Stanley Forman Reed

Encyclopedia

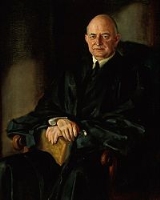

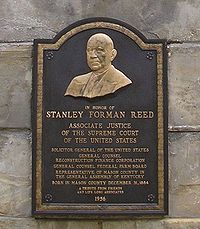

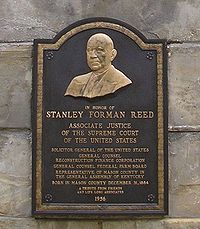

Stanley Forman Reed was a noted American

attorney who served as United States Solicitor General

from 1935 to 1938 and as an Associate Justice

of the U.S. Supreme Court

from 1938 to 1957. He was the last Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school (though Justice Robert H. Jackson

who served from 1941-1954 was the last such justice appointed to the Supreme Court).

, on the last day of 1884 to John and Frances (Forman) Reed. His father was a wealthy physician and a Protestant who adhered to no particular organized church. The Reeds and Formans traced their history to the earliest colonial period in America, and these family heritages were impressed upon young Stanley at an early age.

Reed attended Kentucky Wesleyan College

and received a B.A.

degree in 1902. He then attended Yale University

as an undergraduate, and obtained a second B.A. in 1906. He studied law at the University of Virginia

(where he was a member of St. Elmo Hall) and Columbia University

, but did not obtain a law degree. Reed married the former Winifred Elgin in May 1908. The couple had two sons, John A. and Stanley Jr., who both became attorneys. In 1909 he traveled to France

and studied at the Sorbonne

, where he obtained his auditeur bénévole.

After his studies in France, Reed returned to Kentucky. He was admitted to the bar in 1910 and established a legal practice in Maysville

. He was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly

in 1912 and served two two-year terms. After the United States entered World War I

in April 1917, Reed enlisted in the United States Army

and was commissioned a lieutenant. When the war ended in 1918, Reed returned to his private law practice and became a well-known corporate attorney. He represented the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

and the Kentucky Burley Tobacco Growers Association, among other large corporations. Stanley Reed was very active in the Sons of the American Revolution

and Sons of Colonial Wars, while his wife was a national officer in the Daughters of the American Revolution

. The Reeds settled on a farm near Maysville

, where Stanley Reed raised prize-winning Holstein

cattle in his spare time.

s. It was this reputation which brought him to the attention of federal officials.

Herbert Hoover

had been elected President of the United States

in November 1928, and took office in March 1929. But even then, the agricultural industry

in the United States was heading for a depression. Unlike his predecessor, Hoover agreed to provide some federal support for agriculture, and in June 1929 the Congress

passed the Agriculture Marketing Act

. The Act established and was administered by the Federal Farm Board

. The crash of the stock market

in late October 1929 led the Federal Farm Board's general counsel to resign. Although Reed was a Democrat

, his reputation as a corporate agricultural lawyer led President Hoover to appoint him the new general counsel of the Federal Farm Board on November 7, 1929. Reed served as general counsel until December 1932.

(RFC) resigned, and Reed was appointed the agency's new general counsel. Since 1930, Chairman of the Federal Reserve

Eugene Meyer

had pressed Hoover to take a more active approach to ameliorating the Great Depression. Hoover finally relented, and submitted legislation. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation Act was signed into law on January 22, 1932, but its operations were kept secret for five months. Hoover not only feared political attacks from Republicans

but that publicity about which corporations were receiving RFC assistance might disrupt the agency's attempts to keep companies financially viable. When Congress passed legislation in July 1932 forcing the RFC to make public which companies received loans, the resulting political embarrassment led to the resignation of the RFC's president and his successor as well as other staff turnover at the agency. Franklin D. Roosevelt

's election as President in November 1932 led to further staff changes. On December 1, 1932, the RFC's general counsel resigned, and Hoover appointed Reed to the position. Roosevelt—impressed with Reed's work and needing someone who knew the agency, its staff and its operations—kept Reed on. Reed mentored and protected the careers of a number of young lawyers at RFC, many of whom became highly influential in the Roosevelt administration: Alger Hiss

, Robert H. Jackson

, Thomas Gardiner Corcoran

, Charles Edward Wyzanski, Jr.

(later an important federal district court judge), and David Cushman Coyle.

During his tenure at the RFC, Reed influenced two major national policies. First, Reed was instrumental in setting up the Commodity Credit Corporation

. In early October 1933, President Roosevelt ordered RFC president Jesse Jones to establish a program to strengthen cotton prices. On October 16, 1933, Jones met with Reed and together they created the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6340 the next day, which legally established the CCC. The brilliance of the CCC was that the government would hold surplus cotton as security for the loan. If cotton prices rose above the value of the loan, farmers could redeem their cotton, pay off the loan and make a profit. If prices stayed low, the farmer still had enough money to live as well as plant next year. The plan worked so well that it became the basis for the New Deal

's entire agricultural program.

