Charles Kay Ogden

Encyclopedia

Charles Kay Ogden was an English

linguist, philosopher, and writer. Described as a polymath

but also an eccentric

and outsider, he took part in many ventures related to literature, politics, the arts and philosophy, having a broad impact particularly as an editor, translator, and activist on behalf of a reformed version of the English language. He is typically defined as a linguistic psychologist, and is now mostly remembered as the inventor and propagator of Basic English

.

in Fleetwood

, Lancashire

on 1 June 1889, where his father Charles Burdett Ogden was a housemaster. He was educated at Buxton

and Rossall, winning a scholarship to Magdalene College, Cambridge

and coming up to read Classics in 1908.

, who advised him not to miss the opportunity. Shortly after, Stephen Swift & Co. went bankrupt. Ogden continued to edit the magazine during World War I, when its nature changed, because rheumatic fever

as a teenager had left him unfit for military service.

Ogden often used the pseudonym

Adelyne More (add-a-line more) in his journalism. The magazine included literary contributions by Siegfried Sassoon

, John Masefield

, Thomas Hardy

, George Bernard Shaw

, and Arnold Bennett

. In 1919 Claude McKay

was in London, and Ogden published his poetry in the Magazine.

It evolved into an organ of international comment on politics and the war, supported in the background by a group of Cambridge academics including Edward Dent (who sent Sassoon's work), Theo Bartholomew and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson

. A survey of the foreign press filled more than half of each issue, being the Notes from the foreign press supplied by Dorothy Buxton

which appeared there from October 1915 onwards until 1920, and its circulation rose to over 20,000. Buxton was in fact then leading a large team translating and collating articles from up to 100 foreign newspapers; for instance Italian articles were supplied in translation in numbers by Dent. This digest of European press coverage was exclusive to the Magazine, and gave it disproportionate influence in political circles. For example, Robert Reid, 1st Earl Loreburn

used the Notes from the foreign press to advocate to the Marquess of Lansdowne

in 1916 against bellicose claims and attitudes on the British side.

During 1917 the Magazine came under heavy criticism, with its neutral use of foreign press extracts being called pacifism

, particularly by the pro-war patriotic Fight for Right Movement headed by Francis Younghusband

. Dorothy Buxton's husband Charles Roden Buxton

was closely associated with the Union of Democratic Control

. Sir Frederick Pollock who chaired Fight for Right wrote to The Morning Post in February 1917 charging the Magazine with pacifist propaganda, and with playing on its connection with the University as if it had official status. Gilbert Murray

, a supporter of Fight for Right but also a defender of many conscientious objectors and the freedom of the press

, intervened to protest, gaining support from Bennett and Hardy. John George Butcher, Conservative Member of Parliament for the City of York

, asked a question in Parliament about government advertising in the Magazine, during November 1917. The parliamentary exchange had two Liberal Party politicians, William Pringle

and Josiah Wedgwood

, pointing out that the Magazine was the only way they could read German press comments.

The Cambridge Magazine continued in the post-war years, but wound down to quarterly publication before closing down in 1922.

, Master of Emmanuel College

, a past Vice-Chancellor. The Heretics began as a group of 12 undergraduates interested in Chawner's agnostic approach.

The Society was nonconformist and open to women, and Jane Harrison

found an audience there, publishing her inaugural talk for the Society of 7 December 1909 as the essay Heresy and Humanity (1911), an argument against individualism

. The talk of the following day was from J. M. E. McTaggart

, and was also published, as Dare to Be Wise (1910). Another early member with anthropological interests was John Layard

; Herbert Felix Jolowicz, Frank Plumpton Ramsey and Philip Sargant Florence were among the members. Alix Sargant Florence, sister of Philip, was active both as a Heretic and on the editorial board of the Cambridge Magazine.

