Gerard O'Neill

Encyclopedia

Gerard Kitchen O'Neill (February 6, 1927 – April 27, 1992) was an American

physicist

and space activist. As a faculty member of Princeton University

, he invented a device called the particle storage ring

for high-energy physics experiments. Later, he invented a magnetic launcher called the mass driver

. In the 1970s, he developed a plan to build human settlements in outer space, including a space habitat

design known as the O'Neill cylinder. He founded the Space Studies Institute

, an organization devoted to funding research into space manufacturing

and colonization

.

O'Neill began researching high-energy particle physics

at Princeton

in 1954 after he received his doctorate from Cornell University

. Two years later, he published his theory for a particle storage ring. This invention allowed particle physics experiments

at much higher energies than had previously been possible. In 1965 at Stanford University

, he performed the first colliding beam physics experiment.

While teaching physics at Princeton, O'Neill became interested in the possibility that humans could live in outer space. He researched and proposed a futuristic idea for human settlement in space, the O'Neill cylinder, in "The Colonization of Space", his first paper on the subject. He held a conference on space manufacturing

at Princeton in 1975. Many who became post-Apollo-era space activists attended. O'Neill built his first mass driver prototype

with professor Henry Kolm

in 1976. He considered mass drivers critical for extracting the mineral resources of the Moon

and asteroid

s. His award-winning book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

inspired a generation of space exploration advocates. He died of leukemia

in 1992.

on February 6, 1927 to Edward Gerard O'Neill, a lawyer, and Dorothy Lewis O'Neill (née Kitchen). He had no siblings. His family moved to Speculator, New York

when his father temporarily retired for health reasons. For high school, O'Neill attended Newburgh Free Academy

in Newburgh, New York. While he was a student there he edited the school newspaper and took a job as a news broadcaster at a local radio station. He graduated in 1944, during World War II

, and enlisted in the United States Navy

on his 17th birthday. The Navy trained him as a radar technician, which sparked his interest in science.

After he was honorably discharged in 1946, O'Neill studied for an undergraduate degree in physics and mathematics at Swarthmore College

. As a child he had discussed the possibilities of humans in space with his parents, and in college he enjoyed working on rocket equations. However, he did not see space science as an option for a career path in physics, choosing instead to pursue high-energy physics. In 1950 he graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors. O'Neill performed his graduate studies at Cornell University

with the help of an Atomic Energy Commission

fellowship, and was awarded a Ph.D. in physics in 1954.

O'Neill married Sylvia Turlington, also a Swarthmore graduate, in June 1950. They had a son, Roger, and two daughters, Janet and Eleanor, before their marriage ended in divorce in 1966.

One of O'Neill's favorite activities was flying. He held instrument certifications in both powered and sailplane

flight and held the FAI

Diamond Badge, a gliding award. During his first cross-country glider flight in April 1973, he was assisted on the ground by Renate "Tasha" Steffen. He had met Tasha, who was 21 years younger than him, previously through the YMCA

International Club. They were married the day after his flight. They had a son, Edward O'Neill.

. There he started his research into high-energy particle physics

. In 1956, his second year of teaching, his two-page letter titled "Storage-Ring Synchrotron: Device for High-Energy Physics Research" was published in Physical Review. It theorized that the particles produced by a particle accelerator

could be stored for a few seconds in a storage ring

. The stored particles could then be directed to collide with another particle beam. This would increase the energy of the particle collision over the previous method, which directed the beam at a fixed target. His ideas were not immediately accepted by the physics community.

O'Neill became an assistant professor at Princeton in 1956, and was promoted to associate professor in 1959. He visited Stanford University in 1957 to meet with Professor Wolfgang K. H. Panofsky

. This resulted in a collaboration between Princeton and Stanford to build the Colliding Beam Experiment (CBX). With a US$800,000 grant from the Office of Naval Research

, construction on the first particle storage rings began in 1958 at the Stanford High-Energy Physics Laboratory. He figured out how to capture the particles and, by pumping the air out to produce a vacuum

, store them long enough to experiment on them. CBX stored its first beam on March 28, 1962. O'Neill became a full professor of physics in 1965.

In collaboration with Burton Richter

In collaboration with Burton Richter

, O'Neill performed the first colliding beam physics experiment in 1965. In this experiment, particle beams from the Stanford Linear Accelerator were collected in his storage rings and then directed to collide at an energy of 600 MeV. At the time, this was the highest energy involved in a particle collision. The results proved that the charge of an electron is contained in a volume less than 100 attometers across. O'Neill considered his device to be capable of only seconds of storage, but, by creating an even stronger vacuum, others were able to increase this to hours. In 1979, he, with physicist David C. Cheng, wrote the graduate-level textbook Elementary Particle Physics: An Introduction. He retired from teaching in 1985, but remained associated with Princeton as professor emeritus until his death.

O'Neill saw great potential in the United States space program, especially the Apollo missions. He applied to the Astronaut Corps after NASA opened it up to civilian scientists in 1966. Later, when asked why he wanted to go on the Moon missions, he said, "to be alive now and not take part in it seemed terribly myopic". He was put through NASA's rigorous mental and physical examinations. During this time he met Brian O'Leary

O'Neill saw great potential in the United States space program, especially the Apollo missions. He applied to the Astronaut Corps after NASA opened it up to civilian scientists in 1966. Later, when asked why he wanted to go on the Moon missions, he said, "to be alive now and not take part in it seemed terribly myopic". He was put through NASA's rigorous mental and physical examinations. During this time he met Brian O'Leary

, also a scientist-astronaut candidate, who became his good friend. O'Leary was selected for Astronaut Group 6

but O'Neill was not.

O'Neill became interested in the idea of space colonization in 1969 while he was teaching freshman physics at Princeton University. His students were growing cynical about the benefits of science to humanity because of the controversy surrounding the Vietnam War

. To give them something relevant to study, he began using examples from the Apollo program as applications of elementary physics. O'Neill posed the question during an extra seminar he gave to a few of his students: "Is the surface of a planet really the right place for an expanding technological civilization?" His students' research convinced him that the answer was no.

O'Neill was inspired by the papers written by his students. He began to work out the details of a program to build self-supporting space habitats in free space. Among the details was how to provide the inhabitants of a space colony with an Earth-like environment. His students had designed giant pressurized structures, spun up to approximate Earth gravity by centrifugal force

O'Neill was inspired by the papers written by his students. He began to work out the details of a program to build self-supporting space habitats in free space. Among the details was how to provide the inhabitants of a space colony with an Earth-like environment. His students had designed giant pressurized structures, spun up to approximate Earth gravity by centrifugal force

. With the population of the colony living on the inner surface of a sphere or cylinder, these structures resembled "inside-out planets". He found that pairing counter-rotating cylinders would eliminate the need to spin them using rockets. This configuration has since been known as the O'Neill cylinder.

