Lynde D. McCormick

Encyclopedia

Admiral

Lynde Dupuy McCormick (August 12, 1895 – August 16, 1956) was a four-star admiral in the United States Navy

who served as vice chief of naval operations

from 1950 to 1951 and as commander in chief of the United States Atlantic Fleet from 1951 to 1954, and was the first supreme allied commander of all NATO forces in the Atlantic

.

to the former Edith Lynde Abbot and naval surgeon Albert Montgomery Dupuy McCormick, he attended St. John's Preparatory School and College

, a military school in Annapolis. In 1911, he was appointed by President William Howard Taft

to the United States Naval Academy

, where he played lacrosse

and soccer and, as a first classman, was business manager of the Academy yearbook

, the Lucky Bag

. He graduated second in a class of 183 and was commissioned ensign in the United States Navy

in June 1915.

, operating in the Caribbean Sea

and along the eastern seaboard. In November 1917, following the United States entry into World War I

, Wyoming and the rest of Battleship Division 9 (New York

, Delaware

, and Florida

) joined the British Grand Fleet as its Sixth Battle Squadron and were present at the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet

in the North Sea

after the armistice

.

In April 1919, McCormick was assigned as aide and flag lieutenant on the staff of Commander Battleship Division 4, United States Fleet

. He served aboard the battleship South Carolina

from June to September, then became aide and flag lieutenant to Commander Destroyer Squadron 4, Pacific Fleet

, aboard the squadron flagship Birmingham

. He transferred to the destroyer Buchanan

in December 1920.

In August 1921, he briefly commanded the destroyer Kennedy

In August 1921, he briefly commanded the destroyer Kennedy

, before going ashore in October as an instructor in the Department of Navigation at the Naval Academy.

He began a long association with submarine warfare

in June 1923 when he became a student at the Submarine School in New London, Connecticut

. He then served until June 1924 in the submarine S-31

, operating with Submarine Division 16 in the Pacific. After short assignments with the submarine S-37

and submarine tender Canopus

, he commanded the submarine R-10

, based at Honolulu, Hawaii

, from August 1924 until June 1926, when he was detailed to the Naval Academy as a member of the executive department. In August 1928, he began almost three years as commanding officer of the fleet submarine V-2

, operating with Submarine Division 20 in support of the United States Fleet

in maneuvers off the West Coast, the Hawaiian Islands

, and the Caribbean Sea

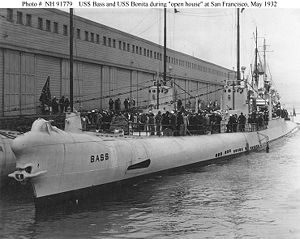

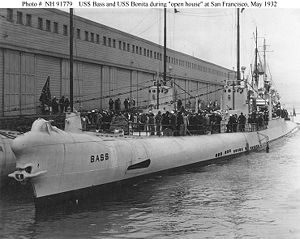

.

In May 1931, he began a three year tour at the Naval Academy as aide to the new superintendent, Rear Admiral Thomas C. Hart

. When Hart finished his tour as superintendent in June 1934, McCormick rejoined the fleet as navigator of the light cruiser Marblehead

. He took command of the fleet oiler Neches

in April 1936.

In June 1937, he was enrolled as a student in the senior course at the Naval War College

in Newport, Rhode Island

. After completing the course in May 1938, he remained at the Naval War College for an additional year as a member of the staff.

, Commander Battleships, Battle Force, aboard Snyder's flagship West Virginia

. When Snyder was elevated to command of the entire Battle Force in January 1940, McCormick followed him to the Battle Force flagship California

as operations officer on the Battle Force staff. Snyder requested early relief in January 1941 after his superior, Admiral James O. Richardson, was summarily replaced by Admiral Husband E. Kimmel

, the new Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet. Upon assuming command in February 1941, Kimmel recruited McCormick to be assistant war plans officer on the Pacific Fleet staff, in which post McCormick was serving during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

.

After the Pearl Harbor disaster, Kimmel was relieved by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who retained Kimmel's entire staff. McCormick became Nimitz' war plans officer in April 1942, serving in that capacity during the battles of the Coral Sea

, Midway

, and Guadalcanal. On June 30, 1942, McCormick was injured in a seaplane

accident while accompanying Nimitz to Alameda Naval Air Station. Despite suffering a fractured vertebra, McCormick never went on the sick list, choosing to continue on active duty while wearing a plaster cast for three months.

He was promoted to rear admiral on July 15, 1942, and, upon completing his tour on Nimitz' staff, was awarded the Legion of Merit

He was promoted to rear admiral on July 15, 1942, and, upon completing his tour on Nimitz' staff, was awarded the Legion of Merit

for "exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States as War Plans Officer on the Staff of the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, from February 1, 1941, to January 14, 1943. He was detached in February 1943 to take command of the battleship South Dakota

, operating off the Atlantic coast and later with the British Home Fleet.

From October 1943 to March 1945, he was assigned to the staff of Chief of Naval Operations

Ernest J. King as assistant chief of naval operations for logistics

plans, with additional duty as chairman of the Joint Logistics Committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

, in which capacity he accompanied King to the second Quebec

and Yalta

conferences. His logistics work earned him a Gold Star in lieu of a second Legion of Merit. The accompanying citation stated: "His mastery of the relationship between strategy and logistics and his understanding of the process of procuring and distributing critical items have been important factors in meeting the needs of area and Fleet Commanders. In a field in which the magnitude and complexity of the problems were without precedent in the history of the Navy, he has displayed conspicuous ability and brilliant leadership." He would later be quoted as saying, "I am tempted to make a slightly exaggerated statement: that logistics is all of warmaking, except shooting the guns, releasing the bombs, and firing the torpedoes."

In March 1945, he returned to the Pacific theater

as Commander of Battleship Division 3, serving as Task Group Commander for two months at the Battle of Okinawa

. He was awarded a second Gold Star for his Legion of Merit "as Commander of a Battleship Division, of a Task Group, and of a Fire Support Unit, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands

, from March through May 1945."

, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPAC/CINCPOA). McCormick was named deputy commander in chief in December, and was advanced to the temporary rank of vice admiral on February 13, 1946.

He served as Commander, Battleships-Cruisers, Atlantic Fleet, from February 1947 until November 1948. In January 1948, he led a mission to Buenos Aires

, Argentina

, aboard the heavy cruiser Albany

to establish cordial relations with the Argentine military. He reverted to his permanent rank of rear admiral upon being assigned as Commandant, Twelfth Naval District

, headquartered in San Francisco, California

, on December 8, 1948.

