Philippe Pétain

Encyclopedia

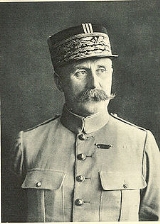

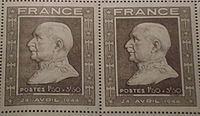

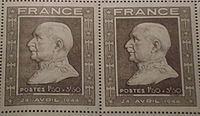

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain (petɛ̃; 24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain (Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France

, and was later Chief of State

of Vichy France

(Chef de l'État Français), from 1940 to 1944. Pétain, who was 84 years old in 1940, ranks as France's oldest head of state.

Because of his outstanding military leadership in World War I, particularly during the Battle of Verdun

, he was viewed as a national hero in France. With the imminent French defeat in June 1940

, Pétain was appointed Premier of France by President Lebrun at Bordeaux

, and the Cabinet resolved to make peace with Germany. The entire government subsequently moved briefly to Clermont-Ferrand

, then to the spa

town of Vichy

in central France. His government voted to transform the discredited French Third Republic

into the French State

, an authoritarian regime. As the war progressed, the government at Vichy collaborated with the Germans, who in 1942 finally occupied the whole of metropolitan France

because of the threat from North Africa. Petain's actions during World War II

resulted in his conviction and death sentence for treason

, which was commuted to life imprisonment by his former protégé Charles de Gaulle

. In modern France he is remembered as an ambiguous figure, while pétainisme is a derogatory term for certain reactionary

policies.

(in the Pas-de-Calais département in Northern France) in 1856. His father, Omer-Venant was a farmer. His great-uncle, who was a Catholic priest, Father Abbe Lefebvre, had served in Napoleon’s Grande Armée and told the young Petain tales of war and adventure of his campaigns from the peninsulas of Italy to the Alps in Switzerland, Highly impressed by the tales told by his uncle, His destiny was from then on determined, Pétain joined the French Army

in 1876 and attended the St Cyr Military Academy

in 1887 and the École Supérieure de Guerre (army war college) in Paris. His career progressed very slowly, as he rejected the French Army philosophy of the furious infantry assault, arguing instead that "firepower kills." His views were later proved to be correct during the First World War. He was promoted to captain in 1890 and major (Chef de Bataillon) in 1900. Unlike many French officers, he served mainly in mainland France, never Indochina

or any of the African colonies, although he participated in the Rif campaign in Morocco. As colonel

, he commanded the 33rd Infantry Regiment at Arras

from 1911; the young lieutenant Charles de Gaulle

, who served under him, later wrote that his "first colonel, Pétain, taught (him) the Art of Command." In the spring of 1914 he was given command of a brigade (still with the rank of colonel), but having been told he would never become a general, had bought a house pending retirement – he was already 58 years old.

; little over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted again and became XXXIII Corps commander. After leading his corps in the spring 1915 Artois Offensive

, in July 1915 he was given command of the Second Army

, which he led in the Champagne Offensive

that autumn. He acquired a reputation as one of the more successful commanders on the Western Front.

Pétain commanded the Second Army

at the start of the Battle of Verdun

in February 1916. During the battle he was promoted to Commander of Army Group Centre, which contained a total of 52 divisions. Rather than holding down the same infantry divisions on the Verdun battlefield for months, akin to the German system, he rotated them out after only two weeks on the front lines. His decision to organize truck transport over the "Voie Sacrée

" to bring a continuous stream of artillery, ammunition and fresh troops into besieged Verdun also played a key role in grinding down the German onslaught to a final halt in July 1916. In effect, he applied the basic principle that was a mainstay of his teachings at the École de Guerre (War College) before World War I: "le feu tue!" or "firepower kills!"—in this case meaning French field artillery, which fired over 15 million shells on the Germans during the first five months of the battle. Although Pétain did say "On les aura!" (an echoing of Joan of Arc, roughly: "We'll get them!") , the other famous quotation often attributed to him – "Ils ne passeront pas!" ("They shall not pass

"!) – was actually uttered by Robert Nivelle

who succeeded him in command of the Second Army

at Verdun in May, 1916. At the very end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted over Petain to replace Joseph Joffre

as French Commander-in-Chief

.

Because of his high prestige as a soldier's soldier, Pétain served briefly as Army Chief of Staff

(from the end of April 1917). He then became Commander-in-Chief

of the French army, replacing General Nivelle, whose Chemin des Dames

offensive failed in April 1917, thereby provoking widespread mutinies

in the French Army. Pétain put an end to the mutinies by selective punishment of ringleaders, but also by improving the soldiers' conditions (e.g. better food and shelter, and more leaves to visit their families), and promising that men's lives would not be squandered in fruitless offensives. Pétain conducted some successful but limited offensives in the latter part of 1917, unlike the British who stalled in an unsuccessful offensive at Passchendaele that autumn. Pétain, instead, held off from major French offensives until the Americans arrived in force on the front lines, which did not happen until the early summer of 1918. He was also waiting for the new Renault FT17 tanks to be introduced in large numbers, hence his statement at the time: "I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans."

1918 saw major German offensives on the Western Front

. The first of these, Operation Michael

in March 1918, threatened to split the British and French forces apart, and, after he had threatened to retreat on Paris, Pétain came to the aid of the British and secured the front with forty French divisions. Petain proved a capable opponent of the Germans both in defence and through counter-attack.

The crisis led to the appointment of Ferdinand Foch

as Allied Generalissimo

, initially with powers to co-ordinate and deploy Allied reserves where he saw fit. The third offensive, "Blücher," in May 1918, saw major German advances on the Aisne

, as the French Army commander (Humbert) ignored Pétain's instructions to defend in depth and instead allowed his men to be hit by the initial massive German bombardment.

By the time of the last German offensives, Gneisenau and the Second Battle of the Marne

, Pétain was able to defend in depth and launch counter offensives, with the new French tanks and the assistance of the Americans.

Later in the year, Pétain was stripped of his right of direct appeal to the French government and requested to report to Foch, who increasingly assumed the co-ordination and ultimately the command of the Allied offensives.

Pétain was made Marshal of France

in November 1918.

Pétain ended the war regarded "without a doubt, the most accomplished defensive tactician of any army" and "one of France’s greatest military heroes" and was made a Marshal of France at Metz by President Raymond Poincaré

on 8 December 1918. He was subsequently summoned to be present at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles

on 28 June 1919, and was afterwards appointed to France’s "top military job as Vice-Chairman of the revived 'Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre'".

He was encouraged to go into politics although he protested that he had little interest in running for an elected position. He nevertheless tried and failed to get himself elected President following the November 1919 elections. Pétain had placed before the government plans for a large tank and air force but "at the meeting of the 'Conseil Supérier de la Défense Nationale' of 12 March 1920 the Finance Minister, Francois Marsal, announced that although Pétain’s proposals were excellent they were unaffordable". In addition, Marsal announced reductions – in the army from fifty-five divisions to thirty, in the air force, and didn't even mention tanks. It was left to the Marshals, Pétain, Joffre and Foch to pick up the pieces of their strategies. The General Staff, now under General Edmond Buat, now began to think seriously about a line of forts along the frontier with Germany, and their report was tabled on 22 May 1922. The three Marshalls supported this. The cuts in military expenditure meant that taking the offensive was now impossible and a defensive strategy was all they could have.

