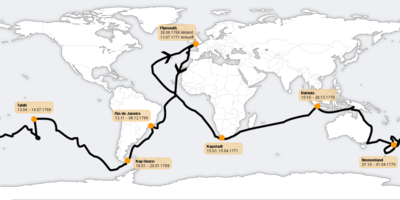

First voyage of James Cook

Encyclopedia

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

and Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

expedition to the south Pacific ocean aboard HMS Endeavour

HMS Endeavour

HMS Endeavour may refer to one of the following ships:In the Royal Navy:, a 36-gun ship purchased in 1652 and sold in 1656, a 4-gun bomb vessel purchased in 1694 and sold in 1696, a fire ship purchased in 1694 and sold in 1696, a storeship hoy purchased in 1694 and sold in 1705, a storeship...

, from 1768 to 1771. The aims of the expedition were to observe the 1769 transit of Venus

Transit of Venus

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black disk moving across the face of the Sun...

across the Sun (3–4 June of that year), and to seek evidence of the postulated Terra Australis Incognita or "unknown southern land".

The voyage was commissioned by King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

and commanded by Lieutenant James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

, a junior naval officer with skills in cartography

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

and mathematics. Departing Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

in August 1768, the expedition crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island...

and reached Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

in time to observe the transit of Venus. Cook then set sail into the largely uncharted ocean to the south, stopping at the Pacific islands of Huahine

Huahine

Huahine is an island located among the Society Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Leeward Islands group . The island has a population of about 6,000.-Geography:...

, Borabora and Raiatea

Raiatea

Raiatea , is the second largest of the Society Islands, after Tahiti, in French Polynesia. The island is widely regarded as the 'center' of the eastern islands in ancient Polynesia and it is likely that the organised migrations to Hawaii, Aotearoa and other parts of East Polynesia started at...

to claim them for Great Britain, and unsuccessfully attempting to land at Rurutu

Rurutu (Austral Islands)

Rurutu is the northernmost island in the Austral archipelago of French Polynesia, and the name of a commune consisting solely of that island. It is situated south of Tahiti....

. In September 1769, the expedition reached New Zealand, being the second Europeans to visit there, following its earlier discovery by Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

127 years earlier. Cook and his crew spent the following six months charting the New Zealand coast, before resuming their voyage westward across open sea. In April 1770, they became the first Europeans to reach the east coast of Australia, making landfall on the shore of what is now known as Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

.

The expedition continued northward along the Australian coastline, narrowly avoiding shipwreck on the Great Barrier Reef

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world'slargest reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,600 kilometres over an area of approximately...

. In October 1770, the badly damaged Endeavour came into the port of Batavia in the Dutch East Indies

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Netherlands government in 1800....

, her crew sworn to secrecy about the lands they had discovered. They resumed their journey on 26 December, rounded the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

on 13 March 1771, and reached the English port of Deal

Deal, Kent

Deal is a town in Kent England. It lies on the English Channel eight miles north-east of Dover and eight miles south of Ramsgate. It is a former fishing, mining and garrison town...

on 12 July. The voyage lasted almost three years.

Conception

On 16 February 1768, the Royal SocietyRoyal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

petitioned King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

to finance a scientific expedition to the Pacific to study and observe the 1769 transit of Venus across the sun. Royal approval was granted for the expedition, and the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

elected to combine the scientific voyage with a confidential mission to search the south Pacific for signs of the postulated continent Terra Australis Incognita (or "unknown southern land").

The Royal Society suggested command be given to Scottish geographer Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple was a Scottish geographer and the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty. He was the main proponent of the theory that there existed a vast undiscovered continent in the South Pacific, Terra Australis Incognita...

, whose acceptance was conditional on a brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

commission as a captain in the Royal Navy. However, First Lord of the Admiralty Edward Hawke refused, going so far as to say he would rather cut off his right hand than give command of a Navy vessel to someone not educated as a seaman. In refusing Dalrymple's command, Hawke was influenced by previous insubordination aboard the sloop in 1698, when naval officers had refused to take orders from civilian commander Dr. Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley FRS was an English astronomer, geophysicist, mathematician, meteorologist, and physicist who is best known for computing the orbit of the eponymous Halley's Comet. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, following in the footsteps of John Flamsteed.-Biography and career:Halley...

