History of the Teller–Ulam design

Encyclopedia

Teller-Ulam design

The Teller–Ulam design is the nuclear weapon design concept used in most of the world's nuclear weapons. It is colloquially referred to as "the secret of the hydrogen bomb" because it employs hydrogen fusion, though in most applications the bulk of its destructive energy comes from uranium fission,...

, the technical concept behind modern thermonuclear weapons, also known as the hydrogen bomb.

Teller's "Super"

The idea of using the energy from a fission device to begin a fusion reaction was first proposed casually by the Italian physicist Enrico FermiEnrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi was an Italian-born, naturalized American physicist particularly known for his work on the development of the first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and for his contributions to the development of quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics...

to his Hungarian physicist colleague Edward Teller

Edward Teller

Edward Teller was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist, known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb," even though he did not care for the title. Teller made numerous contributions to nuclear and molecular physics, spectroscopy , and surface physics...

in the fall of 1941 during what would soon become the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

, the World War II effort by the United States and United Kingdom to develop the first nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s. Teller soon was a participant at Robert Oppenheimer

Robert Oppenheimer

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project, the World War II project that developed the first...

's summer conference on the development of a fission bomb held at the University of California, Berkeley

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

, where he guided discussion towards the idea of creating his "Super" bomb, which would hypothetically be many times more powerful than the yet-undeveloped fission weapon. Teller assumed creating the fission bomb would be nothing more than an engineering problem, and that the "Super" provided a much more interesting theoretical challenge.

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

where he worked (much of the work Teller declined to do was given instead, it turns out, to Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II...

, who was later discovered to be a spy for the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

). Teller was given some resources with which to study the "Super", and contacted his friend Maria Göppert-Mayer to help with laborious calculations relating to opacity

Opacity (optics)

Opacity is the measure of impenetrability to electromagnetic or other kinds of radiation, especially visible light. In radiative transfer, it describes the absorption and scattering of radiation in a medium, such as a plasma, dielectric, shielding material, glass, etc...

. The "Super", however, proved elusive, and the calculations were incredibly difficult to perform, especially since there was no existing way to run small-scale tests of the principles involved (in comparison, the properties of fission could be more easily probed with cyclotron

Cyclotron

In technology, a cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator. In physics, the cyclotron frequency or gyrofrequency is the frequency of a charged particle moving perpendicularly to the direction of a uniform magnetic field, i.e. a magnetic field of constant magnitude and direction...

s, newly created nuclear reactor

Nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device to initiate and control a sustained nuclear chain reaction. Most commonly they are used for generating electricity and for the propulsion of ships. Usually heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid , which runs through turbines that power either ship's...

s, and various other tests).

After the atomic bombings of Japan

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

, many scientists at Los Alamos rebelled against the notion of creating a weapon thousands of times more powerful than the first atomic bombs. For the scientists the question was in part technical—the weapon design was still quite uncertain and unworkable—and in part moral: such a weapon, they argued, could only be used against large civilian populations, and could thus only be used as a weapon of genocide. Many scientists, such as Teller's colleague Hans Bethe

Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe was a German-American nuclear physicist, and Nobel laureate in physics for his work on the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis. A versatile theoretical physicist, Bethe also made important contributions to quantum electrodynamics, nuclear physics, solid-state physics and...

(who had discovered stellar nucleosynthesis

Stellar nucleosynthesis

Stellar nucleosynthesis is the collective term for the nuclear reactions taking place in stars to build the nuclei of the elements heavier than hydrogen. Some small quantity of these reactions also occur on the stellar surface under various circumstances...

, the nuclear fusion which takes place in the sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

), urged that the United States should not develop such weapons and set an example towards the Soviet Union. Promoters of the weapon, including Teller and Berkeley physicists Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was an American physicist and Nobel Laureate, known for his invention, utilization, and improvement of the cyclotron atom-smasher beginning in 1929, based on his studies of the works of Rolf Widerøe, and his later work in uranium-isotope separation for the Manhattan Project...

and Luis Alvarez

Luis Alvarez

Luis W. Alvarez was an American experimental physicist and inventor, who spent nearly all of his long professional career on the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley...

