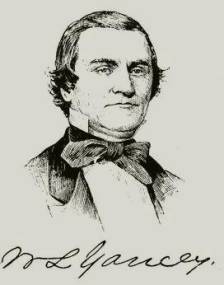

William Lowndes Yancey

Encyclopedia

William Lowndes Yancey was a journalist, politician, orator, diplomat and an American leader of the Southern secession

movement. A member of the group known as the Fire-Eaters

, Yancey was one of the most effective agitators for secession and rhetorical defenders of slavery

. An early critic of John C. Calhoun

and nullification

, by the late 1830s Yancey began to identify with Calhoun and the struggle against the forces of the anti-slavery movement. In 1849 Yancey was a firm supporter of Calhoun's "Southern Address" and an adamant opponent of the Compromise of 1850

.

Throughout the 1850s, Yancey, sometimes referred to as the "Orator of Secession", demonstrated the ability to hold large audiences under his spell for hours at a time. At the 1860 Democratic National Convention

, Yancey, a leading opponent of Stephen A. Douglas

and the concept of popular sovereignty

, was instrumental in splitting the party into Northern and Southern factions.

During the Civil War

, Yancey was appointed by Confederate President Jefferson Davis

to head a diplomatic delegation to Europe in the attempt to secure formal recognition of Southern independence. In these efforts, Yancey was unsuccessful and frustrated. Upon his return to America in 1862, Yancey was elected to the Confederate States Senate where he was a frequent critic of the Davis Administration. Suffering from ill health for much of his life, Yancey died during the war

at the age of 48.

in Warren County

, Georgia

. On December 8, 1808, she married Benjamin Cudworth Yancey, a lawyer in South Carolina

who had served on the USS Constellation

during the Quasi-War with France. Yancey was born at "the Aviary"; three years later, on October 26, 1817, his father died of yellow fever

.

Yancey’s widowed mother married the Reverend Nathan Sydney Smith Beman

on April 23, 1821. Beman had temporarily relocated to South Carolina

to operate Mt. Zion Academy, where William was a student. In the spring of 1823, the entire family moved when Reverend Beman took a position at the First Presbyterian Church in Troy

, New York

. Beman worked with Reverend Charles G. Finney

in the New School movement and in the 1830s became involved with abolitionism

through contacts with Theodore Dwight Ward and Lyman Beecher

.

Beman’s marriage was marred by domestic unrest and spousal abuse that led to serious considerations of divorce and finally a permanent separation in 1835. This atmosphere affected the children and caused William to reject many of his step-father’s teachings. Yancey’s biographer, historian Eric H. Walther, speculates the character of Yancey’s later career was a result of low self-esteem and a search for public adulation and approval that went back to his childhood experiences with Reverend Beman.

In the fall of 1830, Yancey was enrolled at Williams College

in northwestern Massachusetts

. The 16-year old Yancey was admitted as a sophomore based on the required entrance examinations. At Williams, he participated in the debating society and for a short time was the editor of a student newspaper. In the autumn of 1832, Yancey took his first steps as a politician by working on the campaign for Whig Ebenezer Emmons

. Overall, Yancey had a successful stay at Williams academically that was marred only by frequent disciplinary problems. Despite being selected as the Senior Orator by his class, Yancey left the school in the spring of 1833, six weeks before graduation.

, South Carolina

. He originally lived on his uncle’s plantation, where he served as a bookkeeper. The uncle, Robert Cunningham, was a strong unionist, as were most of Yancey’s family, including his birth father. On July 4, 1834, at a Fourth of July celebration, Yancey made a stirring nationalistic address in which he openly attacked the radicals of the state who were still talking secession from the repercussions of the Nullification Crisis

:

As a result of Yancey’s political activities, he was appointed editor of the Greenville (South Carolina) Mountaineer in November 1834. As editor, he attacked both nullification and the chief architect of nullification, John C. Calhoun

As a result of Yancey’s political activities, he was appointed editor of the Greenville (South Carolina) Mountaineer in November 1834. As editor, he attacked both nullification and the chief architect of nullification, John C. Calhoun

. Yancey compared Calhoun to Aaron Burr

and referred to them as "two fallen arch angels — who have made efforts to tear down the battlements and safeguards of our country, that they might rule, the Demons of the Storm."

Yancey resigned from the newspaper on May 14, 1835. On August 13, married Sarah Caroline Earl. As his dowry, Yancey received 35 slaves and a quick entry into the planter class. In the winter of 1836–1837, Yancey removed to her plantation in Alabama

, near Cahaba

(Dallas County

). It was an inopportune time to relocate. As a result of the Panic of 1837

, Yancey's financial position was seriously damaged by cotton prices that fell from fifteen cents a pound in 1835 to as low as five cents a pound in 1837.

In early 1838, Yancey took over the Cahaba Southern Democrat, and his first editorial was a strong defense of slavery. From his current economic perspective, Yancey began to identify the anti-slavery movement negatively with issues such as the establishment of a national bank, internal improvements

, and expanding federal power. As the former nationalist moved to a states’ rights position, Yancey also changed his attitude toward Calhoun — applauding Calhoun’s role in the Gag rule

Debates. Yancey also began to attack Henry Clay

for his support of the American Colonization Society

, which Yancey equated with attacks on Southern slavery.

Yancey, like most members of the planter class, was a strong believer in a personal code of honor. In September 1838, Yancey returned for a brief return visit to Greenville. A political slur by Yancey in a private conversation was overheard by a teenage relative of the aggrieved party. Yancey was confronted by another relative (and his wife’s uncle), Dr. Robinson Earle. Conversation turned to violence, and the always-armed Yancey ended up killing the doctor in a street brawl. Yancey was tried and sentenced to a year in jail for manslaughter. An unrepentant Yancey was pardoned after only a few months, but while incarcerated Yancey wrote for his newspaper, "Reared with the spirit of a man in my bosom — and taught to preserve inviolate my honor — my character, and my person, I have acted as such a spirit dictated."

Yancey returned to his paper in March 1839, but sold it a couple of months later when he moved to Wetumpka

in Coosa County, Alabama. While his intent was to resume his life as a planter, Yancey suffered a huge financial reversal when his slaves were poisoned as a result of a feud between Yancey’s overseer and a neighboring overseer. Two slaves were killed, and most of the others were incapacitated for months. Unable to afford replacements and burdened with other debts from his newspaper, Yancey was forced to sell most of the slaves as they recovered. Yancey did open in Wetumpka the Argus and Commercial Advertiser.

