Papal infallibility

Encyclopedia

Papal infallibility is a dogma

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

of the Catholic Church which states that, by action of the Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit (Christianity)

For the majority of Christians, the Holy Spirit is the third person of the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and is Almighty God...

, the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

is preserved from even the possibility of error when in his official capacity he solemnly declares or promulgates

Promulgation

Promulgation is the act of formally proclaiming or declaring a new statutory or administrative law after its enactment. In some jurisdictions this additional step is necessary before the law can take effect....

to the universal Church a dogmatic teaching on faith or morals. It is also taught that the Holy Spirit works in the body of the Church, as sensus fidelium

Sensus fidelium

The concept of sensus fidelium in Roman Catholic teachings can be implicitly traced back to the early Fathers of the Church...

, to ensure that dogmatic teachings proclaimed to be infallible will be received by all Catholics. This dogma, however, does not state either that the Pope cannot sin

Sin

In religion, sin is the violation or deviation of an eternal divine law or standard. The term sin may also refer to the state of having committed such a violation. Christians believe the moral code of conduct is decreed by God In religion, sin (also called peccancy) is the violation or deviation...

in his own personal life or that he is necessarily free of error, even when speaking in his official capacity, outside the specific contexts in which the dogma applies.

This doctrine was defined dogmatically

Dogmatic definition

In Catholicism, a dogmatic definition is an extraordinary infallible statement published by a pope or an ecumenical council concerning a matter of faith or morals, the belief in which the Catholic Church requires of all Christians .The term most often refers to the infallible...

in the First Vatican Council

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This twentieth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, held three centuries after the Council of Trent, opened on 8 December 1869 and adjourned...

of 1870. According to Catholic theology, there are several concepts important to the understanding of infallible, divine revelation: Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition

Sacred Tradition

Sacred Tradition or Holy Tradition is a theological term used in some Christian traditions, primarily in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox traditions, to refer to the fundamental basis of church authority....

, and the Sacred Magisterium

Magisterium

In the Catholic Church the Magisterium is the teaching authority of the Church. This authority is understood to be embodied in the episcopacy, which is the aggregation of the current bishops of the Church in union with the Pope, led by the Bishop of Rome , who has authority over the bishops,...

. The infallible teachings of the Pope are part of the Sacred Magisterium, which also consists of ecumenical councils and the "ordinary and universal magisterium". In Catholic theology, papal infallibility is one of the channels of the infallibility of the Church

Infallibility of the Church

The Infallibility of the Church is the belief that the Holy Spirit will not allow the Church to err in its belief or teaching under certain circumstances...

. The infallible teachings of the Pope must be based on, or at least not contradict, Sacred Tradition or Sacred Scripture. Papal infallibility does not signify that the Pope is impeccable

Impeccability

Impeccability is the absence of sin. Christianity believes this to be an attribute of God the Father and therefore also an attribute of Christ....

, i.e.., that he is specially exempt from liability to sin

Sin

In religion, sin is the violation or deviation of an eternal divine law or standard. The term sin may also refer to the state of having committed such a violation. Christians believe the moral code of conduct is decreed by God In religion, sin (also called peccancy) is the violation or deviation...

.

The doctrine of infallibility relies on the other Catholic dogma of petrine supremacy

Papal supremacy

Papal supremacy refers to the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church that the pope, by reason of his office as Vicar of Christ and as pastor of the entire Christian Church, has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered: that, in brief,...

of the Pope, and his authority to be the ruling agent in deciding what will be accepted as formal beliefs in the Church. The clearest example (though not the only one) of the use of this power ex cathedra since the solemn declaration of Papal Infallibility by Vatican I on July 18, 1870, took place in 1950 when Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII

The Venerable Pope Pius XII , born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli , reigned as Pope, head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of Vatican City State, from 2 March 1939 until his death in 1958....

defined the Assumption of Mary

Assumption of Mary

According to the belief of Christians of the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and parts of the Anglican Communion and Continuing Anglicanism, the Assumption of Mary was the bodily taking up of the Virgin Mary into Heaven at the end of her life...

as being an article of faith for Roman Catholics. This authority is considered by Catholics to be apostolic and of divine origin. Prior to the solemn definition of 1870, Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX

Blessed Pope Pius IX , born Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, was the longest-reigning elected Pope in the history of the Catholic Church, serving from 16 June 1846 until his death, a period of nearly 32 years. During his pontificate, he convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, which decreed papal...

in the Papal constitution Ineffabilis Deus

Ineffabilis Deus

Ineffabilis Deus is the name of a Papal bull by Pope Pius IX. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary...

of 1854 had spoken ex cathedra.

Conditions for teachings being declared infallible

Statements by a pope which exercise papal infallibility are referred to as "solemn papal definitions" or ex cathedra teachings. Also considered infallible are the teachings of the whole body of bishops of the Church, especially but not only in an ecumenical councilEcumenical council

An ecumenical council is a conference of ecclesiastical dignitaries and theological experts convened to discuss and settle matters of Church doctrine and practice....

(see Infallibility of the Church

Infallibility of the Church

The Infallibility of the Church is the belief that the Holy Spirit will not allow the Church to err in its belief or teaching under certain circumstances...

).

According to the teaching of the First Vatican Council

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This twentieth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, held three centuries after the Council of Trent, opened on 8 December 1869 and adjourned...

and Catholic tradition, the conditions required for ex cathedra papal teaching are as follows:

- 1. "the Roman Pontiff"

- 2. "speaks ex cathedra" ("that is, when in the discharge of his office as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, and by virtue of his supreme apostolic authorityApostle (Christian)The term apostle is derived from Classical Greek ἀπόστολος , meaning one who is sent away, from στέλλω + από . The literal meaning in English is therefore an "emissary", from the Latin mitto + ex...

....") - 3. "he defines"

- 4. "that a doctrine concerning faith or morals"

- 5. "must be held by the whole Church" (Pastor Aeternus, chap. 4).

For a teaching by a pope or ecumenical council to be recognized as infallible, the teaching must be a decision of the supreme teaching authority of the Church (Pope or College of Bishops

College of Bishops

The term "College of Bishops" is used in Catholic theology to denote the bishops in communion with the Pope as a body, not as individuals...

); it must concern a doctrine of faith of morals; it must bind the universal Church; and it must be proposed as something to be held firmly and immutably. The terminology of a definitive decree will usually make clear that this last condition is fulfilled, as through a formula such as "By the authority of Our Lord Jesus Christ and of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and by Our own authority, We declare, pronounce and define the doctrine . . . to be revealed by God and as such to be firmly and immutably held by all the faithful", or through an accompanying anathema

Anathema

Anathema originally meant something lifted up as an offering to the gods; it later evolved to mean:...

stating that anyone who deliberately dissent

Dissent

Dissent is a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or an entity...

s is outside the Catholic Church.