, argued that such a development was inevitable, and to deny such protection to the people of the United States—especially when the Soviet Union was likely to create such a weapon themselves—was itself an immoral and unwise act. Still others, such as Oppenheimer, simply thought that the existing stockpile of fissile material was better spent in attempting to develop a large fleet of tactical atomic weapons rather than potentially squandered on the development of a few massive "Supers".

When the Soviet Union exploded their own atomic bomb (dubbed "Joe 1

Joe 1

The RDS-1 , also known as First Lightning , was the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. In the west, it was code-named Joe-1, in reference to Joseph Stalin. It was test-exploded on 29 August 1949, at Semipalatinsk, Kazakh SSR, after a top-secret R&D project...

" by the U.S.) in 1949, it caught Western analysts off guard, and President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

ordered a crash program to develop a hydrogen bomb in early 1950. Many scientists returned to Los Alamos to work on the "Super" program, but the initial attempts still seemed highly unworkable. In the "classical Super", it was thought that the heat alone from the fission bomb would be used to ignite the fusion material, but this proved to be impossible. For a while, many scientists thought (and many hoped) that the weapon itself would be impossible to construct.

Ulam's and Teller's contributions

The exact history of the Teller-Ulam breakthrough is not completely known, due in part to numerous conflicting personal accounts and continued classification of documents which would reveal which was closer to the truth. Previous models of the "Super" had apparently placed the fusion fuel either surrounding the fission "trigger" (in a spherical formation) or at the heart of it (similar to a "boosted" weapon) in the hopes that the closer the fuel was to the fission explosion, the higher the chance it would ignite the fusion fuel by the sheer force of the heat generated.In 1951, after still many years of fruitless labor on the "Super", an innovative idea from the Polish émigré mathematician Stanisław Ulam was seized upon by Teller and developed into the first workable design for a megaton-range hydrogen bomb. The exact amount of contribution provided respectively from Ulam and Teller to what became known as the "Teller-Ulam design" is not decidedly known in the public domain—the degree of credit assigned to Teller by his contemporaries is almost exactly commensurate with how well they thought of Teller in general. In an interview with Scientific American

Scientific American

Scientific American is a popular science magazine. It is notable for its long history of presenting science monthly to an educated but not necessarily scientific public, through its careful attention to the clarity of its text as well as the quality of its specially commissioned color graphics...

from 1999, Teller told the reporter:

I contributed; Ulam did not. I'm sorry I had to answer it in this abrupt way. Ulam was rightly dissatisfied with an old approach. He came to me with a part of an idea which I already had worked out and difficulty getting people to listen to. He was willing to sign a paper. When it then came to defending that paper and really putting work into it, he refused. He said, "I don't believe in it."

Genius

Genius is something or someone embodying exceptional intellectual ability, creativity, or originality, typically to a degree that is associated with the achievement of unprecedented insight....

" in the invention of the H-bomb as early as 1954. And as late as 1997 Bethe repeated his view that “the crucial invention was made in 1951, by Teller.” Other scientists (antagonistic to Teller, such as J. Carson Mark

J. Carson Mark

J. Carson Mark was a Canadian-born American mathematician known especially for his work on developing nuclear weapons for the United States at Los Alamos National Laboratory.-Biography:...

) have claimed that Teller would have never gotten any closer without the idea of Ulam.

Shock Waves

Shock Waves, , is a 1977 horror movie written and directed by Ken Wiederhorn...

generated by the primary, and that it was Teller who then realized that the radiation

Radiation

In physics, radiation is a process in which energetic particles or energetic waves travel through a medium or space. There are two distinct types of radiation; ionizing and non-ionizing...

from the primary would be able to accomplish the job (hence, "radiation implosion

Radiation implosion

The term radiation implosion describes the process behind a class of devices which use high levels of electromagnetic radiation to compress a target...

