Prayer Book Rebellion

Encyclopedia

- For the revolts in the 1620s and 30s, see Western RisingWestern RisingThe Western Rising was a series of riots which took place during 1626-1632 in Gillingham Forest on the Wiltshire-Dorset border, Braydon Forest in Wiltshire, and Dean Forest, Gloucestershire, in response to disafforestation of royal forests, sale of royal lands and enclosure of property by the new...

The Prayer Book Rebellion, Prayer Book Revolt, Prayer Book Rising, Western Rising or Western Rebellion was a popular revolt in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

and Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

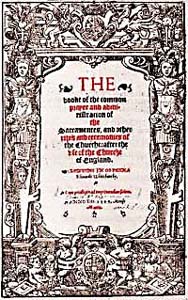

, in 1549. In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

, presenting the theology of the English Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

, was introduced. The change was widely unpopular — particularly in areas of still firmly Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

religious loyalty (even after the Act of Supremacy in 1534

Acts of Supremacy

The first Act of Supremacy was a piece of legislation that granted King Henry VIII of England Royal Supremacy, which means that he was declared the supreme head of the Church of England. It is still the legal authority of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom...

) such as Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

. Along with poor economic conditions, the attack on the Church led to an explosion of anger in Devon and Cornwall, initiating an uprising. In response, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG, Earl Marshal was Lord Protector of England in the period between the death of Henry VIII in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549....

, was sent with an army composed partly of German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

and Italian mercenaries to suppress the revolt.

In June 2007 the Bishop of Truro

Bishop of Truro

The Bishop of Truro is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Truro in the Province of Canterbury.The present diocese covers the county of Cornwall and it is one of the most recently created dioceses of the Church of England...

, the Right Reverend Bill Ind

Bill Ind

William "Bill" Ind is a retired English Anglican bishop. He was formerly the Bishop of Truro.The son of William Robert Ind and Florence Emily Spritey, Ind was educated at the Duke of York's School in Dover, at the University of Leeds, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in history in 1964...

, described the Church of England's role in the massacre of thousands of Catholic rebels during the suppression of the Prayer Book rebellion as an "enormous mistake".

Causes

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

—he was nine years old when he acceded to the throne in 1547— introduced a range of legislative measures as an extension of the Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, the primary aim being to change theology and practices of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

along Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

lines.

In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

, reflecting the theology of Protestantism while keeping much of the appearance of the old rites, replaced, in English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

, the four old liturgical book

Liturgical book

A liturgical book is a book published by the authority of a church, that contains the text and directions for the liturgy of its official religious services.-Roman Catholic:...

s in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

. The change was unpopular, particularly in areas of traditionally Roman Catholic religious loyalty, for example, in Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

and Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

.

It is possible that the roots of the rebellion can - in part - be traced back to the Cornish Rebellion of 1497

Cornish Rebellion of 1497

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 was a popular uprising by the people of Cornwall in the far southwest of Britain. Its primary cause was a response of people to the raising of war taxes by King Henry VII on the impoverished Cornish, to raise money for a campaign against Scotland motivated by brief...

and the subsequent destruction of monasteries

Monastery

Monastery denotes the building, or complex of buildings, that houses a room reserved for prayer as well as the domestic quarters and workplace of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in community or alone .Monasteries may vary greatly in size – a small dwelling accommodating only...

from 1536 through to 1545 under king Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

which brought an end to the formal scholarship, supported by the monastic orders

Religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practice. The order is composed of initiates and, in some...

, that had sustained the Cornish and Devonian cultural identities. The dissolution of Glasney College

Glasney College

Glasney College was founded in 1265 at Penryn, Cornwall, by Bishop Bronescombe and was a centre of ecclesiastical power in medieval Cornwall and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions.-History:...

and Crantock

Crantock

Crantock is a coastal civil parish and a village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is approximately two miles southwest of Newquay....

College played a significant part in fomenting opposition to future cultural reforms. Scholars like Stoyle have argued that the Catholic Church had "proved itself extremely accommodating of Cornish language and culture" and that government attacks on the traditional religion had reawakened the spirit of defiance in Cornwall, and in particular the majority Cornish-speaking far west.