For example, in 1950, with Munificentissimus Deus

Munificentissimus Deus

Munificentissimus Deus is the name of an Apostolic constitution written by Pope Pius XII. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was the first ex-cathedra infallible statement since the official ruling on papal infallibility was made at the First Vatican...

, Pope Pius XII's infallible definition regarding the Assumption of Mary

Assumption of Mary

According to the belief of Christians of the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and parts of the Anglican Communion and Continuing Anglicanism, the Assumption of Mary was the bodily taking up of the Virgin Mary into Heaven at the end of her life...

, there are attached these words:

Hence if anyone, which God forbid, should dare willfully to deny or to call into doubt that which WePluralis majestatisThe majestic plural , is the use of a plural pronoun to refer to a single person holding a high office, such as a monarch, bishop, or pope...

have defined, let him know that he has fallen away completely from the divine and Catholic Faith.

In July 2005 Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI

Benedict XVI is the 265th and current Pope, by virtue of his office of Bishop of Rome, the Sovereign of the Vatican City State and the leader of the Catholic Church as well as the other 22 sui iuris Eastern Catholic Churches in full communion with the Holy See...

stated during an impromptu address to priests in Aosta

Aosta

Aosta is the principal city of the bilingual Aosta Valley in the Italian Alps, north-northwest of Turin. It is situated near the Italian entrance of the Mont Blanc Tunnel, at the confluence of the Buthier and the Dora Baltea, and at the junction of the Great and Little St. Bernard routes...

that: "The Pope is not an oracle; he is infallible in very rare situations, as we know." His predecessor Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII

-Papal election:Following the death of Pope Pius XII in 1958, Roncalli was elected Pope, to his great surprise. He had even arrived in the Vatican with a return train ticket to Venice. Many had considered Giovanni Battista Montini, Archbishop of Milan, a possible candidate, but, although archbishop...

once remarked: "I am only infallible if I speak infallibly but I shall never do that, so I am not infallible." A doctrine proposed by a Pope as his own opinion, not solemnly proclaimed as a doctrine of the Church, may be rejected as false, even if it is on a matter of faith and morals, and even more any view he expresses on other matters. A well-known example of a personal opinion on a matter of faith and morals that was taught by a Pope but rejected by the Church is the view that Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

expressed on when the dead can reach the beatific vision. The limitation on the Pope's infallibility "on other matters" is frequently illustrated by Cardinal James Gibbons's recounting how the Pope mistakenly called him Jibbons.

In general, Catholic theologians hold that the canonization

Canonization

Canonization is the act by which a Christian church declares a deceased person to be a saint, upon which declaration the person is included in the canon, or list, of recognized saints. Originally, individuals were recognized as saints without any formal process...

s of saints by a pope are infallible teaching that the persons canonized are definitely in heaven with God.

Ex cathedra

The "chair" referred to is not a literal chair, but refers metaphorically to the pope's position, or office, as the official teacher of Catholic doctrine: the chair was the symbol of the teacher in the ancient world—the post of university professor is still referred to as "the chair" - and bishops to this day have a cathedra, a seat or throne, as a symbol of their teaching and governing authority. The pope is said to occupy the "chair of Peter", as Catholics hold that among the apostles Peter had a special role as the preserver of unity, so the pope as successor of Peter holds the role of spokesman for the whole church among the bishops, the successors as a group of the apostles. (Also see Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

and sede vacante

Sede vacante

Sede vacante is an expression, used in the Canon Law of the Catholic Church, that refers to the vacancy of the episcopal see of a particular church...

: both terms evoke this seat or throne.)

The response demanded from believers has been characterized as "assent" in the case of ex cathedra declarations of the popes and "due respect" with regard to their other declarations.

Scriptural support for the primacy of Peter

Believers of the Catholic doctrine claim that their position is historically traceable to Scripture:- John 1:42, Mark 3:16 ("And to Simon he gave the name "PeterSaint PeterSaint Peter or Simon Peter was an early Christian leader, who is featured prominently in the New Testament Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. The son of John or of Jonah and from the village of Bethsaida in the province of Galilee, his brother Andrew was also an apostle...

", "Cephas", or "Rock") - Matthew 16:18 ("thou art Peter; and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it"; cf. Matthew 7:24-28, (the house built on rock)

- Luke 10:16 ("He that heareth you, heareth me; and he that despiseth you, despiseth me; and he that despiseth me, despiseth him that sent me.")

- Acts 15:28 ("For it hath seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to us, ...") ("the Apostles speak with voice of Holy Ghost")

- Matthew 10:2 ("And the names of the twelve apostles are these: The first, Simon who is called Peter,...") (Peter is first.)

- Catholic theologian Ludwig OttLudwig OttLudwig Ott was a Catholic theologian and Medievalist from Bavaria....

points to several Scriptures which he believes show that the Apostle Peter was given a primary role with respect to the other Apostles: Mark 5:37, Matthew 17:1, Matthew 26:37, Luke 5:3, Matthew 17:27, Luke 22:32, Luke 24:34, and 1 Corinthians 15:5.

Primacy of the Roman Pontiff

The doctrine of the Primacy of the Roman Bishops, like other Church teachings and institutions, has gone through a development. Thus the establishment of the Primacy recorded in the Gospels has gradually been more clearly recognised and its implications developed. Clear indications of the consciousness of the Primacy of the Roman bishops, and of the recognition of the Primacy by the other churches appear at the end of the 1st century. L. Ott

Pope St. Clement of Rome, c. 99, stated in a letter to the Corinth

Corinth

Corinth is a city and former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Corinth, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

ians: "Indeed you will give joy and gladness to us, if having become obedient to what we have written through the Holy Spirit, you will cut out the unlawful application of your zeal according to the exhortation which we have made in this epistle concerning peace and union" (Denziger §41, emphasis added).

St. Clement of Alexandria

Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens , known as Clement of Alexandria , was a Christian theologian and the head of the noted Catechetical School of Alexandria. Clement is best remembered as the teacher of Origen...

wrote on the primacy of Peter c. 200: "...the blessed Peter, the chosen, the pre-eminent, the first among the disciples, for whom alone with Himself the Savior paid the tribute..." (Jurgens §436).

The existence of an ecclesiastical hierarchy is emphasized by St. Stephan I, 251, in a letter to the bishop of Antioch: "Therefore did not that famous defender of the Gospel [Novatian] know that there ought to be one bishop in the Catholic Church [of the city of Rome]? It did not lie hidden from him..." (Denziger §45).

St. Julius I, in 341 wrote to the Antiochenes: "Or do you not know that it is the custom to write to us first, and that here what is just is decided?" (Denziger §57a, emphasis added).

Catholicism holds that an understanding among the Apostles was written down in what became the Scriptures, and rapidly became the living custom of the Church, and that from there, a clearer theology could unfold.