Yancey was increasingly interested in politics as his personal politics moved towards the most radical wing of the Southern Democratic Party. Influenced most by Dixon Hall Lewis

Yancey was increasingly interested in politics as his personal politics moved towards the most radical wing of the Southern Democratic Party. Influenced most by Dixon Hall Lewis

, Yancey fell into a social and political circle that included political leaders of the state such as Thomas Mays, J. L. M. Curry, John A. Campbell, and John Gill Shorter. In April 1840, Yancey started a weekly campaign newsletter that supported Democrat

Van Buren

over Whig

Harrison

in the presidential election while emphasizing that slavery should now be the most important political and economic concern of the South. While still not a secessionist, Yancey was also no longer an unconditional unionist.

He was elected in 1841 to the Alabama House of Representatives

, in which he served for one year. In March 1842, Yancey sold his newspaper because of increasing debt (throughout his career as an editor he faced the problem of many fellow editors — obtaining and collecting on subscriptions), and he opened a law practice instead. In 1843, he ran for the Alabama Senate

and was elected by a vote of 1,115 to 1,025. His special concern in this election was the effort being made by Whigs

to determine apportionment in the state legislature based on the "federal ratio" of each slave counting as three-fifths of a person. Currently only whites

were counted and the change would benefit the Whigs who generally were the largest slaveholders. This division between large slaveholders and yeomen Alabamans would continue through the Alabama secession convention in 1861.

In 1844, Yancey was elected to the United States House of Representatives

to fill a vacancy (winning with a 2,197 to 2,137 vote) and re-elected in 1845 (receiving over 4,000 votes as the Whigs did not even field a candidate). In Congress, his political ability and unusual oratorical gifts at once gained recognition. Yancey delivered his first speech on January 6, 1845, when he was selected by the Democrats to respond to a speech by Thomas Clingman, a Whig from North Carolina

, who had opposed Texas annexation. Clingman was offended by the tone of Yancey’s speech and afterwards Yancey refused to clarify that he had not intended to impugn Clingman’s honor. Clingman challenged Yancey to a duel, and he accepted. The exchange of pistol fire occurred in nearby Beltsville, Maryland

; neither combatant was injured.

In Congress, Yancey was an effective spokesman in opposing internal improvements and tariff

s and supporting states’ rights and the start of the Mexican-American War. More and more, he subscribed to conspiracy theories regarding Northern intentions while helping to provide ammunition for those Northerners who were starting to believe in a slaveholders’ conspiracy. In 1846, however, he resigned his seat, partly for financial reasons, and partly because of his disgust with the Northern Democrats, whom he accused of sacrificing their principles for economic interests.

Within a few months of his resignation, Yancey moved to Montgomery

Within a few months of his resignation, Yancey moved to Montgomery

, where he purchased a 20 acres (80,937.2 m²) dairy farm while establishing a law partnership with John A. Elmore. No longer a planter, Yancey still remained a slaveholder

, owning 11 slaves in 1850, 14 by 1852, and 24 between 1858 and 1860. While he had suggested with his resignation that his active role in politics might be over, "perhaps forever", Yancey found this to be impossible.

Yancey recognized the significance of the Wilmot Proviso

to the South and in 1847, as the first talk of slaveholder Zachary Taylor

as a presidential candidate surfaced, Yancey saw him as a possibility for bringing together a Southern political movement that would cross party lines. Yancey made it clear that his support for Taylor was conditional upon Taylor denouncing the Wilmot Proviso. However, Taylor announced that he would seek the Whig nomination, and in December 1847 Lewis Cass

of Michigan

, the leading Democratic candidate, endorsed the policy of Popular sovereignty

.

With no available candidate sufficiently opposed to the Proviso, in 1848 Yancey secured the adoption by the state Democratic convention of the "Alabama Platform," which was endorsed by the legislatures of Alabama

and Georgia

and by Democratic state conventions in Florida

and Virginia

. The platform declared:

1. The Federal government could not restrict slavery in the territories.

2. Territories could not prohibit slavery until the point where they were meeting in convention to draft a state constitution in order to petition Congress for statehood.

3. Alabama delegates to the Democratic convention were to oppose any candidate supporting either the Proviso or Popular Sovereignty (which allowed territories to exclude slavery at any point)

4. The federal government must specifically overrule Mexican anti-slavery laws in the Mexican Cession

and actively protect slavery.

When the national convention was held in Baltimore, Cass was nominated on the fourth ballot. Yancey’s proposal that the convention adopt the main points of the Alabama Platform was rejected by a 216–36 vote. Yancey and one other Alabama delegate left the convention in protest, and Yancey’s efforts to stir up a third party movement in the state failed.

The opening salvo in a new level of sectional conflict occurred on December 13, 1848, when Whig John G. Palfrey

of Massachusetts

introduced a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. Throughout 1849 in the South "the rhetoric of resistance to the North escalated and spread". Calhoun

delivered his famous "Southern Address", but only 48 out of 121 Congressmen signed off on it. Yancey persuaded a June 1849 state Democratic Party meeting to endorse Calhoun’s address and was instrumental in calling for the Nashville Convention

scheduled for June 1850.

Yancey was opposed to both the Compromise of 1850

and the disappointing results of the Nashville Convention. The latter, rather than making a strong stand for secession as Yancey had hoped, simply advocated extending the Missouri Compromise Line to the Pacific Coast. Yancey helped create Southern Rights Associations (a concept that originated in South Carolina) in Alabama to pursue a secessionist agenda. A convention held in February 1851 of these Alabama associations produced Yancey’s radical "Address to the People of Alabama". The address began:

The address hit all of the main points that would ultimately resurface in the secession during the winter of 1860–1861, especially the treatment of Southerners:

Despite the efforts of Yancey, the popularity of the Compromise of 1850, the failure of the Nashville Convention, and the acceptance of the more moderate Georgia Platform

by much of the South, led to unionist victories in Alabama and most of the South. Yancey’s third party support for George Troup

of Georgia on a Southern rights platform drew only 2,000 votes.

." Historian Emory Thomas notes that Yancey, along with Edmund Ruffin

and Robert Barnwell Rhett, "remained in the secessionist forefront longest and loudest." Thomas characterized the whole fire-eater cause as reactionary in purpose (the preservation of the South as it then existed), but revolutionary in means (the rejection of the existing political order).

When the conflicts in Kansas Territory

known as Bleeding Kansas

erupted in 1855–1856, Yancey spoke publicly in support of Jefferson Buford’s efforts to raise 300 men to go to Kansas and fight for Southern interests. In 1856, Yancey was head of the platform committee for the state Democratic and Anti–Know Nothing

Convention, and he succeeded in having the convention readopt the Alabama Platform. In June 1856, he participated in a rally condemning Charles Sumner

while praising his assailant Preston Brooks

, who nearly bludgeoned Sumner to death in the United States Senate Chamber. In June 1857, Yancey spoke at a rally opposing Robert J. Walker

's actions as territorial governor of Kansas, and in January 1858, he participated in a rally supporting William Walker, the famous Nicaragua

filibuster

, calling the "Central American enterprise as the cause of the South."