Ogden was President of the Heretics from 1911, for more than a decade; he invited a variety of prominent speakers and linked the Society to his role as editor. In November 1911 G. K. Chesterton

used a well-publicised talk to the Heretics to reply to George Bernard Shaw

who had recently talked on The Future of Religion. On this occasion Chesterton produced one of his well-known bon mots:

In 1912 T. E. Hulme

and Bertrand Russell

spoke. Hulme's talk on Anti-Romanticism and Original Sin was written up by Ogden for the Cambridge Magazine, where in 1916 both Hulme and Russell would write on the war, from their opposite points of view. Rupert Brooke

addressed them on contemporary theatre, and an article based on his views of Strindberg

appeared in the Cambridge Magazine in October 1913. Another talk from 1913 that was published was from Edward Clodd

on Obscurantism in Modern Science. Ogden was very active at this period in seeing these works into print.

The Heretics continued as a well-known forum, with Virginia Woolf

in May 1924 using it to formulate a reply to criticisms from Arnold Bennett arising from her Jacob's Room

(1922), in a talk Character in Fiction that was then published in The Criterion. This paper contains the assertion, now proverbial, that "on or about December 1910 human character changed." The Heretics met in November 1929, when Ludwig Wittgenstein

lectured to it on ethics, at Ogden's invitation, producing in A Lecture on Ethics a work accepted as part of the early Wittgenstein canon.

, and concerned industrial training; he made also a translation of a related work of Georg Kerchensteiner (who had introduced him to Best), appearing as The Schools and the Nation (1914). Militarism versus Feminism (1915, anonymous) was with Mary Sargant Florence

(mother of Alix); and Uncontrolled Breeding: Fecundity versus Civilization (1916), was a tract in favour of birth control

, under the Adelyne More pseudonym.

Ogden ran a network of bookshops in Cambridge, selling also art by the Bloomsbury Group

. One such bookshop was looted on the day World War I ended.

Also for Kegan Paul he founded and edited what became five separate series of books, comprising hundreds of titles. Two were major series of monographs, "The History of Civilisation" and "The International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method

"; the latter series included about 100 volumes after one decade. The "To-day and To-morrow

" series was another extensive series running to about 150 volumes, of popular books in essay form with provocative titles; he edited it from its launch in 1924. The first of the series (after an intervention by Fredric Warburg

) was Daedalus; or, Science and the Future

by J. B. S. Haldane

, an extended version of a talk to the Heretics Society. Other series were "Science for You" and "Psyche Miniatures".

Ogden helped with the English translation of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Ogden helped with the English translation of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

. In fact the translation itself was the work of F. P. Ramsey; Ogden as a commissioning editor assigned the task of translation to Ramsey, supposedly on earlier experience of Ramsey's insight into another German text, of Ernst Mach

. The Latinate title now given to the work in English, with its nod to Baruch Spinoza

's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, is attributed to G. E. Moore, and was adopted by Ogden. In 1973 Georg Henrik von Wright

edited Wittgenstein's Letters to C.K. Ogden with Comments on the English Translation of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, including correspondence with Ramsey.

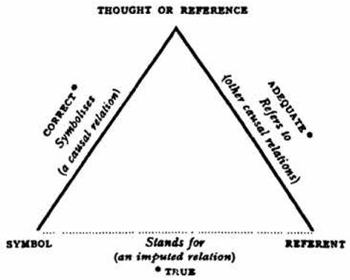

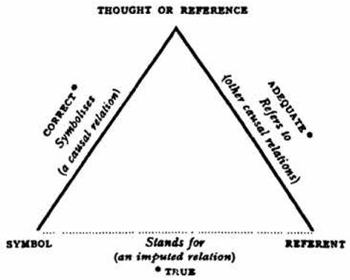

His most durable work is his monograph (with I. A. Richards

) titled The Meaning of Meaning

(1923), which went into many editions. This book, which straddled the boundaries among linguistics, literary analysis, and philosophy, drew attention to the significs

of Victoria Lady Welby (whose disciple Ogden was) and the semiotics

of Charles Sanders Peirce. A major step in the "linguistic turn" of 20th century British philosophy, The Meaning of Meaning set out principles for understanding the function of language and described the so-called semantic triangle. It included the inimitable phrase "The gostak

distims the doshes."