St. Siricius wrote to Himerius

Himerius

Himerius , Greek sophist and rhetorician. 24 of his orations have reached us complete, and fragments of 12 others.- Life and works :...

in 385: "To your inquiry we do not deny a legal reply, because we, upon whom greater zeal for the Christian religion is incumbent than upon the whole body, out of consideration for our office do not have the liberty to dissimulate, nor to remain silent. We carry the weight of all who are burdened; nay rather the blessed apostle PETER bears these in us, who, as we trust, protects us in all matters of his administration, and guards his heirs" (Denziger §87, emphasis in original).

Many of the Church Fathers

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were early and influential theologians, eminent Christian teachers and great bishops. Their scholarly works were used as a precedent for centuries to come...

spoke of ecumenical councils and the Bishop of Rome as possessing a reliable authority to teach the content of Scripture and tradition, albeit without a divine guarantee of protection from error.

Theological history

Klaus Schatz asserts that "it is impossible to fix a single author or era as the starting point" for the doctrine of papal infallibility. Others such as Brian Tierney have argued that the doctrine of papal infallibility was first proposed by Peter Olivi in the Middle AgesMiddle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

. Schatz and others see the roots of the doctrine as going much further back to the early days of Christianity.

Brian Tierney argued that the Franciscan priest Peter Olivi

Peter Olivi

Peter John Olivi, in his native French Pierre Jean Olivi and also Pierre Déjean, was a Franciscan theologian who, although he died professing the faith of the Roman Catholic Church, became a controversial figure in the arguments surrounding poverty at the beginning of the fourteenth century...

was the first person to attribute infallibility to the Pope. His idea was accepted by August Bernhard Hasler, and by Gregory Lee Jackson, It was rejected by James Heft, and by John V. Kruse. Klaus Schatz says Olivi by no means played the key role assigned to him by Tierney, who failed to acknowledge the work of earlier canonists and theologians, and that the crucial advance in the teaching came only in the 15th century, two centuries after Olivi; and he declares that "it is impossible to fix a single author or era as the starting point". Ulrich Horst criticized the Tierney view for the same reasons. In his Protestant evaluation of the ecumenical issue of papal infallibility, Mark E. Powell rejects Tierney's theory about 13th-century Olivi, saying that the doctrine of papal infallibility defined at Vatican I had its origins in the 14th century—he refers in particular to Bishop Guido Terreni—and was itself part of a long development of papal claims.

Schatz points to "the special esteem given to the Roman church community (that) was always associated with fidelity in the faith and preservation of the paradosis (the faith as handed down)." Schatz differentiates between the later doctrine of "infallibility of the papal magisterium" and the Hormisdas formula in 519 which asserted that "the Roman church has never erred (and will never err)." He emphasizes that Hormisdas formula was not meant to apply so much to "individual dogmatic definitions but to the whole of the faith as handed down and the tradition of Peter preserved intact by the Roman Church." Specifically, Schatz argues that the Hormisdas formula does not exclude the possibility of individual popes become heretics because the formula refers "primarily to the Roman tradition as such and not exclusively to the person of the pope."

Ecumenical councils

The first theologian to systematically discuss the infallibility of ecumenical councils was Theodore Abu-QurrahTheodore Abu-Qurrah

Theodore Abū Qurrah was a 9th century Christian Arab theologian who lived in the early Islamic period.Biography=He was born around 750 AD in the city of Edessa, in northern Mesopotamia, and was the Chalcedonian or Melkite bishop of the nearby city of Harran between 795 and 812...

in the 9th century. The 12th-century Decretum Gratiani

Decretum Gratiani

The Decretum Gratiani or Concordia discordantium canonum is a collection of Canon law compiled and written in the 12th century as a legal textbook by the jurist known as Gratian. It forms the first part of the collection of six legal texts, which together became known as the Corpus Juris Canonici...

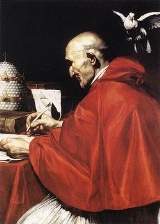

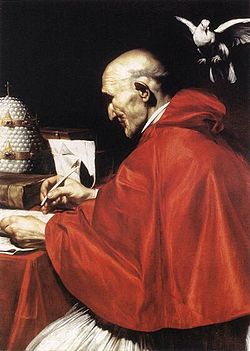

contained the declaration by Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I , better known in English as Gregory the Great, was pope from 3 September 590 until his death...

(540-604) that the first four ecumenical councils were to be revered "like the four gospels", because they had been "established by universal consent", and also Gratian's

Gratian (jurist)

Gratian, was a 12th century canon lawyer from Bologna. He is sometimes incorrectly referred to as Franciscus Gratianus, Johannes Gratianus, or Giovanni Graziano. The dates of his birth and death are unknown....

assertion that "the holy Roman Church imparts authority to the sacred canons but is not bound by them". Commentators on the Decretum, known as the Decretist

Decretist

In the history of canon law, a decretist was student and interpreter of the Decretum Gratiani. Like Gratian, the decretists sought to provide "a harmony of discordant canons" , and they worked towards this through glosses and summaries on Gratian...

s, generally concluded that a pope could change the disciplinary decrees of the ecumenical councils but was bound by their pronouncements on articles of faith, in which field the authority of a general council was higher than that of an individual pope. Unlike those who propounded the 15th-century Conciliarist

Conciliarism

Conciliarism, or the conciliar movement, was a reform movement in the 14th, 15th and 16th century Roman Catholic Church which held that final authority in spiritual matters resided with the Roman Church as a corporation of Christians, embodied by a general church council, not with the pope...

theories, they understood an ecumenical council as necessarily involving the Pope, and meant that the Pope plus the other bishops was greater than a pope acting alone.

Middle Ages

Several medieval theologians discussed the infallibility of the pope when defining matters of faith and morals, including Thomas AquinasThomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

.

The Dictatus papae

Dictatus papae

Dictatus papae is a compilation of 27 axiomatic statements of powers arrogated to the Pope that was included in Pope Gregory VII's register under the year 1075. Some historians argue that it was written by Gregory VII himself; others argue that it has been inserted in the register at a later...

have been attributed to Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII

Pope St. Gregory VII , born Hildebrand of Sovana , was Pope from April 22, 1073, until his death. One of the great reforming popes, he is perhaps best known for the part he played in the Investiture Controversy, his dispute with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor affirming the primacy of the papal...

(1073-1085) in the year 1075, but some have argued that they are later than 1087. They assert that no one can judge the Pope (Proposition 19) and that "the Roman church has never erred; nor will it err to all eternity, the Scripture bearing witness" (Proposition 22). This is seen as a further step in advancing the idea that "had been part of church history and debate as far back as 519 when the notion of the Bishop of Rome as the preserver of apostolic truth was set forth in the Formula of Hormisdas".

