Military history of Uganda

Encyclopedia

The military history of Uganda begins with actions before the conquest of the country by the British Empire

. After the British conquered the country, there were various actions, including in 1887, and independence was granted in 1962. After independence, Uganda was plagued with a series of conflicts, most rooted in the problems caused by colonialism. Like many African nations, Uganda had to endure a series of Civil War

s and coups

. In recent years the Uganda People's Defence Force

has become involved in peacekeeping

operations for the African Union

and the United Nations

.

into a Bantu

south and Nilotic

north. The pastoralist

Nilotes of the north were organized by lineage into small clans. While cattle raiding was practiced extensively, the highly decentralized nature of northern societies precluded the possibility of large-scale warfare. By comparison, the introduction of plantain

as a staple crop in the south around 1000 AD permitted dense populations to form in the area north of Lake Victoria

. One of the early powerful states to emerge was Bunyoro

. However, chronic weakness within the structure of Bunyoro resulted in a continual series of civil war

s and royal succession disputes. According to legend, a refugee from a Bunyoro conflict, Kimera

, became Kabaka

of the contemporaneous kingdom of Buganda

, on the shores of Lake Victoria.

Bagandan governance was based on a stable succession arrangement, allowing the kingdom to more than double in size by the mid-nineteenth century through a series of wars of expansion, becoming the dominant power in the region. As well as a force of infantry, Baganda also maintained a navy of large outrigger canoes, which allowed Baganda commandos to raid any shore on Lake Victoria. Henry Morton Stanley

Bagandan governance was based on a stable succession arrangement, allowing the kingdom to more than double in size by the mid-nineteenth century through a series of wars of expansion, becoming the dominant power in the region. As well as a force of infantry, Baganda also maintained a navy of large outrigger canoes, which allowed Baganda commandos to raid any shore on Lake Victoria. Henry Morton Stanley

visited in 1875 and reported viewing a military expedition of 125,000 troops marching east, where they were to join an auxiliary naval force of 230 canoes.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Uganda began to lose its isolated status, mainly due to traders seeking new sources of ivory

after the decimation of elephant

herds along the coast. Arab traders from the coast began making trade agreements with the Kabaka of Uganda to provide guns and other items in exchange for a supply of ivory. In the north, Turkish Sudan under Khedive

Isma'il Pasha

sought to expand its control of the White Nile

. In 1869, the khedive sent a force under British explorer Samuel Baker

to establish dominion over the upper Nile. Encountering stiff resistance, Baker was forced to turn back after burning the Bunyoro capital to the ground.

Foreign influences led to the eventual disruption of royal rule in Buganda. In 1877, the London-based Church Missionary Society sent Protestant

Foreign influences led to the eventual disruption of royal rule in Buganda. In 1877, the London-based Church Missionary Society sent Protestant

missionaries, followed two years later by Catholic

France-based White Fathers

. The competition for converts in the royal court also included Zanzibar

-based Muslim

traders. When the new kabaka Mwanga II

attempted to outlaw the divisive foreign ideologies (see Uganda Martyrs), he was deposed by armed converts in 1888. A four-year civil erupted in which the Muslim forces initially declared victory, but were eventually defeated by an alliance of Christian groups. The conclusion of the civil war was also marked by various epidemics of foreign diseases, which halved the population in some localities and further weakened Baganda. The arrival of European colonial interests, in the persons of British captain Frederick Lugard

and German Karl Peters

, broke the Christian alliance. Protestant missionaries moved to put Uganda under British control, while French Catholics either supported the German claim or urged national independence. In 1892, fighting broke out between the two factions. Momentum remained with the Catholics until Lugard brought Maxim gun

s into play, resulting in the French Catholic mission being burnt to the ground and the Catholic bishop fleeing. With the support of Protestant Buganda chiefs secured, the British declared a protectorate in 1894 and began expanding its borders with the help of Nubia

n mercenaries formerly in the employ of the Egyptian khedive.

kingdom and chiefdoms of Busoga

signed treaties with the British, but the loosely-associated kinship groups of the east and northeast resisted until they were finally conquered. The general outline of the modern state of Uganda thus took shape.

However, in 1897 the Nubian mercenaries rebelled, resulting in a two-year conflict before they were put down with the help of units of the British Indian Army

, transported to Uganda at great cost. The protectorate rewarded Buganda for its support during these wars of expansion by giving it privileged status within the protectorate and awarding it most of the historic heartland of Bunyoro, including the locations of several royal tombs. The Baganda offered their expertise in administration to the colonial rulers, resulting in Ganda administrators running much of the country's affairs in the name of the protectorate. The Banyoro, aggrieved by both the "lost counties" and arrogance of Baganda administrators, rose up in the 1907 Nyangire "Refusing" rebellion, which succeeded in removing the irksome Baganda civil servants from Nyoro territory.

Despite these tensions, the protectorate was generally stable and prosperous, especially in comparison with Tanganyika

Despite these tensions, the protectorate was generally stable and prosperous, especially in comparison with Tanganyika

, which suffered greatly during the East African Campaign

of World War I. This began to change with the British decision to divest itself of its colonial properties and prepare Uganda for independence, embodied in the arrival of Andrew Cohen

in 1952 to assume the post of governor. Various groups began to organize themselves in preparation for planned elections, which was given urgency by the announcement that London was considering joining Kenya

, Uganda, and Tanganyika into an East African federation. Many politically aware Ugandans knew that the similar Central African Federation was dominated by white settlers and feared that an East Africa counterpart would be dominated by the racist settlers of the White Highlands

in Kenya, where the Mau Mau Uprising

was being bitterly fought. In the complete lack of popular confidence in his rule, Cohen was forced to agree to Buganda demands for a continued privileged status in the new constitution. The major dissenters were the Baganda Catholics, which had been marginalized since 1892 and were organized into the Democratic Party

(DP) of Benedicto Kiwanuka

, and the Uganda People's Congress

(UPC), a coalition of non-Baganda groups, determined not to be dictated to by the Baganda, led by Milton Obote

. After much political manoeuvering, Uganda entered independence in October 1962 under an alliance of convenience between the UPC and Kabaka Yekka

(KY), a Buganda separatist party, against the DP. The Kabaka was named ceremonial head of state, while Obote became prime minister.

and sent 300 Baganda veterans to Bunyoro to intimidate voters. In response, 3,000 Banyoro soldiers massed on the Bunyoro-Buganda border. Civil war was avoided when the kabaka backed down, allowing the referendum in which the populations of the "lost counties" overwhelmingly expressed a desire to return to the Bunyoro kingdom. In early 1966, Obote consolidated central power by stripping the monarchs of the five kingdoms of their titles and forced them into exile.

The UPC itself fell into disarray in 1966 after it was revealed that Obote and his associates, including Amin, were smuggling arms to a secessionist group in neighboring Congo

in return for ivory and gold. Faced with nearly unanimous disapproval, Obote did not take the expected step of stepping down as prime minister, but instead had Amin and the army carry out what was in effect a coup d'état

against his own government. After suspending the constitution, arresting dissident UPC ministers and taking the powers of the presidency for his own, he announced the promulgation of a new constitution abolishing the autonomy of the kingdoms guaranteed by the former federal system. When the Baganda protested, now-President Obote sent the army under Amin to attack the palace of the kabaka. The Battle of Mengo Hill

resulted in the palace being overrun, with the kabaka barely escaping into exile. With his opponents arrested, in flight, or co-opted, Obote secured his position with the creation of the General Service Unit, a system of secret police

staffed mostly with ethnic kinspeople from the Lango region. Nevertheless, Obote narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in December 1969, apparently carried out by Baganda monarchists.