Although neither a trained philosopher nor an academic, Ogden had a material effect on British academic philosophy. The Meaning of Meaning enunciated a theory of emotivism

. Ogden went on to edit as Bentham's Theory of Fictions (1932) a work of Jeremy Bentham

, and had already translated in 1911 as The Philosophy of ‘As If’ a work of Hans Vaihinger

, both of which are regarded as precursors of the modern theory of fictionalism

.

in Cambridge. From 1928 to 1930 Ogden set out his developing ideas on Basic English and Jeremy Bentham in Psyche.

In 1929 the Institute published a recording by James Joyce

of a passage from a draft of Finnegans Wake

. In summer of that year Tales Told of Shem and Shaun had been published, an extract from the work as it then stood, and Ogden had been asked to supply an introduction. When Joyce was in London in August, Ogden approached him to do a reading for a recording. In 1932 Ogden published a translation of the Finnegans Wake passage into Basic English.

By 1943 the Institute had moved to Gordon Square

in London.

Ogden was also a consultant with the International Auxiliary Language Association

, which presented Interlingua

in 1951.

collection were purchased by University College London

. The balance of his enormous personal library was purchased after his death by the University of California - Los Angeles. He died on 21 March 1957 in London.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

linguist, philosopher, and writer. Described as a polymath

Polymath

A polymath is a person whose expertise spans a significant number of different subject areas. In less formal terms, a polymath may simply be someone who is very knowledgeable...

but also an eccentric

Eccentricity (behavior)

In popular usage, eccentricity refers to unusual or odd behavior on the part of an individual. This behavior would typically be perceived as unusual or unnecessary, without being demonstrably maladaptive...

and outsider, he took part in many ventures related to literature, politics, the arts and philosophy, having a broad impact particularly as an editor, translator, and activist on behalf of a reformed version of the English language. He is typically defined as a linguistic psychologist, and is now mostly remembered as the inventor and propagator of Basic English

Basic English

Basic English, also known as Simple English, is an English-based controlled language created by linguist and philosopher Charles Kay Ogden as an international auxiliary language, and as an aid for teaching English as a Second Language...

.

Early life

He was born at Rossall SchoolRossall School

Rossall School is a British, co-educational, independent school, between Cleveleys and Fleetwood, Lancashire. Rossall was founded in 1844 by St. Vincent Beechey as a sister school to Marlborough College which had been founded the previous year...

in Fleetwood

Fleetwood

Fleetwood is a town within the Wyre district of Lancashire, England, lying at the northwest corner of the Fylde. It had a population of 26,840 people at the 2001 Census. It forms part of the Greater Blackpool conurbation. The town was the first planned community of the Victorian era...

, Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

on 1 June 1889, where his father Charles Burdett Ogden was a housemaster. He was educated at Buxton

Buxton

Buxton is a spa town in Derbyshire, England. It has the highest elevation of any market town in England. Located close to the county boundary with Cheshire to the west and Staffordshire to the south, Buxton is described as "the gateway to the Peak District National Park"...

and Rossall, winning a scholarship to Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England.The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary Magdalene...

and coming up to read Classics in 1908.

At Cambridge

He visited continental Europe to investigate methods of language teaching in 1912 and 1913. Ogden obtained an M.A. in 1915.The Cambridge Magazine

He founded the weekly Cambridge Magazine in 1912 while still an undergraduate, editing it until it ceased publication in 1922. The initial period was troubled. Ogden was studying for Part II of the Classical Tripos when offered the chance to start the magazine by Charles Granville, who ran a small but significant London publishing house, Stephen Swift & Co. Thinking that the editorship would mean giving up first class honours, Ogden consulted Henry JacksonHenry Jackson (classicist)

Henry Jackson, OM, , was an English classicist. He served as the vice-master of Trinity College, Cambridge from 1914 to 1919, praelector in ancient philosophy from 1875 to 1906 and Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge from 1906 to 1921, and was awarded the Order of Merit on 26...