. The impasse was broken when the Admiralty proposed James Cook, a naval officer with a background in mathematics and cartography

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

. Acceptable to both parties, Cook was promoted to Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

and named as commander of the expedition.

Vessel and provisions

Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk, Whitby has a combined maritime, mineral and tourist heritage, and is home to the ruins of Whitby Abbey where Caedmon, the...

in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is a non-metropolitan or shire county located in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England, and a ceremonial county primarily in that region but partly in North East England. Created in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972 it covers an area of , making it the largest...

. She was ship-rigged

Full rigged ship

A full rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel with three or more masts, all of them square rigged. A full rigged ship is said to have a ship rig....

and sturdily built with a broad, flat bow, a square stern and a long box-like body with a deep hold. A flat-bottomed design made her well-suited to sailing in shallow waters and allowed her to be beached

Beach (nautical)

Beaching is when a vessel is laid ashore, or grounded deliberately in shallow water. This is more usual with small flat-bottomed boats. Larger ships may be beached deliberately, for instance in an emergency a damaged ship might be beached to prevent it from sinking in deep water...

for loading and unloading of cargo and for basic repairs without requiring a dry dock

Dry dock

A drydock is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform...

. Her length was 106 feet (32.3 m), with a beam

Beam (nautical)

The beam of a ship is its width at the widest point. Generally speaking, the wider the beam of a ship , the more initial stability it has, at expense of reserve stability in the event of a capsize, where more energy is required to right the vessel from its inverted position...

of 29 in 3 in (8.92 m) and a burthen was 368 tons.

Earl of Pembroke was purchased by the Admiralty in May 1768 for and sailed to Deptford

Deptford

Deptford is a district of south London, England, located on the south bank of the River Thames. It is named after a ford of the River Ravensbourne, and from the mid 16th century to the late 19th was home to Deptford Dockyard, the first of the Royal Navy Dockyards.Deptford and the docks are...

on the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

to be prepared for the voyage. Her hull was sheathed and caulked

Caulking

Caulking is one of several different processes to seal joints or seams in various structures and certain types of piping. The oldest form of caulking is used to make the seams in wooden boats or ships watertight, by driving fibrous materials into the wedge-shaped seams between planks...

, and a third internal deck installed to provide cabins, a powder magazine and storerooms. A longboat

Longboat

In the days of sailing ships, a vessel would carry several ship's boats for various uses. One would be a longboat, an open boat to be rowed by eight or ten oarsmen, two per thwart...

, pinnace

Pinnace (ship's boat)

As a ship's boat the pinnace is a light boat, propelled by sails or oars, formerly used as a "tender" for guiding merchant and war vessels. In modern parlance, pinnace has come to mean a boat associated with some kind of larger vessel, that doesn't fit under the launch or lifeboat definitions...

and yawl

Yawl

A yawl is a two-masted sailing craft similar to a sloop or cutter but with an additional mast located well aft of the main mast, often right on the transom, specifically aft of the rudder post. A yawl (from Dutch Jol) is a two-masted sailing craft similar to a sloop or cutter but with an...

were provided as ship's boats, as well as a set of 28 ft (8.5 m) sweeps to allow the ship to be rowed if becalmed or demasted. After commissioning into the Royal Navy as His Majesty's Bark

Barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts.- History of the term :The word barque appears to have come from the Greek word baris, a term for an Egyptian boat. This entered Latin as barca, which gave rise to the Italian barca, Spanish barco, and the French barge and...

the Endeavour, the ship was supplied with ten 4-pounder cannons and twelve swivel guns, for defence against native attack while in the Pacific.

Provisions loaded at the outset of the voyage included 6,000 pieces of pork and 4,000 of beef, nine tons of bread, five tons of flour, three tons of sauerkraut, one ton of raisins and sundry quantities of cheese, salt, peas, oil, sugar and oatmeal. Alcohol supplies consisted of 250 barrels of beer, 44 barrels of brandy and 17 barrels of rum.

Ship's company

On 30 July 1768 the Admiralty authorised a ship's company for the voyage, of 73 sailors and 12 Royal MarinesRoyal Marines

The Corps of Her Majesty's Royal Marines, commonly just referred to as the Royal Marines , are the marine corps and amphibious infantry of the United Kingdom and, along with the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, form the Naval Service...