Second, Reed helped to successfully defend the administration's gold policy, saving the nation's monetary policy

as well. Deflation had caused the value of the United States dollar

to fall nearly 60 percent. But federal law still permitted Americans and foreign citizens to redeem paper money and coins in gold at the its pre-Depression value, causing a run on the gold reserves of the United States. Taking the United States off the gold standard

would stop the run. It would also further devalue the dollar, making American goods less expensive and more attractive to foreign buyers. In a series of moves, Roosevelt took the nation off the gold standard in March and April 1933, causing the dollar's value to sink. But additional deflation was needed. One way to do this was to raise the price of gold, but federal law required the Treasury to buy gold at its high, pre-Depression price. President Roosevelt asked the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to buy gold above the market price to further devalue the dollar. Although Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr.

believed the government lacked the authority to buy gold, Reed joined with Treasury general counsel Herman Oliphant

to provide critical legal support for the plan. The additional deflation helped stabilize the economy during a critical period where bank run

s were common.

Reed's help with Roosevelt's gold polices was not yet finished. On June 5, 1933, the Congress passed a joint resolution (48 Stat. 112) voiding clauses in all public and private contracts permitting redemption in gold. Hundreds of angry creditors sued to overturn the law. The case finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court. United States Attorney General

Homer Stille Cummings

asked Reed to join him in writing the government's brief for the Court and assisting him during oral argument. Reed's help was critical, for the high court was resolutely conservative when it came to the sanctity of contracts. On February 2, 1935, the Supreme Court made the unprecedented announcement that it was delaying its ruling by a week. The court shocked the nation again by announcing a second delay on February 9. Finally, on February 18, 1935, the Supreme Court held in Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co., 294 U.S. 240

(1935), that the government had the power to abrogate private contracts but not public ones. However, the majority said, since there had been no showing that contractors with the federal government had been harmed, no payments would be made.

" led Roosevelt to appoint him Solicitor General. J. Crawford Biggs

, the incumbent Solicitor General, was generally considered ineffective if not incompetent (he had lost 10 of the 17 cases he argued in his first five months in office). Biggs resigned on March 14, 1935. Reed was named his replacement on March 18 and confirmed by the Senate

on March 25. He was confronted by an office in chaos. Several major challenges to the National Industrial Recovery Act

—considered the cornerstone of the New Deal—were reaching the Supreme Court, and Reed was forced to drop the appeals because the Office of the Solicitor General was unprepared to argue them. Reed worked quickly to restore order, and subsequent briefs were noted for their strong legal argument and extensive research. Reed soon brought before the high court appeals of the constitutionality of the Agricultural Adjustment Act

, Securities Act of 1933

, Social Security Act, National Labor Relations Act

, Bankhead Cotton Control Act, Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

, Guffey Coal Control Act, Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 and the enabling act for the Tennessee Valley Authority

, and revived the battle over the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). The press of appeals was so great that Reed argued six major cases before the Supreme Court in two weeks. On December 10, 1935, he collapsed from exhaustion during oral argument before the Court. Reed lost a number of these cases, including Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States

, 295 U.S. 495

(1935) (invalidating the National Industrial Recovery Act) and United States v. Butler

, 297 U.S. 1

(1936) (invalidating the Agricultural Adjustment Act).

1937 proved to be a banner year for the Solicitor General. Reed argued and won such major cases as West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish

, 300 U.S. 379

(March 29, 1937; upholding minimum wage laws), National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation

, 301 U.S. 1

(April 12, 1937; upholding the National Labor Relations Act), and Steward Machine Company v. Davis

, 301 U.S. 548

(May 24, 1937; upholding the taxing power of the Social Security Act). By the end of 1937, Reed was winning most of his economic cases and had a reputation as being one of the strongest Solicitor Generals since the creation of the office in 1870.

announced he would retire from the Supreme Court on January 18. President Roosevelt nominated Reed as his replacement on January 15. Many in the nation's capital worried about the nomination fight. Associate Justice Willis Van Devanter

, one of the Court's conservative "Four Horsemen

," had retired the previous summer. Roosevelt had nominated Senator Hugo Black

as his replacement, and Black's nomination battle proved to be a long and bitter one. To the relief of many, Reed's nomination was swift and generated little debate in the Senate. He was confirmed on January 25, 1938, and seated as an Associate Justice on January 31. His successor as Solicitor General was Robert H. Jackson. As of 2010, Reed was the last person to serve as a Supreme Court Justice without possessing a law degree.

Stanley Reed spent 19 years on the Supreme Court. But Reed was not lonely on the bench: Within two years, Reed was joined on the bench by his mentor, Felix Frankfurter

, and his protégé, Robert H. Jackson. Reed and Jackson held very similar views on national security issues, and often voted together. While Reed and Frankfurter also held similar views, Frankfurter usually concurred with Reed (offering lengthy, professorial discussions of the law compared to Reed's terse opinions keeping to the facts of the case).

Reed was considered a moderate and often provided the critical fifth vote in split rulings. He authored more than 300 opinions, and Chief Justice Warren Burger said "he wrote with clarity and firmness...". Reed was an economic progressive, and generally supported racial desegregation, civil liberties, trade union

rights and economic regulation. On free speech, national security and certain social issues, however, Reed was generally a conservative. He often approved of federal (but not state or local) restrictions on civil liberties. Reed also opposed applying the Bill of Rights

to the states via the 14th Amendment

.

case. Hiss, one of Reed and Frankfurter's protégés, was accused of espionage

in August 1948. Hiss was tried in June 1949. Hiss' attorneys subpoenaed both Reed and Frankfurter. Although Reed ethically objected to having a sitting Associate Justice of the Supreme Court testify in a legal proceeding, he agreed to do so once he was subpoenaed. A number of observers strongly denounced Reed for refusing to disobey the subpoena.