In early 1970, the mysterious murder of Acap Okoya, the sole rival to Amin among the senior military officers, led Obote to grow suspicious of Amin. Later that year, Obote escaped another assassination attempt after the attackers mistakenly targeted the car of the vice-president. However, Obote could take no direct action as he was totally reliant upon the army that Amin led to keep him in power. In response, Obote increased the recruitment of ethnic Acholi and Langi

to counter the recruitment by Amin of soldiers from his home West Nile sub-region

. In October 1970, Obote put Amin under house arrest

on charges of increasing military expenditure over budget, as well as continuing to support Sudan

's Anyanya

rebel group in the civil war

against the government of Gaafar Nimeiry

, after Obote had decided to switch his support to Nimeiry. Amin was close friends with several Israel

i military advisors that were helping to train the army and there is much speculation that they had influenced him to continue supporting the Anyanya, which was also the recipient of Israeli military aid.

. The successful coup is often cited as an example of "action by the military", where the Ugandan Armed Forces acted against a government whose politics posed more of a threat to the military privileges. One of the priorities of the new president was mass executions of Acholi and Langi troops, which owed their loyalty to Obote. In July 1971, Lango and Acholi soldiers were massacred in the Jinja

and Mbarara

Barracks

, and by early 1972, some 5,000 Acholi and Lango soldiers had disappeared. Amin's rule was welcomed by the Baganda, but tens of thousands of Obote supporters fled south into Tanzania

. Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere

would prove to be a strong opponent of the Amin government, an attitude mirrored by Kenya

, South Africa and the Organisation for African Unity, though Israel

, Great Britain and the United States were quick to recognize the legitimacy of the Amin government.

While the military had grown under Obote, it multiplied in size under Amin, who characterized the government in military terms. He renamed Government House "the Command Post", placed military tribunal

s over civil courts, appointed military commanders to head civilian ministries and parastatals, and informed civilian cabinet ministers that they were subject to military law

. The commanders of barracks located around the country became the de facto rulers of their regions. Despite the characterization of the country in terms of a military command structure, the administration was far from well-organized. Amin, like many of the officers he appointed to senior positions, was illiterate, and thus gave instructions orally, in person, by telephone or in long rambling speeches.

The regime was subject to deadly internal rivalries. One area of competition was a rivalry between British-trained officers and Israeli-trained officers, who both opposed the many untrained officers, resulting in many trained officers being purged. The purges also had the effect of creating promotion opportunities; commander of the air force Smuts Guweddeko began as a telephone operator. Another contest was religious in nature. In order to gain supplies from Libya

, in early 1972 Amin expelled the Israeli advisers, who had helped put him in power, and became virulently anti-Zionist

. To gain the favor of Saudi Arabia

he embraced his Islamic heritage, raising hopes among Ugandan Muslims

that their defeat in 1892 would be redressed. Amin deployed soldiers to aid Egypt and provided financial support to the Arab nations during the Yom Kippur War

. When Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations

and German Revolutionary Cells (RZ)

terrorists hijacked a plane in 1976 and landed it at Entebbe International Airport

, Israeli commandos

carried out a raid

that successfully freed most of the hostages. Criticism by the Church of Uganda

of army abuses would lead to the murder of Archbishop Janani Luwum

.

With his reputation with Western nations in tatters after the hijacking, Amin began to purchase weapons from the Soviet Union. As his regime neared its end, Amin became increasingly eccentric and bellicose. In 1978 he conferred the decoration Conqueror of the British Empire upon himself. The government all but ceased to function as the constant purges of senior ranks by the increasingly paranoid Amin caused officials to refrain from making any decisions for fear of making the 'wrong' one.

, but stopped short and instead waited in expectation of a popular uprising to overthrow Amin. The uprising did not materialize and the Obote-aligned force was expelled by the Malire Mechanical Regiment. The event prompted Amin to task the General Service Unit, now renamed the Special Research Bureau, and the newly-formed Public Safety Unit with an intensified search for suspected subversives. Thousands of people were disappeared

. Amin also retaliated by further purging the army of Obote supporters, predominantly those from the Acholi and Lango

ethnic groups.

The political environment became increasingly unstable and paranoia-inducing as the regime continued and Amin's circle of supporters grew smaller and smaller due the purges and disappearances. In 1978, General Mustafa Adrisi

, an Amin supporter, was injured in a suspicious automobile accident and units loyal to him, including the once-loyal Malire Mechanized Regiment, mutinied. Amin sent loyalist units to crush the uprising, causing some of the mutineers to flee south into Tanzania. Amin, seeking to deflect blame and rally the populace, then accused Tanzania's Nyerere of being the cause of the fighting and sent troops across the border to formally annex 700 miles of Tanzania known as the Kagera Salient on 1 November 1978. In response, Nyerere declared a state of war

and mobilized the Tanzania People's Defence Force

for a full-scale conflict. Within several weeks, the Tanzanian army was expanded from 40,000 to over 100,000 with the addition of police, prison guards, militia and others. They were joined by the various anti-Amin forces, who in March 1979 coalesced into the Uganda National Liberation Front

(UNLF). The UNLF was composed of the Obote-led Kikosi Maalum

and the Front for National Salvation

, led by political newcomer Yoweri Museveni

, as well as several smaller anti-Amin groups.

The Tanzanian army, with the support of the UNLF, drove the Ugandan forces out of Tanzania and began an invasion of Uganda. The Ugandan army offered little resistance and retreated steadily, spending much of its energies looting the countryside. Libya's Muammar al-Gaddafi sent 3,000 troops to support the Ugandan defense, but these troops found themselves fighting on the front lines, as Ugandan units in the rear commandeered their supply trucks to carry their plunder away. On 11 April 1979, Kampala fell

to the invaders and Amin fled into exile, marking the first time in the post-colonial era that an African nation successfully invaded another.

was replaced by Godfrey Binaisa

, a former minister in the UPC. While the UNLF force that helped overthrow Amin numbered only 1000, in 1979, Museveni and David Oyite-Ojok

, a Langi like Obote, began a massive recruitment of soldiers into what were in-effect their personal armies. When Binaisa attempted to stop this rapid military expansion, he was deposed by Museveni, Oyite-Ojok and Obote-stalwart Paulo Muwanga

. After Muwanga's rise to power, Obote returned to the country to stand in elections. In an intensely contested and highly compromised election held on December 10, 1980, Obote was re-elected president with Muwanga as his vice-president. In response, Museveni declared armed opposition to Obote's UNLF government. In 1980, Museveni merged his Popular Resistance Army

(PRA) with Lule's Uganda Freedom Fighters

, forming the National Resistance Army

(NRA). As well as the NRA, two rebel groups based in Amin's home West Nile sub-region

emerged: the Uganda National Rescue Front

and the Former Uganda National Army.

The beginning of the Ugandan Bush War

was marked by an NRA attack in the central Mubende District

on 6 February 1981. The NRA insurgency was based largely in the anti-Obote strongholds of central and western Buganda and the former kingdoms of Ankole and Bunyoro. Fighting was particularly intense in the Luwero triangle

of Buganda, where the bitter memory of the counterinsurgency efforts of the UNLF's Langi and Acholi soldiers against the populace would prove an enduring legacy. The NRA was highly organized, forming Resistance Councils

in areas they controlled to funnel recruits and supplies into the war effort. In comparison, the inability of the UNLF government to defeat the rebels both in the west and West Nile proved devastating to the unity of the government, while the brutality of the counter-insurgency further inflamed anti-Obote sentiment in the occupied areas. Following the death of General Oyite-Ojok in a helicopter crash at the end of 1983, the Acholi-Langi alliance began to fracture. On 27 January 1985, Acholi troops under Brigadier Bazilio Olara-Okello

staged a successful coup and put fellow Acholi General Tito Okello

into the presidency as Obote once again fled into exile, this time for good. The Okello government had little policy besides self-preservation. After an Okello-Museveni peace agreement

broke down, the NRA began a final offensive and entered Kampala in January 1986 as the Acholi troops fled north to their homeland. Yoweri Museveni declared the presidency on January 29, 1986. Estimates for the death toll for the 1981-5 period, which includes the Bush War, conflict in West Nile and internecine UNLF purges and fighting, range as high as 500,000.