When traditional religious procession

Procession

A procession is an organized body of people advancing in a formal or ceremonial manner.-Procession elements:...

s and pilgrimage

Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey or search of great moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith...

s were banned, commissioners were sent out to remove all symbols of Catholicism, in line with Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

's religious policies favouring Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

ever more. In Cornwall, this task was given to William Body, whose perceived desecration of religious shrine

Shrine

A shrine is a holy or sacred place, which is dedicated to a specific deity, ancestor, hero, martyr, saint, daemon or similar figure of awe and respect, at which they are venerated or worshipped. Shrines often contain idols, relics, or other such objects associated with the figure being venerated....

s led to his murder on April 5, 1548, by William Kylter and Pascoe Trevian at Helston

Helston

Helston is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated at the northern end of the Lizard Peninsula approximately 12 miles east of Penzance and nine miles southwest of Falmouth. Helston is the most southerly town in the UK and is around further south than...

.

Immediate retribution followed with the execution of twenty eight Cornishmen at Launceston Castle

Launceston Castle

Launceston Castle is located in the town of Launceston, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. .-Early history:The castle is a Norman motte and bailey earthwork castle raised by Robert, Count of Mortain, half-brother of William the Conqueror shortly after the Norman conquest, possibly as early as 1067...

. One execution of a "traitor of Cornwall" occurred on Plymouth Hoe

Plymouth Hoe

Plymouth Hoe, referred to locally as the Hoe, is a large south facing open public space in the English coastal city of Plymouth. The Hoe is adjacent to and above the low limestone cliffs that form the seafront and it commands views of Plymouth Sound, Drake's Island, and across the Hamoaze to Mount...

— town accounts give details of the cost of timber for both gallows and poles. Martin Geoffrey, the pro-Catholic priest of St Keverne

St Keverne

St Keverne is a civil parish and village on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom.The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 started in St Keverne. The leader of the rebellion Michael An Gof was a blacksmith from St Keverne and is commemorated by a statue in the village...

, near Helston, was taken to London. After execution his head was impaled on a staff erected upon London Bridge as was customary.

Sampford Courtenay and the immediate beginnings of the uprising

Act of Uniformity 1549

The Act of Uniformity 1549 established The Book of Common Prayer as the sole legal form of worship in England...

made it unlawful to use the Latin liturgical rites

Latin liturgical rites

Latin liturgical rites used within that area of the Catholic Church where the Latin language once dominated were for many centuries no less numerous than the liturgical rites of the Eastern autonomous particular Churches. Their number is now much reduced...

from Whitsunday

Whitsunday

Whitsunday may be:Days:* The Sunday of the feast of Whitsun or Pentecost in the Christian liturgical year, observed 7 weeks after Easter* One of the Scottish quarter days, always falling on 15 MayPlaces:* The Electoral district of Whitsunday...

1549 onwards. Magistrate

Magistrate

A magistrate is an officer of the state; in modern usage the term usually refers to a judge or prosecutor. This was not always the case; in ancient Rome, a magistratus was one of the highest government officers and possessed both judicial and executive powers. Today, in common law systems, a...

s were given the task of enforcing the change. Following the enforced change on Whitsunday, on Whitmonday the parishioners of Sampford Courtenay

Sampford Courtenay

Sampford Courtenay is a village and civil parish in West Devon in England, most famous for being the place where the Western Rebellion, otherwise known as the Prayerbook rebellion, first started, and where the rebels made their final stand...

in Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

compelled their priest to revert to the old service. The rebels argued that the new English liturgy was "but lyke a Christmas game." This claim was probably related to the book's provision for men and women to file into the quire on different sides in order to receive the sacrament, which seemed to remind the Devon men of country dancing. Justices arrived at the next service to enforce the change. An altercation at the service led to a proponent of the change (William Hellyons) being killed by being run through with a pitchfork

Pitchfork

A pitchfork is an agricultural tool with a long handle and long, thin, widely separated pointed tines used to lift and pitch loose material, such as hay, leaves, grapes, dung or other agricultural materials. Pitchforks typically have two or three tines...

on the steps of the church house.