, Felix Frankfurter

, William O. Douglas

and Frank Murphy

, whom Roosevelt had sent to follow Black and Reed on the court." But by 1955, Reed was dissenting much more frequently. Reed began to feel that the Court's jurisprudential center had shifted too far away from him, and that he was losing his effectiveness.

Stanley Reed retired from the Supreme Court on February 25, 1957, citing old age. He was 73 years old. Charles Evans Whittaker

was appointed his successor.

Reed led a fairly active retirement. In November 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Reed led a fairly active retirement. In November 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower

asked Reed to chair the newly-formed United States Commission on Civil Rights

. Eisenhower announced the nomination on November 7, but Reed turned down the nomination on December 3. Reed cited the impropriety of having a former Associate Justice sit on such a political body. But some media reports indicated that his appointment would have been opposed by civil rights activists, who felt Reed was not sufficiently progressive.

Reed did, however, continued to serve the federal judiciary in a number of ways. For several years, he served as a temporary judge on a number of lower federal courts, particularly in the District of Columbia. He also served in special capacities where judicial experience was needed, such as boundary disputes between states.

Increasingly frail and often ill, Stanley Reed and his wife lived at the Hilaire Nursing Home in Huntington, New York

for the last few years of their lives. Reed died there on April 2, 1980. He was survived by his wife and sons. He was interred in Maysville, Ky. He is currently the longest-lived Supreme Court Justice in American history.

An extensive collection of Reed's personal and official papers, including his Supreme Court files, is archived at the University of Kentucky

in Lexington

, where they are open for research.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

attorney who served as United States Solicitor General

United States Solicitor General

The United States Solicitor General is the person appointed to represent the federal government of the United States before the Supreme Court of the United States. The current Solicitor General, Donald B. Verrilli, Jr. was confirmed by the United States Senate on June 6, 2011 and sworn in on June...

from 1935 to 1938 and as an Associate Justice

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States are the members of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the Chief Justice of the United States...

of the U.S. Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

from 1938 to 1957. He was the last Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school (though Justice Robert H. Jackson

Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson was United States Attorney General and an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court . He was also the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials...

who served from 1941-1954 was the last such justice appointed to the Supreme Court).

Early life

Stanley Reed was born in the small town of Minerva in Mason County, KentuckyMason County, Kentucky

Mason County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2000, the population was 16,800. Its county seat is Maysville. The county is named for George Mason, a Virginia delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention, known as the "Father of the Bill of Rights"...

, on the last day of 1884 to John and Frances (Forman) Reed. His father was a wealthy physician and a Protestant who adhered to no particular organized church. The Reeds and Formans traced their history to the earliest colonial period in America, and these family heritages were impressed upon young Stanley at an early age.

Reed attended Kentucky Wesleyan College

Kentucky Wesleyan College

Kentucky Wesleyan College is a private Methodist college in Owensboro, Kentucky, a city on the Ohio River. KWC is just 40 minutes east of Evansville, Indiana, 2 hours north of Nashville, Tennessee, 2 hours west of Louisville, Kentucky, and 4 hours east of St. Louis, Missouri...

and received a B.A.

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

degree in 1902. He then attended Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

as an undergraduate, and obtained a second B.A. in 1906. He studied law at the University of Virginia

University of Virginia

The University of Virginia is a public research university located in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States, founded by Thomas Jefferson...

(where he was a member of St. Elmo Hall) and Columbia University

Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, is one of the oldest and most prestigious law schools in the United States. A member of the Ivy League, Columbia Law School is one of the professional graduate schools of Columbia University in New York City. It offers the J.D., LL.M., and J.S.D. degrees in...

, but did not obtain a law degree. Reed married the former Winifred Elgin in May 1908. The couple had two sons, John A. and Stanley Jr., who both became attorneys. In 1909 he traveled to France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and studied at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne

The Sorbonne is an edifice of the Latin Quarter, in Paris, France, which has been the historical house of the former University of Paris...

, where he obtained his auditeur bénévole.

After his studies in France, Reed returned to Kentucky. He was admitted to the bar in 1910 and established a legal practice in Maysville

Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a city in and the county seat of Mason County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 8,993 at the 2000 census, making it the fiftieth largest city in Kentucky by population. Maysville is on the Ohio River, northeast of Lexington. It is the principal city of the Maysville...

. He was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

in 1912 and served two two-year terms. After the United States entered World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

in April 1917, Reed enlisted in the United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

and was commissioned a lieutenant. When the war ended in 1918, Reed returned to his private law practice and became a well-known corporate attorney. He represented the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P...

and the Kentucky Burley Tobacco Growers Association, among other large corporations. Stanley Reed was very active in the Sons of the American Revolution

Sons of the American Revolution

The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution is a Louisville, Kentucky-based fraternal organization in the United States...

and Sons of Colonial Wars, while his wife was a national officer in the Daughters of the American Revolution

Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution is a lineage-based membership organization for women who are descended from a person involved in United States' independence....

. The Reeds settled on a farm near Maysville

Newdigate-Reed House

The Newdigate-Reed House is a two story log house built by the Newdigate family at the top of the hill near the Lexington-Maysville Turnpike. John Newdigate, a farmer, is listed as the landowner in 1854...

, where Stanley Reed raised prize-winning Holstein

Holstein (cattle)

Holstein cattle is a breed of cattle known today as the world's highest production dairy animal. Originating in Europe, Holsteins were bred in what is now the Netherlands and more specifically in the two northern provinces of North Holland and Friesland...

cattle in his spare time.

