History of the Conservative Party

Encyclopedia

The modern Conservative Party

of the United Kingdom

, also known as the Unionist Party in the early 20th century, traces its origins back to the "Tory" supporters of Duke of York

, later King James VII&II, during the 1678-1681 exclusion. The name was originally meant as a pejorative—a 'Tory' was a type of Irish bandit.

The name 'Conservative' was suggested by John Wilson Croker

in the 1830s and later officially adopted, but the party is still often referred to as the 'Tory Party' (not least because newspaper editors find it a convenient shorthand when space is limited). The Tories more often than not formed the government

from the accession of King George III

(in 1760) until the Reform Act 1832

.

Widening of the franchise in the 19th century led the party to popularise its approach, especially under Benjamin Disraeli, his own Reform Act

coming in 1867. After 1886, the Conservatives allied with the part of the Liberal Party

known as the Liberal Unionists who opposed their party's support for Irish Home Rule and held office for all but three of the following twenty years. During this period the party was generally known as the Unionist Party, and it suffered a large defeat when the party split over tariff reform in 1906.

World War I

saw an all-party coalition, and for four years after the armistice the party remained in coalition with the Lloyd George Liberals. Eventually, grassroots pressure forced the breakup of the Coalition, and the party regained power on its own. It again dominated the political scene in the inter-war period, from 1931 in a 'National Government

' coalition. However in the 1945 general election

the party lost power in a landslide to the Labour Party

.

After the end of the Second World War

, the Conservatives accepted the reality of the Labour government's nationalisation programme, the creation of the 'welfare state', and the high taxes required for all of it. But when they returned to power in 1951 the party oversaw an economic boom and ever-increasing national prosperity throughout the 1950s. The party stumbled in the 1960s and 1970s, but in 1975 Margaret Thatcher became leader and converted it to a monetarist economic programme; after her election victory in 1979 her government became known for its free market

approach to problems and privatisation of public utilities. Here, the Conservatives experienced a high-point, Thatcher leading the Conservatives to two more landslide election victories in 1983 and 1987.

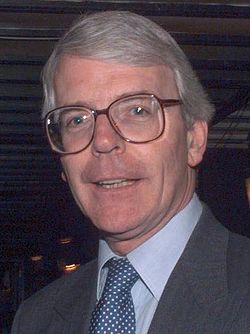

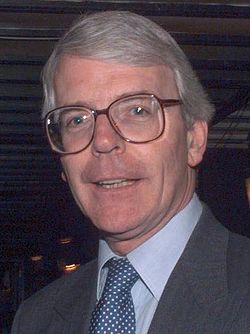

However, towards the end of the 1980s, Thatcher's increasing unpopularity and unwillingness to change policies perceived as vote-losing led to her being deposed in 1990 and replaced by John Major

who won an unexpected election victory in 1992. Major's government suffered a political blow when the Pound Sterling

was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism

later that year, which lost the party much of its reputation for good financial stewardship. Although the country's economy recovered in the mid-1990s, an effective opposition campaign by the Labour Party led to a landslide defeat in 1997.

and his successors, who gradually came to be called Tories. In the late 1820s disputes over political reform broke up this grouping. A government led by the Duke of Wellington

collapsed amidst dire election results. Following this disaster Robert Peel

set about assembling a new coalition of forces. Peel issued the Tamworth Manifesto

in 1834 which set out the basic principles of Conservatism

and that year he formed a temporary government. On the fall of Lord Melbourne

's government in 1841 Peel took office with a substantial majority and appeared set for a long rule.

. Peel and most senior Conservatives favoured repeal, but they were opposed by backbench members representing farming and rural constituencies, led by Lord George Bentinck

, Benjamin Disraeli

, and Lord Stanley

(later the Earl of Derby), who favoured protectionism

. Following repeal, the Protectionists combined with the Whigs to overthrow Peel's government. It would be twenty-eight years before a Conservative Prime Minister again had a majority in the House of Commons.

From this point on, and especially after the death of Peel in 1850, the Peelites and Conservatives drifted apart. Most of the Peelites joined with the Whigs and Radicals to form the Liberal Party

in 1859, under the leadership of Lord Palmerston

.

, which broadened the franchise. Disraeli's mixed message of patriotism and promises of social reforms managed to win him enough working-class support to win a majority in 1874

, but the Conservative hold remained tenuous, and Disraeli was defeated in the election of 1880

. It was not until the split in the Liberal Party

over Irish home rule in 1886 that the Conservatives were able to achieve truly secure majorities through the defection of the Liberal Unionists

.

became Prime Minister.

The party then split on the issue of Tariff Reform. The controversy had been taken up by the Liberal Unionist cabinet minister Joseph Chamberlain

, who was Colonial Secretary

. Like the earlier schism over the Corn Laws

in 1846, the result lead to polarisation within the coalition between those who supported Chamberlain and his 'Imperial Preference', and those who opposed him in defence of the status quo and Free Trade

. The split went across both Unionist parties. With the beleaguered Balfour in the middle, the government struggled on for another two years and saw many Unionist MPs defect to the Liberals. These defectors included the future Conservative party leader Winston Churchill

in 1904.

ended in a landslide defeat for the Unionists and their numbers were reduced to only 157 MPs. The Unionists had been suffering as a result of the unpopular Boer War

, (known as Joe's War, a particular link to Joseph Chamberlain) as well as the unpopular tariff reforms proposed by Chamberlain, which faced the growing popularity of free trade

amongst the population. Chamberlain himself was told to keep his "hands off the peoples food!" Balfour lost his own seat (although he soon returned to Parliament in a by-election) and this left the pro-tariff reformers within the Unionists as a large majority. However, the stroke suffered by Joseph Chamberlain in July 1906 effectively removed him from political influence. The cause of Tariff reform would now be promoted by Chamberlain's son Austen Chamberlain

.

The Unionists strongly opposed many of the proposed reforms of the new Liberal governments of Campbell-Bannerman

and Asquith. In 1910, the Unionist-dominated House of Lords

rejected the so-called "People's Budget

", leading to a long conflict over the nature and constitutional place of the House of Lords. The Conservatives managed to make up much of their losses in both the January and December elections of 1910. This forced the Liberals to rely on Irish Nationalist votes to maintain their majority. Although the Liberals were able to force through the effective subjugation of the Lords with the Parliament Act 1911

, their advocacy once again cost them support, so that by the time of the outbreak of World War I

a Unionist victory in the next election looked possible. Liberal mismanagement of the early phases World War I led to the return of the Unionists to power: first in coalition with Asquith's Liberals, and then, with the split and collapse of the Liberals, the Unionists under Andrew Bonar Law were able to become the dominant party in Lloyd George's

coalition government following the 1918 election

.