Following this confrontation a group of parishioners from Sampford Courtenay decided to march to Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

to protest at the introduction of the new prayer book. As the group of rebels moved through Devon they gained large numbers of Catholic supporters and became a significant force. Marching east to Crediton

Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter. It has a population of 6,837...

, the Devon rebels laid siege to Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

, demanding the withdrawal of all English liturgies. Although a number of the inhabitants in Exeter sent a message of support to the rebels, the city refused to open its gates. The gates were to stay closed because of the siege for over a month.

"Kill all the gentlemen"

Enclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is the process which ends traditional rights such as mowing meadows for hay, or grazing livestock on common land. Once enclosed, these uses of the land become restricted to the owner, and it ceases to be common land. In England and Wales the term is also used for the...

of common lands, the attack on the Church, which was felt to be central to the rural community, led to an explosion of anger. In Cornwall, an army gathered at the town of Bodmin under the leadership of its mayor, Henry Bray, and two staunch Catholic landowners, Sir Humphrey Arundell

Humphrey Arundell

Sir Humphrey Arundell was the leader of Cornish forces in the Prayer Book Rebellion early in the reign of King Edward VI. He was executed at Tyburn, London after the rebellion had been defeated.-Life:...

of Helland

Helland

Helland is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated 2½ miles north of Bodmin. The meaning of the name Helland is unclear: it is possible that the origin is in Cornish hen & lan...

and John Winslade of Tregarrick.

Many of the gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

sought protection in old castles. Some shut themselves in St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount is a tidal island located off the Mount's Bay coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is a civil parish and is united with the town of Marazion by a man-made causeway of granite setts, passable between mid-tide and low water....

where they were besieged by the rebels, who started a bewildering smoke-screen by burning trusses of hay. This, combined with a shortage of food and the distress of their women, forced them to surrender. Sir Richard Grenville found refuge in the ruins of Trematon Castle

Trematon Castle

Trematon Castle is situated near Saltash in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is similar in style to the later Restormel Castle, with a 12th century keep. Trematon Castle overlooks Plymouth Sound and was built probably by Robert, Count of Mortain on the ruins of an earlier Roman fort: it is a...

. Deserted by many of his followers, the old man was enticed outside to parley

Parley

Parley is a discussion or conference, especially one between enemies over terms of a truce or other matters. The root of the word parley is parler, which is the French verb "to speak"; specifically the conjugation parlez "you speak", whether as imperative or indicative.Beginning in the High Middle...

. He was seized and the castle ransacked. Sir Richard and his companions were imprisoned in Launceston gaol. The Cornish army then proceeded to march east across the Tamar

River Tamar

The Tamar is a river in South West England, that forms most of the border between Devon and Cornwall . It is one of several British rivers whose ancient name is assumed to be derived from a prehistoric river word apparently meaning "dark flowing" and which it shares with the River Thames.The...

border into Devon to join with the Devon rebels near Crediton.

The slogan "Kill all the gentlemen and we will have the Six Articles up again and ceremonies as they were in King Henry

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

's time" highlights the religious aims of the rebellion. However, it also implies a social cause (a view supported by historians such as Guy and Fletcher). That later demands included limiting the size of households belonging to the gentry — theoretically beneficial in a time of population growth and unemployment — possibly suggests an attack on the prestige of the gentry. Certainly such contemporaries as Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

took this view, condemning the rebels for deliberately inciting a class conflict by their demands: "to diminish their strength and to take away their friends, that you might command gentlemen at your pleasures". Protector Somerset himself saw dislike of the gentry as a common factor in all of the 1549 rebellions: "indeed all hath conceived a wonderful hate against the gentlemen and taketh them all as their enemies."

The Cornish rebels were also concerned with the use of the English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

in the new prayer book. The language-map of Cornwall at this time is quite complicated, but philological studies have suggested that the Cornish language had been in territorial retreat throughout the Middle Ages. Summarising these researches, Stoyle says that by 1450, the county was divided into three main linguistic blocs: "West Cornwall was inhabited by a population of Celtic descent, which was mostly Cornish speaking; the western part of East Cornwall was inhabited by a population of Celtic descent, which had largely abandoned the Cornish tongue in favor of English; and the eastern part of East Cornwall was inhabited by a population of Anglo-Saxon descent, which was entirely English speaking."