, Princeton, and other schools. Many students and staff attending the lectures became enthusiastic about the possibility of living in space. Another outlet for O'Neill to explore his ideas was with his children; on walks in the forest they speculated about life in a space colony. His paper finally appeared in the September 1974 issue of Physics Today

. In it, he argued that building space colonies would solve several important problems:

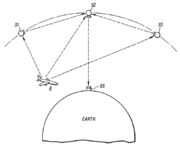

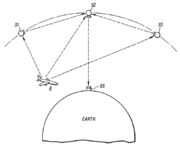

He even explored the possibilities of flying gliders inside a space colony, finding that the enormous volume could support atmospheric thermals. He calculated that humanity could expand on this man-made frontier to 20,000 times its population. The initial colonies would be built at the Earth-Moon and Lagrange points

He even explored the possibilities of flying gliders inside a space colony, finding that the enormous volume could support atmospheric thermals. He calculated that humanity could expand on this man-made frontier to 20,000 times its population. The initial colonies would be built at the Earth-Moon and Lagrange points

. and are stable points in the Solar System

where a spacecraft can maintain its position without expending energy. The paper was well received, but many who would begin work on the project had already been introduced to his ideas before it was even published. The paper received a few critical responses. Some questioned the practicality of lifting tens of thousands of people into orbit and his estimates for the production output of initial colonies.

While he was waiting for his paper to be published, O'Neill organized a small two-day conference in May 1974 at Princeton to discuss the possibility of colonizing outer space. The conference, titled First Conference on Space Colonization, was funded by Stewart Brand's Point Foundation

and Princeton University. Among those who attended were Eric Drexler (at the time a freshman at MIT

), scientist-astronaut Joe Allen (from Astronaut Group 6), Freeman Dyson

, and science reporter Walter Sullivan

. Representatives from NASA also attended and brought estimates of launch costs expected on the planned Space Shuttle

. O'Neill thought of the attendees as "a band of daring radicals". Sullivan's article on the conference was published on the front page of The New York Times

on May 13, 1974. As media coverage grew, O'Neill was inundated with letters from people who were excited about living in space. To stay in touch with them, O'Neill began keeping a mailing list and started sending out updates on his progress. A few months later he heard Peter Glaser

speak about solar power satellites at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

. O'Neill realized that, by building these satellites, his space colonies could quickly recover the cost of their construction. According to O'Neill, "the profound difference between this and everything else done in space is the potential of generating large amounts of new wealth".

and Carolyn Henson

from Tucson, Arizona

.

After the conference Carolyn Henson arranged a meeting between O'Neill and Arizona Congressman Morris Udall

. Udall wrote a letter of support, which he asked the Hensons to publicize, for O'Neill's work. The Hensons included his letter in the first issue of the L-5 Society

newsletter, sent to everyone on O'Neill's mailing list and those who had signed up at the conference.

In June 1975, O'Neill led a ten-week study of permanent space habitats at NASA Ames. During the study he was called away to testify on July 23 to the House

In June 1975, O'Neill led a ten-week study of permanent space habitats at NASA Ames. During the study he was called away to testify on July 23 to the House

Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications. On January 19, 1976, he also appeared before the Senate

Subcommittee on Aerospace Technology and National Needs. In a presentation titled Solar Power from Satellites, he laid out his case for an Apollo-style program for building power plants in space. He returned to Ames in June 1976 and 1977 to lead studies on space manufacturing. In these studies, NASA developed detailed plans to establish bases on the Moon where space-suited workers would mine the mineral resources needed to build space colonies and solar power satellites.

, a non-profit organization, at Princeton University. SSI received initial funding of almost $100,000 from private donors, and in early 1978 began to support basic research into technologies needed for space manufacturing and settlement.

One of SSI's

One of SSI's

first grants funded the development of the mass driver

, a device first proposed by O'Neill in 1974. Mass drivers are based on the coilgun

design, adapted to accelerate a non-magnetic object. One application O'Neill proposed for mass drivers was to throw baseball-sized chunks of ore mined from the surface of the Moon into space. Once in space, the ore could be used as raw material for building space colonies and solar power satellites. He took a sabbatical from Princeton to work on mass drivers at MIT. There he served as the Hunsaker Visiting Professor of Aerospace

during the 1976–77 academic year. At MIT, he, Henry H. Kolm

, and a group of student volunteers built their first mass driver prototype

. The eight-foot (2.5 m) long prototype could apply 33 g

(320 m/s2) of acceleration to an object inserted into it. With financial assistance from SSI, later prototypes improved this to 1,800 g (18,000 m/s2), enough acceleration that a mass driver only 520 feet (160 m) long could launch material off the surface of the Moon.

. He and his wife were flying between meetings, interviews, and hearings. On October 9, the CBS

program 60 Minutes

ran a segment about space colonies. Later they aired responses from the viewers, which included one from Senator William Proxmire

, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee responsible for NASA's budget. His response was, "it's the best argument yet for chopping NASA's funding to the bone .... I say not a penny for this nutty fantasy". He successfully eliminated spending on space colonization research from the budget. In 1978, Paul Werbos

wrote for the L-5 newsletter, "no one expects Congress to commit us to O'Neill's concept of large-scale space habitats; people in NASA are almost paranoid about the public relations aspects of the idea". When it became clear that a government funded colonization effort was politically impossible, popular support for O'Neill's ideas started to evaporate.

Other pressures on O'Neill's colonization plan were the high cost of access to Earth orbit and the declining cost of energy. Building solar power stations in space was economically attractive when energy prices spiked during the 1979 oil crisis

. When prices dropped in the early 1980s, funding for space solar power research dried up. His plan had also been based on NASA's estimates for the flight rate and launch cost of the Space Shuttle, numbers that turned out to have been wildly optimistic. His 1977 book quoted a Space Shuttle launch cost of $10 million, but in 1981 the subsidized price given to commercial customers started at $38 million. Eventual accounting of the full cost of a launch in 1985 raised this as high as $180 million per flight.

O'Neill was appointed by United States President Ronald Reagan

to the National Commission on Space in 1985. The commission, led by former NASA administrator Thomas Paine

, proposed that the government commit to opening the inner Solar System for human settlement within 50 years. Their report was released in May 1986, four months after the Space Shuttle Challenger

broke up on ascent.

O'Neill's popular science book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

O'Neill's popular science book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

(1977) combined fictional accounts of space settlers with an explanation of his plan to build space colonies. Its publication established him as the spokesman for the space colonization movement. It won the Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science

that year, and prompted Swarthmore College to grant him an honorary doctorate

. The High Frontier has been translated into five languages and remained in print as of 2008.

His 1981 book 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future

was an exercise in futurology. O'Neill narrated it as a visitor to Earth from a space colony beyond Pluto. The book explored the effects of technologies he called "drivers of change" on the coming century. Some technologies he described were space colonies, solar power satellites, anti-aging drugs, hydrogen-propelled cars

, climate control, and underground magnetic trains

. He left the social structure of the 1980s intact, assuming that humanity would remain unchanged even as it expanded into the Solar System. Reviews of 2081 were mixed. New York Times reviewer John Noble Wilford found the book "imagination-stirring", but Charles Nicol

thought the technologies described were unacceptably far-fetched.