Pétain was appointed Inspector-General of the Army in February 1922 and produced, in concert with the new Chief of the General Staff, General Marie-Eugéne Debeney

, the new army manual entitled Provisional Instruction on the Tactical Employment of Large Units, which soon became known as 'the Bible'. On 3 September 1925 Pétain was appointed sole Commander-in-Chief of French Forces in Morocco

to launch a major campaign against the Rif tribes, in concert with the Spanish Army, which was successfully concluded by the end of October. He was subsequently decorated, at Toledo

, by King Alfonso XIII with the Spanish Medalla Militar.

In 1924 the National Assembly was elected on a platform of reducing the length of national service to one year, to which Pétain was almost violently opposed. In January 1926 the Chief of Staff, General Debeney, proposed to the 'Conseil' a "totally new kind of army. Only 20 infantry divisions would be maintained on a standing basis". Reserves could be called up when needed. The 'Conseil' had no option in the straitened circumstances but to agree. Pétain, of course, disapproved of the whole thing, pointing out that North Africa still had to be defended and in itself required a substantial standing army. But he recognised, after the new Army Organisation Law of 1927, that the tide was flowing against him. He would not forget that the Radical leader, Édouard Daladier

, even voted against the whole package, on the grounds that the Army was still too large.

On 5 December 1925, after the Locarno Treaty, the 'Conseil' demanded immediate action on a line of fortifications along the eastern frontier to counter the already proposed decline in manpower. A new Commission for this purpose was established, under Joseph Joffre

, and called for reports. In July 1927 Pétain himself went to reconnoitre the whole area. He returned with a revised plan and the Commission then proposed two fortified regions. The Maginot Line

, as it came to be called, (named after André Maginot

the former Minister of War) thereafter occupied a good deal of Pétain’s attention during 1928, when he also travelled extensively, visiting military installations up and down the country. Pétain had based his strong support for the Maginot Line on his own experience of the role played by the forts during the Battle of Verdun

in 1916.

Captain Charles de Gaulle

continued to be a protégé of Pétain throughout these years. He even named his eldest son after the Marshal before finally falling out over the authorship of a book he had said he had ghost-written for Pétain. Pétain finally retired as Inspector-General of the Army, aged 75, in 1931, the year he was elected a Fellow of the Académie française

.

In 1928 Pétain had supported the creation of an independent air force removed from the control of the army, and on 9 February 1931 he was appointed Inspector-General of Air Defence. His first report on air defence, submitted in July that year, advocated increased expenditure. By 1932 economic skies had darkened and Édouard Herriot’s government had made "severe cuts in the defence budget.....orders for new weapons systems all but dried up". Summer manoeuvres in 1932 and 1933 were cancelled due to lack of funds, and recruitment to the armed forces fell off. In the latter year General Weygand claimed that "the French Army was no longer a serious fighting force". Edouard Daladier

’s new government retaliated to Weygand by reducing the number of officers and cutting military pensions and pay, arguing that such measures, apart from financial stringency, were in the spirit of the Geneva Disarmament Conference.

Political unease was sweeping the country, and on 6 February 1934 the Paris police fired on a group of riot

ers outside the Chamber of Deputies, killing 14 and wounding a further 236. President Lebrun invited 71-year-old Doumergue to come out of retirement and form a new "government of national unity". Maréchal Pétain was invited, on 8 February, to join the new French cabinet as Minister of War, which he only reluctantly accepted after many representations. His important success that year was in getting Daladier’s previous proposal to reduce the number of officers repealed. He improved the recruitment programme for specialists, and lengthened the training period by reducing leave entitlements. However Weygand reported to the Senate Army Commission that year that the French Army could still not resist a German attack. Generals Louis Franchet d'Espèrey and Hubert Lyautey

(the latter suddenly died in July) added their names to the report. After the Autumn manoeuvres, which Pétain had reinstated, a report was presented to Pétain that officers had been poorly instructed, had little basic knowledge, and no confidence. He was told, in addition, by Maurice Gamelin

, that if the plebiscite in the Territory of the Saar Basin

went for Germany it would be a serious military error for the French Army to intervene. Pétain responded by again petitioning the government for further funds for the army. During this period, he repeatedly called for a lengthening of the term of compulsory military service for draftees entering the military service, from two to three years, to no avail.

Pétain accompanied President Lebrun to Belgrade

for the funeral of King Alexander

, who had been assassinated on 6 October in Marseille

by a Croatia

n nationalist. Here he met Hermann Göring

and the two men reminisced about their experiences in The Great War. "When Goering returned to Germany he spoke admiringly of Pétain, describing him as a 'man of honour'".

In November the Doumergue government fell. Pétain had previously expressed interest in being named Minister of Education (as well as of War), a role in which he hoped to combat what he saw as the decay in French moral values. Now, however, he refused to continue in Flandin’s (short-lived) government as Minister of War and stood down – in spite of a direct appeal from Lebrun himself. Interestingly, at this moment an article appeared in Le Petit Journal, a popular newspaper, calling for Pétain as a candidate for a dictator

ship. 200,000 readers responded to the paper’s poll. Pétain came first, with 47,000, ahead of Pierre Laval

’s 31,000 votes. These two men travelled to Warsaw for the funeral of the Polish Marshal Pilsudski in May (and another cordial meeting with Goering).

He remained on the High Military Committee. Weygand had been at the British Army 1934 manoeuvres at Tidworth

in June and was appalled by what he had seen. Addressing the Committee on the 23rd, Pétain claimed that it would be fruitless to look for assistance to Britain in the event of a German attack. On 1 March 1935 Pétain’s famous article appeared in the Revue des deux mondes

where he reviewed the history of the army since 1927–28. He criticised the Militia (reservist) system in France, and her lack of adequate air power and armour. This article appeared just five days before Adolf Hitler

’s announcement of Germany’s new air force and a week before the announcement that Germany was increasing its army to 36 divisions.

On 26 April 1936 the General Election results showed 5.5 million votes for The Left against 4.5 million for The Right on an 84% turnout. On 3 May Pétain was interviewed in Le Journal where he launched into an attack on the Franco-Soviet Pact, on Communism in general (France had the largest Communist Party in Western Europe), and on those who allowed Communists intellectual responsibility. He said that France had lost faith in her destiny. Pétain was now in his 80th year.