For the next few years it seemed possible that the Liberals who supported Lloyd George and the Conservatives would merge into a new political grouping. However the reluctance of these Liberals to lose their identity ended this ambition and the moment was lost. From then on the rumblings of discontent within the coalition over issues such as the Soviet Union

For the next few years it seemed possible that the Liberals who supported Lloyd George and the Conservatives would merge into a new political grouping. However the reluctance of these Liberals to lose their identity ended this ambition and the moment was lost. From then on the rumblings of discontent within the coalition over issues such as the Soviet Union

, trade unions and the Irish issue (leading to the de facto independence for the Irish Free State

in 1921 led to many Conservatives hoping to break with Lloyd George. Bonar Law resigned in 1921 on the grounds of ill health and the parliamentary party was now led by Austen Chamberlain

. Previously a contender for party leadership in 1911, Chamberlain was to prove ineffective in controlling his party—even passing up the offer of becoming Prime Minister when Lloyd George indicated he was willing to step down. The party eventually broke free from Lloyd George in October 1922 as the result of a meeting of MPs at the Carlton Club

. They voted against remaining in the coalition and Chamberlain resigned. He was actually replaced by Bonar Law, who had been persuaded by friends and allies to return to lead the party.

After winning the election of 1922

, Bonar Law, now terminally ill with throat cancer, was to resign for good from political life in May 1923. He died later that year. Though holding a majority in government, the party was still split, as many of those who stayed to the bitter end of the former coalition had refused to take office in Law's cabinet. Their absence explains why the hitherto unknown Stanley Baldwin

was to become leader of the party barely two years after first entering a major ministerial post.

The party reached a new height in the inter-war years under Baldwin's leadership. His mixture of strong social reforms and steady government proved a powerful election combination, with the result that the Conservatives governed Britain either by themselves or as the leading component of the National Government

for most of the interwar years and all through World War II

. The Conservatives under Baldwin were also the last political party in Britain to gain over 50% of the vote (in the general election of 1931

). Yet at the conclusion of hostilities, the British public felt a different party would best guide them through the peace, and the Conservatives were soundly defeated in the 1945 General Election

by a resurgent Labour Party.

government's social reforms whilst also offering a distinctive Conservative edge, as set out in their 1947 poicy statement Industrial Charter

. They returned to government in 1951

under Churchill. Churchill remained leader for another four years, during which time the Conservatives showed their acceptance of Labour reforms, though modifying some, such as the denationalisation the steel industry. In 1955 Churchill retired and was succeeded by Sir Anthony Eden

. Eden had an immense personal popularity and lengthy experience as Foreign Secretary, but his government ran into a number of troubles on the domestic front as the economy began to overheat. In international affairs the government was confronted by the decision of the Egypt

ian government of Gamal Abdel Nasser

to nationalise the Suez Canal

. Eden agreed to a secret collaboration with France

and Israel

to retake the Canal, but the resulting operation [see Suez Crisis

] backfired miserably and left the United Kingdom heavily embarrassed abroad and Eden discredited at home. With his health failing, Eden resigned at the beginning of 1957.

The succession was contentious, with Rab Butler

as the favourite to succeed. However, it was Harold Macmillan

who became the next Prime Minister and leader of the party. Macmillan sought to rebuild the government's image both at home and abroad, and presided over strong economic growth and a massive expansion in the consumer-product economy. In 1959 he won the general election of that year

on this economic success, summed up in the slogan "You've never had it so good." However, rising unemployment and an economic downturn in the early 1960s eroded support for Macmillan's government. It was further rocked in 1963 by the resignation of the Secretary of State for War John Profumo

over the Profumo Affair

. In October 1963 Macmillan was misdiagnosed with terminal cancer and resigned.

The party at this time lacked a formal process for electing a new leader and Macmillan's resignation took place in the week of the annual Conservative Party Conference. This event rapidly became an American-style convention as leading ministers sought to establish their credentials. Eventually Macmillan formally recommended to the Queen

that she appoint the Earl of Home

as Prime Minister. Home was appointed and renounced his peerage, becoming Sir Alec Douglas-Home, but was unable to restore the party's fortunes and narrowly lost the 1964 general election

.

Following the 1964 defeat, the party formally installed a system for electing the leader. Douglas-Home stepped down in 1965 and the election to succeed him

Following the 1964 defeat, the party formally installed a system for electing the leader. Douglas-Home stepped down in 1965 and the election to succeed him

was won by Edward Heath

over both Reginald Maudling

and Enoch Powell

. The party proceeded to lose the 1966 general election

. Heath's leadership proved controversial, with frequent calls from many prominent party members and supporters for him to step down, but he persevered. To the shock of almost everyone bar Heath, the party won the 1970 general election

.

As with all British governments in this period, Heath's time in office was difficult. Furthermore, the Heath premiership remains one of the most controversial in the history of the party. Initial attempts to follow monetarist policies (later considered "Thatcherite") failed, with high inflation and unemployment blocking Heath's attempts at reforming the increasingly militant trade unions. The era of 1970s British industrial unrest had arrived.

The Troubles

in Northern Ireland would lead Heath to suspending the Parliament of Northern Ireland

and introducing direct rule

as a precursor to establishing a power-sharing executive under the Sunningdale Agreement

. This resulted in the Conservative Party losing the support of the Ulster Unionist Party

at Westminster, which was to have consequences in later years when the party found itself reliant on tiny Commons majorities. Heath himself considered his greatest success in office to be the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community (or the "Common Market" as it was widely called at the time) but in subsequent years the UK's membership of the EEC was to prove the source of the greatest division in the party.