In his book The Technology Edge, published in 1983, O'Neill wrote about economic competition with Japan. He argued that the United States had to develop six industries to compete: microengineering

, robotics, genetic engineering, magnetic flight

, family aircraft

, and space science. He also thought that industrial development was suffering from short-sighted executives, self-interested unions, high taxes, and poor education of Americans. According to reviewer Henry Weil, O'Neill's detailed explanations of emerging technologies differentiated the book from others on the subject.

O'Neill founded Geostar Corporation to develop a satellite position determination system for which he was granted a patent in 1982. The system, primarily intended to track aircraft, was called Radio Determination Satellite Service (RDSS). In April 1983 Geostar applied to the FCC for a license to broadcast from three satellites, which would cover the entire United States. Geostar launched GSTAR-2 into geosynchronous orbit

O'Neill founded Geostar Corporation to develop a satellite position determination system for which he was granted a patent in 1982. The system, primarily intended to track aircraft, was called Radio Determination Satellite Service (RDSS). In April 1983 Geostar applied to the FCC for a license to broadcast from three satellites, which would cover the entire United States. Geostar launched GSTAR-2 into geosynchronous orbit

in 1986. Its transmitter

package permanently failed two months later, so Geostar began tests of RDSS by transmitting from other satellites. With his health failing, O'Neill became less involved with the company at the same time it started to run into trouble. In February 1991 Geostar filed for bankruptcy and its licenses were sold to Motorola

for the Iridium satellite constellation

project. Although the system was eventually replaced by GPS

, O'Neill made significant advances in the field of position determination.

O'Neill founded O'Neill Communications in Princeton in 1986. He introduced his Local Area Wireless Networking, or LAWN, system at the PC Expo in New York in 1989. The LAWN system allowed two computers to exchange messages over a range of a couple hundred feet at a cost of about $500 per node. O'Neill Communications went out of business in 1993; the LAWN technology was sold to Omnispread Communications. As of 2008, Omnispread continued to sell a variant of O'Neill's LAWN system.

On November 18, 1991, O'Neill filed a patent application for a high-speed train

system. He called the company he wanted to form VSE International, for velocity, silence, and efficiency. However, the concept itself he called Magnetic Flight. The vehicles, instead of running on a pair of tracks, would be elevated using electromagnetic force by a single track within a tube (permanent magnets in the track, with variable magnets on the vehicle), and propelled by electromagnetic forces through tunnels. He estimated the trains could reach speeds of up to 2,500 mph (4,000 km/h) — about five times faster than a jet airliner — if the air was evacuated from the tunnels. To obtain such speeds, the vehicle would accelerate for the first half of the trip, and then decelerate for the second half of the trip. The acceleration was planned to be a maximum of about one-half of the force of gravity. O'Neill planned to build a network of stations connected by these tunnels, but he died two years before his first patent on it was granted.

O'Neill was diagnosed with leukemia

O'Neill was diagnosed with leukemia

in 1985. He died on April 27, 1992, from complications of the disease at the Sequoia Hospital

in Redwood City, California

. He was survived by his wife Tasha, his ex-wife Sylvia, and his four children. A sample of his incinerated remains was buried in space

. The vial containing his ashes was attached to a Pegasus XL

rocket and launched into Earth orbit on April 21, 1997. It later re-entered the atmosphere in May 2002.

O'Neill directed his Space Studies Institute to continue their efforts "until people are living and working in space". After his death, management of SSI was passed to his son Roger and colleague Freeman Dyson. SSI continued to hold conferences every other year to bring together scientists studying space colonization until 2001.

Henry Kolm went on to start Magplane Technology in the 1990s to develop the magnetic transportation technology that O'Neill had written about. In 2007, Magplane demonstrated a working magnetic pipeline system to transport phosphate ore in Florida. The system ran at a speed of 40 mph (65 km/h), far slower than the high-speed trains O'Neill envisioned.

One supporter of O'Neill's ideas was Rick Tumlinson

, who worked under O'Neill at the Space Studies Institute. Tumlinson co-founded the Space Frontier Foundation

, an organization that supports O'Neill's concepts of large-scale space colonization. In 2004 Tumlinson held up three men as models for space advocacy: Wernher von Braun

, Gerard K. O'Neill, and Carl Sagan

. Von Braun pushed for "projects that ordinary people can be proud of but not participate in". Sagan wanted to explore the universe from a distance. O'Neill, with his grand scheme for settlement of the Solar System, emphasized moving ordinary people off the Earth "en masse".

The National Space Society

(NSS) gives the Gerard K. O'Neill Memorial Award for Space Settlement Advocacy to individuals noted for their contributions in the area of space settlement. Their contributions can be scientific, legislative, and educational. The award is a trophy cast in the shape of a Bernal sphere

. The NSS first bestowed the award in 2007 on lunar entrepreneur and former astronaut Harrison Schmitt

. In 2008, it was given to physicist John Marburger

.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

physicist

Physicist

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole...

and space activist. As a faculty member of Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

, he invented a device called the particle storage ring

Storage ring

A storage ring is a type of circular particle accelerator in which a continuous or pulsed particle beam may be kept circulating for a long period of time, up to many hours. Storage of a particular particle depends upon the mass, energy and usually charge of the particle being stored...

for high-energy physics experiments. Later, he invented a magnetic launcher called the mass driver

Mass driver

A mass driver or electromagnetic catapult is a proposed method of non-rocket spacelaunch which would use a linear motor to accelerate and catapult payloads up to high speeds. All existing and contemplated mass drivers use coils of wire energized by electricity to make electromagnets. Sequential...

. In the 1970s, he developed a plan to build human settlements in outer space, including a space habitat

Space habitat

A space habitat is a space station intended as a permanent settlement rather than as a simple waystation or other specialized facility...

design known as the O'Neill cylinder. He founded the Space Studies Institute

Space Studies Institute

Space Studies Institute is a non-profit organization that was founded in 1977 by the late Princeton University Professor Dr. Gerard K. O'Neill. The stated mission is to "open the energy and material resources of space for human benefit within our lifetime"...

, an organization devoted to funding research into space manufacturing

Space manufacturing

Space manufacturing is the production of manufactured goods in an environment outside a planetary atmosphere. Typically this includes conditions of microgravity and hard vacuum.Manufacturing in space has several potential advantages over Earth-based industry....

and colonization

Space colonization

Space colonization is the concept of permanent human habitation outside of Earth. Although hypothetical at the present time, there are many proposals and speculations about the first space colony...

.

O'Neill began researching high-energy particle physics

Particle physics

Particle physics is a branch of physics that studies the existence and interactions of particles that are the constituents of what is usually referred to as matter or radiation. In current understanding, particles are excitations of quantum fields and interact following their dynamics...

at Princeton

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

in 1954 after he received his doctorate from Cornell University

Cornell University

Cornell University is an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, United States. It is a private land-grant university, receiving annual funding from the State of New York for certain educational missions...

. Two years later, he published his theory for a particle storage ring. This invention allowed particle physics experiments

Particle physics experiments

Particle physics experiments briefly discusses a number of past, present, and proposed experiments with particle accelerators, throughout the world. In addition, some important accelerator interactions are discussed...

at much higher energies than had previously been possible. In 1965 at Stanford University

Stanford University

The Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

, he performed the first colliding beam physics experiment.