In any case, the West Cornish reacted badly to the introduction of English in the 1549 services. The eighth Article of the Demands of the Western Rebels states: "and so we the Cornyshe men (whereof certen of us understande no Englysh) utterly refuse thys newe English". Responding to this, however, the Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG, Earl Marshal was Lord Protector of England in the period between the death of Henry VIII in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549....

asked why the Cornishmen should be offended by holding the service in English rather than Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

, when they had before held it in Latin and not understood that.

Confrontations

In LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, King Edward VI

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

and his Privy Council

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

became alarmed by this news from the West Country. On instructions from the Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

the Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset is a title in the peerage of England that has been created several times. Derived from Somerset, it is particularly associated with two families; the Beauforts who held the title from the creation of 1448 and the Seymours, from the creation of 1547 and in whose name the title is...

, one of the Privy Councillors, Sir Gawain Carew, was ordered to pacify the rebels. At the same time Lord John Russell was ordered to take an army, including German and Italian mercenaries, and impose a military solution.

The rebels were of many different backgrounds, some farmers, some tin miners, and some fishermen. Cornwall appears to have had a significantly larger militia than other areas of a similar size.

Crediton confrontation

After the rebels passed PlymouthPlymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

, Devonian knights Sir Gawain and Sir Peter Carew

Peter Carew

Sir Peter Carew was an English adventurer, who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth of England and took part in the Tudor conquest of Ireland.He is to be distinguished from another Sir Peter Carew Sir Peter Carew (1514? – 27 November 1575) was an English adventurer, who served during the...

, were sent to negotiate, meeting the Devon rebels at Crediton

Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter. It has a population of 6,837...

. They found the approaches blocked and were attacked by longbowmen. Shortly afterward the Cornish rebels arrived and Arundell now divided his combined force, sending one force to Clyst St Mary

Clyst St Mary

Clyst St Mary is a small village and civil parish east of Exeter on the main roads to Exmouth and Sidmouth in East Devon. The name comes from the Celtic word clyst meaning 'clear stream'.-Description:...

to assist the villagers, with the main army advancing upon Exeter, where it besieged the city for 5 weeks.

The Siege of Exeter

The rebel commanders unsuccessfully tried to persuade John Blackaller, ExeterExeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

's pro-Catholic mayor, to surrender the town. The city gates were closed as the initial force of some 2,000 gathered outside.

Battle of Fenny Bridges

On 2 July Lord John Russell, 1st Earl of BedfordJohn Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford

John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, KG, PC, JP was an English royal minister in the Tudor era. He served variously as Lord High Admiral and Lord Privy Seal....

's initial force had reached Honiton. It included 160 Italian arquebusiers and a thousand landsknecht

Landsknecht

Landsknechte were European, predominantly German mercenary pikemen and supporting foot soldiers from the late 15th to the late 16th century, and achieved the reputation for being the universal mercenary of Early modern Europe.-Etymology:The term is from German, Land "land, country" + Knecht...

s, German footsoldiers, under the command of Lord William Grey

William Grey, 13th Baron Grey de Wilton

William Grey, 13th Baron Grey de Wilton KG, was an English baron and military commander serving in France in the 1540s and 1550s, and in the Scottish wars of the 1540s.He was the thirteenth Baron Grey de Wilton....

. With promised reinforcements from Wiltshire

Wiltshire

Wiltshire is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. It contains the unitary authority of Swindon and covers...

and Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn, and the entire Forest of Dean....

, Russell would have more than 8,600 men, including a cavalry force of 850 men, all of them well armed and well trained. Russell had estimated the combined rebel forces from Cornwall and Devon at only 7,000 men. On 28 July Arundell decided to block their approach to Exeter at Fenny Bridges. The result of this conflict was inconclusive and around 300 on each side were reported to have died with Lord Russell and his army returning to Honiton.