The country suffered a further bout of inflation in 1973 as a result of the OPEC

cartel raising oil prices, and this in turn led to renewed demands for wage increases in the coal industry. The government refused to accede to the miner's demands, resulting in a series of stoppages and massive attempts to ration power, including the "Three Day Week". Heath decided to call a snap election on the question of "Who Governs Britain?". However the Conservative Party was unprepared, whilst the miners' unions stated that they did not see how the re-election of the government would change the situation. The Conservatives were further rocked by the death of Iain Macleod

and the resignation of Enoch Powell

, who denounced the government for taking the country into the EEC and called on voters to back the Labour Party, who had promised a referendum

on withdrawal. The February 1974 election

produced an unusual result as support for the Liberals, Scottish National Party

and Plaid Cymru

all surged, Northern Ireland

's politics became more localised, whilst the Conservatives won a plurality of votes but Labour had a plurality of seats. With a hung Parliament

elected and the Ulster Unionists refusing to support the Conservative party, Heath tried to negotiate with the Liberals to form a coalition, but the attempts foundered on demands that were not acceptable to both parties. Heath was forced to resign as Prime Minister.

These years were seen as the height of "consensus politics". However, by the 1970s many traditional methods of running the economy, managing relations with trade unions, and so on began to fail—or had outright already failed. This was also a period of Labour-Party ascendancy, as they ruled for nearly twelve out of the fifteen years between 1964 and 1979. Many in the Conservative Party were left wondering how to proceed.

Heath remained leader of the party despite growing challenges to his mandate. At the time there was no system for challenging an incumbent, leader but after renewed pressure and a second general election defeat

Heath remained leader of the party despite growing challenges to his mandate. At the time there was no system for challenging an incumbent, leader but after renewed pressure and a second general election defeat

a system was put in place and Heath agreed to holding a leadership election

to allow him to renew his mandate. Few both inside and out of the party expected him to be seriously challenged, let alone defeated. However Margaret Thatcher

stood against Heath and in a shock result outpolled him on the first ballot, leading him to withdraw from the contest. Thatcher then faced off four other candidates to become the first woman to lead a major British political party. Thatcher had much support from the monetarists

, led by Keith Joseph

. The Conservatives capitalised on the Winter of Discontent

and the growing inflation rate, not to mention the humiliating bailout of the UK economy by the IMF

in 1976, and won the 1979 general election

with a majority of 43. Thatcher, thereby became the UK's first woman Prime Minister.

Thatcher soon introduced controversial and difficult, but ultimately successful, economic reforms after two decades of decline. The Falklands War

, the perceived extreme left

nature of the Labour Party, and the intervention of the centrist SDP-Liberal Alliance

all contributed to her party winning the 1983 general election

in a landslide, gaining a majority of 144. Thatcher won the 1987 general election

with another large, but reduced majority of 102.

The second and third terms were dominated by privatisations of Britain's many state-owned industries, including British Telecom in 1984, the bus companies in 1985, British Gas

in 1986, British Airways

in 1987, British Leyland, and British Steel

in 1988. In 1984 Mrs. Thatcher also successfully concluded five-year long negotiations over Britain's budget to the European Economic Community. (See UK rebate

.)

In 1989, the Community Charge

(frequently referred to as the "poll tax

") was introduced to replace the ancient system of rates (based on property values) which funded local government. This unpopular new charge was a flat rate per adult no matter what their circumstances; it seemed to be shifting the tax burden disproportionately onto the poor. Once again Thatcher's popularity sagged, but this time the Conservatives thought it might cost them the election. Michael Heseltine

, a former cabinet member, challenged her for the leadership in 1990

. She won the first round, but not enough to win outright, and after taking soundings from cabinet members, she announced her intention not to contest the second ballot. In the ensuing second ballot, the Chancellor of the Exchequer

John Major

beat Heseltine and Douglas Hurd

.

Major introduced a replacement for the Community Charge, the Council Tax

Major introduced a replacement for the Community Charge, the Council Tax

, and continued with the privatisations, and went on to narrowly win the 1992 election

with a majority of 21.

Major's government was beset by scandals, crisis, and missteps. Many of the scandals were about the personal lives of politicians which the media construed as hypocrisy, but the Cash for Questions affair and the divisions over EU

were substantive. In 1995, Major resigned as Leader of the Conservative Party in order to trigger a leadership election

which he hoped would give him a renewed mandate, and quieten the Maastricht rebels (e.g. Iain Duncan Smith

, Bill Cash, Bernard Jenkin

). John Redwood

, then Secretary of State for Wales, stood against Major and gained around a fifth of the leadership vote. He was one of the people whom Major inadvertently referred to as 'bastards' during a television interview. Major was pleased that Michael Heseltine

had not stood against him and gave him the position of Deputy Prime Minister

as a result.

As the term went on, with by-elections being consistently lost by the Conservatives, their majority declined and eventually vanished entirely. Getting every vote out became increasingly important to both sides, and on several occasions ill MPs were wheeled into the Commons

to vote. Eventually, the Government became a technical minority.

As predicted, the general election of May 1997

was a win for the Labour Party, but the magnitude of the victory surprised almost everyone. There was a swing of 20% in some places, and Labour achieved a majority of 179 with 43% of the vote to the Conservatives' 31%. Tactical voting

against the Conservatives is believed to have caused around 40 seats to change hands. They lost all their seats outside of England, with prominent members such as Michael Portillo

and Malcolm Rifkind

among the losses. Major resigned within 24 hours.

It is often said that the Conservatives lost the 1997 election due to EU party-policy divisions. However, it is likely that the European question played only a small or insignificant part in the result. Accusations of "Tory sleaze", apathy towards a government that had been in power for nearly two decades, and a rebranded "New" Labour Party with a dynamic and charismatic leader (Tony Blair

) are all probable factors in the Conservative defeat.

and hypocrisy

. In particular the successful entrapment of Graham Riddick

and David Tredinnick

in the "cash for questions" scandal, the contemporaneous misconduct as a minister by Neil Hamilton

(who lost a consequent libel action against The Guardian), and the convictions of former Cabinet member Jonathan Aitken

and former party deputy chairman Jeffrey Archer for perjury

in two separate cases leading to custodial sentences damaged the Conservatives' public reputation. Persistent unsubstantiated rumours about the activities of the party treasurer Michael Ashcroft did not help this impression.

At the same time a series of revelations about the private lives of various Conservative politicians also grabbed the headlines and both the media and the party's opponents made little attempt to clarify the distinction between financial conduct and private lives.