While teaching physics at Princeton, O'Neill became interested in the possibility that humans could live in outer space. He researched and proposed a futuristic idea for human settlement in space, the O'Neill cylinder, in "The Colonization of Space", his first paper on the subject. He held a conference on space manufacturing

Space manufacturing

Space manufacturing is the production of manufactured goods in an environment outside a planetary atmosphere. Typically this includes conditions of microgravity and hard vacuum.Manufacturing in space has several potential advantages over Earth-based industry....

at Princeton in 1975. Many who became post-Apollo-era space activists attended. O'Neill built his first mass driver prototype

Mass Driver 1

Constructed in 1976 and 1977, Mass Driver 1 was an early demonstration of the concept of the mass driver, a form of electromagnetic launcher, which in principle could also be configured as a rocket motor, using asteroidal materials for reaction mass and energized by solar or other electric power.As...

with professor Henry Kolm

Henry Kolm

Henry Herbert Kolm was an American physicist associated with MIT for many years, with extensive expertise in high-power magnets and strong magnetic fields.-Visiting Scientist at MIT:...

in 1976. He considered mass drivers critical for extracting the mineral resources of the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

and asteroid

Asteroid

Asteroids are a class of small Solar System bodies in orbit around the Sun. They have also been called planetoids, especially the larger ones...

s. His award-winning book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space is a 1976 book by Gerard K. O'Neill, a road map for what the United States might do in outer space after the Apollo program, the drive to place a man on the Moon. It envisions large manned habitats in the Earth-Moon system, especially near stable...

inspired a generation of space exploration advocates. He died of leukemia

Leukemia

Leukemia or leukaemia is a type of cancer of the blood or bone marrow characterized by an abnormal increase of immature white blood cells called "blasts". Leukemia is a broad term covering a spectrum of diseases...

in 1992.

Birth, education, and family life

O'Neill was born in Brooklyn, New YorkBrooklyn

Brooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

on February 6, 1927 to Edward Gerard O'Neill, a lawyer, and Dorothy Lewis O'Neill (née Kitchen). He had no siblings. His family moved to Speculator, New York

Speculator, New York

Speculator is a village in Hamilton County, New York, United States. The population was 348 at the 2000 census. The village is named after a nearby Speculator Mountain....

when his father temporarily retired for health reasons. For high school, O'Neill attended Newburgh Free Academy

Newburgh Free Academy

Newburgh Free Academy is the public high school educating all students in grades 10-12Newburgh Free Academy is the public high school educating all students in grades 10-12Newburgh Free Academy is the public high school educating all students in grades 10-12((now 9-12) in the Newburgh Enlarged City...

in Newburgh, New York. While he was a student there he edited the school newspaper and took a job as a news broadcaster at a local radio station. He graduated in 1944, during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, and enlisted in the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

on his 17th birthday. The Navy trained him as a radar technician, which sparked his interest in science.

After he was honorably discharged in 1946, O'Neill studied for an undergraduate degree in physics and mathematics at Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College is a private, independent, liberal arts college in the United States with an enrollment of about 1,500 students. The college is located in the borough of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, 11 miles southwest of Philadelphia....

. As a child he had discussed the possibilities of humans in space with his parents, and in college he enjoyed working on rocket equations. However, he did not see space science as an option for a career path in physics, choosing instead to pursue high-energy physics. In 1950 he graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors. O'Neill performed his graduate studies at Cornell University

Cornell University

Cornell University is an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, United States. It is a private land-grant university, receiving annual funding from the State of New York for certain educational missions...

with the help of an Atomic Energy Commission

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by Congress to foster and control the peace time development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S...

fellowship, and was awarded a Ph.D. in physics in 1954.

O'Neill married Sylvia Turlington, also a Swarthmore graduate, in June 1950. They had a son, Roger, and two daughters, Janet and Eleanor, before their marriage ended in divorce in 1966.

One of O'Neill's favorite activities was flying. He held instrument certifications in both powered and sailplane

Glider (sailplane)

A glider or sailplane is a type of glider aircraft used in the sport of gliding. Some gliders, known as motor gliders are used for gliding and soaring as well, but have engines which can, in some cases, be used for take-off or for extending a flight...

flight and held the FAI

FAI Gliding Commission

The International Gliding Commission is a leading international governing body for the sport of gliding.It is one of several Air Sport Commissions of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale , or "World Air Sports Federation"...

Diamond Badge, a gliding award. During his first cross-country glider flight in April 1973, he was assisted on the ground by Renate "Tasha" Steffen. He had met Tasha, who was 21 years younger than him, previously through the YMCA

YMCA

The Young Men's Christian Association is a worldwide organization of more than 45 million members from 125 national federations affiliated through the World Alliance of YMCAs...

International Club. They were married the day after his flight. They had a son, Edward O'Neill.

High-energy physics research

After graduating from Cornell, O'Neill accepted a position as an instructor at Princeton UniversityPrinceton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

. There he started his research into high-energy particle physics

Particle physics

Particle physics is a branch of physics that studies the existence and interactions of particles that are the constituents of what is usually referred to as matter or radiation. In current understanding, particles are excitations of quantum fields and interact following their dynamics...

. In 1956, his second year of teaching, his two-page letter titled "Storage-Ring Synchrotron: Device for High-Energy Physics Research" was published in Physical Review. It theorized that the particles produced by a particle accelerator

Particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a device that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to high speeds and to contain them in well-defined beams. An ordinary CRT television set is a simple form of accelerator. There are two basic types: electrostatic and oscillating field accelerators.In...

could be stored for a few seconds in a storage ring

Storage ring

A storage ring is a type of circular particle accelerator in which a continuous or pulsed particle beam may be kept circulating for a long period of time, up to many hours. Storage of a particular particle depends upon the mass, energy and usually charge of the particle being stored...

. The stored particles could then be directed to collide with another particle beam. This would increase the energy of the particle collision over the previous method, which directed the beam at a fixed target. His ideas were not immediately accepted by the physics community.

O'Neill became an assistant professor at Princeton in 1956, and was promoted to associate professor in 1959. He visited Stanford University in 1957 to meet with Professor Wolfgang K. H. Panofsky

Wolfgang K. H. Panofsky

Wolfgang Kurt Hermann "Pief" Panofsky , was a German-American physicist.-Early life:Panofsky was born the son of renowned art historian Erwin Panofsky in Berlin, Germany. He received his bachelor's degree from Princeton University in 1938 and obtained his PhD from Caltech in 1942. Around this time...

. This resulted in a collaboration between Princeton and Stanford to build the Colliding Beam Experiment (CBX). With a US$800,000 grant from the Office of Naval Research

Office of Naval Research

The Office of Naval Research , headquartered in Arlington, Virginia , is the office within the United States Department of the Navy that coordinates, executes, and promotes the science and technology programs of the U.S...

, construction on the first particle storage rings began in 1958 at the Stanford High-Energy Physics Laboratory. He figured out how to capture the particles and, by pumping the air out to produce a vacuum

Vacuum

In everyday usage, vacuum is a volume of space that is essentially empty of matter, such that its gaseous pressure is much less than atmospheric pressure. The word comes from the Latin term for "empty". A perfect vacuum would be one with no particles in it at all, which is impossible to achieve in...