The new NRA government's occupation of the north was challenged by rebel groups formed among the former supporters of Obote. The Acholi coalesced into the Uganda People's Democratic Army

The new NRA government's occupation of the north was challenged by rebel groups formed among the former supporters of Obote. The Acholi coalesced into the Uganda People's Democratic Army

(UPDA), largely composed of former army soldiers, in 1986 while a series of perceived outrages prompted the formation the following year of the similarly comprised Uganda People's Army

(UPA) by the Iteso

, who were closely allied with the Langi. Both the Acholi and Iteso were subject to a devastating series of cattle raids

by Karamojong

along their western border, which resulted in loss of much of the region's wealth.

The UPA rebellion reached a height of intensity in the late 1980s, before a settlement was negotiated in 1992. The UPDA rebellion also soon faltered and resulted in a peace accord in 1988. However, the situation in Acholiland was compounded after spirit medium Alice Auma

declared divinely-inspired leadership of a Holy Spirit Movement

to retake the capital and initiate a heaven on earth. While Auma's force was defeated in the forests near Kampala in August 1987, its relative success inspired Joseph Kony

, also a self-proclaimed spirit medium, to form a new group that would come to be known as the Lord's Resistance Army

(LRA).

One of Africa's longest-running military conflicts, the hostilities between the Ugandan military, renamed the Uganda People's Defence Force

(UPDF) following the promulgation of the new 1995 uganda constitution, and the insurgent LRA have been ongoing since 1987. In September 2006 a ceasefire was declared after peace talks. The LRA is accused of widespread human rights violations, including mutilation

, torture

, rape

, the abduction

of civilians, the use of child soldiers and a number of massacres. Operating in a vast swathe of northern Uganda, southern Sudan and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo

(DRC), the LRA has, at various times, caused the displacement of the majority of civilians in its areas of operations with the support of militias allied with the Sudanese government in its own civil war

.

The situation in West Nile, located in the northwestern corner of the country, also remained fluid. While many members of the Uganda National Rescue Front, formed by Amin supporters to oppose Obote, were integrated into the new NRA military, some joined the West Nile Bank Front

The situation in West Nile, located in the northwestern corner of the country, also remained fluid. While many members of the Uganda National Rescue Front, formed by Amin supporters to oppose Obote, were integrated into the new NRA military, some joined the West Nile Bank Front

(WNBF), formed by Juma Oris

in 1986 to oppose the NRA government. The WNBF was, like the LRA, highly active along the porous Uganda-Sudan border until a counterinsurgency operation focused on civil-military cooperation was initiated by Major General Katumba Wamala

in 1996, which, coupled with Ugandan-backed Sudan People's Liberation Army

attacks upon the WNBF's rear areas in Sudan, resulted in the WNBF dwindling into obscurity by 1998. However, some rebels instead formed the Uganda National Rescue Front II, which operated with Sudanese support in Aringa County, Arua District

, until it signed a formal ceasefire in 2002.

(ADF), a rebel group formed in 1996 by puritanical Muslim Ugandans of the Tablighi Jamaat

sect after a merger with the remnants of the rebel National Army for the Liberation of Uganda. The ADF based themselves in the Ruwenzori Range

along Uganda's western border with the DRC and by 1998 had carried out attacks on civilians that resulted in tens of thousands of internally displaced persons, as well as thrown bomb attacks on restaurants and markets in Kampala and other towns. By 1999, military pressure by the UPDF forced the ADF into small uncoordinated bands. In December 2005, the Congolese government and United Nations mission

carried out a military operation

to finally destroy ADF bases in the DRC's Ituri Province.

n refugees located in the southwest of the country; of the 27 original members of the NRA, two were Tutsi

refugees: Fred Rwigema

and Paul Kagame

. Tutsi refugees formed a disproportionately large number of officers in the NRA for the simple reason that they joined early and had accumulated more experience. After his 1986 victory, Museveni rewarded their long service by appointing Rwigema to the second-highest military post and Kagame to the post of acting head of military intelligence. Many Tutsi veterans were also members of the Rwandan Patriotic Front

(RPF), which was initially created as an intellectual forum. However, a nativist backlash resulted in the refugees feeling increasingly unwelcome. On 1 October 1990, the RPF invaded Rwanda, stating that they were fighting for a just government and the right to return, thus beginning the Rwandan Civil War

. With the initial offensive repulsed, the RPF retrenched for a long guerrilla struggle. Museveni would later tacitly admit that he had not been consulted prior to the invasion but, faced with the choice of offering aid and sanctuary to his old comrades in the RPF or watching them defeated along Uganda's southern burden, chose to offer assistance. Roméo Dallaire

, the head of United Nations Observer Mission Uganda-Rwanda

(1993–1994), would later complain of the substantial restrictions the Ugandan government put on his efforts to discover military supplies surreptitiously transported to RPF-held areas in northern Rwanda.

The start of the Rwandan Genocide

in April 1994 reignited the civil war between the RPF and Rwandan government. The victory of the RPF in August 1994 prompted a massive outflow of refugees

into neighboring countries, in particular Zaire

. Zairean president Mobutu Sese Seko

had been a strong supporter of the Hutu

government of Rwanda, as well as having given Obote military aid in the Ugandan Bush War, and the refugee camps in Zaire quickly became militarized by Hutu insurgents and ex-Rwandan Armed Forces. In 1996, Rwanda sponsored the rebel Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Zaire

(AFDL), led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila

, with the support of Uganda. The first task of the AFDL was to break up the large refugee camps, after which it marched to Kinshasa

, overthrew Mobutu and put Kabila into the presidency in 1997. Kabila renamed the country the "Democratic Republic of the Congo

" (DRC). (See First Congo War

.)

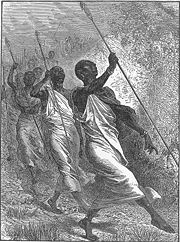

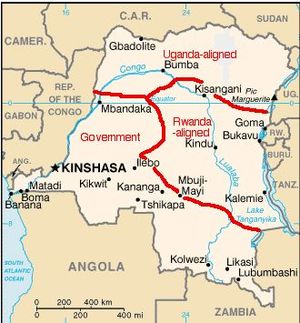

Kabila attempted to sever his connections with his Rwandan backers in 1998, resulting in the deadliest conflict

Kabila attempted to sever his connections with his Rwandan backers in 1998, resulting in the deadliest conflict

since World War II, which drew in eight nations and many more armed groups. Museveni apparently persuaded an initially reluctant High Command to go along with the venture. "We felt that the Rwandese started the war and it was their duty to go ahead and finish the job, but our President took time and convinced us that we had a stake in what is going on in Congo", one senior officer is reported as saying. The official reasons Uganda gave for the intervention were to stop a "genocide

" against the Banyamulenge

in DRC in concert with Rwandan forces, and that Kabila had failed to provide security along the border and was allowing the ADF to attack Uganda from rear bases in the DRC. In reality, the UPDF were not deployed in the border region but more than 1,000 kilometres (over 600 miles) to the west of Uganda's frontier with Congo in support of the Movement for the Liberation of Congo

(MLC), a Uganda-backed group formed in September 1998. The lack of Ugandan security forces in the border region allowed the ADF to successfully attack Fort Portal

, a large western town, and capture a prison.