John Major

's "Back to Basics

" morality campaign back-fired on him by providing an excuse for the British media to expose "sleaze" within the Conservative Party and, most damagingly, within the Cabinet itself. A number of ministers were then revealed to have committed sexual indiscretions, and Major was forced by media pressure to dismiss them. In September 2002 it was revealed that, prior to his promotion to the cabinet, Major had himself had a longstanding extramarital affair with a fellow MP, Edwina Currie

.

was contested by five candidates. The electorate for the contest consisted solely of the 165 Conservative MPs who had been returned to the House of Commons. The candidates were Kenneth Clarke

, William Hague

, John Redwood

, Peter Lilley

and Michael Howard

, with Stephen Dorrell

launching an initial bid but withdrawing before polling began, citing limited support, and backing Clarke. Clarke was the favoured candidate of the Europhile

left of the party, while the three latter candidates divided right-wing support roughly equally. Hague, who had initially supported Howard, emerged second as a compromise candidate and won the final ballot after Redwood and Clarke negotiated a joint ticket which was derided as an Instability Pact by their opponents (punning on the economic Stability Pact of the European Community).

At first William Hague portrayed himself as a moderniser with a common touch. However by the time the 2001 general election

came he concentrated on Europe, asylum seekers and tax cuts whilst declaring that only the Conservative Party could "Save the Pound". Though a master debater who would regularly trounce Tony Blair in the Commons, his leadership tenure was beset by poor publicity and stumbles. Despite a low turnout, the election resulted in a net gain of a single seat for the Conservative Party and William Hague's resignation as party leader.

was conducted under a new leadership electoral system designed by Hague. This resulted in five candidates competing for the job: Michael Portillo

, Iain Duncan Smith

, Kenneth Clarke

, David Davis

and Michael Ancram

. The drawn-out and at times acrimonious election saw Conservative MPs select Iain Duncan Smith and Ken Clarke to be put forward for a vote by party members. As Conservative Party members are characteristically Eurosceptic, Iain Duncan Smith was elected, even though opinion polls showed that the public preferred Ken Clarke, a member of the Tory Reform Group

. (Main article: 2001 Conservative leadership election.)

Iain Duncan Smith (often known as IDS) was a strong Eurosceptic

but this did not define his leadership - indeed it was during his tenure that Europe ceased to be an issue of division in the party as it united behind calls for a referendum on the proposed European Union Constitution. Duncan Smith's Shadow Cabinet

contained many new and unfamiliar faces but despite predictions by some that the party would lurch to the right the team instead followed a pragmatic moderate approach to policy.

On 27 October Iain Duncan Smith began to face calls within his own party to either resign as leader or face a vote of confidence. Under the rules of the Conservative party, the backbench Conservative 1922 Committee would review the leadership, and in order for this to take place the chairman of the committee, Sir Michael Spicer must be presented with 25 letters proposing a vote.

On 28 October sufficient letters were presented to the chairman of the 1922 Committee to initiate a vote of confidence in Iain Duncan Smith. The vote came on 29 October, and IDS lost 90 to 75.

, MP

for Folkestone

and Hythe

, was elected to the post of leader

(as the only candidate) on 6 November 2003.

Howard announced radical changes to the way the Shadow Cabinet

would work. He slashed the number of members by half, with Theresa May

and Tim Yeo

each shadowing two government departments. Minor departments still have shadows but have been removed from the cabinet, and the post of Shadow Leader of the House of Commons

was abolished. The role of party chairman was also split into two, with Lord Saatchi responsible for the party machine, and Liam Fox

handling publicity. Michael Portillo

was offered a position but refused, due to his plans to step down from Parliament at the next election.

Also, a panel of "grandees", including John Major

, Iain Duncan Smith

, William Hague

and, notably, Kenneth Clarke

has been set up to advise the leadership as they see fit.

On 2 January 2004, influenced by Saatchi, Howard defined a personal credo and list of core beliefs of the party. At the party conference of October 2004, the Conservatives presented their "Timetable For Action

" that a Conservative government would follow.

In the 2005 general election, the Conservative Party made a partial recovery by a net gain of 31 seats, with the Labour majority falling to 66.

The day after, on 6 May, Howard announced that he believed himself too old to lead the party into another election campaign, and he would therefore be stepping down to allow a new leader the time to prepare for the next election. Howard said that he believed that the party needed to amend the rules governing the election of the Party leader, and that he would allow time for that to happen before resigning. See Conservative Party (UK) leadership election, 2005

The 2005 campaign received criticism from its main financial backer, Michael Spencer

. In an interview with The Times

Tim Collins

claimed that the specific reasons the party won more seats may not repeat themselves in the next general election::

won the subsequent leadership campaign on 6 December 2005. Cameron beat his closest rival David Davis

by a margin of more than two to one, taking 134,446 votes to 64,398, and announced his intention to reform and realign the Conservative Party in a manner similar to that achieved by the Labour Party in opposition under Tony Blair. As part of this he distanced from himself from the much hated Conservative Party of the past, for example apologising for Section 28

, and focused in on modern environmental issues.

In April 2006 the party set out to deliver a promise by Cameron to modernize its parliamentary representation. A central candidates' committee reduced some five hundred aspiring politicians on the party's list of approved parliamentary candidates to an "A-list" of between 100 and 150 priority candidates. More than half of the names on the resulting list proved to be female, and several were of non-Establishment figures of various kinds.

After the party had led in opinion poll

s for most of Cameron's time in office, a hung parliament

was achieved in the 2010 General Election, with the Conservatives achieving the most votes and largest number of seats in parliament. This outcome had been widely predicted and was largely due to a surge in support for the Liberal Democrats. Cameron successfully negotiated with the Liberal Democrats

on forming a coalition government

.

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

of the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, also known as the Unionist Party in the early 20th century, traces its origins back to the "Tory" supporters of Duke of York

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

, later King James VII&II, during the 1678-1681 exclusion. The name was originally meant as a pejorative—a 'Tory' was a type of Irish bandit.

The name 'Conservative' was suggested by John Wilson Croker

John Wilson Croker

John Wilson Croker was an Irish statesman and author.He was born at Galway, the only son of John Croker, the surveyor-general of customs and excise in Ireland. He was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, where he graduated in 1800...

in the 1830s and later officially adopted, but the party is still often referred to as the 'Tory Party' (not least because newspaper editors find it a convenient shorthand when space is limited). The Tories more often than not formed the government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...

from the accession of King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

(in 1760) until the Reform Act 1832

Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 was an Act of Parliament that introduced wide-ranging changes to the electoral system of England and Wales...

.