In the early years of the 14th century, the Franciscan Order

Franciscan

Most Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

found itself in open conflict about the form of poverty to be observed, with the Spirituals (so called because associated with the Age of the Spirit that Joachim of Fiore

Joachim of Fiore

Joachim of Fiore, also known as Joachim of Flora and in Italian Gioacchino da Fiore , was the founder of the monastic order of San Giovanni in Fiore . He was a mystic, a theologian and an esoterist...

had said would begin in 1260) pitched against the Conventual Franciscans

Conventual Franciscans

The Order of Friars Minor Conventual , commonly known as the Conventual Franciscans, is a branch of the order of Catholic Friars founded by Francis of Assisi in 1209.-History:...

. The Spirituals, who in the 13th century were led by the Joachimist Peter Olivi

Peter Olivi

Peter John Olivi, in his native French Pierre Jean Olivi and also Pierre Déjean, was a Franciscan theologian who, although he died professing the faith of the Roman Catholic Church, became a controversial figure in the arguments surrounding poverty at the beginning of the fourteenth century...

, adopted extremist positions that eventually discredited the notion of apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty is a doctrine professed in the thirteenth century by the newly formed religious orders, known as the mendicant orders, in direct response to calls for reform in the Roman Catholic Church...

and led to its condemnation by Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

. This Pope determined to suppress what he considered to be the excesses of the Spirituals, who contended eagerly for the view that Christ and his apostles had possessed absolutely nothing, either separately or jointly In March 1322, he commissioned experts to examine the idea of poverty based on belief that Christ and the apostles owned nothing. The experts disagreed among themselves, but the majority condemned the idea on the grounds that it would condemn the Church's right to have possessions. The Franciscan chapter held in Perugia

Perugia

Perugia is the capital city of the region of Umbria in central Italy, near the River Tiber, and the capital of the province of Perugia. The city is located about north of Rome. It covers a high hilltop and part of the valleys around the area....

in May 1322 declared on the contrary: "To say or assert that Christ, in showing the way of perfection, and the Apostles, in following that way and setting an example to others who wished to lead the perfect life, possessed nothing either severally or in common, either by right of ownership and dominium or by personal right, we corporately and unanimously declare to be not heretical, but true and catholic." One argument used by them was that John XXII's predecessors had declared the absolute poverty of Christ to be an article of faith and that therefore no pope could declare the contrary. Appeal was made in particular to the 14 August 1279 bull Exiit qui seminat, in which Pope Nicholas III

Pope Nicholas III

Pope Nicholas III , born Giovanni Gaetano Orsini, Pope from November 25, 1277 to his death in 1280, was a Roman nobleman who had served under eight Popes, been made cardinal-deacon of St...

stated that renunciation of ownership of all things "both individually but also in common, for God's sake, is meritorious and holy; Christ, also, showing the way of perfection, taught it by word and confirmed it by example, and the first founders of the Church militant, as they had drawn it from the fountainhead itself, distributed it through the channels of their teaching and life to those wishing to live perfectly".

By the bull Ad conditorem canonum of 8 December of the same year, John XXII, declaring it ridiculous to pretend that every scrap of food given to the friars and eaten by them belonged to the pope, forced them to accept ownership by ending the arrangement according to which all property given to the Franciscans was vested in the Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

, which granted the friars the mere use of it. He thus demolished the fictitious structure that gave the appearance of absolute poverty to the life of the Franciscan friars, a structure that "absolved the Franciscans from the moral burden of legal ownership, and enabled them to practise apostolic poverty without the inconvenience of actual poverty". This document was concerned with disciplinary rather than doctrinal matters, but leaders of the Franciscans reacted with insistence on the irreformability of doctrinal papal decrees, with special reference to Exiit. A year later, John XXII issued the short 12 November 1323 bull Cum inter nonnullos, which declared "erroneous and heretical" the doctrine that Christ and his apostles had no possessions whatever.

The next year, the Pope responded to continued criticisms with the bull Quia quorundam of 10 November 1324, He denied the major premise of an argument of his adversaries, "What the Roman pontiffs have once defined in faith and morals with the key of knowledge stands so immutably that it is not permitted to a successor to revoke it." He declared that there was no contradiction between his own statements and those of his predecessors; that it could not be inferred from the words of the 1279 bull that Christ and the apostles had nothing – "indeed, it can be inferred rather that the Gospel life lived by Christ and the Apostles did not exclude some possessions in common, since living 'without property' does not require that those living thus should have nothing in common"; that there were many things in the Franciscan rule "which Christ neither taught nor confirmed by his example", and that there was neither merit nor truth in pretending Christ and the apostles had no rights in law.

In his book on the First Vatican Council, August Hasler wrote: "John XXII didn't want to hear about his own infallibility. He viewed it as an improper restriction of his rights as a sovereign, and in the bull Qui quorundam (1324) condemned the Franciscan doctrine of papal infallibility as the work of the devil."

Brian Tierney has summed up his view of the part played by John XXII as follows:

"Pope John XXIII strongly resented the imputation of infallibility to his office – or at any rate to his predecessors. The theory of irreformability proposed by his adversaries was a 'pestiferous doctrine', he declared; and at first he seemed inclined to dismiss the whole idea as 'pernicious audacity'. However, through some uncharacteristic streak of caution or through sheer good luck (or bad luck) the actual terms he used in condemning the Franciscan position left a way open for later theologians to re-formulate the doctrine of infallibility in different language."

In 1330, the Carmelite bishop Guido Terreni described the pope's charism of infallibility in terms very similar to those that the First Vatican Council

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This twentieth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, held three centuries after the Council of Trent, opened on 8 December 1869 and adjourned...

was to use in 1870.

Dogmatic definition of 1870

The infallibility of the pope was formally defined in 1870, although the tradition behind this view goes back much further. In the conclusion of the fourth chapter of its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Pastor aeternusPastor aeternus

Pastor aeternus is the incipit of the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ, issued by the First Vatican Council, July 18, 1870. According to The Modern Catholic Dictionary, Pastor aeternus defines four doctrines of the Catholic faith: the apostolic primacy conferred on Peter, the...

, the First Vatican Council

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This twentieth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, held three centuries after the Council of Trent, opened on 8 December 1869 and adjourned...

declared the following, with bishops Aloisio Riccio

Aloisio Riccio

A Sicilian Bishop in the Roman Catholic Church, Monsignor Luigi Aloisio Riccio was one of two to vote against the doctrine of papal infallibility, which received 433 votes in support, in the 1870 First Vatican Council....

and Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald (bishop)

Edward Mary Fitzgerald was an Irish-born prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Bishop of Little Rock from 1867 until his death in 1907.-Biography:...

dissenting:

According to Catholic theology, this is an infallible dogmatic definition

Dogmatic definition

In Catholicism, a dogmatic definition is an extraordinary infallible statement published by a pope or an ecumenical council concerning a matter of faith or morals, the belief in which the Catholic Church requires of all Christians .The term most often refers to the infallible...

by an ecumenical council

Ecumenical council

An ecumenical council is a conference of ecclesiastical dignitaries and theological experts convened to discuss and settle matters of Church doctrine and practice....