, who advised him not to miss the opportunity. Shortly after, Stephen Swift & Co. went bankrupt. Ogden continued to edit the magazine during World War I, when its nature changed, because rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that occurs following a Streptococcus pyogenes infection, such as strep throat or scarlet fever. Believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain, the illness typically develops two to three weeks after...

as a teenager had left him unfit for military service.

Ogden often used the pseudonym

Pseudonym

A pseudonym is a name that a person assumes for a particular purpose and that differs from his or her original orthonym...

Adelyne More (add-a-line more) in his journalism. The magazine included literary contributions by Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon CBE MC was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's...

, John Masefield

John Masefield

John Edward Masefield, OM, was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1930 until his death in 1967...

, Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy, OM was an English novelist and poet. While his works typically belong to the Naturalism movement, several poems display elements of the previous Romantic and Enlightenment periods of literature, such as his fascination with the supernatural.While he regarded himself primarily as a...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

, and Arnold Bennett

Arnold Bennett

- Early life :Bennett was born in a modest house in Hanley in the Potteries district of Staffordshire. Hanley is one of a conurbation of six towns which joined together at the beginning of the twentieth century as Stoke-on-Trent. Enoch Bennett, his father, qualified as a solicitor in 1876, and the...

. In 1919 Claude McKay

Claude McKay

Claude McKay was a Jamaican-American writer and poet. He was a seminal figure in the Harlem Renaissance and wrote three novels: Home to Harlem , a best-seller which won the Harmon Gold Award for Literature, Banjo , and Banana Bottom...

was in London, and Ogden published his poetry in the Magazine.

It evolved into an organ of international comment on politics and the war, supported in the background by a group of Cambridge academics including Edward Dent (who sent Sassoon's work), Theo Bartholomew and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson , was a British historian and political activist. He led most of his life at Cambridge, where he wrote a dissertation on Neoplatonism before becoming a fellow. He was closely associated with the Bloomsbury Group.A noted pacifist, Dickinson protested against Britain's...

. A survey of the foreign press filled more than half of each issue, being the Notes from the foreign press supplied by Dorothy Buxton

Dorothy Buxton

Dorothy Frances Buxton, née Jebb was an English humanitarian, social activist and commentator on Germany.-Life:...

which appeared there from October 1915 onwards until 1920, and its circulation rose to over 20,000. Buxton was in fact then leading a large team translating and collating articles from up to 100 foreign newspapers; for instance Italian articles were supplied in translation in numbers by Dent. This digest of European press coverage was exclusive to the Magazine, and gave it disproportionate influence in political circles. For example, Robert Reid, 1st Earl Loreburn

Robert Reid, 1st Earl Loreburn

Robert Threshie Reid, 1st Earl Loreburn GCMG, PC, QC was a British lawyer, judge and Liberal politician. He served as Lord Chancellor between 1905 and 1912.-Background and education:...

used the Notes from the foreign press to advocate to the Marquess of Lansdowne

Henry Petty-FitzMaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne

Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, KG, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, PC was a British politician and Irish peer who served successively as the fifth Governor General of Canada, Viceroy of India, Secretary of State for War, and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs...

in 1916 against bellicose claims and attitudes on the British side.

During 1917 the Magazine came under heavy criticism, with its neutral use of foreign press extracts being called pacifism

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

, particularly by the pro-war patriotic Fight for Right Movement headed by Francis Younghusband

Francis Younghusband

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Edward Younghusband, KCSI, KCIE was a British Army officer, explorer, and spiritual writer...

. Dorothy Buxton's husband Charles Roden Buxton

Charles Roden Buxton

Charles Roden Buxton was an English philanthropist and politician.He was born in London, the third son of Sir Thomas Buxton, 3rd Baronet...

was closely associated with the Union of Democratic Control

Union of Democratic Control

The Union of Democratic Control was a British pressure group formed in 1914 to press for a more responsive foreign policy. While not a pacifist organization, it was opposed to military influence in government.-World War I:...