Some have argued, that Pétain, as France's most senior soldier after Foch's death, should bear some responsibility for the poor state of French weaponry preparation before World War II. But this is unfair as the Marshal was only one of many military and other men on a very large committee responsible for national defence. The interwar years were lean, to say the least, and governments constantly cut military budgets. In addition, with the restrictions imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty there seemed no urgency for vast expenditure until the advent of Hitler. It is argued that whilst Pétain supported the massive use of tanks he saw them mostly as infantry support, leading to the fragmentation of the French tank force into many types of unequal value spread out between mechanized cavalry (such as the SOMUA S-35

) and infantry support (mostly the Renault R35 tanks and the Char B1 bis). Modern infantry rifles and machine guns were not manufactured, with the sole exception of a light machine-rifle, the Mle 1924. The French heavy machine gun was still the Hotchkiss M1914, a capable weapon but decidedly obsolete compared to the new automatic weapons of German infantry. A modern infantry rifle was adopted in 1936 but very few of these MAS-36 rifles had been issued to the troops by 1940. A well-tested French semiautomatic rifle, the MAS 1938–39, was ready for adoption but it never reached the production stage until after World War II as the MAS 49. As to French artillery it had, basically, not been modernized since 1918. The result of all these failings is that the French Army had to face the invading enemy in 1940, with the dated weaponry of 1918. Petain had been made, briefly, Minister of War in 1934, thus ministerially responsible for French military, aviation and the Navy as well. Yet his short period of total responsibility could not reverse 15 years of inactivity and constant cutbacks. The War Ministry was hamstrung between the wars and proved unequal to the tasks before them. French aviation entered the War in 1939 without even the prototype of a bomber aeroplane capable of reaching Berlin and coming back. French industrial efforts in fighter aircraft were dispersed among several firms (Dewoitine

, Morane-Saulnier and Marcel Bloch), each with its own model. On the naval front, France had purposely overlooked building modern aircraft carriers and focused instead on four new conventional battleships, not unlike the German Navy.

On 24 May 1940, the invading Germans pushed back the French Army. General Maxime Weygand

On 24 May 1940, the invading Germans pushed back the French Army. General Maxime Weygand

expressed his fury at British retreats and the unfulfilled promise of British fighter airplanes. He and Pétain regarded the military situation as hopeless. Paul Reynaud

subsequently stated before a parliamentary commission of inquiry in December 1950 that he said, as Premier of France to Pétain on that day that they must seek an armistice. Weygand said that he was in favor of saving the French army and that he “wished to avoid internal troubles and above all anarchy”. Churchill’s man in Paris, Spears, kept up continual pressure on the French, and on 31 May he met with Pétain and threatened France with not only a blockade, but bombardment of the French ports if an armistice was agreed. Spears reported that Pétain did not respond immediately but stood there "perfectly erect, with no sign of panic or emotion. He did not disguise the fact that he considered the situation catastrophic. I could not detect any sign in him of broken morale, of that mental wringing of hands and incipient hysteria noticeable in others". Pétain later remarked to Reynaud about this threat, saying "your ally now threatens us".

On 5 June, following the fall of Dunkirk, there was a Cabinet reshuffle, and Prime Minister Reynaud brought Pétain, Weygand, and the newly promoted Brigadier-General de Gaulle

, whose 4th Armoured Division had launched one of the few French counterattacks the previous month, into his War Cabinet, hoping that the trio might instill a renewed spirit of resistance and patriotism in the French Army. On 8 June, Baudouin dined with Chautemps, and both declared that the war must end. Paris was now threatened, and the government was preparing to depart, although Pétain was opposed to such a move. During a cabinet meeting that day, Reynaud argued for an armistice, as he was worried about England. Pétain replied that "the interests of France come before those of England. England got us into this position, let us now try to get out of it".

On 10 June, the government left Paris for Tours. Weygand, the Commander-in-Chief, now declared that “the fighting had become meaningless”. He, Baudouin, and several members of the government were already set on an armistice. On 11 June, Churchill flew to the Château du Muguet, at Briar, near Orleans

, where he put forward first his idea of a Breton

redoubt, to which Weygand replied that it was just a "fantasy". Churchill then said the French should consider "guerrilla warfare" until the Americans came into the war, to which several cabinet members asked "when might that be" and received no reply. Pétain then replied that it would mean the destruction of the country. Churchill then said the French should defend Paris and repeated Clemenceau’s words "I will fight in front of Paris, in Paris, and behind Paris". To this, Churchill subsequently reported, Pétain replied quietly and with dignity that he had in those days a strategic reserve of sixty divisions; now, there was none. Making Paris into a ruin would not affect the final event. The following day, the cabinet met and Weygand again called for an armistice. He referred to the danger of military and civil disorder and the possibility of a Communist uprising in Paris. Pétain and Minister of Information Prouvost urged the Cabinet to hear Weygand out because "he was the only one really to know what was happening".

Churchill returned to France on the 13th. Paul Baudouin met his plane and immediately spoke to him of the hopelessness of further French resistance. Reynard, then, put the cabinet’s armistice proposals to Churchill, who replied that "whatever happened, we would level no reproaches against France". At that day’s Cabinet meeting, Pétain read out a draft proposal to the Cabinet where he spoke of "the need to stay in France, to prepare a national revival, and to share the sufferings of our people. It is impossible for the Government to abandon French soil without emigrating, without deserting. The duty of the Government is, come what may, to remain in the country, or it could not longer be regarded as the government". Several ministers were still opposed to an armistice, and Weygand immediately lashed out at them for even leaving Paris. Like Pétain, he said he would never leave France.

The government moved to Bordeaux

, where French Governments had fled German invasions in 1870 and 1914, on 14 June. Parliament, both Senate and Chamber, were also there and immersed themselves in the armistice debate. Reynard’s ambiguous position was becoming seriously compromised. Admiral Darlan was by now in the armistice camp also. Reynard proposed an alternative compromise: Complete surrender, and the army (after laying down its arms) to leave the country and continue the fight from abroad. Weygand exploded and he and Pétain both said that such a capitulation would be dishonourable. The Cabinet was now split almost evenly. Camille Chautemps

said the only way to get agreement was to ask the Germans what their terms for an armistice would be and the cabinet voted 13 – 6 in agreement.

The next day, Roosevelt’s reply to President Lebrun’s requests for assistance came with only vague promises and saying that it was impossible for the President to do anything without Congress.

After lunch, President Albert Lebrun

received two telegrams from the British saying they would only agree to an armistice if the French fleet was immediately sent to British ports. In addition, the British Government offered joint nationality for Frenchmen and Englishmen in a Franco-British Union. Reynaud and five ministers thought these proposals acceptable. The others did not, seeing the offer as insulting and a device to make France subservient to Great Britain, in a kind of extra Dominion. Reynaud gave up and asked President Lebrun to accept his resignation as Prime Minister and nominated Maréchal Pétain in his place.

A new Cabinet was formed in the normal way, and, at midnight on the 15th, Baudouin was asking the Spanish Ambassador to submit to Germany a request to cease hostilities at once and for Germany to make known its peace terms. At 12:30 am, Maréchal Pétain made his first broadcast to the French people.

"The enthusiasm of the country for the Maréchal was tremendous. He was welcomed by people as diverse as Claudel

, Gide

, and Mauriac

, and also by the vast mass of untutored Frenchmen who saw him as their saviour." General de Gaulle, no longer in the Cabinet, had arrived in London on the 16th and made a call for resistance from there, on the 18th, with no legal authority whatsoever from his government, a call that was heeded by comparatively few.