Federal Farm Bureau

Reed's work for a number of large agricultural interested in Kentucky made him a nationally known authority on the law of agricultural cooperativeCooperative

A cooperative is a business organization owned and operated by a group of individuals for their mutual benefit...

s. It was this reputation which brought him to the attention of federal officials.

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

had been elected President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

in November 1928, and took office in March 1929. But even then, the agricultural industry

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

in the United States was heading for a depression. Unlike his predecessor, Hoover agreed to provide some federal support for agriculture, and in June 1929 the Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

passed the Agriculture Marketing Act

Agriculture Marketing Act

Under the administration of Herbert Hoover, the Agriculture Marketing Act of 1929 established the Federal Farm Board with a revolving fund of half a billion dollars. The original act was sponsored by Hoover in an attempt to stop the downward spiral of crop prices by seeking to buy, sell and store...

. The Act established and was administered by the Federal Farm Board

Federal Farm Board

The Federal Farm Board was actually created in 1929, before the stock market crash on Black Tuesday, 1929, but its powers were later enlarged to meet the economic crisis farmers faced during the Great Depression. It was established by the Agricultural Marketing Act to stabilize prices and to...

. The crash of the stock market

New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange is a stock exchange located at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at 13.39 trillion as of Dec 2010...

in late October 1929 led the Federal Farm Board's general counsel to resign. Although Reed was a Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

, his reputation as a corporate agricultural lawyer led President Hoover to appoint him the new general counsel of the Federal Farm Board on November 7, 1929. Reed served as general counsel until December 1932.

Reconstruction Finance Corporation

In December 1932, the general counsel of the Reconstruction Finance CorporationReconstruction Finance Corporation

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was an independent agency of the United States government, established and chartered by the US Congress in 1932, Act of January 22, 1932, c. 8, 47 Stat. 5, during the administration of President Herbert Hoover. It was modeled after the War Finance Corporation...

(RFC) resigned, and Reed was appointed the agency's new general counsel. Since 1930, Chairman of the Federal Reserve

Chairman of the Federal Reserve

The Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is the head of the central banking system of the United States. Known colloquially as "Chairman of the Fed," or in market circles "Fed Chairman" or "Fed Chief"...

Eugene Meyer

Eugene Meyer

Eugene Isaac Meyer was an American financier, public official, publisher of the Washington Post newspaper. He served as Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1930 to 1933. He was the father of publisher Katharine Graham.-Biography:Born in Los Angeles, California, he was one of eight children of...

had pressed Hoover to take a more active approach to ameliorating the Great Depression. Hoover finally relented, and submitted legislation. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation Act was signed into law on January 22, 1932, but its operations were kept secret for five months. Hoover not only feared political attacks from Republicans

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

but that publicity about which corporations were receiving RFC assistance might disrupt the agency's attempts to keep companies financially viable. When Congress passed legislation in July 1932 forcing the RFC to make public which companies received loans, the resulting political embarrassment led to the resignation of the RFC's president and his successor as well as other staff turnover at the agency. Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

's election as President in November 1932 led to further staff changes. On December 1, 1932, the RFC's general counsel resigned, and Hoover appointed Reed to the position. Roosevelt—impressed with Reed's work and needing someone who knew the agency, its staff and its operations—kept Reed on. Reed mentored and protected the careers of a number of young lawyers at RFC, many of whom became highly influential in the Roosevelt administration: Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss was an American lawyer, government official, author, and lecturer. He was involved in the establishment of the United Nations both as a U.S. State Department and U.N. official...

, Robert H. Jackson

Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson was United States Attorney General and an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court . He was also the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials...

, Thomas Gardiner Corcoran

Thomas Gardiner Corcoran

Thomas Gardiner Corcoran was one of several Irish American advisors in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's brain trust during the New Deal, and later, a close friend and advisor to President Lyndon B. Johnson....

, Charles Edward Wyzanski, Jr.

Charles Edward Wyzanski, Jr.

Charles Edward Wyzanski, Jr. was a United States federal judge.Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Wyzanski received an A.B. from Harvard College in 1927 and an LL.B. from Harvard Law School in 1930...

(later an important federal district court judge), and David Cushman Coyle.

During his tenure at the RFC, Reed influenced two major national policies. First, Reed was instrumental in setting up the Commodity Credit Corporation

Commodity Credit Corporation

The Commodity Credit Corporation is a wholly owned government corporation created in 1933 to "stabilize, support, and protect farm income and prices"...

. In early October 1933, President Roosevelt ordered RFC president Jesse Jones to establish a program to strengthen cotton prices. On October 16, 1933, Jones met with Reed and together they created the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6340 the next day, which legally established the CCC. The brilliance of the CCC was that the government would hold surplus cotton as security for the loan. If cotton prices rose above the value of the loan, farmers could redeem their cotton, pay off the loan and make a profit. If prices stayed low, the farmer still had enough money to live as well as plant next year. The plan worked so well that it became the basis for the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

's entire agricultural program.