Battle of Woodbury Common

Lord Russell’s reinforcements arrived on 2 August and his army of 5000 men began a march upon Exeter, westward, across the downs. Russell’s advance continued on to Woodbury CommonWoodbury Common

Woodbury Common may refer to:* Woodbury Common, Devon, an area of common land near Woodbury, Devon* Woodbury Common Premium Outlets, an outlet center near Central Valley, New York...

where they pitched camp. On 4 August the rebels attacked but the result was inconclusive with large numbers of prisoners taken by Lord Russell.

Battle of Clyst St Mary

Arundell's forces re-grouped with the main contingent of 6,000 at Clyst St MaryClyst St Mary

Clyst St Mary is a small village and civil parish east of Exeter on the main roads to Exmouth and Sidmouth in East Devon. The name comes from the Celtic word clyst meaning 'clear stream'.-Description:...

, but on 5 August were attacked by a central force led by Sir William Francis. After a ferocious battle Russell's troops gained the advantage leaving a thousand Cornish and Devonians dead and many more taken prisoner.

Clyst Heath massacre

Russell pitched camp on Clyst HeathClyst Heath

Clyst Heath is a suburb to the south east of Exeter, Devon, to the east of Rydon Lane.On 5 August 1549 Clyst Heath was the site of one of the worst atrocities in British history during the Prayer Book Rebellion when troops loyal to the King under the command of John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford...

and it was here that 900 bound and gagged prisoners had their throats slit in 10 minutes according to the chronicler John Hayward

John Hayward

Sir John Hayward , English historian, was born at or near Felixstowe, Suffolk, where he was educated, and afterwards proceeded to Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he took the degrees of B.A., M.A. and LL.D....

.

Battle of Clyst Heath

When news of the atrocity reached Arundell's forces a new attack took place early on 6 August. Lord Grey was later to comment that he had never seen the like, nor taken part in such a murderous fray. As he had led the charge against the Scots in the Battle of Pinkie CleughBattle of Pinkie Cleugh

The Battle of Pinkie Cleugh, on the banks of the River Esk near Musselburgh, Scotland on 10 September 1547, was part of the War of the Rough Wooing. It was the last pitched battle between Scottish and English armies, and is seen as the first modern battle in the British Isles...

, this was a telling statement. Some 2000 died at the battle of Clyst Heath. A group of Devon men went north up the valley of the Exe, where they were overtaken by Sir Gawen Carew, who left the corpses of their leaders hanging on gibbets from Dunster to Bath.

Relief of Exeter

Lord Russell continued his attack with the relief of Exeter. In London, a proclamation was issued allowing the lands of those involved in the uprising to be confiscated. Arundell's estates were transferred to Sir Gawen Carew and Sir Peter Carew was rewarded with all of John Wynslade’s Devon estates.Battle of Sampford Courtenay

Lord Russell was under the impression that the Cornish had been defeated but news arrived that Arundell's army was re-grouping at Sampford CourtenaySampford Courtenay

Sampford Courtenay is a village and civil parish in West Devon in England, most famous for being the place where the Western Rebellion, otherwise known as the Prayerbook rebellion, first started, and where the rebels made their final stand...

. This interrupted his plans to send 1,000 men into Cornwall by ship to cut off his enemy’s retreat. Russell's forces were strengthened by the arrival of a force under Provost Marshal Sir Anthony Kingston

Anthony Kingston

Sir Anthony Kingston was an English royal official, holder of various positions under several Tudor monarchs.-Life:He was son of Sir William Kingston of Blackfriars, London...

. His army now numbered more than 8,000, vastly outnumbering what remained of his opposition. Lord Grey and Sir William Herbert led the attack and contemporary Exeter historian John Hooker

John Hooker (English constitutionalist)

John Hooker, John Hoker or John Vowell was an English writer, solicitor, antiquary, civic administrator and advocate of republican government. He wrote an eye-witness account of the siege of Exeter that took place during the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549...

wrote that 'the Cornish would not give in until most of their number had been slain or captured.' Lord John Russell, reported that his army had killed between five and six hundred and his pursuit of the Cornish retreat killed a further seven hundred.

