Battle of Khartoum

Encyclopedia

The Battle of Khartoum or Siege of Khartoum lasted from March 13, 1884 to January 26, 1885. It was fought in and around Khartoum

between Egypt

ian forces led by British

General

Charles George Gordon

and a Mahdist Sudanese army led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi

Muhammad Ahmad

. Khartoum was besieged by the Mahdists and defended by a garrison of 7,000 Egyptian and loyal Sudanese troops. After a ten-month siege, the Mahdists finally broke into the city and the entire garrison was killed.

British protectorate

. However, the administration of Sudan was considered a domestic matter, and left to the Khedive

's government. As a result, the suppression of the Mahdist revolt was left to the Egyptian army, who suffered a bloody defeat at the hands of the Mahdist rebels at El Obeid, in November 1883. The Mahdi's forces captured huge amounts of equipment and overran large parts of Sudan, including Darfur

and Kordofan.

These events brought Sudan to the attention of the British government, and of the British public. The Prime Minister

William Gladstone

and his War Secretary

Lord Hartington

didn't wish to become involved in Sudan. Accordingly, the British representative in Egypt, Sir Evelyn Baring

, persuaded the Egyptian government that all their garrisons in Sudan should be evacuated.

General Charles Gordon was then a popular figure in Great Britain and, having already held the Governor-Generalship of Sudan in 1876-'79, he was appointed to accomplish this task.

Gordon's ideas on Sudan were radically different from Gladstone's: he believed that the Mahdi's rebellion had to be defeated, or he might gain control of the whole of Sudan, and from there sweep over Egypt. His fears were based on the Mahdi's claim to dominion over the entire Islamic world and on the fragility of the Egyptian army, which had suffered several defeats at the hands of the Sudanese. Gordon favoured an aggressive policy in Sudan, in agreement with other imperialists

such as Sir Samuel Baker

and Sir Garnet Wolseley

, and his opinions were published in The Times

in January 1884.

Despite this, Gordon pledged himself to accomplish the evacuation of Sudan; he was given a credit of £

100,000 and was promised by the British and Egyptian authorities "all support and cooperation in their power.". On January 14, 1884 Gordon left the Charing Cross railway station in London for Dover, the ferry to Calais and on to the Sudan.

When in Cairo

, Gordon met Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur, a former slave trader who had once controlled a semi-independent province in southern Sudan. The two men had a troubled history, as Gordon had been instrumental in destroying Zubayr's influence. Passing over their previous enmity, Gordon became convinced that Zubayr was the only man with sufficient energy and charisma to counter the Mahdi.

On his way to Khartoum with his assistant, Colonel

Stewart

, Gordon stopped in Berber

to address an assembly of tribal chiefs. Here he committed a cardinal mistake by revealing that the Egyptian government wished to withdraw from Sudan. The tribesmen became worried by this news, and their loyalty wavered.

Gordon made a triumphal entry in Khartoum on February 18, 1884, but instead of organizing the evacuation of the garrisons, set about administering the city.

Gordon made a triumphal entry in Khartoum on February 18, 1884, but instead of organizing the evacuation of the garrisons, set about administering the city.

His first decisions were to reduce the injustices caused by the Egyptian colonial administration: arbitrary imprisonments were cancelled, torture

instruments were destroyed, and taxes were remitted. To enlist the support of the population, Gordon legalised slavery, despite the fact that he himself had abolished it a few years earlier. This decision was popular in Khartoum, where the economy still rested on the slave trade, but caused controversy in Britain.

The British public opinion was shaken again shortly after by Gordon's demand that Zubayr Pasha be sent to help him. Zubayr, as a former slave trader, was very unpopular in Britain; the Anti-Slavery Society

contested this choice, and Zubayr's appointment was denied by the government. Despite this setback, Gordon was still determined to "smash up the Mahdi". He requested that a regiment of Turkish soldiers be sent to Khartoum as Egypt was still nominally a province of the Ottoman Empire

. When this was refused, Gordon asked for a unit of Indian Muslim

troops and later for 200 British soldiers to strengthen the defenses of Khartoum. All these proposals were rejected by the Gladstone cabinet, which was still intent on evacuation and refused absolutely to be pressured into military intervention in Sudan.

This drove Gordon to resent the government's policy, and his telegrams to Cairo became more acrimonious. On April 8, he wrote: "I leave you with the indelible disgrace of abandoning the garrisons" and added that such a course would be "the climax of meanness".