"). But compression alone would not have been enough and the other crucial idea—staging the bomb by separating the primary and secondary—seems to have been exclusively contributed by Ulam. The elegance of the design impressed many scientists, to the point that some who previously wondered if it were feasible suddenly believed it was inevitable, and that it would be created by both the USA and USSR. Even Oppenheimer, who was originally opposed to the project, called the idea "technically sweet". The "George" shot of Operation Greenhouse

Operation Greenhouse

Operation Greenhouse was the fifth American nuclear test series, the second conducted in 1951 and the first to test principles that would lead to developing thermonuclear weapons . Conducted at the new Pacific Proving Ground, all of the devices were mounted in large steel towers, to simulate air...

in 1951 tested the basic concept for the first time on a very small scale (and the next shot in the series, "Item", was the first boosted fission weapon

Boosted fission weapon

A boosted fission weapon usually refers to a type of nuclear bomb that uses a small amount of fusion fuel to increase the rate, and thus yield, of a fission reaction. The neutrons released by the fusion reactions add to the neutrons released in the fission, as well as inducing the fission reactions...

), raising expectations to a near certainty that the concept would work.

On November 1, 1952, the Teller-Ulam configuration was tested in the "Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first United States test of a thermonuclear weapon, in which a major part of the explosive yield came from nuclear fusion. It was detonated on November 1, 1952 by the United States at on Enewetak, an atoll in the Pacific Ocean, as part of Operation Ivy...

" shot at an island in the Enewetak

Enewetak

Enewetak Atoll is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its land area totals less than , surrounding a deep central lagoon, in circumference...

atoll, with a yield of 10.4 megatons

TNT equivalent

TNT equivalent is a method of quantifying the energy released in explosions. The ton of TNT is a unit of energy equal to 4.184 gigajoules, which is approximately the amount of energy released in the detonation of one ton of TNT...

(over 450 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki during World War II). The device, dubbed the Sausage, used an extra-large fission bomb as a "trigger" and liquid deuterium

Deuterium

Deuterium, also called heavy hydrogen, is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen. It has a natural abundance in Earth's oceans of about one atom in of hydrogen . Deuterium accounts for approximately 0.0156% of all naturally occurring hydrogen in Earth's oceans, while the most common isotope ...

—kept in its liquid state by 20 tons of cryogenic equipment—as its fusion fuel, and weighed around 80 tons altogether. Though an initial press blackout was attempted, it was soon announced that the U.S. had detonated a megaton-range hydrogen bomb.

The elaborate refrigeration plant necessary to keep its fusion fuel in a liquid state meant that the "Ivy Mike" device was too heavy and too complex to be of practical use. The first deployable Teller-Ulam weapon in the U.S. would not be developed until 1954, when the liquid deuterium

Deuterium

Deuterium, also called heavy hydrogen, is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen. It has a natural abundance in Earth's oceans of about one atom in of hydrogen . Deuterium accounts for approximately 0.0156% of all naturally occurring hydrogen in Earth's oceans, while the most common isotope ...

fuel of the "Ivy Mike" device would be replaced with a dry fuel of lithium deuteride and tested in the "Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the code name given to the first U.S. test of a dry fuel thermonuclear hydrogen bomb device, detonated on March 1, 1954 at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as the first test of Operation Castle. Castle Bravo was the most powerful nuclear device ever detonated by the United States ,...

" shot (the device was code-named the Shrimp). The dry lithium mixture performed much better than it was expected to, and the "Castle Bravo" device detonated in 1954 had a yield some two and a half times greater than expected (at 15 Mt, it was also the largest weapon ever detonated by the United States). Because much of the yield came from the final fission stage of its uranium tamper, it generated much nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout

Fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and shock wave have passed. It commonly refers to the radioactive dust and ash created when a nuclear weapon explodes...

, which caused one of the worst nuclear accidents in U.S. history when unforeseen weather patterns blew it over populated areas of the atoll and Japanese fishermen onboard the Daigo Fukuryu Maru

Daigo Fukuryu Maru

was a Japanese tuna fishing boat, which was exposed to and contaminated by nuclear fallout from the United States' Castle Bravo thermonuclear device test on Bikini Atoll, on 1 March 1954....

.

After an initial period focused on making multi-megaton hydrogen bombs, efforts in the United States shifted towards developing miniaturized Teller-Ulam weapons which could outfit Intercontinental Ballistic Missile

Intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile is a ballistic missile with a long range typically designed for nuclear weapons delivery...

s and Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles. The last major design breakthrough in this respect was accomplished by the mid-1970s, when versions of the Teller-Ulam design were created which could fit on the end of a small MIRVed missile.