. The voyage was commanded by 40-year-old Lieutenant James Cook. His second lieutenant was Zachary Hicks, a 29-year old from Stepney

Stepney

Stepney is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in London's East End that grew out of a medieval village around St Dunstan's church and the 15th century ribbon development of Mile End Road...

with experience as acting commander of the HMS Hornet

HMS Hornet

Ten ships and one shore establishment of the British Royal Navy have been named HMS Hornet, after the insect:* HMS Hornet, a 14-gun sloop launched in 1745...

, a 16-gun cutter. The third lieutenant was John Gore

John Gore (seaman)

Captain John Gore was a British American sailor who circumnavigated the globe four times with the Royal Navy in the 18th century and accompanied Captain James Cook in his discoveries in the Pacific Ocean.-History:...

, a 16-year Naval veteran who had served as master's mate

Master's mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the master...

aboard HMS Dolphin

HMS Dolphin (1751)

HMS Dolphin was a 24-gun sixth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. Launched in 1751, she was used as a survey ship from 1764 and made two circumnavigations of the world under the successive commands of John Byron and Samuel Wallis. She was the first ship to circumnavigate the world twice...

during its circumnavigation of the world in 1766.

Voyage of discovery

Cook departed PlymouthPlymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

on 26 August 1768, carrying 94 people and 18 months of provisions. The ship rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island...

and continued westward across the Pacific to arrive at Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

on 13 April 1769, where the observations were to be made. The transit was scheduled to occur on 3 June, and in the meantime he commissioned the building of a small fort

Fortification

Fortifications are military constructions and buildings designed for defence in warfare and military bases. Humans have constructed defensive works for many thousands of years, in a variety of increasingly complex designs...

and observatory

Observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geology, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed...

at what is now known as Point Venus.

The astronomer

Astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist who studies celestial bodies such as planets, stars and galaxies.Historically, astronomy was more concerned with the classification and description of phenomena in the sky, while astrophysics attempted to explain these phenomena and the differences between them using...

appointed to the task was Charles Green

Charles Green (astronomer)

Charles Green was a British astronomer, noted for his assignment by the Royal Society in 1768 to the expedition sent to the Pacific Ocean in order to observe the transit of Venus and the transit of Mercury, aboard James Cook's Endeavour.A farmer's son, he became assistant to the Astronomer Royal...

, assistant to the recently appointed Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the second is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834....

, Nevil Maskelyne

Nevil Maskelyne

The Reverend Dr Nevil Maskelyne FRS was the fifth English Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811.-Biography:...

. The primary purpose of the observation was to obtain measurements that could be used to calculate more accurately the distance of Venus

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, orbiting it every 224.7 Earth days. The planet is named after Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty. After the Moon, it is the brightest natural object in the night sky, reaching an apparent magnitude of −4.6, bright enough to cast shadows...

from the Sun. If this could be achieved, then the distances of the other planets could be worked out, based on their orbits. On the day of the transit observation, Cook recorded:

Saturday 3 rd This day prov'd as favourable to our purpose as we could wish, not a Clowd was to be seen the Whole day and the Air was perfectly clear, so that we had every advantage we could desire in Observing the whole of the passage of the Planet Venus over the Suns disk: we very distinctly saw an Atmosphere or dusky shade round the body of the Planet which very much disturbed the times of the contacts particularly the two internal ones. D r Solander observed as well as M r Green and my self, and we differ'd from one another in observeing the times of the Contacts much more than could be expected.

Disappointingly, the separate measurements of Green, Cook and Solander varied by more than the anticipated margin of error. Their instrumentation was adequate by the standards of the time, but the resolution still could not eliminate the errors. When their results were later compared to those of the other observations of the same event made elsewhere for the exercise, the net result was not as conclusive or accurate as had been hoped. The difficulties are today thought to relate to the Black drop effect

Black drop effect

The black drop effect is an optical phenomenon visible during a transit of Venus and, to a lesser extent, a transit of Mercury.Just after second contact, and again just before third contact during the transit, a small black "teardrop" appears to connect Venus' disk to the limb of the Sun, making it...