The war ended in 2003 with the removal of foreign troops and the country's first election.

Similar to many other African nations involved, the war has created several problems for Uganda

. In 2000 the United States Military suspended the UPDF cooperation in the African Crisis Response Initiative until 2003. Several officers in the Ugandan Army have came under attack for their actions during the war.

The Ituri Conflict

is an ongoing conflict between Lendu

and Hema

ethnic groups in the Ituri region. Led by General James Kazini

of the Ugandan Army it was a joint operations between the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo

peacekeeping

force and DRC forces against the Nationalist and Integrationist Front

.

and Eritrea

were identified as linchpins in containing

Sudan. These states were provided "defensive, nonlethal military assistance" against Sudan-backed insurgencies and Sudanese sponsorship of international terrorism

.

has been active in many international peacekeeping missions with both the African Union

and the United Nations

. It has provided troops to many African Union

Peacekeeping

missions along with providing civilian police for the United Nations

Peacekeeping missions.

The African Union Mission in Sudan

The African Union Mission in Sudan

was . Uganda was among the many African nations that have deployed troops as part of the African Union Mission in Sudan

, established in 2004 to provide for security and peacekeeping in the Darfur

region. This has helped raise the number of troops from 150 up to 3,300. The African Union Mission to Somalia was . The current leader of the African Union Mission to Somalia, established on January 19, 2007 to provide security and peacekeeping in the region during the Somalian Civil War

, is General Levi Karuhanga

from Uganda. Uganda has currently deployed 15,000 troops in the region.

The United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea

was established in 2000 to monitor the ceasefire that ended the border war

between Ethiopia

and Eritrea

. The mission has remained in place in order to formally mark the border between the two countries. Uganda has deployed military troops to assist in the peacekeeping

. The United Nations Mission in Sudan

was established in 2005 to monitor the Comprehensive Peace Agreement

that ended the Second Sudanese Civil War

. Currently there are 15,000 military troops and 715 civilian police

. Uganda

has currently deployed police as part of the peacekeeping force.

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. After the British conquered the country, there were various actions, including in 1887, and independence was granted in 1962. After independence, Uganda was plagued with a series of conflicts, most rooted in the problems caused by colonialism. Like many African nations, Uganda had to endure a series of Civil War

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

s and coups

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

. In recent years the Uganda People's Defence Force

Uganda People's Defence Force

The Uganda Peoples Defence Force , previously the National Resistance Army, is the armed forces of Uganda. The International Institute for Strategic Studies estimates the UPDF has a total strength of 40–45,000, and consists of land forces and an Air Wing.The IISS Military Balance 2007 says there...

has become involved in peacekeeping

Peacekeeping

Peacekeeping is an activity that aims to create the conditions for lasting peace. It is distinguished from both peacebuilding and peacemaking....

operations for the African Union

African Union

The African Union is a union consisting of 54 African states. The only all-African state not in the AU is Morocco. Established on 9 July 2002, the AU was formed as a successor to the Organisation of African Unity...

and the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

.

Pre-colonial Uganda

The region now known as Uganda is divided linguistically by Lake KyogaLake Kyoga

Lake Kyoga is a large shallow lake complex of Uganda, about in area and at an elevation of 914 m. The Victoria Nile flows through the lake on its way from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert. The main inflow from Lake Victoria is regulated by the Nalubaale Power Station in Jinja. Another source of water...

into a Bantu

Bantu languages

The Bantu languages constitute a traditional sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages. There are about 250 Bantu languages by the criterion of mutual intelligibility, though the distinction between language and dialect is often unclear, and Ethnologue counts 535 languages...

south and Nilotic

Nilotic

Nilotic people or Nilotes, in its contemporary usage, refers to some ethnic groups mainly in South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and northern Tanzania, who speak Nilotic languages, a large sub-group of the Nilo-Saharan languages...

north. The pastoralist

Pastoralism

Pastoralism or pastoral farming is the branch of agriculture concerned with the raising of livestock. It is animal husbandry: the care, tending and use of animals such as camels, goats, cattle, yaks, llamas, and sheep. It may have a mobile aspect, moving the herds in search of fresh pasture and...

Nilotes of the north were organized by lineage into small clans. While cattle raiding was practiced extensively, the highly decentralized nature of northern societies precluded the possibility of large-scale warfare. By comparison, the introduction of plantain

Plantain

Plantain is the common name for herbaceous plants of the genus Musa. The fruit they produce is generally used for cooking, in contrast to the soft, sweet banana...

as a staple crop in the south around 1000 AD permitted dense populations to form in the area north of Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. The lake was named for Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, by John Hanning Speke, the first European to discover this lake....

. One of the early powerful states to emerge was Bunyoro

Bunyoro

Bunyoro is a kingdom in Western Uganda. It was one of the most powerful kingdoms in East Africa from the 16th to the 19th century. It is ruled by the Omukama of Bunyoro...

. However, chronic weakness within the structure of Bunyoro resulted in a continual series of civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

s and royal succession disputes. According to legend, a refugee from a Bunyoro conflict, Kimera

Kimera of Buganda

Kimera Walusimbi was Kabaka of the Kingdom of Buganda between 1374 and 1404. He was the third king of Buganda.-Claim to the throne:Kimera was the only son of Prince Kalemeera, the son of Kabaka Chwa Nabakka. His mother was Lady Wannyana, the supposed chief wife of King Winyi of Bunyoro...

, became Kabaka

Kabaka of Buganda

Kabaka is the title of the king of the Kingdom of Buganda. According to the traditions of the Baganda they are ruled by two kings, one spiritual and the other material....

of the contemporaneous kingdom of Buganda

Buganda

Buganda is a subnational kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Ganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day Uganda, comprising all of Uganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala, with the exception of the disputed eastern Kayunga District...

, on the shores of Lake Victoria.

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley, GCB, born John Rowlands , was a Welsh journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of Africa and his search for David Livingstone. Upon finding Livingstone, Stanley allegedly uttered the now-famous greeting, "Dr...

visited in 1875 and reported viewing a military expedition of 125,000 troops marching east, where they were to join an auxiliary naval force of 230 canoes.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Uganda began to lose its isolated status, mainly due to traders seeking new sources of ivory

Ivory

Ivory is a term for dentine, which constitutes the bulk of the teeth and tusks of animals, when used as a material for art or manufacturing. Ivory has been important since ancient times for making a range of items, from ivory carvings to false teeth, fans, dominoes, joint tubes, piano keys and...

after the decimation of elephant

Elephant

Elephants are large land mammals in two extant genera of the family Elephantidae: Elephas and Loxodonta, with the third genus Mammuthus extinct...

herds along the coast. Arab traders from the coast began making trade agreements with the Kabaka of Uganda to provide guns and other items in exchange for a supply of ivory. In the north, Turkish Sudan under Khedive

Khedive

The term Khedive is a title largely equivalent to the English word viceroy. It was first used, without official recognition, by Muhammad Ali Pasha , the Wāli of Egypt and Sudan, and vassal of the Ottoman Empire...

Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha , known as Ismail the Magnificent , was the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of the United Kingdom...

sought to expand its control of the White Nile

White Nile

The White Nile is a river of Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile from Egypt, the other being the Blue Nile. In the strict meaning, "White Nile" refers to the river formed at Lake No at the confluence of the Bahr al Jabal and Bahr el Ghazal rivers...