In 1949, Chief of Naval Operations

In 1949, Chief of Naval Operations

Louis E. Denfeld

was fired for his participation in the Revolt of the Admirals

and replaced by Admiral Forrest P. Sherman. Because the new chief of naval operations was a naval aviator

, he was expected to select a new vice chief of naval operations

, since the incumbent, Vice Admiral John D. Price, was also an aviator and it was established practice to have only one aviator in the two top staff positions. Sherman selected McCormick, whose long experience with undersea warfare was regarded as significant by naval observers because submarine and anti-submarine warfare were expected to be the Navy's principal role in the event of another war.

Upon relieving Price as vice chief, McCormick was again promoted to vice admiral, with date of rank April 3, 1950. On December 20, 1950, President Harry S. Truman

nominated McCormick for the rank of admiral, increasing the number of full admirals in the Navy to five. Truman's declaration of a national emergency

had lifted the legal limits on the number of three- and four-star officers, and McCormick was promoted to grant him equal standing with the vice chiefs of staff of the Army

and Air Force

. He was confirmed in his new rank on December 22, 1950.

Sherman died unexpectedly on July 22, 1951, while on a diplomatic trip to Europe. As acting chief of naval operations, McCormick was one of six candidates considered to succeed Sherman, along with Admirals Arthur W. Radford

, Robert B. Carney, and William M. Fechteler; and Vice Admirals Richard L. Conolly

and Donald B. Duncan

. During the selection process, McCormick took himself out of the running by loudly expressing "his desire for a fleet command." Fechteler was named chief of naval operations on August 1, 1951, and McCormick was selected to replace Fechteler as commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet. When the change was announced, press reports noted that this would be McCormick's first fleet command, and speculated that the lack of a fleet command in his record had eliminated him from consideration as Sherman's successor.

He became Commander in Chief, Atlantic Command and Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT/CINCLANTFLT) on August 15, 1951.

He became Commander in Chief, Atlantic Command and Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT/CINCLANTFLT) on August 15, 1951.

A month later, at the recommissioning ceremony for the aircraft carrier Wasp

, McCormick aroused comment by indicating that atomic bombs had been developed that were small enough to be carried by the light bombers deployed on aircraft carriers. "Eventually, I think every carrier will be equipped with atomic bombs. Since their reduction in size they have become more available for carrier use." His remarks were consistent with his previous statement while acting chief of naval operations that atomic weapons use should be treated more normally: "It is in our interest to convince the world at large that the use of atomic weapons is no less humane than the employment of an equivalent weight of so-called conventional weapons. The destruction of certain targets is essential to the successful completion of a war with the U.S.S.R. The pros and cons of the means to accomplish their destruction is purely academic."

As Fechteler's CINCLANT successor, McCormick inherited Fechteler's long-delayed appointment as the first supreme allied commander of NATO naval forces in the Atlantic. Fechteler's nomination for the post was announced on February 19, 1951, but had been stalled by British opposition led by former Prime Minister Winston Churchill

, who took offense at the concept of subordinating the Royal Navy

to an American admiral and demanded that a British admiral be appointed instead. Incumbent Prime Minister Clement Attlee

confirmed Fechteler's nomination in July, but Fechteler almost immediately vacated command of the Atlantic Fleet to become chief of naval operations, giving Churchill the opportunity to reopen the issue when he resumed the premiership in October. Churchill now argued that there was no need for a single supreme naval commander, suggesting that the Atlantic instead be divided into American and British sectors, but the United States insisted on unity of command and Churchill ultimately had to yield to American pressure, reluctantly consenting to McCormick's appointment in January 1952.

Despite his distaste for the idea of any American as supreme Atlantic commander, Churchill had no objection to McCormick personally, declaring that McCormick would "inspire the highest confidence" as that commander. To assuage British sensitivities, McCormick said that he regarded the Royal Navy

as a model for his men, that he knew London

better than New York

, and that he was equally at home in Portsmouth

, Hampshire

, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire

.

(SACLANT) on January 30, 1952, and opened SACLANT headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia

on April 10. As SACLANT, he reported directly to the NATO Standing Group, and was coequal in the NATO military hierarchy with General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower

, Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). McCormick's new command extended from the North Pole

to the Tropic of Cancer

and from the shores of North America

to those of Europe

and Africa

, with the exception of the English Channel

and British coastal waters. It was said to be the largest naval command given an individual since Christopher Columbus

had been appointed Grand Admiral of the Ocean Seas in the fifteenth century.

It was also said that McCormick was an admiral without a fleet, since he would only command allied forces during wartime. However, as commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, he exercised peacetime control over most of his actual striking power.

Soon after becoming SACLANT, McCormick traveled to every NATO capital seeking pledges of contributions from allied navies. He hoped that the European allies could begin by preparing to secure their own national waters in the event of war, but quickly found that the smaller nations viewed SACLANT as a concern primarily for the United States, Britain, and Canada, the major NATO seapowers. He complained to the NATO Standing Group that Europe treated his appointment as an excuse for complacency: "Now that SACLANT is appointed, we no longer have any naval worries, he will take care of everything for us...we need not do anything now."

In September 1952, NATO held its first major naval exercise, Operation Mainbrace, commanded jointly by McCormick and SACEUR Matthew B. Ridgway. Operation Mainbrace involved 160 allied ships of all types and tested SACLANT's ability to "provide northern flank support for a European land battle." The exercise assumed that Soviet forces had already swept through West Germany

In September 1952, NATO held its first major naval exercise, Operation Mainbrace, commanded jointly by McCormick and SACEUR Matthew B. Ridgway. Operation Mainbrace involved 160 allied ships of all types and tested SACLANT's ability to "provide northern flank support for a European land battle." The exercise assumed that Soviet forces had already swept through West Germany

and were moving into Denmark

and Norway

, and was intended in part to "reassure the Scandinavian signatories that their countries could be defended in the event of war." At the conclusion of the exercise, McCormick and Ridgway stated that Operation Mainbrace had highlighted several weaknesses in NATO for future correction. "Many questions have been asked during the exercise as to whether any great lessons were learned from it. The answer is no....A test of this sort enables us to determine our weaknesses and the corrective measures we must take. Thus far certain weaknesses have been revealed, but we regard none of them as insurmountable. Mainbrace is not an ending--it is merely a beginning."

