policy of barring homosexuals from the armed forces. The Labour government introduces legislation to repeal Section 28Section 28Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the controversial addition of Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 , enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of Great Britain by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003...

in England and Wales - ConservativeConservative Party (UK)The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

MPs oppose the move. The bill is defeated by bishops and Conservatives in the House of Lords. ScotlandScotlandScotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

abolished Clause 2a (Section 28)Section 28Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the controversial addition of Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 , enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of Great Britain by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003...

of the Local Government Act in October and enacted this when the new guidance on sex education in schools was published in 2001.

- 2001 The age of consentAge of consentWhile the phrase age of consent typically does not appear in legal statutes, when used in relation to sexual activity, the age of consent is the minimum age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. The European Union calls it the legal age for sexual...

is reduced to 16 inline with the age of consent for heterosexuals; the last piece of unequal law regarding gay male sex changed with consensual group sex for gay men being decriminalised.

- 2002 Same-sex couples are granted equal rights to adopt. Alan DuncanAlan DuncanAlan James Carter Duncan is a British Conservative Party politician. He is the Member of Parliament for Rutland and Melton, and a Minister of State in the Department for International Development....

becomes the first Conservative MP to admit being gay without being pushed.

- 2003 Section 28Section 28Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the controversial addition of Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 , enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of Great Britain by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003...

, which banned councils and schools from intentionally promoting homosexuality, is repealed in England and Wales. Employment Equality Regulations made it illegal to discriminate against lesbians, gays or bisexuals at work; EuroPrideEuroprideEuropride is a pan-European international event dedicated to LGBT pride, hosted by a different European city each year. The host city is usually one with an established gay pride event or a significant LGBT community....

was hosted in Manchester.

- 2004 The Civil Partnership Act 2004 is passed by the Labour Government, giving same-sex couples the same rights and responsibilities as married heterosexual couples.

- 2005 The first couples enter into civil partnerships as the Civil Partnership Act 2004 comes into force. The Adoption and Children Act 2002 comes into force, allowing unmarried and same-sex couples to adopt children for the first time. Twenty-four-year-old Jody DobrowskiJody DobrowskiJody Dobrowski was a 24-year-old assistant bar manager who was murdered on Clapham Common in south London. On 14 October, at around midnight, he was beaten to death with punches and kicks by two men who believed him to be gay. Tests carried out at St...

is murdered on Clapham CommonClapham CommonClapham Common is an 89 hectare triangular area of grassland situated in south London, England. It was historically common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, but was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878.43 hectares of the common are within the...

in a homophobic attack.

- 2008 Treatment of lesbian parents and their children is equalized in the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008The Bill's discussion in Parliament did not permit time to debate whether it should extend abortion rights under the Abortion Act 1967 to also cover Northern Ireland...

. The legislation allows for lesbians and their partners (both civil and de facto) equal access to legal presumptions of parentage in cases of in vitro fertilisation ("IVF") or assisted/self insemination (other than at home) from the moment the child is born.

- 2009 The Labour Government Prime Minister Gordon BrownGordon BrownJames Gordon Brown is a British Labour Party politician who was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 until 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Labour Government from 1997 to 2007...

makes an official public apology on behalf of the British government for the way in which Alan TuringAlan TuringAlan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS , was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which played a...

was treated after the war. Opposition leader David CameronDavid CameronDavid William Donald Cameron is the current Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, First Lord of the Treasury, Minister for the Civil Service and Leader of the Conservative Party. Cameron represents Witney as its Member of Parliament ....

apologises on behalf of the Conservative Party, for introducing Section 28Section 28Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the controversial addition of Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 , enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of Great Britain by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003...

during Margaret ThatcherMargaret ThatcherMargaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

's third government.

- 2010 Pope Benedict XVIPope Benedict XVIBenedict XVI is the 265th and current Pope, by virtue of his office of Bishop of Rome, the Sovereign of the Vatican City State and the leader of the Catholic Church as well as the other 22 sui iuris Eastern Catholic Churches in full communion with the Holy See...

condemns British equality legislation for running contrary to "natural law" as he confirmed his first visit to the UK. The Equality Act 2010 makes discrimination against lesbians and gay men in the provision of goods and services illegal; the Supreme CourtSupreme Court of the United KingdomThe Supreme Court of the United Kingdom is the supreme court in all matters under English law, Northern Ireland law and Scottish civil law. It is the court of last resort and highest appellate court in the United Kingdom; however the High Court of Justiciary remains the supreme court for criminal...

ruled that two gay men from Iran and Cameroon have the right to asylum in the UK. Lord HopeDavid Hope, Baron Hope of CraigheadJames Arthur David Hope, Baron Hope of Craighead, is a Scottish judge and Deputy President of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, having previously been the Second Senior Lord of Appeal in Ordinary.-Early life:...

, who read out the judgment, said: "To compel a homosexual person to pretend that his sexuality does not exist or suppress the behaviour by which to manifest itself is to deny him the fundamental right to be who he is."

See also

- History of human sexualityHistory of human sexualityThe social construction of sexual behavior—its taboos, regulation and social and political impact—has had a profound effect on the various cultures of the world since prehistoric times.- Sources :...

- LGBT historyLGBT historyLGBT history refers to the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender peoples and cultures around the world, dating back to the first recorded instances of same-sex love and sexuality of ancient civilizations. What survives of many centuries' persecution– resulting in shame, suppression,...

- Hall–Carpenter Archives the national archive of LGBT history

- List of pre-Stonewall LGBT actions in the United States

- Table of years in LGBT rightsTable of years in LGBT rights-See also:*LGBT rights by country or territory — current legal status around the world*LGBT social movements — historical and contemporary movements...

- Timeline of LGBT history in CanadaTimeline of LGBT history in CanadaThis is a timeline of notable events in the history of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community in Canada.-19th century:* 1810: Alexander Wood, a merchant and magistrate in Toronto, is embroiled in a sex scandal when he investigates a rape case by personally inspecting the penises of...

- Timeline of sexual orientation and medicineTimeline of sexual orientation and medicineTimeline of events related to sexual orientation and medicine-19th century:1886*Dr. Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing, a German psychiatrist, publishes a study of sexual perversity.-20th century:1948...

Further reading

- Cook, Matt : London and the culture of homosexuality, 1885-19

- Cook, Matt : Gay history of GB: love & sex between men since

- David, Hugh : On queer street: a social history of British homosexuals

- Houlbrook, Matt : Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 ISBN 978-0-226-35462-0