Second, Reed helped to successfully defend the administration's gold policy, saving the nation's monetary policy

Monetary policy

Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money, often targeting a rate of interest for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability. The official goals usually include relatively stable prices and low unemployment...

as well. Deflation had caused the value of the United States dollar

United States dollar

The United States dollar , also referred to as the American dollar, is the official currency of the United States of America. It is divided into 100 smaller units called cents or pennies....

to fall nearly 60 percent. But federal law still permitted Americans and foreign citizens to redeem paper money and coins in gold at the its pre-Depression value, causing a run on the gold reserves of the United States. Taking the United States off the gold standard

Gold standard

The gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed mass of gold. There are distinct kinds of gold standard...

would stop the run. It would also further devalue the dollar, making American goods less expensive and more attractive to foreign buyers. In a series of moves, Roosevelt took the nation off the gold standard in March and April 1933, causing the dollar's value to sink. But additional deflation was needed. One way to do this was to raise the price of gold, but federal law required the Treasury to buy gold at its high, pre-Depression price. President Roosevelt asked the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to buy gold above the market price to further devalue the dollar. Although Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr.

Henry Morgenthau, Jr.

Henry Morgenthau, Jr. was the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He played a major role in designing and financing the New Deal...

believed the government lacked the authority to buy gold, Reed joined with Treasury general counsel Herman Oliphant

Herman Oliphant

Herman Oliphant was a professor of law. He started at the University of Chicago, going to Columbia University in 1922. Shortly after arriving there, he wrote to the university's president, Nicholas Murray Butler, outlining some plans he had for reorganizing the curriculum of the law school...

to provide critical legal support for the plan. The additional deflation helped stabilize the economy during a critical period where bank run

Bank run

A bank run occurs when a large number of bank customers withdraw their deposits because they believe the bank is, or might become, insolvent...

s were common.

Reed's help with Roosevelt's gold polices was not yet finished. On June 5, 1933, the Congress passed a joint resolution (48 Stat. 112) voiding clauses in all public and private contracts permitting redemption in gold. Hundreds of angry creditors sued to overturn the law. The case finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court. United States Attorney General

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

Homer Stille Cummings

Homer Stille Cummings

Homer Stille Cummings was a U.S. political figure who was United States Attorney General from 1933 to 1939. He also was elected mayor of Stamford, Connecticut, three times before, founding the legal firm of Cummings & Lockwood in 1909...

asked Reed to join him in writing the government's brief for the Court and assisting him during oral argument. Reed's help was critical, for the high court was resolutely conservative when it came to the sanctity of contracts. On February 2, 1935, the Supreme Court made the unprecedented announcement that it was delaying its ruling by a week. The court shocked the nation again by announcing a second delay on February 9. Finally, on February 18, 1935, the Supreme Court held in Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co., 294 U.S. 240

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1935), that the government had the power to abrogate private contracts but not public ones. However, the majority said, since there had been no showing that contractors with the federal government had been harmed, no payments would be made.

Solicitor General

Reed's invaluable assistance in defending the federal government's interests in "the Gold Clause CasesGold Clause Cases

The Gold Clause Cases were a series of actions brought before the Supreme Court of the United States, in which the court narrowly upheld restrictions on the ownership of gold implemented by the administration of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in order to fight the Great Depression. The cases...

" led Roosevelt to appoint him Solicitor General. J. Crawford Biggs

James Crawford Biggs

James Crawford Biggs was born in Oxford, North Carolina, on August 29, 1872, to William and Elizabeth Arlington Biggs. Biggs was a student at the Horner Military School in Oxford from 1883-1887 before attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He graduated Summa Cum Laude from the...

, the incumbent Solicitor General, was generally considered ineffective if not incompetent (he had lost 10 of the 17 cases he argued in his first five months in office). Biggs resigned on March 14, 1935. Reed was named his replacement on March 18 and confirmed by the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

on March 25. He was confronted by an office in chaos. Several major challenges to the National Industrial Recovery Act

National Industrial Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act , officially known as the Act of June 16, 1933 The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), officially known as the Act of June 16, 1933 The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), officially known as the Act of June 16, 1933 (Ch. 90, 48 Stat. 195, formerly...

—considered the cornerstone of the New Deal—were reaching the Supreme Court, and Reed was forced to drop the appeals because the Office of the Solicitor General was unprepared to argue them. Reed worked quickly to restore order, and subsequent briefs were noted for their strong legal argument and extensive research. Reed soon brought before the high court appeals of the constitutionality of the Agricultural Adjustment Act

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was a United States federal law of the New Deal era which restricted agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies not to plant part of their land and to kill off excess livestock...

, Securities Act of 1933

Securities Act of 1933

Congress enacted the Securities Act of 1933 , in the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929 and during the ensuing Great Depression...

, Social Security Act, National Labor Relations Act

National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act or Wagner Act , is a 1935 United States federal law that limits the means with which employers may react to workers in the private sector who create labor unions , engage in collective bargaining, and take part in strikes and other forms of concerted activity in...

, Bankhead Cotton Control Act, Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 , , also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act, was a law that was passed by the United States Congress to facilitate regulation of electric utilities, by either limiting their operations to a single state, and thus subjecting them to effective state...

, Guffey Coal Control Act, Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 and the enabling act for the Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority is a federally owned corporation in the United States created by congressional charter in May 1933 to provide navigation, flood control, electricity generation, fertilizer manufacturing, and economic development in the Tennessee Valley, a region particularly affected...

, and revived the battle over the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). The press of appeals was so great that Reed argued six major cases before the Supreme Court in two weeks. On December 10, 1935, he collapsed from exhaustion during oral argument before the Court. Reed lost a number of these cases, including Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States

Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States

A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 , was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that invalidated regulations of the poultry industry according to the nondelegation doctrine and as an invalid use of Congress's power under the commerce clause...