The next year, NATO conducted a followup exercise, Operation Mariner, from September 16 to October 4, 1953. McCormick called Operation Mariner "the most complete and widespread international exercise ever held," involving 500,000 men, 1,000 planes, and 300 ships from nine navies. The exercise tested a variety of allied naval capabilities, ranging from command relationships to mine warfare

and intelligence, although "there was no strategic concept other than Blue was fighting Orange." Convoy

s crossed the Atlantic while defending against submarines and surface ships. In order "to keep us all atomic minded," both sides launched and defended against simulated nuclear attacks. McCormick viewed the exercise as a qualified success, showing that ships and aircraft of the disparate NATO navies could cooperate effectively even under adverse weather conditions, although there had been problems with communications and logistical support. After the exercise, McCormick told a dinner of the American Council on NATO

on October 29, 1953, that the Kremlin

was "well aware" of the importance of the transatlantic sea lane and was readying submarines to fight another possible Battle of the Atlantic. While Operation Mariner had demonstrated that NATO could control the Atlantic given sufficient forces, he warned, "The forces we have available at present to counter the potential underseas menace would be spread precariously thin for this task."

At the end of McCormick's tour, Chief of Naval Operations Robert B. Carney looked for a successor who would be better at standing up to the British staff at SACLANT headquarters. "I had felt a great deal of concern about the handling of the United States interests down there and in the Atlantic, vis-à-vis the British...I had felt that the United States viewpoint had been handled rather naively in some previous instances and that it was imperative that we put somebody down there who could take care of these interests." Carney selected Admiral Jerauld Wright

, who relieved McCormick on April 12, 1954.

in the rank of vice admiral on May 3, 1954.

The most significant event of his presidency was the establishment in 1956 of the naval command course, a new course for senior naval officers from up to 30 allied and friendly nations, organized and directed by Captain Richard G. Colbert

at the behest of Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh A. Burke. The Naval War College staff was initially unenthusiastic about the new course, worrying that it would detract from the regular courses. However, McCormick had already witnessed the difficulties caused by a lack of inter-allied understanding during large-scale SACLANT operations like Operation Mainbrace, and he gave Burke his full cooperation. Burke recalled, "[McCormick] was absolutely correct that this new course should not reduce the caliber of the other work the War College was doing. The president and his staff made many helpful suggestions right from the start and after it was going awhile, their enthusiasm grew, perhaps due to the quality of the foreign officers assigned."

On August 16, 1956, McCormick suffered a heart attack in his quarters around 3 a.m., and died four hours later at the Naval Hospital in Newport at the age of 61, the day before the start of classes for the 1957 course year. Students and faculty were stunned, since he had appeared to be in excellent health. Greeting the incoming students the next day, McCormick's chief of staff and acting successor, Rear Admiral Thomas H. Robbins, Jr., stated that McCormick would not have wanted his death to interfere with college routine, declaring, "The Admiral's love and devotion to this college could not be excelled. He spent his last days here devoting himself selflessly of his energies, broad experience, and wisdom to keep this college in the forefront of the military education field and in preparing officers to better serve our country in these perilous times."

admiral. A SACLANT subordinate recalled him as "a delightful, smart clean-cut gentleman." He is buried with his wife in the Naval Academy cemetery.

He married the former Lillian Addison Sprigg on October 2, 1920, and they had three sons: Navy commander Montrose Graham, who commanded a submarine during World War II and was killed in a plane crash in Australia in 1945; Navy officer Lynde Dupuy Jr.; and Marine

James Jett II, who was severely wounded at the Battle of Okinawa. His father, Rear Admiral Albert Montgomery Dupuy McCormick, was a Spanish-American War

veteran and former fleet surgeon for the Atlantic Fleet.

He was the namesake of the guided-missile destroyer Lynde McCormick

. His decorations include the Legion of Merit

with two Gold Stars; the World War I Victory Medal, Grand Fleet Clasp; the American Defense Service Medal

; the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

; the American Campaign Medal

; and the World War II Victory Medal

.

Admiral

Admiral is the rank, or part of the name of the ranks, of the highest naval officers. It is usually considered a full admiral and above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet . It is usually abbreviated to "Adm" or "ADM"...

Lynde Dupuy McCormick (August 12, 1895 – August 16, 1956) was a four-star admiral in the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

who served as vice chief of naval operations

Vice Chief of Naval Operations

The Vice Chief of Naval Operations is the second highest ranking officer in the United States Navy. In the event that the Chief of Naval Operations is absent or is unable to perform his duties, the VCNO assumes the duties and responsibilities of the CNO. The VCNO may also perform other duties...

from 1950 to 1951 and as commander in chief of the United States Atlantic Fleet from 1951 to 1954, and was the first supreme allied commander of all NATO forces in the Atlantic

Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

The Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic was one of two supreme commanders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation , the other being the Supreme Allied Commander Europe . The SACLANT led Allied Command Atlantic, based at Norfolk, Virginia...

.

Early career

Born in Annapolis, MarylandAnnapolis, Maryland

Annapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland, as well as the county seat of Anne Arundel County. It had a population of 38,394 at the 2010 census and is situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east of Washington, D.C. Annapolis is...

to the former Edith Lynde Abbot and naval surgeon Albert Montgomery Dupuy McCormick, he attended St. John's Preparatory School and College

St. John's College, U.S.

St. John's College is a liberal arts college with two U.S. campuses: one in Annapolis, Maryland and one in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Founded in 1696 as a preparatory school, King William's School, the school received a collegiate charter in 1784, making it one of the oldest institutions of higher...

, a military school in Annapolis. In 1911, he was appointed by President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States...

to the United States Naval Academy

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located in Annapolis, Maryland, United States...

, where he played lacrosse

Lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport of Native American origin played using a small rubber ball and a long-handled stick called a crosse or lacrosse stick, mainly played in the United States and Canada. It is a contact sport which requires padding. The head of the lacrosse stick is strung with loose mesh...

and soccer and, as a first classman, was business manager of the Academy yearbook

Yearbook

A yearbook, also known as an annual, is a book to record, highlight, and commemorate the past year of a school or a book published annually. Virtually all American, Australian and Canadian high schools, most colleges and many elementary and middle schools publish yearbooks...

, the Lucky Bag

Lucky bag

A Lucky Bag is the term for the United States Naval Academy 'year book' dedicated to the graduating classes. A traditional Lucky Bag has a collection of photos taken around the academy and photographs of each graduating officer along with a single paragraph describing the individual written by a...