. In 1869, the khedive sent a force under British explorer Samuel Baker

Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker, KCB, FRS, FRGS was a British explorer, officer, naturalist, big game hunter, engineer, writer and abolitionist. He also held the titles of Pasha and Major-General in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. He served as the Governor-General of the Equatorial Nile Basin between Apr....

to establish dominion over the upper Nile. Encountering stiff resistance, Baker was forced to turn back after burning the Bunyoro capital to the ground.

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

missionaries, followed two years later by Catholic

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

France-based White Fathers

White Fathers

The missionary society known as "White Fathers" , after their dress, is a Roman Catholic Society of Apostolic Life founded in 1868 by the first Archbishop of Algiers, later Cardinal Lavigerie, as the Missionaries of Our Lady of Africa of Algeria, and is also now known as the Society of the...

. The competition for converts in the royal court also included Zanzibar

Zanzibar

Zanzibar ,Persian: زنگبار, from suffix bār: "coast" and Zangi: "bruin" ; is a semi-autonomous part of Tanzania, in East Africa. It comprises the Zanzibar Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of numerous small islands and two large ones: Unguja , and Pemba...

-based Muslim

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

traders. When the new kabaka Mwanga II

Mwanga II of Buganda

Danieri Basammula-Ekkere Mwanga II Mukasa was Kabaka from 1884 until 1888 and from 1889 until 1897. He was the thirty-first Kabaka of Buganda.-Claim to the throne:...

attempted to outlaw the divisive foreign ideologies (see Uganda Martyrs), he was deposed by armed converts in 1888. A four-year civil erupted in which the Muslim forces initially declared victory, but were eventually defeated by an alliance of Christian groups. The conclusion of the civil war was also marked by various epidemics of foreign diseases, which halved the population in some localities and further weakened Baganda. The arrival of European colonial interests, in the persons of British captain Frederick Lugard

Frederick Lugard

Frederick John Dealtry Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard GCMG, CB, DSO, PC , known as Sir Frederick Lugard between 1901 and 1928, was a British soldier, mercenary, explorer of Africa and colonial administrator, who was Governor of Hong Kong and Governor-General of Nigeria .-Early life and education:Lugard...

and German Karl Peters

Karl Peters

Karl Peters , was a German colonial ruler, explorer, politician and author, the prime mover behind the foundation of the German colony of East Africa...

, broke the Christian alliance. Protestant missionaries moved to put Uganda under British control, while French Catholics either supported the German claim or urged national independence. In 1892, fighting broke out between the two factions. Momentum remained with the Catholics until Lugard brought Maxim gun

Maxim gun

The Maxim gun was the first self-powered machine gun, invented by the American-born British inventor Sir Hiram Maxim in 1884. It has been called "the weapon most associated with [British] imperial conquest".-Functionality:...

s into play, resulting in the French Catholic mission being burnt to the ground and the Catholic bishop fleeing. With the support of Protestant Buganda chiefs secured, the British declared a protectorate in 1894 and began expanding its borders with the help of Nubia

Nubia

Nubia is a region along the Nile river, which is located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.There were a number of small Nubian kingdoms throughout the Middle Ages, the last of which collapsed in 1504, when Nubia became divided between Egypt and the Sennar sultanate resulting in the Arabization...

n mercenaries formerly in the employ of the Egyptian khedive.

Colonial period (1894-1962)

In spite of the British declaration, actually taking control of the region was a prolonged affair. The British and their Buganda ally engaged in a bloody five-year conflict with Bunyoro, which boasted several regiments of rifle infantry under the firm rule of Kabarega. After defeating and occupying the Bunyoro, the British forces defeated the Acholi and other people of the north. Elsewhere, the AnkoleAnkole

Ankole, also referred to as Nkore, is one of four traditional kingdoms in Uganda. The kingdom is located in the southwestern Uganda, east of Lake Edward. It was ruled by a monarch known as The Mugabe or Omugabe of Ankole. The kingdom was formally abolished in 1967 by the government of President...

kingdom and chiefdoms of Busoga

Busoga

Busoga is a traditional Bantu kingdom in present-day Uganda.It is a cultural institution that promotes popular participation and unity among the people of Busoga, through cultural and developmental programs for the improved livelihood of the people of Busoga. It strives for a united people of...

signed treaties with the British, but the loosely-associated kinship groups of the east and northeast resisted until they were finally conquered. The general outline of the modern state of Uganda thus took shape.

However, in 1897 the Nubian mercenaries rebelled, resulting in a two-year conflict before they were put down with the help of units of the British Indian Army

British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, officially simply the Indian Army, was the principal army of the British Raj in India before the partition of India in 1947...

, transported to Uganda at great cost. The protectorate rewarded Buganda for its support during these wars of expansion by giving it privileged status within the protectorate and awarding it most of the historic heartland of Bunyoro, including the locations of several royal tombs. The Baganda offered their expertise in administration to the colonial rulers, resulting in Ganda administrators running much of the country's affairs in the name of the protectorate. The Banyoro, aggrieved by both the "lost counties" and arrogance of Baganda administrators, rose up in the 1907 Nyangire "Refusing" rebellion, which succeeded in removing the irksome Baganda civil servants from Nyoro territory.

Tanganyika

Tanganyika , later formally the Republic of Tanganyika, was a sovereign state in East Africa from 1961 to 1964. It was situated between the Indian Ocean and the African Great Lakes of Lake Victoria, Lake Malawi and Lake Tanganyika...

, which suffered greatly during the East African Campaign

East African Campaign (World War I)

The East African Campaign was a series of battles and guerrilla actions which started in German East Africa and ultimately affected portions of Mozambique, Northern Rhodesia, British East Africa, Uganda, and the Belgian Congo. The campaign was effectively ended in November 1917...

of World War I. This began to change with the British decision to divest itself of its colonial properties and prepare Uganda for independence, embodied in the arrival of Andrew Cohen

Andrew Cohen (statesman)

Sir Andrew Benjamin Cohen KCMG KCVO OBE was Governor of Uganda from 1952 to 1957.- Early life and education :...

in 1952 to assume the post of governor. Various groups began to organize themselves in preparation for planned elections, which was given urgency by the announcement that London was considering joining Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

, Uganda, and Tanganyika into an East African federation. Many politically aware Ugandans knew that the similar Central African Federation was dominated by white settlers and feared that an East Africa counterpart would be dominated by the racist settlers of the White Highlands

White Highlands

The term White Highlands describes an area in the central uplands of Kenya, so-called because, during the period of British Colonialism, white immigrants settled there in considerable numbers. The main motivation was to take advantage of the good soils and growing conditions, as well as the cool...

in Kenya, where the Mau Mau Uprising

Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau Uprising was a military conflict that took place in Kenya between 1952 and 1960...

was being bitterly fought. In the complete lack of popular confidence in his rule, Cohen was forced to agree to Buganda demands for a continued privileged status in the new constitution. The major dissenters were the Baganda Catholics, which had been marginalized since 1892 and were organized into the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (Uganda)

The Democratic Party is a moderate conservative political party in Uganda currently led by Norbert Mao. DP was led by Paul Ssemogerere for 25 years until his retirement in November 2005...

(DP) of Benedicto Kiwanuka

Benedicto Kiwanuka

Benedicto Kabimu Mugumba Kiwanuka was the first Prime Minister of Uganda, leader of the Democratic Party and one of the early leaders that led the country in the transition between colonial British rule and independence...

, and the Uganda People's Congress

Uganda People's Congress

The Uganda People's Congress is a political party in Uganda.Uganda People's Congress was founded in 1960 by Milton Obote, who led the country to Independence and later served two presidential terms under the party's banner...