. Sir Frederick Pollock who chaired Fight for Right wrote to The Morning Post in February 1917 charging the Magazine with pacifist propaganda, and with playing on its connection with the University as if it had official status. Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray

George Gilbert Aimé Murray, OM was an Australian born British classical scholar and public intellectual, with connections in many spheres. He was an outstanding scholar of the language and culture of Ancient Greece, perhaps the leading authority in the first half of the twentieth century...

, a supporter of Fight for Right but also a defender of many conscientious objectors and the freedom of the press

Freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the freedom of communication and expression through vehicles including various electronic media and published materials...

, intervened to protest, gaining support from Bennett and Hardy. John George Butcher, Conservative Member of Parliament for the City of York

City of York (UK Parliament constituency)

The City of York was a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elected one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election.-Boundaries:...

, asked a question in Parliament about government advertising in the Magazine, during November 1917. The parliamentary exchange had two Liberal Party politicians, William Pringle

William Pringle (Liberal politician)

William Mather Rutherford Pringle was a Liberal Party politician in the United Kingdom who served as a Member of Parliament from 1910 to 1918 and again from 1922 to 1924....

and Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood, 1st Baron Wedgwood

Colonel Josiah Clement Wedgwood, 1st Baron Wedgwood, DSO, PC, DL sometimes referred to as Josiah Wedgwood IV was a British Liberal and Labour politician who served in government under Ramsay MacDonald...

, pointing out that the Magazine was the only way they could read German press comments.

The Cambridge Magazine continued in the post-war years, but wound down to quarterly publication before closing down in 1922.

The Heretics Society

Ogden also co-founded the Heretics Society in Cambridge in 1909, which questioned traditional authorities in general and religious dogmas in particular, in the wake of the paper Prove All Things, read by William ChawnerWilliam Chawner

William Chawner was an educational reformer and the first layman to be appointed as Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge.-Life:...

, Master of Emmanuel College

Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay on the site of a Dominican friary...

, a past Vice-Chancellor. The Heretics began as a group of 12 undergraduates interested in Chawner's agnostic approach.

The Society was nonconformist and open to women, and Jane Harrison

Jane Ellen Harrison

Jane Ellen Harrison was a British classical scholar, linguist and feminist. Harrison is one of the founders, with Karl Kerenyi and Walter Burkert, of modern studies in Greek mythology. She applied 19th century archaeological discoveries to the interpretation of Greek religion in ways that have...

found an audience there, publishing her inaugural talk for the Society of 7 December 1909 as the essay Heresy and Humanity (1911), an argument against individualism

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that stresses "the moral worth of the individual". Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance while opposing most external interference upon one's own...

. The talk of the following day was from J. M. E. McTaggart

J. M. E. McTaggart

John McTaggart was an idealist metaphysician. For most of his life McTaggart was a fellow and lecturer in philosophy at Trinity College, Cambridge. He was an exponent of the philosophy of Hegel and among the most notable of the British idealists.-Personal life:J. M. E. McTaggart was born in 1866...

, and was also published, as Dare to Be Wise (1910). Another early member with anthropological interests was John Layard

John Layard

John Willoughby Layard was an English anthropologist and psychologist.- Early life :Layard was born in London, son of the essayist and literary writer George Somes Layard. He grew up first at Malvern, and in c 1902 moved to Bull's Cliff, Felixstowe. He was educated at Bedales School...

; Herbert Felix Jolowicz, Frank Plumpton Ramsey and Philip Sargant Florence were among the members. Alix Sargant Florence, sister of Philip, was active both as a Heretic and on the editorial board of the Cambridge Magazine.

Ogden was President of the Heretics from 1911, for more than a decade; he invited a variety of prominent speakers and linked the Society to his role as editor. In November 1911 G. K. Chesterton

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG was an English writer. His prolific and diverse output included philosophy, ontology, poetry, plays, journalism, public lectures and debates, literary and art criticism, biography, Christian apologetics, and fiction, including fantasy and detective fiction....

used a well-publicised talk to the Heretics to reply to George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

who had recently talked on The Future of Religion. On this occasion Chesterton produced one of his well-known bon mots:

- Questioner: ... I say it is perfectly true that I have an intuition that I exist.

- Mr. Chesterton: Cherish it.