Throughout the mid-1850s, he also lectured on behalf of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union, an organization that eventually purchased and restored Mount Vernon from John A. Washington in 1858. Yancey helped to raise $75,000 for this project.

Editor and fellow fire-eater James DeBow

was a leader in establishing the Southern Commercial Conventions in the 1850s. At the 1857 meeting in Knoxville, DeBow had called for a reopening of the international slave trade. At the May 1858 convention in Montgomery, responding to a speech by Virginian Roger A. Pryor opposing the slave trade, Yancey, in an address that spanned several days, made the following points:

Yancey supported a plan originated by Edmund Ruffin

Yancey supported a plan originated by Edmund Ruffin

for the creation of a League of United Southerners as an alternative to the national political parties. In a June 16, 1858 letter to his friend James S. Slaughter that was publicly circulated (Horace Greeley

referred to it as "The Scarlet Letter"), Yancey wrote:

Yancey was ill for much of the remainder of 1858 and early 1859. For the 1859 Southern Commercial Convention in Vicksburg, which passed the resolution to repeal all state and federal regulations banning the slave trade, Yancey could only contribute editorials, although by July 1859 he was able to speak publicly in Columbia, South Carolina, in favor of repealing the restrictions. When the Alabama Democratic Party organized in the winter of 1859-1860 for the upcoming national convention, they chose Yancey to lead them on the basis of the Alabama Platform. Both Stephen A. Douglas

and popular sovereignty were the immediate targets, but by then Yancey also recognized that secession would be necessary if a "Black Republican" were to gain the White House.

Failing to nominate a candidate, the convention adjourned and reconvened in Baltimore on June 18, 1860. In a last gasp effort to obtain party unity, Douglas supporter George N. Sanders made an unauthorized offer to Yancey to run as vice-president. Yancey turned this down, and the entire Yancey delegation from Alabama was refused credentials in favor of a pro–Douglas slate headed by John Forsyth. With the South Carolina delegation also being denied credentials, the Louisiana, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee delegations left the convention. The Southern representatives reconvened in Baltimore on June 23 and adopted the Yancey platform from the Charleston convention and nominated John C. Breckinridge for president. In a speech before the convention, Yancey characterized the Douglas supporters as "ostrich like — their head was in the sand of squatter sovereignty, and they did not know their great, ugly, ragged abolition body was exposed". Yancey, who had already made thirty public addresses in 1860, delivered twenty more during the campaign. If he had not been before, he was certainly now a national figure — a figure making it clear that secession would follow anything other than a Breckinridge election.

Yancey’s speaking tour in favor of Breckinridge was not confined to the South. In Wilmington, Delaware, Yancey stated, "We stand upon the dark platform of southern slavery, and all we ask is to be allowed to keep it to ourselves. Let us do that, and we will not let the negro [sic] insult you by coming here and marrying your daughters."

On October 10, 1860, at Cooper Institute Hall in New York Yancey advised Northerners interested in preserving the Union to "Enlarge your jails and penitentiaries, re-enforce and strengthen your police force, and keep the irrepressible conflict fellows from stealing our negroes…" Yancey cited southern fears that with abolitionists in power, "Emissaries will percolate between master [and] slave as water between the crevices of rocks underground. They will be found everywhere, with strychnine to put in our wells." He further warned the crowd that Republican agitation would make Southern whites "the enemies of that race until we drench our fields with the blood of the unfortunate people."

At Faneuil Hall

in Boston, Yancey defended the practices of slavery:

From Boston, Yancey’s tour included stops in Albany, Syracuse, Florence (Kentucky), Louisville, Nashville, and New Orleans, finally returning to Montgomery on November 5. When news of Lincoln’s election reached the city, Yancey rhetorically asked a public assemblage protesting the results, "Shall we remain [in the Union] and all be slaves? Shall we wait to bear our share of the common dishonor? God forbid!"

On February 24, 1860, the Alabama legislature passed a joint resolution requiring the governor to call for the election of delegates to a state convention if a Republican was elected president. After first waiting for the official electoral votes to be counted, Governor Andrew Moore called for the election of delegates to take place on December 24 with the convention to meet on January 7, 1861. When the convention convened, Yancey was the guiding spirit. The delegates were split between those insisting on immediate secession versus those who would secede only in cooperation with other Southern states. A frustrated Yancey lashed out at those cooperationists:

On February 24, 1860, the Alabama legislature passed a joint resolution requiring the governor to call for the election of delegates to a state convention if a Republican was elected president. After first waiting for the official electoral votes to be counted, Governor Andrew Moore called for the election of delegates to take place on December 24 with the convention to meet on January 7, 1861. When the convention convened, Yancey was the guiding spirit. The delegates were split between those insisting on immediate secession versus those who would secede only in cooperation with other Southern states. A frustrated Yancey lashed out at those cooperationists:

Eventually, the ordinance of secession was passed over cooperationists objections by a vote of 61–39.

When the newly-established Confederate States of America met later that month in Montgomery to establish their formal union, Yancey was not a delegate, but he delivered the address of welcome to Jefferson Davis

, selected as provisional President, on his arrival at Montgomery

. While many of the fire-eaters were opposed to the selection of a relative moderate like Davis, Yancey accepted him as a good choice. In his speech, Yancey indicated that in the selection of Davis, "The man and the hour have met. We now hope that prosperity, honor, and victory await his administration." Many historians agree with Emory Thomas who wrote, "When Yancey and Davis met in Montgomery the helm of the revolution changed hands. Yancey and the radicals had stirred the waters; Davis and the moderates would sail the ship."

and Pierre Adolphe Rost

were also part of the mission. Confederate Secretary of State Toombs’ official instructions to Yancey were to convince Europe of the righteousness and legality of southern secession, the viability of the militarily strong Confederacy, the value of cotton and virtually duty free trade, and the South’s willingness to observe all treaty agreements in effect between Britain and the United States except for the portion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty

requiring aid in combating the African slave trade. Above all, Yancey was to strive for diplomatic recognition.

While the choice of a firebrand like Yancey for a diplomatic post has been second questioned, Yancey was as effective in dealing with British diplomats and industrialists as could have been expected. Arriving in Britain just a few days ahead of the news about the attack on Fort Sumter, Yancey and his delegation met informally with British foreign secretary Lord John Russell

on May 3 and May 9. Yancey emphasized the points from his instructions and denied, upon being questioned by Russell, that there was any intent to reopen the slave trade. Russell was non-committal, and on May 12, Queen Victoria announced British neutrality combined with recognition that a state of belligerency existed. While Yancey was generally optimistic about the ultimate success of his mission, his observations in conversations and in the British papers forced him to conclude that the slavery issue was the primary obstacle to formal diplomatic recognition.