Soviet developments

In the Soviet UnionSoviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, the scientists working on their own hydrogen bomb project

Soviet atomic bomb project

The Soviet project to develop an atomic bomb , was a clandestine research and development program began during and post-World War II, in the wake of the Soviet Union's discovery of the United States' nuclear project...

also ran into difficulties in developing a megaton-range fusion weapon. Because Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II...

had only been at Los Alamos at a very early stage of the hydrogen bomb design (before the Teller-Ulam configuration had been completed), none of his espionage information was of much use, and the Soviet physicists working on the project had to develop their weapon independently.

The first Soviet fusion design, developed by Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident and human rights activist. He earned renown as the designer of the Soviet Union's Third Idea, a codename for Soviet development of thermonuclear weapons. Sakharov was an advocate of civil liberties and civil reforms in the...

and Vitaly Ginzburg

Vitaly Ginzburg

Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg ForMemRS was a Soviet theoretical physicist, astrophysicist, Nobel laureate, a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and one of the fathers of Soviet hydrogen bomb...

in 1949 (before the Soviets had a working fission bomb), was dubbed the Sloika, after a Russian layered puff pastry, and was not of the Teller-Ulam configuration, but rather used alternating layers of fissile material and lithium deuteride fusion fuel spiked with tritium

Tritium

Tritium is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. The nucleus of tritium contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of protium contains one proton and no neutrons...

(this was later dubbed Sakharov's "First Idea"). Though nuclear fusion was technically achieved, it did not have the scaling property of a "staged" weapon, and their first "hydrogen bomb" test, "Joe 4

Joe 4

Joe 4 was an American nickname for the first Soviet test of a thermonuclear weapon on August 12, 1953. It utilized a scheme in which fission and fusion fuel were "layered", a design known as the Sloika model in the Soviet Union...

" is not generally considered to be a "true" hydrogen bomb, and is rather considered a hybrid fission/fusion device more similar to a large boosted fission weapon

Boosted fission weapon

A boosted fission weapon usually refers to a type of nuclear bomb that uses a small amount of fusion fuel to increase the rate, and thus yield, of a fission reaction. The neutrons released by the fusion reactions add to the neutrons released in the fission, as well as inducing the fission reactions...

than a Teller-Ulam weapon (though using an order of magnitude more fusion fuel than a boosted weapon). Detonated in 1953 with a yield equivalent to 400 kilotons of TNT

TNT equivalent

TNT equivalent is a method of quantifying the energy released in explosions. The ton of TNT is a unit of energy equal to 4.184 gigajoules, which is approximately the amount of energy released in the detonation of one ton of TNT...

(only 15%–20% from fusion), the Sloika device did, however, have the advantage of being a weapon which could actually be delivered to a military target, unlike the "Ivy Mike" device, though it was never widely deployed. Teller had proposed a similar design as early as 1946, dubbed the "Alarm Clock" (meant to "wake up" research into the "Super"), though it was calculated to be ultimately not worth the effort and no prototype was ever developed or tested.

Tritium

Tritium is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. The nucleus of tritium contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of protium contains one proton and no neutrons...

. In late 1953, physicist Viktor Davidenko achieved the first breakthrough, that of keeping the primary and secondary parts of the bombs in separate pieces ("staging"). The next breakthrough was discovered and developed by Sakharov and Yakov Zeldovich

Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich

Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich was a prolific Soviet physicist born in Belarus. He played an important role in the development of Soviet nuclear and thermonuclear weapons, and made important contributions to the fields of adsorption and catalysis, shock waves, nuclear physics, particle physics,...

, that of using the X-ray

X-ray

X-radiation is a form of electromagnetic radiation. X-rays have a wavelength in the range of 0.01 to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30 petahertz to 30 exahertz and energies in the range 120 eV to 120 keV. They are shorter in wavelength than UV rays and longer than gamma...

s from the fission bomb to compress the secondary before fusion ("radiation implosion"), in the spring of 1954. Sakharov's "Third Idea", as the Teller-Ulam design was known in the USSR, was tested in the shot "RDS-37

RDS-37

RDS-37 was the Soviet Union's first "true" hydrogen bomb, first tested on November 22, 1955. The weapon had a nominal yield of approximately 3 megatons. It was scaled down to 1.6 megatons for the live test....

" in November 1955 with a yield of 1.6 Mt.