In 1912 T. E. Hulme

T. E. Hulme

Thomas Ernest Hulme was an English critic and poet who, through his writings on art, literature and politics, had a notable influence upon modernism.-Early life:...

and Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these things...

spoke. Hulme's talk on Anti-Romanticism and Original Sin was written up by Ogden for the Cambridge Magazine, where in 1916 both Hulme and Russell would write on the war, from their opposite points of view. Rupert Brooke

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke was an English poet known for his idealistic war sonnets written during the First World War, especially The Soldier...

addressed them on contemporary theatre, and an article based on his views of Strindberg

Strindberg

Strindberg may refer to:People* August Strindberg , Swedish dramatist and painter* Nils Strindberg , Swedish photographer* Anita Strindberg , Swedish actor* Henrik Strindberg , Swedish composerOther...

appeared in the Cambridge Magazine in October 1913. Another talk from 1913 that was published was from Edward Clodd

Edward Clodd

Edward Clodd was an English banker, writer and anthropologist. He cultivated a very wide circle of literary and scientific friends, who periodically met at Whitsun gatherings at his home at Aldeburgh, Suffolk....

on Obscurantism in Modern Science. Ogden was very active at this period in seeing these works into print.

The Heretics continued as a well-known forum, with Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf was an English author, essayist, publisher, and writer of short stories, regarded as one of the foremost modernist literary figures of the twentieth century....

in May 1924 using it to formulate a reply to criticisms from Arnold Bennett arising from her Jacob's Room

Jacob's Room

Jacob's Room is the third novel by Virginia Woolf, first published on October 26th 1922.The novel centers, in a very ambiguous way, around the life story of the protagonist Jacob Flanders, and is presented entirely by the impressions other characters have of Jacob [except for those times when we do...

(1922), in a talk Character in Fiction that was then published in The Criterion. This paper contains the assertion, now proverbial, that "on or about December 1910 human character changed." The Heretics met in November 1929, when Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He was professor in philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1939 until 1947...

lectured to it on ethics, at Ogden's invitation, producing in A Lecture on Ethics a work accepted as part of the early Wittgenstein canon.

Author and bookseller

He authored three books in this period. One was The Problem of the Continuation School (1914), with Robert Hall Best of the Best & Lloyd lighting company of HandsworthHandsworth, West Midlands

Handsworth is an inner city area of Birmingham in the West Midlands, England. The Local Government Act 1894 divided the ancient Staffordshire parish of Handsworth into two urban districts: Handsworth and Perry Barr. Handsworth was annexed to the county borough of Birmingham in Warwickshire in 1911...

, and concerned industrial training; he made also a translation of a related work of Georg Kerchensteiner (who had introduced him to Best), appearing as The Schools and the Nation (1914). Militarism versus Feminism (1915, anonymous) was with Mary Sargant Florence

Mary Sargant Florence

Mary Sargant Florence was a British painter of figure subjects, mural decorations in fresco and occasional landscapes in watercolour and pastel. She was born in London, née Sargant, sister of the sculptor F.W. Sargant. She studied in Paris under Luc-Olivier Merson and at the Slade School under...

(mother of Alix); and Uncontrolled Breeding: Fecundity versus Civilization (1916), was a tract in favour of birth control

Birth control

Birth control is an umbrella term for several techniques and methods used to prevent fertilization or to interrupt pregnancy at various stages. Birth control techniques and methods include contraception , contragestion and abortion...

, under the Adelyne More pseudonym.

Ogden ran a network of bookshops in Cambridge, selling also art by the Bloomsbury Group

Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group or Bloomsbury Set was a group of writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists who held informal discussions in Bloomsbury throughout the 20th century. This English collective of friends and relatives lived, worked or studied near Bloomsbury in London during the first half...

. One such bookshop was looted on the day World War I ended.