After news arrived concerning the Confederate victory at Bull Run

After news arrived concerning the Confederate victory at Bull Run

, Yancey attempted to arrange another meeting with Russell, but he was forced to present his arguments in writing. In an August 24 response directed to the representatives "of the so-styled Confederate States of America", Russell merely reiterated the previous determination to remain neutral. Critics maintain that the Yancey mission failed to adequately exploit openings presented by Union Secretary of State William Seward’s

antagonist attitude towards Great Britain or to address British concerns concerning the effect of the war on Great Britain. In late August, with little else to do, Yancey submitted his resignation but, due to the events of the Trent Affair

, Yancey did not leave until his replacements, James M. Mason

and John Slidell

(selected by President Davis in July before he was aware of Yancey’s intent), arrived in January 1862. Yancey did make one further attempt to meet with Russell in the wake of the Trent affair, but Russell replied to the delegation that "we must decline to enter into any official communication with them."

While still in England, Yancey was elected to the Confederate Senate. His return home, because of the Union blockade, found him landing at the Sabine Pass

near the Texas and Louisiana border. On his way to Richmond, he stopped in New Orleans where he made a public speech lamenting the fact that Europe looked down on the Confederacy over the issue of slavery, stating, "We cannot look for any sympathy or help from abroad. We must rely on ourselves alone."

From March 28, 1862 until May 1, 1863, Yancey served in three sessions of the Confederate Congress. While there, he reluctantly supported the Confederate Conscription Act of April 16, 1862, but was instrumental in allowing many state exemptions to the draft as well as the unpopular exemption for one overseer for every twenty slaves, an exemption that applied to about 30,000 men. He unsuccessfully argued against the excessive use of secret, unrecorded sessions of Congress and generally pursued a states’ rights position in regard to the exercise of national war powers in general and impressment of supplies and slaves by the federal Confederate government in particular. On military matters, Yancey wanted details provided to Congress on reports of execution without trials of Confederate soldiers by General Braxton Bragg

, questioned the reasons Virginia had twenty nine brigadier generals while Alabama only had four, authored a resolution condemning drunkenness within the army, and joined in demands that Davis account for complaints on the military administration of the Trans-Mississippi District.

Yancey gradually ran afoul of President Davis on matters of policy, although he was not one of Davis’s most extreme critics. Their differences accelerated in a series of letters exchanged after May 1863, and no final resolution was reached. In Congress, Yancey and Benjamin Hill

of Georgia, who had previously clashed in 1856, had their differences over a bill intended to create the Confederate Supreme Court erupt into physical violence. Hill hit Yancey in the head with a glass inkstand on the floor of the Senate, but in the ensuing investigation it was Yancey, not Hill, who was censured.

Yancey returned to Alabama in May 1863, before Congress had adjourned. By the end of June, Yancey was extremely ill, but he still continued his correspondence with President Davis and others. Finally on July 27, 1863, two weeks before his forty ninth birthday, Yancey died of kidney disease. Yancey’s funeral on July 29, 1863, brought the city of Montgomery to a standstill, and he was buried at Oakwood cemetery on Goat Hill near the original Confederate Capitol.

in Montgomery, Alabama, was designated a National Historic Landmark

of the United States in 1973. Due to unauthorized interior renovations, it was later de-designated, but it remains listed on the National Register of Historic Places

.

Secession in the United States

Secession in the United States can refer to secession of a state from the United States, secession of part of a state from that state to form a new state, or secession of an area from a city or county....

movement. A member of the group known as the Fire-Eaters

Fire-Eaters

In United States history, the term Fire-Eaters refers to a group of extremist pro-slavery politicians from the South who urged the separation of southern states into a new nation, which became known as the Confederate States of America.-Impact:...

, Yancey was one of the most effective agitators for secession and rhetorical defenders of slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. An early critic of John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

and nullification

Nullification Crisis

The Nullification Crisis was a sectional crisis during the presidency of Andrew Jackson created by South Carolina's 1832 Ordinance of Nullification. This ordinance declared by the power of the State that the federal Tariff of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and therefore null and void within...

, by the late 1830s Yancey began to identify with Calhoun and the struggle against the forces of the anti-slavery movement. In 1849 Yancey was a firm supporter of Calhoun's "Southern Address" and an adamant opponent of the Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

.

Throughout the 1850s, Yancey, sometimes referred to as the "Orator of Secession", demonstrated the ability to hold large audiences under his spell for hours at a time. At the 1860 Democratic National Convention

1860 Democratic National Convention

The 1860 Democratic National Convention was one of the crucial events in the lead-up to the American Civil War. Following a fragmented official Democratic National Convention that was adjourned in deadlock, two more presidential nominating conventions took place: a resumed official convention,...

, Yancey, a leading opponent of Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician from the western state of Illinois, and was the Northern Democratic Party nominee for President in 1860. He lost to the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom he had defeated two years earlier in a Senate contest following a famed...

and the concept of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty or the sovereignty of the people is the political principle that the legitimacy of the state is created and sustained by the will or consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. It is closely associated with Republicanism and the social contract...

, was instrumental in splitting the party into Northern and Southern factions.

During the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Yancey was appointed by Confederate President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis , also known as Jeff Davis, was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President for its entire history. He was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane Davis...

to head a diplomatic delegation to Europe in the attempt to secure formal recognition of Southern independence. In these efforts, Yancey was unsuccessful and frustrated. Upon his return to America in 1862, Yancey was elected to the Confederate States Senate where he was a frequent critic of the Davis Administration. Suffering from ill health for much of his life, Yancey died during the war

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

at the age of 48.

Youth

Yancey’s mother, Caroline Bird, lived on the family home (nicknamed "the Aviary") located near the falls of the Ogeechee RiverOgeechee River

Ogeechee River is a river in the U.S. state of Georgia. It heads at the confluence of its North and South Forks, about south-southwest of Crawfordville and flowing generally southeast to Ossabaw Sound about south of Savannah. Its largest tributary is the Canoochee River...

in Warren County

Warren County, Georgia

Warren County is a county located in the U.S. state of Georgia. It was created on December 19, 1793. As of 2000, the population was 6,336. The 2007 Census Estimate shows a population of 5,908...

, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

. On December 8, 1808, she married Benjamin Cudworth Yancey, a lawyer in South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

who had served on the USS Constellation

USS Constellation (1797)

USS Constellation was a 38-gun frigate, one of the six original frigates authorized for construction by the Naval Act of 1794. She was distinguished as the first U.S. Navy vessel to put to sea and the first U.S. Navy vessel to engage and defeat an enemy vessel...

during the Quasi-War with France. Yancey was born at "the Aviary"; three years later, on October 26, 1817, his father died of yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

.