Widening of the franchise in the 19th century led the party to popularise its approach, especially under Benjamin Disraeli, his own Reform Act

Reform Act 1867

The Representation of the People Act 1867, 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102 was a piece of British legislation that enfranchised the urban male working class in England and Wales....

coming in 1867. After 1886, the Conservatives allied with the part of the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

known as the Liberal Unionists who opposed their party's support for Irish Home Rule and held office for all but three of the following twenty years. During this period the party was generally known as the Unionist Party, and it suffered a large defeat when the party split over tariff reform in 1906.

World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

saw an all-party coalition, and for four years after the armistice the party remained in coalition with the Lloyd George Liberals. Eventually, grassroots pressure forced the breakup of the Coalition, and the party regained power on its own. It again dominated the political scene in the inter-war period, from 1931 in a 'National Government

UK National Government

In the United Kingdom the term National Government is an abstract concept referring to a coalition of some or all major political parties. In a historical sense it usually refers primarily to the governments of Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain which held office from 1931...

' coalition. However in the 1945 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1945

The United Kingdom general election of 1945 was a general election held on 5 July 1945, with polls in some constituencies delayed until 12 July and in Nelson and Colne until 19 July, due to local wakes weeks. The results were counted and declared on 26 July, due in part to the time it took to...

the party lost power in a landslide to the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

.

After the end of the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the Conservatives accepted the reality of the Labour government's nationalisation programme, the creation of the 'welfare state', and the high taxes required for all of it. But when they returned to power in 1951 the party oversaw an economic boom and ever-increasing national prosperity throughout the 1950s. The party stumbled in the 1960s and 1970s, but in 1975 Margaret Thatcher became leader and converted it to a monetarist economic programme; after her election victory in 1979 her government became known for its free market

Free market

A free market is a competitive market where prices are determined by supply and demand. However, the term is also commonly used for markets in which economic intervention and regulation by the state is limited to tax collection, and enforcement of private ownership and contracts...

approach to problems and privatisation of public utilities. Here, the Conservatives experienced a high-point, Thatcher leading the Conservatives to two more landslide election victories in 1983 and 1987.

However, towards the end of the 1980s, Thatcher's increasing unpopularity and unwillingness to change policies perceived as vote-losing led to her being deposed in 1990 and replaced by John Major

John Major

Sir John Major, is a British Conservative politician, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990–1997...

who won an unexpected election victory in 1992. Major's government suffered a political blow when the Pound Sterling

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism

Black Wednesday

In politics and economics, Black Wednesday refers to the events of 16 September 1992 when the British Conservative government was forced to withdraw the pound sterling from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism after they were unable to keep it above its agreed lower limit...

later that year, which lost the party much of its reputation for good financial stewardship. Although the country's economy recovered in the mid-1990s, an effective opposition campaign by the Labour Party led to a landslide defeat in 1997.

Origins

The modern Conservative Party arose in the 1830s, but has as an ancestor the Tory parties of the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Political alignments in those centuries were much looser than now, with many individual groupings. From the 1780s until the 1820s the dominant grouping were those Whigs following William Pitt the YoungerWilliam Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

and his successors, who gradually came to be called Tories. In the late 1820s disputes over political reform broke up this grouping. A government led by the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS , was an Irish-born British soldier and statesman, and one of the leading military and political figures of the 19th century...

collapsed amidst dire election results. Following this disaster Robert Peel

Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 December 1834 to 8 April 1835, and again from 30 August 1841 to 29 June 1846...

set about assembling a new coalition of forces. Peel issued the Tamworth Manifesto

Tamworth Manifesto

The Tamworth Manifesto was a political manifesto issued by Sir Robert Peel in 1834 in Tamworth, which is widely credited by historians as having laid down the principles upon which the modern British Conservative Party is based....

in 1834 which set out the basic principles of Conservatism

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

and that year he formed a temporary government. On the fall of Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, PC, FRS was a British Whig statesman who served as Home Secretary and Prime Minister . He is best known for his intense and successful mentoring of Queen Victoria, at ages 18-21, in the ways of politics...

's government in 1841 Peel took office with a substantial majority and appeared set for a long rule.

Crisis over the Corn Laws

However in 1846 disaster struck when the party split over the repeal of the Corn LawsCorn Laws

The Corn Laws were trade barriers designed to protect cereal producers in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports between 1815 and 1846. The barriers were introduced by the Importation Act 1815 and repealed by the Importation Act 1846...

. Peel and most senior Conservatives favoured repeal, but they were opposed by backbench members representing farming and rural constituencies, led by Lord George Bentinck

Lord George Bentinck

Lord George Frederick Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck , better known as simply Lord George Bentinck, was an English Conservative politician and racehorse owner, best known for his role in unseating Sir Robert Peel over the Corn Laws.Bentinck was a younger son of the 4th Duke of Portland, and elected a...

, Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, was a British Prime Minister, parliamentarian, Conservative statesman and literary figure. Starting from comparatively humble origins, he served in government for three decades, twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom...

, and Lord Stanley

Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, KG, PC was an English statesman, three times Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and to date the longest serving leader of the Conservative Party. He was known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley...

(later the Earl of Derby), who favoured protectionism

Protectionism

Protectionism is the economic policy of restraining trade between states through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, restrictive quotas, and a variety of other government regulations designed to allow "fair competition" between imports and goods and services produced domestically.This...

. Following repeal, the Protectionists combined with the Whigs to overthrow Peel's government. It would be twenty-eight years before a Conservative Prime Minister again had a majority in the House of Commons.

From this point on, and especially after the death of Peel in 1850, the Peelites and Conservatives drifted apart. Most of the Peelites joined with the Whigs and Radicals to form the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

in 1859, under the leadership of Lord Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

.

Recovery and triumph under Derby and Disraeli

The Conservatives survived as an independent party, even though they would not form another majority government until the 1870s. The modern Conservative Party descends from the Protectionists who broke with Peel in 1846, although they did not reintroduce Protection when they were returned to power. Under the leadership of Derby and Disraeli they consolidated their position and slowly rebuilt the strength of the party. Although Derby led several minority governments in the 1850s and 1860s, the party could not achieve a majority until 1874, after the passage of the Reform Act of 1867Reform Act 1867

The Representation of the People Act 1867, 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102 was a piece of British legislation that enfranchised the urban male working class in England and Wales....

, which broadened the franchise. Disraeli's mixed message of patriotism and promises of social reforms managed to win him enough working-class support to win a majority in 1874

United Kingdom general election, 1874

-Seats summary:-References:* F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987* British Electoral Facts 1832-1999, compiled and edited by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher *...