(UPC), a coalition of non-Baganda groups, determined not to be dictated to by the Baganda, led by Milton Obote

Milton Obote

Apolo Milton Obote , Prime Minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and President of Uganda from 1966 to 1971, then again from 1980 to 1985. He was a Ugandan political leader who led Uganda towards independence from the British colonial administration in 1962.He was overthrown by Idi Amin in 1971, but...

. After much political manoeuvering, Uganda entered independence in October 1962 under an alliance of convenience between the UPC and Kabaka Yekka

Kabaka Yekka

Kabaka Yekka was a monarchist political party in Uganda. The party's name means 'king only' in the Ganda language language, Kabaka being the title of the King of the kingdom of Buganda....

(KY), a Buganda separatist party, against the DP. The Kabaka was named ceremonial head of state, while Obote became prime minister.

Early independent Uganda (1963-1970)

In January 1964, several army units rebelled, demanding higher pay and more rapid promotion. Obote was forced to request the assistance of the British military in putting down the revolt, but ultimately caved in to all of the demands. The obvious lack of civilian control of the military resulted in the rapid expansion of the army and its resulting importance in political affairs. Obote also chose a young army officer, Idi Amin Dada, as his personal protege. Later that year, Obote made a deal with several DP ministers in which they would cross the floor to join the UPC if Obote could return the "lost counties". The kabaka opposed the planned referendumReferendum

A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal. This may result in the adoption of a new constitution, a constitutional amendment, a law, the recall of an elected official or simply a specific government policy. It is a form of...

and sent 300 Baganda veterans to Bunyoro to intimidate voters. In response, 3,000 Banyoro soldiers massed on the Bunyoro-Buganda border. Civil war was avoided when the kabaka backed down, allowing the referendum in which the populations of the "lost counties" overwhelmingly expressed a desire to return to the Bunyoro kingdom. In early 1966, Obote consolidated central power by stripping the monarchs of the five kingdoms of their titles and forced them into exile.

The UPC itself fell into disarray in 1966 after it was revealed that Obote and his associates, including Amin, were smuggling arms to a secessionist group in neighboring Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a state located in Central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa by area and the eleventh largest in the world...

in return for ivory and gold. Faced with nearly unanimous disapproval, Obote did not take the expected step of stepping down as prime minister, but instead had Amin and the army carry out what was in effect a coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

against his own government. After suspending the constitution, arresting dissident UPC ministers and taking the powers of the presidency for his own, he announced the promulgation of a new constitution abolishing the autonomy of the kingdoms guaranteed by the former federal system. When the Baganda protested, now-President Obote sent the army under Amin to attack the palace of the kabaka. The Battle of Mengo Hill

Battle of Mengo Hill

The Battle of Mengo Hill refers to the successful 1966 assault upon the residence of the Kabaka of Buganda by the army of Uganda.In February 1966, Prime Minister Milton Obote had changed the constitution, taking the powers of the presidency, formerly held by the Kabaka, for himself...

resulted in the palace being overrun, with the kabaka barely escaping into exile. With his opponents arrested, in flight, or co-opted, Obote secured his position with the creation of the General Service Unit, a system of secret police

Secret police

Secret police are a police agency which operates in secrecy and beyond the law to protect the political power of an individual dictator or an authoritarian political regime....

staffed mostly with ethnic kinspeople from the Lango region. Nevertheless, Obote narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in December 1969, apparently carried out by Baganda monarchists.

In early 1970, the mysterious murder of Acap Okoya, the sole rival to Amin among the senior military officers, led Obote to grow suspicious of Amin. Later that year, Obote escaped another assassination attempt after the attackers mistakenly targeted the car of the vice-president. However, Obote could take no direct action as he was totally reliant upon the army that Amin led to keep him in power. In response, Obote increased the recruitment of ethnic Acholi and Langi

Langi

Langi may refer to:*Ləngi, Azerbaijan*Langi people, a people of Uganda* Langi , Tongan burial structures for kings...

to counter the recruitment by Amin of soldiers from his home West Nile sub-region

West Nile sub-region

West Nile sub-region is a region in north-western Uganda that consists of the districts of Adjumani, Arua, Koboko, Maracha-Terego, Moyo, Nebbi and Yumbe...

. In October 1970, Obote put Amin under house arrest

House arrest

In justice and law, house arrest is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to his or her residence. Travel is usually restricted, if allowed at all...

on charges of increasing military expenditure over budget, as well as continuing to support Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

's Anyanya

Anyanya

The Anyanya were a southern Sudanese separatist rebel army formed during the First Sudanese Civil War . A separate movement that rose during the Second Sudanese Civil War were, in turn, called Anyanya II...

rebel group in the civil war

First Sudanese Civil War

The First Sudanese Civil War was a conflict from 1955 to 1972 between the northern part of Sudan and the southern Sudan region that demanded representation and more regional autonomy...

against the government of Gaafar Nimeiry

Gaafar Nimeiry

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry was the Nubian President of Sudan from 1969 to 1985...

, after Obote had decided to switch his support to Nimeiry. Amin was close friends with several Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

i military advisors that were helping to train the army and there is much speculation that they had influenced him to continue supporting the Anyanya, which was also the recipient of Israeli military aid.

Under Idi Amin (1971-1979)

Despite protestations by Amin that he remained loyal, Obote decided to rid himself of the perceived threat in January 1971. While leaving on a foreign trip, Obote ordered Langi military officers to arrest Amin and his close supporters. However, word of the plot was leaked to Amin before it could be carried out, prompting Amin to carry out a pre-emptive coup1971 Ugandan coup d'état

The 1971 Ugandan coup d'état was a military coup d'état executed by the Ugandan military, led by General Idi Amin, against the government of President Milton Obote on January 25, 1971...

. The successful coup is often cited as an example of "action by the military", where the Ugandan Armed Forces acted against a government whose politics posed more of a threat to the military privileges. One of the priorities of the new president was mass executions of Acholi and Langi troops, which owed their loyalty to Obote. In July 1971, Lango and Acholi soldiers were massacred in the Jinja

Jinja, Uganda

Jinja is the largest town in Uganda, Africa. It is the second busiest commercial center in the country, after Kampala, Uganda's capital and only city. Jinja was established in 1907.-Location:...

and Mbarara

Mbarara

Mbarara is a town in Western Uganda. It is the main municipal, administrative and commercial center of Mbarara District and the location of the district headquarters. It is also the largest urban centre in Western Uganda.-Location:...

Barracks

Barracks

Barracks are specialised buildings for permanent military accommodation; the word may apply to separate housing blocks or to complete complexes. Their main object is to separate soldiers from the civilian population and reinforce discipline, training and esprit de corps. They were sometimes called...

, and by early 1972, some 5,000 Acholi and Lango soldiers had disappeared. Amin's rule was welcomed by the Baganda, but tens of thousands of Obote supporters fled south into Tanzania

Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

. Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere

Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere was a Tanzanian politician who served as the first President of Tanzania and previously Tanganyika, from the country's founding in 1961 until his retirement in 1985....

would prove to be a strong opponent of the Amin government, an attitude mirrored by Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

, South Africa and the Organisation for African Unity, though Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

, Great Britain and the United States were quick to recognize the legitimacy of the Amin government.

While the military had grown under Obote, it multiplied in size under Amin, who characterized the government in military terms. He renamed Government House "the Command Post", placed military tribunal

Military tribunal

A military tribunal is a kind of military court designed to try members of enemy forces during wartime, operating outside the scope of conventional criminal and civil proceedings. The judges are military officers and fulfill the role of jurors...

s over civil courts, appointed military commanders to head civilian ministries and parastatals, and informed civilian cabinet ministers that they were subject to military law

Military law

Military justice is the body of laws and procedures governing members of the armed forces. Many states have separate and distinct bodies of law that govern the conduct of members of their armed forces. Some states use special judicial and other arrangements to enforce those laws, while others use...