Cabinet and Parliament still argued between themselves on the question of whether or not to retreat to North Africa. On 18 June, Edouard Herriot

(who would later be a –discredited– prosecution witness at Pétain's trial) and Jeanneney, the Presidents of the two Chambers of Parliament, as well as Lebrun said they wanted to go. Pétain said he was not departing. On the 20th, a delegation from the two chambers came to Pétain to protest at the proposed departure of President Lebrun. The next day, they went to Lebrun himself. In the event, only 26 deputies and 1 senator headed for Africa, amongst them Georges Mandel

, Pierre Mendès France, and the former Popular Front Education Minister, Jean Zay

, all of whom had Jewish backgrounds. Pétain broadcast again to the French people on that day.

On 22 June, France signed an armistice

with Germany that gave Germany control over the north and west of the country, including Paris and all of the Atlantic coastline, but left the rest, around two-fifths of France's prewar territory, unoccupied. Paris remained the de jure capital. On 29 June, the French Government moved to Clermont-Ferrand

where the first discussions of constitutional changes were mooted, with Pierre Laval

having personal discussions with President Lebrun, who had, in the event, not departed France. On 1 July, the government, finding Clermont too cramped, moved to the spa

town of Vichy

, at Baudouin’s suggestion, the empty hotels there being more suitable for the government ministries.

The Chamber of Deputies and Senate, meeting together as a "Congrès," held an emergency meeting on 10 July to ratify the armistice. At the same time, the draft constitutional proposals were tabled. The Presidents of both Chambers spoke and declared that constitutional reform was necessary. The Congress voted 569-80 (with 18 abstentions) to grant the Cabinet the authority to draw up a new constitution, effectively "voting the Third Republic out of existence". Nearly all French historians, as well as all postwar French governments, consider this vote to be illegal; not only were several deputies and senators not present, but the constitution explicitly stated that the republican form of government could not be changed. On the next day, Pétain formally assumed near-absolute powers as "Head of State", though he stated at the time "this is not ancient Rome and I have no wish to be Caesar".

Pétain was reactionary by temperament and education, and quickly began blaming the Third Republic and its endemic corruption for the French defeat. His regime soon took on clear authoritarian -and in some cases, fascist- characteristics. The republican motto of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité

" was replaced with "Travail, famille, patrie

" ("Work, family, fatherland"). Fascistic and revolutionary conservative factions within the new government used the opportunity to launch an ambitious program known as the "National Revolution," which rejected much of the former Third Republic's secular and liberal traditions in favour of an authoritarian, paternalist, Catholic society. Pétain, amongst others, took exception to the use of the inflammatory term "revolution" to describe an essentially conservative movement, but otherwise participated in the transformation of French society from "Republic" to "State." He added that the new France would be "a social hierarchy...rejecting the false idea of the natural equality of men."

The new government immediately used its new powers to order harsh measures, including the dismissal of republican civil servants, the installation of exceptional jurisdictions, the proclamation of antisemitic laws, and the imprisonment of opponents and foreign refugees. Censorship

was imposed, and freedom of expression and thought

were effectively abolished with the reinstatement of the crime of "felony of opinion."

The regime organised a "Légion Française des Combattants," which included "Friends of the Legion" and "Cadets of the Legion," groups of those who had never fought but were politically attached to the new regime. Pétain championed a rural, Catholic France that spurned internationalism. As a retired military commander, he ran the country on military lines. He and his government collaborated with Germany and even produced a legion of volunteers to fight in Russia. Pétain's government was nevertheless internationally recognized, notably by the USA, at least until the German occupation of the rest of France

.

Neither Pétain nor his successive deputies, Pierre Laval

, Pierre-Étienne Flandin or Admiral François Darlan

, gave significant resistance to requests by the Germans to indirectly aid the Axis Powers

. Yet, when Hitler met Pétain at Montoire in October 1940 to discuss the French government's role in the new European Order, the Marshal "listened to Hitler in silence. Not once did he offer a sympathetic word for Germany." Furthermore, France remained neutral as a state, albeit opposed to the British organized Free French. After the British attack on 2 July 1940 Mers el Kébir

and Dakar

, the French government became increasingly Anglophobic and took the initiative to collaborate with the occupiers. Pétain accepted the government's creation of a collaborationist armed militia (the Milice

) under the command of Joseph Darnand

, who, along with German forces, led a campaign of repression against French resistance ("Maquis

"), notably its Communist factions.

The honours that Darnand acquired included SS-Major

. Pétain admitted Darnand into his government as Secretary of the Maintenance of Public Order (Secrétaire d'État au Maintien de l'Ordre). In August 1944, Pétain made an attempt to distance himself from the crimes of the militia by writing Darnand a letter of reprimand

for the organisation's "excesses". The latter wrote a sarcastic reply, telling Pétain that he should have "thought of this before".

Pétain's government acquiesced to the Axis forces demands for large supplies of manufactured goods and foodstuffs, and also ordered French troops in France's colonial empire

(in Dakar, Syria, Madagascar, Oran and Morocco) to defend sovereign French territory against any aggressors, Allied or otherwise.

Pétain's motives are a topic of wide conjecture. Winston Churchill

had spoken to M. Reynaud during the impending fall of France, saying of Pétain, "...he had always been a defeatist, even in the last war [World War I]."

On 11 November 1942, German forces invaded the unoccupied zone of Southern France in response to the Alliies' Operation Torch

landings in North Africa and Admiral François Darlan

's agreement to support the Allies. Although the French government nominally remained in existence, civilian administration of almost all France being under it, Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead

, as the Germans had negated the pretence of an "independent" government at Vichy. Pétain however remained popular and engaged on a series of visits around France as late as 1944, when he arrived in Paris on 28 April in what the newsreels described as a "historic" moment for the city. Vast crowds cheered him in front of the Hotel de Ville and in the streets.

After the liberation of France, on 7 September 1944, Pétain and other members of the French cabinet at Vichy were relocated by the Germans to Sigmaringen

in Germany, where they became a government-in-exile until April 1945. Pétain, however, having been forced to leave France, refused to participate and the 'government commission' became headed by Fernand de Brinon

. In a note dated 29 October 1944, Pétain forbade de Brinon to use the Marshall's name in any connection with this new government, and, on 5 April 1945, Pétain wrote a note to Hitler expressing his wish to return to France. No reply ever came. However, on his birthday 19 days later, he was taken to the Swiss border. Two days later he crossed into the French frontier.

. He remained silent through most of the proceedings, after an initial statement that denied the right of the High Court, as presently constituted, to try him. De Gaulle himself was later to criticise the trial, saying: "Too often, the discussions took on the appearance of a partisan trial, sometimes even a settling of accounts, when the whole affair should only have been treated from the point of view of national defence and independence."

At the end of Petain's trial, although the three judges proposed Pétain's acquittal on all the charges laid against him, the jury convicted him and passed a death sentence by a majority of one. On account of Petain's age the Court asked that the verdict should not be executed. De Gaulle, who was President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic

at the end of the war, commuted it to life imprisonment on the grounds of Pétain's age and his World War I contributions.

Pétain was nevertheless stripped of all his military ranks and honours except that of Marshal of France

(because Maréchal is a distinction conferred by a special personal law passed by the French Parliament, and under the principle of separation of powers

a court does not have the power to reverse a law passed by Parliament).