. Because the 1870 definition is not seen by Catholics as a creation of the Church, but as the dogmatic revelation of a Truth about the Papal Magisterium, Papal teachings made prior to the 1870 proclamation can, if they meet the criteria set out in the dogmatic definition, be considered infallible. Ineffabilis Deus

Ineffabilis Deus

Ineffabilis Deus is the name of a Papal bull by Pope Pius IX. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary...

is an example of this.

A British Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

, publicly attacked Vatican I, stating that Roman Catholics had "forfeited their moral and mental freedom". He published a pamphlet called The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance

The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance

The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance is an anti-Catholic pamphlet written by British politician William Ewart Gladstone in November 1874.-Outrage about papal infallibility:...

in which he described the Catholic Church as "an Asian monarchy: nothing but one giddy height of despotism, and one dead level of religious subservience". He further claimed that the Pope wanted to destroy the rule of law

Rule of law

The rule of law, sometimes called supremacy of law, is a legal maxim that says that governmental decisions should be made by applying known principles or laws with minimal discretion in their application...

and replace it with arbitrary tyranny, and then to hide these "crimes against liberty beneath a suffocating cloud of incense". Cardinal Newman famously responded with his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk

Letter to the Duke of Norfolk

Letter to the Duke of Norfolk is a book written in 1875 by the blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman. Consisting of about 150 pages, it was meant as a response to Protestant-Catholic polemics that had emerged in the era of the First Vatican Council. In the book, Newman comments on the injustice of...

. In the letter he argues that conscience, which is supreme, is not in conflict with papal infallibility—though he toasts "I shall drink to the Pope if you please--still, to conscience first and to the Pope afterwards". He stated later that “the Vatican Council left the Pope just as it found him”, satisfied that the definition was very moderate, and specific in regards to what specifically can be declared as infallible

Lumen gentium

The dogmatic constitution Lumen gentium of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, which was also a document on the Church itself, explicitly reaffirmed the definition of papal infallibility, so as to avoid any doubts, expressing this in the following words:Instances of declarations of infallibility

The Catholic Church does not teach that the Pope is infallible in everything he says; official invocation of papal infallibility is extremely rare.Catholic theologians agree that both Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX

Blessed Pope Pius IX , born Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, was the longest-reigning elected Pope in the history of the Catholic Church, serving from 16 June 1846 until his death, a period of nearly 32 years. During his pontificate, he convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, which decreed papal...

's 1854 definition

Ineffabilis Deus

Ineffabilis Deus is the name of a Papal bull by Pope Pius IX. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary...

of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception

Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception of Mary is a dogma of the Roman Catholic Church, according to which the Virgin Mary was conceived without any stain of original sin. It is one of the four dogmata in Roman Catholic Mariology...

of Mary and Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII

The Venerable Pope Pius XII , born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli , reigned as Pope, head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of Vatican City State, from 2 March 1939 until his death in 1958....

's 1950 definition

Munificentissimus Deus

Munificentissimus Deus is the name of an Apostolic constitution written by Pope Pius XII. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was the first ex-cathedra infallible statement since the official ruling on papal infallibility was made at the First Vatican...

of the dogma of the Assumption of Mary

Assumption of Mary

According to the belief of Christians of the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and parts of the Anglican Communion and Continuing Anglicanism, the Assumption of Mary was the bodily taking up of the Virgin Mary into Heaven at the end of her life...

are instances of papal infallibility, a fact which has been confirmed by the Church's magisterium. However, theologians disagree about what other documents qualify.

Regarding historical papal documents, Catholic theologian and church historian Klaus Schatz made a thorough study, published in 1985, that identified the following list of ex cathedra documents (see Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting Documents of the Magisterium, by Francis A. Sullivan

Francis A. Sullivan

Francis Aloysius Sullivan, S.J. is an American Catholic theologian and a Jesuit priest. He is best known for his research in the area of ecclesiology and the magisterium.- Early Life and Jesuit Formation :...

, chapter 6):

- "Tome to Flavian", Pope Leo IPope Leo IPope Leo I was pope from September 29, 440 to his death.He was an Italian aristocrat, and is the first pope of the Catholic Church to have been called "the Great". He is perhaps best known for having met Attila the Hun in 452, persuading him to turn back from his invasion of Italy...

, 449, on the two natures in Christ, received by the Council of ChalcedonCouncil of ChalcedonThe Council of Chalcedon was a church council held from 8 October to 1 November, 451 AD, at Chalcedon , on the Asian side of the Bosporus. The council marked a significant turning point in the Christological debates that led to the separation of the church of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 5th...

; - Letter of Pope AgathoPope Agatho-Background and early life:Little is known of Agatho before his papacy. A letter written by St. Gregory the Great to the abbot of St. Hermes in Palermo mentions an Agatho, a Greek born in Sicily to wealthy parents. He wished to give away his inheritance and join a monastery, and in this letter...

, 680, on the two wills of Christ, received by the Third Council of ConstantinopleThird Council of ConstantinopleThe Third Council of Constantinople, counted as the Sixth Ecumenical Council by the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches and other Christian groups, met in 680/681 and condemned monoenergism and monothelitism as heretical and defined Jesus Christ as having two energies and two wills...

; - Benedictus Deus, Pope Benedict XIIPope Benedict XIIPope Benedict XII , born Jacques Fournier, the third of the Avignon Popes, was Pope from 1334 to 1342.-Early life:...

, 1336, on the beatific visionBeatific visionThe beatific vision - in Christian theology is the ultimate direct self communication of God to the individual person, when she or he reaches, as a member of redeemed humanity in the communion of saints, perfect salvation in its entirety, i.e. heaven...

of the just prior to final judgment; - Cum occasione, Pope Innocent XPope Innocent XPope Innocent X , born Giovanni Battista Pamphilj , was Pope from 1644 to 1655. Born in Rome of a family from Gubbio in Umbria who had come to Rome during the pontificate of Pope Innocent IX, he graduated from the Collegio Romano and followed a conventional cursus honorum, following his uncle...

, 1653, condemning five propositions of JansenCornelius JansenCorneille Janssens, commonly known by the Latinized name Cornelius Jansen or Jansenius, was Catholic bishop of Ypres and the father of a theological movement known as Jansenism.-Biography:...

as hereticalChristian heresyChristian heresy refers to non-orthodox practices and beliefs that were deemed to be heretical by one or more of the Christian churches. In Western Christianity, the term "heresy" most commonly refers to those beliefs which were declared to be anathema by the Catholic Church prior to the schism of...

; - Auctorem fidei, Pope Pius VIPope Pius VIPope Pius VI , born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, was Pope from 1775 to 1799.-Early years:Braschi was born in Cesena...