. The commanders of barracks located around the country became the de facto rulers of their regions. Despite the characterization of the country in terms of a military command structure, the administration was far from well-organized. Amin, like many of the officers he appointed to senior positions, was illiterate, and thus gave instructions orally, in person, by telephone or in long rambling speeches.

The regime was subject to deadly internal rivalries. One area of competition was a rivalry between British-trained officers and Israeli-trained officers, who both opposed the many untrained officers, resulting in many trained officers being purged. The purges also had the effect of creating promotion opportunities; commander of the air force Smuts Guweddeko began as a telephone operator. Another contest was religious in nature. In order to gain supplies from Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

, in early 1972 Amin expelled the Israeli advisers, who had helped put him in power, and became virulently anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionistic views or opposition to the state of Israel. The term is used to describe various religious, moral and political points of view in opposition to these, but their diversity of motivation and expression is sufficiently different that "anti-Zionism" cannot be...

. To gain the favor of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

he embraced his Islamic heritage, raising hopes among Ugandan Muslims

Islam in Uganda

According to the National Census 2002 Islam is practiced by 12.1 percent of the population.-History:Islam had arrived in Uganda from the north and through inland networks of the East African coastal trade by the mid-nineteenth century...

that their defeat in 1892 would be redressed. Amin deployed soldiers to aid Egypt and provided financial support to the Arab nations during the Yom Kippur War

Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, Ramadan War or October War , also known as the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and the Fourth Arab-Israeli War, was fought from October 6 to 25, 1973, between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria...

. When Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations or Special Operations or Special Operations Group were organizational names used by Palestinian radical Wadie Haddad when engaging in international attacks, that were regarded as terrorism, and were not sanctioned by the...

and German Revolutionary Cells (RZ)

Revolutionary Cells (RZ)

Revolutionary Cells was a German left-wing political militancy of self-described "urban guerillas" who were active from 1973 to 1993. According to the office of the German Federal Prosecutor, the RZ claimed responsibility for 186 attacks, of which 40 were committed in West Berlin...

terrorists hijacked a plane in 1976 and landed it at Entebbe International Airport

Entebbe International Airport

Entebbe International Airport is the principal international airport of Uganda.-Location:It is located near the town of Entebbe, on the shores of Lake Victoria, and about from the capital, Kampala...

, Israeli commandos

Sayeret Matkal

Sayeret Matkal is a special forces unit of the Israel Defence Forces , which is subordinated to the intelligence directorate Aman. First and foremost a field intelligence-gathering unit, conducting deep reconnaissance behind enemy lines to obtain strategic intelligence, Sayeret Matkal is also...

carried out a raid

Operation Entebbe

Operation Entebbe was a counter-terrorist hostage-rescue mission carried out by the Special Forces of the Israel Defense Forces at Entebbe Airport in Uganda on 4 July 1976. A week earlier, on 27 June, an Air France plane with 248 passengers was hijacked by Palestinian and German terrorists and...

that successfully freed most of the hostages. Criticism by the Church of Uganda

Church of Uganda

The Church of the Province of Uganda is a member church of the Anglican Communion. Currently there are 34 dioceses which make up the Church of Uganda, each headed by a bishop....

of army abuses would lead to the murder of Archbishop Janani Luwum

Janani Luwum

Janani Jakaliya Luwum , was the Archbishop of the Church of Uganda from 1974 to 1977 and one of the most influential leaders of the modern church in Africa. He was murdered in 1977 by either Idi Amin personally or by Amin's henchmen.-Early life and career:Luwum was born in the village of Mucwini in...

.

With his reputation with Western nations in tatters after the hijacking, Amin began to purchase weapons from the Soviet Union. As his regime neared its end, Amin became increasingly eccentric and bellicose. In 1978 he conferred the decoration Conqueror of the British Empire upon himself. The government all but ceased to function as the constant purges of senior ranks by the increasingly paranoid Amin caused officials to refrain from making any decisions for fear of making the 'wrong' one.

Anti-Amin rebellion and the Ugandan-Tanzanian War

Amin was also preoccupied with the dissident groups that Obote had gathered in exile in Tanzania. In late 1972, a small rebel force crossed the border with the apparent intention of capturing the army outpost at MasakaMasaka

Masaka is a town in Central Uganda, lying west of Lake Victoria. It is the chief town of Masaka District. Besides being the headquarters of Masaka District, the town is the regional headquarters and largest metropolitan area in Lyantonde District, Sembabule District, Lwengo District, Bukomansimbi...

, but stopped short and instead waited in expectation of a popular uprising to overthrow Amin. The uprising did not materialize and the Obote-aligned force was expelled by the Malire Mechanical Regiment. The event prompted Amin to task the General Service Unit, now renamed the Special Research Bureau, and the newly-formed Public Safety Unit with an intensified search for suspected subversives. Thousands of people were disappeared

Forced disappearance

In international human rights law, a forced disappearance occurs when a person is secretly abducted or imprisoned by a state or political organization or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organization, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the...

. Amin also retaliated by further purging the army of Obote supporters, predominantly those from the Acholi and Lango

Lango

-Lango of Uganda:The Lango or Jo Lango live in the Lango sub-region , north of Lake Kyoga. Lango sub-region comprises the districts of Amolatar, Alebtong, Apac, Dokolo, Kole, Lira, Oyam, and Otuke...

ethnic groups.

The political environment became increasingly unstable and paranoia-inducing as the regime continued and Amin's circle of supporters grew smaller and smaller due the purges and disappearances. In 1978, General Mustafa Adrisi

Mustafa Adrisi

General Mustafa Adrisi was Vice President of Uganda , and one of president Idi Amin's closest associates. In 1978, after Adrisi was injured in a suspicious auto accident, troops loyal to him mutinied. Amin sent troops against the mutineers, some of whom had fled across the Tanzanian border,...

, an Amin supporter, was injured in a suspicious automobile accident and units loyal to him, including the once-loyal Malire Mechanized Regiment, mutinied. Amin sent loyalist units to crush the uprising, causing some of the mutineers to flee south into Tanzania. Amin, seeking to deflect blame and rally the populace, then accused Tanzania's Nyerere of being the cause of the fighting and sent troops across the border to formally annex 700 miles of Tanzania known as the Kagera Salient on 1 November 1978. In response, Nyerere declared a state of war

State of War

State of war may refer to:*a situation where two or more states are at war with each other, with or without a real armed conflict*State of War , a book by James Risen which makes numerous controversial allegations about Central Intelligence Agency activities*State of War , a real-time strategy...

and mobilized the Tanzania People's Defence Force

Tanzania People's Defence Force

The Tanzania Peoples’ Defence Force was set up in September 1964. From its inception, it was ingrained in the troops that they were a people’s force under civilian control. They were always reminded of their difference from the colonial armed forces...

for a full-scale conflict. Within several weeks, the Tanzanian army was expanded from 40,000 to over 100,000 with the addition of police, prison guards, militia and others. They were joined by the various anti-Amin forces, who in March 1979 coalesced into the Uganda National Liberation Front

Uganda National Liberation Front

The Uganda National Liberation Front was a political group formed by exiled Ugandans opposed to the rule of Idi Amin with an accompanying military wing, the Uganda National Liberation Army . UNLA fought alongside Tanzanian forces in the Uganda-Tanzania War that led to the overthrow of Idi Amin's...