When these criticisms were made public in Britain, the conservative

opposition seized on them and moved a vote of censure

in the House of Commons

, that the government won by only 28 votes.

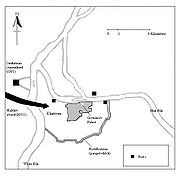

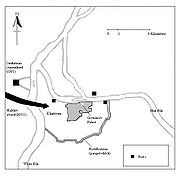

Knowing that the Mahdists were closing in, Gordon ordered the strengthening of the fortifications around Khartoum. The city was protected to the north by the Blue Nile

and to the west by the White Nile

. To defend the river banks, he created a flotilla of gunboat

s from nine small paddle-wheel steamers, until then used for communication purposes, which were fitted with guns and protected by metal plates. In the southern part of the town, which faced the open desert, he prepared an elaborate system of trenches, makeshift Fougasse-type

land mine

s, and wire entanglements. Also, the surrounding country was controlled by the Shagia

tribe, which was hostile to the Mahdi.

By early April 1884, the tribes north of Khartoum rose in support of the Mahdi, and cut the Egyptian traffic on the Nile and the telegraph

to Cairo

. Communications were not entirely cut, as runners could still get through, but the siege had begun and Khartoum could only rely on its own food stores, which could last only five or six months.

On March 16, an abortive sortie from Khartoum was launched, which led to the death of 200 Egyptian troops as the combined Arab and African warriors besieging Khartoum grew to over 30,000 men. Through the months of April, May, June and July, Gordon and the garrison dealt with being cut off as food stores dwindled and starvation began to set in for both the garrison and the civilian population. Communication was kept though couriers while Gordon also kept in contact with the Mahdi who rejected his offers of peace and to lift the siege.

On September 16, an expedition sent from Khartoum to Sennar was defeated by the Mahdis which resulted in the death of over 800 garrison troops at Al Aylafuh, while by the end of the month, the Mahdi moved the bulk of his army to Khartoum more than doubling the number already besieging it.

As of September 10, 1884, the civilian population of Khartoum was about 34,000.

intervened on his behalf. The government ordered him to return, but Gordon refused, saying he was honour-bound to defend the city. By July 1884, Gladstone reluctantly agreed to send an expedition to Khartoum. However, the expedition, led by Sir Garnet Wolseley, took several months to organize and only entered Sudan in January 1885. By then, Gordon's situation had become desperate, with the food supplies running low, many inhabitants dying of hunger and the defenders' morale at its lowest.

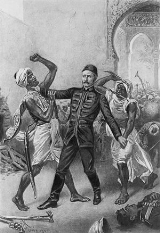

The relief expedition was attacked at Abu Klea

on January 17, and two days later at Abu Kru. Though their square

was broken at Abu Klea, the British managed to repel the Mahdists. The Mahdi, hearing of the British advance, decided to press the attack on Khartoum. On the night of January 25–26, an estimated 50,000 Mahdists attacked the city wall just before midnight. The Mahdists took advantage of the low level of the Nile, which could be crossed on foot, and rushed around the wall on the shores of the river and into the town. The details of the final assault are vague, but it is said that by 3:30 am, the Mahdists managed to concurrently outflank the city wall at the low end of the Nile while another force, led by Al Nujumi, broke down the Massalamieh Gate despite taking some casualties from mines and barbed wire obstacles laid out by Gordon's men. The entire garrison, physically weakened by starvation, offered only patchy resistance and were slaughtered to the last man within a few hours, as were 4,000 of the town's inhabitants, while many others were carried into slavery. Accounts differ as to how Gordon was killed. According to one version, when Mahdist warriors broke into the governor's palace, Gordon came out in full uniform, and, after disdaining to fight, he was speared to death—in defiance of the orders of the Mahdi, who had wanted him captured alive. In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while making for the Austrian consulate and shot dead in the street. What appears certain is that his head was cut off, stuck on a pike, and brought to the Mahdi as a trophy.

Advance elements of the relief expedition arrived within sight of Khartoum two days later. After the fall of the city, the surviving British and Egyptian troops withdrew from the Sudan, with the exception of the city of Suakin

on the Red Sea coast and the Nile border town of Wadi Halfa at the Egyptian border, leaving Muhammad Ahmad in control of the entire country.

In reality, Gladstone had always viewed the Egyptian-Sudanese imbroglio with distaste and had felt some sympathy for the Sudanese striving to throw off the Egyptian colonial rule. He once declared in the House of Commons

: "Yes, those people are struggling to be free, and they are rightly struggling to be free." Also, Gordon's arrogant and insubordinate manner did nothing to endear him to Gladstone's government.