, but the Conservative hold remained tenuous, and Disraeli was defeated in the election of 1880

United Kingdom general election, 1880

-Seats summary:-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987* British Electoral Facts 1832-1999, compiled and edited by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher *...

. It was not until the split in the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

over Irish home rule in 1886 that the Conservatives were able to achieve truly secure majorities through the defection of the Liberal Unionists

Liberal Unionist Party

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington and Joseph Chamberlain, the party formed a political alliance with the Conservative Party in opposition to Irish Home Rule...

.

The Unionist Ascendancy

The Conservatives, now led by Lord Salisbury, remained in power for most of the next twenty years, at first passively supported by the Liberal Unionists and then, after 1895, in active coalition with them. From 1895, unofficially, and after 1912 officially, the Conservative-Liberal Unionist coalition was often simply called the "Unionists". In 1902 Salisbury retired and his nephew Arthur BalfourArthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, DL was a British Conservative politician and statesman...

became Prime Minister.

The party then split on the issue of Tariff Reform. The controversy had been taken up by the Liberal Unionist cabinet minister Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain was an influential British politician and statesman. Unlike most major politicians of the time, he was a self-made businessman and had not attended Oxford or Cambridge University....

, who was Colonial Secretary

Secretary of State for the Colonies

The Secretary of State for the Colonies or Colonial Secretary was the British Cabinet minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various colonial dependencies....

. Like the earlier schism over the Corn Laws

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were trade barriers designed to protect cereal producers in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports between 1815 and 1846. The barriers were introduced by the Importation Act 1815 and repealed by the Importation Act 1846...

in 1846, the result lead to polarisation within the coalition between those who supported Chamberlain and his 'Imperial Preference', and those who opposed him in defence of the status quo and Free Trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

. The split went across both Unionist parties. With the beleaguered Balfour in the middle, the government struggled on for another two years and saw many Unionist MPs defect to the Liberals. These defectors included the future Conservative party leader Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

in 1904.

Early twentieth century

The election of 1906United Kingdom general election, 1906

-Seats summary:-See also:*MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1906*The Parliamentary Franchise in the United Kingdom 1885-1918-External links:***-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987**...

ended in a landslide defeat for the Unionists and their numbers were reduced to only 157 MPs. The Unionists had been suffering as a result of the unpopular Boer War

Boer War

The Boer Wars were two wars fought between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics, the Oranje Vrijstaat and the Republiek van Transvaal ....

, (known as Joe's War, a particular link to Joseph Chamberlain) as well as the unpopular tariff reforms proposed by Chamberlain, which faced the growing popularity of free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

amongst the population. Chamberlain himself was told to keep his "hands off the peoples food!" Balfour lost his own seat (although he soon returned to Parliament in a by-election) and this left the pro-tariff reformers within the Unionists as a large majority. However, the stroke suffered by Joseph Chamberlain in July 1906 effectively removed him from political influence. The cause of Tariff reform would now be promoted by Chamberlain's son Austen Chamberlain

Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain, KG was a British statesman, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and half-brother of Neville Chamberlain.- Early life and career :...

.

The Unionists strongly opposed many of the proposed reforms of the new Liberal governments of Campbell-Bannerman

Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman GCB was a British Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and Leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1908. He also served as Secretary of State for War twice, in the Cabinets of Gladstone and Rosebery...

and Asquith. In 1910, the Unionist-dominated House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

rejected the so-called "People's Budget

People's Budget

The 1909 People's Budget was a product of then British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith's Liberal government, introducing many unprecedented taxes on the wealthy and radical social welfare programmes to Britain's political life...

", leading to a long conflict over the nature and constitutional place of the House of Lords. The Conservatives managed to make up much of their losses in both the January and December elections of 1910. This forced the Liberals to rely on Irish Nationalist votes to maintain their majority. Although the Liberals were able to force through the effective subjugation of the Lords with the Parliament Act 1911

Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords which make up the Houses of Parliament. This Act must be construed as one with the Parliament Act 1949...

, their advocacy once again cost them support, so that by the time of the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

a Unionist victory in the next election looked possible. Liberal mismanagement of the early phases World War I led to the return of the Unionists to power: first in coalition with Asquith's Liberals, and then, with the split and collapse of the Liberals, the Unionists under Andrew Bonar Law were able to become the dominant party in Lloyd George's

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

coalition government following the 1918 election

United Kingdom general election, 1918

The United Kingdom general election of 1918 was the first to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918, which meant it was the first United Kingdom general election in which nearly all adult men and some women could vote. Polling was held on 14 December 1918, although the count did...

.

The Baldwin era

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, trade unions and the Irish issue (leading to the de facto independence for the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

in 1921 led to many Conservatives hoping to break with Lloyd George. Bonar Law resigned in 1921 on the grounds of ill health and the parliamentary party was now led by Austen Chamberlain

Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain, KG was a British statesman, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and half-brother of Neville Chamberlain.- Early life and career :...

. Previously a contender for party leadership in 1911, Chamberlain was to prove ineffective in controlling his party—even passing up the offer of becoming Prime Minister when Lloyd George indicated he was willing to step down. The party eventually broke free from Lloyd George in October 1922 as the result of a meeting of MPs at the Carlton Club

Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a gentlemen's club in London which describes itself as the "oldest, most elite, and most important of all Conservative clubs." Membership of the club is by nomination and election only.-History:...

. They voted against remaining in the coalition and Chamberlain resigned. He was actually replaced by Bonar Law, who had been persuaded by friends and allies to return to lead the party.

After winning the election of 1922

United Kingdom general election, 1922

The United Kingdom general election of 1922 was held on 15 November 1922. It was the first election held after most of the Irish counties left the United Kingdom to form the Irish Free State, and was won by Andrew Bonar Law's Conservatives, who gained an overall majority over Labour, led by John...

, Bonar Law, now terminally ill with throat cancer, was to resign for good from political life in May 1923. He died later that year. Though holding a majority in government, the party was still split, as many of those who stayed to the bitter end of the former coalition had refused to take office in Law's cabinet. Their absence explains why the hitherto unknown Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

was to become leader of the party barely two years after first entering a major ministerial post.