Aftermath

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

the Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset is a title in the peerage of England that has been created several times. Derived from Somerset, it is particularly associated with two families; the Beauforts who held the title from the creation of 1448 and the Seymours, from the creation of 1547 and in whose name the title is...

, and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

for the continuance of the onslaught. Under Sir Anthony Kingston

Anthony Kingston

Sir Anthony Kingston was an English royal official, holder of various positions under several Tudor monarchs.-Life:He was son of Sir William Kingston of Blackfriars, London...

, English and mercenary forces then moved throughout Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

and into Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

and executed or killed many people before the bloodshed finally ceased. Proposals to translate the Prayer Book into Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

were also suppressed.

The loss of life in the prayer book rebellion and subsequent reprisals as well as the introduction of the English prayer book is seen as a turning point in the Cornish language, for which — unlike Welsh

Welsh language

Welsh is a member of the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages spoken natively in Wales, by some along the Welsh border in England, and in Y Wladfa...

— a complete bible translation was not produced. Research has also suggested that prior to the rebellion the Cornish language had strengthened and more concessions had been made to Cornwall as a "nation", and that anti-English sentiment had been growing stronger, providing additional impetus for the rebellion.

Bishop of Truro expresses regret for the brutal response to the Prayer Book Rebellion

In June 2007 the then Bishop of TruroBishop of Truro

The Bishop of Truro is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Truro in the Province of Canterbury.The present diocese covers the county of Cornwall and it is one of the most recently created dioceses of the Church of England...

, The Rt Revd Bill Ind

Bill Ind

William "Bill" Ind is a retired English Anglican bishop. He was formerly the Bishop of Truro.The son of William Robert Ind and Florence Emily Spritey, Ind was educated at the Duke of York's School in Dover, at the University of Leeds, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in history in 1964...

, was reported as saying that the massacre during the vicious suppression of the Cornish Prayerbook rebellion more than 450 years ago was an "enormous mistake" for which the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

should be ashamed. Speaking at a ceremony at Pelynt

Pelynt

Pelynt is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated 20 miles west of Plymouth and four miles west-northwest of Looe. Pelynt has a population of around 1,124 ....

, he said:

"I am often asked about my attitude to the Prayerbook Rebellion and in my opinion, there is no doubt that the English Government behaved brutally and stupidly and killed many Cornish people

Cornish people

The Cornish are a people associated with Cornwall, a county and Duchy in the south-west of the United Kingdom that is seen in some respects as distinct from England, having more in common with the other Celtic parts of the United Kingdom such as Wales, as well as with other Celtic nations in Europe...

. I don't think apologising for something that happened over 500 years ago helps, but I am sorry about what happened and I think it was an enormous mistake."

See also

- Pilgrimage of GracePilgrimage of GraceThe Pilgrimage of Grace was a popular rising in York, Yorkshire during 1536, in protest against Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as well as other specific political, social and economic grievances. It was done in action against Thomas Cromwell...

- Religion in the United KingdomReligion in the United KingdomReligion in the United Kingdom and the states that pre-dated the UK, was dominated by forms of Christianity for over 1,400 years. Although a majority of citizens still identify with Christianity in many surveys, regular church attendance has fallen dramatically since the middle of the 20th century,...

- Jenny GeddesJenny GeddesJenny Geddes was a Scottish market-trader in Edinburgh, who is alleged to have thrown her stool at the head of the minister in St Giles' Cathedral in objection to the first public use of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer in Scotland.The act is reputed to have sparked the riot which led to the...

, precipitator of a later rebellion in Scotland leading to the Wars of the Three KingdomsWars of the Three KingdomsThe Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

including the English Civil WarEnglish Civil WarThe English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists... - List of topics related to Devon

- List of topics related to Cornwall

Primary sources

- Holinshed, Raphael (1586) The ... Chronicles, comprising the description and historie of England, the description and historie of Ireland, the description and historie of Scotland; first collected and published by Raphaell Holinshed, William Harrison, and others. Now newlie augmented and continued (with manifold matters of singular note and worthie memorie) to the yeare 1586 by John Hooker, alias Vowell Gent, and others. 3 vols. London: John Harrison, 1586-87 (includes an account of the rebellion by John Hooker)

- John HookerJohn Hooker (English constitutionalist)John Hooker, John Hoker or John Vowell was an English writer, solicitor, antiquary, civic administrator and advocate of republican government. He wrote an eye-witness account of the siege of Exeter that took place during the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549...