After his victory, Muhammad Ahmad became the ruler of most parts of what is now modern-day Sudan, and established a religious state, the Mahdiyah, which was governed by a harsh enforcement of Sharia

law. He died shortly afterwards, in June 1885, though the state he founded survived him.

In Britain, Gordon came to be seen as a martyr and a hero. In 1896, an expedition led by Horatio Kitchener was sent to avenge his death and reconquer Sudan. On 2 September 1898 Kitchener's troops defeated the bulk of the Mahdist army at the Battle of Omdurman

. Two days later a memorial service for Gordon was held in front of the ruins of the palace where he had died.

Surviving family members of the movement's leaders were held by the British in a prison in Egypt

.

The women and children were held there for ten years. The men were held for twelve years. After their return to Sudan they were held under house arrest for the rest of their lives.

Khartoum

Khartoum is the capital and largest city of Sudan and of Khartoum State. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile flowing west from Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as "al-Mogran"...

between Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

ian forces led by British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

General

General

A general officer is an officer of high military rank, usually in the army, and in some nations, the air force. The term is widely used by many nations of the world, and when a country uses a different term, there is an equivalent title given....

Charles George Gordon

Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon, CB , known as "Chinese" Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British army officer and administrator....

and a Mahdist Sudanese army led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi

Mahdi

In Islamic eschatology, the Mahdi is the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will stay on Earth for seven, nine or nineteen years- before the Day of Judgment and, alongside Jesus, will rid the world of wrongdoing, injustice and tyranny.In Shia Islam, the belief in the Mahdi is a "central religious...

Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah was a religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, on June 29, 1881, proclaimed himself as the Mahdi or messianic redeemer of the Islamic faith...

. Khartoum was besieged by the Mahdists and defended by a garrison of 7,000 Egyptian and loyal Sudanese troops. After a ten-month siege, the Mahdists finally broke into the city and the entire garrison was killed.

Appointment of General Gordon

Since the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War, the British military presence ensured that Egypt remained a de factoDe facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

British protectorate

Protectorate

In history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

. However, the administration of Sudan was considered a domestic matter, and left to the Khedive

Khedive

The term Khedive is a title largely equivalent to the English word viceroy. It was first used, without official recognition, by Muhammad Ali Pasha , the Wāli of Egypt and Sudan, and vassal of the Ottoman Empire...

's government. As a result, the suppression of the Mahdist revolt was left to the Egyptian army, who suffered a bloody defeat at the hands of the Mahdist rebels at El Obeid, in November 1883. The Mahdi's forces captured huge amounts of equipment and overran large parts of Sudan, including Darfur

Darfur

Darfur is a region in western Sudan. An independent sultanate for several hundred years, it was incorporated into Sudan by Anglo-Egyptian forces in 1916. The region is divided into three federal states: West Darfur, South Darfur, and North Darfur...

and Kordofan.

These events brought Sudan to the attention of the British government, and of the British public. The Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

and his War Secretary

Secretary of State for War

The position of Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a British cabinet-level position, first held by Henry Dundas . In 1801 the post became that of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. The position was re-instated in 1854...

Lord Hartington

Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire

Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire KG, GCVO, PC, PC , styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman...

didn't wish to become involved in Sudan. Accordingly, the British representative in Egypt, Sir Evelyn Baring

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, GCB, OM, GCMG, KCSI, CIE, PC, FRS , was a British statesman, diplomat and colonial administrator....

, persuaded the Egyptian government that all their garrisons in Sudan should be evacuated.

General Charles Gordon was then a popular figure in Great Britain and, having already held the Governor-Generalship of Sudan in 1876-'79, he was appointed to accomplish this task.

Gordon's ideas on Sudan were radically different from Gladstone's: he believed that the Mahdi's rebellion had to be defeated, or he might gain control of the whole of Sudan, and from there sweep over Egypt. His fears were based on the Mahdi's claim to dominion over the entire Islamic world and on the fragility of the Egyptian army, which had suffered several defeats at the hands of the Sudanese. Gordon favoured an aggressive policy in Sudan, in agreement with other imperialists

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

such as Sir Samuel Baker

Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker, KCB, FRS, FRGS was a British explorer, officer, naturalist, big game hunter, engineer, writer and abolitionist. He also held the titles of Pasha and Major-General in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. He served as the Governor-General of the Equatorial Nile Basin between Apr....

and Sir Garnet Wolseley

Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, KP, GCB, OM, GCMG, VD, PC was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He served in Burma, the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, China, Canada, and widely throughout Africa—including his Ashanti campaign and the Nile Expedition...