, an optical phenomenon that precludes accurate measurement – particularly with the instruments used by Cook, Green and Solander.

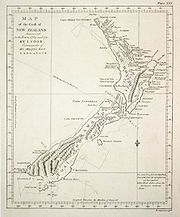

New Zealand

Once the observations were completed, Cook opened the sealed ordersSealed Orders

Sealed orders are the orders given the commanding officer of a ship or squadron that are sealed up, which he is not allowed to open until he has proceeded a certain length into the high seas; an arrangement in order to ensure secrecy in a time of war....

for the second part of his voyage: to search the south Pacific for signs of the postulated rich southern continent

Continent

A continent is one of several very large landmasses on Earth. They are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, with seven regions commonly regarded as continents—they are : Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia.Plate tectonics is...

of Terra Australis

Terra Australis

Terra Australis, Terra Australis Ignota or Terra Australis Incognita was a hypothesized continent appearing on European maps from the 15th to the 18th century...

, acting on additional instructions from the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

. The Royal Society, and especially Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple was a Scottish geographer and the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty. He was the main proponent of the theory that there existed a vast undiscovered continent in the South Pacific, Terra Australis Incognita...

, believed that it must exist and that Britain's best chance of discovering it and claiming its fabled riches before any other rival European power managed to do so would be by using Cook's Transit of Venus mission (on an inconspicuous small ship such as the Endeavour) as a cover.

Cook, however, had his own personal doubts on the continent's existence. With the help of a Tahitian named Tupaia

Tupaia (navigator)

Tupaia was a Polynesian navigator and arioi , originally from the island of Ra'iatea in the Pacific Islands group known to Europeans as the Society Islands. His remarkable navigational skills and Pacific geographical knowledge were to be utilised by Lt. James Cook, R.N...

, who had extensive knowledge of Pacific geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

, Cook managed to reach New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

on 6 October 1769, leading only the second group of Europeans

European ethnic groups

The ethnic groups in Europe are the various ethnic groups that reside in the nations of Europe. European ethnology is the field of anthropology focusing on Europe....

to do so (after Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

over a century earlier, in 1642). Cook mapped the complete New Zealand coastline, making only some minor errors (such as calling Banks Peninsula

Banks Peninsula

Banks Peninsula is a peninsula of volcanic origin on the east coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It has an area of approximately and encompasses two large harbours and many smaller bays and coves...

an island, and thinking Stewart Island/Rakiura

Stewart Island/Rakiura

Stewart Island/Rakiura is the third-largest island of New Zealand. It lies south of the South Island, across Foveaux Strait. Its permanent population is slightly over 400 people, most of whom live in the settlement of Oban.- History and naming :...

was a peninsula of the South Island

South Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

). He also identified Cook Strait

Cook Strait

Cook Strait is the strait between the North and South Islands of New Zealand. It connects the Tasman Sea on the west with the South Pacific Ocean on the east....

, which separates the North Island

North Island

The North Island is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the much less populous South Island by Cook Strait. The island is in area, making it the world's 14th-largest island...

from the South Island, and which Tasman had not seen.

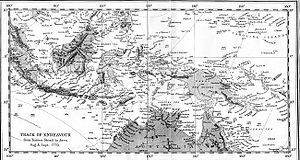

Australian coast

He then set course westwards, intending to strike for Van Diemen's LandVan Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

(present-day Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

, sighted by Tasman) to establish whether or not it formed part of the fabled southern continent. However, they were forced to maintain a more northerly course owing to prevailing gales, and sailed onwards until one afternoon when land was sighted, which Cook named Point Hicks

Point Hicks

Point Hicks, formerly called Cape Everard, is a coastal headland on the eastern coast of Victoria, Australia, located within the Croajingolong National Park.- Name :...

. Cook calculated that Van Diemen's Land ought to lie due south of their position, but having found the coastline trending to the southwest, recorded his doubt that this landmass was connected to it. This point was on the southeastern coast of the Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n continent, and in doing so his expedition became the first recorded Europeans to have encountered its eastern coastline. In his journal, Cook recorded the event thus:

the Southermost Point of land we had in sight which bore from us W1/4S I judged to lay in the Latitude of 38°..0' S° and in the Longitude of 211°..07' W t from the Meridion of Greenwich. I have named it Point Hicks, because Leuit t Hicks was the first who discover'd this land.