De Gaulle, fearing riots at the announcement of the sentence, had Pétain removed immediately, on his (de Gaulle's) own private aircraft, to Fort du Portalet

in the Pyrenees

, where he remained from 15 August to 16 November 1945. Later he was imprisoned in the Forte de Pierre citadel on the Île d'Yeu

, an island off the Atlantic coast where his physical and mental condition deteriorated to the point where he required round-the-clock nursing care. He died at Île d'Yeu on July 23, 1951, at the age of 95. His body is buried at a marine cemetery (Cimetière communal de Port-Joinville) near the prison. Calls are sometimes made to re-inter his remains in the grave prepared for him at Verdun

.

In 1973, Petain's coffin was stolen from the Ile d'Yeu Cemetery by extremists who demanded that French president Georges Pompidou consent to Petain's reburial at Douaumont Cemetery among the war dead. One week later, Petain's coffin was found in a garage in Paris, and those responsible for the grave robbery were arrested. Petain was ceremoniously reburied with a Presidential wreath on his coffin, but as before, on the Ile d'Yeu prison island.

Mount Pétain

, nearby Pétain Creek and Pétain Falls forming the Pétain Basin on the Continental Divide in the Canadian Rockies

were named after him in 1919; summits with the names of other French generals are nearby: Foch

, Cordonnier

, Mangin

, Castelnau and Joffre

.

Changes

Changes

Changes

Marshal of France

The Marshal of France is a military distinction in contemporary France, not a military rank. It is granted to generals for exceptional achievements...

, and was later Chief of State

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

of Vichy France

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

(Chef de l'État Français), from 1940 to 1944. Pétain, who was 84 years old in 1940, ranks as France's oldest head of state.

Because of his outstanding military leadership in World War I, particularly during the Battle of Verdun

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February – 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France...

, he was viewed as a national hero in France. With the imminent French defeat in June 1940

Battle of France

In the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb , German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and...

, Pétain was appointed Premier of France by President Lebrun at Bordeaux

Bordeaux

Bordeaux is a port city on the Garonne River in the Gironde department in southwestern France.The Bordeaux-Arcachon-Libourne metropolitan area, has a population of 1,010,000 and constitutes the sixth-largest urban area in France. It is the capital of the Aquitaine region, as well as the prefecture...

, and the Cabinet resolved to make peace with Germany. The entire government subsequently moved briefly to Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand is a city and commune of France, in the Auvergne region, with a population of 140,700 . Its metropolitan area had 409,558 inhabitants at the 1999 census. It is the prefecture of the Puy-de-Dôme department...

, then to the spa

Spa

The term spa is associated with water treatment which is also known as balneotherapy. Spa towns or spa resorts typically offer various health treatments. The belief in the curative powers of mineral waters goes back to prehistoric times. Such practices have been popular worldwide, but are...

town of Vichy

Vichy

Vichy is a commune in the department of Allier in Auvergne in central France. It belongs to the historic province of Bourbonnais.It is known as a spa and resort town and was the de facto capital of Vichy France during the World War II Nazi German occupation from 1940 to 1944.The town's inhabitants...

in central France. His government voted to transform the discredited French Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

into the French State

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

, an authoritarian regime. As the war progressed, the government at Vichy collaborated with the Germans, who in 1942 finally occupied the whole of metropolitan France

Metropolitan France

Metropolitan France is the part of France located in Europe. It can also be described as mainland France or as the French mainland and the island of Corsica...

because of the threat from North Africa. Petain's actions during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

resulted in his conviction and death sentence for treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

, which was commuted to life imprisonment by his former protégé Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

. In modern France he is remembered as an ambiguous figure, while pétainisme is a derogatory term for certain reactionary

Reactionary

The term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

policies.

Early life

Pétain was born in Cauchy-à-la-TourCauchy-à-la-Tour

Cauchy-à-la-Tour is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France.-Geography:A farming and ex-coalmining village some southwest of Béthune and southwest of Lille, at the junction of the D183 and the D341 roads....

(in the Pas-de-Calais département in Northern France) in 1856. His father, Omer-Venant was a farmer. His great-uncle, who was a Catholic priest, Father Abbe Lefebvre, had served in Napoleon’s Grande Armée and told the young Petain tales of war and adventure of his campaigns from the peninsulas of Italy to the Alps in Switzerland, Highly impressed by the tales told by his uncle, His destiny was from then on determined, Pétain joined the French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

in 1876 and attended the St Cyr Military Academy

École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr

The École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr is the foremost French military academy. Its official name is . It is often referred to as Saint-Cyr . Its motto is "Ils s'instruisent pour vaincre": literally "They study to vanquish" or "Training for victory"...

in 1887 and the École Supérieure de Guerre (army war college) in Paris. His career progressed very slowly, as he rejected the French Army philosophy of the furious infantry assault, arguing instead that "firepower kills." His views were later proved to be correct during the First World War. He was promoted to captain in 1890 and major (Chef de Bataillon) in 1900. Unlike many French officers, he served mainly in mainland France, never Indochina

Indochina

The Indochinese peninsula, is a region in Southeast Asia. It lies roughly southwest of China, and east of India. The name has its origins in the French, Indochine, as a combination of the names of "China" and "India", and was adopted when French colonizers in Vietnam began expanding their territory...

or any of the African colonies, although he participated in the Rif campaign in Morocco. As colonel

Colonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

, he commanded the 33rd Infantry Regiment at Arras

Arras

Arras is the capital of the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France. The historic centre of the Artois region, its local speech is characterized as a Picard dialect...

from 1911; the young lieutenant Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

, who served under him, later wrote that his "first colonel, Pétain, taught (him) the Art of Command." In the spring of 1914 he was given command of a brigade (still with the rank of colonel), but having been told he would never become a general, had bought a house pending retirement – he was already 58 years old.

World War I

At the end of August 1914 he was quickly promoted to brigadier-general and given command of the 6th Division in time for the First Battle of the MarneFirst Battle of the Marne

The Battle of the Marne was a First World War battle fought between 5 and 12 September 1914. It resulted in an Allied victory against the German Army under Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. The battle effectively ended the month long German offensive that opened the war and had...

; little over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted again and became XXXIII Corps commander. After leading his corps in the spring 1915 Artois Offensive

Second Battle of Artois

The Second Battle of Artois, of which the British contribution was the Battle of Aubers Ridge, was a battle on the Western Front of the First World War, it was fought at the same time as the Second Battle of Ypres. Even though the French under General Philippe Pétain gained some initial victories,...

, in July 1915 he was given command of the Second Army

Second Army (France)

The Second Army was a Field army of the French Army during World War I and World War II. The Army became famous for fighting the Battle of Verdun in 1916 under Philippe Pétain.-World War I:*General de Curières de Castelnau...

, which he led in the Champagne Offensive

Second Battle of Champagne

The Second Battle of Champagne was a French offensive against the invading German army beginning on 25 September 1915, part of World War I.-September 25 - October 6:...

that autumn. He acquired a reputation as one of the more successful commanders on the Western Front.