The editor

He built up a position as editor for Kegan Paul, publishers in London. In 1920, he was one of the founders of the psychological journal Psyche, and later took over the editorship; Psyche was initially the Psychic Research Quarterly set up by Walter Whately Smith, but changed its name and editorial policy in 1921. It appeared until 1952, and was a vehicle for some of Ogden's interests.Also for Kegan Paul he founded and edited what became five separate series of books, comprising hundreds of titles. Two were major series of monographs, "The History of Civilisation" and "The International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method

The International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method

The International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method was an influential series of monographs published published 1910–1965 under the general editorship of Charles Kay Ogden. This series published some of the landmark works on psychology and philosophy, particularly the thought...

"; the latter series included about 100 volumes after one decade. The "To-day and To-morrow

To-day and To-morrow

To-day and To-morrow was a series of over 150 speculative essays published as short books by the London publishers Kegan Paul between 1923 and 1931 To-day and To-morrow (sometimes written Today and Tomorrow) was a series of over 150 speculative essays published as short books by the London...

" series was another extensive series running to about 150 volumes, of popular books in essay form with provocative titles; he edited it from its launch in 1924. The first of the series (after an intervention by Fredric Warburg

Fredric Warburg

Fredric John Warburg was an English publisher best known for his association with the British author George Orwell...

) was Daedalus; or, Science and the Future

Daedalus; or, Science and the Future

Daedalus; or, Science and the Future is a book by the British scientist J. B. S. Haldane, published in England in 1924. It was the text of a lecture read to the Heretics Society, an intellectual club at Cambridge University on 4 February 1923....

by J. B. S. Haldane

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane FRS , known as Jack , was a British-born geneticist and evolutionary biologist. A staunch Marxist, he was critical of Britain's role in the Suez Crisis, and chose to leave Oxford and moved to India and became an Indian citizen...

, an extended version of a talk to the Heretics Society. Other series were "Science for You" and "Psyche Miniatures".

Language and philosophy

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is the only book-length philosophical work published by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his lifetime. It was an ambitious project: to identify the relationship between language and reality and to define the limits of science...

. In fact the translation itself was the work of F. P. Ramsey; Ogden as a commissioning editor assigned the task of translation to Ramsey, supposedly on earlier experience of Ramsey's insight into another German text, of Ernst Mach

Ernst Mach

Ernst Mach was an Austrian physicist and philosopher, noted for his contributions to physics such as the Mach number and the study of shock waves...

. The Latinate title now given to the work in English, with its nod to Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch de Spinoza and later Benedict de Spinoza was a Dutch Jewish philosopher. Revealing considerable scientific aptitude, the breadth and importance of Spinoza's work was not fully realized until years after his death...

's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, is attributed to G. E. Moore, and was adopted by Ogden. In 1973 Georg Henrik von Wright

Georg Henrik von Wright

Georg Henrik von Wright was a Finnish philosopher, who succeeded Ludwig Wittgenstein as professor at the University of Cambridge. He published in English, Finnish, German, and in Swedish. Belonging to the Swedish-speaking minority of Finland, von Wright also had Finnish and 17th-century Scottish...

edited Wittgenstein's Letters to C.K. Ogden with Comments on the English Translation of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, including correspondence with Ramsey.

His most durable work is his monograph (with I. A. Richards

I. A. Richards

Ivor Armstrong Richards was an influential English literary critic and rhetorician....

) titled The Meaning of Meaning

The Meaning of Meaning

Although the original text was published in 1923 it has been used as a textbook in many fields including linguistics, philosophy, language, cognitive science and most recently semantics. The book has been in print continuously since 1923. The most recent edition is the critical edition prepared...

(1923), which went into many editions. This book, which straddled the boundaries among linguistics, literary analysis, and philosophy, drew attention to the significs

Significs

Significs is a linguistic and philosophical term introduced by Victoria, Lady Welby in the 1890s. It was later adopted by the Dutch Significs Group of thinkers around Frederik van Eeden, which included L. E. J...

of Victoria Lady Welby (whose disciple Ogden was) and the semiotics

Semiotics

Semiotics, also called semiotic studies or semiology, is the study of signs and sign processes , indication, designation, likeness, analogy, metaphor, symbolism, signification, and communication...

of Charles Sanders Peirce. A major step in the "linguistic turn" of 20th century British philosophy, The Meaning of Meaning set out principles for understanding the function of language and described the so-called semantic triangle. It included the inimitable phrase "The gostak

Gostak

Gostak is a meaningless noun that is used in the phrase "the gostak distims the doshes", an example of how it is possible to derive meaning from the syntax of a sentence even if the referents of the terms are entirely unknown. This can be seen in the following dialogue:In Amazing Stories, Dr...

distims the doshes."