. He graduated second in a class of 183 and was commissioned ensign in the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

in June 1915.

World War I

His first assignment was aboard the battleship WyomingUSS Wyoming (BB-32)

USS Wyoming , the lead ship of her class of battleship, was the third ship of the United States Navy named Wyoming, although it was only the second named in honor of the 44th state....

, operating in the Caribbean Sea

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean located in the tropics of the Western hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico and Central America to the west and southwest, to the north by the Greater Antilles, and to the east by the Lesser Antilles....

and along the eastern seaboard. In November 1917, following the United States entry into World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Wyoming and the rest of Battleship Division 9 (New York

USS New York (BB-34)

USS New York was a United States Navy battleship, the lead ship of her class of two . She was the fifth ship to carry her name....

, Delaware

USS Delaware (BB-28)

USS Delaware of the United States Navy was a battleship launched in 1909 and scrapped in 1924, the lead ship of the Delaware class. She was part of the U.S...

, and Florida

USS Florida (BB-30)

-External links:***...

) joined the British Grand Fleet as its Sixth Battle Squadron and were present at the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet

High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet was the battle fleet of the German Empire and saw action during World War I. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet was renamed as the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; he envisioned a force powerful enough to...

in the North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

after the armistice

Armistice with Germany (Compiègne)

The armistice between the Allies and Germany was an agreement that ended the fighting in the First World War. It was signed in a railway carriage in Compiègne Forest on 11 November 1918 and marked a victory for the Allies and a complete defeat for Germany, although not technically a surrender...

.

In April 1919, McCormick was assigned as aide and flag lieutenant on the staff of Commander Battleship Division 4, United States Fleet

United States Fleet

The United States Fleet was an organization in the United States Navy from 1922 until after World War II. The abbreviation CINCUS, pronounced "sink us", was used for Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet. This title was disposed of and officially replaced by COMINCH in December 1941 . This...

. He served aboard the battleship South Carolina

USS South Carolina (BB-26)

USS South Carolina , the lead ship of her class of dreadnought battleships, was the fourth ship of the United States Navy to be named in honor of the eighth state, and was the first American dreadnought or all-big gun battleship....

from June to September, then became aide and flag lieutenant to Commander Destroyer Squadron 4, Pacific Fleet

United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet is a Pacific Ocean theater-level component command of the United States Navy that provides naval resources under the operational control of the United States Pacific Command. Its home port is at Pearl Harbor Naval Base, Hawaii. It is commanded by Admiral Patrick M...

, aboard the squadron flagship Birmingham

USS Birmingham (CL-2)

USS Birmingham , named for the city of Birmingham, Alabama, was a laid down by the Fore River Shipbuilding Company at Quincy, Massachusetts on 14 August 1905; launched on 29 May 1907; sponsored by Mrs L...

. He transferred to the destroyer Buchanan

USS Buchanan (DD-131)

USS Buchanan , named for Franklin Buchanan, was a Wickes-class destroyer in the United States Navy.Buchanan was transferred to the United Kingdom under the Destroyers for Bases Agreement in 1940 and served as HMS Campbeltown . She was destroyed during the St...

in December 1920.

Interwar

USS Kennedy (DD-306)

The first USS Kennedy was a Clemson-class destroyer in the United States Navy following World War I. She was named for the 21st Secretary of the Navy and US Representative from Maryland, John P. Kennedy.-History:...

, before going ashore in October as an instructor in the Department of Navigation at the Naval Academy.

He began a long association with submarine warfare

Submarine warfare

Naval warfare is divided into three operational areas: surface warfare, air warfare and underwater warfare. The latter may be subdivided into submarine warfare and anti-submarine warfare as well as mine warfare and mine countermeasures...

in June 1923 when he became a student at the Submarine School in New London, Connecticut

New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States.It is located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, southeastern Connecticut....

. He then served until June 1924 in the submarine S-31

USS S-31 (SS-136)

USS S-31 was a first-group S-class submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down on 13 April 1918 by the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, California. She was launched on 28 December 1918 sponsored by Mrs. George A. Walker, and commissioned on 11 May 1922 with Lieutenant William A...

, operating with Submarine Division 16 in the Pacific. After short assignments with the submarine S-37

USS S-37 (SS-142)

USS S-37 was an S-class submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down on 12 December 1918 by the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, California. She was launched on 20 June 1919 sponsored by Miss Mildred Bulger, and commissioned on 16 July 1923 with Lieutenant Paul R...

and submarine tender Canopus

USS Canopus (AS-9)

USS Canopus was a submarine tender in the United States Navy, named for the star Canopus.Canopus was launched in 1919 by New York Shipbuilding Company, Camden, New Jersey, as the passenger liner SS Santa Leonora for W. R. Grace and Company, but taken over by the Navy upon completion in July 1919...

, he commanded the submarine R-10

USS R-10 (SS-87)

USS R-10 was an R-class coastal and harbor defense submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down on 21 March 1918 by the Fore River Shipbuilding Company in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was launched 28 June 1919 sponsored by Mrs. Philip C. Ransom, and commissioned on 20 August 1919,...

, based at Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu is the capital and the most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii. Honolulu is the southernmost major U.S. city. Although the name "Honolulu" refers to the urban area on the southeastern shore of the island of Oahu, the city and county government are consolidated as the City and...

, from August 1924 until June 1926, when he was detailed to the Naval Academy as a member of the executive department. In August 1928, he began almost three years as commanding officer of the fleet submarine V-2

USS Bass (SS-164)

USS Bass , a Barracuda-class submarine and one of the "V-boats", was the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the bass. Her keel was laid at the Portsmouth Navy Yard. She was launched as V-2 on 27 December 1924 sponsored by Mrs. Douglas E...

, operating with Submarine Division 20 in support of the United States Fleet

United States Fleet

The United States Fleet was an organization in the United States Navy from 1922 until after World War II. The abbreviation CINCUS, pronounced "sink us", was used for Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet. This title was disposed of and officially replaced by COMINCH in December 1941 . This...

in maneuvers off the West Coast, the Hawaiian Islands

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets, and undersea seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some 1,500 miles from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll...

, and the Caribbean Sea

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean located in the tropics of the Western hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico and Central America to the west and southwest, to the north by the Greater Antilles, and to the east by the Lesser Antilles....

.