, 295 U.S. 495

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1935) (invalidating the National Industrial Recovery Act) and United States v. Butler

United States v. Butler

United States v. Butler, , was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the processing taxes instituted under the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act were unconstitutional...

, 297 U.S. 1

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1936) (invalidating the Agricultural Adjustment Act).

1937 proved to be a banner year for the Solicitor General. Reed argued and won such major cases as West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, , was a decision by the United States Supreme Court upholding the constitutionality of minimum wage legislation enacted by the State of Washington, overturning an earlier decision in Adkins v. Children's Hospital,...

, 300 U.S. 379

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(March 29, 1937; upholding minimum wage laws), National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation

National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation

National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, 301 U.S. 1 , was a United States Supreme Court case that declared that the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 was constitutional...

, 301 U.S. 1

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(April 12, 1937; upholding the National Labor Relations Act), and Steward Machine Company v. Davis

Steward Machine Company v. Davis

Steward Machine Company v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548 , was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the unemployment compensation provisions of the Social Security Act of 1935. The Act established a national taxing structure designed to induce states to adopt laws for funding and...

, 301 U.S. 548

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(May 24, 1937; upholding the taxing power of the Social Security Act). By the end of 1937, Reed was winning most of his economic cases and had a reputation as being one of the strongest Solicitor Generals since the creation of the office in 1870.

The Supreme Court

On January 5, 1938, 75-year-old Associate Justice George SutherlandGeorge Sutherland

Alexander George Sutherland was an English-born U.S. jurist and political figure. One of four appointments to the Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding, he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S...

announced he would retire from the Supreme Court on January 18. President Roosevelt nominated Reed as his replacement on January 15. Many in the nation's capital worried about the nomination fight. Associate Justice Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, January 3, 1911 to June 2, 1937.- Early life and career :...

, one of the Court's conservative "Four Horsemen

Four Horsemen (Supreme Court)

The "Four Horsemen" was the nickname given by the press to four conservative members of the United States Supreme Court during the 1932–1937 terms, who opposed the New Deal agenda of President Franklin Roosevelt. They were Justices Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland,...

," had retired the previous summer. Roosevelt had nominated Senator Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

as his replacement, and Black's nomination battle proved to be a long and bitter one. To the relief of many, Reed's nomination was swift and generated little debate in the Senate. He was confirmed on January 25, 1938, and seated as an Associate Justice on January 31. His successor as Solicitor General was Robert H. Jackson. As of 2010, Reed was the last person to serve as a Supreme Court Justice without possessing a law degree.

Stanley Reed spent 19 years on the Supreme Court. But Reed was not lonely on the bench: Within two years, Reed was joined on the bench by his mentor, Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

, and his protégé, Robert H. Jackson. Reed and Jackson held very similar views on national security issues, and often voted together. While Reed and Frankfurter also held similar views, Frankfurter usually concurred with Reed (offering lengthy, professorial discussions of the law compared to Reed's terse opinions keeping to the facts of the case).

Reed was considered a moderate and often provided the critical fifth vote in split rulings. He authored more than 300 opinions, and Chief Justice Warren Burger said "he wrote with clarity and firmness...". Reed was an economic progressive, and generally supported racial desegregation, civil liberties, trade union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

rights and economic regulation. On free speech, national security and certain social issues, however, Reed was generally a conservative. He often approved of federal (but not state or local) restrictions on civil liberties. Reed also opposed applying the Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

to the states via the 14th Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

.

Important opinions

Among Reed's more notable decisions are:- United States v. Rock Royal, 307 U.S. 533Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1939) - This was one of the first cases in which Reed wrote the majority opinion. The case was especially important to Reed because of his prior career as an attorney for agricultural cooperatives (Rock Royal was a milk producers co-op). Reed stuck closely to the facts in the case, quoting at length from the statute, regulations and agency order. - Gorin v. United StatesGorin v. United StatesGorin v. United States and Salich v. United States was a supreme court case decided in 1941 in the United States. It involved the Espionage Act and it's use against Mihail Gorin, an intelligence agent from the Soviet Union, and Hafis Salich, a Navy employee who sold to Gorin information on Japanese...

, (1941) - Upheld several aspects of the Espionage Act of 1917Espionage Act of 1917The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law passed on June 15, 1917, shortly after the U.S. entry into World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code but is now found under Title 18, Crime... - Smith v. AllwrightSmith v. AllwrightSmith v. Allwright , 321 U.S. 649 , was a very important decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Democratic Party's use of all-white primaries in Texas, and other states where the party used the...

, 321 U.S. 649Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1944) - In 1935, a unanimous Supreme Court in Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U.S. 45Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

, had held that political parties in Texas did not violate the constitutional rights of African AmericanAfrican AmericanAfrican Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

citizens by denying them the right to vote in a primary electionPrimary electionA primary election is an election in which party members or voters select candidates for a subsequent election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election....

. But in Smith v. Allwright, the issue came before the Court again. This time, the plaintiff alleged that the state, not the political party, had denied black citizens the right to vote. In an 8-to-1 decision authored by Reed, the Supreme Court overruled Grovey as wrongly decided. In ringing terms, Reed dismissed the state action question and declared that "the Court throughout its history has freely exercised its power to reexamine the basis of its constitutional decisions." The lone dissenter was Justice Roberts, who had written the majority opinion nine years earlier in Grovey. - Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U.S. 373Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1946) - In a 7-to-1 ruling, Reed applied the undue burden standardUndue burden standardThe undue burden standard is a constitutional test fashioned by the Supreme Court of the United States. The test, first developed in the late 19th century, is widely used in American constitutional law....

to a Virginia law which required separate but equalSeparate but equalSeparate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group's public facilities was to...

racial segregationRacial segregationRacial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

in public transportation. Reed found that the law created an undue burden because uniformity of law was essential in certain interstate activities, such as transportation. - Adamson v. CaliforniaAdamson v. CaliforniaAdamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the incorporation of the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights. Its decision is part of a long line of cases that eventually led to the Selective Incorporation Doctrine.-Background:In Adamson v...