The party reached a new height in the inter-war years under Baldwin's leadership. His mixture of strong social reforms and steady government proved a powerful election combination, with the result that the Conservatives governed Britain either by themselves or as the leading component of the National Government

UK National Government

In the United Kingdom the term National Government is an abstract concept referring to a coalition of some or all major political parties. In a historical sense it usually refers primarily to the governments of Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain which held office from 1931...

for most of the interwar years and all through World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. The Conservatives under Baldwin were also the last political party in Britain to gain over 50% of the vote (in the general election of 1931

United Kingdom general election, 1931

The United Kingdom general election on Tuesday 27 October 1931 was the last in the United Kingdom not held on a Thursday. It was also the last election, and the only one under universal suffrage, where one party received an absolute majority of the votes cast.The 1931 general election was the...

). Yet at the conclusion of hostilities, the British public felt a different party would best guide them through the peace, and the Conservatives were soundly defeated in the 1945 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1945

The United Kingdom general election of 1945 was a general election held on 5 July 1945, with polls in some constituencies delayed until 12 July and in Nelson and Colne until 19 July, due to local wakes weeks. The results were counted and declared on 26 July, due in part to the time it took to...

by a resurgent Labour Party.

Post war recovery

The party responded to their defeat by accepting many of the LabourLabour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

government's social reforms whilst also offering a distinctive Conservative edge, as set out in their 1947 poicy statement Industrial Charter

Industrial Charter

The Industrial Charter: A Statement of Conservative Industrial Policy was a 1947 pamphlet and policy statement by the United Kingdom Conservative Party in which the party reconciled itself with the radical social changes introduced by the Labour Party government following the United Kingdom general...

. They returned to government in 1951

United Kingdom general election, 1951

The 1951 United Kingdom general election was held eighteen months after the 1950 general election, which the Labour Party had won with a slim majority of just five seats...

under Churchill. Churchill remained leader for another four years, during which time the Conservatives showed their acceptance of Labour reforms, though modifying some, such as the denationalisation the steel industry. In 1955 Churchill retired and was succeeded by Sir Anthony Eden

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, KG, MC, PC was a British Conservative politician, who was Prime Minister from 1955 to 1957...

. Eden had an immense personal popularity and lengthy experience as Foreign Secretary, but his government ran into a number of troubles on the domestic front as the economy began to overheat. In international affairs the government was confronted by the decision of the Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

ian government of Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein was the second President of Egypt from 1956 until his death. A colonel in the Egyptian army, Nasser led the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 along with Muhammad Naguib, the first president, which overthrew the monarchy of Egypt and Sudan, and heralded a new period of...

to nationalise the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

. Eden agreed to a secret collaboration with France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

to retake the Canal, but the resulting operation [see Suez Crisis

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also referred to as the Tripartite Aggression, Suez War was an offensive war fought by France, the United Kingdom, and Israel against Egypt beginning on 29 October 1956. Less than a day after Israel invaded Egypt, Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to Egypt and Israel,...

] backfired miserably and left the United Kingdom heavily embarrassed abroad and Eden discredited at home. With his health failing, Eden resigned at the beginning of 1957.

The succession was contentious, with Rab Butler

Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, KG CH DL PC , who invariably signed his name R. A. Butler and was familiarly known as Rab, was a British Conservative politician...

as the favourite to succeed. However, it was Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963....

who became the next Prime Minister and leader of the party. Macmillan sought to rebuild the government's image both at home and abroad, and presided over strong economic growth and a massive expansion in the consumer-product economy. In 1959 he won the general election of that year

United Kingdom general election, 1959

This United Kingdom general election was held on 8 October 1959. It marked a third successive victory for the ruling Conservative Party, led by Harold Macmillan...

on this economic success, summed up in the slogan "You've never had it so good." However, rising unemployment and an economic downturn in the early 1960s eroded support for Macmillan's government. It was further rocked in 1963 by the resignation of the Secretary of State for War John Profumo

John Profumo

Brigadier John Dennis Profumo, 5th Baron Profumo CBE , informally known as Jack Profumo , was a British politician. His title, 5th Baron, which he did not use, was Italian. Although Profumo held an increasingly responsible series of political posts in the 1950s, he is best known today for his...

over the Profumo Affair

Profumo Affair

The Profumo Affair was a 1963 British political scandal named after John Profumo, Secretary of State for War. His affair with Christine Keeler, the reputed mistress of an alleged Russian spy, followed by lying in the House of Commons when he was questioned about it, forced the resignation of...

. In October 1963 Macmillan was misdiagnosed with terminal cancer and resigned.

The party at this time lacked a formal process for electing a new leader and Macmillan's resignation took place in the week of the annual Conservative Party Conference. This event rapidly became an American-style convention as leading ministers sought to establish their credentials. Eventually Macmillan formally recommended to the Queen

Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

Elizabeth II is the constitutional monarch of 16 sovereign states known as the Commonwealth realms: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize,...

that she appoint the Earl of Home

Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel, KT, PC , known as The Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963 and as Sir Alec Douglas-Home from 1963 to 1974, was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1963 to October 1964.He is the last...

as Prime Minister. Home was appointed and renounced his peerage, becoming Sir Alec Douglas-Home, but was unable to restore the party's fortunes and narrowly lost the 1964 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1964

The United Kingdom general election of 1964 was held on 15 October 1964, more than five years after the preceding election, and thirteen years after the Conservative Party had retaken power...

.

The Heath years: 1965-1975

Conservative Party (UK) leadership election, 1965

The Conservative Party leadership election of July 1965 was held to find a successor to Sir Alec Douglas-Home.It was the first time that a formal election by the parliamentary party had taken place, previous leaders having emerged through a consultation process...

was won by Edward Heath

Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George "Ted" Heath, KG, MBE, PC was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and as Leader of the Conservative Party ....

over both Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling was a British politician who held several Cabinet posts, including Chancellor of the Exchequer. He had been spoken of as a prospective Conservative leader since 1955, and was twice seriously considered for the post; he was Edward Heath's chief rival in 1965...

and Enoch Powell

Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell, MBE was a British politician, classical scholar, poet, writer, and soldier. He served as a Conservative Party MP and Minister of Health . He attained most prominence in 1968, when he made the controversial Rivers of Blood speech in opposition to mass immigration from...

. The party proceeded to lose the 1966 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1966

The 1966 United Kingdom general election on 31 March 1966 was called by sitting Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Wilson's decision to call an election turned on the fact that his government, elected a mere 17 months previously in 1964 had an unworkably small majority of only 4 MPs...