The ship's log recorded that land was sighted at 6 a.m. on Thursday 19 April 1770. Cook's log used the nautical date, which, during the 18th century, assigned the same date to all ship's events from noon to noon, first p.m. and then a.m. That nautical date began twelve hours before the midnight beginning of the like-named civil date. Furthermore, Cook did not adjust his nautical date to account for circumnavigation of the globe until he had travelled a full 360° relative to the longitude

Longitude

Longitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east-west position of a point on the Earth's surface. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees, minutes and seconds, and denoted by the Greek letter lambda ....

of his home British port, either toward the east or west. Because he travelled west on his first voyage, this a.m. nautical date was the morning of a civil date 14 hours slow relative to his home port (port−14h). Because the southeast coast of Australia is now regarded as being 10 hours fast relative to Britain, that date is now called Friday, 20 April.

The landmark of this sighting is generally reckoned to be a point lying about half-way between the present-day towns of Orbost

Orbost, Victoria

Orbost is a town in the Shire of East Gippsland, Victoria, Australia, located east of Melbourne and south of Canberra where the Princes Highway crosses the Snowy River. It is about from the town of Marlo on the coast of Bass Strait. At the 2006 census, Orbost had a population of 2452...

and Mallacoota

Mallacoota, Victoria

-External links:***...

on the southeastern coast of the state of Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

. A survey done in 1843 ignored or overlooked Cook's earlier naming of the point, giving it the name Cape Everard. On the 200th anniversary of the sighting, the name was officially changed back to Point Hicks.

Botany Bay

EndeavourHM Bark Endeavour

HMS Endeavour, also known as HM Bark Endeavour, was a British Royal Navy research vessel commanded by Lieutenant James Cook on his first voyage of discovery, to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771....

continued northwards along the coastline, keeping the land in sight with Cook charting and naming landmarks as he went. A little over a week later, they came across an extensive but shallow inlet, and upon entering it moored off a low headland fronted by sand dunes. James Cook and crew made their first landing on the continent, at a place now known as Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

, on the Kurnell Peninsula

Cronulla sand dunes, Kurnell Peninsula

The Cronulla sand dunes are located on the Kurnell Peninsula in the local government area of Sutherland Shire, Sydney Australia.The Cronulla sand dunes are a protected area that became listed on the NSW State Heritage Register on 26 September 2003.-History:...

and made contact of a hostile nature with the Gweagal

Gweagal

The Gweagal are a clan of the Tharawal tribe of Indigenous Australians, who are traditional custodians of the southern geographic areas of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia....

Aborigines, on 29 April. At first Cook bestowed the name "Sting-Ray Harbour" to the inlet after the many such creatures found there; this was later changed to "Botan ist Bay" and finally Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

after the unique specimens retrieved by the botanists Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

, Daniel Solander

Daniel Solander

Daniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus. Solander was the first university educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.-Biography:...

and Herman Spöring.

Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip RN was a British admiral and colonial administrator. Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales, the first European colony on the Australian continent, and was the founder of the settlement which is now the city of Sydney.-Early life and naval career:Arthur Phillip...

and the First Fleet

First Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

arrived in early 1788 to establish an outpost and penal colony

Penal colony

A penal colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general populace by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory...

, they found that the bay and surrounds did not live up to the promising picture that had been painted. Instead, Phillip gave orders to relocate to a harbour a few kilometres to the north, which Cook had named Port Jackson

Port Jackson

Port Jackson, containing Sydney Harbour, is the natural harbour of Sydney, Australia. It is known for its beauty, and in particular, as the location of the Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge...

but had not further explored. It was in this harbour, at a place Phillip named Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove is a small bay on the southern shore of Port Jackson , on the coast of the state of New South Wales, Australia....

, that the settlement of Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

was established. The settlement was for some time afterwards still referred to generally as Botany Bay. The expedition's scientific members commenced the first European scientific documentation of Australian fauna and flora.