If the Russians had been able to analyze the fallout data from either the "Ivy Mike" or "Castle Bravo" tests, they would have potentially been able to discern that the fission primary was being kept separate from the fusion secondary, a key part of the Teller-Ulam device, and potentially that the fusion fuel had been subjected to high amounts of compression before detonation. (De Geer 1991) One of the key Soviet bomb designers, Yuli Khariton, later said that:

At that time, Soviet research was not organized on a sufficiently high level, and useful results were not obtained, although radiochemical analyses of samples of fallout could have provided some useful information about the materials used to produce the explosion. The relationship between certain short-lived isotopes formed in the course of thermonuclear reactions could have made it possible to judge the degree of compression of the thermonuclear fuel, but knowing the degree of compression would not have allowed Soviet scientists to conclude exactly how the exploded device had been made, and it would not have revealed its design.

Snow

Snow is a form of precipitation within the Earth's atmosphere in the form of crystalline water ice, consisting of a multitude of snowflakes that fall from clouds. Since snow is composed of small ice particles, it is a granular material. It has an open and therefore soft structure, unless packed by...

in cardboard boxes several days after the "Mike" test with the hope of analyzing them for information, a chemist at Arzamas-16 (the Soviet weapons laboratory) had mistakenly poured the concentrate down the drain before it could be analyzed. Only in the fall of 1952 did the Soviet Union set up an organized system for monitoring fallout data.

The Soviets demonstrated the power of the "staging" concept in October 1961 when they detonated the massive and unwieldy Tsar Bomba

Tsar Bomba

Tsar Bomba is the nickname for the AN602 hydrogen bomb, the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated. It was also referred to as Kuz'kina Mat , in this usage meaning "something that has not been seen before"....

, a 50 Mt hydrogen bomb which derived almost 97% of its energy from fusion rather than fission—its uranium tamper was replaced with one of lead shortly before firing, in an effort to prevent excessive nuclear fallout. Had it been fired in its "full" form, it would have yielded at around 100 Mt of TNT. The weapon was technically deployable (it was tested by dropping it from a specially modified bomber), but militarily impractical, and was developed and tested primarily as a show of Soviet strength. It was the largest nuclear weapon developed and tested by any country.

Other countries

The details of the development of the Teller-Ulam design in other countries are less well known. In any event, United Kingdom had initial difficulty in its development of it, failing in its first attempt in May 1957 (its "Grapple IOperation Grapple

Operation Grapple, and operations Grapple X, Grapple Y and Grapple Z, were the names of British nuclear tests of the hydrogen bomb. They were held 1956—1958 at Malden Island and Christmas Island in the central Pacific Ocean. Nine nuclear detonations took place during the trials, resulting in...

" test failed to ignite as planned, though much of its energy did come from fusion in its secondary), though succeeded in its second attempt in its November 1957 "Grapple X

Operation Grapple

Operation Grapple, and operations Grapple X, Grapple Y and Grapple Z, were the names of British nuclear tests of the hydrogen bomb. They were held 1956—1958 at Malden Island and Christmas Island in the central Pacific Ocean. Nine nuclear detonations took place during the trials, resulting in...

" test (which yielded 1.8 Mt). The British development of the Teller-Ulam design was apparently independent, though they were allowed to share in some U.S. fallout data which may have been useful to them. After their successful detonation of a megaton-range device (and thus their practical understanding of the Teller-Ulam design "secret"), the United States agreed to exchange some of its nuclear designs with Great Britain, leading to the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

The 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement is a bilateral treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom on nuclear weapons cooperation.It was signed after the UK successfully tested its first hydrogen bomb during Operation Grapple. While the U.S...

.

The People's Republic of China detonated its first device using a Teller-Ulam design June 1967 ("Test No. 6"), a mere 32 months after detonating its first fission weapon (the shortest fission-to-fusion development yet known), with a yield of 3.3 Mt. Little is known about the Chinese thermonuclear program, however. Very little is known about the French development of the Teller-Ulam design beyond the fact that they detonated a 2.6 Mt device in the "Canopus

Canopus (nuclear test)

Canopus was the code name for France's first two-stage thermonuclear test, conducted on August 24, 1968 at Fangataufa atoll...