Pétain commanded the Second Army

Second Army (France)

The Second Army was a Field army of the French Army during World War I and World War II. The Army became famous for fighting the Battle of Verdun in 1916 under Philippe Pétain.-World War I:*General de Curières de Castelnau...

at the start of the Battle of Verdun

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February – 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France...

in February 1916. During the battle he was promoted to Commander of Army Group Centre, which contained a total of 52 divisions. Rather than holding down the same infantry divisions on the Verdun battlefield for months, akin to the German system, he rotated them out after only two weeks on the front lines. His decision to organize truck transport over the "Voie Sacrée

Voie Sacrée

The Voie Sacrée is a road that connects Bar-le-Duc to Verdun , France. It was given its name after the end of World War I because of the vital role it played during the Battle of Verdun.-History:...

" to bring a continuous stream of artillery, ammunition and fresh troops into besieged Verdun also played a key role in grinding down the German onslaught to a final halt in July 1916. In effect, he applied the basic principle that was a mainstay of his teachings at the École de Guerre (War College) before World War I: "le feu tue!" or "firepower kills!"—in this case meaning French field artillery, which fired over 15 million shells on the Germans during the first five months of the battle. Although Pétain did say "On les aura!" (an echoing of Joan of Arc, roughly: "We'll get them!") , the other famous quotation often attributed to him – "Ils ne passeront pas!" ("They shall not pass

They shall not pass

"They shall not pass" is a slogan used to express determination to defend a position against an enemy.It was most famously used during the Battle of Verdun in World War I by French General Robert Nivelle...

"!) – was actually uttered by Robert Nivelle

Robert Nivelle

Robert Georges Nivelle was a French artillery officer who served in the Boxer Rebellion, and the First World War. In May 1916, he was given command of the French Third Army in the Battle of Verdun, leading counter-offensives that rolled back the German forces in late 1916...

who succeeded him in command of the Second Army

Second Army (France)

The Second Army was a Field army of the French Army during World War I and World War II. The Army became famous for fighting the Battle of Verdun in 1916 under Philippe Pétain.-World War I:*General de Curières de Castelnau...

at Verdun in May, 1916. At the very end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted over Petain to replace Joseph Joffre

Joseph Joffre

Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre OM was a French general during World War I. He is most known for regrouping the retreating allied armies to defeat the Germans at the strategically decisive First Battle of the Marne in 1914. His popularity led to his nickname Papa Joffre.-Biography:Joffre was born in...

as French Commander-in-Chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

.

Because of his high prestige as a soldier's soldier, Pétain served briefly as Army Chief of Staff

Chief of Staff

The title, chief of staff, identifies the leader of a complex organization, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a Principal Staff Officer , who is the coordinator of the supporting staff or a primary aide to an important individual, such as a president.In general, a chief of...

(from the end of April 1917). He then became Commander-in-Chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

of the French army, replacing General Nivelle, whose Chemin des Dames

Chemin des Dames

In France, the Chemin des Dames is part of the D18 and runs east and west in the département of Aisne, between in the west, the Route Nationale 2, and in the east, the D1044 at Corbeny. It is some thirty kilometres long and runs along a ridge between the valleys of the rivers Aisne and Ailette...

offensive failed in April 1917, thereby provoking widespread mutinies

Mutiny

Mutiny is a conspiracy among members of a group of similarly situated individuals to openly oppose, change or overthrow an authority to which they are subject...

in the French Army. Pétain put an end to the mutinies by selective punishment of ringleaders, but also by improving the soldiers' conditions (e.g. better food and shelter, and more leaves to visit their families), and promising that men's lives would not be squandered in fruitless offensives. Pétain conducted some successful but limited offensives in the latter part of 1917, unlike the British who stalled in an unsuccessful offensive at Passchendaele that autumn. Pétain, instead, held off from major French offensives until the Americans arrived in force on the front lines, which did not happen until the early summer of 1918. He was also waiting for the new Renault FT17 tanks to be introduced in large numbers, hence his statement at the time: "I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans."

1918 saw major German offensives on the Western Front

Western Front

Western Front was a term used during the First and Second World Wars to describe the contested armed frontier between lands controlled by Germany to the east and the Allies to the west...

. The first of these, Operation Michael

Operation Michael

Operation Michael was a First World War German military operation that began the Spring Offensive on 21 March 1918. It was launched from the Hindenburg Line, in the vicinity of Saint-Quentin, France...

in March 1918, threatened to split the British and French forces apart, and, after he had threatened to retreat on Paris, Pétain came to the aid of the British and secured the front with forty French divisions. Petain proved a capable opponent of the Germans both in defence and through counter-attack.

The crisis led to the appointment of Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch , GCB, OM, DSO was a French soldier, war hero, military theorist, and writer credited with possessing "the most original and subtle mind in the French army" in the early 20th century. He served as general in the French army during World War I and was made Marshal of France in its...

as Allied Generalissimo

Generalissimo

Generalissimo and Generalissimus are military ranks of the highest degree, superior to Field Marshal and other five-star ranks.-Usage:...

, initially with powers to co-ordinate and deploy Allied reserves where he saw fit. The third offensive, "Blücher," in May 1918, saw major German advances on the Aisne

Aisne

Aisne is a department in the northern part of France named after the Aisne River.- History :Aisne is one of the original 83 departments created during the French Revolution on 4 March 1790. It was created from parts of the former provinces of Île-de-France, Picardie, and Champagne.Most of the old...

, as the French Army commander (Humbert) ignored Pétain's instructions to defend in depth and instead allowed his men to be hit by the initial massive German bombardment.

By the time of the last German offensives, Gneisenau and the Second Battle of the Marne

Second Battle of the Marne

The Second Battle of the Marne , or Battle of Reims was the last major German Spring Offensive on the Western Front during the First World War. The German attack failed when an Allied counterattack led by France overwhelmed the Germans, inflicting severe casualties...

, Pétain was able to defend in depth and launch counter offensives, with the new French tanks and the assistance of the Americans.

Later in the year, Pétain was stripped of his right of direct appeal to the French government and requested to report to Foch, who increasingly assumed the co-ordination and ultimately the command of the Allied offensives.

Pétain was made Marshal of France

Marshal of France

The Marshal of France is a military distinction in contemporary France, not a military rank. It is granted to generals for exceptional achievements...

in November 1918.

Between the wars

Pétain was a bachelor until his sixties, and famous for his womanising. Women were said to find his piercing blue eyes especially attractive. At the opening of the Battle of Verdun he is said to have been fetched during the night from a Paris hotel by a staff officer who knew which mistress he could be found with. After the war Pétain married an old lover, "a particularly beautiful woman", Mme. Eugénie Hardon (1877–1962), on 14 September 1920. Hardon had been divorced from François de Hérain in 1914; although the couple were too old to have children (she had a son, Pierre de Hérain, from her first marriage), they remained married until the end of Pétain's life.Pétain ended the war regarded "without a doubt, the most accomplished defensive tactician of any army" and "one of France’s greatest military heroes" and was made a Marshal of France at Metz by President Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France on five separate occasions and as President of France from 1913 to 1920. Poincaré was a conservative leader primarily committed to political and social stability...

on 8 December 1918. He was subsequently summoned to be present at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

on 28 June 1919, and was afterwards appointed to France’s "top military job as Vice-Chairman of the revived 'Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre'".