, and his opinions were published in The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

in January 1884.

Despite this, Gordon pledged himself to accomplish the evacuation of Sudan; he was given a credit of £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

100,000 and was promised by the British and Egyptian authorities "all support and cooperation in their power.". On January 14, 1884 Gordon left the Charing Cross railway station in London for Dover, the ferry to Calais and on to the Sudan.

When in Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, Gordon met Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur, a former slave trader who had once controlled a semi-independent province in southern Sudan. The two men had a troubled history, as Gordon had been instrumental in destroying Zubayr's influence. Passing over their previous enmity, Gordon became convinced that Zubayr was the only man with sufficient energy and charisma to counter the Mahdi.

On his way to Khartoum with his assistant, Colonel

Colonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

Stewart

John Donald Hamill Stewart

Colonel John Donald Hamill Stewart was a British soldier. He accompanied General Gordon to Khartoum in 1884 as his assistant. He died in September 1884 attempting to run the blockade from the besieged city at the hands of the Manasir tribesmen and followers of Muhammad Ahmad Al-Mahdi.-...

, Gordon stopped in Berber

Berber, Sudan

Berber is a town in the Nile state of northern Sudan, 50 km north of Atbara, near the junction of the Atbara River and the Nile.The town was the starting-point of the old caravan route across the Nubian Desert to the Red Sea at Suakin....

to address an assembly of tribal chiefs. Here he committed a cardinal mistake by revealing that the Egyptian government wished to withdraw from Sudan. The tribesmen became worried by this news, and their loyalty wavered.

Siege begins

His first decisions were to reduce the injustices caused by the Egyptian colonial administration: arbitrary imprisonments were cancelled, torture

Torture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

instruments were destroyed, and taxes were remitted. To enlist the support of the population, Gordon legalised slavery, despite the fact that he himself had abolished it a few years earlier. This decision was popular in Khartoum, where the economy still rested on the slave trade, but caused controversy in Britain.

The British public opinion was shaken again shortly after by Gordon's demand that Zubayr Pasha be sent to help him. Zubayr, as a former slave trader, was very unpopular in Britain; the Anti-Slavery Society

Anti-Slavery Society

The Anti-Slavery Society or A.S.S. was the everyday name of two different British organizations.The first was founded in 1823 and was committed to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Its official name was the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the...

contested this choice, and Zubayr's appointment was denied by the government. Despite this setback, Gordon was still determined to "smash up the Mahdi". He requested that a regiment of Turkish soldiers be sent to Khartoum as Egypt was still nominally a province of the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. When this was refused, Gordon asked for a unit of Indian Muslim

Muslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

troops and later for 200 British soldiers to strengthen the defenses of Khartoum. All these proposals were rejected by the Gladstone cabinet, which was still intent on evacuation and refused absolutely to be pressured into military intervention in Sudan.

This drove Gordon to resent the government's policy, and his telegrams to Cairo became more acrimonious. On April 8, he wrote: "I leave you with the indelible disgrace of abandoning the garrisons" and added that such a course would be "the climax of meanness".

When these criticisms were made public in Britain, the conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

opposition seized on them and moved a vote of censure

Motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence is a parliamentary motion whose passing would demonstrate to the head of state that the elected parliament no longer has confidence in the appointed government.-Overview:Typically, when a parliament passes a vote of no...

in the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, that the government won by only 28 votes.

Knowing that the Mahdists were closing in, Gordon ordered the strengthening of the fortifications around Khartoum. The city was protected to the north by the Blue Nile

Blue Nile

The Blue Nile is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. With the White Nile, the river is one of the two major tributaries of the Nile...

and to the west by the White Nile

White Nile

The White Nile is a river of Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile from Egypt, the other being the Blue Nile. In the strict meaning, "White Nile" refers to the river formed at Lake No at the confluence of the Bahr al Jabal and Bahr el Ghazal rivers...