" test in August 1968. In 1998, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

claimed to detonate a "hydrogen bomb" in its Operation Shakti tests ("Shakti I", specifically), though seismographic readings have led many non-Indian experts to conclude that this is unlikely, or at least it was unlikely to have been a success as claimed, because of its low yield (claimed to be around 45 kt, though outside experts estimate it at around 30 kt, both extremely low for a successful thermonuclear detonation). However even low-yield tests can have a bearing on thermonuclear capability, as they can provide information on the behavior of primaries without the full ignition of secondaries.

Public knowledge

Classified information

Classified information is sensitive information to which access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of persons. A formal security clearance is required to handle classified documents or access classified data. The clearance process requires a satisfactory background investigation...

. United States Department of Energy

United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy is a Cabinet-level department of the United States government concerned with the United States' policies regarding energy and safety in handling nuclear material...

(DOE) policy has been, and continues to be, that they do not acknowledge when "leaks" occur, because doing such would acknowledge the accuracy of the supposed leaked information. Aside from images of the warhead casing (but never of the "physics package" itself), most information in the public domain about this design is regulated to a few terse statements by the DOE and the work of a few individual investigators.

Below is a short discussion of the events which lead to the formation of these "public" models of the Teller-Ulam design, with some discussions as to their differences and disagreements with those principles outlined above.

DOE statements

In 1972, the DOE declassified a statement that "The fact that in thermonuclear (TN) weapons, a fission 'primary' is used to trigger a TN reaction in thermonuclear fuel referred to as a 'secondary'", and in 1979 added: "The fact that, in thermonuclear weapons, radiation from a fission explosive can be contained and used to transfer energy to compress and ignite a physically separate component containing thermonuclear fuel." To this latter sentence they specified that "Any elaboration of this statement will be classified." (emphasis in original) The only statement which may pertain to the sparkplug was declassified in 1991, "Fact that fissile and/or fissionable materials are present in some secondaries, material unidentified, location unspecified, use unspecified, and weapons undesignated." In 1998, the DOE declassified the statement that "The fact that materials may be present in channels and the term 'channel filler,' with no elaboration", which may refer to the polystyrene foam (or an analogous substance). (DOE 2001, sect. V.C.)Whether these statements vindicate some or all of the models presented above is up for interpretation, and official U.S. government releases about the technical details of nuclear weapons have been purposely equivocating in the past (i.e. Smyth Report

Smyth Report

The Smyth Report was the common name given to an administrative history written by physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth about the Allied World War II effort to develop the atomic bomb, the Manhattan Project...

). Other information, such as the types of fuel used in some of the early weapons, has been declassified, though of course precise technical information has not been.

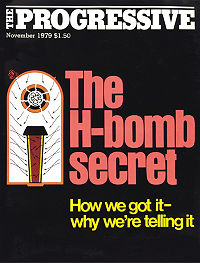

The Progressive case

Prior restraint

Prior restraint or prior censorship is censorship in which certain material may not be published or communicated, rather than not prohibiting publication but making the publisher answerable for what is made known...

a magazine article by U.S. antiweapons activist Howard Morland

Howard Morland

Howard Morland is a United States journalist and activist against nuclear weapons who in 1979 became famous for apparently discovering the "secret" of the hydrogen bomb and publishing it after a lengthy censorship attempt by the Department of Energy...

in 1979 on the "secret of the hydrogen bomb". In 1978, Morland had decided that discovering and exposing this "last remaining secret" would focus attention onto the arms race

Arms race

The term arms race, in its original usage, describes a competition between two or more parties for the best armed forces. Each party competes to produce larger numbers of weapons, greater armies, or superior military technology in a technological escalation...

and allow citizens to feel empowered to question official statements on the importance of nuclear weapons and nuclear secrecy. Most of Morland's ideas about how the weapon worked were compiled from highly accessible sources—the drawings which most inspired his approach came from none other than the Encyclopedia Americana

Encyclopedia Americana

Encyclopedia Americana is one of the largest general encyclopedias in the English language. Following the acquisition of Grolier in 2000, the encyclopedia has been produced by Scholastic....