He was encouraged to go into politics although he protested that he had little interest in running for an elected position. He nevertheless tried and failed to get himself elected President following the November 1919 elections. Pétain had placed before the government plans for a large tank and air force but "at the meeting of the 'Conseil Supérier de la Défense Nationale' of 12 March 1920 the Finance Minister, Francois Marsal, announced that although Pétain’s proposals were excellent they were unaffordable". In addition, Marsal announced reductions – in the army from fifty-five divisions to thirty, in the air force, and didn't even mention tanks. It was left to the Marshals, Pétain, Joffre and Foch to pick up the pieces of their strategies. The General Staff, now under General Edmond Buat, now began to think seriously about a line of forts along the frontier with Germany, and their report was tabled on 22 May 1922. The three Marshalls supported this. The cuts in military expenditure meant that taking the offensive was now impossible and a defensive strategy was all they could have.

Pétain was appointed Inspector-General of the Army in February 1922 and produced, in concert with the new Chief of the General Staff, General Marie-Eugéne Debeney

Marie-Eugène Debeney

Marie-Eugène Debeney was a French Army general. Several streets in his birthplace are named after him-Life:Marie-Eugène Debeney was born in Bourg-en-Bresse, Ain. A student at Saint-Cyr, Marie-Eugène Debeney became Lieutenant des Chasseurs in 1886...

, the new army manual entitled Provisional Instruction on the Tactical Employment of Large Units, which soon became known as 'the Bible'. On 3 September 1925 Pétain was appointed sole Commander-in-Chief of French Forces in Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

to launch a major campaign against the Rif tribes, in concert with the Spanish Army, which was successfully concluded by the end of October. He was subsequently decorated, at Toledo

Toledo, Spain

Toledo's Alcázar became renowned in the 19th and 20th centuries as a military academy. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 its garrison was famously besieged by Republican forces.-Economy:...

, by King Alfonso XIII with the Spanish Medalla Militar.

In 1924 the National Assembly was elected on a platform of reducing the length of national service to one year, to which Pétain was almost violently opposed. In January 1926 the Chief of Staff, General Debeney, proposed to the 'Conseil' a "totally new kind of army. Only 20 infantry divisions would be maintained on a standing basis". Reserves could be called up when needed. The 'Conseil' had no option in the straitened circumstances but to agree. Pétain, of course, disapproved of the whole thing, pointing out that North Africa still had to be defended and in itself required a substantial standing army. But he recognised, after the new Army Organisation Law of 1927, that the tide was flowing against him. He would not forget that the Radical leader, Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier was a French Radical politician and the Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.-Career:Daladier was born in Carpentras, Vaucluse. Later, he would become known to many as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders and determined...

, even voted against the whole package, on the grounds that the Army was still too large.

On 5 December 1925, after the Locarno Treaty, the 'Conseil' demanded immediate action on a line of fortifications along the eastern frontier to counter the already proposed decline in manpower. A new Commission for this purpose was established, under Joseph Joffre

Joseph Joffre

Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre OM was a French general during World War I. He is most known for regrouping the retreating allied armies to defeat the Germans at the strategically decisive First Battle of the Marne in 1914. His popularity led to his nickname Papa Joffre.-Biography:Joffre was born in...

, and called for reports. In July 1927 Pétain himself went to reconnoitre the whole area. He returned with a revised plan and the Commission then proposed two fortified regions. The Maginot Line

Maginot Line

The Maginot Line , named after the French Minister of War André Maginot, was a line of concrete fortifications, tank obstacles, artillery casemates, machine gun posts, and other defences, which France constructed along its borders with Germany and Italy, in light of its experience in World War I,...

, as it came to be called, (named after André Maginot

André Maginot

André Maginot was a French civil servant, soldier, and Member of Parliament. He is undoubtedly best known for his advocacy for the string of forts that would be known as the Maginot Line.- Early years, to World War I :...

the former Minister of War) thereafter occupied a good deal of Pétain’s attention during 1928, when he also travelled extensively, visiting military installations up and down the country. Pétain had based his strong support for the Maginot Line on his own experience of the role played by the forts during the Battle of Verdun

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February – 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France...

in 1916.

Captain Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

continued to be a protégé of Pétain throughout these years. He even named his eldest son after the Marshal before finally falling out over the authorship of a book he had said he had ghost-written for Pétain. Pétain finally retired as Inspector-General of the Army, aged 75, in 1931, the year he was elected a Fellow of the Académie française

Académie française

L'Académie française , also called the French Academy, is the pre-eminent French learned body on matters pertaining to the French language. The Académie was officially established in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister to King Louis XIII. Suppressed in 1793 during the French Revolution,...

.

In 1928 Pétain had supported the creation of an independent air force removed from the control of the army, and on 9 February 1931 he was appointed Inspector-General of Air Defence. His first report on air defence, submitted in July that year, advocated increased expenditure. By 1932 economic skies had darkened and Édouard Herriot’s government had made "severe cuts in the defence budget.....orders for new weapons systems all but dried up". Summer manoeuvres in 1932 and 1933 were cancelled due to lack of funds, and recruitment to the armed forces fell off. In the latter year General Weygand claimed that "the French Army was no longer a serious fighting force". Edouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier was a French Radical politician and the Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.-Career:Daladier was born in Carpentras, Vaucluse. Later, he would become known to many as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders and determined...

’s new government retaliated to Weygand by reducing the number of officers and cutting military pensions and pay, arguing that such measures, apart from financial stringency, were in the spirit of the Geneva Disarmament Conference.

Political unease was sweeping the country, and on 6 February 1934 the Paris police fired on a group of riot

Riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder characterized often by what is thought of as disorganized groups lashing out in a sudden and intense rash of violence against authority, property or people. While individuals may attempt to lead or control a riot, riots are thought to be typically chaotic and...

ers outside the Chamber of Deputies, killing 14 and wounding a further 236. President Lebrun invited 71-year-old Doumergue to come out of retirement and form a new "government of national unity". Maréchal Pétain was invited, on 8 February, to join the new French cabinet as Minister of War, which he only reluctantly accepted after many representations. His important success that year was in getting Daladier’s previous proposal to reduce the number of officers repealed. He improved the recruitment programme for specialists, and lengthened the training period by reducing leave entitlements. However Weygand reported to the Senate Army Commission that year that the French Army could still not resist a German attack. Generals Louis Franchet d'Espèrey and Hubert Lyautey

Hubert Lyautey

Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey was a French Army general, the first Resident-General in Morocco from 1912 to 1925 and from 1921 Marshal of France.-Early life:...

(the latter suddenly died in July) added their names to the report. After the Autumn manoeuvres, which Pétain had reinstated, a report was presented to Pétain that officers had been poorly instructed, had little basic knowledge, and no confidence. He was told, in addition, by Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gustave Gamelin was a French general. Gamelin is best remembered for his unsuccessful command of the French military in 1940 during the Battle of France and his steadfast defense of republican values....