, store them long enough to experiment on them. CBX stored its first beam on March 28, 1962. O'Neill became a full professor of physics in 1965.

Burton Richter

Burton Richter is a Nobel Prize-winning American physicist. He led the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center team which co-discovered the J/ψ meson in 1974, alongside the Brookhaven National Laboratory team led by Samuel Ting. This discovery was part of the so-called November Revolution of particle...

, O'Neill performed the first colliding beam physics experiment in 1965. In this experiment, particle beams from the Stanford Linear Accelerator were collected in his storage rings and then directed to collide at an energy of 600 MeV. At the time, this was the highest energy involved in a particle collision. The results proved that the charge of an electron is contained in a volume less than 100 attometers across. O'Neill considered his device to be capable of only seconds of storage, but, by creating an even stronger vacuum, others were able to increase this to hours. In 1979, he, with physicist David C. Cheng, wrote the graduate-level textbook Elementary Particle Physics: An Introduction. He retired from teaching in 1985, but remained associated with Princeton as professor emeritus until his death.

Origin of the idea (1969)

Brian O'Leary

Brian Todd O'Leary was an American scientist, author, and former NASA astronaut. He was a member of the sixth group of astronauts selected by NASA in August 1967...

, also a scientist-astronaut candidate, who became his good friend. O'Leary was selected for Astronaut Group 6

Astronaut Group 6

Astronaut Group 6 was announced by NASA on August 11, 1967, the second group of scientist-astronauts. Only five of the eleven were given formal assignments in Apollo, and these were all non-flying. Assignments for the group were delayed by the requirement to spend a full year at UPT to become...

but O'Neill was not.

O'Neill became interested in the idea of space colonization in 1969 while he was teaching freshman physics at Princeton University. His students were growing cynical about the benefits of science to humanity because of the controversy surrounding the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

. To give them something relevant to study, he began using examples from the Apollo program as applications of elementary physics. O'Neill posed the question during an extra seminar he gave to a few of his students: "Is the surface of a planet really the right place for an expanding technological civilization?" His students' research convinced him that the answer was no.

Centrifugal force

Centrifugal force can generally be any force directed outward relative to some origin. More particularly, in classical mechanics, the centrifugal force is an outward force which arises when describing the motion of objects in a rotating reference frame...

. With the population of the colony living on the inner surface of a sphere or cylinder, these structures resembled "inside-out planets". He found that pairing counter-rotating cylinders would eliminate the need to spin them using rockets. This configuration has since been known as the O'Neill cylinder.

First paper (1970–1974)

Looking for an outlet for his ideas, O'Neill wrote a paper titled "The Colonization of Space", and for four years attempted to have it published. He submitted it to several journals and magazines, including Scientific American and Science, only to have it rejected by the reviewers. During this time O'Neill gave lectures on space colonization at Hampshire CollegeHampshire College

Hampshire College is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was founded in 1965 as an experiment in alternative education, in association with four other colleges in the Pioneer Valley: Amherst College, Smith College, Mount Holyoke College, and the University of Massachusetts...

, Princeton, and other schools. Many students and staff attending the lectures became enthusiastic about the possibility of living in space. Another outlet for O'Neill to explore his ideas was with his children; on walks in the forest they speculated about life in a space colony. His paper finally appeared in the September 1974 issue of Physics Today

Physics Today

Physics Today, created in 1948, is the membership journal of the American Institute of Physics. It is provided to 130,000 members of twelve physics societies, including the American Physical Society...

. In it, he argued that building space colonies would solve several important problems:

Lagrangian point

The Lagrangian points are the five positions in an orbital configuration where a small object affected only by gravity can theoretically be stationary relative to two larger objects...

. and are stable points in the Solar System

Solar System

The Solar System consists of the Sun and the astronomical objects gravitationally bound in orbit around it, all of which formed from the collapse of a giant molecular cloud approximately 4.6 billion years ago. The vast majority of the system's mass is in the Sun...

where a spacecraft can maintain its position without expending energy. The paper was well received, but many who would begin work on the project had already been introduced to his ideas before it was even published. The paper received a few critical responses. Some questioned the practicality of lifting tens of thousands of people into orbit and his estimates for the production output of initial colonies.

While he was waiting for his paper to be published, O'Neill organized a small two-day conference in May 1974 at Princeton to discuss the possibility of colonizing outer space. The conference, titled First Conference on Space Colonization, was funded by Stewart Brand's Point Foundation

Point Foundation (environment)

The Point Foundation was a nonprofit organization based in San Francisco and founded by Stewart Brand and Dick Raymond. It published works related to the Whole Earth Catalog. It was also a co-owner of The WELL.-References:...

and Princeton University. Among those who attended were Eric Drexler (at the time a freshman at MIT

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

), scientist-astronaut Joe Allen (from Astronaut Group 6), Freeman Dyson

Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson FRS is a British-born American theoretical physicist and mathematician, famous for his work in quantum field theory, solid-state physics, astronomy and nuclear engineering. Dyson is a member of the Board of Sponsors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists...

, and science reporter Walter Sullivan

Walter S. Sullivan

Walter Seager Sullivan, Jr was considered the "dean" of science writers.Sullivan spent most of his career as a science reporter for the New York Times...

. Representatives from NASA also attended and brought estimates of launch costs expected on the planned Space Shuttle

Space Shuttle program

NASA's Space Shuttle program, officially called Space Transportation System , was the United States government's manned launch vehicle program from 1981 to 2011...

. O'Neill thought of the attendees as "a band of daring radicals". Sullivan's article on the conference was published on the front page of The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

on May 13, 1974. As media coverage grew, O'Neill was inundated with letters from people who were excited about living in space. To stay in touch with them, O'Neill began keeping a mailing list and started sending out updates on his progress. A few months later he heard Peter Glaser

Peter Glaser

Peter Edward Glaser is an American scientist and aerospace engineer. He served as Vice President, Advanced Technology , was employed at Arthur D. Little, Inc., Cambridge, MA ; subsequently he served as a consultant to the company . He was president of Power from Space Consultants...

speak about solar power satellites at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Goddard Space Flight Center

The Goddard Space Flight Center is a major NASA space research laboratory established on May 1, 1959 as NASA's first space flight center. GSFC employs approximately 10,000 civil servants and contractors, and is located approximately northeast of Washington, D.C. in Greenbelt, Maryland, USA. GSFC,...

. O'Neill realized that, by building these satellites, his space colonies could quickly recover the cost of their construction. According to O'Neill, "the profound difference between this and everything else done in space is the potential of generating large amounts of new wealth".

NASA studies (1975–1977)

O'Neill held a much larger conference the following May titled Princeton University Conference on Space Manufacturing. At this conference more than two dozen speakers presented papers, including KeithKeith Henson

Howard Keith Henson is an American electrical engineer and writer on life extension, cryonics, memetics and evolutionary psychology....

and Carolyn Henson

Carolyn Meinel

Carolyn P. Meinel was notable in the hacking scene during the 1990s. Her books and website, called The Happy Hacker, are dedicated to a style known as script kiddie hacking...

from Tucson, Arizona

Tucson, Arizona

Tucson is a city in and the county seat of Pima County, Arizona, United States. The city is located 118 miles southeast of Phoenix and 60 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. The 2010 United States Census puts the city's population at 520,116 with a metropolitan area population at 1,020,200...