. Morland also interviewed (often informally) many former Los Alamos

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

scientists (including Teller and Ulam, though neither gave him any useful information), and used a variety of interpersonal strategies to encourage informational responses from them (i.e., asking questions such as "Do they still use sparkplugs?" even if he wasn't aware what the latter term specifically referred to). (Morland 1981)

Morland eventually concluded that the "secret" was that the primary and secondary were kept separate and that radiation pressure

Radiation pressure

Radiation pressure is the pressure exerted upon any surface exposed to electromagnetic radiation. If absorbed, the pressure is the power flux density divided by the speed of light...

from the primary compressed the secondary before igniting it. When an early draft of the article, to be published in The Progressive

The Progressive

The Progressive is an American monthly magazine of politics, culture and progressivism with a pronounced liberal perspective on some issues. Known for its pacifism, it has strongly opposed military interventions, such as the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. The magazine also devotes much coverage...

magazine, was sent to the DOE after falling into the hands of a professor who was opposed to Morland's goal, the DOE requested that the article not be published, and pressed for a temporary injunction. After a short court hearing in which the DOE argued that Morland's information was 1. likely derived from classified sources, 2. if not derived from classified sources, itself counted as "secret" information under the "born secret

Born secret

"Born secret" and "born classified" are both terms which refer to a policy of information being classified from the moment of its inception, usually regardless of where it was being created, usually in reference to specific laws in the United States that are related to information that describes...

" clause of the 1954 Atomic Energy Act, and 3. was dangerous and would encourage nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is a term now used to describe the spread of nuclear weapons, fissile material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information, to nations which are not recognized as "Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the...

. Morland and his lawyers disagreed on all points, but the injunction was granted, as the judge in the case felt that it was safer to grant the injunction and allow Morland, et al., to appeal, which they did in United States v. The Progressive, et al. (1979).

.jpg)

Chuck Hansen

Chuck Hansen compiled, over a period of 30 years, the world's largest private collection of documents on how America developed the atomic bomb. These documents were obtained through the U.S...

, had his own ideas about the "secret" (quite different from Morland's) published in a Wisconsin newspaper, the DOE claimed The Progressive case was moot, dropped their suit and allowed the magazine to publish, which it did in November 1979. Morland had by then, however, changed his opinion of how the bomb worked, suggesting that a foam medium (the polystyrene) rather than radiation pressure was used to compress the secondary, and that in the secondary was a sparkplug of fissile material as well. He published these changes, based in part on the proceedings of the appeals trial, as a short errata in The Progressive a month later. In 1981, Morland published a book, The secret that exploded, about his experience, describing in detail the train of thought which led him to his conclusions about the "secret".

Because the DOE sought to censor Morland's work—one of the few times they violated their usual approach of not acknowledging "secret" material which had been released—it is interpreted as being at least partially correct, though to what degree it lacks information or has incorrect information is not known with any great confidence. The difficulty which a number of nations had in developing the Teller-Ulam design (even when they apparently understood the design, such as with the United Kingdom), makes it somewhat unlikely that this simple information alone is what provides the ability to manufacture thermonuclear weapons. Nevertheless, the ideas put forward by Morland in 1979 have been the basis for all current speculation on the Teller-Ulam design.

See also

- Teller-Ulam designTeller-Ulam designThe Teller–Ulam design is the nuclear weapon design concept used in most of the world's nuclear weapons. It is colloquially referred to as "the secret of the hydrogen bomb" because it employs hydrogen fusion, though in most applications the bulk of its destructive energy comes from uranium fission,...

- Manhattan ProjectManhattan ProjectThe Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

- History of nuclear weaponsHistory of nuclear weaponsThe history of nuclear weapons chronicles the development of nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons possess enormous destructive potential derived from nuclear fission or nuclear fusion reactions...

- Nuclear weapons design

- Nuclear weaponNuclear weaponA nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

- Nuclear fusionNuclear fusionNuclear fusion is the process by which two or more atomic nuclei join together, or "fuse", to form a single heavier nucleus. This is usually accompanied by the release or absorption of large quantities of energy...

External links

- PBS: Race for the Superbomb: Interviews and Transcripts (with U.S. and USSR bomb designers as well as historians).

- Howard Morland on how he discovered the "H-bomb secret" (includes many slides).

- The Progressive November 1979 issue – "The H-Bomb Secret: How we got it, why we're telling" (entire issue online).