. To defend the river banks, he created a flotilla of gunboat

Gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.-History:...

s from nine small paddle-wheel steamers, until then used for communication purposes, which were fitted with guns and protected by metal plates. In the southern part of the town, which faced the open desert, he prepared an elaborate system of trenches, makeshift Fougasse-type

Fougasse (weapon)

A fougasse is an improvised mine constructed by making a hollow in the ground or rock and filling it with explosives and projectiles. Fougasse was well known to military engineers by the mid-eighteenth century but was also referred to by Vauban in the seventeenth century and was used by Zimmerman...

land mine

Land mine

A land mine is usually a weight-triggered explosive device which is intended to damage a target—either human or inanimate—by means of a blast and/or fragment impact....

s, and wire entanglements. Also, the surrounding country was controlled by the Shagia

Shagia

The Shaigiya are one of the three dominant tribes in Northern Sudan, the others being the Ja'Alin and Danagla. The leaders of these three tribes share the key positions in the Sudanese government of national unity .-People:...

tribe, which was hostile to the Mahdi.

By early April 1884, the tribes north of Khartoum rose in support of the Mahdi, and cut the Egyptian traffic on the Nile and the telegraph

Telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages via some form of signalling technology. Telegraphy requires messages to be converted to a code which is known to both sender and receiver...

to Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

. Communications were not entirely cut, as runners could still get through, but the siege had begun and Khartoum could only rely on its own food stores, which could last only five or six months.

On March 16, an abortive sortie from Khartoum was launched, which led to the death of 200 Egyptian troops as the combined Arab and African warriors besieging Khartoum grew to over 30,000 men. Through the months of April, May, June and July, Gordon and the garrison dealt with being cut off as food stores dwindled and starvation began to set in for both the garrison and the civilian population. Communication was kept though couriers while Gordon also kept in contact with the Mahdi who rejected his offers of peace and to lift the siege.

On September 16, an expedition sent from Khartoum to Sennar was defeated by the Mahdis which resulted in the death of over 800 garrison troops at Al Aylafuh, while by the end of the month, the Mahdi moved the bulk of his army to Khartoum more than doubling the number already besieging it.

As of September 10, 1884, the civilian population of Khartoum was about 34,000.

Fall of Khartoum

Gordon's plight excited great concern in the British press, and even Queen VictoriaVictoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

intervened on his behalf. The government ordered him to return, but Gordon refused, saying he was honour-bound to defend the city. By July 1884, Gladstone reluctantly agreed to send an expedition to Khartoum. However, the expedition, led by Sir Garnet Wolseley, took several months to organize and only entered Sudan in January 1885. By then, Gordon's situation had become desperate, with the food supplies running low, many inhabitants dying of hunger and the defenders' morale at its lowest.

The relief expedition was attacked at Abu Klea

Battle of Abu Klea

The Battle of Abu Klea took place between the dates of 16 and 18 January 1885, at Abu Klea, Sudan, between the British Desert Column and Mahdist forces encamped near Abu Klea...

on January 17, and two days later at Abu Kru. Though their square

Infantry square

An infantry square is a combat formation an infantry unit forms in close order when threatened with cavalry attack.-Very early history:The formation was described by Plutarch and used by the Romans, and was developed from an earlier circular formation...

was broken at Abu Klea, the British managed to repel the Mahdists. The Mahdi, hearing of the British advance, decided to press the attack on Khartoum. On the night of January 25–26, an estimated 50,000 Mahdists attacked the city wall just before midnight. The Mahdists took advantage of the low level of the Nile, which could be crossed on foot, and rushed around the wall on the shores of the river and into the town. The details of the final assault are vague, but it is said that by 3:30 am, the Mahdists managed to concurrently outflank the city wall at the low end of the Nile while another force, led by Al Nujumi, broke down the Massalamieh Gate despite taking some casualties from mines and barbed wire obstacles laid out by Gordon's men. The entire garrison, physically weakened by starvation, offered only patchy resistance and were slaughtered to the last man within a few hours, as were 4,000 of the town's inhabitants, while many others were carried into slavery. Accounts differ as to how Gordon was killed. According to one version, when Mahdist warriors broke into the governor's palace, Gordon came out in full uniform, and, after disdaining to fight, he was speared to death—in defiance of the orders of the Mahdi, who had wanted him captured alive. In another version, Gordon was recognised by Mahdists while making for the Austrian consulate and shot dead in the street. What appears certain is that his head was cut off, stuck on a pike, and brought to the Mahdi as a trophy.