(UNLF). The UNLF was composed of the Obote-led Kikosi Maalum

Kikosi Maalum

Kikosi Maalum was a militia of Ugandan exiles formed in Tanzania to fight against the regime of Idi Amin. Led by Milton Obote, Kikosi Maalum and FRONASA, as well as several smaller groups including Save Uganda Movement and Uganda Freedom Union, formed the Uganda National Liberation Front and its...

and the Front for National Salvation

Front for National Salvation

The Front for National Salvation was a Ugandan rebel group formed by Yoweri Museveni in 1972. Kikosi Maalum and FRONASA, as well as several smaller groups including Save Uganda Movement and Uganda Freedom Union, formed the Uganda National Liberation Front and its military wing the Uganda...

, led by political newcomer Yoweri Museveni

Yoweri Museveni

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni is a Ugandan politician and statesman. He has been President of Uganda since 26 January 1986.Museveni was involved in the war that deposed Idi Amin Dada, ending his rule in 1979, and in the rebellion that subsequently led to the demise of the Milton Obote regime in 1985...

, as well as several smaller anti-Amin groups.

The Tanzanian army, with the support of the UNLF, drove the Ugandan forces out of Tanzania and began an invasion of Uganda. The Ugandan army offered little resistance and retreated steadily, spending much of its energies looting the countryside. Libya's Muammar al-Gaddafi sent 3,000 troops to support the Ugandan defense, but these troops found themselves fighting on the front lines, as Ugandan units in the rear commandeered their supply trucks to carry their plunder away. On 11 April 1979, Kampala fell

Fall of Kampala

The Fall of Kampala was a battle during the Uganda-Tanzania War, in which the combined forces of the Tanzanian army and the Uganda National Liberation Army attacked and captured the Ugandan capital, Kampala...

to the invaders and Amin fled into exile, marking the first time in the post-colonial era that an African nation successfully invaded another.

Disunity and the Ugandan Bush War (1979-1986)

The lack of cohesion between the various Ugandan groups that formed the UNLF quickly became apparent as president Yusuf LuleYusuf Lule

Yusuf Kironde Lule was provisional president of Uganda between 13 April and 20 June 1979. His name is sometimes spelled Yusufu.-Early years:...

was replaced by Godfrey Binaisa

Godfrey Binaisa

Godfrey Lukongwa Binaisa QC was a Ugandan lawyer who was Attorney General of Uganda from 1962 to 1968 and later served as President of Uganda from June 1979 to May 1980. At his death he was Uganda's only surviving former president....

, a former minister in the UPC. While the UNLF force that helped overthrow Amin numbered only 1000, in 1979, Museveni and David Oyite-Ojok

David Oyite-Ojok

David Oyite Ojok was a Ugandan military commander who held one of the leadership positions in the coalition between Uganda National Liberation Army and Tanzania People's Defence Force which removed strongman Idi Amin in 1979 and, until his death in a helicopter crash, served as the national army...

, a Langi like Obote, began a massive recruitment of soldiers into what were in-effect their personal armies. When Binaisa attempted to stop this rapid military expansion, he was deposed by Museveni, Oyite-Ojok and Obote-stalwart Paulo Muwanga

Paulo Muwanga

Paulo Muwanga was the chairman of the governing Military Commission, and the de-facto President of Uganda for a few days in May 1980 until the establishment of the Presidential Commission of Uganda. The Presidential Commission, with Muwanga as chairman, held the office of President of Uganda...

. After Muwanga's rise to power, Obote returned to the country to stand in elections. In an intensely contested and highly compromised election held on December 10, 1980, Obote was re-elected president with Muwanga as his vice-president. In response, Museveni declared armed opposition to Obote's UNLF government. In 1980, Museveni merged his Popular Resistance Army

Popular Resistance Army

The Popular Resistance Army was a rebel group formed in 1980 by Yoweri Museveni to fight against the regime of Milton Obote....

(PRA) with Lule's Uganda Freedom Fighters

Uganda Freedom Fighters

The Uganda Freedom Fighters were a Ugandan rebel group led by former president Yusufu Lule. The group merged with Yoweri Museveni's Popular Resistance Army to create the National Resistance Army . The NRA would go on to topple the military junta of Tito Okello and take power in 1986....

, forming the National Resistance Army

National Resistance Army

The National Resistance Army , the military wing of the National Resistance Movement , was a rebel army that waged a guerrilla war, commonly referred to as the Luwero War or "the war in the bush", against the government of Milton Obote, and later that of Tito Okello.NRA was supported by Muammar...

(NRA). As well as the NRA, two rebel groups based in Amin's home West Nile sub-region

West Nile sub-region

West Nile sub-region is a region in north-western Uganda that consists of the districts of Adjumani, Arua, Koboko, Maracha-Terego, Moyo, Nebbi and Yumbe...

emerged: the Uganda National Rescue Front

Uganda National Rescue Front

The Uganda National Rescue Front , refers to two former armed rebel groups in Uganda's West Nile sub-region that first opposed, then became incorporated into the Ugandan armed forces.-UNRF:...

and the Former Uganda National Army.

The beginning of the Ugandan Bush War

Ugandan Bush War

The Ugandan Bush War refers to the guerrilla war waged between 1981 and 1986 in Uganda by the National Resistance Army against the government of Milton Obote, and later that of Tito Okello.-Events leading to the war:Following the Uganda-Tanzania War that removed Idi Amin in 1979, a...

was marked by an NRA attack in the central Mubende District

Mubende District

Mubende is a district in Central Uganda. Like most other Ugandan districts, it is named after its 'chief town', Mubende. Mubende District was reduced in size in July 2005 with the creation of Mityana District.-Location:...

on 6 February 1981. The NRA insurgency was based largely in the anti-Obote strongholds of central and western Buganda and the former kingdoms of Ankole and Bunyoro. Fighting was particularly intense in the Luwero triangle

Luwero triangle

The Luweero triangle, sometimes spelled Luwero Triangle, is an area of Uganda to the north of the capital Kampala, where Yoweri Museveni started the guerrilla war in 1981, that propelled him and his National Resistance Movement into power in 1986....

of Buganda, where the bitter memory of the counterinsurgency efforts of the UNLF's Langi and Acholi soldiers against the populace would prove an enduring legacy. The NRA was highly organized, forming Resistance Councils

Local Council

A Local Council is a form of local elected government within the districts of Uganda. They were initially established as rebel support structures in the areas controlled by the National Resistance Army of Yoweri Museveni. At this time, they were known as Resistance Councils and proved...

in areas they controlled to funnel recruits and supplies into the war effort. In comparison, the inability of the UNLF government to defeat the rebels both in the west and West Nile proved devastating to the unity of the government, while the brutality of the counter-insurgency further inflamed anti-Obote sentiment in the occupied areas. Following the death of General Oyite-Ojok in a helicopter crash at the end of 1983, the Acholi-Langi alliance began to fracture. On 27 January 1985, Acholi troops under Brigadier Bazilio Olara-Okello

Bazilio Olara-Okello

Bazilio Olara-Okello was a Ugandan military officer and one of the commanders of the Uganda National Liberation Army that together with the Tanzanian army overthrew Idi Amin in 1979...

staged a successful coup and put fellow Acholi General Tito Okello

Tito Okello

General Tito Lutwa Okello , was a Ugandan Military officer and politician. He was the President of Uganda from 29 July 1985 until 26 January 1986.-Background:Tito Okello was born in 1914 in Kitgum District...

into the presidency as Obote once again fled into exile, this time for good. The Okello government had little policy besides self-preservation. After an Okello-Museveni peace agreement

Nairobi Agreement, 1985

The Nairobi Agreement was a peace deal between the Ugandan government of Tito Okello and the National Resistance Army rebel group led by Yoweri Museveni...