.

After the conference Carolyn Henson arranged a meeting between O'Neill and Arizona Congressman Morris Udall

Mo Udall

Morris King "Mo" Udall was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative from Arizona from May 2, 1961 to May 4, 1991...

. Udall wrote a letter of support, which he asked the Hensons to publicize, for O'Neill's work. The Hensons included his letter in the first issue of the L-5 Society

L5 Society

The L5 Society was founded in 1975 by Carolyn and Keith Henson to promote the space colony ideas of Dr Gerard K. O'Neill.The name comes from the and Lagrangian points in the Earth-Moon system proposed as locations for the huge rotating space habitats that Dr O'Neill envisioned...

newsletter, sent to everyone on O'Neill's mailing list and those who had signed up at the conference.

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications. On January 19, 1976, he also appeared before the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

Subcommittee on Aerospace Technology and National Needs. In a presentation titled Solar Power from Satellites, he laid out his case for an Apollo-style program for building power plants in space. He returned to Ames in June 1976 and 1977 to lead studies on space manufacturing. In these studies, NASA developed detailed plans to establish bases on the Moon where space-suited workers would mine the mineral resources needed to build space colonies and solar power satellites.

Private funding (1977–1978)

Although NASA was supporting his work with grants of up to $500,000 per year, O'Neill became frustrated by the bureaucracy and politics inherent in government funded research. He thought that small privately funded groups could develop space technology faster than government agencies. In 1977, O'Neill and his wife Tasha founded the Space Studies InstituteSpace Studies Institute

Space Studies Institute is a non-profit organization that was founded in 1977 by the late Princeton University Professor Dr. Gerard K. O'Neill. The stated mission is to "open the energy and material resources of space for human benefit within our lifetime"...

, a non-profit organization, at Princeton University. SSI received initial funding of almost $100,000 from private donors, and in early 1978 began to support basic research into technologies needed for space manufacturing and settlement.

Space Studies Institute

Space Studies Institute is a non-profit organization that was founded in 1977 by the late Princeton University Professor Dr. Gerard K. O'Neill. The stated mission is to "open the energy and material resources of space for human benefit within our lifetime"...

first grants funded the development of the mass driver

Mass driver

A mass driver or electromagnetic catapult is a proposed method of non-rocket spacelaunch which would use a linear motor to accelerate and catapult payloads up to high speeds. All existing and contemplated mass drivers use coils of wire energized by electricity to make electromagnets. Sequential...

, a device first proposed by O'Neill in 1974. Mass drivers are based on the coilgun

Coilgun

A coilgun is a type of projectile accelerator that consists of one or more coils used as electromagnets in the configuration of a synchronous linear motor which accelerate a magnetic projectile to high velocity...

design, adapted to accelerate a non-magnetic object. One application O'Neill proposed for mass drivers was to throw baseball-sized chunks of ore mined from the surface of the Moon into space. Once in space, the ore could be used as raw material for building space colonies and solar power satellites. He took a sabbatical from Princeton to work on mass drivers at MIT. There he served as the Hunsaker Visiting Professor of Aerospace

Jerome C. Hunsaker Visiting Professor of Aerospace Systems

The Jerome C. Hunsaker Visiting Professor of Aerospace Systems is a professorship established in 1954 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. It is named after MIT professor Jerome Hunsaker in honor of his achievements in aeronautical engineering...

during the 1976–77 academic year. At MIT, he, Henry H. Kolm

Henry Kolm

Henry Herbert Kolm was an American physicist associated with MIT for many years, with extensive expertise in high-power magnets and strong magnetic fields.-Visiting Scientist at MIT:...

, and a group of student volunteers built their first mass driver prototype

Mass Driver 1

Constructed in 1976 and 1977, Mass Driver 1 was an early demonstration of the concept of the mass driver, a form of electromagnetic launcher, which in principle could also be configured as a rocket motor, using asteroidal materials for reaction mass and energized by solar or other electric power.As...

. The eight-foot (2.5 m) long prototype could apply 33 g

G-force

The g-force associated with an object is its acceleration relative to free-fall. This acceleration experienced by an object is due to the vector sum of non-gravitational forces acting on an object free to move. The accelerations that are not produced by gravity are termed proper accelerations, and...

(320 m/s2) of acceleration to an object inserted into it. With financial assistance from SSI, later prototypes improved this to 1,800 g (18,000 m/s2), enough acceleration that a mass driver only 520 feet (160 m) long could launch material off the surface of the Moon.

Opposition (1977–1985)

In 1977, O'Neill saw the peak of interest in space colonization, along with the publication of his first book, The High FrontierThe High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space is a 1976 book by Gerard K. O'Neill, a road map for what the United States might do in outer space after the Apollo program, the drive to place a man on the Moon. It envisions large manned habitats in the Earth-Moon system, especially near stable...

. He and his wife were flying between meetings, interviews, and hearings. On October 9, the CBS

CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc. is a major US commercial broadcasting television network, which started as a radio network. The name is derived from the initials of the network's former name, Columbia Broadcasting System. The network is sometimes referred to as the "Eye Network" in reference to the shape of...

program 60 Minutes

60 Minutes

60 Minutes is an American television news magazine, which has run on CBS since 1968. The program was created by producer Don Hewitt who set it apart by using a unique style of reporter-centered investigation....

ran a segment about space colonies. Later they aired responses from the viewers, which included one from Senator William Proxmire

William Proxmire

Edward William Proxmire was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States Senator from Wisconsin from 1957 to 1989.-Personal life:...

, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee responsible for NASA's budget. His response was, "it's the best argument yet for chopping NASA's funding to the bone .... I say not a penny for this nutty fantasy". He successfully eliminated spending on space colonization research from the budget. In 1978, Paul Werbos

Paul Werbos

Paul J. Werbos is a scientist best known for his 1974 Harvard University Ph.D. thesis, which first described the process of training artificial neural networks through backpropagation of errors. The thesis, and some supplementary information, can be found in his book, The Roots of Backpropagation...

wrote for the L-5 newsletter, "no one expects Congress to commit us to O'Neill's concept of large-scale space habitats; people in NASA are almost paranoid about the public relations aspects of the idea". When it became clear that a government funded colonization effort was politically impossible, popular support for O'Neill's ideas started to evaporate.

Other pressures on O'Neill's colonization plan were the high cost of access to Earth orbit and the declining cost of energy. Building solar power stations in space was economically attractive when energy prices spiked during the 1979 oil crisis

1979 energy crisis

The 1979 oil crisis in the United States occurred in the wake of the Iranian Revolution. Amid massive protests, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, fled his country in early 1979 and the Ayatollah Khomeini soon became the new leader of Iran. Protests severely disrupted the Iranian oil...