In May 1931, he began a three year tour at the Naval Academy as aide to the new superintendent, Rear Admiral Thomas C. Hart

Thomas C. Hart

Thomas Charles Hart was an admiral of the United States Navy, whose service extended from the Spanish-American War through World War II. Following his retirement from the Navy, he served briefly as a United States Senator from Connecticut.-Life and career:Hart was born in Genesee County, Michigan...

. When Hart finished his tour as superintendent in June 1934, McCormick rejoined the fleet as navigator of the light cruiser Marblehead

USS Marblehead (CL-12)

USS Marblehead was an Omaha-class light cruiser of the United States Navy. She was the third Navy ship named for the town of Marblehead, Massachusetts....

. He took command of the fleet oiler Neches

USS Neches (AO-5)

USS Neches was laid down on 8 June 1919 by the Boston Navy Yard in Boston, Massachusetts; launched on 2 June 1920, sponsored by Miss Helen Griffin, daughter of Rear Admiral Robert Griffin; and commissioned on 25 October 1920, with Commander H. T. Meriwether, USNRF, in command.Originally classified...

in April 1936.

In June 1937, he was enrolled as a student in the senior course at the Naval War College

Naval War College

The Naval War College is an education and research institution of the United States Navy that specializes in developing ideas for naval warfare and passing them along to officers of the Navy. The college is located on the grounds of Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island...

in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States, about south of Providence. Known as a New England summer resort and for the famous Newport Mansions, it is the home of Salve Regina University and Naval Station Newport which houses the United States Naval War...

. After completing the course in May 1938, he remained at the Naval War College for an additional year as a member of the staff.

World War II

In June 1939, he became operations officer on the staff of Vice Admiral Charles P. SnyderCharles P. Snyder (admiral)

Charles Philip Snyder was a four-star admiral in the United States Navy who served as the U.S. Navy's first Naval Inspector General during World War II.-Early career:...

, Commander Battleships, Battle Force, aboard Snyder's flagship West Virginia

USS West Virginia (BB-48)

USS West Virginia , a , was the second ship of the United States Navy named in honor of the 35th state.Her keel was laid down on 12 April 1920 by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of Newport News, Virginia. She was launched on 17 November 1921 sponsored by Miss Alice Wright Mann,...

. When Snyder was elevated to command of the entire Battle Force in January 1940, McCormick followed him to the Battle Force flagship California

USS California (BB-44)

USS California , a Tennessee-class battleship, was the fifth ship of the United States Navy named in honor of the 31st state. Beginning as the flagship of the Pacific Fleet, she served in the Pacific her entire career. She was sunk in the attack on Pearl Harbor at her moorings in Battleship Row,...

as operations officer on the Battle Force staff. Snyder requested early relief in January 1941 after his superior, Admiral James O. Richardson, was summarily replaced by Admiral Husband E. Kimmel

Husband E. Kimmel

Husband Edward Kimmel was a four-star admiral in the United States Navy. He served as Commander-in-chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Because of the attack, he was removed from office and was reduced to his permanent two-star rank of rear admiral...

, the new Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet. Upon assuming command in February 1941, Kimmel recruited McCormick to be assistant war plans officer on the Pacific Fleet staff, in which post McCormick was serving during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

.

After the Pearl Harbor disaster, Kimmel was relieved by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who retained Kimmel's entire staff. McCormick became Nimitz' war plans officer in April 1942, serving in that capacity during the battles of the Coral Sea

Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, fought from 4–8 May 1942, was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II between the Imperial Japanese Navy and Allied naval and air forces from the United States and Australia. The battle was the first fleet action in which aircraft carriers engaged...

, Midway

Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway is widely regarded as the most important naval battle of the Pacific Campaign of World War II. Between 4 and 7 June 1942, approximately one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea and six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy decisively defeated...

, and Guadalcanal. On June 30, 1942, McCormick was injured in a seaplane

Seaplane

A seaplane is a fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing on water. Seaplanes that can also take off and land on airfields are a subclass called amphibian aircraft...

accident while accompanying Nimitz to Alameda Naval Air Station. Despite suffering a fractured vertebra, McCormick never went on the sick list, choosing to continue on active duty while wearing a plaster cast for three months.

Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit is a military decoration of the United States armed forces that is awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements...

for "exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States as War Plans Officer on the Staff of the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, from February 1, 1941, to January 14, 1943. He was detached in February 1943 to take command of the battleship South Dakota

USS South Dakota (BB-57)

USS South Dakota was a battleship in the United States Navy from 1942 until 1947. The lead ship of her class, South Dakota was the third ship of the US Navy to be named in honor of the 40th state. During World War II, she first served in a fifteen-month tour in the Pacific theater, where she saw...

, operating off the Atlantic coast and later with the British Home Fleet.

From October 1943 to March 1945, he was assigned to the staff of Chief of Naval Operations

Chief of Naval Operations

The Chief of Naval Operations is a statutory office held by a four-star admiral in the United States Navy, and is the most senior uniformed officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Navy. The office is a military adviser and deputy to the Secretary of the Navy...

Ernest J. King as assistant chief of naval operations for logistics

Military logistics

Military logistics is the discipline of planning and carrying out the movement and maintenance of military forces. In its most comprehensive sense, it is those aspects or military operations that deal with:...

plans, with additional duty as chairman of the Joint Logistics Committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff is a body of senior uniformed leaders in the United States Department of Defense who advise the Secretary of Defense, the Homeland Security Council, the National Security Council and the President on military matters...

, in which capacity he accompanied King to the second Quebec

Second Quebec Conference

The Second Quebec Conference was a high level military conference held during World War II between the British, Canadian and American governments. The conference was held in Quebec City, September 12, 1944 - September 16, 1944, and was the second conference to be held in Quebec, after "QUADRANT"...

and Yalta

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

conferences. His logistics work earned him a Gold Star in lieu of a second Legion of Merit. The accompanying citation stated: "His mastery of the relationship between strategy and logistics and his understanding of the process of procuring and distributing critical items have been important factors in meeting the needs of area and Fleet Commanders. In a field in which the magnitude and complexity of the problems were without precedent in the history of the Navy, he has displayed conspicuous ability and brilliant leadership." He would later be quoted as saying, "I am tempted to make a slightly exaggerated statement: that logistics is all of warmaking, except shooting the guns, releasing the bombs, and firing the torpedoes."