Yancey’s widowed mother married the Reverend Nathan Sydney Smith Beman

Nathan S.S. Beman

Nathan Sidney Smith Beman was the fourth president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He was born in what is now New Lebanon, New York on November 26, 1785. He graduated from Middlebury College in 1807. He then studied theology and preached in Portland, Maine and Mount Zion, Georgia...

on April 23, 1821. Beman had temporarily relocated to South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

to operate Mt. Zion Academy, where William was a student. In the spring of 1823, the entire family moved when Reverend Beman took a position at the First Presbyterian Church in Troy

Troy, New York

Troy is a city in the US State of New York and the seat of Rensselaer County. Troy is located on the western edge of Rensselaer County and on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. Troy has close ties to the nearby cities of Albany and Schenectady, forming a region popularly called the Capital...

, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

. Beman worked with Reverend Charles G. Finney

Charles Grandison Finney

Charles Grandison Finney was a leader in the Second Great Awakening. He has been called The Father of Modern Revivalism. Finney was best known as an innovative revivalist, an opponent of Old School Presbyterian theology, an advocate of Christian perfectionism, a pioneer in social reforms in favor...

in the New School movement and in the 1830s became involved with abolitionism

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

through contacts with Theodore Dwight Ward and Lyman Beecher

Lyman Beecher

Lyman Beecher was a Presbyterian minister, American Temperance Society co-founder and leader, and the father of 13 children, many of whom were noted leaders, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Beecher, Edward Beecher, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher, and Thomas...

.

Beman’s marriage was marred by domestic unrest and spousal abuse that led to serious considerations of divorce and finally a permanent separation in 1835. This atmosphere affected the children and caused William to reject many of his step-father’s teachings. Yancey’s biographer, historian Eric H. Walther, speculates the character of Yancey’s later career was a result of low self-esteem and a search for public adulation and approval that went back to his childhood experiences with Reverend Beman.

In the fall of 1830, Yancey was enrolled at Williams College

Williams College

Williams College is a private liberal arts college located in Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. It was established in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim Williams. Originally a men's college, Williams became co-educational in 1970. Fraternities were also phased out during this...

in northwestern Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

. The 16-year old Yancey was admitted as a sophomore based on the required entrance examinations. At Williams, he participated in the debating society and for a short time was the editor of a student newspaper. In the autumn of 1832, Yancey took his first steps as a politician by working on the campaign for Whig Ebenezer Emmons

Ebenezer Emmons

Ebenezer Emmons , was a pioneering American geologist.Emmons was born at Middlefield, Massachusetts, on May 16, 1799, son of Ebenezer and Mary Emmons....

. Overall, Yancey had a successful stay at Williams academically that was marred only by frequent disciplinary problems. Despite being selected as the Senior Orator by his class, Yancey left the school in the spring of 1833, six weeks before graduation.

Early career

Yancey returned to the South, relocating to GreenvilleGreenville, South Carolina

-Law and government:The city of Greenville adopted the Council-Manager form of municipal government in 1976.-History:The area was part of the Cherokee Nation's protected grounds after the Treaty of 1763, which ended the French and Indian War. No White man was allowed to enter, though some families...

, South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

. He originally lived on his uncle’s plantation, where he served as a bookkeeper. The uncle, Robert Cunningham, was a strong unionist, as were most of Yancey’s family, including his birth father. On July 4, 1834, at a Fourth of July celebration, Yancey made a stirring nationalistic address in which he openly attacked the radicals of the state who were still talking secession from the repercussions of the Nullification Crisis

Nullification Crisis

The Nullification Crisis was a sectional crisis during the presidency of Andrew Jackson created by South Carolina's 1832 Ordinance of Nullification. This ordinance declared by the power of the State that the federal Tariff of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and therefore null and void within...

:

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

. Yancey compared Calhoun to Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr, Jr. was an important political figure in the early history of the United States of America. After serving as a Continental Army officer in the Revolutionary War, Burr became a successful lawyer and politician...

and referred to them as "two fallen arch angels — who have made efforts to tear down the battlements and safeguards of our country, that they might rule, the Demons of the Storm."

Yancey resigned from the newspaper on May 14, 1835. On August 13, married Sarah Caroline Earl. As his dowry, Yancey received 35 slaves and a quick entry into the planter class. In the winter of 1836–1837, Yancey removed to her plantation in Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, near Cahaba

Cahaba, Alabama

Cahaba, also spelled Cahawba, was the first permanent state capital of Alabama from 1820 to 1825. It is now a ghost town and state historic site. The site is located in Dallas County, southwest of Selma.-Capital:...

(Dallas County

Dallas County, Alabama

Dallas County is a county of the U.S. state of Alabama. Its name is in honor of United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas. The county seat is Selma.- History :...

). It was an inopportune time to relocate. As a result of the Panic of 1837

Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis or market correction in the United States built on a speculative fever. The end of the Second Bank of the United States had produced a period of runaway inflation, but on May 10, 1837 in New York City, every bank began to accept payment only in specie ,...

, Yancey's financial position was seriously damaged by cotton prices that fell from fifteen cents a pound in 1835 to as low as five cents a pound in 1837.

In early 1838, Yancey took over the Cahaba Southern Democrat, and his first editorial was a strong defense of slavery. From his current economic perspective, Yancey began to identify the anti-slavery movement negatively with issues such as the establishment of a national bank, internal improvements

Internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canals, harbors and navigation improvements...

, and expanding federal power. As the former nationalist moved to a states’ rights position, Yancey also changed his attitude toward Calhoun — applauding Calhoun’s role in the Gag rule

Gag rule

A gag rule is a rule that limits or forbids the raising, consideration or discussion of a particular topic by members of a legislative or decision-making body.-Origin and pros and cons:...

Debates. Yancey also began to attack Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

for his support of the American Colonization Society

American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society , founded in 1816, was the primary vehicle to support the "return" of free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa. It helped to found the colony of Liberia in 1821–22 as a place for freedmen...

, which Yancey equated with attacks on Southern slavery.

Yancey, like most members of the planter class, was a strong believer in a personal code of honor. In September 1838, Yancey returned for a brief return visit to Greenville. A political slur by Yancey in a private conversation was overheard by a teenage relative of the aggrieved party. Yancey was confronted by another relative (and his wife’s uncle), Dr. Robinson Earle. Conversation turned to violence, and the always-armed Yancey ended up killing the doctor in a street brawl. Yancey was tried and sentenced to a year in jail for manslaughter. An unrepentant Yancey was pardoned after only a few months, but while incarcerated Yancey wrote for his newspaper, "Reared with the spirit of a man in my bosom — and taught to preserve inviolate my honor — my character, and my person, I have acted as such a spirit dictated."