, 1794, condemning seven JansenistJansenismJansenism was a Christian theological movement, primarily in France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. The movement originated from the posthumously published work of the Dutch theologian Cornelius Otto Jansen, who died in 1638...

propositions of the Synod of PistoiaSynod of PistoiaThe Synod of Pistoia was a diocesan synod held in 1786 under the presidency of Scipione de' Ricci , bishop of Pistoia, and the patronage of Leopold, grand-duke of Tuscany, with a view to preparing the ground for a national council and a reform of the Tuscan Church.-Circular letter:On January 26 the...

as heretical; - Ineffabilis Deus, Pope Pius IXPope Pius IXBlessed Pope Pius IX , born Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, was the longest-reigning elected Pope in the history of the Catholic Church, serving from 16 June 1846 until his death, a period of nearly 32 years. During his pontificate, he convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, which decreed papal...

, 1854, defining the Immaculate ConceptionImmaculate ConceptionThe Immaculate Conception of Mary is a dogma of the Roman Catholic Church, according to which the Virgin Mary was conceived without any stain of original sin. It is one of the four dogmata in Roman Catholic Mariology...

; - Munificentissimus Deus, Pope Pius XIIPope Pius XIIThe Venerable Pope Pius XII , born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli , reigned as Pope, head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of Vatican City State, from 2 March 1939 until his death in 1958....

, 1950, defining the Assumption of MaryAssumption of MaryAccording to the belief of Christians of the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and parts of the Anglican Communion and Continuing Anglicanism, the Assumption of Mary was the bodily taking up of the Virgin Mary into Heaven at the end of her life...

.

For modern-day Church documents, there is no need for speculation as to which are officially ex cathedra, because the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith , previously known as the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition , and after 1904 called the Supreme...

can be consulted directly on this question. For example, after Pope John Paul II's

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis

Ordinatio Sacerdotalis

Ordinatio Sacerdotalis is an Apostolic Letter issued from the Vatican by Pope John Paul II on 22 May 1994, whereby the Pope expounds the teaching of the Catholic Church's position requiring "the reservation of priestly ordination to men alone." In its clear proclamation that "the Church has no...

(On Reserving Priestly Ordination

Holy Orders

The term Holy Orders is used by many Christian churches to refer to ordination or to those individuals ordained for a special role or ministry....

to Men Alone) was released in 1994, a few commentators speculated that this might be an exercise of papal infallibility. In response to this confusion, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has unambiguously stated, on at least three separate occasions, that Ordinatio Sacerdotalis

Ordinatio Sacerdotalis

Ordinatio Sacerdotalis is an Apostolic Letter issued from the Vatican by Pope John Paul II on 22 May 1994, whereby the Pope expounds the teaching of the Catholic Church's position requiring "the reservation of priestly ordination to men alone." In its clear proclamation that "the Church has no...

although not an ex cathedra teaching (i.e., although not a teaching of the extraordinary magisterium

Infallibility of the Church

The Infallibility of the Church is the belief that the Holy Spirit will not allow the Church to err in its belief or teaching under certain circumstances...

), is indeed infallible, clarifying that the content of this letter has been taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium.

The Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

itself has given no complete list of papal statements considered to be infallible. A 1998 commentary on Ad Tuendam Fidem issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith , previously known as the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition , and after 1904 called the Supreme...

listed a number of instances of infallible pronouncements by popes and by ecumenical councils, but explicitly stated (at no. 11) that this was not meant to be a complete list.

As well as Popes, ecumenical councils has made pronouncements that the Church considers infallible.

Opposition to the doctrine

In contrast to the Catholic emphasis on papal infallibility, the Orthodox emphasize the infallibility of the ChurchInfallibility of the Church

The Infallibility of the Church is the belief that the Holy Spirit will not allow the Church to err in its belief or teaching under certain circumstances...

as a whole.

Before the definition of the doctrine, which clarified the extent of the inerrancy claimed, papal infallibility was explicitly denied by many Catholic authorities, including a pope, and several catholic universities.

One of the earliest assertions of papal infallibility was made by Franciscan priest Peter Olivi. In 1279 Pope Nicholas III

Pope Nicholas III

Pope Nicholas III , born Giovanni Gaetano Orsini, Pope from November 25, 1277 to his death in 1280, was a Roman nobleman who had served under eight Popes, been made cardinal-deacon of St...

had decided in favor of the Franciscans in the controversy over poverty by holding that communal renunciation of poverty was a possible way to salvation.

Forty years later Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

came to a different conclusion on poverty. The Franciscans, unaware that Olivi had taught a theory of infallibility, appealed that the previous papal decision was irreversible.

August B. Hasler wrote:

Thomas Turley, on the contrary, says that the argument advanced by John Regina of Naples that infallibility was an "ancient teaching of the Church" appears to have been decisive in averting Pope John's condemnation of the idea of the absolute infallibility of the local Roman church. Brian Tierney also says that the actual terms used by Pope John XXII in condemning the position of the Franciscan Spirituals "left a way open for later theologians to re-formulate the doctrine of infallibility in different language"; and that the position formulated in 1330 by Guido Terreni "was closer to the nineteenth century doctrine of papal infallibility than any that had been developed earlier". In fact, it has been said that Terreni "so closely anticipated the doctrine of Vatican I that in the judgment of B.M. Xiberta, the Carmelite scholar who edited [Terreni's] work, 'if he had written it after Vatican I he would have to add or change hardly a single word'."

In the campaign for Catholic emancipation; during the late eighteenth century two declarations in Ireland and, England explicitly denied it. In answer to the question whether the pope is infallible, the Catholic Church in Ireland said that such an idea was a Protestant invention made to discredit Roman Catholics. However the Catholic Church in England acknowledged that some Catholics had in the past believed it. They wished to distance themselves also from blaming the Protestant churches for circulating such untruths about their faith, as well as from what any other Catholic wrongly believed.

The English Declaration (1789) stated...

Catholics in Ireland and then in England stated, in answer to parliamentary inquiries into Catholicism as part of the process of Catholic emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

, that they did not believe that the Pope was infallible,

The opinion of the English remonstrance to Parliament had first been approved by several Catholic universities in Europe. It was sent to the Catholic Universities of Paris, Louvain, Douai, Alcala, Salamanca and Valladolid. This was at the suggestion of Pitt

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

.

Examples of Catholics who before the First Vatican Council disbelieved in papal infallibility are French abbé François-Philippe Mesenguy (1677-1763), who wrote a catechism denying the infallibility of the pope, and the German Felix Blau (1754-1798), who as professor at the University of Mainz criticized infallibility.

An oath taken by Catholics in Ireland from 1793 stated that "it is not an article of the Catholic Faith, neither am I thereby required to believe or profess that the Pope is infallible" This was repeated in a pastoral address to the Catholic clergy and laity in Ireland in 1826, in which their bishops stated that it is "not an article of the Catholic faith, neither are they thereby required to believe that the Pope is infallible".

In 1822, Bishop Baine declared: "In England and Ireland I do not believe that any Catholic maintains the Infallibility of the Pope."