In March 1945, he returned to the Pacific theater

Pacific Ocean theater of World War II

The Pacific Ocean theatre was one of four major naval theatres of war of World War II, which pitted the forces of Japan against those of the United States, the British Commonwealth, the Netherlands and France....

as Commander of Battleship Division 3, serving as Task Group Commander for two months at the Battle of Okinawa

Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War of World War II. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June 1945...

. He was awarded a second Gold Star for his Legion of Merit "as Commander of a Battleship Division, of a Task Group, and of a Fire Support Unit, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands

Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the , is a chain of islands in the western Pacific, on the eastern limit of the East China Sea and to the southwest of the island of Kyushu in Japan. From about 1829 until the mid 20th century, they were alternately called Luchu, Loochoo, or Lewchew, akin to the Mandarin...

, from March through May 1945."

Postwar

After the war, he participated in the initial occupation of Japan until November 1945, when he was assigned as chief of staff and aide to Admiral John H. TowersJohn H. Towers

John Henry Towers was a United States Navy admiral and pioneer Naval aviator. He made important contributions to the technical and organizational development of Naval Aviation from its very beginnings, eventually serving as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics...

, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPAC/CINCPOA). McCormick was named deputy commander in chief in December, and was advanced to the temporary rank of vice admiral on February 13, 1946.

He served as Commander, Battleships-Cruisers, Atlantic Fleet, from February 1947 until November 1948. In January 1948, he led a mission to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires is the capital and largest city of Argentina, and the second-largest metropolitan area in South America, after São Paulo. It is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the southeastern coast of the South American continent...

, Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

, aboard the heavy cruiser Albany

USS Albany (CA-123)

USS Albany was a United States Navy Oregon City-class heavy cruiser, later converted to the guided missile cruiser CG-10. The converted cruiser was the lead ship the new Albany guided missile cruiser class...

to establish cordial relations with the Argentine military. He reverted to his permanent rank of rear admiral upon being assigned as Commandant, Twelfth Naval District

United States Naval Districts

The naval district is a military and administrative command ashore, established for the purpose of decentralizing the U.S. Navy Department's functions with respect to the control of the coastwise sea communications and the shore activities outside the department proper, and for the further purpose...

, headquartered in San Francisco, California

San Francisco, California

San Francisco , officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the financial, cultural, and transportation center of the San Francisco Bay Area, a region of 7.15 million people which includes San Jose and Oakland...

, on December 8, 1948.

Vice Chief of Naval Operations

Chief of Naval Operations

The Chief of Naval Operations is a statutory office held by a four-star admiral in the United States Navy, and is the most senior uniformed officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Navy. The office is a military adviser and deputy to the Secretary of the Navy...

Louis E. Denfeld

Louis E. Denfeld

Louis Emil Denfeld , was Chief of Naval Operations of the United States Navy from 15 December 1947 to 1 November 1949. He also held several significant surface commands during World War II, and after the war commanded the U.S...

was fired for his participation in the Revolt of the Admirals

Revolt of the Admirals

The Revolt of the Admirals is a name given to an episode that took place in the late 1940s in which several United States Navy admirals and high-ranking civilian officials publicly disagreed with the President and the Secretary of Defense's strategy and plans for the military forces in the early...

and replaced by Admiral Forrest P. Sherman. Because the new chief of naval operations was a naval aviator

United States Naval Aviator

A United States Naval Aviator is a qualified pilot in the United States Navy, Marine Corps or Coast Guard.-Naming Conventions:Most Naval Aviators are Unrestricted Line Officers; however, a small number of Limited Duty Officers and Chief Warrant Officers are also trained as Naval Aviators.Until 1981...

, he was expected to select a new vice chief of naval operations

Vice Chief of Naval Operations

The Vice Chief of Naval Operations is the second highest ranking officer in the United States Navy. In the event that the Chief of Naval Operations is absent or is unable to perform his duties, the VCNO assumes the duties and responsibilities of the CNO. The VCNO may also perform other duties...

, since the incumbent, Vice Admiral John D. Price, was also an aviator and it was established practice to have only one aviator in the two top staff positions. Sherman selected McCormick, whose long experience with undersea warfare was regarded as significant by naval observers because submarine and anti-submarine warfare were expected to be the Navy's principal role in the event of another war.

Upon relieving Price as vice chief, McCormick was again promoted to vice admiral, with date of rank April 3, 1950. On December 20, 1950, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

nominated McCormick for the rank of admiral, increasing the number of full admirals in the Navy to five. Truman's declaration of a national emergency

State of emergency

A state of emergency is a governmental declaration that may suspend some normal functions of the executive, legislative and judicial powers, alert citizens to change their normal behaviours, or order government agencies to implement emergency preparedness plans. It can also be used as a rationale...

had lifted the legal limits on the number of three- and four-star officers, and McCormick was promoted to grant him equal standing with the vice chiefs of staff of the Army

Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army is the principal advisor and assistant to the Army Chief of Staff, the second-highest ranking officer in the US Army. He handles the day to day administration of the Army bureaucracy, freeing the Chief of Staff to attend to the interservice...

and Air Force

Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force

The Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force is the second highest ranking military officer in the United States Air Force. In the event that the Chief of Staff of the Air Force is absent or is unable to perform his duties, the VCSAF assumes the duties and responsibilities of the CSAF...

. He was confirmed in his new rank on December 22, 1950.

Sherman died unexpectedly on July 22, 1951, while on a diplomatic trip to Europe. As acting chief of naval operations, McCormick was one of six candidates considered to succeed Sherman, along with Admirals Arthur W. Radford

Arthur W. Radford

Arthur William Radford was a United States Navy Admiral, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Command and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.Arthur Radford was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1896...

, Robert B. Carney, and William M. Fechteler; and Vice Admirals Richard L. Conolly

Richard L. Conolly

Richard Lansing Conolly was a United States Navy Admiral, who served during World War I and World War II.-Biography:...

and Donald B. Duncan

Donald B. Duncan

Donald Bradley Duncan was an admiral in the United States Navy, who played an important role in aircraft-carrier operations during World War II....

. During the selection process, McCormick took himself out of the running by loudly expressing "his desire for a fleet command." Fechteler was named chief of naval operations on August 1, 1951, and McCormick was selected to replace Fechteler as commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet. When the change was announced, press reports noted that this would be McCormick's first fleet command, and speculated that the lack of a fleet command in his record had eliminated him from consideration as Sherman's successor.

Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet

A month later, at the recommissioning ceremony for the aircraft carrier Wasp

USS Wasp (CV-18)

USS Wasp was one of 24 s built during World War II for the United States Navy. The ship, the ninth US Navy ship to bear the name, was originally named Oriskany, but was renamed while under construction in honor of the previous , which was sunk 15 September 1942...

, McCormick aroused comment by indicating that atomic bombs had been developed that were small enough to be carried by the light bombers deployed on aircraft carriers. "Eventually, I think every carrier will be equipped with atomic bombs. Since their reduction in size they have become more available for carrier use." His remarks were consistent with his previous statement while acting chief of naval operations that atomic weapons use should be treated more normally: "It is in our interest to convince the world at large that the use of atomic weapons is no less humane than the employment of an equivalent weight of so-called conventional weapons. The destruction of certain targets is essential to the successful completion of a war with the U.S.S.R. The pros and cons of the means to accomplish their destruction is purely academic."

As Fechteler's CINCLANT successor, McCormick inherited Fechteler's long-delayed appointment as the first supreme allied commander of NATO naval forces in the Atlantic. Fechteler's nomination for the post was announced on February 19, 1951, but had been stalled by British opposition led by former Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, who took offense at the concept of subordinating the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

to an American admiral and demanded that a British admiral be appointed instead. Incumbent Prime Minister Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

confirmed Fechteler's nomination in July, but Fechteler almost immediately vacated command of the Atlantic Fleet to become chief of naval operations, giving Churchill the opportunity to reopen the issue when he resumed the premiership in October. Churchill now argued that there was no need for a single supreme naval commander, suggesting that the Atlantic instead be divided into American and British sectors, but the United States insisted on unity of command and Churchill ultimately had to yield to American pressure, reluctantly consenting to McCormick's appointment in January 1952.

Despite his distaste for the idea of any American as supreme Atlantic commander, Churchill had no objection to McCormick personally, declaring that McCormick would "inspire the highest confidence" as that commander. To assuage British sensitivities, McCormick said that he regarded the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

as a model for his men, that he knew London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

better than New York

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, and that he was equally at home in Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

, Hampshire

Hampshire

Hampshire is a county on the southern coast of England in the United Kingdom. The county town of Hampshire is Winchester, a historic cathedral city that was once the capital of England. Hampshire is notable for housing the original birthplaces of the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force...

, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire in the United States. It is the largest city but only the fourth-largest community in the county, with a population of 21,233 at the 2010 census...

.

Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

McCormick was appointed Supreme Allied Commander AtlanticSupreme Allied Commander Atlantic

The Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic was one of two supreme commanders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation , the other being the Supreme Allied Commander Europe . The SACLANT led Allied Command Atlantic, based at Norfolk, Virginia...

(SACLANT) on January 30, 1952, and opened SACLANT headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

on April 10. As SACLANT, he reported directly to the NATO Standing Group, and was coequal in the NATO military hierarchy with General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

, Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). McCormick's new command extended from the North Pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

to the Tropic of Cancer

Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, also referred to as the Northern tropic, is the circle of latitude on the Earth that marks the most northerly position at which the Sun may appear directly overhead at its zenith...

and from the shores of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

to those of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, with the exception of the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

and British coastal waters. It was said to be the largest naval command given an individual since Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

had been appointed Grand Admiral of the Ocean Seas in the fifteenth century.

It was also said that McCormick was an admiral without a fleet, since he would only command allied forces during wartime. However, as commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, he exercised peacetime control over most of his actual striking power.

Soon after becoming SACLANT, McCormick traveled to every NATO capital seeking pledges of contributions from allied navies. He hoped that the European allies could begin by preparing to secure their own national waters in the event of war, but quickly found that the smaller nations viewed SACLANT as a concern primarily for the United States, Britain, and Canada, the major NATO seapowers. He complained to the NATO Standing Group that Europe treated his appointment as an excuse for complacency: "Now that SACLANT is appointed, we no longer have any naval worries, he will take care of everything for us...we need not do anything now."

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

and were moving into Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

and Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

, and was intended in part to "reassure the Scandinavian signatories that their countries could be defended in the event of war." At the conclusion of the exercise, McCormick and Ridgway stated that Operation Mainbrace had highlighted several weaknesses in NATO for future correction. "Many questions have been asked during the exercise as to whether any great lessons were learned from it. The answer is no....A test of this sort enables us to determine our weaknesses and the corrective measures we must take. Thus far certain weaknesses have been revealed, but we regard none of them as insurmountable. Mainbrace is not an ending--it is merely a beginning."

The next year, NATO conducted a followup exercise, Operation Mariner, from September 16 to October 4, 1953. McCormick called Operation Mariner "the most complete and widespread international exercise ever held," involving 500,000 men, 1,000 planes, and 300 ships from nine navies. The exercise tested a variety of allied naval capabilities, ranging from command relationships to mine warfare

Mine warfare

Mine warfare refers to the use of different types of explosive devices:*Land mine, a weight-triggered explosive device intended to maim or kill people or to destroy vehicles...

and intelligence, although "there was no strategic concept other than Blue was fighting Orange." Convoy

Convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support, though it may also be used in a non-military sense, for example when driving through remote areas.-Age of Sail:Naval...

s crossed the Atlantic while defending against submarines and surface ships. In order "to keep us all atomic minded," both sides launched and defended against simulated nuclear attacks. McCormick viewed the exercise as a qualified success, showing that ships and aircraft of the disparate NATO navies could cooperate effectively even under adverse weather conditions, although there had been problems with communications and logistical support. After the exercise, McCormick told a dinner of the American Council on NATO

Atlantic Council

The Atlantic Council is a Washington, D.C. think tank and public policy group whose mission is to "promote constructive U.S. leadership and engagement in international affairs based on the central role of the Atlantic community in meeting the international challenges of the 21st...

on October 29, 1953, that the Kremlin

Kremlin

A kremlin , same root as in kremen is a major fortified central complex found in historic Russian cities. This word is often used to refer to the best-known one, the Moscow Kremlin, or metonymically to the government that is based there...

was "well aware" of the importance of the transatlantic sea lane and was readying submarines to fight another possible Battle of the Atlantic. While Operation Mariner had demonstrated that NATO could control the Atlantic given sufficient forces, he warned, "The forces we have available at present to counter the potential underseas menace would be spread precariously thin for this task."