, Description of the citie of Excester, ed. Walter J. Harte, J. W. Schopp and H. Tapley-Soper, (Devon and Cornwall Record Society Publications, vol. 11), 3 pts., Exeter: Devon and Cornwall Record Society, 1919–1947 - Nicholas Pocock, (ed.), Troubles connected with the Prayer Book of 1549, Camden SocietyCamden SocietyThe Camden Society, named after the English antiquary and historian William Camden, was founded in 1838 in London to publish early historical and literary materials, both unpublished manuscripts and new editions of rare printed books....

, new series, vol. 37, 1884

Secondary sources

- Ian Arthurson, "Fear and loathing in west Cornwall: seven new letters on the 1548 rising," Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, new series II, vol. 3, pts. 3/4, 2000, pp. 97–111

- Margaret Aston, "Segregation in church," in: W. J. Sheils and Diana Wood, (eds.), Women in the Church, (Studies in Church History, 27), Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990, pp. 242–281

- Julian Cornwall, The Revolt of the Peasantry, 1549, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977

- A. H. Couratin, "The Holy Communion, 1549," Church Quarterly Review, vol. 164, 1963, pp. 148–159

- Eamon DuffyEamon DuffyEamon Duffy is an Irish Professor of the History of Christianity at the University of Cambridge, and former President of Magdalene College....

, The Voices of Morebath: reformation and rebellion in an English village, New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-300-09825-1 - Anthony Fletcher and Diarmaid MacCullochDiarmaid MacCullochDiarmaid Ninian John MacCulloch FBA, FSA, FR Hist S is Professor of the History of the Church at the University of Oxford and Fellow of St Cross College, Oxford...

, Tudor Rebellions, 5th ed., Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2004 (pp. 52–64). ISBN 0-582-77285-0 - Diarmaid MacCullochDiarmaid MacCullochDiarmaid Ninian John MacCulloch FBA, FSA, FR Hist S is Professor of the History of the Church at the University of Oxford and Fellow of St Cross College, Oxford...

, Thomas Cranmer: a life, New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, 1996 (pp. 429–432, 438-440). ISBN 0-300-07448-4 - Roger B. Manning, "Violence and social conflict in mid-Tudor rebellions," Journal of British Studies, vol. 16, 1977, pp. 18–40

- Joanna Mattingly, "The Helston Shoemakers Guild and a possible connection with the 1549 rebellion," Cornish Studies, vol. 6, 1998, pp. 23–45

- Frances Rose-Troup, The western rebellion of 1549: an account of the insurrections in Devonshire and Cornwall against religious innovations in the reign of Edward VI, London: Smith, Elder, 1913

- Mark Stoyle, "The dissidence of despair: rebellion and identity in early modern Cornwall," Journal of British Studies, vol. 38, 1999, pp. 423–444

- Valdo Vinay, "Riformatori e lotte contadine: scritti e polemiche relative alla ribellione dei contadini nella Cornovaglia e nel Devonshire sotto Edoardo VI," Revista di storia e letteratura religiosa, vol. 3, 1967, pp. 203–251 (in Italian)

- Joyce Youings, "The south-western rebellion of 1549," Southern History, vol. 1, 1979, pp. 99–122

External links

- 1549 Prayer Book Rebellion

- Prayer Book Rebellion March

- The Prayerbook Rebellion - Etched in Devon's memories

- The Western Rebellion in Devon

- Keskerdh Kernow 500

- Prayer Book Rebellion

- 1497 and 1549 Rebellions

- Britain's radical past

- Lyver Pysadow Kemyn (1980) Portions of the Book of Common Prayer in Cornish