. Heath's leadership proved controversial, with frequent calls from many prominent party members and supporters for him to step down, but he persevered. To the shock of almost everyone bar Heath, the party won the 1970 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1970

The United Kingdom general election of 1970 was held on 18 June 1970, and resulted in a surprise victory for the Conservative Party under leader Edward Heath, who defeated the Labour Party under Harold Wilson. The election also saw the Liberal Party and its new leader Jeremy Thorpe lose half their...

.

As with all British governments in this period, Heath's time in office was difficult. Furthermore, the Heath premiership remains one of the most controversial in the history of the party. Initial attempts to follow monetarist policies (later considered "Thatcherite") failed, with high inflation and unemployment blocking Heath's attempts at reforming the increasingly militant trade unions. The era of 1970s British industrial unrest had arrived.

The Troubles

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

in Northern Ireland would lead Heath to suspending the Parliament of Northern Ireland

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended...

and introducing direct rule

Direct Rule

Direct rule was the term given, during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, to the administration of Northern Ireland directly from Westminster, seat of United Kingdom government...

as a precursor to establishing a power-sharing executive under the Sunningdale Agreement

Sunningdale Agreement

The Sunningdale Agreement was an attempt to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive and a cross-border Council of Ireland. The Agreement was signed at the Civil Service College in Sunningdale Park located in Sunningdale, Berkshire, on 9 December 1973.Unionist opposition, violence and...

. This resulted in the Conservative Party losing the support of the Ulster Unionist Party

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party – sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party – is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland...

at Westminster, which was to have consequences in later years when the party found itself reliant on tiny Commons majorities. Heath himself considered his greatest success in office to be the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community (or the "Common Market" as it was widely called at the time) but in subsequent years the UK's membership of the EEC was to prove the source of the greatest division in the party.

The country suffered a further bout of inflation in 1973 as a result of the OPEC

OPEC

OPEC is an intergovernmental organization of twelve developing countries made up of Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela. OPEC has maintained its headquarters in Vienna since 1965, and hosts regular meetings...

cartel raising oil prices, and this in turn led to renewed demands for wage increases in the coal industry. The government refused to accede to the miner's demands, resulting in a series of stoppages and massive attempts to ration power, including the "Three Day Week". Heath decided to call a snap election on the question of "Who Governs Britain?". However the Conservative Party was unprepared, whilst the miners' unions stated that they did not see how the re-election of the government would change the situation. The Conservatives were further rocked by the death of Iain Macleod

Iain Macleod

Iain Norman Macleod was a British Conservative Party politician and government minister.-Early life:...

and the resignation of Enoch Powell

Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell, MBE was a British politician, classical scholar, poet, writer, and soldier. He served as a Conservative Party MP and Minister of Health . He attained most prominence in 1968, when he made the controversial Rivers of Blood speech in opposition to mass immigration from...

, who denounced the government for taking the country into the EEC and called on voters to back the Labour Party, who had promised a referendum

Referendum

A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal. This may result in the adoption of a new constitution, a constitutional amendment, a law, the recall of an elected official or simply a specific government policy. It is a form of...

on withdrawal. The February 1974 election

United Kingdom general election, February 1974

The United Kingdom's general election of February 1974 was held on the 28th of that month. It was the first of two United Kingdom general elections held that year, and the first election since the Second World War not to produce an overall majority in the House of Commons for the winning party,...

produced an unusual result as support for the Liberals, Scottish National Party

Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party is a social-democratic political party in Scotland which campaigns for Scottish independence from the United Kingdom....

and Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru

' is a political party in Wales. It advocates the establishment of an independent Welsh state within the European Union. was formed in 1925 and won its first seat in 1966...

all surged, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

's politics became more localised, whilst the Conservatives won a plurality of votes but Labour had a plurality of seats. With a hung Parliament

Hung parliament

In a two-party parliamentary system of government, a hung parliament occurs when neither major political party has an absolute majority of seats in the parliament . It is also less commonly known as a balanced parliament or a legislature under no overall control...

elected and the Ulster Unionists refusing to support the Conservative party, Heath tried to negotiate with the Liberals to form a coalition, but the attempts foundered on demands that were not acceptable to both parties. Heath was forced to resign as Prime Minister.

These years were seen as the height of "consensus politics". However, by the 1970s many traditional methods of running the economy, managing relations with trade unions, and so on began to fail—or had outright already failed. This was also a period of Labour-Party ascendancy, as they ruled for nearly twelve out of the fifteen years between 1964 and 1979. Many in the Conservative Party were left wondering how to proceed.

The Thatcher Years, 1975-1990

United Kingdom general election, October 1974

The United Kingdom general election of October 1974 took place on 10 October 1974 to elect 635 members to the British House of Commons. It was the second general election of that year and resulted in the Labour Party led by Harold Wilson, winning by a tiny majority of 3 seats.The election of...

a system was put in place and Heath agreed to holding a leadership election

Conservative Party (UK) leadership election, 1975

Edward Heath, leader of the Conservative Party and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom had called and unexpectedly lost the February 1974 general election...

to allow him to renew his mandate. Few both inside and out of the party expected him to be seriously challenged, let alone defeated. However Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

stood against Heath and in a shock result outpolled him on the first ballot, leading him to withdraw from the contest. Thatcher then faced off four other candidates to become the first woman to lead a major British political party. Thatcher had much support from the monetarists

Monetarism

Monetarism is a tendency in economic thought that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. It is the view within monetary economics that variation in the money supply has major influences on national output in the short run and the price level over...

, led by Keith Joseph

Keith Joseph

Keith St John Joseph, Baron Joseph, Bt, CH, PC , was a British barrister and politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet under three Prime Ministers , and is widely regarded to have been the "power behind the throne" in the creation of what came to be known as...

. The Conservatives capitalised on the Winter of Discontent

Winter of Discontent

The "Winter of Discontent" is an expression, popularised by the British media, referring to the winter of 1978–79 in the United Kingdom, during which there were widespread strikes by local authority trade unions demanding larger pay rises for their members, because the Labour government of...

and the growing inflation rate, not to mention the humiliating bailout of the UK economy by the IMF

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund is an organization of 187 countries, working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world...

in 1976, and won the 1979 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1979

The United Kingdom general election of 1979 was held on 3 May 1979 to elect 635 members to the British House of Commons. The Conservative Party, led by Margaret Thatcher ousted the incumbent Labour government of James Callaghan with a parliamentary majority of 43 seats...

with a majority of 43. Thatcher, thereby became the UK's first woman Prime Minister.