. When prices dropped in the early 1980s, funding for space solar power research dried up. His plan had also been based on NASA's estimates for the flight rate and launch cost of the Space Shuttle, numbers that turned out to have been wildly optimistic. His 1977 book quoted a Space Shuttle launch cost of $10 million, but in 1981 the subsidized price given to commercial customers started at $38 million. Eventual accounting of the full cost of a launch in 1985 raised this as high as $180 million per flight.

O'Neill was appointed by United States President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

to the National Commission on Space in 1985. The commission, led by former NASA administrator Thomas Paine

Thomas O. Paine

Thomas Otten Paine , American scientist, was the third Administrator of NASA, serving from March 21, 1969 to September 15, 1970.During his administration at NASA, the first seven Apollo manned missions were flown...

, proposed that the government commit to opening the inner Solar System for human settlement within 50 years. Their report was released in May 1986, four months after the Space Shuttle Challenger

Space Shuttle Challenger

Space Shuttle Challenger was NASA's second Space Shuttle orbiter to be put into service, Columbia having been the first. The shuttle was built by Rockwell International's Space Transportation Systems Division in Downey, California...

broke up on ascent.

Writing career

The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space

The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space is a 1976 book by Gerard K. O'Neill, a road map for what the United States might do in outer space after the Apollo program, the drive to place a man on the Moon. It envisions large manned habitats in the Earth-Moon system, especially near stable...

(1977) combined fictional accounts of space settlers with an explanation of his plan to build space colonies. Its publication established him as the spokesman for the space colonization movement. It won the Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science

Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science

The Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science is given annually by the Phi Beta Kappa Society to authors of significant books in the fields of science and mathematics. The award was first given in 1959 to anthropologist Loren Eiseley.-Award winners:-References:...

that year, and prompted Swarthmore College to grant him an honorary doctorate

Honorary degree

An honorary degree or a degree honoris causa is an academic degree for which a university has waived the usual requirements, such as matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations...

. The High Frontier has been translated into five languages and remained in print as of 2008.

His 1981 book 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future

2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future

Princeton physicist Gerard K. O'Neill's 1981 book, 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future was an attempt to predict the technological and social state of humanity 100 years in the future. O'Neill's positive attitude towards both technology and human potential distinguished this book from gloomy...

was an exercise in futurology. O'Neill narrated it as a visitor to Earth from a space colony beyond Pluto. The book explored the effects of technologies he called "drivers of change" on the coming century. Some technologies he described were space colonies, solar power satellites, anti-aging drugs, hydrogen-propelled cars

Hydrogen vehicle

A hydrogen vehicle is a vehicle that uses hydrogen as its onboard fuel for motive power. Hydrogen vehicles include hydrogen fueled space rockets, as well as automobiles and other transportation vehicles...

, climate control, and underground magnetic trains

Maglev train

Maglev , is a system of transportation that uses magnetic levitation to suspend, guide and propel vehicles from magnets rather than using mechanical methods, such as friction-reliant wheels, axles and bearings...

. He left the social structure of the 1980s intact, assuming that humanity would remain unchanged even as it expanded into the Solar System. Reviews of 2081 were mixed. New York Times reviewer John Noble Wilford found the book "imagination-stirring", but Charles Nicol

Charles Nicol

Charles Nicol is known primarily as an expert on the life and works of author Vladimir Nabokov, and also writes widely on fiction and popular culture. He is a retired Professor in the Department of English at Indiana State University.-Academic and Publishing History:Nicol has been publishing on...

thought the technologies described were unacceptably far-fetched.

In his book The Technology Edge, published in 1983, O'Neill wrote about economic competition with Japan. He argued that the United States had to develop six industries to compete: microengineering

Microfabrication

Microfabrication is the term that describes processes of fabrication of miniature structures, of micrometre sizes and smaller. Historically the earliest microfabrication processes were used for integrated circuit fabrication, also known as "semiconductor manufacturing" or "semiconductor device...

, robotics, genetic engineering, magnetic flight

Magnetic levitation

Magnetic levitation, maglev, or magnetic suspension is a method by which an object is suspended with no support other than magnetic fields...

, family aircraft

Flying car (fiction)

In fiction, a flying car is a car that can be flown in much the same way as a car may be driven. In some cases such flying cars can also be driven on roads....

, and space science. He also thought that industrial development was suffering from short-sighted executives, self-interested unions, high taxes, and poor education of Americans. According to reviewer Henry Weil, O'Neill's detailed explanations of emerging technologies differentiated the book from others on the subject.

Entrepreneurial efforts

Geosynchronous orbit

A geosynchronous orbit is an orbit around the Earth with an orbital period that matches the Earth's sidereal rotation period...

in 1986. Its transmitter

Transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications a transmitter or radio transmitter is an electronic device which, with the aid of an antenna, produces radio waves. The transmitter itself generates a radio frequency alternating current, which is applied to the antenna. When excited by this alternating...

package permanently failed two months later, so Geostar began tests of RDSS by transmitting from other satellites. With his health failing, O'Neill became less involved with the company at the same time it started to run into trouble. In February 1991 Geostar filed for bankruptcy and its licenses were sold to Motorola

Motorola

Motorola, Inc. was an American multinational telecommunications company based in Schaumburg, Illinois, which was eventually divided into two independent public companies, Motorola Mobility and Motorola Solutions on January 4, 2011, after losing $4.3 billion from 2007 to 2009...

for the Iridium satellite constellation

Iridium satellite constellation

The Iridium satellite constellation is a large group of satellites providing voice and data coverage to satellite phones, pagers and integrated transceivers over Earth's entire surface. Iridium Communications Inc...

project. Although the system was eventually replaced by GPS

Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System is a space-based global navigation satellite system that provides location and time information in all weather, anywhere on or near the Earth, where there is an unobstructed line of sight to four or more GPS satellites...

, O'Neill made significant advances in the field of position determination.

O'Neill founded O'Neill Communications in Princeton in 1986. He introduced his Local Area Wireless Networking, or LAWN, system at the PC Expo in New York in 1989. The LAWN system allowed two computers to exchange messages over a range of a couple hundred feet at a cost of about $500 per node. O'Neill Communications went out of business in 1993; the LAWN technology was sold to Omnispread Communications. As of 2008, Omnispread continued to sell a variant of O'Neill's LAWN system.

On November 18, 1991, O'Neill filed a patent application for a high-speed train

High-speed rail

High-speed rail is a type of passenger rail transport that operates significantly faster than the normal speed of rail traffic. Specific definitions by the European Union include for upgraded track and or faster for new track, whilst in the United States, the U.S...

system. He called the company he wanted to form VSE International, for velocity, silence, and efficiency. However, the concept itself he called Magnetic Flight. The vehicles, instead of running on a pair of tracks, would be elevated using electromagnetic force by a single track within a tube (permanent magnets in the track, with variable magnets on the vehicle), and propelled by electromagnetic forces through tunnels. He estimated the trains could reach speeds of up to 2,500 mph (4,000 km/h) — about five times faster than a jet airliner — if the air was evacuated from the tunnels. To obtain such speeds, the vehicle would accelerate for the first half of the trip, and then decelerate for the second half of the trip. The acceleration was planned to be a maximum of about one-half of the force of gravity. O'Neill planned to build a network of stations connected by these tunnels, but he died two years before his first patent on it was granted.