Advance elements of the relief expedition arrived within sight of Khartoum two days later. After the fall of the city, the surviving British and Egyptian troops withdrew from the Sudan, with the exception of the city of Suakin

Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin is a port in north-eastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. In 1983 it had a population of 18,030 and the 2009 estimate is 43, 337.It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about 30 miles north. The old city built of coral is in ruins...

on the Red Sea coast and the Nile border town of Wadi Halfa at the Egyptian border, leaving Muhammad Ahmad in control of the entire country.

Aftermath

The British press put the blame of Gordon's death on Gladstone, who was charged with excessive slowness in sending relief to Khartoum. He was rebuked by Queen Victoria in a telegram which became known to the public, and an acronym applied to him, G.O.M. for "Grand Old Man" which was changed to M.O.G. the "Murderer Of Gordon". His government fell in June 1885, though he was back in office the next year. However this public outcry soon paled, firstly when press coverage and sensationalism of the events began to diminish and secondly when the government released details of the £11.5 million military budget cost for pursuing war in the Sudan.In reality, Gladstone had always viewed the Egyptian-Sudanese imbroglio with distaste and had felt some sympathy for the Sudanese striving to throw off the Egyptian colonial rule. He once declared in the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

: "Yes, those people are struggling to be free, and they are rightly struggling to be free." Also, Gordon's arrogant and insubordinate manner did nothing to endear him to Gladstone's government.

After his victory, Muhammad Ahmad became the ruler of most parts of what is now modern-day Sudan, and established a religious state, the Mahdiyah, which was governed by a harsh enforcement of Sharia

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

law. He died shortly afterwards, in June 1885, though the state he founded survived him.

In Britain, Gordon came to be seen as a martyr and a hero. In 1896, an expedition led by Horatio Kitchener was sent to avenge his death and reconquer Sudan. On 2 September 1898 Kitchener's troops defeated the bulk of the Mahdist army at the Battle of Omdurman

Battle of Omdurman

At the Battle of Omdurman , an army commanded by the British Gen. Sir Herbert Kitchener defeated the army of Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the self-proclaimed Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad...

. Two days later a memorial service for Gordon was held in front of the ruins of the palace where he had died.

Surviving family members of the movement's leaders were held by the British in a prison in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

.

The women and children were held there for ten years. The men were held for twelve years. After their return to Sudan they were held under house arrest for the rest of their lives.

Cultural depictions

- These events are depicted in the 1966 film KhartoumKhartoum (film)Khartoum is a 1966 film written by Robert Ardrey and directed by Basil Dearden. It stars Charlton Heston as General Gordon and Laurence Olivier as the Mahdi and is based on Gordon's defence of the Sudanese city of Khartoum from the forces of the Mahdist army during the Siege of Khartoum.Khartoum...

, with Charlton HestonCharlton HestonCharlton Heston was an American actor of film, theatre and television. Heston is known for heroic roles in films such as The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor, El Cid, and Planet of the Apes...

as General Gordon and Laurence OlivierLaurence OlivierLaurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM was an English actor, director, and producer. He was one of the most famous and revered actors of the 20th century. He married three times, to fellow actors Jill Esmond, Vivien Leigh, and Joan Plowright...

as Muhammad Ahmad. - The Siege of Khartoum is the setting for Wilbur SmithWilbur SmithWilbur Addison Smith is a best-selling novelist. His writings include 16th and 17th century tales about the founding of the southern territories of Africa and the subsequent adventures and international intrigues relevant to these settlements. His books often fall into one of three series...

's novel Triumph of the Sun, pub. 2005 - G. A. HentyG. A. HentyGeorge Alfred Henty , was a prolific English novelist and a special correspondent. He is best known for his historical adventure stories that were popular in the late 19th century. His works include Out on the Pampas , The Young Buglers , With Clive in India and Wulf the Saxon .-Biography:G.A...

wrote a young adults' novel about the siege called The Dash for Khartoum, originally published in 1892, since reissued and also available to read free online at Project Gutenberg. - Henryk SienkiewiczHenryk SienkiewiczHenryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz was a Polish journalist and Nobel Prize-winning novelist. A Polish szlachcic of the Oszyk coat of arms, he was one of the most popular Polish writers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1905 for his...

, Polish writer and Nobel PrizeNobel PrizeThe Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

winner, set his novel In Desert and WildernessIn Desert and WildernessIn Desert and Wilderness is a popular novel for young people by Polish author and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, written in 1912. It is in fact the author's only novel written for children. It tells the story of two young friends, Staś Tarkowski and Nel Rawlinson, kidnapped by...

in Sudan during Mahdi's rebellion, which plays a vital role in the plot.