At the end of McCormick's tour, Chief of Naval Operations Robert B. Carney looked for a successor who would be better at standing up to the British staff at SACLANT headquarters. "I had felt a great deal of concern about the handling of the United States interests down there and in the Atlantic, vis-à-vis the British...I had felt that the United States viewpoint had been handled rather naively in some previous instances and that it was imperative that we put somebody down there who could take care of these interests." Carney selected Admiral Jerauld Wright

Jerauld Wright

Admiral Jerauld Wright, USN, served as the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Command and the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S...

, who relieved McCormick on April 12, 1954.

President, Naval War College

After stepping down as SACLANT, McCormick was appointed President of the Naval War CollegePresident of the Naval War College

The President of the Naval War College is a flag officer in the United States Navy. The President's House is his official residence.Since the Korean War, all presidents of the Naval War College have been vice admirals or rear admirals.-Presidents:...

in the rank of vice admiral on May 3, 1954.

The most significant event of his presidency was the establishment in 1956 of the naval command course, a new course for senior naval officers from up to 30 allied and friendly nations, organized and directed by Captain Richard G. Colbert

Richard G. Colbert

Richard Gary Colbert was a four-star admiral in the United States Navy who served as President of the Naval War College from 1968 to 1971, and as commander in chief of all NATO forces in southern Europe from 1972 to 1973. He was nicknamed "Mr. International Navy" as one of the very few senior...

at the behest of Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh A. Burke. The Naval War College staff was initially unenthusiastic about the new course, worrying that it would detract from the regular courses. However, McCormick had already witnessed the difficulties caused by a lack of inter-allied understanding during large-scale SACLANT operations like Operation Mainbrace, and he gave Burke his full cooperation. Burke recalled, "[McCormick] was absolutely correct that this new course should not reduce the caliber of the other work the War College was doing. The president and his staff made many helpful suggestions right from the start and after it was going awhile, their enthusiasm grew, perhaps due to the quality of the foreign officers assigned."

On August 16, 1956, McCormick suffered a heart attack in his quarters around 3 a.m., and died four hours later at the Naval Hospital in Newport at the age of 61, the day before the start of classes for the 1957 course year. Students and faculty were stunned, since he had appeared to be in excellent health. Greeting the incoming students the next day, McCormick's chief of staff and acting successor, Rear Admiral Thomas H. Robbins, Jr., stated that McCormick would not have wanted his death to interfere with college routine, declaring, "The Admiral's love and devotion to this college could not be excelled. He spent his last days here devoting himself selflessly of his energies, broad experience, and wisdom to keep this college in the forefront of the military education field and in preparing officers to better serve our country in these perilous times."

Personal life

The scion of an old Navy family, McCormick was remembered as a man of extreme reserve of manner who was viewed by associates as the precisely correct quarterdeckDeck (ship)

A deck is a permanent covering over a compartment or a hull of a ship. On a boat or ship, the primary deck is the horizontal structure which forms the 'roof' for the hull, which both strengthens the hull and serves as the primary working surface...

admiral. A SACLANT subordinate recalled him as "a delightful, smart clean-cut gentleman." He is buried with his wife in the Naval Academy cemetery.

He married the former Lillian Addison Sprigg on October 2, 1920, and they had three sons: Navy commander Montrose Graham, who commanded a submarine during World War II and was killed in a plane crash in Australia in 1945; Navy officer Lynde Dupuy Jr.; and Marine

United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps is a branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for providing power projection from the sea, using the mobility of the United States Navy to deliver combined-arms task forces rapidly. It is one of seven uniformed services of the United States...

James Jett II, who was severely wounded at the Battle of Okinawa. His father, Rear Admiral Albert Montgomery Dupuy McCormick, was a Spanish-American War

Spanish-American War

The Spanish–American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States, effectively the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence...

veteran and former fleet surgeon for the Atlantic Fleet.

He was the namesake of the guided-missile destroyer Lynde McCormick

USS Lynde McCormick (DDG-8)

USS Lynde McCormick was a Charles F. Adams-class destroyer in the United States Navy.Lynde McCormick was laid down 4 April 1958 by Defoe Shipbuilding Company, Bay City, Michigan; launched 28 July 1959; sponsored by Mrs. Lillian McCormick, wife of Admiral McCormick; and commissioned at Boston 3...

. His decorations include the Legion of Merit

Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit is a military decoration of the United States armed forces that is awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements...

with two Gold Stars; the World War I Victory Medal, Grand Fleet Clasp; the American Defense Service Medal

American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal is a decoration of the United States military, recognizing service before America’s entry into the Second World War but during the initial years of the European conflict.-Criteria:...

; the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

The European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal is a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt...

; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal is a service decoration of the Second World War which was awarded to any member of the United States military who served in the Pacific Theater from 1941 to 1945 and was created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was...

; the American Campaign Medal

American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal was a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt...

; and the World War II Victory Medal

World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a decoration of the United States military which was created by an act of Congress in July 1945. The decoration commemorates military service during World War II and is awarded to any member of the United States military, including members of the armed forces of...

.

Legion of MeritLegion of MeritThe Legion of Merit is a military decoration of the United States armed forces that is awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements...

Legion of MeritLegion of MeritThe Legion of Merit is a military decoration of the United States armed forces that is awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements...

with two Gold Stars World War I Victory Medal with Grand Fleet Clasp

World War I Victory Medal with Grand Fleet Clasp American Defense Service MedalAmerican Defense Service MedalThe American Defense Service Medal is a decoration of the United States military, recognizing service before America’s entry into the Second World War but during the initial years of the European conflict.-Criteria:...

American Defense Service MedalAmerican Defense Service MedalThe American Defense Service Medal is a decoration of the United States military, recognizing service before America’s entry into the Second World War but during the initial years of the European conflict.-Criteria:... American Campaign MedalAmerican Campaign MedalThe American Campaign Medal was a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt...

American Campaign MedalAmerican Campaign MedalThe American Campaign Medal was a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt... European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign MedalEuropean-African-Middle Eastern Campaign MedalThe European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal is a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt...

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign MedalEuropean-African-Middle Eastern Campaign MedalThe European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal is a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt... Asiatic-Pacific Campaign MedalAsiatic-Pacific Campaign MedalThe Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal is a service decoration of the Second World War which was awarded to any member of the United States military who served in the Pacific Theater from 1941 to 1945 and was created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was...

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign MedalAsiatic-Pacific Campaign MedalThe Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal is a service decoration of the Second World War which was awarded to any member of the United States military who served in the Pacific Theater from 1941 to 1945 and was created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was... World War II Victory Medal

World War II Victory Medal