Sparrow-Simpson remarked that "all works reprinted since 1870 have been altered into conformity with Vatican ideas. In some cases the process of reducing to conformity was begun at an earlier date. It is therefore with works printed before 1870 that we are now concerned." He therefore cites editions prior to that date.

In his theological works published in 1829, Professor Delahogue asserted that the doctrine that the Roman Pontiff, even when he speaks ex cathedra, is possessed of the gift of inerrancy or is superior to General Councils may be denied without loss of faith or risk of heresy or schism.

The 1830 edition of Berrington and Kirk's Faith of Catholics stated: "Papal definitions or decrees, in whatever form pronounced, taken exclusively from a General Council or acceptance of the Church, oblige no one under pain of heresy to an interior assent".

The 1860 edition of Keenan's Catechism in use in Catholic schools in England, Scotland and Wales had the following question and answer:

- (Q.) Must not Catholics believe the Pope himself to be infallible?

- (A.) This is a Protestant invention: it is no article of the Catholic faith: no decision of his can oblige under pain of heresy, unless it be received and enforced by the teaching body, that is by the bishops of the Church.

Sparrow-Simpson quotes also from the 1895 revision:

- (Q.) But some Catholics before the Vatican Council denied the Infallibility of the Pope, which was also formerly impugned in this very Catechism.

- (A.) Yes; but they did so under the usual reservation - 'in so far as they could then grasp the mind of the Church, and subject to her future definitions' ...

In 1861, Professor Murray of the major Irish Catholic seminary of Maynooth wrote that those who genuinely deny the infallibility of the Pope "are by no means or only in the least degree (unless indeed some other ground be shown) to be considered alien from the Catholic Faith".

Critical works such as Roman Catholic Opposition to Papal Infallibility (1909) by W. J. Sparrow-Simpson have thus documented opposition to the definition of the dogma during the First Vatican Council even by those who believed in its teaching but felt that defining it was not opportune.

A 1989–1992 survey of Catholics from multiple countries (the United States, Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

, France, Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Japan, Korea

Korea

Korea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

, Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

, Spain and Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

), aged 15 to 25 showed that 36.9% accepted the teaching on "papal infallibility", 36.9% denied it, and 26.2% said they didn't know of it.

Following the first Vatican Council, 1870, dissent, mostly among German, Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

n, and Swiss

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

Catholics, arose over the definition of Papal Infallibility. The dissenters, holding the General Councils of the Church infallible, were unwilling to accept the dogma of Papal Infallibility, and thus a schism

Schism (religion)

A schism , from Greek σχίσμα, skhísma , is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization or movement religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a break of communion between two sections of Christianity that were previously a single body, or to a division within...

arose between them and the Church. Many of these Catholics formed independent communities in schism with Rome, which became known as the Old Catholic Church

Old Catholic Church

The term Old Catholic Church is commonly used to describe a number of Ultrajectine Christian churches that originated with groups that split from the Roman Catholic Church over certain doctrines, most importantly that of Papal Infallibility...

es.

A few present-day Catholics, such as Hans Küng

Hans Küng

Hans Küng is a Swiss Catholic priest, theologian, and prolific author. Since 1995 he has been President of the Foundation for a Global Ethic . Küng is "a Catholic priest in good standing", but the Vatican has rescinded his authority to teach Catholic theology...

, author of Infallible? An Inquiry, and historian Garry Wills

Garry Wills

Garry Wills is a Pulitzer Prize-winning and prolific author, journalist, and historian, specializing in American politics, American political history and ideology and the Roman Catholic Church. Classically trained at a Jesuit high school and two universities, he is proficient in Greek and Latin...

, author ofPapal Sin, refuse to accept papal infallibility as a matter of faith. Küng has been sanctioned by the Church by being excluded from teaching Catholic theology. Brian Tierney agrees with Küng, whom he cites, and concludes: "There is no convincing evidence that papal infallibility formed any part of the theological or canonical tradition of the church before the thirteenth century; the doctrine was invented in the first place by a few dissident Franciscans because it suited their convenience to invent it; eventually, but only after much initial reluctance, it was accepted by the papacy because it suited the convenience of the popes to accept it". Garth Hallett, "drawing on a previous study of Wittgenstein's treatment of word meaning", argued that the dogma of infallibility is neither true nor false but meaningless; in practice, he claims, the dogma seems to have no practical use and to have succumbed to the sense that it is irrelevant.

Catholic priest August Bernhard Hasler (d. 3 July 1980) wrote a detailed analysis of the First Vatican Council

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This twentieth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, held three centuries after the Council of Trent, opened on 8 December 1869 and adjourned...

, presenting the passage of the infallibility definition as orchestrated. Roger O'Toole described Hasler's work as follows: "

- It weakens or demolishes the claim that Papal Infallibility was already a universally accepted truth, and that its formal definition merely made de jure what had long been acknowledged de facto.

- It emphasizes the extent of resistance to the definition, particularly in France and Germany.

- It clarifies the 'inopportunist' position as largely a polite fiction and notes how it was used by Infallibilists to trivialize the nature of the opposition to papal claims.

- It indicates the extent to which 'spontaneous popular demand' for the definition was, in fact, carefully orchestrated.

- It underlines the personal involvement of the Pope who, despite his coy disclaimers, appears as the prime mover and driving force behind the Infallibilist campaign.

- It details the lengths to which the papacy was prepared to go in wringing formal 'submissions' from the minority even after their defeat in the Council.

- It offers insight into the ideological basis of the dogma in European political conservatism, monarchism and counter-revolution.

- It establishes the doctrine as a key contributing element in the present 'crisis' of the Roman Catholic Church."

Mark E. Powell, in his examination of the topic from a Protestant point of view, writes: "August Hasler portrays Pius IX as an uneducated, abusive megalomaniac, and Vatican I as a council that was not free. Hasler, though, is engaged in heated polemic and obviously exaggerates his picture of Pius IX. Accounts like Hasler's, which paint Pius IX and Vatican I in the most negative terms, are adequately refuted by the testimony of participants at Vatican I".

Various scripture and history-based arguments

Those opposed to papal infallibility provide various arguments, such as those cited by Geisler and MacKenzie with proof texts for papal infallibility being contended against.- White and others disagree that Matthew 16:18 refers to Peter being the Rock, based on linguistic grounds, and their understanding that his authority was shared. They argue that in this passage Peter is in the second person ("you"), but that "this rock" is in the third person, referring to Christ, (the subject of Peter's truth confession in the verse 16, and the revelation referred to in v. 17), and who is uniquely and explicitly affirmed to be the foundation of the church. Certain Catholic authorities, such as John Chrysostom and St. Augustine, are cited as supporting this understanding, with Augustine stating, "On this rock, therefore, He said, which thou hast confessed. I will build my Church. For the Rock (petra) is Christ; and on this foundation was Peter himself built".

- The "keys" in the Matthean passage and its authority is understood as primarily or exclusively pertaining to the gospel.