Although neither a trained philosopher nor an academic, Ogden had a material effect on British academic philosophy. The Meaning of Meaning enunciated a theory of emotivism

Emotivism

Emotivism is a meta-ethical view that claims that ethical sentences do not express propositions but emotional attitudes. Influenced by the growth of analytic philosophy and logical positivism in the 20th century, the theory was stated vividly by A. J. Ayer in his 1936 book Language, Truth and...

. Ogden went on to edit as Bentham's Theory of Fictions (1932) a work of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

, and had already translated in 1911 as The Philosophy of ‘As If’ a work of Hans Vaihinger

Hans Vaihinger

Hans Vaihinger was a German philosopher, best known as a Kant scholar and for his Philosophie des Als Ob , published in 1911, but written more than thirty years earlier....

, both of which are regarded as precursors of the modern theory of fictionalism

Fictionalism

Fictionalism is a methodological theory in philosophy that suggests that statements of a certain sort should not be taken to be literally true, but merely as a useful fiction...

.

Basic English

The advocacy of Basic English became his primary activity from 1925 until his death. Basic English is an auxiliary international language of 850 words comprising a system that covers everything necessary for day-to-day purposes. To promote Basic English, Ogden in 1927 founded the Orthological Institute, from orthology, the abstract term he proposed for its work (see orthoepeia). Its headquarters were on King's ParadeKing's Parade

King's Parade is a historical street in central Cambridge, England. The street continues north as Trinity Street and then St John's Street, and south as Trumpington Street. It is a major tourist area in Cambridge, commanding a central position in the University of Cambridge area of the city...

in Cambridge. From 1928 to 1930 Ogden set out his developing ideas on Basic English and Jeremy Bentham in Psyche.

In 1929 the Institute published a recording by James Joyce

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce was an Irish novelist and poet, considered to be one of the most influential writers in the modernist avant-garde of the early 20th century...

of a passage from a draft of Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake is a novel by Irish author James Joyce, significant for its experimental style and resulting reputation as one of the most difficult works of fiction in the English language. Written in Paris over a period of seventeen years, and published in 1939, two years before the author's...

. In summer of that year Tales Told of Shem and Shaun had been published, an extract from the work as it then stood, and Ogden had been asked to supply an introduction. When Joyce was in London in August, Ogden approached him to do a reading for a recording. In 1932 Ogden published a translation of the Finnegans Wake passage into Basic English.

By 1943 the Institute had moved to Gordon Square

Gordon Square

Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden, London, England . It was developed by Thomas Cubitt in the 1820s, as one of a pair with Tavistock Square, which is a block away and has the same dimensions...

in London.

Ogden was also a consultant with the International Auxiliary Language Association

International Auxiliary Language Association

The International Auxiliary Language Association was founded in 1924 to "promote widespread study, discussion and publicity of all questions involved in the establishment of an auxiliary language, together with research and experiment that may hasten such establishment in an intelligent manner and...

, which presented Interlingua

Interlingua

Interlingua is an international auxiliary language , developed between 1937 and 1951 by the International Auxiliary Language Association...

in 1951.

Bibliophile

Ogden collected a large number of books. His incunabula, manuscripts, papers of the Brougham family, and Jeremy BenthamJeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

collection were purchased by University College London

University College London

University College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and the oldest and largest constituent college of the federal University of London...

. The balance of his enormous personal library was purchased after his death by the University of California - Los Angeles. He died on 21 March 1957 in London.

Further reading

- Damon Franke (2008), Modernist Heresies: British Literary History, 1883–1924, particularly on Ogden and the Heretics Society.