, 332 U.S. 46Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1947) - Adamson was charged with murder but chose not to testify because he knew the prosecutor would ask him about his prior criminal record. Adamson argued that because the prosecutor had drawn attention to his refusal to testify, and thus Adamson's freedom against self-incrimination had been violated. Reed wrote that the rights guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment did not extend the protections of the Fifth Amendment to state courts. Reed felt that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend to apply the Bill of Rights to states without limitation. - Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of EducationMcCollum v. Board of EducationMcCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 , was a landmark 1948 United States Supreme Court case related to the power of a state to use its tax-supported public school system in aid of religious instruction...

, 333 U.S. 203Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1948) - Reed said he was proudest of his dissent in Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education. The ruling was the first to declare that a state had violated the Establishment ClauseEstablishment Clause of the First AmendmentThe Establishment Clause is the first of several pronouncements in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, stating, Together with the Free Exercise Clause The Establishment Clause is the first of several pronouncements in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution,...

. Reed disliked the phrase "wall of separation between church and state," and his dissent contains his famous dictum about the phrase: "A rule of law should not be drawn from a figure of speech." - Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1946) - Reed authored this majority opinion for a court which confronted the issue of whether judges could censor newspapers for impugning the reputation of the courts. The Miami Herald newspaper had published two editorials and a cartoon criticizing a Florida court's actions in a pending trial. The judge cited the publisher and editors for contemptContempt of courtContempt of court is a court order which, in the context of a court trial or hearing, declares a person or organization to have disobeyed or been disrespectful of the court's authority...

, claiming that the published material maligned the integrity of the court and thereby interfered with the fair administration of justice. Hewing closely to the facts in the case, Reed used the clear and present dangerClear and present dangerClear and present danger was a term used by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in the unanimous opinion for the case Schenck v. United States, concerning the ability of the government to regulate speech against the draft during World War I:...

test to come down firmly on the side of freedom of expression. - Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1954) - Brown v. Board of Education was recognized as a critical case even before it reached the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren, realizing how controversial the case would be for the public, very much wanted to avoid any dissents in the case. But Reed was the lone hold-out. Other members of the Supreme Court worried about Reed's commitment to civil rights, as he was a member of the (then) all-white Burning Tree ClubBurning Tree ClubBurning Tree Club is a private, all-male golf club in Bethesda, Maryland. Membership in the club is extremely exclusive. The course at Burning Tree has been played by numerous presidents, foreign dignitaries, high-ranking executive officials, members of Congress, and military leaders...

in Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, and his Kentucky home had an all-white restrictive covenantRestrictive covenantA restrictive covenant is a type of real covenant, a legal obligation imposed in a deed by the seller upon the buyer of real estate to do or not to do something. Such restrictions frequently "run with the land" and are enforceable on subsequent buyers of the property...

(a covenant which had led Reed to recuse himself from a civil rights case in 1948). Yet, Reed had written the majority decision in Smith v. AllwrightSmith v. AllwrightSmith v. Allwright , 321 U.S. 649 , was a very important decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Democratic Party's use of all-white primaries in Texas, and other states where the party used the...

and joined the majority in Sweatt v. PainterSweatt v. PainterSweatt v. Painter, , was a U.S. Supreme Court case that successfully proved lack of equality, in favor of a black applicant, the "separate but equal" doctrine of racial segregation established by the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson. The case was also influential in the landmark case of Brown v...

, 339 U.S. 629Case citationCase citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1950), which barred separate but equal racial segregation in law schools. Reed originally planned to write a dissent in Brown, but joined the majority before a decision was issued. Many observers, including Chief Justice Warren, believed Reed's decision to join the Brown decision helped win public acceptance for the decision.

Hiss case

Reed's fame and notoriety did not stem solely from his judicial rulings, however. In 1949, Reed was caught up in the Alger HissAlger Hiss

Alger Hiss was an American lawyer, government official, author, and lecturer. He was involved in the establishment of the United Nations both as a U.S. State Department and U.N. official...

case. Hiss, one of Reed and Frankfurter's protégés, was accused of espionage

Espionage

Espionage or spying involves an individual obtaining information that is considered secret or confidential without the permission of the holder of the information. Espionage is inherently clandestine, lest the legitimate holder of the information change plans or take other countermeasures once it...

in August 1948. Hiss was tried in June 1949. Hiss' attorneys subpoenaed both Reed and Frankfurter. Although Reed ethically objected to having a sitting Associate Justice of the Supreme Court testify in a legal proceeding, he agreed to do so once he was subpoenaed. A number of observers strongly denounced Reed for refusing to disobey the subpoena.