- The prayer of Jesus to Peter, that his faith fail not, (Luke 22:32) it is not seen as promising infallibly to a papal office, which is held to be a late and novel doctrine.

- While recognizing Peter's significant role in the early church, and initial brethren-type leadership, it is contended that the Book of Acts manifests him as inferior to the apostle Paul in his level of contribution and influence, with Paul becoming the dominant focus in the Biblical records of the early church, and the writer of most of the New Testament (receiving direct revelation), and having authority to publicly reprove Peter.(Gal. 2:11-14)

- Geisler and MacKenzie also see the absence of any reference by Peter referring to himself distinctively, such as the chief of apostles, and instead only as "an apostle," or "an elder" (1Pet. 1:1; 5:1) as weighing against Peter being the supreme and infallible head of the church universal, and indicating he would not accept such titles as the Holy Father.

- The Roman Catholic claim that the Lord's commission to Peter to "feed my lambs" in John 21:15ff requires infallibility is seen to be a serious overclaim for the passage.

- The argument based on the revelatory function connected to the office of the high priest Caiaphas, (Jn. 11:49-52) which holds that this establishes a precedent for Petrine infallibility, is rejected, based (among other reasons), on the Catholic-acknowledged position that there is no new revelation after the time of the New Testament, inferred by Rev. 22:18

- Likewise, it is also held that a Jewish infallible Magisterium did not exist, though the faith yet endured, and that the Roman Catholic doctrine on infallibility is a new invention.

- The promise of papal infallibly is seen violated by certain popes who spoke heresy (as recognized by the Roman church itself) under conditions which, it is argued, fit the criteria for infallibility.

- The condemnation of Pope Honorius IPope Honorius IPope Honorius I was pope from 625 to 638.Honorius, according to the Liber Pontificalis, came from Campania and was the son of the consul Petronius. He became pope on October 27, 625, two days after the death of his predecessor, Boniface V...

by the sixth, seventh and eighth ecumenical councils for teaching a Monothelite heresy argue against the position that papal infallibility has always been a consistent teaching of the Catholic Church. The counter argument is that Honorius, as Pope Leo II stated, was anathematized, not because of heresy, but because of his negligence. - Regarding the Council of JerusalemCouncil of JerusalemThe Council of Jerusalem is a name applied by historians and theologians to an Early Christian council that was held in Jerusalem and dated to around the year 50. It is considered by Catholics and Orthodox to be a prototype and forerunner of the later Ecumenical Councils...

, Peter is not seen being looked to as the infallible head of the church, with James exercising the more decisive leadership, and providing the definitive sentence. Nor is he seen elsewhere being the final and universal arbiter about any doctrinal dispute about faith in the life of the church. - The conclusion that monarchical leadership by an infallible pope is needed and existed, is held as unwarranted on scriptural and historical grounds. Rather than appeal to an infallible head, the scriptures are seen as being the infallible authority. Rather than an infallible pope, church leadership in the New Testament is understood as being that of bishops and elders, denoting the same office. (Titus 1:5-7)

- It is further argued that the doctrine of papal infallibility lacked universal or widespread support in the bulk of church history, contrary to the claims made by Vatican 1 in first promulgating it, and that substantial opposition existed from within the Catholic Church, even at the time of its official institution, testifying to its lack of scriptural and historical warrant.

Position of Eastern Orthodoxy

The dogma of papal infallibility is rejected by Eastern Orthodoxy. Orthodox Christians hold that the Holy SpiritHoly Spirit (Christianity)

For the majority of Christians, the Holy Spirit is the third person of the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and is Almighty God...

will not allow the whole Body of Orthodox Christians to fall into error but leave open the question of how this will be ensured in any specific case. Eastern Orthodoxy considers that the first seven ecumenical council

Ecumenical council

An ecumenical council is a conference of ecclesiastical dignitaries and theological experts convened to discuss and settle matters of Church doctrine and practice....

s were infallible as accurate witnesses to the truth of the gospel, not so much on account of their institutional structure as on account of their reception by the Christian faithful.

Furthermore, Orthodox Christians do not believe that any individual bishop is infallible or that the idea of Papal Infallibility was taught during the first centuries of Christianity. Orthodox historians often point to the condemnation of Pope Honorius as a heretic by the Sixth Ecumenical council as a significant indication. However, it is debated whether Honorius' letter to Sergius met (in retrospect) the criteria set forth at Vatican I. Other Orthodox scholars argue that past Papal statements that appear to meet the conditions set forth at Vatican I for infallible status presented teachings in faith and morals are now acknowledged as problematic.

Anglican churches

The Church of EnglandChurch of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

and its sister churches in the Anglican Communion

Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is an international association of national and regional Anglican churches in full communion with the Church of England and specifically with its principal primate, the Archbishop of Canterbury...

reject papal infallibility, a rejection given expression in the Thirty-Nine Articles

Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion are the historically defining statements of doctrines of the Anglican church with respect to the controversies of the English Reformation. First established in 1563, the articles served to define the doctrine of the nascent Church of England as it related to...

of Religion (1571):

Methodism

John WesleyJohn Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

amended the Anglican Articles of Religion for use by Methodists

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

, particularly those in America

United Methodist Church

The United Methodist Church is a Methodist Christian denomination which is both mainline Protestant and evangelical. Founded in 1968 by the union of The Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren Church, the UMC traces its roots back to the revival movement of John and Charles Wesley...

. The Methodist Articles

Articles of Religion (Methodist)

The Articles of Religion are an official doctrinal statement of American Methodism. John Wesley abridged for the American Methodists the Thirty-Nine Articles of Anglicanism, removing the Calvinistic parts among others. The Articles were adopted at a conference in 1784 and are found in paragraph 103...

omit the express provisions in the Anglican articles concerning the errors of the Church of Rome and the authority of councils, but retain Article V which implicitly pertains to the Roman Catholic idea of papal authority as capable of defining articles of faith on matters not clearly derived from Scripture:

Reformed churches

PresbyterianPresbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

and Reformed churches

Reformed churches

The Reformed churches are a group of Protestant denominations characterized by Calvinist doctrines. They are descended from the Swiss Reformation inaugurated by Huldrych Zwingli but developed more coherently by Martin Bucer, Heinrich Bullinger and especially John Calvin...

reject papal infallibility. The Westminster Confession of Faith

Westminster Confession of Faith

The Westminster Confession of Faith is a Reformed confession of faith, in the Calvinist theological tradition. Although drawn up by the 1646 Westminster Assembly, largely of the Church of England, it became and remains the 'subordinate standard' of doctrine in the Church of Scotland, and has been...

which was intended in 1646 to replace the Thirty-Nine Articles

Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion are the historically defining statements of doctrines of the Anglican church with respect to the controversies of the English Reformation. First established in 1563, the articles served to define the doctrine of the nascent Church of England as it related to...

, goes so far as to label the Roman pontiff "Antichrist"; it contains the following statements:

Evangelical churches

EvangelicalEvangelicalism