At Cook's original landing contact was made with the local Australian Aboriginal inhabitants. As the ships sailed into the harbour, they noticed Aborigines on both of the headlands. At about 2 pm they put the anchor down near a group of six to eight huts. Two Aborigines, a younger and an older man, came down to the boat. They ignored gifts from Cook. A musket was fired over their heads, which wounded the older man slightly, and he ran towards the huts. He came back with other men and threw spears at Cook's men, although they did no harm. They were chased off after two more rounds were fired. The adults had left, but Cook found several Aboriginal children in the huts, and left some beads with them as a gesture of friendship.

Endeavour River

Cook continued northwards, charting along the coastline. He stopped at Bustard Head on 24 May 1770. Cook and Banks and others went ashore. A mishap occurred when EndeavourHM Bark Endeavour

HMS Endeavour, also known as HM Bark Endeavour, was a British Royal Navy research vessel commanded by Lieutenant James Cook on his first voyage of discovery, to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771....

ran aground on a shoal of the Great Barrier Reef

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world'slargest reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,600 kilometres over an area of approximately...

, on 11 June 1770. The ship was seriously damaged and his voyage was delayed almost seven weeks while repairs were carried out on the beach (near the docks of modern Cooktown, at the mouth of the Endeavour River

Endeavour River

The Endeavour River on Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland, Australia, was named in 1770 by Lt. James Cook, R.N., after he was forced to beach his ship, HM Bark Endeavour, for repairs in the river mouth, after damaging it on Endeavour Reef...

). While there, Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

, Herman Spöring and Daniel Solander

Daniel Solander

Daniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus. Solander was the first university educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.-Biography:...

made their first major collections of Australian flora. The crew's encounters with the local Aboriginal people were mainly peaceable; from the group encountered here the name "kangaroo

Kangaroo

A kangaroo is a marsupial from the family Macropodidae . In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, especially those of the genus Macropus, Red Kangaroo, Antilopine Kangaroo, Eastern Grey Kangaroo and Western Grey Kangaroo. Kangaroos are endemic to the country...

" entered the English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

, coming from the local Guugu Yimidhirr word for a kind of Grey Kangaroo, gangurru .

Possession Island

Once repairs were complete the voyage continued, eventually passing by the northern-most point of Cape York PeninsulaCape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in northern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth...

and then sailing through Torres Strait

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait is a body of water which lies between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is approximately wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost continental extremity of the Australian state of Queensland...

between Australia and New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

, earlier navigated by Luis Váez de Torres in 1606. Having rounded the Cape, Cook landed on Possession Island

Possession Island National Park

Possession Island is a small island in the Torres Strait Islands group off the coast of far northern Queensland, Australia.The island is known as Bedanug or Bedhan Lag by its Sovereign Original inhabitants, the Kaurareg people. During his first voyage of discovery James Cook sailed northwards...

on 22 August, where he claimed the entire coastline he had just explored (later naming the region New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

) for the British Crown

Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. The present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, has reigned since 6 February 1952. She and her immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial and representational duties...

.

In negotiating the Torres Strait

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait is a body of water which lies between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is approximately wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost continental extremity of the Australian state of Queensland...

past Cape York

Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in northern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth...

, Cook also put an end to the speculation that New Holland and New Guinea were part of the same land mass.

Scurvy prevention

At that point in the voyage, Cook had lost not a single man to scurvyScurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

, a remarkable and practically unheard-of achievement in 18th century long-distance sea-faring. Adhering to Royal Navy policy introduced in 1747, Cook persuaded his men to eat foods such as citrus

Citrus

Citrus is a common term and genus of flowering plants in the rue family, Rutaceae. Citrus is believed to have originated in the part of Southeast Asia bordered by Northeastern India, Myanmar and the Yunnan province of China...

fruit

Fruit

In broad terms, a fruit is a structure of a plant that contains its seeds.The term has different meanings dependent on context. In non-technical usage, such as food preparation, fruit normally means the fleshy seed-associated structures of certain plants that are sweet and edible in the raw state,...

s and sauerkraut

Sauerkraut

Sauerkraut , directly translated from German: "sour cabbage", is finely shredded cabbage that has been fermented by various lactic acid bacteria, including Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus. It has a long shelf-life and a distinctive sour flavor, both of which result from the lactic acid...