Dissents and retirement

By the mid-1950s, Justice Reed was dissenting more and more frequently from court rulings. His first full dissent had come in 1939, nearly a year after his tenure on the court began. Initially, his dissents "were only when, with Hughes, Brandeis, Stone or Roberts—like himself, lawyers of deep experience—he could not go along with what he considered the judge-made amendments of the Constitution implicit in the opinions of Hugo BlackHugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

, Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

, William O. Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

and Frank Murphy

Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy was a politician and jurist from Michigan. He served as First Assistant U.S. District Attorney, Eastern Michigan District , Recorder's Court Judge, Detroit . Mayor of Detroit , the last Governor-General of the Philippines , U.S...

, whom Roosevelt had sent to follow Black and Reed on the court." But by 1955, Reed was dissenting much more frequently. Reed began to feel that the Court's jurisprudential center had shifted too far away from him, and that he was losing his effectiveness.

Stanley Reed retired from the Supreme Court on February 25, 1957, citing old age. He was 73 years old. Charles Evans Whittaker

Charles Evans Whittaker

Charles Evans Whittaker was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1957 to 1962.-Early years:...

was appointed his successor.

Retirement and death

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

asked Reed to chair the newly-formed United States Commission on Civil Rights

United States Commission on Civil Rights

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is historically a bipartisan, independent commission of the U.S. federal government charged with the responsibility for investigating, reporting on, and making recommendations concerning civil rights issues that face the nation.-Commissioners:The Commission is...

. Eisenhower announced the nomination on November 7, but Reed turned down the nomination on December 3. Reed cited the impropriety of having a former Associate Justice sit on such a political body. But some media reports indicated that his appointment would have been opposed by civil rights activists, who felt Reed was not sufficiently progressive.

Reed did, however, continued to serve the federal judiciary in a number of ways. For several years, he served as a temporary judge on a number of lower federal courts, particularly in the District of Columbia. He also served in special capacities where judicial experience was needed, such as boundary disputes between states.

Increasingly frail and often ill, Stanley Reed and his wife lived at the Hilaire Nursing Home in Huntington, New York

Huntington, New York

The Town of Huntington is one of ten towns in Suffolk County, New York, USA. Founded in 1653, it is located on the north shore of Long Island in northwestern Suffolk County, with Long Island Sound to its north and Nassau County adjacent to the west. Huntington is part of the New York metropolitan...

for the last few years of their lives. Reed died there on April 2, 1980. He was survived by his wife and sons. He was interred in Maysville, Ky. He is currently the longest-lived Supreme Court Justice in American history.

An extensive collection of Reed's personal and official papers, including his Supreme Court files, is archived at the University of Kentucky

University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky, also known as UK, is a public co-educational university and is one of the state's two land-grant universities, located in Lexington, Kentucky...

in Lexington

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

, where they are open for research.

Quotations

- "The United States is a constitutional democracy. Its organic law grants to all citizens a right to participate in the choice of elected officials without restriction by any state because of race." - Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944)

- "There is a recognized abstract principle, however, that may be taken as a postulate for testing whether particular state legislation in the absence of action by Congress is beyond state power. This is that the state legislation is invalid if it unduly burdens that commerce in matters where uniformity is necessary—necessary in the constitutional sense of useful in accomplishing a permitted purpose." - Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946)

- "Freedom of discussion should be given the widest possible range compatible with the essential requirement of the fair and orderly administration of justice. ... That a judge might be influenced by a desire to placate the accusing newspaper to retain public esteem and secure reelection at the cost of unfair rulings against an accused is too remote a possibility to be considered a clear and present dangerClear and present dangerClear and present danger was a term used by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in the unanimous opinion for the case Schenck v. United States, concerning the ability of the government to regulate speech against the draft during World War I:...

to justice." - Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331 (1946) - "A rule of law should not be drawn from a figure of speech." - Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948) (commenting on the phrase "wall of separation between church and state")

- "Philosophers and poets, thinkers of high and low degree from every age and race have sought to expound the meaning of virtue, but each teaches his own conception of the moral excellence that satisfies standards of good conduct. Are the tests of the Puritan or the Cavalier to be applied, those of the city or the farm, the Christian or non-Christian, the old or the young? Does the Bill of Rights permit Illinois to forbid any reflection on the virtue of racial or religious classes which a jury or a judge may think exposes them to derision or obloquy, words themselves of quite uncertain meaning as used in the statute? I think not." - Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 (1952)

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Stone Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Vinson Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University PressOxford University PressOxford University Press is the largest university press in the world. It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the Vice-Chancellor known as the Delegates of the Press. They are headed by the Secretary to the Delegates, who serves as...

, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3. - Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789-1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical SocietySupreme Court Historical SocietyThe Supreme Court Historical Society is a private, non-profit organization dedicated to preserving and communicating the history of the U.S. Supreme Court.-History:...

), (Congressional QuarterlyCongressional QuarterlyCongressional Quarterly, Inc., or CQ, is a privately owned publishing company that produces a number of publications reporting primarily on the United States Congress...

Books, 2001) ISBN 1568021267; ISBN 9781568021263. - Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) ISBN 0791013774, ISBN 978-0791013779.

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0871875543.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing 1994). 590 pp. ISBN 0815311761; ISBN 978-0815311768.

External links

- Stanley F. Reed Oral History Project, Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral HistoryLouie B. Nunn Center for Oral HistoryThe Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky actively collects oral history interviews concentrating on 20th and 21st century Kentucky history, and maintains a collection of over 8,000 interviews made up of over 100 projects. The Center's emphasis has been on political,...

, University of Kentucky Libraries - Stanley F. Reed papers. Manuscript Collection, Special Collections, William T. Young Library, University of Kentucky.