, that if the plebiscite in the Territory of the Saar Basin

Saar (League of Nations)

The Territory of the Saar Basin , also referred as the Saar or Saargebiet, was a region of Germany that was occupied and governed by Britain and France from 1920 to 1935 under a League of Nations mandate, with the occupation originally being under the auspices of the Treaty of Versailles...

went for Germany it would be a serious military error for the French Army to intervene. Pétain responded by again petitioning the government for further funds for the army. During this period, he repeatedly called for a lengthening of the term of compulsory military service for draftees entering the military service, from two to three years, to no avail.

Pétain accompanied President Lebrun to Belgrade

Belgrade

Belgrade is the capital and largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, where the Pannonian Plain meets the Balkans. According to official results of Census 2011, the city has a population of 1,639,121. It is one of the 15 largest cities in Europe...

for the funeral of King Alexander

Alexander I of Yugoslavia

Alexander I , also known as Alexander the Unifier was the first king of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia as well as the last king of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes .-Childhood:...

, who had been assassinated on 6 October in Marseille

Marseille

Marseille , known in antiquity as Massalia , is the second largest city in France, after Paris, with a population of 852,395 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Marseille extends beyond the city limits with a population of over 1,420,000 on an area of...

by a Croatia

Croatia

Croatia , officially the Republic of Croatia , is a unitary democratic parliamentary republic in Europe at the crossroads of the Mitteleuropa, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean. Its capital and largest city is Zagreb. The country is divided into 20 counties and the city of Zagreb. Croatia covers ...

n nationalist. Here he met Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

and the two men reminisced about their experiences in The Great War. "When Goering returned to Germany he spoke admiringly of Pétain, describing him as a 'man of honour'".

In November the Doumergue government fell. Pétain had previously expressed interest in being named Minister of Education (as well as of War), a role in which he hoped to combat what he saw as the decay in French moral values. Now, however, he refused to continue in Flandin’s (short-lived) government as Minister of War and stood down – in spite of a direct appeal from Lebrun himself. Interestingly, at this moment an article appeared in Le Petit Journal, a popular newspaper, calling for Pétain as a candidate for a dictator

Dictator

A dictator is a ruler who assumes sole and absolute power but without hereditary ascension such as an absolute monarch. When other states call the head of state of a particular state a dictator, that state is called a dictatorship...

ship. 200,000 readers responded to the paper’s poll. Pétain came first, with 47,000, ahead of Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively. Following France's Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government, signing orders permitting the deportation of...

’s 31,000 votes. These two men travelled to Warsaw for the funeral of the Polish Marshal Pilsudski in May (and another cordial meeting with Goering).

He remained on the High Military Committee. Weygand had been at the British Army 1934 manoeuvres at Tidworth

Tidworth

Tidworth is a town in south-east Wiltshire, England with a growing civilian population. Situated at the eastern edge of Salisbury Plain, it is approximately 10 miles west of Andover, 12 miles south of Marlborough, 24 miles south of Swindon, 15 miles north by north-east of Salisbury and 6 miles east...

in June and was appalled by what he had seen. Addressing the Committee on the 23rd, Pétain claimed that it would be fruitless to look for assistance to Britain in the event of a German attack. On 1 March 1935 Pétain’s famous article appeared in the Revue des deux mondes

Revue des deux mondes

The Revue des deux Mondes is a French language monthly literary and cultural affairs magazine that has been published in Paris since 1829....

where he reviewed the history of the army since 1927–28. He criticised the Militia (reservist) system in France, and her lack of adequate air power and armour. This article appeared just five days before Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

’s announcement of Germany’s new air force and a week before the announcement that Germany was increasing its army to 36 divisions.

On 26 April 1936 the General Election results showed 5.5 million votes for The Left against 4.5 million for The Right on an 84% turnout. On 3 May Pétain was interviewed in Le Journal where he launched into an attack on the Franco-Soviet Pact, on Communism in general (France had the largest Communist Party in Western Europe), and on those who allowed Communists intellectual responsibility. He said that France had lost faith in her destiny. Pétain was now in his 80th year.

Some have argued, that Pétain, as France's most senior soldier after Foch's death, should bear some responsibility for the poor state of French weaponry preparation before World War II. But this is unfair as the Marshal was only one of many military and other men on a very large committee responsible for national defence. The interwar years were lean, to say the least, and governments constantly cut military budgets. In addition, with the restrictions imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty there seemed no urgency for vast expenditure until the advent of Hitler. It is argued that whilst Pétain supported the massive use of tanks he saw them mostly as infantry support, leading to the fragmentation of the French tank force into many types of unequal value spread out between mechanized cavalry (such as the SOMUA S-35

Somua S-35

The SOMUA S35 was a French Cavalry tank of the Second World War. Built from 1936 until 1940 to equip the armoured divisions of the Cavalry, it was for its time a relatively agile medium-weight tank, superior in armour and armament to both its French and foreign competitors, such as the contemporary...

) and infantry support (mostly the Renault R35 tanks and the Char B1 bis). Modern infantry rifles and machine guns were not manufactured, with the sole exception of a light machine-rifle, the Mle 1924. The French heavy machine gun was still the Hotchkiss M1914, a capable weapon but decidedly obsolete compared to the new automatic weapons of German infantry. A modern infantry rifle was adopted in 1936 but very few of these MAS-36 rifles had been issued to the troops by 1940. A well-tested French semiautomatic rifle, the MAS 1938–39, was ready for adoption but it never reached the production stage until after World War II as the MAS 49. As to French artillery it had, basically, not been modernized since 1918. The result of all these failings is that the French Army had to face the invading enemy in 1940, with the dated weaponry of 1918. Petain had been made, briefly, Minister of War in 1934, thus ministerially responsible for French military, aviation and the Navy as well. Yet his short period of total responsibility could not reverse 15 years of inactivity and constant cutbacks. The War Ministry was hamstrung between the wars and proved unequal to the tasks before them. French aviation entered the War in 1939 without even the prototype of a bomber aeroplane capable of reaching Berlin and coming back. French industrial efforts in fighter aircraft were dispersed among several firms (Dewoitine

Dewoitine

Constructions Aéronautiques Émile Dewoitine was a French aircraft manufacturer established by Émile Dewoitine at Toulouse in October 1920. The company's initial products were a range of metal parasol-wing fighters which were largely ignored by the French Air Force but purchased in large quantities...

, Morane-Saulnier and Marcel Bloch), each with its own model. On the naval front, France had purposely overlooked building modern aircraft carriers and focused instead on four new conventional battleships, not unlike the German Navy.

France and World War II

Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.Weygand initially fought against the Germans during the invasion of France in 1940, but then surrendered to and collaborated with the Germans as part of the Vichy France regime.-Early years:Weygand was born in Brussels...

expressed his fury at British retreats and the unfulfilled promise of British fighter airplanes. He and Pétain regarded the military situation as hopeless. Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his stances on economic liberalism and militant opposition to Germany. He was the penultimate Prime Minister of the Third Republic and vice-president of the Democratic Republican Alliance center-right...