Yancey returned to his paper in March 1839, but sold it a couple of months later when he moved to Wetumpka

Wetumpka, Alabama

Wetumpka is a city in Elmore County, Alabama, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 5,726.The city is the county seat of Elmore County, one of the fastest growing counties in the state....

in Coosa County, Alabama. While his intent was to resume his life as a planter, Yancey suffered a huge financial reversal when his slaves were poisoned as a result of a feud between Yancey’s overseer and a neighboring overseer. Two slaves were killed, and most of the others were incapacitated for months. Unable to afford replacements and burdened with other debts from his newspaper, Yancey was forced to sell most of the slaves as they recovered. Yancey did open in Wetumpka the Argus and Commercial Advertiser.

Public office

Dixon Hall Lewis

Dixon Hall Lewis was an American politician who served as a Representative and a Senator from Alabama.-Biography:...

, Yancey fell into a social and political circle that included political leaders of the state such as Thomas Mays, J. L. M. Curry, John A. Campbell, and John Gill Shorter. In April 1840, Yancey started a weekly campaign newsletter that supported Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

Van Buren

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States . Before his presidency, he was the eighth Vice President and the tenth Secretary of State, under Andrew Jackson ....

over Whig

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

Harrison

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States , an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. He was 68 years, 23 days old when elected, the oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the...

in the presidential election while emphasizing that slavery should now be the most important political and economic concern of the South. While still not a secessionist, Yancey was also no longer an unconditional unionist.

He was elected in 1841 to the Alabama House of Representatives

Alabama House of Representatives

The Alabama House of Representatives is the lower house of the Alabama Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Alabama. The House is composed of 105 members representing an equal amount of districts, with each constituency containing at least 42,380 citizens. There are no term...

, in which he served for one year. In March 1842, Yancey sold his newspaper because of increasing debt (throughout his career as an editor he faced the problem of many fellow editors — obtaining and collecting on subscriptions), and he opened a law practice instead. In 1843, he ran for the Alabama Senate

Alabama Senate

The Alabama State Senate is the upper house of the Alabama Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Alabama. The body is composed of 35 members representing an equal amount of districts across the state, with each district containing at least 127,140 citizens...

and was elected by a vote of 1,115 to 1,025. His special concern in this election was the effort being made by Whigs

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

to determine apportionment in the state legislature based on the "federal ratio" of each slave counting as three-fifths of a person. Currently only whites

White people

White people is a term which usually refers to human beings characterized, at least in part, by the light pigmentation of their skin...

were counted and the change would benefit the Whigs who generally were the largest slaveholders. This division between large slaveholders and yeomen Alabamans would continue through the Alabama secession convention in 1861.

In 1844, Yancey was elected to the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

to fill a vacancy (winning with a 2,197 to 2,137 vote) and re-elected in 1845 (receiving over 4,000 votes as the Whigs did not even field a candidate). In Congress, his political ability and unusual oratorical gifts at once gained recognition. Yancey delivered his first speech on January 6, 1845, when he was selected by the Democrats to respond to a speech by Thomas Clingman, a Whig from North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, who had opposed Texas annexation. Clingman was offended by the tone of Yancey’s speech and afterwards Yancey refused to clarify that he had not intended to impugn Clingman’s honor. Clingman challenged Yancey to a duel, and he accepted. The exchange of pistol fire occurred in nearby Beltsville, Maryland

Beltsville, Maryland

Beltsville is a census-designated place in northern Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. The population was 15,691 at the 2000 census. Beltsville includes the unincorporated community of Vansville.-Geography:...

; neither combatant was injured.

In Congress, Yancey was an effective spokesman in opposing internal improvements and tariff

Tariff

A tariff may be either tax on imports or exports , or a list or schedule of prices for such things as rail service, bus routes, and electrical usage ....

s and supporting states’ rights and the start of the Mexican-American War. More and more, he subscribed to conspiracy theories regarding Northern intentions while helping to provide ammunition for those Northerners who were starting to believe in a slaveholders’ conspiracy. In 1846, however, he resigned his seat, partly for financial reasons, and partly because of his disgust with the Northern Democrats, whom he accused of sacrificing their principles for economic interests.

Alabama Platform and Address to the People of Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital of the U.S. state of Alabama, and is the county seat of Montgomery County. It is located on the Alabama River southeast of the center of the state, in the Gulf Coastal Plain. As of the 2010 census, Montgomery had a population of 205,764 making it the second-largest city...

, where he purchased a 20 acres (80,937.2 m²) dairy farm while establishing a law partnership with John A. Elmore. No longer a planter, Yancey still remained a slaveholder

Slaver

Slaver has several meanings:*One who deals in slaves - see slave trade*A slave ship*Saliva, i.e. either the result or act of drooling as opposed to normal salivation....

, owning 11 slaves in 1850, 14 by 1852, and 24 between 1858 and 1860. While he had suggested with his resignation that his active role in politics might be over, "perhaps forever", Yancey found this to be impossible.

Yancey recognized the significance of the Wilmot Proviso

Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso, one of the major events leading to the Civil War, would have banned slavery in any territory to be acquired from Mexico in the Mexican War or in the future, including the area later known as the Mexican Cession, but which some proponents construed to also include the disputed...

to the South and in 1847, as the first talk of slaveholder Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

as a presidential candidate surfaced, Yancey saw him as a possibility for bringing together a Southern political movement that would cross party lines. Yancey made it clear that his support for Taylor was conditional upon Taylor denouncing the Wilmot Proviso. However, Taylor announced that he would seek the Whig nomination, and in December 1847 Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass was an American military officer and politician. During his long political career, Cass served as a governor of the Michigan Territory, an American ambassador, a U.S. Senator representing Michigan, and co-founder as well as first Masonic Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Michigan...

of Michigan

Michigan

Michigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

, the leading Democratic candidate, endorsed the policy of Popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty or the sovereignty of the people is the political principle that the legitimacy of the state is created and sustained by the will or consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. It is closely associated with Republicanism and the social contract...

.

With no available candidate sufficiently opposed to the Proviso, in 1848 Yancey secured the adoption by the state Democratic convention of the "Alabama Platform," which was endorsed by the legislatures of Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

and Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

and by Democratic state conventions in Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

and Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

. The platform declared:

1. The Federal government could not restrict slavery in the territories.

2. Territories could not prohibit slavery until the point where they were meeting in convention to draft a state constitution in order to petition Congress for statehood.

3. Alabama delegates to the Democratic convention were to oppose any candidate supporting either the Proviso or Popular Sovereignty (which allowed territories to exclude slavery at any point)

4. The federal government must specifically overrule Mexican anti-slavery laws in the Mexican Cession

Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession of 1848 is a historical name in the United States for the region of the present day southwestern United States that Mexico ceded to the U.S...

and actively protect slavery.

When the national convention was held in Baltimore, Cass was nominated on the fourth ballot. Yancey’s proposal that the convention adopt the main points of the Alabama Platform was rejected by a 216–36 vote. Yancey and one other Alabama delegate left the convention in protest, and Yancey’s efforts to stir up a third party movement in the state failed.