. At that time it was known that poor diet caused scurvy but not specifically that a vitamin C

Vitamin C

Vitamin C or L-ascorbic acid or L-ascorbate is an essential nutrient for humans and certain other animal species. In living organisms ascorbate acts as an antioxidant by protecting the body against oxidative stress...

deficiency was the culprit.

Sailors of the day were notoriously against innovation, and at first the men would not eat the sauerkraut. Cook used a little trick, one he had never known to fail. He ordered it served to himself and the officers, and left an option for crew who wanted some. Within a week of seeing their superiors set a value on it the demand was so great a ration had to be instituted. (Cook's journal 13 April 1769.) In other cases, however, Cook was required to resort to traditional naval discipline. "Punished Henry Stephens, Seaman, and Thomas Dunster, Marine, with twelve lashes each for refusing to take their allowance of fresh beef."

Cook's general approach was essentially empirical, encouraging as broad a diet as circumstances permitted, and collecting such greens

Tetragonia tetragonoides

Tetragonia tetragonioides is a leafy groundcover also known as New Zealand Spinach, Warrigal Greens, Kokihi , Sea Spinach, Botany Bay Spinach, Tetragon and Cook's Cabbage...

as could be had when making landfall. All onboard ate the same food, with Cook specifically dividing equally anything that could be divided (and indeed recommending that practice to any commander – journal 4 August 1770).

Two cases of scurvy did occur on board, astronomer Charles Green

Charles Green (astronomer)

Charles Green was a British astronomer, noted for his assignment by the Royal Society in 1768 to the expedition sent to the Pacific Ocean in order to observe the transit of Venus and the transit of Mercury, aboard James Cook's Endeavour.A farmer's son, he became assistant to the Astronomer Royal...

and the Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

an navigator Tupaia

Tupaia (navigator)

Tupaia was a Polynesian navigator and arioi , originally from the island of Ra'iatea in the Pacific Islands group known to Europeans as the Society Islands. His remarkable navigational skills and Pacific geographical knowledge were to be utilised by Lt. James Cook, R.N...

were treated, but Cook was able to proudly record that upon reaching Batavia

Jakarta

Jakarta is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Officially known as the Special Capital Territory of Jakarta, it is located on the northwest coast of Java, has an area of , and a population of 9,580,000. Jakarta is the country's economic, cultural and political centre...

he had "not one man upon the sick list" (journal 15 October 1770), unlike so many voyages that reached that port with much of the crew suffering illness.

Homeward voyage

Savu

Savu is the largest of a group of three islands, situated midway between Sumba and Rote, west of Timor, in Indonesia's eastern province, East Nusa Tenggara. Ferries connect the islands to Waingapu, on Sumba, and Kupang, in West Timor...

, staying for three days before continuing on to Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Netherlands government in 1800....

, to put in for repairs. Batavia was known for its outbreaks of malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

, and before they returned home in 1771, many in Cook's company succumbed to the disease and other ailments such as dysentery

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

, including the Tahitian Tupaia, Banks' Finnish

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

secretary and fellow scientist Herman Spöring, astronomer Charles Green, and the illustrator Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson was a Scottish Quaker, botanical illustrator and natural history artist.Parkinson was employed by Joseph Banks to travel with him on James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific in 1768. Parkinson made nearly a thousand drawings of plants and animals collected by Banks and Daniel...

. Cook named Spöring Island off the coast of New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

to honour Herman Spöring and his work on the voyage.

Cook then rounded the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

and stopped at Saint Helena

Saint Helena

Saint Helena , named after St Helena of Constantinople, is an island of volcanic origin in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha which also includes Ascension Island and the islands of Tristan da Cunha...

. On 10 July 1771 Nicholas Young, the boy who had first seen New Zealand, sighted England (specifically the Lizard

The Lizard

The Lizard is a peninsula in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The most southerly point of the British mainland is near Lizard Point at ....