Death and legacy

Leukemia

Leukemia or leukaemia is a type of cancer of the blood or bone marrow characterized by an abnormal increase of immature white blood cells called "blasts". Leukemia is a broad term covering a spectrum of diseases...

in 1985. He died on April 27, 1992, from complications of the disease at the Sequoia Hospital

Sequoia Hospital

Sequoia Hospital is a hospital in Redwood City,California, USA. It is operated by Catholic Healthcare West.-Founding:In 1938, a group of nine women led by Mrs. Henry Beeger appealed to the city council in Redwood City for a hospital to serve the communities of southern San Mateo County. The city...

in Redwood City, California

Redwood City, California

Redwood City is a California charter city located on the San Francisco Peninsula in Northern California, approximately 27 miles south of San Francisco, and 24 miles north of San Jose. Redwood City's history spans from its earliest inhabitation by the Ohlone people, to its tradition as a port for...

. He was survived by his wife Tasha, his ex-wife Sylvia, and his four children. A sample of his incinerated remains was buried in space

Space burial

Space burial is a burial procedure in which a small sample of the cremated ashes of the deceased are placed in a capsule the size of a tube of lipstick and are launched into space using a rocket...

. The vial containing his ashes was attached to a Pegasus XL

Pegasus rocket

The Pegasus rocket is a winged space launch vehicle capable of carrying small, unmanned payloads into low Earth orbit. It is air-launched, as part of an expendable launch system developed by Orbital Sciences Corporation . Three main stages burning solid propellant provide the thrust...

rocket and launched into Earth orbit on April 21, 1997. It later re-entered the atmosphere in May 2002.

O'Neill directed his Space Studies Institute to continue their efforts "until people are living and working in space". After his death, management of SSI was passed to his son Roger and colleague Freeman Dyson. SSI continued to hold conferences every other year to bring together scientists studying space colonization until 2001.

Henry Kolm went on to start Magplane Technology in the 1990s to develop the magnetic transportation technology that O'Neill had written about. In 2007, Magplane demonstrated a working magnetic pipeline system to transport phosphate ore in Florida. The system ran at a speed of 40 mph (65 km/h), far slower than the high-speed trains O'Neill envisioned.

One supporter of O'Neill's ideas was Rick Tumlinson

Rick Tumlinson

Rick Tumlinson is the co-founder of the Space Frontier Foundation and a space activist. He has testified on space-related topics before the U.S. Congress six times since 1995...

, who worked under O'Neill at the Space Studies Institute. Tumlinson co-founded the Space Frontier Foundation

Space Frontier Foundation

The Space Frontier Foundation is a space advocacy nonprofit corporation organized to promote the interests of increased involvement of the private sector, in collaboration with government, in the exploration and development of space...

, an organization that supports O'Neill's concepts of large-scale space colonization. In 2004 Tumlinson held up three men as models for space advocacy: Wernher von Braun

Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian, Freiherr von Braun was a German rocket scientist, aerospace engineer, space architect, and one of the leading figures in the development of rocket technology in Nazi Germany during World War II and in the United States after that.A former member of the Nazi party,...

, Gerard K. O'Neill, and Carl Sagan

Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan was an American astronomer, astrophysicist, cosmologist, author, science popularizer and science communicator in astronomy and natural sciences. He published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books...

. Von Braun pushed for "projects that ordinary people can be proud of but not participate in". Sagan wanted to explore the universe from a distance. O'Neill, with his grand scheme for settlement of the Solar System, emphasized moving ordinary people off the Earth "en masse".

The National Space Society

National Space Society

The National Space Society is an international nonprofit 501, educational, and scientific organization specializing in space advocacy...

(NSS) gives the Gerard K. O'Neill Memorial Award for Space Settlement Advocacy to individuals noted for their contributions in the area of space settlement. Their contributions can be scientific, legislative, and educational. The award is a trophy cast in the shape of a Bernal sphere

Bernal sphere

A Bernal sphere is a type of space habitat intended as a long-term home for permanent residents, first proposed in 1929 by John Desmond Bernal....

. The NSS first bestowed the award in 2007 on lunar entrepreneur and former astronaut Harrison Schmitt

Harrison Schmitt

Harrison Hagan "Jack" Schmitt is an American geologist, a retired NASA astronaut, university professor, and a former U.S. senator from New Mexico....

. In 2008, it was given to physicist John Marburger

John Marburger

John Harmen Marburger, III was an American physicist who directed the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the administration of President George W. Bush, thus serving as the Science Advisor to the President...

.

Patents

O'Neill was granted six patents in total (two posthumously) in the areas of global position determination and magnetic levitation. Satellite-based vehicle position determining system, granted November 16, 1982 Satellite-based position determining and message transfer system with monitoring of link quality, granted May 10, 1988 Position determination and message transfer system employing satellites and stored terrain map, granted June 13, 1989 Position determination and message transfer system employing satellites and stored terrain map, granted October 23, 1990 High speed transport system, granted February 1, 1994 High speed transport system, granted July 18, 1995See also

- Konstantin Tsiolkovskii (1857–1935) wrote about humans living in space in the 1920s

- J. D. Bernal (1901–1971) inventor of the Bernal sphere, a space habitat design

- Rolf WideröeRolf WideröeRolf Widerøe , was a Norwegian particle physicist who was the originator of many particle acceleration concepts, including the resonance accelerator, the betatron accelerator.-Early life:...

(1902–1996) filed for a patent on a particle storage ring design during World War II - Krafft EhrickeKrafft Arnold Ehricke-External links:* * *...

(1917–1984) rocket engineer and space colonization advocate - John S. LewisJohn S. LewisJohn S. Lewis is a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. His interests in the chemistry and formation of the solar system and the economic development of space have made him a leading proponent of turning potentially hazardous near-Earth...

, wrote about the resources of the Solar System in Mining the SkyMining the Sky: Untold Riches from the Asteroids, Comets, and PlanetsMining the Sky: Untold Riches from the Asteroids, Comets, and Planets is a book by John S. Lewis which discusses the development of interplanetary space within our solar system.... - Marshall SavageMarshall SavageMarshall Thomas Savage is an advocate of space travel who wrote The Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy Steps and founded the Living Universe Foundation, which was designed to make plans for stellar exploration over the next 1,000 years....

, author of The Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy StepsThe Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy StepsThe Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy Steps by Marshall T. Savage is a book in the field of Exploratory engineering that gives a series of concrete stages the author believes will lead to interstellar colonization... - SpomeSpomeA spome is any hypothetical system closed with respect to matter and open with respect to energy capable of sustaining human life indefinitely. The term was coined in 1966 by Isaac Asimov in a paper entitled "There’s No Place Like Spome", published in Atmosphere in Space Cabins and Closed...

- Space architectureSpace architectureSpace architecture, in its simplest definition, is the theory and practice of designing and building inhabited environments in outer space. The architectural approach to spacecraft design addresses the total built environment, drawing from diverse disciplines including physiology, psychology, and...

- Space-based solar power