The opening salvo in a new level of sectional conflict occurred on December 13, 1848, when Whig John G. Palfrey

John G. Palfrey

John Gorham Palfrey was an American clergyman and historian who served as a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts. A Unitarian minister, he played a leading role in the early history of Harvard Divinity School, and he later became involved in politics as a State Representative and U.S...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

introduced a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. Throughout 1849 in the South "the rhetoric of resistance to the North escalated and spread". Calhoun

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

delivered his famous "Southern Address", but only 48 out of 121 Congressmen signed off on it. Yancey persuaded a June 1849 state Democratic Party meeting to endorse Calhoun’s address and was instrumental in calling for the Nashville Convention

Nashville Convention

The Nashville Convention was a political meeting held in Nashville, Tennessee, on June 3 – 11, 1850. Delegates from nine slave holding states met to consider a possible course of action if the United States Congress decided to ban slavery in the new territories being added to the country as a...

scheduled for June 1850.

Yancey was opposed to both the Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

and the disappointing results of the Nashville Convention. The latter, rather than making a strong stand for secession as Yancey had hoped, simply advocated extending the Missouri Compromise Line to the Pacific Coast. Yancey helped create Southern Rights Associations (a concept that originated in South Carolina) in Alabama to pursue a secessionist agenda. A convention held in February 1851 of these Alabama associations produced Yancey’s radical "Address to the People of Alabama". The address began:

The address hit all of the main points that would ultimately resurface in the secession during the winter of 1860–1861, especially the treatment of Southerners:

Despite the efforts of Yancey, the popularity of the Compromise of 1850, the failure of the Nashville Convention, and the acceptance of the more moderate Georgia Platform

Georgia Platform

The Georgia Platform was a statement executed by a Georgia Convention in response to the Compromise of 1850. Supported by Unionists, the document affirmed the acceptance of the Compromise as a final resolution of the sectional slavery issues while declaring that no further assaults on Southern...

by much of the South, led to unionist victories in Alabama and most of the South. Yancey’s third party support for George Troup

George Troup

George Michael Troup was an American politician from the U.S. state of Georgia. He served in the Georgia General Assembly, U.S. House of Representatives, and Senate before becoming the 32nd Governor of Georgia for two terms and then returning to the Senate...

of Georgia on a Southern rights platform drew only 2,000 votes.

Road to secession

Yancey continued to support the most radical Southern positions and is generally included as one of a group of southerners referred to as "fire-eatersFire-Eaters

In United States history, the term Fire-Eaters refers to a group of extremist pro-slavery politicians from the South who urged the separation of southern states into a new nation, which became known as the Confederate States of America.-Impact:...

." Historian Emory Thomas notes that Yancey, along with Edmund Ruffin

Edmund Ruffin

Edmund Ruffin was a farmer and slaveholder, a Confederate soldier, and an 1850s political activist. He advocated states' rights, secession, and slavery and was described by opponents as one of the Fire-Eaters. He was an ardent supporter of the Confederacy and a longstanding enemy of the North...

and Robert Barnwell Rhett, "remained in the secessionist forefront longest and loudest." Thomas characterized the whole fire-eater cause as reactionary in purpose (the preservation of the South as it then existed), but revolutionary in means (the rejection of the existing political order).

When the conflicts in Kansas Territory

Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Kansas....

known as Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas or the Border War, was a series of violent events, involving anti-slavery Free-Staters and pro-slavery "Border Ruffian" elements, that took place in the Kansas Territory and the western frontier towns of the U.S. state of Missouri roughly between 1854 and 1858...

erupted in 1855–1856, Yancey spoke publicly in support of Jefferson Buford’s efforts to raise 300 men to go to Kansas and fight for Southern interests. In 1856, Yancey was head of the platform committee for the state Democratic and Anti–Know Nothing

Know Nothing

The Know Nothing was a movement by the nativist American political faction of the 1840s and 1850s. It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by German and Irish Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to Anglo-Saxon Protestant values and controlled by...

Convention, and he succeeded in having the convention readopt the Alabama Platform. In June 1856, he participated in a rally condemning Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner was an American politician and senator from Massachusetts. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction,...

while praising his assailant Preston Brooks

Preston Brooks

Preston Smith Brooks was a Democratic Congressman from South Carolina. Brooks is primarily remembered for his severe beating of Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the United States Senate with a gutta-percha cane, delivered in response to an anti-slavery speech in which Sumner compared Brooks'...

, who nearly bludgeoned Sumner to death in the United States Senate Chamber. In June 1857, Yancey spoke at a rally opposing Robert J. Walker

Robert J. Walker

Robert John Walker was an American economist and statesman.- Early life and education :Born in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, the son of a judge. He lived in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania from 1806 to 1814, where his father was presiding judge of the judicial district. Walker was educated at the...

's actions as territorial governor of Kansas, and in January 1858, he participated in a rally supporting William Walker, the famous Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Nicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

filibuster

Filibuster (military)

A filibuster, or freebooter, is someone who engages in an unauthorized military expedition into a foreign country to foment or support a revolution...

, calling the "Central American enterprise as the cause of the South."

Throughout the mid-1850s, he also lectured on behalf of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union, an organization that eventually purchased and restored Mount Vernon from John A. Washington in 1858. Yancey helped to raise $75,000 for this project.

Editor and fellow fire-eater James DeBow

James Dunwoody Brownson DeBow

James Dunwoody Brownson DeBow was an American publisher and statistician, best known for his influential magazine DeBow's Review, who also served as head of the U.S...

was a leader in establishing the Southern Commercial Conventions in the 1850s. At the 1857 meeting in Knoxville, DeBow had called for a reopening of the international slave trade. At the May 1858 convention in Montgomery, responding to a speech by Virginian Roger A. Pryor opposing the slave trade, Yancey, in an address that spanned several days, made the following points:

Edmund Ruffin

Edmund Ruffin was a farmer and slaveholder, a Confederate soldier, and an 1850s political activist. He advocated states' rights, secession, and slavery and was described by opponents as one of the Fire-Eaters. He was an ardent supporter of the Confederacy and a longstanding enemy of the North...

for the creation of a League of United Southerners as an alternative to the national political parties. In a June 16, 1858 letter to his friend James S. Slaughter that was publicly circulated (Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley was an American newspaper editor, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, a politician, and an outspoken opponent of slavery...

referred to it as "The Scarlet Letter"), Yancey wrote:

Yancey was ill for much of the remainder of 1858 and early 1859. For the 1859 Southern Commercial Convention in Vicksburg, which passed the resolution to repeal all state and federal regulations banning the slave trade, Yancey could only contribute editorials, although by July 1859 he was able to speak publicly in Columbia, South Carolina, in favor of repealing the restrictions. When the Alabama Democratic Party organized in the winter of 1859-1860 for the upcoming national convention, they chose Yancey to lead them on the basis of the Alabama Platform. Both Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician from the western state of Illinois, and was the Northern Democratic Party nominee for President in 1860. He lost to the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom he had defeated two years earlier in a Senate contest following a famed...

and popular sovereignty were the immediate targets, but by then Yancey also recognized that secession would be necessary if a "Black Republican" were to gain the White House.