) again for the first time, and the Endeavour sailed up the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

, passing Beachy Head

Beachy Head

Beachy Head is a chalk headland on the south coast of England, close to the town of Eastbourne in the county of East Sussex, immediately east of the Seven Sisters. The cliff there is the highest chalk sea cliff in Britain, rising to 162 m above sea level. The peak allows views of the south...

at 6 am on the 12th; that afternoon the Endeavour anchored in the Downs

The Downs

The Downs are a roadstead or area of sea in the southern North Sea near the English Channel off the east Kent coast, between the North and the South Foreland in southern England. In 1639 the Battle of the Downs took place here, when the Dutch navy destroyed a Spanish fleet which had sought refuge...

, and Cook went ashore at Deal, Kent

Deal, Kent

Deal is a town in Kent England. It lies on the English Channel eight miles north-east of Dover and eight miles south of Ramsgate. It is a former fishing, mining and garrison town...

.

Publication of journals

Cook's journalsDiary

A diary is a record with discrete entries arranged by date reporting on what has happened over the course of a day or other period. A personal diary may include a person's experiences, and/or thoughts or feelings, including comment on current events outside the writer's direct experience. Someone...

, along with those of Banks, were handed over to the Admiralty to be published upon his return. Lord Sandwich contracted, for £6,000, John Hawkesworth a literary critic, essayist, and editor of the Gentleman’s Magazine to publish a comprehensive account of exploration in the Pacific: not just Cook's ventures but also those of Wallis

Samuel Wallis

Samuel Wallis was a Cornish navigator who circumnavigated the world.Wallis was born near Camelford, Cornwall. In 1766 he was given the command of HMS Dolphin to circumnavigate the world, accompanied by the Swallow under the command of Philip Carteret...

, Byron

John Byron

Vice Admiral The Hon. John Byron, RN was a Royal Navy officer. He was known as Foul-weather Jack because of his frequent bad luck with weather.-Early career:...

and Carteret

Philip Carteret

Philip Carteret, Seigneur of Trinity was a British naval officer and explorer who participated in two of the Royal Navy's circumnavigation expeditions in 1764-66 and 1766-69.-Biography:...

. Hawkesworth edited the journals of Byron, Wallis and Carteret into separate accounts as volume I and then blended Cook’s and Joseph Banks’ journals with some of his own sentiments and produced a single first-person narrative that appeared to be the words of Cook, as Volume II. The book appeared in 1773 as three volumes with the title:

AN ACCOUNT OF THE VOYAGES undertaken by Order of His Present Majesty for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, and successively performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret and Captain Cook, in the Dolphin, the Swallow and the Endeavour: Drawn up from the Journals which were kept by the several Commanders, and from the Papers of Joseph Banks, Esq.; by John Hawkesworth, LL.D. In three volumes. Illustrated with Cuts, and a great Variety of Charts and Maps relative to Countries now first discovered, or hitherto but imperfectly known.

Printed for W. Strahan & T. Cadell in the Strand. London: MDCCLXXIII

The book went on sale on 9 June 1773 but widespread criticism in the press made the publication a personal disaster for Hawkesworth. Reviewers complained that the reader had no way to tell which part of the account was Cook, which part Banks and which part Hawkesworth and others were offended by the books’

descriptions of the voyagers’ sexual encounters with the Tahitians.

Cook was at sea again before the book was published and was later much disturbed by some of the sentiments that Hawkesworth has ascribed to him. He determined to edit his own journals in future.

Footnotes

In today's terms, this equates to a valuation for Endeavour of approximately £265,000 and a purchase price of £326,400.This date does not need adjustment because it occurred during the afternoon (p.m.) on 29 April in the ship's log, but was the afternoon of the civil date of 28 April, 14 hours west of port, which is now a civil date 10 hours east of port, 24 hours later, hence a modern civil date of 29 April.

External links

- The Endeavour journal (1) and The Endeavour journal (2), as kept by James Cook – digitised and held by the National Library of AustraliaNational Library of AustraliaThe National Library of Australia is the largest reference library of Australia, responsible under the terms of the National Library Act for "maintaining and developing a national collection of library material, including a comprehensive collection of library material relating to Australia and the...

- The South Seas Project: maps and online editions of the Journals of James Cook's First Pacific Voyage. 1768–1771, Includes full text of journals kept by Cook, Joseph Banks and Sydney Parkinson, as well as the complete text of John Hawkesworth's 1773 Account of Cook's first voyage.

- The Endeavour Replica A replica of Captain Cook's vessel.