Spreading the pro-slavery message

After twelve years' absence from the national conventions of the Democratic Party, Yancey attended the Charleston convention in April 1860. The Douglas faction refused to accept a platform, modeled after Yancey’s Alabama Platform of 1848, committed to protecting slavery in the territories. When the platform committee presented such a proposal to the convention, it was voted down on the floor by a 165–138 vote. Yancey and the Alabama delegation left the hall and were followed by the delegates of Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, Florida, Texas, and two of the three delegates from Delaware. On the next day, the Georgia delegation and a majority of the Arkansas delegation withdrew. As Eric Walther states, "Through his years of preparation and despite some brief wavering, William L. Yancey had finally destroyed the Democratic Party."Failing to nominate a candidate, the convention adjourned and reconvened in Baltimore on June 18, 1860. In a last gasp effort to obtain party unity, Douglas supporter George N. Sanders made an unauthorized offer to Yancey to run as vice-president. Yancey turned this down, and the entire Yancey delegation from Alabama was refused credentials in favor of a pro–Douglas slate headed by John Forsyth. With the South Carolina delegation also being denied credentials, the Louisiana, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee delegations left the convention. The Southern representatives reconvened in Baltimore on June 23 and adopted the Yancey platform from the Charleston convention and nominated John C. Breckinridge for president. In a speech before the convention, Yancey characterized the Douglas supporters as "ostrich like — their head was in the sand of squatter sovereignty, and they did not know their great, ugly, ragged abolition body was exposed". Yancey, who had already made thirty public addresses in 1860, delivered twenty more during the campaign. If he had not been before, he was certainly now a national figure — a figure making it clear that secession would follow anything other than a Breckinridge election.

Yancey’s speaking tour in favor of Breckinridge was not confined to the South. In Wilmington, Delaware, Yancey stated, "We stand upon the dark platform of southern slavery, and all we ask is to be allowed to keep it to ourselves. Let us do that, and we will not let the negro [sic] insult you by coming here and marrying your daughters."

On October 10, 1860, at Cooper Institute Hall in New York Yancey advised Northerners interested in preserving the Union to "Enlarge your jails and penitentiaries, re-enforce and strengthen your police force, and keep the irrepressible conflict fellows from stealing our negroes…" Yancey cited southern fears that with abolitionists in power, "Emissaries will percolate between master [and] slave as water between the crevices of rocks underground. They will be found everywhere, with strychnine to put in our wells." He further warned the crowd that Republican agitation would make Southern whites "the enemies of that race until we drench our fields with the blood of the unfortunate people."

At Faneuil Hall

Faneuil Hall

Faneuil Hall , located near the waterfront and today's Government Center, in Boston, Massachusetts, has been a marketplace and a meeting hall since 1742. It was the site of several speeches by Samuel Adams, James Otis, and others encouraging independence from Great Britain, and is now part of...

in Boston, Yancey defended the practices of slavery:

From Boston, Yancey’s tour included stops in Albany, Syracuse, Florence (Kentucky), Louisville, Nashville, and New Orleans, finally returning to Montgomery on November 5. When news of Lincoln’s election reached the city, Yancey rhetorically asked a public assemblage protesting the results, "Shall we remain [in the Union] and all be slaves? Shall we wait to bear our share of the common dishonor? God forbid!"

Secession

Eventually, the ordinance of secession was passed over cooperationists objections by a vote of 61–39.

When the newly-established Confederate States of America met later that month in Montgomery to establish their formal union, Yancey was not a delegate, but he delivered the address of welcome to Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis , also known as Jeff Davis, was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President for its entire history. He was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane Davis...

, selected as provisional President, on his arrival at Montgomery

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital of the U.S. state of Alabama, and is the county seat of Montgomery County. It is located on the Alabama River southeast of the center of the state, in the Gulf Coastal Plain. As of the 2010 census, Montgomery had a population of 205,764 making it the second-largest city...

. While many of the fire-eaters were opposed to the selection of a relative moderate like Davis, Yancey accepted him as a good choice. In his speech, Yancey indicated that in the selection of Davis, "The man and the hour have met. We now hope that prosperity, honor, and victory await his administration." Many historians agree with Emory Thomas who wrote, "When Yancey and Davis met in Montgomery the helm of the revolution changed hands. Yancey and the radicals had stirred the waters; Davis and the moderates would sail the ship."

Southern nation at war

Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Yancey met on February 18, 1861, as Davis was starting to put together the executive branch of the government. Yancey turned down a cabinet position, but indicated he would be interested in a diplomatic post. On March 16, Yancey was formally appointed as the head of a diplomatic mission to England and France. Ambrose Dudley MannAmbrose Dudley Mann

Ambrose Dudley Mann was the first United States Assistant Secretary of State and a commissioner for the Confederate States....

and Pierre Adolphe Rost

Pierre Adolphe Rost

Pierre Adolphe Rost was a Louisiana politician, diplomat, lawyer, judge, and plantation owner.- Early Life and Emigration to the United States :...

were also part of the mission. Confederate Secretary of State Toombs’ official instructions to Yancey were to convince Europe of the righteousness and legality of southern secession, the viability of the militarily strong Confederacy, the value of cotton and virtually duty free trade, and the South’s willingness to observe all treaty agreements in effect between Britain and the United States except for the portion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty

Webster-Ashburton Treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty resolving several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies...

requiring aid in combating the African slave trade. Above all, Yancey was to strive for diplomatic recognition.

While the choice of a firebrand like Yancey for a diplomatic post has been second questioned, Yancey was as effective in dealing with British diplomats and industrialists as could have been expected. Arriving in Britain just a few days ahead of the news about the attack on Fort Sumter, Yancey and his delegation met informally with British foreign secretary Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, KG, GCMG, PC , known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was an English Whig and Liberal politician who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century....

on May 3 and May 9. Yancey emphasized the points from his instructions and denied, upon being questioned by Russell, that there was any intent to reopen the slave trade. Russell was non-committal, and on May 12, Queen Victoria announced British neutrality combined with recognition that a state of belligerency existed. While Yancey was generally optimistic about the ultimate success of his mission, his observations in conversations and in the British papers forced him to conclude that the slavery issue was the primary obstacle to formal diplomatic recognition.

First Battle of Bull Run